Abstract

Background

Hispanics are the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States, and little is known about how Hispanic ethnic population density impacts cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality.

Methods and Results

We examined county‐level deaths for Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites from 2003 to 2012 using data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ Multiple Cause of Death mortality files. Counties with more than 20 Hispanic deaths (n=715) were included in the analyses. CVD deaths were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10), I00 to I78, and population estimates were calculated using linear interpolation from 2000 and 2010 census data. Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the association of Hispanic ethnic density with Hispanic and non‐Hispanic white age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates. County‐level age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates were adjusted for county‐level demographic, socioeconomic, and healthcare factors. There were a total of 4 769 040 deaths among Hispanics (n=382 416) and non‐Hispanic whites (n=4 386 624). Overall, cardiovascular age‐adjusted mortality rates were higher among non‐Hispanic whites compared with Hispanics (244.8 versus 189.0 per 100 000). Hispanic density ranged from 1% to 96% in each county. Counties in the highest compared with lowest category of Hispanic density had 60% higher Hispanic mortality (215.3 versus 134.2 per 100 000 population). In linear regression models, after adjusting for county‐level demographic, socioeconomic, and healthcare factors, increasing Hispanic ethnic density remained strongly associated with mortality for Hispanics but not for non‐Hispanic whites.

Conclusions

CVD mortality is higher in counties with higher Hispanic ethnic density. County‐level characteristics do not fully explain the higher CVD mortality among Hispanics in ethnically concentrated counties.

Keywords: enclaves, ethnicity, health disparities

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Race and Ethnicity, Mortality/Survival

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Hispanics experience greater cardiovascular mortality in counties with high Hispanic ethnic density.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Counties with high Hispanic density likely have worse access to care and other adverse environmental factors that lead to greater mortality.

Public health and clinical efforts to improve outcomes for Hispanic patients need to target the counties where Hispanics are concentrated.

Introduction

Hispanics are the largest minority group in the United States and experience a disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors.1, 2 Despite this, when studied in aggregate, Hispanics experience lower mortality rates when compared with non‐Hispanic whites (NHWs). This lower‐than‐expected mortality, despite greater adverse CVD risk profiles and lower levels of income and education than NHWs, has been coined the “Hispanic paradox.”3, 4, 5, 6 Some have speculated that residence in enclaves may be protective for Hispanics by providing a place where more salubrious cultural habits are maintained (ie, improved nutrition and lower smoking rates).7 Ethnic enclaves may also provide added social cohesion and support, which may partially account for the mortality advantage experienced by Hispanics.

As the Hispanic population in the United States continues to grow, there is also evidence of increasing residential segregation.8, 9 Hispanics are more likely to be exposed to neighborhood disadvantage, living in areas with higher rates of poverty and lower average incomes as compared with predominantly NHW neighborhoods.10 Much work on segregation and cardiovascular health has focused on blacks and has shown that residential segregation has deleterious effects on health outcomes, including higher incidence of cardiovascular disease,11 hypertension,12 and likelihood to receive care for acute myocardial infarctions in hospitals with higher mortality rates.13 Yet the data for the health effects of residential segregation for Hispanics are limited and mixed.11, 14, 15 To our knowledge, no study has specifically assessed the impact of Hispanic ethnic density on CVD mortality using national, contemporary data including a diverse sample of US Hispanics.

Thus, the objective of this study was to explore the association between Hispanic ethnic concentration (Hispanic density) and cardiovascular mortality among Hispanics and NHWs. We tested the hypothesis that residence in ethnic enclaves would be protective for Hispanic cardiovascular mortality, even after adjusting for county‐level demographic, socioeconomic, and healthcare‐related characteristics.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure because our data set is restricted; however, these data are publicly available through the US Census Bureau should other investigators choose to obtain them.

Outcome Measure

County‐level deaths for Hispanics and NHWs were examined using the National Center for Health Statistics’ Multiple Cause of Death mortality files from 2003 to 2012. To ensure that there would be sufficient counties as well as sufficient deaths in each county in the analyses, we included counties with more than 20 Hispanic CVD deaths during the study period (n=715). We then identified CVD mortality using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) codes for cardiovascular deaths (I00–I78) for Hispanic and NHW adults over age 25. Population estimates were obtained from the 2000 and 2010 census data, and the midyear estimate of the study period was calculated using linear interpolation and extrapolation out to 2012. We calculated county‐level directly standardized age‐ and sex‐adjusted CVD mortality rates (AMRs) per 100 000 population for Hispanics and NHWs by 5‐year age categories, as done in previous studies.16, 17

Predictor Variable and County‐Level Covariates

The proportion of Hispanic adults by county was calculated from census records on the basis of linear interpolations methods from 2000 and 2010. County‐level covariates were identified from the 2011 and 2012 County Health Rankings database, the census, and American Community Survey records (Table S1). The County Health Rankings and Roadmaps program (http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/about-project) collects data from different data sources and geolocates these data in order to provide a reliable and sustainable source of health information in US communities. We categorized the county‐level covariates into 3 groups: demographic characteristics (total population size, Hispanic population size, NHW population size, Hispanic deaths, NHW deaths, proportion 18 years of age and younger, proportion 65 years of age and older, and proportion female), socioeconomic characteristics (median household income, proportion below the poverty line, education, proportion employed, proportion of blacks, limited English proficiency proportion, and rural), and healthcare factors (proportion uninsured and primary care physician ratio).

Statistical Analysis

Because county Hispanic density is skewed, we categorized counties into 5 groups of Hispanic proportions using cut points based on a logarithmic scale for visual presentation: 1.38% to 2.71% (n=21), 2.72% to 7.38% (n=186), 7.39% to 20.08% (n=260), 20.09% to 54.60% (n=198) and, 54.61% to 96.10% (n=50). Directly standardized AMRs were further calculated for Hispanics and NHWs in each category. Kendall correlation was performed to test the increasing trend for Hispanic and NHW AMRs by categories of increasing Hispanic density. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and general linear models were performed to compare the county‐level characteristics among the categories. Before model selection, a correlation coefficient analysis was used to exclude collinear covariates. After testing assumptions for linear regression, including linearity, normality of the residuals, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity, multivariable linear regression models were used to examine the association of Hispanic density as a continuous variable with Hispanic and NHW AMRs with adjustment of county‐level covariates. Because Hispanic ethnic density was not normally distributed, we performed a logarithmic transformation of this variable for all models. The base model included the county‐level Hispanic density, population size, and proportion female. We excluded Hispanic and NHW population size and death counts from our final models due to the high collinearity with total population size.

We performed a sensitivity analysis using the Hispanic isolation index, a commonly used measure of metropolitan‐level segregation.18, 19 The Hispanic isolation index measures the extent to which Hispanics in a county or metropolitan area are exposed only to other Hispanics (ie, isolated from other race/ethnic groups). It is a measure of exposure, one of the 5 dimensions of metropolitan‐level segregation, and is computed as the minority‐weighted average of the minority proportion in each area, with the NHW population as the referent group.19 It ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating less exposure of Hispanic individuals to NHWs.

All analyses were performed in R Studio (version 0.99.896) and SAS (version 9.4), and statistical tests were based on 2‐sided tests with a significance level of 0.05. The map (Figure 1) was created using Tableau Desktop Public Edition 10.1.5 based on linear of interpolation of 2000 and 2010 US census data.

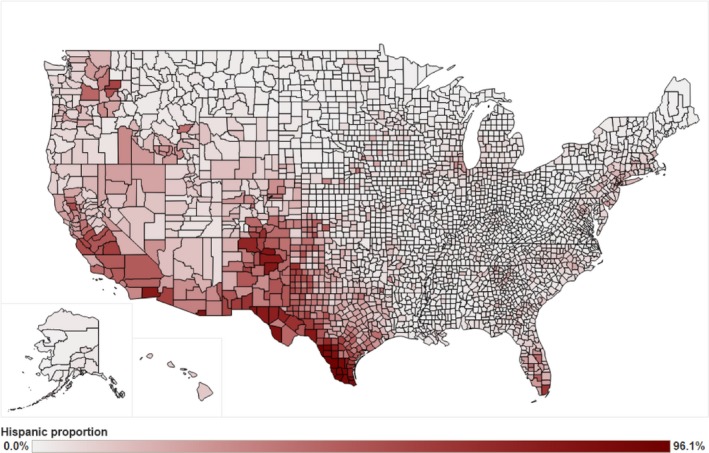

Figure 1.

Hispanic proportion of US counties from the 2000–2010 US census data.

The Institutional Review Board of Stanford University approved this study and provided a waiver for use of these publicly available mortality and US census data.

Results

A total of 4 769 040 deaths occurred during our study period among Hispanics (n=382 416) and NHWs (n=4 386 624) within the 715 counties studies. Overall, cardiovascular AMRs were higher among NHWs compared with Hispanics (244.8 versus 189.0 per 100 000). The Hispanic proportion of each US county is shown in Figure 1. Counties with higher Hispanic density were predominantly located in the southwestern United States, southern Florida, and a few regions in the Northeast.

Table 1 shows county‐level demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, and healthcare factors by Hispanic density categories among the 715 counties. Hispanic density ranged from 1% to 96%. Counties with a higher Hispanic density were more likely to have greater socioeconomic disadvantage with a lower median household income, higher proportion below the poverty line, lower high school graduation rates, and a greater proportion of residents of limited English proficiency. Counties with high Hispanic density were also more likely to be rural. The proportion of uninsured county residents increased with increasing Hispanic ethnic density. Counties with the lowest Hispanic density had 78% more primary care physicians per 100 000 population compared with counties with the highest Hispanic density.

Table 1.

County‐Level Demographic Characteristics, Social Economic Status, and Healthcare Factors by Hispanic Density Categories

| Hispanic Proportion | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.38%–2.71% (n=21) | 2.72%–7.38% (n=186) | 7.39%–20.08% (n=260) | 20.09%–54.60% (n=198) | 54.61%–96.10% (n=50) | ||

| Demographic characteristics, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Hispanic density, % | 2.1 (0.4) | 5 (1.3) | 12.7 (3.7) | 3.2 (10.3) | 71.8 (13.6) | |

| Log‐transformed Hispanic density | 0.7 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 3.5 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.2) | |

| Total population size, 100k | 42.6 (30.9) | 29.6 (27.1) | 29 (34.1) | 38.9 (98.9) | 16.6 (42.8) | 0.1033 |

| Hispanic population size, 100k | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.5 (1.4) | 3.7 (5.1) | 13 (39.2) | 11.5 (27.7) | <0.0001 |

| NHW population size, 100k | 33.7 (23.6) | 21.7 (18.5) | 18.7 (20.1) | 17.2 (38) | 3.5 (9.4) | 0.0002 |

| Hispanic deaths | 49.8 (44) | 74.4 (107.4) | 223.1 (548.7) | 1067.5 (3477.3) | 1963 (5838.2) | <0.0001 |

| NHW deaths | 12 181.9 (10 043.4) | 6795.3 (6406.2) | 6008.8 (7096.6) | 6245.2 (14 507.3) | 1360.8 (3472.2) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion 18 and younger | 23 (2) | 23.4 (2.5) | 24.1 (3.4) | 26 (3.7) | 29 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion 65 and older | 14.5 (2.7) | 13.5 (3.7) | 14 (4.5) | 13.5 (4.3) | 13.2 (2.9) | 0.4372 |

| Proportion female | 51.4 (0.8) | 51 (1) | 50.3 (1.5) | 49.4 (2.7) | 49.9 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Social economic status | ||||||

| Median household income, 10k | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.5) | 4.7 (1.2) | 3.6 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion below poverty line | 8.5 (3.8) | 8.9 (3.8) | 9.3 (3.7) | 12.4 (3.9) | 20.4 (7.2) | <0.0001 |

| High school graduation rate | 80.5 (9.3) | 78 (10.5) | 77.1 (9.9) | 72.9 (9.9) | 68.9 (9.5) | <0.0001 |

| Some college rate | 63.5 (7.2) | 63.1 (8.6) | 58.5 (10.7) | 49.3 (10.5) | 41.7 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion unemployment | 9.8 (3.1) | 9.2 (2.6) | 8.9 (2.5) | 8.5 (3) | 10.1 (4.4) | 0.0026 |

| Proportion black | 12.9 (12.3) | 12.8 (13.5) | 9.7 (10.8) | 6.5 (6.4) | 2.6 (3.2) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion not proficient in English | 2 (1) | 3.1 (1.6) | 6.2 (3.5) | 12.4 (6.2) | 21.8 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Proportion rural | 15.8 (12.3) | 22 (17.3) | 28 (23.7) | 33.3 (26.5) | 33.3 (23.6) | <0.0001 |

| Healthcare factors | ||||||

| Proportion uninsured | 14.7 (4.9) | 16.5 (4.6) | 20.6 (6.1) | 27.2 (6.2) | 32.4 (7.5) | <0.0001 |

| Primary care physicians per 100 000 population | 93 (40.5) | 92.2 (47.4) | 78.1 (42.4) | 62.8 (36.6) | 42.7 (29.1) | <0.0001 |

NHW indicates non‐Hispanic white.

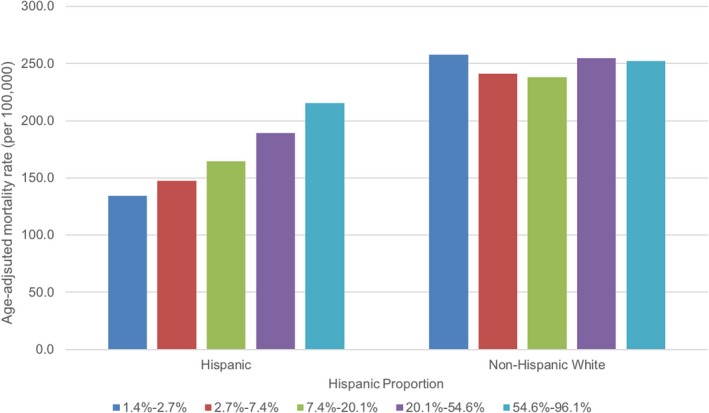

Age‐adjusted CVD mortality of Hispanics and NHWs by Hispanic density categories is shown in Figure 2. Overall, there was a statistically significant graded increase in Hispanic CVD mortality as Hispanic proportion increased (P=0.0143). However, Hispanic proportion was not significantly associated with mortality for NHWs (P=0.6242). Counties in the highest compared with lowest category of Hispanic density had 60% higher Hispanic mortality (215.3 versus 134.2 per 100 000).

Figure 2.

Age‐adjusted cardiovascular mortality rate (per 100 000) for Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites by Hispanic proportion.

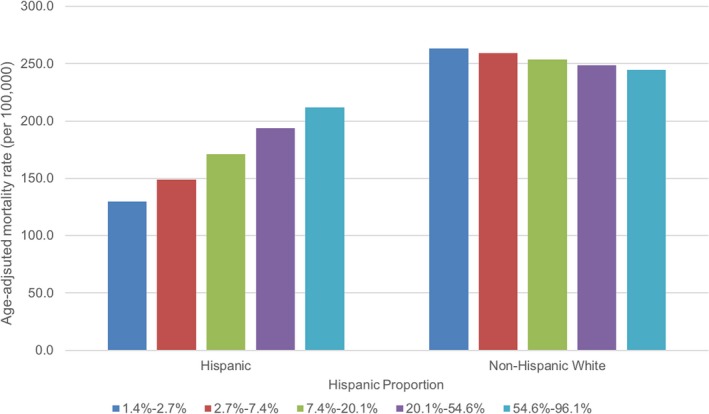

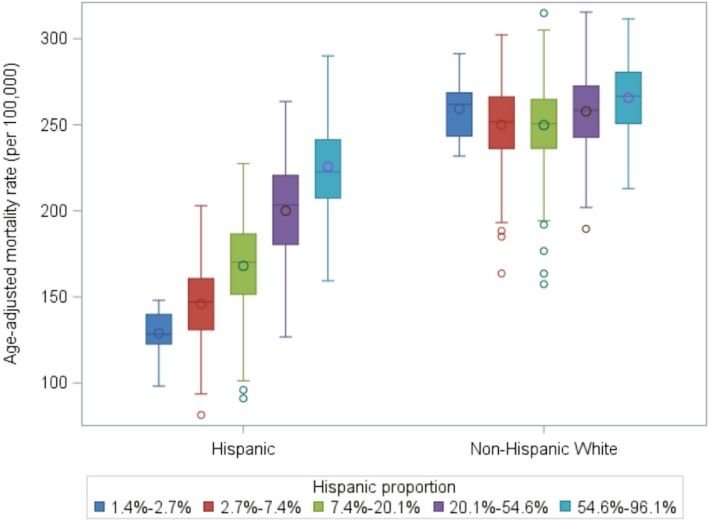

Table 2 provides the multivariable linear regression model results, adjusting for demographic (base model), socioeconomic, and healthcare factors separately, and then combined for both Hispanic AMRs and NHW AMRs. Socioeconomic and healthcare factors explained 37% and 26% of the county‐level variation in Hispanic mortality and 30% and 10% for NHW mortality, respectively. The fully adjusted model accounted for 38% and 31% of the mortality variation for Hispanics and NHWs, respectively. Hispanic density had a stronger association with mortality among Hispanics as compared with NHWs (r 2=0.22, P<0.0001) than NHWs (r 2=0.01, P=0.0461) in the base model. In fully adjusted models, the mortality gradient for Hispanics in counties with higher Hispanic density remained unchanged. For each 1‐unit increase in Hispanic density on the log scale, there was a 22.57 increase in age‐adjusted mortality rates per 100 000 for Hispanics. The fully adjusted estimates are modeled in Figure 3, using the midpoint value for each Hispanic ethnic density category and the mean value for other covariates. Adjusted models for Hispanic and NHW AMRs by Hispanic proportion including all available data points are presented in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Multivariate Linear Regression Models for Hispanic and Non‐Hispanic White Age‐Adjusted Cardiovascular Mortality per 100 000 (Per 1‐Unit Increase in Log Hispanic Ethnic Density)

| Adjustment Variables | Hispanic AMR | Non‐Hispanic White AMR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Change in AMR | P Value | R 2 | N | Change in AMR | P Value | R 2 | |

| Base model | 715 | 26.68 | <0.0001 | 0.22 | 715 | 3.64 | 0.0461 | 0.01 |

| Base model+SESa | 706 | 19.96 | <0.0001 | 0.37 | 706 | −4.02 | 0.1296 | 0.30 |

| Base model+healthcare factors | 715 | 24.63 | <0.0001 | 0.26 | 715 | −4.86 | 0.0399 | 0.10 |

| Fully adjusted modela | 706 | 22.57 | <0.0001 | 0.38 | 706 | −5.20 | 0.0605 | 0.31 |

Base model: Hispanic proportion, population size and proportion female. SES: median household income, % under poverty line, % high school graduation, % some college, % unemployed, %black, % not proficient in English and % rural. Healthcare factors: % uninsured, primary care physician rate. Fully adjusted model: base model+SES+healthcare factors. AMR indicates age‐adjusted mortality rates; SES, socioeconomic status.

Nine counties are missing high school graduation rate and are therefore not included in the SES adjusted models. These counties include Orleans, Marin, Richmond, Kings, New York, Queens, Bronx, Jeff Davis, and Yuma.

Figure 3.

Modeled estimates of age‐adjusted cardiovascular mortality rate (per 100 000) for Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites by Hispanic proportion. The model estimates include midpoint values of Hispanic density on log scale (1.9% for category 1, 4.5% for category 2, 12.2% for category 3, 33.1 for category 4, and 73.7 for category 5) and mean values were used for other covariates (population size, proportion female, median household income, % under poverty line, % high school graduation, % some college, % unemployed, % black, % not proficient in English and % rural, % uninsured and primary care physician rate).

Figure 4.

Box‐plot of fully adjusted cardiovascular mortality rate (per 100 000) for Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites by Hispanic proportion. The displayed results were adjusted for the following county characteristics: population size, proportion female, median household income, % under poverty line, % high school graduation, % some college, % unemployed, %black, % not proficient in English and % rural, % uninsured and primary care physician rate).

In a sensitivity analysis, we used the Hispanic isolation index as the predictor (Table S2) for the multivariable linear regression models. The results were qualitatively similar.

Discussion

Using a decade of national data, we found that Hispanic ethnic density is positively correlated with CVD mortality among both Hispanics and NHWs. However, this finding persisted for Hispanics after adjusting for county‐level sociodemographic and healthcare factors. The finding that Hispanic ethnic density is associated with increased CVD mortality is noteworthy and challenges existing notions about the protective effect of cultural enclaves among Hispanics.

Prior work studying the effects of neighborhood segregation and CVD among Hispanics is limited and mixed. Studies have largely focused on CVD risk factor prevalence and self‐reported health outcome measures.18, 20, 21 While residential segregation has been linked with higher incidence of CVD among blacks, there was no association in incidence of CVD among Hispanics in the Multi‐ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.11 Using the isolation index as a measure of residential segregation, Corral and colleagues found a positive association between Hispanic segregation and prevalence of obesity.22 One study in Chicago found that although residential segregation was associated with lower odds of hypertension, individuals were less likely to regularly see physicians or take antihypertensive medications.23 Neighborhoods with high Hispanic ethnic density have been linked with better diet but worse physical activity environments.7

Our findings have several possible explanations. Similar to blacks, Hispanics are likely to live in more deprived neighborhoods with higher poverty and lower availability of resources.24, 25 As documented in our study and others,11 areas of high Hispanic segregation are associated with adverse socioeconomic conditions. Low neighborhood socioeconomic status has been associated with an increased risk of out‐of‐hospital cardiac death.26 Furthermore, it is possible that residual confounding by unmeasured neighborhood or individual‐level characteristics account for the higher mortality in counties with high Hispanic ethnic density, and that the previously hypothesized protective effects of cultural enclaves are unable to fully counter these effects. Other studies have also found deleterious effects of residence in enclaves on mortality; one study found that Hispanic residential segregation was associated with increased breast cancer mortality among women in Texas.27

Our study found that areas of higher Hispanic population density had higher rates of uninsured individuals and fewer primary care physicians. Healthcare facilities that Hispanics are able to access may also provide lower quality of care, partially explaining the higher mortality rates. Prior work has documented that care for elderly Hispanics is highly concentrated among certain hospitals, known as “Hispanic‐serving hospitals.”28, 29, 30 These hospitals have lower‐quality metrics and experience higher readmissions for acute myocardial infarctions and heart failure for both Hispanics and NHWs, even after adjustment for hospital and patient characteristics. It is likely that quality and resource disadvantages in these acute care hospitals impact CVD mortality and contribute to our findings. Similarly, in a study that looked at preventable hospitalizations among minority patients across 15 states, healthcare access, lower provider availability, and socioeconomic factors accounted for higher rates of preventable hospitalizations for Hispanics.31

We did not observe an association between Hispanic ethnic density and NHW mortality in unadjusted analyses. This is likely explained by the fact that we included only counties that had at least 20 Hispanic deaths, excluding ≈2428 counties. Counties where Hispanics live and die have less favorable socioeconomic factors. After adjusting for county‐level characteristics, NHWs experienced lower CVD mortality rates in counties with a higher Hispanic proportion, although the effect size was small. A possible explanation for our findings is that areas of high Hispanic ethnic density are associated with improved outcomes for other ethnic groups living in the same area, thereby countering the effects of deleterious county‐level characteristics. One study by Chetty and colleagues documented that life expectancy was positively correlated with local area fraction of immigrants (r=0.72; P<0.001).32 That is, the higher the proportion of immigrants in a county, the higher the overall life expectancy of the entire county. Alternatively, county‐level socioeconomic factors may account for more of the variation in socioeconomic‐related CVD mortality among NHWs than among Hispanics. More granular socioeconomic measures (ie, for neighborhoods and individuals rather than counties) may be needed in future studies to further explore these associations across race/ethnic groups.

Our study has several important strengths, including a large, nationally representative sample of Hispanics and a focus on CVD mortality. Prior studies have been limited to Mexican Americans, whereas our analysis captures a more representative, heterogeneous group of Hispanics of all ages across the United States. Our analysis also adjusted for important county characteristics including demographic, socioeconomic, and healthcare factors, which may explain the relationship between Hispanic ethnic density and CVD mortality. Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, we used Hispanic proportion in US counties as a proxy for neighborhood composition. However, we also performed a sensitivity analysis using the isolation index metric that showed qualitatively similar results (Table S2). Because of this methodological limitation, we were unable to control for more detailed, important neighborhood and individual‐level characteristics such as the built environment, which may account for residual confounding. Our observed results may be due to unmeasured individual‐level data, which may show different patterns than our ecological data. Our study is cross‐sectional, which limits our ability to infer causality. Misclassification of race and ethnicity data on mortality records may have led to under‐ or overestimation of mortality rates. Finally, Hispanics are a very heterogeneous group and represent over 20 different national origins and degrees of acculturation.1 Due to limited sample sizes, we are unable to account for subgroup or acculturation differences in mortality by Hispanic density.

Our findings suggest that residence in Hispanic ethnic enclaves is unlikely to explain the Hispanic paradox in CVD mortality. Furthermore, our work has important implications for public health interventions designed to reduce disparities among Hispanics. Such interventions should target areas of high‐proportion Hispanic density and explore the adverse health consequences of residential segregation. Future studies examining the importance of ethnic density on CVD should disaggregate Hispanics by subgroups and acculturation, as well as study these findings prospectively.

Conclusion

In a large, national study of 10 years of mortality data, we found that Hispanic ethnic density is associated with increased CVD mortality for both Hispanics and NHWs. This finding persisted after adjusting for county‐level characteristics among Hispanics. More work is needed to unpack the individual and neighborhood‐level explanations for this observation.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD007012) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (F32HL132396).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Data Source and Year of the Variables

Table S2. Multivariate Linear Regression Models for Hispanic and Non‐Hispanic White CVD Mortality by the Hispanic Isolation Index

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009107 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009107.)

The abstract of this work was presented at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions, November 11 to 15, 2017, in Anaheim, CA.

References

- 1. Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, Palaniappan L, Pina IL, Ramirez SM, Rodriguez B, Sims M; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing . Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:593–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Writing Group Members , Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:S68–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medina‐Inojosa J, Jean N, Cortes‐Bergoderi M, Lopez‐Jimenez F. The Hispanic paradox in cardiovascular disease and total mortality. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2464–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e52–e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osypuk TL, Diez Roux AV, Hadley C, Kandula NR. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The Multi‐ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Correa A, Greer S, Sims M. Assessing neighborhood‐level effects on disparities in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2015;131:124–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iceland J, Weinberg D, Hughes L. The residential segregation of detailed Hispanic and Asian groups in the United States: 1980–2010. Demogr Res. 2014;31:593–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Firebaugh G, Farrell CR. Still large, but narrowing: the sizable decline in racial neighborhood Inequality in metropolitan America, 1980–2010. Demography. 2016;53:139–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kershaw KN, Osypuk TL, Do DP, De Chavez PJ, Diez Roux AV. Neighborhood‐level racial/ethnic residential segregation and incident cardiovascular disease: the Multi‐ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2015;131:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kershaw KN, Robinson WR, Gordon‐Larsen P, Hicken MT, Goff DC Jr, Carnethon MR, Kiefe CI, Sidney S, Diez Roux AV. Association of changes in neighborhood‐level racial residential segregation with changes in blood pressure among black adults: the CARDIA study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:996–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarrazin MV, Campbell M, Rosenthal GE. Racial differences in hospital use after acute myocardial infarction: does residential segregation play a role? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w368–w378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li K, Wen M, Henry KA. Ethnic density, immigrant enclaves, and Latino health risks: a propensity score matching approach. Soc Sci Med. 2017;189:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: is there a barrio advantage? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez F, Hastings KG, Boothroyd DB, Echeverria S, Lopez L, Cullen M, Harrington RA, Palaniappan LP. Disaggregation of cause‐specific cardiovascular disease mortality among Hispanic subgroups. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:240–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rodriguez F, Hastings KG, Hu J, Lopez L, Cullen M, Harrington RA, Palaniappan LP. Nativity status and cardiovascular disease mortality among hispanic adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e007207. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kershaw KN, Albrecht SS. Racial/ethnic residential segregation and cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2015;9:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Massey DS, Denton NA. Hypersegregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography. 1989;26:373–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Do DP, Frank R, Zheng C, Iceland J. Hispanic segregation and poor health: it's not just black and white. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:990–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohn T, Miller A, Fogg L, Braun LT, Coke L. Impact of individual and neighborhood factors on cardiovascular risk in white Hispanic and non‐Hispanic women and men. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40:120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corral I, Landrine H, Zhao L. Residential segregation and obesity among a national sample of Hispanic adults. J Health Psychol. 2014;19:503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Viruell‐Fuentes EA, Ponce NA, Alegria M. Neighborhood context and hypertension outcomes among Latinos in Chicago. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osypuk TL, Galea S, McArdle N, Acevedo‐Garcia D. Quantifying separate and unequal: racial‐ethnic distributions of neighborhood poverty in metropolitan America. Urban Aff Rev Thousand Oaks Calif. 2009;45:25–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foraker RE, Rose KM, Kucharska‐Newton AM, Ni H, Suchindran CM, Whitsel EA. Variation in rates of fatal coronary heart disease by neighborhood socioeconomic status: the atherosclerosis risk in communities surveillance (1992–2002). Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:580–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pruitt SL, Lee SJ, Tiro JA, Xuan L, Ruiz JM, Inrig S. Residential racial segregation and mortality among black, white, and Hispanic urban breast cancer patients in Texas, 1995 to 2009. Cancer. 2015;121:1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez F, Joynt KE, Lopez L, Saldana F, Jha AK. Readmission rates for Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011;162:254–261.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. The characteristics and performance of hospitals that care for elderly Hispanic Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Low‐quality, high‐cost hospitals, mainly in South, care for sharply higher shares of elderly black, Hispanic, and Medicaid patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:1904–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Feng C, Paasche‐Orlow MK, Kressin NR, Rosen JE, Lopez L, Kim EJ, Lin MY, Hanchate AD. Disparities in potentially preventable hospitalizations: near‐national estimates for Hispanics. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:1349–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, Lin S, Scuderi B, Turner N, Bergeron A, Cutler D. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315:1750–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Data Source and Year of the Variables

Table S2. Multivariate Linear Regression Models for Hispanic and Non‐Hispanic White CVD Mortality by the Hispanic Isolation Index