Abstract

Temperature is one of the most fundamental parameters for the characterization of a physical system. With rapid development of lab-on-a-chip and biology at single cell level, a great demand has risen for the temperature sensors with high spatial, temporal, and thermal resolution. Nevertheless, measuring temperature in liquid environment is always a technical challenge. Various factors may affect the sensing results, such as the fabrication parameters of built-in sensors, thermal property of electrical insulating layer, and stability of fluorescent thermometers in liquid environment. In this review, we focused on different kinds of micro/nano-thermometers applied in the thermal sensing for microfluidic systems and cultured cells. We discussed the advantages and limitations of these thermometers in specific applications and the challenges and possible solutions for more accurate temperature measurements in further studies.

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Introduction of thermal sensing in fluid

Microfluidic systems or lab-on-a-chip platforms are based on the networks of microscopic channels. These channels connect micro-pumps, micro-valves, micro-reservoirs, micro-electrodes, micro-sensors, and other components together and integrate the microfluidic systems with sophisticated functions of mixing, diluting, reacting, sampling, separating, and detecting.1–5 Microfluidic systems perform manipulations and measurements with decreased consumption of reagents, reduced time of analysis, increased sensitivity of detection, and improved efficiency and portability than those for macro-scale systems.6,7 These merits enable microfluidic systems to be extensively applied in systems for fundamental research, tools in chemistry and biochemistry, biomedical devices, and analytical systems.8–11 For instance, microfluidic systems are employed to conduct DNA amplification12,13 and materials synthesis,14–17 to perform drug screening,18 cell culture, and lysis,19,20 to study transport properties of ions in a confined geometry,21,22 and to imitate the electromagnetic interaction among biological macromolecules.23

In many of these microfluidic applications, such as DNA amplification, cell culture, chemical reaction, and micro-fluid driving and controlling, to monitor and control the local temperature of a fluid at the micro-nano-scales often plays a critical role. In chemical and biological reactions, temperature is a major parameter that affects chemical reactivity, kinetics, and thermodynamics. For example, the efficiency of an enzyme activation reaction could be modulated by varying buffer temperature.24,25 The temperature gradients induced by the self-heating effect of capillary electrophoresis (CE) system could cause band spreading with a consequent reduction in separation efficiency.26,27 In polymerase chain reaction (PCR), it is important to precisely sense the local temperatures in different reaction sessions for effective thermal controlling, otherwise the PCR system may duplicate DNA molecules with low quality.28,29 Therefore, in order to make full use of microfluidic systems with the most efficient outputs and accurate measurements, it is ideal to build sensors for precise temperature monitoring and controlling into these systems.

With rapid development of biological sciences at single cell level, cell temperature measurement has recently become a hot topic. Environmental temperature variation may affect cellular activities and functions.30,31 And biological activities inside a cell, such as enzyme reaction and metabolism, may induce intercellular temperature fluctuations in turn.32–34 A full picture of the temperature distribution and thermal response of a single cell under different conditions is very helpful for answering fundamental biology questions in cell thermogenesis and thermal regulation. It may provide clues for a better understanding of the underlying mechanism of many diseases. Since it is commonly accepted that one of the first signatures of any given illness (such as cancer) is the appearance of thermal singularities.35,36

Over the years, a number of thermometers with high spatial and thermal resolution, high accuracy, and fast response times have been developed.37–43 For micro/nano-thermometry applied in microfluidic systems and cell temperature measurements, the physical and chemical properties of thermoelectricity in thermoelectric materials,44 the thermal resistance of electrical conductors,45 the fluorescence and spectral characteristics of luminescent indicators,46 and the infrared radiation of heated objects47 are utilized. In this work, we reviewed a variety of thermometers at the micro-nano-scales based on their specific applications in the microfluidic systems and cultured cells. The thermometers are categorized according to their measurement principles and listed in Table I. We compared the advantages and drawbacks of these techniques in terms of spatial and thermal resolution, accuracy, sensitivity, dynamic response, and manufacturing constraints in specified applications. We also discussed open questions and challenges in certain cases and proposed feasible solutions for further studies.

TABLE I.

Different thermometers for thermal sensing of microfluidic systems and cultured cells.

| Thermometer | Mode | Measurement signal | Resolution | Temperature range (°C) | Advantages | Limitations | Applications | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal [K] | Spatial [μm] | Temporal [s] | ||||||||

| Wire thermocouple | Invasive | Voltage | 0.1 | 100 | <1 | NA | High accuracy, rapid response, low fabrication cost | Low spatial resolution, single measure point | PCR | 44 |

| Thin film thermocouple | Voltage | 0.05 | 5 | 0.3–0.4 μ | 25–105 | Scalable size, good stability, fast response time, small thermal capacity, good built-in capability | Limited spatial resolution, discrete measure points | PCR, microreactor | 79–82 | |

| Thin film thermopile | Voltage | 0.01 | 250 | 100 m | NA | High thermal sensitivity | Low spatial resolution | Microreactor | 51 | |

| Diode temperature sensor | Voltage | 0.5 | 50 | 1 m | 0–100 | High thermal sensitivity, manageable number of lead wires | Self-heating effect | Microfluidic systems | 52 | |

| Resistive temperature detector | Resistance | 0.1 | 5 | 100 m | 25–100 | Easy fabrication, good stability, high thermal sensitivity, good built-in capability | Limited spatial resolution, discrete measure points, self-heating effect | PCR, cell culture systems | 83–85 | |

| Liquid metal | Resistance | 0.1 | 20 | NA | 28–90 | Easy fabrication | Limited spatial resolution | Microfluidic systems | 70 | |

| IR thermography | Non-invasive | Radiation | 0.2–1 | 3–10 | 1 | 20–100 | Rapid response, whole-field temperature readings | Limited spatial resolution, low accuracy | PCR | 86, 87 |

| Fluorescent dye | Semi-invasive | Fluorescence intensity | 0.03–3.5 | 1 | 33 | 25–90 | Whole-field temperature readings | Low accuracy | PCR | 56 |

| Thermochromic liquid crystal | Hue | 0.4 | 10–150 | 75 m | −30–120 | Whole-field temperature readings | Limited spatial resolution, narrow temperature display range | PCR, microreactor | 78, 88 | |

| Fluorescent polymeric thermometer | Semi-invasive | Fluorescence lifetime | 0.05–0.54 | 200 | NA | 28–38 | Nano size, biocompatibility, internal cell temperature | Get affected by intracellular environment, low accuracy, produce qualitative data | Cell temperature measurement | 75 |

| Quantum dot | Fluorescence intensity ratio | NA | 200 | 100 μ | −50–130 | 89 | ||||

| Mito thermo yellow | Fluorescence intensity | 1.12–1.40 | 200 | NA | 34–60 | 90 | ||||

| Thermocouple probe | Invasive | Voltage | 0.1 | 0.5 | 32 μ | 20–45 | High accuracy, fast response time, internal cell temperature | Unfriendly to cell, limited spatial resolution | 91, 92 | |

| Thin film thermocouple | Voltage | 0.01 | 2 | NA | 25–160 | Good stability, high accuracy, fast response time | Limited spatial resolution, external cell temperature | 93 | ||

| Resonant thermal sensor | Resonant frequency | 79 μ | 30 | 2.3 | 30–60 | High thermal sensitivity | Low accuracy, external cell temperature | 94 | ||

| Bimaterial microcantilever thermometer | Deflection | 0.7 m | 20 | NA | 25–40 | 95 | ||||

B. Introduction of thermometers

Based on the nature of contact which exists between the thermometers and the liquid medium of interest, all the temperature measurement techniques involved in this review can be classified into three categories, including invasive, semi-invasive, and non-invasive thermometry.48 For invasive thermometry, thermometers are in direct contact with the medium of interest, including thermocouple (TC),49 resistive temperature detector (RTD),50 thin film thermopile,51 diode,52 liquid metal,53 resonant thermal sensor,54 and bimaterial microcantilever thermometer.55 For semi-invasive thermometry, the temperature of the medium of interest is able to be measured indirectly taking the advantages of thermal sensitive materials, including fluorescent dye,56 thermochromic liquid crystals (TLCs),57 fluorescent polymeric thermometer (FPT),58 and quantum dots (QDs).59 For non-invasive thermometry, the intrinsic thermal sensitive features of the medium of interest enable the remote temperature measurement, such as IR thermography.60

Thermocouples are a widely used type of thermometers, who produce temperature-dependent voltages. Thermocouples can be fabricated into different styles, including macroscale wire thermocouples (commercial thermocouples),61 microscale thin film thermocouples (TFTCs),62 and nanoscale thermocouple probes.63 Thermocouples provide stable performances with a short dynamic response time, high accuracy, and unique flexibility in size and composition of material.64 For RTDs, their electrical resistances change with temperature variations.65 They have a high thermal sensitivity and easy fabrication processes.66 Thin film thermopiles are cascaded sets of TFTCs with a high thermopower but low spatial resolution.67 Diodes are another kind of thermovoltage-based thermometers.68 They provide large output voltage signals. With a power supply, they heat themselves up during the temperature measurement.69 Liquid metal is a novel RTD.70 It can be made into temperature sensor in a simple, rapid, and low-cost way by injecting. Resonant thermal sensor is based on the changes in the resonant frequency of the resonator induced by temperature variations with features tens of microns in size.54 They show a high thermal sensitivity. Bimaterial microcantilever thermometer relies on the deflection of the bimaterial cantilever beam end due to the variation in temperature.71 It is used for external cell temperature measurement. All these invasive thermometers can be fabricated through standard micro-nano processing technology. Invasive thermometers with microscale size may add their thermal mass to the measurement systems. Additionally, they can measure temperature only at a few discrete points or lines. Fluorescent dyes are employed as thermometers by making use of their temperature-dependent fluorescence intensity or fluorescence lifetime.56,72 They provide high spatial and temporal resolution, but low measurement accuracy. TLCs change their color with varied temperature due to phase transition.73 They display the whole temperature field with a narrow temperature range and limited spatial resolution.74 FPTs are novel intercellular thermometers whose fluorescence lifetime increases with the elevated temperature.75 It provides high spatial resolution and fluctuant thermal resolution. QDs measure temperature based on the increments of the fluorescence intensity ratio with the raised temperatures.76 Without a core-shell structure, they are unstable in the liquid environment. Non-invasive IR thermography relies on monitoring the infrared spectrum emitted heated objects.77 This temperature measurement technique has continuous temperature readings, rapid response, and a low accuracy.78

II. TEMPERATURE MEASUREMENT IN MICROFLUIDIC SYSTEM

A. Thermometers in PCR system

The PCR is an enzymatic reaction for selective amplification of a DNA molecule. It starts from the separation of a double-stranded seed DNA sequence at the denaturation temperature of 90–95 °C. Oligonucleotide primer pairs are amplified at the annealing temperature of 50–65 °C. Catalyzing by the DNA polymerase, DNA strands are extended at the elongation temperature of 70–75 °C.49 Each thermal cycle doubles the concentration of the DNA, and a single DNA molecule can be replicated more than a million times after 20–30 cycles. PCR is highly temperature-dependent. Therefore, it is important to use effective thermometers for accurate temperature control during the PCR cycling. The first micromachined PCR chip was described by Northrup et al. in 1993.96 It was a silicon-based stationary PCR chip using Cr/Al thermocouples to measure the chamber temperature in situ. With the development of PCR microfluidics, various other thermometers have been exploited for the thermal sensing, including resistive temperature detectors (RTDs), infrared (IR) thermography, fluorescent dyes, and thermosensitive liquid crystals (TLCs).

1. Wire thermocouple

The thermocouple is a kind of thermovoltage-based thermometer, which employs the Seebeck effect of thermoelectric materials to measure the temperature.97 Once two different thermoelectric materials A and B form a thermocouple with their one end (hot end) being ohmic contacted, an electrical voltage at the two open ends (cold end) will be measured when a temperature difference is established between the hot end and cold end. The electrical voltage can be calculated by the following equation:98

| (1) |

where and represent the Seebeck coefficients of materials A and B, respectively, and are the temperatures at the hot end and the cold end, respectively. is the thermopower of the thermocouple, which shows the ability to generate thermoelectric signal, and is the temperature difference between the hot end and cold end.

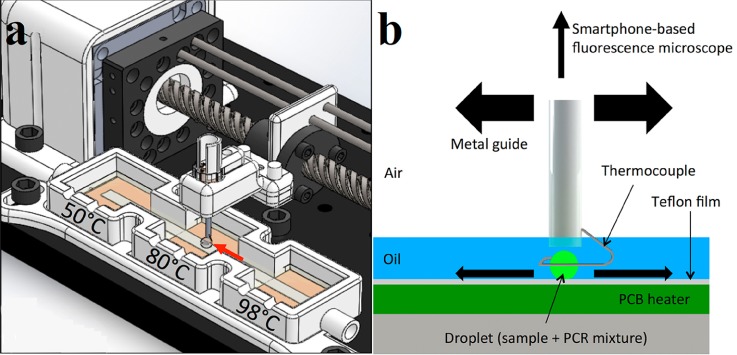

Taking the advantages of a simple structure, rapid response, high measurement accuracy, and low fabrication cost, thermocouples are widely applied in PCR systems for the chamber temperature measurement. For macroscale PCR process, standard T-type or K-type thermocouples were mounted close to the heaters or even inserted into the chambers to provide feedback for proportion-integral-derivative (PID) temperature controllers maintaining constant chamber temperature.61,99–102 Angus et al. developed a portable droplet PCR system for the detection of Escherichia coli.44 In this device, the PCR mixture was guided by a wire-guided droplet manipulation (WDM) over three different heating zones. Figure 1 schematically illustrates the structure of the PCR system and the thermal cycle process occurred in this device. The motion of the droplet directed by a ring shaped type-K thermocouple (Sparkfun Electronics) is shown in Fig. 1(b). The droplet can be steadily held by the thermocouple loop through the hydrophilic attraction and surface tension. The immersed thermocouple provided real-time droplet temperature feedback with a measuring frequency of once every second. However, the diameter of the smallest commercially available thermocouple is on the order of 100 μm, which greatly limited their application in miniaturized PCR microfluidic.

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustrations for the portable system layout and its operation. (a) The droplet moves from the denaturation chamber to the annealing chamber, and then to the extension chamber to complete a thermal cycle. (b) Graphical representation of the motion of the droplet. Reprinted with permission from Angus et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 74, 360 (2015). Copyright 2015 Elsevier B.V.

2. Thin film thermocouple

Taking the advantage of state-of-the-art micro-nano processing technology, thin film temperature sensors, including thin film thermocouple (TFTC), have been integrated with the miniaturized PCR systems.49 The TFTC was first described by Harris and Johnson for the measurement of alternating temperatures of a sound wave and small intensities of radiation in 1934.103 To obtain short response time, high spatial and thermal resolution, the TFTCs have been made increasingly delicate. The smallest planar TFTC that has been reported is a thin-film Au/Ni TFTC with junction size of 100 nm × 100 nm. However, the total width of this TFTC was larger than 8 μm.81 By introducing a sandwich structure, the smallest three-dimensional (3D) stacking TFTC with good stability and high resolution has its total width down to 138 nm.104

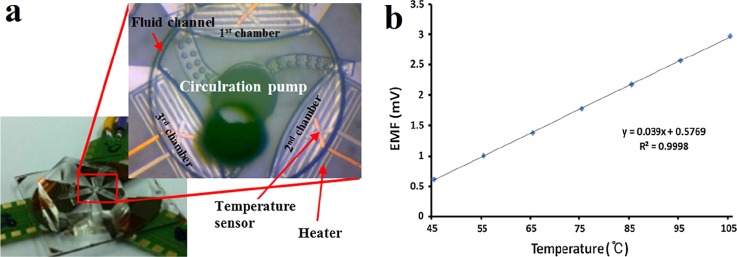

With various merits of passive sensing mechanism, scalable size, small thermal capacity, fast response time, and good built-in capability, TFTC is believed to be a powerful thermometer in the PCR systems. Mun et al. developed a space-domain PCR device using a single circulation pump.49 In this glass-based system, three Pt/Ti thin film heaters and three Cu/CuNi TFTC temperature sensors were deposited under three different reaction chambers, respectively, shown in Fig. 2(a). Calibrated with a convection oven, the TFTC temperature sensors presented a thermopower of 39 μV/K, shown in Fig. 2(b). During the DNA amplification, this thermal cycling system provided a temperature variation within ±1 K in each reaction chamber.

FIG. 2.

A space-domain PCR system which integrates with TFTCs. (a) CCD image of the space-domain PCR device. The inset is a magnified image of the core region including the circulation pump, the heaters, the TFTC temperature sensors, and the three chambers. (b) Calibration curve of the Cu/CuNi TFTC temperature sensor. Reprinted with permission from Mun et al., Microsyst. Technol. 23(10), 4405 (2017). Copyright 2017 Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

3. Resistive temperature detector

A resistive temperature detector (RTD) is a thermoresistance-based thermometer whose resistance changes with the temperature.105 It can be made from different conducting materials, such as Pt,106,107 Au,108–111 Al,112 Ni,113 Si,114 and indium-tin oxide (ITO).115 Commercial available Pt 100 sensors with large diameters are fixed near the heaters for precise temperature control in PCR systems and a temperature accuracy within ±0.1 K can be achieved.116–119 With micro-nano processing technology, RTDs have been designed into two kinds of structures: the two-wire serpentine traces and the four-lead electrodes, with thicknesses of a few hundred nanometers and widths of a few tens of microns. With good biological compatibility, gold serpentine trace RTDs can be prepared on flexible substrates to monitor the temperature in biological tissues, such as myocardial tissue109,110 and brain.111 Integrating with microheaters made from the same material, four-lead platinum RTDs can be fabricated on suspended islands to measure the thermal properties of nanoscale materials.106,107,120

With large thermal resistivity and stable performance, Pt RTDs are widespreadly used in microfluidic systems, especially in miniaturized PCR systems which require fast thermocycling and controlling. At first, the Pt RTDs were located outside of the silicon-based or silica-based PCR chambers, resulting in slow thermal response and inaccurate measurement result.84,121–123 In order to improve the temperature accuracy and heating/cooling performance of the systems, the Pt RTDs were later fabricated inside the reaction chamber with a thin SiO2 or SU-8 insulating layer.85,124–126 The thermal characteristics of Pt RTDs can be represented mathematically by the following equation, since there is a linear relationship between the resistance of the sensor and temperature:127

| (2) |

where is the RTD resistance (Ω) at temperature T (K), is the reference Pt RTD resistance (Ω) at reference temperature , and is the temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR) of the Pt RTD.

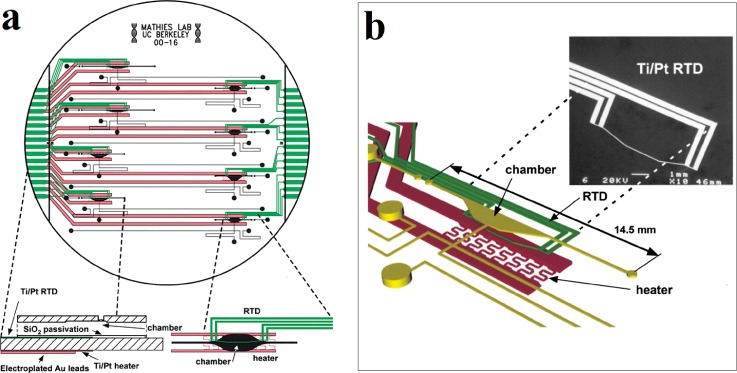

Lagally et al. micromachined a PCR-capillary electrophoresis system which integrated the DNA amplification and DNA analysis of capillary electrophoresis.45 By fabricating the heaters and Pt RTDs within the PCR chambers, accurate temperature monitoring with a variation of 0.5 K and fast heating and cooling rates of 20 °C/s were obtained in the small chambers with a reagent volume of 200 nl. Figure 3 provides an overview of the PCR-CE system design including the PCR chambers, the heaters, the RTDs, and their relative positions. With this system, multiplex amplification and detection of sex-specific markers from human genomic DNA within a time of only 15 min were achieved. In addition to stagnant PCR chambers, flow-through PCR systems with Pt RTDs for temperature measurement have also been extensively explored.128,129 Fukuba et al. fabricated a flow-through PCR device for in situ gene analysis.66 In this device, several constant-temperature zones were connected by the microchannels. Pt RTDs were deposited on the glass substrate to measure the temperature of ITO heaters.

FIG. 3.

An integrated PCR-capillary electrophoresis (PCR-CE) microsystem. (a) Overview of the PCR-CE system design including the chambers, heaters, and RTDs. An expanded structure diagram of a partial cross-section of the device is shown in the bottom left, and an expanded top view of the chamber zone is shown in the bottom right. (b) Perspective view of the chamber zone showing relative positions of the heater, RTD, and PCR chamber. The inset is a scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrograph of the RTD. Reprinted with permission from Lagally et al., Lab Chip 1(2), 102 (2001). Copyright 2001 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

In addition to Pt RTDs, Al RTDs83,130 and ITO sensors131,132 have also been applied in PCR systems. Zou et al. developed a multichamber system for the PCR of nucleic acids with high throughput.83 In this system, the Al RTDs provided a temperature measurement accuracy of ±0.1 K. In the capillary tube based PCR system made by Friedman et al., the ITO thin film works as both a heater and a thermosensor.132 The ITO temperature sensor had a temperature sensitivity of 4.7 K/Ω. With this set of temperature control system, the extracapillary temperature variation was within ±0.25 K, and the intracapillary temperature was regulated to within ±2 K.

RTDs have merits of easy fabrication, high sensitivity, and good stability. However, with a big size, they are not suitable for measuring small volume and transient temperature. And as active devices with a power supply on the order of milliampere, their self-heating effect may disturb the original temperature distributions.

4. Infrared thermography

Invasive thermometers measure the temperature only at a few discrete points or lines, which cannot decide the whole-field temperature of the PCR chambers. In addition, for invasive thermometers outside of the capillary or the substrate of a microfluidic system, the measured result is not very accurate, because the temperature outside of the system is not necessarily the same as that of the fluid inside the system. While for invasive thermometers inserted into the chambers, they may dramatically disturb the temperature distribution due to their own thermal mass and even induce sample cross-contamination. In order to overcome these problems, non-invasive thermometry, such as infrared (IR) thermography, has been developed for the temperature measurement in PCR systems.

IR thermography relies on monitoring the thermal radiation of a heated object in the infrared spectrum.77 Roper et al. introduced an infrared sensitive pyrometer for the completely non-contact temperature measurement of the glass surface above the 550-nl PCR chamber.87 It was calibrated against a thermocouple inserted into the PCR chamber. The result showed a time lag of less than 1 s between maximum heating rates of the solution and surface, which indicated a rapid thermal equilibrium. In fact, only a few references are based on IR thermography. Because the emissivity properties of the materials making up the system may interfere with the intrinsic radiation characteristics of the solvent and result in a low measurement accuracy. In most cases, the IR thermography is used for qualitative checking of the uniformity of the temperature field monitored by invasive thermometers.115,124,133,134 IR thermography takes the advantages of rapid response and continuous temperature readings. However, it uses wavelengths in the range of 0.7–20 μm, which greatly restricts its application in microfluidic systems. Because the solvents of biochemical reactions take place in water are highly absorbing beyond 1 μm.78 And limited by the diffraction, the spatial resolution of IR thermography is about a few microns.

5. Fluorescent dye

Both above-mentioned invasive and non-invasive thermometry cannot directly obtain the real-time temperature distribution of the solution in PCR systems with high accuracy. Therefore, great interest has been taken in developing novel semi-invasive thermometry in PCR microfluidics. Temperature-dependent fluorescent dye and transient thermochromic liquid crystal (TLC) have been introduced into the PCR microfluidics for the temperature measurement.

To date, there are many kinds of fluorescent dyes, such as rhodamine B,55,135 rhodamine 3B,136,137 and SYBR Green I.138,139 Among them, rhodamine B is a popular fluorescent dye for microscale thermal imaging in liquid systems. It is known to have a quantum yield that strongly temperature dependent is in the range of 0–100 °C, with the fluorescence intensity responses reversibly to temperature changes. Ross et al. used the rhodamine B with a standard fluorescence microscope and a CCD camera to measure the temperature increase in the buffer, which was induced by Joule heating.56 Limited by the image acquisition system, a spatial resolution of 1 μm and temporal resolution of 33 ms were obtained. In this method, the spatial resolution and temporal resolution depend primarily on the characteristics of the CCD camera. For typical devices, the spatial resolution and time resolution can be as good as micrometer and millisecond, respectively.56 In addition to the fluorescence intensity, the temperature-dependent fluorescence lifetime of rhodamine B can also be utilized to measure the temperature. Schaerli et al. fabricated a microfluidic system for the continuous flow PCR in microfluidic water-in-oil nanoliter droplets.72 In this system, rhodamine B was incorporated in the aqueous droplets to monitor the temperature inside moving droplets. The fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) of rhodamine B was obtained with a confocal microscope (Leica SP5) using supercontinuum laser generation as the excitation source and time-correlated single photon counting detection.

For temperature-dependent fluorescent dye, it is essential to maintain precise optical alignment during the entire experiment or else calibration will be lost. Furthermore, by comparing the fluorescence intensity and fluorescence lifetime of images at unknown temperatures with only one reference image at room temperature, this method includes the possibility of large systematic uncertainties, particularly at temperatures far from the reference temperature. And the fluorescence signal of fluorescent dye thermometers may be effected by the molecule concentration and phenomena such as photobleaching, absorption on the channel walls, thermophoresis, and/or thermally driven focusing. Therefore, this thermometry still has a low measurement accuracy.

6. Thermochromic liquid crystal

The thermochromic liquid crystal (TLC) is another type of semi-invasive thermometer.57 Their organic molecules demonstrate properties of both liquids and solids and exhibit a number of phases between the two extremes. The transition between phases is triggered by heat and results in temperature-sensitive liquid crystals exhibiting a range of colours, from colourless to the colours of visible spectrum in sequence (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet) and turn to colourless again beyond their thermal range. The process is reversed when the source of heat is removed. It is easy to change the temperature sensing range and sensitivity of TLCs by adjusting its compositions. Standard TLC products are available covering a temperature range of −30 °C–120 °C and a colour bandwidth from 0.5 °C to 40 °C allowing either a broad or precise temperature indication over a wide temperature range for the rapid accumulation of experimental data. The parameter used for temperature measurement is based on the wavelength of reflected light; hence, the method is not dependent on any absolute intensity level.

Noh et al. employed two TLCs (R50C10W and R67C10W) having the operating temperature centered at annealing temperature (55 °C) and extension temperature (72 °C), with a bandwidth of 10 °C.140 Their aqueous suspensions were placed in the microchamber of a silicon–glass PCR system to in situ monitor the temperature changes. It showed that the temperature variations along the center of the microchamber were less than 1.5 ± 0.5 °C and 3 ± 0.3 °C in the range of the annealing and the extension temperature, respectively. In order to overcome the barriers of TLCs which hinder their use in a dynamic mode, Hoang et al. demonstrated a novel TLCs-based method to track temperature transients during PCR.57 They employed three sets of custom-synthesized TLCs (R58C3W, R70C3W, and R93C3W); each could change reflected colour around one desired temperature for each PCR stage with a bandwidth of 3 °C. By analyzing the reflected spectra of TLCs as they undergo thermal cycling, the temperature versus time trajectory was computed.

TLCs can visually display the whole temperature field of microfluidic systems with small interference. They can provide an accuracy of 0.1–0.5 K with a response time of around 0.1 s over various temperature intervals. However, they show a narrow temperature display range of 0.5–5 K,74,141 except only one special case of 25 K (Ref. 142) has been reported. Since the temperature measured by TLCs is inferred from the probe hue140 or its wavelength of maximum reflectivity88 which are highly sensitive to the lighting and viewing angles, in situ calibration is always needed.143 In addition, TLCs are prepared in the form of encapsulated beads with diameters in the range of 10–150 μm,78 which limits their spatial resolution and application in miniaturized systems.

B. Thermometers in cell culture system

Cell culture is a process by which isolated cells are maintained under controlled conditions. These conditions include a suitable vessel, medium with essential nutrients, growth factors and hormones, and an appropriate physio-chemical environment (gas, temperature, pH, and ect.). Although culture conditions vary for each cell type, the typical temperature and gas mixture for mammalian cells are 37 °C and 5% CO2, respectively.

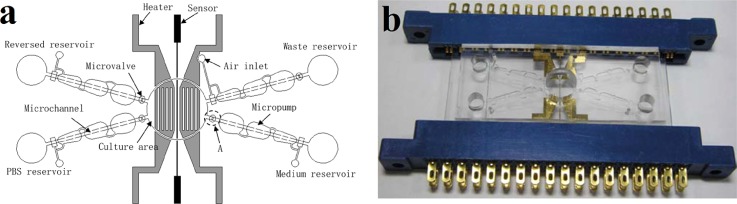

Therefore, a microfluidic system for mammalian cell culture needs accurate temperature controlling to maintain a constant temperature of 37 °C. Huang and Lee micromachined an automatic cell culture system which successfully performed a typical cell culturing process for human lung cancer cells (A549).82 In this system, Pt RTDs of 70 nm thick and ITO microheaters were used in cooperation with each other to maintain a temperature of 37 °C with a deviation within 0.1 K during the cell culturing process. In addition to Pt RTDs, the IR thermography was used to check the uniformity of the temperature distribution in the culture area. It showed a relatively uniformity of temperature distribution with a variation of 1 K when the heating system was activated. Figure 4(a) presents a schematic illustration of the automatic cell culture system. This system consists of a cell culture area, four micropumps, four microvalves, microchannels, reservoirs, two heaters, and a thermosensor. Figure 4(b) shows the photograph of the system with a pair of connector slots.

FIG. 4.

Automatic microfluidic system for cell culture. (a) Schematic of the automatic cell culture system. (b) Photograph of the automatic cell culture system with a pair of connector slots. Reprinted with permission from C. W. Huang and G. B. Lee, J. Micromech. Microeng. 17(7), 1266 (2007). Copyright 2007 IOP Publishing Ltd.

C. Thermometers in microreactor

Microreactors are devices in which different kinds of reactions take place in confined structures. Being studied in the field of micro process engineering, they provide great improvements in reaction speed, safety, scalability, reliability, and process control over conventional scale reactors. Microreactors have wide applications, such as chemical or biochemical reaction, material synthesis and purification, and analytical research.

1. Thin film thermocouple

With a wide temperature measurement range and a good built-in feature, thin film thermocouples (TFTC) can be integrated with miniaturized microreactors for temperature measurements. Allen et al. microfabricated built-in Ni/Ag TFTCs on a chemical microreactor to measure intrachannel temperature changes in different chemical reactions.144 These TFTCs were fabricated on the glass substrates based on spatially defined electroless deposition of metal with a poly (dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) mold, followed by annealing and electroplating. When calibrated in a water bath, they showed a thermopower of 16 μV/K over the range of 0–50 °C, with a sensitivity of 1 K. With the existence of heat dissipation in the system, the measured temperature rises for the neutralization reaction and H2O2 decomposition reaction was much lower than the theoretical values. Wang et al. fabricated Cr/Au TFTCs in freestanding microfluidic channels for temperature measurements of enzyme-catalyzed reaction detection with standard micro-nano processing technology.145 These TFTCs had a thermopower of 1.1 mV/K and a thermal time constant less than 100 ms.

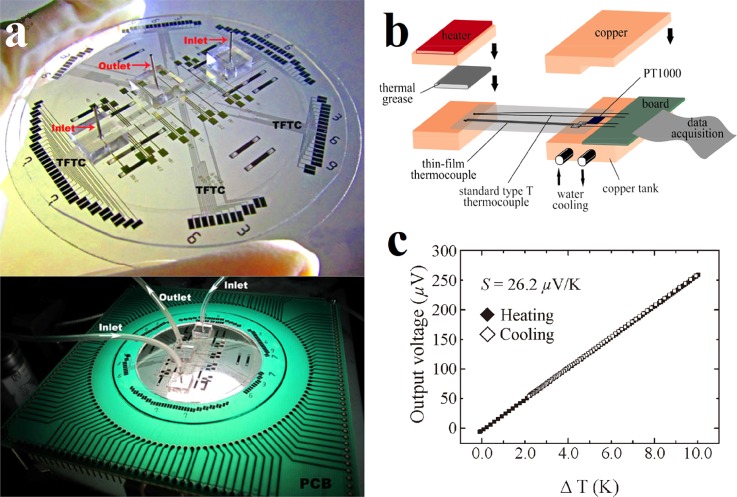

Our group has also made a lot of efforts in the research of TFTC and attempted to measure the temperature increment in neutralization reaction with TFTCs integrated in multilayered and multifunctional microfluidic system.79,80 In our strategy, Cr/Ni TFTC array was fabricated through standard bi-layer techniques of photolithography, development, metallic film deposition, and lift-off.98 To electrically isolate the TFTCs from the fluid, a thin layer of SiO2 or Si3N4 of 30–50 nm thick was deposited above the TFTCs layer. The Cr/Ni TFTCs array with a 100 nm thickness and 5 × 5 μm2 junction size was prepared on a glass substrate. The top panel of Fig. 5(a) is a photo image of the fabricated multifunctional microfluidic system. It consists of 70 Cr/Ni TFTCs, 32 electrodes for electrical measurements, and 3 electrolyte reservoirs connecting by microchannels with 2 inlets and 1 outlet. The bottom panel of Fig. 5(a) is a photograph of the system wire-bonded on a printed circuit board (PCB). The homemade calibration stage is shown in Fig. 5(b). It consists of a heating platform, a cooling system, and a standard T-type thermocouple. The calibrated thermopower of the TFTCs shown in Fig. 5(c) was about 26.2 μV/K, showing an excellent linearity and a good reproducibility. These TFTCs provided a thermal resolution better than 0.05 K. For the acid and alkali neutralization reaction experiment which took place in the as-fabricated microchannel, the maximal temperature rise measured was 0.4 K within 25 min. It was much less than the predicted value of 6.82 K. Such a deviation can be mainly attributed to four factors: the slow flow rate, the relative large heat dissipation, the insufficiency in mixing, and dozens of nanometers spacing between the TFTCs and the microchannels.

FIG. 5.

A multifunctional microfluidic system. (a) The top panel is a photo image of the multifunctional microfluidic system fabricated on a glass substrate. The bottom panel is a photograph of the microfluidic system wire bonded on a PCB and tested under a stereo microscope. Reprinted with permission from Sun et al., Adv. Mater. Res. 422, 29 (2012). Copyright 2012 Trans Tech Publications. (b) Schematic illustration of the homemade calibration stage. Reprinted with permission from Sun et al., Adv. Mater. Res. 422, 29 (2012). Copyright 2012 Trans Tech Publications. (c) Typical calibration curve of Cr/Ni TFTC in a thermal cycle of heating and cooling. Reprinted with permission from Liu et al., IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 32(11), 1606 (2011). Copyright 2011 IEEE.

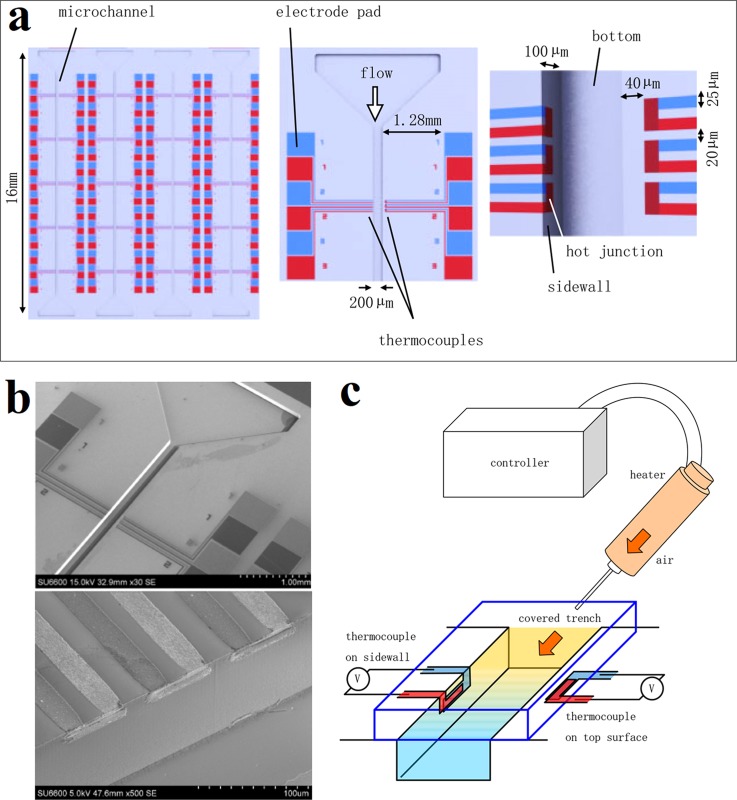

Generally, due to the structural restrictions, the microsensors are placed on top or bottom of micro-/nanochannel. However, one can see such an arrangement may seriously affect the measurement accuracy of local temperature from above description. Furthermore, if optical observation of the flowing material is needed, the existence of microsensors on top or bottom will disturb the observation. Yamaguchi et al. promoted a possible solution to this problem by fabricating the Cr/Al TFTCs on the sidewall of the silicon-based microchannel using 3D photolithography.146 Being different from the fabrication of planar devices, a spray-coating method was taken instead of the conventional spin-coating to deposit the photoresist uniformly. And an angled exposure technique was applied for the patterning, by tilting the sample to have the sidewall irradiated by UV light. Figure 6(a) schematically shows the design of the whole device. The photographs of magnified TFTC array and hot junctions are shown in Fig. 6(b). The thermopower of the TFTC was evaluated to be 16 μV/K. And the signal drift was about 0.12 μV/10 s. This three dimensional (3D) structure of TFTC on the device surface has the advantage of sensing the flow inside the microchannel directly, thus providing high temperature measurement accuracy.

FIG. 6.

A microfluidic system with TFTCs fabricated on trench sidewall. (a) Schematic of the device layout. The left panel is a whole design of the device. The middle panel is a set of TFTCs arrayed along the microchannel. The right panel is a magnified image of the hot junctions on the sidewall. (b) Magnified photographs of TFTC array and hot junctions. (c) Experimental setup for the dynamic performance measurement. Reprinted with permission from Yamaguchi et al., Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., Part 1 54(3), 030219 (2015). Copyright 2015 The Japan Society of Applied Physics.

Traditionally, a TFTC is made of two different material stripes. This bi-material TFTC may encounter with interface problem at the conducting contact junction. Our group had a very valuable discovery of the unexpected size effect in the thermopower of thin-film stripes, which can be utilized to solve the interface problem skillfully. It has been repeatedly observed that thermopower in centimeter-long metallic micro-stripes reduced with the width of stripe.147 Based on this phenomenon, we put forward the concept of single-metal thermocouple (SMTC). It is a monolithic thermal sensor made of a single layer of metallic film.148 SMTCs made from different metals with various stripe thicknesses and widths have been fabricated for the performance study.148–150 It has been found that the SMTC with a larger width ratio (wide strip to narrow strip) had a larger thermopower. The SMTC is interface-free and has a simplified fabrication and relatively high performance in accuracy and resolution. These advantages make SMTC a good candidate as a built-in thermal sensor for monitoring local temperatures in microfluidic systems.

2. Thin film thermopile

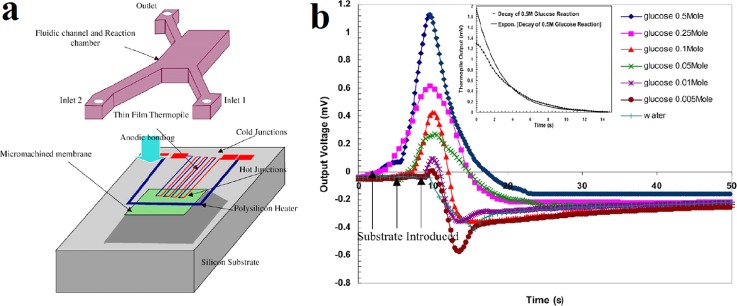

The thermal sensitivity of a TFTC mostly depends on the thermoelectric property of material. Therefore, semiconductor-based TFTCs with a large thermopower show higher thermal sensitivity than metallic TFTCs. However, compared to semiconductors whose electrical properties are highly process dependent, metals are still chosen over semiconductors for thermocouples applied in microfluidic systems. Because they have good compositional homogeneity, thermoelectric stability, and resistance to high temperature oxidation. To obtain high thermal sensitivity, a good practice is to cascade sets of low thermopower TFTCs together as a thin film thermopile. Zhang and Tadigadapa adopted this idea and made a microthermopile consisting of 16 doped polysilicon–gold (poly-Si/Au) TFTCs on a suspended Si3N4 platform to monitor the intrachamber temperature increases during enzymatic reactions.51 A 3D schematic illustration of the proposed device with integrated thin film thermopile, heater, microchannels, and reaction chamber is shown in Fig. 7(a).

FIG. 7.

Microreactor for the enzymatic reaction. (a) A 3D schematic of proposed device. (b) Output voltages of the thermopile for enzymatic reaction of glucose with concentration from 5 to 500 mM and for water. Reprinted with permission from Y. Zhang and S. Tadigadapa, Biosens. Bioelectron. 19(12), 1733 (2004). Copyright 2004 Elsevier B.V.

The thermopile was tested in situ with the integrated polysilicon heater. It showed a temperature responsivity of 4.7 mV/K and a thermal time constant less than 100 ms. A catalytic reaction of glucose to gluconic acid by glucose oxidase was implemented in this microreactor. Figure 7(b) shows the output voltages of the thermopile for the enzymatic reaction with different concentration glucose and reference test with pure water. One can see that the output voltage increases with the elevated concentration of the glucose solution. Still due to poor mixing and localized heat generation at the interface of substrate and enzyme, the measured temperature increase was about an order of magnitude lower than theoretically predicted value. Besides this type of thermopile, many other thermopiles made from different pairs of conductors, such as BiSb/Sb,67 Ti/Bi,151 Cr/Cu,152 Cr/Ni,153 and Au/Ni,154,155 have also been reported working as microcalorimeters for liquid applications.

This practice is also suitable to improve the thermal sensitivity of SMTC. For a single Ni dual-stripe SMTC with a wide stripe of 100 μm and a narrow stripe of 5 μm, it only has a thermopower of 0.91 μV/K. When cascaded 64 same SMTCs together, a thermopower of 55.69 μV/K is obtained, higher than that of the commercial type-K thermocouple (39.6 μV/K).156 Cascaded structures equip thermopiles with high thermal sensitivity. At the same time, they make that the thermopiles have a larger size compared with thermocouples.

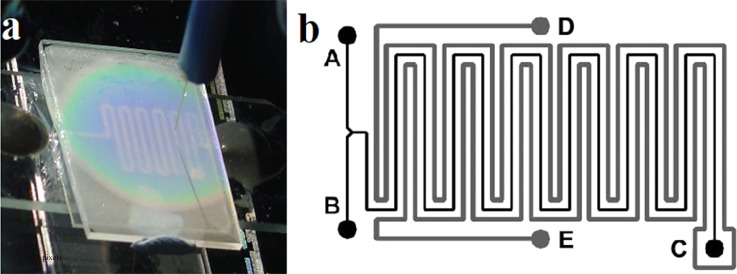

3. Thermochromic liquid crystal

In addition to invasive thermometers, TLCs are also applied in the chemical reactors. By introducing the TLC of R60C10 as a polymer bead slurry into one channel of a microfluidic reactor, Iles et al. measured the temperature of Reimer–Tiemann reaction.88 A thermal resolution better than 0.4 K was obtained in the measurements. Figure 8(a) shows the colour changes of R60C10 TLCs response to local temperature. Figure 8(b) schematically shows the channel pattern of the microfluidic reactor chip. A and B are two inlets of the reactor, C is the exhaust of the long serpentine reaction channel, and D and E are the inlet and the outlet of the channel filled with encapsulated TLC slurry.

FIG. 8.

Microfluidic reactor using TLC thermometer. (a) Thermal mapping of a microheater element using TLCs. (b) Schematic diagram of microfluidic reactor chip channel pattern. Reprinted with permission from Iles et al., Lab Chip 5(5), 540 (2005). Copyright 2005 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

D. Other thermometers in microfluidic system

Except the thermometers mentioned above, there are some other thermometers which can be used for temperature measurements in microfluidic systems, such as diode and liquid metals.

1. Diode temperature sensor

Diodes can be used for temperature sensing due to the strong temperature dependence of their forward bias voltage drop at a constant current.68 The forward voltage across a diode decreases, approximately linearly, with the increase in temperature. Many semiconductor materials have been reported in literature for diode temperature sensors, such as silicon, germanium, and selenium.157–159 Semiconductor diode thermometers measure the absolute temperature and exhibit high sensitivity and accuracy.48,159,160 Comparing with thermocouples and RTDs, diode temperature sensor arrays (DTSAs) can detect temperatures at numerous locations in a given area with a manageable number of lead wires and interconnection pads. Because the signals of the diodes can be obtained via scanning across the array.

Han and Kim fabricated a DTSA consisting of 1024 silicon diodes in an 8 mm × 8 mm surface area for temperature detection.52 This DTSA was made by the standard very large scale integration (VLSI) technique. The diodes in the array had good uniformity that each diode showed a thermal sensitivity of 20 mV/K at 10 μA. For a RTD or thermocouple array measured temperatures at 1024 points, 2048 interconnection pads were needed. While this DTSA only had 64 interconnection pads to measure temperatures at 1024 points. Camps et al. fabricated symmetrical polysilicon diode thermometers for the measurement of temperature variations through a microchannel with standard micro/nano-processing technology.161 In order to reduce the heat loss along the substrate, the diodes and thermal sources were fabricated on glass wafers. The measured thermal sensitivity of the polysilicon diode was about 55 mV/K. When they were integrated with PDMS microchannel and used to measure the temperature of mixing fluid of hot and cold water through the Y-shape microchannel, they showed good performance.

DTS has high sensitivity and DTSA needs much less interconnection pads than TFTC and RTD of the same detection points. However, as an active device, DTS can heat itself up by the forward-bias current and induce systematic errors.69 Towards the redundant 2N lead wires and interconnection pads of conventional TFTCs array, researchers invested several ways to weaken this limitation.162,163 By using a tree-like configuration, for instance, where all the leads of one material shared a common contact pad, an array consisting of N TFTCs could perform well with only N + 1 interconnection pads rather than 2N pads for the conventional configuration.164

2. Gallium-based liquid metal

Gallium-based liquid metal is another kind of RTD whose resistance increases linearly with the temperature.53 Due to high fluidity and electrical conductivity, it has recently become a promising material for fabricating miniaturized microfluidic components, including pumps,165 mixers,166 and heaters,167 in addition to thermometers.168 Injecting room temperature liquid metal into microchannels provides a simple, rapid, and low-cost way to integrate all the elements in a microfluidic device. Gao and Gui developed a microfluidic system integrated with liquid metal alloy GaIn20.5Sn13.5-based micro heaters, thermal sensors, and electroosmotic flow pumps.70 The thermometers were fabricated by conveniently injecting the liquid metal into a 20 μm wide, 50 μm high, and 5 mm long PDMS microchannel, with four 100 μm wide leading channels. Before the temperature measurement, they were calibrated in an oven at every 5 °C from 25 °C to 95 °C and showed a linear calibration curve with a slope of 0.64 mV/K. The temperature control performance of the device was tested with deionized water, and the experimental results showed that this device could effectively control the temperature in the range of 28–90 °C.

III. CELL TEMPERATURE MEASUREMENT

Cell temperature measurement is recently a hot research field in which various thermometers have been employed to measure cellular temperature on cell membrane,93 in cytoplasm,91 and on organelles.169,170 Temperature is such an important parameter that influences cell activities. Cells detect environmental temperature changes and response to them appropriately to maintain their inherent functions.171,172 In turn, biochemical reactions take place in cells vary intracellular temperature.34,173 An enhanced heat production has also been found in localized infections174,175 and cancers.176,177 Therefore, it is vitally necessary to develop precise cell temperature measurement approaches. To date, different kinds of thermometry for cell temperature measurement have been reported, including semi-invasive luminescent indicators42 and invasive thermocouple,178 resonant thermal sensor,54 and bimaterial microcantilever thermometer.72 The obtained results of cell temperature measurements can shed light on intricate cellular processes and promote the development of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques for some diseases.

A. Luminescent thermometry

With the investigation of thermometers for cell temperature measurements, one can see many good literatures on the modern nanothermometry, especially on luminescent thermometry.37,42,179–182 These reviews present an overview of the developments of luminescent nanothermometers and their applications in cell biology. The luminescent thermometers include nanoparticles,183 nanogels,184 fluorescent copolymers,185 nanodiamonds (NDs),186 quantum dots (QDs),59 green fluorescent proteins (GFPs),187 and so on. Utilizing their thermal related changes in the band-shape188 and bandwidth189 of fluorescence, fluorescence intensity,190 fluorescence lifetime,58 and fluorescence polarization anisotropy,191 these nanothermometers can be used to map the intercellular temperature and even to detect the temperatures of organelles.

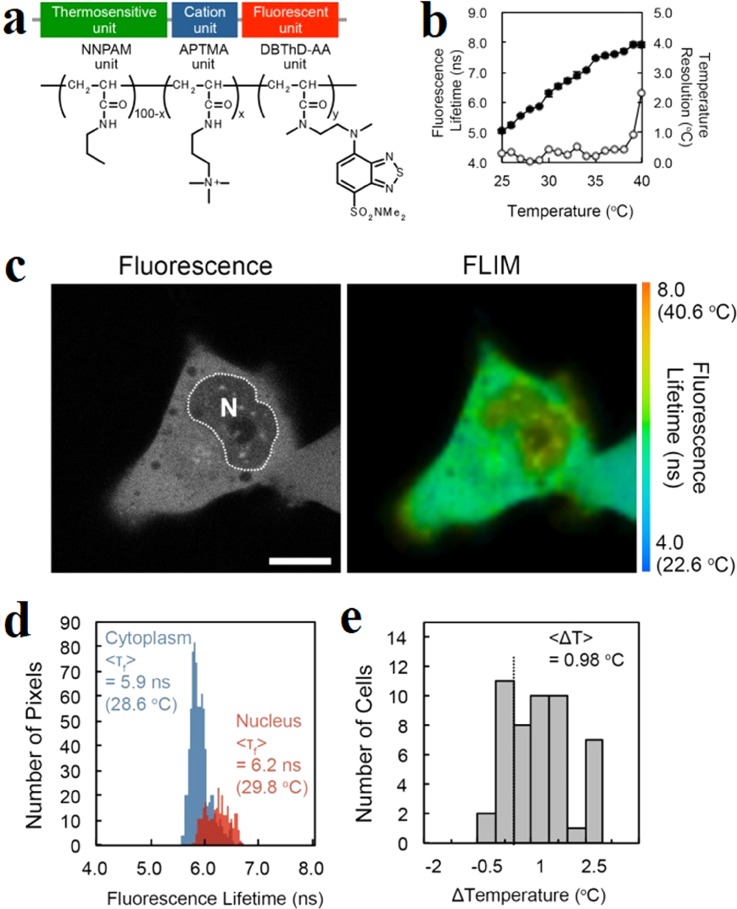

With a series of fluorescent polymeric thermometers (FPTs), Uchiyama et al. mapped the intracellular temperature of COS7,58 HeLa,75 NIH/3T3,75 HEK293T,192,193 and MOLT-4 cells.192 They discovered that the temperature in the nucleus was about 1 K higher than that in the cytoplasm among different cell lines. For the earlier FPT which was applied in COS7 cells, it contained a thermosensitive unit (NNPAM, poly-N-n-propylacrylamide), a hydrophilic unit (SPA, 3-sulfopropyl acrylate), and a fluorescent unit (DBD-AA, N-{2-[(7-N,N-dimethylaminosulfonyl)-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl](methyl)amino}ethyl-N-methylacrylamide).58 The fluorescence was quenched by water molecules in the swelling structure at a low temperature, leading to the reducing of the fluorescence lifetime. Therefore, the fluorescence lifetime of the FPT increases with the elevated temperature. This FPT showed a temperature resolution of 0.18–0.58 K. However, this type of FPT had difficulty being introduced into mammalian cells. In order to solve this problem, an improved cationic FPT (NN-AP2.5) consisting of a thermoresponsive unit (NNPAM), a fluorescent unit (DBD-AA), and a cationic unit (APTMA, (3-acrylamidopropyl) trimethylammonium) was developed.75 The chemical structure of this cell-permeable FPT is shown in Fig. 9(a). The cationic FPT displayed a temperature resolution of 0.05 K to 0.54 K within the range from 28 °C to 38 °C in HeLa cell extracts shown in Fig. 9(b). It could be uptaken from the extracellular matrix into a living cell. Figure 9(c) shows the intracellular temperature mapping of living HeLa cells with this FPT. The nucleus presented an obvious higher temperature than the cytoplasm with an average difference of 0.98 K as shown in Figs. 9(d) and 9(e). Due to the diffraction limitation of the fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), this series FPTs share a limited spatial resolution of 200 nm.

FIG. 9.

Intracellular temperature mapping of living HeLa cells with cell-permeable fluorescent polymeric thermometers (FPTs). (a) Chemical structure of the cell-permeable FPT. (b) Calibration curve (solid circle) and temperature resolution (open circle) of AP4-FPT in HeLa cell extracts. (c) Temperature mapping of living HeLa cells: confocal fluorescence images and fluorescence lifetime images of the cell-permeable FPT in a HeLa cell. (d) Histograms of the fluorescence lifetime in the nucleus (red) and in the cytoplasm (blue) in a cell in (c). (e) Histogram of the temperature difference between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Reprinted with permission from Hayashi et al., PLoS One 10(2), e0117677 (2015). Copyright 2015 Hayashi et al.

The phenomenon of heterogeneous temperature distribution in neuronal cells has also been reported. Tanimoto et al. measured the intracellular temperatures of SH-SY5Y (human derived neuronal cell line) with commercially available quantum dot-based nanoparticles.76 A fluorescence intensity ratio between the emission spectrum at 650–670 nm and emission spectrum at 630–650 nm was obtained by splitting the emission spectrum of a single quantum dot with a monochromator. The temperature measurement was based on the increments of the fluorescence intensity ratio with the elevated temperatures. The measurement results showed that the temperature in the cell body was 1.6 K higher than that in neurites. Although the size of the quantum dot was about 10–20 nm, this method provided a spatial resolution of 200 nm which was limited by the optical resolution of the confocal microscope.

Recently, with a temperature-sensitive fluorescent probe of Mito Thermo Yellow (MTY), Dominique et al. found that the mitochondria could physiologically maintain a temperature close to 50 °C at a constant external temperature of 38 °C both in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and primary skin fibroblasts.90 The MTY is a kind of rosamine compounds, whose fluorescence intensity declines rapidly in response to the increments of temperature. Arai et al. finalized the compound I31 as the mitochondrial specific dye after the screening of many rosamine compounds in live cells, taking into consideration of the photostability, brightness, organelle specificity, and temperature sensitivity.194 Compared with the rhodamine B, the MTY has a higher sensitivity of 2.7%/°C in living NIH3T3 cells.

B. Thermocouple probe

In addition to luminescent thermometry, several kinds of micropipette-based or metal-based thermocouple probes have been developed for the cell temperature measurement. As early as 1995, Fish et al. first produced a new class of submicrometer-size thermocouples based on micropipettes.195 Glass micropipettes containing a platinum core were vacuum-evaporated with thin gold film, forming the Au/Pt thermocouple junction at the tip. This thermocouple probe had a thermopower of 7 μV/K and a response time less than a few microseconds. Kakuta et al. developed another type of micropipette-based micro-thermocouple probe.196 The Au/Pt junction with an average thermoelectric power of 2.1 μV/K was constructed outside the tip of the micropipette by ion-sputtering with a polyimide layer between them acting as an insulating layer. Watanabe et al. first applied a Ni/Constantan micropipette-based submicrometer thermocouple to the measurement of cellular thermal responses of brown adipocytes.197 However, no significant temperature rise was obtained. Shrestha et al. improved the sensitivity of the micropipette-thermocouple probe for intracellular temperature measurement.178 The lead-free Sn alloy was injected inside a micropipette as a core metal and a nickel thin film was coated outside the micropipette to create a thermocouple junction at the tip. This Sn/Ni thermocouple probe had a temperature resolution of 0.01 K and a spatial resolution of 4 μm. To verify the feasibility of these thermocouples, they were injected into a living cell, which was exposed to a green laser beam (at 532 nm) for 1500 ms. It revealed a temperature rising time of around 600 ms.

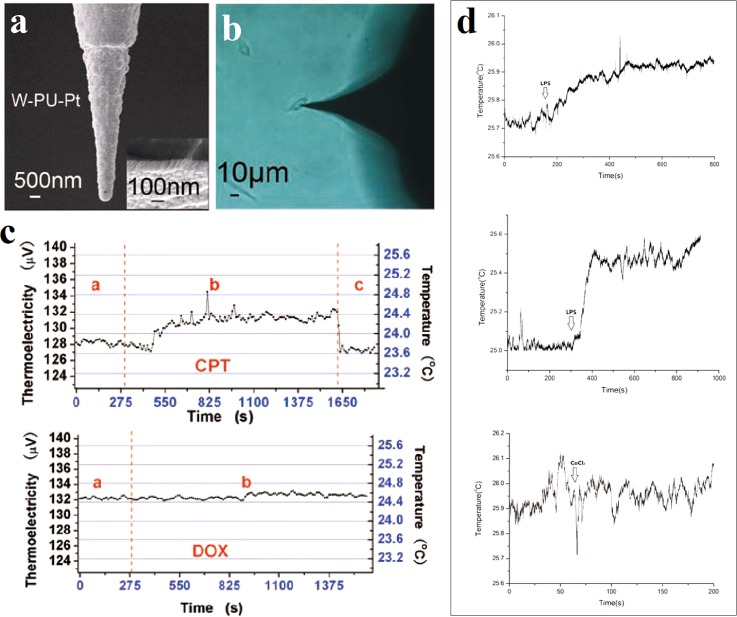

The metallic thermocouple probe can also be applied in the intracellular temperature measurement. Gu et al. promoted a sandwich thermocouple probe structure consisting of the tungsten (W) tip (inner core), an insulating layer made of polyurethane (PU) (interlayer), and a platinum (Pt) film (outer layer) as shown in Fig. 10(a).63,91 The thermal characteristics of the probe were calibrated in water bath. These Pt/W thermocouple probes provided a thermopower of 6–8 μV/K and a measurement accuracy of 0.1 K. They were precisely inserted into single cell with a micromanipulation system to monitor the intracellular temperature as shown in Fig. 10(b). From Fig. 10(c), after the treatment of camptothecin (CPT) in living U251 cells, a temperature increment of 0.6 ± 0.2 K was observed, but no obvious temperature variation was observed in the case of doxorubicin (DOX).63 In the case of single MLE-12 cell, different concentrations of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced different temperature increments, while cobalt chloride (CoCl2) did not cause obvious temperature changes, as shown in Fig. 10(d).91

FIG. 10.

Intracellular temperature measurement using a thermocouple probe. (a) SEM micrograph of the thermocouple probe. (b) Optical microscopic image of a living U251 cell inserted by the thermocouple probe. (c) Intracellular temperature changes of a single U251 cell after the treatment of 12 μM camptothecin (CPT, upper) and 50 μM doxorubicin (DOX, lower). Reprinted with permission from Wang et al., Cell Res. 21(10), 1517 (2011). Copyright 2011 IBCB, SIBS, CAS. (d) Intracellular temperature changes of a single MLE-12 cell after the treatments of 1 μg/l lipopolysaccharide (LPS, upper), 5 μg/l lipopolysaccharide (LPS, middle), and 200 μM cobalt chloride (CoCl2, lower). Reprinted with permission from Tian et al., Nanotechnology 26(35), 355501 (2015). Copyright 2015 IOP Publishing Ltd.

Recently, Rajagopal et al. fabricated a novel thermocouple probe supported by the silicon nitride (SiNx) cantilever of 5 μm tip diameter.92 It is a kind of Au/Pd thermocouple with 1 μm diameter junction targeting to serve as an intracellular thermometer in neurons. The TFTCs and thin film Au resistor heaters were first deposited on the Si/SiNx substrate by electron beam metal evaporation. After in situ calibration, the useless part of silicon substrate was etched by KOH solution, thus leaving silicon nitride cantilevers to support the TFTCs. The calibrated thermopower of Au/Pd TFTCs varies within the range of 0.8–1.3 μV/K, and the calculated response time was about 32 μs.

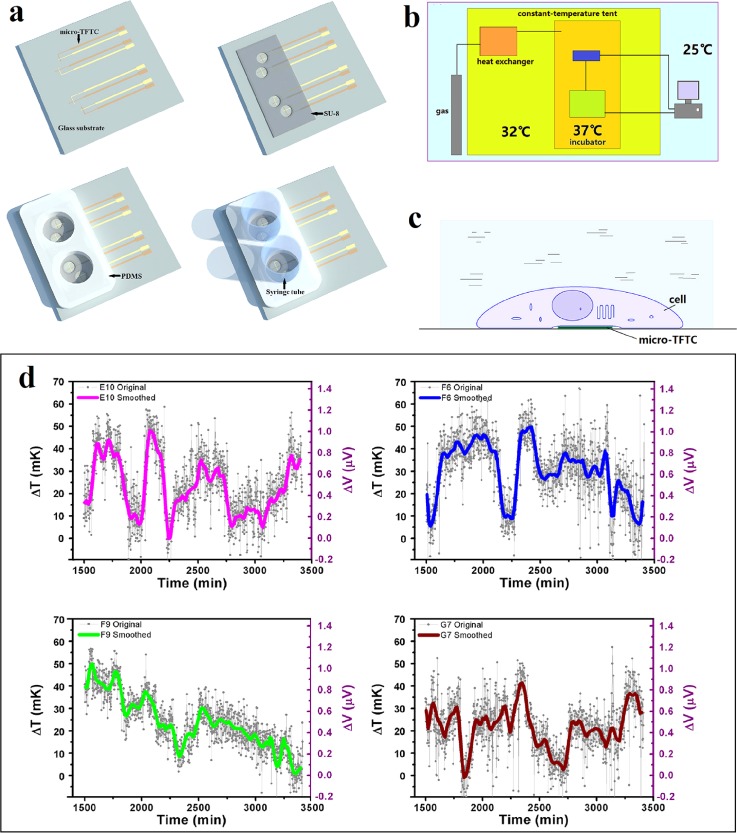

C. Thin film thermocouple

Thermocouple probes are capable of measuring intracellular temperatures. However, it can only monitor one point each time and induce cellular damage. Therefore, our group attempted to measure the local temperature increments induced by cultured HepG2 cells with micro-TFTCs.93 In this work, the Pd/Cr or Cr/Pt TFTCs with thermopowers of 20.99 ± 0.1 μV/K and 15.59 ± 0.3 μV/K were fabricated. Figure 11(a) presents the fabrication processes of the key elements of the cell temperature measurement device. It includes the deposition of the TFTC array, the definition of the “testing zone” with a SU-8 layer, the preparation and bonding of the culture medium reservoirs with a PDMS layer, and the fixation of the syringe tubes. By putting all the measurement instruments into the uniquely designed thermally double-stabilized constant-temperature measurement system as shown in Fig. 11(b), a reliable stability of ±5 mK was achieved. Once the adherent cells contact the micro-TFTC surface schematically presented in Fig. 11(c), the local temperature increment of the cell can be detected by the particular TFTC sensor underneath. With this system, tiny local temperature increments of 0–60 mK induced by the cellular activities of HepG2 cells under natural conditions were measured as shown in Fig. 11(d). In rare cases, an increment of local temperature in “testing zone” as much as 285 mK was monitored.

FIG. 11.

Extracellular temperature measurement with TFTC arrays. (a) Schematic illustration for the fabrication of the testing device. (b) Schematic presentation of the double-stabilized constant-temperature system. (c) Contact mode between a living cell and a micro-TFTC sensor. (d) Measured tiny local temperature increments in testing zones induced by cellular activities. Reprinted with permission from Yang et al., Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1721 (2017). Copyright 2017 Yang et al.

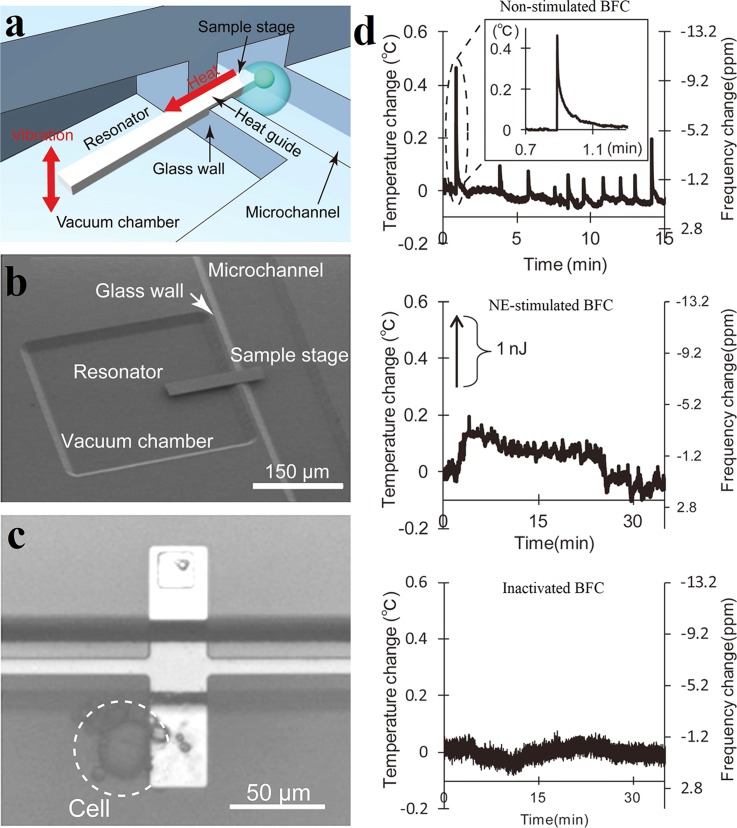

D. Resonant thermal sensor

The resonant thermal sensor is a novel thermometer whose measurement principle relies on the changes in the resonant frequency of the resonator induced by temperature variations. In 2012, Inomata et al. developed a pico calorimeter containing such a cantilevered heat-detecting Si resonator (resonant thermal sensor), which can measure the heat produced in a single cell.54 Fig. 12(a) schematically shows the microfluidic system with integrated Si resonant thermal sensor for the temperature measurement of living cells. One end of the Si cantilever is enclosed in the vacuum chamber acting as the resonator, while the other end is opened in the microchannel working as the sample stage. A glass wall separates the vacuum chamber and microchannel physically. When cells attached to the sample, the heat coming from the living cells is conducted from the open end to the resonator via a Si heat guide and results in a shift in the resonant frequency of the resonator. A SEM image of the Si resonator is shown in Fig. 12(b). The thermal resolution of the fabricated sensor was estimated as 1.6 mK. The ability of the device to measure heat from a single cell was assessed by measuring the heat production in the single norepinephrine (NE)-stimulated brown fat cell (BFC). In Fig. 12(c), a single BFC of 20 μm diameter attaches to the sample stage. The thermal responses of a BFC under different conditions are shown in Fig. 12(d). It can be seen that sporadical heat signals were generated in non-stimulated cell over short time intervals. And the NE-stimulated BFC showed a continuous heat production over approximately 20 min; however, no obvious temperature change was observed in inactivated cell. In addition to cantilevered Si resonator thermal detection system, Inomata et al. fabricated another double-supported type microfluidic system for the extracellular heat detection.94 Compared with the cantilevered type, the double-supported type Si resonator has a larger temperature coefficient and a higher thermal resolution of 79 μK. However, it presents low stability during oscillations due to the low vibration amplitude and the interference of surrounding temperature conditions.

FIG. 12.

Extracellular temperature measurement with Si resonant thermal sensors. (a) Schematic image of the Si resonant thermal sensor in microfluidic system for cell temperature detection. (b) SEM photograph of the microfluidic system with integrated Si cantilever. (c) A BFC attaches to the sample stage. (d) The thermal responses of BFCs under different conditions, including natural condition (upper), NE-stimulated BFC (middle), and inactivated BFC (lower). Reprinted with permission from Inomata et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 100(15), 2766 (2012). Copyright 2012 American Institute of Physics.

For this measurement system, the cell may be exhausted of dissolved oxygen due to limited solution in the system, thus affecting the heat generation in cells. In addition, there exist large heat losses to the surroundings and excessive damping in liquid. Therefore, this alternative means of extracellular temperature measurement has a low measurement accuracy.

E. Bimaterial microcantilever thermometer

The bimaterial microcantilever beam is an important microelectromechanical system structure used for thermal measurements in the air or a fluid. The variation in temperature results in the deflection of the bimaterial cantilever beam at the free end due to the different thermal expansion coefficients of the double materials. The key factor of the high sensitivity is the small dimensions and thermal mass of the bimaterial cantilever beam in combination with current optical methods to monitor the bending with high accuracy.

The bimaterial cantilever beam was first introduced as a calorimeter to measure the heat generated by chemical reactions with power and energy resolutions in the range of 1 nW and 1 pJ, respectively.55 This bimaterial cantilever consisted of a silicon nitride cantilever and an aluminum coating layer. Toda et al. fabricated another kind of biomaterial microcantilever formed by layers of silicon nitride and gold and applied it to measure the temperature of Brown Adipocytes.71,95 A linear relationship between the displacement of the microcantilever tip and the temperature change of the buffer, with a slope of 9.15 ± 0.01 μm/K, was obtained in a hot water bath, and the temperature resolution was estimated as 0.7 mK. With the stimulus of norepinephrine, a maximum temperature change of 0.217 ± 0.12 K for each cell was measured.

The bimaterial cantilever beam measures the temperature of several cells instead of a single cell, thus it cannot present the cell temperature at single cell level. In addition, the cells under test are always in a free state and cannot come in close contact with the bimaterial microcantilever. Therefore, the measurement results may be inaccurate and a long period cell temperature measurement is impossible with this thermometer.

IV. DISCUSSIONS

We now discuss several critical technical issues in local temperature measurements of micro-nano-fluidic systems and individual live cells.

A. System noise

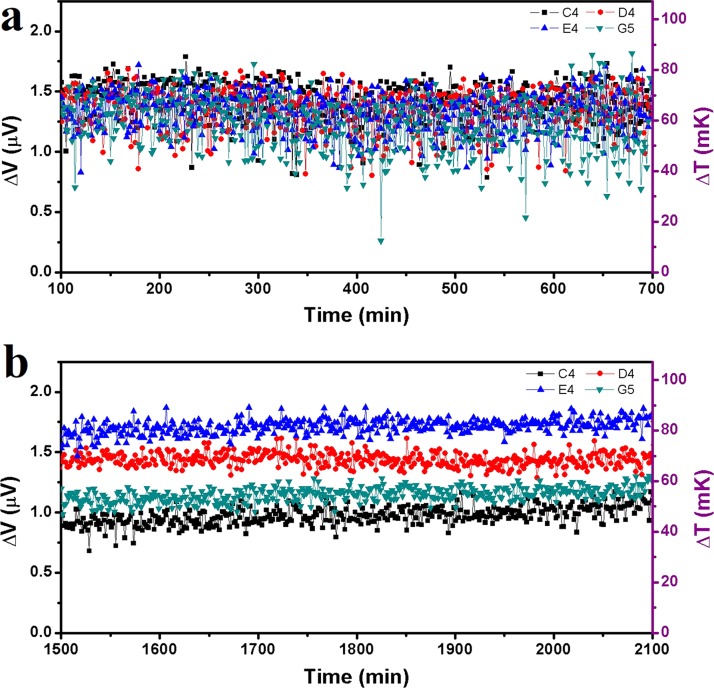

Noise is one of the major factors that may lead to the failure of temperature measurements at the micro-nano-scales. In a particular experiment, noises may come from the environment, the testing device, and the system. For instance, in the measurement of U251 cells as shown in Ref. 63, the system noise was about 50 mK. With such a noise, it was hard to detect a small change of temperature at the order of 10 mK. In our recent work, we managed to build a thermally double-stabilized constant-temperature system, where the cell-culture and testing devices, a multiplexer, a Keithley 2182A nanovoltmeter, and so on were all put into a large incubator, and the incubator was put inside a thermally stabilized tent.93 In this way, the original system noise of ±25 mK in a normal laboratory was reduced to ±5 mK, as shown in Fig. 13. With such a specially designed system, slight increments of local temperatures within 10–60 mK of individual HepG2 cells were observed, where the cells grew adhesively on top of the built-in thermal sensors on the substrate.

FIG. 13.

Thermal fluctuations of Pd/Cr micro-TFTCs under different conditions. (a) Thermal fluctuations of micro-TFTCs C4, D4, E4, and G5 which were tested in an ordinary laboratory. The room temperature was maintained at 25 °C and the sensors were exposed to the air. (b) Thermal fluctuations of the same TFTCs which were tested in the double-stabilized constant-temperature system. The system temperature was maintained at 32 °C and the sensors were covered by culture medium. Reprinted with permission from Yang et al., Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1721 (2017). Copyright 2017 Yang et al.

The thermally double-stabilized constant-temperature system is applicable to systems that are set at a constant temperature. In other cases, by increasing the times for repeated measurements, it is also feasible to remarkably increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Lee et al. set a good example. When performing thermal measurements for a molecular device with nanoscale–thermocouple integrated scanning tunnelling probes (NTISTPs), by repeating over 6000 times, they obtained a temperature resolution of 0.3 mK and observed unbalanced temperature increment within 15 mK for the two nano-tips that held the molecules under test.198

B. The difference between measured data and actual temperature of the subject under test

Water has a large specific thermal capacitance of 1.0 c/g·K and a very small thermal conductivity of 0.6 W/m·K at room temperature. For sensing local temperature of a subject in water, it requires a thermal diffusion from the subject under test to the sensor, via a layer of water with varied thickness. Therefore, a difference between measured data and the actual temperature of the subject under test always exists.

Non-invasive thermometers use QDs, nanogels, or GFPs as indicators. Benefitting from the small thermal capacitance of the nano indicators, these approaches are capable of sensing the local temperatures of sub-cell organelles.199–201 Yet fluorescence-based thermometers are sensitive to multiparameters, such as pH, ion concentration, and solution viscosity. The intercellular temperature results obtained with these thermometers raised debates.202,203 Furthermore, as limited by photobleaching and instability under an intracellular environment, some thermometers like organic fluorophores are not suitable for continuous detections that span several days. In addition, all the luminescent methods need additional light sources, which induce extra heat to the cells during the measurement processes. Therefore, measurement results of the non-invasive thermometers often give relative intracellular temperature distribution rather than absolute cellular temperature. A possible solution could be a hybrid measurement technique, where a non-invasive thermometer is used with a micro-TFTC array at the same time. In this way, a better in situ calibration of the absolute local temperature could be expected. Homma et al. presented such an alternative method. They prepared a mitochondria-targeted ratiometric temperature probe (Mito-RTP) composed of rhodamine B dye and Changsha near infrared (CS NIR) dye.170 Since the fluorescence intensity of the rhodamine B decreases with the elevated temperature and the fluorescence intensity of CS NIR dye keeps constant at various physiological temperatures, these two fluorophores were coupled to provide a declined fluorescence intensity ratio with increasing temperature. Therefore, this Mito-RTP could be insensitive to changes in pH, ion concentration, and other environmental parameters. This strategy is also effective for the QDs thermometer. Vlaskin et al. developed a Mn2+-doped ZnSe dual-emission QDs whose luminescence results from two distinct but interconnected excited states.89 The exciton emission band of the QDs at ∼520 nm increases, while the Mn2+ emission band at ∼600 nm decreases with increasing temperature, resulting an increased intensity ratio with the elevated temperature. This dual-emission mode can eliminate the effect of photobleaching, concentration and background noise from biological environments. All of these provide valuable clues for the further development of fluorescence thermometry.

In many cases, direct measurement is required for the local temperature of a micro-fluid. Then, enhancing the thermal contact between the thermometer and fluid and reducing the influence of thermal dissipation through the substrate under thermometers become two crucial factors.

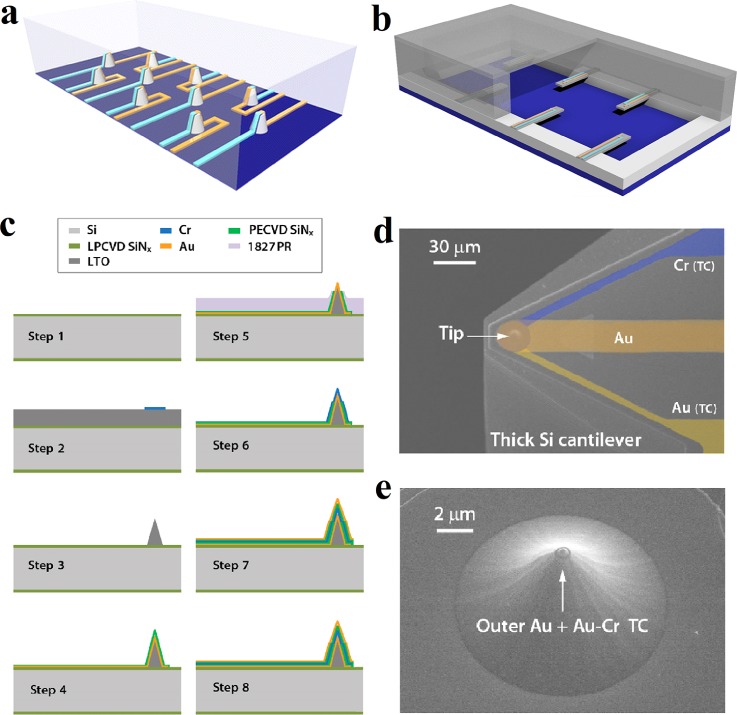

Figure 14 presents two solutions, where 3D vertical thermometers [Fig. 14(a)] and beam-like thermometers [Fig. 14(b)] are fabricated for the enhancement of thermal contact. They all require sophisticated device fabrication techniques, yet these techniques are within the scope of standard cleanroom technology for semiconductor devices. Figure 14(c) plots a complete sequence of processes for fabricating such a vertical sensor.198 In detail, the fabrication starts from the deposition of a 500 nm thick layer of low-stress low pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) SiNx. Then, an 8 μm thick layer of low temperature silicon oxide (LTO) is deposited. By etching in buffered HF, a LTO probe tip is fabricated. After that, the first Au line (Cr/Au: 5/90 nm) is fabricated by sputtering and etching, followed by the deposition of the first 70 nm thick layer of plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) SiNx. By sputtering and etching, a Cr line (90 nm thick) is fabricated in step 6. After the deposition of the second 70 nm thick layer of PECVD SiNx, the whole process is completed by the fabrication of the second Au line (Cr/Au: 5/90 nm) through sputtering and etching. This sensor was designed and used for precise thermal measurements in molecular devices. However, by skipping the last step for deposition of top Au layer, such a 3D sensor seems a good candidate for the measurement of local temperature of a micro-fluid. The SEM images of a nanoscale–thermocouple integrated scanning tunnelling probe (NTISTP) which integrated with a nanoscale thermocouple and the tip of a fabricated NTISTP are shown in Figs. 14(d) and 14(e), respectively.

FIG. 14.

Free-standing micro-TFTCs in the microfluidic system with high thermal sensitivity. (a) Protuberant temperature sensors on the substrate. (b) Cantilevered thermal probes on the sidewalls. (c) Fabrication steps of the NTISTPs. (d) SEM image of a NTISTP probe with nanoscale thermocouple. The false coloring shows the metal layers (Au, Cr) that comprise the thermocouple (TC) and the outermost Au metal layer. (e) SEM image of the tip of a fabricated NTISTP. Reprinted with permission from Lee et al., Nature 498(7453), 209 (2013). Copyright 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited.

When the thermometers are fabricated on a thick substrate, the substrate could dissipate a major amount of heat, thus remarkably reducing the sensitivity of the thermometers. To reduce the influence of thermal dissipation through the substrate, a feasible solution is to insert a thermal insulating layer between the thermometer and the substrate. Parylene is a good candidate for such an insulating layer, as it has a thermal conductivity of only 0.082 W/m·K.204,205 Another solution is to fabricate temperature sensor arrays on freestanding Si3N4 thin-film windows.206,207 Previous results had shown that, compared with TFTCs made on 500 micron-thick Si substrates, the same TFTCs made on 400 nm thick freestanding Si3N4 thin-film windows increased their thermal sensitivity by a factor of 20–100 times under the same irradiation of electron beams or laser beams.207

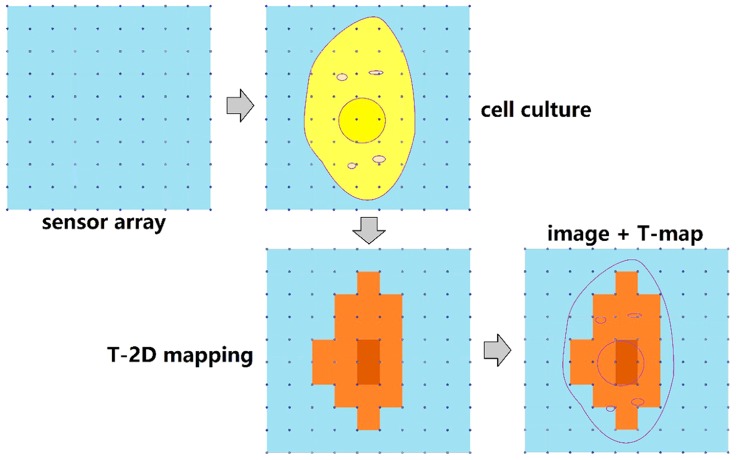

Finally, by minimizing the dimension of TFTC and increasing the number of TFTCs in certain area, it is possible to obtain better solutions and accuracy for local sensing temperatures. Figure 15 schematically presents a proposal for measuring the temperature distribution of a single cell. The nanoscale TFTC array is fabricated on a suspended platform. This temperature sensor array consists of 100 nano-sized TFTCs, so that a single cell may cover more than 10 TFTCs when it adheres to the sensor array. With high thermal sensitivity, the TFTCs are capable of sensing tiny local temperature differences on cell membrane at different sites. By monitoring the optical images of the cells inside the incubator in real-time and comparing the thermal measurement results with the real-time imaging, one can ensure that the temperature increments result from the cell activities. Progress in this direction is ongoing in our labs.

FIG. 15.

Schematic illustrations of the two-dimensional (2D) temperature mapping of a single cell.

V. CONCLUSION

In summary, we briefly reviewed a variety of technical aspects in regard to local temperature measurement for microfluidic systems and individual cells. Liquid environments, small subject sizes, large noises at room temperature, and tiny expected changes in temperature usually all make reliable and precise local thermal measurement a challenging task. Compared with non-invasive approaches, invasive micro-nano-thermometers such as TFTCs and TC probes have higher thermal resolutions, higher accuracy, and faster responses, but it is difficult to make them on a nanometer scale; therefore, these sensors have limited spatial resolutions. Non-invasive thermometers, such as the photoluminescence approach, use QDs, nanogels, or GFPs as the thermal indicators and are capable of directly indicating the local temperature with a very high spatial resolution at the sub-cell level. We discussed the feasible approaches for reducing system noises, to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, and to minimize the difference between measured data and actual temperature of the subject under test. For instance, mounting the sensors on freestanding Si3N4 thin-film window, or fabricating 3D vertical sensors inside the fluidic channel. With the rapid development of lab-on-a-chip systems and research on single cells, there is plenty of room for the optimization and novel development of applicable micro-nano-thermometry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFA0701302) and the MOST of China (Grant No. 2016YFA0200800).

Contributor Information

Xiaoye Huo, Email: .

Shengyong Xu, Email: .

References

- 1. Mark D., Haeberle S., Roth G., von Stetten F., and Zengerle R., “ Microfluidic lab-on-a-chip platforms: Requirements, characteristics and applications,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 39(3), 1153 (2010). 10.1039/b820557b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abgrall P. and Gue A. M., “ Lab-on-chip technologies: Making a microfluidic network and coupling it into a complete microsystem - A review,” J. Micromech. Microeng. 17(5), R15 (2007). 10.1088/0960-1317/17/5/R01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haeberle S. and Zengerle R., “ Microfluidic platforms for lab-on-a-chip applications,” Lab Chip 7(9), 1094 (2007). 10.1039/b706364b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sackmann E. K., Fulton A. L., and Beebe D. J., “ The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research,” Nature 507(7491), 181 (2014). 10.1038/nature13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Temiz Y., Lovchik R. D., Kaigala G. V., and Delamarche E., “ Lab-on-a-chip devices: How to close and plug the lab?,” Microelectron. Eng. 132, 156 (2015). 10.1016/j.mee.2014.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woolley A. T., Hadley D., Landre P., Demello A. J., Mathies R. A., and Northrup M. A., “ Functional integration of PCR amplification and capillary electrophoresis in a microfabricated DNA analysis device,” Anal. Chem. 68(23), 4081 (1996). 10.1021/ac960718q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lagally E. T., Simpson P. C., and Mathies R. A., “ Monolithic integrated microfluidic DNA amplification and capillary electrophoresis analysis system,” Sens. Actuators, B 63(3), 138 (2000). 10.1016/S0925-4005(00)00350-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mcdonald J. C., Duffy D. C., Anderson J. R., Chiu D. T., Wu H., Schueller O. J. A., and Whitesides G. M., “ Fabrication of microfluidic systems in poly(dimethylsiloxane),” Electrophoresis 21(1), 27 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lafleur J. P., Joensson A., Senkbeil S., and Kutter J. P., “ Recent advances in lab-on-a-chip for biosensing applications,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 76, 213 (2016). 10.1016/j.bios.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Kan J. A., Zhang C., Malar P. P., and van der Maarel J. R. C., “ High throughput fabrication of disposable nanofluidic lab-on-chip devices for single molecule studies,” Biomicrofluidics 6(3), 036502 (2012). 10.1063/1.4740231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]