Abstract

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) is a central modulator of cell metabolism. It regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism. Modifications and adaptations in cellular metabolism are hallmarks of cancer cells, thus, it is not surprising that PGC-1α plays a role in cancer. Several recent articles have shown that PGC-1α expression is altered in tumors and metastasis in relation to modifications in cellular metabolism. The potential uses of PGC-1α as a therapeutic target and a biomarker of the advanced form of cancer will be summarized in this review.

Keywords: PGC1 alpha, prostate cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, metabolism, mitochondria

Introduction

Modifications and adaptations in cellular metabolism are hallmarks of cancer cells. After the pioneering discovery, made by Otto Warburg, showing that cancer cells preferentially use glycolysis to meet their energetic needs, several studies have shown that cancer cells have an altered metabolism compared to normal cells. Recent findings have elucidated the metabolic changes, also termed metabolic reprogramming, occurring in cancer cells in response to environmental challenges such as hypoxia, nutrient scarcity, increased radical oxygen species (ROS), or pH modifications [1,2]. These metabolic adaptations confer resistance to apoptosis and are required to sustain rapid cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Thus, interfering with cancer cell metabolism with drugs such as metformin (an inhibitor of the complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain), or 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; an inhibitor of glycolysis), has been shown to decrease tumor growth and induce apoptosis in several cancer cells types [3-7].

One of the major and well-described modulators of cell metabolism is a member of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1) transcriptional co-activator family: PGC-1α. PGC-1α is implicated in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism. It is therefore not surprising that alterations in the activity and expression of PGC-1α are associated with many diseases in different tissues. It is well established that PGC-1α is implicated in diabetes, neurodegeneration and cardiovascular disease [8,9], but several recent articles, discussed below, have also revealed that PGC-1α plays an important role in cancer. In this review, after an overview of PGC-1α, we will discuss the latest results concerning the role of this coactivator in tumorigenesis and the formation of metastases.

PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator and a member of the PGC-1 protein family

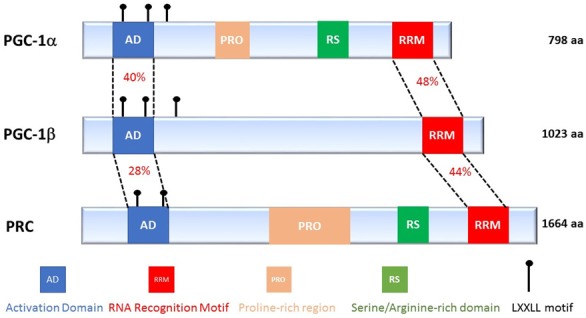

The PGC-1 family is composed of three members, PGC-1α, PGC-1β and PRC (PGC-1-related coactivator), which share common structural features and modes of action (Figure 1). The first member of the PGC-1 family, PGC-1α, was identified in the late 1990s and found to interact with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) transcription factor in brown adipose tissue, a tissue rich in mitochondria and specialized in thermogenesis [10]. PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator whose expression is induced in response to cold exposure in brown adipose tissue, and in skeletal muscle in association with the expression of decoupling mitochondrial proteins (UCPs: uncoupling proteins). PGC-1β is the closest homologue of PGC-1α. They share high sequence identity [11,12], especially across several distinct domains including an N-terminal activation domain (40% homology), a central regulatory domain (35%) and a C-terminal RNA binding domain (48%). Both coactivators are highly expressed in oxidative tissues such as brown adipose tissue, heart, kidney, skeletal muscle and brain [13]. PRC is ubiquitously expressed and shares lower levels of homology with the two other members of the family (Figure 1) [14]. Of note, splice variants of PGC-1α (NT-PGC-1α and PGC-1α 1-4) have been identified in skeletal muscle and their role and function remain poorly described [15].

Figure 1.

The PGC-1 protein family members. Schematic representation of the three members of the PGC-1 family, indicating their different regions and the % of homology between each member in the N and C-terminal region of the co-activators.

The N-terminus of these coactivators contains a transcriptional activation domain as well as an important motif for interactions with nuclear receptors: the leucine-rich LXXLL motif [16]. The C-terminal domain has the highest homology between the three PGC-1 coactivators and includes an RNA recognition and binding site (RRM, RNA recognition motif) and a domain rich in serine and arginine (RS, serine/arginine-rich domain) [11,12]. These two domains are known to be involved in post-transcriptional modifications of RNA [17]. Sequence analyses revealed that the PGC-1 family is conserved in many species, including primates, rodents, ruminants, birds, amphibians and fish.

PGC-1 coactivators act as transcriptional regulators but do not have a DNA-binding domain. They bind to various transcription factors and nuclear receptors that recognize specific sequences in their target genes. While other transcriptional coactivators possess intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity that facilitates chromatin remodeling and gene transcription, members of the PGC-1 family lack enzymatic activity. Therefore, PGC-1 coactivators exert their modulatory function on gene transcription by acting as an anchor platform for other proteins with histone acetyltransferase activity and by promoting the assembly of transcriptional machinery to trigger gene transcription.

The N-terminal region of PGC-1α has several LXXLL leucine-rich motifs, also called NR boxes, which are crucial for interactions between PGC-1α and a wide variety of nuclear receptors and transcription factors (Figure 1). Among these transcription factors, PPARα [18], the estrogen receptor (ER) [19], retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) [20], the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [21], the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 α (HNF4α), nuclear respiratory factor 1 and 2 (NRF1/NRF), and sterol regulatory element-binding proteins 1 and 2 (SREBP1/2) are known to regulate the expression of genes implicated in several functions of cellular metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main transcription factors interacting with PGC-1α

| Transcription Factor | Function, Role | References |

|---|---|---|

| NRF1/NRF2 | Mitochondrial biogenesis | [104,105] |

| PPARα/PPARβ | Mitochondrial biogenesis; Fatty acid oxidation | [106,107] |

| PPARγ | Mitochondrial biogenesis; UCP1 expression | [10,57,108-110] |

| ERRα/ERRβ | Mitochondrial biogenesis | [111,112] |

| TRβ | CPT1 expression | [113,114] |

| FXR | Triglyceride metabolism | [115] |

| LXRα/LXRβ | Lipoprotein secretion | [116,117] |

| GR; HNF4α; FOXO1 | Neoglucogenesis | [11,12,28,118] |

| MEF2 | Muscle fiber type1 gene regulation | [59,119] |

| Erα/Erβ; PXR | Unknown | [11,120] |

| SREPB1/SREBP2 | Lipogenesis; Lipoprotein secretion | [116] |

| Sox9 | Chondrogenesis | [121] |

PGC-1α is a metabolic sensor of environmental stresses

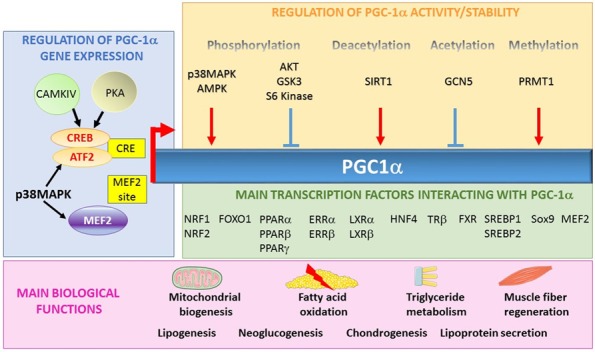

The expression and activity of PGC-1α are controlled by environmental and physiological stimuli. Temperature, more specifically the response to cold, is a major inducer of PGC-1α expression in brown adipose tissue and muscle via the cAMP signaling pathway and activation of protein kinase A (PKA) [10]. The expression of PGC-1α is also increased in muscle after exercise, via activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMKIV) and calcineurin A. Another mechanism known for regulating the expression of PGC-1α in muscles after exercise involves the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK protein) and phosphorylation of the myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) and activating-transcription factor 2 (ATF2) transcription factors [22-24].

PGC-1α is very sensitive to the energy status of the cell. It is finely regulated by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a sensor of cellular AMP levels. AMPK is activated in muscle tissue during exercise and increases mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism. The mitochondrial activation that is mediated by AMPK requires PGC-1α activity [25,26]. Similarly, fasting is another environmental signal that is known to regulate the expression of PGC-1α. In liver, the expression of PGC-1α is increased in response to glucagon, a pancreatic hormone that induces activation of cAMP and CREB [27]. This induction of PGC-1α in the liver during fasting leads to an increase in the expression of gluconeogenesis genes that promotes the production of hepatic glucose and maintains glucose homeostasis [28] via the association of PGC-1α with transcription factors, such as HNF4α [29] or forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) [30].

The transcriptional activity of PGC-1α can also be modulated by post-translational modifications that positively or negatively affect its ability to recruit complexes capable of remodeling chromatin and activating gene transcription. These post-translational modifications include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination and are able to not only modulate the intensity of the response mediated by PGC-1α, but also to determine which transcription factor will interact with PGC-1α.

PGC-1α is phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues at different sites by several kinases. The most well characterized of these kinases are p38 AMPK [26,31,32], AKT [33], AMPK [34], S6 kinase (ribosomal protein S6 kinase) [35] and GSK3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3β) [36]. The phosphorylation of these specific residues can lead to the activation of PGC-1α, as is observed for p38 MAPK and AMPK, which stabilize or activate PGC-1α, respectively [26,34]. In contrast, they can also induce the inhibition of PGC-1α, for example, Akt inhibits PGC-1α activity and GSK3β increases the proteasomal degradation of PGC-1α [36]. Finally, phosphorylation by S6 kinase prevents the interaction between PGC-1α and HNF4α (Figure 2) [35].

Figure 2.

PGC-1α, a co-activator implicated in several biological functions. PGC-1α gene expression is mainly regulated by three transcription factors (CREB, ATF2 and MEF2) that bind to the CREB-responsive element (CRE) and myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2). The protein is also regulated by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, deacetylation, acetylation and methylation. PGC-1α interacts with numerous transcription factors and is implicated in several biological functions.

PGC-1α is also regulated by the action of deacetylases and acetylases. For instance, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activates PGC-1α by the deacetylation of the lysine residues [37,38] and GCN5 (lysine acetyltransferase 2A) acetylates and inactivates PGC-1α [39]. PGC-1α is also activated following the methylation of arginine residues in the C-terminal position by PRMT1 (protein arginine methyltransferase 1) [40].

PGC-1α is a master regulator of oxidative metabolism

One of the main functions of PGC-1α is the control of energy metabolism, which is achieved by acting both on mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation. This is confirmed by numerous in vitro and in vivo studies that have demonstrated that PGC-1α is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis. In fact, overexpression of PGC-1α in adipocytes, muscle cells, cardiac myocytes and osteoblasts leads to an increase in the amount of mitochondrial DNA [41-44]. PGC-1α initiates mitochondrial biogenesis by activating transcription factors that regulate the expression of mitochondrial proteins that are encoded by nuclear DNA [45]. Mitochondrial DNA encodes some protein subunits of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and proteins that are required for mitochondrial protein synthesis. All other mitochondrial proteins are encoded by nuclear DNA and therefore, mitochondrial biogenesis requires coordination between these two genomes. This coordination is orchestrated by PGC-1α, which activates transcription factors that control the expression of mitochondrial genes encoded by the nucleus [16,46]. For example, PGC-1α activates NRF1 and NRF2 [44,47-49], thus triggering the expression of several proteins: the β-ATP synthase, cytochrome c, cytochrome c oxidase subunits, transcription factor A mitochondrial (TFAM) [44,50], and transcription factor B1 M and B2 M (TFB1M, TFB2M) [51]. Interestingly, NRFs induce TFAM, a transcriptional activator, which translocates to the mitochondrion and plays an essential role in the replication, transcription, and maintenance of mitochondrial DNA [52,53]. By regulating the expression level of TFAM, PGC-1α controls the expression of proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA.

The induction of PGC-1α correlates with physiological situations such as cold, prolonged exercise or fasting (see above). In these circumstances, fatty acids become the preferred energy substrate for the cells. Thus, PGC-1α controls expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation [54] via PPARα [55]. PGC-1α induces expression of the fatty acid transporters CD36 and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), which allow fatty acids to enter into the cell (CD36) and then inside the mitochondria (CPT1), where they are ultimately oxidized. Two transcription factors have been identified as partners of PGC-1α for the regulation of β-oxidation: PPARα [18,41,56] and estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα) [57,58].

In addition to its roles in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation, PGC-1α is also involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Induction of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle activates the expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4), via activation of the MEF2 transcription factor, which increases glucose uptake in these cells [59]. This increase in intracellular glucose concentration is coupled with a decrease in glycolysis and an increase in glycogen storage [60]. Indeed, the induction of PGC-1α leads to the expression of PDK4, via ERRα. This enzyme inhibits glucose oxidation via inhibition of PDH and thus promotes glycogen synthesis [61,62]. Any increase in oxidation via the mitochondrial respiratory chain is associated with the consequent production of ROS. Increased levels of ROS can lead to genotoxic stress and cell death. As a result, cells have developed defense mechanisms against these potentially toxic species. PGC-1α is involved in the regulation of ROS levels by inducing the expression of several enzymes involved in the detoxification of ROS, such as the superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [63,64]. The ability of PGC-1α to induce these antioxidant enzymes are essential for the protection against ROS-induced cell damage and cell death [65].

Why is PGC-1α suspected to play a role cancer biology?

Cancer cells face numerous stresses and environmental conditions and PGC-1α may play a role in their response to this environment. Firstly, nutrient and oxygen supplies fluctuate in tumors and cancer cells must therefore adapt their metabolism, alternatively relying on glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). These variations will modify the energy status of cancer cells and interfere with signaling pathways (AMPK, mTORC1), transcription factors (hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha HIF1α), protein expression (glucose transporter GLUT) that are known to interact with PGC-1α.

Secondly, cancer treatments such as radiation and chemotherapy have been shown to induce oxidative stress in tumors [66,67]. ROS production can either induce cell death or resistance to treatments through mechanisms implicating anti-oxidant enzymes [68]. Oxygen species are mainly produced by the mitochondria. Thus, regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and PGC-1α may interfere with the responses to treatments.

Finally, recent studies have shown that lipids are a source of energy for cancer cells. Adipocytes are important members of the tumor microenvironment as they promote cancer cell aggressiveness through the release of cytokines (adipokines), such as Interleukin 6, to increase the invasive properties of breast cancer cells, or chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7, to promote local dissemination of prostate cancer cells [4,69]. Additionally, adipocytes release fatty acids from lipid droplets, which are oxidized by fatty acid β-oxidation in cancer cells. This metabolic crosstalk between adipocytes and cancer cells promotes aggressiveness and the formation of metastasis [70].

Role of PGC-1α in cancer

PGC-1α in melanoma

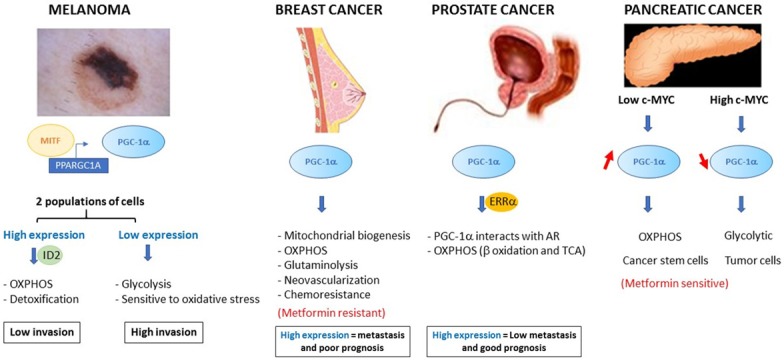

Recent studies have shown that melanoma is comprised of two subpopulations of cells, one expressing high levels of PGC-1α and a second subpopulation with very low PGC-1α expression [71-73]. These two populations have different metabolic and phenotypic profiles (Figure 3). PGC-1α-overexpressing melanoma cells have a very high rate of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and the ability to efficiently detoxify ROS, making them OXPHOS-dependent and resistant to oxidative stress [73,74]. Overexpression of PGC-1α confers a significant proliferative and survival potential, but PGC-1α suppresses the invasive properties of these cells. Luo et al. have shown that PGC-1α suppresses this pro-metastatic program through the inhibitor of DNA binding 2 protein (ID2) and the TCF4 transcription factor [74]. PGC-1α induces the transcription of ID2 that subsequently binds to and inactivates the TCF4 transcription factor, preventing it from binding to the promoters of its target genes. Inactivation of TCF4 leads to reduced expression of genes related to the formation of metastases, including integrins, which are known to promote invasion and metastatic spread. In contrast, melanoma cells expressing low levels of PGC-1α contain few mitochondria, are highly dependent on glycolysis and are highly sensitive to ROS-induced apoptosis [73-75]. However, this subpopulation of cells has a higher expression of the pro-metastatic genes including integrins, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and Wnt. The low expression of PGC-1α results in decreased melanoma cell proliferation and strengthened ability to form metastases. Once implanted at the metastatic site, these cells are able to increase their expression of PGC-1α, which increases growth [73,74]. Expression of PGC-1α in these two subpopulations of melanomas is regulated by the oncogenic transcription factor microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) [73,76,77]. Given the cytoprotective properties of PGC-1α, it is not surprising that it is involved in the response to anticancer treatments. In melanoma, induction of PGC-1α contributes to chemoresistance by increasing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism [76]. In melanoma cells that strongly express PGC-1α, depletion of PGC-1α or inhibition of the respiratory chain increases the efficacy of anti-melanoma chemotherapy by increasing the levels of ROS and apoptosis [73,76,78,79]. In conclusion, PGC-1α plays a dual role in melanoma by influencing both cell survival and metastatic spread.

Figure 3.

PGC-1α and cancer. Schematic summary of the different roles of PGC-1α in melanoma, breast, prostate and pancreatic cancer. The expression of PGC-1α is associated with modifications to cancer cell metabolism, different phenotypes associated with the aggressiveness of the cancer and patient survival.

PGC-1α in breast cancer

In breast cancer, PGC-1α activates nuclear receptors and transcription factors, such as PPARα, ERRα, NRF1 and NRF2, leading to increased mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS and thus generating the large amounts of ATP required for tumor growth. However, although mitochondrial respiration appears to be the main biological function of PGC-1α, additional crucial roles have also been described in other metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, glutaminolysis, regulation of fatty acid oxidation and detoxification [18,80,81]. Indeed, the PGC-1α/ERRα complex modulates the expression of glutamine metabolism enzymes that increase glutamine absorption and thus increase Krebs cycle flux (Figure 3) [82]. In addition, the PGC-1α/ERRα axis co-stimulates expression of genes regulating lipogenesis [82]. Thus, the intermediate metabolites, derived from the catabolism of glutamine, are mainly directed towards the de novo biosynthesis of fatty acids. Overexpression of PGC-1α, and therefore the activation of ERRα, confers growth and proliferation advantages to breast cancer cells, even when nutrients are scarce and/or under conditions of hypoxia. These observations correlate with clinical data showing that overexpression of PGC-1α and its target glutaminolysis genes are associated with poor prognosis for breast cancer patients. In addition to its intrinsic effects on metabolism, PGC-1α is also involved in the regulation of angiogenesis in mammary tumors [83]. It enables neovascularization and thus the increase of available nutrients for mammary tumor cells, which leads to tumor growth. The mechanisms by which PGC-1α induces tumor angiogenesis have not yet been fully elucidated but appear to be regulated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) independently of HIF-1 [83,84]. Tumor cells must switch from a state of rapid proliferation to an invasive phenotype in order to be able to metastasize [85]. The pathways and metabolic requirements that allow tumor cells to switch between proliferation and migration/invasion are still largely unknown. Interestingly, a recent study suggested that PGC-1α may be involved in this mechanism [86]. This study showed that circulating mammary tumor cells express high levels of PGC-1α and exhibit an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis, resulting in the formation of metastases. In addition, the authors have shown that inhibition of PGC-1α in these cells inhibits ATP production, reduces actin cytoskeleton remodeling, decreases intravasation and extravasation, and decreases cell survival [86]. Clinical analyzes also showed that PGC-1α levels are increased in mammary tumors of patients with bone metastases, and revealed a negative correlation between PGC-1α expression and patient survival [82,86]. Although this study does not identify the transcription factor that is targeted by PGC-1α in circulating cancer cells, these results show that PGC-1α is essential for the formation of metastases. The role of PGC-1α in bioenergetic flexibility and thus mammary tumor cell metastasis was confirmed by the study of Andrzejewski et al., which highlights the importance of PGC-1α in resistance to treatments for this type of cancer [87]. Indeed, activation of several metabolic pathways and detoxification of ROS by PGC-1α in breast cancer tissue not only confers proliferative advantages but it also leads to metabolic adaptations that can bypass therapies [88]. For example, the use of ERRα antagonists prevents PGC-1α-mediated metabolic reprogramming and sensitizes mammary tumor cells to therapies [88]. Another study shows that PGC-1α-mediated bioenergetic capabilities help mammary tumor cells to deal with the metabolic disruptor metformin [87]. In contrast, it has been shown that PGC-1α-overexpressing mammary tumor cells become dependent on the folate cycle, which is essential for nucleotide synthesis and tumor proliferation, thus these cells are more vulnerable to antifolates, such as methotrexate [89].

PGC-1α in pancreatic cancer

The c-MYC oncogene causes metabolic reprogramming, which is critical for the proliferation and survival of tumor cells. Recently, it has been shown in pancreatic adenocarcinoma that c-MYC is a direct regulator of PGC-1α [90]. Indeed, c-MYC binds to the promoter of PGC-1α and inhibits its transcription. Consequently, it has been shown that the c-MYC/PGC-1α ratio dictates the metabolic phenotype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells [90]. Pancreatic cancer stem cells (CSC) express high levels of PGC-1α because c-MYC is not expressed and the strong expression of PGC-1α is essential to maintain mitochondrial respiration. Interestingly, overexpression of PGC-1α makes CSCs more sensitive to metformin than differentiated pancreatic tumor cells and they are unable to activate glycolysis in instances of metabolic stress because of the very low expression of c-MYC (Figure 3). In contrast, differentiated pancreatic tumor cells strongly express c-MYC and have low levels of PGC-1α. Resistance often appears during treatment with metformin and an intermediate phenotype emerges in the CSCs, with reduced OXPHOS but increased glycolysis, which is the consequence of the increase in the c-MYC/PGC-1α ratio. Inhibition of c-MYC in this population of CSCs increases their sensitivity to metformin. These results indicate that the balance between c-MYC and PGC-1α determines the metabolic plasticity and metformin sensitivity of pancreatic CSCs [90].

PGC-1α in prostate cancer

The contribution of PGC-1α to prostate cancer has only recently been considered and few studies address this role [91-93]. The role of PGC-1α in prostate cancer (PCa) is similar than of melanoma, i.e., subpopulations with different PGC-1α expression patterns: a sub-population overexpressing PGC-1α that is proliferative but poorly invasive, and a sub-population with low expression of PGC-1α that is very aggressive (Figure 3). Indeed, Shiota et al. show that PGC-1α promotes tumor growth of a subpopulation of androgen-dependent prostatic cancer cells, via activation of the androgen receptor and its target genes [91]. Androgen dependence is a primary characteristic of prostatic tumors and PGC-1α interacts with and activates the androgen receptor (AR) to modify cancer cell metabolism, leading to an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis and glucose and fatty acid oxidation [91]. In androgen-dependent PCa cells the inhibition of PGC-1α induces cell cycle arrest in G1 phase and thus suppresses their growth [91]. Moreover, in these cells, expression of PGC-1α is induced by AMPK in response to androgens [92]. This positive regulation sustains expression of PGC-1α and increases its influence on tumor metabolism [92]. Recently, Torrano et al. identified PGC-1α as a suppressor of tumor progression based on a bioinformatic analysis of several PCa databases [93]. This observation was confirmed in vivo using an androgen-independent prostatic tumor cell line. In fact, injection of cells overexpressing PGC-1α into a mouse model decreased the progression and the formation of PCa metastases. This tumor suppressor effect of PGC-1α is mediated by ERRα and regulation of a catabolic transcriptional program. Indeed, the PGC-1α/ERRα complex increases with β-oxidation and Krebs cycle activity, which weakens the Warburg effect and therefore lowers tumor aggressiveness. In addition, this study shows that, in patients, expression of PGC-1α gradually decreases with each increasing grade of tumor, thus highlighting the prognostic value of PGC-1α in prostate cancer [93].

PGC-1α in other cancers

The role of PGC-1α is emerging in other cancers, including hepatocarcinoma [94], colon cancer [95-97], renal cell carcinoma [98] and ovarian cancer [99]. In most of these studies, overexpression of the co-activator in cell lines derived from these cancers inhibits proliferation and/or its low expression is associated with a poor prognosis. However, paradoxically, chemotherapy has been shown to increase PGC-1α expression in colon cancer and promotes chemoresistance through the activation of sirtuin 1 and oxidative metabolism [100].

Is PGC-1α a potential theragnosis tool?

Depending on the type of cancer, the expression level of PGC-1α has an impact on the prognosis: high levels of expression predict a good outcome for patients with prostate cancer and melanoma, whereas it is bad for breast cancer patients. In pancreatic cancer, PGC-1α is a characteristic of cancer stem cells, which are thought to be at the origin of cancer relapses. Thus, level of expression of PGC-1α may be a valuable biomarker to diagnose the aggressiveness of cancers and, in some cases, the response to treatment. The metabolic status of cancer cells may affect the response to treatments. For example, one can expect that cells relying on oxidative phosphorylation would be more sensitive to drugs that target the mitochondria. This hypothesis was raised by a recent study performed in non-small cell lung cancer showing that metformin does not affect cells that have been depleted of mitochondrial DNA [101]. Mitochondrial metabolism is fundamental for the maintenance of cancer stems cells, and interestingly, several studies have shown that cancer stem cells are very sensitive to metformin, which specifically targets mitochondrial metabolism [102,103]. Furthermore, the status of PGC-1α could also be important given its roles in drug detoxification and the control of antioxidant enzyme expression. Analysis of PGC-1α expression could therefore provide important information concerning patient prognosis and in selecting which treatments to prescribe.

In conclusion, there is much evidence proving that PGC-1α plays a role in cancer. However, it is important to elucidate its role in the initiation of tumorogenesis, the progression of tumors, the formation of metastases and the response to treatments. Depending on the tissue, the tumor stage, the microenvironment and certainly the experimental conditions, tumor cells show significant differences in the expression and the activity of PGC-1α. Unlike oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, mutations, amplifications or deletions of PGC-1α are very rarely detected in tumors. Despite the fact that PGC-1α interacts with a wide variety of transcription factors and is regulated by several signaling pathways, the exact mechanisms that drive the effects of PGC-1α are still poorly known and require further investigations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nathalie Mazure, Stephan Clavel and Nicolas Chevalier for carefully reading the manuscript, and members of the “Targeting prostate cancer cell metabolism” Team for their support. This work was supported by a grant from the Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur le Cancer, l’Association pour la Recherche sur les Tumeurs de la Prostate (ARTP), ITMO-Cancer. It has been supported by the French government, through the UCAJEDI Investments in the Future project managed by the National Research Agency (ANR) with the reference number ANR-15-IDEX-01. L.K. is supported by the French Ministry of Research. F.B. and is a CNRS investigator.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Colosetti P, Auberger P, Tanti JF, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Bost F. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27:3576–3586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirat B, Ader I, Golzio M, Massa F, Mettouchi A, Laurent K, Larbret F, Malavaud B, Cormont M, Lemichez E, Cuvillier O, Tanti JF, Bost F. Inhibition of the GTPase Rac1 mediates the antimigratory effects of metformin in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:586–596. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loubiere C, Clavel S, Gilleron J, Harisseh R, Fauconnier J, Ben-Sahra I, Kaminski L, Laurent K, Herkenne S, Lacas-Gervais S, Ambrosetti D, Alcor D, Rocchi S, Cormont M, Michiels JF, Mari B, Mazure NM, Scorrano L, Lacampagne A, Gharib A, Tanti JF, Bost F. The energy disruptor metformin targets mitochondrial integrity via modification of calcium flux in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5040. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zakikhani M, Dowling R, Fantus IG, Sonenberg N, Pollak M. Metformin is an AMP kinase-dependent growth inhibitor for breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10269–10273. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha JH, Yang WH, Xia W, Wei Y, Chan LC, Lim SO, Li CW, Kim T, Chang SS, Lee HH, Hsu JL, Wang HL, Kuo CW, Chang WC, Hadad S, Purdie CA, McCoy AM, Cai S, Tu Y, Litton JK, Mittendorf EA, Moulder SL, Symmans WF, Thompson AM, Piwnica-Worms H, Chen CH, Khoo KH, Hung MC. Metformin promotes antitumor immunity via endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation of PD-L1. Mol Cell. 2018;71:606–620. e607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah MS, Brownlee M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiovascular disorders in diabetes. Circ Res. 2016;118:1808–1829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besseiche A, Riveline JP, Gautier JF, Breant B, Blondeau B. Metabolic roles of PGC-1alpha and its implications for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kressler D, Schreiber SN, Knutti D, Kralli A. The PGC-1-related protein PERC is a selective coactivator of estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13918–13925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J, Puigserver P, Donovan J, Tarr P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1beta (PGC-1beta), a novel PGC-1-related transcription coactivator associated with host cell factor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1645–1648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson U, Scarpulla RC. Pgc-1-related coactivator, a novel, serum-inducible coactivator of nuclear respiratory factor 1-dependent transcription in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3738–3749. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3738-3749.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ydfors M, Fischer H, Mascher H, Blomstrand E, Norrbom J, Gustafsson T. The truncated splice variants, NT-PGC-1alpha and PGC-1alpha4, increase with both endurance and resistance exercise in human skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep. 2013;1:e00140. doi: 10.1002/phy2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:78–90. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monsalve M, Wu Z, Adelmant G, Puigserver P, Fan M, Spiegelman BM. Direct coupling of transcription and mRNA processing through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Mol Cell. 2000;6:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1868–1876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1868-1876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tcherepanova I, Puigserver P, Norris JD, Spiegelman BM, McDonnell DP. Modulation of estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional activity by the coactivator PGC-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16302–16308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delerive P, Wu Y, Burris TP, Chin WW, Suen CS. PGC-1 functions as a transcriptional coactivator for the retinoid X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3913–3917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knutti D, Kaul A, Kralli A. A tissue-specific coactivator of steroid receptors, identified in a functional genetic screen. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2411–2422. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2411-2422.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akimoto T, Pohnert SC, Li P, Zhang M, Gumbs C, Rosenberg PB, Williams RS, Yan Z. Exercise stimulates Pgc-1alpha transcription in skeletal muscle through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19587–19593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knutti D, Kralli A. PGC-1, a versatile coactivator. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao M, New L, Kravchenko VV, Kato Y, Gram H, di Padova F, Olson EN, Ulevitch RJ, Han J. Regulation of the MEF2 family of transcription factors by p38. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:21–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jørgensen SB, Wojtaszewski JF, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Birk JB, Hellsten Y, Schjerling P, Vaulont S, Neufer PD, Richter EA, Pilegaard H. Effects of alpha-AMPK knockout on exercise-induced gene activation in mouse skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005;19:1146–1148. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3144fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knutti D, Kressler D, Kralli A. Regulation of the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 via MAPK-sensitive interaction with a repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9713–9718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171184698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herzig S, Long F, Jhala US, Hedrick S, Quinn R, Bauer A, Rudolph D, Schutz G, Yoon C, Puigserver P, Spiegelman B, Montminy M. CREB regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis through the coactivator PGC-1. Nature. 2001;413:179–183. doi: 10.1038/35093131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon JC, Puigserver P, Chen G, Donovan J, Wu Z, Rhee J, Adelmant G, Stafford J, Kahn CR, Granner DK, Newgard CB, Spiegelman BM. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature. 2001;413:131–138. doi: 10.1038/35093050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhee J, Inoue Y, Yoon JC, Puigserver P, Fan M, Gonzalez FJ, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of hepatic fasting response by PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1): requirement for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4012–4017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, Walkey CJ, Yoon JC, Oriente F, Kitamura Y, Altomonte J, Dong H, Accili D, Spiegelman BM. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423:550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan M, Rhee J, St-Pierre J, Handschin C, Puigserver P, Lin J, Jäeger S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of mitochondrial respiration through recruitment of p160 myb binding protein to PGC-1alpha: modulation by p38 MAPK. Genes Dev. 2004;18:278–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.1152204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puigserver P, Rhee J, Lin J, Wu Z, Yoon JC, Zhang CY, Krauss S, Mootha VK, Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Cytokine stimulation of energy expenditure through p38 MAP kinase activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1. Mol Cell. 2001;8:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1alpha transcription coactivator. Nature. 2007;447:1012–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jäger S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12017–12022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lustig Y, Ruas JL, Estall JL, Lo JC, Devarakonda S, Laznik D, Choi JH, Ono H, Olsen JV, Spiegelman BM. Separation of the gluconeogenic and mitochondrial functions of PGC-1{alpha} through S6 kinase. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1232–1244. doi: 10.1101/gad.2054711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson BL, Hock MB, Ekholm-Reed S, Wohlschlegel JA, Dev KK, Kralli A, Reed SI. SCFCdc4 acts antagonistically to the PGC-1alpha transcriptional coactivator by targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:252–264. doi: 10.1101/gad.1624208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerhart-Hines Z, Rodgers JT, Bare O, Lerin C, Kim SH, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Wu Z, Puigserver P. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1alpha. EMBO J. 2007;26:1913–1923. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerin C, Rodgers JT, Kalume DE, Kim SH, Pandey A, Puigserver P. GCN5 acetyltransferase complex controls glucose metabolism through transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha. Cell Metab. 2006;3:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teyssier C, Ma H, Emter R, Kralli A, Stallcup MR. Activation of nuclear receptor coactivator PGC-1alpha by arginine methylation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1466–1473. doi: 10.1101/gad.1295005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:847–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell LK, Mansfield CM, Lehman JJ, Kovacs A, Courtois M, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Valencik ML, McDonald JA, Kelly DP. Cardiac-specific induction of the transcriptional coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and reversible cardiomyopathy in a developmental stage-dependent manner. Circ Res. 2004;94:525–533. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117088.36577.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schreiber SN, Emter R, Hock MB, Knutti D, Cardenas J, Podvinec M, Oakeley EJ, Kralli A. The estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) functions in PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6472–6477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308686101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson R, Prolla T. PGC-1alpha in aging and anti-aging interventions. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1790:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly DP, Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev. 2004;18:357–368. doi: 10.1101/gad.1177604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory gene expression in mammalian cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:673–683. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory chain expression by nuclear respiratory factors and PGC-1-related coactivator. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:321–334. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schreiber SN, Knutti D, Brogli K, Uhlmann T, Kralli A. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 regulates the expression and activity of the orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9013–9018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rebelo AP, Dillon LM, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial DNA transcription regulation and nucleoid organization. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:941–951. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:611–638. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clayton DA. Transcription and replication of animal mitochondrial DNAs. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;141:217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parisi MA, Clayton DA. Similarity of human mitochondrial transcription factor 1 to high mobility group proteins. Science. 1991;252:965–969. doi: 10.1126/science.2035027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leone TC, Lehman JJ, Finck BN, Schaeffer PJ, Wende AR, Boudina S, Courtois M, Wozniak DF, Sambandam N, Bernal-Mizrachi C, Chen Z, Holloszy JO, Medeiros DM, Schmidt RE, Saffitz JE, Abel ED, Semenkovich CF, Kelly DP. PGC-1alpha deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobrzyn P, Pyrkowska A, Jazurek M, Szymanski K, Langfort J, Dobrzyn A. Endurance training-induced accumulation of muscle triglycerides is coupled to upregulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;109:1653–1661. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00598.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Napal L, Marrero PF, Haro D. An intronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-binding sequence mediates fatty acid induction of the human carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huss JM, Kopp RP, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) coactivates the cardiac-enriched nuclear receptors estrogen-related receptor-alpha and -gamma. Identification of novel leucine-rich interaction motif within PGC-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40265–40274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huss JM, Torra IP, Staels B, Giguère V, Kelly DP. Estrogen-related receptor alpha directs peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling in the transcriptional control of energy metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9079–9091. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9079-9091.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michael LF, Wu Z, Cheatham RB, Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Lehman JJ, Kelly DP, Spiegelman BM. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3820–3825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061035098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wende AR, Schaeffer PJ, Parker GJ, Zechner C, Han DH, Chen MM, Hancock CR, Lehman JJ, Huss JM, McClain DA, Holloszy JO, Kelly DP. A role for the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha in muscle refueling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36642–36651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Safdar A, Little JP, Stokl AJ, Hettinga BP, Akhtar M, Tarnopolsky MA. Exercise increases mitochondrial PGC-1alpha content and promotes nuclear-mitochondrial cross-talk to coordinate mitochondrial biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10605–10617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.211466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62.Wende AR, Huss JM, Schaeffer PJ, Giguère V, Kelly DP. PGC-1alpha coactivates PDK4 gene expression via the orphan nuclear receptor ERRalpha: a mechanism for transcriptional control of muscle glucose metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10684–10694. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10684-10694.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen SD, Yang DI, Lin TK, Shaw FZ, Liou CW, Chuang YC. Roles of oxidative stress, apoptosis, PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in cerebral ischemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:7199–7215. doi: 10.3390/ijms12107199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valle I, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Arza E, Lamas S, Monsalve M. PGC-1alpha regulates the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jäger S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W, Simon DK, Bachoo R, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leach JK, Van Tuyle G, Lin PS, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Mikkelsen RB. Ionizing radiation-induced, mitochondria-dependent generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3894–3901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conklin KA. Chemotherapy-associated oxidative stress: impact on chemotherapeutic effectiveness. Integr Cancer Ther. 2004;3:294–300. doi: 10.1177/1534735404270335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liou GY, Storz P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:479–496. doi: 10.3109/10715761003667554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laurent V, Guerard A, Mazerolles C, Le Gonidec S, Toulet A, Nieto L, Zaidi F, Majed B, Garandeau D, Socrier Y, Golzio M, Cadoudal T, Chaoui K, Dray C, Monsarrat B, Schiltz O, Wang YY, Couderc B, Valet P, Malavaud B, Muller C. Periprostatic adipocytes act as a driving force for prostate cancer progression in obesity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang YY, Attane C, Milhas D, Dirat B, Dauvillier S, Guerard A, Gilhodes J, Lazar I, Alet N, Laurent V, Le Gonidec S, Biard D, Herve C, Bost F, Ren GS, Bono F, Escourrou G, Prentki M, Nieto L, Valet P, Muller C. Mammary adipocytes stimulate breast cancer invasion through metabolic remodeling of tumor cells. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e87489. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bogunovic D, O’Neill DW, Belitskaya-Levy I, Vacic V, Yu YL, Adams S, Darvishian F, Berman R, Shapiro R, Pavlick AC, Lonardi S, Zavadil J, Osman I, Bhardwaj N. Immune profile and mitotic index of metastatic melanoma lesions enhance clinical staging in predicting patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20429–20434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Riker AI, Enkemann SA, Fodstad O, Liu S, Ren S, Morris C, Xi Y, Howell P, Metge B, Samant RS, Shevde LA, Li W, Eschrich S, Daud A, Ju J, Matta J. The gene expression profiles of primary and metastatic melanoma yields a transition point of tumor progression and metastasis. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vazquez F, Lim JH, Chim H, Bhalla K, Girnun G, Pierce K, Clish CB, Granter SR, Widlund HR, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. PGC1α expression defines a subset of human melanoma tumors with increased mitochondrial capacity and resistance to oxidative stress. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luo C, Lim JH, Lee Y, Granter SR, Thomas A, Vazquez F, Widlund HR, Puigserver P. A PGC1α-mediated transcriptional axis suppresses melanoma metastasis. Nature. 2016;537:422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature19347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, Leitch AM, Johnson TM, DeBerardinis RJ, Morrison SJ. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature. 2015;527:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature15726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haq R, Shoag J, Andreu-Perez P, Yokoyama S, Edelman H, Rowe GC, Frederick DT, Hurley AD, Nellore A, Kung AL, Wargo JA, Song JS, Fisher DE, Arany Z, Widlund HR. Oncogenic BRAF regulates oxidative metabolism via PGC1α and MITF. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ronai Z. The masters talk: the PGC-1α-MITF axis as a melanoma energizer. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12090. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roesch A, Vultur A, Bogeski I, Wang H, Zimmermann KM, Speicher D, Körbel C, Laschke MW, Gimotty PA, Philipp SE, Krause E, Pätzold S, Villanueva J, Krepler C, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Hoth M, Bastian BC, Vogt T, Herlyn M. Overcoming intrinsic multidrug resistance in melanoma by blocking the mitochondrial respiratory chain of slow-cycling JARID1B (high) cells. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:811–825. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang G, Frederick DT, Wu L, Wei Z, Krepler C, Srinivasan S, Chae YC, Xu X, Choi H, Dimwamwa E, Ope O, Shannan B, Basu D, Zhang D, Guha M, Xiao M, Randell S, Sproesser K, Xu W, Liu J, Karakousis GC, Schuchter LM, Gangadhar TC, Amaravadi RK, Gu M, Xu C, Ghosh A, Xu W, Tian T, Zhang J, Zha S, Liu Q, Brafford P, Weeraratna A, Davies MA, Wargo JA, Avadhani NG, Lu Y, Mills GB, Altieri DC, Flaherty KT, Herlyn M. Targeting mitochondrial biogenesis to overcome drug resistance to MAPK inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1834–1856. doi: 10.1172/JCI82661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell. 2007;130:548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters JM, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:181–195. doi: 10.1038/nrc3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McGuirk S, Gravel SP, Deblois G, Papadopoli DJ, Faubert B, Wegner A, Hiller K, Avizonis D, Akavia UD, Jones RG, Giguère V, St-Pierre J. PGC-1α supports glutamine metabolism in breast cancer. Cancer Metab. 2013;1:22. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klimcakova E, Chénard V, McGuirk S, Germain D, Avizonis D, Muller WJ, St-Pierre J. PGC-1α promotes the growth of ErbB2/Neu-induced mammary tumors by regulating nutrient supply. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1538–1546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, Ruas JL, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala SM, Baek KH, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoek KS, Eichhoff OM, Schlegel NC, Döbbeling U, Kobert N, Schaerer L, Hemmi S, Dummer R. In vivo switching of human melanoma cells between proliferative and invasive states. Cancer Res. 2008;68:650–656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.LeBleu VS, O’Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis MC, de Carvalho FM, Damascena A, Domingos Chinen LT, Rocha RM, Asara JM, Kalluri R. PGC-1alpha mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:992–1003. 1001–1015. doi: 10.1038/ncb3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andrzejewski S, Klimcakova E, Johnson RM, Tabaries S, Annis MG, McGuirk S, Northey JJ, Chenard V, Sriram U, Papadopoli DJ, Siegel PM, St-Pierre J. PGC-1alpha promotes breast cancer metastasis and confers bioenergetic flexibility against metabolic drugs. Cell Metab. 2017;26:778–787. e775. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deblois G, Smith HW, Tam IS, Gravel SP, Caron M, Savage P, Labbé DP, Bégin LR, Tremblay ML, Park M, Bourque G, St-Pierre J, Muller WJ, Giguère V. ERRα mediates metabolic adaptations driving lapatinib resistance in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12156. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Audet-Walsh É, Papadopoli DJ, Gravel SP, Yee T, Bridon G, Caron M, Bourque G, Giguère V, St-Pierre J. The PGC-1α/ERRα axis represses one-carbon metabolism and promotes sensitivity to anti-folate therapy in breast cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;14:920–931. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sancho P, Burgos-Ramos E, Tavera A, Bou Kheir T, Jagust P, Schoenhals M, Barneda D, Sellers K, Campos-Olivas R, Grana O, Viera CR, Yuneva M, Sainz B Jr, Heeschen C. MYC/PGC-1alpha balance determines the metabolic phenotype and plasticity of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cell Metab. 2015;22:590–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shiota M, Yokomizo A, Tada Y, Inokuchi J, Tatsugami K, Kuroiwa K, Uchiumi T, Fujimoto N, Seki N, Naito S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha interacts with the androgen receptor (AR) and promotes prostate cancer cell growth by activating the AR. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:114–127. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tennakoon JB, Shi Y, Han JJ, Tsouko E, White MA, Burns AR, Zhang A, Xia X, Ilkayeva OR, Xin L, Ittmann MM, Rick FG, Schally AV, Frigo DE. Androgens regulate prostate cancer cell growth via an AMPK-PGC-1alpha-mediated metabolic switch. Oncogene. 2014;33:5251–5261. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torrano V, Valcarcel-Jimenez L, Cortazar AR, Liu X, Urosevic J, Castillo-Martin M, Fernandez-Ruiz S, Morciano G, Caro-Maldonado A, Guiu M, Zuniga-Garcia P, Graupera M, Bellmunt A, Pandya P, Lorente M, Martin-Martin N, David Sutherland J, Sanchez-Mosquera P, Bozal-Basterra L, Zabala-Letona A, Arruabarrena-Aristorena A, Berenguer A, Embade N, Ugalde-Olano A, Lacasa-Viscasillas I, Loizaga-Iriarte A, Unda-Urzaiz M, Schultz N, Aransay AM, Sanz-Moreno V, Barrio R, Velasco G, Pinton P, Cordon-Cardo C, Locasale JW, Gomis RR, Carracedo A. The metabolic co-regulator PGC1alpha suppresses prostate cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:645–656. doi: 10.1038/ncb3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu R, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Li S, Wang X, Wang C, Liu B, Zen K, Zhang CY, Zhang C, Ba Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha acts as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317695031. doi: 10.1177/1010428317695031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Souza-Teixeira F, Alonso-Molero J, Ayán C, Vilorio-Marques L, Molina AJ, González-Donquiles C, Davila-Batista V, Fernández-Villa T, de Paz JA, Martín V. PGC-1α as a biomarker of physical activity-protective effect on colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2018;11:523–534. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.D’Errico I, Salvatore L, Murzilli S, Lo Sasso G, Latorre D, Martelli N, Egorova AV, Polishuck R, Madeyski-Bengtson K, Lelliott C, Vidal-Puig AJ, Seibel P, Villani G, Moschetta A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1alpha) is a metabolic regulator of intestinal epithelial cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6603–6608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016354108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Triki M, Lapierre M, Cavailles V, Mokdad-Gargouri R. Expression and role of nuclear receptor coregulators in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4480–4490. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i25.4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.LaGory EL, Wu C, Taniguchi CM, Ding CC, Chi JT, von Eyben R, Scott DA, Richardson AD, Giaccia AJ. Suppression of PGC-1α is critical for reprogramming oxidative metabolism in renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2015;12:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang Y, Ba Y, Liu C, Sun G, Ding L, Gao S, Hao J, Yu Z, Zhang J, Zen K, Tong Z, Xiang Y, Zhang CY. PGC-1alpha induces apoptosis in human epithelial ovarian cancer cells through a PPARgamma-dependent pathway. Cell Res. 2007;17:363–373. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vellinga TT, Borovski T, de Boer VC, Fatrai S, van Schelven S, Trumpi K, Verheem A, Snoeren N, Emmink BL, Koster J, Rinkes IH, Kranenburg O. SIRT1/PGC1α-dependent increase in oxidative phosphorylation supports chemotherapy resistance of colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2870–2879. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cruz-Bermudez A, Vicente-Blanco RJ, Laza-Briviesca R, Garcia-Grande A, Laine-Menendez S, Gutierrez L, Calvo V, Romero A, Martin-Acosta P, Garcia JM, Provencio M. PGC-1alpha levels correlate with survival in patients with stage III NSCLC and may define a new biomarker to metabolism-targeted therapy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16661. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Metformin selectively targets cancer stem cells, and acts together with chemotherapy to block tumor growth and prolong remission. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7507–7511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Struhl K. Metformin inhibits the inflammatory response associated with cellular transformation and cancer stem cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:972–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221055110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstrale M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1868–1876. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1868-1876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang YX, Lee CH, Tiep S, Yu RT, Ham J, Kang H, Evans RM. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003;113:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guan HP, Ishizuka T, Chui PC, Lehrke M, Lazar MA. Corepressors selectively control the transcriptional activity of PPARgamma in adipocytes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:453–461. doi: 10.1101/gad.1263305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huss JM, Kelly DP. Nuclear receptor signaling and cardiac energetics. Circ Res. 2004;95:568–578. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141774.29937.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kamei Y, Ohizumi H, Fujitani Y, Nemoto T, Tanaka T, Takahashi N, Kawada T, Miyoshi M, Ezaki O, Kakizuka A. PPARgamma coactivator 1beta/ERR ligand 1 is an ERR protein ligand, whose expression induces a high-energy expenditure and antagonizes obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12378–12383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135217100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mootha VK, Handschin C, Arlow D, Xie X, St Pierre J, Sihag S, Yang W, Altshuler D, Puigserver P, Patterson N, Willy PJ, Schulman IG, Heyman RA, Lander ES, Spiegelman BM. Erralpha and Gabpa/b specify PGC-1alphadependent oxidative phosphorylation gene expression that is altered in diabetic muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6570–6575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401401101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schreiber SN, Emter R, Hock MB, Knutti D, Cardenas J, Podvinec M, Oakeley EJ, Kralli A. The estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) functions in PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6472–6477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308686101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu Y, Delerive P, Chin WW, Burris TP. Requirement of helix 1 and the AF-2 domain of the thyroid hormone receptor for coactivation by PGC-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8898–8905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang Y, Ma K, Song S, Elam MB, Cook GA, Park EA. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha) enhances the thyroid hormone induction of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-I alpha) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53963–53971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Y, Castellani LW, Sinal CJ, Gonzalez FJ, Edwards PA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha) regulates triglyceride metabolism by activation of the nuclear receptor FXR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:157–169. doi: 10.1101/gad.1138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lin J, Yang R, Tarr PT, Wu PH, Handschin C, Li S, Yang W, Pei L, Uldry M, Tontonoz P, Newgard CB, Spiegelman BM. Hyperlipidemic effects of dietary saturated fats mediated through PGC-1beta coactivation of SREBP. Cell. 2005;120:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Oberkofler H, Schraml E, Krempler F, Patsch W. Potentiation of liver X receptor transcriptional activity by peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha. Biochem J. 2003;371:89–96. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mortensen OH, Frandsen L, Schjerling P, Nishimura E, Grunnet N. PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta have both similar and distinct effects on myofiber switching toward an oxidative phenotype. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E807–816. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00591.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bhalla S, Ozalp C, Fang S, Xiang L, Kemper JK. Ligand-activated pregnane X receptor interferes with HNF-4 signaling by targeting a common coactivator PGC-1alpha. Functional implications in hepatic cholesterol and glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45139–45147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kawakami Y, Tsuda M, Takahashi S, Taniguchi N, Esteban CR, Zemmyo M, Furumatsu T, Lotz M, Izpisúa Belmonte JC, Asahara H. Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha regulates chondrogenesis via association with Sox9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2414–2419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]