Summary

Recent advances in generating three-dimensional (3D) organoid systems from stem cells offer new possibilities for disease modeling and drug screening because organoids can recapitulate aspects of in vivo architecture and physiology. In this study, we generate isogenic 3D midbrain organoids with or without a Parkinson's disease-associated LRRK2 G2019S mutation to study the pathogenic mechanisms associated with LRRK2 mutation. We demonstrate that these organoids can recapitulate the 3D pathological hallmarks observed in patients with LRRK2-associated sporadic Parkinson's disease. Importantly, analysis of the protein-protein interaction network in mutant organoids revealed that TXNIP, a thiol-oxidoreductase, is functionally important in the development of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease in a 3D environment. These results provide proof of principle for the utility of 3D organoid-based modeling of sporadic Parkinson's disease in advancing therapeutic discovery.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, iPSC, organoids, disease modeling, midbrain

Highlights

-

•

3D midbrain organoids with environment similar to the aged brain for modeling PD

-

•

LRRK2-G2019S organoids show abnormal phenotypes of LRRK2 sporadic PD

-

•

TXNIP mediates the LRRK2-G2019S pathological phenotypes of PD

H. Kim and colleagues generated 3D midbrain organoids containing a G2019S mutation in LRRK2 and used this system for sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD) modeling in vitro. Their results demonstrate that these 3D midbrain organoids can recapitulate the pathological features of LRRK2-associated sporadic PD. These results demonstrate that the 3D midbrain organoids are invaluable for recapitulating PD phenotypes and understanding the molecular underpinnings of these phenotypes.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the most common neurological disorder associated with movement abnormalities (Fearnley and Lees, 1991). The major pathological characteristic of PD is α-synuclein inclusions, such as Lewy bodies (Spillantini et al., 1997). Missense mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene locus are the most common known causes of late-onset familial and sporadic PD (Di Fonzo et al., 2005, Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2004). Previous studies have suggested that the LRRK2 G2019S gene mutation is associated with α-synuclein accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired dopamine signaling in the human brain, eventually resulting in the progressive loss of dopamine neurons (Daher et al., 2012, Hsieh et al., 2016, Lin et al., 2009, Manzoni and Lewis, 2013). However, a particularly difficult challenge in understanding the role of LRRK2 in PD research has been the generation of models that accurately recapitulate the LRRK2 mutant-associated disease state. For example, animals that harbor genetic mutations mimicking the familial forms of parkinsonism, including LRRK2 mutations, fail to show clear evidence of progressive midbrain dopamine neuron loss or Lewy body formation (Chesselet et al., 2008, Giasson et al., 2002, Lee et al., 2002, Masliah et al., 2000). Another approach that has been taken to model PD is the use of patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) directed to differentiate into dopamine neurons. These models also show variable dopamine neuron toxicity, but other features of PD pathology, such as Lewy body aggregates, are not as prominent as in the human brain (Beal, 2001), and such culture systems are generally immature (Chung et al., 2013). This finding may be due to species-specific differences and/or differences in the architecture of the model systems (two-dimensional [2D] culture versus a three-dimensional [3D] organ).

Recent advances in 3D organoid technology offer promise in advancing the understanding of human development and evaluating therapeutic approaches on a platform more physiologically relevant than traditional immortalized cell lines (Hogberg et al., 2013, Jo et al., 2016, Kelava and Lancaster, 2016). Notably, organoid systems can be used for modeling pathologic phenotypes that more efficiently recapitulate human disease conditions. For example, previous reports showed that Alzheimer's disease phenotypes could be recapitulated in 3D brain organoids (Choi et al., 2014, Raja et al., 2016). Similarly, Miller-Dieker syndrome was modeled in brain organoids, revealing novel molecular mechanisms controlling disease phenotypes in a 3D environment (Bershteyn et al., 2017). Drug discovery has also been advanced in 3D organoid systems; Woo et al. (2016) generated 3D intestinal organoids from dyskeratosis congenita patients and identified Wnt agonists capable of reversing disease phenotypes. These studies demonstrate that the 3D architecture and cellular composition of organoids are invaluable for recapitulating human disease phenotypes and understanding the molecular underpinnings of these phenotypes.

Here, we generate isogenic iPSC-derived midbrain organoids containing a G2019S mutation in LRRK2. First, to develop 3D midbrain organoids with an environment similar to the aged brain for modeling PD, we have devised a modified method for the 3D midbrain organoid production. We utilize this system to study the pathogenic mechanisms of LRRK2-associated sporadic PD. Importantly, we demonstrate that LRRK2-mutant midbrain organoids exhibit pathological signatures observed in LRRK2 PD patients, including increased aggregation of α-synuclein and its aberrant clearance. Moreover, these midbrain organoids showed gene expression profiles that closely mimicked those seen in patients with mutant LRRK2-associated sporadic PD. We identified a 3D key factor, TXNIP, which mediates the LRRK2-G2019S pathological phenotypes in the 3D environment of midbrain organoids. Since TXNIP was previously found to be a risk factor for PD that significantly accelerates the accumulation of α-synuclein (Su et al., 2017), TXNIP dysregulation may aggravate PD pathogenesis in LRRK2-G2019S sporadic PD in a 3D environment. Our results indicate that midbrain 3D organoids more accurately recapitulate LRRK2-based sporadic PD than 2D culture systems, and thus these models offer great potential not only for understanding the molecular drivers of pathogenesis but also for screening targeted therapies for patients with LRRK2-associated PD.

Results

Generation of Midbrain Organoids from hiPSCs

To generate midbrain organoids with an environment similar to the aged brain, we have devised a modified method for the midbrain organoid production from previously described self-organizing principle from human iPSC (hiPSC) culture (Jo et al., 2016). First, hiPSCs were dissociated into embryoid bodies (EBs) and organized to form a 3D structure using Matrigel. To promote neuroectodermal differentiation, we treated these EBs with a GSK-3 inhibitor (CHIR99021) and bone morphogenetic protein/transforming growth factor β inhibitors (Noggin and SB431542). The addition of fibroblast growth factor 8 and sonic hedgehog (SHH) prompts patterning toward a mesencephalic fate in a 3D culture condition (Arenas, 2014, Kirkeby et al., 2012) (Figures 1A and S1A). For the terminal differentiation of 3D midbrain organoids, 3D cultures were treated with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and ascorbic acid in the neuronal differentiation medium by 45 days. Finally, to develop midbrain organoids that share numerous features with the aged human midbrain, we maintained 3D midbrain organoid in the BDNF and GDNF without antioxidant for up to 60 days.

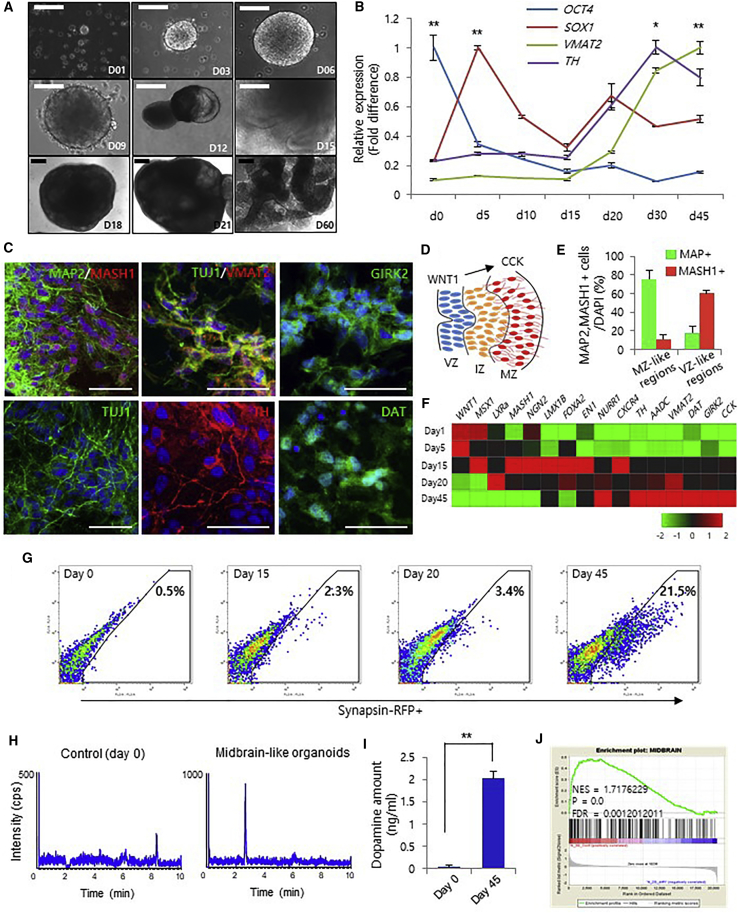

Figure 1.

Generation of Midbrain 3D Organoids from hiPSCs

(A) Bright-field microscopy images of the stages of 3D organoid generation for 2 months. Scale bars, 200 μm.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of a pluripotency marker (OCT4), a neural progenitor marker (SOX1), and dopaminergic neuronal markers (TH and VMAT2) at different time points. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

(C) Immunofluorescence for MAP2, MASH1, TUJ1, VMAT2, TH, DAT, and GIRK2 to confirm the presence of midbrain dopaminergic neurons on day 60. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(D) Schematic image of midbrain development. The marginal zone (MZ) contains midbrain dopaminergic neurons that differentiate from radial glia cells in the ventricular zone (VZ).

(E) Percentage of MAP2/MASH1-positive cells in the MZ- and VZ-like zones at day 60.

(F) Gene expression profiling using qRT-PCR from 1 to 45 days. Red and green represent higher and lower gene expression levels, respectively; n = 3 per sample.

(G) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of synapsin-RFP-positive cells from midbrain 3D organoids.

(H and I) KCL-induced dopamine levels in midbrain 3D organoids using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

(J) Gene set enrichment analysis of the microarray data from midbrain 3D organoids compared with that of 2D cultures.

We confirmed that the mRNA expression of the neuroectodermal marker SOX1 was significantly increased at day 5 in EBs (Figure 1B). In contrast, the expression of the pluripotency marker OCT4 was markedly decreased immediately after the generation of organoids (Figure 1B). At the beginning of further differentiation to the midbrain-like phase under 3D conditions from day 15, the expression of the dopaminergic neuronal markers VMAT2 and TH increased rapidly (Figure 1B). Consistently, the expression of the midbrain markers NURR1 and DAT was detected in 6- and 8-week-old midbrain organoids, respectively (Figure S1B). To confirm the generation of post-mitotic dopaminergic neurons in midbrain organoids at day 60, we analyzed dopaminergic neurons expressing the mature neuronal markers TH, VMAT2, GIRK2, and DAT by immunostaining (Figures 1C and S1C). Additionally, we observed significant increases in the expression of dopamine neuron markers PITX3 and AADC from day 30 (Figures S1D and S1E). Moreover, we found that most MASH1-positive cells, as the midbrain progenitors, remained in the ventricular zone, through which radial glia cells pass as they migrate to the marginal zone, where they mature into MAP2-positive cells (Figures 1C–1E).

We also observed robust expression of additional midbrain markers in midbrain organoids, suggesting that the organoids from day 45 most closely resemble the mature dopaminergic midbrain (Figure 1F). In addition, to evaluate the efficiency of dopamine neuron generation in 3D organoids, we prepared organoids derived from iPSCs harboring a synapsin1-red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter. Flow-cytometric analysis showed an increase in RFP-positive cells from 2.3% at day 15 to 21.5% at day 45, indicating that 3D culture efficiently induces generation of dopamine neurons in midbrain organoids (Figure 1G). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of dopamine release showed that dopamine levels were significantly increased in midbrain-like organoids at day 45 (Figures 1H and 1I). Moreover, we confirmed that the differentially expressed genes in the midbrain organoid at 45 days were highly enriched in the gene database derived from primary human midbrain (Figure 1J).

In addition, to further characterize our organoids recapitulate 3D architecture found in the human brain, we examined the expression of neuromelanins, which are known to be insoluble granular pigments that accumulate in the A9 midbrain in human and primate, in the midbrain organoids (Sulzer et al., 2000). Consistent with previous results, we found a significant amount of neuromelanin in the organoids at 60 days (Figures S1F and S1G). Moreover, genes such as ANLN, GLA35ST1, FAH, MBP, ACSL1, and CLDN11, which are highly expressed in aged human midbrains (Soreq et al., 2017), were highly expressed in the midbrain organoids at 60 days (Figure S1H). Consistently, genes that were differentially expressed between 3D cultures in 60-day organoids were highly enriched for genes also differentially expressed in aged human midbrains (Figure S1I). Furthermore, phosphorylation of histone H2AX, a marker of DNA damage associated with aging (Barral et al., 2014, Sedelnikova et al., 2004), was significantly increased in midbrain organoids at day 60 (Figures S1J–S1M). These data indicate that midbrain organoids at 60 days share numerous features with the aged human midbrain.

Additionally, we compared midbrain-like 3D organoids with 2D cultures. The 3D organoids 45 days after differentiation exhibited a significant increase the percentage of MAP2+ and TH+ cells with organizing regional structure (Figures S1N and S1O). Furthermore, the expression of the neuronal marker genes AADC, CHAT, and MAPT and the astrocyte marker genes GFAP, S100B, and ALDH1L1 was significantly increased in midbrain 3D organoids relative to the 2D culture conditions (Figure S1P). Gene ontology analysis of biological processes in 3D organoids showed enrichment for neuron development, neuron differentiation, and cell development relative to the 2D cultures, suggesting that 3D midbrain organoids more efficiently undergo neuronal differentiation and maturation (Figures S1Q and S1R). Similarly, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that genes upregulated in 3D organoids relative to 2D culture were enriched in aged human midbrain (Figures 1J and S1S).

Next, for PD modeling we generated isogenic hiPSCs using the CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease system to introduce the heterozygous LRRK2-G2019S point mutation into hiPSCs. We designed a guide RNA target site 4 bp away from the G2019S mutation site on exon 41 of the human LRRK2 gene locus (Figure S2A). Surveyor nuclease assays and Sanger sequencing analyses of targeted cells demonstrated that LRRK2−/− cells harbored deletions of 3–26 bp (Figures S2B and S2C). The donor plasmid containing the G2019S mutation was cotransfected with the guide RNA/Cas9 vector, then puromycin- and CRE-selected cells were identified by a PCR-based assay (Figures S2D–S2F). We further confirmed the generation of heterozygote LRRK2-G2019S mutant hiPSCs by Sanger sequencing analyses (data not shown). Additionally, we prepared two more independently targeted isogenic iPSC lines and further evaluated pathological phenotypes in these iPSC-derived organoids (Figures S2G–S2J). Control and heterozygote LRRK2-G2019S mutant hiPSCs expressed endogenous pluripotency genes, such as TRA1–60, SOX2, OCT4, NANOG, and SSEA1, and showed no differences in pluripotency and self-renewal assays (Figures S2G–S2J).

We then generated midbrain organoids using LRRK2-G2019S mutant hiPSCs (Figures S2K–S2N). The neuronal identity of the LRRK2-G2019S organoids was confirmed by immunohistochemistry of the neuronal markers TUJ1, MAP2, NURR1, and DAT (Figure 2A). The expression of the dopaminergic neuronal markers TH, AADC, VMAT2, and DAT was markedly decreased in LRRK2-G2019S organoids relative to controls at day 60 (Figures 2B and S2O). Mature neuronal genes such as NURR1, PITX3, EN1, TH, and MAPT were decreased in LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids but not in 2D cultures (where their expression was very low regardless of genotype) (Figure S3A). Remarkably, the dopaminergic neurons in LRRK2-G2019S organoids exhibited decreased neurite length, indicating that the organoid model system better recapitulated disease pathology (Figure S3B).

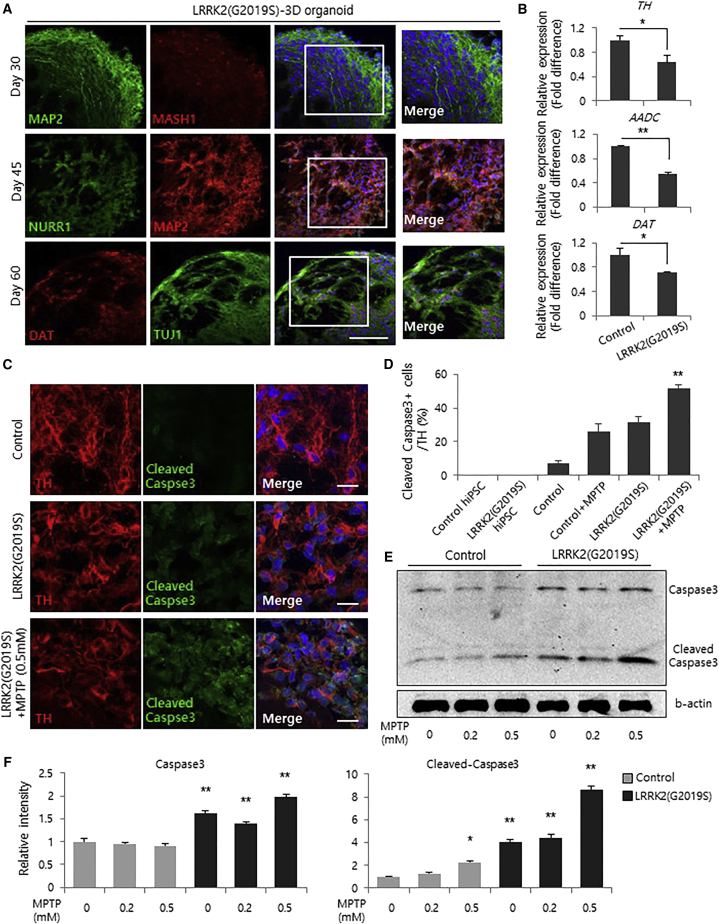

Figure 2.

Generation of Midbrain 3D Organoids from LRRK2-G2019S hiPSCs

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of midbrain 3D organoids from LRRK2-G2019S hiPSCs. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of midbrain 3D organoids and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids regarding dopaminergic neuronal markers TH, AADC, and DAT at 60 days. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(C) Immunostaining of TH-positive and cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in midbrain 3D organoids and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids. Scale bars, 20 μm.

(D) Percentage of cleaved caspase-3/TH-positive cells in midbrain 3D organoids and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids treated with 0.5 mM MPTP. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(E and F) Western blot analysis (E) and quantification (F) show an increase in cleaved caspase-3 levels after treatment with MPTP. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

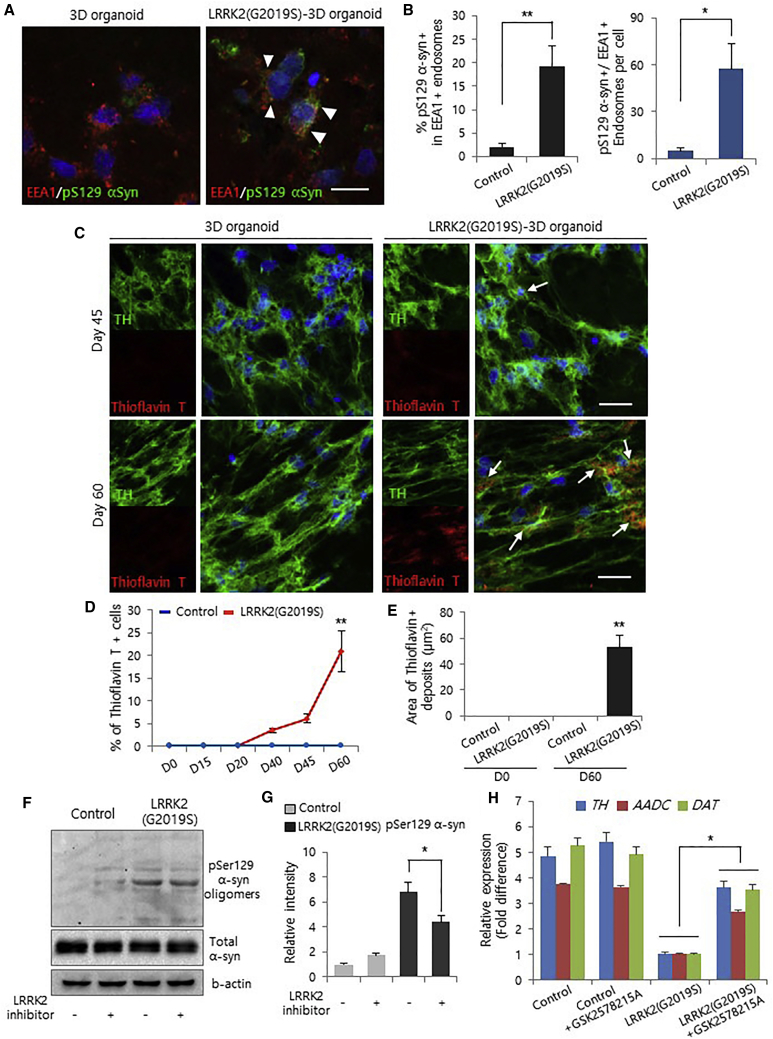

We next examined the susceptibility of LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced neurotoxic damage. We confirmed a significant increase in cleaved caspase-3+ apoptotic dopamine neurons in LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids treated with all concentrations of MPTP (Figures 2C–2F). Consistently, we confirmed increased cell death in LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids (Figure S3C). Additionally, to assess the effect of the LRRK2-G2019S mutation in PD-associated pathogenesis, we examined whether LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids exhibit abnormal localization of α-synuclein phosphorylated at serine 129 (pS129) in vesicular endosomal compartments. We observed localization of pS129-α-synuclein-positive vesicles with endosomes positive for an early endosome marker, EEA1, in LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids (Figures 3A and S3D). The LRRK2-G2019S mutation effectively increased the population of pS129-α-synuclein and EEA1 double-positive endosomes (Figures 3B and S3E). Furthermore, abnormal localization of pS129 α-synuclein vesicles and mitophagy with autophagy marker, LC3B, was increased in LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids (Figures S3F and S3G). Remarkably, thioflavin T-positive deposits in the 3D organoids at day 60 were significantly increased by the LRRK2-G2019S mutation (Figures 3C–3E and S3H), suggesting that pS129-α-synuclein is aberrantly localized in the aged LRRK2-G2019S organoids. To further demonstrate that this 3D model system can be used for testing therapeutic strategies against PD, we assessed the effects of pharmacological inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity. Previously, it has been reported that LRRK2 kinase inhibitors did not affect the phosphorylation of pS129-α-synuclein (Henderson et al., 2018), whereas other groups reported that inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity reduced inclusions of pS129-α-synuclein in G2019S-LRRK2-expressing neurons (Schapansky et al., 2018, Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2016). Thus, to examine whether inhibition of G2019S-LRRK2 can reduce the pS129-α-synuclein inclusions in LRRK2-G2019S-midbrain organoids, we treated the mutant organoids with LRRK2 kinase inhibitor, GSK2578215A. Consistent with previous results, the treatment with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor substantially reduced the accumulation of phosphorylated α-synuclein (Figures 3F, 3G, and S3I). Moreover, the expression of the dopaminergic neuron maker genes TH, AADC, and DAT was partially restored in each LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoid treated with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor (Figures 3H and S3J). Previously, G2019S mutation in LRRK2 led to disinhibited kinase activity, which eventually resulted in the accumulation of tau-positive inclusions and apoptosis (Guerreiro et al., 2016, MacLeod et al., 2006), whereas suppression of LRRK2 with kinase inhibitors can lead to an opposite phenotype of increased neurite process and complexity, and eventual survival of dopamine neurons (Daher et al., 2015). Consistent with this result, we found decreased dopamine neuronal cell death by LRRK2 inhibitor, which resulted in increased TH, AADC, and DAT in the mutant LRRK2 organoids (Figures S3J and S3K). Therefore, this 3D organoid model system is amenable to testing therapeutic strategies against PD.

Figure 3.

Pathological Analyses of LRRK2-G2019S Knockin 3D Organoids

(A) Representative images showing colocalization analysis of EEA1-positive endosomes with pS129-α-synuclein-positive puncta in wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(B) Percentage of pS129-α-synuclein-positive and EEA1-positive puncta among all EEA1-positive puncta (left). Number of pS129-α-synuclein/EEA1-positive endosomes per cell in LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids (right). Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 10 per sample).

(C) Thioflavin T (50 μM) staining of wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids. The arrow indicates α-synuclein deposits. Scale bars, 20 μm.

(D) Percentage of thioflavin T-positive cells among all TH-positive cells in the wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(E) Quantification of the mean area of thioflavin T-positive deposits in midbrain 3D organoids at 60 days. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 5 per sample).

(F and G) (F) Treatment with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor (GSK2578215A, 1 μM) significantly reduces phosphorylated α-synuclein oligomer levels in LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids. (G) Intensity of pS129-α-synuclein in LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids treated with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(H) Real-time qPCR analysis of dopaminergic neuron markers (TH, AADC, and DAT) in wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids treated with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor GSK2578215A. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

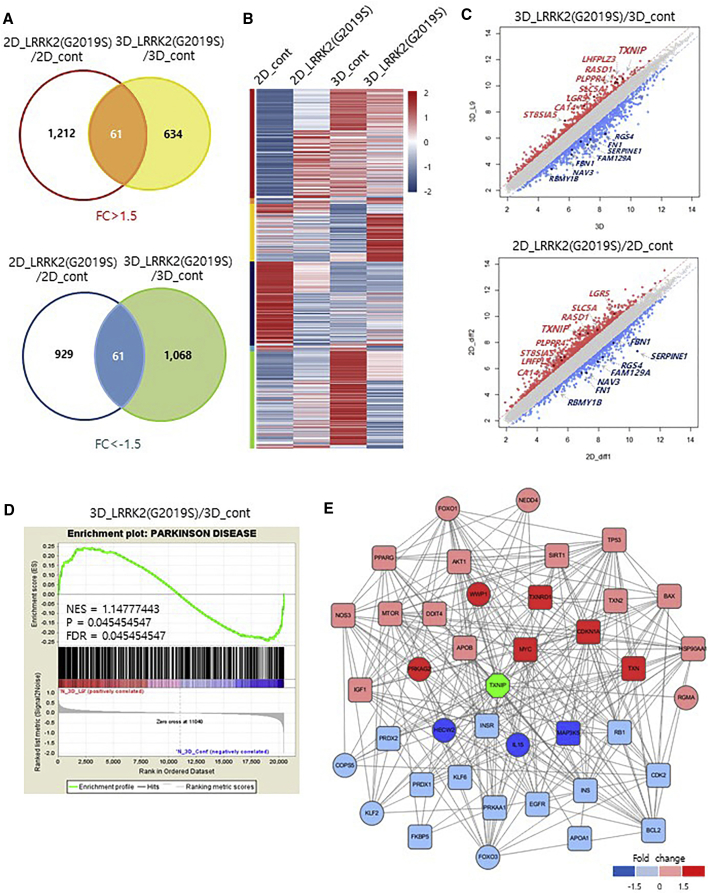

Next, to gain insight into the molecular mechanism of LRRK2-G2019S-associated PD pathologies in midbrain organoids, we compared global transcriptome profiles of control and LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids. Midbrain 3D organoids expressing LRRK2-G2019S showed dynamic changes in global gene expression (Figures 4A and S4A). Differentially expressed genes in the presence of the LRRK2-G2019S mutation were significantly different in 3D organoids relative to 2D culture (Figures 4A and 4B). Additionally, we found that the differentially expressed genes overlapped between LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids and LRRK2-G2019S 2D cultures, indicating that these are specific genes affected by the LRRK2-G2019S mutation (Figure 4C). Notably, one of the top differentially expressed genes in LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids was thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), which was previously reported to be associated with lysosomal dysfunction in α-synuclein-overexpressed cultures (Su et al., 2017).

Figure 4.

Global Gene Expression Analyses of LRRK2-G2019S Knockin 3D Organoids and Midbrain 3D Organoids

(A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes between LRRK2-G2019S knockin 2D cultures compared with wild-type 2D cultures and LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids compared with wild-type 3D organoids. Number of genes up- or downregulated by 1.5-fold are presented in the Venn diagram.

(B) Differentially expressed genes in control and LRRK2-G2019S under 2D or 3D culture conditions. Heatmap and density color code of the 3,965 genes showing differential expression in the microarray analysis under wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S. One sample from each condition was prepared.

(C) Scatterplots of the microarray data for LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids compared with wild-type 3D organoids (top) and LRRK2-G2019S knockin 2D cultures compared with wild-type 2D cultures (bottom).

(D) Gene set enrichment analysis of the microarray expression data from LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoid compared with wild-type 3D organoids.

(E) Graph of the TXNIP protein interaction network related to PD risk factors. Red color indicates high expression and blue color represents low expression. Rectangular-shaped nodes represent proteins that have PD genetic risk factors.

To examine the extent to which LRRK2-G2019S mutant PD organoids molecularly resemble sporadic PD tissue, we next compared the differential gene patterns between LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids and sporadic PD patient-derived brain tissue (MeSH:D010300). Importantly, GSEA revealed that the differentially expressed gene set in LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids relative to LRRK2-G2019S 2D cultures was enriched in genes isolated from sporadic PD patient brain tissue (Figures 4D and S4B), demonstrating the suitability of using our human LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids to study the molecular pathology of LRRK2-G2019S-associated sporadic PD. The protein-protein interaction HTRldb database from the differentially expressed genes in LRRK2-G2019S mutant organoids was further analyzed to construct coexpression networks. Interestingly, the TXNIP protein interaction network was defined as the major subnetwork containing PD genetic risk factors (Figures 4E and S4C).

We further analyzed TXNIP mRNA levels in wild-type 3D organoids and LRRK2-G2019S-derived 3D organoids (Figure 5A). At the basal level, we found a considerable increase in TXNIP mRNA caused by the LRRK2-G2019S mutation in 3D organoids relative to 2D culture (Figures 5B and 5C). To further investigate the molecular mechanisms of increased expression of TXNIP by LRRK2-G2019S mutation, we initially assessed the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, which can be modulated by oxidative stress in the development of neurodegeneration (Chen et al., 2012, Hsu et al., 2010). Interestingly, we found that phosphorylation of ERK and p38 was increased upon LRRK2-G2019S mutation of 3D midbrain organoids (Figures S4D and S4E). Previously, the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases was known to activate NRF2, which led to negative regulation of TXNIP expression (Gunjima et al., 2014, Hou et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2017). Consistent with this result, we found that translocation of the activated NRF2 proteins was decreased upon LRRK2-G2019S mutation in the midbrain organoids (Figure S4F). Moreover, NRF2 binding to the TXNIP promoter region was decreased in the LRRK2-G2019S mutation organoids (Figure S4F), eventually suggesting increased expression levels of TXNIP via the decreased translocation of NRF2 in G2019S LRRK2 3D organoid models (Figure S4G). Moreover, we confirmed that increased TXNIP expression inhibits the activity of thioredoxin-1 in G2019S-LRRK2 organoids (Figures S4H–S4J).

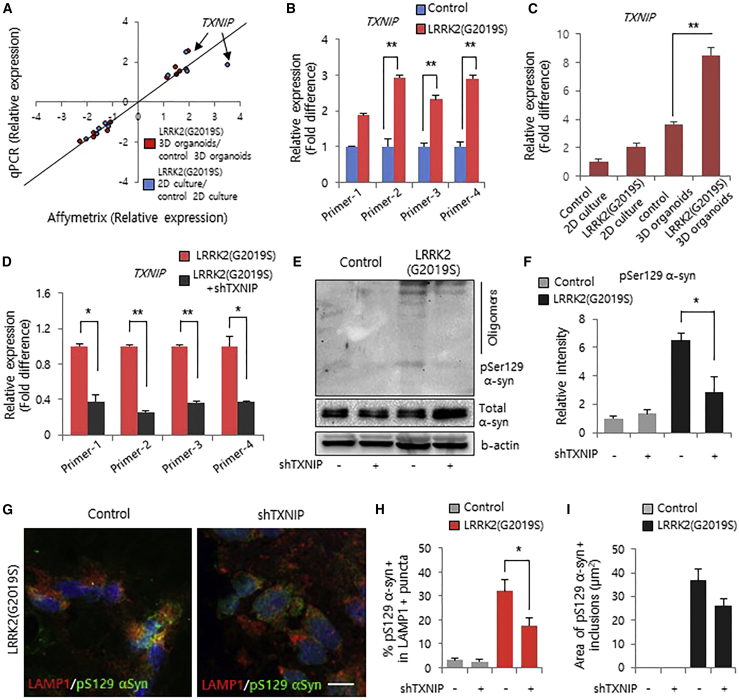

Figure 5.

Knockdown of TXNIP Rescues α-Synuclein Oligomers in LRRK2-G2019S Knockin 3D Organoids

(A) Validation of microarray and real-time qPCR gene expression data.

(B) Real-time qPCR analysis of TXNIP expression in LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids and midbrain 3D organoids. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(C) Real-time qPCR analysis of TXNIP expression in control and LRRK2-G2019S 3D organoids compared with control and LRRK2-G2019S 2D cultures. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(D) Validation of TXNIP gene expression in LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids treated with TXNIP-short hairpin RNA (TXNIP-shRNA) (target sequence: agt gga ggt gtg tga agt tac tcg tgt ca, i026466a) via real-time qPCR. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(E and F) Western blot analysis (E) and quantification (F) of pS129-α-synuclein reveals a reduction in pS129-α-synuclein oligomers in LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids treated with TXNIP-shRNA. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 by ANOVA (n = 3 per sample).

(G) Representative immunofluorescence images of LAMP1 and pS129-α-synuclein puncta in LRRK2-G2019S knockin 3D organoids. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(H and I) Quantification (H) of LAMP1+ and pS129-α-synuclein+ puncta showing a reduction (I) of pS129-α-synuclein inclusions upon treatment with TXNIP-shRNA. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 by ANOVA (n = 5 per sample).

To analyze whether TXNIP functionally contributes to LRRK2-G2019S mutant-derived PD phenotypes, we examined α-synuclein aggregation in LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids upon TXNIP knockdown (Figures S5A–S5C). Interestingly, analysis of pS129-α-synuclein by western blot showed a significant decrease in α-synuclein aggregation in LRRK2-G2019S mutant 3D organoids relative to wild-type 3D organoids upon TXNIP inhibition (Figures 5D–5F and S5D). Additionally, we investigated the lysosomal effect of LRRK2-G2019S-associated PD; TXNIP knockdown suppressed the aggregation of phosphorylated α-synuclein with LAMP1 (lysosomal marker)-positive puncta (Figures 5G and 5H). Consistent with these data, the area of pS129-α-synuclein inclusions was significantly decreased upon TXNIP knockdown (Figures 5I and S5E). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that human TXNIP is functionally connected to the LRRK2-G2019S mutation in a 3D environment and may aggravate LRRK2-G2019S-associated sporadic PD in a 3D environment relative to 2D culture.

Discussion

PD is characterized by the degeneration of midbrain dopamine neurons, ultimately leading to progressive movement disorder in patients. The development of faithful PD model systems is essential for understanding the molecular pathogenesis and identifying novel therapeutic targets for PD. However, to date none of the existing models truly recapitulates the PD pathology and symptoms observed in humans. The aim of our study was to generate a more accurate 3D model of human PD to gain a deeper understanding of PD pathogenesis in a 3D environment and to enable the future development of a high-throughput drug-screening system.

In this study, we generated human 3D midbrain organoids that specifically express human G2019S mutant LRRK2 and used this model to test fundamental hypotheses about the pathogenesis associated with LRRK2-based late-onset PD. Additionally, we established a screening system for identifying target genes that could mediate LRRK2 toxicity in a 3D environment. Previous studies have shown that 3D organoid technology provides great opportunities to explore disease pathogenesis in various organs, including the intestine, kidney, retina, and brain (Czerniecki et al., 2018, Takasato et al., 2015, Volkner et al., 2016, Woo et al., 2016). Consistent with these results, we have demonstrated that LRRK2 mutant organoids can more accurately recapitulate the LRRK2 mutant-associated disease state.

Notably, we generated isogenic LRRK2-G2019S-expressing midbrain organoids from hiPSCs. This system can overcome the differences in genetic background among cell lines inherent to working with genetically diverse human samples. The comparative results of a pair of isogenic organoids that differ solely at the LRRK2 locus can be used to more accurately study LRRK2-induced PD in a human model system. Importantly, we identified that these isogenic mutant LRRK2 organoids recapitulated several abnormal PD phenotypes compared with control organoids, demonstrating that these PD pathologies can be reproduced in LRRK2 midbrain organoids. These results are particularly intriguing because none of the LRRK2 animal and 2D human cell-culture models recapitulate the PD pathology observed in the human midbrain (Byers et al., 2012). It was previously shown that familial Alzheimer cerebral organoids can recapitulate some phenotypes of Alzheimer's disease (Raja et al., 2016). Thus, combined with this previous result, we demonstrated that these isogenic 3D organoids can be faithfully used as alternative models of neurological disease for studying pathologies and drug screening.

We identified a gene, TXNIP, which was specifically upregulated in a 3D environment of LRRK2-G2019S midbrain organoids. Analysis of the differentially expressed genes from LRRK2-G2019S midbrain organoids revealed that TXNIP was specifically upregulated in mutant organoids, and we further demonstrated that increased expression of TXNIP was specific for mutant 3D organoid conditions. Moreover, inhibition of TXNIP suppresses LRRK2-induced phenotypes in 3D organoids, and thus TXNIP might contribute to the disease phenotypes of patients with LRRK2-associated sporadic PD. While it has been reported that TXNIP is associated with α-synuclein-induced PD (Su et al., 2017), the functional association between LRRK2 and TXNIP is not known. Thus, our data provide a direct functional connection between α-synuclein and LRRK2 through TXNIP in the context of pathogenic conditions only captured by 3D organoid cultures. The identification of functional connections between PD-linked genes in a 3D environment provides important insight into the pathophysiology of PD development.

Experimental Procedures

Human iPSC Culture and Characterization

Human control fibroblast was purchased from the Coriell Cell Repository. Human fibroblasts (GM23967, male, 52 years old) were cultured in human cell-culture medium containing DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). To generate hiPSCs from fibroblasts, we infected cells at passage 6 with a lentivirus construct harboring Oct4, Sox2, C-myc, and Klf4 twice in 2 days. The hiPSC line was cultured in human embryonic stem cell growth medium (CEFO, Seoul, South Korea) on Matrigel at 37°C and 5% CO2. For the transduction of donor and CRISPR/Cas9 vectors, we treated hiPSCs with Accutase (A6964, Sigma) and transfected them using the Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (Bio-Rad). These cells were seeded on Matrigel-coated plates, and human embryonic stem cell growth medium was changed every day. The hiPSCs were immunostained using primary antibodies against OCT4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-5279), SOX2 (R&D Systems, MAB2018), NANOG (Bethyl Laboratories, A300-397a), SSEA1 (Santa Cruz, sc-21702), and TRA 1–60 (Millipore, MAB4360), and appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (Invitrogen).

Midbrain 3D Organoid Culture

The hiPSCs were treated with Accutase to induce dissociation into single cells, and EBs were maintained in human embryonic stem cell growth medium without a ROCK inhibitor for 3 days. To generate 3D organoids, we embedded EBs in a Matrigel matrix (Corning) containing 60% laminin, 30% collagen IV, and 8% entactin to contribute to structural organization. EBs embedded in Matrigel were maintained in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Human embryonic stem cell growth medium was replaced with neural stem cell medium (Advanced DMEM/F12 and neurobasal medium, 1× N2, 1× B27, 5% Albumax-I, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 3 μM CHIR99021, 0.5 μM A83-01, and 10 ng/mL leukemia inhibitory factor). Additionally, for neural induction, fibroblast growth factor 2 (20 ng/mL) and epidermal growth factor (20 ng/mL) were included in the neural stem cell medium. To promote midbrain patterning and maturation, we cultured aggregated cells in neural stem cell medium containing 200 nM ascorbic acid, 20 ng/mL BDNF, 100 ng/mL SHH, and 20 ng/mL GDNF. Culture medium was changed every 3 days, and organoids were maintained on an orbital shaker (PSU-10i, Biosan) in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Flow Cytometry

Midbrain 3D organoids were dissociated using a homogenizer and treated with 0.125% trypsin-EDTA for 5 min. Single cells were resuspended in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed twice with 1% BSA and filtered to remove aggregated cells. After filtering, the cells were resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer. Flow cytometry was performed using Accuri equipment (Becton-Dickinson), and data analysis was conducted by FlowJo vX software (TreeStar).

Immunofluorescence Staining Analysis

Organoids were washed with 1× PBS before being fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution overnight. Frozen organoids were sectioned at 15–20 μm using a Thermo Shandon cryotome and collected on glass microscope slides. Sections were immunostained according to standard protocols using the following primary antibodies: OTX2 (Abcam, AB21990), FOXA2 (Abcam, AB108422), NGN2 (Millipore, AB5682), MASH1 (BD Biosciences, 556604), TUJ1 (Sigma, T2200), MAP2 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 4542s), TH (Pel-Freez Biologicals, P60101-150), VMAT2 (Abcam, AB1598P), DAT (Millipore, MAB369), PITX3 (Invitrogen, 382850), AADC (Abcam, AB211535), NURR1 (Santa Cruz, sc-991), GIRK2 (Abcam, AB65096), cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, 9661s), pS129-α-synuclein (Abcam, AB9850), LAMP1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), γH2AX (Cell Signaling, 9718s), LC3B (Cell Signaling, 3868s), PARKIN (Millipore, MAB5512), NRF2 (Cell Signaling, 12721s), and EEA1 (Millipore, 07-1820). Appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen. Next, sections were treated with 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) and mounted in Fluoromount-G mounting medium. Representative images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope and a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, LSM800).

Western Blot Analysis

Organoids were dissociated by a homogenizer and washed with 1× PBS. Homogenized organoids were extracted in lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mmol/L NaCl in 50 mmol/L Tris [pH 8.0], Sigma-Aldrich; and 1× proteinase inhibitor mixture, Roche). The extracted protein was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was probed with the following primary antibodies: NURR1 (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-991), VMAT2 (1:1,000, Abcam, AB1598P), PITX3 (1:1,000, Invitrogen, 382850), pS129-α-synuclein (1:500, Abcam, AB9850), cleaved caspase-3 (1:500, Cell Signaling, 9661s), TXNIP (1:500, Thermo, 40-3700), Phospho-ERK1/2 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 4370s), ERK1/2 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 4695s), Phospho-p38 (1:500, Thermo, MA5-15177), p38 (1:500, Antibodies online, abin2957701), and β-actin (1:1,000, AbFrontier, LF-PA0207). Representative images are shown of western blots performed using Chemidoc TRS+ with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from organoid samples using an RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen), then cDNA was synthesized using AccuPower RT-PCR PreMix (Bioneer). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mixes (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR analysis was conducted in a Rotor-Gene Q real-time PCR cycler (Qiagen) after 1/50 dilution of the reverse transcription reaction. Gene expression of all target genes was normalized against the expression level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in each sample. Human TXNIP primers were used as follows: primer-1 forward 5′-AGT GTA ACA GCA AGC CTA ATG-3′, reverse 5′-GTC AAG AAA AGC CTT CAC CC-3′; primer-2 forward 5′-CGA ATT GTG GTC CCC AAA C-3′, reverse 5′-TTG CAG CCC AGG ATA GAA G-3′; primer-3 forward 5′-AGA AGT TGT CAT CAG TCA GAG G-3′, reverse 5′-ATT ACC AGG GGC AGG TCA AG-3′; primer-4 forward 5′-AAG CAG CAG AAC ATC CAG C-3′, reverse 5′-AGG GGC ATA CAT AAA GAT AGG G-3.

Gene Expression Profiling Using Microarray

Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST Array was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. The robust multiarray averaging method using the affy R package was used for normalization and summarization. The comparative analysis between test sample and control sample was carried out using local-pooled-error test and fold change in which the null hypothesis was that no difference exists among two groups. False discovery rate (FDR) was controlled by adjusting the p value using the Benjamini-Hochberg algorithm. Heatmap and density color code of the 3,965 genes showed differential expression in the microarray analysis under wild-type and LRRK2-G2019S. One sample from each condition was prepared.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

GSEA was performed using the GSEA pre-ranked mode to identify the statistical enrichment on the gene sets of the PD genes in both 2D_LRRK2 versus 2D_control and 3D_LRRK2 versus 3D_control in microarray.

Curated gene sets (5,171 genes of PD) in Gene-Disease Associations dataset of the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in 2D_LRRK2/2D_control, 3D_LRRK2/3D_control were used. The results of GSEA are considered significant when the FDR and nominal p value are less than 0.05.

Network Analysis

The interactome of proteins in Homo sapiens were obtained from STRING (https://string-db.org/, v10.5). To identify the network between PD and the TXNIP gene, Cytoscape (http://www.Cytoscape.org, v3.6.1) included the DEGs of 3D_LRRK2/3d_Control and the gene set of the CTD.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Values of n indicate the number of independent experiments performed or the number of individual experiments or mice. For each independent in vitro experiment, at least three technical replicates were used, and a minimum of three independent experiments were performed to ensure adequate statistical power. In all of the analyses, group differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). ANOVA was used for multicomponent comparisons and Student's t test was used for two-component comparisons after a normal distribution was confirmed.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Information files or from the corresponding author upon request.

Author Contributions

H.K. and H.J.P. performed the experiments. H.C., Y.C., H.P., J.S., Junyeop Kim, C.J.L., and Y.K.L. performed the data analysis. H.K. and Jongpil Kim designed the study. Jongpil Kim contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korea Government (NRF-2017M3A9C6029306), and Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, HI16C1176, Republic of Korea.

Published: February 21, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.01.020.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the microarray data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE125234.

Supplemental Information

References

- Arenas E. Wnt signaling in midbrain dopaminergic neuron development and regenerative medicine for Parkinson's disease. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;6:42–53. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral S., Beltramo R., Salio C., Aimar P., Lossi L., Merighi A. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX in the mouse brain from development to senescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:1554–1573. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal M.F. Experimental models of Parkinson's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:325–334. doi: 10.1038/35072550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershteyn M., Nowakowski T.J., Pollen A.A., Di Lullo E., Nene A., Wynshaw-Boris A., Kriegstein A.R. Human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids model cellular features of lissencephaly and reveal prolonged mitosis of outer radial glia. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:435–449.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers B., Lee H.L., Reijo Pera R. Modeling Parkinson's disease using induced pluripotent stem cells. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2012;12:237–242. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0270-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.Y., Weng Y.H., Chien K.Y., Lin K.J., Yeh T.H., Cheng Y.P., Lu C.S., Wang H.L. (G2019S) LRRK2 activates MKK4-JNK pathway and causes degeneration of SN dopaminergic neurons in a transgenic mouse model of PD. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1623–1633. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesselet M.F., Fleming S., Mortazavi F., Meurers B. Strengths and limitations of genetic mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008;14(Suppl 2):S84–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.H., Kim Y.H., Hebisch M., Sliwinski C., Lee S., D'Avanzo C., Chen H., Hooli B., Asselin C., Muffat J. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2014;515:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.Y., Khurana V., Auluck P.K., Tardiff D.F., Mazzulli J.R., Soldner F., Baru V., Lou Y., Freyzon Y., Cho S. Identification and rescue of alpha-synuclein toxicity in Parkinson patient-derived neurons. Science. 2013;342:983–987. doi: 10.1126/science.1245296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerniecki S.M., Cruz N.M., Harder J.L., Menon R., Annis J., Otto E.A., Gulieva R.E., Islas L.V., Kim Y.K., Tran L.M. High-throughput screening enhances kidney organoid differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells and enables automated multidimensional phenotyping. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:929–940.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher J.P., Abdelmotilib H.A., Hu X., Volpicelli-Daley L.A., Moehle M.S., Fraser K.B., Needle E., Chen Y., Steyn S.J., Galatsis P. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) pharmacological inhibition abates alpha-synuclein gene-induced neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:19433–19444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher J.P., Pletnikova O., Biskup S., Musso A., Gellhaar S., Galter D., Troncoso J.C., Lee M.K., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L. Neurodegenerative phenotypes in an A53T alpha-synuclein transgenic mouse model are independent of LRRK2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2420–2431. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fonzo A., Rohe C.F., Ferreira J., Chien H.F., Vacca L., Stocchi F., Guedes L., Fabrizio E., Manfredi M., Vanacore N. A frequent LRRK2 gene mutation associated with autosomal dominant Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2005;365:412–415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley J.M., Lees A.J. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson B.I., Duda J.E., Quinn S.M., Zhang B., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro P.S., Gerhardt E., Lopes da Fonseca T., Bahr M., Outeiro T.F., Eckermann K. LRRK2 promotes tau accumulation, aggregation and release. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53:3124–3135. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunjima K., Tomiyama R., Takakura K., Yamada T., Hashida K., Nakamura Y., Konishi T., Matsugo S., Hori O. 3,4-Dihydroxybenzalacetone protects against Parkinson's disease-related neurotoxin 6-OHDA through Akt/Nrf2/glutathione pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2014;115:151–160. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson M.X., Peng C., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M.Y. LRRK2 activity does not dramatically alter alpha-synuclein pathology in primary neurons. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:45. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogberg H.T., Bressler J., Christian K.M., Harris G., Makri G., O'Driscoll C., Pamies D., Smirnova L., Wen Z., Hartung T. Toward a 3D model of human brain development for studying gene/environment interactions. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013;4(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/scrt365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Wang Y., He Q., Li L., Xie H., Zhao Y., Zhao J. Nrf2 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulating Trx1/TXNIP complex in cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Behav. Brain Res. 2018;336:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.H., Shaltouki A., Gonzalez A.E., Bettencourt da Cruz A., Burbulla L.F., St Lawrence E., Schule B., Krainc D., Palmer T.D., Wang X. Functional impairment in Miro degradation and mitophagy is a shared feature in familial and sporadic Parkinson's disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:709–724. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C.H., Chan D., Wolozin B. LRRK2 and the stress response: interaction with MKKs and JNK-interacting proteins. Neurodegener. Dis. 2010;7:68–75. doi: 10.1159/000285509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Xiao Y., Sun A.X., Cukuroglu E., Tran H.D., Goke J., Tan Z.Y., Saw T.Y., Tan C.P., Lokman H. Midbrain-like organoids from human pluripotent stem cells contain functional dopaminergic and neuromelanin-producing neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelava I., Lancaster M.A. Stem cell models of human brain development. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkeby A., Grealish S., Wolf D.A., Nelander J., Wood J., Lundblad M., Lindvall O., Parmar M. Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Rep. 2012;1:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.K., Stirling W., Xu Y., Xu X., Qui D., Mandir A.S., Dawson T.M., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Price D.L. Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson's disease-linked Ala-53-->Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with alpha-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:8968–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132197599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Parisiadou L., Gu X.L., Wang L., Shim H., Sun L., Xie C., Long C.X., Yang W.J., Ding J. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson's-disease-related mutant alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2009;64:807–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D., Dowman J., Hammond R., Leete T., Inoue K., Abeliovich A. The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron. 2006;52:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni C., Lewis P.A. Dysfunction of the autophagy/lysosomal degradation pathway is a shared feature of the genetic synucleinopathies. FASEB J. 2013;27:3424–3429. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E., Rockenstein E., Veinbergs I., Mallory M., Hashimoto M., Takeda A., Sagara Y., Sisk A., Mucke L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C., Jain S., Evans E.W., Gilks W.P., Simon J., van der Brug M., Lopez de Munain A., Aparicio S., Gil A.M., Khan N. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja W.K., Mungenast A.E., Lin Y.T., Ko T., Abdurrob F., Seo J., Tsai L.H. Self-organizing 3D human neural tissue derived from induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulate Alzheimer's disease phenotypes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapansky J., Khasnavis S., DeAndrade M.P., Nardozzi J.D., Falkson S.R., Boyd J.D., Sanderson J.B., Bartels T., Melrose H.L., LaVoie M.J. Familial knockin mutation of LRRK2 causes lysosomal dysfunction and accumulation of endogenous insoluble alpha-synuclein in neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;111:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova O.A., Horikawa I., Zimonjic D.B., Popescu N.C., Bonner W.M., Barrett J.C. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:168–170. doi: 10.1038/ncb1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreq L., Rose J., Soreq E., Hardy J., Trabzuni D., Cookson M.R., Smith C., Ryten M., Patani R., Ule J. Major shifts in glial regional identity are a transcriptional hallmark of human brain aging. Cell Rep. 2017;18:557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M.G., Schmidt M.L., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Jakes R., Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C.J., Feng Y., Liu T.T., Liu X., Bao J.J., Shi A.M., Hu D.M., Liu T., Yu Y.L. Thioredoxin-interacting protein induced alpha-synuclein accumulation via inhibition of autophagic flux: implications for Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017;23:717–723. doi: 10.1111/cns.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D., Bogulavsky J., Larsen K.E., Behr G., Karatekin E., Kleinman M.H., Turro N., Krantz D., Edwards R.H., Greene L.A. Neuromelanin biosynthesis is driven by excess cytosolic catecholamines not accumulated by synaptic vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasato M., Er P.X., Chiu H.S., Maier B., Baillie G.J., Ferguson C., Parton R.G., Wolvetang E.J., Roost M.S., Chuva de Sousa Lopes S.M. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature. 2015;526:564–568. doi: 10.1038/nature15695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkner M., Zschatzsch M., Rostovskaya M., Overall R.W., Busskamp V., Anastassiadis K., Karl M.O. Retinal organoids from pluripotent stem cells efficiently recapitulate retinogenesis. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;6:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli-Daley L.A., Abdelmotilib H., Liu Z., Stoyka L., Daher J.P., Milnerwood A.J., Unni V.K., Hirst W.D., Yue Z., Zhao H.T. G2019S-LRRK2 expression augments alpha-synuclein sequestration into inclusions in neurons. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:7415–7427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3642-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Huang X., Zhang K., Mao X., Ding X., Zeng Q., Bai S., Xuan Y., Peng H. Vanadate oxidative and apoptotic effects are mediated by the MAPK-Nrf2 pathway in layer oviduct magnum epithelial cells. Metallomics. 2017;9:1562–1575. doi: 10.1039/c7mt00191f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo D.H., Chen Q., Yang T.L., Glineburg M.R., Hoge C., Leu N.A., Johnson F.B., Lengner C.J. Enhancing a Wnt-telomere feedback loop restores intestinal stem cell function in a human organotypic model of dyskeratosis congenita. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplemental Information files or from the corresponding author upon request.