Abstract

Five Schiff bases derived from melamine have been used as efficient additives to reduce the process of photodegradation of poly(vinyl chloride) films. The performance of Schiff bases has been investigated using various techniques. Poly(vinyl chloride) films containing Schiff bases were irradiated with ultraviolet light and any changes in their infrared spectra, weight, and the viscosity of their average molecular weight were investigated. In addition, the surface morphology of the films was inspected using a light microscope, atomic force microscopy, and a scanning electron micrograph. The additives enhanced the films resistance against irradiation and the polymeric surface was much smoother in the presence of the Schiff bases compared with the blank film. Schiff bases containing an ortho-hydroxyl group on the aryl rings showed the greatest photostabilization effect, which may possibly have been due to the direct absorption of ultraviolet light. This phenomenon seems to involve the transfer of a proton as well as several intersystem crossing processes.

Keywords: poly(vinyl chloride), melamine, Schiff bases, ultraviolet irradiation, carbonyl group index, photostabilization, weight loss

1. Introduction

Plastics have unique chemical and physical properties and low production costs. They are produced in huge quantities and are involved in various applications [1]. However, the chemical industry has come under severe pressure of late to overcome the problems created due to the use of plastics, such as the amount of waste generated, the nature of such waste, and their detrimental effect on the environment. In addition, one of the main concerns is how the properties of plastics may be improved for long term use [2]. Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) is a common and versatile thermoplastic that is utilized in daily applications ranging from food packaging to medical devices.

PVC is cheap and has relatively high chemical and biological resistance. However, PVC has poor thermal and mechanical stability. In addition, most of the common forms of synthetized PVC suffer from a particular dehydrochlorination process when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light for long periods, particularly at high temperatures [3]. Such processes lead to the formation of carbon–carbon double bonds within the polymeric chains due to the elimination of hydrogen chloride (HCl), and may also cause discoloration, deformation, cracking, and loss of mechanical properties [4]. Moreover, the degradation of PVC in landfill sites is slow under natural conditions [5]. Therefore, the PVC waste has to be either incinerated, or picked and recycled, at the various landfill sites where it ends up [6]. The incineration of PVC produces toxic by-products that not only pollute the environment but also harm soil and groundwater [7]. Therefore, the incorporation of thermal and UV stabilizers within the polymeric matrix could be a solution to enhance the properties of PVC [8,9].

The PVC additives should be compatible with the polymeric chains and should not alter the color of the product. Moreover, they should be stable, non-volatile, and cheap to produce [10]. The most common PVC additives are metal complexes [11,12,13,14], aromatic rich compounds [15,16,17,18], Schiff bases [19,20,21,22], nanomaterials, flame retardants, and pigments [23,24,25]. However, stabilizers containing heavy metals are not good for the long-term protection of PVC since the metals have a tendency to leach out, thereby causing environmental and health problems. Titanium dioxide can be used as a PVC additive since it acts as an effective UV light absorber [26,27]. However, titanium dioxide is also known as a photocatalyst and, therefore, accelerates PVC surface weathering and degradation [28]. Accordingly, there is still room to develop new PVC additives that are efficient, easy to produce, highly aromatic, and act as both thermal and UV stabilizers. Melamine is aromatic, odorless, non-toxic, cheap, and highly stable. It is used in various industrial applications, such as corrosion inhibitors [29,30,31]. Therefore, we became interested in the use of melamine-based additives to reduce the effects of photodegradation of PVC. Now, we aim to report the synthesis of Schiff bases containing melamine as efficient PVC photostabilizers as part of our interest in the field of polymers [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Schiff Bases 1−5

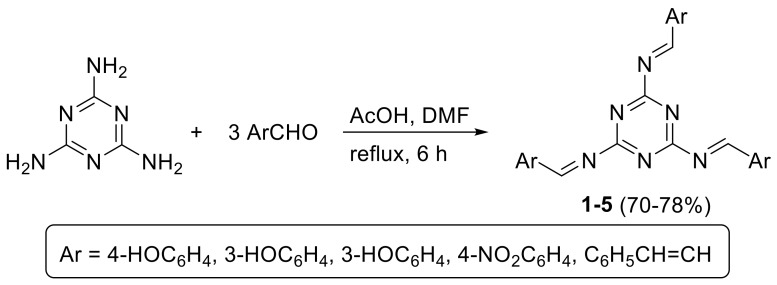

Schiff bases 1–5 were synthesized based on a previously reported procedure [40] from the condensation of melamine and three molar equivalents of aromatic aldehydes—namely 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 3-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 4-nitrobenzaldehyde and cinnamaldehyde—in boiling dimethylformamide containing acetic acid (Figure 1). Schiff bases 1–5 were obtained in 70–78% yields as pale-yellow solids. The elemental analyses and some physical properties for 1–5 are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of Schiff bases 1–5.

Table 1.

Elemental analyses and some physical properties for Schiff bases 1−5.

| Additive | Ar | Yield (%) | Melting Point (°C) | Calcd. (Found; %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | ||||

| 1 | 2-HOC6H4 | 71 | 293−295 | 65.75 (66.03) | 4.14 (4.34) | 19.17 (19.03) |

| 2 | 3-HOC6H4 | 78 | 288−289 | 65.75 (65.94) | 4.14 (4.31) | 19.17 (19.22) |

| 3 | 4-HOC6H4 | 73 | 274−275 | 65.75 (65.95) | 4.14 (4.24) | 19.17 (19.19) |

| 4 | 4-NO2C6H4 | 76 | 266−267 | 54.86 (54.89) | 2.88 (2.97) | 23.99 (24.07) |

| 5 | C6H5CH=CH | 70 | 274−275 | 76.90 (77.13) | 5.16 (5.91) | 17.94 (17.79) |

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of 1–5 (Table 2) showed strong absorption peaks at 1632–1647 cm–1 region due to the vibration of azomethine bonds. The vibrations of aromatic C=C and triazine C=N bonds appeared at 1438–1465 and 1539–1543 cm–1 region, respectively. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra showed characteristic singlets that resonated within the 8.48–9.29 ppm region corresponding to the azomethine protons (Table 3).

Table 2.

Some Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectral data for Schiff bases 1–5.

| Stabilizer | FR-IR (υ, cm−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH | CH=N | C=N (Ar) | C=C (Ar) | |

| 1 | 3332 | 1632 | 1539 | 1465 |

| 2 | 3338 | 1639 | 1546 | 1462 |

| 3 | 3335 | 1643 | 1543 | 1438 |

| 4 | - | 1639 | 1543 | 1458 |

| 5 | - | 1647 | 1543 | 1465 |

Table 3.

1H-NMR spectral data for 1–5.

| Stabilizer | 1H-NMR (400 MHz: DMSO-d6, ppm) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 11.22 (br. s, exch., 3 H, OH), 8.49 (s, 3 H, CH=N), 7.61 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 3 H, Ar), 7.01 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 3 H, Ar), 6.58 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 3 H, Ar), 5.99 (s, 3 H, Ar) |

| 2 | 11.15 (br. s, exch., 3 H, OH), 9.29 (s, 3 H, CH=N), 7.45–7.33 (m, 9 H, Ar), 7.15 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 3 H, Ar) |

| 3 | 10.36 (br. s, exch., 3 H, OH), 9.26 (s, 3 H, CH=N), 7.75 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 6 H, Ar), 6.90 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 6 H, Ar) |

| 4 | 9.28 (s, 3 H, CH=N), 8.44–8.14 (m, 12 H, Ar) |

| 5 | 9.28 (s, 3 H, CH=N), 7.95–7.55 (m, 9 H, Ar), 7.49–7.42 (m, 9 H, CH and Ar), 6.68 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3 H, CH) |

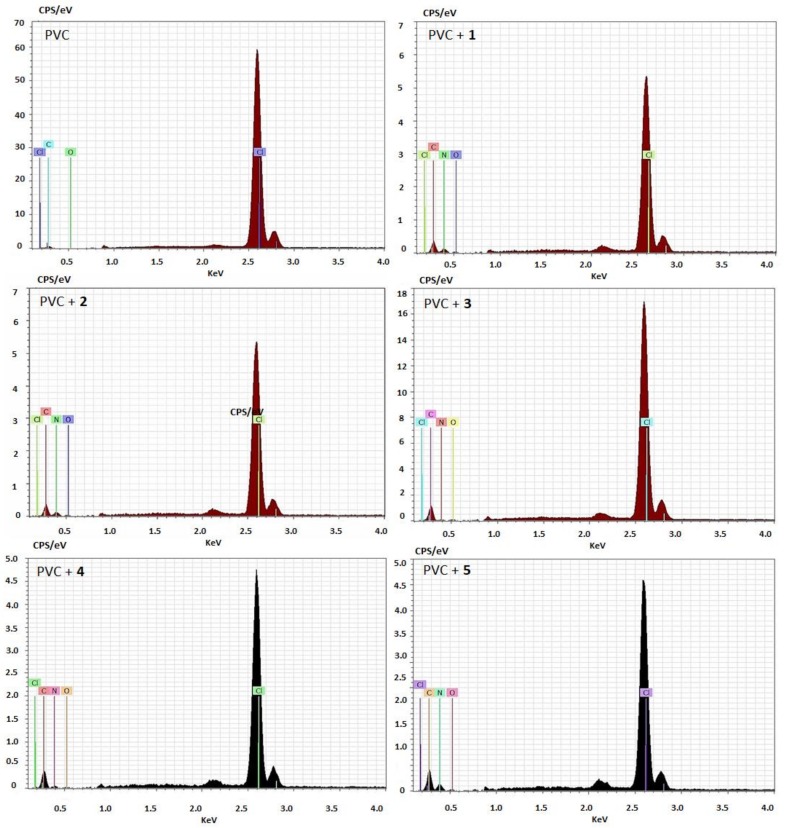

2.2. Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy

Schiff bases 1–5 (0.5% by weight) were incorporated within the PVC matrix to produce blends. Following this, energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy was used to determine the elements within the polymeric materials. The EDX patterns for PVC/1–5 blends clearly showed the appearance of a new band that corresponded with the nitrogen atoms of the additives (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) patterns of poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC).

2.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

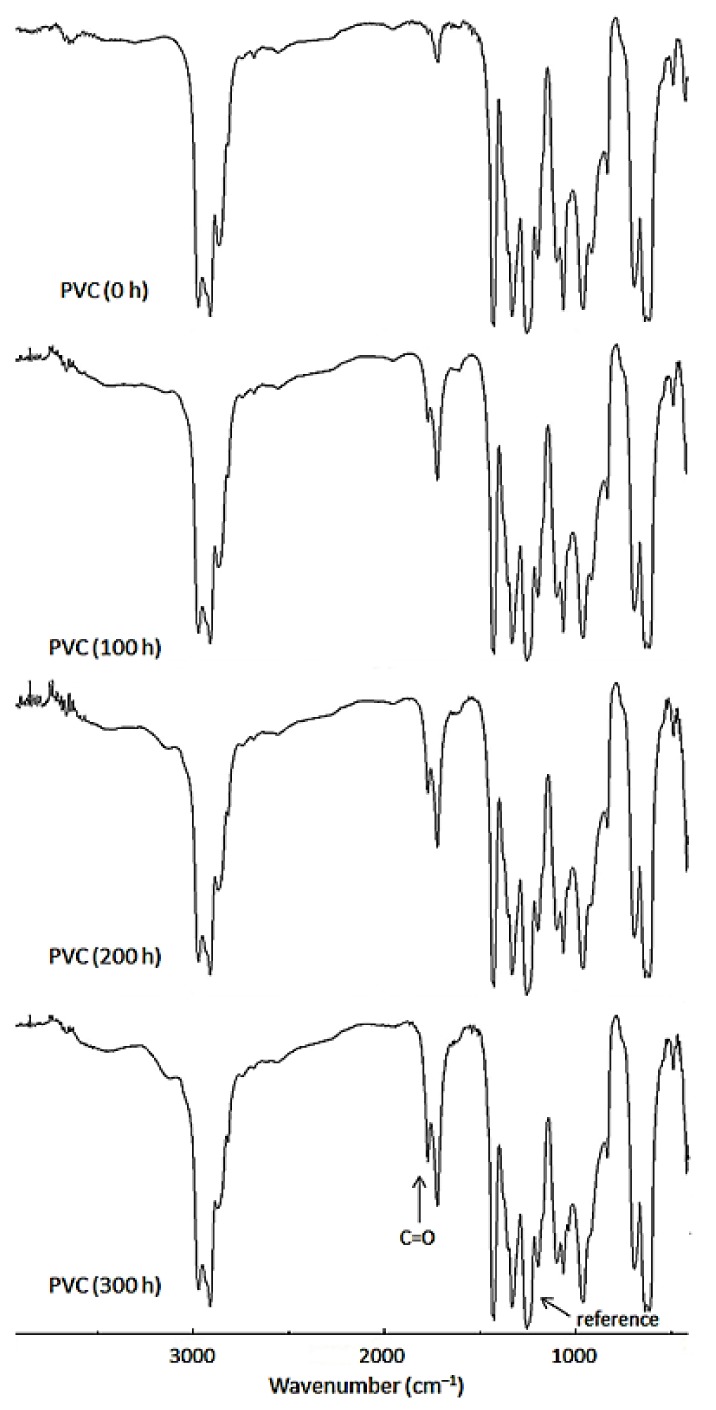

Photo-oxidation of PVC leads to several photo-products [41]. The most common oxygenated products are aldehydes, chloroketones, chlorocarboxylic acids, and acid chlorides [41]. The carbonyl-containing fragments can be detected in the FTIR spectra upon irradiation. Therefore, PVC films (40 μm in thickness) were irradiated with a UV light (λmax = 313 nm) for different time periods and the FTIR spectra were subsequently recorded. The FTIR spectra for PVC (blank) before (0 h) and after irradiation (100, 200, and 300 h) are represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Changes in FTIR spectra of PVC upon irradiation.

Figure 3 clearly shows that the intensity of the peak at 1722 cm–1—corresponding to carbonyl group (C=O) vibration—became apparent upon irradiation, and its intensity increased as the irradiation time increased. Accordingly, the intensity of the C=O group in the FTIR spectra was monitored upon irradiation and compared to a reference peak of 1328 cm–1, which corresponds with the C–H bond in the CH2 units of PVC [42]. The carbonyl group index (IC=O) was then calculated from the absorption intensity for both C=O (As) and reference (Ar) peaks using Equation (1).

| (1) |

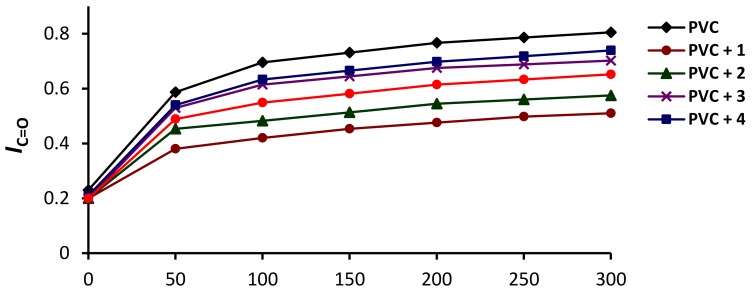

The IC=O index for the irradiated PVC films, both in the presence and absence of the Schiff bases 1–5 (0.5% w/w), was calculated and plotted against the irradiation time (Figure 4). The changes in the IC=O were sharp in the first 50 h and then increased gradually up to 300 h. The changes in the IC=O were larger for the PVC (blank) film compared with those obtained for the PVC/1–5 films. For example, the IC=O was 0.8 for the PVC (blank) compared to 0.5 for the PVC/1 blend, after 300 h of irradiation. Evidently, the addition of 1–5 led to a significant photostabilization for PVC, with Schiff base 1 deemed to be the most effective additive out of those that were used.

Figure 4.

Changes in the IC=O of PVC upon irradiation.

Irradiation of PVC leads to the production of excited electrons that can cause damage to the polymeric chains [43,44]. Azomethine groups within Schiff bases 1–5 lead to the release of irradiation energy at a rate that is not harmful to the polymeric chains. The triazine moiety within bases 1–5 could also potentially reduce the photodegradation of PVC through the direct absorption of UV light, and as a result, such energy is converted to harmless heat. However, this is less significant when compared with the stabilizing effect of the azomethine group [15]. The polarity of the C=N bond within the triazine rings and azomethine groups could lead to an attraction developing between the nitrogen atoms and the polarized carbons of the C–Cl bonds within the polymeric chains through coordination bonds [15]. Such coordination bonds might help in the transmission of irradiation energy to additives from the excited PVC chains. In addition, bases 1–5 act as radical scavengers since they are aromatic rich. Moreover, in the presence of a radical residue (chromophore), the additives 1–5 form complexes with PVC chains that can be stabilized through a resonance effect within the aryl rings [45].

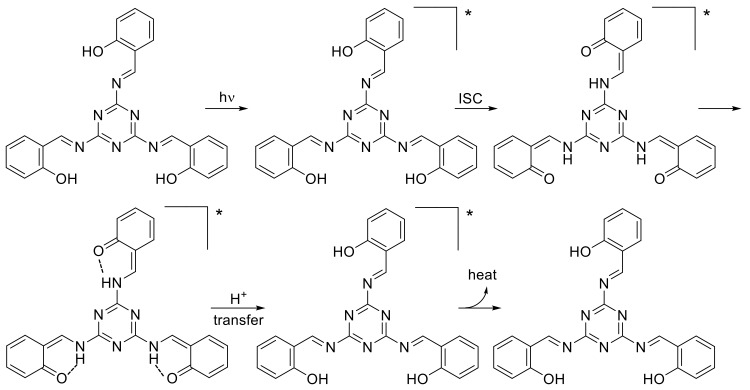

The order of additives in the PVC photostabilization was 1, 2, 3, 5 and 4. Schiff bases 1–3 contain a hydroxyl group, whilst 4 contains a nitro group, and 5 contains a conjugated double bond with the aryl ring. Schiff bases containing hydroxyl groups showed the most stabilizing effect for PVC films compared to the other ones. The hydroxyl group can act as a radical scavenger in which the ortho-hydroxy moiety (Schiff base 1) showed the highest efficiency compared to the others (i.e., Schiff bases 1 and 2). Such ortho-arrangement leads to the formation of a stable excited state due to hydrogen bonding (Figure 5) as a result of proton transfer and intersystem crossing (ISC) processes between the excited states [46].

Figure 5.

Photostabilization of PVC containing Schiff base 1. * represents the excited state.

2.4. Weight Loss

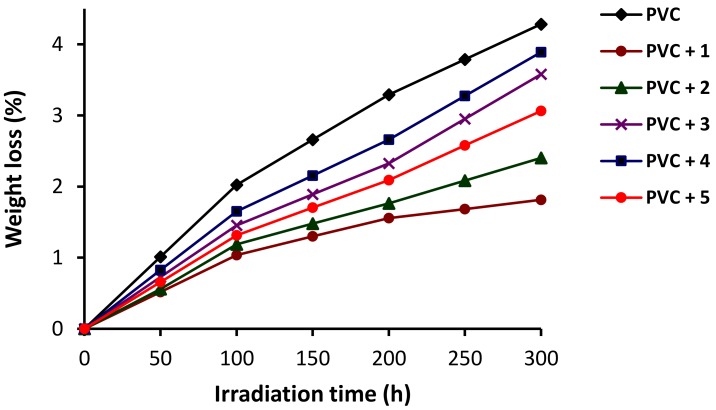

The photodegradation or thermal decomposition of PVC leads to the formation of hydrogen chloride and polyene fragments, which cause pyrolysis at high temperature [44]. The PVC dehydrochlorination process leads to a loss in weight along with discoloration and the production of toxic volatile pollutants [47,48]. Therefore, the weight loss percentage due to the irradiation of PVC could be used as a measure for the level of photodegradation. Therefore, PVC films were irradiated, and the weight loss percentage was calculated by subtracting the weight of the film after irradiation (W2) from the weight before irradiation (W1) using Equation (2). The changes in weight upon irradiation of the PVC films are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Changes in weight loss (%) of PVC upon irradiation.

| (2) |

The weight loss of PVC was sharp in the first 100 h of irradiation and was more noticeable in the PVC (blank) film. After 300 h of irradiation, the PVC film in the absence of the Schiff bases lost 4.3% of its weight compared to 1.8% when Schiff base 1 was used. Other Schiff bases led to a weight loss in the range of 2.4–3.9% (after 300 h).

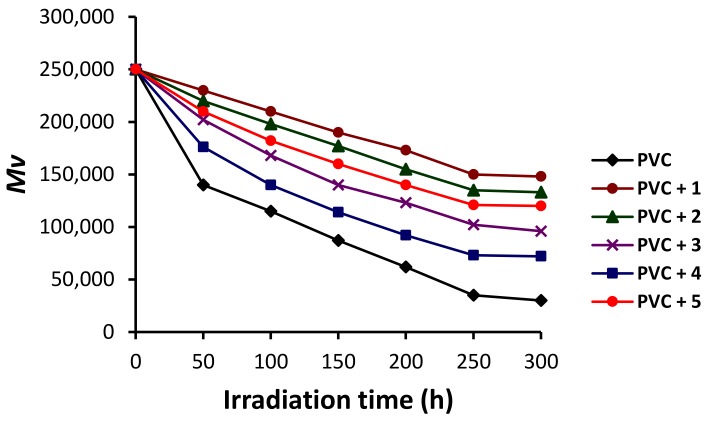

2.5. Viscosity Average Molecular Weight

Viscometry provides important information about the shape, dimensions, and size of polymeric particles. The measurement of intrinsic viscosity () of polymers in solution is a simple and fast method that can be used to determine the average molecular weight (). The can be calculated using Equation (3), where, K and α are constants [49,50]. The photodegradation of PVC leads to small molecular weight fragments, which causes a depression in the [51,52].

| (3) |

Therefore, the PVC films were irradiated, then dissolved in tetrahydrofuran, and was measured after 50 h intervals of irradiation. The changes in (Figure 7) were very sharp at the start of the irradiation process (during the first 50 h) and more or less constant in the last 50 h (from 250 to 300 h). The reduction in was significant in the absence of the Schiff bases compared to those obtained when additives 1–5 were used. The of the PVC (blank) dropped from 250,000 to 140,000 after 50 h of irradiation. After 250 h of irradiation, the blank PVC lost 86% of its compared to 40% in the case of the PVC/1 film.

Figure 7.

Changes in the of PVC upon irradiation.

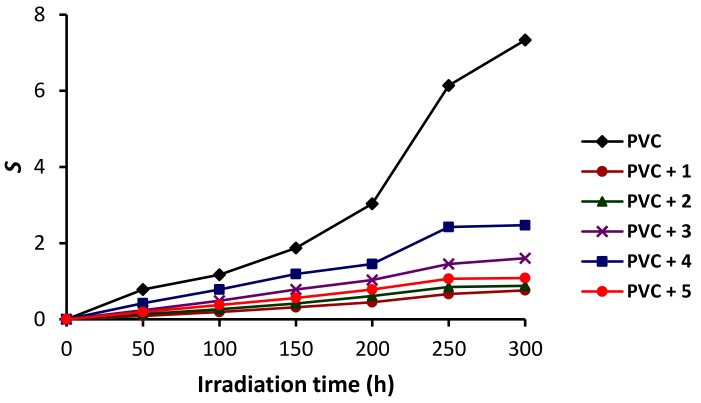

In order to prove the results shown in Figure 7, the PVC chain sessions (S) were calculated using the molecular weight of the non-irradiated PVC films () and those after a specific time (t) of irradiation () using Equation (4). The value of S gives an indication of the degree of cross-linking and branching that took place within the PVC polymeric chains due to irradiation [53].

| (4) |

Indeed, the irradiation of PVC films leads to the presence of some insoluble residues forming in tetrahydrofuran as a result of chain sessions. Figure 8 shows that the S value was high (7.33) for the PVC (blank) compared with those obtained for the PVC/1–5 films (0.76 to 2.47). Again, the PVC/1 film produced the lowest S value (0.76).

Figure 8.

Changes in the S values of PVC upon irradiation.

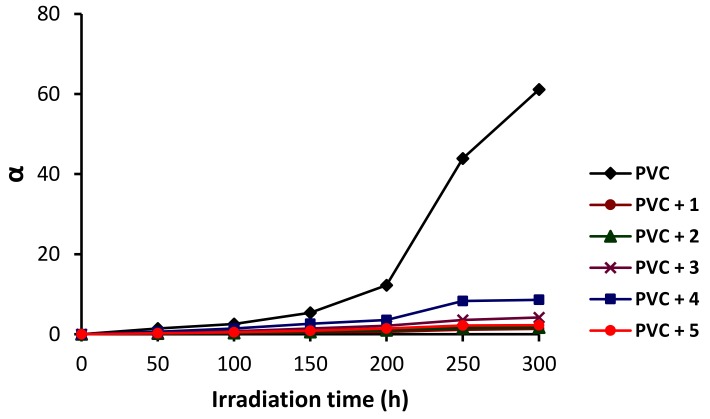

The photodegradation of polymers is also related to the deterioration degree (α), which reflects the number of weak bonds broken in the early stages of the irradiation process. The value of α depends on the molecular weight (m), S value, and as shown in Equation (5).

| (5) |

Therefore, the deterioration degree (α) was calculated for the PVC films and plotted versus the irradiation time (Figure 9). The changes in α value were dramatic for the PVC (blank) film, where α changed from 0 at the start of the irradiation process to 61 after 300 h of irradiation. However, α was very low (up to 8.6) for the PVC/1–5 blends after irradiation (300 h). For the PVC/1 blend, after 300 h of irradiation, α was also very low (1.3), which clearly highlights the significant and efficient role that Schiff base 1 played as an inhibitor for PVC photodegradation.

Figure 9.

Changes in the α values of PVC upon irradiation.

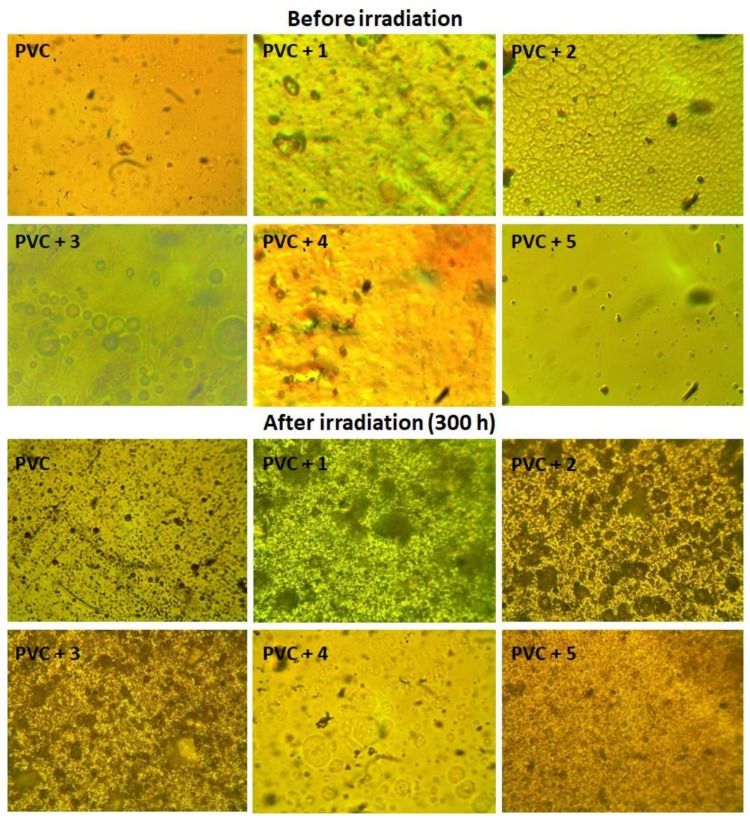

2.6. Microscopic Surface Morphology

In order to see what effect irradiation could have on the surface morphology of PVC films, a microscope with 400× magnification power was used to inspect the surface. The surfaces of both irradiated and non-irradiated PVC films were inspected, with the captured images being shown in Figure 10. It was clear that the PVC surfaces displayed a high degree of regularity and smoothness before the irradiation process compared with those obtained after irradiation (300 h). The number of cracks and white spots was also significant in the case of the PVC (blank) film when compared with the ones for the PVC/1–5 blends. Such results proved once more that Schiff bases 1–5 act as UV absorbers and can reduce the surface damage, photo-oxidation, decomposition, and cross-linking of PVC upon irradiation. The surface morphology of the PVC/1 blend was less rough, however, and contained fewer numbers of white spots and cracks compared with the surfaces of the PVC containing other Schiff bases.

Figure 10.

Microscope images (400× magnification) of PVC.

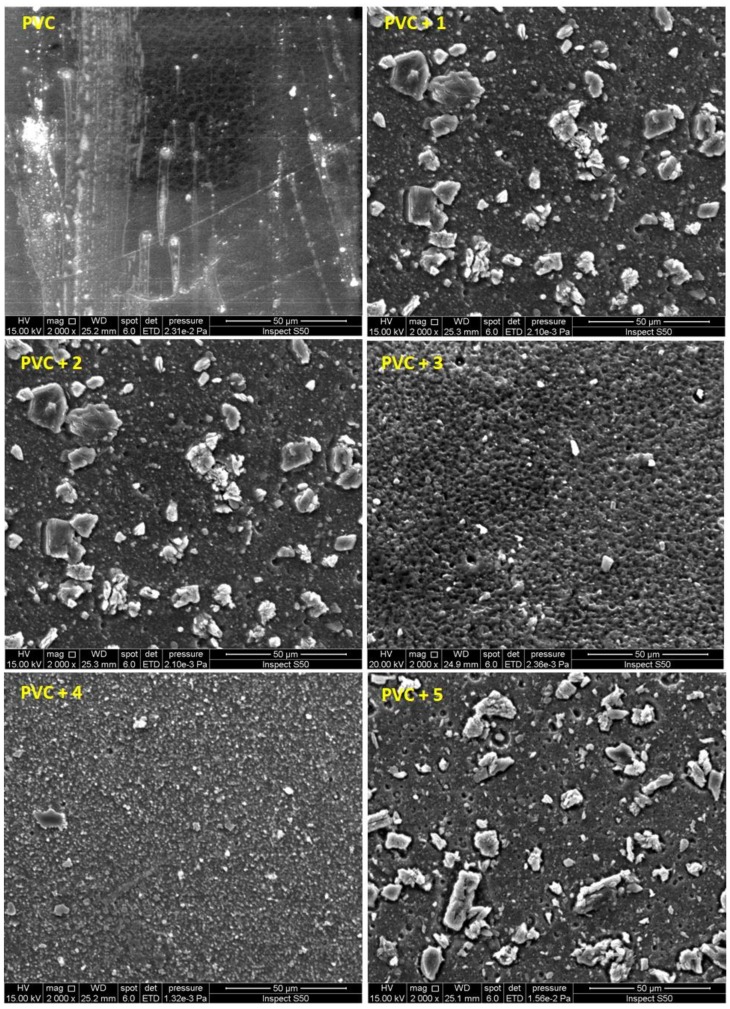

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a useful technique that can be used to test the compatibility of various components within polymeric materials. Such a technique can detect the various interfaces and separation phases within the polymeric matrix, which reflect both mechanical and thermal stability properties, and ionic conductivity [54]. Moreover, SEM images provide information about particle shape and size. It has been reported that the SEM images for the non-irradiated PVC (blank) and PVC/additive blends showed smooth and neat surfaces with a high degree of homogeneity [14,32,33]. The SEM images, captured at an accelerating voltage of 15.00 KV, for the irradiated PVC (after 300 h of irradiation) are shown in Figure 11. The PVC (blank) surface had noticeable damage compared to the damage seen in the PVC films containing bases 1–5. The cross-linking and evolution of hydrogen chloride and other volatile products leads to the formation of an ice-rock-like structure [55,56,57]. Incidentally, the SEM image for the irradiated PVC/1 film showed the least surface damage.

Figure 11.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (50 μm) of PVC after irradiation.

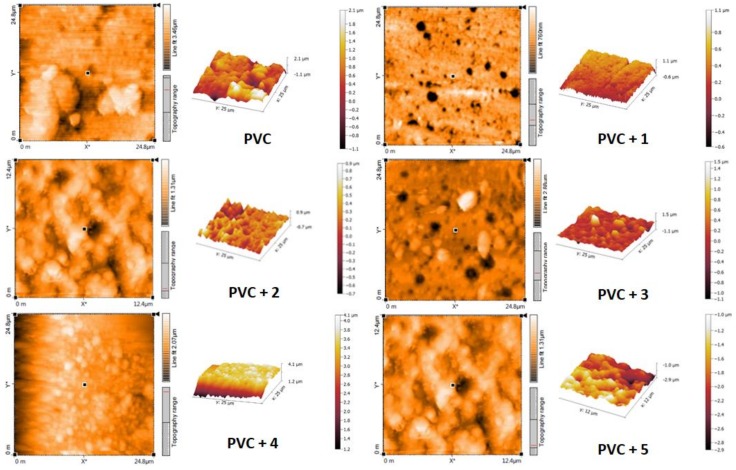

2.8. Atomic Force Microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool used to investigate surface roughness and pore size, and provides two and three-dimensional images for polymer surfaces [58]. Irradiated PVC films (5 × 5 μm2) were scanned with AFM and the topographic images produced are shown in Figure 12. Moreover, the AFM images of the PVC films containing Schiff bases 1–5 showed spherical shape aggregates (clusters) and fewer holes compared with the blank PVC film.

Figure 12.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of PVC after irradiation.

The surface roughness factor (Rq) of the irradiated PVC was calculated, the results of which are reported in Table 4. The roughness factor was very high (Rq = 159.5) for the blank PVC film compared with those obtained for the irradiated PVC/1–5 films (Rq = 15.5–29.1). The high Rq for the blank PVC film could be caused by the high rate of dehydrochlorination, which in turn leads to the removal of leachable residues from the surface of the polymer. Evidently, Schiff bases 1–5 play a significant role in the inhibition of PVC photodegradation upon irradiation.

Table 4.

The Rq values for the PVC films after irradiation.

| Irradiated PVC (300 h) | Rq |

|---|---|

| PVC (blank) | 159.5 |

| PVC + 1 | 15.5 |

| PVC + 2 | 24.3 |

| PVC + 3 | 27.5 |

| PVC + 4 | 29.1 |

| PVC + 5 | 26.5 |

3. Experimental

3.1. General

The PVC powder used in this experiment (grade K67) was provided free of charge from Petkim Petrokimya (Istanbul, Turkey). The melamine, aromatic aldehydes, and the solvents that were used were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (Gillingham, UK). The thickness of the PVC film (ca. 40 µm) was measured using a Digital Caliper DIN 862 micrometer (Vogel GmbH, Kevelaer, Germany). The PVC morphological images were captured using a Meiji Techno microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The AFM images were recorded on a Veeco instrument (Plainview, NY, USA). The SEM images (accelerating voltage = 15 KV) were captured on an Inspect S50 microscope (FEI Company, Czechia, Czech Republic). A Varian Mercury-300 spectrometer (Varian, Mundelein, IL, USA) was used to record the 1H-NMR spectra (300 MHz). The PVC viscosity was measured using an Ostwald U-Tube viscometer (Ambala, Haryana, India). Aluminum plates with a thickness of 0.6 mm (Q-panel Company, Homestead, FL, USA) were used to fix the films. A Kerry PUL 55 ultrasonic bath (Kerry Ultrasonics Ltd., Hitchin, UK) was used for the preparation of the PVC blends.

3.2. Synthesis of Schiff Bases 1–5

Melamine (0.5 g, 4.0 mmol) in dimethylformamide (40 mL) was stirred at 120 °C until the solid completely dissolved. A solution of aromatic aldehyde (13.2 mmol) in dimethylformamide (5 mL) containing glacial acetic acid (0.2 mL) was then added, and the mixture was stirred for a further 6 h under reflux. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, and toluene (120 mL) was added slowly in order to precipitate the products. The solid obtained was collected by filtration, washed with a mixture of methanol and toluene (1:1 by volume), and then dried in a vacuum oven.

3.3. Preparation of PVC Films

A solution of PVC (5.0 g) and 1–5 (25 mg) in tetrahydrofuran (100 mL) was left in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min. The homogenous solution obtained was cast onto glass plates containing 15 holes (4 × 4 cm2; ca. 40 µm), and the films were left to dry at 25 °C for 24 h.

3.4. Accelerated Ultraviolet Weathering Tests

The PVC films were irradiated at room temperature using an accelerated weather-meter QUV tester (Philips, Saarbrücken, Germany) equipped with UV-B 313 lamps (λmax = 313 nm; light intensity = 6.2 × 10–9 ein dm–3 s–1).

4. Conclusions

Five Schiff bases containing melamine were utilized as photostabilizers for poly(vinyl chloride) films against irradiation with ultraviolet light. The photostabilization of poly(vinyl chloride) films containing Schiff bases was found to have increased significantly. Notably, the polymeric weight loss, reduction in the average molecular weight, and carbonyl group index were low in the presence of the additives when compared to the blank film. The atomic force microscopy, scanning electron micrograph, and the optical microscope images for the poly(vinyl chloride) films containing the additives showed a much smoother surface and a lower number of cracks compared to the blank film after irradiation. In addition, the scanning electron micrograph of the polymer doped with additives looked like a piece of ice-rock in structure—with heterogeneous surface morphology—after undergoing a long period of irradiation.

Author Contributions

G.A.E.-H., M.H.A., A.A.A., B.A.H., A.A., H.H., and E.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. D.S.A. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. G.A.E.-H., E.Y. and D.S.A. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and improved the final text of the paper.

Funding

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the College of Applied Medical Sciences Research Centre and the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for their funding of this research, and to Al-Nahrain and Al-Mansour Universities for their continued support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of Schiff bases are available from the authors upon request.

References

- 1.Keneghan B., Egan L. Plastics: Looking at the Future and Learning from the Past. Archetype Publications Ltd.; London, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shashoua Y. Conservation of Plastics: Material Science: Degradation and Preservation. Butterworth-Heinemann; London, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Z., Ding A., Guo H., Lu G., Huang X. Construction of nontoxic polymeric UV-absorber with great resistance to UV-photoaging. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25508. doi: 10.1038/srep25508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mango L.A., Lenz R.W. Hydrogenation of unsaturated polymers with diimide. Makromol. Chem. 1973;163:13–36. doi: 10.1002/macp.1973.021630102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadat-Shojai M., Bakhshandeh G.-R. Recycling of PVC wastes. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2011;96:404–415. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman S. Ph.D. Thesis. Imperial College; London, UK: 2014. The Microwave Induced Pyrolysis of Problematic Plastics Enabling Recovery and Component Reuse. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baishya P., Mahanta D.K. Improvised segregation of recyclable materials in Guwahati city, India: A case study. Clarion J. 2013;2:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallakpour S., Sadeghzadeh R. A benign and simple strategy for surface modification of Al2O3 nanoparticles with citric acid and L(+)-ascorbic acid and its application for the preparation of novel poly(vinyl chloride) nanocomposite films. Adv. Polym. Techol. 2017;36:409–417. doi: 10.1002/adv.21622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterzyński T., Tomaszewska J., Piszczek K., Skórczewska K. The influence of carbon nanotubes on the PVC glass transition temperature. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010;70:966–969. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadogan D.F., Howick C.J. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2000. Plasticizers. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousif E., Salimon J., Salih N., Jawad A., Win Y.-F. New stabilizers for PVC based on some diorganotin(IV) complexes with bezamidoleucine. Arab. J. Chem. 2016;9:S1394–S1401. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins L.M.D.R.S., Hazra S., Guedes de Silva M.F.C., Pombeiro A.J.L. A sulfonated Schiff base dimethyltin(IV) coordination polymer: Synthesis, characterization and application as a catalyst for ultrasound- or microwave-assisted Baeyer-Villiger oxidation under solvent-free conditions. RSC Adv. 2016;6:78225–78233. doi: 10.1039/C6RA14689A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali M.M., El-Hiti G.A., Yousif E. Photostabilizng efficiency of poly(vinyl chloride) in the presence of organotin(IV) complexes as photostabilizers. Molecules. 2016;21:1151. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghazi D., El-Hiti G.A., Yousif E., Ahmed D.S., Alotaibi M.H. The effect of ultraviolet irradiation on the physicochemical properties of poly(vinyl chloride) films containing organotin(IV) complexes as photostabilizers. Molecules. 2018;23:254. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balakit A.A., Ahmed A., El-Hiti G.A., Smith K., Yousif E. Synthesis of new thiophene derivatives and their use as photostabilizers for rigid poly(vinyl chloride) Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015;2015:510390. doi: 10.1155/2015/510390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabaa M.W., Oraby E.H., Abdel Naby A.S., Mohammed R.R. Anthraquinone derivatives as organic stabilizers for rigid poly(vinyl chloride) against photo-degradation. Eur. Polym. J. 2005;41:2530–2543. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2005.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabaa M.W., Mikhael M.G., Mohamed N.A., Yassin A.A. N-substituted maleimides as thermal stabilizers for rigid poly (vinyl chloride) Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1989;168:23–25. doi: 10.1002/apmc.1989.051680103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaalan N., Laftah N., El-Hiti G.A., Alotaibi M.H., Muslih R., Ahmed D.S., Yousif E. Poly(vinyl Chloride) Photostabilization in the Presence of Schiff Bases Containing a Thiadiazole Moiety. Molecules. 2018;23:913. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yousif E., El-Hiti G.A., Hussain Z., Altaie A. Viscoelastic, spectroscopic and microscopic study of the photo irradiation effect on the stability of PVC in the presence of sulfamethoxazole Schiff’s bases. Polymers. 2015;7:2190–2204. doi: 10.3390/polym7111508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali G.Q., El-Hiti G.A., Tomi I.H.R., Haddad R., Al-Qaisi A.J., Yousif E. Photostability and performance of polystyrene films containing 1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol ring system Schiff bases. Molecules. 2016;21:1699. doi: 10.3390/molecules21121699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousif E., Hasan A., El-Hiti G.A. Spectroscopic, physical and topography of photochemical process of PVC films in the presence of Schiff base metal complexes. Polymers. 2016;8:204. doi: 10.3390/polym8060204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed D.S., El-Hiti G.A., Hameed A.S., Yousif E., Ahmed A. New tetra-Schiff bases as efficient photostabilizers for poly(vinyl chloride) Molecules. 2017;22:1506. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiller M. PVC Additives: Performance, Chemistry, Developments, and Sustainability. Carl Hanser Verlag; Munich, Germany: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folarin O.M., Sadiku E.R. Thermal stabilizers for poly(vinyl chloride): A review. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2011;6:4323–4330. doi: 10.5897/IJPS11.654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng Q., Li C., Pavlinek V., Saha P., Wang H. Surface-modified antibacterial TiO2/Ag+ nanoparticles: Preparation and properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006;252:4154–4160. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang T.-C., Noguchi T., Isshiki M., Wu J.-H. Effect of titanium dioxide particles on the surface morphology and the mechanical properties of PVC composites during QUV accelerated weathering. Polym. Compos. 2016;37:3391–3397. doi: 10.1002/pc.23537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang T.-C., Noguchi T., Isshiki M., Wu J.-H. Effect of titanium dioxide on chemical and molecular changes in PVC sidings during QUV accelerated weathering. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014;104:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sokhandani P., Babaluo A.A., Rezaei M., Shahrezaei M., Hasanzadeh A., Mehmandoust S.G., Mehdizadeh R. Nanocomposites of PVC/TiO2 nanorods: Surface tension and mechanical properties before and after UV exposure. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013;129:3265–3272. doi: 10.1002/app.38989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav M., Kumar S., Tiwari N., Bahadur I., Ebenso E.E. Experimental and quantum chemical studies of synthesized triazine derivatives as an efficient corrosion inhibitor for N80 steel in acidic medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2015;212:151–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Z., Meng Y., Ma X., Zhu H., Li J., Li C., Cao D. Experimental and theoretical studies of benzothiazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in 1M HCl. Corros. Sci. 2016;112:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2016.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y., Li Y., Xu J., Wu D. Incorporating fluorescent dyes into monodisperse melamine-formaldehyde resin microspheres via an organic sol-gel process: A pre-polymer doping strategy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2:5837–5846. doi: 10.1039/C4TB00942H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alotaibi M.H., El-Hiti G.A., Hashim H., Hameed A.S., Ahmed D.S., Yousif E. SEM analysis of the tunable honeycomb structure of irradiated poly(vinyl chloride) films doped with polyphosphate. Heliyon. 2018;4:e01013. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashim H., El-Hiti G.A., Alotaibi M.H., Ahmed D.S., Yousif E. Fabrication of ordered honeycomb porous poly(vinyl chloride) thin film doped with a Schiff base and nickel(II) chloride. Heliyon. 2018;4:e00743. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yousif E., Ahmed D.S., El-Hiti G.A., Alotaibi M.H., Hashim H., Hameed A.S., Ahmed A. Fabrication of novel ball-like polystyrene films containing Schiff bases microspheres as photostabilizers. Polymers. 2018;10:1185. doi: 10.3390/polym10111185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith K., Balakit A.A., El-Hiti G.A. Synthesis and characterization of a new photochromic alkylene sulfide derivative. J. Sulfur Chem. 2018;39:182–192. doi: 10.1080/17415993.2017.1413651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed D.S., El-Hiti G.A., Yousif E., Hameed A.S., Abdalla M. New eco-friendly phosphorus organic polymers as gas storage media. Polymers. 2017;9:336. doi: 10.3390/polym9080336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altaee N., El-Hiti G.A., Fahdil A., Sudesh K., Yousif E. Screening and evaluation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) with Rhodococcus. equi using different carbon sources. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017;42:2371–2379. doi: 10.1007/s13369-016-2327-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altaee N., El-Hiti G.A., Fahdil A., Sudesh K., Yousif E. Biodegradation of different formulations of polyhydroxybutyrate films in soil. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:762. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2480-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yousif E., El-Hiti G.A., Haddad R., Balakit A.A. Photochemical stability and photostabilizing efficiency of poly(methyl methacrylate) based on 2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl) propanoate metal ion complexes. Polymers. 2015;7:1005–1019. doi: 10.3390/polym7061005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaya I., Yildirim M. Synthesis and characterization of graft copolymers of melamine: Thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and optical properties. Synth. Met. 2009;159:1572–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardette J.L., Gaumet S., Lemaire J. Photooxidation of poly(viny1 chloride). 1. A reexamination of the mechanism. Macromolecules. 1989;22:2576–2581. doi: 10.1021/ma00196a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaumet S., Gardette J.-L. Photo-oxidation of poly(vinyl chloride): Part 2—A comparative study of the carbonylated products in photo-chemical and thermal oxidations. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1991;33:17–34. doi: 10.1016/0141-3910(91)90027-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott G. Mechanism of Polymer Degradation and Stabilization. Elsevier; New York, NY, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pospíšil J., Nešpurek S. Photostabilization of coatings. Mechanisms and performance. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000;25:1261–1335. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6700(00)00029-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shyichuk A.V., White J.R. Analysis of chain-scission and crosslinking rates on the photooxidation of polystyrene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000;77:3015–3023. doi: 10.1002/1097-4628(20000923)77:13<3015::AID-APP28>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasha M. Characterization of electronic transitions in complex molecules. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1950;9:14–19. doi: 10.1039/df9500900014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jafari A.J., Donaldson J.D. Determination of HCl and VOC emission from thermal degradation of PVC in the absence and presence of copper, copper(II) oxide and copper(II) chloride. J. Chem. 2009;6:685–692. doi: 10.1155/2009/753835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torikai A., Hasegawa H. Accelerated photodegradation of poly(vinyl chloride) Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999;63:441–445. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(98)00125-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pepperl G. Molecular weight distribution of commercial PVC. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2000;6:88–92. doi: 10.1002/vnl.10229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skillicorn D.E., Perkins G.G.A., Slark A., Dawkins J.V. Molecular weight and solution viscosity characterization of PVC. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 1993;15:105–108. doi: 10.1002/vnl.730150211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mark J.E. Physical Properties of Polymers Handbook. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jellinek H.H.G. Aspects of Degradation and Stabilization of Polymers. Elsevier; New York, NY, USA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mori F., Koyama M., Oki Y. Studies on photodegradation of poly(vinyl chloride) (part 1) Macromol. Mater. Eng. 1977;64:89–99. doi: 10.1002/apmc.1977.050640108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kayyarapu B., Kumar M.Y., Mohommad H.B., Neeruganti G.O., Chekuri R. Structural, thermal and optical properties of pure and Mn2+ doped poly(vinyl chloride) films. Mater. Res. 2016;19:1167–1175. doi: 10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2016-0239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devi M.R., Saranya A., Pandiarajan J., Dharmaraja J., Prithivikumaran N., Jeyakumaran N. Fabrication, spectral characterization, XRD and SEM studies on some organic acids doped polyaniline thin films on glass substrate. JKSUS. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2018.02.008. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi W., Zhang J., Shi X.-M., Jiang G.-D. Different photodegradation processes of PVC with different average degrees of polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008;107:528–540. doi: 10.1002/app.25389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z.M., Wagner J., Ghosal S., Bedi G., Wall S. SEM/EDS and optical microscopy analyses of microplastics in ocean trawl and fish guts. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;603–604:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.See C.H., O’Haver J. Atomic force microscopy characterization of ultrathin polystyrene films formed by admicellar polymerization on silica disks. Appl. Polym. 2003;89:36–46. doi: 10.1002/app.12092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]