Abstract

Background

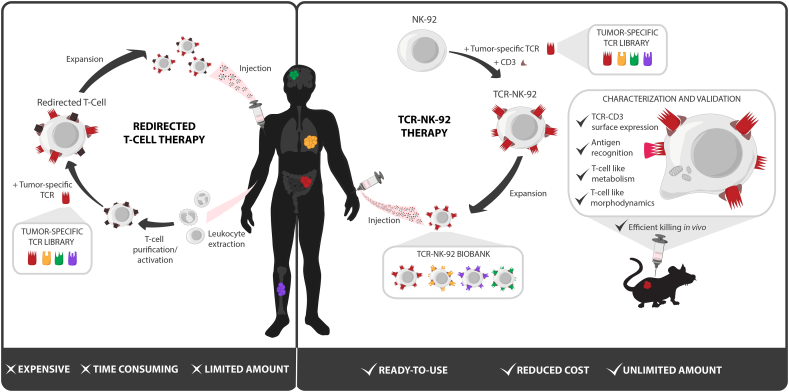

Adoptive T-cell transfer of therapeutic TCR holds great promise to specifically kill cancer cells, but relies on modifying the patient's own T cells ex vivo before injection. The manufacturing of T cells in a tailor-made setting is a long and expensive process which could be resolved by the use of universal cells. Currently, only the Natural Killer (NK) cell line NK-92 is FDA approved for universal use. In order to expand their recognition ability, they were equipped with Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs). However, unlike CARs, T-cell receptors (TCRs) can recognize all cellular proteins, which expand NK-92 recognition to the whole proteome.

Methods

We herein genetically engineered NK-92 to express the CD3 signaling complex, and showed that it rendered them able to express a functional TCR. Functional assays and in vivo efficacy were used to validate these cells.

Findings

This is the first demonstration that a non-T cell can exploit TCRs. This TCR-redirected cell line, termed TCR-NK-92, mimicked primary T cells phenotypically, metabolically and functionally, but retained its NK cell effector functions. Our results demonstrate a unique manner to indefinitely produce TCR-redirected lymphocytes at lower cost and with similar therapeutic efficacy as redirected T cells.

Interpretation

These results suggest that an NK cell line could be the basis for an off-the-shelf TCR-based cancer immunotherapy solution.

Fund

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (#254817), South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (#14/00500-79), by OUS-Radiumhospitalet (Gene Therapy program) and the department of Oncology at the University of Lausanne.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, TCR, T cell, Natural killer

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Redirection of NK cells for clinical use in cancer therapy has been suggested for almost 20 years. Indeed non-modified NK cells were not as potent as T cells in detecting targets and mounting an immune response. The use of artificial receptors such as Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) is now tested in the clinic and demonstrates that with improved targeting, NK cells can become attractive for such treatment.

Added value of this study

TCR, a natural antigen receptor, can potentially recognize any protein and therefore represents a receptor which could redirect cells against any tumor. Although T- and NK cells seem to originate from the same ancestor cell, alpha/beta T-cell receptor expression seems to be truly restricted to T cells. This is probably due to the lack of a complete set of CD3 subunits in NK cells. We here show that the “simple” addition of the CD3 complex can turn the NK cell line into a T cell. In addition, this makes it possible to redirect NK cells against any target.

Implication of all the available evidence

Our results not only complete the previous studies enhancing NK-92 (and NK cells) but also provide evidence about the distance between T- and NK-cell lineages. These data will most probably pave the way to the development of less expensive TCR-based cell therapy.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Adoptive transfer of antigen receptor-redirected T cells has shown great therapeutic potential in cancer treatment and achieved remarkable remissions in advanced cancers [1,2]. Due to the risk of rejection of allogeneic cells, current adoptive cell therapy approaches mostly rely on the administration of engineered autologous T cells [3,4]. Reaching significant numbers of therapeutic redirected patient T cells is challenging both in terms of logistics and costs independently of the improvements of ex vivo activation and expansion protocols [5]. To overcome these manufacturing challenges, the applicability of unrestricted sources of antitumor effector cells has been explored and is currently receiving increasing attention [[6], [7], [8]]. Indeed, cell lines represent a continuous and unlimited source of effector cells. The FDA approved Natural Killer (NK)-92 cell line represents a model of universal cells: it was isolated from a lymphoma patient, established [9] and has been used in the clinic for at least two decades [7,10]. Earlier data from phase I clinical trials have shown safety of infusing irradiated NK-92 cells into patients with advanced cancer [11,12].

Although NK cells have an inherent capacity to recognize cancer cells regulated by a balance between activating and inhibitory signals, they have limited targeting competence. NK-92 were genetically improved to express receptors such as Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) [13,14] or CD16 [15,16]. In both cases the technology relied on antibodies, thus, the tumor detection was restricted to surface antigens. Specific target antigens represent a bottleneck in CAR-based adoptive transfer, especially for solid tumors treatment. Unlike antibodies which directly bind to their targets, T-cell Receptors (TCRs) recognize an antigenic peptide from degraded protein presented in the context of a Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecule. Thus TCRs can potentially recognize the proteome without restriction to subcellular localization.

We here asked if a therapeutic NK cell line could accommodate TCR expression, keeping in mind that a TCR molecule requires a battery of signaling components to be correctly expressed at the plasma membrane and to signal upon peptide-MHC (pMHC) binding [17]. We partially reconstituted a TCR friendly environment by expressing the CD3 complex, which is necessary for proper TCR targeting to the plasma membrane and selected a derivative of NK-92 named TCR-NK-92. Gene expression analysis demonstrated that TCR-NK-92 had acquired a T cell-like profile. We further observed that TCR-NK-92, unlike the original NK-92, could express TCRs and that these TCRs were functional and could trigger pMHC-specific cytotoxic functions. Considering the limitless propagation of these cells, the potential TCR-recognition of all cellular proteins and the possibility of creating TCR-NK-92 biobanks, we propose the use of these cells for TCR-based cancer immunotherapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human material were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and the regional ethical committee (REC). Healthy donor T cells were obtained from buffy coats from the Blood bank under informed consent.

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the institution rules and Norwegian Food Safety Authority approval, mice were bred and kept in-house under approved animal care protocols.

2.2. Cell lines, media and peptides

T cells were isolated from the blood of healthy donors. NK-92 cells (human natural killer cell line) were obtained from ATCC and maintained in X-vivo 10 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated human serum (Trina Bioreactives AG, Nänikon, Switzerland) and 500 IU/mL rhIL-2 (Novartis, Emeryville, CA, USA). K562 cells (erythroleukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)) were obtained from ATCC. K562:HLA-A2 and K562:HLA-A2-GFP were created through retroviral transfection of an HLA-A2 (Addgene #108214) or an HLA-A2-GFP (Addgene plasmid #85162) construct [18] and sorted to purity. Jurkat 76 (J76) were kind gifts from M. Heemskerk (Leiden University Medical Center, The Nederland), Jurkats (J6) and HCT116 (epithelial colon colorectal carcinoma) were from ATCC; Granta-519 (mantle B cell lymphoma) were from our collection and ESTAB039 (melanoma cells) were kindly provided by Graham Pawelec (University of Tuebingen, Germany). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FCS (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) and gentamycin 0.05 mg/mL (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Target cells used in the BLI killing assay, in vivo experiments or in microspheroid assays were transduced with a retrovirus encoding a luciferase-GFP fusion transgene [19]. They were sorted for GFP positivity and maintained as a pure line.

The TGFβRII frameshift peptide131–139(RLSSCVPVA) and peptide127–145 (KSLVRLSSCVPVALMSAMT) and the Melan-A peptide26–35(EAAGIGILTV) were manufactured by ProImmune Ltd. (Oxford, UK). Melan-A:HLA-A2 dextramer was from Immudex (Copenhagen, Denmark).

2.3. DNA constructs, retroviral transduction, generation of TCR-NK-92 cells

The human polycistronic CD3 complex (hCD3) was designed as described in [20], briefly the human coding sequence of the four different components of the CD3 signaling complex CD3ζ, CD3ε, CD3δ, CD3γ (UniProt: P20963, P07766, P04234 and P09693, respectively) were fused via picornavirus 2A coding sequences as depicted in Supplementary Fig.1. A codon optimized synthetic DNA fragment was ordered (Eurofins, Germany) and subcloned into pMP71 retroviral vector using our Gateway compatible strategy [21].

TCR expression constructs, Radium-1 and DMF-5, were prepared as previously described [21,22].

The Luciferase-GFP construct was a kind gift R. Löw (Eufets, Germany) [23], the coding sequence was verified and subcloned into pMP71.

Viral particles were produced as described in [21] and used to transduce cells, either NK-92 (hCD3_2A and TCR) or cell lines (Luciferase-GFP, HLA-A2). Spinoculation was performed with 1 Volume of retroviral supernatant in a 12-well or a 24-well culture non-treated plate (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) pre-coated with 50 μg/mL retronectin (Takara Bio. Inc., Shiga, Japan). NK-92 cells were spinoculated twice whereas other cell lines only once. Cells were then harvested and grown in their medium. Transduction efficiency was checked after 3 to 7 days by flow cytometry and cells were expanded for future experiments. TCR-NK-92 cells were generated in two-steps; first, NK-92 were changed to CD3-NK-92 by transduction with hCD3_2A construct and efficiency was monitored by electroporation with an mRNA encoding for a TCR which triggers a transient CD3 expression at the surface. The CD3-NK-92 cell line was sorted on the basis of CD3 expression, amplified and stocked for further use. For TCR expression, CD3-NK-92 were spinoculated twice with retroviral particles encoding for selected TCR and sorted for stable CD3 expression. Pure cells were amplified and stocked until further use.

2.4. RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from three biological replicates for each cell line, NK-92, CD3-NK-92 and TCR-NK-92, using miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen©) and the RNA integrity was investigated with the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA). Sequencing libraries were generated using TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) and 500 ng high quality total RNA (RIN > 8.0) was processed according to manufacturer's instructions. The resulting libraries were sequenced 75 bp single read on the NextSeq500 system (chemistry v2; Illumina Inc., CA, USA).

For differential gene expression analysis sequencing data were first aligned against human reference (UCSC hg19) using STAR v2.5.0 and expression levels and differential gene expression were assessed with cufflinks/cuffdiff v2.2.1. Further, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tool (IPA®, Qiagen©) was used to investigate possible biological downstream effects of differential expressed genes.

2.5. TCR-ligand dissociation kinetic measurements by 2-color NTAmers technology

NTAmers were synthetized and used as described [24]. Shortly, TCR-NK-92 or T cells were incubated for 40 min at 4 °C with reversible Melan-A:HLA-A2 specific NTAmers made of streptavidin-PE scaffolds and Cy5-labeled monomers. After washing, 0.25 millions cells were suspended in 250 mL 4 °C FACS buffer and baseline geometric mean fluorescence was measured on a SORP-LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for 30 s with constant temperature control at 4 °C. After baseline measurement, imidazole (100 mmol/L final concentration) was added to elicit the decay of the NTAmer scaffold, enabling direct visualization of the Cy5-pMHC monomeric dissociation from the TCR through time. Flow-cytometric-based data were processed using the kinetic module of FlowJo software v.9.6 (TreeStar Inc., Ahsland, OR, USA) as described in ref. 16. Normalized (Cy5) gMFI values for each cell types were plotted against time (s) using the GraphPad Prism v.6 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Monomeric dissociation rates best fitted a one-phase exponential decay equation, from which koff and half-lives could be determined.

2.6. Metabolic analysis

A Seahorse Extracellular Flux (XF96e) Analyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to measure the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) which relates to mitochondrial respiration and the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) that reflects the cellular glycolytic activity of live lymphocytes cells. Briefly, prior to the assay, NK-92, CD3-NK-92, TCR-NK-92, J6, J76 and J Radium-1 cells were attached onto Cell-Tak (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, US), with or without anti-CD3 (OKT3) (eBiosciences, Thermo Fisher Scientific), coated 96-well XF-PS plates (Agilent, CA, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific) XF unbuffered assay media, supplemented with 2 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich, Norway), 10 mM glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific), adjusted to physiological pH (7.6) and incubated in the absence of CO2 for one hour prior to seahorse measurements (7 replicates per experiment). Initially, the cell basal respiration was measured for all groups. Next, oligomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), a potent F1F0 ATPase inhibitor (1 μM), was added and the resulting OCR was used to derive ATP production by respiration (by subtracting the oligomycin-linked OCR rate from the baseline cellular OCR). Then, 1 μM of carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazon (FCCP) (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected to uncouple the mitochondrial electron transport from ATP synthesis, thus allowing the electron transport chain (ECT) to function at its maximal rate. The maximal respiration capacity was derived from each group by subtracting non-mitochondrial respiration from the FCCP measurement. Lastly, a mixture of antimycin A (Sigma-Aldrich) and rotenone (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, at 1 μM, to completely inhibit the electron transport and hence respiration, revealing the non-mitochondrial respiration. The basal glycolytic rates were also measured as ECAR before and after injection of oligomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Upon addition of oligomycin the cells switched to their highest glycolytic capacity to compensate for ATP requirements.

2.7. Reflection interference contrast microscopy (RICM) and total interference reflection fluorescence (TIRF)

Anti HLA class I and CD3 (OKT3) antibodies (eBiosciences) were adsorbed directly on glass slides, previously washed with piranha acidic solution (70% of 96% pure sulphuric acid (Sigma Aldrich) with 30% of 25% pure hydrogen peroxide (Sigma Aldrich)), for 30 min at room temperature, then washed extensively with miliQ water. TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, CD3-NK-92, NK-92 and T cells from PBMC were washed twice and resuspended at 0.6 × 106 cells/mL in PBS 0.1% BSA and incubated on the glass slides for 20 min under controlled atmosphere (37 °C and 5% CO2). To trigger the formation of immune synapse, prior to incubation on coated glass slides, cells were marked with 2 μg/mL of FITC Anti Vβ3 during 15 min. Cells were then fixed using 4% PFA solution (Sigma Aldrich) for 15 min and then permeabilized in 0.05% Triton X-100 solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. Actin and CD3 molecules were stained with 5 μM of Alexa488 Phalloidin (Life Technologies, Norway) and 2 μM of Atto647 conjugated anti-CD3 antibody (home-made conjugation, clone UCHT1), respectively, for 30 min. Cells were imaged using Total Internal Reflection Microscopy (TIRFM) and Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM) using an inverted microscope (AxioObserver, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany), equipped with an EM-CCD camera (iXon, Andor, Belfast, North-Ireland). Immune synapse was imaged on a Zeiss 880 LSM microscope using a GaAsP PMT. Acquisitions were performed using ZEN blue or black software. TIRF and RICM images were taken with a custom 100 × 1.46 NA oil apochromatantiflex objective (Zeiss) or a 63× axioplan 1.4 NA oil objective (for the LSM). Analysis was performed using home-made programs in Fiji software software as described in [25]. Briefly, in RICM, the region of the cell that resides in the vicinity of the substrate and in particular its contour, exhibits a high spatial intensity variance that permits an easy segmentation from the background, which exhibits low variance, permitting thus to calculate the spreading area. Actin centrality was measured as the ratio of the fluorescence in a central disk of 1/5 the cell radius divided by the total fluorescence under the cell.

2.8. CyTOF

Six million effector cells (T cell, NK-92, TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92) were incubated with Granta-519 cells, loaded with TGFβRII peptide127–145, at 1:2 effector: target ratio for 24 h prior CyTOF experiment. Briefly, cells were resuspended in Maxpar Cell Staining buffer (Fluidigm, san Francisco, CA, USA) in the presence of 1× cisplatin (Fluidigm) and incubated for 5 min at RT. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Fc-receptor blocking solution (aggregation of G-globulin) for 10 min and then incubated with the antibody mix, CCR6, CCR7, CD127, CD137, CD14, CD161, CD16, CD19, CD25, CD279 (PD1), CD28, CD3, CD33, CD38, CD4, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD56, CD8, CTLA-4, CXCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5, HLA-DR, ICOS, LAG3, NKG2D, PD-L1, PD-L2, TIGIT, TIM3 (Fluidigm) for 30 min at RT. Samples were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% of PFA and permeabilized with methanol for 1 h. After two washes in PBS, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1× intercalator (Ir) (Fluidigm) and incubated for 20 min at RT. Following one wash in PBS cells were pelleted until ready to run in CytOF. Prior to sample acquisition cells were resuspended in water with 10% of calibration beads and filtered before being injected into the CyTOF 2 machine (Fluidigm). Analysis was performed using CytobankCytomass (http:// www.Cytobank.org). Typical gating strategy was applied as follow: 1. EQ-140 vs EQ-120 to exclude calibration beads. 2. Event length vs Ir-191 to gate singlets. 3. Cisplatin vs CD458-89Y to gate live cells.4. Event length vs CD19 to exclude CD19+ cells (Granta-519). Gated events were then run using viSNE algorithm with the following parameters: 1000 iterations, 30 perplexity, 0.5 theta.

2.9. In vitro cytokine release

TCR-NK-92 and CD3-NK-92 were co-cultured for 24 h with antigen presenting cells (APCs) loaded with either the cognate peptide or an irrelevant peptide, at an effector cell to target cell ratio of 1:2. Culture supernatant was harvested and the cytokine release was measured using the BioplexPro™ Human Cytokine 17-plex Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, US) according to manufacturer's instructions. The analysis was performed on the Bio-Plex 200 system instrument from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

2.10. In vitro degranulation assay and phenotype by flow cytometry based technology

TCR-NK-92 cells were stimulated for 5 h with antigen presenting cells (APCs), loaded or not with the indicated peptide at 10 μM final concentration, at an effector cell to target cell ratio of 1:2, in the presence of BD GolgiPlug and BD Golgistop (BD Biosciences) at a 1/1000 dilution. Cells were then washed extensively and surface stained for flow cytometric analysis (see below) using specific antibodies. Antibodies specific for CD3 (OKT-3), CD56 (TULY56), CD16 (eBioCB16), NKp30 (AF29-4D12), NKp44 (44.189), NKp46 (9E2), NKG2D (1D11), CD226 (DX11), CD137 (4-B41), CD96 (TACTILE) (NK92.39), CD94 (DX22) and TIGIT VSTM3 (A15153G) were used to profile the effector receptors. Anti CD107a (H4A3) antibody was used as measurement of degranulation functions. Anti Vβ3 (CH92) antibody (Beckman Coulter) was used to monitor the expression of the therapeutic TCR (Radium-1) and Melan-A:HLA-A2 dextramer (Immudex) for monitoring DMF-5 TCR. For surface staining single-cell suspensions were stained with the appropriate monoclonal antibodies for 15 min at RT in the dark in PBS containing 2% FCS.

Cells were acquired on FACS Canto II, LSR II (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.). FACS Aria (BD Biosciences) and Sony SH800 Cell (Sony Biotechnology Inc.,San Jose, CA, US) were used for cell sorting.

2.11. TCR signaling and phospo-specific flow cytometry

TCR activation was performed essentially as previously reported [26]. In brief, APCs loaded with peptide at 10 μM final concentration (relevant or irrelevant) were used to activate the TCR. APCs and TCR-NK-92 were mixed at 1:1 ratio. TCR activation was stopped at different time points, 2, 5 and 15 min, followed by PFA fixation, permeabilization, barcoding and antibody staining.

Antibody staining: p-CD3zeta, p-SLP76, p-Zap70 were all from BD Biosciences, whereas p-ERK was from Cell Signaling Technologies (Leiden, The Nedherlands). Stained samples were collected on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using Cytobank Software (http://www.Cytobank.org), and phosphorylation levels were calculated relative to unstimulated T cells, using arcsinh transformed data.

2.12. In vitro killing assay

An Annexin V assay was performed using an Incucyte S3 (Essen BioScience, UK). Granta-519 were loaded or not with 10 μM of TGFβRII frameshift peptide127–145 (KSLVRLSSCVPVALMSAMT), washed and resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium with 1:400 Annexin V red (Essen BioScience, UK). Then cells were incubated in a 96-well plate coated with Cell-Tak (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, US) for 15 min at a density of 5000 cells per well. NK-92, CD3-NK-92 and TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells were then added at a density of 20,000 cells per well. Two images per well were taken, each hour, using phase and red channel. Analysis was performed using Incucyte software. Killing was monitored by following the density of red object/mm2 over time.

Non-radioactive Europium TDA (EuTDA) cytotoxicity assay based on DELFIA technology was performed. The EuTDA assay uses time-resolved fluorometry (TRF) and the measured fluorescence signal correlates directly with the amount of lysed cells (PerkinElmer Inc., Boston, MA, USA). TCR-NK-92 cells (Radium-1 and DMF-5) were stimulated for 2 h with target cells (K562:HLA-A2) loaded with 10 μM of either the relevant or irrelevant peptide and incubated at the indicated effector to target ratio (E:T), 25:1 and 50:1. Measurement of the fluorescent signal was performed on a VICTOR X4™ plate reader (PerkinElmer Inc).

2.13. Spheroids

Spheroids were obtained as in [27]: at day 8, 3 × 106 of either TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 or NK-92, or medium were added to the spheroid cultures along with 10 μM of cognate peptide. Medium only cultures were used as control. Size of the spheroids was monitored using an Evosxl Core microscope and analyzed using Fiji and Wavemetrics.

2.14. In vivo studies

Two xenograft mouse models were implemented, respectively sub-cutaneous and intraperitoneal. NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl /SzJ (NSG) mice were injected with 1 × 106 luciferase expressing HCT116. Eight injections of 5 × 106 TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 and TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells were performed in the tumor (i.t.) or at the same site at days 3, 6, 10, 12, 14, 17, 20 and 25 post tumor cell injections. Size of the tumor was monitored twice a week using a caliper and mice were sacrificed once the tumor volume reached 2000 cm3.

2.15. Statistics

Unless stated otherwise, statistics were performed using heteroscedastic two tails t-Student or Anova using R software. Kaplan-Meier estimator was compared using log-rank test (Mantel-Haenszel test). For all statistical test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. TCR-NK-92 express a functional TCR and are cytotoxic effector cells

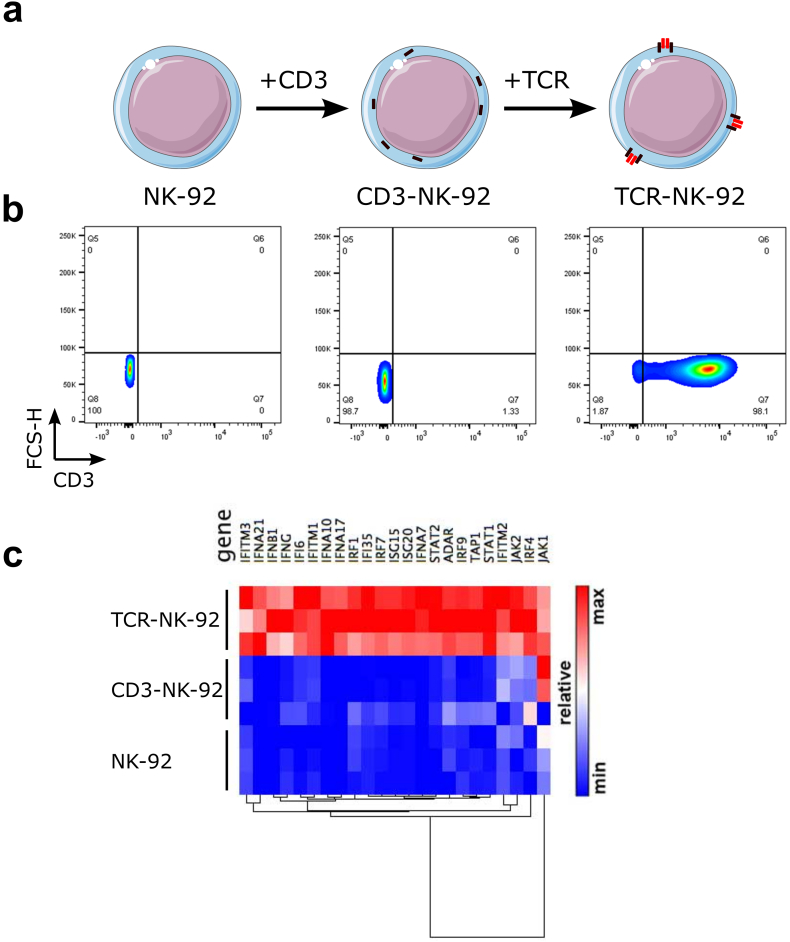

The manufacture of TCR-NK-92 cells was performed in two steps (Fig. 1a). First, a construct encoding the human CD3 complex (hCD3) gene was designed as a polycistronic single chain in which CD3γ, δ, ε, ζ coding sequences were linked by 2A ribosome skipping sequences and its expression in primary human T cells was compared with a murine CD3 construct. CD3zeta was detected at the plasma membrane, suggesting that the entire complex was formed (Fig. 1Sa,b). In contrast, retrovirally transduced NK-92 cells with hCD3 (CD3-NK-92) did not show surface expression of CD3 unless they were co-transduced with TCR (Fig. 1b). Two therapeutic TCRs were selected, Radium-1 TCR specific for a TGFβRII frameshift mutation peptide (amino acids131–139, pTGFβRII) [22] and the DMF-5 Melan-A specific TCR (amino acids27–35, pMelan-A) [28]. The double-transduced CD3/TCR NK-92 cells, referred to as TCR-NK-92, demonstrated similar surface expression levels of CD3 (Fig. 1a,b and Fig. 1Sc).

Fig. 1.

Generation of a universal T cell-like lymphocyte for TCR expression.

(a) Schematic overview of engineered TCR-NK-92 cells. NK-92 cells were retrovirally transduced with the human CD3 polycistronic complex, CD3εγ, CD3εδ, and CD3ζζ dimers. CD3 engineered NK-92 cells were herein referred to as CD3-NK-92. The CD3 complex is localized in the intracellular compartment. CD3-NK-92 were then super-infected with a TCRα-2A-TCRβ construct encoding a therapeutic TCR and referred to as TCR-NK-92. The CD3-TCR complex is translocated on the cell surface. (b) Dot plots showing surface expression of CD3 in TCR-NK-92 (Radium-1 or DMF-5), CD3-NK-92 and parental NK-92 (representative of three experiments). (c) Heatmap showing the relative expression of a relevant subset of genes belonging to the Interferon-signaling pathway for three replicates of TCR-NK-92, CD3-NK-92 and NK-92 in a pair-wise distance based on RNA sequencing.

To assess whether CD3/TCR gene editing of NK-92 could affect cellular functions we analyzed the gene expression of parental NK-92 and monitored changes in gene expression in both TCR-NK-92 and CD3-NK-92 (Fig. 1c). Surprisingly, pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes using IPA® (Qiagen) revealed the interferon-signaling pathway as the most activated (p-value: 6.9E-17; z-score: 3.9) in TCR-NK-92 cells; caused by up-regulation of a significant number of genes involved in the interferon-signaling cascade. In contrast, transfection of NK-92 with hCD3 not followed by TCR (CD3-NK-92) did not affect the expression of any of these genes in terms of mRNA transcription when compared to parental NK-92 (data not shown and Fig. 1Sd). Three interferon forms, alpha, beta and gamma, seemed to be significantly up-regulated. These findings indicate that TCR-NK-92 showed a novel gene expression pattern that resembles those of primary effector T and NK cells [29].

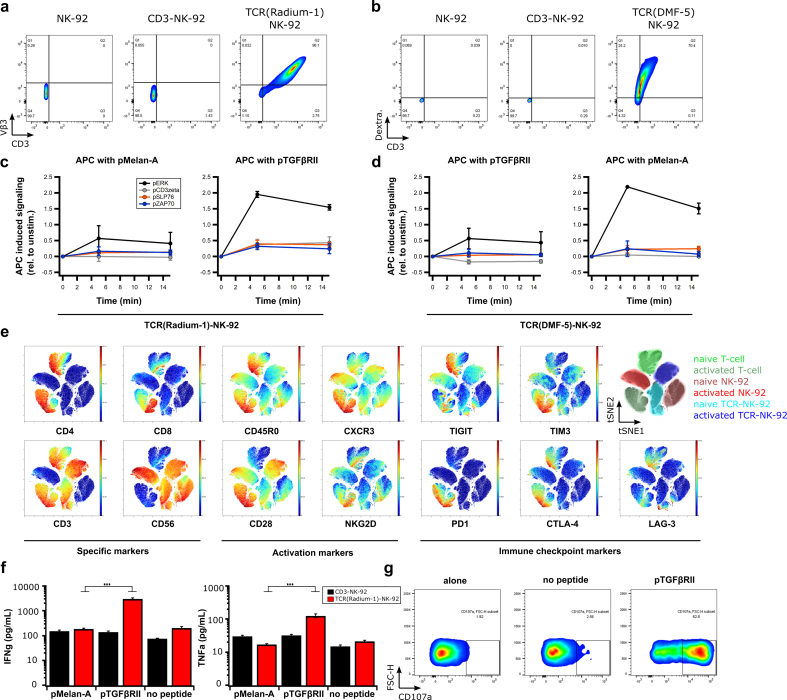

We next studied the protein quality of the transgenic TCR. To confirm correct folding of the TCR, we used a specific anti-TCR Vβ chain antibody (anti-Vβ3) in TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells or pMHC multimer (Melan-A:HLA-A2 dextramer) in TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 cells, respectively (Fig. 2a,b). To investigate if the binding capacity of the transgenic TCR for its cognate pMHC complex was conserved in TCR-NK-92 cells, 2-color NTAmer technology was applied. This enables measurements of monomeric TCR-pMHC dissociation rates (koff) and half-lives (t1/2) directly at the surface of living cells [24]. This confirmed that TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 cells had TCR-pMHC dissociation kinetic parameters similar to Jurkat and primary T cells carrying DMF-5 (Fig. 2Sa,b). Knowing that the extracellular part of the TCR was functionally expressed in TCR-NK-92, we next analyzed TCR signaling using phospho-flow cytometry [26]. Non-specific activation of TCR using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies induced strong phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules including CD3ζ, Zap70 and SLP76 in TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells, suggesting that the key players of the TCR signaling cascade were present and active in TCR-NK-92 (Fig. 2Sc). In a more physiological setting by minute co-culturing of TCR-NK-92 cells with peptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells (APCs), we observed pMHC-induced phosphorylation in TCR-NK-92 cells only when the specific peptide was presented (Fig. 2c,d and Fig. 2Sd).

Fig. 2.

TCR-NK-92 in vitro validation.

(a,b) Dot plots showing correct folding of two transgenic TCRs (Radium-1 TCR and DMF-5 TCR). Surface expression of aCD3 and aVb3 TCR antibodies in NK-92, CD3-NK-92 and TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 (left panel) and expression of aCD3 antibody and pMHC dextramer in NK-92, CD3-NK-92 and TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 (right panel) (representative of three experiments). (c,d) Phosphorylation of the key components of TCR signaling cascade, ERK, CD3zeta, SLP76 and ZAP70 overtime in TCR-NK-92 (either DMF-5 TCR or Radium-1 TCR) was detected by phospho-specific flow cytometry upon stimulation with APCs loaded with either pMelan-A or pTGFβRII peptide. TCR-induced phosphorylation was measured at 5, 15 min after addition of APCs to TCR-NK-92 cells, following a 30 s centrifugation to bring the cells together. (n = 2) Error bars represent SD. (e) Outcome of ViSNE analysis on TCR-NK-92, NK-92 and T cells, either naïve or activated. (f) Bar graphs showing the level of IFNγ and TNFα produced by TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 and CD3-NK-92 co-cultured with K562:HLA-A2 that were loaded with either irrelevant peptide (pMelan-A) or cognate peptide (pTGFβRII) or used as negative control (no peptide). (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM. (g) Dot plots showing frequency of activated TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells. Detection of CD107a expression in TCR-NK-92 cells cultured in the presence of cognate peptide (pTGFβRII). (n = 4). Error bars represent SEM.

Effector functions are also dependent on the signaling from other regulatory receptors. To study the influence of the presence of CD3 and TCR in TCR-NK-92 cells, cells were phenotypically profiled and compared with NK-92 and primary T cells from peripheral blood. We observed that among the activating NK receptors, TCR-NK-92 cells only showed modest levels of NKp30 (CD337), while NKp44 (CD336), NKp46 (CD335) and NKG2D were not detectable (Fig. 3Sa). Of interest, expression of these activating receptors was higher in parental NK-92. Further, the co-stimulatory receptors CD226 and CD137 were not detectable in TCR-NK-92, or in NK-92. This contrasted with the inhibitory receptor CD96, which was always detected at high levels on both TCR-NK-92 and NK-92 (Fig. 3Sa). To investigate how the activation is differently impacting T cells, NK-92 and TCR-NK-92, we compiled a panel of 35 lymphocyte-specific markers for mass cytometry. We observed that TCR-NK-92 had an intermediate behavior between NK-92 and T cells; like T cells, TCR-NK-92 showed high level of CD28, but like NK-92, they expressed fewer immune checkpoint proteins (PD1, CTLA-4, TIGIT, TIM3 and LAG-3) in comparison with T-cells after a short activation (Fig. 2e, and Fig. 3Sb). This last result holds promise for TCR-NK-92 by combining the specificity and efficiency of the T cell with an anticipated lower sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibition.

NK-92 cells, like NK cells, kill in an antigen-independent manner. We and others previously showed that CAR provided antigen specificity to NK cells while maintaining inherent NK-cell functions [[30], [31], [32]]. In order to validate the functionality of the introduced TCR, we analyzed the effector functions including cytokine release and degranulation of TCR-NK-92 cells upon co-stimulation with target cells loaded with either the cognate peptide or an irrelevant peptide. This demonstrated that TCR-NK-92 produced IFNγ and TNFα in an antigen-specific manner (Fig. 2f). As expected, CD3-NK-92 cells did not show any antigen-specific cytokine release. Degranulation was measured by CD107a detection, which gives an indirect measurement of cytotoxicity [33]. The majority of TCR-NK-92 cells stained positively for CD107a only in the presence of the cognate antigen, demonstrating that degranulation was antigen specific and thus TCR dependent (Fig. 2g). In general, secretion of IFNγ and mobilization of CD107a correlate with the ability of the effector cells to lyse target cells. Collectively, the results demonstrate functional TCR can be expressed in manipulated NK cells.

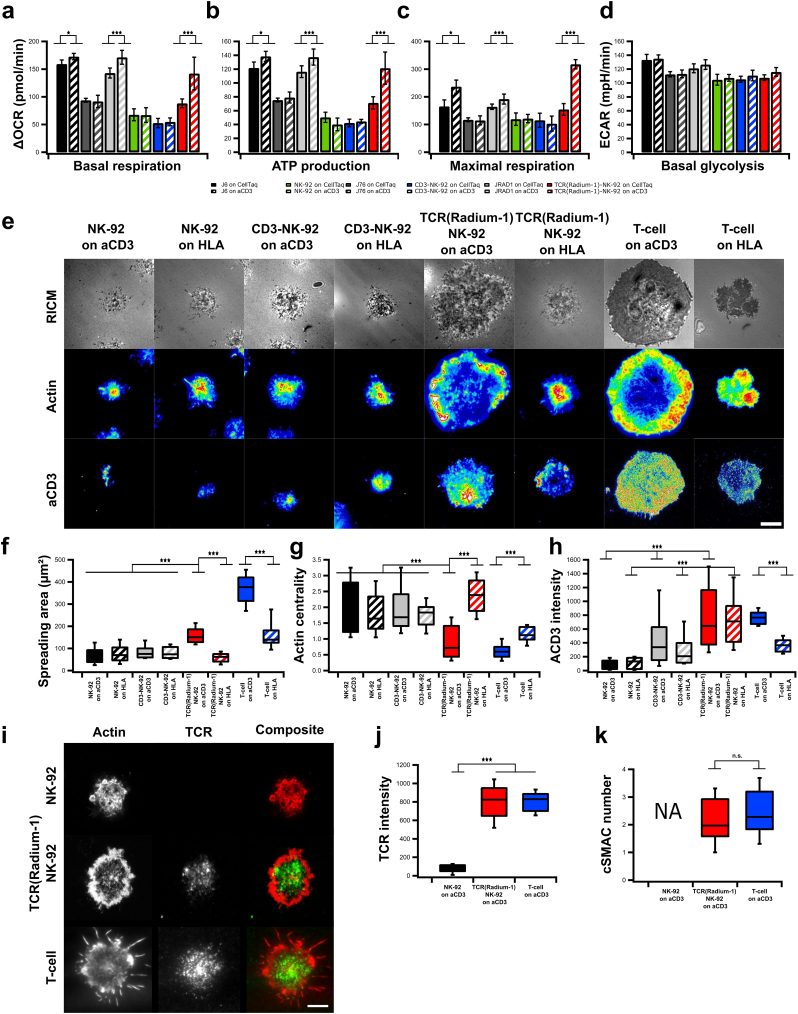

3.2. TCR-NK-92 show T cell-related metabolic and phenotypic profile

As metabolism and plasma membrane organization are critical features in effector cell functions, we studied the metabolic activities of TCR-NK-92 cells using SeaHorse technology. Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) as well as Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) were measured over time and modulated by metabolic drugs in order to extract parameters of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis in NK-92, CD3-NK-92, TCR-NK-92, J6, J76 and J76-TCR cells. TCR-NK-92 and T cells demonstrated a similar pattern in terms of basal respiration, as well as ATP production and maximal respiration capacity in the presence of anti-CD3 coated surface (Fig. 3a-c, Fig. 4Sa). This demonstrates the ability of the TCR-NK-92 to increase their oxidative metabolism in response to external activation stimuli, comparable to T cells. Furthermore, ECAR and basal glycolysis measurements showed comparable glycolysis activity for all cell lines independently of the presence of anti-CD3 (Fig. 3d and Fig. 4Sb-d).

Fig. 3.

TCR-NK-92 acquire T-cell like behaviors in terms of metabolic functions, morphodynamics and immune synapse.

(a-c) Mitochondrial respiration. Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) of NK-92, CD3-NK-92, TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, J6, J76 and J Radium-1 over time, in the presence or not of anti-CD3 (aCD3). Mitochondrial respiration function (expressed as OCR rate) was measured, first at baseline and, then, probed by the serial addition of oligomycin, FCCP and antimycin-A/rotenone (anti-A + rot). (a) Basal respiration, (b) ATP production and (c) maximal respiration capacity measured in NK-92, CD3-NK-92, TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, J6, J76 and J Radium-1, either CD3 treated or untreated. (n = 21). Error bars represent SD. (d) ExtraCellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) of NK-92, CD3-NK-92, TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, J6, J76 and J Radium-1, either CD3 treated or untreated, before and after addition of oligomycin is shown. Comparison of basal glycolytic activity between effector cells, either CD3 treated or untreated. (n = 21). Error bars represent SD. (e) Representative Reflection Interference Contrast (RIC) and TIRF micrographs of lymphocyte adhesion (RICM), actin and CD3 organization obtained after 20 min of spreading on glass slides coated with anti-HLA class I or -CD3. Scale bar 5 μm. (f) Box plot of contact area as determined from segmentation of RICM images. (g) Box plot of actin centrality. (h) Box plot of CD3 intensity at the cell-surface contact zone. For all box plots, n ≥ 50 cells per condition. (i) Confocal images of NK-92, TCR-NK-92 and T-cell previously activated and marked with anti Vβ3 (green) and phalloidin (red). Scale bar 4 μm. (j) Box plot of the anti Vβ3 signal intensity (n = 25). Error bars represent SD. (k) Box plot of the centralization of TCR molecules (cSMAC-number) (n = 25). Error bars represent SD. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Spreading over a surface is key to the T cell's physiological role of recognizing rare and low abundance antigenic ligands on the surface of antigen presenting cells [34]. The extent of T-cell spreading, while interacting with physiological ligands, is correlated with signal strength [35] and represents some of the earlier critical events involved in TCR triggering. We hypothesized that the introduction of CD3 and TCR into NK-92 cells could create a T cell-like surface area where TCR-NK-92 cells adopt a similar behavior to what has been observed in T cells upon APC contact [25]. To assess our hypothesis, we studied spreading area, actin organization and CD3 clustering in TCR-NK-92 with Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM) and Total Interference Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF). Synthetic surfaces coated with anti-CD3 or anti-HLA class I were used to mimic the surface of the APC carrying agonist or antagonist peptides. TCR-NK-92 exhibited large spreading adhesion after 15 min of contact on anti-CD3 than on anti-HLA class I (Fig. 3e,f and Fig. 5Sa,b), comparable to primary T cells. This confirmed the ability of the TCR-NK-92 to maximize the surface of adhesion upon activation mediated by the TCR in order to stabilize and sustain the activation signal. Unlike TCR-NK-92 and T cells, NK-92 and CD3-NK-92 cells did not respond to aCD3 coated surfaces, corresponding with their lack of surface CD3 expression (Fig. 3e,h). Actin reorganization is a key event in the process of T cell and APC encounter [36], permitting clustering of TCR and its coalescence to form the immune synapse. In this respect the ring formation, typical for the pre-establishment of the immune synapse, was seen in TCR-NK-92 upon anti-CD3 activation in a manner comparable to T cells (Fig. 3e,g and Fig. 5Sc). Finally, using anti-CD3 staining, we were able to measure similar levels of membrane CD3 in both TCR-NK-92 and T cells (Fig. 3e,h).

Immune synapse (IS) formation is often designated a key event in the complete and durable activation of the T-cell. It is composed of a polarized interface between the T-cell and the APC recognizable by the segregation of various receptors in concentric ring33s. TCR molecules are found in the center of the supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC) surrounded by a ring of integrins and filamentous actin. Its formation can be triggered by using a full-length anti-TCR antibody that will cross-link several TCR molecules leading to the formation of TCR microclusters that will coalesce into large clusters in IS-type fashion [37]. We pre-incubated NK-92, TCR-NK-92 and T cells with an antibody against the Vβ3 TCR chain prior to their incubation on aCD3 coated synthetic surface. As shown (Fig. 3i) only TCR-NK-92 and T-cells were able to form TCR macroclusters in the center of the cell-surface contact zone. The cSMAC zone was surrounded by a ring of actin exhibiting the typical IS structure. Moreover, TCR-NK-92 exhibited similar TCR density (Fig. 3j) with a similar ability to cluster it (Fig. 3k). Taken together, these results demonstrated that TCR-NK-92 cells are indeed like T cells in terms of basic spreading morphodynamics.

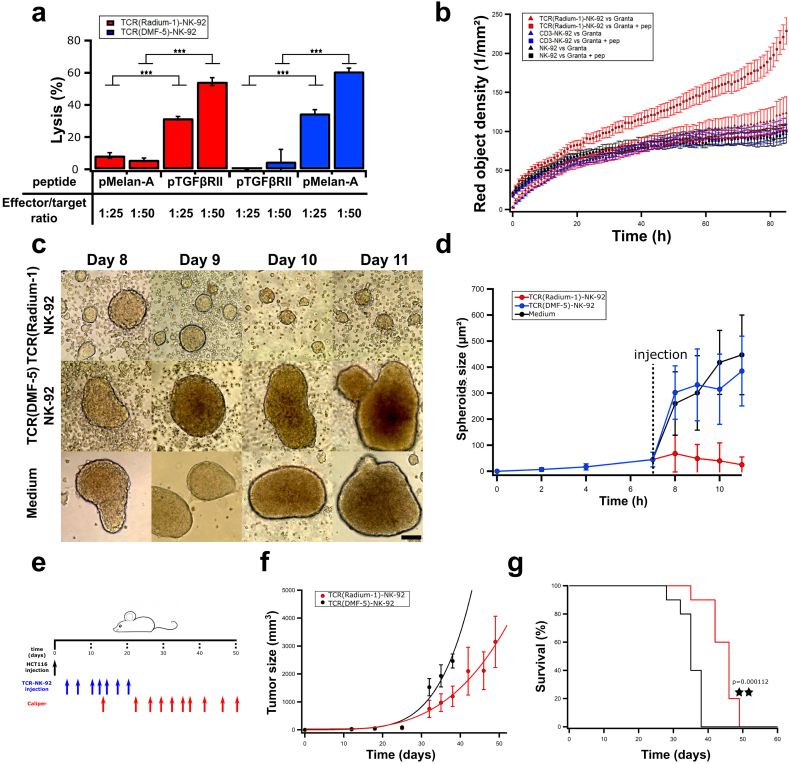

3.3. TCR-NK-92 are therapeutic effector cells

We assessed the killing capacity of TCR-NK-92 by direct measurement of their cytolytic capacity. HLA-A2 expressing K562 cells, which are resistant to NK killing when compared to the original cell line, were used as targets loaded with irrelevant or relevant peptide to quantify TCR-NK-92 killing in a Europium assay (Fig. 4a, red). TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 efficiently lysed K562:HLA-A2 in a peptide-dependent manner, and as expected, no specific killing was observed when irrelevant peptide was used. Similar observations were done with TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 (Fig. 4a, blue). Furthermore, long term anti-tumor activity of TCR-NK-92 was confirmed in vitro by Annexin V assay. TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 were tested against Granta-519 which is resistant to NK-92 killing [30] loaded with pTGFβRII (Fig. 4b, Supplementary movie). Specific killing of Granta-519 was significantly enhanced for TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 cells in comparison with NK-92 or CD3-NK-92 cells, demonstrating the advantage of guiding NK-92 cells with a TCR to eliminate cancers. Collectively, the in vitro data showed that TCR-NK-92 cells acquired T cell-like properties in terms of antigen discrimination, cytokine secretion, degranulation and cytotoxicity.

Fig. 4.

TCR-NK-92 mimic T cells in their lytic effector functions both in vitro and in vivo.

(a)-Antigen-specific lytic function of TCR-NK-92 cells (Radium-1 and DMF-5) measured by europium release assay. Bar graph showing % of target cells (K562:HLA-A2), either loaded or not with the cognate peptide, that were killed at 50:1 or 25:1 E:T ratio. (n = 3). Error bars represent SD. (b) Kinetic of tumor cell killing. TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, NK-92 and CD3-NK-92 were co-cultured with Granta-519 cells either expressing or not the cognate peptide (pep). The killing is expressed as red object density by Annexin V assay. (n = 32). Error bars represent SD. (c) Representative micrographs of HCT116 spheroids treated with TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 or medium. Scale bar 200 μm. (d) Evolution of the average spheroids size upon treatment with TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92, TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 or medium. (n = 28). Error bars represent SD. (e) Design of in vivo experiment using HCT116 xenograft mouse model. 10 mice per condition. (f) Evolution of tumor volume over time in treated (TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92) and untreated (TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92) mice. Error bars represent SD. (g) Corresponding Kaplan-Meier estimator. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

As a first indication of in vivo anti-tumor efficacy, we challenged TCR-NK-92 with spheroids of colorectal cancer cells HCT116 which are HLA-A2+ and express the TGFβRII frameshift mutant endogenously [38]. The goal was to reproduce in vitro the tumor morphology and its microenvironment in order to evaluate TCR-NK-92 potency against a structured target [27]. HCT116 spheroids were left to grow for 8 days and co-cultured or not with TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 or TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92. Only TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 were able to control the growth of HCT116 spheroids (Fig. 4c,d).

We then evaluated the in vivo anti-tumor activity of TCR-NK-92 cells in NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl /SzJ (NSG) mice subcutaneously injected with luciferase-expressing HCT116 colorectal cancer cells (Fig. 4e). The tumor load was significantly lower in mice that received TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92 treatment as compared to control mice receiving TCR(DMF-5)-NK-92 (Fig. 4f). Mice receiving the therapeutic TCR-NK-92 cells also had significantly enhanced survival compared with control mice (Fig. 4g). Taken together, the results from the pre-clinical in vivo study showed potential therapeutic efficacy of TCR-NK-92.

4. Discussion

In this report we showed that an NK cell line, NK-92, can be turned into a T-cell like effector cell by introducing the genes encoding the CD3 subunits. In agreement with our previous results [30] a full-length TCR alone cannot be expressed at the plasma membrane of NK-92 cells, and it is only by modifying the transmembrane region that the TCR can be exported. In addition to being correctly transported to the plasma membrane, we herein demonstrated that the protein was correctly folded and functional. The time of TCR residency at the membrane was sufficient for its detection and binding its substrate. Our TCR-pMHC dissociation kinetic analyses further suggest that the molecular interface of the TCR and its binding strength were comparable in the NK-92 and in the T-cell backgrounds. Although the TCR at the surface of TCR-NK-92 cells could recognize specific targets (pMHC), it was not obvious whether it would be able to transduce the pMHC-stimulation signal. Remarkably, when the TCR signaling machinery was transplanted to Hek cells, a battery of signaling proteins needed to be added to mimic the TCR in a T-cell environment [39]. Whereas in the context of NK-92, the TCR stimulation could trigger effector functions similar to those observed in T cells only by the addition of the CD3 complex. In this line, the gene expression profiling of TCR-NK-92 emphasized the potentiality of these cells to acquire a “fit” phenotype for becoming a potent T-cell like killer. This was observed without exogenous stimulation of the TCR, suggesting that the tonic signaling was sufficient to shape the genetic profile of an NK cell to a T-cell like profile. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that this new acquired gene profile might translate into a T-cell-like phenotype. We finally demonstrated that this “neo-T cell line” was functional in a pre-clinical setting, and that the presence of a TCR boosted target recognition potentially to the whole proteome.

The costs and the technical challenges of personalized redirected T-cell production represent a serious brake for the broad clinical application of cellular therapy against cancer. In addition, patients who have been through several rounds of treatments before TCR-based therapy might not qualify for treatment with autologous material due to the poor quality of their immune cells. To increase the feasibility of personalized cancer treatment and make it applicable also to patients with the most advanced disease, distinct strategies have been investigated to generate a universal antitumor T cell. Such a universal T cell will facilitate and shorten the clinical grade manufacturing in terms of ex vivo T-cell genetic manipulation, storage and validation. Generation of a universal T cell from a third party has already been exploited and seems appealing [40]. However, strategies to knock-down the endogenous TCR and the HLA should be included to avoid unpredictable off-target toxicities due to the endogenous TCR and rejection of the infused allogeneic T cells because of MHC mismatch. Using allogeneic T cells with defined specificity for virus [41] and, more recently, strategies to genetically disrupt endogenous TCR expression have been proposed to improve control of the endogenous TCR activity [[42], [43], [44], [45]]. Despite the encouraging results obtained by these strategies it is still not possible to completely exclude the risks of off-target toxicity and GVHD. Techniques to disrupt the endogenous TCR gene are still not optimal suggesting that purging unmodified T cells would be needed which would make the manufacturing process even more laborious. Lymphoid progenitors [46,47] and pluripotent stem cells [48,49] have also been exploited as a source of universal T cells for CAR and/or TCR therapy because they do not initiate any GVH reactions. However, the genomic instability and high genetic variations observed in iPSCs have raised serious concerns about their safety for clinical applications [50].

In contrast to T cells, TCR-NK-92 do not express any endogenous TCR. Moreover, recent clinical trials where NK-92 were infused have shown that despite their allogeneic origin the NK-92 did not cause severe toxicities and were poorly immunogenic and therefore not rejected by the host [11,12]. The main advantages of using TCR-NK-92 if compared to other sources of universal T cells is that they are an homogenous, well defined cell population; furthermore they are indefinitely expandable and easy to genetically manipulate. It is also worth noting that a strain of NK-92 independent of hIL-2 has been developed and is currently being tested in patients (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03027128), this could easily be repeated in TCR-NK-92 and would reduce the manufacturing costs even further. Therefore, stocks of TCR-NK-92 already reprogrammed to express different therapeutic TCRs could be frozen and maintained in a therapeutic biobank. TCR therapy would be readily available for patients with tumor antigens and HLA matching the TCRs existing in the TCR-NK-92 format (Fig. 5). Finally, the cell line used in the current study originates from non-GMP compliant stocks obtained through ATCC and may be different the GMP compliant derivatives currently under clinical investigation in FDA approved trials. We however have data showing that other NK cell lines can be redirected with TCR in the same way as TCR-NK-92 (Mensali and Wälchli, unpublished data). It is however obvious that if the FDA strain could be used, most of the presented experiments might need to be repeated, especially the gene expression analysis and the killing ability upon cell culture under GMP conditions. The overall encouraging data presented in the study offered the proof-of-principle for the use of a Universal Killer Cells engineered to express therapeutic TCRs for adoptive cell-based cancer therapy. Further studies are needed to confirm the potentiality of TCR-NK-92 cells and could pave the way for these cells as an “off-the shelf therapeutic live drug”.

Fig. 5.

Technical advantages of TCR-NK-92 based immunotherapy over T-cell based immunotherapy.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Annexin V live assay TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92

Annexin V live assay CD3-NK-92

Annexin V live assay NK-92

Supplementary material

Funding sources

N.M. and A.F. were supported by a BIOTEK2021 grant from the Research Council of Norway (#254817) and an innovation grant from South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (#14/00500-79). S.W., A.F. and M.R.M. were partially supported by an internal research grant of the gene therapy program from OUS-Radiumhospitalet. M.H. was supported by a grant from the department of Oncology at the University of Lausanne.

Declaration of interests

G.G., G.K., E.M.I. and S.W. are inventors of the patent WO2016116601, “Universal killer t-cell.”

Author contributions

Conceptualization G.G., G.K., E.M.I. and S.W.; Methodology, P.D., M.H., S.L., T.T., J.H.M., E.M.I. and S.W.; Investigation, N.M., P.D., M.H., S.L., M.R.M., A.F., J.H.M., E.M.I. and S.W.; Writing–Original Draft, N.M., P.D., E.M.I. and S.W.; Funding Acquisition, E.M.I and S.W., Supervision; E.M.I. and S.W. All authors approved the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Dirk Busch (TUM, Munich, Germany) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Laurent Limozin (LAI, Aix-Marseille University, France) and Dr. Kheya Sengupta (CINaM, Aix-Marseille University, France) for technical support (microscopy and data analysis). We thank Hedvig Vidarsdotter Juul for expert assistance with CyTOF analysis, the flow cytometry core facility at the Institute for Cancer research for help with cell sorting and G. Skorstad for technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Else Marit Inderberg, Email: elsin@rr-research.no.

Sébastien Wälchli, Email: sebastw@rr-research.no.

References

- 1.Fesnak A.D., June C.H., Levine B.L. Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:566–581. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson L.A., June C.H. Driving gene-engineered T cell immunotherapy of cancer. Cell Res. 2017;27:38–58. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg S.A., Restifo N.P., Yang J.C., Morgan R.A., Dudley M.E. Adoptive cell transfer: a clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:299–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg S.A., Restifo N.P. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2015;348:62–68. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4967. (80- ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Themeli M., Rivière I., Sadelain M. New Cell sources for T Cell Engineering and Adoptive Immunotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingemann H., Boissel L., Toneguzzo F. Natural killer cells for immunotherapy - advantages of the NK-92 cell line over blood NK cells. Front Immunol. 2016;7:91. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suck G., Odendahl M., Nowakowska P. NK-92: an ‘off-the-shelf therapeutic’ for adoptive natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1761-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suck G., Linn Y.C., Tonn T. Natural killer cells for therapy of leukemia. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2016;43:89–95. doi: 10.1159/000445325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong J.H., Maki G., Klingemann H.G. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia. 1994;8:652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonn T., Becker S., Esser R., Schwabe D., Seifried E. Cellular immunotherapy of malignancies using the clonal natural killer cell line NK-92. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001;10:535–544. doi: 10.1089/15258160152509145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai S., Meagher R., Swearingen M. Infusion of the allogeneic cell line NK-92 in patients with advanced renal cell cancer or melanoma: a phase I trial. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:625–632. doi: 10.1080/14653240802301872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonn T., Schwabe D., Klingemann H.G. Treatment of patients with advanced cancer with the natural killer cell line NK-92. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:1563–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C., Oberoi P., Oelsner S. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered NK-92 cells: an off-the-shelf cellular therapeutic for targeted elimination of cancer cells and induction of protective antitumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2017;8:533. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang X., Yang L., Li Z. First-in-man clinical trial of CAR NK-92 cells: safety test of CD33-CAR NK-92 cells in patients with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8:1083–1089. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jochems C., Hodge J.W., Fantini M. An NK cell line (haNK) expressing high levels of granzyme and engineered to express the high affinity CD16 allele. Oncotarget. 2016;7:86359–86373. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grier J.T., Forbes L.R., Monaco-Shawver L. Human immunodeficiency-causing mutation defines CD16 in spontaneous NK cell cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3769–3780. doi: 10.1172/JCI64837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngoenkam J., Schamel W.W., Pongcharoen S. Selected signalling proteins recruited to the T-cell receptor-CD3 complex. Immunology. 2018;153:42–50. doi: 10.1111/imm.12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walchli S., Kumari S., L-EE Fallang. Vol. 44. 2014. Invariant chain as a vehicle to load antigenic peptides on human MHC class I for cytotoxic T-cell activation; pp. 774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillard P., Köksal H., Inderberg E.-M., Spheroid Wälchli S.A. Killing assay by CAR T cells. J Vis Exp. 2018 doi: 10.3791/58785. published online Dec 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szymczak A.L., Workman C.J., Wang Y. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wälchli S., Løset G.Å., Kumari S. A practical approach to T-cell receptor cloning and expression. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inderberg E.M., Walchli S., Myhre M.R. T cell therapy targeting a public neoantigen in microsatellite instable colon cancer reduces in vivo tumor growth. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1302631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loew R., Heinz N., Hampf M., Bujard H., Gossen M. Improved Tet-responsive promoters with minimized background expression. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebeisen M., Schmidt J., Guillaume P. Identification of rare high-avidity, tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells by monomeric TCR-ligand off-rates measurements on living cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1983–1991. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillard P., Varma R., Sengupta K., Limozin L. Ligand-mediated friction determines morphodynamics of spreading T cells. Biophys J. 2014;107:2629–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Josefsson S.E., Huse K., Kolstad A. T cells expressing checkpoint receptor TIGIT are enriched in follicular lymphoma tumors and characterized by reversible suppression of T-cell receptor signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:870–881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaheen S., Ahmed M., Lorenzi F., Nateri A.S. Spheroid-formation (Colonosphere) assay for in vitro assessment and expansion of stem cells in colon cancer. Stem Cell Rev. 2016;12:492–499. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9664-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson L.A., Heemskerk B., Powell D.J. Gene transfer of tumor-reactive TCR confers both high avidity and tumor reactivity to nonreactive peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177:6548–6559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hervas-Stubbs S., Perez-Gracia J.L., Rouzaut A., Sanmamed M.F., Le Bon A., Melero I. Direct effects of type I interferons on cells of the immune system. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2619–2627. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walseng E., Köksal H., Sektioglu I.M.M. A TCR-based chimeric antigen receptor. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müller T., Uherek C., Maki G. Expression of a CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances cytotoxic activity of NK cells and overcomes NK-resistance of lymphoma and leukemia cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:411–423. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uherek C., Tonn T., Uherek B. Retargeting of natural killer-cell cytolytic activity to ErbB2-expressing cancer cells results in efficient and selective tumor cell destruction. Blood. 2002;100:1265–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Betts M.R., Koup R.A. Detection of T-cell degranulation: CD107a and b. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;75:497–512. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)75020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fooksman D.R., Vardhana S., Vasiliver-Shamis G. Functional Anatomy of T Cell Activation and Synapse Formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crites T.J., Padhan K., Muller J. TCR Microclusters pre-exist and contain molecules necessary for TCR signal transduction. J Immunol. 2014;193:56–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi J., Wu X.S., Crites T., Hammer J.A. Actin retrograde flow and actomyosin II arc contraction drive receptor cluster dynamics at the immunological synapse in Jurkat T cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:834–852. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metzger H. Transmembrane signaling: the joy of aggregation. J Immunol. 1992;149:1477–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., Sun L., Myeroff L. Demonstration that mutation of the type II transforming growth factor beta receptor inactivates its tumor suppressor activity in replication error-positive colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22044–22049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James J.R., Vale R.D. Biophysical mechanism of T-cell receptor triggering in a reconstituted system. Nature. 2012;487:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qasim W., Zhan H., Samarasinghe S. Molecular remission of infant B-ALL after infusion of universal TALEN gene-edited CAR T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heslop H.E., Ng C.Y., Li C. Long-term restoration of immunity against Epstein-Barr virus infection by adoptive transfer of gene-modified virus-specific T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 1996;2:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eyquem J., Mansilla-Soto J., Giavridis T. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torikai H., Reik A., Liu P.-Q. A foundation for universal T-cell based immunotherapy: T cells engineered to express a CD19-specific chimeric-antigen-receptor and eliminate expression of endogenous TCR. Blood. 2012;119:5697–5705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berdien B., Mock U., Atanackovic D., Fehse B. TALEN-mediated editing of endogenous T-cell receptors facilitates efficient reprogramming of T lymphocytes by lentiviral gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2014;21:539–548. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Provasi E., Genovese P., Lombardo A. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012;18:807–815. doi: 10.1038/nm.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zakrzewski J.L., Kochman A.A., Lu S.X. Adoptive transfer of T-cell precursors enhances T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Med. 2006;12:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/nm1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zakrzewski J.L., Suh D., Markley J.C. Tumor immunotherapy across MHC barriers using allogeneic T-cell precursors. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishimura T., Kaneko S., Kawana-Tachikawa A. Generation of rejuvenated antigen-specific T cells by reprogramming to pluripotency and redifferentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Themeli M., Kloss C.C., Ciriello G. Generation of tumor-targeted human T lymphocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:928–933. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshihara M., Hayashizaki Y., Murakawa Y. Genomic Instability of iPSCs: challenges Towards their Clinical applications. Stem Cell Rev. 2017;13:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9680-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Annexin V live assay TCR(Radium-1)-NK-92

Annexin V live assay CD3-NK-92

Annexin V live assay NK-92

Supplementary material