Abstract

Subcellular fractionation of tissue homogenate provides enriched in vitro models (e.g., microsomes, cytosol, or membranes), which are routinely used in the drug metabolism or transporter activity and protein abundance studies. However, batch-to-batch or inter-laboratory variability in the recovery, enrichment and purity of the subcellular fractions can affect performance of in vitro models leading to inaccurate in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) of drug clearance. To evaluate the quality of subcellular fractions, we developed a simple targeted and sensitive LC-MS/MS proteomics based strategy, which relies on determination of protein markers of various cellular organelles, i.e., plasma membrane, cytosol, nuclei, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomes, peroxisomes, cytoskeleton, and exosomes. Application of the quantitative proteomics method confirmed significant effect of processing variables (i.e., homogenization method and centrifugation speed) on the recovery, enrichment, and purity of isolated proteins in microsomes and cytosol. Particularly, markers of endoplasmic reticulum lumen and mitochondrial lumen were enriched in the cytosolic fractions as a result of their release during homogenization. Similarly, the relative recovery and composition of the total membrane fraction isolated from cell vs. tissue samples was quantitatively different and should be considered in IVIVE. Further, analysis of exosomes isolated from sandwich-cultured hepatocyte media showed the effect of culture duration on compositions of purified exosomes. Therefore, the quantitative proteomics based strategy developed here can be applied for efficient and simultaneous determination of multiple protein markers of various cellular organelles when compared to antibody- or activity-based assays, and can be used for quality control of subcellular fractionation procedures including in vitro model development for drug metabolism and transport studies.

Introduction

The use of human tissue derived in vitro models of drug metabolism and transport has significantly helped in decreasing drug attrition during clinical development previously related to pharmacokinetic liabilities (PK).1 Particularly, enriched fractions such as microsomes, cytosol, or S9 fractions from human liver and intestine are routinely used to generate in vitro drug clearance data (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm292362.pdf;). These data for new molecular entities can be integrated into physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models to predict in vivo human drug metabolism and drug-drug interactions (DDIs).1 However, the success of PBPK relies on the quality of the in vitro models, which are susceptible to batch-to-batch or inter-laboratory variability due to the crude nature of the subcellular fractionation.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane but non-CYP DMEs can be present in the cytosol, lumen of different cellular organelles or membrane-bound. Therefore, subcellular fractionation procedures, such as differential centrifugation, are often used to prepare enriched DMEs, which allows high activity of specific enzymes in these in vitro models. Although the subcellular localization and the purity of CYPs in microsomal fractions are well characterized2, microsomal protein per gram of liver (MPPGL) is critical information that is required for extrapolating CYP mediated drug clearance from the microsomal activity data, i.e., pmol/min/mg protein to pmol/min/per gram tissue. Because the literature value of MPPGL is highly variable (e.g., 17–85)2,3 depending on the inter-laboratory differences in microsomal isolation procedure or sample characteristics, MPPGL should ideally be derived for each microsomal preparation. Further, the current practice of deriving MPPGL assumes that all the microsomal DMEs are located in ER membrane similar to CYP DMEs. Which means that if the relative recovery of the CYP and non-CYP DMEs expressed in ER are different in the microsomes, conventional MPPGL will result in an incorrect scaling factor and subsequent poor in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE). Similar assumptions are used when estimating cytosolic proteins per gram of liver (CPPGL). Further, the subcellular localization of some non-CYP DMEs is not well characterized, which can result in the selection of inappropriate in vitro models. Similarly, as a metabolic pathway (e.g., oxidation) can be mediated by multiple enzymes, characterization of enrichment and purity of a subcellular fraction is critical. For example, aldehyde oxidase (AO) and alcohol or aldehyde dehydrogenases (ADHs/ALDHs) are cytosolic proteins but they can also contribute to oxidization of drugs similar to CYPs in the microsomes if present as a contaminant.4 This problem is further compounded as new chemical molecules are intentionally designed to be substrates of non-CYP enzymes, to avoid CYP-metabolism liabilities.5

Transporter studies are generally conducted on cryopreserved primary cells (e.g., human hepatocytes), transporter overexpressing cells or vesicles.6 Since in vitro culture of primary cells can alter the expression of transporters and transporter-overexpressing cells are non-physiological, protein abundance in total cell (crude) membrane or plasma membrane from these cells is extrapolated to tissues using quantitative proteomics to predict transporter mediated in vivo clearance.7,8,9 However, these transporter proteomics data would result in inaccurate IVIVE if the purity, inter-laboratory and inter-preparation consistency of these membrane preparations is not measured. Additionally, a number of transporters (e.g., SLC11A2) and DMEs (e.g., MAOA and MAOB) are expressed in unique intracellular organelles, requiring systematic characterization of subcellular localization of these proteins to develop in vitro models for IVIVE of substrates of these DMEs. 10,11

To address these challenges, a strategy that can simultaneously evaluate the quality of the subcellular fractions (recovery, enrichment and purity) is required for IVIVE of drug metabolism and transport. Measurement of recovery and enrichment requires the use of markers of the corresponding subcellular fraction of interest, and estimation of purity needs the use of markers of other subcellular organelles other than subcellular fraction of interest.12 CYP content, CYP reductase activity, glucose-6-phosphatese activity are commonly used as microsomal protein markers, and glutathione-S-transferase and ADH activity are used as cytosolic markers13. However, the results of these methods will be inaccurate if the subcellular fractions are not pure or the activities of the protein markers are weak13. Though Western blot is often used to confirm the purity of the subcellular fractions, this method is not readily amenable to efficiently quantify multiple protein markers. Here, we developed a targeted proteomics method to simultaneously quantify various organelle markers representing plasma membrane, cytosol, nuclei, mitochondria, ER, lysosomes, peroxisomes, cytoskeleton and exosomes (Table 1). The method was then applied to characterize the effect of homogenization methods and centrifugation speed on purity, enrichment, and recovery of each fraction isolated during typical microsomal and cytosolic preparation from liver tissue. We also used the proteomics method to quantify and compare the purity of the total membrane extract using commercially available kits. Exosomes derived from biofluids (urine and plasma) are thought to be potential non-invasive method for predicting inter-individual variability in drug metabolism and transport. Therefore, we used the developed proteomics methods of exosomal markers, subcellular markers and drug metabolizing enzymes to characterize exosomes secreted from human hepatocytes.

Table 1.

Subcellular localization, surrogate peptides and cross-species homology information of organelle markers used in this study.

| Protein Name | UniProt ID | Subcellular location | Peptide | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+/K+ ATPase alpha 1 subunit | P05023 | Membrane | IVEIPFNSTNK | Human, Bovine, Dog, Mouse, Rat, Horse, Pig, Sumatran orangutan, Rabbit and Sheep | 14 |

| LSLDELHR | Human, Bovine, Dog, Mouse, Rat, Pig, Sumatran orangutan, Rabbit and Sheep | ||||

| Hsp60 | P10809 | Mitochondrial matrix | GYISPYFINTSK | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Chinese hamster, Golden hamster and Sumatran orangutan | 15 |

| VTDALNATR | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Chinese hamster, Golden hamster and Sumatran orangutan, | ||||

| Vimentin | P08670 | Cytoskeleton | ILLAELEQLK | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Green monkey, Chinese hamster, Cynomolgus monkey, Golden hamster, Chimpanzee, Pig and Sheep | 16 |

| DNLAEDIMR | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Golden hamster, Chimpanzee and Pig | ||||

| Desmin | P17661 | Cytoskeleton | LLEGEESR | Human, Bovine, Dog, Mouse, Rat, Golden hamster and Pig | 17 |

| Histone H1.1 | Q02539 | Nucleus | ALAAAGYDVEK | Human and Bovine | 18 |

| GTGASGSFK | Human and Bovine | ||||

| Lamin-B1 | P20700 | Nuclear envelope | ALYETELADAR | Human, Mouse and Rat | 19 |

| LLEGEEER | Human, Mouse and Rat | ||||

| NADPH CYP450 reductase | P16435 | ER membrane | FAVFGLGNK | Human, Mouse and Rat | 20 |

| YYSIASSSK | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Guinea pig, Pig and Rabbit | ||||

| Calnexin | P27824 | ER membrane | IVDDWANDGWGLK | Human and Sumatran orangutan | 21 |

| GLVLMSR | Human, Dog, Mouse, Rat and Sumatran orangutan | ||||

| Calreticulin | P27797 | ER lumen | EQFLDGDGWTSR | Human, Green monkey, Cynomolgus monkey and Japanese macaque | 22 |

| FVLSSGK | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Green monkey, Chinese hamster, Cynomolgus monkey, Japanese macaque, Pig and Rabbit | ||||

| Catalase | P04040 | Peroxisome matrix | ADVLTTGAGNPVGDK | Human, Common marmoset and Sumatran orangutan | 23 |

| LNVITVGPR | Human and Sumatran orangutan | ||||

| PMP70 | P28288 | Peroxisome membrane | VLGELWPLFGGR | Human and Mouse | 23 |

| DLNFEVR | Human | ||||

| Cathepsin L1 | P07711 | Lysosome lumen | GYVTPVK | Human, Bovine, Dog, Green monkey and Sheep | 24,25 |

| CD-MPR | P20645 | Lysosome membrane | AVVMISCNR | Human, Bovine, Mouse and Rat | 26 |

| NVPAAYR | Human, Bovine and Mouse | ||||

| LAMP-1 | P11279 | Lysosome membrane | TVESITDIR | Human | 27 |

| ALQATVGNSYK | Human, Mouse and Chinese hamster | ||||

| Hsp 90-beta | P08238 | Cytosol | ALLFIPR | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Horse, Cynomolgus monkey and Sumatran orangutan | 28 |

| ADLINNLGTIAK | Human, Mouse, Rat, Horse, Cynomolgus monkey and Sumatran orangutan | ||||

| LDH-H | P07195 | Cytosol | FIIPQIVK | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Cynomolgus monkey, Mondo, Chimpanzee, Pig and Rabbit | 29 |

| LNLVQR | Human, Bovine, Mouse, Rat, Cynomolgus monkey, Mondo, Chimpanzee and Pig | ||||

| TGM2 | P21980 | EDITHTYK | Human, Mouse and Guinea pig | 30 | |

| CD26 | P27487 | LAYVWNNDIYVK | Human, Bovine and Pig | 31 | |

| IISNEEGYR | Human |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Reagents.

Iodoacetamide (IAA), dithiothreitol (DTT), bovine serum albumin (BSA), trypsin protease (MS grade) and synthetic isotope-labeled peptides were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Ammonium bicarbonate (ABC, 98% purity) buffer was bought from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Chloroform, MS-grade acetonitrile (99.9% purity), methanol and formic acid (≥99.5% purity) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Human serum albumin (HSA) was obtained from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from VWR Seradigm (Radnor, PA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and penicillin-streptomycin solution were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Exoquick TC solution was obtained from System Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA).

Liver tissue samples were procured from the University of Washington (UW) liver bank. The collection and use of these tissues were approved by the human subjects Institutional Review Boards of the UW (Seattle, WA). Primary human hepatocytes (detailed demographic information can be found in Table S-1) were kindly donated by BioreclamationIVT (Baltimore, MD). HepG2 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Microsomes Preparation.

Microsomes were prepared by differential centrifugation (Figure 1A). In brief, frozen human liver tissue (n=3) was thawed and cut into 12 approximately equal pieces (~500 mg), weighed, and transferred to a 15 mL plastic homogenization tube. After adding 3.5 mL of ice-cold homogenization buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 0.25 M sucrose and 1.0 mM EDTA; final pH 7.4), livers were homogenized using an Omni Bead Ruptor12 Homogenizer (18 ceramic beads, 5.8 m/s, 45 sec/cycle, 2 cycles, 90 sec dwell time, 4˚C). Then the homogenate (H) was centrifuged at low centrifugation speeds (6K, 9K, 12K or 15K x g) for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatant (S1) was transferred to a 10 mL ultracentrifuge tube. Remaining pellet (P1) was resuspended with 500 μL of storage buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 0.25 M sucrose and 10mM EDTA; final pH 7.4). S1 fraction (8 mL) was centrifuged at 60K, 90K, or 120K x g for 70 min at 4°C. The supernatant (S2) was collected, and the pellet (P2) was resuspended in 8 mL of wash buffer (10mM potassium phosphate buffer, containing 0.1 mM KCl and 1.0 mM EDTA; final pH 7.4). The resuspended P2 fractions were spun second time in the ultracentrifuge at 120K 0 g for 70 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant (S3) was collected. The pellet was resuspended with 1 mL storage buffer (P3). All collected samples were stored at −80°C until use.

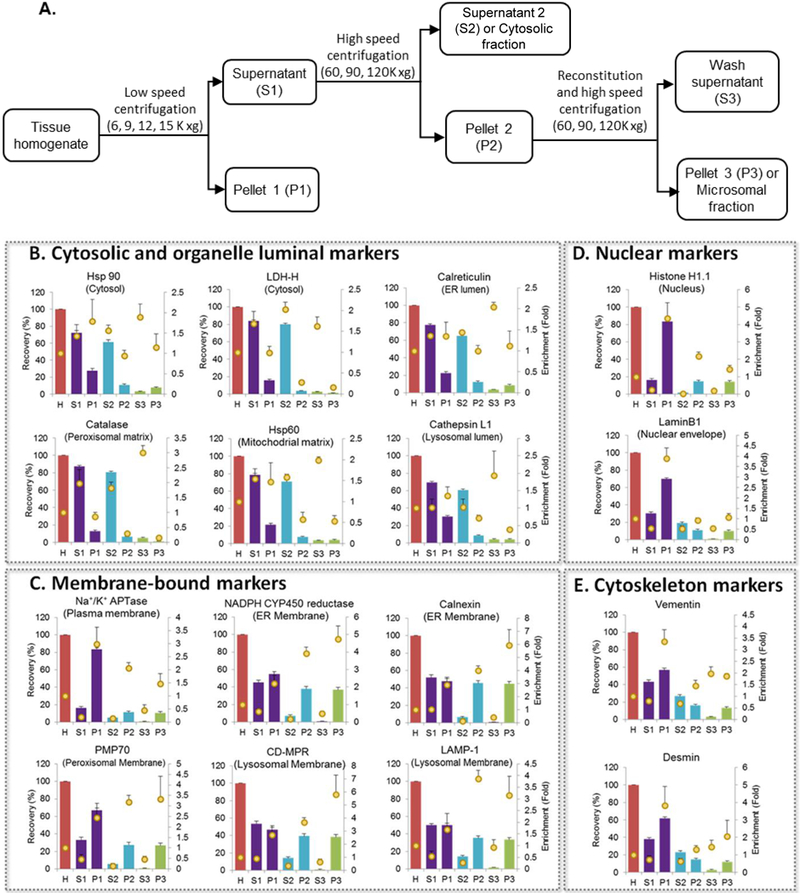

Figure 1. Recovery and enrichment of organelle markers in different subcellular fractions isolated during microsomal preparation.

A. Schematic figure of microsomal preparation by differential centrifugation. Recovery (bars) and enrichment (dots) of organelle markers (B. Cytosolic and organelle luminal markers; C. Membrane-bound markers; D. Nuclear markers and E. Cytoskeleton markers) in different liver subcellular fractions using typical low- (9,000 xg) and ultra- (120,000 xg) centrifugation speeds (mean±S.E., n=3) after homogenization with bead homogenizer (3 cycles). H: Homogenate; S1: S9 fraction; P1: Pellet 1 (heavy membrane); S2: Cytosolic fraction; P2: Pellet 2; S3: Wash supernatant; P3: Microsomal fraction.

Effect of four different homogenization methods (H1: bead homogenizer, 14 magnetic beads, 2 cycles; H2: bead homogenizer, 18 ceramic beads, 3 cycles; H3: hand-held rotary homogenizer; and H4: cryogenic grinding with mortar and pestle, Supporting Information: [Supplementary Experimental Procedure]) on the quality of subcellular fractions were evaluated in a separate experiment. Low- and ultra-centrifugation variability were tested in three livers, and impact of homogenization methodology was tested in one liver.

Total Membrane Isolation

The cytosolic and total membrane fractions of HepG2 cells, hepatocyte, and human liver tissue were isolated using two different commercially available kits (Thermo Scientific™ Mem-PER™ Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit and Calbiochem® total Membrane Protein Extraction Kits) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Detailed description of the isolation procedure is provided in the Supporting Information: [Supplementary Experimental Procedure].

Exosomes Isolation from Human Hepatocyte Media

Media isolated at 24, 48 and 72 hours after plating of sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes (n=4 donors) were used for exosomes isolation. Approximately 50 mL of culture supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 3000 ×g for 15 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Cells were then filtered using 0.22 μm filter (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) and the remaining filtered supernatant was concentrated to 1.5 mL using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter with a 10 KDa molecular weight cut off by centrifugation in a swing-out rotor at 4°C and 4000 ×g for 45 minutes. The concentrated culture medium was added to an equal volume of ExoQuick TC exosomes precipitation solution and the resulting solution was mixed by inverting the tube and allowing it to stand overnight in a refrigerator. This mixture was then centrifuged at 1500 ×g for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was collected.

LC-MS/MS Based Proteomics Method Development for Cell Organelle Markers

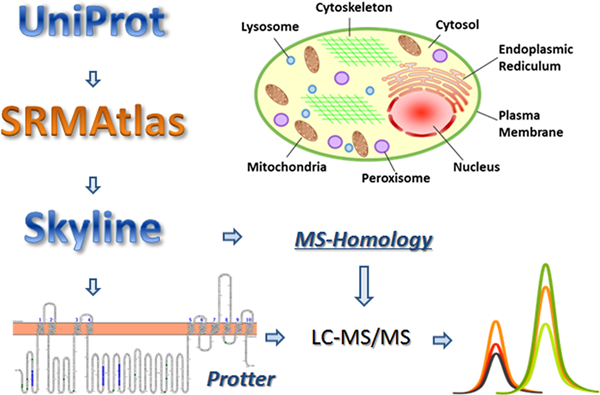

A list of cell organelle-specific proteins was created after thorough literature search. Surrogate peptides of all candidate markers were then selected according to several criteria which have been well presented in our previous articles and summarized here (Figure 2).32,33 Briefly, the protein accession number and full sequence were obtained from UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/). Potential surrogate peptides of the protein markers were generated using in silico digestion tool SRMAtlas (https://db.systemsbiology.net/sbeams/cgi/PeptideAtlas). Then, the peptide candidates were transferred to Skyline (UW, Seattle, WA). The Skyline plugin Protter (http://wlab.ethz.ch/protter/start/) was used to eliminate peptides containing transmembrane region, posttranslational modification (PTM), reactive residues (such as cysteine and methionine), conflicting sequence, continuous sequence of arginine (R) or lysine (K) (ragged ends), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or other genetic variations. The specificity of the remaining peptides was verified using the online tool MS-Homology (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/cgi-bin/msform.cgi?form=mshomology). Heavy peptides were purchased to select the most sensitive and reliable peptides and to optimize their LC-MS/MS parameters. Two to four candidate markers were selected for each organelle, and three to four surrogate peptides were optimized for each marker. Each standard peptide was optimized for response from three MRM transitions, but only markers detectable in the samples were used in this study (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Surrogate peptide selection for LC-MS/MS quantification of markers of subcellular fractions.

A robust validation approach was used to ensure precise quantification of the organelle markers.33 Prior to trypsin digestion, BSA (20 μL, 0.02 mg/mL) was added to each sample as an exogenous protein internal standard to correct for processing and digestion variability with the assumption that the trypsin digestion susceptibility of BSA remains similar to all proteins in the sample. A cocktail of heavy-labeled peptides was added to quench the digestion and to address retention time shifts and ion suppression (equation 1). BSA peptide ratio (light/heavy) was used to normalize data to correct artifacts in trypsin digestion (RoR is referred to Ratio of Ratios, equation 2). Correlation between multiple transitions and peptides were used to confirm robustness of data.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Protein Digestion and LC-MS/MS Quantification of Organelle Protein Markers

Protein quantification of organelle markers was carried out using an LC-MS/MS proteomics method. Total protein content present in each sample was evaluated using a BCA assay kit. One to two surrogate peptides were selected for organelle marker quantification and corresponding heavy peptides containing terminal labeled [13C615N4]-R and [13C615N2]-K residues were used as internal standards. Total protein equivalent to 160 μg in isolated fraction was digested as described previously with minor modifications.34,35 Briefly, after adding 10 μL of HSA (10 mg/mL) and 10 μL of BSA (0.2 mg/mL) successively, the samples were denatured and reduced with 10 μL of DTT (250 mM) and 40 μL of ABC buffer (100 mM) for 10 min at 300 RPM and 95°C in a thermomixer. After cooling to room temperature for 10 min, the denatured protein was alkylated by incubating in the dark with 20 μL of IAA (500 mM) for 30 minutes. Ice-cold methanol (500 μL), chloroform (100 μL) and water (400 μL) were then added to each sample. After vortex-mixing and centrifugation at 16,000 × g (4°C) for 5 minutes, the upper and lower layers were removed using vacuum suction and the pellets were dried at room temperature for 10 minutes. The pellets were then washed with 500 μL ice-cold methanol and centrifuged at 8000 × g (4°C) for 5 minutes. After the supernatant was removed, the pellets were dried at room temperature for 30 minutes and re-suspended in 60 μL ABC buffer (50 mM). The dried protein pellets were digested by adding 20 μL of trypsin (protein: trypsin ratio, approximately 80:1) and incubating at 37 °C and 300 RPM shaking for 16 hours. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 20 μL of peptide internal standard cocktail (prepared in 80% acetonitrile in water containing 0.5% formic acid) and 10 μL 80% acetonitrile in water containing 0.5% formic acid. The samples were vortex-mixed and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g and 4°C for 5 min and the supernatants were collected in LC-MS vials. Quantification was performed using a triple-quadrupole MS instrument (Sciex Triple Quad 6500, Ontario, Canada) in ESI positive ionization mode, coupled to an Acquity UPLC, I-class (Waters Technologies, Milford, MA). Five μL (8 μg protein) of the trypsin digest was injected into the column (Acquity UPLC HSS T3 1.8μm, C18 100A; 100 × 2.1 mm, Waters, Milford, MA). Surrogate light and heavy (internal standards) peptides were monitored using instrument parameters provided in Table S-2 (Supporting Information). LC-MS/MS data were processed using Analyst 1.6.2 version software (PE Sciex, Ontario, Canada) and Skyline 3.7 version software (MacCoss lab, WA, USA), and then transferred to Microsoft excel for further analysis.

Data Analysis

Recovery and enrichment of individual organelle marker in each human liver subcellular fraction relative to homogenate were calculated as per Equations 3 and 4:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where, S and P represent supernatant and pellet, respectively; x is the 1st, 2nd or 3rd centrifugation, and H represents homogenate.

We assumed that all microsomal or cytosolic proteins were enriched to the same extent as the specific organelle markers used. Then MPPGL and CPPGL were calculated using the following equations (5 and 6).

| (5) |

| (6) |

Relative recovery of each organelle marker in total membrane and cytosolic fractions isolated using the commercially available kits were calculated using Equations 7 and 8:

| (7) |

| (8) |

Where M is the membrane fraction, and C is the cytosolic fraction.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Version 14, Redmond, WA, USA). One-way ANOVA and Dunnett post-test were used to compare different processing methods. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-test were used to compare different exosomal results. A P-value below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Targeted proteomics method for characterization of subcellular markers

The markers of plasma membrane, cytosol, nuclei, mitochondria, ER, lysosomes, peroxisomes, cytoskeleton and exosomes, selected based on previous studies (Table 1), were quantified using a single 25 min targeted method in a conventional triple quadrupole LC-MS/MS instrument using method parameters shown in Table S-2 (Supporting Information). All the transitions listed in the Table S-2 (Supporting Information) were considered in the calculation. The area ratios were calculated by dividing average of two to three light peptide transitions by average of two heavy peptide transitions. Figure S-1 (Supporting Information) shows a representative example of method validation steps. The peak assignments or retention time shifts were confirmed by comparing light and heavy peptide peaks (e.g., 14.2 min for peptide, DNLAEDIMR; Figure S-1A). Correlation between multiple transitions and peptides confirmed the specificity of the signal (Figures S-1B, S-1C). Contrary to immunolocalization, targeted proteomics method does not require antibodies, and thus has wide application to characterize subcellular localization of any protein by preforming simultaneous analysis of the markers and proteins of interest. In drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic studies, these markers can be used as surrogates of DMEs and transporters for deriving scaling factors, e.g., MPPGL and as a quality control approach for in vitro models. The major advantage of this method is that it can simultaneously analyze multiple markers of subcellular organelle recovery, enrichment and purity with great sensitivity over other antibody- or activity-based assays.2,13,36

Recovery, enrichment and purity of isolated subcellular fractions

Subcellular fractionation was initially developed for the separation of organelles derived from rat liver based on their physical properties.37 In order to explicitly define each fractions (cytosol, S9 or microsomes), we use the following terms. S1 (often referred to as S9 when 9,0000xg is used to spin the tissue homogenate) or P1 fraction refers to the supernatant or pellet after the first centrifugation (9,000xg), S2/P2 and S3/P3 fractions are the supernatants or pellets after the second (120,000xg for wash) and third centrifugation (120,000xg for microsomes preparation), respectively.

Figures 1B-E show summary of recovery and enrichment data of different subcellular markers in each fraction using typical low- (9,000 ) and ultra- (120,000 xg) centrifugation speeds (mean±S.E., n=3) after homogenization with bead homogenizer (3 cycles). As expected, nuclear and cytosolic markers were recovered mostly (>60%) and enriched (>2-fold) in P1 and S2 fractions, respectively. The most notable and unexpected finding was regarding the recovery of the two ER membrane markers (calnexin and NADPH CYP450 reductase, 44.9±5.9% and 37.0±3.5%, respectively, Figure 1C), which was significantly higher than the ER luminal marker (calreticulin) (8.5±1.2%, Figure 1B) in the P3 fraction (microsomal fraction). Contrarily, the ER luminal marker was recovered higher in the cytosolic fraction (65.2±3.0%, Figure 1B). These results indicated that a conventional microsomal fraction is not an optimal in vitro system to study activity of ER luminal proteins such as carboxylesterases (CESs) when using cryopreserved liver tissues.38 Similarly, the other organelle luminal markers were also abundant in the cytosolic fractions (Figure 1B), indicating that organelle luminal content may leak into cytosol during homogenization due to the freezing-associated damage of organelles.39 Another unexpected result was the higher recovery of ER membrane markers in P1 fraction versus P2 or P3 fraction (Figure 1B). This was also observed by Wisniewski et al., previously39, which is perhaps due to the attachment of ER membrane to the outer mitochondrial membrane.40 Furthermore, the recovery and enrichment data of organelle markers (Figure 1) was also analyzed to determine purity of subcellular fractions. The P3 (microsomes) fraction showed significant contamination by lysosomal and peroxisomal membrane, whereas the S2 (cytosol) fraction showed contamination from ER lumen, peroxisomal matrix, mitochondrial matrix, lysosomal lumen, cytoskeleton, and nuclear envelope.

The calculated MPPGL and CPPGL data are shown in Table 2. Conventionally, total CYP450 content, activity of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), and NADPH CYP450 reductase are used as recovery markers for liver microsomal protein whereas activity of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) are used as the cytosolic protein markers.13 In the present study, we successfully evaluated MPPGL and CPPGL which are within the range of previously published values.2,41 The method provided here, can generate scaling factors associated with each subcellular preparation with proper organelle markers for many tissues such as liver, intestine, kidney, lung, heart, brain, etc, irrespective of variable enrichment of proteins of interest. However, enrichment ensures high and specific activity or sensitive detection of protein(s) of interest in a given fraction.

Table 2.

MPPGL and CPPGL calculated using organelle markers.

| Scaling factor | Recovery values using organelle markers |

Literature value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker 1 | Marker 2 | ||

| MPPGL | 31.8±16.4a | 32.7±18.1b | 17–852,3 |

| CPPGL | 64.7±10.2c | 64.1±9.9d | 45–13441 |

Specific organelle marker-based correction factor applied:

Calnexin;

NADPH CYP450 reductase;

Hsp90;

LDH

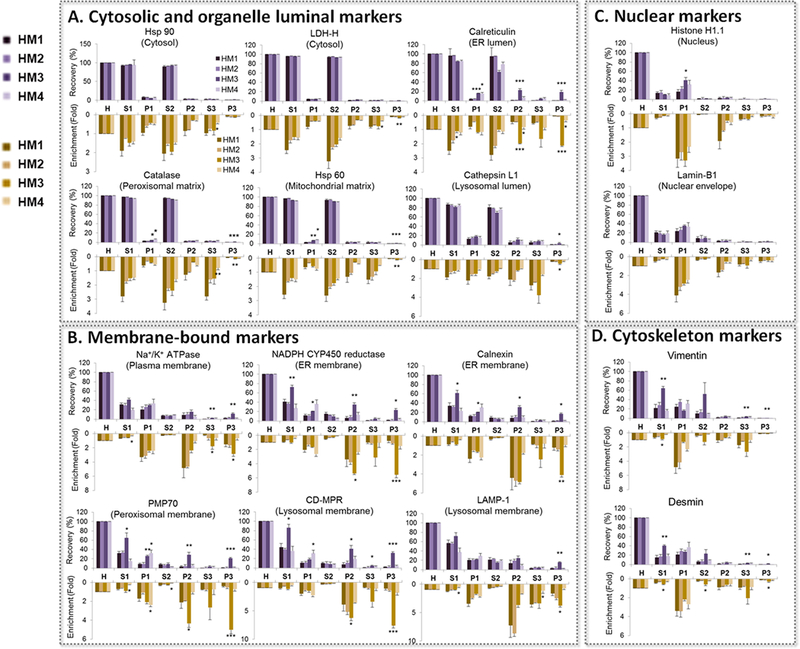

We then applied this targeted proteomics method to investigate the impact of variation in subcellular fractionation procedures on recovery, enrichment and purity of widely-used in vitro assay systems. To do so, we calculated the recovery and enrichment of the selected organelle markers relative to the homogenate in multiple liver subcellular fractions, using four different homogenization methods and various low- (n = 4) and ultra-centrifugation (n = 3) speeds. The recovery and enrichment of the ER membrane markers, but not of the ER luminal marker, in P3 fraction (microsomes) was significantly affected by homogenization methods (Figure 3) and centrifugation speeds (Table S-3, Supporting information). Microsomes are vesicle-like artifacts reformed from ER membrane after tissue homogenization. We observed that for ER membrane markers, homogenization with hand-held rotary homogenizer provided higher recovery and enrichment than other tested methods. Moreover, 6,000 xg at low centrifugation speed resulted higher recovery (P<0.05) but equal enrichment (P>0.05) than other speeds for ER membrane markers in S1 fraction; ultra-centrifugation speed over 90,000 xg showed slightly higher recovery (P>0.05) but equal enrichment (P>0.05) than 60,000 xg. These results indicate that the factors that affect the vesicle formation (i.e. homogenization method) and isolation (i.e. centrifugation speed) will influence the recovery of microsomes. As there is currently no accepted standard operating procedure for isolation of microsomes, our results demonstrate a need for either a standardized isolation protocol (homogenization with hand-held rotary homogenizer, 6,000xg and 90,000xg for low- and ultra-centrifugation speed, respectively) or a well-validated method for evaluating the purity of these fractions. We recommend that the vendors of subcellular fractions (e.g., microsomes or cytosol) should ideally use such methods and provide IVIVE scaling factors, i.e., MPPGL and CPPGL with each lot of subcellular preparation.

Figure 3. Effect of four homogenization methods on the recovery (purple upward bars) and enrichment (orange downward bars) of organelle markers in different liver subcellular fractions.

A. Cytosolic and organelle luminal markers; B. Membrane-bound markers; C. Nuclear markers, and D. Cytoskeleton markers. Typical low- (9,000 xg) and ultra- (120,000 xg) centrifugation speeds were used. The data are shown as mean±S.E., n=3. HM1: Bead homogenizer (2 cycles); HM2: Bead homogenizer (3 cycles); HM3: Hand-held rotary homogenizer with plastic probes; HM4: Cryogenic grinding with mortar and pestle. H: Homogenate; S1: S9 fraction; P1: Pellet 1 (heavy membrane); S2: Cytosolic fraction; P2: Pellet 2; S3: Wash supernatant; P3: Microsomal fraction. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett post-test (HM1 as control). * P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001

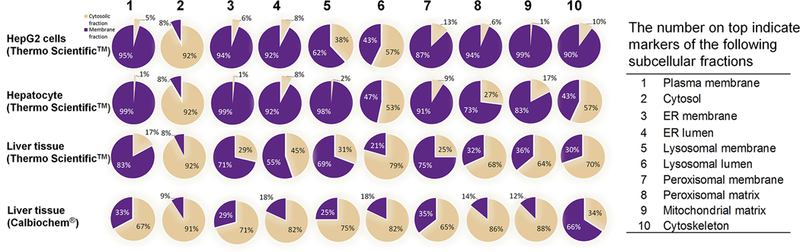

Quality of Total Membrane from Tissues vs. Cells

Relative recovery of organelle markers in the total membrane fraction was substantially different between hepatocytes vs. human liver tissue and moderately different between HepG2 cells vs. hepatocytes (Figure 4) using the commercial kits. Recovery of Na+/K+ ATPase, a frequently used plasma membrane marker, in HepG2 cells (95.4±0.6%, n=9) was slightly lower than that in hepatocytes (98.4±0.5%, n=5), but was significantly higher than in liver tissue (82.9±6.0%, n=4). Interestingly, the relative recovery of Na+/K+ ATPase in human liver total membrane fraction using Thermo Mem-PER™ Plus membrane protein extraction kit (82.9±6.0%, n=4) was significantly higher than that using the Calbiochem® total membrane extraction kit (32.8±1.9%, n=5). Relative recovery of cytosolic markers was consistent (~92%) between HepG2 cells and hepatocytes, hepatocytes and human liver tissue, and two membrane extraction kits (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relative recovery of organelle markers when using the Thermo Scientific™ or Calbiochem® membrane extraction kit in HepG2 Cells (n=9), hepatocytes (n=5) and human liver tissue (n=4–5).

Although plasma membrane can be cosedimented with ER and can be isolated by further centrifugation40,43–45, we found that plasma membrane marker (Na+K+ATPase) was recovered mostly (~80%) in the pellet of the first centrifugation (P1, nuclear fraction), but not in supernatant (S1, representing cytosol and microsomes). This is perhaps because of the adherence of nuclear basic proteins with negatively charged plasma membrane.39,42,43 Because plasma membrane isolation is susceptible to high technical or processing variability, most of the recent published reports on transporter proteomics focus on total membrane isolation using commercially available kits.44,45

It is essential for accurate IVIVE that in vitro clearance data generated using transporter expressing cell-lines is adjusted by relative expression factor (REF), i.e., the protein abundance in tissue (in vivo) vs. cells (in vitro), could significantly improve the accuracy of IVIVE. Like MPPGL and CPPGL, the plasma membrane protein per gram of tissue also requires use of a recovery factor (e.g., relative recovery, Equations 7–8) to correct for the losses when using the commercially available kits or in house prepared buffers to extract membrane transporters.

Detection of exosomal markers, subcellular organelle markers and drug metabolizing enzymes in exosomes isolated from human hepatocyte culture media

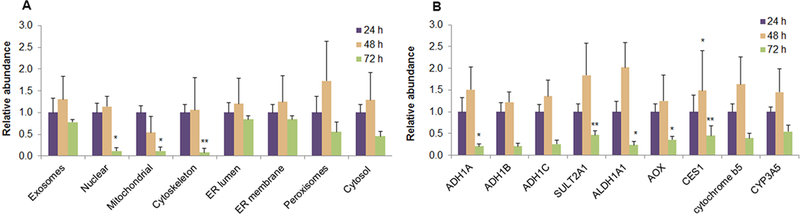

To further apply this method, we analyzed the exosomal specific markers, subcellular organelle markers and DMEs in exosomes isolated from media collected during sandwich-culture of human hepatocyte at 0–24, 24–48, and 48–72 hours. Although we used a high centrifugation speed (3,000 xg) for removing cell debris from the media, we do not expect contamination of intact or damaged cells in the exosomal fraction as the Exoquick kit selectively enriches exosome microvesicles. TGM2 and CD26 were used as markers of exosomes as reported elsewhere.30,31 Out of the organelle markers analyzed (Table 1), seven proteins were detected in high abundance in the isolated exosomes. These markers confirmed the presence of nucleus, mitochondria, peroxisomes, cytoskeleton, ER, peroxisomes and cytosol in the exosomal sample. The abundance of nuclear (lamin B1), mitochondrial (Hsp60) and cytoskeleton (vimentin and desmin) markers in media from 48–72 hour culture were significantly lower (P<0.05) than in 0–24 hour media (Figure 5) perhaps due to increased cell viability in longer culture. Protein abundance of thirteen DMEs (Table S-2, Supporting Information), including cytosol-, ER membrane- or ER lumen-expressed enzymes, in the exosomal sample were also determined with a previously developed method.46 Nine DMEs including ADH1A/1B/1C, ALDH1A1, sulfotransferase 2A1 (SULT2A1), AO, CES1, and cytochrome b5 and CYP3A5, were detected but at lower abundance in the isolated exosomes from 48–72 hour media when compared to 0–24 hour media (Figure 5). Exosomal proteomics has recently shown promises for diagnostic and therapeutic applications, yet validation of exosomes remains a critical issue. Therefore, the proteomics method present in this manuscript could be applied to investigate composition of exosomes.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of markers representing exosomes and subcellular organelles (A) and drug metabolizing enzymes (B) in human hepatocyte Culture media collected at 24, 48 and 72 hours in sandwich culture (mean±S.E., n=4). Detected exosomal markers were: TGM2 and CD26. Different organelles were characterized by following proteins: Nuclear (Lamin B1), mitochondrial (Hsp60), cytoskeleton (Vimentin and Desmin), ER membrane (NADPH CYP450 reductase), ER lumen (Calreticulin), peroxisomes (Catalase), and cytosol (Hsp-90 beta and LDH-H). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 indicates statistically significant variation which was analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test (24hours as control).

CONCLUSIONS

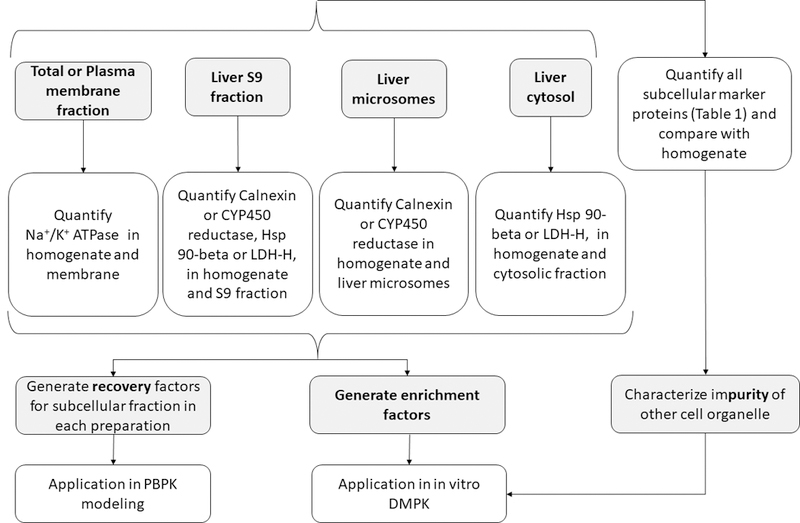

Technical variability in activity and protein quantification of DMEs or transporters is generally unavoidable when subcellular in vitro models are used in these studies.46,47 With respect to protein quantification, such variability could be significantly reduced when DMEs and transporters are quantified in total tissue homogenate.47 However, the use of tissue homogenate results in significantly poor signal-to-noise ratio in protein quantification and interference in enzyme activity assays. Alternatively, the protein abundance can be scaled by recovery factors to per gram of tissue. We presented here a targeted and cost-effective LC-MS/MS proteomics-based strategy to characterize subcellular fractions used in drug metabolism and transport studies (Figure 6). This strategy can be used to estimate recovery, enrichment, and purity of subcellular fractions efficiently and cost-effectively. With this strategy, we i) successfully estimated MPPGL and CPPGL for drug metabolism studies, ii) identified the source of contamination in microsomes and cytosol, iii) elucidated localization of non-CYP450 enzymes in subcellular fractions, and iv) demonstrated the differential recovery of membrane markers between tissue and cell samples using total membrane kits. The strategy was further applied to characterize the composition of exosomes collected from human hepatocyte culture medium. Moreover, we propose this method for the routine use as a quality control during subcellular isolation. Because relative and absolute quantification will be equally informative, we recommend the cost-effective relative quantification for this purpose. Thus, the proteomics method presented in this manuscript could be applied to validate the quality of microsomal, membrane and exosomal preparation.

Figure 6.

Proposed strategy for characterization of recovery, enrichment and purity of subcellular fractions used as in vitro models in drug metabolism and transport studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by grants from NIH (R01-HD081299), Genentech and UWRAPT. Meijuan Xu was supported by the Grant from China Clinical Evaluation Research Institute (Grant No. KK11–1). The authors thank Mathew Karasu and Dr. Deepak Kumar Bhatt for assistance with sample preparation and exosomal method development, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supplementary Experimental Procedure

REFERENCES

- (1).Rostami-Hodjegan A; Tucker GT Simulation and prediction of in vivo drug metabolism in human populations from in vitro data. Nature reviews. Drug Discovery. 2007, 6, 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Barter ZE; Bayliss MK; Beaune PH; Boobis AR; Carlile DJ; Edwards RJ; Houston JB; Lake BG; Lipscomb JC; Pelkonen OR; Tucker GT; Rostami-Hodjegan A Scaling factors for the extrapolation of in vivo metabolic drug clearance from in vitro data: reaching a consensus on values of human microsomal protein and hepatocellularity per gram of liver. Current Drug Metabolism. 2007, 8, 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Barter ZE; Chowdry JE; Harlow JR; Snawder JE; Lipscomb JC; Rostami-Hodjegan A Covariation of Human Microsomal Protein Per Gram of Liver with Age: Absence of Influence of Operator and Sample Storage May Justify Interlaboratory Data Pooling. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2008, 36, 2405–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Pryde DC; Dalvie D; Hu Q; Jones P; Obach RS; Tran TD Aldehyde oxidase: an enzyme of emerging importance in drug discovery. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010, 53, 8441–8460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Argikar UA; Potter PM; Hutzler JM; Marathe PH Challenges and Opportunities with Non-CYP Enzymes Aldehyde Oxidase, Carboxylesterase, and UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase: Focus on Reaction Phenotyping and Prediction of Human Clearance. The AAPS Journal. 2016, 18, 1391–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kumar V; Nguyen TB; Toth B; Juhasz V; Unadkat JD Optimization and Application of a Biotinylation Method for Quantification of Plasma Membrane Expression of Transporters in Cells. The AAPS Journal. 2017, 19, 1377–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Borlak J; Klutcka T Expression of basolateral and canalicular transporters in rat liver and cultures of primary hepatocytes. Xenobiotica. 2004, 34, 935–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Harwood MD; Achour B; Neuhoff S; Russell MR; Carlson G; Warhurst G; Rostami-Hodjegan A In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation Scaling Factors for Intestinal P-glycoprotein and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein: Part II. The Impact of Cross-Laboratory Variations of Intestinal Transporter Relative Expression Factors on Predicted Drug Disposition. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2016, 44, 476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kamiie J; Ohtsuki S; Iwase R; Ohmine K; Katsukura Y; Yanai K; Sekine Y; Uchida Y; Ito S; Terasaki T Quantitative atlas of membrane transporter proteins: development and application of a highly sensitive simultaneous LC/MS/MS method combined with novel in-silico peptide selection criteria. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008, 25, 1469–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wu JB; Shao C; Li X; Li Q; Hu P; Shi C; Li Y; Chen YT; Yin F; Liao CP; Stiles BL; Zhau HE; Shih JC; Chung LW Monoamine oxidase A mediates prostate tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014, 124, 2891–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Tabuchi M; Tanaka N; Nishida-Kitayama J; Ohno H; Kishi F Alternative splicing regulates the subcellular localization of divalent metal transporter 1 isoforms. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002, 13, 4371–4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Harwood MD; Russell MR; Neuhoff S; Warhurst G; Rostami-Hodjegan A Lost in centrifugation: accounting for transporter protein losses in quantitative targeted absolute proteomics. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2014, 42, 1766–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Scotcher D; Billington S; Brown J; Jones CR; Brown CDA; Rostami-Hodjegan A; Galetin A Microsomal and Cytosolic Scaling Factors in Dog and Human Kidney Cortex and Application for In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation of Renal Metabolic Clearance. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2017, 45, 556–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Harwood MD; Achour B; Russell MR; Carlson GL; Warhurst G; Rostami-Hodjegan A Application of an LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of human intestinal transporter proteins absolute abundance using a QconCAT technique. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2015, 110, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bonifati V; Rizzu P; van Baren MJ; Schaap O; Breedveld GJ; Krieger E; Dekker MC; Squitieri F; Ibanez P; Joosse M; van Dongen JW; Vanacore N; van Swieten JC; Brice A; Meco G; van Duijn CM; Oostra BA; Heutink P Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003, 299, 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Grover A; Oshima RG; Adamson ED Epithelial layer formation in differentiating aggregates of F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1983, 96, 1690–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Apte MV; Haber PS; Darby SJ; Rodgers SC; McCaughan GW; Korsten MA; Pirola RC; Wilson JS Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 1999, 44, 534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yang SH; Liu R; Perez EJ; Wen Y; Stevens SM Jr.; Valencia T; Brun-Zinkernagel AM; Prokai L; Will Y; Dykens J; Koulen P; Simpkins JW Mitochondrial localization of estrogen receptor beta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004, 101, 4130–4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Alver RC; Chadha GS; Gillespie PJ; Blow JJ Reversal of DDK-Mediated MCM Phosphorylation by Rif1-PP1 Regulates Replication Initiation and Replisome Stability Independently of ATR/Chk1. Cell Reports. 2017, 18, 2508–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Brunner G; Bygrave FL Microsomal marker enzymes and their limitations in distinguishing the outer membrane of rat liver mitochondria from the microsomes. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1969, 8, 530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sinai AP; Webster P; Joiner KA Association of host cell endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria with the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole membrane: a high affinity interaction. Journal of Cell Science. 1997, 110 ( Pt 17), 2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Michalak M; Corbett EF; Mesaeli N; Nakamura K; Opas M Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. The Biochemical Journal. 1999, 344 Pt 2, 281–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yu L; Wan F; Dutta S; Welsh S; Liu Z; Freundt E; Baehrecke EH; Lenardo M Autophagic programmed cell death by selective catalase degradation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006, 103, 4952–4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kumaresan V; Bhatt P; Palanisamy R; Gnanam A; Pasupuleti M; Arockiaraj J A murrel cysteine protease, cathepsin L: bioinformatics characterization, gene expression and proteolytic activity. Biologia. 2014, 69, 1336–9563. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kaminskyy V; Zhivotovsky B Proteases in autophagy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012, 1824, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ju X; Yan Y; Liu Q; Li N; Sheng M; Zhang L; Li X; Liang Z; Huang F; Liu K; Zhao Y; Zhang Y; Zou Z; Du J; Zhong Y; Zhou H; Yang P; Lu H; Tian M; Li D, et al. Neuraminidase of Influenza A Virus Binds Lysosome-Associated Membrane Proteins Directly and Induces Lysosome Rupture. Journal of vVirology. 2015, 89, 10347–10358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schmerk CL; Duplantis BN; Howard PL; Nano FE A Francisella novicida pdpA mutant exhibits limited intracellular replication and remains associated with the lysosomal marker LAMP-1. Microbiology. 2009, 155, 1498–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chen D; Sun Y; Wei Y; Zhang P; Rezaeian AH; Teruya-Feldstein J; Gupta S; Liang H; Lin HK; Hung MC; Ma L LIFR is a breast cancer metastasis suppressor upstream of the Hippo-YAP pathway and a prognostic marker. Nature Medicine. 2012, 18, 1511–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Faff-Michalak L; Albrecht J Changes in the cytoplasmic (lactate dehydrogenase) and plasma membrane (acetylcholinesterase) marker enzymes in the synaptic and nonsynaptic mitochondria derived from rats with moderate hyperammonemia. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology. 1993, 18, 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zhu L; Qu XH; Sun YL; Qian YM; Zhao XH Novel method for extracting exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014, 20, 6651–6657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Masyuk AI; Masyuk TV; Larusso NF Exosomes in the pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapeutics of liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology. 2013, 59, 621–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Prasad B; Unadkat JD Optimized approaches for quantification of drug transporters in tissues and cells by MRM proteomics. The AAPS Journal. 2014, 16, 634–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bhatt DK; Prasad B Critical Issues and Optimized Practices in Quantification of Protein Abundance Level to Determine Interindividual Variability in DMET Proteins by LC-MS/MS Proteomics. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2018, 103, 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Boberg M; Vrana M; Mehrotra A; Pearce RE; Gaedigk A; Bhatt DK; Leeder JS; Prasad B Age-Dependent Absolute Abundance of Hepatic Carboxylesterases (CES1 and CES2) by LC-MS/MS Proteomics: Application to PBPK Modeling of Oseltamivir In Vivo Pharmacokinetics in Infants. Drug Metab Dispos. 2017, 45, 216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Billington S; Ray AS; Salphati L; Xiao G; Chu X; Humphreys WG; Liao M; Lee CA; Mathias A; Hop C; Rowbottom C; Evers R; Lai Y; Kelly EJ; Prasad B; Unadkat JD Transporter Expression in Noncancerous and Cancerous Liver Tissue from Donors with Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Chronic Hepatitis C Infection Quantified by LC-MS/MS Proteomics. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2018, 46, 189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lipscomb JC; Teuschler LK; Swartout JC; Striley CA; Snawder JE Variance of Microsomal Protein and Cytochrome P450 2E1 and 3A Forms in Adult Human Liver. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods. 2003, 13, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Huber LA; Pfaller K; Vietor I Organelle proteomics: implications for subcellular fractionation in proteomics. Circulation Research. 2003, 92, 962–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Satoh T; Hosokawa M Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chemico-biological Interactions. 2006, 162, 195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wisniewski JR; Wegler C; Artursson P Subcellular fractionation of human liver reveals limits in global proteomic quantification from isolated fractions. Analytical Biochemistry. 2016, 509, 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wieckowski MR; Giorgi C; Lebiedzinska M; Duszynski J; Pinton P Isolation of mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nature Protocols. 2009, 4, 1582–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cubitt HE; Houston JB; Galetin A Prediction of human drug clearance by multiple metabolic pathways: integration of hepatic and intestinal microsomal and cytosolic data. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2011, 39, 864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Itzhak DN; Davies C; Tyanova S; Mishra A; Williamson J; Antrobus R; Cox J; Weekes MP; Borner GHH A Mass Spectrometry-Based Approach for Mapping Protein Subcellular Localization Reveals the Spatial Proteome of Mouse Primary Neurons. Cell Reports. 2017, 20, 2706–2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Itzhak DN; Tyanova S; Cox J; Borner GH Global, quantitative and dynamic mapping of protein subcellular localization. eLife. 2016, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Wegler C; Gaugaz FZ; Andersson TB; Wisniewski JR; Busch D; Groer C; Oswald S; Noren A; Weiss F; Hammer HS; Joos TO; Poetz O; Achour B; Rostami-Hodjegan A; van de Steeg E; Wortelboer HM; Artursson P Variability in Mass Spectrometry-based Quantification of Clinically Relevant Drug Transporters and Drug Metabolizing Enzymes. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2017, 14, 3142–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Harwood MD; Neuhoff S; Carlson GL; Warhurst G; Rostami-Hodjegan A Absolute abundance and function of intestinal drug transporters: a prerequisite for fully mechanistic in vitro-in vivo extrapolation of oral drug absorption. Biopharmaceutics and Drug Disposition. 2013, 34, 2–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Vrana M; Whittington D; Nautiyal V; Prasad B Database of Optimized Proteomic Quantitative Methods for Human Drug Disposition-Related Proteins for Applications in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology. 2017, 6, 267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Achour B; Al Feteisi H; Lanucara F; Rostami-Hodjegan A; Barber J Global Proteomic Analysis of Human Liver Microsomes: Rapid Characterization and Quantification of Hepatic Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2017, 45, 666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.