Abstract

The past few years have resulted in an increased awareness and recognition of the prevalence and roles of intrinsically disordered proteins and protein regions (IDPs and IDRs, respectively) in synaptic vesicle trafficking and exocytosis and in overall synaptic organization. IDPs and IDRs constitute a class of proteins and protein regions that lack stable tertiary structure, but nevertheless retain biological function. Their significance in processes such as cell signaling is now well accepted, but their pervasiveness and importance in other areas of biology are not as widely appreciated. Here, we review the prevalence and functional roles of IDPs and IDRs associated with the release and recycling of synaptic vesicles at nerve terminals, as well as with the architecture of these terminals. We hope to promote awareness, especially among neuroscientists, of the importance of this class of proteins in these critical pathways and structures. The examples discussed illustrate some of the ways in which the structural flexibility conferred by intrinsic protein disorder can be functionally advantageous in the context of cellular trafficking and synaptic function.

Keywords: intrinsically disordered protein, neurotransmitter release, lipid vesicle, protein folding, membrane trafficking, α-synuclein, complexin, membraneless organelles, phase transitions, synaptic vesicles

Introduction

A basic tenet of cell biology is that the eukaryotic cell is compartmentalized into discrete membrane-enclosed organelles and that cellular compartmentalization is critical for biological function. Trafficking between cellular compartments is achieved in part through membrane-enclosed vesicles that bud from a source membrane, travel through the cell, and fuse specifically with a given target membrane. Neurons present interesting and unique challenges for these types of processes. Lengthy axonal and dendritic processes necessitate long-distance trafficking in neurons. In addition, in contrast to the more ubiquitous and continuous nature of vesicular trafficking elsewhere in the cell, synaptic communication between neurons requires highly-localized and precisely-timed release of neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft through fusion of the synaptic vesicle with the plasma membrane. This process is highly regulated by a number of accessory proteins (1–5), some of which are intrinsically disordered or contain functionally critical disordered regions. Accordingly, intrinsically disordered proteins and regions play critical roles in synaptic transmission.

Protein structure exists as a continuum, with folded, ordered, and well-structured proteins and domains at one extreme and flexible, dynamic, and intrinsically disordered proteins and regions (IDPs2 and IDRs, respectively) at the other (see a recent review by Burger et al. (6) for a discussion of the term “disordered” versus “unstructured”). This review begins with a brief summary of biophysical properties of IDPs and their interactions before discussing a number of notable examples of how intrinsic disorder contributes to vesicular trafficking in general. We then focus on structural disorder within a number of proteins critical for synaptic function, especially synaptic vesicle release and recycling. Finally, we close with a discussion of the potential role of IDP/IDR-mediated phase transitions and membrane-less organelles in the organization of key elements of the synapse.

Unique IDP properties confer conformational and functional flexibility

The primary sequences of IDPs contain a high proportion of charged residues, with few hydrophobic amino acids (7, 8). Although IDPs feature relatively simple primary sequences, their inability to spontaneously fold into a unique three-dimensional structure leads to great structural complexity. Charge content and patterning within IDP sequences alter the extent of chain collapse, and the sequence composition determines how IDPs respond to external factors like ionic strength and temperature (9). IDPs usually show relatively flat, free energy landscapes, with local minima separated by low barriers, and they tend to rapidly fluctuate between different disordered conformations (10).

Conformational flexibility allows IDPs to interact with other macromolecules in a variety of ways. Indeed, IDPs can be promiscuous binders capable of interacting not only with multiple proteins (which may be other IDP/IDRs or structured proteins/domains), but also with lipid membranes or nucleic acids. IDP interactions often involve folding of the IDP/IDR, but folding upon binding is not an absolute requirement (8, 9, 11). IDPs are thought to engage their targets through conformational selection or induced fit, although these are not mutually exclusive, and both are likely to occur in different contexts (12). In conformational selection, some subset of the IDP structural ensemble adopts a conformation appropriate for binding, and the partner subsequently interacts with this preformed structure. In induced fit, binding precedes folding via an initial encounter complex (7, 9).

It is not surprising, perhaps, that IDPs often function in signaling networks as hub proteins that integrate multiple signals to link multiple signaling pathways (7, 8, 11). IDP/protein interactions tend to be of low affinity yet high specificity, a feature that is often coupled to regulatory functions within signaling networks: the interactions can be easily and rapidly turned “on” or “off” as required (7–9). In some cases, IDP/IDRs play critical roles in multivalent binding events leading to macromolecular phase transitions that contribute to the formation of membrane-less organelles.

Importantly, these varied interactions can often be readily modulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) of the IDP/IDR (11, 13). Indeed, an unfolded peptide chain is typically more accessible to modifying enzymes. PTMs change the physicochemical properties of the primary sequence; this produces a variety of structural changes, which then leads to alteration and expansion of IDP function. Specifically, PTMs can alter a given protein's steric, hydrophobic, or electrostatic properties, can stabilize, destabilize, or induce local structure, and can inhibit or enhance long-range tertiary contacts. PTMs alter the energy landscape and resultant conformational ensemble of the IDP, and they modulate interactions with other biomolecules (8, 9, 11, 14).

Structural disorder in vesicle trafficking

The trafficking of synaptic vesicles is a specialized case of cellular trafficking, which in general requires that vesicles carrying the appropriate cargo bud from a source membrane, travel in the appropriate direction, and then fuse with the proper cellular target. It is therefore relevant to examine the ways in which structural disorder may contribute to general vesicle trafficking pathways before examining contexts that are more specific to trafficking at the synapse. Using primary sequence analysis, Pietrosemoli et al. (15) examined protein disorder in cellular trafficking pathways such as clathrin-mediated endocytosis and transport between the ER and Golgi mediated by COPI (Golgi to ER) and COPII (ER to Golgi) coat proteins. They found that proteins associated with enzymatic activity and proteins that function as adaptors for vesicle cargo featured especially high degrees of disorder.

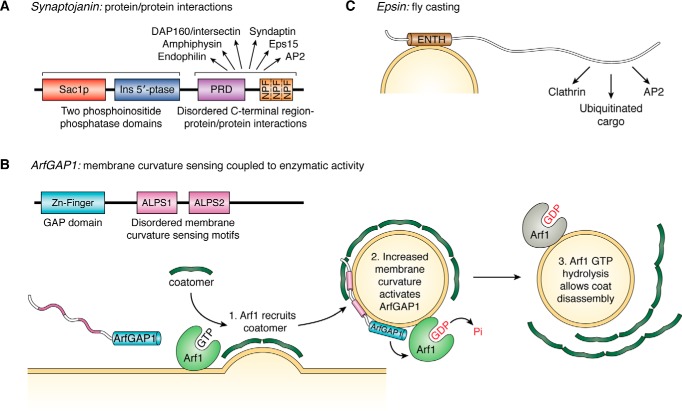

Long disordered regions mediating protein/protein interactions were often found adjacent to structured catalytic domains (15). Synaptojanins, for example, contain three distinct domains: an N-terminal inositol phosphatase domain; a central inositol phosphatase domain; and a disordered C-terminal domain featuring a proline-rich domain and three asparagine–proline–phenylalanine (NPF) repeats (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal domain interacts with other proteins involved in endocytosis, including the AP2 adaptor complex, amphiphysin, endophilin, DAP160/intersectin, syndaptin, and Eps15 (16). Importantly, synaptojanin-1 is a synapse-specific family member that plays a critical role in the endocytosis of synaptic vesicles and is also mutated in some forms of familial Parkinson's disease (17).

Figure 1.

Intrinsically disordered structure confers a variety of functional advantages. A, disordered C-terminal region of synaptojanin, which consists of a proline-rich domain (purple) and an asparagine–proline–phenylalanine (NPF) repeat region (orange), allows it to interact with a number of other proteins. Synaptojanin also contains two N-terminal phosphoinositide phosphatase domains (noted as Sac1p and Ins 5′ptase, in red and blue, respectively). B, ArfGAP1 contains two disordered, membrane curvature-sensing ALPS motifs (pink) that selectively bind to highly-curved membranes. Curvature-selective membrane binding by these motifs appears coupled to activation of the zinc finger GAP domain (cyan), which facilitates Arf1 GTP hydrolysis and triggers disassembly of the COPI coat. The ArfGAP1 ALPS motifs adopt helical structure upon membrane binding. C, epsin N-terminal homology domain (ENTH, brown), selectively binds to curved membranes. The disordered epsin C terminus “fly-casts” to interact with varied proteins: its disordered structure increases the range at which it can bind to and capture necessary binding targets.

As another example, the GTPase-activating protein (GAP) ArfGAP1, which regulates the enzymatic activity of ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (Arf1), contains disordered amphipathic lipid-packing sensor (ALPS) motifs that bind to membranes and sense membrane curvature to contribute critically to COPI trafficking (18–23). During COPI vesicle biogenesis, GTP-bound Arf1 binds to organelle membranes and recruits coatomer, a large cytosolic complex that gathers cargo and assembles into a vesicle coat (19, 22, 23). Coat disassembly of mature vesicles requires GTP hydrolysis by Arf1, which is in turn stimulated by ArfGAP1 (24). The ArfGAP1 ALPS motifs bind avidly to small liposomes in an α-helical conformation, with membrane binding predominantly driven through insertion of a number of bulky hydrophobic residues on the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic helices (19, 21–23, 25, 26). Interestingly, the GTPase-stimulating activity of ArfGAP1 increases with increasing membrane curvature (20). This suggests a feedback loop (Fig. 1B): Arf1/COPI first induce membrane deformation and so enhance membrane curvature, which in turn stimulates ArfGAP1 activity, enhances Arf1 GTP hydrolysis, and leads to coat disassembly (23). Although COPI vesicles are not present at the synapse, ArfGAP1 provides an example of how IDP/membrane interactions contribute to vesicle trafficking. Additional synapse-specific examples are discussed further below.

An example of a disorder-containing adaptor protein is the Epsin family of proteins. Epsins contain a folded epsin N-terminal homology domain at their N terminus that interacts with membranes, whereas the rest of the protein is disordered (15). At their C termini, epsins contain binding sites for clathrin, AP2 adaptors, and ubiquitinated cargos (27). This modular architecture (Fig. 1C) allows epsin to link the membrane with other proteins involved in vesicle formation (28) and to thereby aid in cargo selection. Epsins may employ a fly-casting type mechanism (15), with a protein-binding site at one end of a disordered chain. The larger resulting hydrodynamic radius allows a binding module to explore a greater volume and thereby helps increase association rates (7, 29). Like synaptojanin-1, epsin-1 is thought to play a role in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis/recycling.

Intrinsically disordered SNARE proteins as the core membrane fusion machinery

The SNARE proteins (for SNAP receptor proteins, where SNAPs are soluble NSF attachment proteins, and NSF is the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor) are a superfamily of small proteins that mediate membrane fusion in all steps of cellular secretory pathways and that constitute the core membrane fusion machinery (30, 31). Humans contain 36 different SNARE proteins, which are found attached to membranes, often through a C-terminal transmembrane domain, although attachment via post-translational lipidation also occurs for some family members. SNAREs are often classified as v- or t-SNAREs depending on their localization to vesicles or to the target membrane, respectively. Membrane fusion events obviously are critical for synaptic vesicle exocytosis, where the most relevant SNAREs are the v-SNARE synaptobrevin-2 and the t-SNAREs syntaxin-1 and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25).

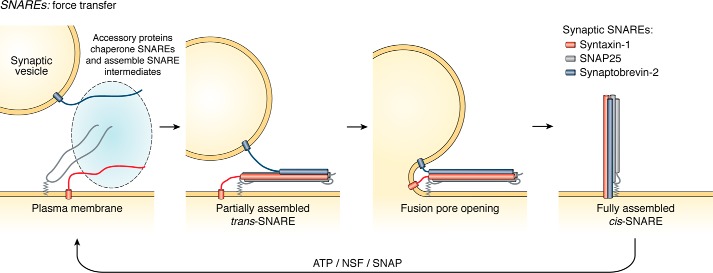

The SNARE motif is a conserved stretch of 60–70 amino acids featuring heptad repeats (30). Notably, free SNARE motifs are disordered in their free state both in vitro and in live cells (32–38). SNARE motifs localized to two closely apposed membranes can zipper in an N- to C-terminal direction into a parallel four-helix coiled coil termed the SNARE complex. The coiled-coil interface consists of 16 stacked layers of interacting side chains, mostly featuring hydrophobic interactions, with a central “0” layer that contains three highly-conserved glutamine residues and one highly-conserved arginine residue (SNAREs may also be classified as Qa-, Qb-, Qc-, and R-SNAREs depending on the identity of this residue) (30). The free energy released through the SNARE assembly process is thought to drive fusion of the two membranes, although precisely how the energetics of SNARE assembly are coupled to membrane fusion remains unclear. In one model, SNARE complex folding may subsequently propagate through the transmembrane domain to exert a mechanical force on fusing membranes (illustrated using the synaptic SNARE proteins in Fig. 2); this has yet to be definitively established, however (2, 39, 40). Regardless, SNAREs represent a clear example of how coupled binding and folding by a disordered region fulfills a critical cellular function. After assembly, the AAA ATPase NSF, along with SNAP proteins, disassembles post-fusion SNARE complexes to “recharge” the system with the necessary energy required for future rounds of fusion (31).

Figure 2.

SNARE proteins constitute a core membrane fusion machinery wherein a disorder-to-order transition is coupled to force transfer that induces membrane fusion. The SNARE proteins associated with synaptic vesicle exocytosis are highlighted here. Initially, syntaxin-1 (red) and SNAP-25 (gray) are anchored to the plasma membrane, whereas synaptobrevin-2 (blue) is anchored to synaptic vesicles. During synaptic vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane, the disordered SNARE motifs of these three proteins assemble into a stable four-helix bundle (with two helices contributed by SNAP-25). Although still incompletely understood, the energy of SNARE complex assembly is thought to drive membrane fusion, as the complex transitions from an initial partially assembled trans-SNARE complex (with SNAREs anchored in opposing membranes), through fusion pore opening, to a final fully assembled cis-SNARE complex (with all three SNAREs now in the plasma membrane). Subsequent to membrane fusion, the cis-SNARE complex is disassembled by NSF in an ATP-dependent fashion.

SNARE assembly is likely an ordered, sequential reaction involving delivery of the appropriate SNARE in the right condition, at the right place, and time (30). In addition, as noted above, SNARE assembly occurs through N- to C-terminal zippering, and this process can be frozen at intermediate stages by protein-binding partners (e.g. complexin, discussed below). Such intermediate species may include partially zippered SNARE complexes, binary and/or ternary SNARE complexes, or complexes containing SNARE protein(s) along with one or more non-SNARE–binding partners (2, 3, 30, 40, 41). Indeed, for proper assembly, SNAREs must interact with a number of other proteins, and in many cases these interactions involve some degree of SNARE folding. Thus, their structural flexibility likely allows the SNARE proteins to engage a variety of partners through discrete bound state conformations and in various multimeric states, a feat that is critical for their proper regulation and function.

Structural disorder within accessory proteins that regulate synaptic vesicle exocytosis

The three synaptic SNARE proteins alone are sufficient to drive some degree of membrane fusion in in vitro fusion assays. In vivo, however, their behavior is tightly regulated and modulated by a number of accessory proteins, including complexin, synaptotagmin (the calcium sensor that triggers action potential evoked exocytosis by coupling calcium influx to SNARE assembly), Munc18, Munc13, tomosyn, RIM proteins, RIM-binding proteins (RIM-BPs), Rab proteins, ELKS, α-Liprins, and Piccolo/Bassoon proteins (1, 2, 5, 40, 42–44). This extensive machinery utilizes abundant protein/protein and protein/membrane interactions to structurally and functionally organize active zones, specialized electron-dense presynaptic membrane-associated sites of synaptic vesicle exocytosis that appose post-synaptic densities (the reader is referred to Refs. 5, 38 for further information regarding active-zone proteins, composition, organization, and architecture). At active zones, synaptic vesicles are docked and primed adjacent to the requisite calcium channels so that evoked fusion can occur efficiently when required, with a tight and rapid (sub-millisecond) coupling between the influx of calcium that results from the arrival of an action potential and vesicle release (5, 40). SNAREs can also mediate low levels of spontaneous synaptic vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane, but for optimal action-potential–based inter-neuronal signaling, such spontaneous exocytosis must be kept to a minimum by regulatory proteins (45). Importantly, intrinsically disordered regions from a number of SNARE accessory/regulatory proteins play key functional roles within this extensive interaction network to help organize the active zone and optimize the synapse for rapid exocytosis.

Tomosyn

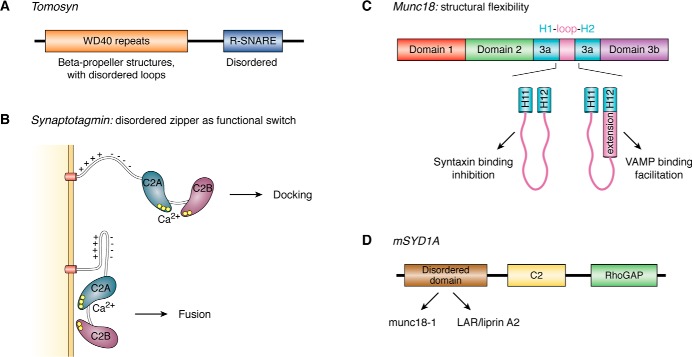

Tomosyn is a SNARE-binding presynaptic protein that is considered to be an inhibitor of synaptic vesicle release, possibly at the priming step. Tomosyn contains two conserved domains, including a C-terminal region with homology to the R-SNAREs, and an N-terminal WD40 repeat region (Fig. 3A). As with other SNAREs, the tomosyn SNARE motif is disordered in the free state, but it can dimerize with syntaxin-1 (46) or can compete with synaptobrevin-2 to form a ternary SNARE complex with syntaxin-1 and SNAP-25 (44). Interestingly, two unstructured loops in the WD40 domain contribute to SNAP-25 binding and ternary SNARE complex formation by tomosyn, but not to tomosyn/syntaxin-1 dimer formation (44). Through ternary SNARE complex formation, tomosyn can regulate synaptobrevin-2 binding to syntaxin-1 and SNAP-25, and this R-SNARE substitution mechanism may underlie the inhibition of exocytosis by tomosyn overexpression in PC12 cells (43). Alternatively, tomosyn binding to the SNARE motif of syntaxin-1 may displace Munc18 from syntaxin; it was proposed that tomosyn may activate syntaxin-1 and allow it to interact with synaptobrevin-2 (46).

Figure 3.

Functional mechanisms of disorder in synaptic proteins. A, tomosyn contains a disordered C-terminal R-SNARE domain (blue). Its N-terminal WD40 repeat domain (orange), which features β-propeller structures, contains unstructured loops necessary for a subset of tomosyn functions. B, segregation of positively and negatively charged residues within an unstructured region of synaptotagmin allows it to behave as a molecular zipper whose structural state modulates synaptotagmin function: in the open state, synaptotagmin contributes to vesicle docking, and in the zippered state, it facilitates membrane fusion. C, Munc18 contains an unstructured loop (pink) within domain 3a that allows helix 12 of this domain to shorten or extend and thereby toggle between syntaxin binding and inhibition of membrane fusion or synaptobrevin-2 binding and promotion of fusion, respectively. D, some mammalian homologs of synapse–defective-1 proteins contain a disordered domain (brown) that interacts with other proteins, including Munc18-1 and the LAR–Liprin A2 complex. They also contain a central C2 domain (yellow) and a C-terminal RhoGAP domain (green).

Synaptotagmin

Synaptotagmin-1 (Syt1) has been identified as a key calcium sensor linking a presynaptic membrane depolarization-induced calcium influx to evoked exocytosis. Syt1 contains an N-terminal transmembrane α-helix followed by two C2 domains, C2A and C2B, which bind three and two Ca2+ ions, respectively, through calcium-binding loops that can then interact with membranes. Syt1 thus interacts with phospholipid membranes in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Syt1 also interacts with SNAREs and can bind simultaneously to membranes and membrane-anchored SNARE complexes to form the so-called quaternary SNARE–synaptotagmin-1–Ca2+–phospholipid (SSCAP) complex (1). It is unclear, however, whether the synaptotagmin/SNARE interaction is mediated by a polybasic region on the side of the C2B domain (1, 47) or by a region of C2B opposite the calcium-binding loops containing two critical arginine residues (47–49). This complex could facilitate fusion by inducing negative membrane curvature, with the Syt1/membrane interaction serving to bring apposed membranes together. Alternatively, Syt1 may induce positive curvature in the plasma membrane. Interestingly, and similarly to complexin, Syt1 (and Syt2) also normally clamp spontaneous SV release, and the activating versus inhibitory functions of synaptotagmin are likely independent (40).

An intrinsically disordered region between the synaptotagmin transmembrane domain and C2A has been shown to be essential for both calcium-independent vesicle docking, and calcium-dependent fusion pore opening (50). This region interacts with lipid membranes, and it modulates calcium binding within C2A, consistent with the idea that IDRs often influence adjacent folded domains (51). Interestingly, this IDR contains an N-terminal part rich in basic amino acids and a C-terminal part rich in acidic amino acids. This segregation of charge seems to result in a molecular zipper that contributes to fusion pore opening when closed but that facilitates vesicle docking when open (Fig. 3B); shortening the linker or cross-linking it into a folded conformation reduces docking but enhances fusion pore opening. These observations led to a model whereby this disordered linker region extends to facilitate vesicle docking (perhaps through a sort of fly-casting mechanism) but then folds in a way that facilitates fusion pore opening (50).

Finally, although C2A is a folded domain of synaptotagmin (52), it appears to be weakly stable. It was proposed that this marginal stability allows C2A to adopt and fluctuate between multiple conformational states with unique functions and behaviors, which endow synaptotagmin with great functional diversity (52).

Munc18

SM proteins (for Sec1/Munc18-like proteins) are critical partners in all SNARE-mediated membrane fusion events, although how they contribute to membrane fusion remains enigmatic (1, 2). At least three primary functions have been proposed for Munc18-1 (53). 1) It acts as a chaperone for syntaxin-1 that facilitates proper syntaxin-1 localization and expression. Indeed, in contrast to its apparently essential facilitatory role in synaptic vesicle fusion, Munc18 was originally shown to bind to the “closed” conformation of syntaxin in a way that would be expected to inhibit membrane fusion (with the N-terminal Habc domain of syntaxin folded back onto the SNARE domain). In this conformation, Munc18 stabilizes syntaxin-1 and facilitates transport of syntaxin-1 to the plasma membrane. 2) Munc18 facilitates priming via promotion of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in several different ways. Munc18 was later shown to bind to the syntaxin N-peptide (at the very N terminus) in a conformation that is compatible with SNARE complex assembly. It also binds syntaxin–1-SNAP-25 heterodimers and could thus facilitate or nucleate SNARE complex assembly. In addition to binding t-SNAREs like syntaxin, it can also simultaneously bind to v-SNAREs, possibly aligning them so as to facilitate the initial steps of SNARE complex formation (54, 55). Furthermore it may enable lipid mixing either directly or through lipid destabilization, and it may help to spatially and asymmetrically organize assembled SNARE complexes around the fusion site by preventing diffusion of the bulky Munc18–SNARE complex assembly to the center of the synaptic vesicle/plasma membrane intermembrane space. 3) Finally, it has been suggested that Munc18 contributes to docking of large dense-core vesicles (1, 2, 31, 53).

The Munc18 sequence can be subdivided into domains 1, 2, 3a, and 3b (Fig. 3C) (56). In the Munc18/syntaxin-1 binary structure, closed syntaxin interacts with a Munc18 cavity formed by domains 1 and 3 (55). Domain 1 plays an important role in the syntaxin chaperoning function of Munc18 and so-called “chaperoning mutants” can be generated within this domain (53). In contrast, domain 3a appears to play a role in the priming function of Munc18, and mutations in this domain can impair priming (“priming mutants”) (53). Interestingly, in the Munc18–syntaxin-1 complex, two anti-parallel helices in domain 3a, helices 11 and 12, are connected by a 21-residue bent hairpin loop with an irregular conformation. Eight residues of this loop are disordered as they do not appear in crystal structures, and the remaining visible residues have high B-factors, indicating increased mobility. This domain 3a loop is essential for exocytosis from PC12 cells but is not required for syntaxin-1A transport (56). In structures of Munc18 bound to closed syntaxin, helix 12 is relatively short (57), but in structures bound to the syntaxin N peptide helix 12 forms a longer, extended helix (58). Mutations that bias extension of helix 12 increase binding to synaptobrevin-2 and enhance priming by Munc18, suggesting that the extended helix 12 provides a template for SNARE assembly (54, 55). The disordered residues in the loop connecting helices 11 and 12 thus appear to contribute to the structural flexibility necessary for Munc18 to pivot between the requisite structures for its inhibitory and facilitatory functions (Fig. 3C).

Mouse synapse-defective 1A

Synapse–defective-1 proteins, including mSYD1A (mouse synapse–defective-1A), regulate presynaptic differentiation. Many SYD-1 proteins contain a RhoGAP domain and a PDZ domain that links SYD-1 to the surface receptor neurexin (a presynaptic protein that helps connect neurons across the synaptic cleft); these domains may mediate SYD-1 function. Syd1 mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans perturb proper localization of active-zone components and synaptic vesicles (59). The first mammalian SYD-1 ortholog was recently identified in mice (mSYD1A) and shown to contribute to vesicle docking, insofar as mSYD1A knockout hippocampal synapses contain fewer docked vesicles and reduced synaptic transmission. Interestingly, mSYD1 function depends on a multifunctional intrinsically disordered domain (Fig. 3D). In contrast to invertebrate SYD-1, mSYD1A lacks the PDZ domain and contains an active RhoGAP domain (which is inactive in invertebrates). mSYD1A RhoGAP activity is regulated through intramolecular interactions that include the disordered domain. Furthermore, the disordered domain acts as an interaction module capable of interacting with multiple proteins, including Munc18-1 as well as a LAR–LiprinA2 complex. The protein/protein interactions mediated by this disordered domain likely contribute to organization of the active zone and to proper vesicle docking (59).

The examples above illustrate both the importance of disordered protein regions in the regulation of SNARE-mediated synaptic vesicle exocytosis and some of the mechanisms involved. Disordered regions can compete with other disordered binding motifs for binding partners, can served as a platform for recruiting multiple interaction partners to provide scaffolding/organizing functions, and can undergo highly-specific or less well-defined conformational transitions that regulate function and activity. The diversity of their modes of action contributes to the ubiquitous involvement of disordered proteins in various biological processes, but also constitutes a challenge in uncovering and understanding their functional roles.

Protein/lipid interactions at the synapse: functional significance of membrane binding by IDPs

A number of IDPs interact with lipid membranes. This interaction can be driven by partitioning of hydrophobic residues into the membrane as well as by electrostatic interactions between charged protein residues and lipid headgroups (60–62). As with IDP/protein interactions, in many cases the IDP folds upon membrane binding, often into an amphipathic membrane-binding helix (25). Some IDPs instead remain unfolded in the membrane-bound state, as is the case, for example, with the MARCKS peptide (a membrane-binding region of the myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate, or MARCKS, protein, which can sequester phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in the membrane and regulate phospholipase C signaling) (63). The functional roles of IDP/membrane binding are not always clear; in some cases, it may contribute to proper cellular localization (18, 21, 23, 64), and in others the IDP/membrane interaction may actively remodel the membrane in functionally significant ways (65). A number of intrinsically disordered membrane-binding proteins function as membrane curvature sensors and membrane curvature generators. Above, ArfGAP1 was cited as an example of how membrane curvature-selective binding contributes to IDP function in the context of vesicle trafficking. This type of behavior is observed at the synapse as well, as will be discussed for two intrinsically disordered pre-synaptic membrane curvature sensors, α-synuclein and complexin.

Complexin

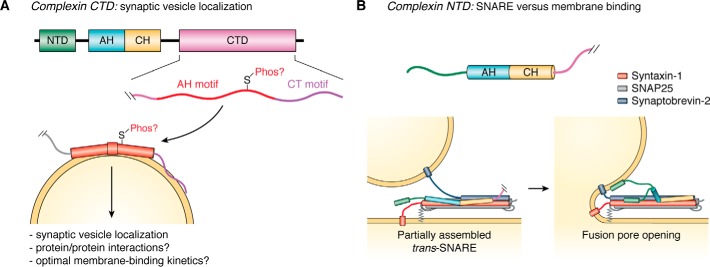

Complexins form a family of small, highly-charged, and highly-conserved cytoplasmic proteins that have emerged as key regulators of SNARE-mediated synaptic vesicle exocytosis (42, 66–70). Although complexins are intrinsically disordered in their free state, they can directly interact with assembled and/or assembling SNARE complexes through a central α-helical domain that binds in an antiparallel fashion in the groove formed between syntaxin-1 and synaptobrevin-2 (71–73). Complexins feature four different domains with discrete functions in synaptic vesicle exocytosis, including a facilitatory N-terminal domain (NTD), an inhibitory accessory helix/accessory domain (AH), the above-mentioned essential central helix (CH), and a C-terminal domain (CTD) that can bind lipid membranes and that may inhibit or facilitate exocytosis (42). Notably, although the NTD and CTD are highly disordered, the CH and AH domains feature a substantial population of helical structure, even in the absence of any intermolecular interaction (71, 74). Such residual secondary structure elements, sometimes denoted as SLiMs (short linear motifs), MoRFs (molecular recognition features), or PreSMos (prestructured motifs) (75–77), often promote or facilitate the binding of IDPs/IDRs to their interaction partners.

Complexin expression levels are altered in a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Although such expression level changes may not be causal in these disorders, they could contribute to their corresponding symptomatology (78). Recently, homozygous mutations in the complexin CTD have been identified through whole exome sequencing in patients with severe infantile myoclonic epilepsy and intellectual disability (79). Complexin-1 and -2 double knockout mice die shortly after birth, likely from deficits in synaptic transmission in multiple neuronal networks (42, 80). Single knockout of complexin-1 or -2 is not lethal but causes neurological impairments (80–84). Complexin appears to either promote or inhibit vesicle fusion depending on the experimental approach used; complexin also appears to differentially affect action potential-evoked versus spontaneous vesicle exocytosis and to do so in a species-dependent fashion. Overall, a general consensus has emerged that complexins inhibit spontaneous release while facilitating synchronous, evoked release (42, 80). The detailed mechanisms by which complexin fulfills these distinct functions, however, remain unclear. Regardless, complexin's inhibitory and facilitatory functions appear to be distinct and separable and so likely operate through discrete mechanisms (85–87). As noted above, the four complexin domains likely have discrete functions in vesicle exocytosis, and complexin domain function has been extensively dissected. Here, we focus on the highly-disordered NTD and CTD, while noting the importance of the structured CH and AH domains.

The complexin NTD has been reported to facilitate vesicle release (87–89). It is interesting to note that the structures of the SNARE bundle-bound complexin CH suggest that the NTD and AH domains will be situated in the region where trans-SNARE complexes insert into the membrane. In mouse neurons, mutation of the membrane insertion sequence of synaptobrevin-2 generated a similar phenotype to that of complexin knockout as assessed by electrophysiology. Together, these observations led to the hypothesis that although these two N-terminal regions of complexin fulfill discrete facilitatory (NTD) and inhibitory (AH) functions, together they control the force transfer from SNARE complexes to membranes during fusion (89). It is likely that complexin interacts with SNAREs in a variety of ways and that these varied interactions contribute to the dual functions of complexin. A recent study provided evidence for both cis- and trans-conformations of the complexin–SNARE complex. The cis-conformation, which may help to activate synchronous neurotransmitter release, required the N-terminal domain of complexin in addition to the accessory and central helices (90).

The first eight residues of complexin are necessary for the facilitatory function of the N-terminal domain (91). Although disordered when free in solution, the first ∼17 residues of the complexin N-terminal domain appear somewhat conserved across species and, when modeled as a helix, show potentially amphipathic helical character. Methionine 5 and lysine 6 within this region are particularly critical for the facilitation of evoked release (91). This amphipathic region has been suggested to potentially bind membranes (88, 89, 91, 92), although an initial NMR-based analysis showed no such NTD/membrane interaction (91). Instead, it was hypothesized that the NTD might bind to the C terminus of the SNARE complex (specifically between SNAP-25 and syntaxin-1) and, in so doing, either stabilize the SNARE complex and/or release the inhibitory function of complexin (91). Subsequent studies did, however, show a potential interaction between the N-terminal amphipathic region and lipid membranes; interestingly, NTD function did not require it to be covalently attached to the rest of complexin, and it could be functionally substituted by an unrelated hemagglutinin fusion peptide (92). Ultimately, the details of how the NTD and its membrane binding contribute to complexin function remain largely unclear (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Potential functions of the disordered C- and N-terminal domains of complexin. A, unstructured complexin C-terminal domain (pink) contributes to the inhibition of spontaneous synaptic vesicle exocytosis; it selectively binds to synaptic vesicles (yellow) through tandem membrane curvature-sensing motifs, termed the amphipathic helix motif (AH motif, red) and C-terminal motif (CT motif, purple). In worm complexin, the AH motif includes a π-bulge structure in the bound state, whereas the CT motif remains disordered. The AH motif also contains potential phosphorylation sites that may modulate membrane binding and thereby regulate complexin inhibitory function. Other complexin domains include the N-terminal domain (green), the accessory helix (cyan), and the central helix (orange). B, complexin N-terminal domain (green) facilitates synaptic vesicle fusion, either by binding to lipid membranes and/or by binding to the SNARE complex to displace the inhibitory accessory helix (cyan). The SNAREs, syntaxin-1, SNAP-25, and synaptobrevin-2, are shown in red, gray, and blue, respectively.

The intrinsically disordered CTD of complexin appears necessary for the inhibition of spontaneous SV fusion in worms (45, 64, 74), flies (85, 93–95), mice (96, 97), and in vitro fusion assays (87): elimination or perturbation of the CTD impairs complexin inhibitory function (96). The CTD may also, however, have some facilitatory function, based on observations in vitro (98, 99), and in C. elegans (45). Furthermore, complexin-1 enhances the on-rate of vesicle docking through interactions of the CH with SNAREs and of the CTD with the membrane (100). Notably, the aforementioned homozygous mutations to complexin observed in patients with severe infantile myoclonic epilepsy and intellectual disability could potentially perturb complexin/membrane interactions, especially given that one is a C-terminal truncation mutation. The impact of these mutations has not yet been formally assessed, however.

The CTDs of both mouse and worm complexin have been established by NMR as intrinsically disordered (71, 74), although the worm complexin CTD displays detectable residual helical structure in the free state (74). The CTDs of worm and mammalian complexin have been shown to interact with liposomes through a conserved amphipathic region, which in the worm protein corresponds to the location of residual helicity in the unbound state (74, 99, 101). The CTD/membrane interaction may contribute to inhibition and/or facilitation of synaptic vesicle fusion by the CTD. We previously established that the worm complexin CTD contains tandem lipid-binding motifs that together sense membrane curvature and selectively bind to more highly-curved membranes (74). A C-terminal motif rich in bulky hydrophobic residues and positively charged lysine residues initiates binding and likely remains unstructured in the membrane-bound state; an adjacent amphipathic motif adopts helical structure upon membrane binding, but only for highly-curved membrane surfaces (74). Mouse complexin also selectively binds to highly-curved membranes, suggesting a conserved role for membrane curvature sensing by the CTD (74, 101). The structure of membrane-bound mouse complexin has not, however, been as extensively characterized. The exact mechanisms by which membrane binding might contribute to function remain unclear. We and others have proposed that the CTD localizes complexin to synaptic vesicles (Fig. 4A), an interaction that is required for inhibition of spontaneous exocytosis by complexin; this interaction would be facilitated by the preferential binding of complexin to the highly-curved synaptic vesicle membrane (64, 74). Additionally, for worm complexin, formation of noncanonical π-helix structure in the CTD upon membrane binding appears to be required for optimal complexin inhibitory function (74, 102). This suggests a role for the CTD beyond membrane binding. It may, for example, mediate complexin protein/protein interactions, an idea supported by a recent report of potential CTD/SNARE interactions (103).

Finally, the impact that CTD PTMs may have on membrane association and/or protein interactions remains essentially uncharacterized. The CTD contains potentially phosphorylatable serine and threonine residues, and mutation of human complexin serine 115–one putative site for such phosphorylation–impaired the ability of complexin to stimulate liposome fusion in an in vitro assay, although membrane binding by these mutants was not examined (98). In flies, protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of (fly complexin) serine 126 is required for synaptic plasticity and growth. Phosphorylation of this residue occurs as a result of retrograde signaling following stimulation, and it impairs the ability of complexin to clamp spontaneous fusion. The resultant enhanced spontaneous release then contributes to activity-dependent synaptic growth (104).

Ultimately, a complete understanding of the function of the complexin CTD remains elusive, and the detailed mechanisms by which the CTD and CTD/membrane interactions exert their function remain unclear. Nonetheless, it provides a key example of how an intrinsically disordered region mediates a selective and functionally requisite interaction with the synaptic vesicle membrane. Future work will be required to tease out further details, including how PTMs alter CTD function and interactions. Overall, despite its small size, complexin features at least two distinct activities that are modulated in multiple ways by multiple regions, namely SNARE and synaptic vesicle binding allow complexin to clamp or facilitate exocytosis. Its intrinsically disordered character may play a key role in providing the flexibility required for carrying out opposing functions in different contexts utilizing different structures and interactions.

α-Synuclein

α-Synuclein is a small, soluble, and predominantly presynaptic protein that has been implicated in Parkinson's disease as well as other neurodegenerative “synucleinopathies.” Mutations in α-synuclein have been linked to familial forms of these diseases (105–112), and β-sheet–rich aggregated α-synuclein can be found in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, two pathological hallmarks of the synucleinopathies (113, 114). α-Synuclein structure, dynamics, function, and aggregation have been an extremely active area of research within the IDP field over the past 2 decades (115, 116). Here, we briefly review putative synuclein functions and then focus on how IDP/membrane interactions may contribute to these.

α-Synuclein has been implicated in synaptic plasticity (117) and learning (118), neurotransmitter release (119, 120), and synaptic vesicle pool maintenance (117, 121, 122), yet its precise function(s) remain elusive. The most widely accepted synuclein functions involve synaptic vesicle homeostasis and synaptic vesicle clustering, docking, fusion, and or recycling (115, 116, 119, 122–133). It has further been suggested that synuclein may also function as a molecular chaperone for synaptobrevin-2, the synaptic v-SNARE (119). Other putative functions of synuclein have also been proposed, including potential roles in fatty acid and lipid metabolism (134–146), dopamine synthesis and homeostasis (147–151), and prevention of membrane oxidation (152–155).

Synuclein can directly bind synaptic vesicles and appears to localize to their surface or proximity in vivo (118, 156–161). The N-terminal domain of α-synuclein has been clearly established as a membrane curvature sensor that folds into an amphipathic helix upon membrane binding and that displays enhanced binding to more highly-curved vesicles; binding is further enhanced by negatively charged lipids and by conical lipids (e.g. lipids with phosphatidylethanolamine headgroups) (162–167). Synuclein thus may be optimized to bind synaptic vesicles, although it clearly interacts with other membranes as well, including possibly the plasma membrane and mitochondrial membranes (115, 116, 133). Interestingly, synuclein can, in some contexts, actively induce membrane curvature to remodel lipid membranes; this could have functional significance for synaptic vesicle exocytosis, which requires alterations in membrane shape and curvature prior to membrane fusion (168–171).

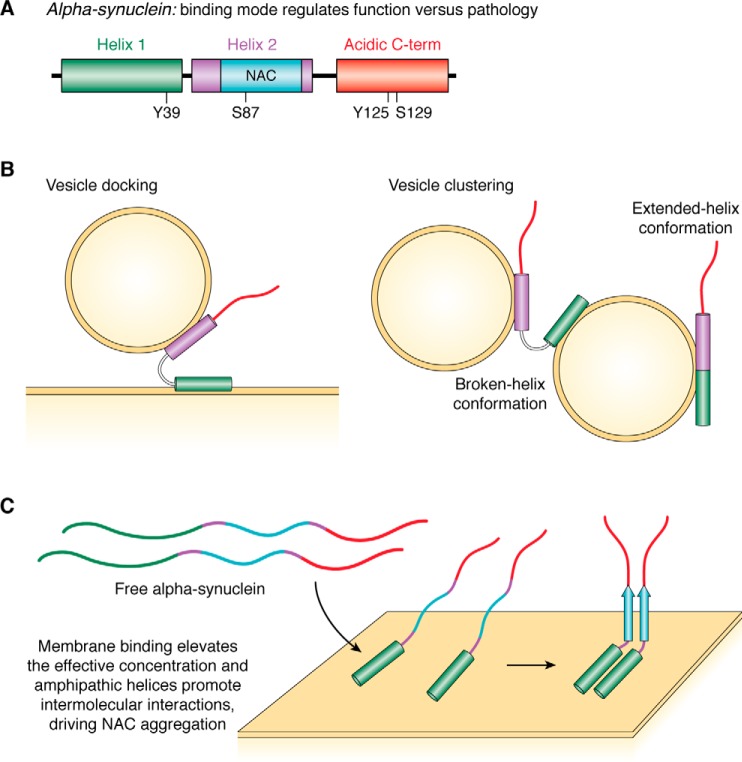

α-Synuclein is intrinsically unstructured in the free state (162, 172–175). Its N-terminal ∼100 residues constitute a lipid-binding domain (Fig. 5A) featuring seven imperfect 11-residue repeats that can adopt an amphipathic helical structure upon binding to detergent micelles or phospholipid vesicles (115, 116, 176, 177). The very N terminus of free N-terminally acetylated α-synuclein does exhibit some residual helical structure, as evidenced by NMR-derived carbon secondary shifts (178–181). This transient helical structure appears to facilitate membrane binding (181) and can be considered to be a PreSMo or MoRF.

Figure 5.

Conformational plasticity of α-synuclein. α-Synuclein is intrinsically disordered in the free state, adopts helical structure upon membrane binding, and can aggregate into β-sheet–rich amyloid fibrils. A, N-terminal ∼100 residues constitute the membrane-binding domain of α-synuclein and can be subdivided into helix 1 (green) and helix 2 (purple) based on its micelle-binding properties. Helix 2 contains the hydrophobic NAC region (cyan) that is believed to drive α-synuclein aggregation. The C-terminal ∼40 residues form an acidic C-terminal domain (red). Phosphorylation sites discussed in the text are indicated. B, membrane-bound α-synuclein can adopt either an extended-helix or a broken-helix conformation with helices 1 and 2 separated by a short linker region; the broken-helix conformation may allow synuclein to bridge discrete membranes and so to function in vesicle docking and/or vesicle clustering. C, α-synuclein can bind to membranes via helix 1 alone. This binding mode may facilitate aggregation of the adjacent hydrophobic NAC region by promoting intermolecular interactions on the membrane surface.

Once membrane binding is initiated at the N-terminal end of α-synuclein, coupled membrane binding and folding propagates the initial helical structure through the remainder of the N-terminal lipid-binding domain. Several different membrane-bound helical conformations have been reported featuring amphipathic helices of varying lengths that lie along the surface of the membrane. In the extended-helix conformation, the entire N-terminal domain (∼100 residues) binds to the membrane surface through a continuous amphipathic α-helix with an unusual 11/3 periodicity (wherein 11 residues form 3 helical turns, a slightly overwound geometry compared with α-helices, where 18 residues form 5 turns) (169, 176, 182–188). An alternative conformation in which the extended helix is broken into two distinct helices separated by a nonhelical linker region from residues ∼39–45 has also been observed on both micelles and vesicles (176, 177, 183, 184, 189–194) and termed the broken helix conformation (126, 189–192). Additional binding modes have been observed on phospholipid vesicles or detergent micelles, with shorter membrane-bound helical segments at the N terminus of the lipid-binding domain and the remainder of the protein unbound and disordered (115, 116, 168, 181, 191, 195, 196).

Putative functional and pathological mechanisms have been proposed for synuclein based on this wealth of structural data. In particular, it has been proposed that the broken helix state may span distinct membranes (Fig. 5B), for example between docked/primed synaptic vesicles and the plasma membrane (115, 116, 126, 133) or alternatively between clustered synaptic vesicles (197). Modulation of the broken to extended helical conformation (by e.g. phosphorylation, or protein/protein interactions) could then alter synuclein's activities in these contexts (198).

The most hydrophobic segment in α-synuclein is the NAC region, spanning residues 61–95 of the N-terminal domain. This region contributes critically to synuclein oligomerization and aggregation, and thus likely to pathology (199). Conformations in which the protein is bound to the membrane solely via regions N-terminal to the NAC domain may contribute to enhanced synuclein aggregation (Fig. 5C). The unbound NAC region will be present at an elevated effective concentration on the two-dimensional membrane surface and so may more readily oligomerize and aggregate (115, 116, 168, 196). Interactions between the membrane-bound helical regions of the protein could further enhance inter-molecular interactions (200).

Unlike its N-terminal lipid-binding domain, the acidic C-terminal domain of α-synuclein, spanning the last ∼40 residues, remains largely unstructured in the presence of lipid membranes (162, 176, 177, 183, 189); although at very high protein-to-lipid ratios, some binding of this region is observed (168, 196), and calcium binding in this region has also been reported (201) and may result in a stronger binding to membranes (202, 203). The C-terminal tail is commonly considered to mediate α-synuclein interactions with other proteins, including, for example, synaptobrevin-2 (the synaptic v-SNARE) (119) and Rab proteins (small GTPases that regulate many steps of cellular trafficking) (204). These interactions are in turn potentially modulated by PTMs in this region.

As is often the case for many IDPs, synuclein can undergo a number of PTMs. Only two will be discussed here: N-terminal acetylation and phosphorylation. The N terminus of α-synuclein is acetylated by the acetyltransferase NatB, and this modification increases transient helicity of the N-terminal ∼10 residues as mentioned above. Acetylation enhances binding to highly-curved vesicles of comparable size and composition to synaptic vesicles, a putative in vivo binding target for synuclein (181).

α-Synuclein can also be phosphorylated at a number of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues, including Tyr-39 and Ser-87 in the N-terminal domain and Tyr-125 and Ser-129 in the C-terminal tail (205–210). The ways in which synuclein phosphorylation alters its structure, dynamics, and function remain incompletely understood. Phosphorylation of Ser-87 reduces binding to lipid membranes and alters the structure of micelle-bound synuclein (211). A recent study showed that c-Abl kinase phosphorylates Tyr-39, a modification that alters the membrane-bound structure of synuclein by freeing the C-terminal half of the N-terminal domain (helix 2) from the membrane (210). This may thereby facilitate interconversion of synuclein from the extended helix to the broken helix state (198). Tyr-39 phosphorylation and its subsequent effects could thus have implications both for synuclein function and for dysfunction and pathology, particularly given the functional models discussed above and given that helix 2 contains the NAC domain that critically contributes to synuclein aggregation.

Ultimately, our understanding of α-synuclein function and interactions suggests that the conformational plasticity inherent in its free state as a disordered polypeptide chain enables multiple discrete membrane-binding modes. Different structural states likely occur in different cellular contexts and can be modulated by PTMs or by interactions with a number of other proteins. It seems clear that the structural plasticity of α-synuclein thus enables it to carry out a potentially diverse set of functions that would not be achievable in the context of a single well-ordered conformation.

Intrinsic disorder and phase transitions in the organization of the synapse

It is becoming increasingly clear that in addition to employing membrane-enclosed cellular organelles, cells can also compartmentalize cellular activities through the formation of membrane-less organelles such as stress granules, P-bodies, and neuronal granules (in the cytoplasm), and nucleoli, Cajal bodies, and PML bodies (in the nucleus), among others (11, 13, 212). These are multicomponent, viscous, liquid-like structures, often containing both protein and RNA molecules (212–215). They occur via spontaneous phase transitions that can be regulated through protein and RNA concentrations, charge states, and solution conditions. These factors can in turn be regulated by changes in gene expression or protein translation (altering biomolecular concentrations), post-translational modification (altering charge states), and changes in ion or salt concentrations (altering solution conditions) (212). IDPs and IDRs are in many cases key players driving intracellular phase transitions, often through their ability to bind to multiple partners (11, 54). Phase transitions appear to require multivalent interactions of modular binding domains, with modest affinity binding and long flexible connections between binding elements (214). In many cases modular binding domains bind to IDRs through multiple, transient, and weak interactions that are able to drive phase separation into liquid droplets or hydrogels (11). With that being said, multivalent interactions of structured domains are also capable of driving such phase transitions (214), although it is likely that disordered linkers between structured interaction modules contribute a degree of flexibility necessary for these assemblies to form. The multivalent interactions that lead to the formation of cytosolic membrane-less organelles can also lead to two-dimensional phase separation of membrane-associated proteins and can organize large-scale protein assemblies at the membrane surface (215, 216).

Synaptic vesicle clusters

In presynaptic nerve terminals, SVs are known to form dense clusters in proximity to active zones. These clusters represent pools of vesicles that are available to replenish vesicles that are docked and primed at the active zone after these vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents into the synaptic cleft in response to action potential triggered calcium entry. This is especially important during periods of high activity when endocytosis is too slow to replenish these vesicles (217). The protein synapsin has long been implicated as a critical player in SV cluster formation and maintenance (218–220), but its mechanisms of action have remained controversial.

Synapsins contain long disordered proline-rich C-terminal domains that are potentially capable of interacting with multiple SH3 domains in various interaction partners (221). A recent report (222) shows that the C-terminal domain of synapsin 1 can mediate phase separation independently or in the context of the full-length protein and that the process is enhanced in the presence of SH3 domain containing interaction partners such as GRB2 and intersectin. Furthermore, the resulting droplets can capture and cluster lipid vesicles via the synapsin membrane-binding domain, and the droplets and clusters are dispersed in response to synapsin phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Phosphorylation of synapsin 1 by CaMKII under intense stimulation is known to drive its release from SV clusters in neurons.

These observations suggest strongly that SV clustering at presynaptic nerve terminals may result from phase separation of synapsin, driven by multivalent interactions between its disordered C-terminal domain and a variety of interaction partners. Furthermore, synapsin phase separation is regulated in response to neuronal activity to release SVs from SV clusters and make them available for replacing fused vesicles (222).

Post-synaptic densities

Across the synapse, post-synaptic densities (PSDs) are found closely abutted to presynaptic active zones such that efficient pre- to post-synaptic signaling can occur across the synapse. Disc-shaped, electron-dense PSDs consist of an organized assembly of multiple proteins that together function to receive, interpret, and store presynaptic signals (223). They contain ∼30–50-nm–wide mega-assemblies of densely packed proteins, although they are known to be highly dynamic, with constant exchange of PSD components with bulk cytoplasm. This latter feature is particularly important for synaptic changes underlying long-term potentiation and depression. As might be expected for a cellular compartment containing numerous proteins capable of multivalent binding, an emerging hypothesis suggests that PSDs form a membrane-less, phase-separated, and liquid-like organelle.

SynGAP and PSD-95 are two of the more abundant PSD proteins, where they exist at a near-stoichiometric ratio. PSD-95 contains three PDZ domains, an SH3 domain, and a guanylate kinase domain, whereas SynGAP contains a pleckstrin homology domain, C2 domain, GAP domain, and coiled-coil domain and is capable of forming a parallel coiled-coil trimer (223). These structured domains are linked by disordered regions of various lengths. It was recently shown that the SynGAP coiled-coil trimer binds to multiple copies of PSD-95 through an extended helix within the third PSD-95 PDZ domain to form a 3:2 multivalent complex; notably, this interaction induced phase separation of this complex and led to the formation of liquid-like droplets in vitro and in cells, which were proposed to play a key role in the organization of the post-synaptic density (223).

Supramolecular assemblies rely critically on scaffold proteins, which typically contain a high level of disorder in addition to multiple ordered domains (224), and the role of intrinsic disorder in scaffold proteins has been reviewed (7). CASK-interactive protein 1 (Caskin1) was identified as another post-synaptic density scaffolding protein. This protein contains six ankyrin repeats, two sterile α-motifs, and one SH3 domain in the N-terminal region; the C-terminal region consists primarily of a long proline-rich region, with no other clear domains. This proline-rich region was shown to be intrinsically disordered and to mediate an interaction with Abl–interactor-2, a CASK adaptor protein. Caskin1 interacts with at least 10 other partners and so could be a key scaffold protein at the post-synaptic density (224), possibly also via multivalent interactions leading to phase separation.

Presynaptic active zones

The presynaptic active zone also contains a number of proteins with multiple protein interaction modules. Many of the relevant protein/protein interactions have been mapped out (5), and it is clear that key presynaptic active-zone proteins–RIM, RIM-BP, Munc13, Liprin, and ELKS, for example, are rich in binding modules such SH3, C2, PDZ, zinc finger (ZF), sterile α-motif (SAM), and others. Many presynaptic active-zone proteins, such as RIM, Piccolo, and Basoon, also contain long-disordered regions (225–227) that contain binding module recognition sites. For example, SH3 domains in RIM-BP interact with proline-rich motifs in RIM (5), which are likely disordered, as in Caskin1, although some polyproline-2 structures may also be present (7). It is possible, then, that the presynaptic active zone may organize and function through a type of phase transition into a liquid-like dynamic state. No work to our knowledge has yet directly addressed this possibility.

Summary

IDPs play key roles in nearly all aspects of biology. Here, we have reviewed the role of protein disorder in the regulation of synaptic vesicle trafficking and release, processes fundamental to the proper function of all nervous systems. Many of the key proteins involved in these critical processes contain significant disorder, or in some cases are fully disordered. Functionally significant properties of IDPs that play roles in other cellular processes–multiple conformations, multiple interactions, etc.–are also important in synaptic vesicle homeostasis. Additional roles for IDPs that are not as widely appreciated are also noted here. SNARE proteins and their assembly into SNARE bundles provide an interesting example of force generation upon IDP/IDR folding. α-Synuclein and complexin exemplify IDP/membrane interactions; both of these proteins interact with membranes in a curvature-sensitive manner, and at least one of them can also influence membrane topology, possibly in a functionally relevant way. Finally, we note a few cases where the recently discovered ability of IDPs and IDRs to organize cellular compartments via three- or two-dimensional phase separation appears to extend to structures that have long been recognized as defining features of nerve terminals, but for which the underlying principles of formation and maintenance have long remained inscrutable.

We hope that this review will serve to inform the reader about the prevalence and importance of IDPs in aspects of neuronal function, and to introduce them to some of the unique features and properties of this class of proteins. Going forward, we hope that as neuroscientists, in particular, encounter IDPs and IDRs during their work, rather than overlooking them because they are unstructured and therefore unimportant, they will instead consider and investigate their potential roles in the physiological functions and interactions that are the subject of their research. The diverse nature of IDPs and of the mechanisms they employ to achieve their biological activity present a challenge, especially to the classical notion of protein structure/function relationships. Going forward, meeting this challenge in the context of neuroscience will require an ever-deeper integration of structural and biophysical investigations with cellular and organism-level studies of neuronal function.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R37AG019391 (to D. E.), R01GM117518 (to D. E.), F30MH101982 (to D. S.), and MSTPGM07739 (to D. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- IDP

- intrinsically disordered protein

- IDR

- intrinsically disordered protein region

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- ALPS

- amphipathic lipid-packing sensor

- NSF

- N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor

- SNAP

- soluble NSF attachment protein

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- AH

- accessory helix

- CH

- central helix

- SH

- Src homology

- RIM-BP

- RIM-binding protein

- Syt1

- synaptotagmin-1

- MARCKS

- membrane-binding region of the myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate

- CaMKII

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- PSD

- post-synaptic density

- SV

- synaptic vesicle

- NAC

- non-amyloid-beta-component.

References

- 1. Rizo J., and Rosenmund C. (2008) Synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 665–674 10.1038/nsmb.1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rizo J., and Südhof T. C. (2012) The membrane fusion enigma: SNAREs, Sec1/Munc18 proteins, and their accomplices–guilty as charged? Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 28, 279–308 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rizo J., and Xu J. (2015) The synaptic vesicle release machinery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 44, 339–367 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Südhof T. C., and Rizo J. (2011) Synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Südhof T. C. (2012) The presynaptic active zone. Neuron 75, 11–25 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burger V. M., Nolasco D. O., and Stultz C. M. (2016) Expanding the range of protein function at the far end of the order-structure continuum. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6706–6713 10.1074/jbc.R115.692590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cortese M. S., Uversky V. N., and Dunker A. K. (2008) Intrinsic disorder in scaffold proteins: getting more from less. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 98, 85–106 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uversky V. N. (2016) Dancing protein clouds: the strange biology and chaotic physics of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6681–6688 10.1074/jbc.R115.685859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shammas S. L., Crabtree M. D., Dahal L., Wicky B. I., and Clarke J. (2016) Insights into coupled folding and binding mechanisms from kinetic studies. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6689–6695 10.1074/jbc.R115.692715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Papoian G. A. (2008) Proteins with weakly funneled energy landscapes challenge the classical structure-function paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14237–14238 10.1073/pnas.0807977105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bah A., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2016) Modulation of intrinsically disordered protein function by post-translational modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6696–6705 10.1074/jbc.R115.695056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arai M., Sugase K., Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2015) Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins influence the mechanism of binding and folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 9614–9619 10.1073/pnas.1512799112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Banerjee R. (2016) Introduction to the thematic minireview series on intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6679–6680 10.1074/jbc.R116.719930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guharoy M., Bhowmick P., and Tompa P. (2016) Design principles involving protein disorder facilitate specific substrate selection and degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6723–6731 10.1074/jbc.R115.692665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pietrosemoli N., Pancsa R., and Tompa P. (2013) Structural disorder provides increased adaptability for vesicle trafficking pathways. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003144 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montesinos M. L., Castellano-Muñoz M., García-Junco-Clemente P., and Fernández-Chacón R. (2005) Recycling and EH domain proteins at the synapse. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 416–428 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Drouet V., and Lesage S. (2014) Synaptojanin 1 mutation in Parkinson's disease brings further insight into the neuropathological mechanisms. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 289728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambroggio E., Sorre B., Bassereau P., Goud B., Manneville J. B., and Antonny B. (2010) ArfGAP1 generates an Arf1 gradient on continuous lipid membranes displaying flat and curved regions. EMBO J. 29, 292–303 10.1038/emboj.2009.341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antonny B. (2011) Mechanisms of membrane curvature sensing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 101–123 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052809-155121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bigay J., Gounon P., Robineau S., and Antonny B. (2003) Lipid packing sensed by ArfGAP1 couples COPI coat disassembly to membrane bilayer curvature. Nature 426, 563–566 10.1038/nature02108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bigay J., Casella J. F., Drin G., Mesmin B., and Antonny B. (2005) ArfGAP1 responds to membrane curvature through the folding of a lipid packing sensor motif. EMBO J. 24, 2244–2253 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drin G., and Antonny B. (2010) Amphipathic helices and membrane curvature. FEBS Lett. 584, 1840–1847 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mesmin B., Drin G., Levi S., Rawet M., Cassel D., Bigay J., and Antonny B. (2007) Two lipid-packing sensor motifs contribute to the sensitivity of ArfGAP1 to membrane curvature. Biochemistry 46, 1779–1790 10.1021/bi062288w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rothman J. E., and Wieland F. T. (1996) Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science 272, 227–234 10.1126/science.272.5259.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drin G., Casella J. F., Gautier R., Boehmer T., Schwartz T. U., and Antonny B. (2007) A general amphipathic α-helical motif for sensing membrane curvature. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 138–146 10.1038/nsmb1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vanni S., Vamparys L., Gautier R., Drin G., Etchebest C., Fuchs P. F., and Antonny B. (2013) Amphipathic lipid packing sensor motifs: probing bilayer defects with hydrophobic residues. Biophys. J. 104, 575–584 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sen A., Madhivanan K., Mukherjee D., and Aguilar R. C. (2012) The epsin protein family: coordinators of endocytosis and signaling. Biomol. Concepts 3, 117–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Capraro B. R., Yoon Y., Cho W., and Baumgart T. (2010) Curvature sensing by the epsin N-terminal homology domain measured on cylindrical lipid membrane tethers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1200–1201 10.1021/ja907936c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shoemaker B. A., Portman J. J., and Wolynes P. G. (2000) Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: the fly-casting mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8868–8873 10.1073/pnas.160259697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jahn R., and Scheller R. H. (2006) SNAREs–engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 631–643 10.1038/nrm2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Südhof T. C., and Rizo J. (2011) Synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, 1–14 10.1101/cshperspect.a005637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fasshauer D., Otto H., Eliason W. K., Jahn R., and Brünger A. T. (1997) Structural changes are associated with soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28036–28041 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fasshauer D., Bruns D., Shen B., Jahn R., and Brünger A. T. (1997) A structural change occurs upon binding of syntaxin to SNAP-25. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 4582–4590 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fasshauer D. (2003) Structural insights into the SNARE mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1641, 87–97 10.1016/S0167-4889(03)00090-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hazzard J., Südhof T. C., and Rizo J. (1999) NMR analysis of the structure of synaptobrevin and of its interaction with syntaxin. J. Biomol. NMR 14, 203–207 10.1023/A:1008382027065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Margittai M., Fasshauer D., Pabst S., Jahn R., and Langen R. (2001) Homo- and heterooligomeric SNARE complexes studied by site-directed spin labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13169–13177 10.1074/jbc.M010653200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sakon J. J., and Weninger K. R. (2010) Detecting the conformation of individual proteins in live cells. Nat. Methods 7, 203–205 10.1038/nmeth.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ungar D., and Hughson F. M. (2003) SNARE protein structure and function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 493–517 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.155609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jahn R., and Fasshauer D. (2012) Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature 490, 201–207 10.1038/nature11320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Südhof T. C. (2013) Neurotransmitter release: the last millisecond in the life of a synaptic vesicle. Neuron 80, 675–690 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma C., Su L., Seven A. B., Xu Y., and Rizo J. (2013) Reconstitution of the vital functions of Munc18 and Munc13 in neurotransmitter release. Science 339, 421–425 10.1126/science.1230473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brose N. (2008) For better or for worse: complexins regulate SNARE function and vesicle fusion. Traffic 9, 1403–1413 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hatsuzawa K., Lang T., Fasshauer D., Bruns D., and Jahn R. (2003) The R-SNARE motif of tomosyn forms SNARE core complexes with syntaxin 1 and SNAP-25 and down-regulates exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31159–31166 10.1074/jbc.M305500200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bielopolski N., Lam A. D., Bar-On D., Sauer M., Stuenkel E. L., and Ashery U. (2014) Differential interaction of tomosyn with syntaxin and SNAP25 depends on domains in the WD40 β-propeller core and determines its inhibitory activity. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 17087–17099 10.1074/jbc.M113.515296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martin J. A., Hu Z., Fenz K. M., Fernandez J., and Dittman J. S. (2011) Complexin has opposite effects on two modes of synaptic vesicle fusion. Curr. Biol. 21, 97–105 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fujita Y., Shirataki H., Sakisaka T., Asakura T., Ohya T., Kotani H., Yokoyama S., Nishioka H., Matsuura Y., Mizoguchi A., Scheller R. H., and Takai Y. (1998) Tomosyn: a syntaxin-1-binding protein that forms a novel complex in the neurotransmitter release process. Neuron 20, 905–915 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80472-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brewer K. D., Bacaj T., Cavalli A., Camilloni C., Swarbrick J. D., Liu J., Zhou A., Zhou P., Barlow N., Xu J., Seven A. B., Prinslow E. A., Voleti R., Häussinger D., Bonvin A. M., et al. (2015) Dynamic binding mode of a synaptotagmin-1–SNARE complex in solution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 555–564 10.1038/nsmb.3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou Q., Lai Y., Bacaj T., Zhao M., Lyubimov A. Y., Uervirojnangkoorn M., Zeldin O. B., Brewster A. S., Sauter N. K., Cohen A. E., Soltis S. M., Alonso-Mori R., Chollet M., Lemke H. T., Pfuetzner R. A., et al. (2015) Architecture of the synaptotagmin-SNARE machinery for neuronal exocytosis. Nature 525, 62–67 10.1038/nature14975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou Q., Zhou P., Wang A. L., Wu D., Zhao M., Südhof T. C., and Brunger A. T. (2017) The primed SNARE–complexin–synaptotagmin complex for neuronal exocytosis. Nature 548, 420–425 10.1038/nature23484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lai Y., Lou X., Jho Y., Yoon T. Y., and Shin Y. K. (2013) The synaptotagmin 1 linker may function as an electrostatic zipper that opens for docking but closes for fusion pore opening. Biochem. J. 456, 25–33 10.1042/BJ20130949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fealey M. E., Mahling R., Rice A. M., Dunleavy K., Kobany S. E., Lohese K. J., Horn B., and Hinderliter A. (2016) Synaptotagmin I's intrinsically disordered region interacts with synaptic vesicle lipids and exerts allosteric control over C2A. Biochemistry 55, 2914–2926 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gauer J. W., Sisk R., Murphy J. R., Jacobson H., Sutton R. B., Gillispie G. D., and Hinderliter A. (2012) Mechanism for calcium ion sensing by the C2A domain of synaptotagmin I. Biophys. J. 103, 238–246 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Han G. A., Bin N. R., Kang S. Y., Han L., and Sugita S. (2013) Domain 3a of Munc18-1 plays a crucial role at the priming stage of exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 126, 2361–2371 10.1242/jcs.126862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baker R. W., Jeffrey P. D., Zick M., Phillips B. P., Wickner W. T., and Hughson F. M. (2015) A direct role for the Sec1/Munc18-family protein Vps33 as a template for SNARE assembly. Science 349, 1111–1114 10.1126/science.aac7906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Parisotto D., Pfau M., Scheutzow A., Wild K., Mayer M. P., Malsam J., Sinning I., and Sollner T. H. (2014) An extended helical conformation in domain 3a of Munc18-1 provides a template for SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9639–9650 10.1074/jbc.M113.514273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Martin S., Tomatis V. M., Papadopulos A., Christie M. P., Malintan N. T., Gormal R. S., Sugita S., Martin J. L., Collins B. M., and Meunier F. A. (2013) The Munc18-1 domain 3a loop is essential for neuroexocytosis but not for syntaxin-1A transport to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 126, 2353–2360 10.1242/jcs.126813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Colbert K. N., Hattendorf D. A., Weiss T. M., Burkhardt P., Fasshauer D., and Weis W. I. (2013) Syntaxin1a variants lacking an N-peptide or bearing the LE mutation bind to Munc18a in a closed conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12637–12642 10.1073/pnas.1303753110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hu S. H., Christie M. P., Saez N. J., Latham C. F., Jarrott R., Lua L. H., Collins B. M., and Martin J. L. (2011) Possible roles for Munc18-1 domain 3a and syntaxin1 N-peptide and C-terminal anchor in SNARE complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1040–1045 10.1073/pnas.0914906108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wentzel C., Sommer J. E., Nair R., Stiefvater A., Sibarita J. B., and Scheiffele P. (2013) mSYD1A, a mammalian synapse-defective-1 protein, regulates synaptogenic signaling and vesicle docking. Neuron 78, 1012–1023 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Seelig J. (2004) Thermodynamics of lipid-peptide interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666, 40–50 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. White S. H., and Wimley W. C. (1998) Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1376, 339–352 10.1016/S0304-4157(98)00021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. White S. H., and Wimley W. C. (1999) Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 28, 319–365 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morton L. A., Tamura R., de Jesus A. J., Espinoza A., and Yin H. (2014) Biophysical investigations with MARCKS-ED: dissecting the molecular mechanism of its curvature sensing behaviors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 3137–3144 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wragg R. T., Snead D., Dong Y., Ramlall T. F., Menon I., Bai J., Eliezer D., and Dittman J. S. (2013) Synaptic vesicles position complexin to block spontaneous fusion. Neuron 77, 323–334 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McMahon H. T., and Gallop J. L. (2005) Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature 438, 590–596 10.1038/nature04396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]