Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The mortality rate of bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis is highest during the period of acute bleeding. This is a report of a randomized trial that compared endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) with emergency portacaval shunt (EPCS) in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage.

STUDY DESIGN:

A total of 211 unselected consecutive patients with cirrhosis and acutely bleeding esophageal varices who required at least 2 U of blood transfusion were randomized to EST (n = 106) or EPCS (n = 105). Diagnostic workup was completed within 6 hours and EST or EPCS was initiated within 8 hours of initial contact. Longterm EST was performed according to a deliberate schedule. Ninety-six percent of patients underwent more than 10 years of followup, or until death.

RESULTS:

The percent of patients in Child’s risk classes were A, 27.5; B, 45.0; and C, 27.5. EST achieved permanent control of bleeding in only 20% of patients; EPCS permanently controlled bleeding in every patient (p ≤0.001). Requirement for blood transfusions was greater in the EST group than in the EPCS patients. Compared with EST, survival after EPCS was significantly higher at all time intervals and in all Child’s classes (p ≤0.001). Recurrent episodes of portal-systemic encephalopathy developed in 35% of EST patients and 15% of EPCS patients (p ≤0.01).

CONCLUSIONS:

EPCS permanently stopped variceal bleeding, rarely became occluded, was accomplished with a low incidence of portal-systemic encephalopathy, and compared with EST, produced greater longterm survival. The widespread practice of using surgical procedures mainly as salvage for failure of endoscopic therapy is not supported by the results of this trial (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00690027).

Bleeding esophageal varices (BEV) is a common and highly lethal complication of cirrhosis of the liver. The mortality rate associated with BEV is highest during the period surrounding the episode of acute bleeding.1–9 If the varices remain untreated after recovery from a bout of acute bleeding, we6 and others7 observed a 95% incidence of recurrent bleeding, and death within 2 to 5 years in 90% to 100% of the patients. Recurrent bleeding has been reported to develop most often within the first few days after the acute bleeding episode.1,2 So it is clear that emergency treatment of acute bleeding is of paramount importance in the care of patients with portal hypertension and esophagogastric varices.

Several types of emergency therapy are currently used to control acute BEV, but the superiority of one or another of these measures has not been established. The most widely used emergency treatments throughout the world are endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy and endoscopic variceal ligation. Other emergency measures include esophageal balloon tamponade, pharmacologic therapy with various agents, transjugular intrahepatic portal-systemic shunt (TIPS), esophageal devascularization and transection, and emergency portal-systemic shunt. Numerous randomized controlled trials comparing these various modalities have been performed in the elective setting to determine their effectiveness in preventing rebleeding in patients who have recovered from one or more episodes of acute bleeding, and in patients who have never bled to determine their effectiveness in primary prophylaxis against bleeding.5 But with one exception that restricted inclusion in the study to highly selected patients with advanced cirrhosis classified as Child’s class C,10,11 no randomized trials comparing surgical therapy and endoscopic therapy in the very important matter of treatment of acute bleeding have been reported.5

Because of the over-riding importance of emergency treatment of variceal bleeding, from 1958 to 2006 we conducted and reported studies of emergency therapy in patients with cirrhosis.12–16 Our studies, including this trial, have been distinguished by three features that, together, make them different from other reported investigations. All patients admitted to our institution with cirrhosis and BEV, regardless of their condition, were included without selection; the specific emergency treatment undergoing evaluation was administered within 8 hours of initial contact; and our studies were prospective, meaning that a well-defined protocol was consistently used and data were collected on-line.

This is a report of the results of a randomized controlled trial in 211 patients with cirrhosis and acute BEV in whom emergency and longterm endoscopic sclerotherapy were compared with emergency direct portacaval shunt. The study was conducted from April 8, 1988, to December 31, 2005. The trial was a community-wide endeavor and was known as the San Diego Bleeding Esophageal Varices Study. This report focuses on control of bleeding and survival.

METHODS

Design of study

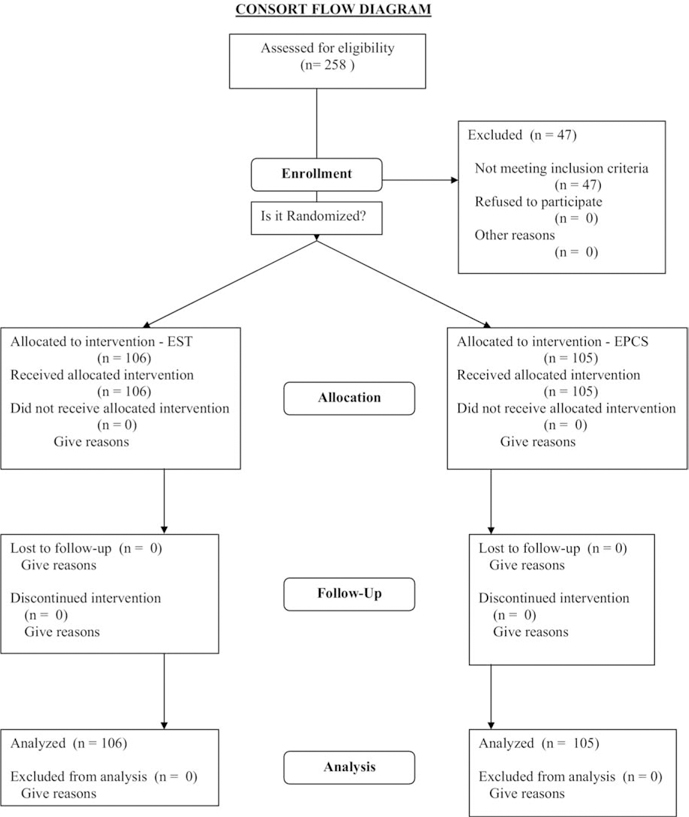

The objectives were to compare, in unselected consecutive patients who entered the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) Medical Center with cirrhosis and acute BEV, the influence on survival rate, control of bleeding, quality of life, and economic costs of endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) and emergency direct portacaval shunt (EPCS). Eighty-three physicians in San Diego, Imperial, Orange, and Riverside counties agreed to promptly refer patients with BEV to UCSD Medical Center for entry into the study. The 83 referring physicians included 51 board-certified gastroenterologists, 18 emergency physicians, and 14 board-certified surgeons. Patients were entered from April 8, 1988, until August 15, 1996. Followup was continued until December 31, 2005, 17 and 3/4 years after the start of the study. The study protocol and consent forms were approved before the start of the study and at regular intervals thereafter by the UCSD Human Subjects’ Committee (Institutional Review Board). Figure 1 is a consort flow diagram that shows the overall design and conduct of the prospective randomized controlled trial.17,18

Figure 1.

The overall design and conduct of the prospective randomized controlled trial is shown in a consort flow diagram.17,18 EPCS, emergency portacaval shunt; EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy.

Eligibility

All patients, without selection, who met the criteria for the diagnosis of acute BEV resulting from cirrhosis and whose bleeding required transfusion of ≥2 U of blood were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients whose history included more than one session of EST were not eligible for the study. For patients transferred from area hospitals, a requirement was observation of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding within 48 hours of transfer. A total of 47 patients with UGI bleeding who were referred for inclusion in the study failed to meet the eligibility criteria because they did not have BEV and did not have cirrhosis of the liver. Followup of these patients confirmed the validity of the initial decision to deny them involvement in the study. During the course of the study, patients with cirrhosis and BEV made up a relatively small fraction of the total patients with UGI bleeding cared for at UCSD Medical Center; the majority of these were bleeding from other causes.

Definitions

Bleeding esophageal varices

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding was defined as blood in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum, in a patient who had hematemesis or melena or both, and was shown by endoscopy to have esophageal varices observed to be actively bleeding, or had an adherent blood clot, or had red color signs on varices, and had no other associated lesion that could reasonably account for bleeding of the observed magnitude.

Unselected patients (“all comers”)

Unselected patients were considered all patients with BEV and cirrhosis, without exception, who entered the emergency room at UCSD Medical Center or were transferred from area hospitals directly to a special ICU at UCSD Medical Center, or in whom bleeding developed while in UCSD Medical Center.

Emergency endoscopic sclerotherapy

Emergency EST was defined as being performed within 8 hours of the patient’s initial contact with the UCSD staff because of UGI bleeding. Initial contact meant entry in the UCSD Medical Center emergency room because of bleeding, transfer directly to a special ICU at UCSD Medical Center from an area hospital because of bleeding, or development of bleeding during the course of hospitalization in UCSD Medical Center for a reason other than bleeding.

Longterm endoscopic sclerotherapy

Longterm EST was performed according to a deliberate schedule over a period of months for the purpose of obliterating esophageal varices in survivors of emergency EST.

Emergency portacaval shunt

EPCS was defined as direct portacaval shunt, side-to-side or end-to-side, performed within 8 hours of the patient’s initial contact (defined earlier) with the UCSD staff, because of UGI bleeding.

Failure of emergency primary therapy

Failure of emergency primary therapy occurred when, after replacement of blood loss before and during primary treatment, continued or recurrent bleeding after EST or EPCS required transfusion of ≥6 U of packed red blood cells (PRBC) during the first 7 days after entry into the study, with active bleeding occurring during or after administration of the sixth unit.

Failure of longterm therapy

Failure of longterm therapy occurred when, after 7 days in the study, recurrent UGI bleeding shown by endoscopy to be coming from esophagogastric varices, required treatment with a total of ≥8 U of blood transfusion during any 12-month period or, additionally, required blood transfusions after the attending faculty endoscopist had declared the esophageal varices obliterated or gone.

Rescue therapy

Rescue therapy was crossover treatment applied, whenever possible, to patients in either group in whom failure of primary therapy was declared, ie, rescue portacaval shunt (PCS) for EST failure, and rescue EST for PCS failure.

Informed consent

Informed consent was defined as consent to participate in the study, obtained by a physician coinvestigator, from every patient before randomization to the treatment groups, and witnessed by a third party who was not involved in the study. Consent was obtained after the patient was given a thorough explanation of the study, including the risks and benefits of all treatment options. When it was not possible to obtain informed consent because of an altered sensorium, two patient advocates were assigned to the patient by a panel of faculty physicians who were not involved in the study to determine if consent should be given. The procedure for obtaining consent and the consent form were regularly reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Committee (Institutional Review Board).

Randomization

After emergency endoscopy demonstrated esophageal varices and no other lesion that could reasonably account for the bleeding, the diagnostic workup provided clear evidence of cirrhosis of the liver, and informed consent was obtained, the patients were randomized by drawing a card from an opaque sealed envelope, to either an EST group or an EPCS group. Sealed designation cards were prepared by a statistician according to a computer-generated block randomization design, without the knowledge of the physicians participating in the study. Patients in Child’s risk class C were randomized separately from those in classes A and B to assure an equal distribution of class C patients in the two treatment groups. One hundred six patients were randomized to EST and 105 patients were randomized to EPCS. Before randomization all patients had received ≥2 U of PRBC.

Diagnostic workup

All patients underwent the same diagnostic workup that was completed within 6 hours of initial contact and included history and physical examination; blood studies described in detail previously16; urinalysis; Doppler duplex ultrasonography; portable chest x-ray; electrocardiogram; and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The entire workup was performed at the patient’s bedside in the ICU. When the initial diagnostic workup was completed, before randomization, the patients were classified into Child’s risk classes. Randomization was not performed until the diagnostic workup was completed.

Initial emergency therapy during workup

All patients received the same initial therapy while the diagnostic workup was in progress. They were housed in the ICU where the nursing staff was expert in the care of patients with cirrhosis and acute UGI bleeding and was thoroughly familiar with the study protocol. During endoscopy, vasopressin was given by continuous IV infusion, starting with 0.2 U/min and increasing to 0.6 U/min if bleeding continued. Thirty-six patients (17%) with a proved or suggestive history of coronary artery disease were not given vasopressin. Octreotide was not used in this study but became standard practice in our institution after patient entry ended in 1996. Transfusions of blood and fresh frozen plasma were given through large-bore IV catheters. Arterial blood pressure, arterial blood gases and pH, central venous pressure, and half-hourly urine output were monitored continuously. The stomach was lavaged with iced saline solution through a large-bore nasogastric tube, and after endoscopy, a solution containing 4g neomycin sulfate and 60 mL magnesium sulfate was instilled in the stomach. After endoscopy, an enema containing 4g neomycin in 250 mL water was administered. Patients in both groups received broad-spectrum antibiotics before and for 3 days after EST or EPCS.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy

Patients randomized to EST received treatment at the bedside within 8 hours of initial contact with the UCSD staff. Some patients required two endoscopic procedures, the first for diagnosis and the second, after randomization, for initial sclerotherapy. Survivors underwent longterm EST. Both emergency and longterm EST were performed by board-certified attending faculty gastroenterologists with long experience in endoscopic therapy. EST consisted of intravariceal injection of 1.5% sodium tetradecyl sulfate. Less than 1 mL of sclerosant was used per injection. At the initial session, the pattern of injections was standardized so that each distal esophageal varix was injected at the gastroesophageal junction and about 2.5 cm and 5 cm above the gastroesophageal junction. The schedule of EST sessions after initial EST was: no. 2 in 8 days ± 24 hours; no. 3 in 22 days; no. 4 in 6 weeks; and thereafter, every 3 weeks until esophageal varices were obliterated. If the patient experienced recurrent BEV between scheduled EST sessions, endoscopy and emergency EST were done promptly.

After EST the patients were housed in the same ICU to which all patients were admitted initially, and they received supportive therapy and study similar to that received postoperatively in the EPCS group. A percutaneous needle liver biopsy was performed in all patients and the diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed in each case. The patients were discharged on the same diet as the EPCS patients, with an appointment for followup in a special portal hypertension clinic in 2 weeks.

UGI endoscopy was performed every 3 months after obliteration of varices during the first year after entry into the study, and every 6 months thereafter. At each of these sessions, EST was done if esophageal varices recurred.

Patients in whom emergency or longterm EST was not successful, as defined previously, underwent crossover therapy in the form of a rescue PCS whenever possible. Some patients experienced bleeding and died at hospitals other than UCSD Medical Center where rescue PCS was not available, and some patients died at home from recurrent bleeding. Six patients were unwilling to undergo a rescue operation.

Emergency portacaval shunt

Patients randomized to EPCS underwent a direct portacaval shunt. Operation was done within 8 hours of initial contact with the UCSD staff in 102 of the 105 patients in this group, and within 24 hours in the other 3 patients. Our technique of direct PCS has been described in detail repeatedly, most recently in 2007.19 Direct side-to-side EPCS was performed in 99 patients and direct end-to-side EPCS was done in 6 patients. Intraoperative pressure measurements were made before and after EPCS by direct needle puncture of the portal vein and inferior vena cava, using a saline solution manometer positioned at the level of the inferior vena cava. A large wedge liver biopsy was obtained from all patients and confirmed the diagnosis of cirrhosis in each patient.

The study protocol required that patients who had EPCS that failed, as defined previously, undergo crossover therapy in the form of rescue EST. No patients in the EPCS group had treatment failure.

Posttreatment therapy

After primary therapy, all patients were housed in the same ICU to which they had been admitted initially. Monitoring was continued and included serial measurements of cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, and renal function; fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance; blood count; and blood coagulation. Daily enteral neomycin therapy, cathartics, enemas, and systemic broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered for 3 days. Prophylactic therapy with an H2-receptor antagonist was used to counteract and suppress gastric acid secretion and prevent stress ulceration. Oral nutrition progressed until a diet that contained 3,000 calories, 2 g sodium, and 80 g protein per day was tolerated. Dietary protein tolerance was carefully evaluated for production of portal-systemic encephalopathy (PSE). Patients and their families were given detailed dietary instructions by a dietitian and received repeated counseling about abstinence from alcohol. The patients were discharged from the hospital with a diet limited to 60 g protein and 2 g sodium salt per day.

Lifelong followup

All patients were followed up in a designated portal hypertension clinic biweekly for the first 4 weeks, monthly for the remaining 11 months of the first year, and every 3 months thereafter for life. At each clinic visit, clinical status was evaluated and measurements were made of blood count, liver function, renal function, psychomotor function, and fluid and electrolyte balance. An attending faculty physician evaluated the patient at each clinic visit. A dietitian counseled the patients and their families at each clinic visit on restricting dietary protein intake to 60 g/d, and sodium salt intake to 2 g/d. Abstinence from alcohol was emphasized at each visit. Biochemical serum markers for hepatocellular carcinoma were measured at regular intervals. EPCS patients underwent Doppler duplex ultrasonography yearly to determine PCS patency and function. Whenever UGI bleeding developed, esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed to document the source. In the EST group, upper endoscopy was performed routinely every 6 months. A major effort was made to assure regular followup and to trace patients who missed appointments. If a patient missed two consecutive followup visits, a research nurse coordinator usually visited the patient at home to urge subsequent clinic visits. The few patients who moved from the referral area were put in contact with a physician who agreed to see the patient regularly and return completed study data forms to us. There were no dropouts or withdrawals from the study. Followup was 100%. There were 203 of the 211 patients (96%) who underwent followup for 10 or more years, or until death, and the remaining 8 patients underwent 9.4 to 9.9 years of followup or until death.

Quantitation of portal-systemic encephalopathy

PSE was quantitated during hospitalizations and at each clinic visit by grading four variously weighted components on a scale of 0 to 4: mental state, asterixis, number connection test, and arterial blood ammonia. A PSE index was calculated according to the method of Conn and Liberthal,20 in which the scores of the four components were added to yield a PSE sum, which was then divided by the maximum possible PSE sum. Mental state was given a weight of 3 and the other components a weight of 1. To increase objectivity, a senior faculty gastroenterologist who was not otherwise involved in the BEV study evaluated the patients for PSE during the clinic visits. The gastroenterologist was “blinded” in that he was not told what therapy the patient had received.

Data collection

Fifteen data forms pertinent to the events in the course of each patient were completed by attending physicians, residents, nurses, and social workers at the time that each event occurred. Beginning with initial contact and continuing through followup, detailed data obtained from the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopic findings, x-ray studies, and operative findings were recorded and analyzed. In addition to the hospital medical record, an individual patient research study file was maintained and brought to the portal hypertension clinic at each visit. In most cases, autopsies were obtained on patients who died in the study hospital and were attended by one or more coinvestigators in the study.

Statistical analysis

Variables were summarized by medians and ranges. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups used the Wilcoxon rank test for continuous data, or Fisher’s exact test for count data. Survival distributions for the groups of interest were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared using the log-rank test. Comparison of the survival experience of the direct admission versus outside hospital referral groups used the likelihood ratio test of the Cox proportional hazards model, controlling for treatment arm. No interaction effect was found. At the beginning of the study, it was decided in advance not to perform an interim statistical analysis, so as not to diminish the power of the final analysis.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics at the time of entry in the San Diego BEV Study. The two groups were similar in every important characteristic of cirrhosis and BEV. There was clear evidence of acute UGI bleeding in every patient at the time of entry into the study, usually in the form of hematemesis with hematochezia. In 3% to 8% of the patients, hematochezia was the presenting symptom of bleeding. On physical examination, 36% to 42% of the patients had jaundice, 51% to 61% had ascites that were confirmed by ultrasonography, and 19% to 21% had PSE. Child’s risk class was determined by assessing the five criteria, as in our previous studies,12–16 originally proposed by Child and Turcotte,21 and assigning points to each of the criteria according to the quantitative method of Campbell and colleagues.22 Twenty-five percent to 30% of the patients were in Child’s risk class A, 43% to 47% were in class B, and 26% to 29% were in class C. The overall scores in the two groups of patients were essentially identical.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics at Time of Study Entry of Patients with Cirrhosis and Bleeding Esophageal Varices Randomized to Endoscopic Sclerotherapy or Emergency Portacaval Shunt

| Characteristic | EST (n = 106) |

EPCS (n = 105) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCSD admission, n (%) | 0.24 | ||

| Direct to UCSD emergency room | 35 (33) | 26 (25) | |

| Transfer from outside hospital | 71 (67) | 79 (75) | |

| History | |||

| Age, y | |||

| Mean/median | 47.8/45 | 49.8/47 | 0.21 |

| Range | 23–75 | 28–82 | 0.61 |

| n ≥70 y | 7 | 9 | 0.61 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 81 (76) | 81 (78) | 0.87 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Caucasian | 53 (50) | 58 (55) | |

| Hispanic | 50 (47) | 39 (37) | |

| Other | 3 (3) | 8 (8) | |

| Cause of cirrhosis, n (%) | 0.73 | ||

| Alcoholism alone | 58 (55) | 54(51) | |

| Hepatitis B or C alone | 10 (9) | 8 (8) | |

| Alcoholism and hepatitis | 30 (28) | 33 (31) | |

| Other | 8 (8) | 10 (9) | |

| Bleeding episode, n (%) | 0.76 | ||

| First | 36 (34) | 41 (39) | |

| Second | 38 (36) | 32 (30) | |

| Third or more | 32 (31) | 32 (31) | |

| Chronic alcoholism, n (%) | 88 (83) | 87 (83) | 1.00 |

| Years of alcoholism, mean (range) | 22 (4–59) | 25 (7–54) | 0.56 |

| Recent alcohol ingestion ≤7d, n (%) | 55 (62) | 57 (66) | 0.99 |

| Hematemesis, n (%) | 103 (97) | 97 (92) | 0.13 |

| Hematochezia, n (%) | 88 (83) | 93 (89) | 0.32 |

| Past history, n (%) | |||

| Jaundice | 61 (58) | 58 (55) | 0.78 |

| Ascites | 70 (66) | 48 (46) | 0.004* |

| Portal-systemic encephalopathy | 20 (19) | 30 (29) | 0.11 |

| Delerium tremens in alcoholics | 23 (26) | 28 (31) | 0.43 |

| Other medical disorders | |||

| Narcotic addiction | 31 (29) | 26 (25) | 0.44 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 13 (12) | 24 (23) | 0.047* |

| Hypertension | 13 (12) | 16 (15) | 0.56 |

| Pulmonary disease | 12 (11) | 12 (11) | 1.0 |

| Coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation | 9 (8) | 8 (8) | 1.0 |

| Renal disease | 3 (3) | 10 (10) | 0.049* |

| Other | 22 (21) | 27 (26) | 0.42 |

| Physical examination, n (%) | |||

| Jaundice | 45 (42) | 38 (36) | 0.40 |

| Ascites | 65 (61) | 54 (51) | 0.17 |

| Portal-systemic encephalopathy | 19 (18) | 19 (18) | 1.0 |

| Severe muscle wasting (2+ or 3+ on 0–3+ scale) | 50 (47) | 67 (64) | 0.026* |

| Delerium tremens in alcoholics | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.00 |

| PSE index – median (interquartile range) | 0 (0–0.15) | 0 (0–0.15) | 0.46 |

| Child’s risk class, n (%) | 0.71 | ||

| A (5 to 8 points) | 32 (30) | 26 (25) | |

| B (9 to 11 points) | 46 (43) | 49 (47) | |

| C (12 to 15 points) | 28 (26) | 30(29) | |

| Child’s risk class points, mean/median | 10.1/10 | 10.0/10 | 0.76 |

Statistically significant difference.

EPCS, emergency portacaval shunt; EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy; PSE, portal-systemic encephalopathy; UCSD, University of California, San Diego.

Table 2 summarizes important findings on liver biopsy, upper endoscopy, and some of the laboratory blood tests obtained at the time of entry in the study. Histologic proof of cirrhosis of the liver was obtained in all patients by percutaneous needle liver biopsy in the EST group and wedge liver biopsy obtained at operation in the EPCS group. All patients had sizable esophageal varices on upper endoscopy, with active bleeding or evidence of recent acute bleeding.

Table 2.

Findings on Liver Biopsy, Endoscopy, and Laboratory Blood Tests at Time of Study Entry in Patients with Cirrhosis and Bleeding Esophageal Varices Randomized to Endoscopic Sclerotherapy or Emergency Portacaval Shunt

| Findings | EST | EPCS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis on liver biopsy, n (%) | 106 (100) | 105 (100) | 1.0 |

| Esophageal varices on endoscopy, n (%) | 106 (100) | 105 (100) | 1.0 |

| Size 2+ to 4+ (on scale of 0–4+), n (%) | 102 (96) | 105 (100) | 0.68 |

| Active bleeding, n (%) | 41 (39) | 29 (28) | 0.11 |

| Clot on varices, n (%) | 53 (50) | 51 (49) | 0.89 |

| Red color signs on varices, n (%) | 67 (63) | 66 (63) | 1.00 |

| Gastric varices on endoscopy, n (%) | 19 (18) | 17 (16) | 0.86 |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy, n (%) | 23 (22) | 22 (21) | 1.00 |

| Laboratory blood tests, median/mean (range) | |||

| Lowest hemoglobin, g/dL | 8.0/8.4 (2.0–8.1) | 8.0/8.0 (2.6–11.9) | 0.40 |

| Lowest hematocrit, % | 23.4/22.8 (6.0–39.4) | 23.5/23.7 (11.0–35.4) | 0.46 |

| Lowest platelet count, 1,000/mm3 | 87/97.6 (25–340) | 76/95.4 (15–268) | 0.36 |

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL | |||

| Direct | 0.5/1.1 (0.1–12.0) | 0.4/0.7 (0.1–3.7) | 0.12 |

| Total | 2.4/3.5 (0.6–15.2) | 1.9/27 (0.4–148) | 0.25 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.6/2.6 (1.4–3.9) | 2.5/2.6 (1.4–4.5) | 0.49 |

| Aspartate transaminase, IU/L | 73/116 (16–1,359) | 66/88 (16–582) | 0.37 |

| Alanine transaminase, IU/L | 35/54 (11–432) | 36/47 (9–582) | 0.56 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L | 86/95 (1.3–367) | 79/88 (29–218) | 0.20 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.3/2.8 (0.6–5.8) | 1.3/1.4 (1.1–2.6) | 0.39 |

| Arterial ammonia, µmol/L | 76/93 (33–253) | 75/92 (26–497) | 0.83 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8/1.4 (0.4–10) | 0.8/1.0 (0.5–2.7) | 0.89 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/Dl | 22/27 (7–85) | 21/23 (6–69) | 0.22 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 133/152 (74–548) | 135/157 (60–368) | 0.44 |

| Blood alcohol 0.01% or higher, n (%) | 9 (8) | 13 (12) | 0.29 |

| Blood alpha fetoprotein, ng/mL, mean (range) | 4 (0–18) | 4 (0–10) | 0.84 |

| Positive HBV or HCV serology, n (%) | 37 (35) | 44 (42) | 0.32 |

EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy; EPCS, emergency portacaval shunt; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Rapidity of therapy

Table 3 provides data on rapidity of BEV therapy. The mean and median times from onset of bleeding to entry in the San Diego BEV Study were <20 hours in both groups of patients. The mean and median times from onset of bleeding to the start of EST or EPCS were <24 hours. After initial contact at UCSD Medical Center, primary therapy was started in <8 hours in every patient who received EST, and in 102 of the 105 patients who underwent EPCS, clearly a reflection of the rapidity with which the diagnostic workup was performed. The mean time from initial contact to EST was 3.1 hours, and to EPCS was 4.4 hours. Patients who were transferred to UCSD Medical Center from outside facilities on average spent <12 hours in the referring hospitals. Before entry into the study, active bleeding had been observed within 4 hours in 84% of the 211 patients. Without doubt, the study involved evaluation of emergency treatment of acute BEV.

Table 3.

Rapidity of Therapy for Patients with Cirrhosis and Bleeding Esophageal Varices Randomized to Endoscopic Sclerotherapy or Emergency Portacaval Shunt

| Hours | EST (n = 106) | EPCS (n = 105) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median/mean | Range | Median/mean | Range | ||

| Onset bleeding to study entry | 12/19.8 | 0–144 | 16/19 | 0–95 | 0.30 |

| Onset bleeding to primary therapy | 15/23.3 | 3–147 | 19/21.5 | 2.6–100 | 0.056 |

| Study entry to primary therapy | 2.5/3.1 | 0.8–8 | 3.4/4.4 | 1.4–24.3 | <0.001* |

| n >8h | 0 | 3 | |||

| % >8 h | 0 | 2.9 | |||

| Transfer patients, n (%) | 71 (67) | 80 (76) | 0.17 | ||

| Onset of bleeding to entry in referring hospital | 4.05/10.4 | 0–127 | 3.75/9.7 | 0–83.6 | 0.92 |

| Entry into referring hospital to study entry | 7.2/11.8 | 1.5–53 | 8.4/11.6 | 0–53 | 0.56 |

| Last observation of bleeding to study entry | 0/1.9 | 0–32 | 0/2.5 | 0–30 | 0.76 |

| ≤4 h, % of group | 84 | 84 | 0.94 | ||

| >4 h, % of group | 16 | 16 | 1.00 | ||

Statistically significant difference.

EPCS, emergency portacaval shunt; EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy.

Control of bleeding

Table 4 provides data on control of variceal bleeding by EST and EPCS. Before primary therapy, patients in the EST group received a mean 4.5 U of PRBC transfusion (range 2 to 12 U), and patients in the EPCS group required a mean 5.8 U of PRBC transfusion (range 2 to 17 U). In an attempt to control bleeding temporarily while the diagnostic workup was in progress, 175 patients were given a continuous IV infusion of vasopressin. Patients whose electrocardiogram was abnormal or who had a proved or suggestive history of coronary artery disease were not given vasopressin. Bleeding decreased or stopped in 77% of the actively bleeding patients in the EST group and 69% in the EPCS group. Although bleeding stopped spontaneously in some patients who did not receive vasopressin, it appears likely that vasopressin was often effective in temporarily controlling bleeding.

Table 4.

Control of Bleeding and Survival in Patients with Bleeding Esophageal Varices Randomized to Endoscopic Sclerotherapy or Emergency Portacaval Shunt

| Variable | EST (n = 106) | EPCS (n = 105) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control of bleeding, n (%) | |||

| Temporary during workup | |||

| Received vasopressin intravenously | 95 (90) | 80 (76) | 0.012* |

| Bleeding at start of vasopressin infusion | 47 (49) | 55 (69) | 0.014* |

| Bleeding decreased or stopped | 36 (77) | 38 (69) | 0.51 |

| Permanent by EST or EPCS | |||

| Indeterminate, nonbleeding death ≤14 d | 4 (4) | 12 (11) | 0.040* |

| Successful control excluding indeterminates for at least | |||

| 14 d | 22 (21) | 93 (100) | <0.001* |

| 30 d | 20 (20) | 89 (100) | <0.001* |

| >30 d | 20 (20) | 89 (100) | <0.001* |

| Declaration of primary therapy failure, n (%) | 81 (79) | 0 (0) | <0.001* |

| Required ≥6 U PRBC in first 7 d | 15 (19) | –– | |

| Required ≥8 U PRBC in any 12 mo | 47 (58) | –– | |

| Recurrent variceal bleeding after variceal obliteration was declared | 27 (33) | –– | |

| More than one criterion for failure | 8 (10) | –– | |

| PRBC transfusion, U, mean/median (range) | |||

| Index hospitalization | |||

| Before primary therapy | 4.5/4 (2–12) | 5.8/5 (2–17) | <0.001* |

| During primary therapy | 0.6/0 (0–7) | 6.3/3 (0–68) | <0.001* |

| ”Catch–up” after primary therapy | 0.2/0 (0–4) | 1.2/0 (0–21) | 0.001* |

| Posttherapy bleeding | |||

| Variceal | 4.4/0 (0–37) | 0/0 (0–0) | <0.001* |

| Nonvariceal | 0.3/0 (0–11) | 1.8/0 (0–29) | 0.059 |

| Total PRBC units | 10.0/7 (2–44) | 15.0/10 (2–81) | <0.001* |

| Readmissions for bleeding | |||

| Variceal bleeding | 6.8/2 (0–60) | 0.4/0 (0–26) | <0.001* |

| Nonvariceal bleeding | 3.8/0 (0–38) | 3.5/0 (0–33) | 0.23 |

| Total PRBC units | 10.6/7 (0–60) | 3.9/0 (0–33) | <0.001* |

| Total PRBC units for variceal bleeding | 15.8/14 (2–64) | 13.6/10 (2–73) | 0.037* |

| Overall survival (Pr/95% CI) | <0.001* | ||

| 30–d | 0.88 (0.82, 0.94) | 0.87 (0.80, 0.93) | |

| 1–y | 0.72 (0.64, 0.81) | 0.81 (0.74, 0.89) | |

| 2–y | 0.54 (0.45, 0.64) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.86) | |

| 3–y | 0.44 (0.36, 0.55) | 0.75 (0.67, 0.84) | |

| 4–y | 0.35 (0.27, 0.45) | 0.74 (0.66, 0.83) | |

| 5–y | 0.21 (0.14, 0.30) | 0.73 (0.65, 0.82) | |

| 10–y | 0.09 (0.05, 0.17) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.56) | |

| 15–y | 0.09 (0.05, 0.17) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.56) | |

| Median survival, y (95% CI) | 2.48 (1.58, 3.76) | 6.17 (5.60, 10.37) | |

| Survival by Child’s risk class (Pr/95% CI) | |||

| 5–y Child’s class (Pr/95% CI) | |||

| A | 0.38 (0.24, 0.59) | 0.89 (0.83, 1.00) | 0.003* |

| B | 0.15 (0.08, 0.30) | 0.76 (0.64, 0.89) | <0.001* |

| C | 0.11 (0.04, 0.31) | 0.57 (0.41, 0.78) | 0.005* |

| 10–y Child’s class (Pr/95% CI) | |||

| A | 0.18 (0.08, 0.38) | 0.62 (0.45, 0.83) | 0.003* |

| B | 0.07 (0.02, 0.20) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.61) | <0.001* |

| C | 0.04 (0.01, 0.25) | 0.33 (0.20, 0.55) | 0.005* |

| Median survival, y (95% CI) | |||

| A | 4.62 (4.08, 6.34) | 10.43 (>5.92) | 0.003* |

| B | 2.61 (1.65, 3.96) | 6.19 (>5.44) | <0.001* |

| C | 0.58 (0.12, 2.36) | 5.30 (0.70, 10.16) | 0.005* |

| Survival by direct UCSD admission versus transfer from outside UCSD (Pr/95% CI) | 0.48 | ||

| Direct UCSD admission | |||

| 5 y | 0.17 (0.08, 0.36) | 0.58 (0.42, 0.80) | |

| 10 y | 0.11 (0.05, 0.29) | 0.52 (0.27, 0.66) | |

| Transfer from outside UCSD | |||

| 5 y | 0.24 (0.16, 0.36) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.88) | |

| 10 y | 0.08 (0.03, 0.18) | 0.45 (0.36, 0.58) | |

| Mean survival, y (95% CI) | |||

| Direct UCSD admission | 2.71 (0.72, 4.51) | 5.28 (>2.80) | |

| Transfer from outside UCSD | 2.45 (1.59, 3.76) | 6.25 (5.81, 11.03) | |

| Rescue portacaval shunt in EST group – effect on median survival, y (95% CI) | |||

| Successful EST (n = 21) | 2.76 (1.52, 7.35) | — | 0.48 |

| Failed EST (n = 81) | 2.71 (1.65, 3.92) | — | |

| Rescue shunt–failed EST (n = 50) | 3.01 (1.65, 4.34) | — | 0.098 |

| No rescue shunt–failed EST (n = 31) | 2.36 (0.72, 4.34) | — | |

| Overall survival: rescue shunt (n = 50) versus primary EPCS (n = 105) | 3.01 (1.65, 4.34) | 6.18 (5.61, 10.38) | <0.001* |

| Postoperative survival: rescue shunt (n = 50) versus primary EPCS (n = 105) | 1.99 (1.34, 3.73) | 6.18 (5.61, 10.38) | <0.001* |

Statistically significant difference.

EPCS, emergency portacaval shunt; EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy; Pr, probability; PRBC, packed red blood cells; UCSD, University of California, San Diego.

With regard to both immediate and longterm control of bleeding, there was a striking and highly significant difference between EST and EPCS. Excluding indeterminate deaths within 14 days from causes other than bleeding (4 in the EST group and 12 in the EPCS group), EST achieved longterm control of bleeding in only 20% of patients. In contrast, EPCS promptly and permanently controlled bleeding in every patient.

Failure of EST took several forms, each of which fulfilled the definition of failure established by the study protocol. Variceal bleeding that continued or recurred during the first 7 days after initial EST and required ≥6 U of blood transfusion was the cause of failure in 15 patients. Recurrent variceal bleeding that required ≥8 U of blood transfusion during any 12-month period after the index hospitalization was the reason for a declaration of failure in 47 patients. Finally, failure was declared in 27 patients in whom variceal bleeding developed after an experienced coinvestigator gastroenterologist or endoscopist had previously declared that the esophageal varices were obliterated or gone. Bleeding in eight of these same patients required ≥8 U of blood transfusion, so they met two criteria that warranted a declaration of failure.

The requirement for PRBC blood transfusions is summarized in Table 4. Not surprisingly, the number of blood transfusions needed during a major surgical operation such as EPCS was substantially greater than the transfusion requirement during EST. But soon after primary therapy, patients in the EST group required significantly more units of PRBC than those in the EPCS group because of continued or recurrent bleeding. In the longterm, patients in the EST group had readmissions to the hospital for recurrent BEV that required blood transfusions; patients in the EPCS group rarely experienced UGI bleeding (p = <0.001). Overall, patients treated by EST received more units of blood than patients who underwent EPCS.

Operative and endoscopic data and technical complications

Direct side-to-side PCS was performed in 94% of the 105 patients who underwent EPCS and 92% of the 50 patients who failed EST and underwent rescue PCS. Mean operative time was 4.0 hours (range 2.3 to 13.8 hours) for EPCS and 3.8 hours (range 2.4 to 8.9 hours) for rescue PCS. Portal vein thrombosis requiring thrombectomy before accomplishing the shunt was found in six patients in each shunt group. Immediate control of bleeding was obtained in all shunted patients. Estimated blood loss averaged 3,094 mL in the EPCS group and 2,208 mL in the rescue PCS patients. Accordingly, the requirement for PRBC transfusion averaged 6.3 U in the EPCS group and 4.9 U in patients who underwent rescue PCS. PCS eliminated portal hypertension in all patients. The portal vein-inferior vena cava pressure gradient before PCS averaged 244 mm saline in the EPCS group and 245 mm saline in the rescue PCS patients. Direct PCS reduced the mean pressure gradient to 17 mm and 21 mm, respectively. The postshunt portal vein-inferior vena cava gradient in mm saline was ≤50 mm in 96% of the EPCS patients and 98% of the rescue PCS patients.

Patients randomized to EST underwent a median of 5 EST sessions (range 1 to 18 sessions). The median time per EST session was 20 minutes (range 10 to 100 minutes). The median number of injections of sclerosing solution per EST session was 9 (range 1 to 35 injections). The median volume of sclerosant per injection was 0.7 mL, and the median total volume of sclerosant per EST session was 7.0 mL. The median number of EST sessions required to obtain obliteration of esophageal varices was 9 (range 3 to 18 sessions). Obliteration of esophageal varices was achieved during survival in 43 of the 106 patients (40.6%). Many patients died before obliteration was achieved.

During the course of EST, sclerotherapy-related esophageal ulcers developed in, 66% of the patients, 56% experienced a pleural effusion, 40% experienced dysphagia, 26% reported esophageal pain, and 15% experienced an esophageal stricture that invariably resolved in response to endoscopic dilation. EST caused an esophageal perforation in five patients (5%) early in the study. The perforation was ultimately responsible for the death of two of the five patients.

After EPCS, a pleural effusion developed in 28% of the patients 11% experienced an ascitic leak from the abdominal incision, 10% experienced a wound infection, and 7% experienced an incisional hernia. Two patients experienced venous thrombosis; in one, the portal vein was involved and in the other, the splenic vein. The PCS remained permanently patent in 98% of the patients.

Survival

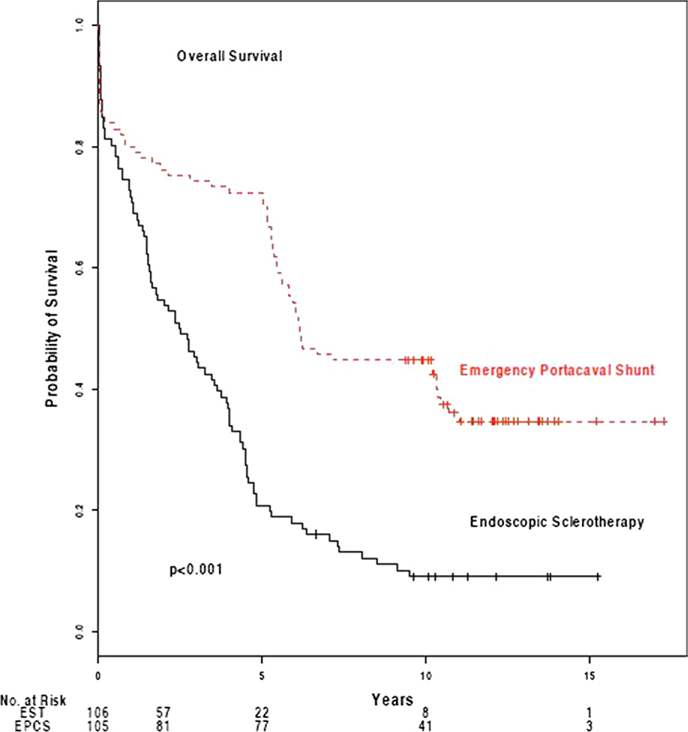

Table 4 shows data on survival and Figure 2 shows the 15-year Kaplan-Meier estimated survival plots for the EST and EPCS groups. The 30-day survival rates of 88% and 87%, respectively, were similar. Subsequently, however, there were highly significant differences in the survival rates of the two study groups at all time intervals. The 1-, 5-, 10-, and 15-year survival rates in the EST group were 72%, 21%, 9%, and 9%, respectively, and in the EPCS group were 81%, 73%, 46%, and 46%, respectively. One hundred five of the 106 patients in the EST group and 98 of the patients in the EPCS group were eligible for 10-year followup. The remaining eight patients had followup for 9.4 to 9.9 years. No patients were lost to followup. When patients moved from the local four-county area, followup arrangements that included data collection were made with a physician usually well known to us, who practiced in the area near the patient’s new residence. These physicians completed study data forms and sent them to us after each visit.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival after endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) (n = 106) and emergency portacaval shunt (EPCS) (n = 105).

During the course of the study, 96 patients in the EST group (91%) and 67 patients in the EPCS group (64%) died. Hepatic failure was the primary cause of death in 38% of patients who underwent EST and 33% of those who received EPCS. BEV was the main immediate cause of death in 26% of EST patients, and a major secondary cause in an additional 18%. In contrast, variceal bleeding played no role in the death of the EPCS patients, a clear difference in the effectiveness of the two forms of therapy in controlling bleeding (p < 0.001).

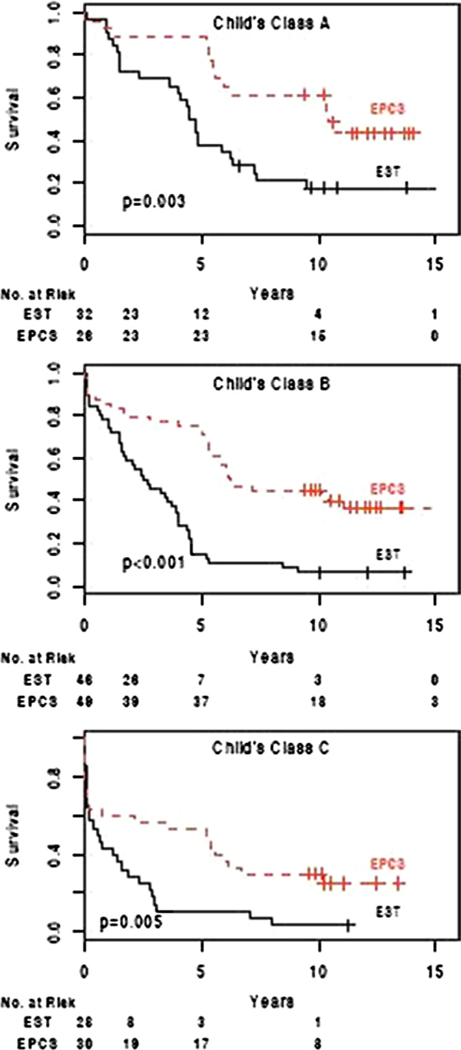

The survival rate, as expected was related to the severity of hepatic disease at the time of entry in the study, as expressed by Child’s risk classes and shown in Table 4 and Figure 3. In the EST group, 5-year survival rates in Child’s classes A, B, and C were 38%, 15%, and 11%, respectively, and 10-year survival rates were 18%, 7%, and 4%, respectively. In contrast, in the EPCS group, the corresponding 5- and 10-year survival rates in Child’s risk classes A, B, and C were 89%, 76%, and 57%, and 62%, 45%, and 33%. EPCS resulted in substantial longterm survival of patients in Child’s risk class C, who had the most advanced cirrhosis of the liver.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival in Child’s risk classes A, B, and C after endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) (n = 106) and emergency portacaval shunt (EPCS) (n = 105).

The survival rate was not influenced significantly by the route of entry into the BEV study. Overall, the survival rates of patients who entered UCSD Medical Center directly were similar to those of patients who were transferred to UCSD Medical Center from hospitals in San Diego County or the three adjacent counties. Comparing direct admission with transfer, survival rates at 10 years were 11% and 8%, respectively, in the EST group, and 52% and 45%, respectively, in the EPCS group.

Patients in whom EST was successful in immediate and longterm control of variceal bleeding survived a median 2.76 years; those in whom EST failed survived a median 2.71 years. Median survival was only 0.04 years longer when EST was successful than when it failed, an insignificant difference. When EST failed, patients who underwent a rescue portacaval shunt survived a median 3.01 years overall; those who, for whatever reason, did not undergo a rescue PCS survived a median 2.36 years. But median survival after rescue shunt was only 1.99 years, and was not as long as the survival rate after successful emergency and longterm EST. Thirty-eight percent of patients who failed EST did not receive a rescue or salvage portacaval shunt for a number of reasons, including dying from variceal hemorrhage at home or at a distant hospital. Failure to take advantage of rescue treatment is a reflection of the realities of treating BEV in the cirrhotic population. The results of this study do not support the concept of using EST as initial therapy to be followed, in those in whom EST fails, by rescue PCS.

Portal-systemic encephalopathy

Detailed results of the important complication of PSE will be reported in a separate communication. In patients who survived 30 days and left the hospital, recurrent PSE developed in 35% of the EST group and 15% of the EPCS group, a highly significant difference (p = 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The San Diego Bleeding Esophageal Varices Study was unique in at least five respects: it involved all patients with acute BEV, without selection at our hospital; it was a community-wide endeavor in which 72% of patients were promptly referred to our institution by community physicians; the diagnostic workup was completed at the bedside within a mean 3.1 to 4.4 hours of initial contact; definitive therapy of variceal hemorrhage was initiated within 8 hours of initial contact in 208 of the 211 patients; and followup for 9.4 years or until death was 100% and for 10 or more years or until death was 96%.

To date, there have been no reports of randomized controlled trials in which emergency EST or ligation has been compared with emergency portal-systemic shunt in a broad spectrum of patients with cirrhosis and acute BEV. In 1984 and 1987, Cello and coworkers10,11 reported the results of the only published randomized controlled trial comparing EPCS with emergency and longterm EST, but it was limited to patients who had “the single worst criterion for Child’s class C” and had received ≥6 U of blood transfusion. The features of that trial were very different from those of the trial reported here, and the conclusions are not broadly applicable to the emergency treatment of the bleeding cirrhotic population. The time from the onset of the bleeding episode to randomization was not mentioned. After admission, specific treatment was delayed for a mean of 51.3 to 67.4 hours. The 31 EPCS operations were performed by 7 surgeons. One attempt at EPCS was abandoned, two shunts failed, and five patients with shunts had postoperative UGI hemorrhage; all of these patients died. Postoperative shunt patency was not determined. Only 44% of the EPCS group and 49% of the emergency EST group survived 30 days and were discharged from the hospital alive. The mean followup period was 530 days (range 21 to 1,830 days), and the survival rate at 18 months was 12.5% in the EPCS group and 28.1% in the EST group. If the unique definition of Child’s class C adopted by Cello and associates10,11 were used in our study, 185 of the 211 patients (88%) would have been considered in Child’s class C and the 18-month survival rate in these reclassified C patients would have been 76% compared with 12.5% in the study by Cello and associates.10,11 These striking differences in outcomes are undoubtedly the result of marked differences in patient populations, design, and conduct of the two studies.

Three randomized controlled trials have been reported in which direct PCS, sometimes called total shunt, was compared with EST in elective treatment directed at prevention of rebleeding in patients who had recovered from a variceal hemorrhage.23–25 It is difficult to draw conclusions from these studies because they involved a small number of highly selected subjects who were followed up for short periods of time. Most important, the results of these studies are clearly not applicable to the emergency treatment of BEV.

Four randomized controlled trials have been reported in which distal splenorenal shunt, a so-called selective shunt, was compared with EST in elective treatment aimed at prevention of rebleeding in patients who had recovered from one or more episodes of bleeding from esophageal varices.26–30 All four trials excluded patients in Child’s class C and were highly selective, involving fewer than one-third of the cirrhotic patients who were treated for variceal hemorrhage at the four institutions. In all four studies, recurrent variceal bleeding was much more frequent in the EST group than in the distal splenorenal shunt group. Nevertheless, there was no difference in survival rates between the two groups of patients in any of the four studies. In addition, two of the studies observed a significant incidence of shunt thrombosis amounting to 10% and 14%, respectively, after distal splenorenal shunt.27–29 Although these randomized trials of elective therapy in selected patients are interesting, they have no direct bearing on the comparative effectiveness of PCS and EST in emergency treatment of BEV.

For the past 3 decades, EST has been used throughout the world as a primary emergency and longterm treatment of BEV. Reports of the results of EST have been numerous and the literature on this therapeutic modality is vast. In a recent report on 287 consecutive patients by Krige and associates31 from the University of Cape Town, a center with a long and large experience with EST, 90 patients died within 3 months, 15 patients were lost to followup within 3 months, and recurrent varices ultimately developed in 57% of patients who survived more than 3 months; half of these had more variceal bleeding Cumulative survivals by life-table analysis at 3, 5, and 10 years were 42%, 26%, and 13%, respectively. Complications were frequent, occurring in one-fourth of all patients treated with EST and in more than two-thirds of patients overall. The authors concluded that “ultimate survival and outcomes of treatment in this consecutive cohort of patients was disappointing” and “there is increasing recognition that an important limitation of longterm sclerotherapy is the substantial incidence of rebleeding…”

Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is a more recently practiced alternative to EST. A sizable number of randomized controlled trials comparing EVL and EST have been reported, with variable results and conclusions.32 In elective treatment of patients who have recovered from an episode of BEV, EVL has replaced EST in many centers as a result of studies showing more rapid eradication of varices, lower rates of recurrent bleeding, and fewer complications. Nevertheless, in a recent survey of 93 gastroenterologists who treated 725 patients in various centers, EST was used more frequently than EVL for control of variceal rebleeding, and as frequently as EVL for initial control of acute bleeding.33 Several recent trials reported a significantly higher failure rate with band ligation of actively bleeding varices, and an overall higher recurrence rate of varices in patients treated by EVL.32 EST has been reported to be more cost-effective if active variceal hemorrhage is present at the index endoscopy procedure.34 Most discouraging, none of nine randomized clinical trials showed a statistically significant difference in survival rates between EVL and EST.32

EPCS, as it was applied in the San Diego Bleeding Esophageal Varices Study, which involved a direct anastomosis between the portal vein and inferior vena cava, invariably and permanently controlled variceal bleeding and resulted in longterm survival that was markedly greater than that obtained by EST, even when rescue PCS was used as a crossover therapy to salvage patients in whom EST failed. These results are consistent with our past extensive experience with EPCS12–16 and the survival rate is higher than the survival rates reported by other investigators who used portal-systemic shunts as emergency treatment or to prevent rebleeding.23–30,35–37 Undoubtedly, many factors contributed to the better outcomes, some of them subtle and difficult to measure. But we believe that at least four factors played a major role in the results achieved by EPCS in our study. The first was simplification of the diagnostic workup by eliminating time-consuming, often invasive, and unnecessary studies as a routine, including visceral angiography, CT, catheterization of the hepatic veins for wedged hepatic venous pressure measurements, magnetic resonance angiography, radioisotope measurements of hepatic blood flow, and scintiscanning of the liver and spleen. The entire diagnostic workup, as a result, was performed at the bedside in a mean 4.4 hours, without moving the patient out of the ICU.

We believe the second factor responsible for the favorable results of EPCS in our study was the development and refinement of an organized system of preoperative and postoperative care guided by a specific protocol. Patients in both arms of our randomized trial were admitted directly to the same ICU where personnel had specific training and long experience in the care of patients with cirrhosis of the liver, and they were returned to that same unit postoperatively. Care of all patients in both arms of the trial was supervised by one group of attending physicians throughout the study.

In our opinion, the third factor responsible for the results in our study was the rigorous, lifelong program of the followup study, in which there was an intensification of efforts to obtain dietary protein control and abstinence from alcohol. Patients were seen in the portal hypertension clinic monthly for the first postoperative year and every 3 months thereafter. A dietitian trained in the care of postshunt patients with cirrhosis of the liver was stationed in the clinic to counsel the patients at each visit on restriction of dietary protein intake to 60 g/d. Serious efforts were made to enroll all patients who were alcoholics in an alcohol rehabilitation program, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, or a similar program at our own institution. Our patients with shunts proved to be more receptive to rehabilitation therapy than many alcoholics, perhaps because of their almost lethal experience with massive bleeding and EPCS. The frequency of permanent abstinence, as a result, was 62% in the EPCS group. Without doubt, resumption of alcoholism reduces the longterm survival rate.38–40

The fourth factor responsible for the success of EPCS undoubtedly was the low incidence of early and longterm shunt thrombosis. The PCS remained permanently patent in 98% of the patients. This outcome is consistent with our past experience with approximately 2,000 side-to-side PCS’s, in which occlusion of the anastomosis developed in 0.5%. Thrombosis of a portal-systemic shunt is usually followed by recurrence of variceal bleeding and often death. Shunt occlusion represents a serious technical failure of surgical therapy. High rates of occlusion of various types of shunts have been reported from centers known for expertise in treatment of portal hypertension. One publication that summarized results of randomized controlled trials reported shunt occlusion rates of 12%, 15%, and 29% for conventional portal-systemic shunts, and 14%, 17%, and 23% for distal splenorenal shunts.41 Several reports of mesocaval interposition shunts from well-known centers described occlusion rates of 24%, 33%, and 53%.42–44 The major shortcoming of the widely used TIPS procedure in the treatment of BEV has been a high rate of stenosis and occlusion, and a resultant high incidence of PSE.45–50 We completed a longterm randomized controlled trial of TIPS versus EPCS and are analyzing the results for future publication.

A frequent criticism of portal-systemic shunt is the observation or assumption that control of bleeding is achieved at the cost of a high rate of PSE. There is a widespread belief that longterm EST of BEV is associated with a substantially lower rate of PSE than treatment by portal-systemic shunt.51,52 The results of our randomized controlled trial are contrary to both of these conclusions. On initial contact before entry in the trial, 19% of patients in each group had PSE, most likely from gastrointestinal bleeding. A history of PSE was noted in 18% of the EST patients and 29% of the EPCS patients. Chronic, recurrent PSE that required treatment and diminished the quality of life developed in 35% of patients treated by EST and 15% of patients who received EPCS—a significant difference (p = 0.001). Forty percent of the patients who experienced posttherapy PSE had PSE pretherapy. This relatively low incidence of PSE in patients with PCS is consistent with our past experience.12–16 Experience with the patients in this study, and the results in our other studies of EPCS12–16 demonstrate that a low incidence of PSE is possible when, with the help of rigorous followup, patients abstain from alcohol and comply with a diet of moderate protein restriction.

In conclusion, in this randomized controlled trial of emergency treatment of acutely bleeding esophageal varices in 211 unselected, consecutive patients with cirrhosis of all grades of severity, EPCS was found to be superior in every respect to emergency and longterm EST aimed at variceal obliteration, even when failure of EST was treated by crossover PCS as salvage therapy. EPCS promptly and permanently stopped variceal bleeding in virtually all patients, rarely became occluded or lost its effectiveness, was accomplished with a relatively low incidence of subsequent PSE as a result of rigorous lifelong followup, and produced longterm survival rates that were significantly greater than those resulting from EST. The widespread practice of using surgical or radiologic procedures mainly or only as salvage for failure of endoscopic therapy is not supported by the results of this trial.

Acknowledgment:

We thank the many residents in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Surgery who played a major role in the care of patients in this study. We thank Professors Harold O Conn, Haile T Debas, and Peter Gregory, who served voluntarily as an External Advisory and Monitoring Committee. We thank the many physicians practicing in the counties of San Diego, Imperial, Orange, and Riverside who helped with patient recruitment, referral, and longterm followup.

Supported by grant 1R01 DK41920 from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Surgical Education and Research Foundation.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BEV

bleeding esophageal varices

- EPCS

emergency portacaval shunt

- EST

endoscopic sclerotherapy

- EVL

endoscopic variceal ligation

- PCS

portacaval shunt

- PRBC

packed red blood cells

- PSE

portal-systemic encephalopathy

- TIPS

transjugular intrahepatic portal-systemic shunt

- UCSD

University of California, San Diego

- UGI

upper gastrointestinal

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Marshall J Orloff, Departments of Surgery, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Jon I Isenberg, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Henry O Wheeler, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Kevin S Haynes, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Horacio Jinich-Brook, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Roderick Rapier, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Florin Vaida, Family and Preventive Medicine/Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

Robert J Hye, Departments of Surgery, University of California, San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, CA..

REFERENCES

- 1.Graham DY, Smith H. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1981;80:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith JL, Graham DY. Variceal hemorrhage: a critical evaluation of survival analysis. Gastroenterology 1982;82:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burroughs AK, Mezzanotte G, Phillips A, et al. Cirrhotics with variceal hemorrhage: the importance of the time interval between admission and the start of analysis for survival and rebleeding rates. Hepatology 1969;9:801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bornman PC, Krige JE, Terblanche J. Management of oesophageal varices. Lancet 1994;353:1079–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson P, Sutton R. Portosystemic shunts versus endoscopic therapy for variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 1 Art. No. CD000553. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000553.Pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orloff MJ, Duguay LR, Kosta LD. Criteria for selection of patients for emergency portacaval shunt. Am J Surg 1977;134: 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkelsen WP. Therapeutic portacaval shunt. Preliminary data on controlled trial and morbid effects of acute hyaline necrosis. Arch Surg 1974;108:302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terblanche J, Burroughs AK, Hobbs KEF. Controversies in the management of bleeding oesophageal varices. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1393–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology 1995;22:332–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cello P, Brendell JH, Crass RA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus portacaval shunt in patients with severe cirrhosis and variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 1984;311:1589–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cello JP, Grendell JH, Crass RA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus portacaval shunt in patients with severe cirrhosis and acute variceal hemorrhage. Long-term follow-up. N Engl J Med 1987;316:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orloff MJ. Emergency portacaval shunt: a comparative study of shunt, varix ligation, and nonsurgical treatment of bleeding esophageal varices in unselected patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg 1967;166:456–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orloff MJ, Bell RH Jr, Hyde PV, Skovolocki WP. Long-term results of emergency portacaval shunt for bleeding esophageal varices in unselected patients with alcohol cirrhosis. Ann Surg 1980;192:325–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Rambotti M, Girard B. Is portal-systemic shunt worthwhile in Child’s class C cirrhosis: Longterm results of emergency shunt in 94 patients with bleeding varices. Ann Surg 1992;216:256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orloff MJ, Bell RH Jr, Orloff MS, et al. Prospective randomized trial of emergency portacaval shunt and emergency medical therapy in unselected cirrhotic patients with bleeding varices. Hepatology 1994;20:863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Orloff SL, et al. Three decades of experience with emergency portacaval shunt for acutely bleeding esophageal varices in 400 unselected patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180:257–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001;285:1987–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:663–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orloff MJ, Orloff SL, Orloff MS. Portacaval shunts: side-to-side and end-to-side. In: Clavien P-A, Saar MG, Fong Y, eds. Atlas of upper gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2007: 687–702. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conn HO, Liberthal MM. The hepatic coma syndromes and lactulose Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Child CG III, Turcotte JG. Surgery and portal hypertension. In: Child CG III, ed. The liver and portal hypertension Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1964:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell DP, Parker DE, Anagnostopoulos CE. Survival prediction in portacaval shunt: a computerized statistical analysis. Am J Surg 1973;126:748–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korula J, Yelin A, Yamada S, et al. A prospective randomized controlled comparison of chronic endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy and portalsystemic shunt for variceal hemorrhage in Child’s class A cirrhotics: a preliminary report. Gastroenterology 1987;92:1745. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Planas R, Boix J, Broggi M, et al. Portacaval shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1991;100:1078–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isaksson B, Jeppsson B, Gengtsson F, et al. Mesocaval shunt or repeated sclerotherapy: effects on rebleeding and encephalopathy—a randomized trial. Surgery 1995;117:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson JM, Kutner MH, Millikan WJ, et al. Endoscopic variceal sclerosis compared with distal splenorenal shunt to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding in cirrhosis, a prospective randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rikkers LF, Burnett DA, Volentine GD, et al. Shunt surgery versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for long-term treatment of variceal bleeding. Early results of a randomized trial. Ann Surg 1987;206:261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rikkers LF, Jin G, Burnett DA, et al. Shunt surgery versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for variceal hemorrhage: late results of a randomized trial. Am J Surg 1993;165:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terés J, Bordas JM, Bravo D, et al. Sclerotherapy vs. distal splenorenal shunt in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 1987;7:430–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spina GP, Santambrogrio R, Opocher E, et al. Distal splenorenal shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. First stage of a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 1990;211:178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krige JEJ, Katze UK, Bornman UC, et al. Variceal recurrence, rebleeding, and survival after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in 287 alcoholic cirrhotic patients with bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Surg 2006;244:764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krige JE, Shaw JM, Bornman PC. The evolving role of endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices. Wld J Surg 2005;29: 966–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Peura D, et al. An assessment of the management of acute bleeding varices: a multicenter prospective member-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:2424–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gralnek IM, Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, et al. The economic impact of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: cost-effectiveness implications of endoscopic therapy. Hepatology 1999;29:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villeneuve J-P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Duguay L, et al. Emergency portacaval shunt for variceal hemorrhage. A prospective study. Ann Surg 1987;206:48–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soutter DI, Langer B, Taylor BR, Greig P. Emergency portosystemic shunting in cirrhotics with bleeding varices––-a comparison of portacaval and mesocaval shunts. HPB Surg 1989;1: 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spina GP, Santambrogio R, Opocher E, et al. Emergency portosystemic shunt in patients with variceal bleeding. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1990;171:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borowsky SA, Stroma S, Lott E. Continued heavy drinking and survival in alcoholic cirrhotics. Gastroenterology 1981;80: 1405–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell WJ, Klatskin G. Duration of survival in patients with Laennec’s cirrhosis. Am J Med 1968;98:695–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capone RR, Buhac I, Kohberg RC, Balint JA. Resistant ascites in alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 1978;23:867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grace ND, Conn HO, Resnick RH, et al. Distal splenorenal versus portal systemic shunts after haemorrhage from varices: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 1988;8:1475–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terpstra OT, Ausema B, Bruining HA, et al. Late results of mesocaval interposition shunting for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1987;74:787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith RB, Warren WD, Salam AA, et al. Dacron interposition shunts for portal hypertension. An analysis of morbidity correlates. Ann Surg 1980;192:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fletcher MS, Dawson JL, Williams R. Long term follow-up of interposition mesocaval shunting in portal hypertension. Br J Surg 1981;68:485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helton WS, Belshaw A, Althaus S, et al. Critical appraisal of the angiographic portacaval shunt (TIPS). Am J Surg 1993;165: 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LaBerge JM. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt–role in treating intractable variceal bleeding, ascites, and hepatic hydrothorax. Clin Liver Dis 2006;10:583–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology 2005;41:386–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiftman ML, et al. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology 1994;20:46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rössle M, Haag K, Ochs A, et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 1994;330:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jalan R, Elton RA, Redhead DN, et al. Analysis of prognostic variables in the prediction of mortality, shunt failure, variceal rebleeding and encephalopathy following the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol 1995;23:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia N Jr, Sanyal AJ. Portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klempnauer J, Schrem H. Review: surgical shunts and encephalopathy. Metabolic Brain Dis 2001;16:21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]