Abstract

Soft structures in nature such as protein assemblies can organize reversibly into functional and often hierarchical architectures through noncovalent interactions. Molecularly encoding this dynamic capability in synthetic materials has remained an elusive goal. We report on hydrogels of peptide-DNA conjugates and peptides that organize into superstructures of intertwined filaments that disassemble upon the addition of molecules or changes in charge density. Experiments and simulations demonstrate that this response requires large scale spatial redistribution of molecules directed by strong noncovalent interactions among them. Simulations also suggest that the chemically reversible structures can only occur within a limited range of supramolecular cohesive energies. Storage moduli of the hydrogels change reversibly as superstructures form and disappear, as does the phenotype of neural cells in contact with these materials.

One Sentence Summary:

Large-scale redistribution of molecules in a supramolecular material generates chemically reversible superstructures.

Nature exploits self-assembly processes to promote formation of highly organized structures in a hierarchical manner (1, 2). These structures often reorganize dynamically as interactions among their constituents change, which impacts their functions (3–5). The design of weak and reversible interactions between molecules provides, in principle, a strategy to synthesize supramolecular architectures that can rearrange dynamically to impart changes in functionality. Despite recent advances in creating artificial hierarchical systems through self-assembly (6–10), approaches to manipulate these structures reversibly across length scales that reach macroscopic dimensions remain elusive. Collagen-mimetic peptides that form hierarchical structures have been designed in which triple helices of molecules interact to create fibrillar networks (11). However, these structures are neither tunable nor reversible. Another relevant recent example demonstrated dynamic changes in the unit cell of a microscopic colloidal crystal, in which gold nanoparticles were spatially reconfigured through chemically driven changes in surface organic ligands (12). Synthetic bundled fibrous networks with the dimensional tunability and dynamic reversibility of collagen would greatly enhance our ability to design functional soft matter.

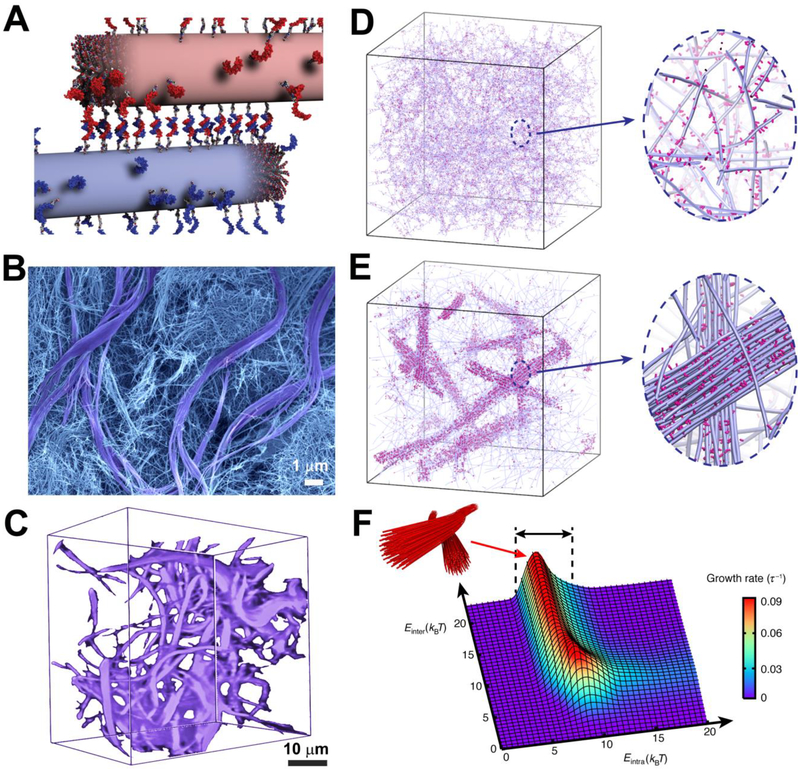

We report on fibrous supramolecular networks that form reversible superstructures controlled externally by the addition of soluble molecules. The system consists of nanofibers formed by co-assembly of alkylated peptides (monomer 1) with a similar monomer containing a covalently linked oligonucleotide terminal segment (monomer 2, see fig. S1). Mixing 1 with 2 in molar concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 10% led to the formation of fibers with a stochastic distribution of monomers along its length (see fig. S2). The original objective of this work was to create hydrogels in which small amounts of complementary oligonucleotides in separate fibers would lead to reversible cross-linking through Watson-Crick base pairing (Fig. 1A). When we mixed an aqueous solution containing fibers with complementary oligonucleotides (1/2 and 1/2’, Tables S1–S2), we observed the expected formation of a gel which could be liquefied by adding a soluble single-stranded DNA that breaks the cross-links via the well-known toehold-mediated strand displacement (13), see fig. S3. However, we were surprised to find by scanning electron microscopy a superstructure in which large micrometer-sized bundles of fibers segregated within a network of individual fibers (Fig. 1B, fig. S4). Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) also confirmed the formation of higher-order structures (fig. S5).

Figure 1. Dynamics in DNA-peptide amphiphiles drives the formation of hierarchical structures.

(A) Illustration of peptide amphiphile fibers cross-linked by DNA hybridization; fibers are shown in their initial state prior to monomer exchange. (B) SEM micrograph of the hydrogel formed upon DNA cross-linking showing two populations within the gel, consisting of twisted bundles (diameter ~1–3 μm) and single fibers (diameters between 10 and 15 nm). (C) Confocal reconstruction image of a section of the gel containing DNA monomers modified with the fluorescent dye Cy3. Bundles are shown in purple. (D) Simulation snapshots showing a homogeneous hydrogel when molecular exchange of DNA monomers between PA fibers is prohibited. Magnified view shows individual fibers (blue) with a stochastic distribution of DNA monomers (pink) along the fibers. (E) Simulation snapshots showing the emergence of bundles of fibers when molecular exchange is allowed. Magnified view shows bundle of fibers (blue) enriched with DNA (pink) in a matrix of individual fibers depleted of DNA monomers. (F) Bundle growth rate as a function of intra- and inter-fiber energies (Eintra, Einter). Bundles form within the energy range 5 kBT < Eintra < 10 kBT (black arrows).

To investigate possible differences in composition between the two apparent phases, we labeled oligonucleotides with a fluorescent dye (Cy3) to probe their distribution in the hydrogel. Confocal optical microscopy revealed that most of the DNA-containing monomers concentrated within the bundled regions (Fig. 1C). We first hypothesized that the system contained supramolecular polymers differing in content of DNA-bearing monomers, which in turn spatially segregated to create the bundled regions. However, we gelled solutions containing fibers with either monomer 2 or monomer 2’ by adding calcium chloride (electrostatic cross-linking) and did not find any domains with concentrated fluorescence characteristic of the bundled regions (fig. S6).

We then considered whether the formation of bundled regions involved large scale spatial redistribution of monomers within and among the fibers. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy revealed such dynamic exchange of monomers in supramolecular copolymers (14). To confirm that DNA hybridization among neighboring fibers was involved in the formation of the bundles, we mixed aqueous solutions of fibers containing non-complementary oligonucleotides, which did not yield bundled structures, (fig. S7A).

In order to establish that large-scale redistribution of monomers can give rise to bundle formation in a network of fibers, we carried out coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations using a model that accounts for the hybridization of complementary DNA segments (fig. S8 and Tables S3–4). In the simulation, each fiber is a chain of overlapping spheres that represent peptide amphiphile (PA) monomers, and some of the monomers are randomly grafted with DNA side chains. Complementary side chains can hybridize by forming reversible bonds while dynamic exchange of molecules among fibers is either disabled or permitted by fixing monomers within the fibers or allowing them to be mobile. A detailed description of the model and the simulation procedure is provided in the supporting information; snapshots are depicted in Fig. 1D and E, showing that dynamic molecular exchange among the supramolecular polymers is essential for the formation of DNA-rich bundles. Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments on mixtures of assemblies containing complementary DNA strands and labeled either with a donor or an acceptor moiety confirmed that monomers from the two separate fiber populations exchange and hybridize (fig. S9).

The simulations also provide important insights into the mechanism and kinetics of bundle formation. From a kinetic point of view, a hybridization event between fibers is likely to facilitate additional cross-linking locally of other DNA segments in neighboring locations. Furthermore, hybridized monomers have a lower tendency to escape to other fibers, measured in the simulations as a “trapping time” (fig. S10A). Likewise, the diffusivity of DNA monomers decreases significantly once they are recruited into the incipient bundles of the superstructure (fig. S10B). We infer that such mechanisms should lead to the growth of stable bundled regions. In experiments utilizing monomers labeled with the cyanine dye Cy3, we followed the kinetics of bundle formation and found that micron scale bundles formed within ten minutes (fig. S9A–B).

The simulations also showed that bundle growth rate (fig. S11) is sensitively controlled by the relative strength of molecular attraction among monomers within the fiber versus the energy associated with hybridization. Molecular attraction within the fibers is controlled by the energy associated with β-sheet formation and hydrophobic collapse of aliphatic segments in PA molecules (Eintra), whereas interaction between fibers is mediated by hybridization energy (Einter). Interestingly, the simulation predicted that fiber bundles form through redistribution of monomers when Eintra lies within the remarkably narrow range of 5 to 10 kBT, where kBT, the product of the Boltzmann constant kB and temperature T, is the thermal energy (Fig. 1F). Thus, cohesion among molecules needs to be strong enough to create stable fibers but not too strong to prevent dynamic exchange. Within this range, the model also showed that interfiber cross-linking requires a threshold energy to create bundled regions (Einter > 5kBT, fig. S12A). Below this threshold, the DNA monomers are predicted to distribute randomly along fibers resulting in a homogeneous disorganized structure (fig. S12B). By explicit estimation of the free-energy differences (Discussion S1), we confirmed that the molecular design of monomers 2 and 2’ indeed fell in the predicted regime for bundle formation. When dynamic exchange is suppressed (Eintra > 10 kBT), very small bundles can still form, provided that cross-links can break and rehybridize (fig. S12C). As redistribution of monomers does not occur, the growth rate is naturally limited by the low density of DNA monomers in the fibers. Additional experiments varying Eintra and Einter using different molecules supported our computational predictions and demonstrated the experimental tunability of the system investigated (figs. S13-S18).

We also explored both experimentally and through simulations the effect of molar concentration of DNA monomers on bundle formation (shown in fig. S7B–D, fig. S19). When DNA densities were too low, few fibers were cross-linked and the resulting monomer redistribution was not sufficient to support appreciable bundling. As the density increased, the clustering of DNA-containing monomers drove formation of larger bundles. Interestingly, above a given DNA concentration, the system “froze” kinetically into a three-dimensional (3D) gel without any bundled structures.

Having obtained evidence that the superstructures form when the systems contain low amounts of DNA-containing monomers, we were interested in investigating supramolecular assemblies in which all of the molecules are functionalized with complementary oligonucleotides. These systems would experimentally mimic the final DNA-rich superstructures created dynamically in the hydrogels. We followed the time evolution of these systems using electron microscopy and discovered that both DNA-containing monomers in pure form self-assembled into spherical micelles (fig. S20A and B). In our view, this result is not surprising given the large size and charge of the DNA segments. However, when 2 and 2’ were mixed and annealed, the spherical micelles metamorphosed into large twisted bundles of fibers (fig. S20C and D). These structures resembled the bundles observed in the hydrogels formed by co-assembled fibers in which DNA was only present in a small percentage of the monomers. This result implies that the drastic shape transformation from micelles to filaments was driven by DNA hybridization.

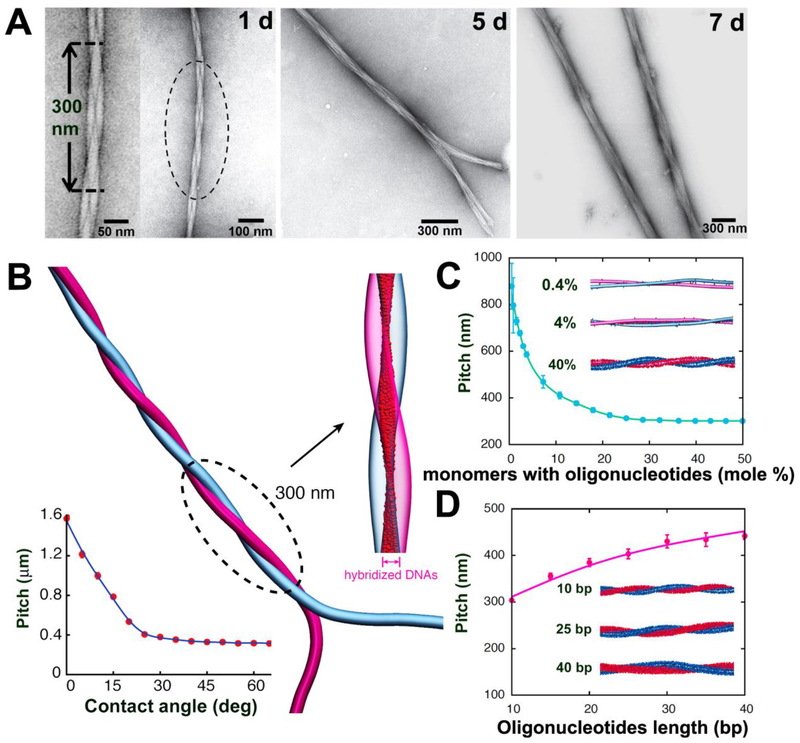

We then considered what would be the role of charge in the formation of such structures and designed monomers 3 and 3’ (Tables S1–S2) which contained complementary shorter DNA sequences that would experience weaker electrostatic forces. In these systems, we observed the formation of similar filamentous structures starting from spherical aggregates (fig. S21). In order to reduce electrostatic interactions further, we synthesized monomer 4 lacking the charges associated with nucleotides by replacing DNA with a peptide nucleic acid (PNA) sequence (Table S1, fig. S1), while keeping hybridization energy constant as confirmed by the melting temperature (Table S2). Interestingly, monomer 4 self-assembled into filaments (fig. S22), which indicates that charge density is an important factor in the formation of spherical aggregates. We then combined monomer 4 with a complementary DNA-containing monomer 4’. Much to our surprise, within 24 hours after mixing 4 and 4’ we observed formation of pairs of intertwining fibers with a regular pitch (Fig. 2A). As solutions were allowed to age further (5 and 7 days), we discovered further growth of twisted structures containing many fibers. These results suggest that the pairs formed at early time points contained non-hybridized oligonucleotide segments that created attachment points that then allowed further growth of the intertwined bundles.

Figure 2. Programming the growth of intertwined bundles of fibers.

(A) TEM images after mixing complementary DNA- and PNA-terminated peptide amphiphiles show the time-dependent evolution of twisted bundles over 24 hours, 5 days, and 7 days. (B) Simulation snapshot of two intertwined complementary fibers. The intertwining pitch saturates for most initial contact angles (bottom left). Hybridized DNA-PNA pairs between the two fibers (magnified view) form a twisted ribbon pattern. (C) Dependence of the pitch on the fraction of monomers with oligonucleotides. Simulation snapshots shown for systems with 0.4%, 4%, and 40% oligonucleotides-modified monomers. (D) Dependence of the pitch on the oligonucleotides length. Simulation snapshots shown for duplexes with 10, 25, and 40 DNA-PNA base pairs (bp).

To investigate the mechanism of intertwining, we simulated the interaction between complementary PNA and DNA filaments meeting at an arbitrary angle (Fig. 2B). The simulation showed that oligonucleotides hybridize first at the contact point, rapidly followed by further hybridization events as the fibers bend around each other to create an intertwined pair (movie S1). Because the intertwined state requires bending of the fibers (~1 kBT/nm), we hypothesized that the observed structure is thermodynamically less favorable than hybridization among two parallel fibers. However, to achieve parallel arrangement the intertwined structure faces an enormous energy barrier (> 10 kBT/nm) involving the breaking (and subsequent reforming) of hybridized oligonucleotides. This was confirmed by a free-energy analysis (fig. S23), and the observation that the twist state of two complementary fibers was determined by their initial contact angle (fig. S24). When deformation of the soft fibers was taken into account, the degree of hybridization increased (thereby raising the free-energy barrier), but parallel alignment remained favorable (fig. S25). Thus, we concluded that the observed intertwined structure is likely a kinetically trapped state. Future atomistic simulations may reveal that the intertwined architecture can be driven by the nature of intermolecular packing within the supramolecular polymer. The simulation also showed that intertwined pairs display a relatively uniform pitch of approximately 300 nm, consistent with our experimental observations. In fact, the pitch saturated at a constant value for most initial contact angles between fibers (> 25°, Fig. 2B) and high enough DNA densities (> 30%, Fig. 2C). However, the saturated pitch can be controlled by varying DNA length (Fig. 2D) as well as fiber stiffness (fig. S26) or oligonucleotide type (DNA or PNA, fig. S27).

The work described above in solutions containing complementary filaments provided us with mechanistic insight in the origin of bundle formation in hydrogels. The superstructure observed in the hydrogels containing fiber bundles can be viewed as a hierarchical structure with multiple levels of molecular organization. The first level of structure involves the interactions leading to filament formation (hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic collapse), followed by intertwining of fibers through DNA hybridization as a second level of structure. At even larger length scales in the hierarchical structure, bundle formation occurs via further hybridization among multiple intertwined fiber pairs, which then twist collectively. This description of the hierarchical structure is consistent with the large bundles dispersed in a matrix of DNA-depleted PA nanofibers demonstrated in Fig. 1B.

Given the possibility of melting interfiber DNA duplexes or breaking them using a competitive single-stranded oligonucleotide, we proceeded to investigate the reversibility of the hierarchical structure. First, we tested the effect of temperature and found that bundle-containing hydrogels could be liquefied at 95 °C. We then rapidly fixed the structure at elevated temperature by electrostatic gelation with calcium chloride and analyzed its structure by SEM (fig. S28). In samples treated this way, large bundles completely disappeared and only a network of individual fibers was visible (fig. S28B). In contrast, when the liquefied hydrogel was cooled slowly and imaged by SEM, superstructures reformed (fig. S28A). We infer that monomers once again redistributed in space, hybridized, and recreated the bundles. To further probe the thermal melting of bundles we performed SAXS experiments, which indicated that at 95 °C the fiber morphology persisted but the hierarchical bundling did not (fig. S29).

We also investigated the use of a toehold-mediated strand-displacement mechanism to destroy interfiber DNA duplexes. Monomers 2 and 2’ are designed to have an overhang sequence that is not complementary. Thus, adding an “invader” oligonucleotide that is fully complementary to monomer 2 should reverse inter-fiber hybridization events. After simply adding a drop of solution containing the invader molecules to the hydrogel, we observed the complete disappearance of the bundled structures (fig. S28D). The invader strand also contained a short overhang sequence which, upon addition of an anti-invader (fully complementary to the invader strand) allowed the hierarchical structures to reform (fig. S28C). The observed hierarchical structures appear to be chemically reversible by adding molecules or through changes in temperature. By adjusting the stoichiometry of invader oligonucleotides, we could form intermediate structures with small rather than large fiber bundles (fig. S30). Interestingly, the reversible transformation from bundled structures to individual fiber networks also led to reversible changes in the bulk mechanical properties of the hydrogels (see fig. S30). Hydrogels with superstructures had bulk storage moduli which were 15 times greater than those containing individual fiber networks. Furthermore, atomic force microscopy (AFM) nano-indentation studies confirmed that the bundled fibers were on average about 6-fold stiffer than individual fibers (fig. S31).

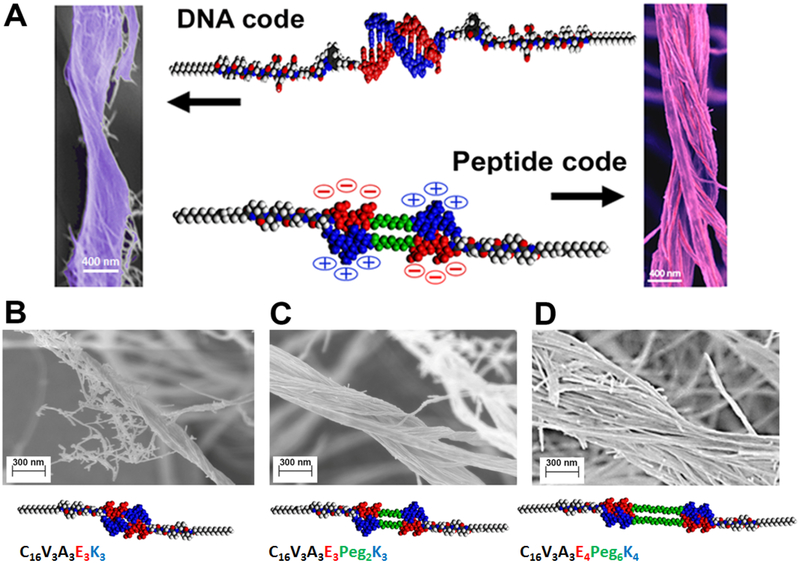

The coarse-grained rather than atomistic nature of our simulations suggested that the observed phenomena should not be limited to oligonucleotides and could be encoded in other systems without the use of DNA chemistry. For this purpose, we designed various peptide amphiphile sequences (5–7) each containing at their termini two oppositely charged peptide domains (Fig. 3, Table S1, fig. S32). We reasoned that electrostatic interdigitation of such “sticky ends” would mimic DNA duplex formation (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, co-assembly of these monomers with 1 yielded bundles of intertwined fibers similar to those in DNA-containing systems (Fig. 3B–D). Longer sequences of both charged residues and spacers resulted in greater bundle dimensions (Fig. 3B–D). When pH was either raised or lowered by adding NaOH or HCl, the bundles disappeared owing to the lack of electrostatic complementarity (fig. S33–35). Interestingly, simply mixing two different fibers bearing oppositely charged peptide domains did not result in bundle formation (fig. S36). This difference most likely arose because the fibers were kinetically trapped by electrostatic forces in a 3D gel. Alternatively, monomer exchange could reduce the thermodynamic driving force for bundling by mixing oppositely charged monomers on individual fibers.

Figure 3. Programming hierarchical structures with a peptide code.

(A) Molecular graphics representation of the complementary interactions between the DNA (top) and DNA-mimetic peptide amphiphiles (bottom), and the corresponding morphologies of bundled fibers observed in both systems by scanning electron microscopy. (B-D) Scanning electron micrographs of bundled and twisted fiber morphologies of varying diameters: (B) 140.5 ± 15 nm; (C) 332 ± 37 nm, and (D) 905 ± 190 nm, and the corresponding dimer molecular graphics and chemical sequences of the DNA-mimetic peptide amphiphiles that form the superstructures (EG refers to ethylene oxide and C16 is the number of carbons in the aliphatic terminus of the amphiphiles). Quantification of bundle diameters utilized a minimum of 15 randomly selected images (taken from three independent batches) for each system.

The system investigated here has structural features that are biomimetic of mammalian extracellular matrices (ECMs), a physical space that is known to be highly dynamic undergoing constant remodeling (15, 16). In natural ECMs, the networks of fibers vary widely in their organization and stiffness depending on the tissue (17). Often, these features are controlled by the extent of bundling of fibers. Because our experimental ECM mimic effectively remodels reversibly upon addition of a water-soluble and biocompatible molecule, we chose to investigate how dynamic organization of fibers within a hydrogel network affects cells in culture. We selected astroglial cells from the central nervous system (CNS) for these experiments, since they are subjected to a changing matrix environment following injury to the brain or spinal cord, yet much remains to be learned about how these changes affect their behavior. In this injury environment, astrocytes become reactive, undergoing drastic morphological changes and up-regulating glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin (18, 19), a process known as astrogliosis. The glial scar following injury to the CNS is spatiotemporally dynamic and contains a variety of macromolecules, including collagens, laminins, fibronectin, and proteoglycans, among others. Interestingly, the glial scar contains increased concentrations of fibrillar collagen type I, an extracellular matrix component not usually found in normal brain, which is composed of non-fibrillar collagen IV and glycosaminoglycans (20, 21).

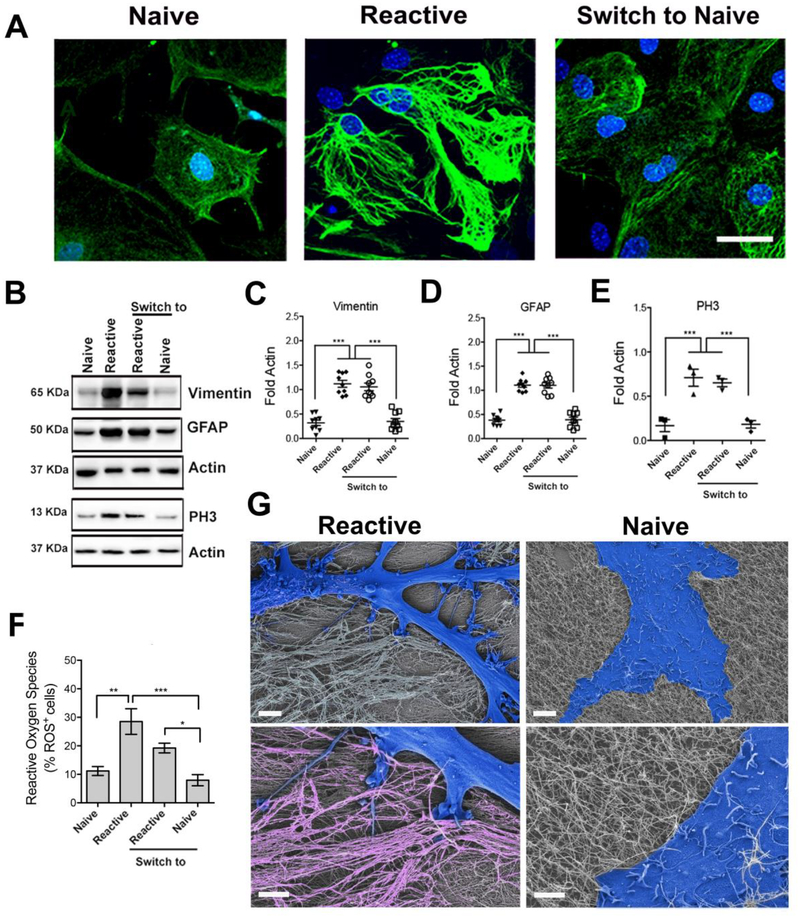

Because our system can mimic aspects of the morphological changes in the brain microenvironment, we used it as a culture substrate for cortical astrocytes isolated from postnatal mice. We tested the two states of the system, one with the superstructures consisting of bundled fibers (BF) and the other containing only individual fibers (IF) and switched from one to the other by adding the invader strand. Fig. 4A shows confocal micrographs of the cells labeled for GFAP and the nuclear stain DAPI after 10 days in culture. To our surprise, astrocytes cultured on BF hydrogels developed a reactive morphology and up-regulation of GFAP and vimentin (see western blot data in Fig. 4B–D), whereas those cultured on IF substrates had the naïve morphology observed under control conditions (glass) and lacked overexpression of both proteins. As a positive control, we added the molecule dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (dAMPc), well known to induce the reactive phenotype of astrocytes (22, 23). The data show that the resulting phenotype was similar to the one achieved on BF substrates, fig. S37. In addition, cells with the reactive phenotype were observed to up-regulate phospho-histone 3 (PH3), a marker of cell proliferation, see Fig. 4B–E. Proliferation was also demonstrated through staining with 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) (fig. S38), which is only incorporated into actively dividing cells. Further confirmation of reactive phenotype on BF substrates is provided, as expected, by an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), see Fig. 4F, fig. S39 (24, 25).

Figure 4. Modulating the phenotype of astrocytes on reversible hierarchical ECM mimetic.

(A) Confocal microscopy images of astrocytes plated on individual fibers (left), on bundled fibers (center), and after switching from bundles to individual fibers (right). Staining for GFAP (green) and cell nuclei (DAPI, blue) reveals cells with naive morphology on substrates of individual fibers and reactive morphology on substrates of bundled fibers. Scale bar: 50 μm, pertaining to all images. (B) Western blot analysis of protein expression (related to cytoskeleton and cell proliferation) in astrocytes on indicated substrates. (C-E) Relative expression of proteins derived from western blots in B. All values were normalized to Actin expression; three experiments were analyzed. (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001, LSD test). (F) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) quantification on the different substrates relative to cell number. (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001). (G) SEM micrographs of a reactive cell on bundled fibers and a naïve cell on individual fibers. Cells are falsely colored in blue. The magnified view (lower images) shows the cell-substrate interaction. Bundles are falsely colored in pink. Scale bars: 5 μm (upper images), 2 μm (lower images).

We then considered that changes in phenotype were linked to differences in mechanical properties between BF and IF substrates. However, cells exhibited the naïve phenotype when cultured on non-DNA containing hydrogels formed by self-assembly of monomer 1, which has a similar bulk modulus as the BF structure (fig. S40). Although these hydrogels had similar bulk moduli, stiffness could be a factor in the phenotypic change observed since AFM revealed that the superstructures were locally stiffer than individual fibers (fig. S31). However, stiffness cannot be the sole factor in the observed behavior since cells cultured on glass, obviously a very stiff substrate, also exhibited the naïve phenotype. Moreover, glial scars where the reactive phenotype of astrocytes is observed are actually softer rather than stiffer relative to the normal CNS environment (26). Our results therefore suggest that the structural organization of the newly formed extracellular matrix post-injury elicits astrocyte activation, and also that this phenomenon is reversible if the matrix environment reverts back to the pre-injury structure.

Having established the two distinct cell phenotypes on BF and IF substrates, we tested the response of the cells to the chemical reversibility of the artificial matrix from one state to the other by addition of the invader strand. Cells were cultured for 5 days on BF and IF substrates. At the end of this period, we added solutions of the invader and anti-invader strands to morphologically remodel the matrix. Interestingly, 5 days later, cells had switched from reactive to naïve phenotype when the invader strand was added to BF substrates, and from naïve to reactive when the anti-invader strand was added to IF scaffolds. As indicated in Fig. 4A–F, these changes in phenotype driven by dynamic changes of the substrate were accompanied by variation in protein expression and ROS. Fig. 4G shows SEM images revealing the morphological differences between reactive and naïve astrocytes on bundled “terrain” vs. single-fiber matrices. Moreover, in the case of BF substrates, cells appeared to interact closely with the bundles. Although astrogliosis was thought to be unidirectional and irreversible, glial cells transplanted from an injured spinal cord to an uninjured one (known to be stiffer than the injured one) reverted from reactive to naïve phenotype (20), suggesting that architectural cues and not matrix stiffness can reversibly control astrogliosis. Future therapeutic strategies that “de-fibrillate” glial scars could be explored to reverse neural pathologies through astrocytic fate decisions.

Our work has demonstrated that reversible superstructures can be formed in supramolecular materials when their large-scale dynamics are directed by the formation of strong noncovalent bonds that can be externally disrupted. Mechanistic insights for this phenomenon were obtained using a computational model that also identified the molecular parameters that enable the bonding-directed spatial redistribution of monomers to form and disassemble the superstructures. Our initial observations utilized DNA hybridization as the strong interaction in the experimental system, but we showed that the principles learned can be applied to other strongly interacting chemical structures such as charged peptides. The dynamic supramolecular systems enabled us to discover how changes in architectural features in fibrous hydrogel networks can modulate important phenotypic transformations in astrocytes linked to brain and spinal cord injury as well as neurological diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors are grateful to Mark Karver of the Peptide Synthesis Core Facility of the Simpson Querrey Institute at Northwestern University for his assistance and key insights into the synthesis and purification of the peptide amphiphiles. We thank Mark Seniw for the preparation of graphic illustrations shown in the figures. We thank Logan Kyle Frederick for his assistance with the analysis of the time-lapse video of bundle formation. J.A.L. gratefully acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1324585. Z.A. received postdoctoral support from the Beatriu de Pinós Fellowship 2014 BP-A 00007 (Agència de Gestió d’Ajust Universitaris i de Recerca, AGAUR) and the PVA Grant # PVA17_RF_0008 from the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA) Research Foundation.

Funding: The experimental work was primarily supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award # DE-FG02–00ER45810. Additional support on the synthesis and characterization of peptide-DNA conjugates was provided by Center for Bio-Inspired Energy Sciences (CBES), an Energy Frontiers Research Center (EFRC) funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under award number DE-SC0000989. All biological experiments reported were supported by a Catalyst Award from the Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine (CRN) at the Simpson Querrey Institute. The modeling work was supported by National Science Foundation through award No. DMR-1610796 and the National Institutes of Health through grant 1R01 EB018358-01A1. The U.S. Army Research Office, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, and Northwestern University provided funding to develop the Peptide Synthesis Core Facility (peptide synthesis) and the Analytical BioNanoTechnology Core Facility (biological and chemical analysis) that were used for this work, both of the Simpson Querrey Institute at Northwestern University, and ongoing support is being received from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF NNCI-1542205). This work also made use of the EPIC facility of Northwestern NUANCE Center at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF NNCI-1542205); the MRSEC program (NSF DMR-1121262) at the Materials Research Center; the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN); the Keck Foundation; and the State of Illinois, through the IIN. Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Molecular Imaging generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

Data and materials availability: All (other) data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References:

- 1.Whitesides GM, Grzybowski B, Self-assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418–2421 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nature biotechnology 21, 1171–1178 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needleman D, Dogic Z, Active matter at the interface between materials science and cell biology. Nature Reviews Materials 2, 17048 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridley AJ, Hall A, The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell 70, 389–399 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dos Remedios C et al. , Actin binding proteins: regulation of cytoskeletal microfilaments. Physiological reviews 83, 433–473 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu H, Hudson ZM, Winnik MA, Manners I, Multidimensional hierarchical self-assembly of amphiphilic cylindrical block comicelles. Science 347, 1329–1332 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capito RM, Azevedo HS, Velichko YS, Mata A, Stupp SI, Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes. Science 319, 1812–1816 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggeli A et al. , Hierarchical self-assembly of chiral rod-like molecules as a model for peptide β-sheet tapes, ribbons, fibrils, and fibers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 11857–11862 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S et al. , A self-assembly pathway to aligned monodomain gels. Nature materials 9, 594–601 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar M, Ing NL, Narang V, Wijerathne N, Hochbaum AI, Ulijn RV, Amino Acid-Encoded Biocatalytic Self-Assembly Enables the Formation of Transient Conducting Nanostructures, Nature chemistry, 10, 696–703 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Leary LE, Fallas JA, Bakota EL, Kang MK, Hartgerink JD, Multi-hierarchical self-assembly of a collagen mimetic peptide from triple helix to nanofibre and hydrogel. Nature chemistry 3, 821–828 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Macfarlane RJ, Jones MR, Mirkin CA, Transmutable nanoparticles with reconfigurable surface ligands. Science 351, 579–582 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E, Enzyme-free nucleic acid logic circuits. Science 314, 1585–1588 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Da Silva RM et al. , Super-resolution microscopy reveals structural diversity in molecular exchange among peptide amphiphile nanofibres. Nature communications 7, 11561 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daley WP, Peters SB, Larsen M, Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. Journal of cell science 121, 255–264 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z, Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 15, 786–801 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muiznieks LD, Keeley FW, molecular assembly and mechaical properties of the extracellular matrix: A fibrous protein perspective, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1832, 866–875 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun D, Jakobs TC, Structural remodeling of astrocytes in the injured CNS. The Neuroscientist 18, 567–588 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liddelow SA, Barres BA, Reactive astrocytes: Production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity 46, 957–967 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pogoda K, Janmey PA, Glial Tissue Mechanics and Mechanosensing by Glial Cells, Front Cell Neurosci 12, 25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara M et al. , Interaction of reactive astrocytes with type I collagen induces astrocytic scar formation through the integrin-N-cadherin pathway after spinal cord injury. Nature medicine 23, 818–828 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedoroff S, McAuley W, Hokle J, Devon R, Astrocyte cell lineage. V. Similarity of astrocytes that form in the presence of dBcAMP in cultures to reactive astrocytes in vivo. Journal of neuroscience research 12, 15–27 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu VW, Schwartz JP, Cell culture models for reactive gliosis: new perspectives. Journal of neuroscience research 51, 675–681 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robel S, Berninger B, Götz M, The stem cell potential of glia: lessons from reactive gliosis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 12, 88–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheng WS, Hu S, Feng A, Rock RB, Reactive oxygen species from human astrocytes induced functional impairment and oxidative damage. Neurochemical research 38, 2148–2159 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moeendarbary E, Weber IP, Sheridan GK, Koser DE, Soleman S, Haenzi B, et al. The soft mechanical signature of glial scars in the central nervous system. Nature Communications 8, 14787 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarez Z, Mateos-Timoneda MA, Hyrossova P, Castano O, Planell JA, Perales JC, et al. The effect of the composition of PLA films and lactate release on glial and neuronal maturation and the maintenance of the neuronal progenitor niche. Biomaterials 34, 2221–2233 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattotti M, Alvarez Z, Ortega JA, Planell JA, Engel E, Alcantara S. Inducing functional radial glia-like progenitors from cortical astrocyte cultures using micropatterned PMMA. Biomaterials 33, 1759–1770 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee OS, Stupp SI, Schatz GC, Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Peptide Amphiphile Self-Assembly into Cylindrical Nanofibers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 133, 3677–3683 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li TING, Sknepnek R, Olvera M de la Cruz, Thermally Active Hybridization Drives the Crystallization of DNA-Functionalized Nanoparticles. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 8535–8541 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kibbe WA, OligoCalc: an online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucleic Acids Research 35, W43–46 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee OS, Cho V, Schatz GC, Modeling the Self-Assembly of Peptide Amphiphiles into Fibers Using Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics. Nano Letters 12, 4907–4913 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monticelli L et al. , The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: Extension to proteins. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 4, 819–834 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH, The MARTINI force field: Coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 111, 7812–7824 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.