Abstract

Background

Alcohol use in young people is a risk factor for a range of short‐ and long‐term harms and is a cause of concern for health services, policy‐makers, youth workers, teachers, and parents.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of universal, selective, and indicated family‐based prevention programmes in preventing alcohol use or problem drinking in school‐aged children (up to 18 years of age).

Specifically, on these outcomes, the review aimed:

• to assess the effectiveness of universal family‐based prevention programmes for all children up to 18 years (‘universal interventions’);

• to assess the effectiveness of selective family‐based prevention programmes for children up to 18 years at elevated risk of alcohol use or problem drinking (‘selective interventions’); and

• to assess the effectiveness of indicated family‐based prevention programmes for children up to 18 years who are currently consuming alcohol, or who have initiated use or regular use (‘indicated interventions’).

Search methods

We identified relevant evidence from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (Ovid 1966 to June 2018), Embase (1988 to June 2018), Education Resource Information Center (ERIC; EBSCOhost; 1966 to June 2018), PsycINFO (Ovid 1806 to June 2018), and Google Scholar. We also searched clinical trial registers and handsearched references of topic‐related systematic reviews and the included studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs (C‐RCTs) involving the parents of school‐aged children who were part of the general population with no known risk factors (universal interventions), were at elevated risk of alcohol use or problem drinking (selective interventions), or were already consuming alcohol (indicated interventions). Psychosocial or educational interventions involving parents with or without involvement of children were compared with no intervention, or with alternate (e.g. child only) interventions, allowing experimental isolation of parent components.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 46 studies (39,822 participants), with 27 classified as universal, 12 as selective, and seven as indicated. We performed meta‐analyses according to outcome, including studies reporting on the prevalence, frequency, or volume of alcohol use. The overall quality of evidence was low or very low, and there was high, unexplained heterogeneity.

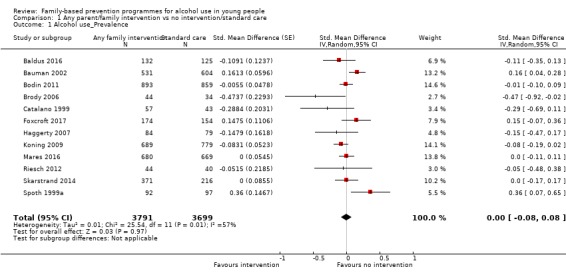

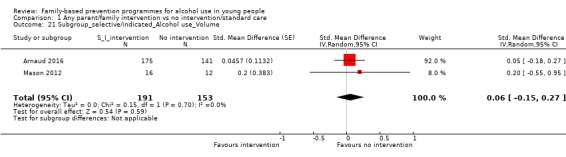

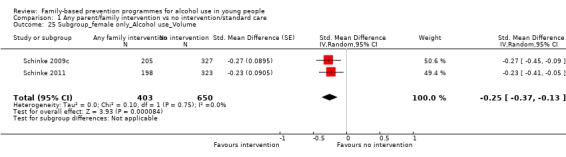

Upon comparing any family intervention to no intervention/standard care, we found no intervention effect on the prevalence (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.08 to 0.08; studies = 12; participants = 7490; I² = 57%; low‐quality evidence) or frequency (SMD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.21; studies = 8; participants = 1835; I² = 96%; very low‐quality evidence) of alcohol use in comparison with no intervention/standard care. The effect of any parent/family interventions on alcohol consumption volume compared with no intervention/standard care was very small (SMD ‐0.14, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.00; studies = 5; participants = 1825; I² = 42%; low‐quality evidence).

When comparing parent/family and adolescent interventions versus interventions with young people alone, we found no difference in alcohol use prevalence (SMD ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.91 to 0.14; studies = 4; participants = 5640; I² = 99%; very low‐quality evidence) or frequency (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 0.09; studies = 4; participants = 915; I² = 73%; very low‐quality evidence). For this comparison, no trials reporting on the volume of alcohol use could be pooled in meta‐analysis.

In general, the results remained consistent in separate subgroup analyses of universal, selective, and indicated interventions. No adverse effects were reported.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review indicate that there are no clear benefits of family‐based programmes for alcohol use among young people. Patterns differ slightly across outcomes, but overall, the variation, heterogeneity, and number of analyses performed preclude any conclusions about intervention effects. Additional independent studies are required to strengthen the evidence and clarify the marginal effects observed.

Plain language summary

Family‐based prevention of youth alcohol use

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effects of family‐ or parent‐based programmes as a way of preventing or reducing alcohol use in school‐aged children.

Background

Alcohol use puts young people at increased risk for a range of short‐ and long‐term harms and is a cause of concern for health services, policy‐makers, youth workers, teachers, and parents.

Search date

The evidence was current to June 2018.

Study characteristics

We found 46 randomised controlled trials (studies where participants were randomly allocated to one of two or more intervention or control groups) that compared family‐based interventions versus no intervention or an adolescent component alone. We included studies targeting general populations of parents and children (universal interventions), those targeting parents of children at increased risk of alcohol use (selective interventions), and studies targeting parents of children already using alcohol (indicated interventions). We were interested in studies following participants up to four years post intervention.

Most studies were conducted in the United States or in European countries (the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, and Germany). One study was conducted in India. Interventions were delivered in various settings including the child's school or family home and via the Internet or print material. Interventions varied in intensity, duration, and approach, but all targeted alcohol or other drug use by promoting positive parenting approaches or enhancing parent‐child relationships. The interventions focused on communication, family dynamics, rule‐setting, and risk management.

The total number of participants in the included studies was 39,822, and the young people targeted ranged from 5 to 17 years of age. Participant ethnicity was mixed, with 12 studies targeting ethnic minority groups specifically.

Key results

Overall, we found no evidence for the effectiveness of family‐based interventions on the prevalence, frequency, or volume of alcohol use among young people. Some analyses focusing on specific subgroups of studies (e.g. including only universal interventions, targeting ethnic minority groups) showed small intervention effects, but considering variation in results, variation between studies, and overall low quality of the evidence, we are uncertain whether these interventions have a positive effect on young people's alcohol consumption. Some studies reported positive intervention effects on secondary outcomes (parental supply of alcohol, family involvement, alcohol misuse, and alcohol dependence) but with small numbers; these studies could not be pooled, so the evidence is insufficient. No adverse effects were reported.

Quality of evidence

Overall, only very low‐ or low‐quality evidence shows the small effects found in this review. Many of the studies did not adequately describe how families/young people/parents were allocated to the study groups, or how they concealed the group allocation from participants and personnel. We downgraded the quality of evidence due to the heterogeneity (variability) between studies and imprecision (variation) in results. These problems with study quality could result in inflated estimates of intervention effects, so we cannot rule out the possibility that slight effects observed in this review may be overstated.

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Drug Abuse (NIDA), and Mental Health provided funding for over half (28/46) of the studies included in this review. Three studies provided no information about funding, and only 13 papers had a clear conflict of interest statement.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Alcohol use ranks among the top three risk factors for the global burden of disease, accounting for 5.5% of disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs) globally (Lim 2012). A causal relationship has been established between alcohol and more than 200 chronic and acute diseases, as well as intentional and unintentional injuries (Rehm 2010). Overall, in 2010, alcohol‐attributable injuries were responsible for 13.2% of all injury deaths and for 12.6% of all injury potential years of life lost (PYLL) (Rehm 2013). Young people contribute a high proportion of alcohol‐related injuries and mortality from alcohol‐attributable injury, with 11% of deaths among men aged 15 to 34 years, and 3.5% of deaths among women aged 15 to 34 years in the European Union, being alcohol‐related (Rehm 2012). In the European Union, road traffic accidents are the leading cause of death in children and young adults up to 29 years, and 33% of motor vehicle traffic injuries to males and 11% to females of all ages are due to alcohol (WHO 2012). Extensive evidence points to an association between early age of alcohol use initiation (and early intoxication) and an increased frequency of drinking, as well as increased risky drinking and alcohol‐related harms later in adolescence and during adulthood (e.g. Bonomo 2004; DeWit 2000; Jackson 2015; Kuntsche 2013; Livingston 2008; Waller 2018).

Experimentation with risky behaviours typically begins in adolescence, as part of a natural ‘coming of age’ process (Room 2004). A dramatic increase in the use of alcohol is seen after the age of 12, with rates gradually increasing throughout adolescence (Currie 2012). This pattern is common globally, with reports from 43 countries included in the Health Behaviour in School‐Aged Children Project (Currie 2012), reports from the European Survey Project on Alcohol and Drugs (ESPAD; Hibell 2012), and results of national surveys conducted in Australia ‐ White 2012 ‐ and the United States (US) ‐ Frieden 2014 ‐ demonstrating these patterns. Any level of alcohol use is potentially harmful for young people, with evidence of an effect upon the developing brain (Bava 2010), along with a subsequent increase in risk for alcohol use disorders (Waller 2018). Early sipping of alcohol has been associated with increased odds of consuming full drinks, getting drunk, and drinking heavily later in adolescence (Jackson 2015). Consumption of at least a standard drink of alcohol at or before age 13 has been associated with an increased risk of frequent binge drinking in late secondary school (Aiken 2018). Even a single occasion of alcohol intoxication can have serious short‐ and long‐term consequences (Courtney 2009; Quinn 2011). Internationally, guidelines for low‐risk alcohol consumption include recommendations for young people (in Australia under the age of 18 years, and in the US under the age of 21) not to drink at all (NHMRC 2009; USDHHS 2015).

Although the use of alcohol is common among young people, some groups can be identified as being at elevated risk of heavy use due to a range of social, peer, and family factors. Livingston and colleagues report that young people who have had their first drink by age 13 are almost twice as likely to engage in very high‐risk drinking when aged 16 to 24 (Livingston 2008). Parents who allow their children to consume alcohol in adult‐supervised settings in early adolescence are more likely to have children who experience harmful alcohol consequences in mid‐adolescence (McMorris 2011). Further, parents who themselves have heavy drinking occasions are more likely to have children who report heavy drinking occasions (Hingson 2014), and parental substance use and family history of alcoholism have been identified as predictors of adolescent substance use in longitudinal studies (Alati 2014; Chassin 1996; Cranford 2010; White 2000; Wills 2003). Evidence is mixed in relation to the association between socioeconomic disadvantage and risk of adolescent alcohol consumption (Hanson 2007). Some reports show drinking and drunkenness associated with lower levels of disadvantage or higher levels of household income (Reboussin 2010; Richter 2009). Other reports show higher levels of baseline problem drinking among low socioeconomic status communities (Caria 2011; Lowry 1996).

Description of the intervention

Despite the influence of peers and society during adolescence (Carter 2007; Patton 2004), parenting and home environment factors are important influencers of development (Steinberg 2001), as well as predictors of alcohol consumption and other substance use (Carter 2007; Simons‐Morton 2009; Turrisi 2010; Wang 2009). Maternal and paternal knowledge of their child’s friends and whereabouts is reported to act as a protective factor against substance use and to mediate the variability in substance use by grade and ethnic background (Wang 2009). This protective effect is suggested to act via an influence on peer group selection (Engels 2007; Wang 2009), the transmission of family attitudes and values (White 2010), and parental monitoring (knowledge of their child’s whereabouts) (Jimenez‐Iglesias 2013).

In 1994, the US Institutes of Medicine adopted a framework for the classification of mental health and substance use prevention interventions as universal, selective, or indicated/targeted (Mrazek 1994; Springer 2006). Universal prevention strategies address the entire population within a particular setting. Selective interventions are delivered to subgroups of individuals based on their membership in a group that has an elevated risk of developing problems. Indicated interventions address vulnerable individuals and help them in dealing and coping with their individual personality traits that make them more vulnerable to escalating drug use (EMCDDA 2015).

Although intervention programmes are usually classified as belonging to one of these three broad groups, the classification can be regarded as a continuum, with obvious overlap between groups. In the 2010 report "Fair Society, Healthy Lives", commissioned by the United Kingdom (UK) government to identify the most evidence‐based strategies for reducing health inequalities, a key recommendation was to extend the focus of preventive activities beyond the most disadvantaged, to encompass the full spectrum of the social gradient. It was stated that to "reduce the steepness of the social gradient in health, actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage" (Marmot 2010).

Applied to alcohol prevention efforts, this ‘proportionate universalism’ can be interpreted as the need to conduct universal prevention programmes, but to also include more targeted (selective and indicated) interventions for higher‐risk groups. Parenting skills are recognised as a key factor in the prevention of adolescent alcohol consumption and other substance use. The proportionate universalism approach maintains that all parents should be given opportunities for support and help to develop appropriate protective parenting skills, and that some parents who demonstrate a particular risk profile or who have particular needs (e.g. have vulnerable children) should be offered increasingly targeted (and increasingly costly) interventions (Heginbotham 2012; Marmot 2010). For this reason, this review is not limited to universal interventions, but will incorporate those classified as selective and indicated.

Classification of interventions in the present review is based on their target population, whether all parents (universal) or a select group based on characteristics of parents or their children (selective and indicated). In the context of family‐based interventions for alcohol use in young people, universal interventions target parents of all children given the inherent risk of alcohol use among all sectors of the population. These interventions will likely aim to delay the initiation of alcohol use, or to reduce the frequency or volume of use among children of participating parents. Selective interventions are those targeting parents whose children have an elevated risk of substance use due to social or family risk factors. Such risk factors include low socioeconomic status or family income, along with parental alcohol consumption, alcoholism, or other substance use. Similarly, these interventions will likely aim to delay initiation or reduce consumption. Indicated interventions are defined as those that target parents or families whose children are already identified as drinkers. These interventions will more likely aim to reduce levels of consumption or the frequency of binge drinking and/or to reduce alcohol‐related harms.

Parent‐ and family‐based programmes for the prevention of alcohol use are often appended to school curricula‐based interventions for young people, but may also be designed as stand‐alone programmes. Such programmes frequently focus on parent‐child communication and relationship building. Common elements across many programmes include focus on social competence skills, parental involvement with children, and self‐regulation, although the target population and the intensity and mode of delivery are highly varied.

How the intervention might work

The theoretical basis for family‐based interventions is that young people whose parents adopt appropriate parenting strategies are likely to develop positive social norms and to resist the negative external influences of peers and society. In this context, positive parenting strategies include rule‐setting, appropriate communication, monitoring, and conveying positive values and attitudes (Ryan 2010). Family‐ and parent‐based interventions for adolescent substance use operate indirectly, with the mechanism of effect working via parents rather than through a programme delivered directly to young people as the target population. As such, the developmental trajectory of particular behaviours, for example, alcohol use, is changed via improved family or parent socialisation practices (Foxcroft 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Previous Cochrane Reviews have separately covered universal family‐based programmes (Foxcroft 2011a), as well as school‐based and multi‐component interventions (Foxcroft 2011b; Foxcroft 2011c, respectively), for alcohol misuse among young people that incorporate family‐based interventions. The most recent of these reviews was completed with studies published up to July 2010. Since the time of that review, several trials have been published, reporting on other family‐based preventive programmes, and in many cases using innovative approaches including online delivery.

As well as updating the previous review (Foxcroft 2011a), the current review extends beyond universal interventions to include those classified as selective and indicated, in keeping with the concept of proportionate universalism.

Although parents and families are influential and provide a key target for intervention, family‐based programmes are often expensive to run and challenging from a recruitment and engagement perspective (Haggerty 2006). It is important to gather evidence of their effectiveness, and of the differential effectiveness of various components of these programmes, to inform policy and funding decisions.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of universal, selective, and indicated family‐based prevention programmes in preventing alcohol use or problem drinking in school‐aged children (up to 18 years of age).

Specifically, on these outcomes, the review aimed:

to assess the effectiveness of universal family‐based prevention programmes for all children up to 18 years (‘universal interventions’);

to assess the effectiveness of selective family‐based prevention programmes for children up to 18 years at elevated risk of alcohol use or problem drinking (‘selective interventions’); and

to assess the effectiveness of indicated family‐based prevention programmes for children up to 18 years who are currently consuming alcohol, or who have initiated use or regular use (‘indicated interventions’).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including cluster‐randomised trials (C‐RCTs).

Types of participants

Parents or guardians/carers of young people up to 18 years (of school age). For this review, we defined young people as children and adolescents and excluded those transitioning to college due to differences in context and parenting roles. We included parents of young people who have not previously consumed alcohol, currently consume alcohol, or have heavy or problematic alcohol use. Young people were also included as participants in some interventions and in the context of data collection.

Types of interventions

Any universal, selective, or indicated family‐based psychosocial or educational prevention intervention.

We defined universal prevention strategies as those addressing the entire population without selection of children based on characteristics that may increase their risk of alcohol use or problem drinking, for example, those offered to all parents of children attending a school.

We defined selective interventions as those delivered to a subgroup of children identified as having socio‐demographic or other characteristics that put them at an elevated risk of alcohol use or problem drinking, for example, those delivered to families in which there is a history of substance use or mental health problems among parents, to those living in communities of low socioeconomic status, or to those engaging in delinquent behaviour.

We defined indicated interventions as those targeting a subgroup of children who currently use alcohol or who may have alcohol‐related problems.

We included prevention programmes that focused on alcohol as well as other drugs wherever alcohol outcomes were presented separately. We defined psychosocial interventions as interventions that specifically aim to develop psychological and social attributes and skills in parents or young people (e.g. parental monitoring, behavioural norms, peer resistance), so that young people are less likely to use alcohol. We defined educational interventions as those that specifically aim to raise awareness amongst parents and/or carers of how to positively influence young people, or of the risks of alcohol consumption, so that young people are less likely to use alcohol.

The comparison consisted of any alternative prevention programme (e.g. school‐based, office‐based, multi‐component, other) where the parental component could be experimentally isolated (e.g. parent plus school compared to school only) or no programme.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Any direct self‐reported (by adolescents) measures of alcohol consumption or problem drinking. As an example, we considered the following outcomes to be relevant.

Alcohol use (yes/no).

Alcohol use (quantity, frequency).

'Binge' drinking (e.g. defined as drinking five or more drinks on any one occasion) (yes/no).

Incidence of drunkenness.

Outcome measures related to psychological perception/attitudes or awareness of alcohol risks were deemed to be indirect; therefore we did not consider them in this review.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes could be measured through self‐report (by adolescents or parents) or through police, juvenile justice, or medical records.

Age of alcohol initiation.

Age of drunkenness initiation.

Alcohol‐related problems or harms (e.g. drunk driving or any physical or social problem self‐reported by adolescents as an alcohol‐related consequence may be measured using a scale such as Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index or questions 7 to 10 of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)).

Parent‐reported or child‐reported alcohol‐related parenting behaviours (e.g. supply of alcohol, alcohol‐specific communication, alcohol‐specific rule‐setting).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases, without restrictions by language or publication status, in June 2018. The search strategy is based on that used by Foxcroft 2011a but with the removal of terms that were designed to limit the previous review to universal interventions. Thus these searches were conducted afresh from the earliest available records with no limits placed on publication date.

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group's Specialised Register of Trials.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2018 issue), in the Cochrane Library.

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1966 to 30 June 2018).

Embase (Embase.com) (1974 to 30 June 2018).

Education Resource Information Center (ERIC; EBSCOhost) (1966 to 30 June 2018)

PsycINFO (Ovid) (1806 to 30 June 2018).

Google Scholar (modified MEDLINE search to account for 260 character limit).

Project CORK (http://www.projectcork.org).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/).

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

The subject strategies for databases were modelled on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, these were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b; Higgins 2011). Search strategies for major databases are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of topic‐related systematic reviews and included studies to identify potentially relevant citations (Dusendury 2000; Gates 2006; Hale 2014; Kuntsche 2016; Lemstra 2010; MacArthur 2012; Petrie 2007 Smit 2008; Vermeulen‐Smit 2015; ). Unpublished reports, abstracts, dissertations, and brief and preliminary reports were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of independent reviewers (including CG, AW, LW, JT, TS, ES) completed broad screening of titles and abstracts of all identified records (screening level 1). Afterwards, the same pairs independently assessed full‐text reports of all potentially relevant records that passed the initial screen. We resolved differences in opinion arising at both screening levels through discussion and involvement of a third review author for resolution where required. Reasons for exclusion of full‐text articles were recorded and are reported in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors independently extracted relevant data using an a priori defined data extraction form (CG, AW, ES, TS), and one review author (AW) entered data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). We resolved differences in opinion arising during data extraction through discussion and involvement of a third review author for resolution where required. We extracted the following information: numbers and characteristics of participants, setting, types of experimental and control interventions, length of follow‐up, types of outcomes, outcome data (sample sizes, means, standard deviations, odds ratios, confidence intervals as available), country of origin, and methodological characteristics associated with the assessment of risk of bias (randomisation procedures, blinding, data collection procedures, attrition, outcome reporting, and analysis characteristics associated with clustered studies).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each study included in the review, two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias (CG, AW, TS, ES, MK). We performed the risk of bias assessment for RCTs in this review using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach addresses seven specific domains, namely, sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias; less than 20% loss of participants with no differential attrition between experiment groups was regarded as low risk), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other sources of bias (contamination bias). For C‐RCTs, we also assessed risk of recruitment bias, baseline imbalances, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and compatibility with individually randomised trials (herd effect). The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement related to the risk of bias for that entry, in terms of low, high, or unclear risk. To make these judgements, we used the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, as adapted to the addiction field. See Appendix 2 for details.

Grading of evidence

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome of each study using the GRADE system. The Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) developed a system for grading the quality of evidence (GRADE 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011), which takes into account issues related not only to internal validity (risk of bias) but also to external validity, such as directness, consistency, imprecision of results, and publication bias. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

In this review, we present the 'Summary of findings' tables based on type of intervention programme (universal, selective, indicated) and type of comparison (intervention vs intervention as well as comparative effectiveness trials). Summary tables cover those comparisons where sufficient studies were available to enable meta‐analytical pooling.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria in assigning grades of evidence.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Comparisons of RCTs begin with a 'high' rating and are downgraded based on serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality; important inconsistency (‐1); some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness; imprecise or sparse data (‐1); and high probability of reporting bias (‐1).

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated treatment effects using RevMan 2014 where possible.

Dichotomous outcome data

We analysed dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk ratio (RR) for each trial, with the uncertainty in each result expressed using 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous outcome data

We analysed continuous outcomes by calculating mean differences (MDs) if all studies used the same measurement scale, or standardised mean differences (SMDs) if studies used different measurement scales, each with 95% CIs. If data in small studies were skewed, we assessed the implications for outcomes on a case‐by‐case basis.

Unit of analysis issues

We ascertained additional validity threats regarding appropriate unit of analysis depending on whether randomisation was implemented at an individual or cluster level. We assessed cluster‐randomised trials in the review for unit of analysis error. For studies that did not adjust for clustering, we calculated design effects and effective sample sizes using available study data and reported intraclass correlations (ICCs). Where ICCs were not available, we used a mean ICC calculated from reported ICCs of included studies to calculate effective sample sizes before inclusion in meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011). We included studies with more than two trial arms in the meta‐analysis by selecting the most appropriate intervention and comparison (e.g. family‐based intervention vs no‐intervention control, with no data taken from a classroom‐based intervention arm). We included studies in two separate meta‐analyses if they included a family‐based intervention arm that could be compared separately with a no‐intervention or standard care arm and a family and adolescent intervention.

Dealing with missing data

Where important summary data or study level characteristics were missing, we attempted to contact the authors of those included studies. Where standard deviations were missing from continuous data, we scanned studies for any other statistics (CIs, standard errors, T values, P values, F values) that allowed for their calculation. Where available, we reported outcomes of trials reporting an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of heterogeneity involved inspecting each included study for variability in study populations (baseline characteristics), interventions (target/focus, mode of delivery), and outcome measures (tools, instruments, scales, and outcome definitions). We considered methodological heterogeneity by inspecting variability in study design and risk of bias. Where acceptable homogeneity was found within subgroups (based on age of children, type of intervention, or substance targeted), we conducted meta‐analysis for subgroups of studies. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi² test and its P value, by visually inspecting the forest plots, and by using the I² statistic. A P value of the test lower than 0.10 or an I² statistic of at least 50% indicated significant statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots (plots of the effect estimate from each study against the sample size or effect standard error) to indicate possible publication bias. We used tests for funnel plot asymmetry only when a minimum of 10 studies were included in the meta‐analysis, as fewer than 10 studies would render the power of the tests too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We calculated pooled standardised mean differences (to account for heterogeneity of outcome measures) for each comparison using a random‐effects model with a generic inverse variance weighting method (RevMan 2014). We calculated standardised mean differences for all outcome measures to maximise comparability, and we used the generic inverse variance method, which allows for inclusion of studies reporting data in a range of forms including both continuous and dichotomous outcomes along with those reporting odds ratios, risk ratios, or differences between means. We selected post‐intervention values over changes from baseline data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis, to reduce the risk of selective reporting and to maximise the number of studies that could be pooled.

We synthesised studies that provided suitable data for pooling in meta‐analysis grouped by outcome. Due to small numbers of studies in each comparison, we explored effects by type of prevention intervention (i.e. universal, selective, or indicated) in subgroup analyses. Depending on study numbers in each comparison, selective and indicated interventions may be grouped together to represent more targeted approaches in contrast to universal ones; these would be regarded as further along the scale of proportionate universalism (Marmot 2010). We grouped outcomes as measuring alcohol use prevalence (measures of the prevalence of any alcohol consumption or a specified threshold of consumption such as the prevalence of drinking at least once per month); frequency (measures of the number of occasions of use in a given period); or volume (measures of the number of drinks in a given period). When studies reported multiple alcohol outcomes in one of these categories, we selected the most conservative measure capturing small or infrequent levels of use (e.g. the frequency of any drinking was selected in preference to the frequency of drunkenness, if both were available). Studies could contribute to multiple meta‐analyses if they reported eligible outcomes in more than one category. From studies that reported multiple follow‐up points, we extracted data from the longest follow‐up period up to four years for inclusion in meta‐analyses.

We selected study estimates that adjusted for potential confounding variables for inclusion in meta‐analysis over estimates that did not adjust for potential confounding variables, when available. Similarly, we selected C‐RCT study estimates that were adjusted for clustering for inclusion in meta‐analyses over unadjusted estimates. For those C‐RCTs that did not adjust for clustering, we adjusted study estimates using a mean ICC from other included studies and the effective sample size used in meta‐analysis. We pooled separately studies that compared two or more alternative interventions, enabling experimental isolation of the parent intervention component.

In all instances where data could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis, we have provided a narrative summary of the trial findings according to the review objectives.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated the extent of heterogeneity through visual examination of forest plots and through use of the Chi² statistic, the P value, and the I² statistic. Where there was evidence of heterogeneity (I² statistic > 50%), we investigated the potential source of heterogeneity through subgroup analyses. Specifically, we conducted subgroup analyses based on the type of prevention intervention (universal, selective, indicated), the intensity of the intervention (considering duration and level of face‐to‐face involvement), the characteristics of participants (ethnicity and gender), and the length of follow‐up (less than 12 months, or between 12 months and 4 years).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis of the main review outcomes, removing trials judged to be at high risk of bias (graded as high on three or more 'Risk of bias' measures). For C‐RCTs, two or more ratings of high risk on any of the five cluster‐specific risk of bias domains contributed one high risk rating to the overall assessment.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies,Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

See the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The search strategy resulted in a total of 23,367 citations, and we identified a further 11 studies by checking the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews. After removal of duplicate records, 13,399 records remained. Screening of titles and abstracts revealed 184 studies for full‐text review and formal inclusion or exclusion. Of these, 46 papers met the inclusion criteria as primary studies (Arnaud 2016; Baldus 2016; Bauman 2002; Bodin 2011; Brody 2006; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Estrada 2017; Fang 2010; Fosco 2013; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Koning 2009; Liddle 2008; Linakis 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mares 2016; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; O'Donnell 2010; Perry 2003; Prado 2012; Reddy 2002; Riesch 2012; Schinke 2004; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Skarstrand 2014; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2015; Spirito 2017; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stanger 2017; Stevens 2002; Stormshak 2011; Valdez 2013; Werch 2008; Winters 2012; Wolchik 2002; Wu 2003; Wurdak 2017), and a further 31 as companion papers to included trials.

Included studies

A description of the included studies appears in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We included 46 studies with 39,822 participants (or families) randomised across the 46 included trials. Thirty‐one studies were RCTs, 25 of which compared an intervention group versus a no intervention control group or a 'usual care' group (Baldus 2016; Bauman 2002; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Estrada 2017; Fang 2010; Fosco 2013; Haggerty 2007; Linakis 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; O'Donnell 2010; Prado 2012; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Spirito 2017; Stanger 2017; Stormshak 2011; Valdez 2013; Wolchik 2002; Wurdak 2017), and six of which compared the effectiveness of two different family‐ or parent‐focused interventions (Liddle 2008; Schinke 2004; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2015; Werch 2008; Winters 2012). The other 15 included studies were C‐RCTs, 10 of which compared an intervention group versus a no intervention control group (Arnaud 2016; Bodin 2011; Brody 2006; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Koning 2009; Mares 2016; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a), and five of which were comparative effectiveness trials (Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002; Wu 2003). In total, we classified 12 studies as comparative effectiveness trials, usually with more than two trial arms, including a comparison of a family/parent intervention coupled with adolescent intervention components versus the adolescent components alone. In such studies, experimental isolation of the parent component for analysis purposes was possible (Koning 2009; Liddle 2008; Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2004; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2015; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002; Werch 2008; Winters 2012; Wu 2003).

Twenty‐seven of the included studies tested the impact of interventions classified as universal, targeting all children or families; 12 were selective, targeting groups at elevated risk; and seven were classified as indicated, targeting families where young people were already using alcohol. Of studies comparing universal interventions, 13 were C‐RCTs, with nine using schools as the unit of randomisation, one using county (Brody 2006), one using communities (Foxcroft 2017), one using classrooms (Furr‐Holden 2004), and one using paediatric clinics (Stevens 2002). Among selective and indicated interventions, only one study in each category was a C‐RCT, with the selective study randomising community centres (Wu 2003), and the indicated study randomising paediatric emergency departments (Arnaud 2016). The 14 universal RCTs randomised participants at the level of adolescent‐parent dyads (n = 7; Bauman 2002; Estrada 2017; Linakis 2013; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011), families (n = 4; Fosco 2013; Haggerty 2007; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; O'Donnell 2010), adolescents (n = 1; Werch 2008), communities (n = 1; Schinke 2004), or parents (n = 1; Wurdak 2017). The selective RCTs randomised individual families (n = 7; Catalano 1999; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Spirito 2015; Stormshak 2011; Wolchik 2002), adolescents (n = 2; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001), or dyads (n = 2; Baldus 2016; Fang 2010). The six indicated RCTs randomised at the level of the family (n = 3; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2017; Valdez 2013), or at the level of the adolescent (n = 3; Liddle 2008; Stanger 2017; Winters 2012).

Country

Twenty‐nine trials were undertaken in the United States; 16 studies examined universal interventions (Estrada 2017; Haggerty 2007; Linakis 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; O'Donnell 2010; Schinke 2004; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Werch 2008; Perry 2003; Riesch 2012; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002), 11 studies selective interventions (Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Fang 2010; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Spirito 2015; Stormshak 2011; Wolchik 2002;Wu 2003), and six studies targeted interventions (Liddle 2008; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2017; Stanger 2017; Valdez 2013; Winters 2012). Two trials were conducted in the Netherlands (both universal C‐RCTs; Koning 2009; Mares 2016), two in Sweden (both universal C‐RCTs; Bodin 2011; Skarstrand 2014), one in Poland (a universal C‐RCT; Foxcroft 2017), three in Germany (one universal RCT ‐ Wurdak 2017; one selective RCT ‐ Baldus 2016; and one indicated C‐RCT ‐ Arnaud 2016), and one in India (a universal C‐RCT ‐ Reddy 2002).

Participants

Ethnicity of participants was mixed. Twelve trials included exclusively or over‐represented specific ethnic groups. Four studies exclusively ‐ Wu 2003,Brody 2006 ‐ or predominantly ‐ Furr‐Holden 2004,Liddle 2008 ‐ involved African American participants. Three further studies included a close to 50:50 ratio of African American and Caucasian (or other) participants (Dembo 2001; Haggerty 2007; Riesch 2012). Four studies involved only Hispanic or Mexican American participants (Cordova 2012; Estrada 2017; Prado 2012; Valdez 2013), and one study involved only Asian American participants (Fang 2010). A further 12 studies involved participants from a mix of ethnic backgrounds: two mostly Caucasian and African American (Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Werch 2008); four mostly Causasian and Hispanic/Latino (Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2015); and six a mixture of all these groups (O'Donnell 2010; Schinke 2004; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Stormshak 2011). Twelve studies included a mix of ethnicities but predominantly Caucasian American (Bauman 2002; Catalano 1999; Linakis 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Perry 2003; Schinke 2009a; Spirito 2017; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stanger 2017; Winters 2012; Wolchik 2002). One study involved a broader range of ethnic groups including a minority of Native American and Pacific Islander participants (Fosco 2013). The remaining nine studies did not target particular ethnic groups nor report particular cohort breakdowns.

The age of children targeted through the interventions ranged from 5 to 17 years (average approximately 13 years). Furr‐Holden 2004 involved very young children, with an average age of 6.2 years, and Stanger 2017 involved the oldest cohort, with an average age of 16.1 years. In general, the average age of adolescent participants was higher in trials of selective (approximately 13 years) and indicated (approximately 15.5 years) trials than in trials of universal interventions (approximately 12 years). Six studies exclusively targeted girls, four of which provided universal interventions (O'Donnell 2010; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c), and two of which gave selective interventions (Fang 2010; Schinke 2011).

Recruitment and eligibility

Of the universal interventions, a majority recruited participants via schools (n = 17; Bodin 2011; Brody 2006; Estrada 2017; Fosco 2013; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Koning 2009; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mares 2016; O'Donnell 2010; Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Werch 2008). Five studies used community advertisements such as newspapers, flyers, and "craigslist" (Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Wurdak 2017); two recruited through community agencies such as after school care and social organisations (Foxcroft 2017; Schinke 2004), one through paediatric emergency departments (Linakis 2013), one through paediatric clinics (Stevens 2002), and one through telephone recruitment (Bauman 2002).

Among the selective interventions, three studies recruited participants specifically from low socioeconomic status or at‐risk areas, with two of these recruiting through schools (Baldus 2016; Stormshak 2011), and one through community organisations and recreation centres (Wu 2003). Four recruited youth who had identified behaviour problems (recruited through schools ‐ Cordova 2012), delinquency (recruited through the juvenile justice system ‐ Dembo 2001; Prado 2012), or emotional or behavioural disorder (referred from mental health clinics, truancy courts, or response to advertisements ‐ Spirito 2015). Three studies targeted children of at risk parents, with one recruiting families through a methadone clinic (Catalano 1999), one recruiting the children of depressed parents through health clinics (Mason 2012), and one recruiting the children of divorced parents identified through court records (Wolchik 2002). One study targeted families with a homeless adolescent recruited through community organisations such as shelters (Milburn 2012). One further study targeted girls from minority ethnic groups identified through community advertisements (Fang 2010).

The seven indicated interventions all involved youth who were already identified as using or abusing alcohol. Two studies recruited participants who attended a paediatric emergency department or trauma centre after an alcohol‐related incident (Arnaud 2016; Spirito 2011), one recruited gang‐affiliated youths via a street‐based outreach approach (Valdez 2013), and one recruited youth who had been identified in a school setting as abusing alcohol and other drugs (Winters 2012). The remaining three studies relied on referrals from truancy courts, schools, juvenile justice, or welfare agencies (Liddle 2008; Spirito 2017; Stanger 2017).

Setting and mode of delivery

Researchers delivered interventions in a range of settings including the child's school, the child's family home, and the Internet or delivered print material. Of the universal interventions, they delivered eight to parents via print materials or audio CD sent by post or via email, or sent home with children (Bauman 2002; Mares 2016; O'Donnell 2010; Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2004; Werch 2008; Wurdak 2017), with one sent by post (n = 1; O'Donnell 2010); four were computer mediated (Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011); two involved presentations or workshops at the child's school (Bodin 2011; Fosco 2013); and ten involved face‐to‐face sessions, with a combination of group/individual/family sessions delivered at the school or in a community venue (Brody 2006; Estrada 2017; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Koning 2009; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002), or at individual parent/family sessions provided in the family home (Loveland‐Cherry 1999), or in a healthcare setting (Linakis 2013; Stevens 2002).

Of the selective interventions, one was delivered via CD‐ROM and Internet (Fang 2010), and ten via face‐to‐face sessions using a combination of group, individual parent, and family approaches (Baldus 2016; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Spirito 2015; Stormshak 2011; Wolchik 2002). Individual parent and family sessions were most commonly delivered in the family home. One study involved face‐to‐face sessions for youth only and a 20‐minute video for parents (Wu 2003). All indicated interventions were delivered through face‐to‐face sessions with parents and youth separately or together, or by a combination of both.

Across all trials, programme intensity varied from six sessions of 20 minutes' duration delivered over three years (Bodin 2011), to twice weekly 90‐minute meetings, a five‐hour retreat, and group workshops occurring over a nine‐month period (Catalano 1999). In general, the selective and indicated interventions were of a consistently higher intensity than the universal ones, with all but one ‐ Fang 2010 ‐ involving at least one face‐to‐face session. Face‐to‐face interventions varied in duration/frequency from a single session in Arnaud 2016 to weekly sessions over periods ranging from five (in Milburn 2012) to 16 weeks (in Valdez 2013) to annual sessions provided over three years (Bodin 2011; Fosco 2013). Interventions delivered by other means also varied, with some spread over four weeks (Wurdak 2017), and others up to six months (Bauman 2002). Duration of follow‐up ranged from immediate post‐test to 15 years post intervention (Wolchik 2002). A small number of trials reported follow‐up beyond four years post randomisation (n = 2; Furr‐Holden 2004; Wolchik 2002); we did not include these trials in the meta‐analysis.

Interventions and comparisons

Although the interventions implemented varied in intensity, duration, and approach, all targeted alcohol or other drug use, and generally did so by promoting positive parenting approaches or by enhancing parent‐child relationships. The interventions focused on elements such as communication, family dynamics, rule‐setting, and risk management. Of the 46 included studies, 23 included a separate youth component in the form of a classroom curriculum or other adolescent‐focused resource (n = 4; Catalano 1999; Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2004), or individual or group youth sessions (and/or involvement in family sessions) as part of face‐to‐face interventions (n = 18; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Estrada 2017; Foxcroft 2017; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2015; Spoth 2002; Stanger 2017; Stevens 2002; Valdez 2013; Winters 2012; Wolchik 2002).

Universal interventions

Of the universal interventions, eight targeted alcohol specifically (Bodin 2011; Brody 2006; Koning 2009; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mares 2016; Schinke 2004; Werch 2008; Wurdak 2017), 12 targeted substance use more generally (Bauman 2002; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Linakis 2013; Riesch 2012; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002), five targeted problem behaviours and substance use (Fosco 2013; Haggerty 2007; Perry 2003; Skarstrand 2014; Estrada 2017), and the remainder targeted alcohol as well as tobacco (Bauman 2002), sexual behaviour (O'Donnell 2010), or tobacco alone (Reddy 2002).

Six universal studies used the original structure or an adaptation of the Strengthening Families Program (SFP), which is based on the Social Development Model and aims to enhance parent and child interactions to reduce risk factors for substance use and substance use initiation (Brody 2006; Foxcroft 2017; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002). Investigators in each of these studies ran multiple face‐to‐face sessions over a period of several weeks. Generally in the first hour, parents and adolescents attended separate workshops before coming together for family workshops in the second hour. Workshop sessions were focused on skill‐building and relationship development, using role‐plays and games. The most common model for the Strengthening Families Program consisted of seven sessions over seven weeks and was used in four studies (Brody 2006; Foxcroft 2017; Riesch 2012; Spoth 2002). One study adapted the SFP to include two parts; part 1 included six separate parent and youth sessions and one family session, and part 2 involved four separate sessions and one joint session (Skarstrand 2014). One selective study also used the SFP in its seven‐session format with four booster sessions (Baldus 2016).

One of these studies assessed the SFP as a complement to a 15‐session classroom‐based curriculum of Life Skills Training (LST) for children in grades seven and eight (Spoth 2002), thereby investigating effects of the SFP via a comparative effectiveness approach (one arm was LST only, and the other LST plus SFP). Another study adopted a five‐session model of the SFP, with children only attending one of these sessions, and compared this to the Preparing for Drug Free Years (PDFY) programme involving six sessions with separate parent and child training, as well as a final session with the family (Spoth 1999a). The remainder of these SFP‐based studies compared the programme versus no programme (Riesch 2012;Skarstrand 2014), or versus an attention control involving the distribution of information leaflets via mail (Brody 2006;Foxcroft 2017).

Seven other universal studies also involved face‐to‐face sessions with small groups of individual parents or families (Estrada 2017; Fosco 2013; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Linakis 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Stevens 2002). Three studies involved group seminars or workshops for parents, with one providing nine sessions (Furr‐Holden 2004), one eight sessions (Estrada 2017), and one seven sessions (Haggerty 2007). Another study involved individual motivational interviewing‐based sessions with parents who were attending an emergency department with a child for a non‐alcohol‐ or drug‐related issue (Linakis 2013). This programme also included telephone booster sessions and mailings and was compared with an enhanced usual care approach including mailing of brochures about the influence of parents on adolescents. One universal study used home visits with families to deliver a motivational interviewing/social cognitive theory‐based intervention and to overcome barriers to assessment of parent elements of interventions and/or parent attendance at school events, with three home sessions plus boosters delivered to families from three school districts and compared with a no program control group randomised at the family level (Loveland‐Cherry 1999). The final universal study involving face‐to‐face sessions delivered at home did so only for families who were identified through the school‐based part of the programme as being at risk (Fosco 2013). As such, this component of the intervention was regarded as the selective component. The universal component of the intervention involved a family resource centre in schools and delivery of special interest face‐to‐face seminars for parents. This intervention was compared with a no programme control

Two universal studies used the Orebro Prevention Program or adaptation (Bodin 2011;Koning 2009). This programme involves presentations to parents at schools and the development of a set of agreed rules among parents. Both studies compared the programme versus a no intervention control, and Koning et al included three arms, also comparing the effectiveness of a student intervention (SI)) with and without the parent intervention (PI; SI+/‐PI versus PI) (Koning 2009).

The remaining 11 universal studies used either paper or computer‐based modules with no face‐to‐face component. Eight studies involved mailing material to parents (e.g. booklets, postcards, audio‐CDs; Bauman 2002; Mares 2016; O'Donnell 2010; Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2004; Werch 2008; Wurdak 2017). Four of these studies compared parent mailings versus a no program or waitlist control (Bauman 2002; Mares 2016; O'Donnell 2010; Wurdak 2017), and four were comparative effectiveness trials (Perry 2003; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2004; Werch 2008), in which parent mailings were assessed as a complement to, or in comparison to, an alternate intervention such as a classroom curriculum (Perry 2003; Reddy 2002), a CD‐ROM programme for adolescents (Schinke 2004), or a set of alternate adolescent postcards (Werch 2008). Four studies were based on mother‐daughter education and a cognitive‐behavioural skills training approach using computer‐ or CD‐ROM‐mediated sessions, all compared with a no program control (Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011).

Selective interventions

Of the selective interventions, only one study targeted alcohol specifically (Stormshak 2011), with three targeting alcohol and substance use (Fang 2010; Mason 2012; Spirito 2015), and eight targeting alcohol/substance use (Baldus 2016; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Wolchik 2002; Wu 2003), along with other problem behaviours such as unsafe sex in Prado 2012 or selling drugs in Wu 2003.

Less variation existed in the interventions delivered in selective studies compared to universal interventions. Ten studies used face‐to‐face sessions with a mixture of group, parent only, or family counselling based on the principles of motivational interviewing, cognitive‐behavioural therapy, or similar counselling approaches (Baldus 2016; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Mason 2012; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Spirito 2015; Stormshak 2011; Wolchik 2002). The 'intensity' of these interventions ranged from a single family session with assessment task and boosters delivered by mail, as in Spirito 2015, to multiple home visits with families. Two studies used the Family Check‐Up intervention, comprising assessment, feedback, and motivational interviewing principles (Spirito 2015; Stormshak 2011). One study involved five sessions with youth and parents at home (Milburn 2012), two studies involved ten such visits (Dembo 2001; Mason 2012), and one study involved nine group sessions as well as ten family sessions (Family Unidas; Cordova 2012). One study involved 11 group sessions with mothers as well as two individual sessions tailored to the intervention (Wolchik 2002). One study involved a total of 54 contact hours per family, with a mixture of group and individual sessions and a parent retreat (Catalano 1999). Only two selective studies did not involve face‐to‐face contact with parents, with one using a nine‐session web‐based programme targeting mothers' relationships with their daughters (Fang 2010), and the other complementing a face‐to‐face youth programme with a 20‐minute video for parents (Wu 2003).

Most of these selective studies compared an intervention versus either standard practice (e.g. standard methadone clinic, standard referral processes; Catalano 1999; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012), an enhanced 'usual care' condition (Baldus 2016; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Wolchik 2002), or no programme (Fang 2010; Mason 2012; Stormshak 2011). Two selective studies were comparative effectiveness trials that compared the intervention versus an alternative, such as a psychoeducational session in Spirito 2015 or a child‐focused intervention in Wu 2003.

Indicated interventions

Of the indicated interventions, one specifically targeted alcohol (Spirito 2011); three targeted risk behaviours and drug use (including alcohol) (Arnaud 2016; Liddle 2008; Valdez 2013); one targeted substance use including alcohol (Winters 2012); and two targeted alcohol and marijuana use (Spirito 2017; Stanger 2017). In all cases, we considered for this review only outcomes related specifically to alcohol.

All indicated interventions included face‐to‐face sessions based on motivational interviewing (Arnaud 2016; Liddle 2008; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2017), cognitive‐behavioural therapy (Stanger 2017), or brief intervention principles (Valdez 2013; Winters 2012). Intensity varied, with two studies involving a single family motivational interviewing session, as well as a youth component (Spirito 2011; Spirito 2017); one involving two sessions with youth and one with a parent (Winters 2012); and one involving 16 family therapy sessions (Valdez 2013). These interventions were compared with usual care (e.g. referrals, social and behavioural services; in Arnaud 2016 and Valdez 2013) or a no programme control (Winters 2012), and four studies compared the effectiveness of family or parent therapy with adolescent motivational interviewing (Spirito 2011), cognitive‐behavioural therapy (Liddle 2008), or psychoeducation (Spirito 2017). One indicated study compared abstinence‐based incentives in the intervention group versus attendance‐based incentives in the control group (Stanger 2017).

Outcomes

We grouped outcome measures used in meta‐analysis as prevalence, frequency, or volume. Twenty studies reported measures of prevalence (Baldus 2016; Bauman 2002; Bodin 2011; Brody 2006; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Koning 2009; Mares 2016; O'Donnell 2010; Prado 2012; Reddy 2002; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002; Wu 2003). These studies included those assessing 'initiation' of or any alcohol in the child's lifetime (Baldus 2016; Bauman 2002; Brody 2006; Foxcroft 2017; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Mares 2016; Reddy 2002; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spoth 1999a; Spoth 2002; Stevens 2002), some of which also reported this measure for a cohort of baseline non‐drinkers (Baldus 2016; Bauman 2002; Brody 2006); those reporting the lifetime prevalence of drunkenness (Skarstrand 2014); and those reporting the prevalence of weekly use (Bodin 2011), or use in the last 90 days (Cordova 2012; Prado 2012), 6 months (Catalano 1999; Wu 2003), or 12 months (O'Donnell 2010).

Seventeen studies reported alcohol use frequency outcomes (Arnaud 2016; Dembo 2001; Estrada 2017; Fang 2010; Liddle 2008; Linakis 2013; Milburn 2012; Perry 2003; Schinke 2004; Schinke 2009b; Spirito 2011; Stanger 2017; Valdez 2013; Werch 2008; Winters 2012; Wolchik 2002; Wurdak 2017). These studies all reported on the number of occasions of drinking, with the exception of one study that reported on occasions of binge drinking (Arnaud 2016). Most studies reported frequency of use in the past 30 days (Dembo 2001; Fang 2010; Liddle 2008; Linakis 2013; Schinke 2004; Schinke 2009b; Spirito 2011; Valdez 2013; Werch 2008; Wolchik 2002; Wurdak 2017), and others reported use over time periods of 90 days (Estrada 2017; Milburn 2012; Winters 2012), 36 weeks (Stanger 2017), or 12 months (Perry 2003).

Ten studies reported alcohol use volume outcomes (Arnaud 2016; Fosco 2013; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mason 2012; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Spirito 2015; Spirito 2017; Stormshak 2011). Most reported on the number of drinks consumed in the past 30 days (Arnaud 2016; Fosco 2013; Mason 2012; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009c; Schinke 2011; Spirito 2017; Stormshak 2011), and two studies used a quantity‐frequency scale calculated over 3 months in Spirito 2015 and over 12 months in Loveland‐Cherry 1999.

Excluded studies

A total of 179 records remained after title and abstract screening, of which 176 full‐text articles were located for further review. We considered 85 articles to be ineligible after assessment of the full text (reasons for exclusion were study design (N = 15), participants (N = 4), interventions (N = 34), and outcomes (N = 32)). See Characteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Studies awaiting classification

We could not determine the eligibility of three trials, as no full text was available. See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We identified 16 ongoing trials by their published protocol or by a clinical trial registration, for which neither published nor unpublished data were available (Characteristics of ongoing studies). These include five trials regarded as universal, two as selective, and nine as indicated.

The universal trials included a C‐RCT comparing a range of health interventions for adolescents, including one related to alcohol and delivered to parents (Ford 2015); an RCT of the Strengthening African American Families STEPS program targeting 11‐15 year‐olds (Kogan 2018), an RCT comparing the Family Matters and Strengthening Families programmes (vs a no program control group) among families with an 11‐ or 12‐year‐old child attending Kaiser Permanente medical centres (Miller 2009); an RCT of a web‐based 'Smart Choices 4 teens' program targeting alcohol and sexual behaviour (Miller 2018), and a C‐RCT of a UK adaptation of the Strenthening Families Program, comparing a seven‐session model versus usual care (Segrott 2014).

The selective trials included an RCT testing the effects of a parenting programme for Latino families versus a waitlist control (Allen 2012), along with an RCT testing an American Indian adaptation of the Strengthening Families programme with orientation towards cultural traditions of Anishinaabe communities versus a no intervention control group (Whitbeck 2016).

The indicated intervention trials included an RCT trialling home‐based behavioural therapy for adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorder and regular substance use versus usual care (Bukstein 2006); a C‐RCT testing an extensive prevention programme involving adolescent and parent components and an indicated component for youth with symptoms of mental health or substance use problems versus treatment as usual (Conrod 2017); an RCT testing the feasibility of a motivational enhancement therapy intervention for adolescents with and without a parenting wisely programme for parents and a drug education programme for adolescents with and without a parenting wisely programme for parents among adolescents with drug‐related charges (Hops 2012); an RCT of enhanced contingency management for adolescents with a current substance use disorder, with and without a parent management training programme (McCart 2017); an RCT of adolescent brief intervention and an e‐parenting skills intervention for parents of adolescents admitted to a trauma service with a positive screening for alcohol or drug use compared to brief intervention alone (Mello 2016); an RCT of multi‐dimensional family therapy compared to family motivational interviewing and a standard care control group for adolescents presenting to the emergency room or trauma unit with alcohol problems (Rowe 2010); an RCT of a contingency management programme compared to usual care for youth in the justice system with a newly opened probation case (Sheidow 2017); an RCT of a computer‐assisted motivational interviewing programme and an online parenting wisely programme for adolescents in the justice system who have a positive result for marijuana use on intake (Spirito 2017b); and an RCT comparing adolescent group therapy versus transitional family therapy for adolescents with a DSM‐IV diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence (Stanton 2007).

Risk of bias in included studies

The assessment results of risk of bias for the included studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. None of the 46 included studies were at low risk in all risk‐of‐bias domains (Higgins 2011). Overall eight studies were regarded as high risk (with three or more 'high' ratings) for the purpose of sensitivity analysis.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We rated 11 of the 46 studies at low risk of bias for random sequence generation. Four studies used a computer‐generated random number sequence (Mares 2016; Stevens 2002; Valdez 2013; Wolchik 2002), four studies used urn randomisation (Cordova 2012; Spirito 2015; Spirito 2017; Winters 2012), one study used minimum likelihood allocation (Stanger 2017), and two studies used a coin toss (Bodin 2011; Milburn 2012). We judged the method of sequence generation in one study to be high risk, as four of 20 communities were not randomised and their data were retained (Foxcroft 2017). For the remaining 34 studies, the method of sequence generation was unclear.

Allocation concealment

Of the 46 studies, only seven provided sufficient detail to establish that participant allocation to experimental groups was concealed from those conducting the research; we rated these as having low risk of selection bias for this domain (Bodin 2011; Foxcroft 2017; Koning 2009; Milburn 2012; Prado 2012; Spirito 2011; Spirito 2017). We were unable to make a judgement on the remaining 39 studies using the details provided; therefore, those studies had unclear risk of selection bias with regard to allocation concealment.

Blinding

In all 46 studies, blinding of participants and programme deliverers (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) was not achievable due to the nature of the interventions tested and because the outcomes were self‐reported; therefore, we rated these studies as having high risk of performance and detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We rated 20 studies at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data, as they reported less than 20% loss of participants and showed no differential attrition between experimental groups (Arnaud 2016; Baldus 2016; Catalano 1999; Cordova 2012; Dembo 2001; Estrada 2017; Fang 2010; Furr‐Holden 2004; Haggerty 2007; Linakis 2013; Mason 2012; O'Donnell 2010; Perry 2003; Prado 2012; Reddy 2002; Schinke 2009a; Schinke 2009b; Werch 2008; Winters 2012; Wolchik 2002). Sixteen studies had high risk of bias due to high attrition rates (> 20%) or had less than 20% loss of participants but unequal attrition between experiment groups (Bodin 2011; Foxcroft 2017; Koning 2009; Liddle 2008; Loveland‐Cherry 1999; Mares 2016; Milburn 2012; Riesch 2012; Skarstrand 2014; Spirito 2011; Spoth 1999a; Stanger 2017; Stevens 2002; Valdez 2013; Wu 2003; Wurdak 2017). We rated the remaining 10 studies as having unclear risk for incomplete outcome data, as details were insufficient to permit a judgement.

Selective reporting

Five studies had low risk of reporting bias, as outcomes reported were consistent with the prespecified clinical trial registries and/or the study protocol (Bodin 2011; Furr‐Holden 2004; Mares 2016; Spirito 2011; Wurdak 2017). We judged two studies to be at high risk of reporting bias ‐ the first as a direct comparison of the intervention group versus the control group was not presented (Dembo 2001), and the second because an outcome referred to in the protocol was not reported (Foxcroft 2017). We rated the remaining 39 studies as having unclear risk for incomplete outcome data, as details were insufficient to permit a judgement.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed the potential for contamination bias as another potential source of bias in the 46 studies and judged only one study to be at high risk of contamination (Skarstrand 2014), as study authors noted that control schools were exposed to other alcohol interventions during the intervention period.

For the 16 C‐RCTs, we assessed risk of recruitment bias, baseline imbalances, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and compatibility with individually randomised trials (herd effect). We considered seven studies to have low risk of recruitment bias based on appropriate recruitment techniques applied before allocation to clusters, seven to have high risk of bias (based on individual allocation to clusters occurring after randomisation), and the remaining studies to have unclear risk of bias (based on insufficient information). For baseline imbalances, we considered all studies to be at low risk of bias based on similar characteristics of groups at baseline (no baseline imbalances or imbalances accounted for in the analyses), except two studies that provided insufficient information to permit judgement (Arnaud 2016; Spoth 1999a). Only one study had high risk of bias for loss of clusters (Koning 2009). We judged all 16 studies as having low risk for incorrect analysis (based on adequate adjustment for the effect of clustering); however, review authors were required to adjust for clustering on behalf of the authors of four studies (i.e. we did not rate these studies as high risk because we were able to address the lack of adjustment for clustering; Brody 2006; Schinke 2004; Spoth 1999a; Wu 2003). Information was insufficient to permit judgement of the herd effect for all studies.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Family/parent interventions compared with control for reducing alcohol consumption in adolescents.

| Family/parent interventions compared with no intervention/standard care for prevalence of adolescent alcohol consumption | ||||||

|

Patient or population: parents/children Settings: recruitment through schools (n = 11), communities (n = 6), paediatric emergency departments (n = 2), other health clinics (n = 2); referral by schools, the justice system, therapists, physicians, or parents (n = 1); street‐based recruitment (n = 1) or random digit dialling (n = 1); and delivery via resources sent home (n = 3); face‐face in schools, homes, or community venues (n = 14); or via the Internet or computer (n = 2) Intervention: parent interventions (positive parenting and communication and counselling sessions) Comparison: no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Risk with no intervention | Risk with parent intervention | |||||

|

Alcohol use prevalence Up to 4 years post intervention impact of family/parent interventions compared to control on the prevalence of alcohol consumption or drunkenness |

Mean prevalence of lifetime alcohol use was 85%a | Mean prevalence of lifetime alcohol use in intervention groups was zero (0.16 lower to 0.16 higher) | 7490 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | Scores estimated using a standardised mean difference of 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.08) | |

|

Alcohol use frequency Up to 4 years post intervention impact of family/parent interventions compared to control on the frequency of alcohol consumption |

Mean number of drinking days in previous 90 days was 2.5c | Mean number of drinking days in intervention groups was 0.16 lower (0.42 lower to 1.1 higher) | 1855 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd | Scores estimated using a standardised mean difference of ‐0.31 (95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.21) | |

|

Alcohol use volume Up to 4 years post intervention impact of family/parent interventions compared to control on the volume of alcohol consumption or drunkenness |

Mean number of drinks in the last 30 days among control groups was 0.83e | Mean number of drinks in intervention groups was 0.18 lower (0.34 lower to 0.00 higher) | 1825 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowf | Scores estimated using a standardised mean difference of ‐0.14 (95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.00) | |

| Adverse events | No studies reported this outcome | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||