Abstract

CD160 is highly expressed by natural killer (NK) cells and associated with cytolytic effector activity. Herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM) activates NK cells for cytokine production and cytolytic function via CD160. Fc-fusions are a well-established class of therapeutics, where the Fc-domain provides additional biological and pharmacological properties to the fusion protein including enhanced serum half-life and interaction with Fc-receptor-expressing immune cells. We evaluated the specific function of HVEM in regulating CD160-mediated NK cell effector function by generating a fusion of the HVEM extracellular domain with human IgG1 bearing CD16-binding mutations (Fc*) resulting in HVEM-(Fc*). HVEM-(Fc*) displayed reduced binding to the Fc-receptor CD16, i.e. Fc-disabled, which limited Fc-receptor-induced responses. HVEM-(Fc*) functional activity was compared with HVEM-Fc, containing the wild type human IgG1 Fc. HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of NK cells and PBMCs caused greater IFN-γ production, enhanced cytotoxicity, reduced NK fratricide and no change in CD16 expression on human NK cells compared to HVEM-Fc. HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of monocytes or PBMCs enhanced the expression level of CD80, CD83, and CD40 expression on monocytes. HVEM-(Fc*)-enhanced NK cell activation and cytotoxicity were promoted via crosstalk between NK cells and monocytes that was driven by cell-cell contact. Here, we have shown that soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*) augments NK cell activation, IFN-γ production, and cytotoxicity of NK cells without inducing NK cell fratricide by promoting crosstalk between NK cells and monocytes without Fc-receptor-induced effects. Soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*) may be considered as a research and potentially therapeutic reagent for modulating immune responses via sole activation of HVEM receptors.

Introduction:

Natural killer (NK) cells, a subset of lymphoid cells, are an essential component of the innate immune system that protects against viruses (e.g. HCMV, HIV, and HCV), tumor cells and other pathogens (1–5). NK cell innate immune responses are tightly regulated by multiple activating and inhibitory receptors. Unlike typical activating and inhibitory receptors on NK cells, CD160 is tightly regulated in two alternative splice variants: a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored (CD160-GPI) form and a differentially spliced transmembrane form of the protein (CD160-TM) that is unique to NK cells. CD160 is part of the immunoglobulin superfamily of receptors and it is predominantly expressed in peripheral blood NK cells, γδ T (6) and CD8 T lymphocytes (7)(8) with cytolytic effector activity. In circulating cells, the highest expression of CD160 RNA is identified in peripheral blood CD56dimCD16+ NK cells, greater than CD8 T cells (9). CD160 signals upon engagement of the widely expressed molecules HVEM and/or HLA-C (10–12). The engagement of CD160 by soluble HVEM (HVEM conjugated to the Fc portion of IgG1) or HVEM expressed on the cell surface was shown to activate NK cells (10). Genetic deficiency of CD160 in mice specifically impairs NK cell production of IFN-γ, which is an essential component of the innate response to control tumor growth (13).

Herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM) is a member of the TNF receptor (TNFR) superfamily and is expressed on many immune cells, including NK cells, T and B cells, monocytes, and neutrophils (14–18). HVEM is an immune regulatory molecule (15, 18) that signals bi-directionally both as a receptor and a ligand. HVEM interacts with three cell surface molecules, CD160, LIGHT (homologous to lymphotoxins, shows inducible expression, and competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for HVEM, a receptor expressed by T-lymphocytes) and BTLA (B- and T-Lymphocyte Attenuator) and in humans with Lymphotoxin-α (LT-α or TNF-β) (14–18). HVEM generates bi-directional signals and recent literature provides evidence of signaling induced by interaction between HVEM and CD160, LIGHT, BTLA or LT-α in different immune cells (7, 15, 19–25). The extracellular domain of HVEM was fused to the Fc portion of human IgG1 in previous studies to produce a soluble protein used to detect HVEM ligands, or alternatively to specifically activate BTLA or CD160 receptors (10, 26, 27). Because human IgG1 Fc binds to Fc receptor expressed on innate cells, including NK cells, HVEM-Fc fusion proteins may engage receptors for both the HVEM domain and the Fc domain. Fc fusion proteins have been widely used to interrogate the activities of cell surface proteins or soluble molecules, and are widely used in immunotherapies such as etanercept, alefacept and abatacept. The Fc domain of these fusion proteins may contribute biological activities unrelated to the fusion partner and which can be removed through mutation of the Fc domain. In order to determine how HVEM engagement of NK cells may specifically function to activate NK cells in the absence of Fc receptor binding, we generated fusion proteins constructed of the extracellular domain of HVEM conjugated to a mutant human IgG1 Fc that does not bind to Fc receptor (HVEM-(Fc*)) (28).

LIGHT, a member of the TNF ligand superfamily, is mainly expressed on T cells, monocytes, NK cells, and immature dendritic cells (29) and binds to HVEM and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR), two membrane receptors (30). LIGHT-HVEM interactions are thought to regulate a variety of immune responses. For example, costimulation of T cell proliferation, polarizing CD4 T cells into Th1 cells and associated cytokine production (31), inducing dendritic cell maturation (31), stimulating Ig production in B cells (32), and activating NK cells (19). This interaction enhances phagocytosis of monocytes and neutrophils and contributes to antibacterial activity via production of ROS, NO, other proinflammatory cytokines and direct bactericidal activity (33). On the other hand, engagement of HVEM with BTLA on T cells inhibits anti-TCR induced activation and cytokine secretion (34).

The expression of CD160, LIGHT, and BTLA varies greatly between different cell types, activation, and differentiation states (14, 18, 34, 35). NK cells mainly express CD160 and little to no expression of LIGHT or BTLA (14, 18, 34, 35). In contrast, monocytes, bone marrow derived DC and other immune cells express mainly LIGHT and little to no expression of BTLA or CD160 (14, 18, 34). Thus, dynamic regulation of these receptors especially on NK cells and cells interacting with NK cells via HVEM signaling provide a potential mechanism for control of activating and inhibitory signals depending on cellular context.

NK cells interact with other immune cells for optimal cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and control of virally infected or tumor cells (36–47). There are several reports showing that monocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages interact with NK cells and cooperate in the innate immune response for protection against pathogens (36–47). However, the role of HVEM-CD160 interactions in the activation of NK cells by other accessory cells expressing HVEM, its ligands or Fc receptors is not known. In this study, we investigated the role of soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*)-induced activation of NK cells and regulation of NK-mediated effector responses.

Material and Methods

Cells

Fresh human blood was collected from healthy donors giving written informed consent at Case Western Reserve University, and the Institutional Internal Review Board approved all handling. PBMCs were isolated by Lymphoprep (STEMCELL Technologies) density gradient centrifugation as per manufacturer’s description from fresh human blood and fresh leukocyte reduction filters obtained from Red Cross, Cleveland and cryopreserved where indicated. NK cells were isolated from PBMC by negative selection using the NK enrichment Kit (STEMCELL Technologies). Monocyte isolation was performed by positive selection using CD14 microbeads and MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). HVEM expressing CHO cells (HVEM-CHO) were obtained from K. G. Kousoulas. CD160-CHO and HVEM-CHO were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin.

Reagents and monoclonal antibodies

Soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*) was custom synthesized by G&P, Santa Clara, CA, USA and demonstrated to having binding activity to recombinant BTLA and LIGHT protein, and also inhibit LIGHTmediated signaling activities including cytotoxicity in L-929 mouse fibroblast (48). Soluble-CD160 and HVEM-His were purchased from SinoBiologicals, Beijing, China. HVEM-Fc was purchased from G&P and PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ USA. The purity of fusion proteins by SDS-PAGE were: HVEM-(Fc*) >95% pure and endotoxin level <0.1 EU/μg of protein; HVEM-Fc >95% pure, endotoxin level: <0.1 EU/μg of protein; HVEM-his, >90% pure, endotoxin level: <1EU/μg of protein; CD160-his, >95% pure, endotoxin level: <1EU/μg of protein. Alefacept was a generous gift from K.D. Cooper, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH. Anti-CD3-PE, AF700 or APC-Cy7, anti-CD56-BV785 or PE-Cy7, anti-CD16-APC (Southern Biotech) or BUV395 (BD Bioscience), anti-CD19-PE, anti-CD20-PE anti-CD80-FITC, anti-CD83-BV421, anti-CD86-PE-Cy7, anti-CD14-AF700, anti-CD69-APC or APC-Cy7, anti-CD107a-APC-Cy7 mAb, anti-LIGHT-PE, anti-BTLA-BV510, and the corresponding isotype controls, were from Biolegend. AF488 labeled anti-CD160 and unlabeled anti-CD160 mAbs (clone 688327) were from R&D. The anti-CD160 mAb (688327) was reported as a CD160 blocking antibody (49). We confirmed that 20 μg/ml of anti-CD160 mAb (clone 688327) could completely block binding of 4 μg/ml of HVEM-Fc to CD160 on the CD160-expressing CHO (CD160-CHO) cells (data not shown). Hence, 20 μg/ml of anti-CD160 mAb was used in the blocking experiments. Annexin-V-PE, and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) were purchased from eBioscience and Biolegend respectively. Cytokines IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, IFN-β were purchased from PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ USA.

We used CD160-his and hIgG1 as controls for HVEM-his and HVEM-(Fc*)/HVEM-Fc, respectively. CD160-his binds to HVEM-expressing CHO cells but NK cells treated with CD160-his didn’t cause IFN-γ production compared to HVEM-his (data not shown). Since CD160-his didn’t induce any functional responses similar to observations with hIgG control or media control, we have used hIgG1 as the control for HVEM-(Fc*). However, we acknowledge that the appropriate control would be a fusion protein bearing an irrelevant protein fused with (Fc*) and/or production of an HVEM-(Fc*) fusion protein mutated for loss of HVEM function to assess HVEM-(Fc*)-induced responses. However, this was not synthesized because we observed the same response from CD160-His and hIgG1 and were resource limited.

Immunophenotyping of cells by flow cytometry

PBMCs within the live gate (7-AAD negative population) were analyzed for expression of HVEM and its receptors on CD56dim NK cells (CD14−/CD19−/CD3−/CD56dim), CD56bright NK cells (CD14−/CD19−/CD3−/CD56bright), and CD14+ monocytes (CD14+/SSChigh) by flow cytometry (BD LSRII) and data were analyzed by Flowjo (Version 10.1, TreeStar).

Cytokine-expression analysis

Supernatants from PBMC, NK cells, monocytes and NK cell and monocyte coculture were analyzed for IFN-γ by ELISA (Capture antibody (clone M700A) and biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (clone M701B) were from Thermofisher) and were also analyzed by 65-plex Luminex array (Eve Technologies).

Assessment of Fc binding to CD16 and HVEM binding to CD160

To assess the binding of the Fc stalk of HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) to CD16, beads conjugated with anti-His monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA) were treated by His-tag conjugated recombinant human CD16a (rhCD16a) at 4°C for 2 h. Pre-bound rhCD16a beads (0.3 × 106) were incubated with human IgG1 (hIgG1; 10 μg/ml), HVEM-Fc (PeproTech; 10 μg/ml), HVEM-Fc (G&P; 10 μg/ml) or HVEM-(Fc*) (G&P; 10 μg/ml) on ice for 45 min. Then, beads were stained with anti-HVEM-PE mAb (1μg/ml) at 4°C for 30 min and were analyzed by flow cytometry.

To assess the binding capacity of HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) to CD160, CHO cells expressing CD160 (CD160-CHO cells) were incubated with human IgG1 (hIgG1) (10 μg/ml or 40 μg/ml), HVEM-Fc (PeproTech: 5 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml) or HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) (G&P; 10 μg/ml, 20 μg/ml or 40 μg/ml) on ice for 45 min. After washing, cells were incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti-hIgG Fc secondary antibody on ice for 45 min. Then, cells were washed and stained with mouse anti-human HVEM-PerCP-Cy5.5 (2μg/ml) antibody at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

NK cell cytotoxicity assay

Frozen PBMCs from healthy controls were thawed and cultured overnight in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. PBMCs were then incubated with or without 1μg/ml HVEM-(Fc*) for 42–44 hrs. Activation marker, CD69, on NK cells was measured after 44 h by flow cytometry. PBMC were further cocultured with pre-labeled K562 cells at an Effector to Target (E:T) ratio of 20:1 in the presence of anti-CD107a-APC-Cy7 for 5 h. K562 cells were stained with 7AAD and Annexin-V-PE to quantitate dead cells (7AAD+Annexin-V+) by flow cytometry.

Where described, cytotoxicity assays were performed using purified NK cells (purity ≥95%) and monocytes (MN; purity ≥95%) in co-cultures. Briefly, NK cells were purified from thawed overnight-cultured PBMC by negative selection. Monocytes were purified by CD14 positive selection from the same donor. Purified NK cells (0.3 ×106), purified monocytes (0.3 ×106), or purified NK cells + purified monocytes co-culture at a ratio of 1:1 (0.3 ×106 + 0.3 ×106) was performed in the presence or absence of HVEM-(Fc*) (1 μg/mL) for 44 h. After 44 h, cells were then stained for activation markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. NK cells, monocytes, or NK cells + monocyte mixture were further co-cultured with labeled K562 cells at a ratio of NK cells to K562 cells = 1.5:1 for 5 h in the presence of anti-CD107a mAb-APC-Cy7 or its isotype control antibody. The co-cultured cells were then stained with 7-AAD and Annexin-V-PE to quantitate the dead cells (7AAD+Annexin-V+) by flow cytometry. For transwell cultures (96-well plate), NK cells (0.3 × 106 cells/well) were seeded into the lower chamber and monocytes (0.3 × 106 cells/well) were seeded in the upper chamber or both NK cells + monocyte mixture (1:1) were seeded in the lower chamber and were cultured in the absence or presence of HVEM-(Fc*) for 44 h. Activation markers and cytotoxicity were measured identically to above in non-transwell cultures.

We performed reverse ADCC using the well-characterized P815 mouse mastocytoma cell line that abundantly expresses mouse CD16 (mouse Fc receptor) as a target cell to evaluate the activity of HVEM-(Fc*)-induced activation of NK cells. This is a well-studied model, similar to K562 killing assays for spontaneous killing, to ascertain reverse ADCC with a defined system. A mouse anti-human CD16 monoclonal is used to bridge human NK cell effectors with mouse P815 mastocytoma targets resulting in reverse ADCC (50). Briefly, the NK cells were pre-treated with either HVEM-Fc, HVEM-(Fc*), or IgG1 for 16 h. Cells were washed to remove the unbound stimuli (HVEM-Fc, HVEM-(Fc*), or IgG1) and then were co-cultured with P815 target cells in the presence of mouse anti-human CD16 antibody (containing a murine Fc stalk) or its isotype control antibody to evaluate the effect of HVEM-(Fc*) on NK cell reverse ADCC.

Statistical analysis:

Student paired t-test was performed to determine the difference between two groups unless otherwise indicated. All tests were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results:

Soluble HVEM-(Fc*) activates NK cells and induces IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity independent of Fc binding..

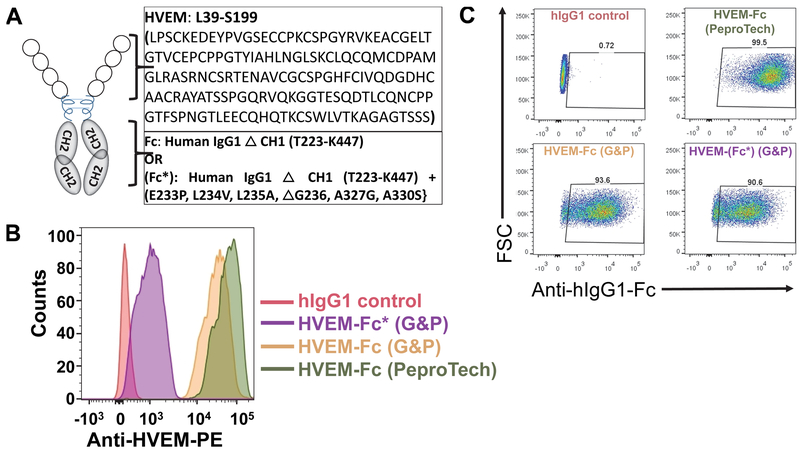

HVEM-Fc fusion proteins have been used to study the interaction between HVEM and its ligands on NK cells and immune responses (10, 49, 51–53). We sought to determine how a soluble HVEM-Fc fusion may function independent of Fc receptor interactions through mutation of residues required for Fc receptor binding (28, 54, 55). The entire HVEM extracellular domain was conjugated to a loss of function Fc stalk (Fc*) of human IgG1 (HVEM-(Fc*)) that has been previously shown to lack Fc receptor functionality (Fig. 1A). Six amino acids were mutated at position E233P, L234V, L235A, ΔG236, A327G, A330S on the Fc* stalk of human IgG1 as described in ref. (28). The binding capacity of the Fc* stalk of HVEM-(Fc*) was tested using rhCD16a conjugated beads by flow cytometry. HVEM-(Fc*) had significantly reduced MFI (1267 ± 421) compared to HVEM-Fc MFI (67266 ± 5232) (Fig. 1B). These data show that the loss of function Fc* stalk of HVEM-(Fc*) does not bind efficiently to rhCD16a-conjugated beads compared to HVEM-Fc containing the wild type Fc stalk. The binding capacity of HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) to CD160 was tested using CD160 expressing CHO cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, both HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) had comparable MFI (7814 ± 587 and 6900 ± 469 respectively) and percentage HVEM+ positive cells (93% ± 3% vs. 88% ± 4%). Taken together, these data demonstrate that HVEM binding to CD160 is comparable for both HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) but binding to the FcR of HVEM-(Fc*) is reduced 50-fold compared to HVEM-Fc. As an additional control, we used HVEM-His (which does not contain an Fc binding stalk) to determine HVEM ligand function uncoupled from Fc-FcR effects in subsequent experiments.

Figure 1: Soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*) structure, sequence and binding capacity.

(A) Schematic diagrams of HVEM-Fc and HVEM-(Fc*) fusion proteins. The HVEM-Fc fusion protein includes the extracellular domain of HVEM protein (amino acid residues from L39 to S199) and the CH1 deleted Fc stalk (amino acid residues T223-K447) of human IgG1. Soluble Fc-disabled HVEM-(Fc*) fusion protein was generated by mutating six amino acid residues at position E233P, L234V, L235A, ΔG236, A327G, A330S in the CH2/CH3 Fc stalk (from T223-K447) and then fusing this loss of function stalk to the same extracellular region of HVEM (amino acid residues from L39 to S199). (B) Recombinant human CD16a (Fc receptor) pre-conjugated beads were incubated with 10 μg/ml of human IgG1 (hIgG), HVEM-Fc (from PeproTech or G&P) or HVEM-(Fc*) (from G&P) on ice for 45 min. After washing, beads were stained with PE-conjugated anti-HVEM mAb (1 μg/ml) and analyzed by flow cytometry. X-axis shows the fluorescence intensity of beads incubated with hIgG1, HVEM-Fc (PeproTech and G&P) or HVEM-(Fc*) (G&P). (C) CD160-expressing CHO cells (CHO-CD160) were incubated with 10 μg/ml of hIgG1, HVEM-Fc (PeproTech and G&P) or HVEM-(Fc*) (PeproTech) on ice bath for 45 min. After washing, cells were incubated with PerCP-Cy5.5 conjugated mouse anti-human IgG-Fc mAb (2 μg/ml) and then cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of HVEM+ cells are shown.

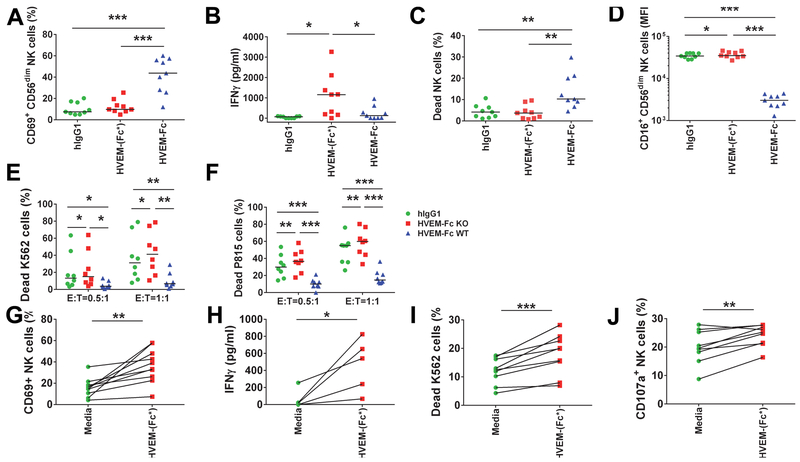

To evaluate the effect of HVEM on general activation of NK cells, we cultured purified NK cells with HVEM-(Fc*) and compared its effect with HVEM-Fc-induced responses. The percentage of NK cells expressing CD69 that were treated with HVEM-(Fc*) was similar to the percentage of NK cells that were treated with human IgG1 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, HVEM-Fc treatment increased 3.4-fold and 4-fold percentage of NK cells expressing CD69 compared with HVEM-(Fc*) and IgG1 treatment, respectively (Fig. 2A). Despite absent % CD69 induction on NK cells by HVEM-(Fc*), this Fc-disabled HVEM was a more potent inducer of IFN-γ in the presence of IL-2 from NK cells than HVEM-Fc (Fig. 2B) but not in the absence of IL-2 (Fig. S1A). This data suggested that HVEM-induced NK cell production of IFN-γ required IL-2 priming.

Figure 2: HVEM-(Fc*) activates NK cells and induces IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity.

(A-F) Purified NK cells from PBMC of healthy controls (n=9) were cultured with 20 µg/ml of human IgG (hIgG), HVEM-(Fc*) or HVEM-Fc in the presence of IL-2 (100 IU/ml) for 16 h. After 16 h, cells were examined by flow cytometry for surface expression of (A) CD69, (B) IFN-γ was quantitated from supernatants via ELISA, (C) viability was measured via 7-AAD staining, (D) CD16 cell surface expression was examined on CD56dimCD16+ NK cells. (E-F) To evaluate (E) spontaneous killing and (F) reverse ADCC activity, NK cells, cultured with 20 µg/ml hIgG, HVEM-(Fc*), or HVEM-Fc for 16 h, were further cocultured with target K562 cells or P815 cells, respectively, pre-labeled with fluorescent dye at effector (E) to target (T) ratio of 1:1 and 0.5:1 for 5 h. For reverse ADCC assays, each coculture was treated with 10 µg/ml of mouse IgG1 or anti-CD16 mAb. Dead targets cells were gated as 7-AAD+ cells. (G-J) PBMC from healthy controls (n=9 except panel H where n=5) were cultured with PBS or HVEM-(Fc*) (1µg/ml) for 44 h. Then, cell surface (G) CD69 expression on NK cells and (H) IFN-γ secretion in culture supernatants were determined via flow cytometry and ELISA respectively. Next, (I-J) PBMC were cultured with PBS or HVEM-(Fc*) for 44 h were washed, counted and further cocultured with pre-labeled K562 cells with fluorescent dye at an E to T ratio of 20:1 for 5 h in the presence of Golgi stop and anti-CD107a antibody. CD69 expression on NK cells and (H) IFN-γ secretion in culture supernatants were determined via flow cytometry and ELISA, respectively. Degranulation and cytotoxicity of NK cells were quantified by cell surface (I) CD107a expression on NK cells and (J) dead K562 target cells (7-AAD+Annexin-V+ cells) using flow cytometry. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Additionally, we observed increased NK cell death with HVEM-Fc versus HVEM-(Fc*) and hIgG1. This is likely attributable to NK fratricide via Fc-FcR binding (Fig. 2C) resulting in the observed reduction in CD16 (FcR) expression on NK cells after HVEM-Fc treatment (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we suspect that apparent IFN-γ secretion induced by CD16 and/or CD160 ligation of HVEM-Fc would be attenuated as compared to HVEM-Fc* (Fig. 2B) secondary to HVEM-Fc-induced fratricide; i.e. HVEM-Fc-FcR cross-linking likely occurs before these NK cells fully produced and/or released IFN-γ from HVEM-Fc engagement (Fig. 2C).

In contrast, HVEM-(Fc*) poorly engaged CD16 (Fig. 1B) and did not cause a reduction in CD16 expression (Fig. 2D) nor increased NK cell death (Fig. 2C). Thus, HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of NK cells significantly preserved NK cell viability and CD16 expression compared to HVEM-Fc and hIgG1 treatment (Fig. 2D).

Given the somewhat unexpected findings of increased IFN-γ production and decreased NK cell death with HVEM-(Fc*) versus HVEM-Fc, we then measured NK cell-induced cytotoxicity of K562 target cells. HVEM-(Fc*) enhanced NK cell-induced cytolysis of K562 cells (Fig. 2E). Surprisingly, HVEM-Fc caused significantly reduced spontaneous killing of K562 cells by NK cells (Fig. 2E) compared to HVEM-(Fc*) and hIgG1. We also tested the effect of HVEM-(Fc*) activated NK cells in a classic reverse antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay using the well-characterized P815 mouse mastocytoma cell line that abundantly expresses mouse CD16 (mouse Fc receptor) as described in the Methods section. HVEM-(Fc*) but not HVEM-Fc enhanced killing of P815 target cells via NK-mediated ADCC (Fig. 2F). In addition, HVEM-(Fc*)-induced spontaneous killing and ADCC did not require IL-2 priming (Fig. S1BC) as was required for IFN-γ production (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1A). IL-2 priming trended to, but did not significantly, enhance soluble HVEM induced spontaneous killing of K562 cells (p=0.074) nor reverse ADCC of P815 cells (p=0.21) (Fig.S1DE). These data demonstrate that HVEM-(Fc*) induces greater NK IFN-γ production in addition to spontaneous killing and ADCC as compared to HVEM-Fc. Taken together, we demonstrate that CD16 engagement with the Fc stalk of HVEM-Fc can interfere with the ability for a soluble HVEM reagent to augment NK effector function. This has important therapeutic applications. Therefore, we focused on characterizing HVEM-(Fc*) for all subsequent studies described below.

Several recent studies suggest that NK cell function can be modulated via antigen presenting cells such as monocytes, macrophages and DC (36–47). These cells also express HVEM receptors. Therefore, we tested the effect of soluble HVEM-(Fc*) on NK cell function when cocultured in the presence of the physiological complement of immune cells present in circulation. As shown in Fig. 2G-J in contrast to purified NK cells, soluble HVEM-(Fc*) treated PBMCs caused CD69 induction on NK cells (Fig. 2G). Similar to purified NK cells, soluble HVEM-(Fc*) significantly increased IFN-γ production (Fig. 2H) and increased lysis of K562 cells (Fig. 2I) in treated PBMCs. However, given the difficulty in characterizing the effector component of bulk PBMCs, a direct comparison cannot be made with purified NK cell data. We observed a mild increase in NK cell degranulation as assessed by surface CD107a expression (Fig. 2J) consistent with our direct cytotoxicity measurements (Fig. 2I). These data suggest that HVEM-(Fc*) stimulates NK cells intrinsically for IFN-γ production and spontaneous killing. However, CD69 and thus potentially other metrics of HVEM-(Fc*) activation may be further augmented by accessory cell(s). We pursued this line of investigation in Figures 4–6 below.

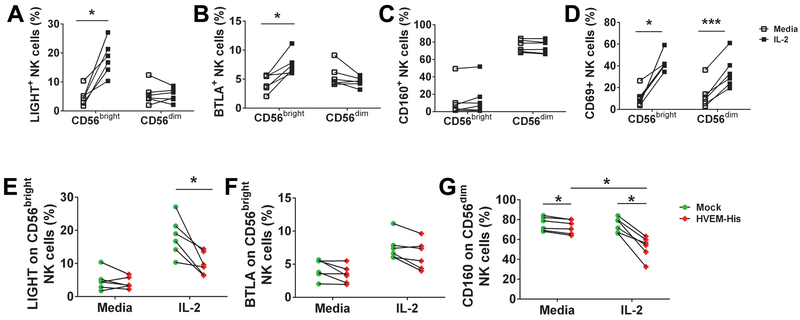

Figure 4: IL-2 priming upregulates LIGHT and BTLA expression on CD56bright NK cells and co-treatment with HVEM-His downregulates expression of LIGHT and CD160 on NK cells.

(A-D) Purified NK cells from healthy donor PBMC (n=6) were incubated with IL-2 (100 IU/ml) for 18 h and then cells were analyzed for (A) LIGHT, (B) BTLA, (C) CD160 or (D) CD69 expression on CD56bright vs. CD56dimCD16+ subsets of bulk NK cells using monoclonal antibodies (clones: T5-39, J168-540, 688327 and FN-5 respectively) by flow cytometry. The gating strategy for assessment of LIGHT, BTLA, CD160 and CD69 expression on CD56bright NK cells and CD56dim NK cells is shown in Fig. S2. (E-G) Purified NK cells from healthy donor PBMC (n=6) were incubated with media or plate bound HVEM-His (20-μg/ml, 20μl/well) in the presence or absence of IL-2 (100 IU/ml) for 18 h and then cells were analyzed for (E) LIGHT or (F) BTLA expression on CD56bright NK cells and (G) CD160 expression on CD56dim NK cells using monoclonal antibodies (clones: T5-39, J168-540, 688327 and FN-5 respectively) by flow cytometry. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

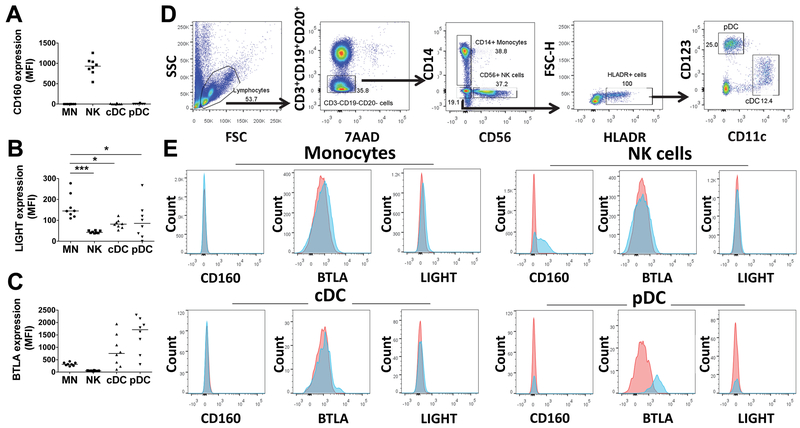

Figure 6: Monocytes express LIGHT greater than BTLA amongst potential HVEM receptors.

PBMCs from healthy donors (n=8) were stained for (A) CD160, (B) LIGHT or (C) BTLA and gated as shown in panel (D) for monocytes (CD14+/SSChigh), NK cells (CD14−/CD19−/CD3−/CD56+), conventional dendritic cells (cDC; CD3-CD14-HLA-DR+CD11c+), and plasmacytoid DC (pDC; CD3-CD14-HLA-DR+CD123+). Stained and washed cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Representative flow histograms show fluorescence intensity of receptors (CD160, BTLA, or LIGHT) on the X-axis for monocytes, NK cells, cDCs and pDCs. In each panel: red histogram = isotype control antibody staining; light blue histogram = receptor antibody staining.

HVEM-(Fc*) drives broad NK cytokine production that can be further augmented by IL-2 more so than other NK cell stimulating cytokines

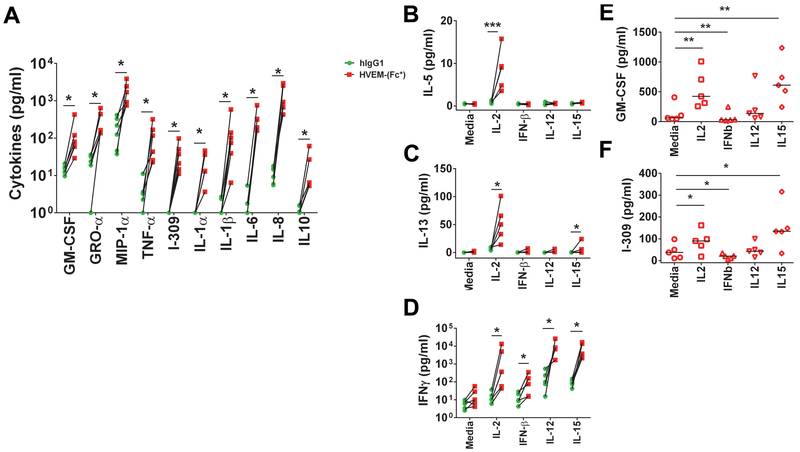

Previously, it was reported that CD160 signaling induces NK production of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MIP-1β, and lower amounts of IL-4 and IL-10 (12, 56). To more comprehensively evaluate the effects of soluble HVEM on cytokine production in a relatively unbiased manner, we preformed 65-plex cytokine protein array analysis using the Luminex platform. We repeated this analysis in the presence of media +/− the best characterized NK activating cytokines (IL-2, IFN-β, IL-12 and IL-15) in order to more fully capture the stimulating potential of soluble HVEM given IFN-γ production required the presence of IL-2 (Figs. 2B and S1A). We reasoned that other NK activating cytokines might be required for the production of additional cytokines similarly to what has been observed for NK cell IFN-γ production. HVEM-(Fc*) stimulated NK cells produced significant levels of GM-CSF, GRO-α, MIP-1α, TNF-α, I-309, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 without IL-2 priming compared to hIgG1 (Fig. 3A). While HVEM-(Fc*)-induced IL-5 and IL-13, similar to IFN-γ, required IL-2 priming of NK cells (Fig. 3B and C). During infection, type I IFN, IL-12, and IL-15 production promotes NK cell effector function (57, 58). When we evaluated the effect of these cytokines in 65plex Luminex-based assays, we found that only IFN-γ (Fig. 3D) production was significantly augmented by IFN-β, IL-12 and IL-15 vs. media alone and that HVEM-(Fc*)-induced production of other cytokines (e.g. I-309 and GM-CSF, Fig. 3EF) were distinctly affected by the presence of IFN-β, IL-12 and IL-15 (Fig. 3). IL-2 and IL-15 treatment significantly enhanced but IFN-β treatment significantly decreased HVEM-(Fc*)-induced GM-CSF and I-309 production (Fig 3E and F). Overall, we uncovered the production of additional cytokines (GM-CSF, GRO-α, MIP-1α, I-309, IL-1α and IL-1β) not previously published that were elaborated directly by soluble HVEM treatment, and did not require the presence of IL-2 or other NK activating cytokines. Moreover, we identified that IL-5, and IL-13 could be induced by HVEM-(Fc*) in the presence of IL-2, similarly to IFN-γ. These data highlight the potential therapeutic application of HVEM-(Fc*).

Figure 3: HVEM-(Fc*)-induced cytokines in NK cells.

NK cells purified from PBMC of healthy controls (n=5) were cultured in wells pre-coated with 20 µg/ml of human IgG1 (hIgG1) or HVEM-(Fc*) in the presence of (A) media only vs. (B-F) media, IL-2 (100 IU/ml), IFN-β (50 IU/ml), IL-12 (1 ng/ml), or IL-15 (5 ng/ml) for 16 h. Cell free supernatants were collected and analyzed for 65 cytokines via Luminex-based multiplex assay. Panels A-F shows the cytokines whose concentrations were significantly changed by HVEM-(Fc*) treatment compared to hIgG. Panel E-F shows the HVEM-(Fc*)-induced cytokines minus hIgG-induced cytokines. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

IL-2 priming upregulates LIGHT and BTLA but not CD160 expression on CD56bright NK cells

NK cells are divided into two major subtypes CD56dim and CD56bright. CD160 is mostly expressed on CD56dim NK cells, which make up the vast majority of circulating NK cells. In contrast, LIGHT and BTLA are expressed at low levels on both CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells (10, 35). IL-2 priming enhances HVEM-(Fc*)-stimulated cytokine production and might enhance it by increasing expression of NK cell HVEM receptors. Therefore, we determined whether IL-2 priming enhanced CD160, LIGHT, and/or BTLA (receptors of HVEM) expression on NK cells. As shown in Fig. 4 and S2, IL-2 priming of purified bulk NK cells upregulated expression of LIGHT (Fig. 4A) and BTLA (Fig. 4B) on CD56bright but not CD56dim NK cells. IL-2 priming of purified bulk NK cells did not change CD160 expression on either CD56dim or CD56bright subsets of NK cells (Fig. 4C). We confirmed IL-2 activation of purified bulk NK cells by demonstrating upregulation of CD69 expression on both subsets of NK cells (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, HVEM-His treatment of purified bulk NK cells reduced cell surface expression of LIGHT on CD56bright NK cells in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 4E) but did not change BTLA expression on CD56bright NK cells either in the presence and absence of IL-2 (Fig. 4F). CD160 expression on CD56dimCD16+ NK cells that was not affected by IL-2 priming but was reduced by HVEM-His treatment and HVEM-his-induced reduction in CD160 was further enhanced by the presence of IL-2 on CD56dimCD16+ NK cells (Fig. 4G). These data suggest that IL-2 priming distinctly enhanced the cell surface of expression HVEM receptors on different NK cell subsets and may enhance NK cell function differentially by HVEM activation.

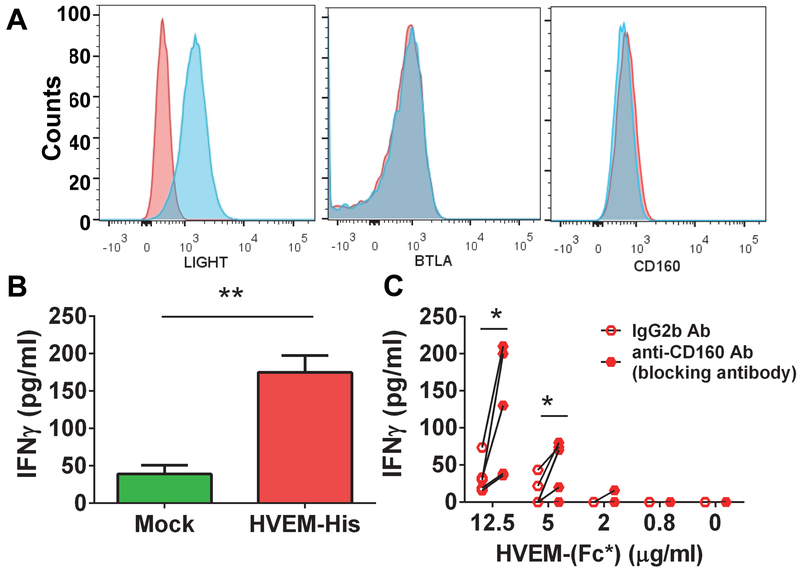

Since CD160 expression was not enhanced by soluble HVEM treatment of NK cells and BTLA was identified as an inhibitory receptor (10), we tested whether HVEM activates NK cells via LIGHT engagement. Human CD56dim NK cells only express CD160. However, both CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells express LIGHT at low levels (Fig. 4). To test the potential sole effect of HVEM via LIGHT, we made use of the KHYG1 NK cell line which we discovered only expressed LIGHT and not BTLA (Fig. 5A). The surface expression of CD160 on KHYG1 was similar to background isotype control (Fig. 5A). HVEM-His treatment of KHYG1 NK caused significant production of IFN-γ (Fig. 5B). Given this finding, we evaluated HVEM-induced activation via LIGHT on purified NK cells by incubating them with HVEM-(Fc*) in the presence of anti-CD160 blocking antibody (clone 688327; R&D). We found that HVEM-(Fc*) caused significant production of IFN-γ from NK cells after blocking of CD160 receptor (Fig. 5C). We hypothesize that CD160 blockade mediated enhancement of IFN-γ production from HVEM-(Fc)* treated NK cells resulted from more HVEM-(Fc)* binding of other HVEM ligands, such as LIGHT. The IL2 pre-treated NK cells express high levels of CD160 (the majority is localized on the CD56dim subset and the minority is localized on the CD56hi subset) and low levels of LIGHT and BTLA, which are mostly localized on the CD56hi subset. In the physiological condition (absence of CD160 blocking antibody), CD160 will compete with LIGHT, BTLA or other unknown ligand(s) on the NK cells to bind with plate bound HVEM-(Fc)*. Therefore most IFN-γ is likely released from NK cells by ligation of HVEM and CD160. On the other hand, in the presence of anti-CD160 blocking antibody, the other HVEM ligands, such as LIGHT, will have a greater likelihood to bind with HVEM-(Fc)*, and this binding might elicit greater IFN-γ production than CD160-HVEM binding. These data support the notion that HVEM may activate NK cells via LIGHT, in addition to CD160.

Figure 5: Ligation of HVEM-(Fc*) with CD160 and LIGHT can contribute to IFN-γ production from NK cells.

The KHYG1 NK cell line was analyzed for (A) LIGHT (left panel), BTLA (middle panel) and CD160 (right panel) expression using monoclonal antibodies (clones: T5-39, J168-540 and 688327 respectively) by flow cytometry. Representative flow histograms show fluorescence intensity of receptors on the X-axis. In each panel: red histogram = isotype control antibody staining; light blue histogram = receptor antibody staining. (B) KHYG1 cells were incubated with media or plate bound HVEM-His (20 μg/ml) for 18 h. After 18 h, cell free supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ production via ELISA. Mean ± SEM. shown (C) Purified NK cells from healthy controls (n=4), pre-incubated with isotype control antibody (mouse IgG2b) or anti-human CD160 blocking antibody at 20 μg/ml, were cultured with HVEM-(Fc*) pre-coated on a 384-well plate at the indicated concentration shown on the X-axis for 18 h. After 18 h, IFN-γ production was quantified from cell free supernatants via ELISA.

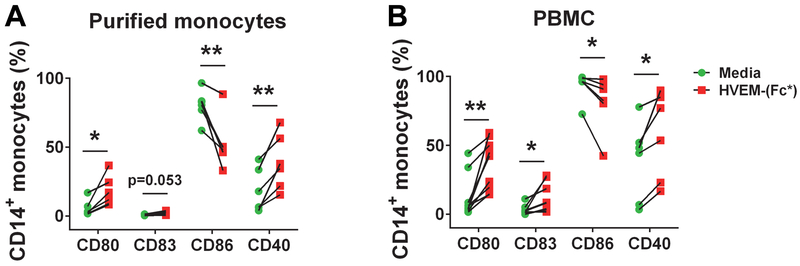

HVEM-(Fc*) promotes activation of monocytes

Several reports have demonstrated that monocytes and macrophages regulate NK cell effector function(s) (36, 38–41, 43–46). Monocytes also express receptors of HVEM (18, 34). Thus, we determined the level of expression of all three HVEM receptors on monocytes as a readily available cell type that may explain why PBMC cultures showed different results than isolated NK cells with respect to soluble HVEM treatment (Fig. 2). We found that monocytes expressed LIGHT and BTLA and there was no CD160 expression (Fig. 6). Among monocytes, NK cells and DCs, LIGHT expression was greatest on monocytes. Next, we tested whether HVEM-(Fc*) activated monocytes similarly to NK cells. Activation of monocytes was measured by surface expression of CD80, CD83, CD86 and CD40 (Fig. 7). Expression of activation markers, CD80, CD83, and CD40 but not CD86, was enhanced by HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of both purified monocytes (Fig. 7A) and flow-gated monocytes in PBMC cultures (Fig. 7B), consistent with Schwarz et. al. who also found upregulation of CD80, CD83 and CD40, but downregulation of CD86 in response to LPS (59). Similar to HVEM-(Fc*), HVEM-His also activated both monocytes and NK cells in PBMC cultures (Fig. S3) confirming that soluble HVEM could directly activate monocytes in addition to NK cells.

Figure 7: HVEM-(Fc*) promotes activation of monocytes.

Monocytes (A) purified by positive selection or (B) gated as CD3-CD14+/SSChigh cells within PBMC cultures from healthy donors (n=6) were incubated with media or HVEM-(Fc*) (1 μg/ml) for 22 h and subsequently analyzed for cell surface activation markers (CD80, CD83, CD86 and CD40) via flow cytometry. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

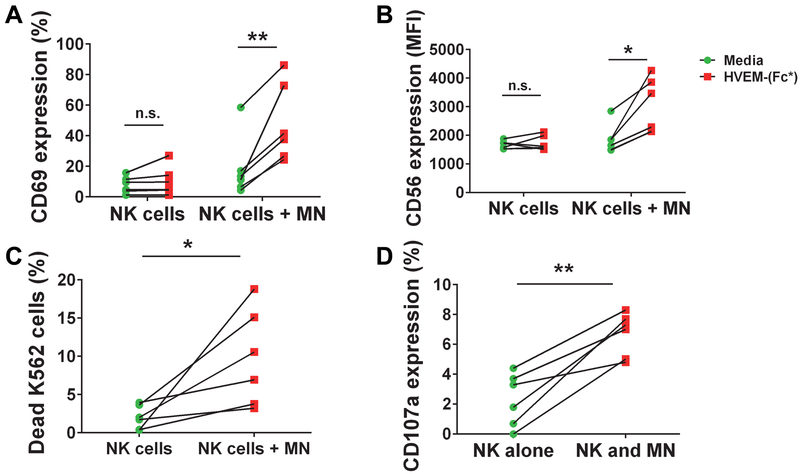

HVEM-(Fc*) promotes crosstalk between NK cells and monocytes

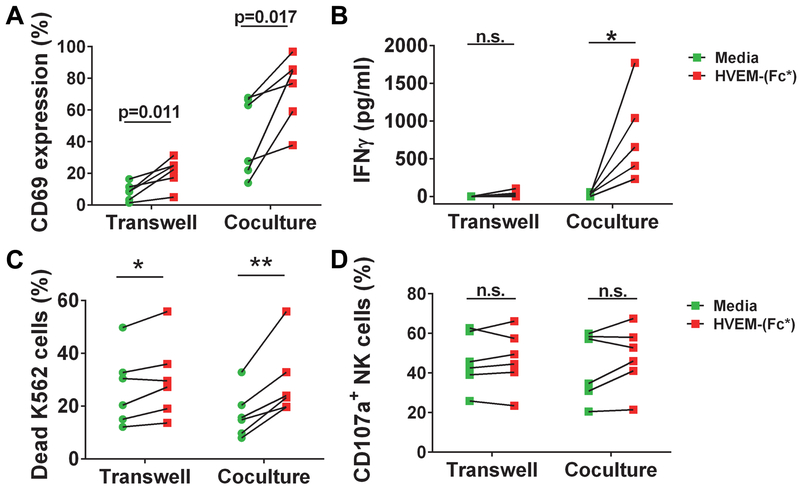

Next, we reasoned that since monocytes can modulate NK activity, were activated by HVEM-(Fc*) and NK cell activation was different in PBMC cultures vs. enriched NK cells incubated with HVEM-(Fc*), that monocytes may play a role in HVEM-(Fc*)-induced NK activation and subsequent effector functions. Thus, we compared purified NK cells cultured with and without purified monocytes in the presence or absence of HVEM-(Fc*). Activation of NK cells was quantified via cell surface CD69 expression, degranulation via CD107a, cytotoxicity to K562 target cells, and IFN-γ production.

When purified NK cells were cocultured with purified monocytes in the presence of HVEM-(Fc*), there was significant enhancement of CD69 (Fig. 8A) and CD56 (Fig. 8B) cell surface expression on the NK cells. There was also enhanced NK cell degranulation (increased cell surface expression of CD107a) and enhanced cytotoxicity towards K562 cells when NK cells were co-cultured with monocytes in the presence of HVEM-(Fc*) (Fig. 8C and D) compared to NK cells cultured with HVEM-(Fc*). These data demonstrate that monocytes can augment HVEM-(Fc*)-induced NK cell activation and effector function.

Figure 8: HVEM-(Fc*) promotes crosstalk between monocytes and NK cells, enhancing activation and cytotoxicity of NK cells.

(A-D) Purified NK cells from healthy donor PBMC (n=6) were cocultured without purified monocytes (MN) or with purified monocytes (NK cells + MN) at a ratio of 1:1 in the presence of media or HVEM-(Fc*) (1 μg/ml) for 44 h. (A-B) After 44 h, NK cells were analyzed for cell surface (A) CD69 and (B) CD56 expression by flow cytometry. After 44 h of HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of NK cells and NK cells + MN cocultures, pre-labeled K562 target cells were added at an E:T ratio of 1.5:1 in the presence of anti-CD107a Ab for 5h. HVEM-(Fc*) treatment enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity was evaluated as (C) percent dead 7-ADD+-Annexin V+ K562 cells (HVEM-induced minus media-induced) and (D) NK cell degranulation was estimated by cell surface CD107a expression (HVEM-induced minus media-induced) for both NK cells alone and the mixture of NK cells + monocytes as the effector cells. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

To test whether monocytes augment NK cell effector function via cell-cell contact or soluble mediators, NK cells were cocultured with monocytes in the presence or absence of HVEM-(Fc*) in a transwell tissue culture plate. Monocytes or NK cells were either cultured separately in the upper or lower chambers respectively separated by transmembrane or cultured together in the bottom chamber in a transwell culture plate. Transwell separation of purified NK cells and monocytes resulted in a slightly lower basal expression of CD69 (Fig. 9A), however, this was not statistically significant. Otherwise, HVEM-(Fc*) similarly induced CD69 expression in NK cell and monocyte transwell separated cultures as compared to culturing both cell types together in the bottom chamber (Fig. 9A). In contrast, we observed that HVEM-(Fc*)-induced IFN-γ production was enhanced by coculture of NK and monocytes as compared to separation of these cells by transwell membrane (Fig. 9B). Additionally, there was more significant HVEM-(Fc*)-induced K562 cytotoxicity in cocultures of NK and monocytes as compared to separation of these cells by transwell membrane (Fig. 9C). This mild difference in cytotoxicity was not observed in NK cell degranulation as measured by CD107a expression (Fig. 9D). HVEM-(Fc*)-induced activation of monocytes in transwell cocultures was assessed by cell surface expression of CD80, CD86, CD83, and CD40 (Fig. S4). Similar to the HVEM-(Fc*) treated purified monocytes (Fig. 7), there was significant enhancement of CD80, CD83, CD40 but not CD86 (Fig. S4) expression on monocytes in the transwell cocultures. Taken together, these transwell experiments indicated that HVEM-(Fc*) activation of NK via NK-monocyte crosstalk required cell-cell contact mechanism(s) for maximal enhancement of IFN-γ production and potentially mild enhancement of spontaneous killing.

Figure 9: HVEM-(Fc*)-induced IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity of NK cells is enhanced by monocyte-NK cell-cell contact.

(A-D) NK cells and monocytes were purified from PBMC by negative selection and positive selection respectively. The purified NK cells and monocytes were either cocultured in a flat bottom well or separately cultured in a transwell in the presence or absence of HVEM-(Fc*) (1 μg/ml) for 44 h. After 44 h, cell surface (A) CD69 expression on NK cells was measured by flow cytometry and (B) IFN-γ production in cell free supernatants was quantified via ELISA. (C-D) Cells were treated as above with HVEM-(Fc*) for 44 h and subsequently cocultured with pre-labeled K562 cells in the presence of anti-CD107a Ab for 5 h. (C) Dead 7AAD+Annexin-V+ K562 cells were quantified and (D) NK cell CD107a expression was quantified, all by flow cytometry.

Discussion:

NK cells play a key role in the protection from pathogens and cancer. NK cell-mediated effector function depends on the type and number of receptor/ligand interactions occurring between NK cells and their targets. In this context, it has been shown that CD160 drives NK cell activation, cytokine production and cytotoxicity via engagement with HLA-C (12) and HVEM (10, 16, 18, 49). Here, we have shown that HVEM conjugated to the wild type sequence of Fc (HVEM-Fc) activates NK cells; however, the Fc portion can cause interaction and activation of other Fc-receptor expressing immune cells via Fc-Fc receptor ligation in addition to HVEM (Fig. 1, 2). This is notable given this form of HVEM-Fc is the reagent readily available “off-the-shelf” from multiple vendors including BioLegend®, R&D Systems™, Sigma-Aldrich®, SBH Sciences™, AB Biosciences, BPS Bioscience, Enzo, PromoCell, Tonbo biosciences, GenScript®, G&P Biosciences® and others. We designed and evaluated a soluble Fc-disabled HVEM to interrogate the specific function of HVEM-mediated NK cell responses and provide an alternative reagent for potential therapeutic application. To do this, we fused the HVEM extracellular domain to a mutant Fc stalk that poorly binds the Fc receptor “HVEM-(Fc*)”. HVEM-(Fc*) binding to CD160 on primary NK cells resulted in increased inflammatory cytokine expression, degranulation (enhanced CD107a expression), and cytolysis by NK cells as compared to wild-type HVEM-Fc.

We have also shown for the first time that HVEM induces a broader array of cytokines than previously demonstrated which occurred in both IL-2-dependent and -independent manners. Previously, it has been reported that engaging CD160 via its agonist monoclonal anti-CD160 antibody clone CL1R2 (CL1R2 Ab) or HLA-C binding on peripheral blood NK cells drove large amount of IFN-γ, IL-6 and TNF-α, (12) as well as IL-8 and MIP-1β, but marginal amounts of IL-4 or IL-10 (56). The same authors reported their unpublished data that IL-1β, IL-5, IL-7, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17, G-CSF and MCP-1 production was not detectable by NK cells via CL1R2 Ab or HLA-C (56). We have shown that HVEM-(Fc*) treatment of NK cells can drive pro-inflammatory cytokines including GM-CSF, GRO-α, MIP-1α, TNF-α, I-309, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 that didn’t require IL-2 priming and IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-13 required IL-2 priming. We did not uncover any significant additional synergy of HVEM-(Fc*) with type 1 IFN (IFN-β), IL-12 or IL-15 beyond what we observed for IL-2 in 65-plex Luminex-based cytokine quantitation. It is plausible that previous reports of undetectable levels of several cytokines reported is due to non-priming of NK cells with IL-2.

The expression of HVEM ligands on NK cells can be regulated by stimulation with cytokines and tumor cells (60, 61). For example, long-term stimulation of NK cells with high concentration of IL-2 or IL-15 downregulates the CD160-GPI isoform expression and simultaneously upregulates the CD160 transmembrane (CD160-TM) isoform expression (61). Giustiniani et. al.’s (61) data suggests complex CD160 signaling specific to NK cells. Specifically, the GPI isoform lacks any intracellular domain. In contrast, the CD160-TM possesses an intracellular domain that induces phosphotyrosine dependent Erk activation signaling via Src-family kinase p56lck. This data suggests that cytokines can modulate the expression of CD160 isoforms via chronic stimulation. Similarly, stimulation of NK cells with K562 tumor cells and IL-2 or IL-15 upregulates LIGHT expression, another HVEM interacting receptor implicated in the enhancement of antitumor responses (60). Together, these data support the notion that stimulated NK cells become uniquely receptive to HVEM engagement. Secretion of cytokines via HVEM activated NK cells (novel members identified herein) might further regulate the cascade of events leading to a specific and efficient recruitment of these receptors for their respective signaling pathways and the function(s) of NK cells and other immune cells. In our study, we found IL-2 induced expression of LIGHT and BTLA only on the CD56bright NK cells (Fig. 4AB). CD56bright NK cells are mainly cytokine producers; more so found in lymphoid organs and considered to be precursors of CD56dim NK cells, the latter mainly perform cytotoxicity in addition to cytokine production. Holmes et al (60) have shown that tumor activated NK cells enhanced the expression of LIGHT in human NK cells and is linked to the initiation of adaptive immunity via LIGHT-mediated NK–DC cross talk. In this context, the modulation of LIGHT and BTLA expression on CD56bright NK cells could regulate NK cell activity and subsequently participate in the shaping of adaptive immune responses. Overall, these findings support a mechanism for directing specific NK action within the HVEM-LIGHT-BTLA-CD160-LTbeta signaling network. This work serves as a basis for better understanding and ultimately adjusting immune responses for therapeutic benefit. When pursuing this application, it will be important to test in future studies additional potential mechanisms that might govern NK cell activation via the HVEM-LIGHT-BTLA-CD160-LTbeta signaling network including potentially counterregulatory mechanisms.

Interestingly, co-stimulation of bulk NK cells with HVEM-(Fc*) and IL-2 downregulates expression of CD160 and LIGHT on CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells, respectively (Fig. 4EG). This data suggests that IL-2 priming modulates the expression of HVEM receptors distinctly on the two subsets of NK cells and crosstalk may occur between both cell types, resulting in a potentially additional layer of complexity in HVEM-stimulated NK responses.

We reasoned that the Fc portion of HVEM-Fc found in commercially available reagents could contribute to effects beyond HVEM receptor engagement on innate immune cells (i.e. via Fc receptor engagement). Recent literature suggests that NK cells also interact with other immune cells (e.g. monocytes, macrophages, or DC) for optimal cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and control of virally infected or tumor cells. It has been shown that both TLR ligands and pathogens can promote crosstalk between monocytes/macrophages and NK cells via cell-cell contact and/or cytokine (36). We found that HVEM-(Fc*) activated monocytes and enhanced expression of activation markers CD40, CD80, and CD83 but not CD86 (Fig. 7). Our finding is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that LPS, similar to HVEM-(Fc*), enhanced the expression of activation markers CD40, CD80, CD83 but not the expression of CD86 (59, 62). Recent human and mouse studies have shown that CD80 and CD86 have differential roles in different disease states (63–66). However, the significance of CD80 upregulation and CD86 downregulation on monocytes for subsequent immune responses is unknown.

We have also shown that HVEM-(Fc*)-induced NK cell cytotoxicity was enhanced when NK cells were cocultured with monocytes and is reduced when NK cells were separated by monocytes in a transwell coculture system. Likewise, HVEM-(Fc*)-induced IFN-γ production in NK cell plus monocyte cocultures was significantly reduced when monocytes were separated by NK cells in transwells. Our data shows that HVEM-(Fc*) promotes crosstalk between NK cells and monocytes in vitro that requires cell-cell contact for maximal enhancement of IFN-γ secretion and optimum killing of K562 target cells.

Here, we have reported for the first time a reagent HVEM-(Fc*) (which negligibly binds to the Fc receptor) activates monocytes and promotes crosstalk between NK cells and monocytes largely via cell-cell contact. Based on the expression levels of HVEM receptors on monocytes, we propose that it is most likely that HVEM-(Fc*) engages LIGHT for the activation of monocytes (vs. CD160 on NK cells), which subsequently may provide for enhanced overall NK function.

In conclusion, we report here that HVEM-(Fc*) activates NK cells and monocytes and promotes NK cell and monocyte crosstalk for enhanced activation of NK cells and NK cell cytotoxicity. We have also shown that the Fc portion of HVEM-Fc but not HVEM-(Fc*) can interfere with augmenting NK function by reducing CD16 expression on NK cells and NK cell cytotoxicity via Fc-Fc receptor engagement. Our work supports the potential use of soluble HVEM as a therapeutic agent by eliminating the potentially counteracting effects of the Fc portion of conventional HVEM-Fc fusion proteins, consistent with Boice et. al. (22).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Skin Diseases Research Center P30AR039750 (DLP), VA Merit Award IBX002719A (DLP), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Developmental Award (DLP) and by the Creative and Novel Ideas in HIV Research (CNIHR) Program through a supplement to the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center For AIDS Research funding (P30 AI027767, DLP). This funding was made possible by collaborative efforts of the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the International AIDS Society. These contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or other funding sources.

Abbreviations used in this article:

- HVEM

Herpes Simplex Virus Entry Mediator

- TNFR

TNF receptor

- LIGHT

Homologous to lymphotoxins, shows inducible expression, and competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed by T-lymphocytes

- BTLA

B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator

- LT- α

Lymphotoxin (LT)-α

- NK cell

Natural Killer cell

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Mavilio D, and Kottilil S. 2005. NK cells in HIV infection: paradigm for protection or targets for ambush. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Zaghi E, Di Vito C, and Mavilio D. 2017. Natural killer cells in HIV-1 infection and therapy. AIDS 31: 2317–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittari G, Vago L, Festuccia M, Bonini C, Mudawi D, Giaccone L, and Bruno B. 2017. Restoring Natural Killer Cell Immunity against Multiple Myeloma in the Era of New Drugs. Front Immunol 8: 1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pahl J, and Cerwenka A. 2017. Tricking the balance: NK cells in anti-cancer immunity. Immunobiology 222: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang F, Xiao W, and Tian Z. 2017. NK cell-based immunotherapy for cancer. Semin Immunol 31: 37–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiza H, Leca G, Mansur IG, Schiavon V, Boumsell L, and Bensussan A. 1993. A novel 80-kD cell surface structure identifies human circulating lymphocytes with natural killer activity. J Exp Med 178: 1121–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anumanthan A, Bensussan A, Boumsell L, Christ AD, Blumberg RS, Voss SD, Patel AT, Robertson MJ, Nadler LM, and Freeman GJ. 1998. Cloning of BY55, a novel Ig superfamily member expressed on NK cells, CTL, and intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol 161: 2780–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan CL, Peluso MJ, Drijvers JM, Mera CM, Grande SM, Brown KE, Godec J, Freeman GJ and Sharpe AH. 2018. CD160 Stimulates CD8+ T Cell Responses and Is Required for Optimal Protective Immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. ImmunoHorizons 2: 238–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GeneAtlas U133A, gcrma. URL: http://ds.biogps.org/?dataset=GSE1133&gene=11126.

- 10.Sedy JR, Bjordahl RL, Bekiaris V, Macauley MG, Ware BC, Norris PS, Lurain NS, Benedict CA, and Ware CF. 2013. CD160 activation by herpesvirus entry mediator augments inflammatory cytokine production and cytolytic function by NK cells. J Immunol 191: 828–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal S, Marquet J, Freeman GJ, Tawab A, Bouteiller PL, Roth P, Bolton W, Ogg G, Boumsell L, and Bensussan A. 1999. Cutting edge: MHC class I triggering by a novel cell surface ligand costimulates proliferation of activated human T cells. J Immunol 162: 1223–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barakonyi A, Rabot M, Marie-Cardine A, Aguerre-Girr M, Polgar B, Schiavon V, Bensussan A, and Le Bouteiller P. 2004. Cutting edge: engagement of CD160 by its HLA-C physiological ligand triggers a unique cytokine profile secretion in the cytotoxic peripheral blood NK cell subset. J Immunol 173: 5349–5354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu TC, Brown NK, Kim TJ, Wroblewska J, Yang X, Guo X, Lee SH, Kumar V, Lee KM, and Fu YX. 2015. CD160 is essential for NK-mediated IFN-gamma production. J Exp Med 212: 415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedy J, Bekiaris V, and Ware CF. 2014. Tumor necrosis factor superfamily in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a016279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware CF, and Sedy JR. 2011. TNF Superfamily Networks: bidirectional and interference pathways of the herpesvirus entry mediator (TNFSF14). Curr Opin Immunol 23: 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.del Rio ML, Lucas CL, Buhler L, Rayat G, and Rodriguez-Barbosa JI. 2010. HVEM/LIGHT/BTLA/CD160 cosignaling pathways as targets for immune regulation. J Leukoc Biol 87: 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shui JW, and Kronenberg M. 2013. HVEM: An unusual TNF receptor family member important for mucosal innate immune responses to microbes. Gut Microbes 4: 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai G, and Freeman GJ. 2009. The CD160, BTLA, LIGHT/HVEM pathway: a bidirectional switch regulating T-cell activation. Immunol Rev 229: 244–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan Z, Yu P, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fu ML, Liu W, Sun Y, and Fu YX. 2006. NK-cell activation by LIGHT triggers tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell immunity to reject established tumors. Blood 107: 1342–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heo SK, Yoon MA, Lee SC, Ju SA, Choi JH, Suh PG, Kwon BS, and Kim BS. 2007. HVEM signaling in monocytes is mediated by intracellular calcium mobilization. J Immunol 179: 6305–6310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon T, and Bromberg JS. 2016. BTLA(+) Dendritic Cells: The Regulatory T Cell Force Awakens. Immunity 45: 956–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boice M, Salloum D, Mourcin F, Sanghvi V, Amin R, Oricchio E, Jiang M, Mottok A, Denis-Lagache N, Ciriello G, Tam W, Teruya-Feldstein J, de Stanchina E, Chan WC, Malek SN, Ennishi D, Brentjens RJ, Gascoyne RD, Cogne M, Tarte K, and Wendel HG. 2016. Loss of the HVEM Tumor Suppressor in Lymphoma and Restoration by Modified CAR-T Cells. Cell 167: 405–418 e413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasero C, Speiser DE, Derre L, and Olive D. 2012. The HVEM network: new directions in targeting novel costimulatory/co-inhibitory molecules for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol 12: 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg MW, Cheung TC, and Ware CF. 2011. The signaling networks of the herpesvirus entry mediator (TNFRSF14) in immune regulation. Immunol Rev 244: 169–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shui JW, Larange A, Kim G, Vela JL, Zahner S, Cheroutre H, and Kronenberg M. 2012. HVEM signalling at mucosal barriers provides host defence against pathogenic bacteria. Nature 488: 222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauri DN, Ebner R, Montgomery RI, Kochel KD, Cheung TC, Yu GL, Ruben S, Murphy M, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Spear PG, and Ware CF. 1998. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity 8: 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung TC, Humphreys IR, Potter KG, Norris PS, Shumway HM, Tran BR, Patterson G, Jean-Jacques R, Yoon M, Spear PG, Murphy KM, Lurain NS, Benedict CA, and Ware CF. 2005. Evolutionarily divergent herpesviruses modulate T cell activation by targeting the herpesvirus entry mediator cosignaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 13218–13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armour KL, Clark MR, Hadley AG, and Williamson LM. 1999. Recombinant human IgG molecules lacking Fcgamma receptor I binding and monocyte triggering activities. Eur J Immunol 29: 2613–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granger SW, and Rickert S. 2003. LIGHT-HVEM signaling and the regulation of T cell-mediated immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 14: 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhai Y, Guo R, Hsu TL, Yu GL, Ni J, Kwon BS, Jiang GW, Lu J, Tan J, Ugustus M, Carter K, Rojas L, Zhu F, Lincoln C, Endress G, Xing L, Wang S, Oh KO, Gentz R, Ruben S, Lippman ME, Hsieh SL, and Yang D. 1998. LIGHT, a novel ligand for lymphotoxin beta receptor and TR2/HVEM induces apoptosis and suppresses in vivo tumor formation via gene transfer. J Clin Invest 102: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamada K, Shimozaki K, Chapoval AI, Zhai Y, Su J, Chen SF, Hsieh SL, Nagata S, Ni J, and Chen L. 2000. LIGHT, a TNF-like molecule, costimulates T cell proliferation and is required for dendritic cell-mediated allogeneic T cell response. J Immunol 164: 4105–4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duhen T, Pasero C, Mallet F, Barbarat B, Olive D, and Costello RT. 2004. LIGHT costimulates CD40 triggering and induces immunoglobulin secretion; a novel key partner in T cell-dependent B cell terminal differentiation. Eur J Immunol 34: 3534–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heo SK, Ju SA, Lee SC, Park SM, Choe SY, Kwon B, Kwon BS, and Kim BS. 2006. LIGHT enhances the bactericidal activity of human monocytes and neutrophils via HVEM. J Leukoc Biol 79: 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy KM, Nelson CA, and Sedy JR. 2006. Balancing co-stimulation and inhibition with BTLA and HVEM. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohavy O, Zhou J, Ware CF, and Targan SR. 2005. LIGHT is constitutively expressed on T and NK cells in the human gut and can be induced by CD2-mediated signaling. J Immunol 174: 646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michel T, Hentges F, and Zimmer J. 2012. Consequences of the crosstalk between monocytes/macrophages and natural killer cells. Front Immunol 3: 403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kloss V, Grunvogel O, Wabnitz G, Eigenbrod T, Ehrhardt S, Lasitschka F, Lohmann V, and Dalpke AH. 2017. Interaction and Mutual Activation of Different Innate Immune Cells Is Necessary to Kill and Clear Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Cells. Front Immunol 8: 1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalbeth N, Gundle R, Davies RJ, Lee YC, McMichael AJ, and Callan MF. 2004. CD56bright NK cells are enriched at inflammatory sites and can engage with monocytes in a reciprocal program of activation. J Immunol 173: 6418–6426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serti E, Werner JM, Chattergoon M, Cox AL, Lohmann V, and Rehermann B. 2014. Monocytes activate natural killer cells via inflammasome-induced interleukin 18 in response to hepatitis C virus replication. Gastroenterology 147: 209–220 e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baratin M, Roetynck S, Lepolard C, Falk C, Sawadogo S, Uematsu S, Akira S, Ryffel B, Tiraby JG, Alexopoulou L, Kirschning CJ, Gysin J, Vivier E, and Ugolini S. 2005. Natural killer cell and macrophage cooperation in MyD88-dependent innate responses to Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 14747–14752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatnagar N, Ahmad F, Hong HS, Eberhard J, Lu IN, Ballmaier M, Schmidt RE, Jacobs R, and Meyer-Olson D. 2014. FcgammaRIII (CD16)-mediated ADCC by NK cells is regulated by monocytes and FcgammaRII (CD32). Eur J Immunol 44: 3368–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, and Trinchieri G. 2002. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med 195: 327–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welte S, Kuttruff S, Waldhauer I, and Steinle A. 2006. Mutual activation of natural killer cells and monocytes mediated by NKp80-AICL interaction. Nat Immunol 7: 1334–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kloss M, Decker P, Baltz KM, Baessler T, Jung G, Rammensee HG, Steinle A, Krusch M, and Salih HR. 2008. Interaction of monocytes with NK cells upon Toll-like receptor-induced expression of the NKG2D ligand MICA. J Immunol 181: 6711–6719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knorr M, Munzel T, and Wenzel P. 2014. Interplay of NK cells and monocytes in vascular inflammation and myocardial infarction. Front Physiol 5: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez-Alvaro I, Dominguez-Jimenez C, Ortiz AM, Nunez-Gonzalez V, Roda-Navarro P, Fernandez-Ruiz E, Sancho D, and Sanchez-Madrid F. 2006. Interleukin-15 and interferon-gamma participate in the cross-talk between natural killer and monocytic cells required for tumour necrosis factor production. Arthritis Res Ther 8: R88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcenaro E, Carlomagno S, Pesce S, Moretta A, and Sivori S. 2012. NK/DC crosstalk in anti-viral response. Adv Exp Med Biol 946: 295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Human HVEM ECD (Extracellular Domain) Protein, Fc-fusion, ADCC-KO Mutant, Recombinant. Product ID: HVEM-FcKO (SKU#: FCL0096K). URL: https://www.gnpbio.com/index.php/products/1050/11/recombinant-proteins-enzymes/human-hvem-ecd-extracellular-domain-protein-fc-fusion-adcc-ko-mutant-recombinant-detail.

- 49.El-Far M, Pellerin C, Pilote L, Fortin JF, Lessard IA, Peretz Y, Wardrop E, Salois P, Bethell RC, Cordingley MG, and Kukolj G. 2014. CD160 isoforms and regulation of CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses. J Transl Med 12: 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brissette-Storkus C, Appasamy PM, Hayes LA, Kaufman CL, Ildstad ST, and Chambers WH. 1995. Characterization and comparison of the lytic function of NKR-P1+ and NKR-P1-rat natural killer cell clones established from NKR-P1bright/TCR alpha beta-cell lines. Nat Immun 14: 98–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrop JA, McDonnell PC, Brigham-Burke M, Lyn SD, Minton J, Tan KB, Dede K, Spampanato J, Silverman C, Hensley P, DiPrinzio R, Emery JG, Deen K, Eichman C, Chabot-Fletcher M, Truneh A, and Young PR. 1998. Herpesvirus entry mediator ligand (HVEM-L), a novel ligand for HVEM/TR2, stimulates proliferation of T cells and inhibits HT29 cell growth. J Biol Chem 273: 27548–27556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheung TC, Steinberg MW, Oborne LM, Macauley MG, Fukuyama S, Sanjo H, D’Souza C, Norris PS, Pfeffer K, Murphy KM, Kronenberg M, Spear PG, and Ware CF. 2009. Unconventional ligand activation of herpesvirus entry mediator signals cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 6244–6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morel Y, Schiano de Colella JM, Harrop J, Deen KC, Holmes SD, Wattam TA, Khandekar SS, Truneh A, Sweet RW, Gastaut JA, Olive D, and Costello RT. 2000. Reciprocal expression of the TNF family receptor herpes virus entry mediator and its ligand LIGHT on activated T cells: LIGHT down-regulates its own receptor. J Immunol 165: 4397–4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wessels U, Poehler A, Moheysen-Zadeh M, Zadak M, Staack RF, Umana P, Heinrich J, and Stubenrauch K. 2016. Detection of antidrug antibodies against human therapeutic antibodies lacking Fc-effector functions by usage of soluble Fcgamma receptor I. Bioanalysis 8: 2135–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armour KL, van de Winkel JG, Williamson LM, and Clark MR. 2003. Differential binding to human FcgammaRIIa and FcgammaRIIb receptors by human IgG wildtype and mutant antibodies. Mol Immunol 40: 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Bouteiller P, Tabiasco J, Polgar B, Kozma N, Giustiniani J, Siewiera J, Berrebi A, Aguerre-Girr M, Bensussan A, and Jabrane-Ferrat N. 2011. CD160: a unique activating NK cell receptor. Immunol Lett 138: 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen KB, Salazar-Mather TP, Dalod MY, Van Deusen JB, Wei XQ, Liew FY, Caligiuri MA, Durbin JE, and Biron CA. 2002. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol 169: 4279–4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stetson DB, and Medzhitov R. 2006. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25: 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwarz H, Gornicec J, Neuper T, Parigiani MA, Wallner M, Duschl A, and Horejs-Hoeck J. 2017. Biological Activity of Masked Endotoxin. Sci Rep 7: 44750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holmes TD, Wilson EB, Black EV, Benest AV, Vaz C, Tan B, Tanavde VM, and Cook GP. 2014. Licensed human natural killer cells aid dendritic cell maturation via TNFSF14/LIGHT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E5688–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giustiniani J, Bensussan A, and Marie-Cardine A. 2009. Identification and characterization of a transmembrane isoform of CD160 (CD160-TM), a unique activating receptor selectively expressed upon human NK cell activation. J Immunol 182: 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farina C, Theil D, Semlinger B, Hohlfeld R, and Meinl E. 2004. Distinct responses of monocytes to Toll-like receptor ligands and inflammatory cytokines. Int Immunol 16: 799–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nolan A, Kobayashi H, Naveed B, Kelly A, Hoshino Y, Hoshino S, Karulf MR, Rom WN, Weiden MD, and Gold JA. 2009. Differential role for CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the innate immune response in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 4: e6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balbo P, Silvestri M, Rossi GA, Crimi E, and Burastero SE. 2001. Differential role of CD80 and CD86 on alveolar macrophages in the presentation of allergen to T lymphocytes in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 31: 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okano M, Azuma M, Yoshino T, Hattori H, Nakada M, Satoskar AR, Harn DA Jr., Nakayama E, Akagi T, and Nishizaki K. 2001. Differential role of CD80 and CD86 molecules in the induction and the effector phases of allergic rhinitis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1501–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Subauste CS, de Waal Malefyt R, and Fuh F. 1998. Role of CD80 (B7.1) and CD86 (B7.2) in the immune response to an intracellular pathogen. J Immunol 160: 1831–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.