Abstract

Purpose

Rapid yet useful methods are needed to screen for dietary behaviors in clinical settings. We tested the feasibility and reliability of a pediatric adapted liking survey (PALS) to screen for dietary behaviors and suggest tailored caries and obesity prevention messages.

Methods

In an observational study, children admitted to a pediatric emergency department (PED) for nonurgent care were approached to complete the PALS (33 foods, 4 nonfoods including brushing teeth). Measured height/weight were used for body mass index (BMI) percentile determination. Feasibility was assessed by response rate and PALS completion time. Reliability was assessed by internal consistency of food groups and test-retest reliability for PED-home reported PALS.

Results

PALS was completed by 144 children (96% of approached) − 54% male (average age = 11 ± 3 years) with diversity in family income (43% publicly insured), race/ethnicity (15% African American, 33% Hispanic, 44% Caucasian) and adiposity (3% underweight, 50% normal, 31% overweight, 17% obese, 8% extremely obese). The average completion time was 3: 52 min, and conceptual food groups had reasonable internal reliability. From 57% (n = 82) with PED-home completion, PALS had a good/excellent test-retest reliability. Relative preferences for sweets versus brushing teeth identified unique groups of children for tailored prevention messages (high sweet/brushing preference, sweets > brushing, brushing > sweets). Females with higher adiposity reported significantly greater preference for sweet/high-fat foods, independently of demographic variables; the relationship was nonsignificant in males and with the other food groups.

Conclusion

The PALS appears to be a fast, feasible and reliable dietary screener in a clinical setting to assist in forming tailored diet-related messages for dental caries and obesity prevention.

Key Words: Dietary assessment, Dietary screener, Caries, Caries prevention, Obesity prevention, Sweet preference, Children, Test-retest reliability

Introduction

Dental caries and obesity, prevalent chronic diseases, are associated in multiple studies [Hayden et al., 2013] and share multifactorial causes. The World Health Organization estimates 60–90% of school children have caries [World Health Organization, 2012], with rates highest in poorer populations. Likewise, the worldwide prevalence of overweight/obesity in children ranges from 22 to 24% [Ng et al., 2014]. In the USA, 17% of 2- to 19-year-olds are obese and 5.8% extremely obese, newly defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥120% of the 95th percentile [Ogden et al., 2016]. Advocates support primary prevention of these chronic diseases in dental settings [Yuan et al., 2012] with family-centered and tailored techniques for limiting sugar consumption and improving diet healthiness. Dental clinics offer opportune locations in the health system to screen for obesity, promote healthy behaviors, and connect families with specialized care [Garcia et al., 2017].

Dental caries and obesity prevention is challenged by biological, developmental and environmental forces that support children's preference for sweets. Although we are born liking sweet, risk of dental caries has been linked to genetic variants in sweet (GLUT2, TAS1R2 [Izakovicova Holla et al., 2015]) and bitter (TAS2R38 [Yildiz et al., 2016]) taste receptors that influence sweet sensitivity and preference. Furthermore, sweet preference increases during times of physical growth, fueled with readily available highly sweet foods [Mennella et al., 2016]. It is of interest how to assess food preferences as a tool for dental caries and obesity prevention efforts.

Accurate and efficient screening tools are needed in clinical settings to assess dietary behaviors linked to risk of caries [Arheiam et al., 2016] and obesity prevention efforts [Garcia et al., 2017]. Most dietary screeners use recall of the past day's intake (e.g., 24-h recall) or usual food/beverage consumption frequency [NCCOR, 2017]. These instruments require recall of behavior, which is cognitively challenging [Johnson, 1983], time intensive, and likely biased by misreporting, particularly among heavier children [Bel-Serrat et al., 2016]. Alternatively, asking about food/beverage preference is cognitively simpler, quicker and often less biased. Reported food preference correlates with reported intake [Lanfer et al., 2012; Sharafi et al., 2015; Tuorila et al., 2008] and biomarkers of dietary intake and/or adiposity in children [Sharafi et al., 2015] and adults [Pallister et al., 2015; Sharafi et al., 2016]. Elevated preference for sweet foods is observed among children who have greater adiposity [Lanfer et al., 2012] and caries [Maciel et al., 2001].

The aim of the present study was to assess the feasibility, reliability and utility of the pediatric adapted liking survey (PALS) [Sharafi et al., 2015] to screen for dietary behaviors in children in a clinical setting for caries and obesity prevention.

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

This observation study was conducted in the Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) at Connecticut Children's Medical Center in Hartford, CT, USA, and approved by their Institutional Review Board. A convenience sample of child/parent dyads presenting to the PED for nonurgent care was recruited. A research assistant approached parents if children were between 5 and 17 years old. Children were not included if non-English speaking, critically ill, deemed too sick by the physician, or presenting for behavioral or psychiatric illnesses (including eating disorders). Informed, written consent/assent was obtained as well as demographic information (age, race, sex, insurance status [categorized as self-pay, public or private], zip code, and phone number) and history of chronic medical problems. Prior to administering PALS in the patient's room, the child's height/weight were measured for calculating BMI and then, sex and age-specific percentiles based on the Centers for Disease Control growth charts [Ogden et al., 2016]. At the end of the visit, parents were provided a stamped and addressed envelope containing a blank PALS, with request to complete the PALS at home when the child was well. Child/parent dyads who returned the home survey received a USD 10 gift card.

Pediatric-Adapted Liking Survey

Participants reported their level of liking/disliking of items (shown as pictures and words) using a horizontal visual analog scale with 5 faces. Measured by technicians from the scale center to the participant's marking (±100 max./min.), labeled left to right, as “he/she loves it” (from 80 to 100), “he/she likes it” (from 30 to 50), “he/she thinks it's OK” (at 0), “he/she does not like it” (from −30 to −50) and “he/she hates it” (from −80 to −100) [Sharafi et al., 2015]. Participants also could mark “never tried/done.” Parents/caregivers completed the PALS for their young children (generally < 8 years), older children with parent/caregiver assistance or by themselves.

The food/beverages were grouped as fruits (apple, strawberry, watermelon, banana, orange juice, raisins), vegetables (carrots, sweet potato/yam, broccoli, salad, spinach/collard greens, corn, tomato, peas), fat/sweet/salty (soda, ice cream, cookies/cake, candy bar, sugary cereals, French fries, whole milk, apple juice, deli meats, butter/margarine) and protein (tuna/salmon, beans, eggs, yogurt, peanut butter, cheese). PALS also included 3 nonfoods (brushing teeth, taking a bath, getting dressed) to generalize the scale beyond foods/beverages, improve the ability to compare participants [Peracchio et al., 2012] and to screen for dental hygiene.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS (version 24, IMB Corporation), with a significance criterion of p ≤ 0.05. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were described. PALS feasibility was assessed by frequency of completed and interpretable surveys from consented child/parent dyads and survey completion time. The food and nonfood groups were analyzed for internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) and PED-home for test-retest reliability with intraclass correlation coefficients, with 0.5–0.75 moderate reliability, 0.75–0.9 good reliability and > 0.90 as excellent reliability.

Differences in preference were tested for: age associations with Spearman rho correlations and demographic effects controlling for other variables, as described, in the analysis of covariance, including Levene's testing of equality of variances. Associations between food preference group and BMI percentile were tested with demographic variables in standard multiple regression analysis, testing for the assumptions of normality of distribution, multivariate outliers and collinearity.

Results

Of the 150 child/parent dyads who were approached for the study, 144 (96%) completed the survey (2 ineligible, 3 did not complete all survey questions, 1 had > 50% of “never tried” for PALS items). The sample (54% male) was diverse in age (25% 5–8 years; 35% 9–12 years; 40% 13–18 years) and race/ethnicity (15% African American, 44% Caucasian, 33% Hispanic, 3% Asian, 5% multiple); 43% of families received public health insurance. The majority reported no chronic medical conditions (77%); 14% reported having asthma. From BMI percentiles, 3% of the children were underweight (< 5th), 50% normal weight (5th–85th), 22% overweight (85th–95th), 17% obese (95th–100th) and 8% extremely obese (≥120% of the 95th); this distribution is consistent with US estimates [Ogden et al., 2016].

PALS Descriptive Statistics

Average PED survey completion time was 3: 52 min (range 1: 22 to 13: 35). The food and nonfood groups were at or approached acceptable internal reliability of 0.7 (Table 1). Vegetables were least liked; fat/sweet/salty and pleasurable nonfoods were most liked.

Table 1.

Reported level of liking/disliking of items on the Pediatric Adapted Liking Survey (PALS), organized by group, among 144 children (ages 5–18 years)

| Males (n = 78) |

Females (n = 66) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 95.0% CI | mean | 95.0% CI | |

| Fruit (α = 0.555)1 | 31.1 | 26.7 to 35.5 | 31.3 | 26.7 to 35.8 |

| Orange juice | 43.2 | 36.8 to 49.6 | 44.5 | 37.4 to 51.6 |

| Strawberry | 38.4 | 31.2 to 45.5 | 40.5 | 32.6 to 48.4 |

| Watermelon | 36.5 | 28.7 to 44.3 | 40.5 | 32.4 to 48.6 |

| Banana | 36.0 | 28.2 to 43.7 | 30.5 | 21.5 to 39.5 |

| Apple | 30.9 | 24.5 to 37.2 | 34.9 | 28.3 to 41.5 |

| Raisins | 1.8 | −8.39 to 12.0 | −3.4 | −14.5 to 7.7 |

| Vegetable (α = 0.724) | 9.8 | 3.8 to 15.8 | 12.2 | 5.8 to 18.6 |

| Corn | 36.9 | 29.8 to 44.0 | 45.2 | 38.7 to 51.7 |

| Salad | 18.5 | 8.7 to 28.2 | 27.3 | 17.1 to 37.4 |

| Broccoli | 6.6 | −3.8 to 16.9 | 16.0 | 5.0 to 26.9 |

| Carrots | 9.6 | 0.4 to 18.7 | 11.6 | 1.12 to 22.1 |

| Peas | 7.6 | −2.6 to 17.8 | −0.7 | −12.6 to 11.3 |

| Tomatoes | −1.3 | −11.3 to 8.7 | −2 | −14.2 to 10.3 |

| Spinach/collard greens | −9.2 | −18.8 to 0.4 | −11.6 | −22.9 to −0.3 |

| Fat/sweet/salty (α = 0.702) | 36.9 | 33.3 to 40.5 | 34.2 | 30.6 to 37.8 |

| Ice cream | 46.1 | 41.7 to 50.5 | 46.6 | 41.8 to 51.3 |

| French fries | 43.6 | 38.3 to 48.8 | 46.6 | 41.5 to 51.7 |

| Salty snacks | 46.0 | 41.4 to 50.5 | 40.8 | 34.4 to 47.3 |

| Cookies/cake | 44.1 | 38.4 to 49.8 | 40.6 | 34.0 to 47.3 |

| Sugary cereals | 41.9 | 35.6 to 48.2 | 39.2 | 32.2 to 46.1 |

| Candy bar | 36.6 | 29.4 to 43.8 | 37.0 | 30.5 to 43.5 |

| Deli meat | 36.7 | 29.7 to 43.7 | 28.8 | 19.4 to 38.2 |

| Apple juice | 34.8 | 27.6 to 42.1 | 26.5 | 17.2 to 35.8 |

| Soda | 24.5 | 16.4 to 32.6 | 29.1 | 20.7 to 37.5 |

| Butter/margarine | 23.9 | 16.1 to 31.7 | 28.5 | 20.6 to 36.4 |

| Whole milk | 27.8 | 18.9 to 36.7 | 11.8 | 0.5 to 23.1 |

| Protein (α = 0.404) | 26.2 | 21.4 to 30.9 | 20.9 | 16.3 to 25.5 |

| Eggs | 37.7 | 31.0 to 44.4 | 38.8 | 31.8 to 45.7 |

| Cheese | 35.6 | 28.1 to 43.1 | 37.2 | 28.5 to 45.9 |

| Yogurt | 31.0 | 23.5 to 38.5 | 37.5 | 29.5 to 45.5 |

| Peanut butter | 24.5 | 15.6 to 33.3 | 19.4 | 9.2 to 29.6 |

| Beans/chickpeas | 14.7 | 4.3 to 25.2 | −0.4 | −11.7 to 11.0 |

| Tuna/salmon | 15.1 | 3.9 to 26.3 | −8.6 | −20.6 to 3.4 |

| Nonfoods (α = 0.635) | 35.1 | 30.0 to 40.2 | 40.8 | 35.6 to 46.0 |

| Taking a bath | 41.5 | 35.6 to 47.5 | 41.9 | 34.9 to 48.9 |

| Getting dressed | 38.4 | 31.9 to 44.9 | 44.7 | 38.7 to 50.7 |

| Brushing teeth | 25.3 | 17.7 to 32.9 | 35.0 | 27.5 to 42.5 |

The continuous scale was ±100 maximum/minimum, labeled left to right, as “he/she loves it” (from 80 to 100), “he/she likes it” (from 30 to 50), “he/she thinks it's OK” (at 0), “he/she does not like it” (from −30 to −50), and “he/she hates it” (from −80 to −100).

Cronbach's alpha as a measure of internal reliability of the group.

Of those 144 eligible PED survey responses, 57% completed and returned the home survey (n = 82). There were no statistically significant differences in gender, age or race/ethnicity in the sample who completed the PALS in the PED versus the PED and home. The surveys were returned an average of 8 days after the initial PED visit (range 0–42). The test-retest reliability from PED to home ranged from good to excellent (intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.79 for fat/sweet/salty to 0.91 for vegetable groups).

Preference for Brushing Teeth and Relative Preference for Sweets and Fruits

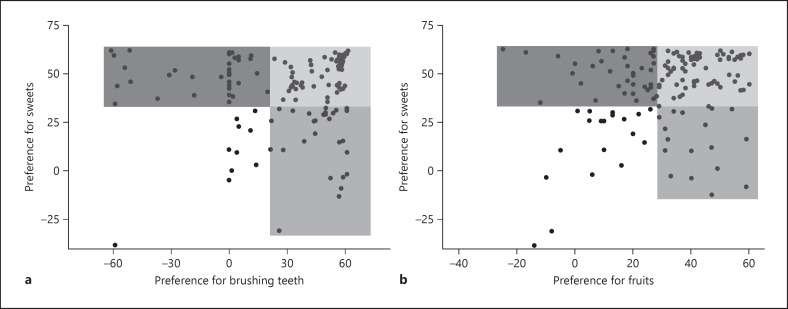

The average preference for brushing teeth neared that for fruits (average = 29.7 ± 32.4). Independently from significant age-related increases in brushing preference, a greater brushing preference tended to occur in females versus males and children from families with public versus private insurance (p < 0.1). Joint comparison of preference for sweets versus brushing teeth or fruits identified potential for tailored messages as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Relative preference for sweets versus brushing teeth (a) and fruits (b) in children and potential tailored and motivational messages to lower dental caries and obesity risk. Higher preference for sweets and brushing or fruits (lightest tint) – reinforce the positive behavior (liking brushing teeth or fruit) and modify the less healthy behavior (e.g., less cariogenic sweets, eating fruit versus sweets, decreasing sweet food consumption to lower sweet preference). Lower sweet/higher preference for brushing or fruits (middle tint) – reinforce this positive behavior and extend to other obesity prevention and dental caries prevention messages (e.g., consuming other foods such as vegetables and milk; fluoridation; physical activity). Lower brushing or fruit preference/higher sweet preference (darkest tint) – engaging child and family in dialogue to identify potential barriers to brushing and fruit preference. Motivational interviewing to identify the behavior(s) the child and family is/are willing to address to improve preference for brushing and fruits and/or methods to moderate sweet preference.

Food Group Preference by Demography and BMI Percentile

Fat/sweet/salty preference showed age-related declines (ρ = −0.19, p < 0.05), without significant age effects on preferences for fruits, vegetables and protein. Overall, boys and girls did not differ significantly in food group preference; however, among older children (≥9 years), boys reported a significantly greater preference for protein foods (p < 0.05), and among younger children (5- to 8-year-olds), girls reported a significantly greater preference for fruits and protein foods (p ≤ 0.05). Private versus public health insurance did not associate significantly with preference for the food groups, when controlling for age and gender.

The only significant relationship between BMI percentile and food preference was for fat/sweet/salty foods, and this association varied between girls and boys. Girls with greater adiposities reported a significantly greater preference for fat/sweet/salty foods (β = 0.32, p < 0.05, 95% confidence intervals 0.14–1.147); the relationship was not significant in the boys. The relationship between BMI percentile and preference for fruits, vegetables and proteins was not significant in either boys or girls.

Discussion

The present study assessed the feasibility, reliability and utility of the PALS to screen for children's dietary behaviors in a clinical setting. Most child/parent dyads completed the PALS (96% completion rate), in an average time of < 4 min. PALS showed good to excellent PED-home test-retest reliability. Comparing preferences for food with brushing teeth and with BMI percentile suggested topics for tailored prevention messages.

Elevated rates of childhood dental caries and obesity call for multi-tiered approaches, including prevention efforts in clinical settings [Garcia et al., 2017]. Chronic illnesses have been targeted in the PED, including screening, brief interventions and referrals [Chandler et al., 2015; Haber et al., 2015; Herndon et al., 2017; Vaughn et al., 2012]. Adolescents and low-income children who use PEDs have been shown to have unhealthy dietary behaviors and often do not obtain primary medical or preventive dental care [Chandler et al., 2015; Wall et al., 2014]. Brief interventions for obesity treatment and prevention have successfully been accomplished in the PED [Haber et al., 2015]. The PALS allowed quick screening of dietary behaviors; children and child/parent dyads readily completed the PALS in the PED while being treated for nonurgent issues. The PALS responses, including relative liking of sweets versus brushing teeth or fruits, suggested direction for tailored messages (Fig. 1). For children who reported high liking for sweets and teeth brushing, appropriate oral hygiene may attenuate negative effects of sugar consumption on caries risk [Touger-Decker and van Loveren, 2003]. About 60% of children reported liking whole and dried fruits, which can offer sweetness equivalent to sugar sweeteners, and substitute for high-added sugar foods and beverages in the diet. Experts in the development of sweet preference support that exposing children to less sweetness, both sugar and nonnutritive sweeteners, supports the development and maintenance of preference for healthy sweets (e.g., whole fruits) [Mennella et al., 2016]. Tailoring dietary recommendations to food preference patterns can result in effective behavioral interventions [Turner-McGrievy et al., 2013]. Simple messages delivered in health care settings can help support obesity and caries prevention efforts [Cloutier et al., 2015].

We observed a significant association between preference for fat/sweet/salty foods and BMI percentile only among girls, which is consistent with a large, multicountry study of elementary-age children [Lanfer et al., 2012], but with sampled food preference instead of survey preference in our study. Gender differences in sweet-adiposity relationships may be explained by different parental influences on dietary behaviors, body weight concerns as reported among Caucasian girls from middle-class families [Rollins et al., 2011]; these findings do not appear to explain the fat/sweet/salty preference relationship with weight in females among our ethnically/racially diverse sample.

The PALS was used to construct statistically reliable groups of foods associated with diet healthiness including fat/sweet/salty, fruits, vegetables and protein. Survey-reported preferences for foods/beverages can serve as proxy of usual intake as supported by its correlation with biomarkers of nutritional status [Pallister et al., 2015; Sharafi et al., 2015, 2016]. Assessing preference is cognitively easier than recalling behavior [Johnson, 1983] required of dietary assessment/screening tools. In this study, the PALS was completed in paper format and hand measured. Using an online platform could provide the child/parent dyad and clinician immediate feedback for tailored messages [Vosburgh, 2016]. From unpublished data of 54 parent-child dyads, the majority (averaging 85%) reported that completing the PALS got them to think about their behaviors and that simple tailored messages from the PALS were helpful.

The present study had limitations and strengths. Since data were a convenience sample from a single urban PED, results may not be generalized. Response bias cannot be ruled out, and dental health was not measured. Despite these limitations, the sample had diversity in race/ethnicity, measured adiposity (versus self-report) and overweight/obesity risk that parallels US prevalence.

Conclusion

Screening for dietary behaviors in busy clinical settings with a simple preference survey was feasible and reliable, with a high participation rate and short administration time. Examples are provided on how clinicians could use the survey responses to tailor diet and health behavior messages as part of multilevel interventions to prevent dental caries and obesity.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

S.R.S.: conception of study, management of data collection, interpretation of data, and initial drafting of manuscript. S.T.J.: initial drafting and revision of manuscript. S.M.O.: data analysis, drafting and revision of manuscript. V.B.D.: conception of study, interpretation of data, drafting and revision of manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 1001056 (Duffy, principal investigator).

References

- Arheiam A, Brown SL, Burnside G, Higham SM, Albadri S, Harris RV. The use of diet diaries in general dental practice in England. Community Dent Health. 2016;33:267–273. doi: 10.1922/CDH_3928Arheiam07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bel-Serrat S, Julian-Almarcegui C, Gonzalez-Gross M, Mouratidou T, Bornhorst C, Grammatikaki E, Kersting M, Cuenca-Garcia M, Gottrand F, Molnar D, Hallstrom L, Dallongeville J, Plada M, Roccaldo R, Widhalm K, Moreno LA, Manios Y, De Henauw S, Leclercq C, Vandevijvere S, Lioret S, Gutin B, Huybrechts I. Correlates of dietary energy misreporting among European adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study. Br J Nutr. 2016;115:1439–1452. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516000283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler I, Rosenthal L, Carroll-Scott A, Peters SM, McCaslin C, Ickovics JR. Adolescents who visit the emergency department are more likely to make unhealthy dietary choices: an opportunity for behavioral intervention. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26:701–711. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier MM, Wiley J, Huedo-Medina T, Ohannessian CM, Grant A, Hernandez D, Gorin AA. Outcomes from a pediatric primary care weight management program: steps to growing up healthy. J Pediatr. 2015;167:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.028. e371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia RI, Kleinman D, Holt K, Battrell A, Casamassimo P, Grover J, Tinanoff N. Healthy futures: engaging the oral health community in childhood obesity prevention - conference summary and recommendations. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77((suppl)):S136–S140. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JJ, Atti S, Gerber LM, Waseem M. Promoting an obesity education program among minority patients in a single urban pediatric Emergency Department (ED) Int J Emerg Med. 2015;8:38. doi: 10.1186/s12245-015-0086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden C, Bowler JO, Chambers S, Freeman R, Humphris G, Richards D, Cecil JE. Obesity and dental caries in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:289–308. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon JB, Crall JJ, Carden DL, Catalanotto FA, Tomar SL, Aravamudhan K, Light JK, Shenkman EA. Measuring quality: caries-related emergency department visits and follow-up among children. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:252–262. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izakovicova Holla L, Borilova Linhartova P, Lucanova S, Kastovsky J, Musilova K, Bartosova M, Kukletova M, Kukla L, Dusek L. GLUT2 and TAS1R2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to dental caries. Caries Res. 2015;49:417–424. doi: 10.1159/000430958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, A multiple-entry, modular memory system . The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. In: Bower G, editor. vol 17. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. pp 81–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfer A, Knof K, Barba G, Veidebaum T, Papoutsou S, de Henauw S, Soos T, Moreno LA, Ahrens W, Lissner L. Taste preferences in association with dietary habits and weight status in European children: results from the IDEFICS study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:27–34. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel SM, Marcenes W, Watt RG, Sheiham A. The relationship between sweetness preference and dental caries in mother/child pairs from Maringa-Pr, Brazil. Int Dent J. 2001;51:83–88. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella JA, Bobowski NK, Reed DR. The development of sweet taste: from biology to hedonics. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaboration on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR) Measures registry. 2017 http://www.nccor.org/nccor-tools/measures/ [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2292–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallister T, Sharafi M, Lachance G, Pirastu N, Mohney RP, MacGregor A, Feskens EJ, Duffy V, Spector TD, Menni C. Food preference patterns in a UK twin cohort. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2015;18:793–805. doi: 10.1017/thg.2015.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peracchio HL, Henebery KE, Sharafi M, Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Otitis media exposure associates with dietary preference and adiposity: a community-based observational study of at-risk preschoolers. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BY, Loken E, Birch LL. Preferences predict food intake from 5 to 11 years, but not in girls with higher weight concerns, dietary restraint, and %body fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2190–2197. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi M, Duffy VB, Miller RJ, Winchester SB, Sullivan MC. Dietary behaviors of adults born prematurely may explain future risk for cardiovascular disease. Appetite. 2016;99:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi M, Perrachio H, Scarmo S, Huedo-Medina TB, Mayne ST, Cartmel B, Duffy VB. Preschool-Adapted Liking Survey (PALS): a brief and valid method to assess dietary quality of preschoolers. Child Obes. 2015;11:530–540. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touger-Decker R, van Loveren C. Sugars and dental caries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:881S–892S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.881S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuorila H, Huotilainen A, Lähteenmäki L, Ollila S, Tuomi-Nurmi S, Urala N. Comparison of affective rating scales and their relationship to variables reflecting food consumption. Food Quality Pref. 2008;19:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Turner-McGrievy G, Tate DF, Moore D, Popkin B. Taking the bitter with the sweet: relationship of supertasting and sweet preference with metabolic syndrome and dietary intake. J Food Sci. 2013;78:S336–S342. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn LM, Nabors L, Pelley TJ, Hampton RR, Jacquez F, Mahabee-Gittens EM. Obesity screening in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:548–552. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318258ada0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh K. Childhood Obesity Prevention in Income-Disadvantaged Populations: An Evaluation of Two Novel Approaches; masters thesis in Health Promotion Sciences, Allied Health Sciences, University of Connecticut. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Wall T, Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Majority of dental-related emergency department visits lack urgency and can be diverted to dental offices. Health Policy Institute Research Brief, American Dental Association. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Oral health. 2012 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz G, Ermis RB, Calapoglu NS, Celik EU, Turel GY. Gene-environment interactions in the etiology of dental caries. J Dent Res. 2016;95:74–79. doi: 10.1177/0022034515605281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JC, Lee DJ, Afshari FS, Galang MT, Sukotjo C. Dentistry and obesity: a review and current status in US predoctoral dental education. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:1129–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]