Abstract

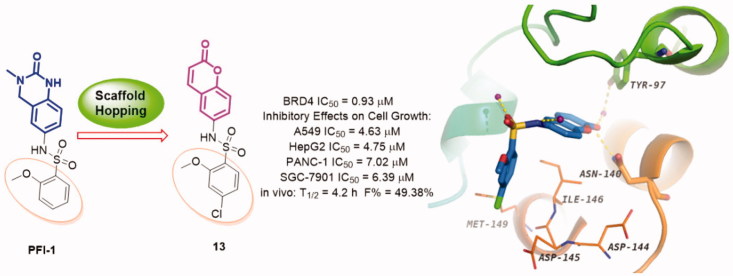

The bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) bromodomains, particularly BRD4, have been identified as promising therapeutic targets in the treatment of many human disorders such as cancer, inflammation, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Recently, the discovery of novel BRD4 inhibitors has garnered substantial interest. Starting from scaffold hopping of the reported compound dihydroquinazolinone (PFI-1), a series of coumarin derivatives were designed and synthesised as a new chemotype of BRD4 inhibitors. Interestingly, the representative compounds 13 exhibited potent BRD4 binding affinity and cell proliferation inhibitory activity, and especially displayed a favourable PK profile with high oral bioavailability (F = 49.38%) and metabolic stability (T1/2 = 4.2 h), meaningfully making it as a promising lead compound for further drug development.

KEYWORDS: Rational drug design, BRD4 bromodomain, synthesis, biological evaluation

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

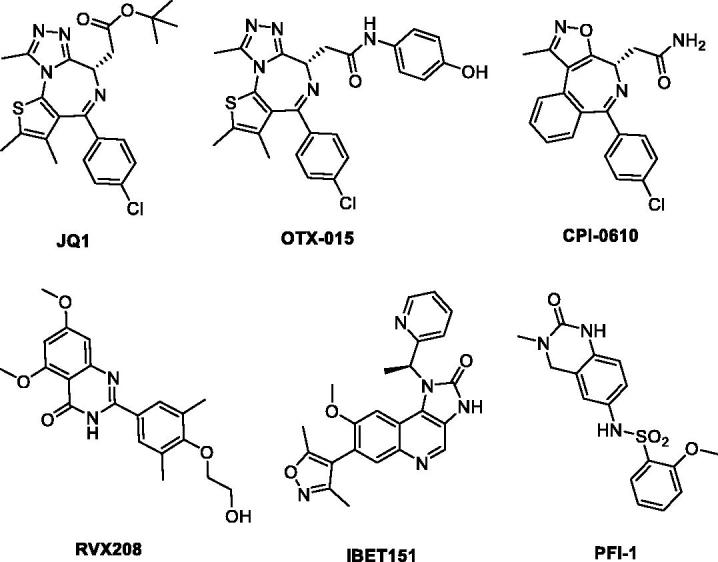

The bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family proteins, mainly including BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, are a kind of epigenetic regulatory proteins that selectively bind to acetylated lysines (KAc) of histone, thus translate chromatin status into transcription activation through RNA polymerase II and play critical roles in the regulation of gene transcription 1–3 . Among the BET family proteins, BRD4 has not just received a lot of attention, but been the most extensively studied one. The KAc residues bind into a hydrophobic pocket of the BRD4 proteins specifically with conserved asparagine (Asn140), also forming a water molecule-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions with tyrosine (Tyr97) 4 , 5 . Small molecule BRD4 inhibitors can block the binding, which leads to profound disruption of transcriptional programmes resulting in therapeutic potential in several conditions, such as inflammation and oncologic diseases 6–10 . In the last few years, a number of high-affinity small molecule ligands of BRD have been identified (Figure 1) 11–14 , wherein JQ-1 was the first reported potent BRD4 inhibitor and has been employed widely to evaluate its therapeutic potential in a great many preclinical human disease models 15 . Several JQ-1 analogues, such as OTX-015 16–18 and CPI-0610 19 , 20 have subsequently advanced into clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumours, haematological malignancies and other forms of human cancer. It was also worthy of attention that PFI-1, a dihydroquinazolinone compound reported to be a potent BRD inhibitor obtained through optimization of a fragment-derived hit 21 . However, the solubility and pharmacokinetics of PFI-1 are suboptimal 22 . Notwithstanding the above discovery, potent BRD4 inhibitors with novel chemotypes are still in high demand for only limited BRD4 inhibitors available in clinical trials.

Figure 1.

Representative, previously reported bromodomain inhibitors.

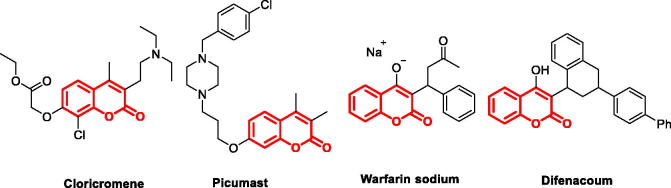

The natural products, normally with unique chemical structure, have long played an important role in drug discovery 23 . Coumarin (benzo-α-pyrone) skeleton found in nature has been considered as a privileged pharmacophore ascribed to the ability to exert noncovalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, van der Waals force, metal coordination, and electrostatic interactions, etc.), with the various active sites in therapy targets 24 , 25 . Coumarins skeleton have gained momentous attention in the last decades as a lead structure for the discovery of orally bioavailable anti-cancer, anti-HCV, anti-HIV, anti-Alzheimer, and anti-inflammatory agents 26–29 . Several coumarin-based derivatives, such as Cloricromene 30 , Picumast 31 , Warfarin sodium 32 , and Difenacoum 33 (Figure 2, coumarin skeleton marked in red) were approved for therapeutic purposes in clinic.

Figure 2.

Structures of approved coumarin-containing drugs.

Scaffold hopping can not only provide an alternative strategy for BRD4 inhibitor design, but also potentially lead the discovery of potent BRD4 inhibitors with novel and diverse chemotypes. The advantages of scaffold hopping, combining with the pharmacophore property of coumarin and the skeleton modifiability of PFI-1 much interest us to explore structurally novel BRD4 inhibitors. Herein, we reported the rational design, syntheses, and structure-activity relationship (SAR) exploration of novel coumarin heterocycle derivatives as potent BRD4 inhibitors via the scaffold hopping of PFI-1. Furthermore, in vitro anti-tumour test and in vivo preliminary pharmacokinetics study of representative compound also were described in this article.

Results and discussion

Design of new BRD4 inhibitors containing a coumarin scaffold

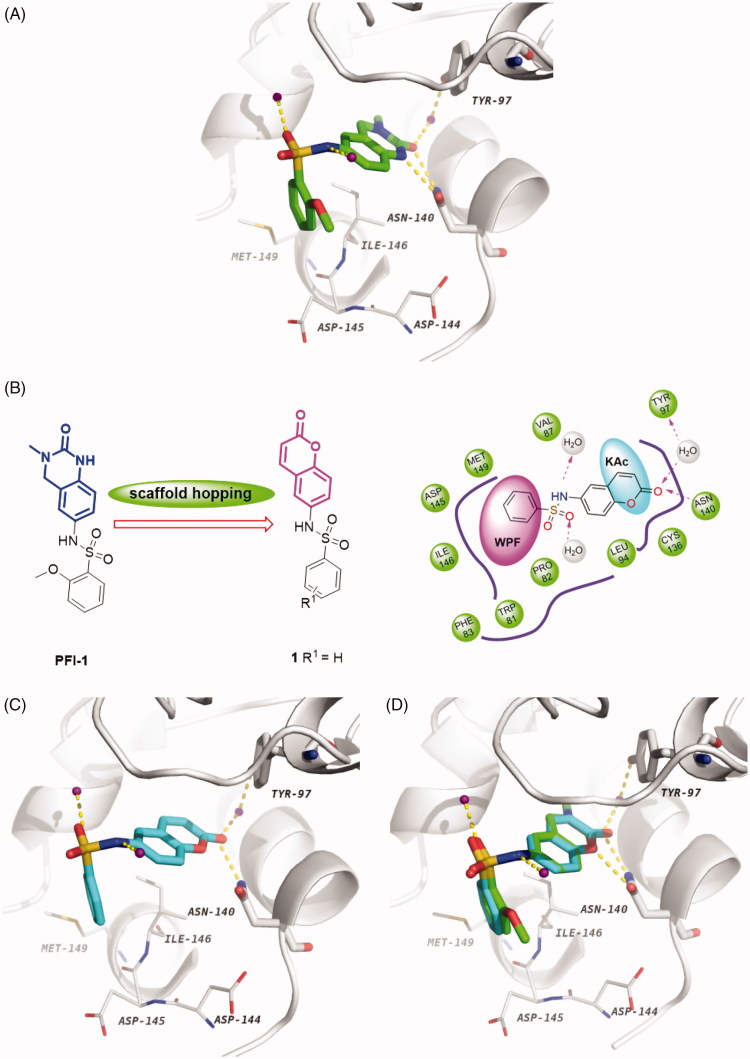

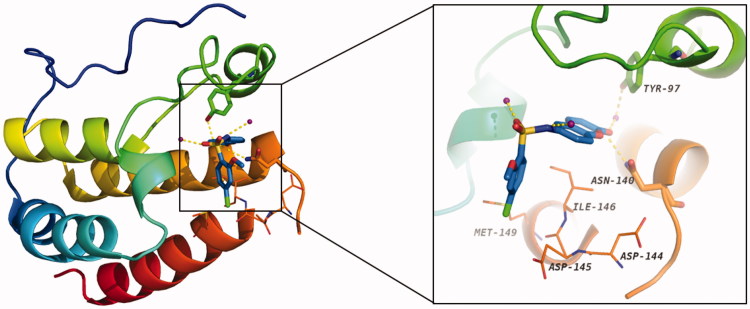

Scaffold hopping is a powerful and promising strategy for drug discovery 34 . It has been extensively used for the design of structurally novel bioactive molecules 35–38 , which generally incorporates ring opening, ring closure, heterocycle replacement, and shape/topology-based scaffold hopping 39 , 40 . Herein, we applied the heterocycle replacement and shape-based scaffold hopping strategy towards PFI-1, a BRD inhibitor developed by Pfizer Worldwide R&D. First, we analysed the binding mode of PFI-1 binds to the BRD4 bromodomain. X-ray crystallographic analysis reveals that PFI-1 binds to BRD4 with three key hydrogen bonds interactions, which are displayed in Figure 3(A). The carbonyl oxygen and NH group of the dihydroquinazolinone forms two critical hydrogen bonds with the conserved residue Asn140. Moreover, the carbonyl oxygen interacts with the conserved residue Tyr97 via a water-mediated hydrogen bond. The anisole group occupies the WPF (formed by residues W97, P98 and F99) shelf and forms hydrophobic interaction with Asp145, Ile146, and Met149. The sulphonamide forms two additional hydrogen bonds with two water molecules. With this structural information in mind, we hypothesised that rational replacement of the dihydroquinazolinone core via coumarin skeleton based on scaffold hopping would be tolerated (Figure 3(B)). Thus, a series of novel coumarin derivatives were designed. As shown in Figure 3(C), the docking mode of coumarin derivative 1 binds to BRD4 was consistent with that of PFI-1. The alignment results depicted in Figure 3(D) also indicated that 1 almost took the same interaction conformation as PFI-1 except that the hydrogen-bond interaction between NH and Asn140 was lost.

Figure 3.

(A) Crystal structure of BRD4 BD1 bound to PFI-1 (PDB ID: 4E96). The protein is shown as a light gray cartoon and PFI-1 is shown as sticks (carbon atoms in green, oxygens in red, nitrogens in blue and sulfurs in brown). (B) Design concept of new BRD4 inhibitors. (C) The docking model of 1 with BRD4 BD1 (carbon atoms in cyan). (D) Superimposition of PFI-1 (green carbon atoms) and 1 (cyan carbon atoms) in their putative bioactive conformations.

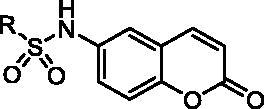

SAR studies of coumarin derivatives

With the understanding of binding conformation, our next work is to explore the SAR of the coumarin derivatives. We focused on the hydrophobic WPF shelf to develop compounds with improved affinity for BRD4. In order to optimise the interactions towards WPF shelf, diverse substituents at the R position were designed to investigate the chemical space for improving the activity. To ensure the R group extends to the WPF shelf and forms hydrophobic interactions with residues located there, we maintained the sulphamide linker. Thus, compounds 1 − 16 with R groups of aromatic groups, alkyl or cycloalkyl were designed and synthesised (Table 1). We preferentially evaluated the phenyl group. Compound 1 characterised by phenyl group has shown moderate BRD4 binding activity with an IC50 value of 6.59 μM in the AlphaScreen assay. When alkyl or cycloalkyl groups were used to occupy the WPF shelf, a > 3-fold decrease in affinity was found (Table 1, compounds 2–5), probably due to a reduction of hydrophobic interactions with WPF shelf. Generally, the cycloalkyl group compounds (compounds 2 and 3) were more tolerated than the chain alkyl compounds (4 and 5). Next, we paid our attention back to aromatic groups. An extensive SAR exploration was then conducted: displaying that diverse substitution at different positions of the phenyl group in 1 may lead to various effects on the BRD4 affinity. Our study showed that compounds bearing chlorine, methoxy group or tertiary butyl group at the para-position were tolerable (compounds 6–8). The inhibitory activities of 6–8 were similar to 1 with IC50 values of 2.97, 7.31, and 5.09 μM, respectively. The para-chlorine substituted analogue 6 was somewhat more potent than 7 and 8, which indicated that electron-withdrawing groups at the para-position might be favourable. We further investigated the impact of cyano group on meta-position, compound 9 maintained the similar potency at an IC50 value of 5.03 μM, which suggested that substitution at meta-position was also feasible. Surprisingly, the enhanced potency was achieved when substitutions were introduced at the ortho-position (compounds 10 and 11). The ortho-methoxy group analogue 11 showed significant increase with an IC50 value of 0.98 μM and is approximately 7-fold more potent than 1. Compound 11 was more potent than 10, which may due to the advisable sulphamide conformation caused by the larger methoxyl group on ortho-position. With the results that mono-substituent at para-position or ortho-position was favourable; we attempted to merge these two positions as bi-substituent. The resulting compound 12 and 13 displayed potent activity with IC50 values of 1.77 and 0.93 μM, respectively. It is interesting that compound 12 was slightly more potent than 10, while 13 was slightly more potency than 11, which may ascribe to greater lipophilicity because of the chlorine atom. For example, the lipophilic efficiency (LipE, −lg (IC50) − logP) of 13 and 11 was 3.2 and 3.9. For more understanding the SAR, we further replaced the phenyl ring of 1 by thienyl group, the resulting derivative 14 showed low binding activity. The replacement by larger aromatic group also led to a reduction of affinity (compounds 15 and 16).

Table 1.

Structure-activity relationship of the R substitutions on synthesized coumarin derivatives.

| Comp. No. | R | BRD4 IC50 (μM)a | cLogPb | LEc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

6.59 | 2.43 | 0.35 |

| 2 |  |

19.02 | 2.83 | 0.31 |

| 3 |  |

17.9 | 2.73 | 0.33 |

| 4 |  |

38.53 | 1.86 | 0.34 |

| 5 | 30.04 | 2.39 | 0.33 | |

| 6 |  |

2.97 | 2.55 | 0.34 |

| 7 |  |

7.31 | 3.18 | 0.33 |

| 8 |  |

5.09 | 4.26 | 0.30 |

| 9 |  |

5.03 | 2.19 | 0.32 |

| 10 |  |

2.21 | 2.88 | 0.36 |

| 11 |  |

0.98 | 2.07 | 0.37 |

| 12 |  |

1.77 | 3.60 | 0.35 |

| 13 |  |

0.93 | 2.82 | 0.36 |

| 14 |  |

9.26 | 2.16 | 0.35 |

| 15 |  |

12.23 | 3.60 | 0.28 |

| 16 |  |

18.42 | 2.68 | 0.28 |

| JQ1 | 0.06 | |||

| PFI-1d | 0.22 |

aThe IC50 values were tested by the AlphaScreen assay; bcLogP values were calculated using ChemBiodraw Ultra14.0; cLE (Ligand Efficiency) = 1.4 (pIC50/heavy atoms); dThe IC50 value was reported by Fish et al. 22 .

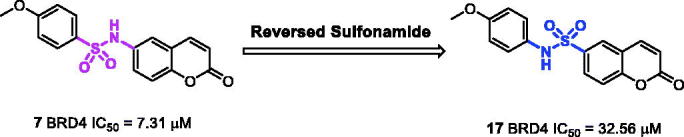

The x-ray crystal structure of PFI-1 bind to BRD4 revealed that the sulphonamide linker provides a specific angle turn for N-substitution to reach into WPF shelf. We were curious about that whether a reversed sulphonamide could achieve the same effect. We designed and synthesised a reversed sulphonamide compound 17 based on compound 7 (Figure 4). Unfortunately, 17 showed almost 5-fold decrease in potency compared with 7.

Figure 4.

The design and synthesis of reversed sulfonamide compound 17.

Docking study of the preferred configuration of representative compound 13

To disclose the structural basis for the high binding affinity of compound 13 to the BRD4 protein, we conducted the docking study of 13 in a complex with BRD4 (Figure 5). As expected, the coumarin moiety of 13 forms two hydrogen bonds with Asn140 and Tyr97 via a conserved water molecule in the KAc binding site of BRD4. The 4-chloro-2-methoxybenzene group occupies the hydrophobic WPF shelf and forms hydrophobic interactions with Met149, Asp144, Asp145, and Ile146. The sulphonamide forms two additional hydrogen bonds with two water molecules.

Figure 5.

The docking model (PDB ID: 4E96) of 13 with BRD4 BD1 (carbon atoms in blue). Water molecule is shown as purple sphere, and the hydrogen bonds are denoted by gold dash lines.

Evaluation of the inhibitory effects on cell growth

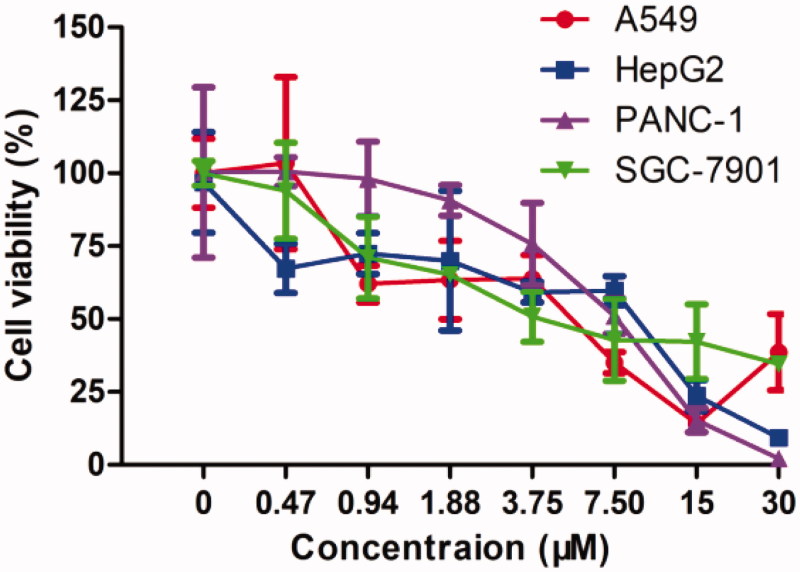

The representative compound 13 was next evaluated for its effects on the survival of human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells, pancreatic carcinoma PANC-1 cells, and gastric adenocarcinoma SGC-7901 cells with an MTT assay. The data obtained were summarised in Table 2 and dose–response curves were provided in Figure 6. Results showed that 13 potently inhibits the proliferation in these four cell lines, with IC50 values of 4.63, 4.75, 7.02, and 6.39 μM, respectively. Overall consideration of the data from the above assays, 13 has good profiles for further evaluation.

Table 2.

Anti-proliferation effects of 13 against four cell lines.

| Cancer type | Cell line | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung adenocarcinoma | A549 | 4.63 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | HepG2 | 4.75 |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | PANC-1 | 7.02 |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | SGC-7901 | 6.39 |

Figure 6.

Dose–response curves of 13 in incubation with cancer cell lines (mean ± SD, n = 3).

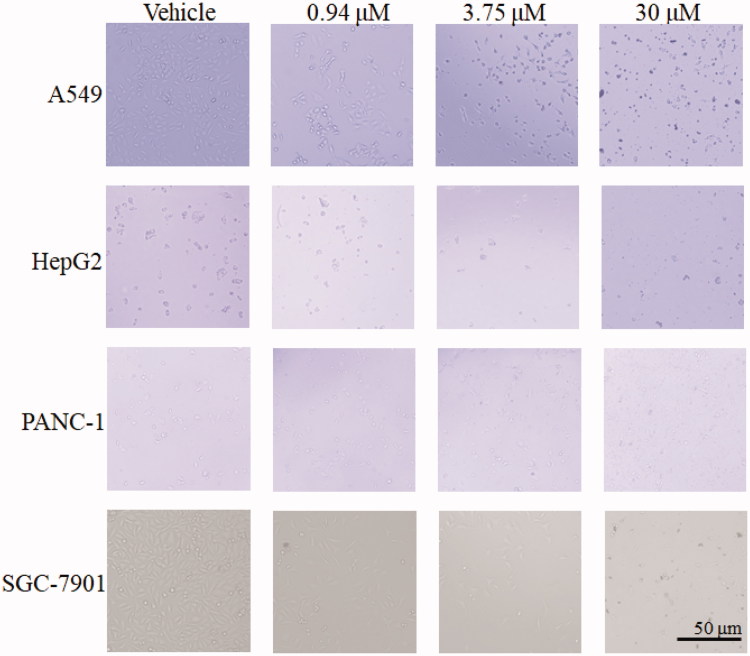

Effect of 13 on cells morphology

As shown in Figure 7, no abnormality was observed in the SGC-7901 cells, PANC-1 cells, HepG2, and A549 cells from the control, with oval or short fusiform, adhered to the wall and liked paving stone shape. Cells in 13-treated groups, with increased of dose, change became more obviously, contour was gradually clear, cell diopter strengthened, cells gradually became smaller and round, shrinking into the spherical, part of the cells was broken, and then fell off or suspended.

Figure 7.

Effect of 13 on A549, HepG2, PANC-1 and SGC-7901 cells morphology. Cells after treating with 13 under relevant concentrations for 24 h were observed by invert/phase contrast microscopy.

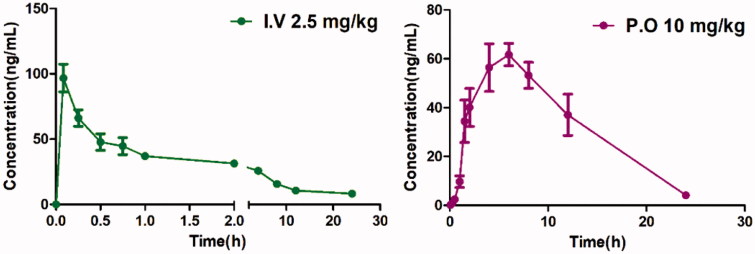

Assessment of pharmacokinetic (PK) properties for 13

To assess the potential of this series of compound in vivo, we evaluated 13 as a representative for its preliminary pharmacokinetics in Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats; the resulted data were listed in Table 3. The plasma was collected after a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg or an i.v. dose of 2.5 mg/kg (Figure 8). Compound 13 demonstrated preferable PK properties with a T 1/2 value of 4.2 h and a T max of 5.87 h. In addition, in the oral administration mode, 13 displayed good drug exposure with an AUC value of 790.65 μg/L*h and resulted in excellent oral bioavailability (49.38%), which is higher than that of PFI-1 (32%) 22 .

Table 3.

Intravenous (i.v.) and oral (p.o) pharmacokinetic profiles of compounds 13 in rats.

| Parameters | i.v. (2.5 mg/kg) | SD | p.o (10 mg/kg) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC(0–t) (μg/L*h) | 400.87 | 32.41 | 790.65 | 55.47 |

| AUC(0–∞) (μg/L*h) | 607.74 | 226.07 | 816.46 | 64.99 |

| T1/2 (h) | – | – | 4.2 | 0.29 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.083 | 0 | 5.87 | 0.95 |

| MRT0–t (h) | 7.9 | 0.81 | 8.5 | 0.66 |

| CLz (L/h/kg) | 4.46 | 1.4 | 12.30 | 10.93 |

| Vd (L/kg) | 84.28 | 28.10 | 74.28 | 5.19 |

| Cmax(μg/L) | 96.87 | 10.56 | 61.7 | 4.6 |

| F (%) | – | – | 49.38 | 5.45 |

*The statistical significance is meaningless due to the different dosages between PO and IV.

Figure 8.

The plasma concentration-time curve of 13.

Chemistry

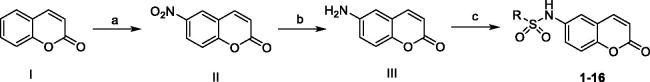

The methodology employed for the synthesis of the coumarin derivatives was demonstrated in Scheme 1. The commercially available 2H-chromen-2-one (I) reacted with concentrated nitric acid in sulphuric acid under 0–5 °C to produce compound II, which was then reduced in ammonium chloride and iron powder system to give the amino intermediate III. The target compounds were (1–16) were obtained by sulphonylation reactions between III and various sulphonyl chlorides in pyridine, which act as solvent, as well as the deacid reagent.

Scheme 1.

The synthetic route of compounds. Reagents and conditions: (a) HNO3/H2SO4; (b) SnCl2/HCl; (c) pyridine, sulphuryl chloride, rt.

Conclusion

In this study, we have designed and synthesized a series of coumarin-containing compounds based on scaffold hopping with the goal of improving the oral bioavailability of PFI-1 and obtaining entirely new chemotype of BRD4 inhibitors. Our efforts have led to the discovery of a representative compound 13 (4-chloro-2-methoxy-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulfonamide), which binds to BRD4 with nanomolar affinities and shows low micromolar potencies in cell growth inhibition against four human cancer cell lines. Significantly, it achieves excellent oral bioavailability (F = 49.38%) and is metabolically stable (T 1/2 = 4.2 h), which is preferable than PFI-1 (F = 32%). The obtained data suggested that 13 possesses a promising BRD4 inhibitory and orally bioavailable characteristic, worth of making it as a lead compound for further drug development.

Experimental section

BRD4 binding assay

The binding affinity was evaluated by a using AlphaScreen technology FRET assay. The biotinylated peptide binding to the reader domain of His-tagged protein is monitored by the singlet oxygen transfer from the Streptavidin-coated donor beads to the AlphaScreen Ni-chelate acceptor beads. Reagent:Reaction buffer:50 mM Hepes, pH7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05% CHAPS, 0.1% BSA, and 1% DMSO (the final DMSO concentration may different depending on compound stock and test concentrations). Bromodomain BRD4-full length: recombinant human bromodomain containing protein 4 (bromodomain 1 and 2; aa 2–1362; Genbank Accesstion # NM_058243), expressed in Sf9 insect cells with an N-terminal His-tag. MW = 156.5 kDa. Ligand (C-term-Biotin) Histone H4 peptide (1–21) K5/8/12/16Ac-Biotin Detection beads: PerkinElmer Donor beads: Streptavidin-coated donor beads, Acceptor beads: AlphaScreen Ni acceptor beads. Reaction procedure: (1) Deliver 2.5× BRD in wells of reaction plate except No BRD control wells. Add buffer instead. (2) Deliver compounds in 100% DMSO into the BRD mixture by Acoustic technology (Echo550; nanoliter range). Spin down and pre-incubation for 30 min. (3) Deliver 5 × Ligand. Spin and shake. (4) Incubate for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking. (5) Deliver 5× donor beads. Spin and shake. (6) Deliver 5 × acceptor beads. Spin and shake. Then gentle shaking in the dark for 60 min. (7) Alpha measurement (Ex/Em = 680/520–620 nm) in Enspire.

Cell culture

Human gastric carcinoma metastatic lymph node SGC-7901 cells, human pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells, human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells, and human lung carcinoma A549 cells were purchased from the Cell Center of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) or RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

MTT assay

Methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay was used to detect the cell survival rate. Briefly, cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 104cells/mL. Medium containing a certain concentration of compound (0, 0.47, 0.94, 1.88, 3.75, 7.50, 15.0, and 30 µM) was added into each well in a volume of 100 μL for 48 h, respectively. The cell morphology was observed by Invert/phase contrast microscopy (Nikon TE2000, Tokyo, Japan) (bar: 200 µm). Then 20 μL MTT solutions (Sigma, Shanghai, China) was added into each well and followed by incubation at 37 °C for 4 h. An aliquot of 150 μL of DMSO was further added after discarding culture medium. The crystals of formazan product were then dissolved by oscillating for 10 min. The optical density (OD) value was detected using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, imark, Hercules, CA) at a wavelength of 570 nm. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Cell survival rate (%) = (OD of administration group − OD of blank group)/(OD of control group − OD of blank group)×100%. The value of inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) was calculated by GraphPad Prism 5 software (La Jolla, CA).

In vivo PK studies

SD female rats, 6 − 8-weeks old were selected for dosing. Three mice were randomly grouped per time point. Mice were received either a single intravenous injection of 2.5 mg/kg compound or a single oral administration of 10 mg/kg compound. Compounds were given as solutions in DMSO/PEG 200/water. Blood samples were collected from rats at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h and were further processed to obtain plasma by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. Plasma concentrations of the compounds were determined using the liquid chromatography − tandem mass spectrometry (LC − MS/MS) method. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated WinNonlin. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences on Use and Care of Animals, in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Computer aided drug design

The X-RAY crystal structure of BRD4 (PDB 4E96) were downloaded from Protein Data Bank (PDB) and prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard in the Schro¨dinger suite 41 . Due to its good reproducibility of cocrystallised ligand conformations and accuracy in molecular docking and scoring 42 , Glide was selected as the molecular docking tool. A receptor grid was defined as the ligand-binding site search region based on the cocrystallised ligand and an enclosing box that was in similar in size to the cocrystallised ligand were used to capture the compounds to be docked. The cognate ligand of PDB 4E96 as well as the target compounds were prepared by LigPrep module in Schro¨dinger with the ionization stage not changed and Generate tautomers not selected. For each ligand, one low energy ring conformation was generated. The prepared compounds were submitted for molecular docking. Based on the Glide score and interactions formed between the compounds and the active site, the best conformation of each compound was conserved. Finally, the potential compounds were flexibly docked into the binding site with standard precision (SP) docking mode 43 . All the remaining parameters were kept as default settings.

Chemistry

General chemistry

Commercially available reagents and anhydrous solvents were used without further purification. The crude reaction product was purified by Flash chromatography using silica gel (300–400 mesh). All reactions were monitored by TLC (thin layer chromatography), using silica gel plates with fluorescence F254 and UV light visualization. If necessary, further purification was performed on a preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Waters 2545) with a C18 reverse phase column. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV-400 spectrometer at 400 MHz. Coupling constants (J) was expressed in hertz (Hz). Each signal is identified by its chemical shift δ expressed in parts per million (ppm). HRMS analyses were performed under ESI (electrospray ionization) using a TOF (time-of-flight) analyser in V mode with a mass resolution of 9000.

Synthetic procedure of compound II

To a solution of 2H-chromen-2-one (2.9 g, 20 mmol) in H2SO4 (10 mL) was added HNO3 (1.3 g, 20.1 mmol) at 0 °C then the reaction mixture was stirred at 0–5 °C for 2 h. After the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (200 mL × 3). The organic layer was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4.

The solid was filtered off, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude product was yield 6-nitro-2H-chromen-2-one (II) without purification.

Synthetic procedure and characterization of compound III

To a reaction mixture of Fe powder (1.7 g, 31 mmol) and NH4Cl (0.8 g, 15 mmol) in EtOH (30 mL) and water (10 mL) was added 6-nitro-2H-chromen-2-one (1.5 g, 7.8 mmol), then the reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h. After the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature (rt). The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (100 mL × 3). The organic layer was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. The solid was filtered off and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude product was purified by silica gel chromatography with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (5/1, v/v) to yield 6-amino-2H-chromen-2-one (III) (1.04 g, yield 86.7%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.34 (s, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.66 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.98, 152.78, 143.91, 129.03, 127.01, 122.82, 119.74, 118.16, 117.81.

Synthetic procedure and characterization of compound 1–17

To a solution of 6-amino-2H-chromen-2-one (III) (80 mg, 0.5 mmol) and corresponding sulphonyl chloride (0.5 mmol) in DCM (5 mL) was added pyridine (0.3 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with DCM (30 mL × 3). The organic layer was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. The solid was filtered off, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude product was purified by silica gel chromatography with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (3/1, v/v) to yield 1–17.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (1): White solids (yield 89.6%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.49 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (dt, J = 26.7, 7.3 Hz, 3H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.31 (s, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.18, 150.79, 144.30, 139.61, 134.39, 133.51, 129.79, 127.14, 125.19, 119.92, 119.55, 117.70, 117.33. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C11H8N7O2S ([M + H]+) 302.0460, found 302.0480.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)cyclohexanesulphonamide (2): Yellow solids (yield 92.3%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.97 (s, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (t, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 2H), 1.76 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 2H), 1.59 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 1.43 (m, 2H), 1.18 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.31, 150.34, 144.55, 135.38, 124.39, 119.63, 118.65, 117.74, 117.23, 59.50, 26.45, 25.19, 24.77. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C15H18NO4S ([M + H]+) 308.0957, found 308.0952.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)cyclopentanesulphonamide (3): Pink solids (yield 85.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.95 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.37 (m, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 3.64–3.49 (m, 1H), 1.94–1.85 (m, 4H), 1.65 (m, 4H), 1.55 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.31, 150.53, 144.52, 135.20, 124.93, 119.63, 119.25, 117.73, 117.23, 60.21, 27.77, 25.87. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C14H16NO4S ([M + H]+) 294.0800, found 294.0794.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)propane-1-sulphonamide (4): Pink solids (yield 88.4%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.98 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.42 (q, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.51 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 3.23–3.00 (m, 2H), 1.72 (m, 2H), 0.96 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H) 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.31, 150.51, 144.51, 135.14, 124.68, 119.65, 118.96, 117.78, 117.25, 52.86, 17.30, 12.99. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C12H14NO4S ([M + H]+) 268.0644, found 268.0635.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)butane-1-sulphonamide (5): White solids (yield 93.1%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.99 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.42 (q, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.51 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.18–3.07 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.61 (m, 2H), 1.45–1.30 (m, 2H), 0.85 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.29, 150.50, 144.49, 135.13, 124.66, 119.64, 118.96, 117.76, 117.24, 50.85, 25.57, 21.12, 13.88. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C13H16NO4S ([M + H]+) 282.0800, found 282.0792.

4-chloro-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (6): Pink solids (yield 86.2%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.55 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.31 (m 2H), 6.49 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.16, 151.00, 144.31, 138.42, 134.03, 129.98, 129.10, 125.53, 120.36, 119.63, 117.81, 117.37. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C15H11NO4SCl ([M + H]+) 336.0097, found 336.0085.

4-methoxy-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzene sulphonamide (7): Light pink solids (yield 72.8%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.34 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.47 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 162.98, 160.21, 150.66, 144.37, 134.69, 131.20, 129.39, 125.01, 119.57, 117.66, 117.28, 114.90, 56.00. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16H14NO5S ([M + H]+) 332.0593, found 332.0586.

4-(tert-butyl)-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzene sulphonamide (8): Pink solids (yield 85.3%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.48 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.31 (s, 2H), 6.47 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 1.25 (s, 9H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.19, 156.48, 150.60, 144.36, 137.03, 134.62, 127.03, 126.65, 124.70, 119.50, 119.29, 117.73, 117.33, 35.32, 31.16. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C19H20NO4S ([M + H]+) 358.1113, found 358.1109.

3-cyano-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzene sulphonamide (9): Light pink solids (Yield 87.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.67 (s, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H), 8.18 – 8.00 (m, 3H), 7.80 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (dt, J = 8.9, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.14, 151.14, 144.27, 140.80, 137.18, 133.61, 131.57, 131.35, 130.72, 125.68, 120.59, 119.68, 117.87, 117.39, 113.08. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16H11N2O4S ([M + H]+) 327.0440, found 327.0429.

2-chloro-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (10): Light pink solids (Yield 91.0%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.86 (s, 1H), 8.07 (m, 2H), 7.70 – 7.60 (m, 2H), 7.53 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.35 (m, 2H), 6.47 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.13, 150.63, 144.19, 136.68, 135.21, 133.78, 132.36, 132.08, 131.21, 128.21, 124.37, 119.55, 118.98, 117.76, 117.40. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C11H7N7O2SCl ([M + H]+) 336.0070, found 336.0091.

2-methoxy-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (11): Light pink solids (Yield 84.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.20 (s, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.31 (m, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.22, 156.81, 150.43, 144.33, 135.68, 134.70, 130.73, 126.50, 124.63, 120.59, 119.37, 119.10, 117.48, 117.24, 113.32. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16 H14 N O5 S ([M + H]+) 332.0593, found 332.0587.

2,4-dichloro-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (12): Yellow solids (Yield 83.1%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.92 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.33 (s, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 180.07, 150.82, 144.22, 139.20, 135.73, 133.45, 133.38, 132.45, 131.90, 128.47, 124.68, 119.82, 119.38, 117.86, 117.45. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C15H10NO4SCl2 ([M + H]+) 369.9708, found 369.9694.

4-chloro-2-methoxy-N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)benzenesulphonamide (13): Pink solids (yield 81.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.37 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.31 (s, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.19, 155.71, 150.74, 144.32, 135.23, 134.16, 129.72, 128.03, 124.97, 124.15, 119.55, 117.58, 117.33, 115.49, 57.09. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16H13NO5SCl ([M + H]+) 366.0203, found 366.0193.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)thiophene-2-sulphonamide (14): Light pink solids (yield 90.5%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.61 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.39–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.1–7.09 (m, 1H), 6.49 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.19, 151.04, 144.33, 139.93, 134.11, 133.13, 128.18, 125.42, 120.28, 119.57, 117.64, 117.36. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C13H10NO4S2 ([M + H]+) 308.0051, found 308.0044.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)naphthalene-2-sulphonamide (15): Light pink solids (yield 83.5%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.65 (s, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 8.09–7.97 (m, 2H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (m, 2H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.34 (m 2H), 6.47 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 160.15, 150.77, 144.24, 136.63, 134.75, 134.37, 132.00, 130.00, 129.70, 129.48, 128.54, 128.22, 125.16, 122.44, 119.90, 119.55, 117.70, 117.30. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C19H14NO4S ([M + H]+) 352.0644, found 352.0634.

N-(2-oxo-2H-chromen-6-yl)-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-5-sulphonamide (16): Light pink solids (yield 91.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.28 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.24 (m, 2H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.20 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 163.7, 160.24, 150.54, 144.40, 134.77, 131.21, 129.41, 128.67, 124.87, 124.54, 119.46, 117.65, 117.27, 109.55, 72.69, 28.83. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C17H14NO5S ([M + H]+) 344.0593, found 344.0586.

N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxo-2H-chromene-6-sulphonamide (17): Light purple solids (yield 77.2%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.03 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.60, 157.22, 156.17, 143.92, 135.89, 130.15, 128.08, 124.39, 119.29, 118.20, 117.96, 114.85, 55.62. HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16H13NO5NaS ([M + Na]+) 354.0412, found 354.0398.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by The National Natural Science Funds of China [81803372], Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province [LY17H310008], Key Laboratory of Neuropsychiatric Drug Research of Zhejiang Province [2019E10021], Doctoral Fund of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences [A11701Q] and Health Commission of Zhejiang Province [2019RC141, XKQ-010–001 and WJK-ZJ-1918].

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Taniguchi Y. The bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) family: functional anatomy of BET paralogous proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:pii: E1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deeney JT, Belkina AC, Shirihai OS, et al. . BET bromodomain proteins Brd2, Brd3 and Brd4 selectively regulate metabolic pathways in the pancreatic beta-cell. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith SG, Zhou MM. The bromodomain: a new target in emerging epigenetic medicine. ACS Chem Biol 2016;11:598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lolli G, Caflisch A. High-throughput fragment docking into the BAZ2B bromodomain: efficient in silico screening for x-ray crystallography. ACS Chem Biol 2016;11:800–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Padmanabhan B, Mathur S, Manjula R, Tripathi S. Bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family proteins: new therapeutic targets in major diseases. J Biosci 2016;41:295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aird F, Kandela I, Mantis C. Reproducibility project: cancer B, replication study: BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Elife 2017;6:pii: e21253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bid HK, Kerk S. BET bromodomain inhibitor (JQ1) and tumor angiogenesis. Oncoscience 2016;3:316–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Devaiah BN, Gegonne A, Singer DS. Bromodomain 4: a cellular Swiss army knife. J Leukoc Biol 2016;100:679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujisawa T, Filippakopoulos P. Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their roles in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:246–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noguchi-Yachide T. BET bromodomain as a target of epigenetic therapy. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2016;64:540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jimenez I, Baruchel A, Doz F, Schulte J. Bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitors in pediatrics: a review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Theodoulou NH, Tomkinson NC, Prinjha RK, Humphreys PG. Clinical progress and pharmacology of small molecule bromodomain inhibitors. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2016;33:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Romero FA, Taylor AM, Crawford TD, et al. . Disrupting acetyl-lysine recognition: progress in the development of bromodomain inhibitors. J Med Chem 2016;59:1271–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang W, Zheng X, Yang Y, et al. . An overview on small molecule inhibitors of BRD4. Mini Rev Med Chem 2016;16:1403–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, et al. . Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 2010;468:1067–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amorim S, Stathis A, Gleeson M, et al. . Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma: a dose-escalation, open-label, pharmacokinetic, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol 2016;3:e196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berthon C, Raffoux E, Thomas X, et al. . Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with acute leukaemia: a dose-escalation, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol 2016;3:e186–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaudio E, Tarantelli C, Ponzoni M, et al. . Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 (MK-8628) combined with targeted agents shows strong in vivo antitumor activity in lymphoma. Oncotarget 2016;7:58142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albrecht BK, Gehling VS, Hewitt MC, et al. . Identification of a benzoisoxazoloazepine inhibitor (CPI-0610) of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family as a candidate for human clinical trials. J Med Chem 2016;59:1330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siu KT, Ramachandran J, Yee AJ, et al. . Preclinical activity of CPI-0610, a novel small-molecule bromodomain and extra-terminal protein inhibitor in the therapy of multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2017;31:1760–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Picaud S, Da Costa D, Thanasopoulou A, et al. . PFI-1, a highly selective protein interaction inhibitor, targeting BET bromodomains. Cancer Res 2013;73:3336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fish PV, Filippakopoulos P, Bish G, et al. . Identification of a chemical probe for bromo and extra C-terminal bromodomain inhibition through optimization of a fragment-derived hit. J Med Chem 2012;55:9831–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medina FG, Marrero JG, Macias-Alonso M, et al. . Coumarin heterocyclic derivatives: chemical synthesis and biological activity. Nat Prod Rep 2015;32:1472–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emami S, Dadashpour S. Current developments of coumarin-based anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. Eur J Med Chem 2015;102:611–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dandriyal J, Singla R, Kumar M, Jaitak V. Recent developments of C-4 substituted coumarin derivatives as anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem 2016;119:141–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ristic MN, Radulovic NS, Dekic BR, et al. . Synthesis and spectral characterization of asymmetric azines containing a coumarin moiety: the discovery of new antimicrobial and antioxidant agents. Chem Biodivers 2018;16:e1800486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu Y, Shen Y, Wu X, et al. . Synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarin derivatives containing imidazole skeleton as potential antibacterial agents. Eur J Med Chem 2018;143:958–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morsy SA, Farahat AA, Nasr MNA, Tantawy AS. Synthesis, molecular modeling and anticancer activity of new coumarin containing compounds. Saudi Pharm J 2017;25:873–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leal LK, Ferreira AA, Bezerra GA, et al. . Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activities of Brazilian medicinal plants containing coumarin: a comparative study. J Ethnopharmacol 2000;70:151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Squadrito F, Altavilla D, Campo GM, et al. . Cloricromene, a coumarine derivative, protects against lethal endotoxin shock in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1992;210:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boerner D, Metz K, Eberhardt R. Acceptability, safety and efficacy of picumast dihydrochloride on long-term use in patients with perennial bronchial asthma. Arzneimittelforschung 1989;39:1372–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morris GK, Mitchell JR. Warfarin sodium in prevention of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with fractured neck of femur. Lancet 1976;2:869–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hadler MR, Redfern R, Rowe FP. Laboratory evaluation of difenacoum as a rodenticide. J Hyg (Lond) 1975;74:441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu Y, Stumpfe D, Bajorath J. Recent advances in scaffold hopping. J Med Chem 2017;60:1238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ho SY, Alam J, Jeyaraj DA, et al. . Scaffold hopping and optimization of maleimide based porcupine inhibitors. J Med Chem 2017;60:6678–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Magalhaes J, Franko N, Annunziato G, et al. . Discovery of novel fragments inhibiting O-acetylserine sulphhydrylase by combining scaffold hopping and ligand-based drug design. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2018;33:1444–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Floresta G, Rescifina A, Marrazzo A, et al. . Hyphenated 3D-QSAR statistical model-scaffold hopping analysis for the identification of potentially potent and selective sigma-2 receptor ligands. Eur J Med Chem 2017;139:884–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuo W, Bollier M, Leleu-Chavain N, et al. . Development of novel oxazolo[5,4-d]pyrimidines as competitive CB2 neutral antagonists based on scaffold hopping. Eur J Med Chem 2018;146:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Luca L, Ferro S, Morreale F, et al. . Fragment hopping approach directed at design of HIV IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2013;28:1002–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blaquiere N, Castanedo GM, Burch JD, et al. . Scaffold-hopping approach to discover potent, selective, and efficacious inhibitors of NF-κB inducing kinase. J Med Chem 2018;61:6801–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schrodinger L. Schrodinger software suite. New York: Schrödinger, LLC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kontoyianni M, McClellan LM, Sokol GS. Evaluation of docking performance: comparative data on docking algorithms. J Med Chem 2004;47:558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang Y, Yang S, Jiao Y, et al. . An integrated virtual screening approach for VEGFR-2 inhibitors. J Chem Inf Model 2013;53:3163–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]