Abstract

Site-specific chemical modification of proteins can assist in the study of their function. Furthermore, these methods are essential to develop biologicals for diagnostic and therapeutic use. Standard protein engineering protocols and recombinant expression enable the production of proteins with short peptide tags recognized by enzymes capable of site-specific modification. We report here the application of two enzymes of orthogonal specificity, sortase A and butelase 1, to prepare non-natural C-to-C fusion proteins. Using these enzymes, we further demonstrate site-selective installation of different chemical moieties at two sites in a full-size antibody molecule.

TOC graphic

Protein modification technology continues to evolve and improve.1 Protein conjugates prepared through chemical modification enable applications difficult to achieve with conventional protein expression techniques. Such conjugates range from simple imaging agents and pegylated proteins to more complex bioconjugates such as antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) and unnatural C-to-C and N-to-N fusion proteins.

The most widely used approach relies on cysteine functionalization chemistry. Introduction into a protein sequence of an unpaired cysteine renders the method mostly site-specific, while modification of its native counterpart can yield heterogeneous mixtures.2,3 To avoid this issue, site-specific incorporation of an unnatural amino acid into the protein is possible, but this requires manipulation of the genetic code, involves substantial optimization and therefore adjustments on a case by case basis.4–7 A further alternative consists of complete synthesis of the polypeptide of interest (POI) by chemical means, or the combination of various segments through chemical ligation. Although this approach enables site-specific incorporation of the desired modifications, such technologies are limited by the size of the POI: target POIs are usually limited to 250 AA or less.8–12

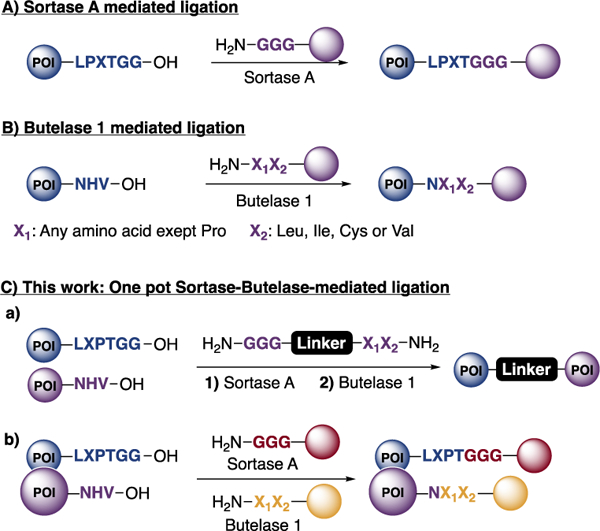

We and others have used a peptide ligase, sortase A, for a variety of protein modifications13–18 Sortase A recognizes a short amino acid sequence, LPXTGG, where X is any amino acid except proline. To this sequence, Sortase A will ligate a peptide that contains an N-terminal oligo-glycine stretch, equipped at its C-terminus with any cargo of choice. The LPXTGG recognition motif is easily incorporated into a POI (Scheme 1A) and is generally placed at or near the C-terminus. Sortase-mediated labeling is robust and finds use in a broad range of applications. Tam and coworkers discovered another ligase, butelase-1, in the seed pods of the plant Clitoria ternatea, purified it, and used it for the modification and cyclization of peptides as well as proteins.19–23 Compared to sortase-A, butelase-1 obeys a distinct set of recognition rules. Butelase-1 also has a much higher turnover number. Butelase 1 recognizes a AsnHisVal (NHV) motif, which it ligates to incoming nucleophiles composed of two amino acids to which a cargo of choice may be attached, provided two rules are followed. The N-terminal residue can be any one except proline and the n-1 terminal residue must be a Cys, Ile, Leu or Val (Scheme 1B).

Scheme 1.

Sortase A and Butelase 1 ligation mechanisms and our work described in this paper.

The distinct rules obeyed by these ligases allows a combination of sortase A and butelase 1 in a single reaction to prepare unnatural C-to-C fusions of two different proteins and to label proteins at two distinct sites in a one-pot reaction (Scheme 1C).

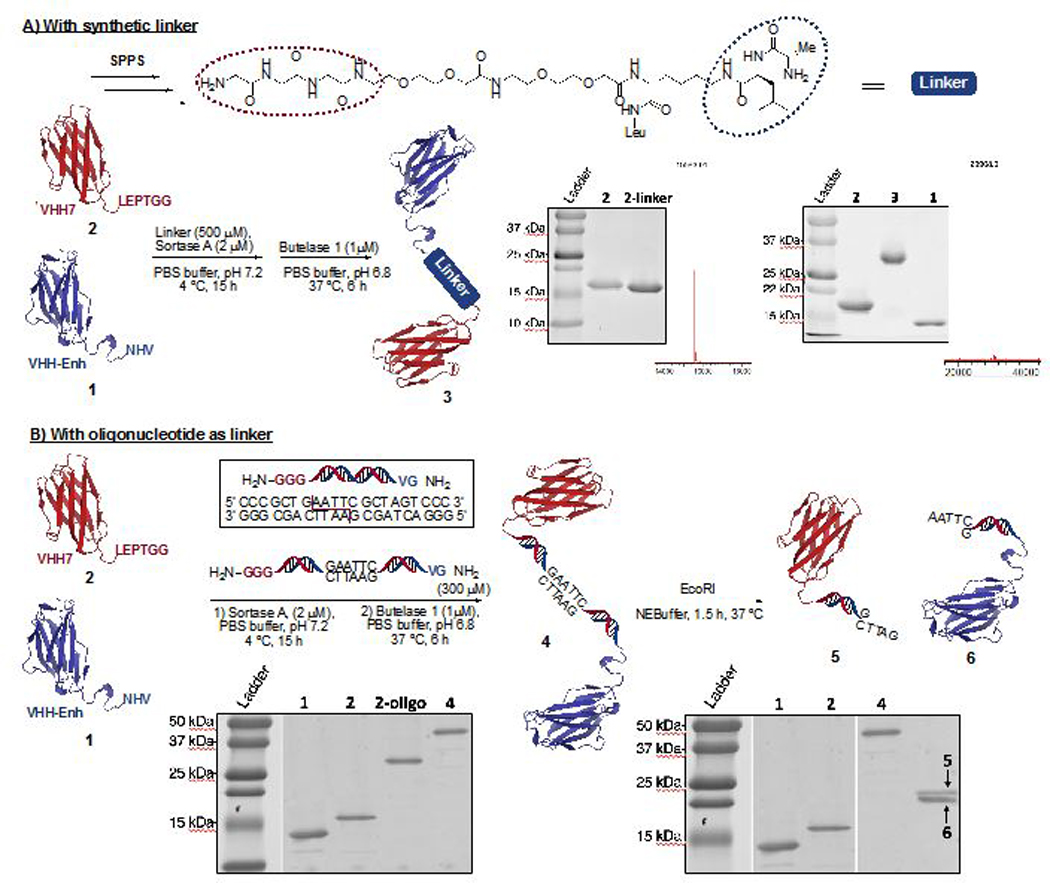

VHHs, also called nanobodies, are small proteins (~14 kDa), that correspond to the antigen binding domain of heavy chain-only camelid antibodies. They are the smallest antibody fragments that retain antigen recognition. We used two such VHHs: VHH7, which recognizes class II MHC products (MHC II) and VHH-Enh, which recognizes eGFP. Generally, the production of bispecific antibodies or their derivatives is a desirable goal from the perspective of therapeutic applications. In this paper, we chose two VHHs of different specificity as a proof-of-concept. These VHHs were modified to carry the desired motifs: VHH7 bears the LPETGG motif at the C-terminus, while VHH-Enh has the NHV motif at the C-terminus. We synthesized a two-headed, PEG-based linker compatible with both sortase A and butelase-1 by standard SPPS (Figure 1A). VHH7 (75 μM) was incubated at 4 ºC with the linker (500 μM) and sortase A (2 μM) for 15 hours. Analysis by mass spectrometry of the reaction mixture showed no remaining His-tagged VHH7, indicating full conversion for the first ligation. The His-tagged sortase was removed by depletion on Ni-NTA agarose beads and remaining free linker was removed from the ligation product through centrifugation-based size exclusion or alternatively by dialysis. To the ligated product (250 μM) VHH-Enh (25 μM) and butelase 1 (1.0 μM) were added and incubated at 37 ºC for 6 hours with agitation. The excess of starting material is necessary in order to reach complete conversion. The reaction mixture was purified either by FPLC or by centrifugation-based size exclusion to afford the desired product in an overall yield of ~30%. The different steps of the reaction were monitored by SDS PAGE (Figure 1A) and mass spectrometry. Only using sortase A and a two-headed linker with a sortase nucleophile, i.e. (Gly)n, would not be compatible with this scheme, as it would have uncontrollably produced a mixture of homodimers and the desired heterodimer.

Figure 1.

C-C protein fusion using sortase A and butelase 1. A) Using a Peg-based linker synthesized by solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). The intermediate and the final product were identified by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry. [M+H]+ intermediate, calc: 15581.55, obs: 15583.01. [M+H]+ dimer, calc:29905.35, obs: 29908.01 B) Using a double stranded oligonucleotide-based linker. The resulting construct was incubated with EcoRI to cleave the heterodimer as verified by SDS-PAGE.

We next altered the properties of the linker that connects the two ligase recognition motifs. Double-stranded oligonucleotides can serve as a rigid linker24 to enforce distance constraints not easily achievable by more flexible PEG spacers. The linker design further included an EcoRI recognition motif to enable enzymatic cleavage of the protein1-DNA-protein2 adduct and release of the protein monomers. Complementary single strand oligonucleotides were synthesized on a solid support. Fmoc-Gly-Gly-Gly-OH was attached to one strand and Fmoc-Gly-Val-OH to the other. Cleavage off the resin and purification using standard purification protocols afforded the two desired strands in excellent purity. Simple annealing yielded the linker containing the DNA duplex. (Figure 1B)

We followed the protocol as described (Figure 1A), with the modification that the unreacted DNA linker was removed using a dialysis cassette with a 20 kDa cut off. After adding butelase 1 and VHH-Enh to linker-conjugated VHH7 and incubating the reaction mixture at 37 ºC for 6 hours, the solution was dialyzed using a membrane with a 30 kDa cut off or purified by FPLC. The desired product as observed by SDS-PAGE was obtained in an overall yield of ~25% (Figure 1B), with no detectable oligonucleotide remaining.

We demonstrated cleavage of this asymmetric dimer by incubation with EcoRI. After 1.5 hours at 37 ºC the reaction mixture was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. We observed a single polypeptide of the expected molecular weight. This result establishes that the desired C-to-C fusion protein had been obtained and that it was possible to cleave the protein-bound linker using a restriction enzyme (Figure 1B). Obviously, length and sequence of the DNA duplex linker can be varied at will to enable the use of different restriction enzymes and to arrive at various distance constraints between the entities newly connected.

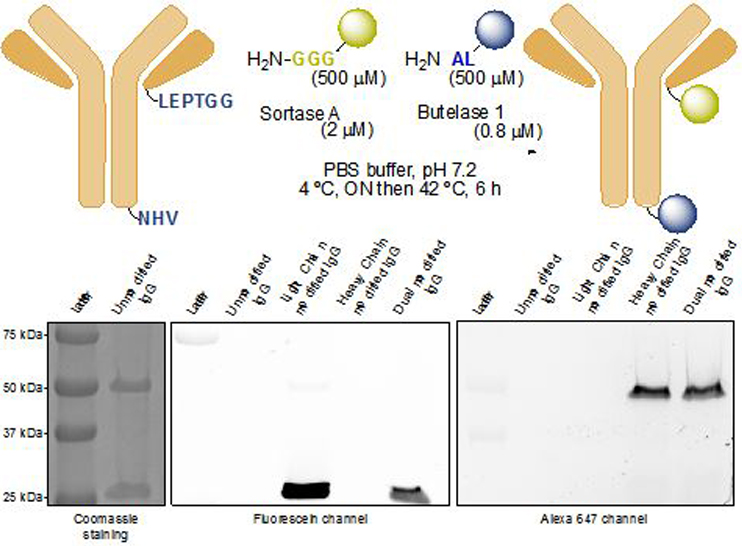

We next explored the possibility of site-specific labeling of a single multi-subunit protein at two positions in a one-pot reaction. Because both sortase A and butelase 1 target sequence motifs at or near the C-terminus of the POI, dual labeling of a single polypeptide would require a different approach.25 Immunoglobulins are composed of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains, held together by disulfide bonds and by non-covalent interactions and are thus an ideal target for our method. Although there are examples in the literature of dually modified antibodies, the methods used are all based on maleimide and succinimidyl ester chemistry, leading to uncontrolled modification.26–28 unless an unpaired cysteine residue is engineered into the antibody. We modified an IgG1 molecule29, 30 so that it contained a LPETGG motif at the C-terminus of the κ (light) chain and an NHV motif at the C-terminus of the γ1 (heavy) chain. We designed two different probes, an oligo-glycine peptide bearing 5,6-carboxyfluorescein (5,6-FAM) at its C-terminus and an alanine-leucine peptide bearing the AlexaFluor 647 fluorescent dye at its C-terminus. IgG1 (10 μM) was incubated with the GGG-FAM (500 μM), the AL-Alexa (500 μM), sortase A (2 μM) and butelase 1 (0.8 μM). The ligation mixture was incubated first at 4 ºC for 15 hours followed by incubation at 37 ºC for 4 hours. Simple centrifugation-based size exclusion was sufficient to remove unincorporated dyes to obtain pure dually modified antibody.

Analysis by SDS-PAGE and examination of the gel using the appropriate excitation and fluorescence emission channels showed that the two chains were each selectively modified with the desired probe.

We thus successfully and selectively labeled a full-size IgG1 in a one-pot reaction (Figure 2). Absorption spectroscopy showed an average of 1.92 mole of FAM per mole of protein, corresponding to a 96% conversion for sortase-mediated light chain labeling, and an average of 1.97 mole of Alexa647 per mole of protein, corresponding to 98% labelling of the heavy chain using butelase 1.

Figure 2.

One-pot dual modification of a full-sized antibody using sortase A and butelase 1. The modified heavy and light chains were detected by SDS-PAGE using the appropriate fluorescence excitation and emission channels.

In summary, the use of two orthogonal enzymes, sortase A and butelase 1, allows straightforward preparation of C-to-C fusion proteins, using either PEG-based or oligonucleotide-based two-headed linkers. We further describe two-site modification of an IgG1 protein in a one-pot reaction. The small size of the two enzyme recognition motifs, LPETGG and NHV, in addition to the simple steps required to incorporate them into any desired POI sequence, make this methodology convenient for both chemists and biologists. The use of linkers of different length should allow enforcement of inter- and intra-molecular distance constraints that affect the molecular properties of proteins thus modified. When using DNA as the linker, any such constraints may be relieved by simple enzymatic cleavage, using restriction enzymes that obviously do not target the protein moieties themselves. Finally, the possibility to selectively attach two distinct molecules to a full-size monoclonal antibody in a one-pot reaction holds promise for the development of complex antibody-drug conjugates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T. J. H. is the recipient of an Early Postdoc Mobility fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). A part of this work (D.R.L and A.C) was supported by the NIH grant R35 GM118062 and HHMI. We also would like to thank the grant AcRF Tier 3 funding MOE 2016-T3–1-003.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Detailed materials and methods, supplementary figures and tables (PDF file).

The authors declare no competing financial interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Boutureira O, Bernardes GJL (2015) Advances in Chemical Protein Modification. Chem. Rev. 115, 2174–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckley NS, Lazzareschi KP, Chih H-W, Sharma VK, Flores HL, (2013) Investigation into temperature-induced aggregation of an antibody drug conjugate. Bioconj. Chem. 24,1674–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamblett KJ, Senter PD, Chace DF, Sun MM, Lenox J, Cerveny CG, Kissler KM, Bernhardt SX, Kopcha AK, Zabinski RF et al. (2004) Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 7063–7070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim CH, Axup JY, Schultz PG (2013) Protein conjugation with genetically encoded unnatural amino acids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 17, 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brustad EM, Lemke EA, Schultz PG, Deniz AA (2008) A general and efficient method for the site-specific dual-labeling of proteins for single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17664–17665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen DP, Elliott T, Holt M, Muir TW, Chin JW (2011) Genetically encoded 1,2-aminothiols facilitate rapid and site-specific protein labeling via a bio-orthogonal cyanobenzothiazole condensation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11418–11421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Sachdeva A, Cox DJ, Wilf NW, Lang K, Wallace S, Mehl RA, Chin JW (2014) Optimized orthogonal translation of unnatural amino acids enables spontaneous protein double-labelling and FRET. Nat. Chem. 6, 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jbara M, Maity SK, Morgan M, Wolberger C, Brik A, (2016) Total Chemical Synthesis of Phosphorylated Histone H2A at Tyr57 Reveals Insight into the Inhibition Mode of the SAGA Deubiquitinating Module. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 4972–4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang S, Wan Z, Gao Y, Zheng J-S, Wang J, Si Y-Y, Chen X, Qi H, Liu L, Liu W (2016) Total chemical synthesis of photoactivatable proteins for light-controlled manipulation of antigen–antibody interactions. Chem. Sci. 7, 1891–1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi G, Kamo N, Okamoto A (2017) Chemical synthesis of dual labeled proteins via differently protected alkynes enables intramolecular FRET analysis. Chem. Commun. 53, 5918–5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmand TJ, Pattabiraman VR, Bode JW (2017) Chemical Synthesis of the Highly Hydrophobic Antiviral Membrane‐Associated Protein IFITM3 and Modified Variants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12639–12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmand TJ, Murar CE, Bode JW (2014) New chemistries for chemoselective peptide ligations and the total synthesis of proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 22, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antos JM, Miller GM, Grotenbreg GM, Ploegh HL (2008) Lipid Modification of Proteins through Sortase-Catalyzed Transpeptidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130,16338–16343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witte MD, Cragnolini JJ, Dougan SK, Yoder NC, Popp MW, Ploegh HL (2012) Preparation of unnatural N-to-N and C-to-C protein fusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11993–11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi J, Kundrat L, Pishesha N, Bilate A, Theile C, Maruyama T, Dougan SK, Ploegh HL, Lodish HF (2014) Engineered red blood cells as carriers for systemic delivery of a wide array of functional probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10131–10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashidian M, Keliher EJ, Bilate AM, Duarte JN, Wojtkiewicz GR, Jacobsen JT, Cragnolini J, Swee LK, Victoria GD, Weissleder R et al. (2015) Noninvasive imaging of immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6146–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Q, Ploegh HL, Truttmann MC (2017) Hepta-Mutant Staphylococcus aureus Sortase A (SrtA7m) as a Tool for in Vivo Protein Labeling in Caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 664–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antos JM, Truttmann MC, Ploegh HL, (2016) Recent advances in sortase-catalyzed ligation methodology. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 38, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen GKT, Wang S, Qiu Y, Hemu X, Lian Y, Tam JP (2014) Butelase 1 is an Asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nat. Chem. Bio. 10, 732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen GKT, Qiu Y, Cao Y, Hemu X, Liu CF, Tam JP (2016) Butelase-mediated cyclization and ligation of peptides and proteins. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1977–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemu X, Qiu Y, Nguyen GKT, Tam JP (2016) Total Synthesis of Circular Bacteriocins by Butelase 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6968–6971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen GKT, Hemu X, Quek J-P, Tam JP (2016) Butelase‐Mediated Macrocyclization of d‐Amino‐Acid‐Containing Peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 128, 12994–12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bi X, Yin J, Nguyen GKT, Rao C, Halim NBA, Hemu X, Tam JP, Liu C-F (2017) Enzymatic Engineering of Live Bacterial Cell Surfaces Using Butelase 1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 7822–7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills JB, Hagerman PJ (2004) Origin of the intrinsic rigidity of DNA. Nucleic Acid Res. 32, 4055–4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antos JM, Chew G-L, Guimaraes CP, Yoder NC, Grotenbreg GM, Popp MW, Ploegh HL (2009) Site-Specific N- and C-Terminal Labeling of a Single Polypeptide Using Sortases of Different Specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10800–10801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karver MR, Weissleder R, Hiilderbrand SA (2012) Bioorthogonal Reaction Pairs Enable Simultaneous, Selective, Multi‐Target Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 124, 944–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa M, Regino CAS, Seidel J, Green MV, Xi W, Williams M, Kosaka N, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H (2009) Dual-modality molecular imaging using antibodies labeled with activatable fluorescence and a radionuclide for specific and quantitative targeted cancer detection. Bioconj. Chem. 20, 2177–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, Yang Y, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W (2012) Positron Emission Tomography and Optical Imaging of Tumor CD105 Expression with a Dual-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody. Mol. Pharmaceut. 9, 645–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougan SK, Ogata S, Andrew Hu C-C, Grotenbreg GM, Guillen E, Jaenisch R, Ploegh HL (2012) IgG1+ ovalbumin-specific B-cell transnuclear mice show class switch recombination in rare allelically included B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13739–13744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avalos AM, Bilate AM, Witte MD, Tai AK, He J, Frushicheva MP, Thill PD, Meyer-Wentrup F, Theile CS, Chakraborty AK et al. (2014) Monovalent engagement of the BCR activates ovalbumin-specific transnuclear B cells. J. Exp. Med. 211, 365–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.