Abstract

Using syndemics theory as a framework, we explored the experience of men who have sex with men in India in relation to four syndemic conditions (depression, alcohol use, internalised homonegativity and violence victimisation) and to understand their resilience resources. Five focus groups were conducted among a purposive sample of diverse men along with seven key informant interviews with HIV service providers. Participants’ narratives suggested various pathways by which syndemic conditions interact with one another to sequentially or concurrently increase HIV risk. Experiences of discrimination and violence from a range of perpetrators (family, ruffians and police) contributed to internalised homonegativity and/or depression, which in turn led some men to use alcohol as a coping strategy. Stigma related to same-sex sexuality, gender non-conformity and sex work contributed to the production of one or more syndemic conditions. While rejection by family and male regular partners contributed to depression/alcohol use, support from family, regular partners and peers served as resources of resilience. In India, HIV prevention and health promotion efforts among men who have sex with men could be strengthened by multi-level multi-component interventions to reduce intersectional/intersecting stigma, address syndemic conditions, and foster resilience – especially by promoting family acceptance and peer support.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, India, syndemics, HIV risk, resilience, intersecting stigma

Introduction

HIV is concentrated among ‘high risk groups’ in India, a term used by the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) that includes men who have sex with men. Official national average HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men is 4.3% (NACO 2015), although a comprehensive study indicated a weighted average of 7.0% (Solomon et al. 2015) – 15 to 25 times higher than that among the general population (0.26%). A national survey showed that consistent condom use in anal sex among men who have sex with men ranges between 50.4% and 54.3% – depending on the type of male partners – figures that are suboptimal when NACO explicitly aims to have ‘all sexual counters protected by correct and consistent usage of condoms’ (NACO 2017: 343). These high levels of HIV prevalence and inconsistent condom use among men who have sex with men persist despite more than a decade of targeted HIV prevention interventions.

Although HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been shown to be effective in reducing HIV infections (Grant et al. 2014; Fonner et al. 2016) and recommended by the World Health Organization for use by men who have sex with men (WHO 2012), India’s HIV programme does not offer PrEP. The national HIV programme’s key strategy of condom promotion alone, without offering PrEP or addressing associated psychosocial health problems (e.g., depression or alcohol use), seems unlikely to bring about the desired changes in levels of condom use and HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men. The national HIV programme now offers free antiretroviral treatment to all HIV-positive people, regardless of their CD4 cell count. However, the use of ‘treatment as prevention’ among men who have sex with men has limitations given that HIV-positive men face barriers to accessing antiretroviral treatment and one multi-site study among 1146 HIV-positive men who have sex with men documented that only 10% had suppressed viral loads (Mehta et al. 2015).

Syndemic conditions and HIV risk

Syndemics theory (Singer and Clair 2003) may offer a possible explanation for this elevated HIV-related sexual risk among men who have sex with men. In India, men who have sex with men face high levels of psychosocial health problems such as violence victimisation (Chakrapani et al. 2007; Newman et al., 2008; Shaw et al. 2012), problematic alcohol use (Mimiaga et al. 2011; Yadav et al. 2014), and depression (Mimiaga et al. 2013). These psychosocial health problems have been shown to co-occur (Chakarapani et al. 2017a) and reinforce each other – producing synergistic epidemics or syndemics among men who have sex with men. In India, given the unique sociocultural context and criminal law against adult consensual same-sex sexual relations (Sarin 2014), in order to design syndemically-oriented interventions we need to better understand how syndemic conditions lead to HIV risk as well as how syndemics are produced among diverse groups of men who have sex with men.

Multiple forms of stigma

In India, men who have sex with men face multiple forms of stigma. Given that adult consensual same-sex sexuality is criminalised in India, structural and societal stigma related to same-sex or bisexual behaviour is faced by almost all subgroups of men who have sex with men (Chakrapani et al. 2007). Stigma related to gender non-conformity is often faced by feminine-appearing men, especially kothis (Logie et al. 2011). Overt manifestations of these different forms of stigma include verbal, physical and sexual violence by police, ruffians and the male clients of men involved in sex work (e.g., Shaw et al. 2012). Even family members, especially fathers and male siblings, have been reported to physically abuse their same-sex attracted sons or brothers, especially if they are gender variant (Chakrapani and Dhall 2011). Furthermore, men who have sex with men may be stigmatised within their own community for engaging in sex work, for being HIV positive, or for being married to a woman (e.g., Chakrapani and Dhall 2011; Tomori et al. 2016).

Stall, Friedman and Catania (2008) have postulated that social marginalisation and gay-related stigma may be key drivers of syndemics among urban gay men in the USA. However, the relevance of this model in India needs to be explored. Studies from India have shown that stigma related to same-sex sexuality or HIV-related stigma is associated with depression (Logie et al. 2012; Chakrapani et al. 2017b) and sexual risk (Thomas et al. 2012), but there is limited evidence, none from India, on the pathways by which stigma contributes to syndemics and HIV risk (Herrick et al. 2014a; Adam et al. 2017).

Resilience

Resilience, as a protective factor, has been recognised as an important area to be studied (Herrick et al. 2014b). Resilience is now viewed as a multi-faceted concept, and sources of resilience are identified at individual, interpersonal and community levels (Herrick et al. 2014b; Aburn, Gott and Hoare 2016; Woodward et al. 2017). In this paper, we use the definition of resilience by Fergus and Zimmerman (2005): ‘the process of overcoming the negative effects of risk exposure, coping successfully with traumatic experiences, and avoiding the negative trajectories associated with risk’. Several researchers have called for interventions to improve resilience (Kurtz et al. 2012; Herrick et al. 2014b), given the potential complementarity between interventions that address syndemic conditions and those that improve resilience resources in reducing HIV risk. There are few published studies from India that comprehensively examined resilience among men who have sex with men (but see Mimiaga et al. 2015 and Safren et al. 2014 as exceptions).

Study objectives

Qualitative research is well suited to understanding the mechanisms and contexts that increase HIV risk and the nature of resilience resources. Qualitative approaches have been used internationally to understand syndemics (Lyons, Johnson and Garofalo 2013; DiStefano 2016; Adam et al. 2017) and resilience (Lewis 2014; Buttram 2015). In order to identify pathways by which syndemic conditions might increase HIV risk among men who have sex with men in India as well as to guide the design of syndemically-oriented and resilience-based interventions, we conducted a qualitative formative study to elicit experiences and perspectives on syndemic conditions, resilience resources and HIV risk.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in Chandigarh, a city in North India, in collaboration with three non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that undertake targeted HIV interventions among men who have sex with men. These interventions, given their focus on HIV, currently do not sufficiently address psychosocial health problems or syndemic conditions.

Design and Data collection

In 2016, we conducted five focus groups among a purposive sample of men who have sex with men from diverse backgrounds in terms of socioeconomic status, sex work involvement and self-identification: (kothis [feminine/primarily receptive partners in anal sex], panthis/giriyas [masculine/primarily insertive partners], double-deckers [insertive and receptive], and gay- and bisexual-identified men [insertive, receptive or both) (Chakrapani et al. 2007), as the experiences of syndemic conditions and HIV risk may vary across these diverse men who have sex with men.

Eligibility criteria for focus group participation included self-identification as a man who have sex with men (of any sexual identity), aged 18 years and above, and able to provide written informed consent. As the three NGOs served men with diverse identities, and participants were willing to be part of a mixed group (Table 1), each focus group contained a heterogenous sample of men with diverse identities. In addition to focus groups, we conducted seven key informant in-depth interviews with community leaders and NGO staff.

Table 1. Sexual identity and number of participants by focus group.

| Focus group number | Kothi | Double-decker (versatile) | Gay | Bisexual | Giriya/ Panthi | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 5 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| N | 33 | |||||

Based on syndemics theory (Stall, Friedman and Catania 2008) and the existing literature on syndemics and HIV risk (e.g., DiStefano 2016), topic guides for focus groups and key informants focused on key issues faced by participants. These include experiences of stigma, discrimination and violence; sexual life and safer sex practices; mental health, alcohol use, and internalised homonegativity; the use of HIV-related and mental health services; and support systems (resilience resources). Focus group moderators (the first and second authors) used follow-up questions and probes to encourage participants to elaborate on their experiences and to understand the connection between psychosocial health problems and HIV risk.

Each focus group included 6 to 8 men, lasted between 45 to 90 minutes and was conducted in Hindi. Key informants spoke mostly in Hindi but answered certain questions in English. Focus group participants were paid an honorarium of INR 100 to cover their travel expenses. Key informants were not paid.

Data analysis

Focus groups and key informant interviews were summarised in detail after listening to digital audio files. Summaries and excerpts were then coded, with codes derived from syndemics theory, topic guides and the empirical literature. We primarily used framework analysis (Ritchie and Spencer 1994), a form of thematic analysis, with syndemics theory as a broader framework. A priori codes (e.g. stigma, discrimination, violence, depression, alcohol use, condom use) as well as emergent codes (e.g. ‘cheaters’, value on masculinity) were used. We resolved any differences in coding through discussion and consensus (Sparkes 2001; Cohen and Crabtree 2008). We deliberately sought disconfirming evidence (e.g. stories of persons with experiences of discrimination but coping well, with no depression) (Maxwell 2013). We also compared the experiences reported by focus group participants and key informants (source and method triangulation) (Maxwell 2013).

Ethics and data security

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All personal identifiers in illustrative quotes were removed and some personal information has been modified in the illustrative quotes to protect confidentiality. Only pseudonyms were used. The study protocol was approved by the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh.

Findings

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Focus group participants’ (n=33) mean age was 27 years (SD 5.8). About two-thirds had completed education between 8th and 12th grade, and 18.2% had completed college education. Except for three persons (one unemployed and two college students), the others were employed: 36.4% in private companies, 18.2% in voluntary organisations, 27% were self-employed and 9% engaged in sex work. The mean monthly income was INR 10300 (170 USD). About two-thirds (57%) were single. Participants’ self-identifications included: kothi (48%), gay (18%), bisexual (12%), double-decker/versatile (12%), and panthi/giriya (9%) (Table 2). Key informants (n=7) included two project staff from NGOs working with men who have sex with men, three community leaders and two professional counsellors. Six of them had at least five years of experience in working with men who have sex with men and/or in HIV projects.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of focus group participants (n = 33).

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.1 (5.8) |

| Monthly income (INR) | 10300 (5066) |

| n (%) | |

| Highest level of completed education | |

| Elementary (8th grade) | 6 (18.2) |

| High school (10th grade) | 7 (21.2) |

| Higher secondary (12th grade) | 11 (33.3) |

| College degree | 6 (18.2) |

| Diploma | 3 (9.1) |

| Employment | |

| Private company staff | 12 (36.4) |

| Self-employed | 9 (27.3) |

| Voluntary organization staff | 6 (18.2) |

| Sex worker | 3 (9.1) |

| Student | 2 (6.1) |

| Unemployed | 1 (3.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 19 (57.6) |

| Married | 14 (42.4) |

| Primary Identity | |

| Kothi | 16 (48.5) |

| Gay | 6 (18.2) |

| Bisexual | 4 (12.1) |

| Double-decker (versatile) | 4 (12.1) |

| Giriya/Panthi | 3 (9.1) |

Depression and HIV risk

Men noted that anticipated discrimination, including rejection by family members if one’s sexuality was known about, could lead to depression. Participants reported that some same-sex attracted men did not disclose their sexuality and even got married ‘willingly’ to avoid bringing shame to their family. As Rohan, a bisexual-identified man, said:

I may be leading not even double, but triple or even four different lives. One with my family (wife and children), another with my close friends, and another in my workplace. I can’t be open and be myself always.

Participants reported break-up with a long-term male partner as another key reason for depression. Kothis were aware that their panthi/giriya lovers (would eventually leave them for a woman:

Giriyas by their nature will be attracted to women. That’s why we [kothis] like them.

Some of us know that someday it will happen (relationship will end), but others…can’t tolerate if their men leave them’ (Dev, kothi).

Despite this awareness, when the relationship ends some kothis become depressed and even attempt suicide. Contrary to kothis’ belief that giriyas do not love them enough, Uday, a giriya, admitted that he too felt very low after his kothi partner left him for another man: ‘I was worried for several days… My [straight] friends used to tease me for having relation with him, so I did not share my feelings with them’. Thus, among both kothis and giriyas, there is little emotional and psychological support if they face relationship difficulties.

Participants reported that their own or their friends’ suicidal thoughts would be triggered when they attributed the reason for f their problems to their sexuality and felt bad about being a same-sex attracted person. As Karan, a gay man, said:

Had I not been born this way, I would not have to deal with this (break-up with boyfriend) …Finding a male lover is difficult, although you can find many men for sex…And with whom can we share our feelings?

Participants described how some of their friends, even those working in NGOs for men who have sex with men, had attempted suicide by consuming rat poison or ‘sleeping pills’, or by slashing their wrists. A few completed suicides were reported as well – by hanging and by lying on the train tracks. An NGO staff key informant offered a possible explanation:

Not all men [who are ‘out’] can share their feelings openly with other men…The fear that “Others will think of me as weak” may prevent some men from sharing with even close friends.

Participants reported psychological distress secondary to perceived discrimination. A few kothis complained that some private gay party organisers did not allow ‘CDs [cross-dressers] and transgender’, groups that may include feminised kothis. One participant provided a reason for why gay men might have such party rules: ‘Gay men who organise these parties do not want hookers. Some kothis pay the party money and then pick up some men and earn money. Gay men may despise such persons’ (Harjit, gay). Regardless of the reason, these experiences denote divisions within the community based on socioeconomic class, education, sex work involvement and gender expression.

Participants pointed out that even if men were depressed they might pretend to be okay. As Fred, a gay man, said:

After a break-up, my friend wanted to show his ex-boyfriend that life did not end for him… and he is sexy and desired by many men. So, he had sex with a lot of guys – but not always insisting on condom use. It was like revenge.

Here, there was a denial of the need for psychological support but intentional engagement in risky sex as a maladaptive response. Amar, a double-decker-identified man, said, ‘When we get depressed we do not want to always think about what happened to us. So, we need to take things off our mind – by having sex. Otherwise we will remain depressed’.

Alcohol use and HIV risk

Alcohol use was reported as an issue among men who have sex with men, although participants said that most men use alcohol to ‘relax’ or ‘have fun’ rather than become dependent on it. A few men reported lack of family acceptance and subsequent depression as a reason for consuming alcohol. For example, after one gay man disclosed his sexuality, his family members disowned him, and he started drinking to cope:

My family stopped talking to me. It has been three years now. My mother tries to contact me but my brothers…don’t allow me to visit home…Hence I moved to this city… and do sex work… I tried to control my urge to drink. But my roommate is a drinker and I too started drinking regularly (Karan, gay).

In contrast, Veer, a bisexual-identified man said, ‘My family (wife and children) should not get into any trouble because of my drinking. I stopped drinking after my marriage. I am worried about others finding out my sexuality’. Placing importance on his new family and the need to maintain family harmony seemed to have helped this man cope with stress.

Many participants insisted that men use condoms even if they had drunk alcohol, but other participants addressed the role of alcohol in unprotected sex. As Fred, a gay man, said, ‘I drink alcohol once in a while in a month. But then…I start searching for sexual partners… may be if I have sex then I would not bother about condom use’. Thus, his experiences had made him more conscious about not mixing alcohol and sex. Other men reported incidents of unprotected sex after alcohol use. For instance, Dev (kothi) said, ‘After drinking alcohol, if it is moderate [quantity], then men use condoms; but if they think they do not feel any pleasure or [are] getting late [delayed orgasm] then they will remove them’.

Violence victimisation and HIV risk

Participants reported that feminine-appearing males, men in sex work and same-sex attracted youth were particularly prone to violence in various forms – verbal, emotional, physical and sexual. As Chottu, a kothi, said, ‘Some kothis walk matak-matak (in a stereotypical feminine way, with hips swaying). Then others [men on the road] will come to know about them…call them such derogatory names’. To avoid such problems, men may constrain their behaviours that might be seen as feminine when they are in public spaces or in their family homes.

Kothis in sex work seemed to be caught in a double-bind: if they do not behave in a feminine manner then they do not get masculine clients; and if they do, then their sexuality is revealed to thugs and police who may extort money and/or rape them. As Akash, a kothi involved in sex work, said:

The place where I stand regularly for dhanda [sex work] is a beat area for a policeman. He came to know that I am such and such, and he started asking for money. Occasionally he wants sexual favours, too.

Participants reported that in rural areas people were more conservative and intolerant of any indication of femininity in a man, a key reason described by participants for migrating from rural areas to the city. Some kothi participants from rural areas had left their parental home to avoid bringing shame to their family and came to a strange city without money. Engagement in sex work then became a necessity for those who could not find well-paying jobs. But engagement in sex work carries risks too, such as violence from ruffians, police and some male clients. Men in sex work reported that they had clients who were ‘cheaters’ (i.e., who stole their money or cell phone). As a precaution, some men – especially those who use geosocial networking apps to find partners – ask potential partners to first meet them in a public place and go elsewhere with them only after they trust their intentions.

Participants noted that masculine men who have sex with men were often not suspected by the public or police to engage in same-sex sexual behaviours. Navin, a kothi, pointed out that discrimination against giriyas could be subtle: ‘When I go with my man [lover] with whom I live, people look at us strangely. They will ask him “Why you are having a friendship with this guy?” This makes my lover feel very bad’. Bala, a giriya, reported his straight friend outed his same-sex sexual activities to other straight friends who then started looking down upon him: ‘Hopefully, I will grow out of this when I get married’.

Internalised homonegativity and HIV risk

Some men seemed to have internalised negative societal attitudes toward same-sex sexuality. As Tanuj, a kothi, put it, ‘They [society] are right. We deserve to be [mis]treated like this. Nobody will tolerate it if their family member is like this’. Some participants avoided going to family functions because they did not want their relatives to discern their sexual orientation by observing their feminine mannerisms.

Other participants wanted to ‘compensate’ for their ‘fault’ by financially supporting their family members to the extent they could.

I provided money for my sister’s marriage…much more than my elder brothers. We do not want to lose our status in our family. But if they find out this small fault of ours, which is not our own, then they forget all that we have done (Chottu, kothi).

Having heard in a focus group that some men spoke of karma (destiny) and reincarnation, in subsequent focus groups the participants were asked whom they would like to be if they were reincarnated. Some participants wanted to be born as a ‘normal’ man and a few wished to be born as a woman as then it would not be a problem to be attracted or married to a man. Although these responses may reflect experiences of discrimination, they also suggest internalised homonegativity. Participants’ accounts showed connections between internalised homonegativity and depression. For instance, Akash, a kothi, said, ‘Sometimes I feel why God has created me like this… I have cried several times’.

Resilience resources: Family, Male lovers, Peers, and Agencies

Lack of family support had led some participants to leave their villages and come to the city. As they had read in newspapers about gay pride marches, they thought that the city would be gay-friendly; most of them indeed found supportive peers in the city. As Inder, a kothi, said, ‘As soon as I came to the city bus station, I met another kothi who recognised my identity and he took me to his home. Soon I met several kothis and we became friends’.

Many men described needing to choose between support from their birth family or community peers. Rohan, a bisexual-identified man, not wanting to lose his wife and children, decided not to socialise with other men who have sex with men so that he could keep his family life separate from his sexual life with men:

I am emotionally attached to my family. I have sex [with other men] and that’s all. No friends, except him (pointing to a masculine person who brought him to the focus group) who will not be suspected (as being gay) if he comes to my home…Other [feminine men] may create problems.

He also reported always using condoms with other men as he did not want to infect his wife. Thus, in the absence of peer support, emotional attachment to his family motivated him to practise safer sex.

Participants offered mixed responses when asked whether and how their male regular partners served as a source of support. One participant remarked, ‘Lovers are the sources of our problems’, to which others laughed. ‘Nearly 60% of panthis are supported by the earnings of kothis’ was the consensus in one focus group. Many of older kothis criticised younger kothis for being ‘too romantic’ and attempting to commit suicide if a relationship with their giriya lover broke up. Other kothis reported that their male lovers were supportive in terms of offering money and a residence to them.

NGOs could serve as another source of emotional support. Participants mentioned that community events at NGO drop-in centres were fun and helped in meeting new friends. However, both participants and key informants noted that certain groups of men who had sex with men did not visit drop-in centres. Raj, a kothi, said,

‘Gays and DDs [double-deckers] don’t come. They will say “We don’t do thaali (a particular style of clapping hands) like you [kothis] do. They don’t want to be seen with kothis’.

Thus, concerns about disclosure of sexuality, and socioeconomic class differences, prevent diverse segments of men who have sex with men from coming together and supporting one another, and also hinder access to HIV-related services.

Discussion

Overall, this study contributes to the limited literature on syndemics among sexual minorities in South Asia (Guadamuz et al. 2014; Chakrapani et al. 2017a). Previous quantitative research among men who have sex with men in India has documented the presence of syndemic conditions (Chakrapani et al. 2017a). This study indicates the processes by which experiences of stigma, discrimination and violence may lead to depression, alcohol use and internalised homonegativity, how these conditions are interconnected, and how together they may increase risk of HIV infection. Overall, the findings suggest that syndemically-oriented interventions could significantly reduce HIV risk when combined with individual level interventions that promote condom use.

Stigma and syndemics production

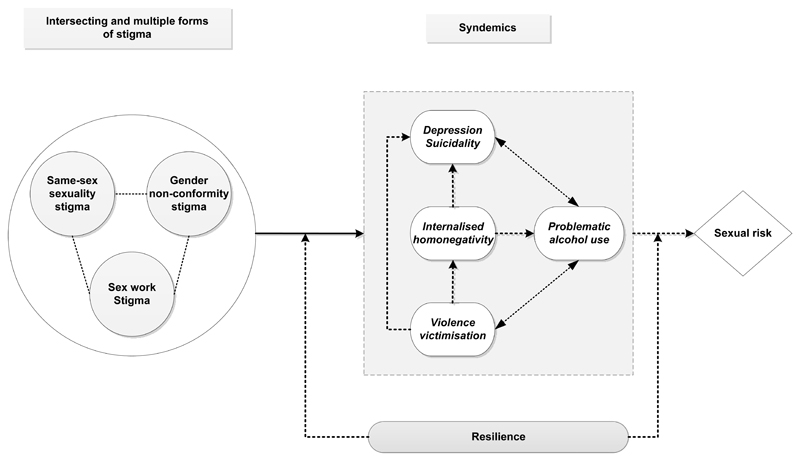

In line with Stall, Friedman and Catania’s (2008) syndemics production model, our study found that sexuality-related stigma and gender non-conformity stigma may contribute to the production of syndemic conditions. However, findings also suggested that supportive communities of men who have sex with men in the city (which largely do not exist in most rural areas) could potentially counter the effects of stress imposed by migration from rural areas and serve as a resilience resource (Woodward et al. 2017). The earlier syndemics production model primarily focused on gay-related stigma, although it alluded to intersecting forms of stigma. The present study indicates the presence of multiple intersecting kinds of stigma related to same-sex sexuality, gender non-conformity, sex work involvement, and socioeconomic status among men, similar to the intersectional stigma reported in other studies among vulnerable communities (Logie et al. 2011; Mueller et al. 2015). The presence of multiple intersecting forms of stigma may increase the chances of one or more syndemic conditions (see Figure 1) and future studies need to explore these dynamics.

Figure 1. The influence of stigma and syndemics on sexual risk: a conceptual model based on qualitative findings, guided by syndemics theory.

Note: The interconnections between three types of stigma are shown with dotted lines. The directions of the arrows in the syndemics box are based on empirical data. Resilience can influence the effect of stigma on syndemic conditions, and that of syndemics on sexual risk.

Syndemics and HIV risk

Studies from India have mostly shown associations between a singular syndemic conditions and HIV-related risk—for instance, an association between HIV-related sexual risk and depression (Mimiaga et al. 2013), sexual violence (Shaw et al. 2012) or alcohol use (Yadav et al. 2014) with. In the present study, we identified the processes by which multiple syndemic conditions may influence one another, and how they may lead to HIV-related sexual risk. For example, experiences of discrimination and violence from a range of perpetrators contributed to internalised homonegativity and/or depression, which some men reported as leading them to use alcohol as a coping strategy. Similar to our findings, qualitative studies from developed countries have also documented syndemic links between HIV-related sexual risk among men who have sex with men and depression, substance abuse and violence (DiStefano 2016; Edelman et al. 2016; Adam et al. 2017; Chuang, Newman and Li, forthcoming).

Role of resilience

Our findings showed that family members could serve as an important source of support irrespective of whether men had disclosed their sexuality or not. The importance that men place on retaining their ties with their family members was evident, which may be common to primarily collectivistic cultures (Srivastava and Singh 2015) in which exercising individual rights (e.g. to choose one’s sexual or life partner) may be seen as a luxury, if not selfishness (Ojanen et al. 2018). Accordingly, some men may give priority to maintaining family harmony by choosing to not to disclose their sexuality or agreeing to family members’ requests that they not disclose their sexuality to others (Chakrapani and Dhall 2011).

It is not clear whether being closeted to maintain family harmony confers any benefit over being ‘out’ and gaining support from same-sex attracted peers. However, as this study’s findings indicate, some men try to balance acting on their same-sex sexual desires with their perceived responsibility to their family by trying to keep their family and sexual lives separate. A survey of gay men in the USA (Pachankis, Cochran and Mays 2015) found that, after controlling for age of coming out, gay men who were in the closet had lower odds of having experienced major depressive symptoms when compared to gay men who had come out recently or for several years. While we are not suggesting that men who have sex with men in India should remain closeted, future studies in India need to further explore the relationship between outness, family support, and psychological distress to better understand whether, and in what ways and contexts, being closeted or out are beneficial to the mental health of men. That which is deemed resilient in a Western context may not be so in India; rather, explorations of men’s different paths and adaptive strategies for navigating their sexuality and gender expression in India are needed. Future interventions, building on evidence from the present study, should focus on promoting further resources of resilience, such as family and peer support, in addition to self-acceptance.

We found challenges in making use of and strengthening community resilience. Non-acceptance of kothis, both because of their feminine gender presentation and their lower socioeconomic status, among certain social circles of educated gay-identified men reflect the implicit value placed on masculinity by the gay community itself (Cohen 2006; Shahani 2008) as well as differences based on socioeconomic and sex work involvement. Masculinity is also valued by kothis themselves, given that they prefer masculine giriyas, and violence from their masculine partners is then seen as a proof of their being a ‘real man’. Future strategies to improve community resilience need to take into account the socioeconomic class differences and hegemonic masculinity that affect solidarity among diverse men who have sex with men.

Implications for policy and practice

Historically, India’s National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) has claimed that its responsibility is HIV prevention and therefore services that are not seen as directly related to HIV, such as those addressing syndemic conditions (e.g. depression, alcohol use), are not part of the national HIV programme’s work. Only in the most recent version of the NACO training manual for counsellors (NACO n.d.), have ‘mental/emotional health issues’ been added, but with no discussion of other syndemic conditions such as problematic alcohol use or internalised homonegativity. Targeted HIV intervention projects often have a crisis response team that attends to men who face violence from police or thugs, but there are no systematic or long-term programmes to reduce stigma or to prevent the discrimination and violence faced by men who have sex with men at the local, state or national levels. Given that multiple forms of stigma drive the production of syndemic conditions, which in turn increase HIV risk, stigma reduction efforts need to be intensified. Such efforts include the decriminalisation of adult consensual same-sex relationships and the sensitisation of health care providers and society to sexual and gender minority communities. Culturally appropriate supportive counselling needs to be offered to address internalised homonegativity and to promote resilient coping behaviours. These syndemically-oriented and resilience framework-based strategies could advance the mental and physical health of men who have sex with men, including reduction in HIV risk.

Limitations

As most participants were recruited through NGOs working with men who have sex with men, the experiences of men who are not affiliated to NGOs may be different, and perhaps more detrimental to their health. To increase the applicability of these findings, however, we did include diverse men who have sex with men and used both methods and source triangulation to obtain diverse perspectives. While a few focus group participants may have been HIV-positive but did not report it, we did not elicit information specifically on how syndemic conditions may affect HIV-positive men who have sex with men, which should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that stigma related to same-sex sexuality, gender non-conformity, and sex work either alone or in combination contribute to the production of one or more syndemic conditions, which in turn may contribute to increased HIV risk. The role of intersectional/intersecting forms of stigma in producing syndemic conditions need to be further explored. Future research, using prospective cohort designs and mixed methods, might usefully advance our understanding of the causal pathways by which syndemic conditions mutually reinforce one another, especially with respect to risk for HIV infection.

Syndemically-oriented (Gonzalez-Guarda 2013) and resilience-based interventions (Safren et al. 2014) have the potential to reduce HIV risk beyond individual-focused condom promotion interventions. HIV prevention and health promotion efforts among men who have sex with men could be strengthened by introducing programmes to reduce multiple intersecting stigmas; incorporating screening for and addressing syndemic conditions (such as depression and alcohol use) in existing individual-focused HIV prevention interventions; taking steps to prevent violence rather than only mitigating the impact of violence; and fostering resilience by increasing support from families and solidarity within communities of men who have sex with men in India.

Acknowledgements

Venkatesan Chakrapani was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Senior Fellowship (IA/CPHS/16/1/502667). We thank our partner agencies – the Servants of the People Society, Chandigarh, and branch offices of the Family Planning Association of India and the Indian Public Health Association in Chandigarh – for their support in the implementation of this study. We gratefully acknowledge the input and support of Vanita Gupta, Project Director of Chandigarh AIDS Control Society.

References

- Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is Resilience? An Integrative Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016;72(5):980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam BD, Hart TA, Mohr J, Coleman T, Vernon J. HIV-related Syndemic Pathways and Risk Subjectivities among Gay and Bisexual Men: A Qualitative Investigation. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2017;19(11):1254–1267. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1309461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Dhall P. Family Acceptance among Self-identified Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) and Transgender People in India. Mumbai: Family Planning Association of India; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Logie CH, Samuel M. Syndemics of Depression, Alcohol use, and Victimisation, and Their Association with HIV-related Sexual Risk among Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in India. Global Public Health. 2017a;12(2):250–265. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1091024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, McLuckie A, Melwin F. Structural Violence against Kothi-identified Men who have Sex with Men in Chennai, India: a Qualitative Investigation. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2007;19(4):346–364. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Vijin PP, Logie CH, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Sivasubramanian M, Samuel M. Understanding How Sexual and Gender Minority Stigmas Influence Depression among Trans Women and Men who have Sex with Men in India. LGBT Health. 2017b;4(3):217–226. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang DM, Newman PA, Li A. Syndemic factors and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Taiwan. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Buttram ME. The Social Environmental Elements of Resilience among Vulnerable African American/black Men who have Sex with Men. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2015;25(8):923–933. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2015.1040908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. The Kothi Wars: AIDS Cosmopolitanism and the Morality of Classification. In: Adams V, Leigh Pigg S, editors. Sex in Development: Science, Sexuality, and Morality in Global Perspective. Durham: Duke University Press; 2006. pp. 269–303. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative Criteria for Qualitative Research in Health care: Controversies and Recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(4):331–339. doi: 10.1370/afm.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano AS. HIV’s Syndemic Links with Mental Health, Substance use, and Violence in an Environment of Stigma and Disparities in Japan. Qualitative Health Research. 2016;26(7):877–894. doi: 10.1177/1049732315627644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman EJ, Cole CA, Richardson W, Boshnack N, Jenkins H, Rosenthal MS. Stigma, Substance use and Sexual Risk Behaviors among HIV-infected Men who have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;3:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent Resilience: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonner VA, Dalgish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, Rodolph M, Hodges-Mameletzis I, Grant RM. Effectiveness and Safety of Oral HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis for all Populations. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973–83. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM. Pushing the Syndemic Research Agenda Forward: A Comment on Pitpitan et al. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;45(2):135–136. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, Hosek S, et al. Uptake of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, Sexual Practices, and HIV Incidence in Men and Transgender Women who have Sex with Men: A Cohort Study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(9):820–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadamuz TE, McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, Thienkrua W, Varangrat A, Chaikummao S, Sangiamkittikul A, Stall RD, van Griensven F. Psychosocial Health Conditions and HIV Prevalence and Incidence in a Cohort of Men who have Sex with Men in Bangkok, Thailand: Evidence of a Syndemic Effect. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18(11):2089–2096. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Egan J, Schrager S, Kipke M. Pathways Towards Risk: Syndemic Conditions Mediate the Effect of Adversity on HIV Risk Behaviors among Young Men who have Sex with Men (YMSM) Journal of Urban Health. 2014a;91(5):969–982. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9896-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a Research Framework and as a Cornerstone of Prevention Research for Gay and Bisexual Men: Theory and Evidence. AIDS & Behavior. 2014b;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SP, Buttram ME, Surratt HL, Stall RD. Resilience, Syndemic Factors, and Serosorting Behaviors among HIV-positive and HIV-negative Substance-using MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2012;24(3):193–205. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis NM. Rupture, Resilience, and Risk: Relationships between Mental Health and Migration among Gay-identified Men in North America. Health & Place. 2014;27:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, Gender, Race, Sexual Orientation, and Sex Work: A Qualitative Study of Intersectional Stigma Experienced by HIV-positive Women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(11):e1001124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie CH, Newman PA, Chakrapani V, Shunmugam M. Adapting the Minority Stress Model: Associations Between Gender Non-Conformity Stigma, HIV-related Stigma and Depression among Men who have Sex with Men in South India. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(8):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons T, Johnson AK, Garofalo R. "What Could Have Been Different": A Qualitative Study of Syndemic Theory and HIV Prevention among Young Men who have Sex with Men. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. 2013;12:3–4. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2013.816211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: an interactive approach. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SH, Lucas GM, Solomon S, Srikrishnan AK, McFall AM, Dhingra N, Nandagopal P, Kumar MS, Celentano DD, Solomon SS. HIV Care Continuum among Men who have Sex with Men and Persons who inject Drugs in India: Barriers to Successful Engagement. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(11):1732–41. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Sivasubramanian M, Mayer KH, Anand VR, Safren SA. Psychosocial Risk Factors for HIV Sexual Risk among Indian Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1109–1113. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.749340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Closson EF, Thomas B, Mayer KH, Betancourt T, Menon S, Safren SA. Garnering an In-depth Understanding of Men who have Sex with Men in Chennai, India: a Qualitative Analysis of Sexual Minority Status and Psychological Distress. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(7):2077–2086. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Thomas B, Mayer KH, Reisner SL, Menon S, Swaminathan S, Periyasamy M, Johnson CV, Safren SA. Alcohol use and HIV Sexual Risk among MSM in Chennai, India. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2011;22(3):121–125. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller AS, James W, Abrutyn S, Levin ML. Suicide Ideation and Bullying among US Adolescents: Examining the Intersections of Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Race/ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(5):980–985. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NACO. National Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance (IBBS) 2014-15: High Risk Groups. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NACO. Annual Report 2016-17. National AIDS Control Organization. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NACO. Training Module for Counsellors in Targeted Interventions for Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO); (n.d.) [Google Scholar]

- Newman PA, Chakrapani V, Cook C, Shunmugam M, Kakinami L. Correlates of Paid Sex among Men who have Sex with Men in Chennai, India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;84(6):434–438. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen TT, Newman PA, Ratanashevorn R, de Lind van Wijngaarden JW, Tepjan S. Whose Paradise? An Intersectional Perspective on Mental Health and Gender/sexual Diversity in Thailand. In: Nakamura N, Logie C, editors. LGBT Mental Health: Global Perspectives and Experiences. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2018. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, Mays VM. The Mental Health of Sexual Minority Adults in and out of the Closet: A Population-based Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(5):890–901. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analysing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Thomas BE, Mayer KH, Biello KB, Mani J, Rajagandhi V, Periyasamy M, Swaminathan S, Mimiaga MJ. A Pilot RCT of an Intervention to Reduce HIV Sexual Risk and Increase Self-acceptance among MSM in Chennai, India. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18(10):1904–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin A. On Criminalisation and Pathology: a Commentary on the Supreme Court Judgment on Section 377. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 2014;11(1):5–7. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2014.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahani P. Gay Bombay: Globalization, Love and Be(longing) in Contemporary India. London: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SY, Lorway RR, Deering KN, Avery L, Mohan HL, Bhattacharjee P, Reza-Paul S, et al. Factors Associated with Sexual Violence Against Men who have Sex with Men and Transgendered Individuals in Karnataka, India. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e31705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-social Context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17(4):423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon SS, Mehta SH, Srikrishnan AK, Vasudevan CK, McFall AM, Balakrishnan P, Anand S, Nandgopal P, Ogburn EL, Laeyendecker O, Lucas GM, et al. High HIV Prevalence and Incidence among MSM Across 12 Cities in India. AIDS. 2015;29(6):723–31. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes AC. Myth 94: Qualitative Health Researchers will agree about Validity. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(4):538–552. doi: 10.1177/104973230101100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Singh P. Psychosocial Roots of Stigma of Homosexuality and its Impact on the lives of Sexual Minorities in India. Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2015;3(8):128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Friedman M, Catania JA. Interacting Epidemics and Gay Men's Health: A Theory of Syndemic Production among Urban Gay Men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal Opportunity: Health Disparities Affecting Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Perry NS, Swaminathan S, Safren SA. The Influence of Stigma on HIV Risk Behavior among Men who have Sex with Men in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):1401–6. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.672717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomori C, McFall AM, Srikrishnan AK, Mehta SH, Solomon SS, Anand S, Vasudevan CK, Solomon S, Celentano DD. Diverse Rates of Depression among Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) Across India: Insights from a Multi-Site Mixed Method Study. AIDS & Behavior. 2016;20(2):304–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidance on Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for Serodiscordant Couples, Men and Transgender Women who have Sex with Men at high risk of HIV: Recommendations for Use in the Context of Demonstration Projects. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Regina JB, Amy KM, David WP. Identifying Resilience Resources for HIV Prevention among Sexual Minority Men: A Systematic Review. AIDS & Behavior. 2017;21(10):2860–2873. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav D, Chakrapani V, Goswami P, Ramanathan S, Ramakrishnan L, George B, Sen S, Subramanian T, Rachakulla H, Paranjape RS. Association Between Alcohol use and HIV-related Sexual Risk Behaviors among Men who have Sex with Men (MSM): Findings from a Multi-Site Bio-behavioral Survey in India. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18(7):1330–1338. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0699-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]