Abstract

Objective:

To examine changes in personality in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia as observed by family members using both new data and a meta-analysis with the published literature.

Design:

Current and retrospective personality assessments of individuals with dementia by family informants. PubMed was searched for studies with a similar design and a forward citation tracking was conducted using Google Scholar in June 2018. Results from a new sample and from published studies were combined in a random effect meta-analysis.

Setting & Participants:

Family members of older adults with MCI or dementia.

Measures:

The five major dimensions (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and facets of personality were assessed with NEO Personality Inventory questionnaires.

Results:

The new sample (n = 50) and meta-analysis (18 samples; n =542) found consistent shifts in personality from the premorbid to current state in patients with cognitive impairment. The largest changes (>1 SD) were declines in conscientiousness (particularly for the facets of self-discipline and competence) and extraversion (decreased energy and assertiveness), as well as increases in neuroticism (increased vulnerability to stress). The new sample suggested that personality changes were larger in individuals taking cognition-enhancing medications (cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine). More recent studies and those that examined individuals with MCI found smaller effects.

Conclusions and Implications:

Consistent with the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia, the new study and meta-analysis found replicable evidence for large changes in personality among individuals with dementia. Future research should examine whether there are different patterns of personality changes across etiologies of dementia to inform differential diagnosis and treatments. Prospective, repeated assessments of personality using both self- and informant- reports are essential to clarify the temporal evolution of personality change across the preclinical, prodromal, and clinical phases of dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Personality, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Cognition-enhancing

Summary

A new study and meta-analysis found that family informants observe large increases in neuroticism and large declines in extraversion and conscientiousness in individuals with dementia.

Introduction

It is common for caregivers and close relatives to observe significant change in personality with the development of dementia.1 In the seminal case described by Alois Alzheimer, the husband of Auguste D. observed behavioral as well as cognitive disturbances, including paranoia, crying, aggressiveness, and other unpredictable and disruptive behaviors.2,3 As with this first case, changes in behavior and personality remain among the most challenging clinical symptoms in dementia care.4,5 These common clinical observations of personality change are broadly supported by research findings.6-20 Personality change has been typically assessed with a retrospective design in which a knowledgeable informant, usually a spouse or family member, rates the premorbid and current personality of the person with dementia. Such informant reports play a critical role in clinical evaluations,1,21 and are an important source of information to characterize the patient’s current status and the changes that occurred over time. Most of this research has been based on the five-factor model of personality (FFM; also known as the big five).22 The FFM operationalizes personality along five broad dimensions: neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions such as fear and sadness), extraversion (the tendency to be outgoing, social, and energetic), openness (the tendency to prefer novel and diverse experiences, intellectual curiosity), agreeableness (the tendency to be cooperative, kind, and trusting), and conscientiousness (the tendency to be organized, persistent, and careful). More narrow traits, called facets, are part of each of the five dimensions. For example, neuroticism includes facets that reflect anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and vulnerability. Retrospective research has found systematic change in personality at both the broad domain level and at the more specific facet level.8

The aim of this study was to further advance knowledge on the changes in personality that occur with dementia, as observed by a knowledgeable informant. We addressed this aim by examining new data and conducting a meta-analysis of the published literature. With the new data, we examined whether personality changes were moderated by the extent of cognitive impairment and cognition-enhancing medications. By comparing published studies, we further examined whether changes in personality differed across mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and related dementias. We build on the previous meta-analysis6 with data from the new sample and work published over the past decade. We further advanced this literature by conducting a meta-analysis at the facet level of each of the five major personality factors to provide a more in-depth reporting of the observed changes.23

Methods

Participants and procedures: New data collection

New data were obtained from patients with MCI or dementia and their caregivers (informant), typically a spouse or close relative. The study was advertised at a local Memory Disorder Clinic, local organizations that support caregivers of individuals with dementia (e.g., MASKED), and broadly across the community (e.g., local newspaper, library, places of worship, retirement communities). Trained research assistants obtained consent from the patients and the caregivers. If the patient with MCI or dementia was unable to provide consent (because of concerns regarding capacity), the research assistant obtained verbal assent from the patient and consent from the proxy was obtained on the patient’s behalf. The Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the University and of the local hospital approved the protocol of this study, including the consent procedures and documents. Once consent was obtained, the research assistant interviewed informants in a location of their choosing, most often in their home, to gather demographic, lifestyle, and clinical information, including diagnoses and current medications (generally from medication containers) on the person with dementia. This part of the interview also included demographic information on the informant. Informants were asked to independently complete the personality questionnaire and to mail in responses in a pre-paid envelope. The research assistants administered the cognitive test to the patients.

Measures: Personality

Participants in our local sample completed the observer-rating form of the NEO Personality Inventory – 3 First Half (NEO-PI-3FH),24 a 120-item version of the NEO Personality Inventory-3. The NEO-PI-3FH assesses the five major factors of personality and their six facets. Participants responded to items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. For each item, participants described the personality of the person with dementia twice, once as they were at age 50 and once for their current personality. Raw scores were standardized as T-scores (Mean = 50, SD = 10) using combined-sex norms reported in the manual. A large literature supports the reliability and validity of the NEO questionnaires across age groups, clinical and non-clinical samples, and across cultures.23,25,26

Measures: Cognitive impairment

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to measure the extent of cognitive impairment of the patients.27 The MoCA is a brief screening instrument that assesses various cognitive domains (orientation, registration, attention, calculation, recall, language, executive function, abstraction, and visuospatial ability) and provides a score that ranges from 0 to 30, with scores lower than 26 suggesting potential cognitive impairment.

Meta-Analysis: Search strategy

We included results from the new sample and those from studies that were part of a previous meta-analysis.6 Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, in June 2018 we further searched PubMed for records published after November 2009, the search date of the previous meta-analyses. The search used the terms “dementia” or “MCI” or “Alzheimer’s disease,” and “personality” or “neuroticism” or “conscientiousness”. After removing duplicates, Title/Abstracts that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. Two independent reviewers (M.I. and A.T.) examined the remaining full texts. References from the included studies were screened and a forward citation search was performed using Google Scholar. We included studies that (a) examined older adults with MCI or dementia, (b) used the observer rating method, (c) collected both current and retrospective ratings, and (d) measured five-factor model personality traits.

Statistical Analysis

Significance of the differences between retrospective and current ratings was evaluated with paired-sample t-test and quantified with Cohen’s d (d = (MT2- MT1)/√(SDT12+SDT22/2)).28 We should note that for one-sample repeated measures, the d can be calculated from the mean of the individual differences over the SD of such differences,28 which will generally produce larger effects. However, we opted to use the standard d for consistency with past studies included in our meta-analysis. To examine whether MoCA scores or cognition-enhancing drugs were related to the extent of personality change, we examined regression models with the current personality traits as the outcome and MoCA scores or drugs as predictors along with premorbid traits and age and sex of the person with dementia. Stability of individual differences between the retrospective and current ratings was evaluated with test-retest Pearson correlations. We analyzed data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24 software packages (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

For the meta-analysis, we transformed the d to r (r=d/√(d2+4)) and the meta-analytic estimates were transformed back to d (d=2r/√(1-r2)28-30 We conducted a random-effect meta-analysis. Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated with the I2statistics, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% generally considered as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. The meta-analysis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (Version 3.0, Biostat Inc, Englewood, NJ).

Results

New data: Participant Characteristics

The study included 50 patients, of whom 9 had MCI and 41 had dementia. Patients were aged 64 to 95 years old (M = 79, SD = 9) and included 48% women, 8% Latino, 12% African- American, 36% had a college degree or higher education, 70% were living in their home, and 22% in an assisted living facility. Patients scored 25 or lower on the MoCA (M = 11.55, SD = 6.74; one patient was unable to complete the MoCA due to visual disability), 60% were taking one or more cognition-enhancing medications (i.e., 14.6% cholinesterase inhibitors, 14.6% memantine, and 36.6% both), and 38% were taking one or more psychiatric medications (8% benzodiazepines, 22% selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and 10% antipsychotics). The MoCA score was lower in individuals taking cognition-enhancing medications (M =9.30, SD=5.90) compared to those not on such drugs (M = 15.11, SD = 6.57). We recruited one informant for each patient. The informants were either spouses (52%), children (44%), or other family members or friends (4%) of the patient. The informants were 78% women and aged 44 to 87 years old (M = 65, SD = 11).

New data: Personality changes

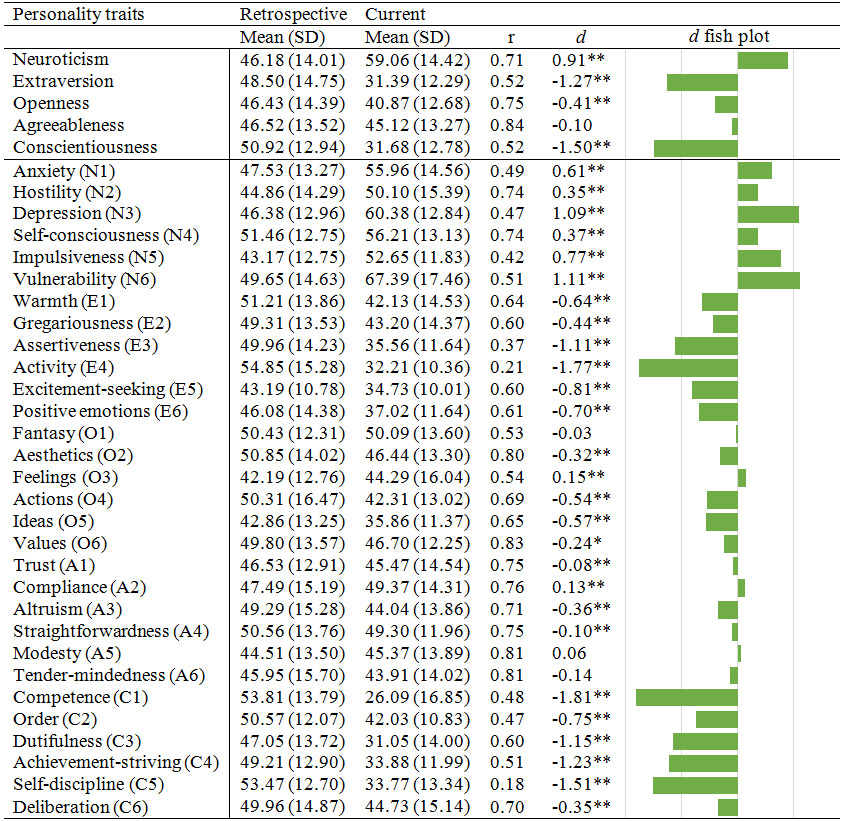

Table 1 presents the mean (SD) of both the retrospective and current personality ratings and the d for the differences between retrospective and current ratings. The retrospective ratings were all in the normal range whereas the current ratings suggested that patients with MCI or dementia scored high in neuroticism (54% had T-scores > 60, which is 1 SD above the normative mean) and low in all other factors, particularly extraversion (68% had T-scores < 40) and conscientiousness (78% had T-scores < 40). The largest changes were observed for neuroticism (d = 0.91), extraversion (d = −1.27), and conscientiousness (d = −1.50). The facets with the largest difference (d > [1.0]) were depression (N3) and vulnerability (N6) within the neuroticism domain; assertiveness (E3) and activity (E4) within the extraversion domain; competence (C1), dutifulness (C3), achievement striving (C4), and self-discipline (C5) within the conscientiousness domain.

Table 1.

Informant Retrospective and Current personality ratings

|

Note: N = 50.

p<.05.

p<.01.

Table 1 also shows the correlation between the retrospective and current personality ratings. Despite the large mean level changes, the moderate to high correlations (r > 0.50) suggested that individual differences were relatively maintained. However, the stability coefficients for extraversion, conscientiousness, and several facets were substantially lower than the typical coefficients observed for these traits in healthy adult populations.9,14,17,31,32

New data: Association between MoCA, medications, and personality change

To test whether the severity of cognitive impairment was associated with the extent of personality change, we ran multiple regression models with the current personality as an outcome, MoCA score as a primary predictor, and retrospective personality, age, and sex as covariates. Age and sex of the patients were unrelated to the extent of personality change. We found that the MoCA score was not a significant predictor (p > .05), but there were trends for larger declines in conscientiousness (β = .23, p = .07) and openness (β = .16, p = .09) among those with lower MoCA scores.

Similarly, we examined whether taking cognition-enhancing medications (i.e., cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine) were associated with the extent of personality change. Patients on cognition-enhancing medications had greater increases in neuroticism (β = .29, p < .01) and greater decreases in extraversion (β = −.29, p = .04) and conscientiousness (β = −.43, p < .01). These effects remained significant when the MoCA score and the use of psychiatric medications (benzodiazepines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and antipsychotics) were included as covariates (see Table S1). Follow-up analyses suggested slightly larger changes in patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors compared to memantine, but most patients were prescribed both these mediations. In terms of effect sizes, the changes in personality among individuals taking the cognition-enhancing medications (neuroticism d = 1.38, extraversion d = −1.71, and conscientiousness d = −2.20) were more than double compared to patients not on cognition-enhancing medications (neuroticism d = 0.42, extraversion d = −0.73, and conscientiousness d = −0.79).

Meta-Analysis

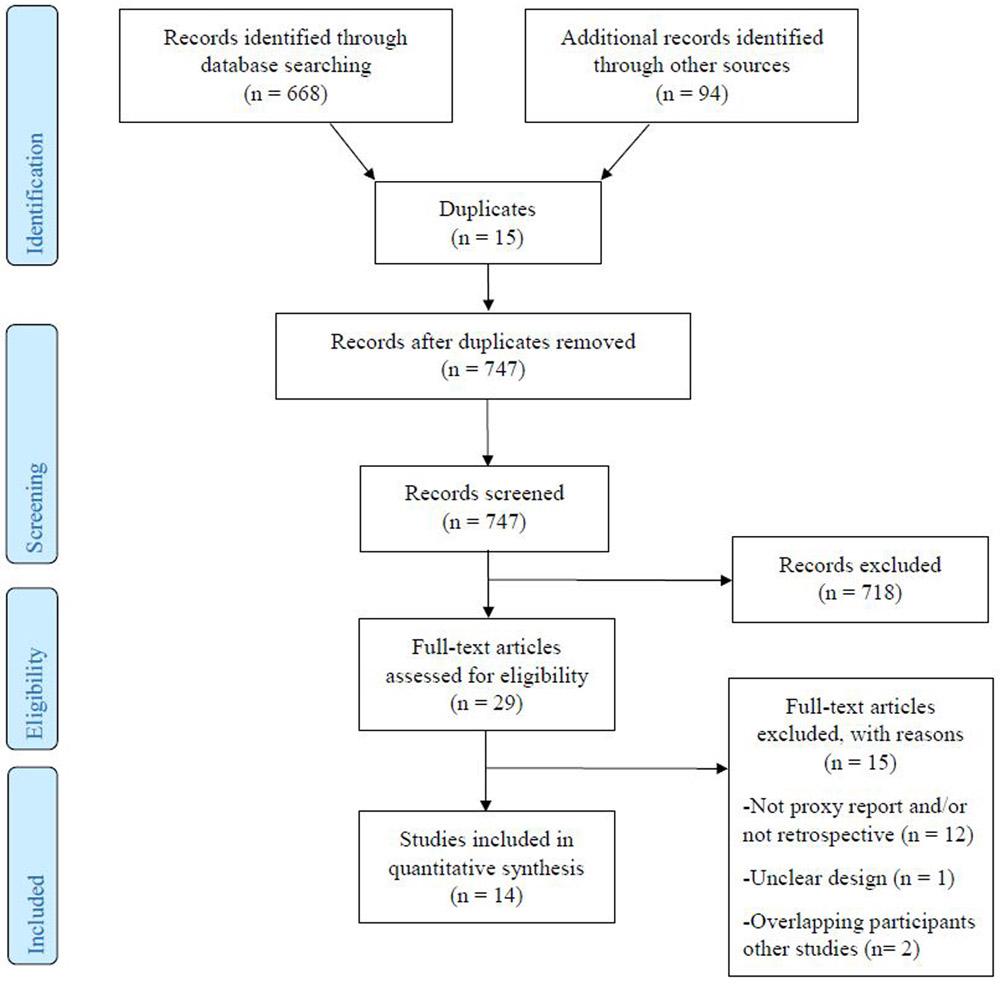

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram with the search and screening results. The database search identified 668 records and the bibliography and forward search of relevant articles identified an additional 94 records for screening. Of note, we excluded two studies33,34 because of sample overlap with two of the studies included.17,19 One study16 of 50 patients included 38 patients that were part of two previous reports 8,12 . All three studies , , were included in the previous6 and current meta-analysis. In a meta-analysis that excluded the sample16 with overlapping patients, the results remained essentially the same. The search and screening identified 417-20 new studies to be included in the meta-analysis and 9 studies that were part of the previous meta-analysis,6 for a total of 14 studies (including the new sample). Given that two studies18,20 provided separate results from 3 clinical groups, the final meta-analysis included 18 samples. The meta-analysis included a total of 542 patients, of whom 251 were not part of the previous meta-analysis.6

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for the 18 samples included in the meta-analysis. Most studies were carried out in the US and Europe. The sample sizes ranged from 8-55, the average age ranged from 65 to 87 years, and the proportion of women ranged from 40% to 84%. Most studies focused on AD patients, but recent studies have examined other causes of dementia. The differences (d) between the retrospective and current personality ratings in each sample and the meta-analytic estimates are presented in Table 3 for the five factors and in Table 4 for the 30 facets. The meta-analytic estimates were significant for all five traits, but the largest changes (d > 1) were increases in neuroticism and declines in extraversion and conscientiousness. The results were highly consistent across studies, with the I2 lower than 25% for all traits except for conscientiousness (I2 = 61%). The considerably smaller changes found for conscientiousness in the two MCI samples18,19 explain this heterogeneity. We repeated the meta-analysis after excluding the two MCI samples,18,19 which resulted in an I2 = 0%. Another noticeable pattern in Table 3 was the generally smaller effect sizes in more recent studies. Follow-up meta-regressions found the differences between the studies included in the previous meta-analysis6 and those published after17-20 to be significant for neuroticism (p < .001), extraversion (p = .036), and conscientiousness (p < .001). However, recent studies also included samples with MCI18,19 and more diverse causes of dementia (e.g., frontotemporal dementia),18,20 which may account for the observed trends.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the samples included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | Country | n | Age | Female | Education | Diagnosis | MMSE | Informants | Inventory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siegler8 | 1991 | US | 35 | 66.6 | 40% | n/a | AD, other dementias | 21.8 | Spouses, children, sibs | NEO-PI |

| Chatterjee9 | 1992 | US | 38 | 70.7 | 55% | n/a | AD (moderate dementia) | 15.5 | Spouses, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Strauss10 | 1993 | US | 22 | 72.0 | 50% | 12.6 | AD (moderate dementia) | 15.4 | Spouses, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Strauss11 | 1994 | US | 29 | 68.8 | 41% | 13.8 | AD (moderate dementia) | 15.3 | Spouses, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Siegler12 | 1994 | US | 26 | 71.4 | 50% | 14.6 | AD (moderate dementia) | 22.2 | Spouses, others | NEO-PI |

| Williams13 | 1995 | GB | 36 | 77.0 | n/a | n/a | Dementia | n/a | Spouses, sib, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Welleford14 | 1995 | US | 36 | 71.2 | 61% | 12-15 | AD | 17.9 | Spouses, sib, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Kolanowski15 | 1997 | US | 19 | 87.1 | 84% | n/a | AD, other dementias | 7.9 | Children | NEO-PI |

| Dawson16 | 2000 | US | 50 | 70.5 | 46% | 14.6 | AD (moderate dementia) | 22 | Spouses, children, others | NEO-PI |

| Pocnet17 | 2011 | CH | 54 | 76.9 | 72% | n/a | Mild AD | 23.7 | Family members | NEO-PI-R |

| Lykou18 | 2013 | GR | 17 | 74.1 | 71% | 8.5 | AD | 20.2 | Caregivers | TPQue5 |

| Lykou18 | 2013 | GR | 8 | 67.6 | 75% | 6.2 | FTD | 17.6 | Caregivers | TPQue5 |

| Lykou18 | 2013 | GR | 17 | 71.3 | 71% | 12.6 | MCI | 27.2 | Caregivers | TPQue5 |

| Donati19 | 2013 | CH | 55 | 71.1 | 68% | Notes | MCI | 28.0 | Close relatives | NEO-PI-R |

| Torrente20 | 2014 | AR | 19 | 73.7 | 47% | 12.4 | AD | n/a | Spouses, children | NEO-PI-R |

| Torrente20 | 2014 | AR | 16 | 69.9 | 50% | 13.1 | FTD | n/a | Spouses, children | NEO-PI-R |

| Torrente20 | 2014 | AR | 15 | 70.4 | 40% | 15.5 | PPA | n/a | Spouses, children | NEO-PI-R |

| Islama | US | 50 | 79.0 | 78% | 15.1 | Dementia, MCI | 11.3a | Spouses, children, others | NEO-PI-3FH |

Notes: From Strauss et al. 199310 we used data from primary informant; From Strauss et al. 199411 we used data from Time 1;

New sample presented in this study; Under the MMSE column is the mean (SD) for MoCA instead of MMSE. Education in Donati19: 16% ≤ 9 years; 62% 10-12 years; 22% ≥12 years. Country codes: CH = Switzerland; AR = Argentina; GR = Greece; GB = United Kingdom. NEO-PI-R = NEO Personality Inventory Revised. TPQue5 = Traits Personality Questionnaire 5. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 3.

Meta-Analysis of changes in personality factors

| Literature | n | Neuroticism | Extraversion | Openness | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siegler 1991 | 35 | 1.19 | −1.43 | −0.35 | −0.37 | −2.36 |

| Chatterjee 1992 | 38 | 1.27 | −1.25 | −0.42 | −0.38 | −1.9 |

| Straussa 1993 | 22 | 1.78 | −1.13 | −0.47 | −0.30 | −2.00 |

| Straussb 1994 | 29 | 1.29 | −1.20 | −0.48 | −0.20 | −1.83 |

| Siegler 1994 | 26 | 1.48 | −1.26 | −0.45 | −0.32 | −2.05 |

| Williams 1995 | 36 | 1.30 | −1.80 | −0.3 | −0.20 | −2.70 |

| Welleford 1995 | 36 | 1.41 | −1.24 | −0.43 | −0.36 | −1.76 |

| Kolanowski 1997 | 19 | 0.29 | −0.59 | −0.82 | −0.01 | −3.15 |

| Dawson 2000 | 50 | 1.42 | −1.36 | −0.40 | 0.00 | −2.32 |

| Pocnet 2011 | 54 | 1.33 | −1.30 | −1.00 | −0.28 | −2.48 |

| Lykous 2013 (AD) | 17 | 0.78 | −1.27 | −0.06 | −0.46 | −1.63 |

| Lykous 2013 (FTD) | 8 | −0.58 | −1.68 | 0.06 | −0.42 | −2.20 |

| Lykous 2013 (MCI) | 17 | 0.71 | −0.70 | −0.11 | −0.22 | −0.77 |

| Donati 2013 | 55 | 0.22 | −0.25 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.28 |

| Torrente 2014 (AD) | 19 | 0.87 | −0.53 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −1.49 |

| Torrente 2014 (FTD) | 16 | 0.46 | −0.73 | −0.67 | 0.20 | −1.38 |

| Torrente 2014 (PPA) | 15 | 1.05 | −0.96 | −0.77 | −0.13 | −1.10 |

| Islamc | 50 | 0.91 | −1.27 | −0.40 | −0.10 | −1.50 |

| Combined d (95% CI) |

542 | 1.01 (0.78, 1.25) |

−1.09 (−1.31, −0.89) |

−0.41 (−0.60, −0.23) |

−0.19 (−0.36, −0.01) |

−1.77 (−2.19, −1.39) |

| Z | 9.24 | −11.09 | −4.53 | −2.02 | −10.47 | |

| p-value | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | |

| Q | 21.35 | 17.91 | 8.89 | 3.16 | 43.15 | |

| p-value | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| I2 | 20% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 61% |

Notes: The values in the table are effect sizes ds of the differences between current and premorbid personality traits.

Data from primary informant;

Data from Time 1;

New sample presented in this study.

Table 4.

Meta-Analysis of changes in personality facets

| Personality facets | No. of studies |

I2 | Z | d | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety (N1) | 10 | 0% | 6.63** | 0.77 | (0.54, 1.02) |

| Hostility (N2) | 9 | 0% | 3.42** | 0.43 | (0.18, 0.68) |

| Depression (N3) | 10 | 0% | 10.32** | 1.25 | (0.99, 1.52) |

| Self-consciousness (N4) | 9 | 0% | 3.81** | 0.47 | (0.23, 0.73) |

| Impulsiveness (N5) | 9 | 0% | 3.59** | 0.45 | (0.20, 0.70) |

| Vulnerability (N6) | 10 | 36% | 11.60** | 1.91 | (1.53, 2.32) |

| Warmth (E1) | 9 | 66% | −1.84 | −0.41 | (−0.86, 0.03) |

| Gregariousness (E2) | 9 | 0% | −3.39** | −0.42 | (−0.67, −0.18) |

| Assertiveness (E3) | 10 | 0% | −9.26** | −1.10 | (−1.37, −0.86) |

| Activity (E4) | 10 | 0% | −10.23** | −1.23 | (−1.50, −0.98) |

| Excitement-seeking (E5) | 9 | 0% | −4.62** | −0.58 | (−0.84, −0.33) |

| Positive emotions (E6) | 9 | 0% | −5.56** | −0.70 | (−0.96, −0.45) |

| Fantasy (O1) | 9 | 49% | 0.74 | 0.13 | (−0.22, 0.49) |

| Aesthetics (O2) | 9 | 0% | −3.83** | −0.48 | (−0.73, −0.23) |

| Feelings (O3) | 9 | 0% | −2.29* | −0.28 | (−0.53, −0.04) |

| Actions (O4) | 9 | 0% | −2.34* | −0.29 | (−0.54, −0.05) |

| Ideas (O5) | 10 | 0% | −7.64** | −0.90 | (−1.15, −0.66) |

| Values (O6) | 9 | 0% | −1.50 | −0.19 | (−0.43, 0.06) |

| Trust (A1) | 5 | 0% | −1.15 | −0.19 | (−0.53, 0.14) |

| Compliance (A2) | 5 | 0% | 0.42 | 0.07 | (−0.26, 0.41) |

| Altruism (A3) | 5 | 0% | −2.84** | −0.49 | (−0.84, −0.15) |

| Straightforwardness (A4) | 5 | 0% | −0.33 | −0.06 | (−0.39, 0.28) |

| Modesty (A5) | 5 | 4% | −0.60 | −0.10 | (−0.45, 0.24) |

| Tender-mindedness (A6) | 5 | 0% | −1.29 | −0.22 | (−0.56, 0.11) |

| Competence (C1) | 5 | 0% | −9.40** | −1.77 | (−2.24, −1.35) |

| Order (C2) | 5 | 64% | −3.03** | −0.96 | (−1.68, −0.33) |

| Dutifulness (C3) | 5 | 15% | −6.92** | −1.41 | (−1.90, −0.98) |

| Achievement-striving (C4) | 5 | 0% | −7.60** | −1.38 | (−1.80, −0.99) |

| Self-discipline (C5) | 5 | 0% | −9.15** | −1.71 | (−2.18, −1.30) |

| Deliberation (C6) | 5 | 66% | −2.59** | −0.85 | (−1.57, −0.20) |

Notes: Number of participants for the 10 studies was n = 339, for the 9 studies was n = 289, and for the 5 studies was n =154. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

p<.05.

p<.01.

One of the most novel aims of our meta-analysis was to dwell deeper at the level of the facets that compose each factor. A total of 10 samples (n=339) included ratings on the facets (Table 4 and Table S2). The facets for neuroticism with the largest increases were depression (N3) and vulnerability (N6). For extraversion, the facets that decreased the most were assertiveness (E3) and activity (E4). Most facets of conscientiousness had substantial declines, with the largest changes observed for competence (C1) and self-discipline (C5). As for the factors, for most facets there was little evidence of heterogeneity of effects across samples.

Discussion

Data from a new sample and a meta-analysis of the published literature indicates that knowledgeable informants observe large and systematic changes in the personality of individuals with dementia. The largest increases were found for the neuroticism domain, particularly increased emotional vulnerability and increased tendency to experience depressed mood. Individuals with dementia were also perceived to become more introverted, especially less assertive and more passive and withdrawn from social interactions. The largest declines were observed in the conscientiousness domain, particularly being perceived as less competent, less motivated, less capable to stay on task, and a broad loss of drive compared to premorbid personality. Changes for openness and agreeableness were relatively small. Of interest, the smaller changes in the agreeableness factor and the angry-hostility facet of neuroticism suggest that environmental triggers, rather than personality change, are major sources of emerging aggressive behavior in dementia.4,35 Given that patients who become more uncooperative and aggressive are at higher risk of institutionalization,36 community-based samples are less likely to include such patients, which may underestimate the declines in agreeableness. Overall, the observed personality changes were remarkably consistent across samples. Notably, however, the effect sizes were smaller for MCI samples and in more recent studies. The smaller effect sizes for MCI is consistent with a model of personality changes that begin with the onset of cognitive impairment and become larger with the progression of dementia.31,37

Despite the large systematic mean-level changes, test-retest coefficients from the new data and past studies9,14,17,31 suggest that individual differences in personality are relatively maintained, at least at the stage of dementia we examined in this study. In other words, on most traits, most individuals with dementia experienced similar changes but they maintained their relative standing compared to other individuals with dementia. Some facets are possible exceptions, such as self-discipline (r =. 18), which suggests that with the progression of dementia the ability to stay on task, control behavior, and remain motivated declines in most patients regardless of where they stood on these tendencies prior to disease onset.

This study also examined several potential moderators of personality change with dementia. A striking finding from our sample was the large difference in personality changes associated with the use of cognition-enhancing medications. Patients on cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine were reported to experience greater increases in neuroticism and greater decreases in extraversion and conscientiousness. We are not aware of other studies that have examined such an association. Given the lack of clinically significant effects of these medications on mood and behaviors,4,38 it is unlikely that these drugs may have caused the observed changes in personality. We interpret this association as reflecting an indication effect39. It is plausible that caregivers and patients were more likely to ask for cognition-enhancing medications if the person with dementia was experiencing greater personality changes. A randomized prospective study would be necessary to further test the potential effects of cognition-enhancing drugs on personality.

This research had some limitations. One limitation of the new sample was the reliance on informant reported physician diagnosis. Given our recruitment strategy (mainly from a Memory Disorder Clinic and dementia support organization) and the sample characteristics (i.e., MoCA scores, medications, etc.), it is unlikely that we included patients without cognitive impairment, but we were unable to definitively differentiate AD from other causes of dementia such as Lewy body, frontotemporal, and vascular dementia. The study design also posed potential limitations, including recall and hindsight biases. While the informant ratings have been found to be reliable across raters and time,10,11 the ratings could be influenced by contrast effects between premorbid and current personality, the idealization of the premorbid personality, and labeling effects due to the diagnosis on current ratings.40 For example, with the retrospective design, current symptoms of the patient may skew the informant’s memory of the patient’s premorbid personality.9 The retrospective design also does not provide any information on the timing of personality changes. Prospective longitudinal research suggests that there are no significant changes in personality in the preclinical phase37, but change in neuroticism has been noted with the diagnosis of MCI and dementia.41-43 Ideally, prospective studies should follow a large sample of adults assessed with both self- and observer-ratings of personality at multiple occasions to better define the trajectories of personality changes with the development and progression of dementia. Few samples to date have examined different types of dementia,18,20 but as evidence accumulates, it could be possible that changes in personality traits may inform differential diagnosis (e.g., larger or different changes in frontotemporal dementia vs. AD). It is also of interest to address whether personality changes vary across community, assisted living, and nursing home settings. Similarly, other environmental and cultural factors may modulate the extent of personality changes.

Conclusions and Implications.

This study provides a detailed account of personality changes with dementia from the observer’s perspective. The findings were consistent across samples and point to large increases in neuroticism and declines in extraversion and conscientiousness. Despite the systematic changes, individual differences were mostly preserved, which supports the person’s sense of identity even with moderate dementia. Such continuity indicates that person-centered care can leverage premorbid traits to better tailor interventions to patients’ traits and preferences. Other clinical implications are the potential of these personality changes to manifest as psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia.44-46 For example, apathy is common in individuals with dementia and presents as loss of interests and motivation (conscientiousness) and social withdrawal (extraversion). Higher neuroticism may manifest as irritability, depression, anxiety, and other psychological symptoms of dementia.44-46 These findings complement clinicians’ observations1 with a quantitative assessment based on reliable measures of personality. Recognition of the patterns of personality change with dementia can be useful for clinicians and especially for caregivers to adjust expectations on common changes in fundamental psychological dispositions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Awards Number R21AG057917 and R01AG053297. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahm R Alzheimer’s discovery. Current biology: CB. 2006;16(21):R906–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hippius H, Neundorfer G. The discovery of Alzheimer’s disease. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2003;5(1):101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Bmj. 2015;350(7):h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkenhäger-Gillesse EG, Kollen BJ, Achterberg WP, Boersma F, Jongman L, Zuidema SU. Effects of Psychosocial Interventions for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia on the Prescription of Psychotropic Drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018;19(3):276. e271–276. e279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robins Wahlin TB, Byrne GJ. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26(10):1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’lorio A, Garramone F, Piscopo F, Baiano C, Raimo S, Santangelo G. Meta-Analysis of Personality Traits in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comparison with Healthy Subjects. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018;62(2):773–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegler IC, Welsh KA, Dawson DV, et al. Ratings of personality change in patients being evaluated for memory disorders. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 1991;5:240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee A, Strauss ME, Smyth KA, Whitehouse PJ. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of neurology. 1992;49:486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauss ME, Pasupathi M, Chaterjee A. Concordance between observers in descriptions of personality change in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychology and aging. 1993;8:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss ME, Pasupathi M. Primary caregivers’ descriptions of Alzheimer patients’ personality traits: temporal stability and sensitivity to change. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 1994;8(3):166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegler IC, Dawson DV, Welsh KA. Caregiver Ratings of Personality-Change in Alzheimers-Disease Patients - a Replication. Psychology and aging. 1994;9(3):464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams R, Briggs R, Coleman P. Carer-rated personality changes associated with senile dementia. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 1995;10(3):231–236. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welleford EA, Harkins SW, Taylor JR. Personality change in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: relations to caregiver personality and burden. Experimental aging research. 1995;21(3):295–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolanowski AM, Strand G, Whall A. A pilot study of the relation of premorbid characteristics to behavior in dementia. Journal of gerontological nursing. 1997;23(2):21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson DV, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Siegler IC. Premorbid personality predicts level of rated personality change in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2000;14(1):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pocnet C, Rossier J, Antonietti JP, von Gunten A. Personality changes in patients with beginning Alzheimer disease. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(7):408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lykou E, Rankin KP, Chatziantoniou L, et al. Big 5 personality changes in Greek bvFTD, AD, and MCI patients. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2013;27(3):258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donati A, Studer J, Petrillo S, et al. The evolution of personality in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2013;36(5-6):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torrente F, Pose M, Gleichgerrcht E, et al. Personality Changes in Dementia: Are They Disease Specific and Universal? Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briggs R, O’neill D. The informant history: a neglected aspect of clinical education and practice. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2016;109(5):301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the Five-Factor Model and its applications. J Pers. 1992;60(2):175–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr. Brief versions of the NEO-PI-3. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28:116–128. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCrae RR, Terracciano A, 78 Members of the Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2005;88:547–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(1):28–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. second, ed. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Meta-analytic procedures for combining studies with multiple effect sizes. Psychological bulletin. 1986;99(3):400. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman H Magnitude of experimental effect and a table for its rapid estimation. Psychological bulletin. 1968;70(4):245. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terracciano A, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Sutin AR. Cognitive impairment, dementia, and personality stability among older adults. Assessment. 2018;25(3):336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terracciano A, Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR. Personality plasticity after age 30. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:999–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pocnet C, Rossier J, Antonietti JP, von Gunten A. Personality traits and behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients at an early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2013;28(3):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubio MM, Antonietti J, Donati A, Rossier J, Von Gunten A. Personality traits and behavioural and psychological symptoms in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2013;35(1-2):87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Duinen-van den IJCL, Mulders A, Smalbrugge M, et al. Nursing Staff Distress Associated With Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Young-Onset Dementia and Late-Onset Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018;19(7):627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical care. 2009;47(2):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terracciano A, An Y, Sutin AR, Thambisetty M, Resnick SM. Personality Change in the Preclinical Phase of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1259–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birks J Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006(1):Cd005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huisa B, Thomas R, Jin S, Oltersdorf T, Taylor C, Feldman H. Memantine and Cholinesterase Inhibitor Use in Alzheimer Disease Trials: Potential for Confounding by Indication (P6. 178). AAN Enterprises; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terracciano A, Sutin A. Personality and Alzheimer’s disease: An integrative review Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caselli RJ, Langlais BT, Dueck AC, et al. Personality Changes During the Transition from Cognitive Health to Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoneda T, Rush J, Graham EK, et al. Increases in Neuroticism May Be an Early Indicator of Dementia: A Coordinated Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018:gby034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waggel SE, Lipnicki DM, Delbaere K, et al. Neuroticism scores increase with late-life cognitive decline. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015;30(9):985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Archer N, Brown RG, Reeves SJ, et al. Premorbid personality and behavioral and psychological symptoms in probable Alzheimer disease. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(3):202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osborne H, Simpson J, Stokes G. The relationship between pre-morbid personality and challenging behaviour in people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & mental health. 2010;14(5):503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. Self-reported personality traits are prospectively associated with proxy-reported behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia at the end of life. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2018;33(3):489–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.