Abstract

Background

Measuring and monitoring progress towards Millennium Development Goals (MDG) 4 and 5 required valid and reliable estimates of maternal and child mortality. In South Africa, there are conflicting reports on the estimates of maternal and neonatal mortality, derived from both direct and indirect estimation techniques. This study aimed to systematically review the estimates made of maternal and neonatal mortality in the period from 1990 to 2015 in South Africa and determine trends over this period.

Methods

Nationally-representative studies reporting on maternal and neonatal mortality in South Africa were included for synthesis. Literature search for eligible studies was conducted in five electronic databases: Medline, Africa-Wide Information, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL. Searches were restricted to articles written in English and presenting data covering the period between 1990 and 2015. Reference lists of retrieved articles were screened for additional publications, and grey literature was searched for relevant documents for the review. Three independent reviewers were involved in study selection, data extractions and achieving consensus.

Results

In total, 969 studies were retrieved and 670 screened for eligibility yielding 25 studies reporting data on maternal mortality and 14 studies on neonatal mortality. Most of the studies had a low risk of bias. Estimates from the institutional reporting differed from the international metrics with wide uncertainty/confidence intervals. Moreover, modelled estimates were widely divergent from estimates obtained through empirical methods. In the last two decades, both maternal and neonatal mortality appear to have increased up to 2009, followed by a decrease, more pronounced in the care of maternal mortality.

Conclusion

Estimates from both global metrics and institutional reporting, although widely divergent, indicate South Africa has not achieved MDG 4a and 5a goals but made a significant progress in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. To obtain more accurate estimates, there is a need for applying additional estimation techniques which utilise available multiple data sources to correct for underreporting of these outcomes, perhaps the capture-recapture method.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016042769

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13643-019-0991-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Maternal mortality, Neonatal mortality, Millennium Development Goals, South Africa

Background

Monitoring progress towards MDG 4 and 5 (reducing child and maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015) required valid, reliable and internationally comparable estimates of maternal and child mortality in the country. Various methods for measuring and estimating maternal and child mortality have been developed, tested and widely used [1–8]. Estimating these outcomes in developing countries is challenging due to the lack of accurate, valid and reliable data [8–14].

Recent estimates from the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN-IGME) and Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-agency Group (MMEIG) indicated that South Africa did not achieve the MDG 4a and 5b targets by 2015 (reducing by three quarters the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and reducing by two thirds the under-five mortality rate in the period between 1990 and 2015, respectively) [9, 14]. Considering other African countries which did not meet MDG 4 and 5 targets, only South Africa had conflicting estimates of maternal and neonatal mortality reported by different sources with wide uncertainty intervals [9, 14–18].

South Africa is unusual among developing countries in that national facility-based mortality audits are carried out for maternal, perinatal and child deaths [19, 20]. Estimation of maternal and neonatal mortality in the country is often based on the vital registration, National Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (NCEMD) which records maternal deaths and the Perinatal Problem Identification Program (PPIP) which records stillbirths and neonatal deaths [19–22]. The CEMD data provides the maternal deaths from the routine surveillance of maternal deaths at a facility level whereas vital registration data derives deaths from the causes of deaths, as well as surveys and censuses provide maternal deaths from the collected pregnancy-related data at a household level. Nonetheless, Stats SA are the custodians of vital registration and the Department of Health are the custodians of the confidential enquiries.

The country provides unique opportunities to estimate these outcomes empirically, analytically or through modelling, by having multiple data sources with wide coverage [1–5, 21, 23, 24]. However, there are widely divergent estimates, wherein the two most frequently cited estimates are from institutional reporting and WHO metrics, which makes it difficult to both understand trends in these outcomes and to assess the successes or failures of interventions focusing on reducing maternal and child mortality in the country over the past decades. The reasons for divergent estimates between institutional reporting and WHO metrics, or among global metrics, can be explained by estimation approaches, sources and quality of data used [23, 25, 26].

Monitoring maternal and neonatal mortality in South Africa over the past two decades is of high importance given the introduction of Termination of Pregnancy Act in 1996 which has reduced the extent of abortion-related maternal morbidity and mortality as well as the context of high HIV prevalence and its associated mortality in women during pregnancy and childbirth [27, 28]. There has also been a massive uptake of HIV treatment and prevention of mother-to-child transmissions (PMTCT) of HIV, which currently stands at over 90% by some estimates [29, 30].

There have been limited attempts to review maternal and neonatal mortality estimates in South Africa to facilitate understanding of trends during the MDG period. This review is expected to provide the context for understanding inconsistencies in reported estimates of maternal and neonatal mortality by the institutional reporting and the global metrics by ascertaining estimation methods, data sources and quality, sampling methods and definitions used, to better inform comparisons across such estimates.

Aim

This review aimed to synthesise estimates of maternal and neonatal mortality for the period 1990 to 2015 in South Africa and to determine temporal trends during this period.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The review protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database in 2016 with a registration number CRD42016042769 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016042769) and has already been published [31]. The presentation and reporting of results in this review followed the systematic review reporting standard (PRISMA-P) [32]. To ensure transparency, a PRISMA flow chart was used and a table indicating all included studies was presented [33].

Eligibility criteria

The population for eligible studies included pregnant women and neonates for ascertaining maternal and neonatal mortality, respectively. All studies that are nationally representative, reports providing national-level data (and trends thereof) and vital registration data were eligible for this review. Searches were restricted to studies written in English and being conducted in South Africa or which have used South African data, and multicentre studies including South Africa, reporting data covering the period 1990 to 2015. No restrictions on the date of publication were made in order to include articles reporting data from 1990 to 2015 which are published beyond 2015.

Information sources

Separate searches for the two outcomes (maternal and neonatal mortality) were conducted in the following electronic databases: Medline, Africa-Wide Information, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL. The last search was carried out on 18 August 2017. No restrictions on the date of publication were made. Additional searches for conference abstracts and proceedings were made. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also screened for additional publications. Reports by the government or other agencies were included based on publications, and a number of data sources reported by them were included. Contacts with experts in the field of study were made to identify additional relevant articles.

Search

The searches in the forementioned electronic databases were conducted from August 2016 to August 2017. All searches were restricted to articles written in English and reporting data covering the period from 1990 to 2015. In particular, the search strategy used in Medline database was as follows: ((“mothers”[MeSH Terms] OR “mothers”[All Fields] OR “maternal”[All Fields]) OR (“infant, newborn”[MeSH Terms] OR (“infant”[All Fields] AND “newborn”[All Fields]) OR “newborn infant”[All Fields] OR “neonatal”[All Fields])) AND ((“mortality”[Subheading] OR “mortality”[All Fields] OR “mortality”[MeSH Terms]) OR (“death”[MeSH Terms] OR “death”[All Fields])) AND (estimation[All Fields] OR estimates[All Fields]) AND (“South Africa”[Mesh] OR (“south africa”[MeSH Terms] OR (“south”[All Fields] AND “africa”[All Fields]) OR “south africa”[All Fields])) AND ((“1990/01/01”[PDAT]: “3000/12/31”[PDAT]) AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND English[lang]) Additional file 1.

Study selection

Search outputs were managed in EndNote reference manager. Any duplicate records were removed before the screening process takes place. When the same article was captured in different journals or the same results were presented with different main authors, the most detailed publications were selected for review. Three independent reviewers were involved in the screening and selection of articles to be included in a quantitative (narrative) synthesis. This involved an assessment of articles based on titles and abstracts and full-text review using Covidence software (https://www.covidence.org/). For an article to be eligible for inclusion in the systematic review, two reviewers had to agree to include it. A third reviewer was consulted in case of any difference of opinion between the two reviewers. This followed when they failed to reach a consensus after a joint examination of the different views.

Data collection process

Analysis of the full text was conducted for all eligible articles. Two authors extracted data independently using a pre-agreed data abstraction template. In the case of discrepancies in the extracted data between authors, consensus was sought before involving a third author for resolving the disparities. During the data extraction process, study authors/investigators were contacted to provide extra information when there were insufficient information/data reported in the article.

Data items

The following information was extracted for eligible studies: first author’s name; year of publication; year of death (maternal and neonatal); number of pregnant women; number of live births; maternal deaths; neonatal deaths; definition of maternal death; definition of neonatal death; maternal mortality ratio/rate (if reported, and by year); neonatal mortality rate (if reported, and by year); sampling method; estimation method used; and an indicator variable whether the records are complete.

The main outcomes in this review were maternal and neonatal mortality. Maternal death/mortality was defined as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes [34]. Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

Neonatal death/mortality was also defined as the death of live-born within the first 28 days of life. Neonatal mortality rate was defined as the number of infant deaths within the first 28 days of life per 1000 live births.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Assessment of risk of bias was done at a study and outcome level. Two authors assessed the study quality based on the following quality assessment criteria: (1) definition of maternal mortality, (2) definition of neonatal deaths, (3) completeness of ascertainment of maternal and neonatal mortality, (4) completeness of ascertainment of live births, (5) sampling technique/design and (6) data quality. Studies were assessed based on each criterion and were rated as “high risk of bias” or “low risk of bias” accordingly. Studies rated as high risk of bias on any criterion were assigned an overall rating of high risk of bias while the overall rating of low risk of bias was only assigned in studies with low risk of bias in all criteria. For model-based estimations, risk of bias was assessed based on the input data used. Reports by the government and other agencies such as Stat SA, National Department of Health and WHO were assessed using similar criteria as empirical studies. Table 1 shows the assessment criteria of risk of bias in individual studies.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment criteria for individual studies

| No. | Criteria | Attributes | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Definition of maternal mortality | ❖ ICD-10 maternal death definition [85], or similar | Low |

| ❖ No or unclear definition provided | High | ||

| 2. | Definition of neonatal mortality | ❖ Death of live-born within the first 28 days of life, or similar | Low |

| ❖ No or unclear definition provided | High | ||

| 3. | Completeness of ascertainment of maternal and neonatal deaths | ❖ Prospective recording of mortality data ❖ Mixed methods cross-referencing facility records ❖ Demographic surveillance system with frequent rounds ❖ Survey based on recall of maternal or neonatal deaths ≤ 6 months previously |

Low |

| ❖ Survey using direct or indirect sisterhood estimation methods ❖ Demographic surveillance system with infrequent rounds. |

High | ||

| 4. | Completeness of ascertainment of live births | ❖ Prospective recording of births data ❖ Use of census < 5 years old for live births |

Low |

| ❖ Use of census ≥ 5 years old for live births ❖ Live births data source not stated or unclear |

High | ||

| 5. | Sampling technique/design | ❖ Census ❖ Vital registration ❖ Survey using nationally representative sample ❖ Systematic analysis involving the use of data collected from the above method(s) |

Low |

| ❖ Design or sampling techniques not stated or unclear ❖ Provincial or sub-national sample used |

High | ||

| 6. | Data quality | ❖ Data provide enough information for the study | Low |

| ❖ Insufficient data provided or unclear | High |

Summary measures

Data were presented as ratios for maternal mortality and rates for neonatal mortality with their corresponding confidence or uncertainty intervals.

Synthesis of results

Data were entered and analysed using STATA software version 14.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). Data were presented as MMR or NMR in tables and graphs to depict trends over time. The reasons for study exclusions were clearly documented.

Results

Study selection

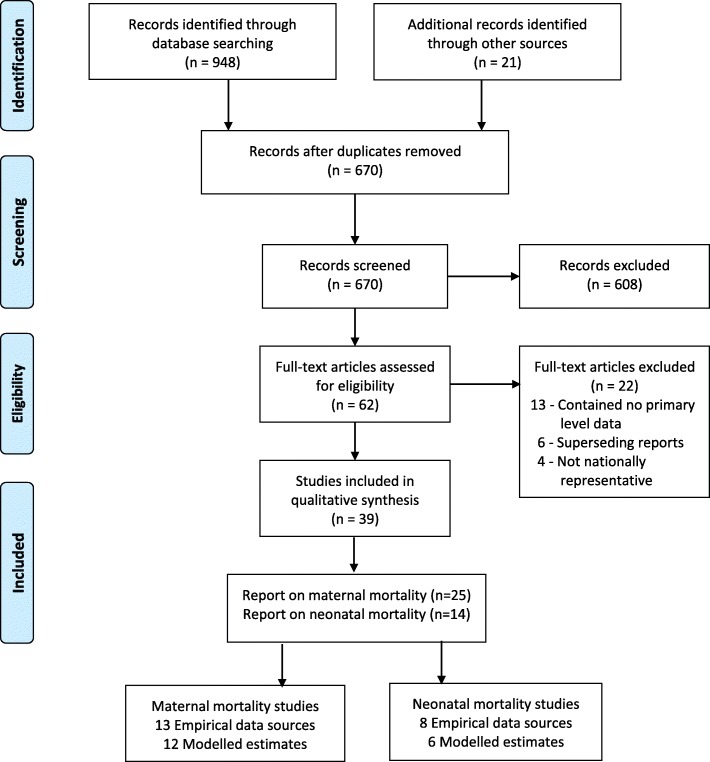

As presented in Fig. 1 below, a total of 948 studies were identified through the literature search and 21 additional studies were identified through screening of reference lists. After removing the duplicates, 670 studies were screened for eligibility. A total of 608 studies were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts as they reported irrelevant information. Sixty-two abstracts were shortlisted for full-text review and 39 studies met the inclusion criteria for analysis. Of studies included in the review, 25 reported data on maternal mortality [28, 35–55] and 14 on neonatal mortality [14, 23, 40, 45, 55–64].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis

Characteristics of the included studies

Maternal mortality

Table 2 depicts the characteristics of studies reporting maternal mortality data. All studies were nationally representative presenting national level data covering a period between 1990 and 2015. Twelve studies estimated MMR though modelling [35–44, 65, 66] while 13 studies estimated MMR empirically [28, 45–55, 67]. Regarding the study design, 11 studies based on modelling [35–44, 66], seven active surveillance [28, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 67], three vital registration [45–47], two population-based household [55, 65] and a census [52]. The most common definitive data source was the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) (n = 7) [28, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 67] followed by the WHO models (n = 6) [35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44] and vital registration (n = 3) [45–47].

Table 2.

Study characteristics for maternal mortality data

| No. | Author (year) | Duration covered | Data source/type | Definitive data source | Design | Estimation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Dorrington et al., 2016 [45] | 2008–2013 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 2. | WHO, 2015 [35] | 1990–2015 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Bayesian maternal mortality estimation model |

| 3. | MDG/Stats SA, 2015 [46] | 1998–2013 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 4. | Dorrington et al., 2015 [47] | 2011–2014 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 5. | WHO, 2014 [36] | 1990–2013 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Multilevel-regression model |

| 6. | Kassebaum et al., 2014 [37] | 1990–2013 | Modelling | IHME | Modelling | Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm) |

| 7. | Department of Health, 2014 [48] | 2005–2014 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 8. | NCCEMD, 2014 [49] | 2011–2013 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 9. | Udjo, 2014 [38] | 2001–2007 | Modelling | Model A | Modelling | Growth Balance method + Relation Gompertz model |

| 10. | Pattinson et al., 2013 [67] | 1999–2012 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 11. | WHO, 2012 [39] | 1990–2010 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Multilevel-regression model |

| 12. | NCCEMD, 2012 [28] | 2008–2010 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 13. | Garenne, 2011 [65] | 2007 | Modelling | Model B | Population-based survey | Linear logistic model |

| 14. | WHO, 2011 [40] | 1990–2009 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Bayesian maternal mortality estimation model |

| 15. | Lozano et al., 2011 [41] | 1990–2011 | Modelling | IHME | Modelling | Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm) |

| 16. | Stats SA, 2011 [50] | 2008–2009 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration/census | Direct estimation |

| 17. | WHO, 2010 [42] | 1990–2008 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Multilevel-regression model |

| 18. | Hogan et al., 2010 [43] | 1980–2008 | Modelling | IHME | Modelling | Generalised negative binomial regression |

| 19. | NCCEMD, 2008 [51] | 2005–2007 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 20. | Garenne et al., 2008 [52] | 2001 | Census | Census | Census | Direct estimation |

| 21. | Moodley, 2003 [53] | 1999–2001 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 22. | AbouZahr et al., 2001 [44] | 2000 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Robust regression |

| 23. | Hill et al., 2001 [66] | 1995 | Modelling | Model C | Modelling | Robust regression |

| 24. | Moodley, 2000 [54] | 1999 | Empirical data | CEMD | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 25. | SADHS, 1998 [55] | 1992–1998 | Empirical data | DHS | Population-based survey | Direct sisterhood |

CEMD Confidential Enquiry to Maternal Deaths, IHME Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, DHS Demographic and Health Survey, WHO World Health Organization

Neonatal mortality

The study characteristics for neonatal mortality data are presented in Table 3 below. Eight studies used empirical data sources [23, 45, 55–60] whereas six studies based on modelling [14, 40, 61–64]. Regarding design, five studies were modelling/systematic analysis [14, 61, 62, 64], three vital registration [23, 45, 57], three population surveys [55, 56, 60] and two active surveillance [58, 59]. The most dominant definitive data sources for neonatal mortality estimates were vital registration [23, 45, 57] and population surveys [55, 56, 60], respectively.

Table 3.

Study characteristics for neonatal mortality data

| No. | Author (year) | Duration covered | Data source/type | Definitive data source | Design | Estimation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | SADHS, 2016 [56] | 2011–2016 | Empirical data | DHS | Population-based survey | Direct estimation |

| 2. | Dorrington et al., 2016 [45] | 2012–2015 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 3. | UNICEF, 2015 [14] | 1990–2015 | Modelling | UNICEF | Modelling | Bayesian hierarchical splines regression |

| 4. | UNICEF, 2014 [61] | 1990–2013 | Modelling | UNICEF | Modelling | Bayesian hierarchical splines regression |

| 5. | Dorrington et al., 2014 [57] | 2009–2013 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 6. | Pattinson et al., 2014 [23] | 2012–2013 | Empirical data | Vital registration | Vital registration | Direct estimation |

| 7. | NaPeMMCO, 2014 [58] | 2010–2013 | Empirical data | PPIP | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 8. | WHO, 2011 [40] | 1990–2009 | Modelling | WHO | Modelling | Bayesian B-splines bias-adjusted model |

| 9. | Oestergaard et al., 2011 [62] | 1990–2009 | Modelling | Model A | Modelling | Multilevel-regression model |

| 10. | NaPeMMCO, 2011 [59] | 1997–2008 | Empirical data | PPIP | Active surveillance | Direct estimation |

| 11. | Rajaratnam et al., 2010 [63] | 1970–2010 | Modelling | Model B | Modelling | Gaussian process regression |

| 12. | SADHS, 2007 [60] | 1998–2003 | Empirical data | DHS | Population-based survey | Direct estimation |

| 13. | Hyder et al., 2003 [64] | 1995 | Modelling | Model C | Modelling | UN projections |

| 14. | SADHS, 1998 [55] | 1988–1998 | Empirical data | DHS | Population-based survey | Direct estimation |

Risk of bias within studies

Table 4 below presents the assessment of risk of bias of the individual studies. A total of 11 studies reporting maternal mortality data [28, 38, 49, 51–55, 65–67] and six studies reporting neonatal mortality data [23, 55, 56, 60, 62, 64] had overall high risk of bias. Among studies reporting maternal mortality data, three studies did not use the ICD-10 definition of maternal death [52, 65, 66], eight studies used data which were not population-representative [28, 38, 48, 49, 53–55, 67], one study used sisterhood estimation methods [55] and the sampling technique was unclear in one study [53]. Of seven studies reporting neonatal mortality data having an overall high risk of bias, four were not population-representative [23, 62, 64] and three were surveys based on recall of neonatal deaths more than 6 months previously [55, 56, 60].

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment in individual studies

| No. | Author (year) | Definition | Ascertainment of deaths/live births | Sampling technique/design | Data quality | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality | ||||||

| 1. | Dorrington et al., 2016 [45] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 2. | WHO, 2015 [35] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 3. | MDG/Stats SA, 2015 [46] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 4. | Dorrington et al., 2015 [47] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 5. | WHO, 2014 [36] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 6. | Kassebaum et al., 2014 [37] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 7. | Department of Health, 2014 [48] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 8. | NCCEMD, 2014 [49] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 9. | Udjo, 2014 [38] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 10. | Pattinson et al., 2013 [67] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 11. | WHO, 2012 [39] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 12. | NCCEMD, 2012 [28] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 13. | Garenne, 2011 [65] | High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| 14. | WHO, 2011 [40] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 15. | Lozano et al., 2011 [41] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 16. | Stats SA, 2011 [50] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 17. | WHO, 2010 [42] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 18. | Hogan et al., 2010 [43] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 19. | NCCEMD, 2008 [51] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 20. | Garenne et al., 2008 [52] | High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| 21. | Moodley, 2003 [53] | Low | High | High | Low | High |

| 22. | AbouZahr et al., 2001 [44] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 23. | Hill et al., 2001 [66] | High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| 24. | Moodley, 2000 [54] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 25. | SADHS, 1998 [55] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Neonatal mortality | ||||||

| 1. | SADHS, 2016 [56] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 2. | Dorrington et al., 2016 [45] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 3. | UNICEF, 2015 [14] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 4. | UNICEF, 2014 [61] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 5. | Dorrington et al., 2014 [57] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 6. | Pattinson et al., 2014 [23] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 7. | NaPeMMCO, 2014 [58] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 8. | WHO, 2011 [40] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 9. | Oestergaard et al., 2011 [62] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 10. | NaPeMMCO, 2011 [59] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 11. | Rajaratnam et al., 2010 [63] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 12. | SADHS, 2007 [60] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 13. | Hyder et al., 2003 [64] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| 14. | SADHS, 1998 [55] | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

Results of individual studies and data synthesis

Maternal mortality

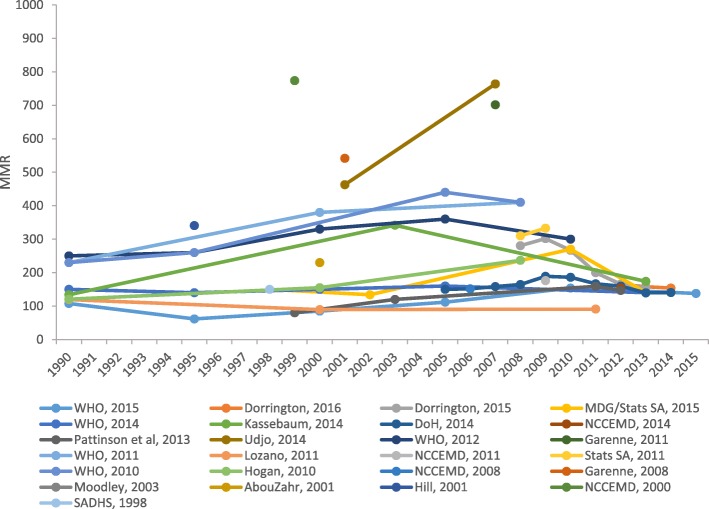

Figure 2 depicts the trend of maternal and mortality from 1990 to 2015. Estimates of MMR from most reports indicate an upward trend over time, at least until 2006 or 2009, thereafter a downward trend until 2015. Notably, four studies that ascertained maternal mortality using empirical [52, 54] and modelling [38, 65] approaches reported extreme estimates of MMR compared to other sources. Nevertheless, all recent estimates appeared to converge over time.

Fig. 2.

Trends in maternal mortality from 1990 to 2015 in South Africa

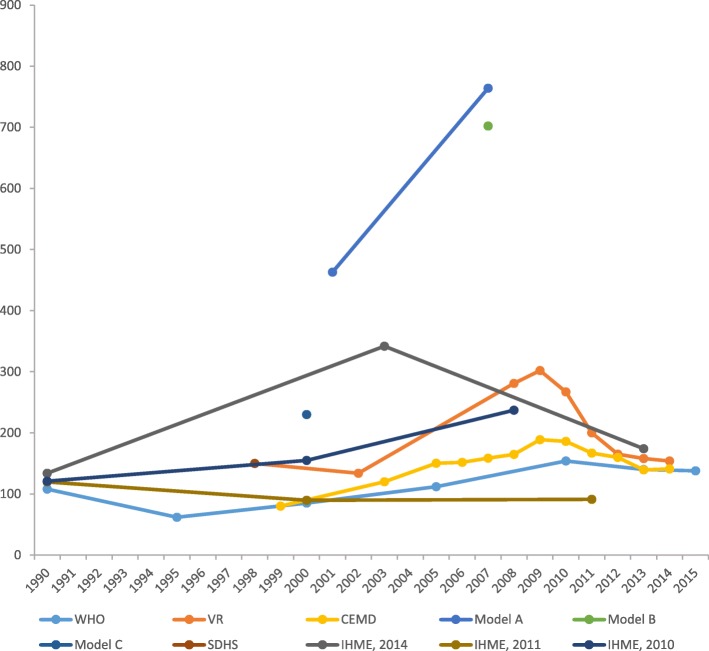

Additionally, estimates of MMR reported by the global metrics (WHO) [68] were divergent from institutional reports (IHME) [41, 43, 69], and most modelled estimates (model A, B and C) [38, 65, 70] are widely divergent from estimates obtained through empirical methods (VR, CEMD and SDHS) [28, 45, 47–49, 51, 52, 55, 67]. The trend in MMR basing on estimates from confidential enquiry (CEMD) [28, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 67] and vital registration (VR) [45–47, 52] shows an increase until a maximum in 2009 followed by a drop in 2010. However, estimates from the vital registration and CEMD appeared to converge over time. Figure 3 shows trends in maternal mortality according to data source and estimation method using most up-to-date estimates superseding all previously published report.

Fig. 3.

Trends in maternal mortality according to data source and estimation method. CEMD Confidential Enquiry to Maternal Deaths, IHME Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, SDHS South Africa Demographic and Health Survey, VR vital registration, WHO World Health Organization

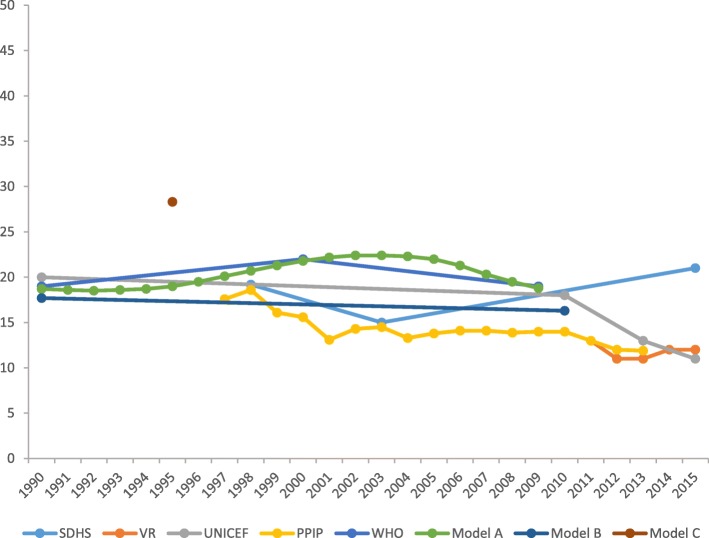

Neonatal mortality

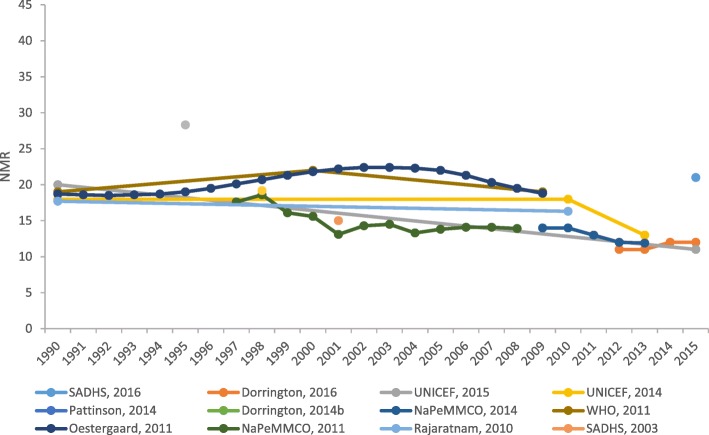

Estimates of NMR from all sources indicate a slightly upward trend over time until 2004, followed by a steady decrease until 2013. Two single-year studies deriving their estimates using empirical [56] and modelling [64] approaches, respectively, reported substantially higher neonatal mortality rates than the others. Figure 4 depicts the trends of neonatal mortality from 1990 to 2015.

Fig. 4.

Trends in neonatal mortality from 1990 to 2015 in South Africa

Furthermore, estimates of NMR from global metrics (WHO and UNICEF) [14, 40, 61] were widely and periodically divergent from institutional reports (PPIP and CEMD) [23, 45, 57–59, 71]. Modelled estimates (WHO; UNICEF; model A, B and C) [14, 40, 61, 63, 64, 72] were large and divergent from estimates obtained through empirical methods (VR, PPIP and SDHS) [23, 45, 55–60, 71], with no clear pattern. The trend in NMR basing on estimates from the PPIP and vital registration shows a slight decline with periodic increase in neonatal mortality from 2000 to 2015 [23, 45, 57–59, 71]. Figure 5 shows trends in neonatal mortality according to data source and estimation method.

Fig. 5.

Trends in neonatal mortality according to data source and estimation method

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This systematic review aimed to provide an overview of maternal and neonatal mortality from 1990 to 2015 for monitoring purposes, tracking progress and to advocate for resources and policy attention. In general, the estimates derived from all studies and reports indicated that South Africa did not achieve the MDG 4a and 5a goals of reducing under-five mortality by two thirds and maternal mortality by three quarters between 1990 and 2015, respectively. Despite the country struggling to achieve the MDG goals for maternal and neonatal mortality in the last two decades, recent reports showed significant progress made in reducing these outcomes [45, 68, 73].

Broad trends

Although maternal and neonatal mortality are highly researched by both local and international authors or institutions in South Africa, there are considerable uncertainties around these estimates in the country. The possible reason for this might be high reliance on only a few data sources and limited empirical work. Accounting for the uncertainties about the actual levels of MMR and NMR in the country, estimates from both the institutional reports and global metrics indicated an upward trend in MMR and NMR until around 2006 and 2009. However, the increase in MMRs between 2001 and 2006 might specifically be explained by a consistent increase in HIV prevalence among pregnant women in the same period [74]. In addition, the downward trends in MMRs and NMRs from 2009 can be linked with the massive uptake of HIV treatment and an increased coverage of essential interventions, in particular the prevention of mother-to-child transmissions (PMTCT) of HIV which currently stands at over 90% [29, 30]. Nonetheless, all recent estimates are much more closely grouped indicating convergence over time.

Challenges in measuring maternal and neonatal mortality

Evidence from the literature indicated that empirical methods, i.e. vital registration, household surveys and censuses, are subjected to misclassification and under-reporting of maternal deaths, thus leading to wide uncertainty intervals. Furthermore, estimating neonatal mortality from census and household surveys in high HIV prevalence settings is known to provide a biased estimate of child mortality due to correlations between HIV deaths in mother and death of her child [70].

Highly variable estimates

Large margins of uncertainty associated with the estimated MMR and NMR highlight the need of interpreting these estimates with caution as well as not using them for monitoring trends over a short duration. The reasons for variations in the estimates of maternal and neonatal mortality remain poorly researched over the past two decades. In this review, we have observed a substantial discrepancy in the consistency of definitions used in the estimation of these outcomes, such as differentiating maternal deaths from pregnancy-related deaths [52, 65, 66]. Thus, uncertainties in estimates of MMR might be partly explained by differences in definitions used. Different estimation techniques used to obtain MMR and NMR necessitated the use of different data inputs, i.e. empirical data versus modelled estimates, which likely contributed to the divergent estimates of these outcomes.

For these reasons, cross-country comparisons, comparisons based on data from different sources and assessments of the overall burden become difficult. These comparisons should in many cases be interpreted with considerable caution due to different strategies being employed to derive such estimates. Evidence from recent studies focusing on estimating child mortality have revealed that methodological differences bias and compromise international comparisons of perinatal mortality [75–77]. Moreover, divergent estimates of MMR and NMR by different sources compromise interpretation of trends over time.

Improving estimates

Over the past three decades, efforts have been made to improve the quality of maternal and neonatal mortality data due to the incompleteness of vital registration systems as well as the lack of reliable population surveys collecting detailed information on birth histories in the country. This included the introduction of modules about sibling history in national household surveys (e.g. Demographic and Health Survey (DHS)), including questions in censuses about whether a woman’s death was related to pregnancy, and the use of mixed methods cross-referencing facility records to determine the extent of under-registration of maternal deaths in vital registration system [4, 7, 78, 79]. However, these improvements could also have contributed to the increasing maternal and neonatal mortality over time.

Despite improvements in the completeness of death registrations in the last decade, the completeness of death registration has been reported to be lower in children as compared to adults and in rural areas than urban [79]. This might potentially explain some of the variability in estimates of both maternal and neonatal mortality in the country.

Generally, this review has revealed divergent estimates of MMR and NMR obtained from vital registration, household surveys, censuses and modelling over time. To obtain more accurate estimates, there is a need for applying additional estimation techniques which utilise available multiple data sources to correct for the underreporting of these outcomes, perhaps the capture-recapture method. This method is useful in resolving uncertainties in estimating conditions that have diverse estimates by operationalising statistically overlapping information from multiple data sources [80–84].

Conclusions

Estimates from the global metrics and institutional reporting, although widely divergent, indicate South Africa has not achieved the MDG targets for maternal and neonatal mortality but made significant progress in reducing these outcomes in the last decade. Discrepancies in data sources and quality from which these estimates were obtained and highly variable estimates highlight the existence of uncertainties about the true estimates of maternal and child mortality in South Africa. In order to track progress and monitor the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the goal for health care for all by 2030, the country needs accurate, reliable, continuous and timely mortality statistics from the vital registration system, a clear understanding of any under-ascertainment of maternal or neonatal mortality and consistent approaches to accounting for these. It would be ideal if global agencies worked closely with local researchers to agree on the optimal calibration of South African estimates in multi-country models.

Additional file

Records of literature review search strategy. (DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarians at School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, for their professional support and guidance during the literature searches.

Funding

Although this review was not funded, we wish to acknowledge the support of the Socio-behavioral Sciences Research to Improve Care for HIV Infection in Tanzania - a National Institutes of Health funded programme (Grant # D43-TW009595) for a scholarship award to undertake PhD studies which inspired the present work.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

DJD and AB conceived the study. DJD, BN and EL conducted the literature search, study selection and data extractions. DJD, BN, EL, SEM and AB contributed in reviewing the manuscript for intellectual content. DJD, BN, EL, SEM and AB contributed towards the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Damian J. Damian, Email: dmndam001@myuct.ac.za

Bernard Njau, Email: njxber001@myuct.ac.za.

Ester Lisasi, Email: lssest001@myuct.ac.za.

Sia E. Msuya, Email: siamsuya@hotmail.com

Andrew Boulle, Email: andrew.boulle@uct.ac.za.

References

- 1.United Nations. Handbook on training in civil registration and vital statistics systems, vol. 281. NewYork: United Nations; 2002.

- 2.Atrash HK, Alexander S, Berg CJ. Maternal mortality in developed countries: not just a concern of the past. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:700–705. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00200-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill K, et al. How should we measure maternal mortality in the developing world? A comparison of household deaths and sibling history approaches. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:173–180. doi: 10.2471/BLT.05.027714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanton C, et al. Every death counts: measurement of maternal mortality via a census. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:657–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. WHO guidance for measuring maternal mortality from a census. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2008.

- 6.Leitao J, et al. Revising the WHO verbal autopsy instrument to facilitate routine cause-of-death monitoring. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:21518. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham W. The sisterhood method for estimating maternal mortality. Mothers Child. 1989;8:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merdad L, Hill K, Graham W. Improving the measurement of maternal mortality: the sisterhood method revisited. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank & United Nations Population Division . Trends in maternal mortality 1990 to 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham WJ. Now or never: the case for measuring maternal mortality. Lancet. 2002;359:701–704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg C, Danel I, Mora G, eds. Guidelines for maternal mortality epidemiologic surveillance. Washington, DC, Pan American Health Organization, (English and Spanish); 1996.

- 12.Walker N, Hill K, Zhao F. Child mortality estimation: methods used to adjust for bias due to AIDS in estimating trends in under-five mortality. PLoS Med. 2012;9(8):e1001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Silva R. Child mortality estimation: consistency of under-five mortality rate estimates using full birth histories and summary birth histories. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank group & United Nations. Levels & trends in child mortality-report 2015: estimates developed by the UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation: UNICEF; 2015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144443.

- 15.Moodley J. Saving mothers 2011–2013: sixth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa, short report. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassebaum NJ, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:957–979. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleem S, et al. A prospective study of maternal, fetal and neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:605–612. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.127464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw D, et al. Every death counts: use of mortality audit data for decision making to save the lives of mothers, babies, and children in South Africa. Lancet. 2008;371:1294–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moodley J, et al. The confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in South Africa: a case study. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:53–60. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chopra M, Daviaud E, Pattinson R, Fonn S, Lawn JE. Saving the lives of South Africa’s mothers, babies, and children: can the health system deliver? Lancet. 2009;374:835–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souza JP, et al. Moving beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2013;381:1747–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pattinson P, Rhoda N, PPIP Group. Saving babies 2012-2013: ninth report on perinatal care in South Africa. Pretoria: Tshepesa Press; 2014.

- 24.Domingo-Salvany A, et al. Analytical considerations in the use of capture-recapture to estimate prevalence: case studies of the estimation of opiate use in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, Spain. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998;148:732–740. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AbouZahr C. New estimates of maternal mortality and how to interpret them: choice or confusion? Reprod Health Matters. 2011;19:117–128. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazil N, Wilmoth J. A comparison of UN and IHME maternal mortality estimates. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Republic of South Africa . Termination of Pregnancy Act. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Committee for Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. Saving mothers 2008-2010: fifth comprehensive report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer; 2012.

- 29.UNAIDS . On the fast-track to an AIDS-free generation. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.UNAIDS . Global AIDS update. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damian DJ, Njau B, Lisasi E, Msuya SE, Boulle A. Trends in maternal and neonatal mortality in South Africa: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017;6:165. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamseer L, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Br Med J. 2015;349:g7647. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. International Classification of Diseases (ICD): eleventh revision instruction manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- 35.WHO. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Organization (2015). ISBN 978 92 4 156514 1.

- 36.World Health Organization . Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013 executive summary. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kassebaum NJ, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):980–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Udjo EO, Lalthapersad-Pillay P. Estimating maternal mortality and causes in South Africa: national and provincial levels. Midwifery. 2014;30:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO, World Bank, UNICEF & United Nations Population Fund. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

- 40.WHO. World health statisitics 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- 41.Lozano R, et al. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1139–1165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA & Bank, T. W. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. World Health Organ. 2010.

- 43.Hogan MC, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375:1609–1623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abouzahr C, Wardlaw T. Maternal mortality at the end of a decade: signs of progress? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001;79(6):561–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Dorrington R, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Nannan N. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2015. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Statistics South Africa . Millennium Development Goals 5: improve maternal health 2015 / Statistics South Africa. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorrington R, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Nannan N. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2014. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Department of Health . 2014 saving mothers: annual report and detailed analysis of maternal deaths due to non-pregnancy related infections. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths . Saving mothers 2011–2013: sixth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa short report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Statistics South Africa . Census 2011: estimation of mortality in South Africa. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.NCCEMD. Saving mothers 2005-2007: fourth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa. Health (San Francisco) (2008).

- 52.Garenne M, McCaa R, Nacro K. Maternal mortality in South Africa in 2001: from demographic census to epidemiological investigation. Popul Health Metrics. 2008;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moodley J. Saving mothers: 1999–2001. SAMJ South African Med J. 2003;93:364–66. [PubMed]

- 54.Moodley J. Saving mothers in South Africa. South Afr J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;6:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Department of Health, Medical Research Council & Measure DHS . South Africa Demographic and Health Survey: final report. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa Council (Stats SA), South African Medical Research (SAMRC) & ICF . South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016: key indicators. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dorrington R, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2012. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58.National perinatal morbidity and mortality committee . National perinatal morbidity and mortality committee report 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 59.NAPEMMCO . National perinatal mortality and morbidity committee (NaPeMMCo) triennial report (2008–2010) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Department of Health, Medical Research Council & OrcMacro . South African Demographic and Health Survey - 2003: full report. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, U . Levels & trends in child mortality in 2014- report: estimates developed by the UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oestergaard MZ, et al. Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rajaratnam JK, et al. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4. Lancet (London, England) 2010;375:1988–2008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60703-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hyder AA, Wali SA, McGuckin J. The burden of disease from neonatal mortality: a review of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;110:894–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garenne M, McCaa R, Nacro K. Maternal mortality in South Africa: an update from the 2007 community survey. J Popul Res. 2011;28:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s12546-010-9037-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hill K, AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Estimates of maternal mortality for 1995. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:182–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pattinson RC, Fawcus S, Moodley J. Tenth interim report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 68.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group & The United Nations Population Division . Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kassebaum NJ, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.AbouZahra C, Wardlawb T. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nannan N, et al. Under-5 mortality statistics in South Africa: shedding some light on the trends and causes 1997–2007. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oestergaard MZ, et al. Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8):e1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UN-DESA Population Division. Levels and trends in child mortality 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- 74.Statistics South Africa . Millennium Development Goals 6: combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Su B-H, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from Taiwan: comparison with Canada, Japan, and the USA. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hossain S, et al. Outborns or inborns: where are the differences? A comparison study of very preterm neonatal intensive care unit infants cared for in Australia and New Zealand and in Canada. Neonatology. 2016;109:76–84. doi: 10.1159/000441272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joseph KS, Razaz N, Muraca GM, Lisonkova S. Methodological challenges in international comparisons of perinatal mortality. Curr Epidemiol Reports. 2017;4:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s40471-017-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stanton C, Abderrahim N, Hill K. An assessment of DHS maternal mortality indicators. Stud Fam Plan. 2000;31(2):111–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Nannan N, et al. Under-5 mortality statistics in south africa: shedding some light on the trend and causes. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Forecasting, International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forecasting and capture-recapture and multiple-record systems estimation I: history and theoretical development. International Working Group for Disease Monitoring and Forecasting. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1047–58. [PubMed]

- 81.Sekar CC, Deming WE. On a method of estimating birth and death rates and the extent of registration (excerpt) Am Stat. 2004;58:13–15. doi: 10.1198/0003130042935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wittes J, Sidel VW. A generalization of the simple capture-recapture model with applications to epidemiological research. J Chronic Dis. 1968;21:287–301. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(68)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fienberg SE. The multiple recapture census for closed populations and incomplete 2 k contingency tables. Biometrika. 1972;59:591. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chao A, Tsay PK, Lin SH, Shau WY, Chao DY. The applications of capture-recapture models to epidemiological data. Stat Med. 2001;20:3123–3157. doi: 10.1002/sim.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.WHO . International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Records of literature review search strategy. (DOCX 19 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.