Key Points

Question

Is consuming dietary cholesterol or eggs associated with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality?

Findings

Among 29 615 adults pooled from 6 prospective cohort studies in the United States with a median follow-up of 17.5 years, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.17; adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 3.24%) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.18; adjusted ARD, 4.43%), and each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.06; adjusted ARD, 1.11%) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08; adjusted ARD, 1.93%).

Meaning

Among US adults, higher consumption of dietary cholesterol or eggs was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD and all-cause mortality in a dose-response manner.

Abstract

Importance

Cholesterol is a common nutrient in the human diet and eggs are a major source of dietary cholesterol. Whether dietary cholesterol or egg consumption is associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality remains controversial.

Objective

To determine the associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Individual participant data were pooled from 6 prospective US cohorts using data collected between March 25, 1985, and August 31, 2016. Self-reported diet data were harmonized using a standardized protocol.

Exposures

Dietary cholesterol (mg/day) or egg consumption (number/day).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hazard ratio (HR) and absolute risk difference (ARD) over the entire follow-up for incident CVD (composite of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and other CVD deaths) and all-cause mortality, adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors.

Results

This analysis included 29 615 participants (mean [SD] age, 51.6 [13.5] years at baseline) of whom 13 299 (44.9%) were men and 9204 (31.1%) were black. During a median follow-up of 17.5 years (interquartile range, 13.0-21.7; maximum, 31.3), there were 5400 incident CVD events and 6132 all-cause deaths. The associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality were monotonic (all P values for nonlinear terms, .19-.83). Each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.09-1.26]; adjusted ARD, 3.24% [95% CI, 1.39%-5.08%]) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.10-1.26]; adjusted ARD, 4.43% [95% CI, 2.51%-6.36%]). Each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 1.03-1.10]; adjusted ARD, 1.11% [95% CI, 0.32%-1.89%]) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.04-1.11]; adjusted ARD, 1.93% [95% CI, 1.10%-2.76%]). The associations between egg consumption and incident CVD (adjusted HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.93-1.05]; adjusted ARD, −0.47% [95% CI, −1.83% to 0.88%]) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.97-1.09]; adjusted ARD, 0.71% [95% CI, −0.85% to 2.28%]) were no longer significant after adjusting for dietary cholesterol consumption.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among US adults, higher consumption of dietary cholesterol or eggs was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD and all-cause mortality in a dose-response manner. These results should be considered in the development of dietary guidelines and updates.

This pooled cohort study reports that consumption of an additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol per day or an additional half egg per day is significantly associated with higher risk of incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and all-cause mortality.

Introduction

The associations between dietary cholesterol consumption and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality remain controversial despite decades of research.1 The debate has intensified recently due to the inclusion of 2 seemingly contradictory statements in the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans2,3: (1) “Cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption”; and (2) “Individuals should eat as little dietary cholesterol as possible while consuming a healthy eating pattern.” The most recent meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies could not draw meaningful conclusions about the association between dietary cholesterol consumption and CVD, primarily due to sparse data, between-study heterogeneity, and lack of methodologic rigor of the reviewed studies.1

Cholesterol, saturated fat, and animal protein often coexist in foods.2 The interaction and independence between dietary cholesterol and these nutrients in relation to CVD and mortality remain uncertain. Further, it is unclear whether eating an overall high-quality diet attenuates the associations of dietary cholesterol consumption with CVD and mortality or if the food source of cholesterol (eg, eggs, red meat, poultry, fish, and dairy products) is important. Eggs, specially the yolk, are a major source of dietary cholesterol; a large egg (≈50 g) contains approximately 186 mg of cholesterol.4 Reported associations of egg consumption with CVD and mortality have been inconsistent overall and by subtypes of these events.5,6,7,8,9,10

Individual participant data were pooled from 6 cohorts from the Lifetime Risk Pooling Project to address the aforementioned gaps.11 The primary objective was to determine the associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Northwestern University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for initial data collection in each original cohort. For this analysis of deidentified data, specific consent was not required.

Study Sample

The Lifetime Risk Pooling Project included 20 community-based prospective cohorts of US participants primarily for the study of long-term risks and development patterns of CVD over the life course in adults.11 Six cohorts that each assessed usual dietary intake and had information on key study variables (see following Methods subsections) were included in this analysis. The cohorts were the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study,12 Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study,13 Framingham Heart Study (FHS),14 Framingham Offspring Study (FOS),15 Jackson Heart Study (JHS),16 and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).17 Participants were excluded if they had CVD at baseline, self-reported energy intake less than 500 kcal per day or greater than 6000 kcal per day, or had missing data for any of the study variables.

Diet Data Assessment

Using a standardized protocol and data dictionary, diet data were harmonized cohort by cohort. Briefly, consumption frequencies were converted into estimated number per day using the middle value (eg, 3-4 times per week = 0.5 times per day). One serving unit was standardized across cohorts. Food groups were constructed using the same definitions. Ingredients in mixed dishes were considered and the appropriate portions were determined for each cohort. The first available diet data collection visit was defined as baseline ranging between 1985 in CARDIA and 2005 in JHS. Only baseline measures were included for this study. Additional details are provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Outcome Ascertainment

The primary outcomes were incident CVD and all-cause mortality. Incident CVD was a composite end point of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, heart failure, and CVD death from other causes. Secondary outcomes were CHD, stroke, heart failure, CVD mortality, and non-CVD mortality. The included cohorts used similar ascertainment and adjudication criteria for CVD and mortality events. Vital status was known for 98% of the participants. The adjudication criteria included International Classification of Diseases codes (versions 8, 9, or 10); diagnostic procedures; and review of medical records, autopsy data, or both. Methods for adjudication have been described in ARIC,12 CARDIA,18 FHS,19 FOS,19 JHS,20 and MESA,17 as well as in the Lifetime Risk Pooling Project.11,21,22,23 The most recent follow-up ended on August 31, 2016.

Covariate Assessment

Standardized questionnaires and laboratory protocols were used to collect information on the following variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, lifestyle factors (including smoking, alcohol intake, and physical activity), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), blood pressure, lipid profile, medication use, and medical conditions. These details have been described elsewhere for each cohort.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 The earliest baseline date was March 25, 1985. Race/ethnicity was self-reported and dichotomized as black and nonblack for subgroup analysis (race/ethnicity breakdown of participants: white [62.1%], black [31.1%], Hispanic [4.4%], Chinese [2.4%]).

Statistical Analysis

Cohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models were used to determine the associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD, CVD subtypes, and cause-specific mortality. Cause-specific hazard models take into consideration competing risks by removing individuals who develop a competing event from the risk set; this technique has been recommended for studying the etiology of an association in the presence of competing risks.24,25 Cohort-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used for analyzing all-cause mortality outcome. Proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Kolmogorov-type supremum test.26 There was no evidence of violation of the proportionality assumption (P value > .05) except for the association between egg consumption and mortality, which was corrected by conducting cohort- and sex-stratified analyses. Models were sequentially adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, some college or more) (model 1); plus total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol intake (gram), use of hormone therapy (y/n) (model 2); plus BMI, diabetes status (y/n), systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications (y/n), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and use of lipid-lowering medications (y/n) (model 3). Model 2 was the primary model because model 3 risk factors may be in the causal pathway. To increase the applicability of the study results to the contemporary US population, the interpretation was based on consuming each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol per day or half an egg per day (equivalent to consumption of 1 egg 3-4 times per week or total consumption of 3-4 eggs per week) because mean dietary cholesterol consumption in the United States was 293 mg per day27 and mean egg consumption was 25.5 g per day28 based on data from recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. One large egg weighs approximately 50 g.4 Estimates were also provided based on other units: each 50-mg per day dietary cholesterol increment up to 600 mg per day and each 1-egg per week increment up to 2 eggs per day. To test for statistically significant departure from a linear association, polynomial terms were added to model 2. If model fit was significantly improved, exposures were converted into 5-category variables. Otherwise, dietary exposures were included as single linear terms on each exposure’s original measurement scale. The distributions of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption were winsorized at the 0.5 and 99.5 percentiles before modeling.

To evaluate the associations of dietary cholesterol consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality, nutrients correlated with dietary cholesterol (saturated fat, unsaturated fat, trans fat, animal protein, fiber, and sodium) were adjusted individually or in combination, in addition to model 2 covariates. To determine if certain cholesterol-containing foods were major determinants for the associations, eggs, processed meat, unprocessed red meat, fish, poultry, and total dairy products were adjusted individually or in combination. For the associations of egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality, dietary cholesterol consumption was further adjusted.

To further evaluate whether consuming dietary cholesterol or eggs within different dietary patterns altered the associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality, major food groups were adjusted in addition to model 2 covariates, either individually or incorporated into 3 scores: the alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (aHEI-2010) score,29 alternate Mediterranean diet score,30 and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension score.31 Cholesterol-containing foods such as meat and fish were removed from calculating these scores. All aforementioned analyses were performed for incident CVD overall, as well as separately by event-type (CHD, stroke, heart failure), and for all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and non-CVD mortality.

Subgroup analyses were performed for incident CVD and all-cause mortality outcomes by the following variables: age (<65, ≥65 years), sex (men, women), race/ethnicity (black, non-black), smoking status (never, former, current), weight status (normal/underweight [BMI <25], overweight [BMI ≥25-<30], obese [BMI ≥30]), diabetes (y/n; defined as having fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL or HbA1c ≥6.5% or taking glucose-lowering medications), hypertension (y/n; defined as ≥140/90 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive medications), hyperlipidemia (y/n; defined as having total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL or taking lipid-lowering medications), low lipids (y/n; defined as not taking lipid-lowering medications and having low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol <70 mg/dL or non-HDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL), higher-quality diet (y/n; defined as consuming a diet with aHEI-2010 score in the highest quartile [≥51.5; score range, 0-100]), high–saturated fat diet (y/n; defined as percent of energy consumed from saturated fat in the highest quartile [≥ 13.8%]), and low–saturated fat diet (y/n; defined as percent of energy consumed from saturated fat <7%). The joint test was used to obtain a P value for interaction for examining statistical significance of the difference between subgroups.32

An absolute risk difference (ARD) was calculated for each hazard ratio (HR) derived from the previously described models. Specifically, we used the mean of the included covariates and calculated the difference in absolute risk at the maximum follow-up time given each additional 300 mg dietary cholesterol consumed per day or 0.5 egg consumed per day. Three R packages were used: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec.35 The bootstrap method was applied to derive 95% CIs for ARD based on 100 bootstrap samples.

Six sensitivity analyses were conducted for primary outcomes: (1) events ascertained during the first 2 and 5 years of follow-up were excluded; (2) participants were arbitrarily censored at 10- and 20-year follow-up; (3) multiple imputation by chained equations was applied to impute missing data for study variables36 and events were censored at loss to follow-up; (4) any 1 of the 6 cohorts was dropped out of the analyses; (5) cohort-specific quintiles or convenient categorical cutoffs for dietary cholesterol or egg consumption were used; and (6) subdistribution hazard models were used instead of cause-specific hazard models.24,25 A 2-tailed P value of less than .05 was used to determine the statistical significance. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.5.2.

Results

This study included 29 615 participants with 524 376 person-years of follow-up data (Table). Mean (SD) age was 51.6 (13.5) years at baseline, 9204 (31.1%) were black, 13 299 (44.9%) were men. The 6 cohorts differed considerably in terms of sample size, age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, BMI, and behavioral and clinical CVD risk factors, as well as incident CVD and all-cause mortality rates. Overall median dietary cholesterol consumption was 241 mg per day (interquartile range [IQR], 164-350) and the overall mean (SD) was 285 (184) mg per day. Overall median egg consumption was 0.14 per day (IQR, 0.07-0.43) and the overall mean (SD) was 0.34 (0.46) per day. Participants’ characteristics, according to 5 levels of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption are shown in eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement. The unadjusted incidence per 1000 person-years was 10.9 (95% CI, 10.6-11.2) for incident CVD and 11.7 (95% CI, 11.4-12.0) for all-cause mortality (eTable3 in the Supplement). The energy-adjusted Pearson correlations between dietary cholesterol or egg consumption and a range of dietary factors are shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Table. Characteristics of the 6 Cohorts Included in This Study.

| ARIC12 (n = 13 710) |

CARDIA13 (n = 4232) |

FHS14 (n = 509) |

FOS15 (n = 2953) |

JHS16 (n = 2313)a |

MESA17 (n = 5898) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 54.3 (5.8) | 25.7 (3.1) | 73.4 (3.0) | 54.2 (9.6) | 49.3 (10.6) | 61.4 (9.6) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Men | 6255 (45.6) | 1847 (43.6) | 174 (34.2) | 1342 (45.4) | 873 (37.7) | 2808 (47.6) |

| Women | 7455 (54.4) | 2385 (56.4) | 335 (65.8) | 1611 (54.6) | 1440 (62.3) | 3090 (52.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 10 415 (76.0) | 2202 (52.0) | 509 (100) | 2953 (100) | 0 | 2325 (39.4) |

| Black | 3295 (24.0) | 2030 (48.0) | 0 | 0 | 2313 (100) | 1566 (26.6) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1310 (22.2) |

| Chinese | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 697 (11.8) |

| Education level, No. (%) | ||||||

| <High school | 3172 (23.1) | 314 (7.4) | 136 (26.7) | 318 (10.8) | 259 (11.2) | 1047 (17.8) |

| High school | 4480 (32.7) | 1107 (26.2) | 199 (39.1) | 967 (32.7) | 387 (16.7) | 1025 (17.4) |

| ≥Some college | 6058 (44.2) | 2811 (66.4) | 174 (34.2) | 1668 (56.5) | 1667 (72.1) | 3826 (64.9) |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 5624 (41.0) | 2352 (55.6) | 457 (89.8) | 2385 (80.8) | 1673 (72.3) | 2952 (50.1) |

| Current smoker | 3601 (26.3) | 1263 (29.8) | 52 (10.2) | 568 (19.2) | 275 (11.9) | 771 (13.1) |

| Former smoker | 4485 (32.7) | 617 (14.6) | 0 | 0 | 365 (15.8) | 2175 (36.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD)b | 27.7 (5.3) | 24.6 (5.1) | 26.6 (4.7) | 27.3 (4.8) | 31.9 (7.3) | 28.3 (5.4) |

| SBP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 121.1 (18.7) | 110.4 (10.9) | 146 (20.6) | 125.0 (18.1) | 124.4 (15.3) | 125.9 (20.9) |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 51.4 (17.0) | 53.2 (13.3) | 50.2 (16.6) | 50.4 (15.0) | 50.5 (13.6) | 51.0 (14.9) |

| Non–HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 163.9 (44.0) | 124.8 (34.0) | 169.3 (39.8) | 154.4 (38.2) | 146.6 (39.2) | 143.4 (35.5) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 1484 (10.8) | 33 (0.8) | 49 (9.6) | 178 (6.0) | 254 (11.0) | 729 (12.4) |

| Antihypertensive medication use, No (%) | 4246 (31.0) | 106 (2.5) | 219 (43.0) | 502 (17.0) | 933 (40.3) | 2140 (36.3) |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, No. (%) | 411 (3.0) | 0 | 30 (5.9) | 182 (6.2) | 169 (7.3) | 948 (16.1) |

| Hormone therapy use, No. (%) | 1385 (10.1) | 104 (2.5) | 25 (4.9) | 304 (10.3) | 324 (14.0) | 913 (15.5) |

| Total energy, median (IQR), kcal/d | 1534 (1189-1960) | 2460 (1802-3348) | 1676 (1299-2047) | 1786 (1413-2233) | 1999 (1446-2736) | 1515 (1095-2065) |

| Eggs, median (IQR), No./dc | 0.14 (0.07-0.43) | 0.42 (0.17-0.87) | 0.14 (0.07-0.43) | 0.14 (0.07-0.43) | 0.32 (0.09-0.65) | 0.14 (0.04-0.29) |

| Dietary cholesterol, median (IQR), mg/dd | 227 (162-312) | 384 (259-567) | 221 (152-308) | 209 (153-280) | 306 (196-473) | 209 (133-326) |

| Alcohol, median (IQR), g/d | 0 (0-6.2) | 4.7 (0.6-13.8) | 1.2 (0-13.2) | 3.2 (0-13.2) | 0.1 (0-1.7) | 0.5 (0.1-5.3) |

| aHEI-2010 score, mean (SD)e | 40.6 (8.7) | 43.4 (11.1) | 50.9 (9.6) | 45.8 (9.4) | 51.3 (10.3) | 51.0 (9.8) |

| Incident CVDf | ||||||

| No. of events | 3798 | 212 | 230 | 361 | 118 | 681 |

| Follow-up, y | 236 084 | 121 092 | 5831 | 40 605 | 22 144 | 71 562 |

| Rate/1000 person-y | 16.1 | 1.8 | 39.4 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 9.5 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||||

| No. of events | 4089 | 321 | 377 | 368 | 93 | 884 |

| Follow-up, y | 255 894 | 122 424 | 6777 | 42 405 | 22 562 | 74 314 |

| Rate/1000 person-y | 16.0 | 2.6 | 55.6 | 8.7 | 4.1 | 11.9 |

Abbreviations: aHEI, alternate Healthy Eating Index; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; BMI, body mass index; CARDIA, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; FOS, Framingham Offspring Study; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; IQR, interquartile range; JHS, Jackson Heart Study; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

There were 1570 participants from the JHS who were excluded because they also participated in the ARIC study.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

The overall median number of eggs consumed per day was 0.14 (IQR, 0.07-0.43), and the mean (SD) was 0.34 (0.46).

The overall median of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was 241 mg (IQR, 164-350), and the mean (SD) was 285 (184).

Unprocessed red meat and processed meat were excluded from the calculation because they are cholesterol-containing foods. The original version of the aHEI-2010 score has a range of 0 to 110 points. The aHEI-2010 score in this study had a range of 0 to 100 points due to the removal of the meat item. A higher score indicates higher diet quality. There are currently no established cutoffs for defining high or low diet quality based on this score. A score of approximately 40 to 50 was considered as poor diet quality according to a recent investigation using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.37

Incident CVD events included fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and other CVD deaths.

Primary Outcomes: Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality

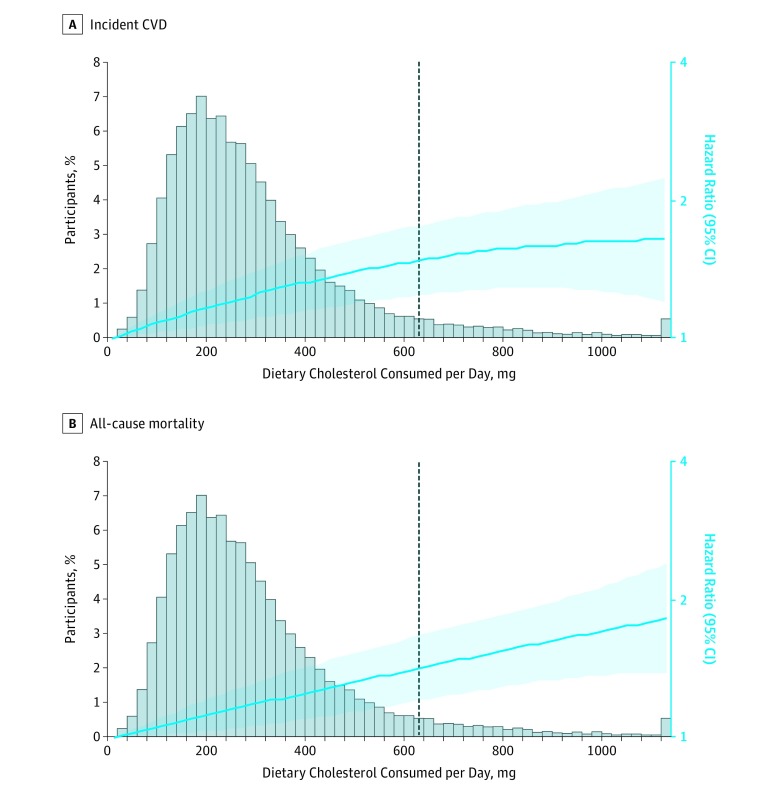

During a median follow-up of 17.5 years (IQR, 13.0-21.7; maximum 31.3), there were a total of 5400 incident CVD events (2088 fatal and nonfatal CHD events, 1302 fatal and nonfatal stroke events, 1897 fatal and nonfatal heart failure events, and 113 other CVD deaths) and 6132 all-cause deaths. The associations between dietary cholesterol consumption and incident CVD and all-cause mortality were monotonic (P value >.1 for quadratic cholesterol term; Figure 1). Based on model 2, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.09-1.26]; adjusted ARD, 3.24% [95% CI, 1.39%-5.08%]; Figure 2A) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.10-1.26]; adjusted ARD, 4.43% [95% CI, 2.51%-6.36%]; Figure 2B). These associations remained significant after further adjusting for CVD risk factors (eg, BMI, diabetes, blood pressure, and serum lipids), dietary fats, animal protein, fiber, sodium, cholesterol-containing foods, or dietary patterns with 2 exceptions: (1) the associations between dietary cholesterol consumption and incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 0.97-1.31]; adjusted ARD, 2.79% [95% CI, −0.76% to 6.34%]) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.92-1.21]; adjusted ARD, 1.25% [95% CI, −2.65% to 5.15%]) were no longer significant after adjusting for consumption of eggs, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat; and (2) the association between dietary cholesterol consumption and all-cause mortality was no longer significant after adjusting for egg consumption (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 0.99-1.27]; adjusted ARD, 3.05% [95% CI, −0.59% to 6.70%]).

Figure 1. Associations Between Dietary Cholesterol Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality.

There were 5400 incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and 6132 all-cause deaths (N=29 615 participants). Incident CVD included fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and other CVD deaths. Cohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models for incident CVD and standard proportional hazard models for all-cause mortality were applied and included dietary cholesterol, dietary cholesterol squared, age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n). The dashed line indicates the cutoff for the 95th percentile of consumption (640 mg/d). The distribution of dietary cholesterol was winsorized at the 0.5 and 99.5 percentiles. For quadratic cholesterol consumption term for incident CVD, P value = .19, and for quadratic cholesterol consumption term for all-cause mortality, P value = .83. The hazard ratio (HR [95% CI]) is indicated by the blue line and blue shading.

Figure 2. Associations Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed per Day and Incident CVDand All-Cause Mortality.

See the Figure 1 footnote for conditions included in the incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) definition. There were 5400 incident CVD events and 6132 all-cause deaths (N=29 615 participants). Mean dietary cholesterol consumption in the United States was 293 mg per day.27 For results interpretation, use model 2 as a reference standard (indicated by dotted line). Each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher relative risk (RR) of incident CVD (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.17 [95% CI, 1.09-1.26]) and a higher absolute risk of incident CVD (adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 3.24% [95% CI, 1.39%-5.08%]) over the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years. Each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher RR of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.10-1.26]) and a higher absolute risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted ARD, 4.43% [95% CI, 2.51%-6.36%]) over the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years.

aARD estimation (see Figure 4, footnote “a” for description). The maximum follow-up time of 31.3 years, mean of the included covariates, and a difference of 300 mg per day in dietary cholesterol consumption were used.

bCohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models were used for incident CVD. Cohort-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used for all-cause mortality.

cModels: see Statistical Analysis section for descriptions of models 1, 2, and 3.

dIncluded unprocessed red meat and processed meat (adjusted separately).

eMeat and fish were removed from calculating these dietary scores.

fFruits, legumes, potatoes, other vegetables, nuts and seeds, whole grains, refined grains, low-fat dairy products, and sugar-sweetened beverages were included. Eggs, meat, and fish were excluded (major sources of dietary cholesterol).

See Figure 4 footnote for aHEI-2010, aMED, and DASH term expansions.

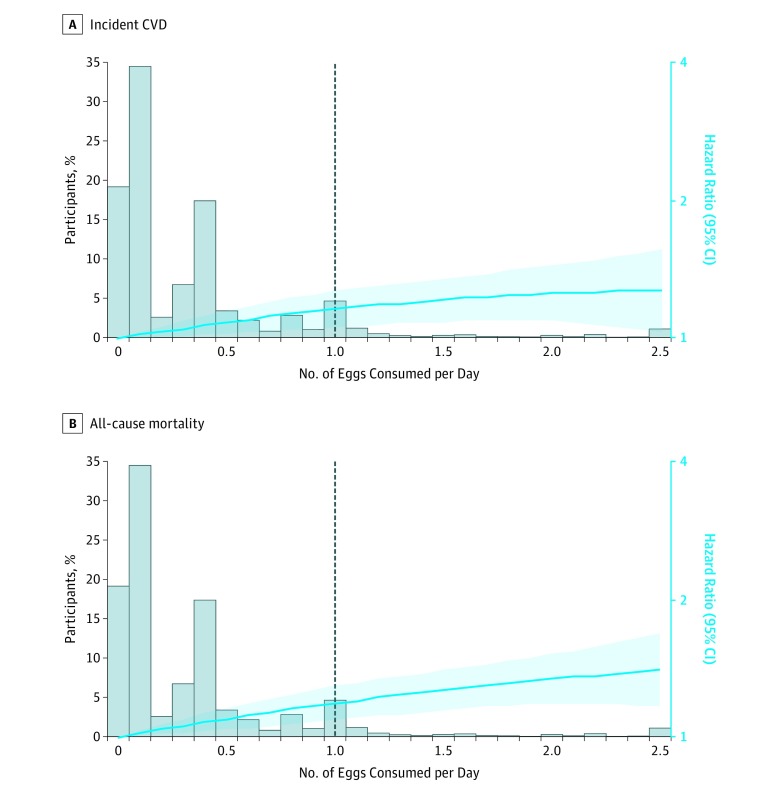

The associations between egg consumption and incident CVD and all-cause mortality were monotonic (P value > .3 for quadratic egg term; Figure 3). Based on model 2, each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 1.03-1.10]; adjusted ARD, 1.11% [95% CI, 0.32%-1.89%]; Figure 4A) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.04-1.11]; adjusted ARD, 1.93% [95% CI, 1.10%-2.76%]; Figure 4B). These associations remained significant after accounting for CVD risk factors, dietary fats, animal protein, fiber, sodium, or dietary patterns. However, the associations between egg consumption and incident CVD (adjusted HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.93-1.05]; adjusted ARD, −0.47% [95% CI, −1.83% to 0.88%]) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.97-1.09]; adjusted ARD, 0.71% [95% CI, −0.85% to 2.28%]) were no longer significant after adjusting for dietary cholesterol consumption.

Figure 3. Associations Between Egg Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality.

There were 5400 incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and 6132 all-cause deaths (N=29 615 participants). See the Figure 1 footnote for conditions included in the incident CVD definition. Cohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models for incident CVD and standard proportional hazard models for all-cause mortality were applied and included egg consumption, egg consumption squared, age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n). The dashed line indicates the cutoff for the 95th percentile of consumption (1 egg/d). For the association between egg consumption and all-cause mortality, cohort- and sex-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used to satisfy proportional hazards assumption. The distribution of egg consumption was winsorized at the 0.5 and 99.5 percentiles. For quadratic egg consumption term for incident CVD, P value = .34 , and for quadratic egg consumption term for all-cause mortality, P value = .48. The hazard ratio (HR [95% CI]) is indicated by the blue line and blue shading.

Figure 4. Associations Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed per Day and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality.

See the Figure 1 footnote for conditions included in the incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) definition. There were 5400 incident CVD events and 6132 all-cause deaths (N=29 615 participants). Mean egg consumption in the United States was approximately half an egg per day.28 For results interpretation, use model 2 as a reference standard (indicated by dotted line).

aAbsolute risk difference was estimated using 3 R packages: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec,35 and 95% CIs were derived from 100 bootstrap samples. The maximum follow-up time of 31.3 years, mean of the included covariates, and a difference of 0.5 per day in egg consumption were used.

bCohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models were used for incident CVD. Cohort-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used for all-cause mortality that were further stratified by sex to satisfy proportional hazards assumption.

cModels: see Statistical Analysis section for descriptions of models 1, 2, and 3.

dMeat and fish were removed from calculating these dietary scores.

eIncluded unprocessed red meat and processed meat (adjusted separately).

fFruits, legumes, potatoes, other vegetables, nuts and seeds, whole grains, refined grains, low-fat dairy products, sugar sweetened beverages, poultry, and fish and seafood.

gFootnote “f” (previous) plus unprocessed red meat, and processed meat.

aHEI-2010 indicates alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010; aMED, alternate Mediterranean; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

The adjusted HRs (95% CIs), calculated using other increment units for dietary cholesterol or egg consumption based on model 2, are shown in eTable 5 and eTable 6 in the Supplement.

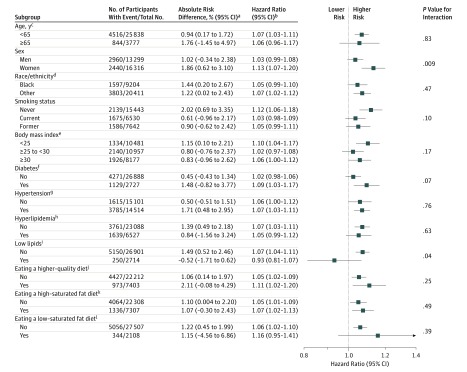

Subgroup Analyses

The association between dietary cholesterol consumption (per 300 mg/day) and incident CVD was stronger in participants with BMI lower than 25 (adjusted HR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.12-1.39]) than in overweight participants (BMI ≥25 to <30; adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.95-1.16]) or obese participants (BMI ≥30; adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.03-1.26]) (P value for interaction, .03) (Figure 5) and stronger in participants without low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 1.19 [95% CI, 1.11-1.28]) than in participants with low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.78-1.19]) (P value for interaction, .04). The association between dietary cholesterol consumption and all-cause mortality was stronger in women (adjusted HR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.17-1.41]) than in men (adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.06-1.22]) (P value for interaction, .02) (Figure 6) and stronger in participants who consumed a high–saturated fat diet (adjusted HR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.13-1.36]) than in participants who did not (adjusted HR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.04-1.21]) (P value for interaction, .046).

Figure 5. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Incident CVD Among Different Subgroups.

See the Figure 1 footnote for conditions included in the incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) definition. Adjustment covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n), where relevant. Mean dietary cholesterol consumption in the United States was 293 mg/d, based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2014 data.27 The results can be interpreted using the following sex-specific estimates as an example: in men, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher relative risk (RR) of incident CVD (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14 [95% CI, 1.05-1.23]) and a higher absolute risk of incident CVD (adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 2.70% [95% CI, 0.08%-5.33%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. In women, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher RR of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.14-1.40]) and a higher absolute risk of incident CVD (adjusted ARD, 5.12% [95% CI, 2.21%-8.02%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. The difference between men and women was borderline significant (P value for interaction = .051).

aAbsolute risk difference was estimated using 3 R packages: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec,35 and 95% CIs were derived from 100 bootstrap samples. A follow-up time of 30 years (not all subgroups had the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years), mean of the included covariates, and a difference of 300 mg per day in dietary cholesterol consumption were used.

bCohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models were used for incident CVD.

cThe maximum follow-up time for the older group was 22.8 years. All other subgroups used 30 years as specified in footnote “a.”

dHispanic and Chinese participants were combined with white participants (all categorized as other) due to small sample size.

eBody mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

fFasting glucose (≥126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (≥6.5%) or taking glucose-lowering medications.

gBlood pressure (≥140/90 mm Hg) or taking antihypertensive medications.

hTotal cholesterol (≥240 mg/dL) or taking lipid-lowering medications.

iLow-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<70 mg/dL) or non–high density lipoprotein cholesterol (<100 mg/dL) among those who did not take lipid-lowering medications.

jAlternate Healthy Eating Index (aHEI) 2010 score in the highest quartile (≥51.5). The original version of the aHEI-2010 score has a range of 0 to 110 points, but the score in this study had a range of 0 to 100 points due to the removal of the meat item.

kPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat in the highest quartile (≥13.8%).

lPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat (<7%).

Figure 6. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed per Day and All-Cause Mortality Among Different Subgroups.

Adjustment covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n), where relevant. Mean dietary cholesterol consumption in the United States was 293 mg/d, based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2014 data.27 The results can be interpreted using the following sex-specific estimates as an example: in men, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher relative risk (RR) of all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.14 [95% CI, 1.06-1.22]) and a higher absolute risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 3.28% [95% CI, 0.80%-5.77%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. In women, each additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher RR of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.17-1.41]) and a higher absolute risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted ARD, 7.51% [95% CI, 4.20%-10.83%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. The association was stronger in women than in men (P value for interaction = .02).

aAbsolute risk difference was estimated using 3 R packages: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec,35 and 95% CIs were derived from 100 bootstrap samples. A follow-up time of 30 years (not all subgroups had the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years), mean of the included covariates, and a difference of 300 mg per day in dietary cholesterol consumption were used.

bCohort-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used for all-cause mortality.

cThe maximum follow-up time for the older group was 22.8 years. All other subgroups used 30 years as specified in footnote “a.”

dHispanic and Chinese participants were combined with white participants (all categorized as other) due to small sample size.

eBody mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

fFasting glucose (≥126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (≥6.5%) or taking glucose-lowering medications.

gBlood pressure (≥140/90 mm Hg) or taking antihypertensive medications.

hTotal cholesterol (≥240 mg/dL) or taking lipid-lowering medications.

iLow-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<70 mg/dL) or non–high density lipoprotein cholesterol (<100 mg/dL) among those who did not take lipid-lowering medications.

jAlternate Healthy Eating Index (aHEI) 2010 score in the highest quartile (≥51.5). The original version of the aHEI-2010 score has a range of 0 to 110 points, but the score in this study had a range of 0 to 100 points due to the removal of the meat item.

kPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat in the highest quartile (≥13.8%).

lPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat (<7%).

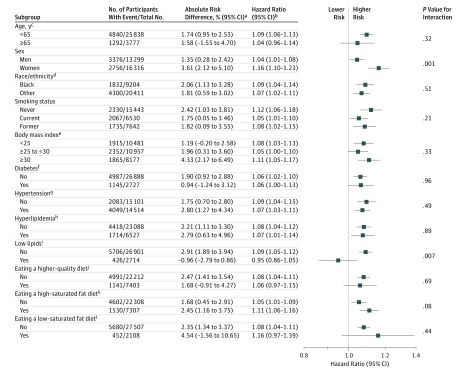

The association between egg consumption (per half an egg/day) and incident CVD was stronger in women (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.07-1.20]) than in men (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.99-1.08]) (P value for interaction, .009; Figure 7) and stronger in participants without low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.04-1.11]) than in participants with low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.81-1.07]) (P value for interaction, .04). The association between egg consumption and all-cause mortality was stronger in women (adjusted HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.10-1.23]) than in men (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.01-1.08]) (P value for interaction, .001) (Figure 8) and stronger in participants without low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.05-1.12] than in participants with low lipid levels (adjusted HR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.86-1.05]) (P value for interaction, .007).

Figure 7. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed per Day and Incident CVD Among Different Subgroups.

See the Figure 1 footnote for conditions included in the incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) definition. Adjustment covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n), where relevant. Mean egg consumption in the United States was approximately half an egg per day, based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012 data.28 The results can be interpreted using the following sex-specific estimates as an example: in men, each additional half an egg consumed per day was not significantly associated with a higher relative risk (RR) of incident CVD (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 [95% CI, 0.99-1.08]) and a higher absolute risk of incident CVD (adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 1.02% [95% CI, −0.34% to 2.38%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. In women, each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher RR of incident CVD (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.07-1.20]) and a higher absolute risk of incident CVD (adjusted ARD, 1.86% [95% CI, 0.62%-3.10%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. The association was stronger in women than in men (P value for interaction = .009).

aAbsolute risk difference was estimated using 3 R packages: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec,35 and 95% CIs were derived from 100 bootstrap samples. A follow-up time of 30 years (not all subgroups had the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years), mean of the included covariates, and a difference of half an egg per day consumed were used.

bCohort-stratified cause-specific hazard models were used for incident CVD.

cThe maximum follow-up time for the older group was 22.8 years. All other subgroups used 30 years as specified in footnote “a.”

dHispanic and Chinese participants were combined with white participants (all categorized as other) due to small sample size.

eBody mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

fFasting glucose (≥126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (≥6.5%) or taking glucose-lowering medications.

gBlood pressure (≥140/90 mm Hg) or taking antihypertensive medications.

hTotal cholesterol (≥240 mg/dL) or taking lipid-lowering medications.

iLow-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<70 mg/dL) or non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (<100 mg/dL) among those who did not take lipid-lowering medications.

jAlternate Healthy Eating Index (aHEI) 2010 score in the highest quartile (≥51.5). The original version of the aHEI-2010 score has a range of 0 to 110 points, but the score in this study had a range of 0 to 100 points due to the removal of the meat item.

kPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat in the highest quartile (≥13.8%).

lPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat (<7%).

Figure 8. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed per Day and All-Cause Mortality Among Different Subgroups.

Adjustment covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Chinese), education (<high school, high school, ≥some college), total energy, smoking status (current, former, never), smoking pack-years (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10-19.9, 20-29.9, 30-39.9, ≥40), cohort-specific physical activity z score, alcohol consumption (gram), and use of hormone therapy (y/n), where relevant. Mean egg consumption in the United States was approximately half an egg per day, based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012 data.28 The results can be interpreted using the following sex-specific estimates as an example: in men, each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher relative risk (RR) of all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.04 [95% CI, 1.01-1.08]) and a higher absolute risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD], 1.35% [95% CI, 0.28%-2.42%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. In women, each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with a higher RR of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.10-1.23]) and a higher absolute risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted ARD, 3.61% [95% CI, 2.12%-5.10%]) over a follow-up of 30 years. The association was stronger in women than in men (P value for interaction = .001).

aAbsolute risk difference was estimated using 3 R packages: riskRegression,33 survival,34 and pec,35 and 95% CIs were derived from 100 bootstrap samples. A follow-up time of 30 years (not all subgroups had the maximum follow-up of 31.3 years), mean of the included covariates, and a difference of half an egg per day consumed were used.

bCohort- and sex-stratified standard proportional hazard models were used for all-cause mortality.

cThe maximum follow-up time for the older group was 22.8 years. All other subgroups used 30 years as specified in footnote “a.”

dHispanic and Chinese participants were combined with white participants (all categorized as other) due to small sample size.

eBody mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

fFasting glucose (≥126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (≥6.5%) or taking glucose-lowering medications.

gBlood pressure (≥140/90 mm Hg) or taking antihypertensive medications.

hTotal cholesterol (≥240 mg/dL) or taking lipid-lowering medications.

iLow-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<70 mg/dL) or non–high density lipoprotein cholesterol (<100 mg/dL) among those who did not take lipid-lowering medications.

jAlternate Healthy Eating Index (aHEI) 2010 score in the highest quartile (≥51.5). The original version of the aHEI-2010 score has a range of 0 to 110 points, but the score in this study had a range of 0 to 100 points due to the removal of the meat item.

kPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat in the highest quartile (≥13.8%).

lPercent of energy consumed from saturated fat (<7%).

Secondary Outcomes: CVD Subtypes and Cause-Specific Mortality

The associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with CVD subtypes and cause-specific mortality were monotonic (P value for quadratic terms >0.1).

CVD Subtypes

Dietary cholesterol (per 300 mg/day; adjusted HR, 1.10 [95% CI, 0.98-1.23]) or egg consumption (per half an egg/day; adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.99-1.11]) was not significantly associated with CHD in model 2 (eFigure 1 and eFigure 6 in the Supplement). Dietary cholesterol consumption was significantly associated with stroke (adjusted HR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.09-1.46]; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). This association was no longer significant after adjusting for egg consumption alone (adjusted HR, 1.19 [95% CI, 0.91-1.57]) or consumption of eggs, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat together (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.75-1.38]). Dietary cholesterol consumption was significantly associated with heart failure (adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.05-1.24]; eFigure 3 in the Supplement). This association was no longer significant after adjusting for CVD risk factors (adjusted HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.98-1.27]) or animal protein consumption (adjusted HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.91-1.23]). Egg consumption was significantly associated with stroke (adjusted HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.03-1.18]; eFigure 7 in the Supplement), but not heart failure (adjusted HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.996-1.12]; eFigure 8 in the Supplement). The association between egg consumption and stroke was no longer significant after adjusting for dietary cholesterol consumption (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.91-1.17]).

Cause-Specific Mortality

Dietary cholesterol consumption was significantly associated with CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.22 [95% CI, 1.07-1.39]; eFigure 4 in the Supplement). This association was no longer significant after adjusting for animal protein consumption (adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 0.91-1.25]), egg consumption (adjusted HR, 1.23 [95% CI, 0.95-1.59]), or consumption of eggs, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 0.85-1.50]). Dietary cholesterol consumption was significantly associated with non-CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.08-1.26]; eFigure 5 in the Supplement). This association was no longer significant after adjusting for egg consumption (adjusted HR, 1.10 [95% CI, 0.95-1.26]) or consumption of eggs, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.88-1.21]). Egg consumption was significantly associated with CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.01-1.15]; eFigure 9 in the Supplement) and non-CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.04-1.11]; eFigure 10 in the Supplement), but these associations were no longer significant after adjusting for dietary cholesterol consumption for CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.88-1.12]) and non-CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.97-1.11]), as well as adjusting for animal protein consumption for CVD mortality (adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.99-1.12])

Sensitivity Analyses

Excluding events within the first 2 and 5 years or censoring participants at 10- and 20-year follow-up did not materially alter the significant associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality (Figure 2; Figure 4). Compared with the included participants (N = 29 615), participants who were excluded (n = 4882) were older (54.4 vs 51.6 years), more likely to be black (42.5% vs 31.1%), and less likely to have an education of some college or more (43.6% vs 54.7%) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). The adjusted HRs (95% CIs) were similar between complete case analyses and multiple imputation-based analyses (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Dropping any 1 of the 6 cohorts did not considerably alter the significant associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality (eTable 9 in the Supplement). These significant associations were similar when the exposure variables were divided into quintiles or by other convenient cutoffs (eTables 10-13 in the Supplement). The adjusted HRs (95% CIs) obtained from subdistribution hazard models were similar to those obtained from cause-specific hazard models (eTable 14 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Among 29 615 adults pooled from 6 prospective cohort studies in the United States with a median follow-up of 17.5 years, higher consumption of dietary cholesterol or eggs was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD and all-cause mortality, in a dose-response manner.

A recent meta-analysis did not report a conclusive association between dietary cholesterol consumption and CVD, primarily due to the heterogeneity of the available studies and sparse data.1 As a major source of dietary cholesterol, egg consumption has been differentially associated with CHD, stroke, heart failure, and mortality. Recent meta-analyses showed that frequent egg consumption (generally ≥1 per day), as compared with infrequent consumption (generally <1 per week or never), was associated with significantly higher risk of heart failure,10 significantly lower risk of stroke,6,8 or no significant association with stroke or stroke mortality,5,7 and higher risk of all-cause mortality (pooled HR 1.09, 95% CI [0.997-1.20]).8 No significant association with CHD was reported.5,6,7,8 Another meta-analysis, which analyzed all CVD subtypes together, reported a significant positive dose-response association between egg consumption and CVD.9 As highlighted by these meta-analyses,1,5,6,7,8,9,10 residual confounding was a potential reason for inconsistent results. For example, egg consumption was commonly correlated with unhealthy behaviors such as low physical activity, current smoking, and unhealthy dietary patterns.38 Also, cholesterol-containing foods are usually rich in saturated fat and animal protein.2 Failure to consider these factors and others could lead to differential conclusions. In contrast, the current study included comprehensive assessment of these factors. Also, the current study had longer follow-up than the majority of the previous studies and may have provided more power to detect associations.1,5,6,7,8,9,10

The current study found that the significant associations of dietary cholesterol consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality were independent of fat amount and quality of the diet. These findings are consistent with the evidence that a reduction of dietary cholesterol intake, in addition to isocaloric replacement of saturated fat by unsaturated fat, was significantly associated with reduced total cholesterol (primarily LDL cholesterol) concentration.39 Further, the significant association between egg consumption and incident CVD was fully accounted for by the cholesterol content in eggs, which also largely explained the significant association between egg consumption and all-cause mortality, offering additional support for the significant associations of dietary cholesterol consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality. Although the significant associations of dietary cholesterol consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality were no longer significant after accounting for egg, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat consumption, it remains unclear if cholesterol from these foods is more harmful than other cholesterol-containing foods. Statistically, the remaining variation in dietary cholesterol consumption from other foods may not be sufficient to materially modify the associations. Egg consumption contributed 25% to the total dietary cholesterol consumption and meat consumption contributed 42%.27 Mechanistically, eggs and processed or unprocessed red meat are rich in other nutrients such as choline, iron, carnitine, and added sodium (for processed meat) that have been implicated in CVD risk via different pathways. Further, the significant associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality were similar between participants who consumed a higher-quality diet and those who did not, suggesting that people may need to minimize dietary cholesterol and egg yolk intake when consuming a healthier eating pattern, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine.40

The magnitudes of the significant associations of dietary cholesterol or egg consumption with incident CVD and all-cause mortality were modest but consistent across event subtypes including stroke, heart failure (except for egg consumption: adjusted HR 1.06, 95% CI [0.996-1.12]), CVD mortality, and non-CVD mortality, as well as for subgroups according to age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, CVD risk factors (ie, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia), and diet quality. The nonsignificant association for CHD was consistent with the literature.5,6,7,8 US mean dietary cholesterol consumption of approximately 290 mg per day is higher than the global average of 228 mg per day,41 and was relatively stable from 2001-2002 to 2013-2014.27 Egg consumption has been relatively low in the United States, but overall per capita egg consumption increased by 11% from 23.0 g per day in 2001-2002 to 25.5 g per day in 2011-2012.28 The recommendations for dietary cholesterol and egg consumption from the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines, if carried forward in subsequent versions of Dietary Guidelines, might lead to further increases in egg and dietary cholesterol consumption in the United States, which could be harmful for prevention of CVD and premature death. Findings of the current study suggest that cholesterol from egg yolk may be harmful in the context of the current US diet, in which overnutrition and overweight/obesity are more common than malnutrition and underweight. This is consistent with the evidence that frequent egg consumption has been significantly associated with diabetes risk only in US studies.42

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, appropriate interpretation of the study findings requires consideration of measurement error for self-reported diet data. Further, this study relied on single measurement of egg and dietary cholesterol consumption. Exposure misclassification may be of concern, but results were similar when censoring participants at different time points. Second, all cohorts used different dietary assessment tools except 2 Framingham cohorts, which created heterogeneities for data analyses. This was addressed by the following: (1) implementing a rigorous methodology to harmonize diet data; (2) performing cohort-stratified analyses; and (3) conducting several sensitivity analyses. Third, residual confounding was likely, although a number of covariates were adjusted. Fourth, data were not available for investigating subtypes of CHD, stroke, and heart failure, as well as more detailed cause-specific mortality such as cancer mortality. Fifth, generalizing our results to non-US populations requires caution due to different nutrition and food environments and chronic disease epidemiology. Sixth, the study findings are observational and cannot establish causality.

Conclusions

Among US adults, higher consumption of dietary cholesterol or eggs was significantly associated with higher risk of incident CVD and all-cause mortality in a dose-response manner. These results should be considered in the development of dietary guidelines and updates.

eAppendix. Description of Diet Data Harmonization Methodology

Harmonization eTable 1. Characteristics of Dietary Intake Assessment in 6 LRPP Cohorts

Harmonization eTable 2. Correlation Coefficients of Selected Nutrients From the Published Validation Studies

Harmonization eTable 3. Food Grouping Rationale in the LRPP

Harmonization eTable 4. Key Nutrients in the LRPP

Harmonization eTable 5. One Serving Size Reference and Conversion Table

Harmonization eTable 6. An Example for Conversion Between Reported Consumption Frequencies and Daily Amount for Data Analysis

Harmonization eReferences. References for Harmonization Methodology Description

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Study Participants According to Different Levels of Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day)

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Study Participants According to Different Levels of Egg Consumption (number/day)

eTable 3. Unadjusted Incidence Rate of Events Overall and by Subtype

eTable 4. Energy-Adjusted Pearson Correlation Between Dietary Cholsterol or Egg Consuption With Other Dietary Factors

eTable 5. Associations Between Dietary Cholesterol Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Various Increment Units for Dietary Cholesterol Consumption

eTable 6. Associations Between Egg Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Various Increment Units for Egg Consumption

eTable 7. Key Characteristics Between the Included and Excluded Participants

eTable 8. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, With Missing Data Imputed by Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations

eTable 9. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, After Excluding Specific Cohort(s)

eTable 10. Associations Between Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day) and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Convenient Cutoffs

eTable 11. Associations Between Quintiles of Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day) and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortalitya

eTable 12. Associations Between Number of Eggs Consumed Per Day and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Convenient Cutoffs

eTable 13. Associations Between Quintiles of Egg Consumption Per Day and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortalitya

eTable 14. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol (300 mg/day) or Egg (half/day) Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality Using Subdistribution Hazard Models

eFigure 1. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Coronary Heart Disease

eFigure 2. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Stroke

eFigure 3. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Heart Failure

eFigure 4. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Cardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 5. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Noncardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 6. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Coronary Heart Disease

eFigure 7. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Stroke

eFigure 8. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Heart Failure

eFigure 9. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Cardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 10. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Noncardiovascular Mortality

References:

- 1.Berger S, Raman G, Vishwanathan R, Jacques PF, Johnson EJ. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(2):276-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 3.Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Washington, DC: US Dept of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. Version Current: September 2015. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 5.Shin JY, Xun P, Nakamura Y, He K. Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):146-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander DD, Miller PE, Vargas AJ, Weed DL, Cohen SS. Meta-analysis of egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016;35(8):704-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rong Y, Chen L, Zhu T, et al. Egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. BMJ. 2013;346:e8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu L, Lam TH, Jiang CQ, et al. Egg consumption and the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study and meta-analyses [published online April 21, 2018]. Eur J Nutr. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1692-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Zhou C, Zhou X, Li L. Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229(2):524-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khawaja O, Singh H, Luni F, et al. Egg consumption and incidence of heart failure. Front Nutr. 2017;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins JT, Karmali KN, Huffman MD, et al. Data resource profile: the Cardiovascular Disease Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(5):1557-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The ARIC Investigators .The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687-702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong ND, Levy D. Legacy of the Framingham Heart Study: rationale, design, initial findings, and implications. Glob Heart. 2013;8(1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study: design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4(4):518-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor HA Jr, Wilson JG, Jones DW, et al. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4)(suppl 6):4-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):871-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano Y, Reis JP, Colangelo LA, et al. Association of blood pressure classification in young adults using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guideline with cardiovascular events later in life. JAMA. 2018;320(17):1774-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsao CW, Vasan RS. Cohort profile: the Framingham Heart Study (FHS): overview of milestones in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(6):1800-1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keku E, Rosamond W, Taylor HA Jr, et al. Cardiovascular disease event classification in the Jackson Heart Study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4)(suppl 6):62-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry JD, Dyer A, Cai X, et al. Lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(4):321-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huffman MD, Berry JD, Ning H, et al. Lifetime risk for heart failure among white and black Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(14):1510-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkins JT, Ning H, Berry J, et al. Lifetime risk and years lived free of total cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1795-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):244-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the cox model with cumulative sums of martingale-based residuals. Biometrika. 1993;80(3):557-572. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Z, McClure ST, Appel LJ. Dietary cholesterol intake and sources among US adults. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):E771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrad Z, Johnson LK, Roemmich JN, Juan W, Jahns L. Time trends and patterns of reported egg consumption in the US by sociodemographic characteristics. Nutrients. 2017;9(4):E333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, et al. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation. 2009;119(8):1093-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, et al. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(7):713-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAS Institute The PHREG procedure: type 3 tests and joint tests. http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/67523/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_phreg_details32.htm. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 33.R Package “riskRegression” (Version 2019.01.29): risk regression models and prediction scores for survivalanalysis with competing risks. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/riskRegression/riskRegression.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 34.R Package “survival” (Version 2.43-3): Survival analysis. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/survival.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 35.R Package “pec” (Version 2018.07.26): prediction error curves for risk prediction models in survival analysis. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pec/pec.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 36.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang DD, Leung CW, Li Y, et al. Trends in dietary quality among adults in the United States, 1999 through 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1587-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women. JAMA. 1999;281(15):1387-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke R, Frost C, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies. BMJ. 1997;314(7074):112-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010. BMJ. 2014;348:g2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Djoussé L, Khawaja OA, Gaziano JM. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):474-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Description of Diet Data Harmonization Methodology

Harmonization eTable 1. Characteristics of Dietary Intake Assessment in 6 LRPP Cohorts

Harmonization eTable 2. Correlation Coefficients of Selected Nutrients From the Published Validation Studies

Harmonization eTable 3. Food Grouping Rationale in the LRPP

Harmonization eTable 4. Key Nutrients in the LRPP

Harmonization eTable 5. One Serving Size Reference and Conversion Table

Harmonization eTable 6. An Example for Conversion Between Reported Consumption Frequencies and Daily Amount for Data Analysis

Harmonization eReferences. References for Harmonization Methodology Description

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Study Participants According to Different Levels of Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day)

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Study Participants According to Different Levels of Egg Consumption (number/day)

eTable 3. Unadjusted Incidence Rate of Events Overall and by Subtype

eTable 4. Energy-Adjusted Pearson Correlation Between Dietary Cholsterol or Egg Consuption With Other Dietary Factors

eTable 5. Associations Between Dietary Cholesterol Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Various Increment Units for Dietary Cholesterol Consumption

eTable 6. Associations Between Egg Consumption and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Various Increment Units for Egg Consumption

eTable 7. Key Characteristics Between the Included and Excluded Participants

eTable 8. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, With Missing Data Imputed by Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations

eTable 9. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, After Excluding Specific Cohort(s)

eTable 10. Associations Between Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day) and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Convenient Cutoffs

eTable 11. Associations Between Quintiles of Dietary Cholesterol Consumption (mg/day) and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortalitya

eTable 12. Associations Between Number of Eggs Consumed Per Day and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality, Based on Convenient Cutoffs

eTable 13. Associations Between Quintiles of Egg Consumption Per Day and Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortalitya

eTable 14. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol (300 mg/day) or Egg (half/day) Consumption With Incident CVD and All-Cause Mortality Using Subdistribution Hazard Models

eFigure 1. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Coronary Heart Disease

eFigure 2. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Stroke

eFigure 3. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Heart Failure

eFigure 4. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Cardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 5. Association Between Each Additional 300 mg of Dietary Cholesterol Consumed Per Day and Noncardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 6. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Coronary Heart Disease

eFigure 7. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Stroke

eFigure 8. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Heart Failure

eFigure 9. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Cardiovascular Mortality

eFigure 10. Association Between Each Additional Half an Egg Consumed Per Day and Noncardiovascular Mortality