Abstract

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is common in children. Symptoms include fever, lethargy, anorexia, and vomiting. UTI is caused by Escherichia coli in over 80% of cases and treatment is a course of antibiotics. Due to acute illness caused by UTI and the risk of pyelonephritis‐induced permanent kidney damage, many children are given long‐term (several months to 2 years) antibiotics aimed at preventing recurrence. This is the third update of a review first published in 2001 and updated in 2006, and 2011.

Objectives

To assess whether long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis was more effective than placebo/no treatment in preventing recurrence of UTI in children, and if so which antibiotic in clinical use was the most effective. We also assessed the harms of long‐term antibiotic treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 30 July 2018 through contact with the Cochrane Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised comparisons of antibiotics with other antibiotics, placebo or no treatment to prevent recurrent UTI in children.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed and extracted information for the initial and previous updates. A random‐effects model was used to estimate risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) for recurrent UTI with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

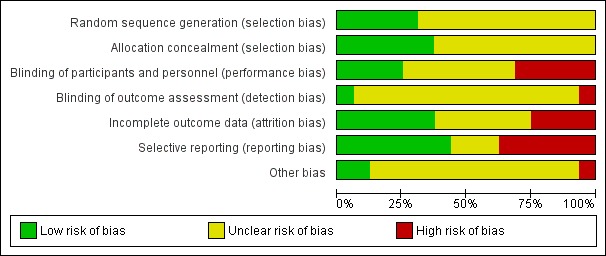

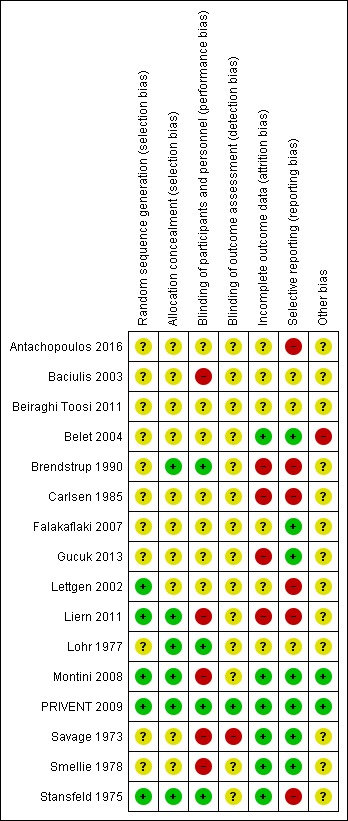

In this update sixteen studies (2036 children randomised, 1977 analysed) were included. Seven studies (612 children) compared two or more types of antibiotics, six (1088 children) compared antibiotics with placebo or no treatment, one four‐armed study compared circumcision with and without antibiotic treatment, one study compared dose of antibiotic, and one three‐armed study compared two different antibiotics as well as no treatment. Of the sixteen included studies only one study was judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains, with the majority judged to be at unclear risk of bias due to very poorly reported methodology. The number of studies judged to be a low risk of bias was: selection bias (7); performance bias (4); detection bias (1); attrition bias (6); reporting bias (7); and other bias (2). The number of studies judged to be at high risk of bias was: selection bias (0); performance bias (5); detection bias (1); attrition bias (4); reporting bias (6); and other bias (1).

Compared to placebo/no treatment, antibiotics lead to a modest decrease in the number of repeat symptomatic UTI in children; however the estimate from combining all studies was not certain and the confidence interval indicates low precision indicating that antibiotics may make little or no difference to risk of repeat infection (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.98). When we combined only the data from studies with concealed treatment allocation, there was a similar reduction in risk of repeat symptomatic UTI in children taking antibiotics (RR 0.68) and we have greater certainty in this estimate because of the more robust study designs, the confidence interval is smaller and it does not include the point of no effect (95% CI 0.48 to 0.95). The estimated reduction in risk of repeat symptomatic UTI for children taking antibiotics was similar in children with vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.07) compared to those without VUR (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.12) however there was considerable uncertainty due to imprecision from fewer events in the smaller group of children with VUR. There was no consistency in occurrence of adverse events, with one study having more events in the placebo group and a second study having more events in the antibiotics group. Three studies reported data for antibiotic resistance with the analysis estimating the risk of a UTI caused by a bacteria resistant to the prophylactic antibiotic being almost 2.5 times greater in children on antibiotics than for children on placebo or no treatment (RR 2.40, 95% CI 0.62 to 9.26). However the confidence interval is wide, showing imprecision and there may be little or no difference between the two groups.

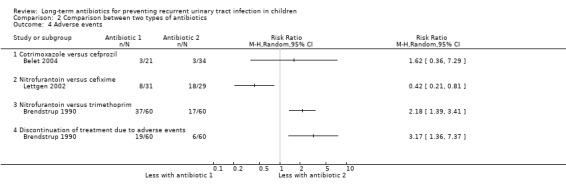

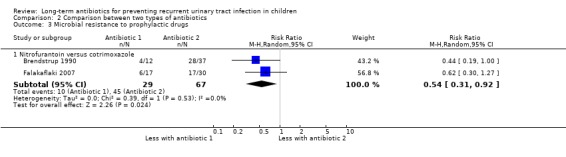

Eight studies involving 659 children compared one antibiotic with another but few studies compared the same combination for the same outcome so little data could be pooled. Two studies reported microbial resistance data and analysis showed that treatment with nitrofurantoin may lead to a lower risk of a UTI caused by a bacteria resistant to the treatment drug compared to children given trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole as their prophylactic treatment (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.92).

Authors' conclusions

Long‐term antibiotics may reduce the risk of repeat symptomatic UTI in children who have had one or more previous UTIs but the benefit may be small and must be considered together with the increased risk of microbial resistance.

Plain language summary

Long‐term antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children

What is the issue?

Bladder and kidney infections (urinary tract infection ‐ UTI) are common in children, especially girls. They cause an uncomfortable illness that can include vomiting, fever and tiredness. In some children kidney damage may occur, as can repeat illnesses. With repeated infections the risk of kidney damage increases. Some doctors prescribe long‐term antibiotics to try to prevent infections recurring, but this may cause the child to be unwell in other ways, e.g. vomiting

What did we do?

We searched electronic databases and reference lists to identify and summarise findings from all randomised controlled trials that compared low dose antibiotics given for at least 2 months, with no treatment or a placebo in children at risk of a UTI. We also identified studies comparing different types and doses of antibiotics.

What did we find?

We included 16 studies (2036 children randomised, 1977 analysed). This review found that long‐term antibiotics may reduce the risk of repeat symptomatic infections but the benefit is probably small and must be weighed against the likelihood that future infections are likely to be caused by bacteria that are resistant to the antibiotic given.

Conclusions

Long‐term, low dose antibiotics to prevent repeat UTI should be reserved for those children at high risk of repeat infection, such as young infants, and children clinicians would strongly want to reduce the risk of further infections, such as children with renal abnormalities.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Acute urinary tract infection (UTI) is common in children. By the age of seven years, 8.4% of girls and 1.7% of boys will have suffered at least one episode (Hellstrom 1991). Death is now a rare complication but hospitalisation is frequently required (40%), particularly in infancy (Craig 1998). Transient damage to the kidneys occurs in about 40% of children (Craig 1998), and permanent damage occurs in about 5% (Coulthard 1997), sometimes even following a single infection. Symptoms are systemic rather than localised in early childhood and consist of fever, lethargy, anorexia, and vomiting. UTI is caused by Escherichia coli in over 80% of cases (Rushton 1997) and treatment consists of a course of antibiotics.

Children who have had one infection are at risk of further infections. Recurrent UTI occurs in up to 30% (Winberg 1975). The risk factors for recurrent infection are vesicoureteric reflux (VUR), bladder instability and previous infections (Hellerstein 1982; Rushton 1997). Recurrence of UTI occurs more commonly in girls than boys (Bergstrom 1972; Winberg 1975).

Due to the unpleasant acute illness caused by UTI and the risk of pyelonephritis‐induced permanent kidney damage, many children are given long‐term antibiotics aimed at preventing recurrence. Cotrimoxazole, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim are commonly used for this purpose. These medications may cause side effects and promote the development of resistant bacteria.

Description of the intervention

Various low dose antibiotics have been used as prophylactic treatment in children, common options include; trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazole (2mg/kg/day /10 mg/kg/d) and nitrofurantoin (1 to 2 mg/kg/d). Other less frequently used antibiotics include cefadroxil (12.5 to 15 mg/kg/d), nalidixic acid (30 mg/kg/d), pivmecillinam (100 to 200 mg/d), cefixime (2 mg/kg), and co‐amoxiclav (15 mg/kg/d) and probably others. Durations of treatment range from one month to several years.

How the intervention might work

Theoretically, maintaining a small amount of antibiotic in the body could prevent bacteria growing out of control and causing illness.

Why it is important to do this review

Low dose antibiotic prophylaxis has been used to prevent recurring UTIs in children for many years. Anecdotal evidence and a cohort study (Craig 1998) has suggested some children on prophylactic antibiotics experience recurrence despite the treatment and theoretical concerns over bacterial resistance to such long term use of antibiotics were also raised.

Objectives

To assess whether long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis was more effective than placebo/no treatment in preventing recurrence of UTI in children, and if so which antibiotic in clinical use was the most effective. We also assessed the harms of long‐term antibiotic treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (allocation based on alternation, date of birth, hospital medical record number) of antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment for the prevention of recurrent UTI.

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs that compared two or more antibiotics administered daily for a period of at least two months for the prevention of recurrent UTI were included.

Types of participants

Children less than 18 years of age who were at risk of recurrence due to prior infection were included. Studies were included if the majority of participants (> 50%) did not have a predisposing cause such as a renal tract abnormality, including VUR, or a major neurological, urological or muscular disease.

Types of interventions

Long‐term antibiotic versus placebo/no treatment, and studies that compared two or more antibiotics with each other. Long‐term prophylaxis was defined as antibiotic administered daily for a period of at least two months.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of repeat symptomatic UTIs, confirmed by bacterial growth in the urine, in combination with signs or symptoms of a urine infection while on treatment/placebo.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were total number of positive urine cultures, adverse reactions to treatment, hospitalisation with UTI and microbial resistance.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 30 July 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register of Studies contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searches of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

2018 review update

The search results were screened and studies included or excluded based on the selection criteria listed above. Data extraction and text were completed by one author. Since both authors on this review are also authors on an included study (PRIVENT 2009), risk of bias assessment was independently reviewed by Narelle Willis (Cochrane Kidney and Transplant).

Initial review (2001) and previous updates (2006, 2011)

The search strategy described above was used independently by two authors to obtain titles of abstracts relevant to the review. The titles were independently screened by two authors, who discarded studies that were irrelevant. The selection was overly inclusive to ensure no relevant studies were missed. Two authors screened the resulting list of articles independently to assess whether the studies met our inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author.

Data extraction and management

Full articles of the included studies were examined, under open conditions to extract the necessary information. Methods (participant details (numbers, age, gender), type of antibiotic, frequency and dose regimen, duration of treatment, outcomes (recurrent UTI, adverse reactions to treatment) were extracted. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review updates (2011, 2018)

For the 2018 and 2011 updates the risk of bias tables were completed. The following items were assessed by using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Initial review (2001) and 2006 update

The quality of eligible studies was assessed independently, under open conditions by two of three authors with disagreements resolved after consultation with a third author. Blinding, losses to follow‐up, heterogeneity of study group participants, standardisation of outcome assessment, and whether intention‐to‐treat analysis was conducted, were assessed (Williams 2001; Williams 2006).

Measures of treatment effect

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients experiencing a recurrence of symptomatic UTI. The results of each study were calculated as point estimates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) were used as the measures of summary treatment effects. Number needed‐to‐treat (NNT) and number needed‐to‐harm (NNH) estimates (1/RD) were calculated to compare the benefits and harmful effects of antibiotics. Analyses were conducted for studies:

Comparing antibiotics with placebo/no treatment

Comparing one type of antibiotic with another type.

Dealing with missing data

Further information was sought from authors where papers did not contain sufficient information to make an appropriate decision about inclusion.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values is as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a CI for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias was to be assessed using a funnel plot; however there were insufficient studies to carry out this assessment.

Data synthesis

Results were pooled using a random effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Univariate analyses were used to explore the antibiotic treatment effect on repeat symptomatic UTI. Subgroup analysis was used to examine how patients VUR status and study quality (risk of bias table fields) influenced the summary treatment effect.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children without VUR

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children with VUR

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children, in studies with adequate allocation concealment

Repeat positive urine culture

All adverse events

Microbial resistance to prophylactic drug.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

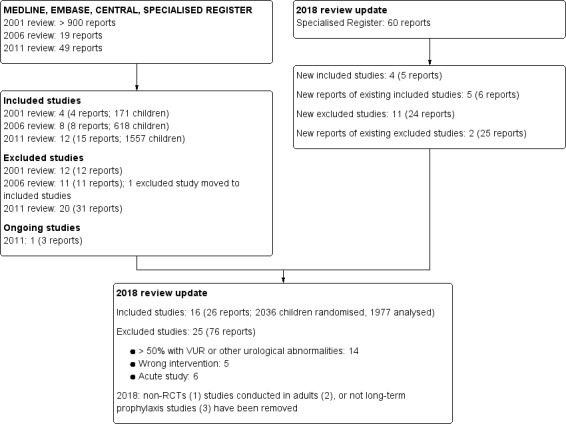

2018 review update

The search of the specialised register of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant group identified 59 reports of studies. An alert in Research Gate identified a report of an eligible study (Liern 2011) that was not identified in the Specialised Register and was not listed in MEDLINE or PubMed and was incorrectly coded in EMBASE as a journal article instead of a trial. After title and abstract review 25 reports underwent full text review (Figure 1). Four new eligible studies (5 reports) were included (Antachopoulos 2016; Beiraghi Toosi 2011; Gucuk 2013; Liern 2011), six new reports of five already included studies were identified (Baciulis 2003; Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978), and we excluded 49 reports (24 reports of 11 new studies and 25 reports of 2 already excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

2011 review update

The specialised register search identified 30 reports. After title, abstract and then full‐text review we identified five reports of four new included studies (Baciulis 2003; Belet 2004; Falakaflaki 2007; PRIVENT 2009), two reports of an existing included study (Montini 2008), three reports of one ongoing study (RIVUR 2008) and 20 reports of nine new excluded studies.

2006 review update

The search identified three new reports. We identified two new eligible studies (Lettgen 2002; and an early abstract of Montini 2008) and tow previously excluded studies were re‐assessed and included in this update (Carlsen 1985; Lohr 1977). One report was excluded.

Initial review (2001)

Of > 900 titles screened, 595 abstracts were reviewed with 578 excluded because they were clearly not RCTs of antibiotic treatment in children with UTI. Seventeen reports underwent full text review; four met our inclusion criteria (Brendstrup 1990; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978; Stansfeld 1975), one study was awaiting translation, and 12 studies were excluded.

Included studies

Sixteen studies (2036 randomised children, 1977 analysed) were identified (see Characteristics of included studies)

Thirteen studies used a parallel design while three were cross‐over studies. Thirteen studies compared two treatment groups, two studies compared three treatments and one study compared four treatment options. Seven studies (612 children) compared two or more types of antibiotics only, six studies (1088 children) compared antibiotics with placebo or not treatment, one four‐armed study (197 children) compared circumcision with and without antibiotic treatment; one study (33 children) compared dose of antibiotic (every night versus alternate night) and one three‐armed study (47 children) compared two different antibiotics as well as no treatment.

Duration of antibiotic prophylaxis varied from 10 weeks to 12 months. Thirteen studies reported the number of children with VUR (a total of 637) and 15 studies reported numbers of girls and boys (1246 girls and 669 boys). Seven studies recruited children who had experienced one or more UTIs, three studies recruited after the child's first UTI and one study included girls without a UTI but with bacteriuria. In five studies UTI history at enrolment was not reported.

Excluded studies

Fourteen studies enrolled > 50% of children with VUR (Espino Hernandez 2012; Feldman 1975; Habeeb Abid 2015; Hari 2015; Lee 2007a; Mohseni 2013; Pennesi 2008; Ray 1970; RIVUR 2008; Roussey‐Kesler 2008; Sanchez‐Bayle 1983; Swedish Reflux 2010; Zegers 2011) or other urological abnormality (Madsen 1973). Five studies didn't compare antibiotics with placebo/no treatment or with another antibiotic (Bose 1974; Clemente 1994; Craig 2002; Marild 2009; Montini 2007) and six studies were of short duration or acute treatment (Bergstrom 1968; Fennell 1980; Fischbach 1989; Garin 2006; Lindberg 1978; Pisani 1982).

Non‐randomised studies were removed from the 2018 review update.

Risk of bias in included studies

Prior to the 2011 update, analysed studies were poorly reported for methodological detail. Montini 2008 was published initially in abstract form and in the 2011 update a full journal article of the study was included with much greater methodological detail (Montini 2008). One large, recent study (PRIVENT 2009) was well designed, well reported and powered appropriately for the study question (Figure 2; Figure 3). Three of the four studies added in the 2018 update (Antachopoulos 2016; Beiraghi Toosi 2011; Gucuk 2013) were very poorly reported with all having the majority of risk of bias fields designated as unclear because details were missing from the report. Liern 2011 was reported more completely however blinding, incomplete outcomes reporting and selective reporting fields were designated as having a high risk of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Five studies (Lettgen 2002; Liern 2011; Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Stansfeld 1975) reported how the randomisation sequence was generated and appeared robust. The remaining 11 studies did not provide sufficient details about the process to understand the methods used.

Allocation concealment

Six studies (Brendstrup 1990; Liern 2011; Lohr 1977; Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Stansfeld 1975) reported that allocation to treatment group was concealed and unable to be influenced by the treating physician. For the remaining 10 studies this was unclear.

Blinding

Four studies stated that they were double‐blinded or that patients and clinicians were blinded to treatment allocation (Brendstrup 1990; Lohr 1977; PRIVENT 2009; Stansfeld 1975). Five studies stated that there was no blinding (Baciulis 2003; Liern 2011; Montini 2008; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978) and for seven studies (Antachopoulos 2016; Beiraghi Toosi 2011; Belet 2004; Carlsen 1985; Falakaflaki 2007; Gucuk 2013; Lettgen 2002) blinding of patients and clinicians was unclear. Only PRIVENT 2009 stated that outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation. Savage 1973 stated no blinding for outcomes and for the remaining 14 studies this detail was not reported.

Incomplete outcome data

Six studies provided explanations for changes in numbers of children reported at the start and finish of the studies (Belet 2004; Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978; Stansfeld 1975). For four studies (Brendstrup 1990; Carlsen 1985; Gucuk 2013; Liern 2011) numbers reported were inconsistent for the start and finish of the study or varied across the reported outcomes without explanation, placing the study at high risk of bias. For six studies it was unclear whether everyone who started the study was included in the final analysis giving them an assessment of unclear bias.

Selective reporting

Eight studies reported the most appropriate primary outcome, repeat symptomatic UTI for the question (Antachopoulos 2016; Belet 2004; Falakaflaki 2007; Gucuk 2013, Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978), while five studies reported a less relevant primary outcome of repeat positive urine culture. In three studies it was not clear whether the reported outcome was symptomatic or asymptomatic UTI, hence these were classified as unclear for selective reporting bias (Baciulis 2003; Beiraghi Toosi 2011; Lohr 1977).

Other potential sources of bias

For many studies it was difficult to determine who the children were and how many were reviewed for possible inclusion in the study and therefore the ability to determine the extent of selection bias was very limited. Only PRIVENT 2009 clearly reported the number of patients screened and the reasons for exclusion and non‐enrolment.

Definitions and criteria for diagnosis of initial and recurrent UTI differed enormously between the studies and were generally poorly reported. Misclassification was possible in most studies and largely ignored.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antibiotic treatment versus placebo or no treatment.

| Antibiotic treatment versus placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: children with previous UTI and most do not have a renal tract abnormality such as VUR Setting: children in the community presenting to a hospital who have experienced at least one UTI Intervention: antibiotic treatment Comparison: placebo/no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo/no treatment | Risk with antibiotic treatment | |||||

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children | 212 per 1,000 | 159 per 1,000 (59 to 420) | RR 0.75 (0.28 to 1.98) | 1074 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 3 | All studies comparing antibiotic treatment with placebo or no treatment. |

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children without VUR | 223 per 1,000 | 134 per 1,000 (29 to 611) | RR 0.60 (0.13 to 2.74) | 541 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ‐ |

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children with VUR | 180 per 1,000 | 117 per 1,000 (70 to 192) | RR 0.65 (0.39 to 1.07) | 371 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | Small sample size because only two studies reported separated data and majority of children did not have VUR |

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI in children, in studies with adequate allocation concealment | 161 per 1,000 | 110 per 1,000 (77 to 153) | RR 0.68 (0.48 to 0.95) | 914 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝4 MODERATE | ‐ |

| Repeat positive urine culture | 386 per 1,000 | 120 per 1,000 (31 to 455) | RR 0.31 (0.08 to 1.18) | 467 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5 | ‐ |

| All adverse events | 24 per 1,000 | 56 per 1,000 (1 to 1,000) | RR 2.31 (0.03 to 170.67) | 914 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 6 | ‐ |

| Microbial resistance to prophylactic drug | 164 per 1,000 | 394 per 1,000 (102 to 1,000) | RR 2.40 (0.62 to 9.26) | 118 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 7 | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; UTI: urinary tract infection; VUR: vesicoureteric reflux | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Two studies were consistent with each other but three others were quite variable in their findings

2 Several studies were small and results variable, making the confidence intervals wide

3 Smaller and older studies were quite variable in their findings, did not use blinding and patient selection was unclear

4One study was open label suggesting interpretation bias

5 Studies which did not include symptoms in the diagnosis of UTI are likely to involve misclassification of UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria

6 One study was open label and all adverse events were in the active arm, suggesting interpretation bias

7 One study conducted screening cultures and therefore examined more samples that may have been from asymptomatic bacteriuria while also demonstrating the presence of a drug resistant organism

Summary of findings 2. Antibiotic 1 versus antibiotic 2 for preventing repeat UTI in children.

| Antibiotic 1 versus antibiotic 2 for preventing repeat UTI in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: children with primarily normal renal tracts who have experienced at least one UTI Setting: children who have experienced a UTI in the community and are considered for preventative treatment to reduce the risk of further UTIs Intervention: one type of antibiotic Comparison: second type of antibiotic | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with antibiotic 2 | Risk with antibiotic 1 | |||||

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: nitrofurantoin (1) versus cotrimoxazole (2) | 218 per 1,000 | 124 per 1,000 (76 to 201) | RR 0.57 (0.35 to 0.92) (favours nitrofurantoin) | 157 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | No events were recorded in one study, so a single study provided data on this comparison |

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: cotrimoxazole (1) versus cefadroxil (2) | 80 per 1,000 | 143 per 1,000 (26 to 776) | RR 1.79 (0.33 to 9.70) (favours cefadroxil) | 46 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Single study, few methodology details, not a highly relevant comparison |

| Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: cotrimoxazole (1) versus cefprozil (2) | 206 per 1,000 | 142 per 1,000 (41 to 492) | RR 0.69 (0.20 to 2.39) (favours cotrimoxazole) | 55 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Single study, few methodological details, not a very relevant comparison |

| Microbial resistance to prophylactic drugs: nitrofurantoin (1) versus cotrimoxazole (2) | 672 per 1,000 | 363 per 1,000 (208 to 618) | RR 0.54 (0.31 to 0.92) (favours nitrofurantoin) | 96 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Both studies had limited methodology reported, but were consistent in their findings |

| Adverse events: cotrimoxazole (1) versus cefprozil (2) | 88 per 1,000 | 143 per 1,000 (32 to 643) | RR 1.62 (0.36 to 7.29) | 55 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Single study, few methodology details, not a highly relevant comparison |

| Adverse events: nitrofurantoin (1) versus trimethoprim (2) | 283 per 1,000 | 618 per 1,000 (394 to 966) | RR 2.18 (1.39 to 3.41) (favours trimethoprim) | 120 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Single study, poorly reported |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; UTI: urinary tract infection | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Both studies reported their methodology very poorly and it was difficult to be certain of design issues

2 Single study, no missing data but considerable uncertainty and imprecision

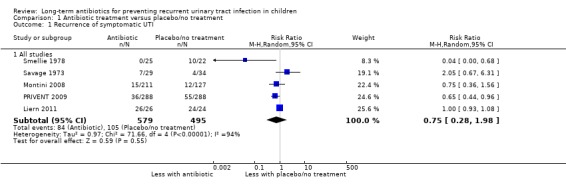

Antibiotics versus placebo/no treatment

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI

Of the seven studies comparing antibiotic treatment with placebo/no treatment, five studies, involving 1074 children contained data for the outcome repeat symptomatic UTI and could be pooled and analysed. The resulting estimated risk of repeat symptomatic UTI suggests a 25% reduction in risk of repeat symptomatic UTI for children taking antibiotics (RR 0.75, Analysis 1.1). However the precision of the estimate was low (95% CI 0.28 to 1.98) and includes no difference in risk between the treatment groups. Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 94%) and this reflects the variability in the early studies and leads to the level of certainty around this evidence as being low (Table 1). Notable in this analysis was the difference in quality of included studies. A single study (PRIVENT 2009) used a placebo and blinding and had a low risk of bias across all other fields while the remaining four studies were unblinded, did not use a placebo and were unclear or had design issues putting them at a high risk of bias. Smellie 1978 and PRIVENT 2009 compared trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole with no treatment/placebo while the three other studies compared two or three different antibiotics with no treatment.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI.

One study comparing antibiotics with no treatment was a cross‐over design (Lohr 1977) and did not provide data on the first phase, thus could not be included in the meta‐analyses. Another study (Stansfeld 1975) could not be included in the pooled analysis because they did not report the outcome of repeat symptomatic UTI.

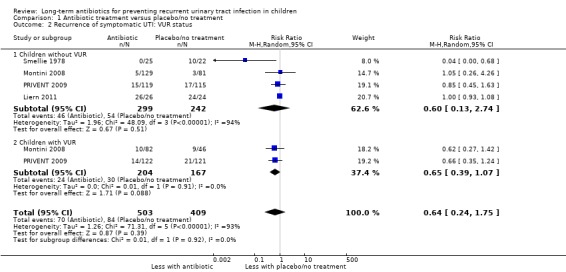

Presence of VUR and recurrence of symptomatic UTI

Four studies reported separate data for children with and without VUR (Liern 2011; Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Smellie 1978). The summary point estimate for children without VUR was RR 0.60 (Analysis 1.2.1: 95% CI 0.13 to 2.174; RD ‐7%, 95% CI ‐19 to 4) suggesting a reduced risk of repeat symptomatic UTI in those on antibiotic prophylaxis compared to those on placebo/no treatment but with considerable imprecision and leading to a low level of certainty (Table 1). The two recent and the most robustly designed studies (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009) reported findings for a subset of children who had VUR with the estimate being RR 0.65 and was more precise, leading to an assessment of high certainty around this evidence (Table 1) (Analysis 1.2.2: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.07; RD 6%, 95% CI ‐14 to ‐1). Despite the study design quality differences, the estimates for risk in children with VUR and those without VUR were remarkably similar (RR 0.60 and RR 0.65) showing little difference between antibiotic and placebo/no treatment in the different groups of children.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: VUR status.

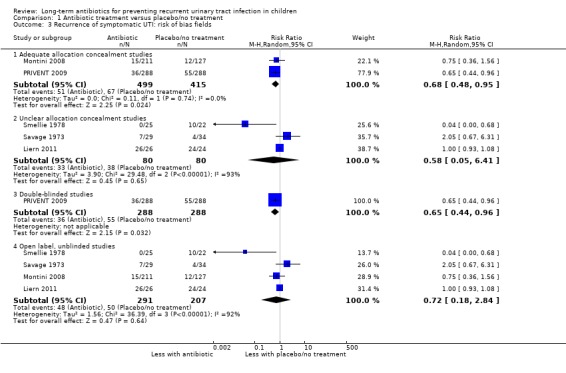

Study design and risk of bias

Two studies had adequate allocation concealment (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009) and gave a point estimate with high precision and a high level of certainty (Analysis 1.3.1: RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.95; RD ‐5%, 95% CI ‐9 to 0) (Table 1) while the three studies with unclear allocation concealment (Savage 1973; Smellie 1978, Liern 2011) showed considerable imprecision (Analysis 1.3.2: RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.05 to 6.41; RD ‐10%, 95% CI ‐40 to 19).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: risk of bias fields.

A single study was appropriately blinded (PRIVENT 2009) and the point estimate is more precise than that of the three unblinded studies (Analysis 1.3.3: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.96; RD ‐7%, 95% CI ‐13 to ‐1 compared to Analysis 1.3.4: RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.84; RD ‐7%, 95% CI ‐20 to 7).

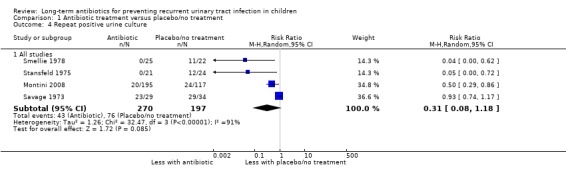

Repeat positive urine culture

Compared to placebo/no treatment, antibiotics appeared to moderately reduce the risk of repeat positive urine culture (Analysis 1.4.1: RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.18; RD ‐28% 95% CI ‐51 to ‐5) (Montini 2008; Savage 1973; Smellie 1978; Stansfeld 1975) however the precision is poor and shows there may be little or no difference in risk between those taking antibiotics and those not treated. Studies showed substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 91%) and there was considerable variability in the rates of repeat positive urine cultures in the control groups of the four studies, ranging from 21% to 85%. This suggests a very low level of certainty in this evidence (Table 1).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4 Repeat positive urine culture.

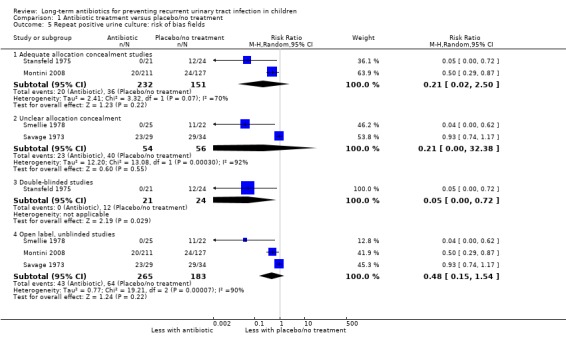

Studies with adequate allocation concealment showed a reduced risk of repeat positive culture (RR of 0.21, 95% CI 0.2 to 2.5; RD ‐29%, 95% CI ‐68 to 11) (Analysis 1.5.1) but precision was poor and includes the estimate of no difference between the groups. Studies with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment had the same RR (0.21) but much larger 95% CI, indicating much greater imprecision (95% CI 0.00 to 32.38; RD ‐28%, 95% CI ‐71 to 15) (Analysis 1.5.2). One study stated that it was blinded and their results gave a substantially reduced risk of repeat positive culture in the antibiotic group (RR of 0.05, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.72; RD ‐50%, 95% CI ‐71 to ‐29) (Analysis 1.5.3) while studies that described an open study or unclear blinding, gave a somewhat reduced risk of repeat positive culture (RR of 0.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.54; RD ‐21%, 95% CI ‐44 to 3) (Analysis 1.5.4) but this estimate includes a risk of no difference.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5 Repeat positive urine culture: risk of bias fields.

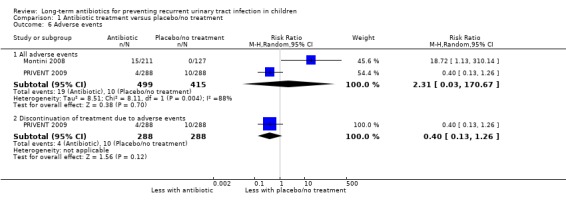

Adverse events

Two studies reported adverse events within each treatment arm (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009), with very different findings. The unblinded study (Montini 2008) showed no events in the no‐treatment arm and PRIVENT 2009 showed more events in the placebo arm than the active arm. The risk of adverse events was estimated as twice as likely in children taking placebo or not treated compared to those on antibiotics (RR 2.31) but imprecision was very high and our certainty around this evidence is low (95% CI 0.03 to 170.67; RD 2%, 95% CI 7 to 11) (Analysis 1.6.1) (Table 1).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 6 Adverse events.

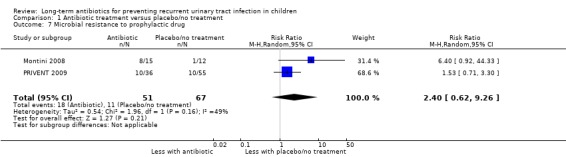

Microbial resistance

Three studies reported results for microbial resistance (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009; Stansfeld 1975). Two of these reported for repeat symptomatic UTI (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009) and showed a much increased risk of bacterial resistance to the active treatment in children taking antibiotics (RR of 2.40, 95% CI 0.62 to 9.26; RD 25%, 95% CI ‐9 to 60) (Analysis 1.7) meaning resistance was more than twice as likely in the active treatment arms than the non‐treatment or placebo groups. The third study with the outcome repeat positive urine culture, showed a single positive culture with resistant bacteria in the placebo group (Stansfeld 1975). Overall this evidence provides a moderate level of certainty (Table 1).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 7 Microbial resistance to prophylactic drug.

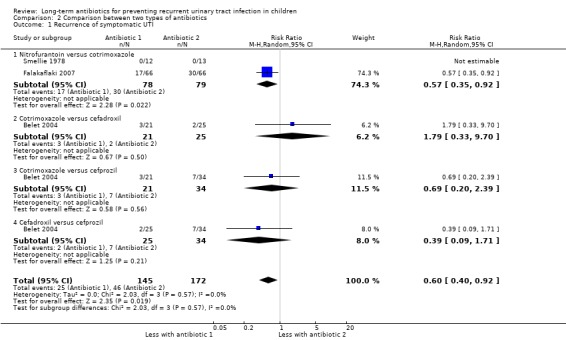

Comparison between two antibiotics

Five studies provided data to compare one antibiotic with another antibiotic (Beiraghi Toosi 2011; Belet 2004; Brendstrup 1990; Falakaflaki 2007; Lettgen 2002), two studies reported their primary outcome as symptomatic UTI and three reported positive urine culture. Almost no data could be combined since studies with the same outcome used different antibiotic comparisons.

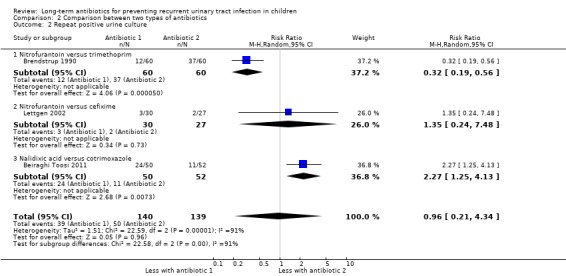

Nitrofurantoin versus other antibiotics

For the outcome symptomatic UTI, Falakaflaki 2007 showed a reduced risk of repeat symptomatic UTI in children taking nitrofurantoin compared to those taking trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole (Analysis 2.1.1: RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.92; RD ‐20%, 95% CI ‐36 to 4) with no estimate for Smellie 1978 due to absence of events in both arms. This data provides a moderate level of certainty (Table 2). Brendstrup 1990 compared nitrofurantoin with trimethoprim and showed a reduced risk of repeat positive urine culture in children taking nitrofurantoin compared to those on trimethoprim (Analysis 2.2.1: RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56; RD ‐42%, 95% CI ‐58 to ‐26). However, patients receiving nitrofurantoin were twice as likely to experience side effects (nausea, vomiting or stomach ache) than patients receiving trimethoprim (Analysis 2.4.3: RR 2.18, 95% CI 1.39 to 3.41; RD 33%, 95% CI 17 to 50). This suggests that the side effects of nitrofurantoin (NNH = 3, 95% CI 2 to 6) are similar to the prophylactic benefit (NNT = 5, 95% CI 3 to 33) compared with trimethoprim. Lettgen 2002 compared nitrofurantoin with cefixime. For the outcome repeat positive urine culture the risk estimate suggested nitrofurantoin gave a slightly increased risk of repeat positive culture compared to cefixime (Analysis 2.2.2: RR 1.35) however the precision of the estimate was very poor and includes the possibility of no difference between the treatment options (95% CI 0.24 to 7.48; RD 3%, 95% CI ‐12 to 17).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between two types of antibiotics, Outcome 1 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between two types of antibiotics, Outcome 2 Repeat positive urine culture.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between two types of antibiotics, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

Carlsen 1985, a cross‐over study, compared nitrofurantoin with pivmecillinam in 32 children. Allocation concealment and blinding were unclear. Ten repeat positive urine cultures occurred during pivmecillinam treatment and six while taking nitrofurantoin.

Other antibiotic comparisons

Belet 2004 compared three antibiotics (cotrimoxazole, cefadroxil and cefprozil) with cefadroxil appearing the most effective (Analysis 2.1.3; Analysis 2.1.4; Analysis 2.1.5). No results showed a difference and the study was underpowered (N = 21, 25 and 34) for the small differences in event rates (8%, 14% and 21%). Beiraghi Toosi 2011 compared nalidixic acid with trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole for the outcome repeat positive urine culture with recurrence twice as likely in children taking nalidixic acid (RR 2.27 95%CI 1.25 to 4.13).

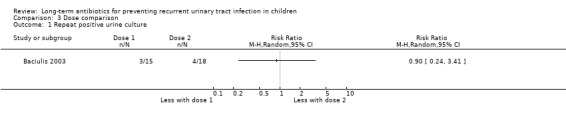

Dose comparisons

Baciulis 2003 compared every night cefadroxil treatment with alternate evening therapy. No difference between the doses was evident (Analysis 3.1: RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.24 to 3.41; RD ‐2%, 95% CI ‐30 to 26). The study was small (N = 33) and methodology was poorly reported.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dose comparison, Outcome 1 Repeat positive urine culture.

Circumcision

Gucuk 2013 randomised boys with VUR and boys without VUR into different treatment options and therefore the findings across the VUR group and non‐VUR group could not be compared. Boys with VUR were randomised to antibiotics plus circumcision or antibiotics alone, while boys without VUR were randomised to circumcision alone or no treatment. None of the 45 boys with VUR who were circumcised and treated with antibiotics for 12 months experienced a repeat symptomatic UTI while 6/46 treated with antibiotics for 12 months experienced a repeat symptomatic UTI. In the boys without VUR, none of the 47 circumcised boys and none of the 49 not treated boys experienced a repeat symptomatic UTI during 12 months of follow‐up.

Cross‐over studies, excluded from meta‐analyses

In none of the cross‐over studies was it possible to determine what outcomes occurred before the cross‐over, so none were included in any meta‐analyses.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Long‐term, low dose antibiotics were associated with a modest decrease in the number of repeat symptomatic UTI in children; however the estimate from combining all studies was not precise or certain (Table 1).

Low dose antibiotics taken for 12 months reduced the risk of repeat symptomatic UTI in children by around 6%, which means a baseline risk of recurrence of 20% is reduced to 14%. This treatment was also associated with a more than doubling of the risk that a repeat infection was caused by a bacteria resistant to the treatment antibiotic.

Nitrofurantoin appeared to be the most effective antibiotic treatment for UTI prevention; however it was associated with more adverse events than trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The two largest studies in this review reported data and study design details with a high degree of completeness. These studies also included a range of children who are likely to represent the population of children in whom this treatment may be considered. Early studies were far more selective in the type of children included and reported design detail much less thoroughly than later studies.

Two earlier versions of this review (Williams 2001; Williams 2006) concluded that the evidence to support the use of antibiotics to prevent recurrent symptomatic UTI was weak. The update in 2011 (Williams 2011) added data from two large and well reported studies that changed this conclusion (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009). PRIVENT 2009 was optimally designed with all features of good design reported in the article (randomisation process, allocation concealment, blinding, explanations for incomplete data, appropriate outcome reporting, and consideration for other bias). Montini 2008, while somewhat smaller, unblinded and with no placebo treatment, gave a RR (0.75) that was reasonably consistent with results from the PRIVENT 2009 (RR 0.65); only the PRIVENT 2009 reached a degree of precision and certainty for a benefit to antibiotic treatment. These estimates are the least biased and therefore likely to reflect the true effect of prophylactic antibiotic treatment. In the 2018 update four additional studies were included but each provided very limited data for analyses resulting in no change to previous findings.

The estimated absolute risk reduction was 6% and corresponds to the need to treat between 16 and 17 children for 12 months to prevent one symptomatic UTI. The absolute treatment effect appears consistent in children with and without VUR, a known risk factor for further UTI. Although antibiotic prophylaxis prevents UTI overall, the data suggest that prolonged treatment results in changes in the susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria with an increased risk of symptomatic UTI caused by bacteria resistant to the prophylactic agent.

The smaller and older studies gave highly variable and inconsistent findings, highlighting the effect of poor design and chance effects on study findings. Earlier studies tended to report repeat positive urine culture as their primary outcome and large reductions in the risk of repeat positive urine cultures were found in the antibiotic groups of these studies. However, the appropriateness of this as an outcome is questionable given that few doctors would treat asymptomatic bacteriuria. Further limitations to these studies are the quality of their design. Only two or four studies used adequate allocation concealment and one of four reported double blinding. Our analyses show that the poorly designed studies inflate the treatment effect by 49%, and ranging from 100% to 400% (using Analysis 1.3.2) compared to those with better design.

Only PRIVENT 2009 reported sufficient detail to identify the time frame for recurrence of symptomatic UTI, in this study 36% of UTIs in the active arm and 47% in the placebo arm occurred within three months of randomisation. A further 19% and 29% (active and placebo arms respectively) of repeat symptomatic UTIs occurred between three and six months post randomisation. This infers that the risk of repeat symptomatic infection is highest during the three months following initial infection and may suggest an initial course of treatment of three months with possible extension to six months.

The side effects of active treatment compared to placebo or no treatment were reported in two studies (Montini 2008; PRIVENT 2009). The unblinded study (Montini 2008) reported 15 events in the active treatment arm and none in the no‐treatment group, while the blinded study (PRIVENT 2009) showed considerably more events in the placebo arm compared to active treatment (10 versus 4). This suggests interpretation of adverse events is influenced by knowledge of treatment group therefore the blinded study is a more reliable estimate of rates of adverse events.

Three studies reported the numbers of urine cultures causing symptomatic UTI that grew bacteria resistant to the active treatment in the studies with placebo comparisons. Two studies reported that 8% of the cultures in the no treatment arm were resistant to the active drug but PRIVENT 2009 showed that 18% of urine infections were caused by bacteria resistant to the active treatment. This suggests the baseline risk of resistance in the non‐treated group is not zero and is likely to be closer to 18% given the greater reliability of PRIVENT 2009. PRIVENT 2009 and Montini 2008 reported bacterial resistance in the active treatment arms, with over half (53%) of UTIs in the active arm in Montini 2008 and 28% of UTIs in the active arm of PRIVENT 2009 being attributed to bacteria resistant to the active treatment drug. While the RR is imprecise (2.4), as shown by the large 95% CI (0.62 to 9.26), the risk appears increased.

Although nitrofurantoin was more effective than trimethoprim or cotrimoxazole in preventing repeat symptomatic infection or repeat positive urine culture, it was associated with a greater number of side effects. The harmful effects of nitrofurantoin outweigh the prophylactic benefit and suggest that nitrofurantoin may not be an acceptable therapy. Patient compliance would be an important factor to consider in deciding on the use of nitrofurantoin as prophylaxis.

The combined analysis of the studies included in this review show there is a small benefit in long‐term antibiotic treatment to prevent repeat symptomatic UTI however this should be weighed up against the likely increased risk of bacterial resistance in subsequent infections, the baseline risk of repeat symptomatic infection and how strongly parents and physicians wish to avoid a possible repeat illness.

Quality of the evidence

Montini 2008 design was less rigorous than PRIVENT 2009 in that there was no placebo treatment, no blinding, and the antibiotic treatment could be either of two antibiotics. Awareness of treatment or the absence of treatment may have led to biased interpretation of possible symptoms of a UTI and misclassification of asymptomatic bacteriuria as symptomatic UTI. Different treatment options in the active arm may have led to heterogeneity in findings within that group if the two antibiotics differed in efficacy.

Early studies had many design limitations and reported highly variable results.

Potential biases in the review process

The two authors of the 2011 and 2018 updates are authors on the PRIVENT 2009 which may have led to a more favourable assessment PRIVENT 2009. To address this an independent person reviewed the risk of bias data to identify and correct possible biases.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several other reviews on this topic have been published (Dai 2010; Le Saux 2000; Mathew 2010; Mori 2009) with varying conclusions depending on which studies were included in the analysis. None of these reviews identified additional studies to those considered in this review and were often missing the complete group. Most authors included studies in which the majority of children had VUR making their inclusion criteria different to ours and more similar to the Cochrane review of Interventions for VUR (Nagler 2011). On the whole these reviews agreed with the current assessments of study quality.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Prior to Montini 2008 and PRIVENT 2009, the evidence to support long‐term, low dose antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent UTI in children without VUR consisted of a small number of poor quality studies that gave inconsistent and imprecise results. The addition of data from two much larger and better designed studies changes this. Analysis of the larger, better designed studies demonstrates, with considerable consistency, a small benefit of low dose antibiotics to prevent repeat symptomatic UTI in children. The data show few adverse effects from the antibiotic treatment but demonstrate an increased risk of bacterial resistance to the treatment drug in subsequent infections. A single study reported event time periods and showed that the greatest risk of repeat symptomatic infection occurs in the three to six months following initial UTI. Nitrofurantoin appeared the most effective treatment but led to considerable adverse events.

Implications for research.

These findings suggest a small benefit to treating children who have had at least one UTI but for many children in the studies, no further UTIs occurred. Future research could focus on exploring and identifying which children are most likely to benefit from treatment.

Feedback

Long‐term antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children, 18 June 2019

Summary

I was surprised to see that this review had this statement in the implications for practice "The analysis now demonstrates, with considerable consistency, a small benefit of low dose antibiotics to prevent repeat symptomatic UTI in children." When in analysis 1.1 there is a clear non significant result, with a large amount of heterogeneity. I do not believe that this is a case of low sample numbers causing true significance to be obscured as one old study at high risk of bias was one of the only significant studies. In fact if this study is removed in a sensitivity analysis the RR almost reverts to 1. Given the problem of increased risk of microbial resistance also highlighted by the current authors I think it is unwise to say any more than with current evidence we are unsure of the true effect.

Lastly given the three reasons footnoted in the summary of findings table for outcome 1.1 I struggle to see how this was graded as low quality of evidence rather than very low.

Kind regards, Vanessa Jordan

Reply

1. We have clarified our text to state; “Analysis of the larger, better designed studies” instead of “The analysis now”……. demonstrates with considerable conistsency.. This text relates to the analysis in 1.3.1 which gave a risk ratio of 0.68(95%CI 0.48 to 0.95) I2=0%

2. It is somewhat subjective in deciding whether results from a group of studies is low quality or very low quality, we selected low based on the quality of the individual studies in combination with 4 of 5 studies having the same direction of effect and somewhat overlapping confidence intervals.

Contributors

Gabrielle Williams

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 September 2019 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback comment and amendment incorporated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1998 Review first published: Issue 4, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 April 2019 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Small studies added, no change to conclusions |

| 30 July 2018 | New search has been performed | Four new studies added |

| 9 March 2011 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Four new studies added |

| 9 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 22 May 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Anna Lee who contributed to the original iteration and first update of this review (Williams 2001; Williams 2006), contributing to the design, quality assessment, data collection, entry, analysis and interpretation, and writing.

We are grateful to Lei Wei who contributed to the first review update (Williams 2006), contributing to the quality assessment, data collection, entry, analysis and interpretation, and writing.

The authors acknowledge Dr Smellie for her content expertise.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL | #1 Urinary Tract Infections explode all trees in MeSH #2 Schistosomiasis haematobia, this term only in MeSH #3 (#1 AND NOT #2) #4 (urin* next tract next infect*) or (urin* next infect*) in All Fields #5 uti #6 bacteriuria #7 pyuria #8 Urine explode all trees in MeSH #9 (#8 AND bacter*) #10 urin* near bacter* in All Fields #11 (#9 OR #10) #12 (#3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #11) #13 Child explode all trees in MeSH #14 child* #15 girl* #16 boy* #17 Pediatrics explode all trees in MeSH #18 pediatric* #19 paediatric* #20 (#13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19) #21 Antibiotic Prophylaxis explode all trees in MeSH #22 antibio* near prophyla* #23 Anti‐Bacterial Agents explode all trees in MeSH #24 Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary explode all trees in MeSH #25 "long term" and (antibiot* or prophylax*) #26 (#21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25) #27 (#12 AND #20 AND #26) #28 Recurrence explode all trees in MeSH #29 recurren* #30 prevent* #31 (#28 OR #29 OR #30) #32 (#12 AND #20 AND #31) #33 (#32 OR #27) |

| MEDLINE | 1. urinary tract infections/ or bacteriuria/ or pyuria/ 2. UTI.tw. 3. urinary tract infection$.tw. 4. bacteriuria.tw. 5. pyuria.tw. 6. bacterial infection$.tw. 7. or/1‐6 8. exp child/ 9. child$.tw. 10. girl$.tw. 11. boy$.tw. 12. exp pediatrics/ 13. pediatric$.tw. 14. paediatric$.tw. 15. or/8‐14 16. and/7,15 17. Antibiotic Prophylaxis/ 18. (antibiotic$ adj5 prophyla$).tw. 19. exp ANTIBIOTICS/ 20. exp Bacterial Infections/ 21. anti‐infective agents,urinary/ 22. (long term adj25 antibiotic$).tw. 23. (long term adj25 prophyla$).tw. 24. recurrence/ 25. recurren$.tw. 26. prevent$.tw. 27. or/17‐26 28. and/16,27 |

| EMBASE | 1. exp Urinary Tract Infection/ 2. asymptomatic bacteriuria/ or bacteriuria/ 3. Pyuria/ 4. UTI.tw. 5. urinary tract infection$.tw. 6. bacteriuria.tw. 7. pyuria.tw. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp child/ 10. exp Pediatrics/ 11. child$.tw. 12. girl$.tw. 13. boy$.tw. 14. or/9‐13 15. and/8,14 16. exp antibiotic prophylaxis/ 17. exp antibiotics/ 18. exp urinary tract antiinfective agent/ 19. urinary tract antiinfective agent$.tw. 20. (long term adj10 antibiotic$).tw. 21. (long term adj25 prophylaxis).tw. 22. (antibiotic adj10 prophylaxis).tw. 23. prophylaxis.tw. 24. recurrent disease/ 25. recurren$.tw. 26. prevent$.tw. 27. or/16‐26 28. and/15,27 |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub‐scales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antibiotic treatment versus placebo/no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 All studies | 5 | 1074 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.28, 1.98] |

| 2 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: VUR status | 4 | 912 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.24, 1.75] |

| 2.1 Children without VUR | 4 | 541 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.13, 2.74] |

| 2.2 Children with VUR | 2 | 371 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.39, 1.07] |

| 3 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI: risk of bias fields | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Adequate allocation concealment studies | 2 | 914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.48, 0.95] |

| 3.2 Unclear allocation concealment studies | 3 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.05, 6.41] |

| 3.3 Double‐blinded studies | 1 | 576 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.44, 0.96] |

| 3.4 Open label, unblinded studies | 4 | 498 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.18, 2.84] |

| 4 Repeat positive urine culture | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 All studies | 4 | 467 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.08, 1.18] |

| 5 Repeat positive urine culture: risk of bias fields | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Adequate allocation concealment studies | 2 | 383 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.02, 2.50] |

| 5.2 Unclear allocation concealment | 2 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.00, 32.38] |

| 5.3 Double‐blinded studies | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.05 [0.00, 0.72] |

| 5.4 Open label, unblinded studies | 3 | 448 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.15, 1.54] |

| 6 Adverse events | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 All adverse events | 2 | 914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.31 [0.03, 170.67] |

| 6.2 Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events | 1 | 576 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.13, 1.26] |

| 7 Microbial resistance to prophylactic drug | 2 | 118 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.40 [0.62, 9.26] |

Comparison 2. Comparison between two types of antibiotics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of symptomatic UTI | 3 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.40, 0.92] |

| 1.1 Nitrofurantoin versus cotrimoxazole | 2 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.35, 0.92] |

| 1.2 Cotrimoxazole versus cefadroxil | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.79 [0.33, 9.70] |

| 1.3 Cotrimoxazole versus cefprozil | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.20, 2.39] |

| 1.4 Cefadroxil versus cefprozil | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.09, 1.71] |

| 2 Repeat positive urine culture | 3 | 279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.21, 4.34] |

| 2.1 Nitrofurantoin versus trimethoprim | 1 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.19, 0.56] |

| 2.2 Nitrofurantoin versus cefixime | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.24, 7.48] |

| 2.3 Nalidixic acid versus cotrimoxazole | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.27 [1.25, 4.13] |

| 3 Microbial resistance to prophylactic drugs | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Nitrofurantoin versus cotrimoxazole | 2 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.31, 0.92] |

| 4 Adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Cotrimoxazole versus cefprozil | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Nitrofurantoin versus cefixime | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Nitrofurantoin versus trimethoprim | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between two types of antibiotics, Outcome 3 Microbial resistance to prophylactic drugs.

Comparison 3. Dose comparison.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Repeat positive urine culture | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Antachopoulos 2016.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | States "randomized at a ratio of 1:1”, method of randomisation not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unable to determine numbers because reported as courses of antibiotics, not children |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Appropriate outcomes but unable to use data as results reported as courses of antibiotics, not children |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Many details missing and few descriptives of included children |

Baciulis 2003.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised, method of randomisation was not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The paper does not clearly state whether more children were enrolled than are reported, so it is unclear whether there is any missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement; funding source not reported |

Beiraghi Toosi 2011.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised, method of randomisation was not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement; funding source not reported |

Belet 2004.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Treatment group 3

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details of how sequence was generated, states randomised by drawing lots |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data evident, no losses during follow‐up reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Primary outcome is appropriate |

| Other bias | High risk | Age of TMP/SMX group was significantly higher than the other two groups |

Brendstrup 1990.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Does not state how sequence was generated Quote: "randomised by the local hospital" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation by external group |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two antibiotics were delivered in indistinguishable mixtures, suggests blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |