Abstract

Etanercept is a soluble form of the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) that inhibits pathological tumor necrosis factor (TNF) responses in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. However, besides TNF, etanercept also blocks lymphotoxin-α (LTα), which has no clear therapeutic value and might aggravate some of the adverse effects associated with etanercept. Poxviruses encode soluble TNFR2 homologs, termed viral TNF decoy receptors (vTNFRs), that display unique specificity properties. For instance, cytokine response modifier D (CrmD) inhibits mouse and human TNF and mouse LTα, but it is inactive against human LTα. Here, we analyzed the molecular basis of these immunomodulatory activities in the ectromelia virus–encoded CrmD. We found that the overall molecular mechanism to bind TNF and LTα from mouse and human origin is fairly conserved in CrmD and dominated by a groove under its 50s loop. However, other ligand-specific binding determinants optimize CrmD for the inhibition of mouse ligands, especially mouse TNF. Moreover, we show that the inability of CrmD to inhibit human LTα is caused by a Glu-Phe-Glu motif in its 90s loop. Importantly, transfer of this motif to etanercept diminished its anti-LTα activity in >60-fold while weakening its TNF-inhibitory capacity in 3-fold. This new etanercept variant could potentially be used in the clinic as a safer alternative to conventional etanercept. This work is the most detailed study of the vTNFR–ligand interactions to date and illustrates that a better knowledge of vTNFRs can provide valuable information to improve current anti-TNF therapies.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor (TNF), receptor, viral immunology, inflammation, autoimmune disease, decoy receptor

Introduction

The tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF)4 comprises 19 cytokines and 29 cellular receptors involved in essential biological processes such as cell death, immunity, and organ development (1). However, a deregulated production of these cytokines can provoke autoimmunity and inflammatory disorders. For instance, Crohn's disease, psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease are often associated with the uncontrolled activity of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF), the archetypical cytokine of the family (2). To date, there are five TNF inhibitors approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of these diseases: four monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab) and a soluble decoy receptor, etanercept (3). Etanercept is a fusion protein of the ligand-binding domain of the cellular TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2) with the Fc portion of a human IgG1 (4). Importantly, despite its proven efficiency in ameliorating patient symptomatology, etanercept can also cause major adverse effects, including increased susceptibility to infections, lymphoma, and heart failure (5). These side effects might be explained, at least in part, by the fact that etanercept blocks not only TNF but also other TNFSF ligands essential for homeostasis and immunity like lymphotoxin α (LTα) (6). Redesign of this molecule appears to be desirable for its safer application in the clinic.

Poxviruses have evolved a similar strategy to inhibit TNFSF ligands in their hosts. Members of the Orthopoxvirus genus encode up to four different soluble viral TNF decoy receptors (vTNFRs), termed cytokine response modifier B (CrmB), CrmC, CrmD, and CrmE, that display differential ligand and species specificity profiles (7). For instance, CrmC and CrmE are specific mouse TNF (mTNF) and human TNF (hTNF) inhibitors, respectively, whereas CrmB and CrmD inhibit TNF, LTα, and LTβ (8–12). Furthermore, although CrmD, the only active vTNFR encoded by the mouse-specific ectromelia virus (ECTV), is the vTNFR with the highest binding affinity for mouse LTα (mLTα), it fails to neutralize human LTα (hLTα) (12). In fact, CrmB, encoded by the human variola virus, is the only vTNFR that blocks hLTα (12). Thus, it appears that vTNFRs have evolved to fulfill the particular immunomodulatory needs of poxviruses according to their host species. This level of specialization to discriminate between mouse and human cytokine counterparts or between the highly related TNF and LTα is rare among cellular TNFSF receptors (TNFRs) (13). Therefore, understanding the molecular determinants of the vTNFR–ligand interactions could reveal new molecular strategies to improve the TNF specificity of etanercept and increase its clinical safety.

To date, the uncomplexed form of CrmE is the only vTNFR whose structure has been solved (14). This structure confirmed that vTNFRs mimic the three-dimensional folding of the ligand-binding moiety of cellular TNFRs, which is formed by a variable number of cysteine-rich domain (CRD) pseudorepeats. The folding of a typical CRD is maintained by three disulfide bonds established by six highly conserved cysteines (15). Cellular TNFRs may comprise up to five CRDs (16). 15 of the 29 different TNFRs contain at least three CRDs. In most of these, CRD2 and CRD3 constitute the principal ligand-binding sites (17). In particular, two loops located in these two CRDs and designated the 50s and the 90s loop, respectively, are known to act as the dominant ligand-binding determinants in several receptor–ligand complexes (18–20). In contrast, the CRD1, although usually not directly involved in ligand binding, can mediate the self-association of some cellular TNFRs in a ligand-independent manner, which has been proposed to enhance the ligand-binding affinity and the signaling potency of the receptor (21–23). For this reason, the CRD1 was termed preligand assembly domain (PLAD).

However, little is known about how vTNFRs interact with their ligands. T2, a CrmB homolog encoded by the Leporipoxvirus myxoma virus (MYXV), is the only vTNFR whose ligand-binding site has been characterized to some extent. Analysis of T2 truncated mutants showed that, like in many cellular TNFRs, the CRD2 and CRD3 were essential for TNF binding (24). However, the precise molecular bases of the vTNFR–ligand interactions remain mostly unexplored. Interestingly, a PLAD-like function has been attributed to the CRD1 of MYXV T2. It was shown that T2 can interfere with TNF signaling in a ligand-independent manner by interacting with the CRD1 of TNFR1 or TNFR2 to generate unresponsive heterotrimers (25). Conversely, the structure of CrmE did not confirm the existence of a PLAD in other vTNFRs (14), and whether the CRD1 can induce self-oligomerization in vTNFRs is not completely understood. Furthermore, even the number of CRDs that constitute the TNF-binding domain of vTNFRs remains controversial, and precise allocation of the TNF-binding moiety in these viral decoy receptors is still missing. This is especially important in the case of CrmB and CrmD, whose TNF-binding domain precedes an extended C-terminal domain absent from CrmC and CrmE and named smallpox-encoded chemokine receptor (SECRET) domain that binds and inhibits a limited number of chemokines (26). We have recently demonstrated that CrmD is an essential virulence factor for ECTV, which causes mousepox, a smallpox-like disease in mouse. In addition, we showed that both CrmD activities, anti-TNF and anti-chemokine, are required for a successful evasion of the host immune response by ECTV (27).

Here, we precisely define the TNF-binding moiety of CrmD, discuss the existence of a PLAD in this vTNFR, and provide new insights into the molecular bases of its interaction with TNF and LTα of mouse and human origin. Importantly, we applied the information extracted from our CrmD analysis to severely curb the anti-LTα activity of etanercept without dismantling its TNF-inhibitory properties. This study offers molecular data that might help to understand the role of each CrmD-inhibitory activity in ECTV pathogenesis and provides proof of principle that structural characterization of vTNFRs may be of great value to improve current anti-TNF therapies.

Results

Fine mapping of the TNF- and chemokine-binding domains of CrmD

The TNF-binding domain of CrmD is proposed to be formed by four CRDs (10); however, the amino acids that mark the end of the TNF-binding moiety and the beginning of the antichemokine SECRET domain have never been experimentally identified. Therefore, we first wanted to precisely delimit the amino acid sequence that constitutes the TNF-binding domain of CrmD.

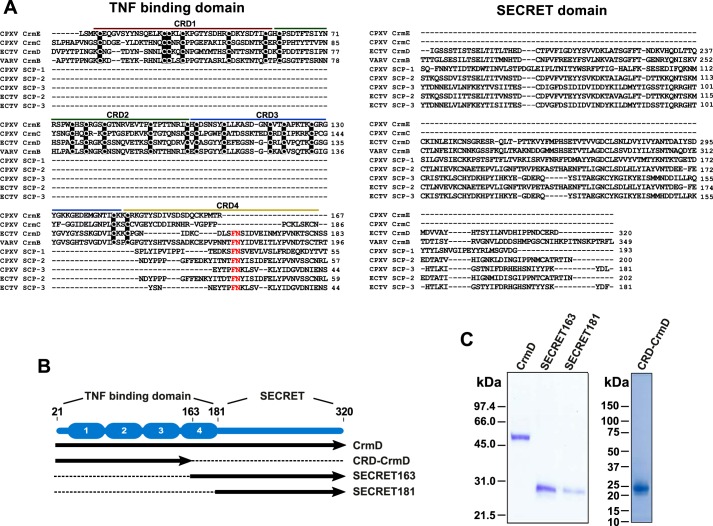

We addressed this question indirectly by identifying the beginning of the SECRET domain. Three chemokine-binding proteins with sequence and functional similarities to the SECRET domain have been characterized in poxviruses, named SECRET-containing protein 1 (SCP1), SCP2, and SCP3 (26). As shown in Fig. 1A, the amino acid sequences of these SCPs align with that of the SECRET domain of CrmB and CrmD, a domain missing from CrmC and CrmE. Interestingly, an FN motif (Phe163 and Asn164) conserved at the N terminus of all SCPs is also present in the putative CRD4 of CrmD and CrmB but absent in CrmC and CrmE (Fig. 1A). This observation suggested that Phe163 and Asn164 of CrmD could actually be important for chemokine binding. To evaluate this, we compared the chemokine-binding affinities of two CrmD truncated mutants for two different forms of the SECRET domain: SECRET163 (Phe163–Asp320), containing the Phe163 and Asn164 conserved in the SCPs, and SECRET181 (Ser181–Asp320), which includes the C-terminal sequence immediately after the putative CRD4 of CrmD (Fig. 1B). These two SECRET domain forms were expressed and purified by recombinant baculoviruses alongside the full-length CrmD and CRD-CrmD (Asp21–Ser162), a truncated CrmD mutant containing the sequence immediately N-terminal to the sequence of the SECRET163 protein (Fig. 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

Expression of full-length and truncated CrmD recombinant proteins. A, Clustal Omega alignment of the amino acid sequences of the vTNFRs CPXV CrmE (gene K3R, strain elephantpox, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q9DJL2), CPXV CrmC (gene CPXV191, strain Brighton Red, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q9YP87), ECTV CrmD (gene E6, strain Hampstead, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number O57300), and VARV CrmB (gene G2R, strain Bangladesh 1975, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number P34015) and the SCPs CPXV SCP-1 (gene CPXV218, strain Brighton Red, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q8QMN0), CPXV SCP-2 (gene CPXV014, strain Brighton Red, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q8QN47), CPXV SCP-3 (gene CPXV201, strain Brighton Red, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q8QMP4), ECTV SCP-2 (gene EVN012, strain Naval, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number A0A075IJA5), and ECTV SCP-3 (gene EVN184, strain Naval, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number A0A075ILK3). The signal peptides were removed before the alignment. Numbers at the end of each line indicate the amino acid position relative to the complete protein sequence. The sequences were split into two columns corresponding to the CrmD TNF-binding and SECRET domains as labeled above each column. The sequences of each CRD in the TNF-binding domain of vTNFRs are indicated with differently colored lines. Conserved cysteines residues are shown in black background. An FN motif conserved in the SCPs and in the CRD4 of VARV CrmB and ECTV CrmD is highlighted in red. B, schematic representation of the CrmD truncated proteins expressed by recombinant baculoviruses. The CrmD protein molecule is depicted in blue. The two domains of CrmD, “TNF-binding domain” and “SECRET,” are labeled above. Ellipses numbered from 1 to 4 represent the different CRDs in the TNF-binding domain. Below the blue diagram, the sequences included in the different CrmD truncated proteins (SECRET163, SECRET181, and CRD-CrmD) as well as in the full-length CrmD are represented as solid black arrows. Dashed lines represent the portion of CrmD excluded in each truncated protein. Amino acid positions pertinent for these four recombinant proteins are numbered above the CrmD blue diagram. C, Coomassie Blue–stained gels showing the analysis of 1 μl of the final concentrated protein stocks (indicated above each gel line) by SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass is indicated in kDa.

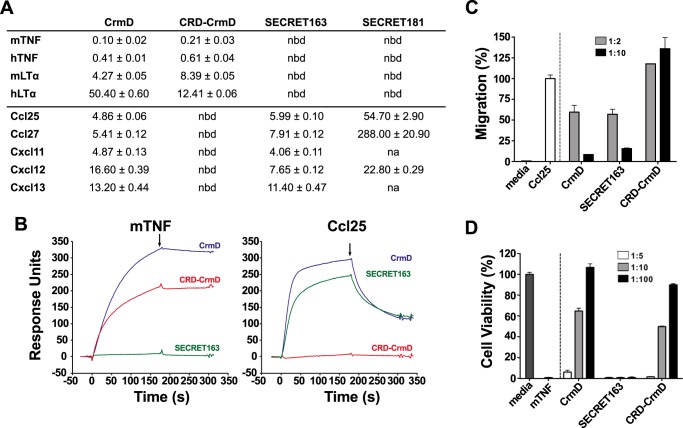

Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), we calculated the binding affinity constant (KD) of these four recombinant proteins for the TNFSF ligands mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα and the mouse chemokines Ccl25, Ccl27, Cxcl11, Cxcl12β, and Cxcl13 (Fig. 2A). As expected, CRD-CrmD and the SECRET domain proteins interacted exclusively with TNFSF ligands or chemokines, respectively (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, whereas full-length CrmD bound both mTNF and Ccl25, CRD-CrmD and SECRET163 interacted only with mTNF or Ccl25, respectively. Importantly, SECRET163, but not SECRET181, fully conserved the chemokine-binding affinities of the full-length protein (Fig. 2A). For instance, although CrmD bound Ccl25 and Ccl27 with a KD of 4.86 and 5.41 nm, the binding affinities of SECRET181 for these chemokines were 54.70 and 288.0 nm, a 1-log and about 2-log KD increase, respectively (Fig. 2A). By contrast, SECRET163 maintained the binding affinities of CrmD for these two chemokines (KD, 5.99 and 7.91 nm, respectively; Fig. 2A). Complementarily, the binding affinities of CRD-CrmD (KD, 0.21–12.41 nm) for TNFSF ligands were similar to those of the full-length CrmD (KD, 0.10–50.40 nm) in all cases (Fig. 2A). These results indicated that the sequence from the putative CRD4 included in SECRET163 is dispensable for the binding of TNFSF ligands but required for high-affinity chemokine interactions.

Figure 2.

SECRET163, but not SECRET181, displays chemokine-binding and -inhibitory activities comparable with those of full-length CrmD. A, TNFSF ligand- and chemokine-binding affinity constants (KD) of the CrmD truncated mutants calculated by SPR. The table shows the mean ± S.D. KD in nm units. nbd, no binding detected; na, not assayed. B, SPR sensorgrams showing the binding of 100 nm mTNF or mouse Ccl25 to CM4 chips immobilized with CrmD (blue), CRD-CrmD (red), or SECRET163 (green). Black arrows indicate the end of the analyte injection. C, MOLT-4 cell chemotaxis assay. MOLT-4 transwell migration was induced by 70 nm mouse Ccl25 preincubated in the absence (Ccl25) or presence of recombinant protein at the indicated chemokine:protein molar ratios (see legend) of CrmD, SECRET163, or CRD-CrmD. Migrated cells were detected using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit and measuring the A490 in a microplate reader. Media indicates the cell migration detected in the absence of chemokines. Data are represented as the percentage of migration relative to the A490 detected when the cells were incubated with the chemokine alone (Ccl25). D, mTNF-induced cytotoxicity assay on L929 cells. L929 cells were incubated with 1.2 nm mTNF in the absence or presence of recombinant protein at increasing mTNF:protein molar ratios (see legend). Cell viability was assessed as the A490 determined using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit. The A490 calculated for cells incubated with mTNF alone (mTNF) was subtracted from all samples. Data are represented as the percentage relative to the A490 recorded for cells incubated without mTNF (media). In C and D, results are shown as mean ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicates of one experiment representative of three independent experiments.

We then analyzed whether CRD-CrmD and SECRET163 also conserved the capacity of the full-length protein to inhibit the bioactivity of TNF and chemokines, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2C, SECRET163 inhibited the Ccl25-induced chemotaxis of MOLT-4 cells to the same extent that CrmD did, reducing cell migration nearly 50% when incubated with the chemokine at a 2 m excess and almost neutralizing chemotaxis at a 10 m excess (Fig. 2C). As expected, CRD-CrmD did not inhibit the cell migration induced by Ccl25 (Fig. 2C). In contrast, CRD-CrmD, but not SECRET163, protected L929 cells from the cytotoxic effect of mTNF. A 10 m excess of both CrmD and CRD-CrmD protected at least 50% of the cells against mTNF (Fig. 2D). These results confirmed our conclusions based on the binding assays and indicated that the second half of the putative CRD4 is not involved in TNF binding but it is most likely part of the SECRET domain.

Expression and purification of CrmD mutants

To study the molecular bases of the CrmD interaction with TNFSF ligands, we performed alanine site-directed mutagenesis of its TNF-binding domain, which we had just delimited to the sequence Asp21–Ser162. We generated 14 different full-length CrmD mutants affecting residues throughout this sequence, including some related to three structural features known to be important for ligand binding in most TNFRs: the PLAD and the 50s and 90s loops.

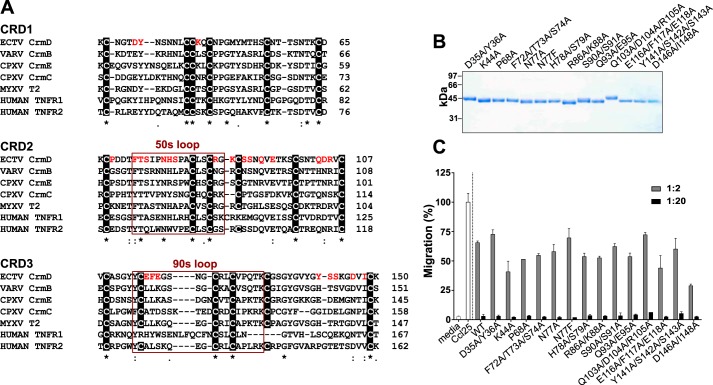

The CRD1 or PLAD mediates the oligomerization of TNFRs prior to the interaction with the ligand (21). A similar activity was reported for the CRD1 of MYXV T2 (25), suggesting that the PLAD could be an activity extendable to the CRD1 of vTNFRs. However, beyond the six canonical Cys residues, there is no discernible conserved PLAD sequence across the CRD1 of vTNFRs and TNFRs (Fig. 3A). TNFR1 K19A/Y20A and K32A mutants are known to lose the self-association and ligand-binding abilities of the wildtype (WT) receptor (28). These residues are somewhat conserved in CrmD (Fig. 3A). Therefore, to evaluate whether they play a similar role in vTNFRs, we generated the CrmD mutants D35A/Y36A and K44A (Fig. 3A). Using size exclusion chromatography and native gel electrophoresis, we found that the oligomeric state of the protein was unaltered in the CrmD D35A/Y36A mutant (Fig. S1), which argued against a central role of these residues in the potential oligomerization of CrmD.

Figure 3.

CrmD site-directed mutagenesis. A, Clustal Omega alignment of the amino acid sequences of the first three CRDs of the vTNFRs CPXV CrmE (gene K3R, strain elephantpox, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q9DJL2), CPXV CrmC (gene CPXV191, strain Brighton Red, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number Q9YP87), ECTV CrmD (gene E6, strain Hampstead, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number 057300), VARV CrmB (gene G2R, strain Bangladesh 1975, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number P34015), and MYXV T2 (gene m002L, strain MAV, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number E2CZP3) and the human TNFRs TNFRl (gene TNFRSFlA, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number P19438) and TNFR2 (gene TNFRSFlB, UniProt/TrEMBL accession number P20333). CrmD residues subjected to mutagenesis are highlighted in red. Sequences corresponding to the 50s and 90s loops are framed in red and labeled accordingly above the frame. Conserved cysteines are shown in a black background. Numbers at the end of each line indicate the amino acid position of the last residue in the line relative to the complete sequence of the protein. B, Coomassie Blue–stained gel showing the SDS-PAGE analysis of 1 μl of the protein stock purified for each mutant. Molecular mass is shown in kDa. C, inhibition of mouse Ccl25-induced chemotaxis of MOLT-4 cells by CrmD WT or the indicated mutants. 70 nm chemokine was preincubated in the absence or presence of recombinant protein at increasing chemokine:protein molar ratios (see legend), and its ability to induce transwell migration of MOLT-4 cells was assessed. Migrated cells were detected by measuring the A490 using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit. Data are represented as the percentage relative to the A490 detected when the cells were incubated with the chemokine alone (Cc125). Media indicates the cell migration recorded in the absence of chemokine. Results are shown as mean ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicates from one experiment representative of three independent experiments.

The 50s loop in the CRD2 and the 90s loop in the CRD3 are known to be essential ligand-binding determinants in most TNFRs (18, 20, 29–31). Initial binding models proposed that conserved hydrophobic interactions in the 50s loop, critical for the binding affinity, orient the ligand to favor polar interactions by the 90s loop, which defines the ligand specificity (18). However, a significant number of other TNFSF ligand–receptor complexes are known to diverge from this general model (19, 20, 30, 32, 33). Therefore, the precise ligand-binding determinants of TNFRs can be very variable and difficult to predict solely from structural models. In fact, even the application of receptor-based molecular replacement has proved to be problematic for the structural determination of some TNFR–ligand complexes (34). In this situation, we selected our CrmD alanine mutants (targeted residues highlighted in red in Fig. 3A) based on its alignment with other vTNFRs and its more highly related cellular counterparts, TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Fig. 3A). We mutated residues unique to CrmD as well as conserved amino acids either within the 50s and 90s loops or in other regions of the CRD2 and CRD3 (Fig. 3A). To guarantee that at least one of our mutants lost all ligand-binding capabilities, besides its corresponding alanine mutation, we generated CrmD N77F, equivalent to a reported TNFR1 N66F mutant known to be unable to interact with TNF (21).

All 14 CrmD mutants were expressed by recombinant baculoviruses and purified from supernatants of infected insect cells (Fig. 3B). To rule out the possibility that the introduced mutations drastically affected the overall CrmD three-dimensional folding, we tested the ability of the mutants to inhibit Ccl25-induced chemotaxis. As shown in Fig. 3C, the chemokine-inhibitory activity of the WT protein was preserved in all mutants.

Conserved and ligand-specific molecular bases drive the interaction of CrmD with TNF and LTα of mouse and human origin

To define the implication of the mutated residues in the CrmD ligand-binding mechanism, we determined the binding affinity of all mutants for four different CrmD ligands, mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα, by SPR (Table 1). Fig. 4A shows some examples of the sensorgram fittings performed to calculate the binding affinity and kinetic constants presented in Table 1. Those cases in which no binding was detected or the binding was so weak that it did not allow a reliable determination of the affinity constants within the system detection limits are indicated as nbd for “no binding detected” (Table 1 and Fig. 4B). Fig. 4B summarizes the -fold change caused by each mutation on the corresponding ligand binding KD of the WT protein. Fig. 4C shows the position in the surface of a CrmD structural model of those residues that when mutated resulted in a significant modification of the protein KD for each ligand. CrmD N77F was not able to interact with any cytokine (Table 1 and Fig. 4B); however, only the alanine mutation of this residue was considered for the construction of Fig. 4C.

Table 1.

Kinetic affinity constants of the mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα binding by CrmD mutants

CrmD genotype variants are shown in the left column. The association constant (Ka), dissociation constant (Kd), and their respective standard errors (S.E.) for each cytokine are indicated. The binding affinity constant (KD, in bold) is shown in nm units. nbd, no binding detected.

| CrmD | mTNF |

hTNF |

mLTα |

hLTα |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ka ± S.E.a | Kd ± S.E.b | KD | Ka ± S.E. | Kd ± S.E. | KD | Ka ± S.E. | Kd ± S.E. | KD | Ka ± S.E. | Kd ± S.E. | KD | |

| WT | 3.27 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.10 | 9.64 ± 0.03 | 3.94 ± 0.09 | 0.41 | 2.31 ± 0.01 | 9.86 ± 0.11 | 4.27 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 30.10 ± 0.27 | 50.40 |

| D35A/Y36A | 3.75 ± 0.02 | 6.50 ± 0.70 | 1.73 | 20.80 ± 0.31 | 45.00 ± 2.20 | 2.16 | 2.72 ± 0.04 | 43.30 ± 1.09 | 15.90 | nbd | nbd | nbd |

| K44A | 2.81 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.10 | 8.49 ± 0.03 | 3.24 ± 0.11 | 0.40 | 1.20 ± 0.02 | 5.93 ± 0.22 | 4.95 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 30.40 ± 0.26 | 75.80 |

| P68A | 4.07 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | 0.15 | 11.10 ± 0.03 | 2.90 ± 0.08 | 0.26 | 2.66 ± 0.03 | 12.60 ± 0.34 | 4.71 | 1.22 ± 0.01 | 23.60 ± 0.24 | 19.30 |

| F72A/T73A/S74A | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd |

| N77A | 4.75 ± 0.02 | 2.59 ± 0.11 | 0.55 | 15.60 ± 0.26 | 45.90 ± 1.33 | 2.47 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 13.90 ± 0.61 | 62.00 | 5.56 ± 0.20 | 411.00 ± 8.39 | 73.90 |

| N77F | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd |

| H78A/S79A | 2.97 ± 0.03 | 2.39 ± 0.33 | 0.80 | 16.10 ± 0.06 | 8.19 ± 0.16 | 0.51 | 3.00 ± 0.04 | 6.12 ± 0.10 | 2.04 | 4.81 ± 0.07 | 55.80 ± 0.68 | 11.60 |

| R86A/K88A | 3.13 ± 0.02 | 2.30 ± 0.45 | 0.73 | 11.60 ± 0.04 | 6.28 ± 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 6.19 ± 0.21 | 7.02 | 6.09 ± 0.11 | 82.50 ± 0.82 | 13.50 |

| S90A/S91A | 2.34 ± 0.01 | 2.36 ± 0.06 | 1.00 | 15.90 ± 0.08 | 11.10 ± 0.16 | 0.70 | 1.25 ± 0.01 | 8.58 ± 0.14 | 6.99 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 20.10 ± 0.31 | 41.10 |

| Q93A/E95A | 3.19 ± 0.01 | 2.87 ± 0.11 | 0.90 | 15.40 ± 0.10 | 17.00 ± 0.22 | 1.11 | 2.84 ± 0.03 | 32.00 ± 0.64 | 11.20 | nbd | nbd | nbd |

| Q103A/D104A/R105A | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd | nbd |

| E116A/F117A/E118A | 2.29 ± 0.01 | 1.93 ± 0.64 | 0.84 | 10.70 ± 0.09 | 12.50 ± 1.35 | 1.17 | 2.38 ± 0.03 | 13.30 ± 0.22 | 5.58 | 5.08 ± 0.02 | 11.30 ± 0.09 | 2.22 |

| Y141A/S142A/S143A | 3.05 ± 0.03 | 2.62 ± 0.10 | 0.86 | 14.70 ± 0.12 | 32.70 ± 0.96 | 2.23 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 20.70 ± 0.28 | 50.60 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 50.70 ± 0.99 | 107.00 |

| D146A/I148A | 4.91 ± 0.03 | 4.35 ± 0.45 | 0.89 | 21.20 ± 0.22 | 31.00 ± 1.28 | 1.46 | 3.22 ± 0.05 | 46.00 ± 1.51 | 14.30 | 1.15 ± 0.04 | 312.00 ± 8.15 | 271.00 |

aKa ± S.E. × 105 (1/m s).

b Kd ± S.E. × 10−4 (1/s).

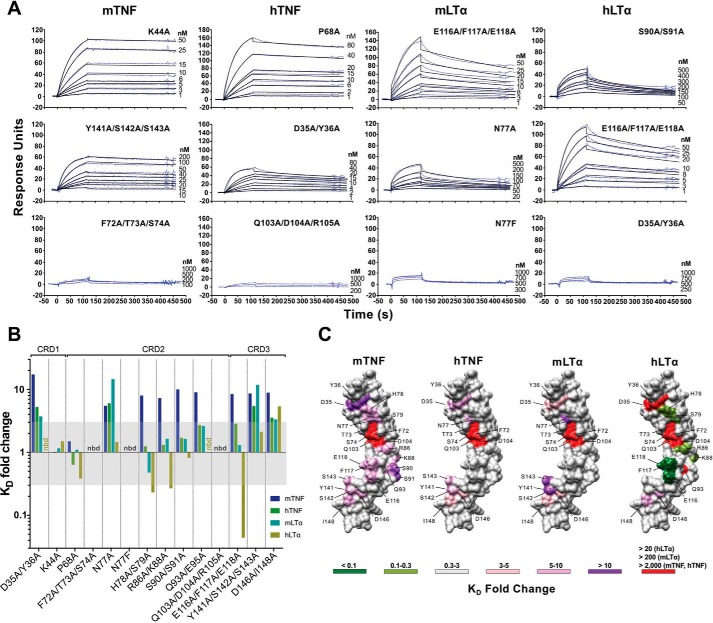

Figure 4.

Effect of the CrmD mutants on ligand-binding affinity. The binding affinity of the CrmD mutants for mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα was calculated by SPR. A, examples of the binding sensorgrams and fittings obtained for the determination of the binding kinetic constants shown in Table 1. The corresponding analyte and CrmD mutant are indicated above each graph column and at the top right corner of each graph, respectively. The top graph row includes sensorgrams for CrmD mutants whose binding affinity for the indicated cytokine was comparable with that of WT CrmD. The middle row contains sensorgrams for mutants with significantly reduced (Y141A/S142A/S143A:mTNF, D35A/Y36A:hTNF, and N77A:mLTα) or enhanced (E116A/F117A/E118A:hLTα) binding affinity, and the bottom row shows examples where no binding was detected (nbd) or it was too weak to be analyzed accurately. B, -fold change (KD(mutant)/KD(WT)) caused by each CrmD mutant on the KD of CrmD WT for mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα. The KD -fold change range that was considered nonsignificant (0.3–3) is shaded in gray. nbd, no binding detected. In C, residues whose alanine mutation resulted in a significant increase (>3-fold change) or decrease (<0.3-fold change) in the KD of CrmD WT for each ligand are located, colored, and labeled on a model of the CrmD surface (gray) generated by I-TASSER (62). The corresponding ligands are shown above the CrmD models. The legend indicates the colors assigned to the different KD -fold change ranges. The maximum detectable KD -fold increase (red) varied among the different analytes (>20 for hLTα, >200 for mLTα, and >2,000 for mTNF and hTNF).

Some similarities were found in the molecular bases that drive the interaction of CrmD with mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα. In particular, certain residues in the CRD1 (Asp35 and Tyr36), CRD2 (Phe72, Thr73, Ser74, Gln103, and Asp104), and CRD3 (Asp146 and Ile148), although to a different extent in some cases, were consistently important for the CrmD interaction with all four ligands (Fig. 4, B and C). The most evident of these common binding determinants was a groove in the CRD2 (Fig. 4C). Mutation of Phe72, Thr73, Ser74, Gln103, and Asp104, located in a CRD2 groove formed under the 50s loop, abolished all ligand-binding abilities of CrmD (Fig. 4, B and C). Similarly, mutation of two residues of the distal CRD3, Asp146 and Ile148, consistently reduced the binding affinity for all ligands (8.9-, 3.6-, 3.3-, and 5.4-fold KD increases for mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα, respectively) (Fig. 4B). In addition, mutation of three other amino acids in the C-terminal region of CRD3, Tyr141, Ser142, and Ser143, also decreased the CrmD-binding affinity for mTNF (8.6-fold), hTNF (5.4-fold), and mLTα (11.9-fold) but not for hLTα (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that this C-terminal region of the CRD3 is important for the ligand-binding properties of CrmD. Finally, we found that mutation of Asp35 and Tyr36 in the CRD1 significantly increased the KD for all ligands, with a more markedly deleterious effect on mTNF (17.3-fold KD increase) than on hTNF or mLTα binding (5.3- and 3.7-fold KD increase, respectively) (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, we did not detect hLTα binding by this D35A/Y36A mutant (Table 1 and Fig. 4, A and B); however, it is important to note that due to cytokine supply limitations, 1 μm was the highest ligand concentration included in our experiments. In these conditions, given the lower binding affinity of CrmD for hLTα (KD, 50.40 nm), 20-fold was the highest KD increase detectable for this ligand. The same applies to the mutant Q93A/E95A, which did not bind hLTα but conserved the hTNF- and mLTα-binding affinity of the WT protein and displayed a 9-fold increase in the mTNF KD (Fig. 4B).

We also identified several ligand-specific differences among our CrmD mutants. First, interestingly, the KD for mTNF was increased in many more mutants than for any other cytokine (Fig. 4B). Besides the conserved binding determinants mentioned above, mutation of amino acid residues located in the 50s loop (His78 and Ser79), the 90s loop (Glu116, Phe117, and Glu118), and the connecting region between these loops (Arg86, Lys88, Ser90, Ser91, Gln93, and Glu95) reduced the mTNF-binding affinity without significantly damaging the binding of other ligands (Fig. 4B). This suggests that CrmD might establish a closer contact to mTNF with more residues involved in the interaction. Interestingly, many of these mTNF-specific binding determinants appeared to obstruct the hLTα binding by CrmD. For instance, mutation of His78 and Ser79 or Arg86 and Lys88 increased the hLTα-binding affinity 4.3- and a 3.7-fold, respectively (Fig. 4B). More strikingly, an E116A/F117A/E118A mutant displayed a remarkable 22.7-fold surge in the hLTα-binding affinity (Fig. 4, A–C, and Table 1).

We concluded that the core of the molecular mechanism of CrmD binding to mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα is formed by essentially the same group of amino acids. However, consistent with the fact that CrmD is expressed by ECTV, a strictly mouse pathogen, additional residues appear to have specialized CrmD for the interaction with mTNF at the cost of weakening its interaction with hLTα, a biologically irrelevant cytokine for a virus that does not infect humans.

Inhibition of TNFSF cytokines by CrmD mutants

Although vTNFRs usually neutralize their ligands, there are examples of noninhibitory vTNFR–ligand high-affinity interactions. For instance, CrmE binds both mTNF and hTNF with a binding affinity below the nanomolar range but only blocks hTNF (12). This suggests that the ligand-binding and -neutralizing determinants may differ in vTNFRs. Therefore, to complete our understanding of the CrmD biochemistry, we analyzed the ability of each mutant to inhibit the cytotoxic activity of mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα on L929 cells.

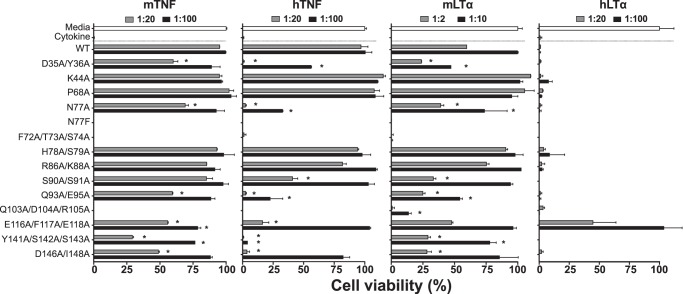

As shown in Fig. 5, in the absence of inhibitors, mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα were cytotoxic and killed the cells (Fig. 5, Cytokine). However, in the presence of recombinant protein (Fig. 5, CrmD WT or mutant), added at the indicated cytokine:protein molar ratios, different cell survival rates were recorded. As expected, those mutants with no ligand-binding capacity, the N77F control mutant and the CRD2 groove mutants F72A/T73A/S74A and Q103A/D104A/R105A, failed to protect the cells from the activity of any of the four cytokines tested (Fig. 5). Therefore, we concluded that the CRD2 groove is critical not only for the binding but also for the inhibitory properties of CrmD.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory properties of CrmD mutants. A cytotoxic dose of mTNF, hTNF, mLTα, and hLTα was incubated with L929 cells in the absence (Cytokine) or presence of CrmD WT or the indicated mutants at increasing cytokine:protein molar ratios (see legends above each graph). After 18 h, cell survival was assessed as the A490 determined using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit. Data are represented as the percentage relative to the A490 recorded for cells incubated without cytokine (Media; 100% cell viability). The corresponding effector cytokine is indicated above each graph. Results are shown as mean ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicates of three representative experiments. Asterisks indicate mutants that displayed significantly different viability values compared with CrmD WT at the same protein dose (*, p < 0.05, analysis of variance with Bonferroni multiple comparison test).

An evident ligand-specific effect was not detected among the other CrmD mutants. Mutations that impaired to some extent the capacity of CrmD to inhibit mTNF also affected to different degrees the anti-hTNF and anti-mLTα activity of the protein (Fig. 5). This suggests that CrmD deploys a similar molecular mechanism to inhibit these three cytokines. However, interestingly, the anti-hTNF effect of CrmD was more markedly susceptible to mutagenesis than its ability to block the mouse cytokines, which may suggest a more robust design to target murine ligands. For instance, low doses of CrmD WT (1:20) were sufficient to cause nearly 100% cell survival in both mTNF- and hTNF-mediated cytotoxicity assays (Fig. 5). However, at this same dose, the mutants D35A/Y36A, N77A, Q93A/E95A, and D146A/I148A were inactive against hTNF, whereas they protected at least 50% of the cells from mTNF (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the mutant Y141A/S142A/S143A showed no signs of hTNF-inhibitory capacity, whereas it protected 25 and 75% of the cells from mTNF and mLTα at the low and high protein dose, respectively. Most of these mutations that impaired the CrmD-inhibitory properties also displayed a reduced binding affinity for the corresponding cytokine. However, this was not always the case. For instance, the anti-mTNF activity of H78A/S79A, R86A/K88A, and S90A/S91A, despite their significant loss of mTNF-binding affinity (Table 1 and Fig. 4B), was indistinguishable from that of CrmD WT. Therefore, these residues contribute to the binding but are dispensable for the neutralization of mTNF by CrmD.

Consistent with the lower binding affinity of CrmD for hLTα (KD, 50.40 nm; Table 1) and as reported previously (12), CrmD failed to inhibit this cytokine. Even in the presence of a 100 m excess of CrmD WT, hLTα killed 100% of the L929 cells (Fig. 5). This hindered our ability in this assay to study the functional effects of those mutations that reduced the CrmD-binding affinity for hLTα. However, we found that the CrmD mutant E116A/F117A/E118A displayed a remarkable gain of anti-hLTα activity, reaching full cellular protection at the higher dose tested (Fig. 5). This was consistent with the high hLTα-binding affinity of this mutant (KD, 2.22 nm; Table 1). This result indicates that CrmD is perfectly equipped to inhibit hLTα, but an EFE motif in its 90s loop, although innocuous for the capacity of the protein to block mTNF, hTNF, and mLTα, keeps it inactive against hLTα.

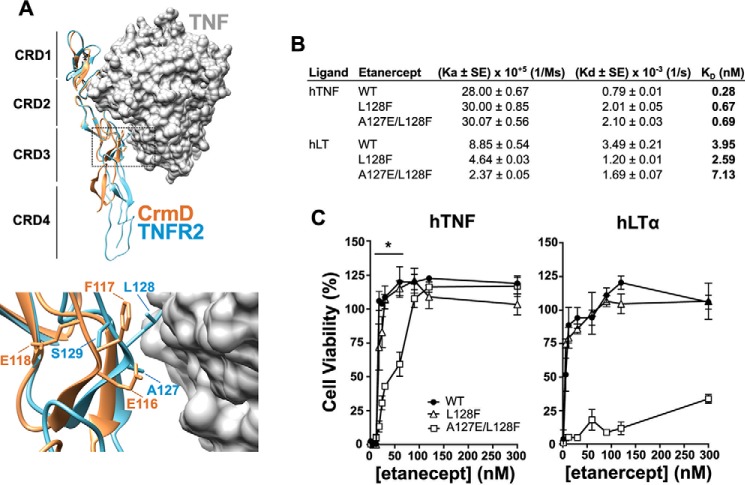

Transfer of the EFE motif of CrmD into the 90s loop of etanercept specifically impairs its anti-hLTα activity

The inflammatory diseases currently treated with etanercept are predominantly TNF-driven. Therefore, the anti-hLTα activity of etanercept not only appears to be clinically unnecessary, but it could also pose a source of unwanted complications. Having shown that a 90s loop EFE motif in CrmD specifically hinders its anti-hLTα activity, we hypothesized that, by transferring the EFE motif of CrmD into the 90s loop of etanercept, we could disrupt its anti-hLTα activity while keeping it active against hTNF.

The amino acid sequence alignment in Fig. 3A shows that the EFE motif (Glu116-Phe117-Glu118) in the CRD3 of CrmD aligns with an ALS motif (Ala127-Leu128-Ser129) in the 90s loop of human TNFR2, which corresponds to the TNF-binding moiety of etanercept. Furthermore, we observed that in the crystal structure of the TNFR2–TNF complex (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 3ALQ) the TNFR2 Ser129 was not facing the ligand (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the structural superimposition of a CrmD model with the structure of TNFR2 suggested that the third amino acid of this motif in CrmD, Glu118, would also be far from the ligand interface. Thus, to introduce the lowest number of modifications into the original sequence of etanercept, we mutated only the TNFR2 Ala127 and Leu128 to their equivalent amino acids in the 90s loop of CrmD (Glu and Phe). We generated recombinant baculoviruses for the expression of the double mutant A127E/L128F and the two single mutants A127E and L128F. Unfortunately, for unknown reasons, we were not able to successfully express the A127E protein in this system. SPR analysis revealed that the hTNF- and hLTα-binding affinities of etanercept were not significantly affected in the mutants (Fig. 6B). However, as we have discussed above, binding affinity does not always correlate with neutralizing potency. Therefore, we compared the capacity of L128F, A127E/L128F, and WT etanercept to block the cytotoxic activity of hTNF and hLTα on L929 cells. As shown in Fig. 6C, 20 nm etanercept WT was enough to fully neutralize both hTNF and hLTα (Fig. 6C), reaching 50% cell viability at 10–20 and 5 nm (EC50), respectively. The L128F mutant was functionally indistinguishable from WT etanercept (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the A127E/L128F etanercept protected 50% of the cells from hTNF at 30–60 nm and reached full protection at 90 nm (Fig. 6C). However, this double mutant showed a very low anti-hLTα activity and required a high 300 nm dose to protect only 35% of the cells from this cytokine (Fig. 6C), positioning its anti-hLTα EC50 at even higher concentrations. Therefore, although the anti-hTNF activity of etanercept was reduced by 3× in the A127E/L128F mutant, this variant was at least a 60× weaker hLTα inhibitor. These results confirmed our observations in CrmD and indicated that the 90s loop of viral and cellular TNFRs may contain important molecular determinants for the LTα species specificity.

Figure 6.

Etanercept A127E/L128F mutant displays enhanced TNF-neutralizing specificity. A, localization of the side chains of the EFE motif in the 90s loop of CrmD. CrmD three-dimensional folding was modeled using I-TASSER and aligned with the crystallographic structure of the TNFR2–TNF structure (PDB code 3ALQ) in Chimera. CrmD and TNFR2 are represented as yellow and blue ribbons, respectively. The surface of the human TNF trimer is shown in gray. Bottom panel, magnification of the 90s loop region (dashed frame) showing the side chains of the overlapping EFE and ALS motifs of CrmD and TNFR2, respectively. B, hTNF- and hLTα-binding affinity of WT, L128F, and A127E/L128F etanercept calculated by SPR. The kinetic affinity constants, association (Ka), dissociation (Kd), and binding affinity (KD), and their S.E. are shown for each interaction. C, hTNF- and hLTα-mediated cytotoxicity assays. L929 cells were incubated with 1a .2 nm concentration of the corresponding cytokine, as labeled above each graph, with increasing concentrations of WT (black circles), L128F (white triangles), or A127E/Ll28F etanercept (white squares). After 18 h, cell viability was assessed as the A490 detected using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit. Data are represented as the percentage relative to the A490 recorded for cells incubated without cytokine (100% cell viability). Means ± S.D. (error bars) of triplicates from two independent experiments are shown. The horizontal line above the hTNF graph indicates the etanercept concentrations in which statistically significant differences were detected between the anti-hTNF activity of the WT and the A127E/L128F mutant (*, p < 0.05, two-tailed t test).

Discussion

Multiple efforts have been made to characterize the immunomodulatory capacities of vTNFRs in vivo and in vitro; however, the molecular mechanisms of vTNFR–ligand interactions remain poorly analyzed. This work contributes to this gap of knowledge by delineating the molecular bases of the CrmD interaction with TNF and LTα. In addition, we present the first empirical evidence for the CrmD TNF-binding domain boundaries. More importantly, our work proves that structural analyses of vTNFRs can be of great value to improve anti-TNF therapies based on soluble decoy receptors.

There is no consensus yet about the number of CRDs that constitute the TNF-binding domain of vTNFRs. For instance, CrmC and CrmE have been indistinctly represented in the literature with either four or three CRDs (9, 11, 14, 26, 35, 36). It is assumed that CrmD and CrmB consist of an N-terminal four-CRD TNF-binding domain and a C-terminal SECRET domain (10, 26). However, we have demonstrated here that the second half of the CRD4, beginning at an FN motif conserved in all SECRET-containing proteins, although dispensable for the CrmD anti-TNF activity, is essential for the high-affinity chemokine interactions by the SECRET domain. Consistent with this, the C-terminal region of the CRD4 of CrmD and CrmB contains two amino acids, Asp167 and Glu169 (Fig. 1A), that were identified as key chemokine-binding determinants in the structure of the SECRET–CX3CL1 complex (37). Therefore, we concluded that Phe163 and the sequence at its C terminus belong to the SECRET domain. In which domain the first half of the CRD4 should be allocated remains to be elucidated. A previous analysis of T2 truncated mutants showed that the CRD4 was dispensable for the anti-TNF activity of this CrmB homolog (38). Therefore, the vestigial CRD4 of orthopoxvirus-encoded vTNFRs is unlikely to contribute to TNF binding. The function of the CRD4 in cellular TNFR1 and TNFR2 remains unclear. Its proximity to the cell membrane suggests that the CRD4 may facilitate the surface exposition of the ligand-binding domain and the transition to the intracellular signaling domain. This would explain why a complete CRD4 is unnecessary in soluble vTNFRs.

Like the CRD4, the CRD1 is rarely directly involved in ligand binding. However, it has been shown that the CRD1 or PLAD mediates the ligand-independent oligomerization of some TNFRs, including TNFR1, TNFR2, CD40, Fas, and TRAIL receptors (21, 22, 39–41). Whether the CRD1 may also induce self-assembly in vTNFRs remains unclear. It has been reported that the mutations K19A/Y20A and K32A disrupt the PLAD activity of TNFR1, resulting in mutant receptors unable to oligomerize and interact with TNF (21). In contrast, here we have shown that equivalent mutations in CrmD, D35A/Y36A and K44A, were only partially detrimental or completely innocuous, respectively, for the activity of this vTNFR. In addition, we confirmed that the protein oligomeric state was not altered in the D35A/Y36A mutant. This suggests either that a PLAD is missing from CrmD or that the molecular bases of a potential PLAD in CrmD differ from those of the TNFR1 PLAD. Of note, the CrmE crystallographic structure did not confirm the presence of a PLAD in this vTNFR (14). Interestingly, the authors showed that CrmE Tyr28, equivalent to CrmD Tyr36, established hydrophobic interactions with the 50s loop that might contribute to the correct folding of this important ligand-binding site. This is consistent with molecular dynamics analysis of TNFR1 that proposed that the CRD1 is essential to stabilize the CRD2 conformation (42), suggesting that the ligand-binding defects observed in TNFR PLAD mutants might be caused by a subtle destabilization of the CRD2. The same might explain the partial loss of activity in the CrmD D35A/Y36A mutant; however, a direct implication of these residues in ligand binding cannot be excluded, especially because equivalent amino acids were involved in the formation of the OX40–OX40L complex (32). It is important to mention that none of this invalidates the possibility that vTNFRs may interfere with cellular TNFR signaling by engaging receptor monomers through their CRD1 as demonstrated for MYXV T2 (25). It would be interesting to study whether CrmD can also impede the formation of active TNFR oligomers and whether the CrmD D35A/Y36A mutant lacks this activity.

An efficient soluble decoy receptor must interact with the target cytokine but, more importantly, mask those residues of the ligand involved in the binding to the cognate cellular receptor. This might explain the lack of correlation that we observed between the binding and neutralizing activity of some mutants. CrmD residues contacting ligand amino acids not required for the interaction with the cellular receptor may contribute to the binding affinity but be irrelevant for the neutralizing activity of CrmD. Conversely, mutations of CrmD residues blocking key receptor-binding determinants of the ligand should be expected to be the most detrimental. In this regard, we have shown that mutations in a CRD2 groove under the 50s loop stripped CrmD of all its anti-TNFSF properties. This is consistent with the critical role assigned to this region in other TNFRs (18, 20, 22, 29) where it is known to constitute a critical binding site for a hydrophobic patch of the ligand where a highly conserved tyrosine residue is the major binding determinant (16). Mutation of this tyrosine is sufficient to abolish or seriously damage the receptor-binding capacity of many TNFSF ligands, including TNF, LTα, FasL, TRAIL, TL1A, and LIGHT (43–48). Therefore, this tyrosine should be a main target for any inhibitor of these cytokines. The severe deleterious effect of mutations in the CrmD CRD2 groove and the fact that all four ligands analyzed here conserve this important tyrosine (mTNF, Tyr165; hTNF, Tyr163; mLTα, Tyr139; hLTα, Tyr142) suggest that this is the case for CrmD. This may also explain the incapacity of CrmD N77F to bind and neutralize these cytokines. The addition of a large aromatic residue at the rim of the CRD2 groove may constitute a steric hindrance that prevents a competent fitting of the ligand's tyrosine. It is important to note that at present we cannot prove whether these inactive CrmD mutants were properly folded. However, their high expression yield and efficient secretion and the facts that their antichemokine activity was intact and that the localization of these mutations agrees with that of important ligand-binding determinants in many other receptors suggest that this is likely to be the case.

Despite the common binding mechanism deployed by the CRD2 of many TNFRs, these receptors are very ligand-specific. The determinants for this specificity appear to reside mostly in the CRD3, which binds to more highly variable secondary structural features of the ligand (31). The CRD3-mediated interactions are essential for the stability of the receptor–ligand complex. For instance, a Fas chimera carrying the CRD3 of TNFR1 failed to interact with FasL (49), and a T2 truncated mutant containing only the first two CRDs was unable to bind TNF (38). Here, we have shown that several residues at the C terminus of the CRD3 of CrmD significantly contribute to the binding and inhibitory activity of this vTNFR. Of note, these amino acids are located outside of the 90s loop at the C terminus of the CRD3 of CrmD, a region rarely implicated in ligand binding in cellular TNFRs, which might hint at a different binding mechanism by vTNFRs. More importantly, we proved that an EFE motif at the 90s loop of the CRD3 prevents the anti-hLTα activity of CrmD, whereas it does not affect its interaction with mLTα. In contrast, the 90s loop of the effective hLTα inhibitors CrmB and etanercept contains nonaromatic and less negatively charged motifs (LLK and ALS, respectively). To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that the CRD3 may contain not only ligand but also species specificity determinants.

Etanercept is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved antirheumatic drug that blocks not only TNF but also LTα. Although it has been proposed that this double inhibitory activity of etanercept could be beneficial in some instances (50), the role of LTα in inflammatory joint diseases is not well defined. Furthermore, a rheumatoid arthritis clinical trial concluded that an LTα-neutralizing antibody, pateclizumab, was not clinically different from placebo (51). On the contrary, several reports have shown that LTα is important for host defense against Mycobacterium infections (52–54), which constitutes one of the major infectious concerns in patients under anti-TNF therapy (55). Importantly, the LTα activity is more markedly decisive in these infections in the absence of TNF (56, 57), which simulates the undergoing immunological condition in these patients. Therefore, although the systemic blockade of TNF, a central cytokine of the immune response, is probably largely responsible for the infection vulnerability observed in etanercept patients, the anti-LTα activity of this drug may only contribute to aggravate the infections. A more specific anti-TNF treatment can be achieved with any of the four approved TNF monoclonal antibodies. However, it has been reported that the risk of infection associated with these antibodies can be even higher than with etanercept (58). This might be explained by the potent cytotoxic activity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, mediated by the Fc region of these antibodies, which may result in the destruction of TNF-bearing immune cells (6, 59). This cytotoxicity is diminished or missing in etanercept due to a structural defect in its Fc region (6). Furthermore, etanercept is known to be minimally immunogenic, whereas patients frequently develop neutralizing antibodies against infliximab and adalimumab (60). All this together suggests that a TNF-specific etanercept would be the ideal antirheumatic drug. Here, we demonstrate that the anti-hLTα activity of etanercept can be vastly hampered by making its 90s loop look more like that of CrmD in a A127E/L128F etanercept mutant. The slight defect observed in the anti-hTNF activity of this mutant could potentially be overcome in the clinic by a small dose increase without compromising hLTα-mediated immune functions. Therefore, this A127E/L128F variant could set the foundation for a safer second generation of etanercept featuring the benefits of a soluble decoy receptor and the high TNF specificity of the antibody therapy.

In conclusion, with the few exceptions discussed above, our results indicate that CrmD uses a similar molecular mechanism to bind and block TNF and LTα. This complicates the generation of recombinant ECTV expressing CrmD mutants active only against one of its TNFSF ligands, which would be invaluable tools to dissect the functions of these cytokines in the anti-poxvirus response. More detailed structural analyses of CrmD–TNF and CrmD–LTα complexes may reveal ligand-specific binding determinants not detected here. However, we have already proved this mutagenesis study useful for the generation of a single point ECTV mutant incapable of blocking mTNF and mLTα (27). More importantly, we demonstrated here that vTNFRs can provide a new perspective on TNFSF ligand-binding mechanisms and uncover novel specificity and binding determinants that would be overlooked in studies limited to cellular TNFRs. Given the strikingly different ligand-binding and specificity profiles across vTNFRs, structural studies on each of these viral decoy receptors have the potential to reveal new molecular determinants for a more potent and specific anti-TNF activity, which would refine our ability to neutralize harmful TNF responses in the clinic.

Experimental procedures

Cells and reagents

L929 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FCS. MOLT-4 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. Recombinant baculoviruses were generated and amplified in adherent Hi5 insect cells cultured in TC-100 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1× nonessential amino acids. Suspension Hi5 cells maintained in Express Five (Life Technologies) medium supplemented with 8 mm l-glutamine were used for the expression of recombinant protein. Recombinant cytokines were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and reconstituted and stored following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Construction of recombinant baculovirus

All the proteins described in this study were expressed by recombinant baculoviruses. The ECTV strain Hampstead CrmD coding sequence was extracted by PCR from a pBAC1 (Life Technologies)-derived plasmid termed pMS1 (11) using the primers Crm34 (5′-gcgggatccgatgttccgtatacacccattaatggg-3′) and CrmD33 (5′-gcgctcgaggcatctctttcacaatcatttgg-3′), which contained a BamHI and a XhoI restriction site, respectively. These primers amplified the CrmD gene lacking its endogenous signal peptide (residues 21–320). Upon restriction, CrmD was cloned into pAL7 (61), a modified pFastBac1 vector, in-frame with an N-terminal honeybee melittin signal peptide and a C-terminal V5-His6 tag. The resulting plasmid was termed pSP3. Similarly, the coding sequence for three truncated CrmD proteins, SECRET163 (residues 163–320), SECRET181 (residues 181–320), and CRD-CrmD (residues 21–162) were extracted from pSP3 by PCR using the primers CrmD36 (5′-gcgggatcctttaacagcatagatgtagaaattaatatgtatcc-3′) and CrmD33, CrmD31 (5′-cgcggatccgaattcaattcgagtatataggaagcagcagtac-3′) and CrmD33, and CrmD34 and CrmD87 (5′-gcgctcgaggcacatattacatctcctttagatg-3′), respectively, and cloned into pAL7 as described above. The resulting plasmids were termed pSP4, pSP5, and pSP6, respectively.

The CrmD point mutants were generated using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For this, pSP3 was used as a template in PCRs using the corresponding primer pair for each mutant (Table S1). Similarly, the etanercept A127E, L128F, and A127E/L128F mutants were generated using the primer pairs RM6mut1F (5′-ggctggtactgcgagctgagcaagcag-3′) and RM6mut1R (5′-ctgcttgctcagctcgcagtaccagcc-3′), RM6mut2F (5′-gctggtactgcgcgttcagcaagcaggaggg-3′) and RM6mut2R (5′-ccctcctgcttgctgaacgcgcagtaccagc-3′), and RM6mut3F (5′-cggctggtactgcgagttcagcaagcaggaggg-3′) and RM6mut3R (5′-ccctcctgcttgctgaactcgcagtaccagccg-3′), respectively, and pRM6 as a template. pRM6 is a pFastBac1-based plasmid containing the WT form of etanercept, consisting of the ligand-binding domain of human TNFR2 fused to the Fc portion of a human IgG (12). Mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing.

The plasmids described above were used to generate recombinant baculoviruses using the Bac-to-Bac system (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, viral stocks were amplified by infecting adherent Hi5 cells at low multiplicity of infection (0.1–0.01 pfu/cell).

Protein expression and purification

Hi5 suspension cells were infected with the corresponding recombinant baculovirus at high multiplicity of infection (2 pfu/cell). Supernatants were harvested 3 days after infection, clarified at 6,000 × g for 40 min, and then concentrated to 2.5 ml in a Stirred Ultrafiltration Cell 8200 (Millipore). The concentrate was desalted, and buffer was exchanged to 0.1 m phosphate buffer containing 300 mm NaCl and 10 mm imidazole using PD-10 desalting columns (GE Healthcare). His-tagged CrmD proteins were purified by metal chelate affinity chromatography using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid columns (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Etanercept proteins were purified using protein A–coupled Sepharose columns (Sigma). Protein-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and dialyzed in PBS. Final protein concentration was calculated by gel densitometry.

Cytotoxicity assays

The ability of CrmD, etanercept, and their mutants to inhibit TNFSF ligands was tested by cytotoxicity assays on L929 cells as described previously (12). Briefly, 20 ng/ml hTNF, mTNF, and hLTα were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of increasing amounts of recombinant protein. Due to its low specific activity, mLTα was used at 780 ng/ml. Subsequently, the cytokine–protein mixtures were added to L929 cells seeded at 12,000 cells/well in 96-well plates in the presence of 4 μg/ml actinomycin D (Sigma). Cell viability was assessed after 18 h using a Cell Titer Aqueous One Solution kit (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions, and the absorbance at 490 nm (A490) was determined in a Sunrise microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland). The A490 of all samples was normalized with the A490 of cells incubated only with the cytokine (0% viability). Cell viability for each sample was calculated in reference to the A490 obtained in wells where cells were incubated without cytokine (“media”; 100% viability).

Chemotaxis assay

MOLT-4 cells chemotaxis assays were performed using 96-well ChemoTx plates of 3-μm pore size (Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, MD). Before the experiment, cells were washed and resuspended at 10 × 106 cells/ml in 0.1% FCS in RPMI 1640 medium. Mouse Ccl25 (R&D Systems) at 70 nm was incubated with increasing molar ratios of recombinant protein at 37 °C for 30 min in the bottom wells. Subsequently, 2.5 × 105 cells were placed on the top filter, and cell migration was allowed for 4 h at 37 °C. Afterward, the filter was flushed with PBS to remove nonmigrated cells, and migration to the lower wells was determined as the A490 using a Cell Titter Aqueous One Solution kit (Promega). Cell migration was calculated in reference to the maximal migration obtained when the cells were incubated with the chemokine alone (100% cell migration).

SPR assays

The ligand-binding properties of recombinant proteins were characterized by SPR using a Biacore X biosensor (GE Healthcare). For binding assays, recombinant proteins were immobilized through their amine groups on CM4 chips at high density (1,000–2,000 response units). One flow cell of the chip was treated with buffer alone during immobilization to be used as a reference. TNFSF cytokines and chemokines were injected at 100 nm in HBS-EP buffer (0.01 m HEPES pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20) (GE Healthcare) at 10 μl/min for 3 min followed by a 2-min dissociation. The chip surface was regenerated between injections with 10 mm glycine HCl, pH 2.0.

For determination of kinetic affinity constants, recombinant proteins were immobilized on CM4 chips at low density (≈500 response units). Increasing concentrations of TNFSF cytokines and chemokines were injected in HBS-EP buffer at 30 μl/min for 2 min, and a 5-min dissociation was recorded. A 0.1–1000 nm concentration range of analyte was used. Between analyte injections, the chip surface was regenerated with 10 mm glycine HCl, pH 2.0. Kinetic data were globally fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir model using BIAevaluation 3.2 software. Bulk refractive index changes were removed by subtracting the responses recorded in the reference flow cell, and the response of a buffer injection was subtracted from all sensorgrams to remove systematic artifacts. To compare the binding affinity constants of CrmD truncated mutants, mean ± S.D. KD of 10 fittings from two independent experiments was calculated. To determine the kinetic affinity constants of CrmD point mutants, the average KD of 10 fittings containing sensorgrams for at least six different analyte concentrations from at least two independent experiments was calculated. The fitting providing the closest KD to the average KD was chosen to represent the kinetic affinity constants of each interaction.

Author contributions

S. M. P., B. R.-A., and A. A. conceptualization; S. M. P. and C. S. formal analysis; S. M. P. validation; S. M. P., C. S., B. R.-A., and A. A. investigation; S. M. P. and C. S. methodology; S. M. P. writing-original draft; S. M. P., C. S., B. R.-A., and A. A. writing-review and editing; B. R.-A. and A. A. supervision; A. A. resources; A. A. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Grants SAF2012-38957 and SAF2015-67485-R and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). S. M. Pontejo, C. Sanchez, and A. Alcami are inventors of a patent application on the potential use of the variant form of etanercept, but there is no company involved or development of this reagent as a drug so far.

This article was selected as one of our Editors' Picks.

This article contains Fig. S1 and Table S1.

- TNFSF

- tumor necrosis factor superfamily

- CRD

- cysteine-rich domain

- Crm

- cytokine response modifier

- ECTV

- ectromelia virus

- hLTα

- human lymphotoxin α

- hTNF

- human tumor necrosis factor

- KD

- binding affinity constant

- LT

- lymphotoxin

- mLTα

- mouse lymphotoxin α

- mTNF

- mouse tumor necrosis factor

- MYXV

- myxoma virus

- PLAD

- preligand assembly domain

- SCP

- SECRET-containing protein

- SECRET

- smallpox-encoded chemokine receptor

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor α

- TNFR1

- tumor necrosis factor receptor 1

- TNFR2

- TNF receptor 2

- TNFR

- TNFSF receptor

- vTNFR

- viral TNF decoy receptor

- EC50

- half-maximal effective concentration

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- CPXV

- cowpox virus

- VARV

- variola virus.

References

- 1. Aggarwal B. B. (2003) Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 745–756 10.1038/nri1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradley J. R. (2008) TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J. Pathol. 214, 149–160 10.1002/path.2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willrich M. A., Murray D. L., and Snyder M. R. (2015) Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: clinical utility in autoimmune diseases. Transl. Res. 165, 270–282 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray K. M., and Dahl S. L. (1997) Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75) Fc fusion protein (TNFR:Fc) in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Pharmacother. 31, 1335–1338 10.1177/106002809703101111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fellermann K. (2013) Adverse events of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Dig. Dis. 31, 374–378 10.1159/000354703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitoma H., Horiuchi T., Tsukamoto H., and Ueda N. (2018) Molecular mechanisms of action of anti-TNF-α agents—comparison among therapeutic TNF-α antagonists. Cytokine 101, 56–63 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alejo A., Pontejo S. M., and Alcami A. (2011) Poxviral TNFRs: properties and role in viral pathogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 691, 203–210 10.1007/978-1-4419-6612-4_21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu F. Q., Smith C. A., and Pickup D. J. (1994) Cowpox virus contains two copies of an early gene encoding a soluble secreted form of the type II TNF receptor. Virology 204, 343–356 10.1006/viro.1994.1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith C. A., Hu F. Q., Smith T. D., Richards C. L., Smolak P., Goodwin R. G., and Pickup D. J. (1996) Cowpox virus genome encodes a second soluble homologue of cellular TNF receptors, distinct from CrmB, that binds TNF but not LTα. Virology 223, 132–147 10.1006/viro.1996.0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loparev V. N., Parsons J. M., Knight J. C., Panus J. F., Ray C. A., Buller R. M., Pickup D. J., and Esposito J. J. (1998) A third distinct tumor necrosis factor receptor of orthopoxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3786–3791 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saraiva M., and Alcami A. (2001) CrmE, a novel soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor encoded by poxviruses. J. Virol. 75, 226–233 10.1128/JVI.75.1.226-233.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pontejo S. M., Alejo A., and Alcami A. (2015) Comparative biochemical and functional analysis of viral and human secreted tumor necrosis factor (TNF) decoy receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15973–15984 10.1074/jbc.M115.650119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bossen C., Ingold K., Tardivel A., Bodmer J.-L., Gaide O., Hertig S., Ambrose C., Tschopp J., and Schneider P. (2006) Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13964–13971 10.1074/jbc.M601553200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graham S. C., Bahar M. W., Abrescia N. G., Smith G. L., Stuart D. I., and Grimes J. M. (2007) Structure of CrmE, a virus-encoded tumour necrosis factor receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 660–671 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naismith J. H., and Sprang S. R. (1998) Modularity in the TNF-receptor family. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 74–79 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01164-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bodmer J.-L., Schneider P., and Tschopp J. (2002) The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 19–26 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01995-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang G. (2004) Tumor necrosis factor family ligand-receptor binding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 154–160 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hymowitz S. G., Christinger H. W., Fuh G., Ultsch M., O'Connell M., Kelley R. F., Ashkenazi A., and de Vos A. M. (1999) Triggering cell death: the crystal structure of Apo2L/TRAIL in a complex with death receptor 5. Mol. Cell 4, 563–571 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80207-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu C., Walter T. S., Huang P., Zhang S., Zhu X., Wu Y., Wedderburn L. R., Tang P., Owens R. J., Stuart D. I., Ren J., and Gao B. (2010) Structural and functional insights of RANKL-RANK interaction and signaling. J. Immunol. 184, 6910–6919 10.4049/jimmunol.0904033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhan C., Patskovsky Y., Yan Q., Li Z., Ramagopal U., Cheng H., Brenowitz M., Hui X., Nathenson S. G., and Almo S. C. (2011) Decoy strategies: the structure of TL1A:DcR3 complex. Structure 19, 162–171 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan F. K., Chun H. J., Zheng L., Siegel R. M., Bui K. L., and Lenardo M. J. (2000) A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science 288, 2351–2354 10.1126/science.288.5475.2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mukai Y., Nakamura T., Yoshikawa M., Yoshioka Y., Tsunoda S., Nakagawa S., Yamagata Y., and Tsutsumi Y. (2010) Solution of the structure of the TNF-TNFR2 complex. Sci. Signal. 3, ra83 10.1126/scisignal.2000954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siegel R. M., Frederiksen J. K., Zacharias D. A., Chan F. K., Johnson M., Lynch D., Tsien R. Y., and Lenardo M. J. (2000) Fas preassociation required for apoptosis signaling and dominant inhibition by pathogenic mutations. Science 288, 2354–2357 10.1126/science.288.5475.2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schreiber M., Sedger L., and McFadden G. (1997) Distinct domains of M-T2, the myxoma virus tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor homolog, mediate extracellular TNF binding and intracellular apoptosis inhibition. J. Virol. 71, 2171–2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sedger L. M., Osvath S. R., Xu X.-M., Li G., Chan F. K., Barrett J. W., and McFadden G. (2006) Poxvirus tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-like T2 proteins contain a conserved preligand assembly domain that inhibits cellular TNFR1-induced cell death. J. Virol. 80, 9300–9309 10.1128/JVI.02449-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alejo A., Ruiz-Argüello M. B., Ho Y., Smith V. P., Saraiva M., and Alcami A. (2006) A chemokine-binding domain in the tumor necrosis factor receptor from variola (smallpox) virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5995–6000 10.1073/pnas.0510462103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alejo A., Ruiz-Argüello M. B., Pontejo S. M., Fernández de Marco M. D. M., Saraiva M., Hernáez B., and Alcamí A. (2018) Chemokines cooperate with TNF to provide protective anti-viral immunity and to enhance inflammation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1790 10.1038/s41467-018-04098-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan F. K. (2000) The pre-ligand binding assembly domain: a potential target of inhibition of tumour necrosis factor receptor function. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, Suppl. 1, i50–i53 10.1136/ard.59.suppl_1.i50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Banner D. W., D'Arcy A., Janes W., Gentz R., Schoenfeld H. J., Broger C., Loetscher H., and Lesslauer W. (1993) Crystal structure of the soluble human 55 kd TNF receptor-human TNFβ complex: implications for TNF receptor activation. Cell 73, 431–445 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90132-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cha S. S., Sung B. J., Kim Y. A., Song Y. L., Kim H. J., Kim S., Lee M. S., and Oh B. H. (2000) Crystal structure of TRAIL-DR5 complex identifies a critical role of the unique frame insertion in conferring recognition specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31171–31177 10.1074/jbc.M004414200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magis C., van der Sloot A. M., Serrano L., and Notredame C. (2012) An improved understanding of TNFL/TNFR interactions using structure-based classifications. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 353–363 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Compaan D. M., and Hymowitz S. G. (2006) The crystal structure of the costimulatory OX40-OX40L complex. Structure 14, 1321–1330 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson C. A., Warren J. T., Wang M. W., Teitelbaum S. L., and Fremont D. H. (2012) RANKL employs distinct binding modes to engage RANK and the osteoprotegerin decoy receptor. Structure 20, 1971–1982 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luan X., Lu Q., Jiang Y., Zhang S., Wang Q., Yuan H., Zhao W., Wang J., and Wang X. (2012) Crystal structure of human RANKL complexed with its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin. J. Immunol. 189, 245–252 10.4049/jimmunol.1103387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reading P. C., Khanna A., and Smith G. L. (2002) Vaccinia virus CrmE encodes a soluble and cell surface tumor necrosis factor receptor that contributes to virus virulence. Virology 292, 285–298 10.1006/viro.2001.1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cunnion K. M. (1999) Tumor necrosis factor receptors encoded by poxviruses. Mol. Genet. Metab. 67, 278–282 10.1006/mgme.1999.2878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xue X., Lu Q., Wei H., Wang D., Chen D., He G., Huang L., Wang H., and Wang X. (2011) Structural basis of chemokine sequestration by CrmD, a poxvirus-encoded tumor necrosis factor receptor. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002162 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schreiber M., and McFadden G. (1996) Mutational analysis of the ligand-binding domain of M-T2 protein, the tumor necrosis factor receptor homologue of myxoma virus. J. Immunol. 157, 4486–4495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan F. K. (2007) Three is better than one: pre-ligand receptor assembly in the regulation of TNF receptor signaling. Cytokine 37, 101–107 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smulski C. R., Beyrath J., Decossas M., Chekkat N., Wolff P., Estieu-Gionnet K., Guichard G., Speiser D., Schneider P., and Fournel S. (2013) Cysteine-rich domain 1 of CD40 mediates receptor self-assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10914–10922 10.1074/jbc.M112.427583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clancy L., Mruk K., Archer K., Woelfel M., Mongkolsapaya J., Screaton G., Lenardo M. J., and Chan F. K. (2005) Preligand assembly domain-mediated ligand-independent association between TRAIL receptor 4 (TR4) and TR2 regulates TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18099–18104 10.1073/pnas.0507329102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Branschädel M., Aird A., Zappe A., Tietz C., Krippner-Heidenreich A., and Scheurich P. (2010) Dual function of cysteine rich domain (CRD) 1 of TNF receptor type 1: conformational stabilization of CRD2 and control of receptor responsiveness. Cell. Signal. 22, 404–414 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamagishi J., Kawashima H., Matsuo N., Ohue M., Yamayoshi M., Fukui T., Kotani H., Furuta R., Nakano K., and Yamada M. (1990) Mutational analysis of structure–activity relationships in human tumor necrosis factor-α. Protein Eng. 3, 713–719 10.1093/protein/3.8.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goh C. R., Loh C. S., and Porter A. G. (1991) Aspartic acid 50 and tyrosine 108 are essential for receptor binding and cytotoxic activity of tumour necrosis factor β (lymphotoxin). Protein Eng. 4, 785–791 10.1093/protein/4.7.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schneider P., Bodmer J. L., Holler N., Mattmann C., Scuderi P., Terskikh A., Peitsch M. C., and Tschopp J. (1997) Characterization of Fas (Apo-1, CD95)-Fas ligand interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18827–18833 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hymowitz S. G., O'Connell M. P., Ultsch M. H., Hurst A., Totpal K., Ashkenazi A., de Vos A. M., and Kelley R. F. (2000) A unique zinc-binding site revealed by a high-resolution X-ray structure of homotrimeric Apo2L/TRAIL. Biochemistry 39, 633–640 10.1021/bi992242l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhan C., Yan Q., Patskovsky Y., Li Z., Toro R., Meyer A., Cheng H., Brenowitz M., Nathenson S. G., and Almo S. C. (2009) Biochemical and structural characterization of the human TL1A ectodomain. Biochemistry 48, 7636–7645 10.1021/bi900031w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rooney I. A., Butrovich K. D., Glass A. A., Borboroglu S., Benedict C. A., Whitbeck J. C., Cohen G. H., Eisenberg R. J., and Ware C. F. (2000) The lymphotoxin-β receptor is necessary and sufficient for LIGHT-mediated apoptosis of tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14307–14315 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Orlinick J. R., Vaishnaw A., Elkon K. B., and Chao M. V. (1997) Requirement of cysteine-rich repeats of the Fas receptor for binding by the Fas ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28889–28894 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neregård P., Krishnamurthy A., Revu S., Engström M., af Klint E., and Catrina A. I. (2014) Etanercept decreases synovial expression of tumour necrosis factor-α and lymphotoxin-α in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 43, 85–90 10.3109/03009742.2013.834964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kennedy W. P., Simon J. A., Offutt C., Horn P., Herman A., Townsend M. J., Tang M. T., Grogan J. L., Hsieh F., and Davis J. C. (2014) Efficacy and safety of pateclizumab (anti-lymphotoxin-α) compared to adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: a head-to-head phase 2 randomized controlled study (The ALTARA Study). Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, 467 10.1186/s13075-014-0467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Olleros M. L., Guler R., Corazza N., Vesin D., Eugster H.-P., Marchal G., Chavarot P., Mueller C., and Garcia I. (2002) Transmembrane TNF induces an efficient cell-mediated immunity and resistance to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection in the absence of secreted TNF and lymphotoxin-alpha. J. Immunol. 168, 3394–3401 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roach D. R., Briscoe H., Saunders B., France M. P., Riminton S., and Britton W. J. (2001) Secreted lymphotoxin-α is essential for the control of an intracellular bacterial infection. J. Exp. Med. 193, 239–246 10.1084/jem.193.2.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ehlers S., Hölscher C., Scheu S., Tertilt C., Hehlgans T., Suwinski J., Endres R., and Pfeffer K. (2003) The lymphotoxin beta receptor is critically involved in controlling infections with the intracellular pathogens Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 170, 5210–5218 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gardam M. A., Keystone E. C., Menzies R., Manners S., Skamene E., Long R., and Vinh D. C. (2003) Anti-tumour necrosis factor agents and tuberculosis risk: mechanisms of action and clinical management. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 148–155 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00545-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bopst M., Garcia I., Guler R., Olleros M. L., Rülicke T., Müller M., Wyss S., Frei K., Le Hir M., and Eugster H. P. (2001) Differential effects of TNF and LTα in the host defense against M. bovis BCG. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 1935–1943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jacobs M., Brown N., Allie N., and Ryffel B. (2000) Fatal Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in TNF-LT-α-deficient mice. Clin. Immunol. 94, 192–199 10.1006/clim.2000.4835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wallis R. S., Broder M. S., Wong J. Y., Hanson M. E., and Beenhouwer D. O. (2004) Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 1261–1265 10.1086/383317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mitoma H., Horiuchi T., Tsukamoto H., Tamimoto Y., Kimoto Y., Uchino A., To K., Harashima S., Hatta N., and Harada M. (2008) Mechanisms for cytotoxic effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents on transmembrane tumor necrosis factor α-expressing cells: comparison among infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1248–1257 10.1002/art.23447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Garcês S., Demengeot J., and Benito-Garcia E. (2013) The immunogenicity of anti-TNF therapy in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 1947–1955 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Montanuy I., Alejo A., and Alcami A. (2011) Glycosaminoglycans mediate retention of the poxvirus type I interferon binding protein at the cell surface to locally block interferon antiviral responses. FASEB J. 25, 1960–1971 10.1096/fj.10-177188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yang J., Yan R., Roy A., Xu D., Poisson J., and Zhang Y. (2015) The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods 12, 7–8 10.1038/nmeth.3213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data