Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading causes of death in the United States, and advancing age is a primary risk factor. Impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and increased stiffening of the arteries with aging are independent predictors of CVD. Increased tissue and systemic oxidative stress and inflammation underlie this age-associated arterial dysfunction. Calorie restriction (CR) is the most powerful intervention known to increase life span and improve age-related phenotypes, including arterial dysfunction. However, the translatability of long-term CR to clinical populations is limited, stimulating interest in the pursuit of pharmacological CR mimetics to reproduce the beneficial effects of CR. The energy-sensing pathways, mammalian target of rapamycin, AMPK, and sirtuin-1 have all been implicated in the beneficial effects of CR on longevity and/or physiological function and, as such, have emerged as potential targets for therapeutic intervention as CR mimetics. Although manipulation of each of these pathways has CR-like benefits on arterial function, the magnitude and/or mechanisms can be disparate from that of CR. Nevertheless, targeting these pathways in older individuals may provide some benefits against arterial dysfunction and CVD. The goal of this review is to provide a brief discussion of the mechanisms and pathways underlying age-associated dysfunction in large arteries, explain how these are impacted by CR, and to present the available evidence, suggesting that targets for energy-sensing pathways may act as vascular CR mimetics.

Keywords: aging, AMPK, arterial stiffness, calorie restriction, endothelial function, inflammation, mTOR, oxidative stress, SIRT-1, vasodilation

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE, VASCULAR FUNCTION, AND AGING

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, with an estimated 92 million US adults presenting with at least one form of CVD. Among these, ~47 million are estimated to be over 60 yr of age (9). It is estimated that by 2030, almost 44% of the US population will have some form of CVD, and the projected direct medical costs is estimated to reach over $800 billion (9). The staggering health care and economic burden associated with CVD makes the identification of therapeutic strategies to treat CVD critical. Importantly, advanced age is the major risk factor for development of CVD (31, 74), with the prevalence of CVD increasing with age in both men and women (9). Impaired endothelial function and increased large artery stiffness (35, 42) characterize the vascular aging phenotype and represent strong predictors of CV events and clinical CVD.

ARTERIAL DYSFUNCTION IN AGING

While once thought to be an inert barrier, the endothelium is now known to play an important role in vascular homeostasis (39). In addition to its role in determining vascular permeability, the endothelium also contributes to the control of arterial tone via production of vasodilators and vasoconstrictor substances, as well as to angiogenesis and to the oxidative, inflammatory, and thrombotic phenotype of the artery (105). Nitric oxide (NO) is a key endothelium-derived vasodilator in arteries that can broadly impact endothelial function (129). With aging, endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) is impaired in both animal models, assessed in vitro in excised arteries and human subjects, assessed by flow-mediated dilation (36). This impairment in EDD is associated with a reduction in NO bioavailability (36). Beyond enhancing vascular tone leading to increased vascular resistance, reduced NO bioavailability may also impair angiogenic responses (97), as well as contribute to the prooxidant (137), proinflammatory (139), and prothrombotic (46) arterial phenotype that is associated with aging (131), thus, contributing to the increased prevalence of CVD in older adults (44).

In addition to impaired endothelial function, stiffening of the large elastic arteries with aging is also an important contributor to increased CVD risk and is associated with pathophysiological conditions, such as hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, subendocardial ischemia, and cardiac fibrosis (103). Stiffening of the large arteries also leads to a widening of the pulse pressure and a greater central forward pressure wave, a significant predictor of a major CVD event (24). The large elastic arteries function as a conduit for blood to the periphery and as a capacitance organ to dampen the pulse pressure caused by the ejection of blood from the heart during systole. Clinically and experimentally in both human subjects and animal models, arterial stiffness can be assessed in vivo by aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV). This is accomplished using Doppler ultrasound to assess the time it takes for the pulse wave to travel a known distance across the large arteries, with higher PWV, indicative of stiffer large elastic arteries. With aging, increases in collagen abundance (114) and crosslinking (115) combined with decreases in elastin density (48) within the arterial wall contribute to increased stiffness. In addition, age-associated increases in vascular resistance may also contribute to changes in large artery stiffness in vivo (62).

Loss of elasticity of the large arteries diminishes diastolic pressure, widening pulse pressure, and exposing the microvasculature to increased fluctuations in pressure (103). The downstream effect can be end-organ dysfunction, particularly to vulnerable regions, such as the cerebral and renal circulations (103), but, likely, loss of elasticity has effects in multiple other tissues and organs. This occurs through alterations in the components of the forward and reflected pulse wave, such that there is an increased amplitude of the reflected wave, and this has been associated with end-organ damage and increased cardiac load (133). In addition, studies in cultured endothelial cells suggest that a stiffer matrix mimicking that in older age promotes proatherosclerotic responses to shear stress. For example, endothelial cells cultured to a stiffer matrix demonstrate decreased alignment, a reduction in barrier function, and reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation in response to athero-protective laminar shear stress (72). Thus, age-related dysfunction of the vascular endothelium and increases in arterial stiffness act in concert to increase the risk of CVD in older adults. As such, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying these vascular changes may inform therapeutics to combat CVD in this population.

ROLE OF OXIDATIVE STRESS AND INFLAMMATION IN AGE-ASSOCIATED ARTERIAL DYSFUNCTION

A key mechanism underlying age-associated reductions in EDD and NO bioavailability, as well as increases in large artery stiffness, is the development of vascular oxidative stress (42, 93). Age-related vascular oxidative stress is associated with increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anion (110) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (140). Enzymatic ROS production through NADPH oxidase (NOX) has been implicated in age-related vascular oxidative stress, and NOX exists in seven isoforms, with different expression patterns across tissues. While NOX4 is the most abundant NADPH oxidase isoform in endothelial cells (2) and is a constitutively active form of the enzyme (80), this isoform produces hydrogen peroxide rather than superoxide (120). The age-associated increase in arterial ROS is associated with increased expression of the cytosolic subunits, p47phox and p67phox (35, 40), components of the NOX2 isoform (17) and is mediated by increased activity of this oxidant enzyme (35, 40), mitochondrial dysfunction, and reductions in the antioxidant enzyme manganese (Mn) superoxide dismutase (SOD) (35, 40, 77). Superoxide mediates the age-associated reduction in NO bioavailability by reacting with NO to form peroxynitrite. This reaction quenches bioavailable NO and leads to the nitration of tyrosine residues on proteins (nitrotyrosine) in arteries of rodents and humans (35, 40, 76). Functionally, these oxidative stress-driven biochemical events impair EDD in both mice and humans (40, 42, 76, 93) and contribute to stiffer large elastic arteries in rodent models (43, 124) and older women (94). Thus, oxidative stress-associated suppression of NO is a cause of dysfunction in older arteries.

Aging is also associated with chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation that is characterized by increases in circulating C-reactive protein (CRP), proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) (34, 35). Among older adults, circulating markers of inflammation, such as CRP and IL-6, are positively related to aortic PWV (116) and inversely related to EDD (128). In addition, the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB is increased in endothelial cells of older humans (34, 35), and genetic blockade of NF-κB activation in endothelial cells extends life span (57). NF-κB is a proinflammatory transcription factor that resides in the cytoplasm through its interaction with the inhibitory protein IκB-α (69). In response to inflammatory stimuli (69) or ROS (117), IKKβ is activated and subsequently phosphorylates IκB-α, releasing its inhibition and allowing NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus, where it can activate gene transcription of its downstream proinflammatory target genes, such as TNF-α and IL-6 (69). Importantly, this age-associated increase in proinflammatory signaling has been implicated in arterial dysfunction in older rodents and humans. For example, NF-κB inhibition by salicylate (salsalate in humans) improves EDD in aged mice (77) and in overweight/obese middle-aged and older adults (101), and both salsalate (63) and inhibition of TNF-α (3) improve aortic PWV in older adults, supporting a causative role for inflammation in age-related arterial dysfunction.

Oxidative stress and inflammation act in a feedforward manner to negatively impact arterial function with aging. For example, proinflammatory signaling in the vasculature can lead to the local recruitment of immune cells that produce ROS and contribute to a prooxidant environment. Furthermore, inflammatory signaling can stimulate superoxide production and oxidative stress by inducing transcription of redox-sensitive genes like those encoding subunits of NADPH oxidase (87). Thus, oxidative and inflammatory pathways interact with advancing age to induce and perpetuate arterial dysfunction.

BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF CALORIE RESTRICTION ON ARTERIAL FUNCTION IN AGING

Calorie restriction (CR) is typically a lifelong intervention, initiated after sexual maturity, in which caloric intake is restricted by 40% compared with ad libitum (AL) intake without malnutrition. CR has been demonstrated to improve maximal and/or median life span, as well as physiological function in rodents and nonhuman primates (134). Although CR is one of the most effective antiaging interventions, CR is not universally effective, with some studies demonstrating no improvement in age-associated loss of body fat, bone mass, and density in nonhuman primates, as well as no effect or even a shortened life span in some inbred mouse strains (81, 82, 112). Nevertheless, CR has been associated with a dramatic reduction in CVD in nonhuman primates (23), a protection against cardiac ischemia (41), an improvement in EDD and NO bioavailability (26, 130), as well as a reduction in large artery stiffness (37) and reduced wall thickness in small cerebral arteries (37, 130) in aged rodents (Fig. 1). Importantly, the effects of CR to improve EDD and NO bioavailability can be, at least partially, recapitulated when mice are exposed to short-term CR (3–6 wk) that is initiated in old age (110). Furthermore, recent evidence from the CALERIE trial, in which nonobese adults were randomized to 25% CR for 2 yr, indicates the CR also slowed biological aging assessed by published biomarker algorithms, i.e., the Klemera-Doubal and homeostatic dysregulation methods (8) and reduced CVD risk factors (106), such as serum lipids and blood pressure (96) in middle-aged adults.

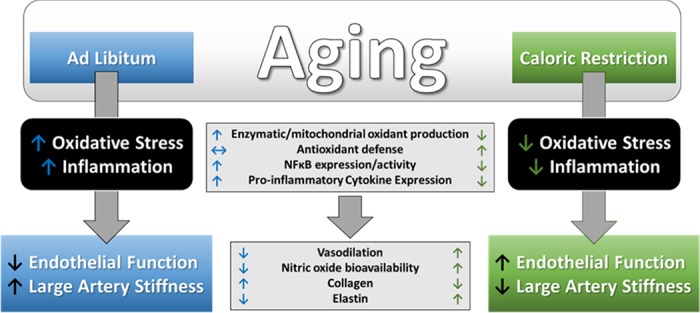

Fig. 1.

Effects of aging and caloric restriction (CR) on arterial function. Age-associated increases in oxidative stress and inflammation lead to endothelial dysfunction and large artery stiffening that is prevented by lifelong CR. With aging, oxidative stress and inflammation are the consequence of increases in oxidant production, NF-κB activation, and proinflammatory cytokine/adhesion molecule expression in arteries that contribute to reduced vasodilation and nitric oxide bioavailability, as well as to alterations in the structural components of the artery, i.e., collagen and elastin, favoring increased arterial stiffness. Life-long CR prevents these age-associated arterial changes.

The vascular benefits of CR appear to be, at least partially, mediated by an attenuation of age-related oxidative stress (Fig. 1), such that in vitro treatment of arteries with the superoxide scavenger TEMPOL improves EDD and NO bioavailability in old AL-fed (40), but not in old mice after CR (37, 110). These results are indicative of an attenuation of the superoxide-mediated suppression of EDD/NO after CR (37, 110, 130). Furthermore, both long-term (37, 130) and short-term (110) CR reduces arterial oxidative stress, as evidenced by a reduced abundance of nitrotyrosine (37, 110). Furthermore, age-related elevations in arterial superoxide production, measured by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (37, 110, 130) or lucigenin chemiluminescence assay (26), are reduced after CR. While increases in superoxide production with aging are associated with increased expression and activity of the oxidant enzyme, NADPH oxidase (40), CR appears to constrain this source of ROS, with the expression of NOX4 and the p67 subunit of NOX2, as well as the activity of NADPH oxidase reduced in old mice after CR (25, 37, 110). Mitochondrial ROS production, another important source of arterial oxidative stress, is also elevated in aged primary cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. In addition, there is functional evidence of Mn SODʼs role in mitochondrial ROS production. Mice with haplodeficiency in Mn SOD increase vascular superoxide production with advancing age (18, 136), and this source of ROS production is reduced in cells isolated from mice after life-long CR (25).

In addition to increased oxidant production, an inadequate antioxidant defense also contributes to increased tissue oxidative stress in aging. SODs are critical antioxidant enzymes that convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), playing a primary role in ROS removal (47). Although at high concentrations, H2O2 is, itself, a ROS that can impair vascular function (113), the H2O2 produced through the actions of SOD can also promote vasodilation via direct actions as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (66), as well as indirectly by inducing the expression of eNOS, the enzyme responsible for the production of NO (38). Interestingly, the importance of H2O2 as a vasodilator differs across the life span and with the emergence of coronary artery disease (CAD). Indeed, recent evidence demonstrates that the primary mediator of flow-induced dilation in coronary arteries shifts from prostacyclin in youth to NO in healthy adulthood and is again altered in the presence of CAD to H2O2 (10).

Although elevated superoxide production should signal an increase in antioxidant defenses, total antioxidant capacity is reduced (65), and the expression and activity of critical antioxidant enzymes fail to increase with aging. For example, neither copper zinc (CuZn)—the intracellular isoform—nor manganese (Mn)—the mitochondrial isoform of SOD (37, 40, 110)—is increased in arteries of old mice (37, 40). Although the expression of extracellular (ec) SOD has been shown to be either unchanged (37, 78) or increased (40) in arteries of old mice, there is no increase in activity of any of these SOD isoforms in arteries with advancing age (37, 40, 110). Thus, an inadequate response in SOD expression/activity with aging may contribute to both an excess of superoxide leading to reduced NO bioavailability, as well as to an inadequate H2O2 production that both may contribute to impaired vasodilation (66). Further, there is direct functional evidence in CuZn SOD heterozygous mice that reductions in CuZn SOD increase superoxide and limit vasodilation and that these effects are exacerbated with advancing age (33). In addition to reducing the production of ROS, CR-mediated improvements in oxidative stress are also associated with improved antioxidant defenses. Indeed, in contrast to AL aging, total antioxidant capacity of the serum of old CR rats does not differ from that of young rats (65). In addition, arterial expression of the antioxidants, Mn, CuZn, and ec SOD (37, 110), as well as total SOD activity (110), are increased in aged mice after CR. Thus, a primary mechanism underlying the beneficial effects on the vasculature appears to be through a reduction in oxidative stress that is mediated by both a reduction in oxidant production and an improvement in antioxidant defenses.

Although less is known regarding the effects of CR on arterial inflammation, there is evidence that CR induces an anti-inflammatory effect (Fig. 1). With aging, inflammation impairs EDD by contributing to superoxide-mediated suppression of NO bioavailability (77) and contributes to the stiffening of large elastic arteries by increasing vascular smooth muscle tone, which results from reduced NO bioavailability and/or increased concentrations of local or circulating constrictors (73), as well as by stimulating increased collagen production, a structural component of the arterial wall that confers stiffness. Inflammation-associated increases in collagen production are downstream of activation of NADPH oxidase-derived ROS production (127), highlighting the complex interactions of oxidative stress and inflammation in the aged vasculature. CR can act directly to reduce inflammation by lowering expression of proinflammatory adhesion molecules and cytokines, as well as indirectly by reducing the vascular inflammation associated with ROS. Indeed, CR reduces serum abundance of the adhesion molecules E-selectin, P-selectin, and VCAM-1 (141), as well as arterial gene expression for ICAM-1 in old rats (26). In addition, age-associated increases in serum cytokine expression, e.g., CRP (65), IL-6, and TNF-α (125), as well as endothelial cell secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (25) are all reduced in rodents after CR. Although the mechanisms are incompletely understood, these anti-inflammatory effects may be downstream of attenuated NF-κB activity, as both gene expression and activity of NF-κB are reduced in nuclear extracts of arteries and endothelial cells from CR compared with AL-fed old mice (25, 26). Likewise, it appears that the age-associated decrease in activity of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκB-α (77, 135), is attenuated after CR (135). These anti-inflammatory effects may translate clinically, as serum CRP is reduced in human subjects after CR (45). Taken together, it appears that a reduction in NF-κB-associated inflammatory signaling may also contribute to improved vascular dysfunction in aged mice after CR.

ROLE OF mTOR, AMPK, AND SIRT-1 IN CR

While the molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of CR on arterial function are still being explored, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation via the modulation of energy-sensing pathways has been suggested as a possible mechanism. Elucidating these upstream pathways is critical because, despite the strong evidence for the beneficial effects of CR, the translatability of lifelong 40% CR to humans is limited. Nevertheless, evidence from the CALERIE trial suggests that shorter-term 25% CR is effective at delaying age-related phenotypes and improving CVD risk factors in adults (8, 96), suggesting that manipulation of pathways involved in the beneficial effects of CR in animal models may be also be efficacious in adults. Previous studies have identified energy-sensing pathways, including the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMPK, and sirtuin (SIRT) pathways as critical modulators of longevity after CR (12, 52, 68, 84). As such, these pathways may hold promise as CR mimetics.

Rapamycin is an inhibitor of mTOR that was discovered more than 30 yr ago from an Easter Island soil sample (122). It is a potent antifungal metabolite produced from bacteria that, in addition to its antifungal properties, was also found to have antiproliferative and immunosuppressant properties when used in high concentrations (83). mTOR is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase that responds to changes in energy balance or growth factors and regulates many cellular functions, including translation, transcription, protein turnover, metabolism, and stress responses (132). Early studies treating yeast and flies with rapamycin revealed that inhibition of mTOR activity increased life span (67), and a follow-up study reproduced these longevity-related findings in mice (56), demonstrating that inhibiting mTOR via dietary rapamycin could not only increase life span but may also delay age-associated phenotypes. Genetic manipulation of a downstream target of mTOR, ribosomal S6 protein kinase (S6K1), supported these findings by demonstrating that reduced mTOR signaling increased life span and ameliorated age-associated reductions in bone mineral density and insulin sensitivity (119), suggesting that inhibition of mTOR signaling may be a mechanism by which CR exerts its beneficial effects. Although most studies to date examining the role of mTOR in cellular homeostasis have focused on insulin and nutrient signaling, enhanced AMPK signaling was implicated in the blunting of age-related physiological dysfunction after mTOR inactivation in S6K1 knockout mice (119). Although, 6 mo of 35–40% CR initiated at 3 mo of age did not alter phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K, or TSC2 in the aorta, skeletal muscle, liver, brain, kidney, and lung (121), these studies were performed in young rats and as such, the effect of CR on mTOR pathway intermediates needs to be assessed in old animals in which mTOR signaling is elevated. Taken together, these studies suggest that reducing mTOR signaling can mimic many of the effects of CR, but the direct role of mTOR in the beneficial effects of CR remains to be elucidated.

AMPK is also a highly conserved heterotrimeric serine-threonine kinase that, like mTOR, is an important energy-sensing signaling protein integrating energy balance, metabolism, and stress resistance (55, 59). AMPK is activated in response to increases in the AMP:ATP ratio. Pharmacologically, AMPK activity can be increased directly after treatment with aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) and indirectly after metformin treatment. AICAR is an adenosine analog taken up into cells by adenosine transporters and phosphorylated by adenosine kinase, resulting in accumulation of AICA-Riboside monophosphate (ZMP), which mimics the stimulating effect of AMP on AMPK. Although the precise mechanism of action is not known, metformin is known to act by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I, altering the AMP:ATP ratio and leading to AMPK activation (7). While the effects of long-term AICAR treatment on longevity are not known, increased life span has been demonstrated after long-term metformin treatment (5). Although age-related endothelial dysfunction is associated with decreased arterial AMPK (79), AMPK activity was shown to be unchanged in heart, muscle, and liver after 4 mo of CR (51). Still, it remains to be elucidated what role, if any, AMPK activation may play in the beneficial effects of CR on vascular function per se.

Sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) is a nuclear NAD-dependent nuclear deacetylase (21) that acts by deacetylating histone and nonhistone proteins (102) impacting gene expression, metabolism, and aging (104). Across multiple tissues, SIRT-1 activity has been associated with reductions in oxidative stress, inflammation, and proapoptotic signaling, as well as in improvements in insulin sensitivity, DNA damage repair, and telomere stability (104). SIRT-1 also appears to play a critical role in longevity as overexpression of SIRT-1 recapitulates the CR phenotype (13), and deletion of SIRT-1 abolishes the life span extension afforded by CR (12). With aging, arterial SIRT-1 expression is reduced (36), and this effect is attenuated by CR (22). Although in vivo treatment of mice with a nonspecific SIRT-1 activator, resveratrol, failed to increase life span (100), there were improvements in the vascular aging phenotype after reseveratrol treatment (28).

Interestingly, these signaling pathways do not act independently, but rather there is a large degree of interdependence between mTOR, AMPK, and SIRT-1 activities. For example, there is a reciprocal relationship between these kinases, as AMPK activation can result in direct mTOR inhibition (53), and AMPK signaling is upregulated as a consequence of reduced mTOR signaling (119). In contrast to mTOR, which is elevated in aged arteries (78), AMPK expression and activity are reduced in arteries with aging (79). Moreover, SIRT-1 directly, and negatively, interacts with mTOR, such that deficiency or inhibition of SIRT-1 results in mTOR activation (50). Cross talk also exists between SIRT-1 and AMPK, such that decreases in AMPK activity reduce SIRT-1 responsiveness to low-energy states (19). Although the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of these pathways on longevity and health are incompletely understood, reductions in oxidative stress and inflammation may be key players.

OTHER POTENTIAL MEDIATORS OF THE BENEFICIAL EFFECTS OF CR ON VASCULAR AGING

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) may play a role in age-associated arterial dysfunction and the beneficial effects of CR. CR and PPARs regulate the expression of many common genes, suggesting that the effects of CR are mediated by PPARs, and the role of PPARs in CR and long-lived mutant mice has been previously reviewed (90). Direct evidence for a role of PPARγ in age-associated arterial dysfunction per se comes from a study in which bradykinin (BK)-induced dilation was assessed in isolated mesenteric arteries from younger and older adults that were treated in vitro with the PPARγ agonist, GW7647. Older age was associated with a reduction in vasodilation to BK that was improved after GW7647 treatment, suggesting a role for reduced PPARγ in impaired vasodilator responses in aging (4). Although PPARγ has been demonstrated to have CR-like effects on transcription (6), suggesting that PPARγ agonists may act as CR mimetics, there is also evidence for negative feedback regulation between PPARγ and the longevity gene SIRT-1. Indeed, PPARγ binds the SIRT-1 promoter negatively regulating transcription of SIRT-1 and can also inhibit SIRT-1 activity through direct interaction (54). Thus, although PPARγ activation may have some CR-mimetic transcriptional effects, it remains unclear what role this factor plays in the beneficial effects of CR on the vasculature per se.

Increased activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is also associated with both oxidative stress and inflammation, processes linked to the endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffening associated with vascular aging, and the role of RAAS in arterial stiffness (86) and the vascular aging phenotype have previously been reviewed (98). Briefly, it appears that hyperactivity of RAAS leads to arterial dysfunction by attenuating vasodilators, such as bradykinin, and increasing arterial fibrosis (98). Although it is unclear what role RAAS plays in the beneficial effects of CR in the absence of preexisting obesity, CR-associated weight loss in obese subjects leads to lower blood pressure that was associated with lower RAAS activity mediated by a reduction in renin (60). Thus, reductions in the RAAS system may also play a role in the beneficial effects of CR, and drugs targeting components of this system may be efficacious as CR mimetics.

TARGETING ENERGY-SENSING PATHWAYS TO REVERSE ARTERIAL AGING

Rapamycin

While traditionally used only as an immunosuppressant in transplant patients, rapamycin has recently been found to have many beneficial effects, including actions as a tumor suppressant in certain cancers (107), as well as being a potential therapeutic target for cardiac hypertrophy (123) and vascular restenosis (138). Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin reduces mitochondrial ROS production in the livers of middle-aged mice (89), as well as protects the mitochondria from oxidative stress (64). In addition, rapamycin increases cardiac MnSOD expression (29) and the expression of CuZn SOD in spermatogonial stem cells (71). In addition, rapamycin also led to a downregulation of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in these spermatogonial stem cells from young adult mice (71). This may result from direct actions on NF-κB, as rapamycin can act on IKKβ, leading to inhibition of its phosphorylation (111, 126). Further supporting these antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of rapamycin, pathway analysis revealed an upregulation of free radical scavenging genes and a downregulation of NF-κB signaling genes after rapamycin treatment in adult stem cells (71).

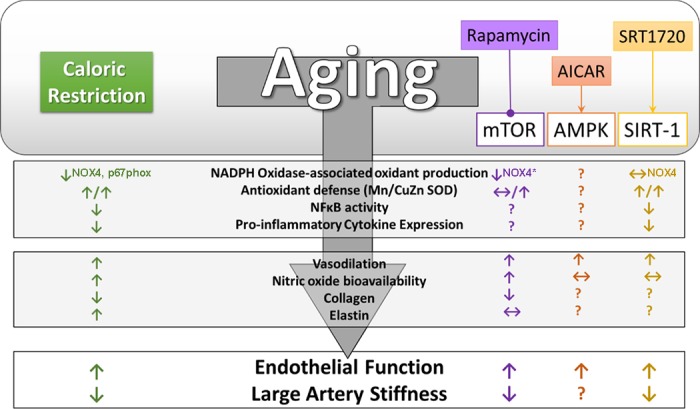

In arteries, age-associated increases in mTOR activation were reversed by 6 wk of dietary rapamycin treatment and led to improved EDD and decreased arterial stiffness in old mice (78). Similar to CR (37), rapamycin-mediated increases in EDD were associated with increased NO bioavailability (78), and improvements in arterial stiffness were associated with a decrease in both the collagen content and abundance of advanced glycation end products, indicative of reduced collagen cross-linking. However, unlike CR, there was no effect on elastin content after rapamycin treatment in old mice (78). Furthermore, like the vascular benefits of CR that appear to be mediated, at least in part, by a reduction in oxidant production by NADPH oxidase, there was a tendency for rapamycin treatment to reduce NADPH oxidase expression that was accompanied by reduced superoxide production and a reduced abundance of arterial nitrotyrosine. Despite similarities in the reduction of oxidant production between CR and rapamycin, the role of antioxidant defenses in mediating the vascular benefits appear to differ. For example, rapamycin treatment led to an increase in arterial expression of only the CuZn isoform of SOD (78), whereas CR increased all SOD isoforms (37) (Fig. 2). Thus, although rapamycin treatment recapitulates many of the vascular benefits afforded by CR, some differences in the underlying mechanisms between these interventions do exist and may limit implications for reducing CVD risk.

Fig. 2.

Targeting energy-sensing pathways as vascular caloric restriction mimetics. Although pharmacological inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) or activation of AMPK or sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) can lead to improvements in endothelial function and/or arterial stiffness in old mice, the mechanisms underlying these beneficial effects can be disparate from that of caloric restriction. Superscripts indicate the isoform/subunit of NADPH oxidase that was examined. Arrows indicate activation, while lines ending in a circle indicate inhibition. *Denotes a tendency for decrease.

AMPK

The nonspecific AMPK activator metformin has been used extensively in the setting of diabetes (7), and recently, it was the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for a clinical trial aimed at determining protective effects against a number of age-related diseases (7). In addition to the multiple beneficial effects of metformin on physiological function and disease, such as improving glucose tolerance and reducing oxidative stress and inflammation (88), direct AMPK activation by AICAR has also been shown to increase tissue antioxidant defenses, including increased skeletal muscle expression of MnSOD (16). In addition, there are multiple reports that AMPK activation can reduce inflammatory cytokines and that this is associated with blunted NF-κB signaling in a variety of tissues, including endothelial cells (58). In cultured endothelial cells, AMPK is a physiological activator of eNOS (95), suggesting that augmenting AMPK signaling may increase bioavailability of NO and enhance arterial function. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated improvements in endothelial function in type 1 and 2 diabetic rodents (70) and reductions in aortic PWV in premenopausal women with polycystic ovary syndrome (1) in response to enhanced AMPK activity after metformin treatment. Likewise, in aged mice, augmenting AMPK activation by AICAR leads to increased EDD (79). However, increases in EDD after AICAR resulted from increased reliance on EDHF and not an increase in NO bioavailability, as occurs with CR (37) (Fig. 2). Although the effect of AICAR on arterial stiffness in an aged mouse model is not known, accelerated high-fat diet-induced arterial stiffening and elevated collagen I expression were attenuated by AICAR in a mouse model deficient in the putative antiaging gene, klotho (85). This study suggests a beneficial effect of AMPK activation on arterial stiffening in a manner consistent with changes observed in aged mice after CR, although this requires further elucidation.

SIRT-1

Beneficial effects of SIRT-1 activation by the nonspecific activator resveratrol have been reported in the setting of metabolic (11) and neurodegenerative diseases (99). Recent studies have also examined the efficacy of resveratrol to attenuate age-related vascular dysfunction with promising results. Indeed, In addition to a direct vasodilatory effect on arteries (20), treatment with resveratrol can improve vasodilation in response to other agonists, such as ACh, and this is achieved by increasing NO bioavailability in a manner dependent on AMPK (20). Furthermore, as observed after CR, increased NO bioavailability after resveratrol treatment is associated with decreased superoxide and increased MnSOD expression in the superior thyroid artery of patients with hypertension (20). In addition, SIRT-1 activation by resveratrol (15) has anti-inflammatory effects both in vitro and in vivo. In cultured cells, treatment with resveratrol reduces TNF-α and H2O2-induced endothelial activation via reductions in NF-κB signaling (27). However, resveratrol is known to have direct antioxidant effects, which may explain its beneficial effects on arteries, independent of SIRT-1 activation per se (30).

Nevertheless, direct evidence for a protective role of SIRT-1 has come from genetic models, such that cardiac-specific SIRT-1 overexpression leads to cardio-protection against ROS and delays age-related cardiac phenotypes (61). The anti-inflammatory effects of SIRT-1 have been supported in a genetic model of SIRT-1 deletion. Indeed, macrophage-specific deletion SIRT-1 leads to hyperacetylation of NF-κB and increased transcription of proinflammatory cytokines (118). Taken together, studies using resveratrol and genetic models have inspired the development of more specific SIRT-1 activators as potential therapeutics to treat age-related diseases, including CVD. One such small molecule activator of SIRT-1, SRT1720, has recently been shown to increase life span (92) and improve metabolic function in aged mice (91). Activation of SIRT-1 by SRT1720, has also been demonstrated to have vascular benefits in aged mice (49). In vivo treatment with SRT1720 increased arterial SIRT-1 expression and activity and improved EDD in aged mice. However, unlike CR, this beneficial effect was mediated by an increased reliance on cyclooxygenase vasodilators (49) rather than NO or EDHF. Similar to CR, SRT1720 treatment led to a reduction in arterial superoxide production that was associated with increased expression of all SOD isoforms as well as catalase, but SIRT-1 activation by SRT1720 did not impact NADPH oxidase, as was found after CR and rapamycin treatment (25, 37, 49, 78, 110). Although the effect of mTOR inhibition or AMPK activation on age-associated arterial inflammation is not known, treatment with SRT1720 reversed age-associated NF-κB activation and reduced arterial cytokine expression (49) consistent with the effects of CR on arterial inflammation (Fig. 2). Thus, SIRT-1 may also represent a viable target to recapitulate at least some of the vascular benefits of CR.

Conclusions

Although targeting mTOR, AMPK, and SIRT-1 can lead to improvements in various aspects of the vascular aging phenotype, the magnitude of improvement and mechanisms by which these improvements are achieved vary depending on intervention. Although most of the studies to date focus on EDD and arterial stiffness as measures of vascular function and measures of oxidative stress and inflammation as the primary macromechanistic processes that underlie arterial dysfunction with advancing age, other vascular functions, including angiogenesis, barrier function, and thrombosis, are also likely to be critical to cardiovascular health with advancing age. It is important to note that NO plays a role in all of these processes (14, 32, 75, 108, 109), and as such, the inability of AICAR or SRT1720 treatments to reverse the age-associated reduction in NO bioavailability may limit the overall efficacy of these treatment strategies as true CR mimetics. Still, evidence to date suggests that while CR remains the most effective strategy to improve life span and good health, targeting of critical energy-sensing, and perhaps other life span-extending, pathways may provide vascular protection that warrants further exploration.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by Merit Review Award I01BX002151 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service and by the National Institute on Aging Award R01AG048366.

DISCLAIMERS

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute on Aging or the United States Government.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.R.G., J.C., and L.A.L. edited and revised manuscript; V.R.G., J.C., and L.A.L. approved final version of manuscript; L.A.L. prepared figures; L.A.L. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal N, Rice SP, Bolusani H, Luzio SD, Dunseath G, Ludgate M, Rees DA. Metformin reduces arterial stiffness and improves endothelial function in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 722–730, 2010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, Iyama T, Han YH, Takada J, Wakisaka M, Ibayashi S, Utsumi H, Iida M. Nox4 as the major catalytic component of an endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation 109: 227–233, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105680.92873.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angel K, Provan SA, Gulseth HL, Mowinckel P, Kvien TK, Atar D. Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists improve aortic stiffness in patients with inflammatory arthropathies: a controlled study. Hypertension 55: 333–338, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angulo J, Vallejo S, El Assar M, García-Septiem J, Sánchez-Ferrer CF, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Age-related differences in the effects of α and γ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subtype agonists on endothelial vasodilation in human microvessels. Exp Gerontol 47: 734–740, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE. If started early in life, metformin treatment increases life span and postpones tumors in female SHR mice. Aging (Albany NY) 3: 148–157, 2011. doi: 10.18632/aging.100273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barger JL, Vann JM, Cray NL, Pugh TD, Mastaloudis A, Hester SN, Wood SM, Newton MA, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Identification of tissue-specific transcriptional markers of caloric restriction in the mouse and their use to evaluate caloric restriction mimetics. Aging Cell 16: 750–760, 2017. doi: 10.1111/acel.12608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barzilai N, Crandall JP, Kritchevsky SB, Espeland MA. Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell Metab 23: 1060–1065, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belsky DW, Huffman KM, Pieper CF, Shalev I, Kraus WE. Change in the rate of biological aging in response to caloric restriction: CALERIE Biobank analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 73: 4–10, 2018. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135: e146–e603, 2017. [Erratum in Circulation 135: e646, 2017]. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyer AM, Zinkevich N, Miller B, Liu Y, Wittenburg AL, Mitchell M, Galdieri R, Sorokin A, Gutterman DD. Transition in the mechanism of flow-mediated dilation with aging and development of coronary artery disease. Basic Res Cardiol 112: 5, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0594-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt JK, Thomas S, Nanjan MJ. Resveratrol supplementation improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Res 32: 537–541, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boily G, Seifert EL, Bevilacqua L, He XH, Sabourin G, Estey C, Moffat C, Crawford S, Saliba S, Jardine K, Xuan J, Evans M, Harper ME, McBurney MW. SirT1 regulates energy metabolism and response to caloric restriction in mice. PLoS One 3: e1759, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bordone L, Cohen D, Robinson A, Motta MC, van Veen E, Czopik A, Steele AD, Crowe H, Marmor S, Luo J, Gu W, Guarente L. SIRT1 transgenic mice show phenotypes resembling calorie restriction. Aging Cell 6: 759–767, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borniquel S, Valle I, Cadenas S, Lamas S, Monsalve M. Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial oxidative stress protection via the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α. FASEB J 20: 1889–1891, 2006. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5189fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem 280: 17,187–17,195, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandauer J, Andersen MA, Kellezi H, Risis S, Frøsig C, Vienberg SG, Treebak JT. AMP-activated protein kinase controls exercise training- and AICAR-induced increases in SIRT3 and MnSOD. Front Physiol 6: 85, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braunersreuther V, Montecucco F, Ashri M, Pelli G, Galan K, Frias M, Burger F, Quinderé AL, Montessuit C, Krause KH, Mach F, Jaquet V. Role of NADPH oxidase isoforms NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 64: 99–107, 2013. [Erratum in J Mol Cell Cardiol 66: 189, 2013]. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown KA, Didion SP, Andresen JJ, Faraci FM. Effect of aging, MnSOD deficiency, and genetic background on endothelial function: evidence for MnSOD haploinsufficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1941–1946, 2007. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.146852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantó C, Jiang LQ, Deshmukh AS, Mataki C, Coste A, Lagouge M, Zierath JR, Auwerx J. Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for metabolic adaptation to fasting and exercise in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 11: 213–219, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrizzo A, Puca A, Damato A, Marino M, Franco E, Pompeo F, Traficante A, Civitillo F, Santini L, Trimarco V, Vecchione C. Resveratrol improves vascular function in patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia by modulating NO metabolism. Hypertension 62: 359–366, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.01009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 25: 138–145, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, Wall NR, Hekking B, Kessler B, Howitz KT, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305: 390–392, 2004. doi: 10.1126/science.1099196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 325: 201–204, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper LL, Rong J, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vita JA, Hamburg NM, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF. Components of hemodynamic load and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 131: 354–361, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Csiszar A, Gautam T, Sosnowska D, Tarantini S, Banki E, Tucsek Z, Toth P, Losonczy G, Koller A, Reglodi D, Giles CB, Wren JD, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z. Caloric restriction confers persistent antioxidative, proangiogenic, and anti-inflammatory effects and promotes antiaging miRNA expression profile in cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H292–H306, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00307.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Jimenez R, Pinto JT, Ballabh P, Losonczy G, Pearson KJ, de Cabo R, Ungvari Z. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory vasoprotective effects of caloric restriction in aging: role of circulating factors and SIRT1. Mech Ageing Dev 130: 518–527, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Podlutsky A, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Zhang C, Mukhopadhyay P, Pacher P, Hu F, de Cabo R, Ballabh P, Ungvari Z. Vasoprotective effects of resveratrol and SIRT1: attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory phenotypic alterations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2721–H2735, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00235.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Luz PL, Tanaka L, Brum PC, Dourado PM, Favarato D, Krieger JE, Laurindo FR. Red wine and equivalent oral pharmacological doses of resveratrol delay vascular aging but do not extend life span in rats. Atherosclerosis 224: 136–142, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das A, Durrant D, Koka S, Salloum FN, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition with rapamycin improves cardiac function in type 2 diabetic mice: potential role of attenuated oxidative stress and altered contractile protein expression. J Biol Chem 289: 4145–4160, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de la Lastra CA, Villegas I. Resveratrol as an antioxidant and pro-oxidant agent: mechanisms and clinical implications. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 1156–1160, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BST0351156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhingra R, Vasan RS. Age as a risk factor. Med Clin North Am 96: 87–91, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Lorenzo A, Lin MI, Murata T, Landskroner-Eiger S, Schleicher M, Kothiya M, Iwakiri Y, Yu J, Huang PL, Sessa WC. eNOS-derived nitric oxide regulates endothelial barrier function through VE-cadherin and Rho GTPases. J Cell Sci 126: 5541–5552, 2013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Faraci FM. Heterozygous CuZn superoxide dismutase deficiency produces a vascular phenotype with aging. Hypertension 48: 1072–1079, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000247302.20559.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donato AJ, Black AD, Jablonski KL, Gano LB, Seals DR. Aging is associated with greater nuclear NF κB, reduced I κBα, and increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines in vascular endothelial cells of healthy humans. Aging Cell 7: 805–812, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, Seals DR. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-κB. Circ Res 100: 1659–1666, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000269183.13937.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donato AJ, Magerko KA, Lawson BR, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. SIRT-1 and vascular endothelial dysfunction with ageing in mice and humans. J Physiol 589: 4545–4554, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.211219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donato AJ, Walker AE, Magerko KA, Bramwell RC, Black AD, Henson GD, Lawson BR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. Life-long caloric restriction reduces oxidative stress and preserves nitric oxide bioavailability and function in arteries of old mice. Aging Cell 12: 772–783, 2013. doi: 10.1111/acel.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drummond GR, Cai H, Davis ME, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res 86: 347–354, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.86.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durand MJ, Gutterman DD. Diversity in mechanisms of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in health and disease. Microcirculation 20: 239–247, 2013. doi: 10.1111/micc.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durrant JR, Seals DR, Connell ML, Russell MJ, Lawson BR, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Voluntary wheel running restores endothelial function in conduit arteries of old mice: direct evidence for reduced oxidative stress, increased superoxide dismutase activity and down-regulation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol 587: 3271–3285, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards AG, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA, Gioscia RA, Seals DR, Moore RL. Life-long caloric restriction elicits pronounced protection of the aged myocardium: a role for AMPK. Mech Ageing Dev 131: 739–742, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eskurza I, Monahan K, Robinson J, Seals D. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid augmentation on flow-mediated dilation with physically active and sedentary aging. J Physiol 556: 215–224, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleenor BS, Eng JS, Sindler AL, Pham BT, Kloor JD, Seals DR. Superoxide signaling in perivascular adipose tissue promotes age-related artery stiffness. Aging Cell 13: 576–578, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acel.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleg JL, Strait J. Age-associated changes in cardiovascular structure and function: a fertile milieu for future disease. Heart Fail Rev 17: 545–554, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10741-011-9270-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6659–6663, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freedman JE, Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide and its relationship to thrombotic disorders. J Thromb Haemost 1: 1183–1188, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 1583–1606, 2011. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaballa MA, Jacob CT, Raya TE, Liu J, Simon B, Goldman S. Large artery remodeling during aging: biaxial passive and active stiffness. Hypertension 32: 437–443, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.32.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gano LB, Donato AJ, Pasha HM, Hearon CM Jr, Sindler AL, Seals DR. The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 reverses vascular endothelial dysfunction, excessive superoxide production, and inflammation with aging in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1754–H1763, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghosh HS, McBurney M, Robbins PD. SIRT1 negatively regulates the mammalian target of rapamycin. PLoS One 5: e9199, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez AA, Kumar R, Mulligan JD, Davis AJ, Weindruch R, Saupe KW. Metabolic adaptations to fasting and chronic caloric restriction in heart, muscle, and liver do not include changes in AMPK activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1032–E1037, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00172.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greer EL, Dowlatshahi D, Banko MR, Villen J, Hoang K, Blanchard D, Gygi SP, Brunet A. An AMPK-FOXO pathway mediates longevity induced by a novel method of dietary restriction in C. elegans. Curr Biol 17: 1646–1656, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell 30: 214–226, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han L, Zhou R, Niu J, McNutt MA, Wang P, Tong T. SIRT1 is regulated by a PPARγ-SIRT1 negative feedback loop associated with senescence. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 7458–7471, 2010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardie DG, Hawley SA, Scott JW. AMP-activated protein kinase—development of the energy sensor concept. J Physiol 574: 7–15, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, Pahor M, Javors MA, Fernandez E, Miller RA. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460: 392–395, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa Y, Saito T, Ogihara T, Ishigaki Y, Yamada T, Imai J, Uno K, Gao J, Kaneko K, Shimosawa T, Asano T, Fujita T, Oka Y, Katagiri H. Blockade of the nuclear factor-κB pathway in the endothelium prevents insulin resistance and prolongs life spans. Circulation 125: 1122–1133, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.054346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hattori Y, Nakano Y, Hattori S, Tomizawa A, Inukai K, Kasai K. High molecular weight adiponectin activates AMPK and suppresses cytokine-induced NF-κB activation in vascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett 582: 1719–1724, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hattori Y, Suzuki K, Hattori S, Kasai K. Metformin inhibits cytokine-induced nuclear factor κB activation via AMP-activated protein kinase activation in vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension 47: 1183–1188, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000221429.94591.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho JT, Keogh JB, Bornstein SR, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Lewis JG, Clifton PM, Torpy DJ. Moderate weight loss reduces renin and aldosterone but does not influence basal or stimulated pituitary-adrenal axis function. Horm Metab Res 39: 694–699, 2007. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsu CP, Odewale I, Alcendor RR, Sadoshima J. Sirt1 protects the heart from aging and stress. Biol Chem 389: 221–231, 2008. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huynh J, Nishimura N, Rana K, Peloquin JM, Califano JP, Montague CR, King MR, Schaffer CB, Reinhart-King CA. Age-related intimal stiffening enhances endothelial permeability and leukocyte transmigration. Sci Transl Med 3: 112ra122, 2011. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jablonski KL, Donato AJ, Fleenor BS, Nowlan MJ, Walker AE, Kaplon RE, Ballak DB, Seals DR. Reduced large elastic artery stiffness with regular aerobic exercise in middle-aged and older adults: potential role of suppressed nuclear factor κB signalling. J Hypertens 33: 2477–2482, 2015. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang J, Jiang J, Zuo Y, Gu Z. Rapamycin protects the mitochondria against oxidative stress and apoptosis in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Med 31: 825–832, 2013. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalani R, Judge S, Carter C, Pahor M, Leeuwenburgh C. Effects of caloric restriction and exercise on age-related, chronic inflammation assessed by C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61: 211–217, 2006. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang LS, Chen B, Reyes RA, Leblanc AJ, Teng B, Mustafa SJ, Muller-Delp JM. Aging and estrogen alter endothelial reactivity to reactive oxygen species in coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2105–H2115, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kapahi P, Chen D, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Li PW, Thomas EL, Kockel L. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab 11: 453–465, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol 14: 885–890, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karin M, Delhase M. The I κB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB: key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin Immunol 12: 85–98, 2000. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katakam PV, Ujhelyi MR, Hoenig M, Miller AW. Metformin improves vascular function in insulin-resistant rats. Hypertension 35: 108–112, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kofman AE, McGraw MR, Payne CJ. Rapamycin increases oxidative stress response gene expression in adult stem cells. Aging (Albany NY) 4: 279–289, 2012. doi: 10.18632/aging.100451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kohn JC, Zhou DW, Bordeleau F, Zhou AL, Mason BN, Mitchell MJ, King MR, Reinhart-King CA. Cooperative effects of matrix stiffness and fluid shear stress on endothelial cell behavior. Biophys J 108: 471–478, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lakatta EG. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part III: cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation 107: 490–497, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000048894.99865.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 107: 139–146, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laroux FS, Lefer DJ, Kawachi S, Scalia R, Cockrell AS, Gray L, Van der Heyde H, Hoffman JM, Grisham MB. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of acute and chronic inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2: 391–396, 2000. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lesniewski LA, Connell ML, Durrant JR, Folian BJ, Anderson MC, Donato AJ, Seals DR. B6D2F1 Mice are a suitable model of oxidative stress-mediated impaired endothelium-dependent dilation with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64A: 9–20, 2009. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lesniewski LA, Durrant JR, Connell ML, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Seals DR. Salicylate treatment improves age-associated vascular endothelial dysfunction: potential role of nuclear factor κB and Forkhead Box O phosphorylation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66A: 409–418, 2011. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lesniewski LA, Seals DR, Walker AE, Henson GD, Blimline MW, Trott DW, Bosshardt GC, LaRocca TJ, Lawson BR, Zigler MC, Donato AJ. Dietary rapamycin supplementation reverses age-related vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress, while modulating nutrient-sensing, cell cycle, and senescence pathways. Aging Cell 16: 17–26, 2017. doi: 10.1111/acel.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lesniewski LA, Zigler MC, Durrant JR, Donato AJ, Seals DR. Sustained activation of AMPK ameliorates age-associated vascular endothelial dysfunction via a nitric oxide-independent mechanism. Mech Ageing Dev 133: 368–371, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leto TL, Morand S, Hurt D, Ueyama T. Targeting and regulation of reactive oxygen species generation by Nox family NADPH oxidases. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2607–2619, 2009. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liao CY, Rikke BA, Johnson TE, Diaz V, Nelson JF. Genetic variation in the murine lifespan response to dietary restriction: from life extension to life shortening. Aging Cell 9: 92–95, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liao CY, Rikke BA, Johnson TE, Gelfond JA, Diaz V, Nelson JF. Fat maintenance is a predictor of the murine lifespan response to dietary restriction. Aging Cell 10: 629–639, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lieberthal W, Levine JS. The role of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2493–2502, 2009. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin SJ, Kaeberlein M, Andalis AA, Sturtz LA, Defossez PA, Culotta VC, Fink GR, Guarente L. Calorie restriction extends Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan by increasing respiration. Nature 418: 344–348, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nature00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin Y, Chen J, Sun Z. Antiaging gene Klotho deficiency promoted high-fat diet-induced arterial stiffening via inactivation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Hypertension 67: 564–573, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mahmud A, Feely J. Arterial stiffness and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 5: 102–108, 2004. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2004.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Manea A, Manea SA, Gafencu AV, Raicu M. Regulation of NADPH oxidase subunit p22(phox) by NF-κB in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Arch Physiol Biochem 113: 163–172, 2007. doi: 10.1080/13813450701531235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martin-Montalvo A, Mercken EM, Mitchell SJ, Palacios HH, Mote PL, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Gomes AP, Ward TM, Minor RK, Blouin MJ, Schwab M, Pollak M, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Becker KG, Bohr VA, Ingram DK, Sinclair DA, Wolf NS, Spindler SR, Bernier M, de Cabo R. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat Commun 4: 2192, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martínez-Cisuelo V, Gómez J, García-Junceda I, Naudí A, Cabré R, Mota-Martorell N, López-Torres M, González-Sánchez M, Pamplona R, Barja G. Rapamycin reverses age-related increases in mitochondrial ROS production at complex I, oxidative stress, accumulation of mtDNA fragments inside nuclear DNA, and lipofuscin level, and increases autophagy, in the liver of middle-aged mice. Exp Gerontol 83: 130–138, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Masternak MM, Bartke A. PPARs in calorie restricted and genetically long-lived mice. PPAR Res 2007: 28436, 2007. doi: 10.1155/2007/28436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, Carney DP, Smith JJ, Gagne DJ, Jin L, Boss O, Perni RB, Vu CB, Bemis JE, Xie R, Disch JS, Ng PY, Nunes JJ, Lynch AV, Yang H, Galonek H, Israelian K, Choy W, Iffland A, Lavu S, Medvedik O, Sinclair DA, Olefsky JM, Jirousek MR, Elliott PJ, Westphal CH. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature 450: 712–716, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Minor RK, Baur JA, Gomes AP, Ward TM, Csiszar A, Mercken EM, Abdelmohsen K, Shin YK, Canto C, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Krawczyk M, Irusta PM, Martín-Montalvo A, Hubbard BP, Zhang Y, Lehrmann E, White AA, Price NL, Swindell WR, Pearson KJ, Becker KG, Bohr VA, Gorospe M, Egan JM, Talan MI, Auwerx J, Westphal CH, Ellis JL, Ungvari Z, Vlasuk GP, Elliott PJ, Sinclair DA, de Cabo R. SRT1720 improves survival and healthspan of obese mice. Sci Rep 1: 70, 2011. [Erratum in Sci Rep 3: 1131, 2013]. doi: 10.1038/srep00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 43: 109–142, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moreau KL, Gavin KM, Plum AE, Seals DR. Ascorbic acid selectively improves large elastic artery compliance in postmenopausal women. Hypertension 45: 1107–1112, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165678.63373.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morrow VA, Foufelle F, Connell JM, Petrie JR, Gould GW, Salt IP. Direct activation of AMP-activated protein kinase stimulates nitric-oxide synthesis in human aortic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 278: 31,629–31,639, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Most J, Gilmore LA, Smith SR, Han H, Ravussin E, Redman LM. Significant improvement in cardiometabolic health in healthy non-obese individuals during caloric restriction-induced weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 314: E396–E405, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00261.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, Kearney M, Chen D, Symes JF, Fishman MC, Huang PL, Isner JM. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest 101: 2567–2578, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Neves MF, Cunha AR, Cunha MR, Gismondi RA, Oigman W. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and its new components in arterial stiffness and vascular aging. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 25: 137–145, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s40292-018-0252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pallàs M, Casadesús G, Smith MA, Coto-Montes A, Pelegri C, Vilaplana J, Camins A. Resveratrol and neurodegenerative diseases: activation of SIRT1 as the potential pathway towards neuroprotection. Curr Neurovasc Res 6: 70–81, 2009. doi: 10.2174/156720209787466019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, Peshkin L, Price NL, Labinskyy N, Swindell WR, Kamara D, Minor RK, Perez E, Jamieson HA, Zhang Y, Dunn SR, Sharma K, Pleshko N, Woollett LA, Csiszar A, Ikeno Y, Le Couteur D, Elliott PJ, Becker KG, Navas P, Ingram DK, Wolf NS, Ungvari Z, Sinclair DA, de Cabo R. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab 8: 157–168, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pierce GL, Lesniewski LA, Lawson BR, Beske SD, Seals DR. Nuclear factor-κB activation contributes to vascular endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress in overweight/obese middle-aged and older humans. Circulation 119: 1284–1292, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pillarisetti S. A review of Sirt1 and Sirt1 modulators in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Recent Patents Cardiovasc Drug Discov 3: 156–164, 2008. doi: 10.2174/157489008786263989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Quinn U, Tomlinson LA, Cockcroft JR. Arterial stiffness. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis 1: 1–8, 2012. doi: 10.1258/cvd.2012.012024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rahman S, Islam R. Mammalian Sirt1: insights on its biological functions. Cell Commun Signal 9: 11, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rajendran P, Rengarajan T, Thangavel J, Nishigaki Y, Sakthisekaran D, Sethi G, Nishigaki I. The vascular endothelium and human diseases. Int J Biol Sci 9: 1057–1069, 2013. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ravussin E, Redman LM, Rochon J, Das SK, Fontana L, Kraus WE, Romashkan S, Williamson DA, Meydani SN, Villareal DT, Smith SR, Stein RI, Scott TM, Stewart TM, Saltzman E, Klein S, Bhapkar M, Martin CK, Gilhooly CH, Holloszy JO, Hadley EC, Roberts SB; CALERIE Study Group . A 2-year randomized controlled trial of human caloric restriction: feasibility and effects on predictors of health span and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70: 1097–1104, 2015. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Raymond E, Alexandre J, Faivre S, Vera K, Materman E, Boni J, Leister C, Korth-Bradley J, Hanauske A, Armand JP. Safety and pharmacokinetics of escalated doses of weekly intravenous infusion of CCI-779, a novel mTOR inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 2336–2347, 2004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reichenbach G, Momi S, Gresele P. Nitric oxide and its antithrombotic action in the cardiovascular system. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 5: 65–74, 2005. doi: 10.2174/1568006053005047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ridnour LA, Isenberg JS, Espey MG, Thomas DD, Roberts DD, Wink DA. Nitric oxide regulates angiogenesis through a functional switch involving thrombospondin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 13147–13152, 2005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502979102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rippe C, Lesniewski L, Connell M, LaRocca T, Donato A, Seals D. Short-term calorie restriction reverses vascular endothelial dysfunction in old mice by increasing nitric oxide and reducing oxidative stress. Aging Cell 9: 304–312, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Romano MF, Avellino R, Petrella A, Bisogni R, Romano S, Venuta S. Rapamycin inhibits doxorubicin-induced NF-κB/Rel nuclear activity and enhances the apoptosis of melanoma cells. Eur J Cancer 40: 2829–2836, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Roth GS, Lesnikov V, Lesnikov M, Ingram DK, Lane MA. Dietary caloric restriction prevents the age-related decline in plasma melatonin levels of rhesus monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 3292–3295, 2001. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Satoh K, Godo S, Saito H, Enkhjargal B, Shimokawa H. Dual roles of vascular-derived reactive oxygen species—with a special reference to hydrogen peroxide and cyclophilin A. J Mol Cell Cardiol 73: 50–56, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schlatmann TJ, Becker AE. Histologic changes in the normal aging aorta: implications for dissecting aortic aneurysm. Am J Cardiol 39: 13–20, 1977. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(77)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schleicher ED, Wagner E, Nerlich AG. Increased accumulation of the glycoxidation product N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine in human tissues in diabetes and aging. J Clin Invest 99: 457–468, 1997. doi: 10.1172/JCI119180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schnabel R, Larson MG, Dupuis J, Lunetta KL, Lipinska I, Meigs JB, Yin X, Rong J, Vita JA, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Keaney JF Jr, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF, Benjamin EJ. Relations of inflammatory biomarkers and common genetic variants with arterial stiffness and wave reflection. Hypertension 51: 1651–1657, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schreck R, Albermann K, Baeuerle PA. Nuclear factor κB: an oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor of eukaryotic cells (a review). Free Radic Res Commun 17: 221–237, 1992. doi: 10.3109/10715769209079515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schug TT, Xu Q, Gao H, Peres-da-Silva A, Draper DW, Fessler MB, Purushotham A, Li X. Myeloid deletion of SIRT1 induces inflammatory signaling in response to environmental stress. Mol Cell Biol 30: 4712–4721, 2010. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00657-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Selman C, Tullet JM, Wieser D, Irvine E, Lingard SJ, Choudhury AI, Claret M, Al-Qassab H, Carmignac D, Ramadani F, Woods A, Robinson IC, Schuster E, Batterham RL, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Carling D, Okkenhaug K, Thornton JM, Partridge L, Gems D, Withers DJ. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science 326: 140–144, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Fórró L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J 406: 105–114, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sharma N, Castorena CM, Cartee GD. Tissue-specific responses of IGF-1/insulin and mTOR signaling in calorie restricted rats. PLoS One 7: e38835, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sharp ZD, Strong R. The role of mTOR signaling in controlling mammalian life span: what a fungicide teaches us about longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65A: 580–589, 2010. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Soesanto W, Lin HY, Hu E, Lefler S, Litwin SE, Sena S, Abel ED, Symons JD, Jalili T. Mammalian target of rapamycin is a critical regulator of cardiac hypertrophy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 54: 1321–1327, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Soucy KG, Ryoo S, Benjo A, Lim HK, Gupta G, Sohi JS, Elser J, Aon MA, Nyhan D, Shoukas AA, Berkowitz DE. Impaired shear stress-induced nitric oxide production through decreased NOS phosphorylation contributes to age-related vascular stiffness. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 1751–1759, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00138.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Spaulding CC, Walford RL, Effros RB. Calorie restriction inhibits the age-related dysregulation of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in C3B10RF1 mice. Mech Ageing Dev 93: 87–94, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(96)01824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tuñón MJ, Sánchez-Campos S, Gutiérrez B, Culebras JM, González-Gallego J. Effects of FK506 and rapamycin on generation of reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide production and nuclear factor-κB activation in rat hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 66: 439–445, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vila E, Salaices M. Cytokines and vascular reactivity in resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1016–H1021, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00779.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Vita JA, Keaney JF Jr, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Massaro JM, Lipinska I, Lehman BT, Fan S, Osypiuk E, Wilson PW, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF, Benjamin EJ. Brachial artery vasodilator function and systemic inflammation in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation 110: 3604–3609, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148821.97162.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Walford G, Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide in vascular biology. J Thromb Haemost 1: 2112–2118, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Walker AE, Henson GD, Reihl KD, Nielson EI, Morgan RG, Lesniewski LA, Donato AJ. Beneficial effects of lifelong caloric restriction on endothelial function are greater in conduit arteries compared to cerebral resistance arteries. Age (Dordr) 36: 559–569, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9585-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang M, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: a journey into subclinical arterial disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 201–207, 2010. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283361c0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Watanabe R, Wei L, Huang J. mTOR signaling, function, novel inhibitors, and therapeutic targets. J Nucl Med 52: 497–500, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Weber T, Wassertheurer S, Rammer M, Haiden A, Hametner B, Eber B. Wave reflections, assessed with a novel method for pulse wave separation, are associated with end-organ damage and clinical outcomes. Hypertension 60: 534–541, 2012. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]