Abstract

Antigen presenting cells (APCs) are essential for the orchestration of anti-tumor T cell responses. Batf3-lineage CD8α+ and CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs), in particular, are required for the spontaneous initiation of CD8+ T cell priming against solid tumors. In contrast, little is known about the APCs that regulate CD8+ T cell responses against hematological malignancies. Using an unbiased approach, we aimed to characterize the APCs responsible for regulating CD8+ T cell responses in a syngeneic murine leukemia model. We show with single cell resolution that CD8α+ DCs alone acquire and cross-present leukemia antigens in vivo, culminating in the induction of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the mere acquisition of leukemia cell cargo is associated with a unique transcriptional program that may be important in regulating tolerogenic CD8α+ DC functions in mice with leukemia. Finally, we show that systemic CD8α+ DC activation with a TLR3 agonist completely prevents their ability to generate leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance in vivo, resulting instead in the induction of potent anti-leukemia T cell immunity and prolonged survival of leukemia-bearing mice. Together, our data reveal that Batf3-lineage DCs imprint disparate CD8+ T cell fates in hosts with solid tumors versus systemic leukemia.

Keywords: CD8α+ dendritic cells, T cell tolerance, acute leukemia, Batf3

Introduction

Endogenous tumor-specific T cell responses are generated spontaneously in a fraction of human cancers. In pre-clinical models, anti-tumor T cell priming requires sensing of tumor-derived danger signals and type I interferon (IFN) by myeloid cells that reside in the tumor environment (1–3). In recent years, characterization of the cell types that acquire and present tumor antigens in the solid cancer context has been an area of intensive investigation. Although a variety of cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), are capable of engulfing malignant cells (4), a relatively rare subset of migratory CD103+ DCs, activated following exposure to tumor-derived factors, traffic to tumor-draining lymph nodes, where they present captured tumor antigens to mediate the activation of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells (5–7). CD103+ DCs require basic leucine zipper transcription factor ATF-like3 (Batf3) for their proper development, and are closely related to lymph node-resident CD8α+ DCs (8). Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that CD141+ DCs, the human counterpart to mouse CD103+ DCs, are also involved in generating anti-tumor T cell immunity in cancer patients (6, 9). Together, these observations reveal a dominant role for migratory Batf3-lineage DCs in CD8+ T cell priming against solid cancers in mouse and man.

Acute leukemias, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), are systemic malignancies with unique growth rates and distribution patterns compared to cancers of non-hematopoietic origin. Typically associated with few somatic mutations (10), the neo-antigen landscape of acute leukemias appears sparse, suggesting that the inherent immunogenicity of these cancers is lower than that of most solid tumors. However, CD8+ T cells specific for bona fide leukemia-associated antigens (LAA) have been identified in the peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with AML and ALL (11, 12), indicating that such antigens are encountered by T cells in vivo, either through direct presentation by leukemia cells, or following cross-presentation by professional antigen presenting cells (APCs). Furthermore, DC and peptide-based vaccine approaches can further expand leukemia-specific T cells in patients, and are beginning to demonstrate early evidence of efficacy in the clinic (13, 14), suggesting that immunotherapeutic approaches may be effective in select leukemia patients. However, a more complete understanding of cellular and molecular regulation of immunity and immune tolerance in hematological malignancies will be critical in order to catalyze the development of new and more effective immunotherapies for patients.

In contrast to solid tumors, the APC populations that regulate endogenous anti-leukemia CD8+ T cell responses have not been well-defined, and are challenging to identify and validate in leukemia patients. In order to close this gap in knowledge, we undertook an unbiased approach to identify APCs capable of acquiring and presenting leukemia antigens to CD8+ T cells in vivo in the setting of a syngeneic murine leukemia model. We demonstrate with single cell resolution that antigens from circulating leukemia cells are primarily captured and cross-presented by splenic CD8α+ DCs, which mediate leukemia antigen recognition by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo. Furthermore, we show that cross-presentation of leukemia antigens by CD8α+ DCs results in the induction of CD8+ T cell tolerance, which can be prevented by systemic CD8α+ DC activation. Lastly, we find that the mere acquisition of leukemia cell cargo is associated with a unique transcriptional program in CD8α+ DCs, which may be important in promoting their tolerogenic phenotype. In conclusion, our work sheds new light on the unique regulation of CD8+ T cell responses by DCs in leukemia-bearing hosts.

Materials and Methods

Mice and cell lines

6-12 week-old C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Taconic laboratories (Germantown, NY). 2C T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice have been described previously (15), and were bred in our facility. Batf3−/−, Tap1−/−, and Il12byfp mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and were bred in our facility. For experiments involving Batf3−/− mice, Batf3+/+ littermates were used as the wild-type control. H2-Kb−/− mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences. Clec9agfp/gfp mice were provided by Dr. Caetano Reis e Sousa (The Francis Crick Institute), and were bred in our facility. Animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment and used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee according to NIH guidelines. The C1498 leukemia cell line was purchased from ATCC. The C1498.SIY cell line was generated in our laboratory as previously described (16). The H2-Kb−/− C1498.SIY cell line was generated using CRISPR/Cas9. The first exon of H2-Kb was targeted (sequence AACAGCAGGAGCAGCGTGCACGG). A guide RNA (gRNA) was generated using the following primers (forward - CACCGAACAGCAGGAGCAGCGTGCA; reverse - AAACTGCACGCTGCTCCTGCTGTTC), and was sub-cloned into the Lenti_v2 vector, which also contains the cDNA encoding for Cas9. After transduction, C1498.SIY cells were selected in culture with puromycin for 1 week. Next, C1498.SIY cells were stained with a fluorescently-labeled anti-H2-Kb antibody, and H2-Kb-negative cells were sorted by FACS to 100% purity. The Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia (FBL) cell line was a gift from Dr. Ryan Teague (St. Louis University) (17).

All cell lines used were monitored for mycoplasma contamination using Venor GeM Mycoplasma PCR-Based Detection Kit from Sigma.

DC isolation and Flow Cytometry

Lymphoid organs were injected with 5ml of 1mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma) and 20μg/ml DNAse I (Roche), incubated at 37° C for 30 minutes, and passed through a 70μm filter. Red blood cells were lysed, and Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibodies. Samples were stained with the following directly-conjugated antibodies (BD Bioscience, eBioscience or Biolegend): CD11c (clone:HL3), Thy1.2 (53-2.1), CD205 (205yelka), DNGR-1 (10B4), CD11b (M1/70), Siglec H (551), TCRβ (H57-597), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53-6.7), CD69 (H1-2F3), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), H-2Kb (AF6-88.5), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and B220 (RA3-6B2). CD3ε (145-2C11) and CD19 (eBio1D3) biotinylated antibodies were used followed by secondary streptavidin staining to eliminate T and B cells from cytometric analysis of DC populations. TLR3 (11F8) expression was analyzed via intracellular staining after fixation and permeabilization (eBioscience). Dead cells were excluded using fixable viability dyes (Invitrogen). Samples were run on LSRII or LSRFortessa (BD Bioscience) cytometers, and analysis was performed using FlowJo (Treestar). ImageStream samples were run on the ImageStreamX instrument (Amnis) and analyzed with IDEAS software (Amnis).

In vivo phagocytosis and cross-presentation assays

C1498 cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, washed three times with PBS, and injected IV through the lateral tail vein. 1-24 hours later, organs were harvested, collagenase digested, and stained with the indicated antibodies in preparation for flow cytometry. For cross-presentation assays, splenic DC populations were FACS-purified three hours after IV injection of 4 × 106 C1498 or C1498.SIY cells. Sorted DC populations were cultured (1:1 or 1:2) with purified CD8+ CTV-labeled 2C T cells for 65-72 hours in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2-mercaptoethanol, essential amino acids, and antibiotics (complete RPMI). Subsequently, the CTV dilution of cultured 2C T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Six days following C1498.SIY cell challenge, 5 × 106 spleen cells isolated from leukemia-bearing animals were cultured in the presence or absence of 500 nM SIY peptide, or with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for five hours. GolgiPlug (BD bioscience) was added for the final four hours (final concentration 1μg/ml). Cells were then stained with fluorescently-labeled antibodies against Thy1.2 or TCRβ and CD8α prior to fixation and permeabilization (eBioscience), and subsequent staining with an anti-IFN-γ antibody was performed.

Adoptive T cell transfer

CD8+ T cells were isolated from 2C TCR transgenic mice via magnetic separation (Miltenyi), were CTV-labeled, and 1 × 106 cells were inoculated IV into recipient mice. The next day, mice received 1 × 106 C1498.SIY cells IV or SC. Six days later, spleens were harvested and stained with antibodies against Thy1.2, CD8α, and an antibody that specifically recognizes the 2C TCR (1B2). In some experiments, 2C T cells expressing the congenic marker CD45.1 were used and transferred 2C T cells were subsequently identified as 1B2+CD45.1+ cells.

IFA/SIY Vaccination

5 × 106 C1498.SIY cells were inoculated IV into groups of C57BL/6 or Batf3−/− mice. Six days later, leukemia-bearing or naïve mice received a SC vaccination with IFA (Sigma) or SIY peptide (25 μg) emulsified in IFA (18). Five days later, vaccine-draining lymph node cells were stained with an SIY/Kb pentamer (Proimmune), along with anti-Thy1.2 and anti-CD8α antibodies, and the frequencies of SIY-reactive CD8+ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry.

IFN-γ ELISPOT

C57BL/6 mice were challenged with 106 C1498.SIY cells on day 0, and received two 100 μg doses of poly(I:C) or PBS intra-peritoneal (IP). Six days following leukemia challenge, spleen cells from individual mice were isolated and 106 cells were re-stimulated with media alone or with SIY peptide (100 nM) in triplicate overnight using an IFN-γ ELISPOT kit (BD Bioscience) as previously described (19). ELISPOT plates were read using an ImmunoSpot Series 3 Analyzer, and data were analyzed with ImmunoSpot software.

Survival experiments

C1498 or C1498.SIY cells (106) were inoculated IV into C57BL/6 or Batf3−/− mice. On days 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12, mice received 100 μg of Poly(I:C) (Sigma) or PBS IP. Survival was monitored for at least 50 days.

RNA sequencing and data analysis

Six hours after IV inoculation of 4 × 106 CTV-labeled C1498 cells into 2 groups of 10 C57BL/6 mice, spleens were harvested, and CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs were isolated by FACS, and RNA was isolated. RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform. The quality of raw reads was accessed by FastQC (v0.11.2) (20). All reads were mapped to the mouse genome assembly (UCSC build mm10) using TopHat2 (v2.1.0) (21). Alignment metrics were collected using Picard tools (v2.0.1) and RSeQC (v2.6) (22). Transcripts were assembled from the aligned reads using Cufflinks (v2.2.1) and combined with known gene annotation (23). The expression level of transcripts was quantified using FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) - based, and read count-based methods. Transcript expression was normalized across samples. Differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) and isoforms were detected using Cuffquant-Cuffnorm-Cuffdif suite (FPKM-based method, v2.2.1) and Rsubread::featureCounts (v1.22.3) (24), DESeq (v1.21.1) (25), DESeq2 (v1.10.1) (26), and edgeR (v3.12.0) (read count-based method) (27). Transcripts were further filtered by fold change ≥ 6 and false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p-value < 0.001. Genes detected by at least 2 methods were selected to create the list of DEGs. DAVID (28), Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity® Systems), and REVIGO (29) were used to identify functional categories and pathways that were significantly altered under the given condition.

Statistical analysis

Grouped data were analyzed via 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests. Survival differences were compared using a log-rank test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

CD8α+ DCs selectively acquire leukemia cell material in vivo

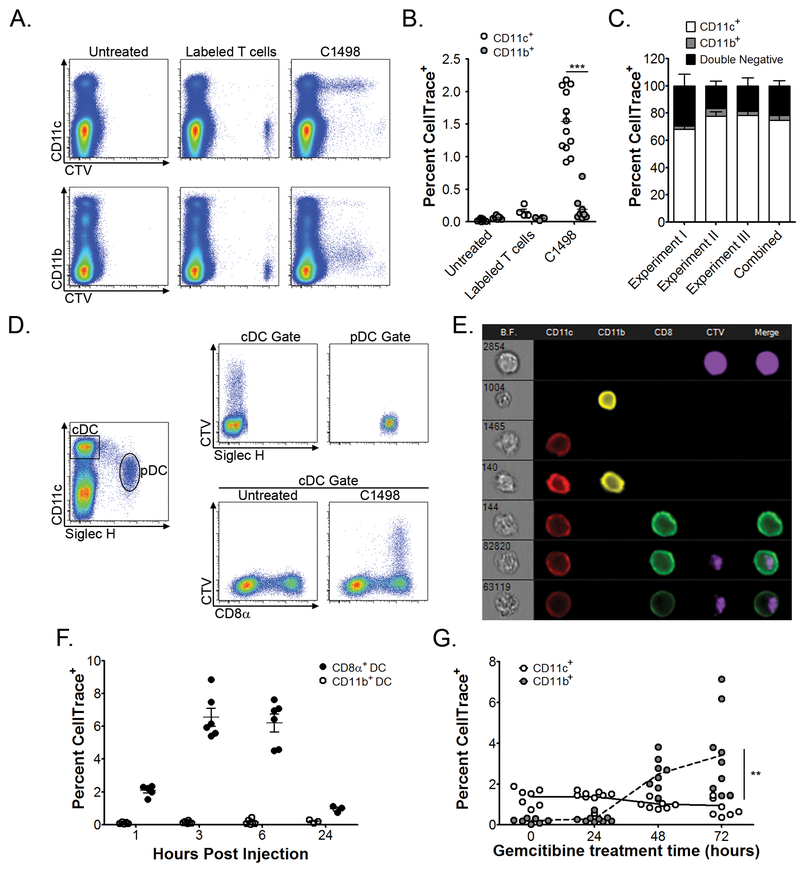

In order to determine whether cargo from circulating leukemia cells could be identified within host APCs, and if so, to characterize the APC subsets that were capable of acquiring leukemia-derived material in vivo, syngeneic C1498 leukemia cells were labeled with a fluorescent protein-binding dye, CellTrace Violet (CTV), and were inoculated intravenously (IV) into C57BL/6 mice. Flow cytometry was then performed to assess for the presence of leukemia cell-derived CTV fluorescence within known phagocytic cell populations. Surprisingly, following inoculation of labeled C1498 leukemia cells, CTV fluorescence was identified almost exclusively within splenic CD11c+ cells (DCs) (Figure 1A and 1B). For example, when the total population of splenic CTV+ cells was analyzed, ~75% were found to be CD11c+, while only ~5% were CD11b+. The remaining ~20% of CTV+ cells likely represented non-engulfed leukemia cells (Figure 1C). A control group of animals received an inoculation of CTV-labeled, syngeneic CD4+ T cells, but here, no CTV fluorescent signal was subsequently identified within splenic CD11c+ or CD11b+ cell populations (Figure 1A, middle panels).

Figure 1. CD8α+ DCs acquire leukemia-derived cellular cargo in vivo.

A-C. 4 × 106 C1498 AML cells (n = 12) or 106 syngeneic CD4+ T cells (n = 4) were CTV-labeled and inoculated IV into C57BL/6 mice. Three hours later, splenic CD11b+ or CD11c+ cells were analyzed for CTV fluorescence. A. Representative plots depicting acquired CTV fluorescence among CD11c+ and CD11b+ cell populations are shown. B. Quantified data from (A) are shown. C. The frequency of CTV-positive splenic CD11c+ and CD11b+ cells is shown after gating on total CTV-positive events. D. Splenic DC subsets were analyzed for CTV acquisition after inoculation of labeled C1498 cells (n = 6 mice per time point). Representative plots are shown. E. Quantification of the frequency of CTV-positive CD8α+ or CD11b+ cDCs at the indicated time points following inoculation of labeled C1498 cells. F. ImageStreamX analysis of splenic DC subsets three hours following IV inoculation of CTV-labeled C1498 cells. The top row depicts a CTV+ leukemia cell. Rows 2-5 depict a CD11c+ cell, a CD11b+ cell, a CD11c+CD11b+ DC, and a CD8α+ DC, respectively, all of which are negative for CTV fluorescence. Rows 6-7 are representative images of CD8α+ DCs containing a clear intracellular CTV fluorescent signal. G. C1498 cells were treated with gemcitabine (10μM) for 0, 24, 48 or 72 hours, CTV-labeled, and inoculated IV into C57BL/6 mice (n = 8 per time point). Quantified data depicting frequencies of CTV-positive splenic CD11b+ or CD11c+ cells are shown. Data were pooled from (B, C, E and G), or are representative (A, D and F) of at least three independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.00

Splenic DCs are comprised of several distinct populations, each with unique developmental requirements and functional capabilities. These include conventional CD11c+CD11b+ and CD8α+ DCs (cDCs), as well as plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). To investigate whether the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo was an exclusive function of a single DC subset, or was a shared property, a more detailed phenotypic analysis was performed on CD11c+ cells that contained CTV fluorescence following a systemic leukemia cell challenge. CTV fluorescence was not observed within pDCs (Figure 1D, upper panel). Among cDCs, however, leukemia-derived CTV fluorescence was consistently and almost exclusively observed within a subset of CD8α+ DCs at all time points analyzed (Figure 1D, lower panel, and E). To ensure that the leukemia-derived CTV signal observed in CD8α+ DCs was truly intracellular, as opposed to representing cellular conjugates or fragments of fused plasma membranes, single cell image cytometry was performed with ImageStreamX, which confirmed the intracellular localization of CTV fluorescence in CD8α+ DCs (Figure 1F), consistent with the notion that phagocytosis of leukemia cells or their cellular cargo had occurred. Furthermore, co-expression of markers previously associated with CD8α+ DCs, including DEC-205 and DNGR-1, as well as high levels of MHC class I and II, but not CD4 or Sirpα, was observed on CTV+ CD8α+ DCs (Supplementary Figure 1 and data not shown) (30). Only rare CTV fluorescence was observed in MHC class II+ cells in the lungs or livers of leukemia-challenged animals, indicating that the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo occurred primarily within the spleen (data not shown). Collectively, these results demonstrate that splenic CD8α+ DCs primarily acquire cargo from circulating leukemia cells in vivo.

To next examine whether leukemia cell viability was an important determinant in regulating in vivo engulfment by CD8α+ DCs, C1498 cells were cultured in the presence of gemcitabine chemotherapy to induce death prior to their introduction into recipient mice. While only ~5% of cultured C1498 cells were apoptotic or dead in the absence of gemcitabine, this frequency increased significantly over time with gemcitabine treatment (Supplementary Figure 2A). Strikingly, inoculation of largely dead or dying leukemia cells resulted in a dramatic shift in acquired CTV fluorescence from CD11c+ cells (DCs) to CD11b+F4/80+ cells (macrophages), which correlated directly with the input frequency of annexin V and propidium iodide dual-positive C1498 cells (Figure 1G and Supplementary Figure 2B), indicating that the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo by CD11c+ cells occurs independently of overt cell death.

Lastly, the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo by CD8α+ DCs was not restricted to the C1498 model, but was similarly observed with a second transplantable leukemia cell line, as well as with primary leukemia cells derived from a genetically engineered, syngeneic AML model (Supplementary Figure 2C). Interestingly, CD8α+ DCs also primarily acquired CTV fluorescence following the systemic introduction of labeled B16 melanoma cells (Supplementary Figure 2C). These observations demonstrate that the in vivo acquisition of cancer cell material by CD8α+ DCs is not limited to leukemia, but rather appears to be a more general phenomenon with circulating tumor cells, regardless of their tissue of origin. It is interesting to speculate that endocytic receptor(s) preferentially expressed by CD8α+ DCs may regulate this unique function. Lastly, the finding that CD8α+ DCs exclusively acquire material from circulating malignant cells contrasts greatly with previous observations in solid cancer models, in which a variety of DC and macrophage populations were capable of tumor cell phagocytosis (5).

CD8α+ DCs cross-present leukemia antigens to CD8+ T cells directly ex vivo

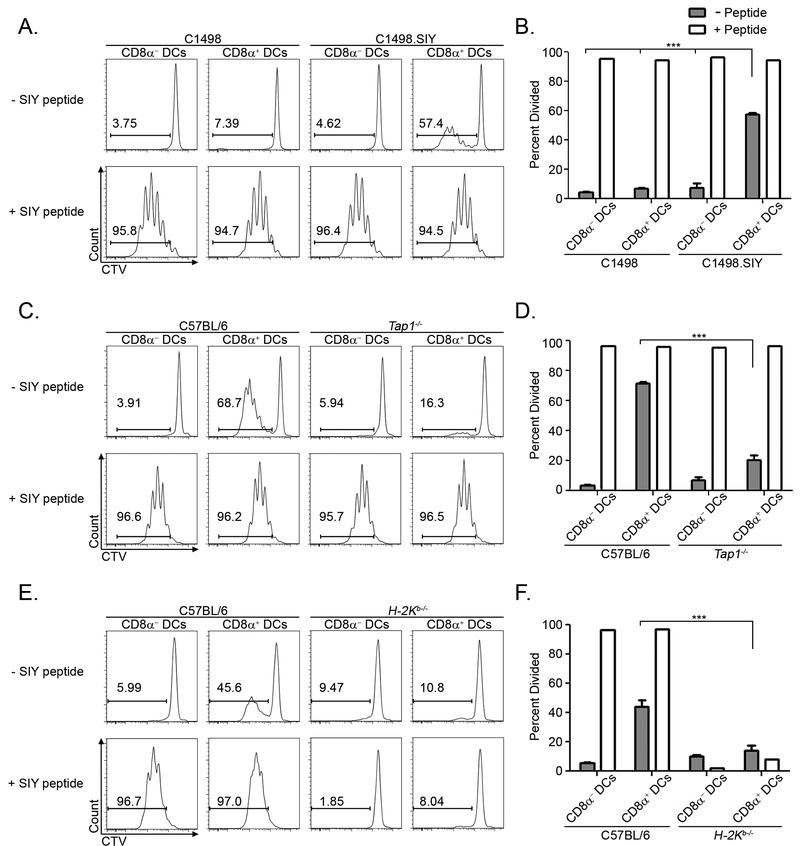

Given that CD8α+ DCs were adept at capturing material from circulating leukemia cells, we next determined whether they were also capable of presenting leukemia antigens to CD8+ T cells. Because native antigens expressed by C1498 cells have not been defined, we engineered their expression of a model peptide antigen, SIYRYYGL (SIY), which is presented in the context of the MHC I molecule H-2Kb in C57BL/6 mice. This approach endowed C1498 leukemia cells with a tractable antigen, the presentation of which could be assessed experimentally. Parental C1498 cells or C1498.SIY cells were inoculated into recipient mice and splenic CD8α− and CD8α+ DCs were subsequently isolated and cultured with CTV-labeled, SIY antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (2C T cells). The degree of 2C T cell proliferation following co-culture with purified APC populations was utilized as an indicator of leukemia antigen presentation. In this context, only CD8α+, but not CD8α− DCs from mice initially challenged with C1498.SIY cells induced the proliferation of 2C T cells directly ex vivo (Figure 2A and B). When exogenous SIY peptide was added to the cultures, CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs were equally effective at inducing 2C T cell proliferation, indicating that both populations were capable of supporting T cell division (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2. CD8α+ DCs exclusively cross-present a leukemia-derived antigen directly ex vivo.

A and B. 4 × 106 C1498 or C1498.SIY cells were inoculated IV into C57BL/6 mice. Three hours later, splenic CD8α+ or CD8α− DCs were isolated by FACS and cultured with CTV-labeled 2C T cells for 72 hours. 2C T cell division was assessed by measuring the dilution of the CTV signal via flow cytometry. Where indicated, DCs were pulsed with 100nM SIY peptide prior to culture. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM. *** p<0.001. C-F. 4 × 106 C1498.SIY cells were inoculated IV into C57BL/6 and Tap1−/− mice (C and D) or H-2Kb−/− mice (E and F), and cross-presentation assays were performed as in A. N = 3 mice per group for all panels. Data are representative of two independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM. *** p<0.001

We next sought to characterize pathways of leukemia antigen presentation in CD8α+ DCs. Given their known proficiency for presenting exogenously-acquired antigens on MHC I molecules – a phenomenon known as cross-presentation (31), it was of interest to elucidate whether leukemia antigen presentation by CD8α+ DCs was occurring though classical cross-presentation, or via an alternative antigen presentation pathway. Cross-presentation of acquired soluble or cellular antigens requires transporter associated with antigen processing 1 (TAP1), which shuttles peptides derived from proteasomal degradation into MHC I-containing organelles for subsequent MHC I loading and cell surface display (32, 33). As shown in Figure 2C and D, 2C T cell proliferation was severely blunted upon co-culture with CD8α+ DCs isolated from leukemia-challenged Tap1−/− mice. Furthermore, the ability of CD8α+ DCs from leukemia-challenged animals to mediate ex vivo antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation required their expression of H2-Kb, suggesting that direct acquisition of intact, antigen-loaded MHC I molecules from leukemia cells by CD8α+ DCs was not occurring to any meaningful degree (Figure 2E and F). Together, these data reveal that presentation of an MHC I-restricted leukemia antigen is mediated predominantly by CD8α+ DCs through a classical TAP1-dependent cross-presentation pathway.

Lastly, a C-type lectin superfamily receptor, DNGR-1 (encoded by the Clec9a gene) has previously been shown to regulate cross-presentation of necrotic cell antigens to CD8+ T cells (34). DNGR-1 specifically recognizes F-actin, which is exposed during necrosis (35). Although not required for dead cell phagocytosis, DNGR-1 regulates endocytic trafficking of dead cell antigens to facilitate their cross-presentation (34). As DNGR-1 is preferentially expressed by CD8α+ DCs, Clec9a-deficient (Clec9agfp/gfp) mice were employed in order to determine the extent to which DNGR-1 regulated cross-presentation of leukemia antigens to CD8+ T cells. As expected, DNGR-1 was dispensable for the in vivo uptake of leukemia cell cargo by CD8α+ DCs (Supplementary Figure 3A and B). Furthermore, the proliferation of adoptively transferred leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells was equivalent in leukemia-challenged Clec9a+/+ and Clec9agfp/gfp mice (Supplementary Figure 3C and D), indicating that DNGR-1 is not required for the cross-presentation of leukemia antigens by CD8α+ DCs.

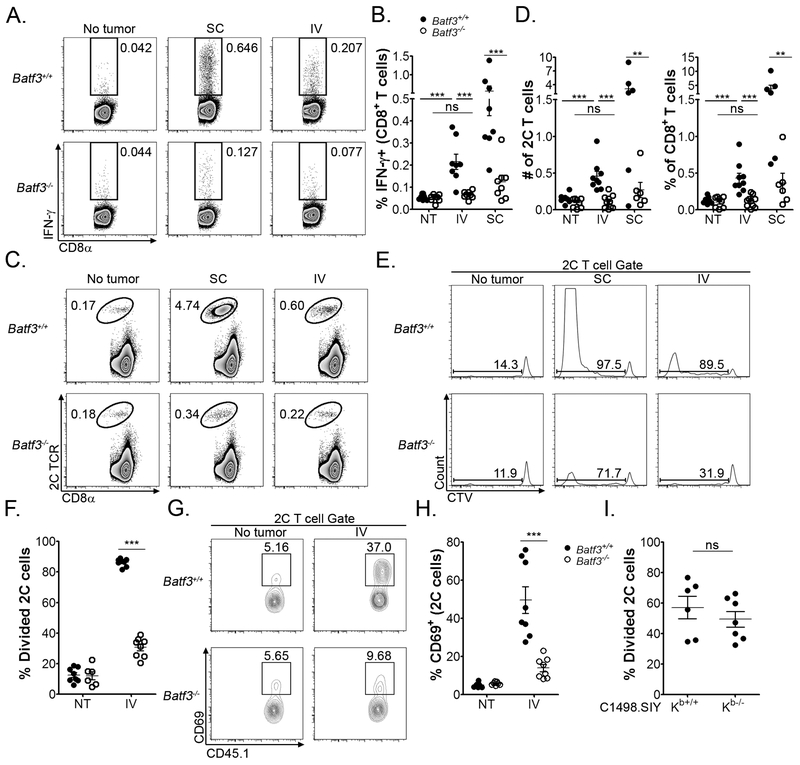

In vivo leukemia antigen encounter by CD8+ T cells is driven by CD8α+ DCs

In the solid tumor context, Batf3-dependent CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs are absolutely required for the spontaneous activation of anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses (1, 5–7, 36). The data presented above suggest that Batf3-lineage CD8α+ DCs may also regulate CD8+ T cell responses to leukemia-derived antigens. To directly compare the role of Batf3-lineage DCs in directing tumor-specific CD8+ T cell fates in the setting of a localized versus systemic malignancy, C1498.SIY cells were inoculated into Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (which harbor significantly reduced numbers of CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs) (8, 36), either subcutaneously to model development of a localized, solid tumor, or intravenously to mimic a systemic leukemia. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses were assessed 5-6 days later. Robust endogenous SIY antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses were generated in Batf3+/+ mice with localized C1498 tumors, as we have previously shown (Figure 3A, upper row, middle panel, and B) (19). Moreover, adoptively transferred, leukemia-specific, CD8+ T cells underwent a striking expansion in Batf3+/+ mice with localized C1498 tumors (Figure 3C, upper row, middle panel and D). In contrast, numbers of activated endogenous (Figure 3A, lower row, middle panel and B) and adoptively transferred antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 3C, lower row, middle panel, and D) were significantly diminished in Batf3−/− mice with localized C1498 tumors. These data, consistent with published reports (1, 5–7, 36), demonstrate an essential role for Batf3-dependent DCs in the priming of functional CD8+ T cell responses against localized tumors.

Figure 3. CD8α+ DCs mediate leukemia antigen recognition by CD8+ T cells in vivo.

A and B. 106 C1498.SIY cells were inoculated SC (n = 6) or IV (n = 8) into Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (NT: No tumor, n = 6). Six days later, IFN-γ production by endogenous splenic CD8+ T cells from leukemia-bearing or naïve mice was analyzed by flow cytometry following a brief SIY peptide re-stimulation. A. Representative plots are shown. B. Quantified data from A. showing the frequencies of IFN-γ CD8+ T cells in each cohort. C-F. 106 CTV-labeled 2C T cells were adoptively transferred into Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (n = 8 per group), which were subsequently challenged with 106 C1498 cells SC or IV. Six days later, the frequency, number and division of the transferred 2C T cells was assessed. C. Representative plots demonstrating the frequency of 2C T cells among the total CD8+ T cell population in C1498.SIY-challenged or naïve mice are shown. D. Absolute 2C T cell numbers (left) and frequencies (right) from the indicated groups in C. E. Representative plots depicting CTV dilution of transferred 2C T cells in C1498.SIY-challenged or naïve mice are shown after gating on the entire 2C T cell population (either 1B2+ or CD45.1+ cells). F. Quantified data demonstrating the percentage divided 2C T cells in the indicated groups from E. G and H. 2C T cells (CD45.1+) were adoptively transferred into Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (n = 8 per group), followed by IV inoculation of C1498.SIY cells one day later. Thirty-six hours following C1498.SIY cell inoculation, CD69 expression was analyzed on transferred 2C T cells. G. Representative plots showing CD69 expression after gating on 2C T cells (CD45.1+). H. Quantification of data from G. I. 106 CTV-labeled 2C T cells were adoptively transferred into groups of C57BL/6 mice, followed 1 day later by IV inoculation of 106 Kb+/+ (n = 6) or Kb−/− (n = 7) C1498.SIY cells. Six days later, 2C T cell division was assessed. Data are representative of (A, C, E and G), or pooled from (B, D, F, H and I) from 2-4 independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001. NS – not significant. NT - no tumor.

In mice with systemic C1498 leukemia, frequencies of activated leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells in Batf3+/+ mice were lower than those observed in Batf3+/+ mice with localized C1498 tumors, but were significantly higher than those present in naïve animals (Figure 3A, upper row, right panel, and B). In Batf3−/− mice with systemic leukemia, however, frequencies of endogenous antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were similar to those present in naïve animals (Figure 3A, lower row, right panel, and B). An identical result was obtained following adoptive transfer of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 3C, right panels, and D).

Furthermore, the vast majority of adoptively transferred, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells proliferated in Batf3+/+ mice following a systemic leukemia cell challenge (Figure 3E and F), and many upregulated CD69, consistent with in vivo antigen encounter (Figure 3G and H). Strikingly, in leukemia-challenged Batf3−/− hosts, most adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells remained undivided (Figure 3E and F), and far fewer had upregulated CD69 (Figure 3G and H). Activation of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells was not simply delayed in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− hosts, as similar results were obtained at later time points (data not shown). Lastly, the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo by a compensatory splenic DC or macrophage population was not observed in Batf3−/− mice (data not shown).

To examine whether leukemia cells played a direct role in mediating antigen encounter by antigen-specific T cells in vivo, the proliferation of adoptively transferred, leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells was compared in wild-type animals that received a systemic challenge with H2-Kb-deficient (Kb−/−) or -sufficient (Kb+/+) C1498.SIY cells. The proliferation of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells was identical, regardless of the ability of leukemia cells to directly present the SIY antigen (Figure 3I). Collectively, these data demonstrate that CD8α+ DCs primarily mediate leukemia antigen recognition by CD8+ T cells in vivo, and reveal the inefficiency with which C1498 leukemia cells and other APC populations present leukemia antigens to CD8+ T cells.

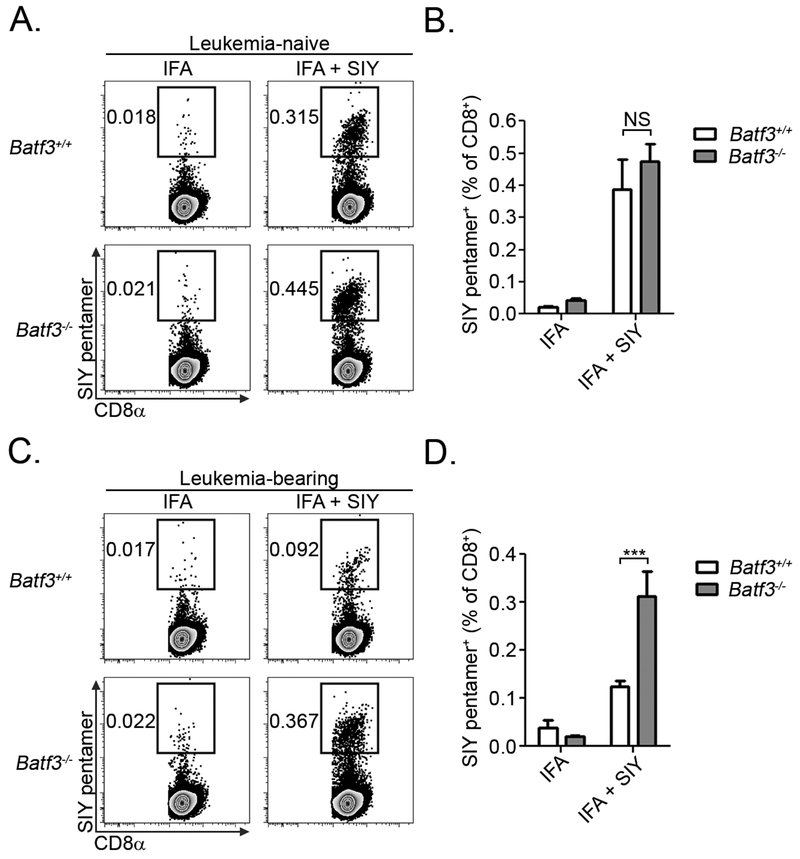

CD8α+ DCs induce leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance

We previously identified a mechanism of T cell tolerance in leukemia-bearing mice, in which leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells encountered antigen, underwent several rounds of abortive proliferation, and were subsequently deleted from the host (19). This form of deletional tolerance could be prevented by over-expression of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-XL, in leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells (19). However, it remained unclear whether leukemia cells or host APCs were responsible for mediating this phenomenon. The results presented above clearly indicate that CD8α+ DCs play a major role in antigen presentation to leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells, and suggest they may also be responsible for mediating the induction of CD8+ T cell tolerance in leukemia-bearing animals. If this is the case, then the largely naive antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− mice (Figure 3E-G) should expand more vigorously than “tolerized” CD8+ T cells in leukemia-bearing Batf3+/+ mice following a secondary antigenic challenge. To test this hypothesis, we vaccinated mice with SIY peptide emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA), which stimulated a robust SIY-specific CD8+ T cell response independently of Batf3-lineage DCs in leukemia-free mice (Figure 4A and B). Consistent with our hypothesis, the frequency of SIY-reactive CD8+ T cells was only minimally higher in leukemia-bearing Batf3+/+ mice vaccinated with IFA plus SIY peptide compared to IFA alone, demonstrating the inability of this immunogenic vaccine to induce antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion (Figure 4C and D). In contrast, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells expanded to a significantly greater degree in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− mice vaccinated with IFA plus SIY peptide (Figure 4C and D). These results demonstrate that CD8α+ DCs mediate the induction of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance in vivo.

Figure 4. CD8α+ DCs induce peripheral T cell tolerance against leukemia-derived antigens in vivo.

A and B. Naïve Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (n = 6 per group) were vaccinated SC with IFA alone or IFA plus SIY peptide. Five days later, the frequency of SIY pentamer-reactive CD8+ T cells from the vaccine-draining lymph node was analyzed in each group. Representative plots are shown in A after gating on CD8+ T cells. C and D. Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice (n = 6 per group) received an IV inoculation of 5 × 106 C1498.SIY cells. Six days later, mice were vaccinated with IFA alone or IFA plus SIY peptide. Five days following vaccination, the frequency of SIY pentamer-reactive CD8+ T cells from the vaccine-draining lymph node was analyzed in each group. Representative plots are shown in C after gating on CD8+ T cells. Data from B and D are pooled from two independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM. *** p<0.001. NS - not significant

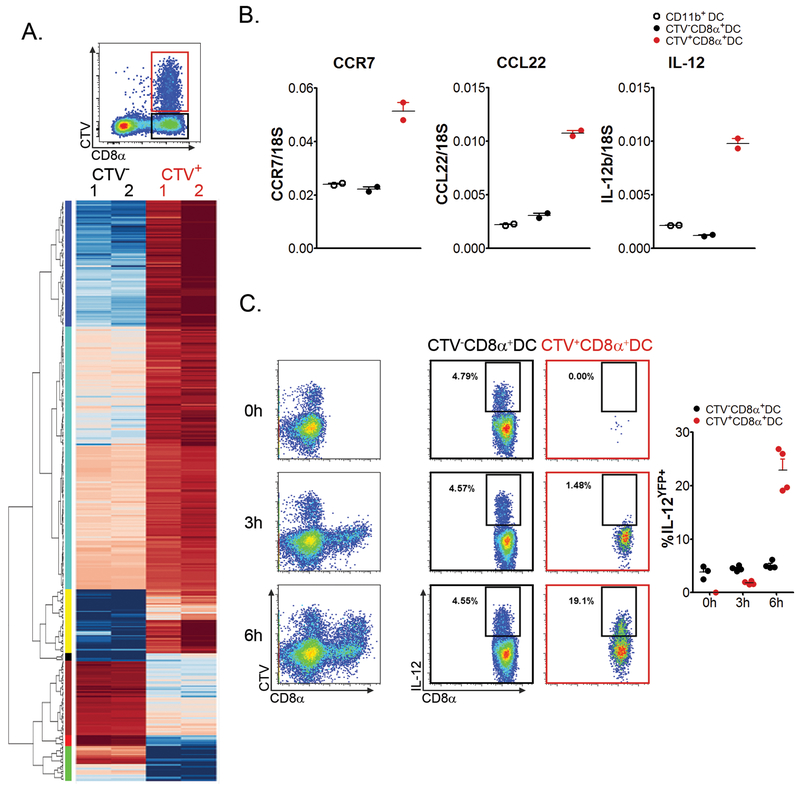

Acquisition of leukemia cell cargo activates a unique transcriptional program in CD8α+ DCs

Having identified a DC population with bona fide tolerogenic properties in vivo, it was of interest to determine whether engulfment of leukemia cell cargo associated with the activation of genes potentially involved in regulating the tolerogenic phenotype of CD8α+ DCs. Thus, CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs were isolated from spleens of wild-type mice that received a systemic challenge with CTV-labeled leukemia cells 6 hours earlier (Figure 5A - top). Two cohorts of 10 mice were included in order to isolate sufficient quantities of RNA for sequencing, as well as to include 2 experimental replicates. Significantly differentially expressed mRNAs in CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs were identified using Cuffdiff, DEseq, DEseq2 and edgeR software. After normalization, 12,685 annotated genes were included for analysis. 366 genes (2.9%) were found to be significantly differentially expressed (log2-fold change ≥ 2; p < 0.001) in CTV+ CD8α+ DCs compared to CTV− CD8α+ DCs (311 upregulated; 55 downregulated) (Figure 5A - bottom, and Supplementary Table 1). The increased expression of several genes in CTV+ versus CTV− CD8α+ DCs identified through RNA sequencing was validated by reverse-transcriptase quantitative PCR (Figure 5B). Gene ontogeny (GO) analysis top hits included cell migration, defense response, and regulation of immune system processes. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) revealed that the 3 top pathways activated in CTV+ CD8α+ DCs were crosstalk between DCs and NK cells, dendritic cell maturation, and granulocyte adhesion/diapedesis. Differentially-expressed candidate immune suppressive genes upregulated in CTV+ CD8α+ DCs included (log2-fold change): ccl22 - 3.92, cblb - 3.10, and il4i1 (IL4-induced gene protein 1) - 2.95, among others. Interestingly, a number of genes upregulated in CTV+ CD8α+ DCs were those classically associated with DC activation, most notably il12b (log2-fold change - 5.05). At the protein level, the acquisition of leukemia cell cargo clearly induced IL-12 production in a time-dependent manner in CTV+ but not CTV− CD8α+ DCs (Figure 5C). Overall, these results suggest that engulfment of leukemia cell cargo is correlated with a unique transcriptional program in CD8α+ DCs that may be important in regulating their tolerogenic properties in vivo. While tolerance is the phenotypic outcome of interactions between leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells and CD8α+ DCs, this appears to be dependent on a finely-tuned and complex genetic program in the latter.

Figure 5. Acquisition of leukemia cell cargo is associated with a unique transcriptional profile in CD8α+ DCs.

A. Groups of 10 C57BL/6 mice were challenged with CTV-labeled C1498 cells IV. Six hours later, CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs were isolated by FACS. Top - Plot depicting the gating strategy for isolating CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs after inoculation of labeled C1498 cells. Gating was performed on entire cDC populations. Bottom - Heat map demonstrating clusters of differentially-expressed genes in CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs through RNA sequencing. B. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on RNA isolated from CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs, as well as CD11b+ DCs from A. Expression levels of ccr7, ccl22, and il12b are shown. 18s was used as an internal control. C. Il12byfp mice were challenged with CTV-labeled C1498 cells. At the indicated time points IL-12b reporter activity was assessed. The left column - Plots depicting IL-12β reporter activity among CTV+ and CTV− DCs among the entire CD11c+ cell population are shown. Middle and right columns - Plots depicting IL-12β reporter activity among CTV+ and CTV− CD8α+ DCs, respectively, which is quantified in the graph on the right. Data are pooled from (A), or are representative of (B and C) 2 independent experiments, and are shown as mean ± SEM.

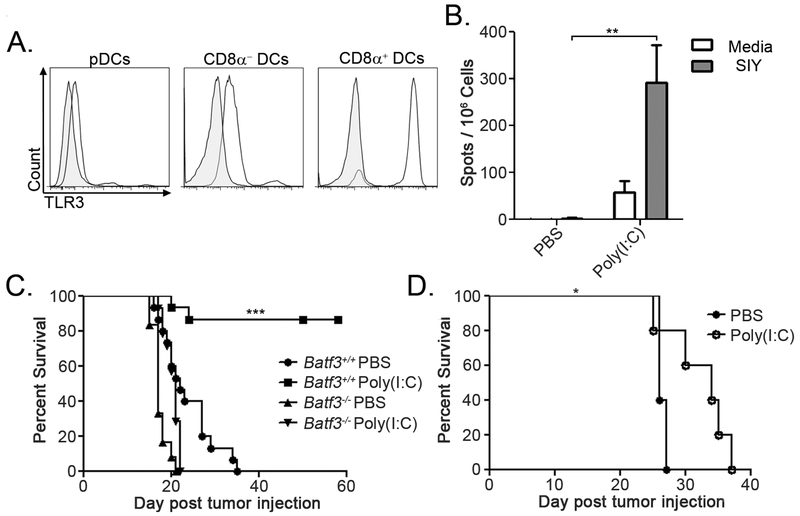

Activation of CD8α+ DCs prevents AML-induced T cell tolerance

The maturation state of CD8α+ DCs may be a critical factor in their ability to either activate or tolerize leukemia-specific T cells in vivo. To determine whether activation of CD8α+ DCs in leukemia-bearing mice could prevent the induction of CD8+ T cell tolerance, we took advantage of their unique expression of particular pattern recognition receptors (30). CD8α+ DCs have been shown to express high levels of Toll-like receptor-3 (TLR-3), which naturally recognizes viral double-stranded RNA (37). We also observed very high TLR-3 expression in CD8α+ DCs, but not in other DC subsets or in C1498 cells (Figure 6A and data not shown). Thus, the synthetic TLR-3 agonist, poly(I:C), was utilized to stimulate CD8α+ DCs in vivo. Poly(I:C) administered to naïve mice stimulated IL-12 production in CD8α+ DCs, but not in other DC or macrophage subsets (data not shown), suggesting that its effects were acting specifically on CD8α+ DCs in vivo. Poly(I:C) treatment induced incredibly robust leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell responses, and led to prolonged survival of leukemia-bearing mice (Figure 6B and C). Importantly, the effect of poly(I:C) on promoting prolonged survival following leukemia cell challenge was completely abrogated in Batf3−/− mice (Figure 6C), suggesting that its effect was mediated through CD8α+ DCs, and not another immune cell population. Poly(I:C) also prolonged survival of mice harboring parental C1498 AML, suggesting that TLR-3-induced activation of CD8α+ DCs promoted enhanced immunity to naturally-expressed leukemia antigens (Figure 6D). The finding that the effectiveness of in vivo TLR-3 stimulation required CD8α+ DCs indicates that their activation is essential for a productive anti-leukemia CD8+ T cell response to ensue.

Figure 6. CD8α+ DC activation prevents the induction of leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance.

A. Representative plots demonstrating intracellular TLR-3 expression among splenic DC populations in C57BL/6 mice. Shaded histograms represent isotype control staining. B. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were challenged IV with 106 C1498.SIY cells, and received poly(I:C) or PBS IP on days 0 and 3. On day six, splenocytes were stimulated with media or 100nM SIY peptide in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. C. Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice were challenged with 106 C1498.SIY cells IV, and received poly(I:C) or PBS every 3 days for 15 days, starting on day 0. Survival was assessed. Batf3+/+, n=15 per treatment; Batf3−/−, PBS: n=12, poly(I:C): n=14. D. C57BL/6 mice were challenged with 106 parental C1498 cells IV, and were treated with poly(I:C) or PBS every 3 days for 15 days, starting on day 0 (n=5 per group). Survival was assessed. Data are representative of (A, B and D) or pooled (C) from at least two independent experiments. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Discussion

The APC populations that acquire and present antigens to initiate CD8+ T cell priming in the solid tumor context have been well-characterized, primarily through the use of murine cancer models (5–7). Several groups have independently identified Batf3-lineage DCs as the predominant APC subset required for the spontaneous activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (1, 5–7, 36). Furthermore, key cytokines and tumor-derived factors that facilitate the Batf3-dependent DC maturation in the tumor and its draining lymph nodes have recently been elucidated (1, 3). In contrast, the APCs that regulate CD8+ T cell responses in hosts with acute leukemia have not been well-defined. This is an important consideration given that the outcomes of interactions between leukemia cells and the host immune system may be quite different compared to what has been reported in the solid cancer context. Moreover, a more thorough understanding of the processes that control anti-leukemia immune responses will be essential for the development of rational immunotherapeutic strategies for patients with leukemia. Our results provide several key insights into the cellular processes that dictate CD8+ T cell fates in leukemia-bearing hosts.

First, through the use of flow and ImageStream cytometry, we identified a population of splenic CD8α+ DCs with the near exclusive capability of acquiring leukemia cell cargo in vivo. Given the numerous DC and macrophage populations that reside within the murine spleen, which are presumably poised to interact with leukemia cells, this observation was striking. The lack of compensatory leukemia cell engulfment by another DC or macrophage population in spleens of Batf3−/− mice suggests that CD8α+ DCs are either anatomically well-positioned to capture leukemia antigens as they enter the spleen from the circulation, or they selectively express endocytic receptors that promote leukemia cell engulfment. Although the nature of such a receptor remains elusive, DNGR-1 (Supplementary Figure 3), as well as LRP-1 and SIRPα (data not shown), were dispensable. While the data presented in Figure 1 indicates that the engulfment of leukemia cells by CD8α+ DCs occurred independently of overt cell death, our experiments do not rule out the possibility that leukemia cells undergoing early apoptosis in vivo might be preferentially targeted for capture. If this is the case, then endocytic receptors such as TIM-3, TIM-4, MerTK or CD36 may be involved, as each has been shown to regulate uptake of apoptotic cells (38–41). Furthermore, a subset of macrophages that expresses CD169 (sialoadhesin) has been implicated in the acquisition and presentation of antigens from dead tumor cells to CD8+ T cells (42). However, we were unable to detect a CTV signal in splenic CD169+ macrophages following systemic inoculation of labeled leukemia cells (data not shown). Regardless, the CD8+ T cell tolerant phenotype induced by CD8α+ DCs that have engulfed leukemia-derived antigens is similar to that previously observed following intravenous inoculation of apoptotic cells (43).

Importantly, the singular ability of CD8α+ DCs to capture leukemia-derived cellular material was not limited to the C1498 model, but was also consistently seen with several leukemia models, and with B16 melanoma cells. This result argues that endocytosis of material from circulating cancer cells is a general property of CD8α+ DCs. Furthermore, our results suggest that the context in which tumor antigen capture and presentation by CD8α+ DCs occurs may ultimately dictate outcomes of subsequent interactions with CD8+ T cells. This will be important to characterize more thoroughly in future studies.

A second compelling finding was the almost absolute requirement for CD8α+ DCs in mediating leukemia antigen recognition by CD8+ T cells in vivo. The significantly reduced proliferation and CD69 upregulation among antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− hosts clearly revealed that cross-presentation of leukemia antigens by CD8α+ DCs was critical in driving CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. In fact, the absence of host CD8α+ DCs resulted largely in antigen-specific CD8+ T cell ignorance in leukemia-bearing animals, further supporting this conclusion. The few leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells that proliferated in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background may have occurred due to an incomplete deficiency of CD8α+ DCs, which has been previously reported (44). Surprisingly, direct antigen presentation by MHC I-expressing leukemia cells appeared to be dispensable for early antigen counter by CD8+ T cells.

The observation that CD8α+ DCs were dominant in the capture and presentation of leukemia antigens in vivo, coupled with our previous report demonstrating the induction of deletional CD8+ T cell tolerance in mice with leukemia (19), indirectly implicated CD8α+ DCs in mediating the T cell tolerant phenotype. The finding that an immunogenic peptide vaccine failed to induce the expansion of endogenous leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells in wild-type mice with leukemia, but did so in leukemia-bearing Batf3−/− mice, clearly indicated that CD8α+ DCs promoted CD8+ T cell tolerance in animals with systemic leukemia. When considering the importance of Batf3-lineage DCs in regulating CD8+ T cell activation against solid tumors (1, 5–7, 36), and Figure 3, our results reveal that DCs of the identical lineage imprint a completely divergent program in CD8+ T cells in the context of an acute leukemia.

Transcriptional profiling of CD8α+ DCs that acquired leukemia cell cargo in vivo (i.e. tolerogenic CD8α+ DCs) provides novel insight into potential mechanisms by which these DCs regulate the induction of CD8+ T cell tolerance in leukemia-bearing mice. Here, approximately 3% of genes analyzed were significantly differentially expressed in CTV+ CD8α+ DCs compared with the larger population of CD8α+ DCs that did not acquire CTV fluorescence following leukemia cell challenge. Several candidate genes that encode for proteins with known tolerogenic functions were highly upregulated in CD8α+ DCs after engulfment of leukemia cell material in vivo, including ido1 (tryptophan catabolism), ccl22 (regulatory T cell recruitment), and il41l (hydrogen peroxide generation). The contribution of these proteins to CD8α+ DC-mediated T cell tolerance will need to be established through direct experimentation. Conversely, a number of genes upregulated in CD8α+ DCs following acquisition of leukemia cell material have been associated with DC activation, most notably, il12b. Thus, it is likely that CD8α+ DCs contribute both tolerogenic and canonical pro-inflammatory cytokines to the local environment following phagocytosis of leukemia cargo, with the balance skewed toward those that promote immune tolerance. We anticipate that this result may offer new clues into molecular pathways utilized by DCs to mediate T cell tolerance in other contexts, as in vivo transcriptional profiling DCs with clear tolerogenic properties has not been previously reported. Further investigation into the effects of TLR3 administration on gene regulation in CD8α+ DCs that have captured leukemia cell cargo may help to clarify the relative contributions of pathways essential in driving the tolerogenic CD8α+ DC phenotype.

In many cases, activated T cells spontaneously infiltrate solid cancer, but are functionally impaired by immune evasion mechanisms active in the tumor environment (45). Here, immune therapies, such as anti-PD-1 antibodies, aimed at restoring the function of previously-activated T cells, may be effective. In contrast, our data suggests that CD8+ T cells are never functionally primed in leukemia-bearing mice, but rather are tolerized rapidly after encountering leukemia antigens presented by CD8α+ DCs. Although speculative, our results may partially explain the relative ineffectiveness of checkpoint blockade therapy in patients with acute leukemias. We would propose that therapies designed to promote APC maturation, such as TLR, CD40 or STING agonists (19, 46), may be more effective in stimulating anti-leukemia immunity in patients. Alternatively, with the recent demonstration that human Batf3-lineage DCs (also known as cDC1) can be effectively generated from bone marrow progenitors with provision of a NOTCH2-activating ligand, GM-CSF and/or FLT3 ligand (47, 48), it is interesting to speculate that cDC1-based vaccines may represent another approach to promote anti-leukemia T cell immunity in AML patients.

Collectively, our data support a growing body of evidence that has defined a prominent role for Batf3-lineage CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs in regulating anti-cancer immune responses (1, 5–7, 36). In solid tumors, Batf3-dependent DCs are essential for the priming of functional anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses. In stark contrast, our results demonstrate that the same DC subset actively promotes CD8+ T cell tolerance in leukemia-bearing hosts. These observations argue that environmental cues perceived by CD8α+ DCs may differentially control their ability to either activate or tolerize cancer-specific CD8+ T cells. The discovery that CD8α+ DCs mediate leukemia-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance is impactful in that it highlights stark differences in the regulation of T cell responses to solid cancers versus leukemia. These results provide strong rationale for the incorporation of approaches aimed at activating CD8α+ DCs into immunotherapies for patients with leukemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ryan Duggan, David Leclerc, and Mike Olson from the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at the University of Chicago for assistance with cell sorting and analysis of ImageStreamX data. We thank Peter Savage and Thomas Gajewski for their critical review of the manuscript.

Financial support: D.E.K. and B.W.M were funded by the immunology training grant at the University of Chicago (T32 AI007090). This work was funded by R01 CA16670 to J.K. The Center for Research Informatics is funded by the Biological Sciences Division at the University of Chicago with additional funding provided by the Institute for Translational Medicine, CTSA grant number UL1 TR000430 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Fuertes MB, Kacha AK, Kline J, Woo SR, Kranz DM, Murphy KM, and Gajewski TF. 2000. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8{alpha}+ dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med 208(10): 2005–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, Mashayekhi M, Dunn GP, Archambault JM, Lee H, Arthur CD, White JM, Kalinke U, Murphy KM, and Schreiber RD. 2011. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J. Exp. Med 208(10): 1989–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo SR, Fuertes MB, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna MJ, Leung MY, Duggan R, Wang Y, Barber GN, Fitzgerald KA, Alegre ML, and Gajewski TF. 2014. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 41(5): 830–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelhardt JJ, Boldajipour B, Beemiller P, Pandurangi P, Sorensen C, Werb Z, Egeblad M, and Krummel MF. 2012. Marginating dendritic cells of the tumor microenvironment cross-present tumor antigens and stably engage tumor-specific T cells. Cancer Cell. 21(3): 402–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broz ML, Binnewies M, Boldajipour B, Nelson AE, Pollack JL, Erle DJ, Barczak A, Rosenblum MD, Daud A, Barber DL, Amigorena S, Van’t Veer LJ, Sperling AI, Wolf DM, and Krummel MF. 2014. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell. 26(5): 638–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts EW, Broz ML, Binnewies M, Headley MB, Nelson AE, Wolf DM, Kaisho T, Bogunovic D, Bhardwaj N, and Krummel MF. 2016. Critical Role for CD103(+)/CD141(+) Dendritic Cells Bearing CCR7 for Tumor Antigen Trafficking and Priming of T Cell Immunity in Melanoma. Cancer Cell. 30(2): 324–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmon H, Idoyaga J, Rahman A, Leboeuf M, Remark R, Jordan S, Casanova-Acebes M, Khudoynazarova M, Agudo J, Tung N, Chakarov S, Rivera C, Hogstad B, Bosenberg M, Hashimoto D, Gnjatic S, Bhardwaj N, Palucka AK, Brown BD, Brody J, Ginhoux F, and Merad M. 2016. Expansion and Activation of CD103(+) Dendritic Cell Progenitors at the Tumor Site Enhances Tumor Responses to Therapeutic PD-L1 and BRAF Inhibition. Immunity. 44(4): 924–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelson BT, Kc W, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, Moon C, Albring JC, Ise W, Michael DG, Bhattacharya D, Stappenbeck TS, Holtzman MJ, Sung SS, Murphy TL, Hildner K, and Murphy KM. 2010. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8alpha+ conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med 207(4): 823–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavin Y, Kobayashi S, Leader A, Amir ED, Elefant N, Bigenwald C, Remark R, Sweeney R, Becker CD, Levine JH, Meinhof K, Chow A, Kim-Shulze S, Wolf A, Medaglia C, Li H, Rytlewski JA, Emerson RO, Solovyov A, Greenbaum BD, Sanders C, Vignali M, Beasley MB, Flores R, Gnjatic S, Pe’er D, Rahman A, Amit I, and Merad M. 2017. Innate Immune Landscape in Early Lung Adenocarcinoma by Paired Single-Cell Analyses. Cell.169(4): 750–765 e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjord JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinski M, Jager N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, Lopez-Otin C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdes-Mas R, van’t Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome, Initiative, Icgc Breast Cancer Consortium, Icgc Mmml- Seq Consortium, Icgc PedBrain, Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ, and Stratton MR. 2013. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 500(7463): 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlin C, Kowalewski DJ, Schuster H, Mirza N, Walz S, Handel M, Schmid-Horch B, Salih HR, Kanz L, Rammensee HG, Stevanovic S, and Stickel JS. 2015. Mapping the HLA ligandome landscape of acute myeloid leukemia: a targeted approach toward peptide-based immunotherapy. Leukemia. 29(3): 647–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheibenbogen C, Letsch A, Thiel E, Schmittel A, Mailaender V, Baerwolf S, Nagorsen D, and Keilholz U. 2002. CD8 T-cell responses to Wilms tumor gene product WT1 and proteinase 3 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 100(6): 2132–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anguille S, Van de Velde AL, Smits EL, Van Tendeloo VF, Juliusson G, Cools N, Nijs G, Stein B, Lion E, Van Driessche A, Vandenbosch I, Verlinden A, Gadisseur AP, Schroyens WA, Muylle L, Vermeulen K, Maes MB, Deiteren K, Malfait R, Gostick E, Lammens M, Couttenye MM, Jorens P, Gossens H, Price DA, Ladell K, Oka Y, Fujiki F, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, and Berneman ZN. 2017. Dendritic cell vaccination as postremission treatment to prevent or delay relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 130(15): 1713–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenblatt J, Stone RM, Uhl L, Neuberg D, Joyce R, Levine JD, Arnason J, McMasters M, Luptakova K, Jain S, Zwicker JI, Hamdan A, Boussoitis V, Steensma DP, DeAngelo DJ, Galinsky I, Dutt PS, Logan E, Bryant MP, Stroopinsky D, Werner L, Palmer K, Coll M, Washington A, Cole L, Kufe D, and Avigan D. 2016. Individualized vaccination of AML patients in remission is associated with induction of antileukemia immunity and prolonged remissions. Sci. Transl. Med 8(368): 368ra171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiotto MT, Yu P, Rowley DA, Nishimura MI, Meredith SC, Gajewski TF, Fu XY, and Schreiber H. 2002. Increasing tumor antigen expression overcomes “ignorance” to solid tumors via crosspresentation by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Immunity. 17(6): 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Gajewski TF, and Kline J. 2009. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions inhibit antitumor immune responses in a murine acute myeloid leukemia model. Blood. 114(8): 1545–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teague RM, Sather BD, Sacks JA, Huang MZ, Dossett ML, Morimoto J, Tan X, Sutton SE, Cooke MP, Ohlen C, and Greenberg PD. 2006. Interleukin-15 rescues tolerant CD8+ T cells for use in adoptive immunotherapy of established tumors. Nat. Med 12(3): 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flies DB, and Chen L. 2003. A simple and rapid vortex method for preparing antigen/adjuvant emulsions for immunization. J. Immunol. Methods. 276(1-2): 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Chen X, Liu X, Kline DE, Teague RM, Gajewski TF, and Kline J. 2013. CD40 ligation reverses T cell tolerance in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Invest 123(5): 1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews S 2016. FastQC: A quality control application for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Institue Progect Page. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, and Salzberg SL. 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14(4): R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Wang S, and Li W. 2012. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 28(16): 2184–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh S, Chan CK. 2016. Analysis of RNA-Seq Data Using TopHat and Cufflinks. Methods Mol. Bio 1374: 339–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao Y, Smyth GK, and Shi W. 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 30(7): 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anders S, and Huber W. 2010. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Bio 11(10): R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15(12): 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, and Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26(1): 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang da W, Sherman BT, and Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc 4(1): 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supek F, Bosnjak M, Skunca N, and Smuc T. 2011. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One. 6(7): e21800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, and Mortha A. 2013. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31: 563–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blum JS, Wearsch PA, and Cresswell P. 2013. Pathways of antigen processing. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31: 443–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cebrian I, Visentin G, Blanchard N, Jouve M, Bobard A, Moita C, Enninga J, Moita LF, Amigorena S, and Savina A. 2011. Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 147(6): 1355–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, and Wearsch PA. 2005. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol. Rev 207: 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelenay S, Keller AM, Whitney PG, Schraml BU, Deddouche S, Rogers NC, Schulz O, Sancho D, and Reis e Sousa C. 2012. The dendritic cell receptor DNGR-1 controls endocytic handling of necrotic cell antigens to favor cross-priming of CTLs in virus-infected mice. J. Clin. Invest 122(5): 1615–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahrens S, Zelenay S, Sancho D, Hanc P, Kjaer S, Feest C, Fletcher G, Durkin C, Postigo A, Skehel M, Batista F, Thompson B, Way M, Reis e Sousa C, and Schulz O. 2012. F-actin is an evolutionarily conserved damage-associated molecular pattern recognized by DNGR-1, a receptor for dead cells. Immunity. 36(4): 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD, Murphy TL, and Murphy KM. 2008. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 322(5904): 1097–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jelinek I, Leonard JN, Price GE, Brown KN, Meyer-Manlapat A, Goldsmith PK, Wang Y, Venzon D, Epstein SL, and Segal DM DM. 2011. TLR3-specific double-stranded RNA oligonucleotide adjuvants induce dendritic cell cross-presentation, CTL responses, and antiviral protection. J. Immunol 186(4): 2422–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belz GT, Vremec D, Febbraio M, Corcoran L, Shortman K, Carbone FR, and Heath WR. 2002. CD36 is differentially expressed by CD8+ splenic dendritic cells but is not required for cross-presentation in vivo. J. Immunol 168(12): 6066–6070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyanishi M, Tada K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kitamura T, and Nagata S. 2007. Identification of Tim4 as a phosphatidylserine receptor. Nature. 450(7168): 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakayama M, Akiba H, Takeda K, Kojima Y, Hashiguchi M, Azuma M, Yagita H, and Okumura K. 2009. Tim-3 mediates phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and cross-presentation. Blood. 113(16) :3821–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallet MA, Sen P, Flores RR, Wang Y, Yi Z, Huang Y, Mathews CE, Earp HS, Matsushima G, Wang B, and Tisch R. 2008. MerTK is required for apoptotic cell-induced T cell tolerance. J. Exp. Med 205(1): 219–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asano K, Nabeyama A, Miyake Y, Qiu CH, Kurita A, Tomura M, Kanagawa O, Fujii S, and Tanaka M. 2011. CD169-positive macrophages dominate antitumor immunity by crosspresenting dead cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 34(1) :85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu K, Iyoda T, Saternus M, Kimura Y, Inaba K, and Steinman RM. 2002. Immune tolerance after delivery of dying cells to dendritic cells in situ. J. Exp. Med 196(8): 1091–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tussiwand R, Lee WL, Murphy TL, Mashayekhi M, Kc W, Albring JC, Satpathy AT, Rotondo JA, Edelson BT, Kretzer NM, Wu X, Weiss LA, Glasmacher E, Li P, Liao W, Behnke M, Lam SS, Arthur CT, Leonard WJ, Singh H, Stallings CL, Sibley LD, Schreiber RD, and Murphy KM. 2012. Compensatory dendritic cell development mediated by BATF-IRF interactions. Nature. 490(7421): 502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gajewski TF, Meng Y, Blank C, Brown I, Kacha A, Kline J, and Harlin H. 2006. Immune resistance orchestrated by the tumor microenvironment. Immunol. Rev 213: 131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curran E, Chen X, Corrales L, Kline DE, Dubensky TW Jr., Duttagupta P, Kortylewski M, and Kline J. 2016. STING Pathway Activation Stimulates Potent Immunity against Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell Rep. Cell Rep. 15(11): 2357–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balan S, Arnold-Schrauf C, Abbas A, Couespel N, Savoret J, Imperatore F, Villani AC, Vu Manh TP, Bhardwaj N, and Dalod M. 2018. Large-Scale Human Dendritic Cell Differentiation Revealing Notch-Dependent Lineage Bifurcation and Heterogeneity. Cell Rep 24(7): 1902–1915 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkling ME, Cytlak U, Lau CM, Lewis KL, Resteu A, Khodadadi-Jamayran A, Siebel CW, Salmon H, Merad M, Tsirigos A, Collin M, Bigley V, and Reizis B. 2018. Notch Signaling Facilitates In Vitro Generation of Cross-Presenting Classical Dendritic Cells. Cell Rep 23(12): 3658–3672 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.