Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease. Triacylglycerol accumulation in the liver is a hallmark of NAFLD. Metabolic studies have confirmed that increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in humans contributes to fat accumulation in the liver and to NAFLD progression. Mice deficient in carboxylesterase (Ces)1d expression are protected from high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis. To investigate whether loss of Ces1d can also mitigate steatosis induced by over-activated DNL, WT and Ces1d-deficient mice were fed a lipogenic high-sucrose diet (HSD). We found that Ces1d-deficient mice were protected from HSD-induced hepatic lipid accumulation. Mechanistically, Ces1d deficiency leads to activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and inhibitory phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Together with our previous demonstration that Ces1d deficiency attenuated high-fat diet-induced steatosis, this study suggests that inhibition of CES1 (the human ortholog of Ces1d) might represent a novel pharmacological target for prevention and treatment of NAFLD.

Keywords: carboxylesterase 1d, liver, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, lipogenesis

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic liver disorder that is increasing in prevalence with the global epidemic of obesity in adults and children (1, 2). Hepatic steatosis results from an imbalance between import, synthesis, utilization, and/or export of lipids. Considerable evidence supports the ability of high-carbohydrate diets to upregulate hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL), leading to increased triacylglycerol (TG) production (3). Over-consumption of simple carbohydrates in processed foods and beverages, especially fructose and sucrose, has been implicated in NAFLD development (4, 5). Metabolites generated during carbohydrate metabolism in the liver serve as substrates for DNL and activate the master transcription factor, carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP), to induce mRNA expression of lipogenic genes, including genes encoding FAS and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) (6).

Our laboratory has investigated the role of carboxylesterases in lipid metabolism, including murine carboxylesterase (Ces)1d [previously annotated as Ces3 and TG hydrolase (TGH)] (7–9). Ces1d was shown to participate in basal lipolysis in adipocytes (10, 11). In the liver, experimental evidence suggests that murine Ces1d and its human ortholog, CES1, participate in the mobilization of preformed TG for VLDL assembly (12–15). Loss of Ces1d enhances insulin sensitivity and protects from high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis by increasing FA oxidation and decreasing hepatic DNL (16). To specifically investigate whether ablation of Ces1d expression can alleviate steatosis induced by over-activated lipogenesis, we challenged Ces1d-deficient mice with a high-sucrose diet (HSD). Here, we show that Ces1d deficiency protects against high-carbohydrate-induced liver lipid accumulation by inhibiting the key lipogenic enzyme, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care and diet studies

All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with protocols approved by the University of Alberta’s Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care policies and regulations. Sixteen-week-old male Ces1d-deficient mice (Ces1d−/−) and WT mice of C57BL/6J background were used in the experiments (16). WT and Ces1d−/− mice were maintained on a 12 h light (7:00 AM to 7:00 PM)/12 h dark (7:00 PM to 7:00 AM) cycle, controlled for temperature and humidity, and were fed either a chow diet (5% fat and 0.02% cholesterol; PicoLab Laboratory Rodent Diet 5L0D) or a HSD (74% kcal from sucrose, fat-free; MP Biomedical, #901683; supplemental Table S1) for 8 weeks. Blood and tissues were collected after 16 h fasting or after 16 h fasting followed by 6 h refeeding.

Metabolic measurements

Energy expenditure and fuel oxidation were assessed using the Oxymax CLAMS (Columbus Instruments). Mice were acclimated in individual chambers for 1 day before data recording. Measurements of in vivo oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were performed every 14 min over 2 days and used to calculate the respiratory exchange ratio (RER). Food intake was monitored during the procedure.

Body composition measurements

Whole-body lean and fat masses were determined in mice by an EchoMRI™ system before and after 8 weeks of HSD feeding.

Plasma and liver chemistries

Enzymatic assays kits were used to measure plasma levels of FFAs, TGs, and ketone bodies (Wako, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma insulin concentration was determined using the Multiplexing LASER Bead Assay (Eve Technologies, Canada). The lipid profile was determined in liver homogenates (1 mg of protein) by GC as previously described (17). Hepatic FA composition and concentration were determined by GC analysis following transesterification of FAs present in total liver lipid extract to FA methyl esters in the presence of 17C-FA as an internal standard (10). Liver glycogen was determined by a glycogen assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Blood gases (pH, HCO3, PCO2) were tested by an i-STAT handheld blood analyzer with EC8+ cartridges (Abbott) (18).

In vivo VLDL-TG secretion

Mice were fasted overnight and then injected intraperitoneally with Poloxamer 407 (1 g/kg body weight). Blood was collected before and 1, 2, and 3 h after injection. TG concentration was determined by a kit assay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany).

Immunoblot analyses

Livers were homogenized in sucrose buffer [250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4)], separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (catalog #IPVH00010; Millipore). Antibodies used in this study include anti-adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) (catalog #2138; Cell Signaling), anti- FAS (catalog #3180; Cell Signaling), anti-SCD1 (catalog #2794; Cell Signaling), anti-perilipin (PLIN)2 (catalog #LS-B7983; LifeSpan BioSciences), anti-PLIN5 (catalog #GP31; PROGEN, Germany), anti-α/β hydrolase domain 5/comparative gene identification-58 (ABHD5/CGI-58) (catalog #12201-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-ATGL (catalog #2138: Cell Signaling), anti-cell death-induced DFF45-like effector (CIDE)B (a gift from Dr. Peng Li, Tsinghua University, China), anti-phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) and AMPK (catalog #2531 and #2532, respectively; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-ACC (p-ACC) and ACC (catalog #3661 and #3662, respectively; Cell Signaling), and anti-phospho-hormone-sensitive lipase (p-HSL) and HSL (catalog #4126 and #4107, respectively; Cell Signaling). Reactivity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and visualized by G:BOX system (SynGene, UK). The relative intensities of the resulting bands on the blots were analyzed by densitometry using the GeneTools program (SynGene).

RNA isolation and real-time qPCR analysis

Total liver RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using Superscript ΙΙΙ reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) primed by oligo (dt)12-18 (Invitrogen) and random primers (Invitrogen). Real-time quantitative (q)PCR was performed with Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix kit (Life Technologies, UK) using the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Canada). Data were analyzed with the StepOne software (Applied Biosystems). Standard curves were used to calculate mRNA abundance relative to that of a control gene, cyclophilin. Real-time qPCR primers are summarized in supplemental Table S2. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Canada).

In vivo lipogenesis

In vivo lipogenesis with acetate as precursor substrate was performed as described before with some modifications (19). In brief, mice fed a HSD for 8 weeks were fasted overnight before refeeding for 6 h; then, 30 μCi of 14C-acetate was intraperitoneally injected into each mouse. Liver and white adipose tissue (WAT) were harvested 1 h after injection. For liver lipid analysis, lipids were extracted from tissues, separated on TLC plates with hexane:isopropyl ether:acetic acid (15:10:1, v/v/v), and visualized by exposure to iodine. Radioactivity in the resolved lipid classes was determined by scintillation counting. For the WAT, radioactivity was measured in the total lipid extracts by scintillation counting.

Glucose tolerance test

Mice were fasted for 16 h prior to oral gavage of glucose (2 g/kg). Plasma levels of glucose were monitored at the indicated time points using glucose strips (Accu-Check glucometer; Roche Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria).

Statistics

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant difference between two groups was determined by unpaired two-tailed t-test. Data from studies in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed on chow diet and HSD were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest (GraphPad PRISM 6 software). Differences were considered statistically significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

RESULTS

Effects of Ces1d deficiency on whole-body metabolism in mice fed HSD

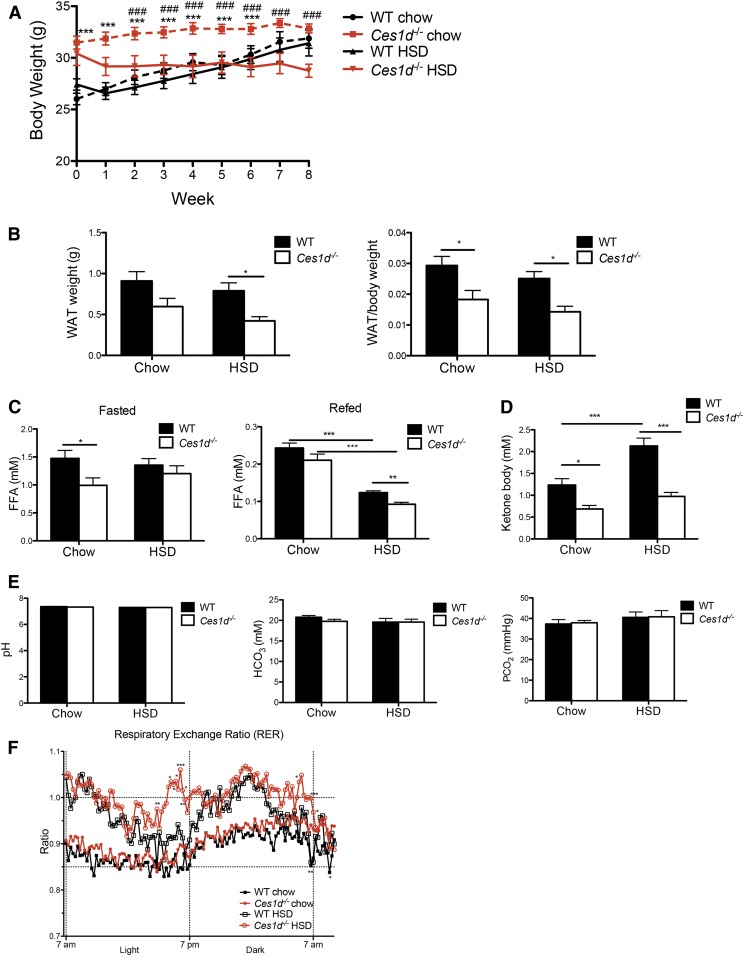

Sixteen-week-old Ces1d−/− and WT mice were fed with HSD or standard chow diet for 8 weeks. WT mice did not show differences in body weight between the chow and HSD feeding conditions (Fig. 1A). Although Ces1d−/− mice trended toward a heavier body weight at the beginning of the diet-feeding period (Fig. 1A), during the 8 weeks of feeding, the body weight increment was blunted in Ces1d−/− mice on both chow diet and HSD. After 8 weeks of feeding, no difference in body weight was observed between Ces1d-deficient and WT mice on either diet (Fig. 1A). The weight gain curve before the initiation of dietary intervention suggests that Ces1d−/− mice fed a regular chow diet reach adult body weight earlier than WT mice during the life phase as mature adults (supplemental Fig. S1A). Ces1d−/− mice fed HSD tended to lose weight compared with the Ces1d−/− mice fed a regular chow diet (Fig. 1A). Ces1d−/− mice had less epididymal WAT weight and/or lower WAT/body weight ratio on both chow diet and HSD (Fig. 1B). MRI scans showed no difference in body composition of fat and lean mass percentage in WT and Ces1d−/− mice before HSD feeding. HSD feeding increased body fat percentage and decreased lean percentage in the WT mice, but this change was not observed in Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S1B, C). These data suggest that the lower weight gain observed in the Ces1d−/− mice could be at least partially derived from decreased WAT depots compared with WT mice.

Fig. 1.

Effects of HSD and Ces1d deficiency on whole body metabolism. A: Body weight of WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. N = 6, values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus WT group on the same diet condition; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P <0.001 versus HSD fed group in the same genotype. B: Epididymal WAT weight and WAT/body weight ratio of WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. C: Plasma FFA concentrations in fasted and refed WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. D: Fasted plasma ketone body concentration in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. E: Blood acid-base measurements after fasting in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow diet or HSD for 8 weeks. N = 6–7, values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. F: RER of WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD. N = 6. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 for significance between groups in the same diet condition.

The 16 h fasting FFA concentration in Ces1d−/− mice either decreased (chow diet) or did not change (HSD) compared with WT control groups (Fig. 1C). Ces1d−/− mice in the HSD group showed reduced plasma FFA concentration in the refed state (Fig. 1C), which could be due to decreased Ces1d-catalyzed basal lipolysis in Ces1d−/− adipocytes (10, 11). Collectively, these data suggest that the decreased fat depot in Ces1d−/− mice fed HSD is not due to increased lipolysis in adipose tissue. Consistent with this observation, plasma ketone body concentration was decreased in the Ces1d−/− mice on both diets (Fig. 1D), reflecting decreased FA utilization. Blood pH, acid, and gases were also monitored in this study, and no difference was observed between genotypes in either diet condition (Fig. 1E), which confirms that the acid-base balance in the blood was not affected by the diets or by the genotype.

Ces1d−/− mice consumed more chow diet than WT mice during the dark phase, but no significant differences were observed in HSD intake between WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S2). As expected, the RER values were elevated in both Ces1d−/− and WT mice after HSD feeding (Fig. 1F), reflecting an increased utilization of carbohydrates as the energy source. Ces1d−/− mice showed increased RER values when fed either the chow diet or the HSD compared with the WT control groups (Fig. 1F), indicating more reliance on carbohydrate over fat as an energy source. There was no difference in energy expenditure between Ces1d−/− and WT mice after HSD feeding (data not shown).

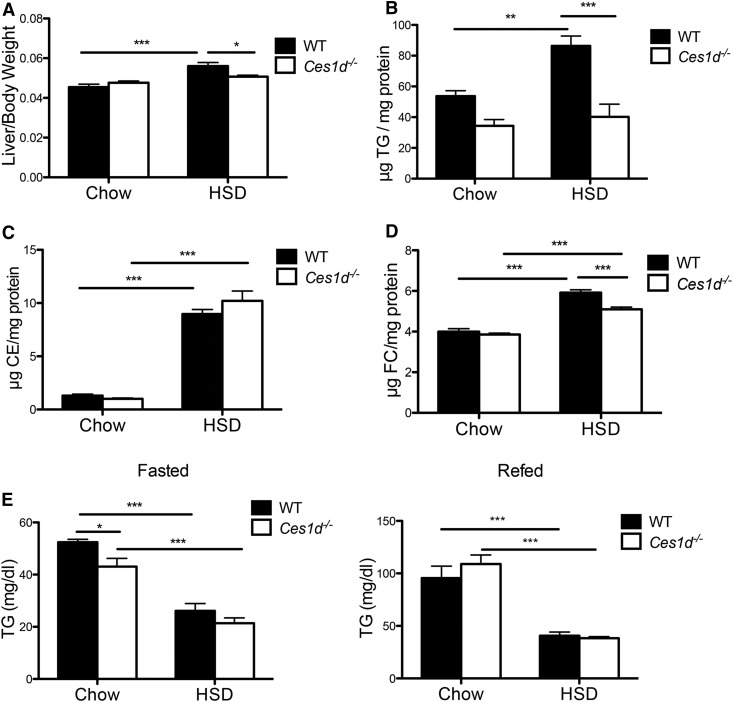

Amelioration of HSD-induced liver lipid accumulation in Ces1d-deficient mice

To determine whether Ces1d deficiency could protect against steatosis induced by DNL, analyses were performed on livers collected after refeeding when DNL is activated. HSD feeding increased liver weight in WT mice but not in Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 2A). As expected, HSD induced an increment in hepatic TG content in WT mice; however, HSD had no effect on hepatic TG content in Ces1d−/− mice, with TG concentrations not differing from chow-fed Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 2B). HSD feeding also increased liver cholesteryl ester (CE) and free cholesterol (FC) concentrations in both WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 2C, D). Liver FC concentration in HSD-fed Ces1d−/− mice was slightly but significantly decreased compared with WT mice (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Ces1d deficiency ameliorated HSD-induced liver lipid accumulation. A: Liver and body weight ratio of WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. Liver TG (B), CE (C), and FC (D) concentrations in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. E: Plasma TG concentrations in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. N = 6, values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Considering that the HSD utilized in this study was a fat-free diet, which could potentially lead to essential FA deficiency, hepatic FA composition in total lipid extract was determined. After 8 weeks of HSD feeding, both WT and Ces1d−/− mice showed a similar decrease in hepatic concentration of linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid, and their long-chain metabolites, arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid (supplemental Fig. S3A–E). Oleic acid that can be synthesized in the liver was increased by HSD feeding in both genotypes, although the increment in Ces1d−/− mice was significantly lower in WT mice (supplemental Fig. S3F), which is consistent with the obtained liver lipid profiles (Fig. 2B) and may be the consequence of attenuated TG synthesis.

HSD feeding slightly increased hepatic mRNA expression of the pro-inflammatory genes, F4/80 and Cd68, but no differences were found between WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S4).

No difference was observed in plasma TG concentration between WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed HSD (Fig. 2E). The VLDL-TG secretion rate was not altered in the four groups of animals (supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that the difference in the liver lipid profile was not caused by altered VLDL secretion.

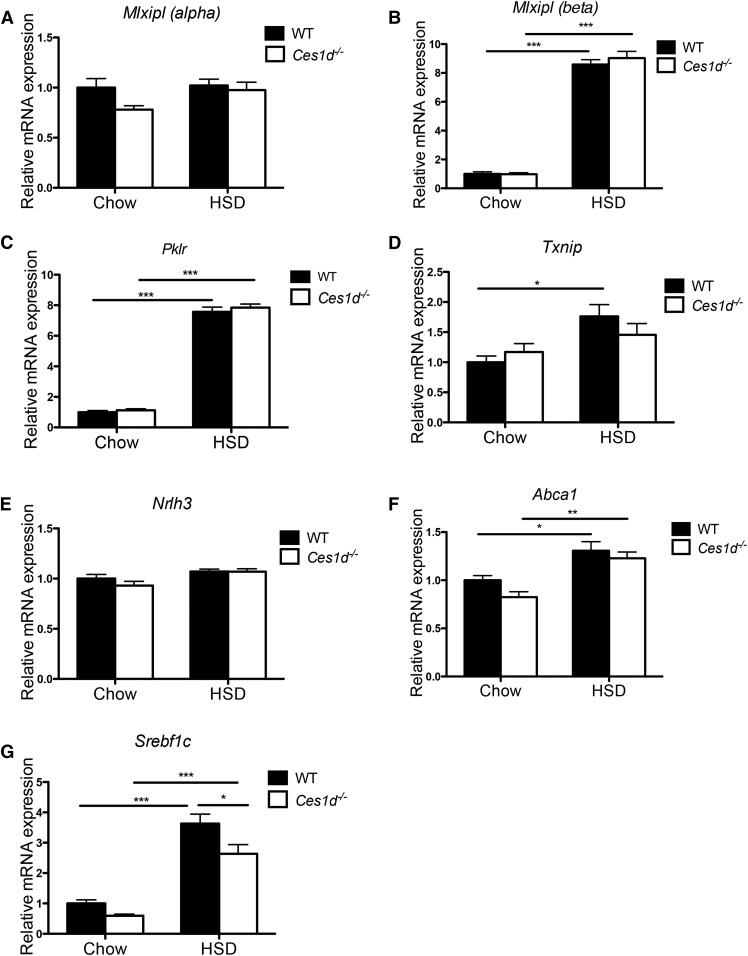

Ces1d deficiency regulates liver lipid metabolism through a posttranscriptional mechanism

ChREBP is activated by carbohydrate metabolites leading to upregulated transcription of genes encoding lipogenic enzymes and consequently increased DNL in the liver (6). Two ChREBP isoforms, ChREBP-α and ChREBP-β, have been characterized. A two-step model has been proposed for ChREBP activation by which carbohydrate-mediated activation of ChREBP-α induces expression of the ChREBP-β isoform (20). In the current study, HSD feeding dramatically increased hepatic expression of Mlxipl (β) encoding the ChREBP-β isoform in both WT and Ces1d−/− mice at a comparable level (Fig. 3A, B). Consequently, hepatic expression of ChREBP target genes, Pklr (encoding liver pyruvate kinase) and Txnip (encoding thioredoxin-interacting protein), were induced in HSD-fed mice with no difference observed between WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 3C, D). These results suggest that ablation of Ces1d expression does not affect the regulation of lipogenic gene expression by hepatic ChREBP.

Fig. 3.

Effects of HSD and Ces1d deficiency on hepatic expression of lipogenic and lipid efflux regulatory genes. Hepatic mRNA expression of Mlxipl (α) (A), Mlxipl (β) (B), ChREBP targets Pklr (C) and Txnip (D), Nrlh3 (E), LXRα target Abca1 (F), and Srebf1c (G) in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks. N = 6. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

LXR increases transcription of lipogenic genes by activating SREBP1c, another important regulatory transcription factor of DNL (21). Glucose and its derivatives were demonstrated to induce LXR transcriptional activity (22, 23). In the present study, the expression of the Nr1h3 gene encoding LXRα was not changed by genotype or diet type (Fig. 3E), while the LXRα target gene, Abca1, was slightly induced by HSD feeding (Fig. 3F), suggesting activation of LXR by over-consumption of sugar. Expression of LXRα target gene, Abca1, was comparable between WT and Ces1d−/− mice on both types of diet, which suggests that the attenuated liver lipid accumulation in Ces1d−/− mice was not due to changes in LXR-mediated transcriptional activity.

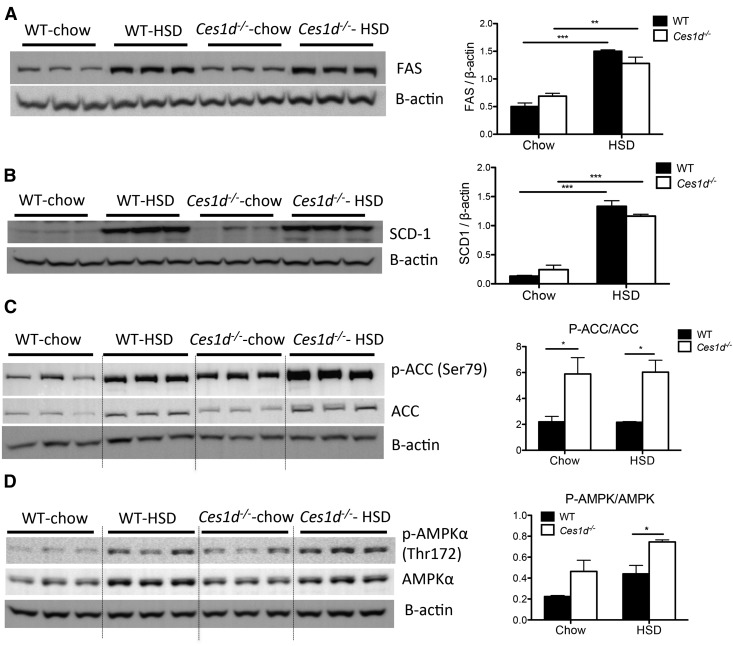

Consistent with previous studies (24, 25), high-carbohydrate diet elevated expression of Srebf1 in the liver of WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 3G). Compared with WT mice, Ces1d−/− mice presented with attenuated Srebf1 expression in the liver. However, the SREBP1c target lipogenic enzymes, FAS and SCD1, did not exhibit different protein abundance between WT and Ces1d−/− groups (Fig. 4A, B). Expression of another key enzyme of lipogenesis, ACC, was induced by HSD feeding to a comparable level in both WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 4C). However, the phosphorylation state of ACC (p-ACC) was significantly higher in Ces1d−/− mice compared with the WT groups in both diet conditions, suggesting suppressed liver ACC activity in Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 4C), which may contribute to the attenuated liver TG accumulation after HSD feeding. It is well-established that AMPK catalyzes ACC phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting ACC activity and DNL (26, 27). In agreement with this canonical regulation, increased phosphorylated state of AMPK (p-AMPK) in the livers of Ces1d−/− mice suggests higher AMPK activity (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Effects of HSD and Ces1d deficiency on regulatory hepatic lipogenic enzymes and AMPK. Abundance of liver FAS (A), SCD1 (B), p-ACC/ACC (C), and p-AMPK/AMPK (D) in chow- or HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice was assessed by immunoblotting. Values of relative band intensities are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

HSD feeding also increased the abundance of SCD1 and ACC, but not FAS, in the WAT. No difference was found between WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S6A, B). Furthermore, p-ACC/ACC and p-AMPK/AMPK ratios also did not change in WAT between WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S6B), suggesting that the effect of Ces1d deficiency on the phosphorylated states of ACC and AMPK is liver specific.

DNL was further assessed by incorporation of [14C]-labeled acetate into lipids in HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice in the refed state. No difference was observed in the incorporation of the radioisotope into TG, CE, and cholesterol in the liver (supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting that lipids synthesized from acetate-derived substrate in the liver are comparable between HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice. The incorporation of acetate into total lipids in WAT also did not vary between HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S6C).

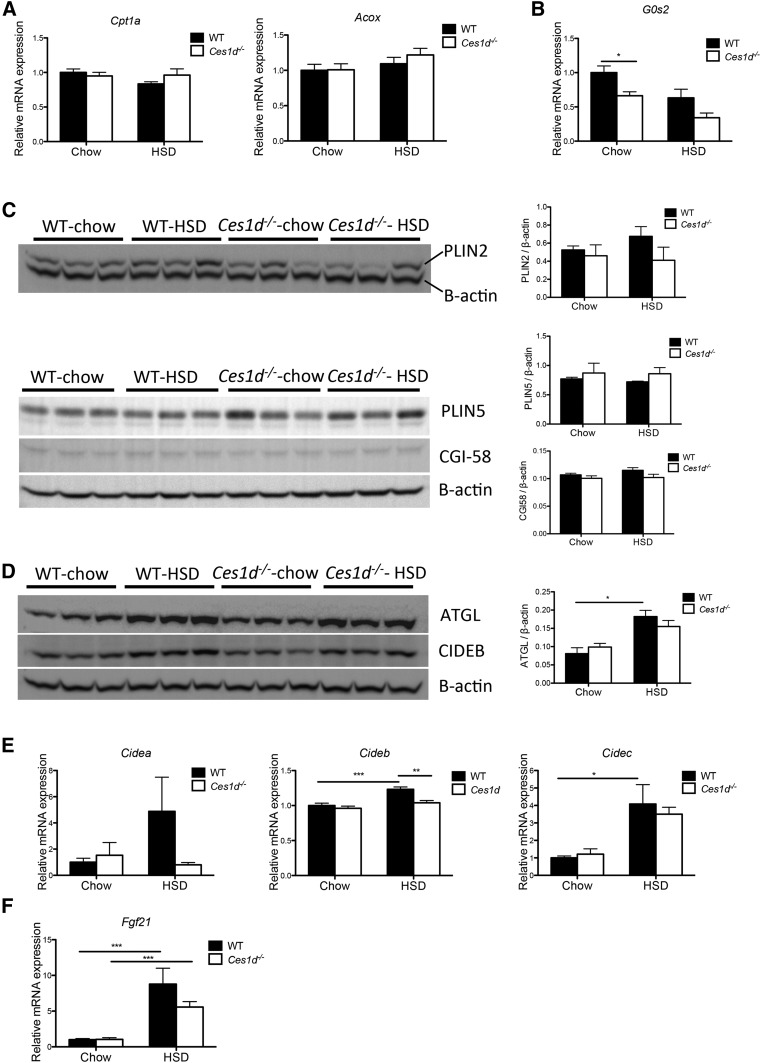

Hepatic expression of FA oxidation-related genes, Cpt1a (encoding carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A) and Acox (encoding acyl-CoA oxidase), did not differ between genotypes or diet types after fasting (Fig. 5A). To investigate whether the attenuated TG accumulation in the liver of Ces1d−/− mice could be attributed to changes in lipid droplet (LD)-associated lipase abundance/activity, hepatic expression of ATGL and its regulators was assessed. The mRNA expression of G0s2, encoding an inhibitor of ATGL (28), was decreased in the livers of Ces1d−/− mice fed chow diet when compared with the WT group on the same diet; however, no significant difference was seen between the two HSD-fed groups (Fig. 5B). It has been demonstrated that LD coat proteins, PLIN2 and PLIN5, block ATGL-mediated lipolysis in the liver (29, 30). PLIN2 and PLIN5 abundance did not differ between the genotypes (Fig. 5C). Abundance of the ATGL coactivator, ABHD5/CGI-58, also did not differ between WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow diet or HSD (Fig. 5C). Similar protein abundance of ATGL was found between WT and Ces1d−/− groups (Fig. 5D). HSL is also involved in liver lipolysis (31), and its activity is elevated by phosphorylation through the PKA pathway and inhibited by dephosphorylation through insulin signaling (32). The phosphorylation state of liver HSL did not differ between HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S8). These results suggest that the attenuation of HSD-induced liver TG accumulation observed in Ces1d−/− mice was independent of cytosolic lipase activity in the liver.

Fig. 5.

Effects of HSD and Ces1d deficiency on regulatory hepatic LD metabolic genes/enzymes. A: Hepatic mRNA expression of genes involved in FA oxidation in fasted WT and Ces1d−/− mice (N = 6). B: Hepatic mRNA expression of ATGL inhibitor, G0s2 (N = 6). C: Protein abundance of PLIN2, PLIN5, and ATGL coactivator CGI-58 in the liver of WT and Ces1d−/− mice was assessed by immunoblotting. D: Protein abundance of ATGL and LD-associated protein. CIDEB. in the liver of WT and Ces1d−/− mice was assessed by immunoblotting. E: Hepatic mRNA expression of LD-associated proteins, CIDEA, CIDEB, and CIDEC (N = 6). F: Hepatic mRNA expression of Fgf21 (N = 6). Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Additional regulators of LD dynamics were investigated. The CIDE protein family, including CIDEA, CIDEB, and CIDEC/Fsp27, was demonstrated to be associated with LDs and to promote LD growth (33). Among the three isoforms, CIDEB is prominently expressed in the liver and intestine (33). CIDEB knockout mice exhibit resistance to high-fat diet-induced steatosis (34). The expression of CIDEA and CIDEC is more abundant in the adipose tissue, while their hepatic expression is induced in fatty liver and positively correlates with the severity of liver steatosis (33, 35, 36). Cidea and Cidec expression levels were variable with Cidea trending toward an increase in livers of HSD-fed WT mice, but not in Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 5E), which could be the result of HSD feeding only inducing mild lipid accumulation in the liver (Fig. 2B). Cideb expression was slightly but significantly induced by HSD in WT mice, whereas Cideb expression in HSD-fed Ces1d−/− mice was reduced compared with WT mice and did not statistically differ from chow-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice (Fig. 5E). A similar protein expression pattern of liver CIDEB among groups was observed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5D).

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), an endocrine hormone produced by liver, plays an important role in the maintenance of lipid and energy homeostasis. Previous studies have demonstrated that hepatic FGF21 expression increases in response to HSD or sucrose challenge (37, 38). HSD elevated expression of Fgf21 in livers of both WT and Ces1d−/− mice with comparable levels (Fig. 5F), suggesting that the changes in energy and lipid metabolism observed in Ces1d−/− mice were not due to regulation by FGF21.

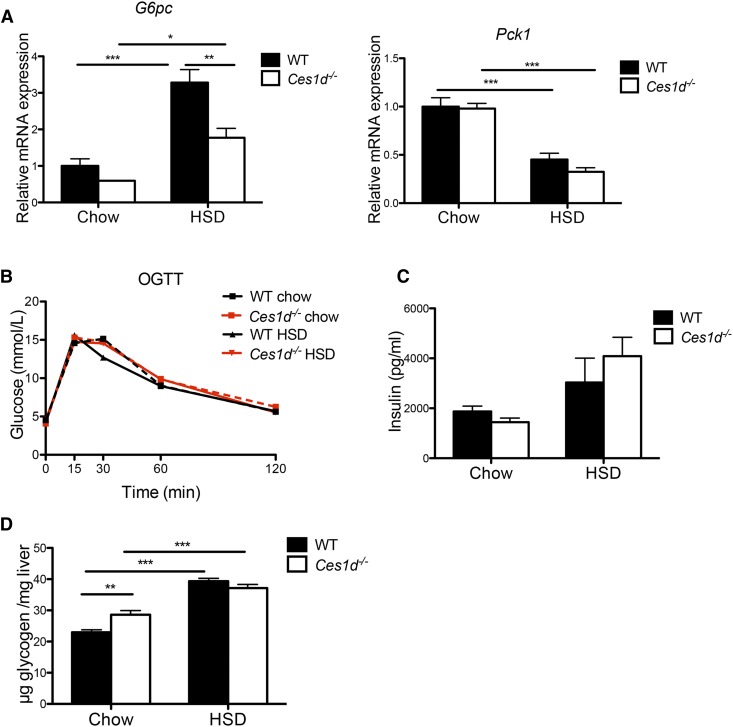

Glucose metabolism in Ces1d-deficient mice fed HSD

Hepatic mRNA expression of key enzymes in gluconeogenesis was determined. Decreased expression of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pc) was found in Ces1d−/− mice fed HSD when compared with the WT control (Fig. 6A). No alterations were observed in the expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1) between genotypes fed either diet (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Effects of HSD and Ces1d deficiency on glucose metabolism. A: Hepatic mRNA expression of key enzymes of gluconeogenesis in WT and Ces1d−/− mice (N = 6). B: Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD (N = 5–8). C: Plasma insulin concentration after refeeding in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks (N = 6). D: Liver glycogen after refeeding in WT and Ces1d−/− mice fed either chow or HSD for 8 weeks (N = 6). Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

No difference in glucose tolerance was detected between WT and Ces1d−/− mice regardless of diet in the oral glucose tolerance test (Fig. 6B). No significant difference was found in plasma insulin levels after refeeding between genotypes (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that the whole-body glucose metabolism in mice fed HSD was not affected by Ces1d deficiency.

Slightly increased hepatic glycogen concentration was observed in Ces1d−/− mice fed chow diet when compared with WT control mice, but no difference was observed between the two HSD-fed groups (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the attenuation of HSD-induced liver TG accumulation in Ces1d−/− mice was not due to a shift of sucrose-derived metabolites from lipid synthesis to glycogen synthesis.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of NAFLD in humans has increased with the rapid rise in carbohydrate consumption (39). The major finding in this study is that Ces1d deficiency prevents HSD-induced liver lipid accumulation in vivo.

DNL is one of the major sources of liver FAs. NAFLD patients present with elevated hepatic DNL, which contributes to hepatic lipid accumulation (40). It is well-documented that over-consumption of a high-carbohydrate diet, in particular simple sugars such as fructose and sucrose, dramatically induces hepatic DNL (41, 42) mainly through over-activation of lipogenesis master regulators, ChREBP (6, 20) and SREBP1c (24, 25), and providing excess substrate for lipogenesis. In the present study, mice lacking Ces1d were protected from HSD feeding-induced liver TG accumulation. This occurred despite activation of both the ChREBP and SREBP1c pathways to a comparable level by HSD feeding in Ces1d-deficient and WT control groups, suggesting that the attenuated hepatic TG accumulation observed in the Ces1d-deficient mice was due to an alternative mechanism. Activities of a number of lipogenic enzymes are regulated by posttranscriptional mechanisms. AMPK has emerged as a key regulator of energy balance and plays an important role in regulating lipid and carbohydrate homeostasis. It has been well-established that AMPK suppresses lipid synthesis through phosphorylation of key enzymes in FA and cholesterol biosynthesis pathways (26, 27, 43, 44). Activation of AMPK inhibits FA synthesis by phosphorylating ACC1 at Ser79 (45). Liver-specific activation of AMPK has been shown to decrease hepatic DNL and protect from high-fructose diet-induced steatosis (46). Increased AMPK activation and ACC1 phosphorylation were observed in Ces1d-deficient mice fed HSD. The mechanism by which AMPK is activated in the livers of Ces1d−/− mice and how it is related to the changes in whole-body metabolism (such as decreased fat deposition and increased RER) remains to be determined.

Despite decreased hepatic lipid concentration in HSD-fed Ces1d−/− mice compared with WT mice, the abundance of the LD-coat protein, PLIN2, was not significantly different. It has been reported that AMPK catalyzes phosphorylation of PLIN2, thereby facilitating association of ATGL to LDs to catalyze lipolysis (47). This mechanism would be consistent with the observed increase in AMPK activation in the livers of Ces1d−/− mice.

Ces1d and its human ortholog, CES1, have been shown to play a role in the regulation of lipid metabolism (48). Ces1d participates in basal lipolysis in adipocytes (10, 11) and in the provision of substrates for the assembly of hepatic VLDL (8). The absence of Ces1d decreases VLDL secretion in vivo but does not cause liver steatosis (49), which may be at least partially attributable to decreased FA flux from adipose tissue to the liver in Ces1d knockout mice (49). Additionally, increased FA oxidation was observed in the Ces1d-deficient hepatocytes and liver-specific Ces1d knockout mice (49, 50), which could also contribute to the prevention of liver lipid accumulation. We demonstrated in our previous study that ablation of Ces1d expression protects mice from high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis by decreasing hepatic DNL, increasing FA oxidation, and enhancing insulin sensitivity (16). Unlike our observations in the HSD-fed Ces1d knockout mice, reduction of lipogenesis in Ces1d−/− mice after high-fat diet feeding was attributable to reduced expression of SREBP1c target enzymes, including SCD1 and ACC, instead of posttranscriptional regulation of the enzyme activity. The distinct mechanisms observed between the two studies could be explained by the different diets used. In the present study, although Srebf1 mRNA abundance was decreased in the HSD-fed Ces1d−/− mice, this change did not diminish the expression of target enzymes, which is likely due to the compensatory over-activation of ChREBP-mediated induction of lipogenic enzymes in the HSD feeding condition. Increased liver FA oxidation was observed in the high-fat diet-fed Ces1d-deficient mice compared with the WT control mice fed the same diet (16). In the high-sucrose fat-free diet-fed Ces1d−/− mice, we did not observe enhanced levels of plasma ketone body concentration and expression of genes involved in FA oxidation in the liver in fasted state, which may be due to decreased FA flux to the liver and a shift toward carbohydrate as the primary energy source identified by the increased RER. Increased utilization of carbohydrates as the energy source in HSD feeding condition may also decrease the availability of substrates derived from carbohydrates for DNL in the liver of Ces1d−/− mice, thus contributing to attenuated lipid synthesis. On the other hand, the decreased FA flux in the circulation may also contribute to reduced lipid storage in the livers of HSD-fed Ces1d−/− mice.

Decreased plasma TG was observed in chow-fed Ces1d−/− mice compared with WT mice under fasted state despite an unchanged rate of VLDL-TG secretion. This is consistent with previous observations in Ces1d−/− mice fed chow diet, suggesting compensatory TG association with apoB48-containing lipoproteins (49, 51). In the current study, HSD feeding decreased plasma TG but did not affect VLDL secretion rate, and no difference was observed between Ces1d−/− and WT mice, suggesting that the difference in liver lipid storage among animal groups was unlikely due to changes in VLDL assembly.

In vivo lipogenesis experiments using labeled acetate as the lipogenic substrate did not show differences in HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice during the refed state, when lipogenesis is most active. However, this result only demonstrates that lipid synthesis from acetate-derived substrate was not changed by Ces1d deficiency. HSD feeding increases acetyl-CoA flux from carbohydrate metabolism to lipogenesis (52). The RER data showed increased carbohydrate utilization in Ces1d−/− mice over FA, which could result in different cytosolic acetyl-CoA pools between HSD-fed WT and Ces1d−/− mice and lead to reduced dilution by endogenous acetyl-CoA and increased acetyl-CoA-specific radioactivity in Ces1d−/− mice. Future studies should consider using other lipogenic substrates that would represent metabolism of carbohydrate.

In conclusion, HSD over-consumption leads to significantly enhanced DNL and lipid accumulation in the liver. Emerging evidence from recent epidemiological and biochemical studies suggests that high dietary intake of carbohydrate is an important causative factor in the development of metabolic syndrome features, including NAFLD. Our data suggest that ablation of Ces1d activity reduces hepatic lipid accumulation, and therefore inhibition of the human ortholog, CES1, might represent a novel pharmacological target for prevention and treatment of NAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Audric Moses (Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Lipidomics Core Facility) for performing lipid analysis by GC, Amy Barr (Cardiovascular Research Centre, University of Alberta) for assistance in the metabolic cage experiments, and Dr. Peng Li (Tsinghua University) for CIDEB antibodies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ABHD5/CGI-58

- α/β hydrolase domain 5/comparative gene identification-58

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATGL

- adipose triglyceride lipase

- CE

- cholesteryl ester

- Ces

- carboxylesterase

- ChREBP

- carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein

- CIDE

- cell death-induced DFF45-like effector

- DNL

- de novo lipogenesis

- FC

- free cholesterol

- FGF21

- fibroblast growth factor 21

- HSD

- high-sucrose diet

- HSL

- hormone-sensitive lipase

- LD

- lipid droplet

- NAFLD

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- p-ACC

- phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- p-AMPK

- phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase

- PLIN

- perilipin

- RER

- respiratory exchange ratio

- SCD1

- stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1

- TG

- triacylglycerol

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grants MOP-69043 and PS 15634. The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedogni G., Miglioli L., Masutti F., Tiribelli C., Marchesini G., and Bellentani S.. 2005. Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology. 42: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younossi Z. M., Koenig A. B., Abdelatif D., Fazel Y., Henry L., and Wymer M.. 2016. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 64: 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kok N., Roberfroid M., and Delzenne N.. 1996. Dietary oligofructose modifies the impact of fructose on hepatic triacylglycerol metabolism. Metabolism. 45: 1547–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikpartow N., Danyliw A. D., Whiting S. J., Lim H., and Vatanparast H.. 2012. Fruit drink consumption is associated with overweight and obesity in Canadian women. Can. J. Public Health. 103: 178–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik V. S., Popkin B. M., Bray G. A., Despres J. P., and Hu F. B.. 2010. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 121: 1356–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdul-Wahed A., Guilmeau S., and Postic C.. 2017. Sweet sixteenth for ChREBP: established roles and future goals. Cell Metab. 26: 324–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehner R., and Verger R.. 1997. Purification and characterization of a porcine liver microsomal triacylglycerol hydrolase. Biochemistry. 36: 1861–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehner R., and Vance D. E.. 1999. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding a hepatic microsomal lipase that mobilizes stored triacylglycerol. Biochem. J. 343: 1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolinsky V. W., Sipione S., Lehner R., and Vance D. E.. 2001. The cloning and expression of a murine triacylglycerol hydrolase cDNA and the structure of its corresponding gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1532: 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei E., Gao W., and Lehner R.. 2007. Attenuation of adipocyte triacylglycerol hydrolase activity decreases basal fatty acid efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 8027–8035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominguez E., Galmozzi A., Chang J. W., Hsu K. L., Pawlak J., Li W., Godio C., Thomas J., Partida D., Niessen S., et al. 2014. Integrated phenotypic and activity-based profiling links Ces3 to obesity and diabetes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10: 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehner R., Cui Z., and Vance D. E.. 1999. Subcellular localization, developmental expression and characterization of a liver triacylglycerol hydrolase. Biochem. J. 338: 761–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolinsky V. W., Douglas D. N., Lehner R., and Vance D. E.. 2004. Regulation of the enzymes of hepatic microsomal triacylglycerol lipolysis and re-esterification by the glucocorticoid dexamethasone. Biochem. J. 378: 967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilham D., Ho S., Rasouli M., Martres P., Vance D. E., and Lehner R.. 2003. Inhibitors of hepatic microsomal triacylglycerol hydrolase decrease very low density lipoprotein secretion. FASEB J. 17: 1685–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilham D., Alam M., Gao W., Vance D. E., and Lehner R.. 2005. Triacylglycerol hydrolase is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum by an unusual retrieval sequence where it participates in VLDL assembly without utilizing VLDL lipids as substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16: 984–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lian J., Wei E., Groenendyk J., Das S. K., Hermansson M., Li L., Watts R., Thiesen A., Oudit G. Y., Michalak M., et al. 2016. Ces3/TGH Deficiency Attenuates Steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 6: 25747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahoo D., Trischuk T. C., Chan T., Drover V. A., Ho S., Chimini G., Agellon L. B., Agnihotri R., Francis G. A., and Lehner R.. 2004. ABCA1-dependent lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I mediates HDL particle formation and decreases VLDL secretion from murine hepatocytes. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan W., Borovac J., Spicer Z., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J., Shull G. E., Doschak M. R., Cordat E., and Alexander R. T.. 2012. The epithelial sodium/proton exchanger, NHE3, is necessary for renal and intestinal calcium (re)absorption. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 302: F943–F956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kita K., Furuse M., Yang S. I., and Okumura J.. 1992. Influence of dietary sorbose on lipogenesis in gold thioglucose-injected obese mice. Int. J. Biochem. 24: 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman M. A., Peroni O. D., Villoria J., Schon M. R., Abumrad N. A., Bluher M., Klein S., and Kahn B. B.. 2012. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose tissue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature. 484: 333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Repa J. J., Liang G., Ou J., Bashmakov Y., Lobaccaro J. M., Shimomura I., Shan B., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., and Mangelsdorf D. J.. 2000. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 14: 2819–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitro N., Mak P. A., Vargas L., Godio C., Hampton E., Molteni V., Kreusch A., and Saez E.. 2007. The nuclear receptor LXR is a glucose sensor. Nature. 445: 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anthonisen E. H., Berven L., Holm S., Nygard M., Nebb H. I., and Gronning-Wang L. M.. 2010. Nuclear receptor liver X receptor is O-GlcNAc-modified in response to glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 1607–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyazaki M., Dobrzyn A., Man W. C., Chu K., Sampath H., Kim H. J., and Ntambi J. M.. 2004. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 gene expression is necessary for fructose-mediated induction of lipogenic gene expression by sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 25164–25171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dentin R., Pegorier J. P., Benhamed F., Foufelle F., Ferre P., Fauveau V., Magnuson M. A., Girard J., and Postic C.. 2004. Hepatic glucokinase is required for the synergistic action of ChREBP and SREBP-1c on glycolytic and lipogenic gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 20314–20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henin N., Vincent M. F., Gruber H. E., and Van den Berghe G.. 1995. Inhibition of fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis by stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase. FASEB J. 9: 541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carling D., Clarke P. R., Zammit V. A., and Hardie D. G.. 1989. Purification and characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase. Copurification of acetyl-CoA carboxylase kinase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase kinase activities. Eur. J. Biochem. 186: 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X., Xie X., Heckmann B. L., Saarinen A. M., Czyzyk T. A., and Liu J.. 2014. Targeted disruption of G0/G1 switch gene 2 enhances adipose lipolysis, alters hepatic energy balance, and alleviates high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis. Diabetes. 63: 934–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C., Zhao Y., Gao X., Li L., Yuan Y., Liu F., Zhang L., Wu J., Hu P., Zhang X., et al. 2015. Perilipin 5 improves hepatic lipotoxicity by inhibiting lipolysis. Hepatology. 61: 870–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaushik S., and Cuervo A. M.. 2015. Degradation of lipid droplet-associated proteins by chaperone-mediated autophagy facilitates lipolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 17: 759–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid B. N., Ables G. P., Otlivanchik O. A., Schoiswohl G., Zechner R., Blaner W. S., Goldberg I. J., Schwabe R. F., Chua S. C. Jr., and Huang L. S.. 2008. Hepatic overexpression of hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase promotes fatty acid oxidation, stimulates direct release of free fatty acids, and ameliorates steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 13087–13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan R. E., Ahmadian M., Jaworski K., Sarkadi-Nagy E., and Sul H. S.. 2007. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 27: 79–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao G., Chen F. J., Zhou L., Su L., Xu D., Xu L., and Li P.. 2017. Control of lipid droplet fusion and growth by CIDE family proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1862: 1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J. Z., Ye J., Xue B., Qi J., Zhang J., Zhou Z., Li Q., Wen Z., and Li P.. 2007. Cideb regulates diet-induced obesity, liver steatosis, and insulin sensitivity by controlling lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. Diabetes. 56: 2523–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou L., Xu L., Ye J., Li D., Wang W., Li X., Wu L., Wang H., Guan F., and Li P.. 2012. Cidea promotes hepatic steatosis by sensing dietary fatty acids. Hepatology. 56: 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langhi C., and Baldan A.. 2015. CIDEC/FSP27 is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and plays a critical role in fasting- and diet-induced hepatosteatosis. Hepatology. 61: 1227–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maekawa R., Seino Y., Ogata H., Murase M., Iida A., Hosokawa K., Joo E., Harada N., Tsunekawa S., Hamada Y., et al. 2017. Chronic high-sucrose diet increases fibroblast growth factor 21 production and energy expenditure in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 49: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Holstein-Rathlou S., BonDurant L. D., Peltekian L., Naber M. C., Yin T. C., Claflin K. E., Urizar A. I., Madsen A. N., Ratner C., Holst B., et al. 2016. FGF21 mediates endocrine control of simple sugar intake and sweet taste preference by the liver. Cell Metab. 23: 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basaranoglu M., Basaranoglu G., and Bugianesi E.. 2015. Carbohydrate intake and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: fructose as a weapon of mass destruction. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 4: 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donnelly K. L., Smith C. I., Schwarzenberg S. J., Jessurun J., Boldt M. D., and Parks E. J.. 2005. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 1343–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarz J. M., Linfoot P., Dare D., and Aghajanian K.. 2003. Hepatic de novo lipogenesis in normoinsulinemic and hyperinsulinemic subjects consuming high-fat, low-carbohydrate and low-fat, high-carbohydrate isoenergetic diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudgins L. C., Seidman C. E., Diakun J., and Hirsch J.. 1998. Human fatty acid synthesis is reduced after the substitution of dietary starch for sugar. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67: 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carling D., Zammit V. A., and Hardie D. G.. 1987. A common bicyclic protein kinase cascade inactivates the regulatory enzymes of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 223: 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato R., Goldstein J. L., and Brown M. S.. 1993. Replacement of serine-871 of hamster 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase prevents phosphorylation by AMP-activated kinase and blocks inhibition of sterol synthesis induced by ATP depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90: 9261–9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott J. W., Norman D. G., Hawley S. A., Kontogiannis L., and Hardie D. G.. 2002. Protein kinase substrate recognition studied using the recombinant catalytic domain of AMP-activated protein kinase and a model substrate. J. Mol. Biol. 317: 309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woods A., Williams J. R., Muckett P. J., Mayer F. V., Liljevald M., Bohlooly Y. M., and Carling D.. 2017. Liver-specific activation of AMPK prevents steatosis on a high-fructose diet. Cell Reports. 18: 3043–3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaushik S., and Cuervo A. M.. 2016. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of lipid droplet protein PLIN2 triggers its degradation by CMA. Autophagy. 12: 432–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lian J., Nelson R., and Lehner R.. 2018. Carboxylesterases in lipid metabolism: from mouse to human. Protein Cell. 9: 178–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei E., Ben Ali Y., Lyon J., Wang H., Nelson R., Dolinsky V. W., Dyck J. R., Mitchell G., Korbutt G. S., and Lehner R.. 2010. Loss of TGH/Ces3 in mice decreases blood lipids, improves glucose tolerance, and increases energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 11: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lian J., Wei E., Wang S. P., Quiroga A. D., Li L., Pardo A. D., van der Veen J., Sipione S., Mitchell G. A., and Lehner R.. 2012. Liver specific inactivation of carboxylesterase 3/triacylglycerol hydrolase decreases blood lipids without causing severe steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 56: 2154–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lian J., Bahitham W., Panigrahi R., Nelson R., Li L., Watts R., Thiesen A., Lemieux M. J., and Lehner R.. 2018. Genetic variation in human carboxylesterase CES1 confers resistance to hepatic steatosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1863: 688–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferramosca A., Conte A., Damiano F., Siculella L., and Zara V.. 2014. Differential effects of high-carbohydrate and high-fat diets on hepatic lipogenesis in rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 53: 1103–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.