Abstract

Background

Peer support provides the opportunity for peers with experiential knowledge of a mental illness to give emotional, appraisal and informational assistance to current service users, and is becoming an important recovery‐oriented approach in healthcare for people with mental illness.

Objectives

To assess the effects of peer‐support interventions for people with schizophrenia or other serious mental disorders, compared to standard care or other supportive or psychosocial interventions not from peers.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials on 27 July 2016 and 4 July 2017. There were no limitations regarding language, date, document type or publication status.

Selection criteria

We selected all randomised controlled clinical studies involving people diagnosed with schizophrenia or other related serious mental illness that compared peer support to standard care or other psychosocial interventions and that did not involve 'peer' individual/group(s). We included studies that met our inclusion criteria and reported useable data. Our primary outcomes were service use and global state (relapse).

Data collection and analysis

The authors of this review complied with the Cochrane recommended standard of conduct for data screening and collection. Two review authors independently screened the studies, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion until the authors reached a consensus. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for binary data, and the mean difference and its 95% CI for continuous data. We used a random‐effects model for analyses. We assessed the quality of evidence and created a 'Summary of findings' table using the GRADE approach.

Main results

This review included 13 studies with 2479 participants. All included studies compared peer support in addition to standard care with standard care alone. We had significant concern regarding risk of bias of included studies as over half had an unclear risk of bias for the majority of the risk domains (i.e. random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, attrition and selective reporting). Additional concerns regarding blinding of participants and outcome assessment, attrition and selective reporting were especially serious, as about a quarter of the included studies were at high risk of bias for these domains.

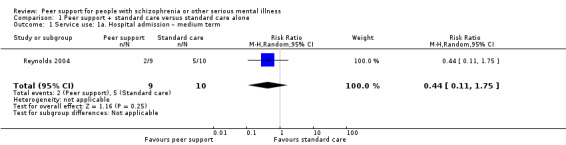

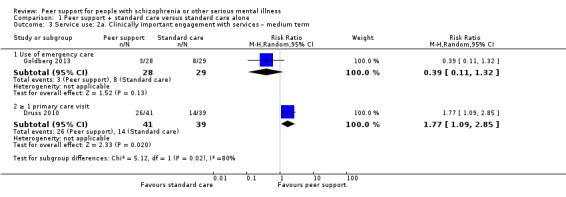

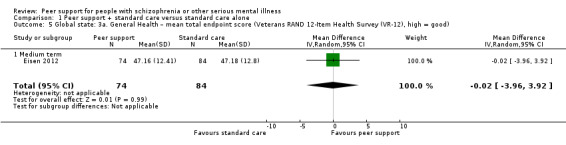

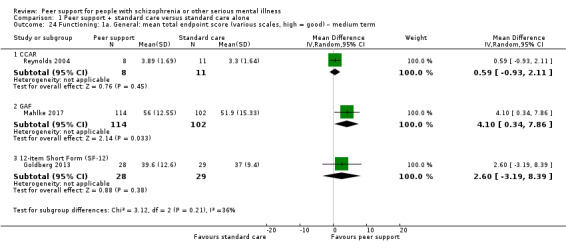

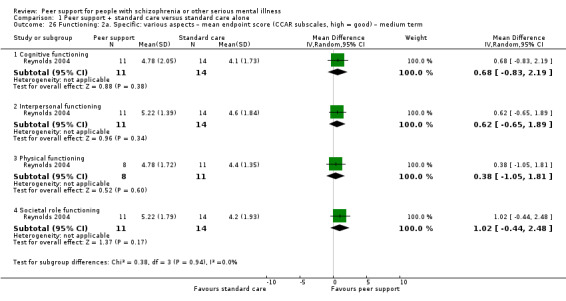

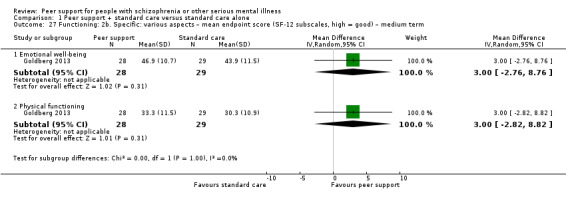

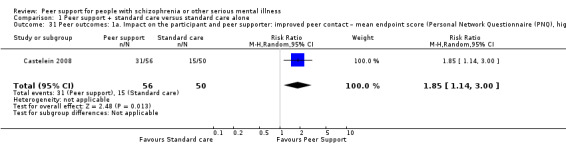

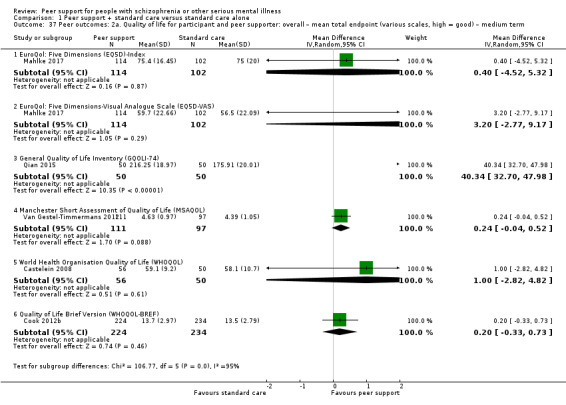

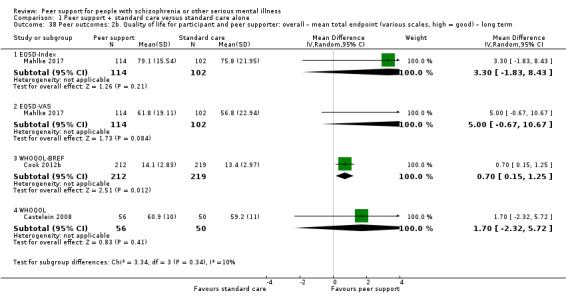

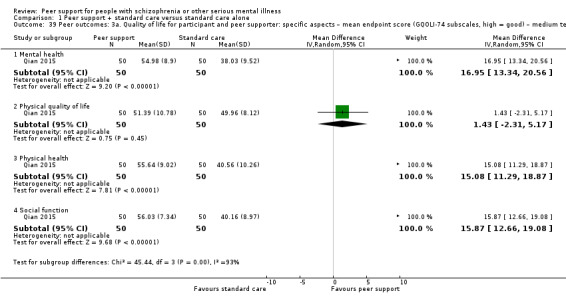

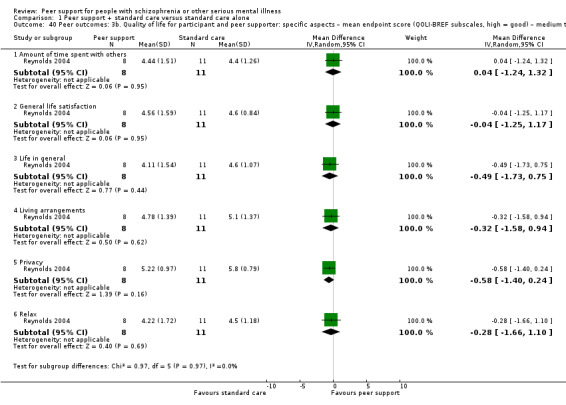

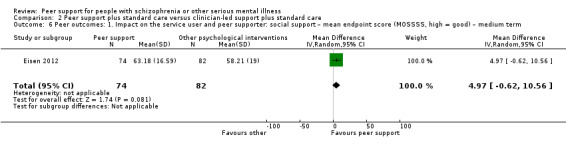

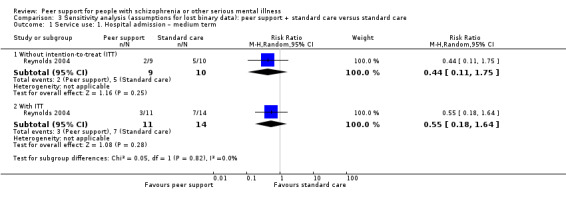

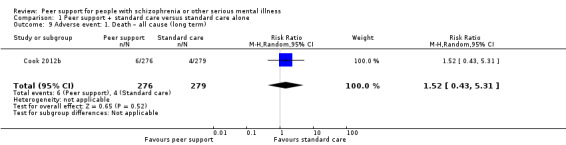

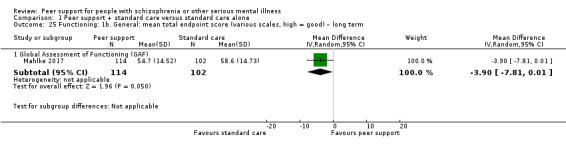

All included studies provided useable data for analyses but only two trials provided useable data for two of our main outcomes of interest, and there were no data for one of our primary outcomes, relapse. Peer support appeared to have little or no effect on hospital admission at medium term (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.75; participants = 19; studies = 1, very low‐quality evidence) or all‐cause death in the long term (RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.43 to 5.31; participants = 555; studies = 1, very low‐quality evidence). There were no useable data for our other prespecified important outcomes: days in hospital, clinically important change in global state (improvement), clinically important change in quality of life for peer supporter and service user, or increased cost to society.

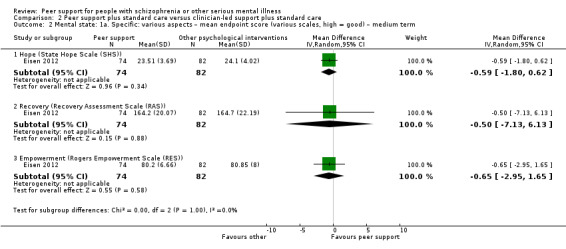

One trial compared peer support with clinician‐led support but did not report any useable data for the above main outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, very limited data are available for the effects of peer support for people with schizophrenia. The risk of bias within trials is of concern and we were unable to use the majority of data reported in the included trials. In addition, the few that were available, were of very low quality. The current body of evidence is insufficient to either refute or support the use of peer‐support interventions for people with schizophrenia and other mental illness.

Plain language summary

Peer support for schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses

Background

Schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses are chronic disruptive mental disorders with disturbing psychotic, affective and cognitive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, depression, anxiety, insomnia, difficulty in concentration, suspiciousness and social withdrawal. The primary treatment is antipsychotic medicine, but these are not always fully effective.

Peer support provides the opportunity for both a service user and a provider of care to share knowledge, direct experience of their illness and to help each other along the path to recovery. The support is given alongside antipsychotic treatment. Through interpersonal sharing, modelling and assistance within or outside of group sessions, it is believed that these supportive strategies can help combat feelings of hopelessness and behavioural problems that may result from having an illness and empower people to continue their treatment and help them to resume key roles in real life. However, findings from research have been inconsistent regarding the effectiveness of peer support for people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses.

Review aims

This review aimed to find high‐quality evidence from relevant randomised clinical trials (studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) so we could assess the effects of peer‐support interventions for people with serious mental illness in comparison to standard care or other supportive or psychosocial interventions not from peers. We were interested in finding clinically meaningful data that could provide information regarding the effect peer support has on hospital admission, relapse, global state, quality of life, death and cost to society for people with schizophrenia.

Searches

We searched Cochrane Schizophrenia's specialised register of trials (up to 2017) and found 13 trials that randomised 2479 people with schizophrenia or other similar serious mental illnesses to receive either peer support plus their standard care, clinician‐led support plus their standard care or standard care alone.

Key results

Thirteen trials were available but the evidence was very low quality. Useable data were reported for only two of our prespecified outcomes of importance and showed adding peer support to standard care appeared to have little or no clear impact on hospital admission or death for people with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. One of these trials (participants = 156) also compared peer support with clinician‐led support (where a health professional provided support). However, there were no useable data for this comparison reported for the main outcomes.

Conclusions

We have little confidence in the above findings. Currently, there is no high‐quality evidence available to either support or refute the effectiveness of peer‐support interventions for people with schizophrenia or other serious mental illnesses.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The definition of serious mental illness with the widest consensus is that of the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Schinnar 1990), and is based on diagnosis, duration and disability (NIMH 1987). People with serious mental illness have conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which last over a protracted period resulting in the erosion of functioning in day‐to‐day life. Schizophrenia is a chronic, disruptive, mental illness that frequently contributes to a wide variety of functional disabilities, especially within social and occupational domains (Harvey 2012). The worldwide estimate for the life‐time prevalence of schizophrenia ranges from 1.4 per 1000 people to 4.6 per 1000 people; the annual incidence rate lies between 0.16 per 1000 people and 0.42 per 1000 people, with onset often occurring in adolescence and early adulthood (Jablensky 2000). The psychopathology of schizophrenia is often described in terms of the severity of positive (e.g. hallucinations and disorganised speech) and negative (e.g. blunted affect and social withdrawal) symptoms. While antipsychotic medications remain the core treatment for controlling the symptoms of schizophrenia, they are associated with a range of undesirable adverse effects on cardiovascular, endocrine and other bodily systems, resulting in poor treatment adherence (Kane 2010).

About 30% of people with schizophrenia have persistent and severe negative symptoms that tend to be resistant to medication. Termed 'deficit syndrome', persistent negative symptoms are characterised by lack of initiative, interests and social fluency; poor verbal communication and concentration; and loss of interpersonal function (Nasrallah 2011; Tandon 2009). Together with progressive deterioration in various cognitive functions (e.g. problems in working memory and information processing, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition), there are considerable and wide varieties of functional impairments which can severely compromise overall psychosocial functioning, social integration and quality of life (Mohamed 2008). These factors may all eventually reduce treatment efficacy in people with schizophrenia.

The total societal costs of schizophrenia, including treatment, rehabilitation, community care services and loss of productivity, were estimated at more than USD 60 billion per annum in the USA, UK and other high‐income countries in the 20th century (Mangalore 2007; Wu 2005). People with schizophrenia have severe social and occupational disability (30%) and are at higher risks of other mental health (e.g. 25% to 30% have depression) and physical health (e.g. 20% to 25% have cardiovascular disease) problems (De Hert 2009), have a two‐ to three‐times higher all‐cause mortality rate and are 12 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population (Goff 2005; Wildqust 2010).

Description of the intervention

Peer support is broadly defined as "a system of giving and receiving help founded on key principles of respect, shared responsibility, and mutual agreement of what is helpful" (Mead 2001). Dennis 2003 defined 'peer support' within a healthcare context as ".... the provision of emotional, appraisal and informational assistance by a created social network member who possesses experiential knowledge of a specific behaviour or stressor and similar characteristics as the target population" (Dennis 2003). Peers can be referred to those people who share common characteristics with a specific individual or group, affiliating and empathising with and supporting each other to promote health and deal with life problems. The emphasis is on the idea that 'peers' are considered to be equal (Dennis 2003); in contrast to the traditional healthcare system of mental health services, which distinguishes between providers (i.e. trained professionals) and consumers (e.g. people with schizophrenia and families/friends), peer‐support programmes are built on collaborative, mutual and equal partnerships of participants who share their experiences (or expertise) in different stages of recovery (Repper 2010).

Peer‐support programmes for people with schizophrenia are mainly classified into two main categories, according to how they run the services and the roles played by their co‐ordinators or facilitators (Ahmed 2012).

One type of peer support programme is the mutual/self‐help group led by professionals/clinicians. The group members have similar life issues or situations such as care giving to a chronically ill relative. The clinician or professional facilitates the group members to come together for sharing and establishing coping strategies, feeling more empowered and obtaining a sense of community. The clinician or professional acts as a facilitator to assist the group members to get help during the process of relating personal experiences, listening to and accepting others' experiences, providing sympathetic understanding and establishing social networks.

The other type of peer support programme is the consumer‐led programme, in which consumers provide supportive services to other patients and their families and offer advice to the mental healthcare team. The consumer‐led service is a more structured programme in terms of its system, structure and group sessions. It involves consumers more with leadership of the co‐ordinators or facilitators, or both. The consumers are often peer volunteers or the peer specialists who are employed in the healthcare setting to advocate for other consumers.

However, both categories of peer‐support programme emphasise interactive mutual peer or social learning. In response to individual groups' and group members' needs, their content can range from psychoeducation about schizophrenia and its symptom management, medication adherence, stress reduction and coping strategies, to problem‐solving approaches, and the strengthening of family and community support resources, as well as vocational and social skills training (Chien 2009).

How the intervention might work

Peer support has become an increasingly important strategy in healthcare systems that are encountering limited manpower and resources on one the hand and, on the other hand, continuously increasing costs of managing complex and chronic illnesses such as severe mental disorders (Bradstreet 2010). Peer support has been widely used to improve physical and psychosocial health and enhance behavioural change and self‐care in diverse chronic conditions, as well as in population groups in need of support (Cheah 2001). A peer‐support programme can provide a platform where fellow patients and those already recovered or on their way to recovery from schizophrenia, or another mental illness, can share their individual experiences of the illness and management strategies in everyday life in a way that is not commonly offered in traditional healthcare settings where mental‐health professionals may often dominate services (Chien 2009). In contrast to traditional healthcare settings, often stigmatised by the general public, the environment of a peer‐support group fosters a sense of emotional support, information exchange, companionship, reassurance and appraisals among group members (Ahmed 2012; Dennis 2003). Through interpersonal sharing, modelling and assistance within or outside of group sessions, it is believed that these supportive strategies can effectively combat hopelessness and behavioural problems relating to mental illness and specifically schizophrenia, and empower participants to continue treatment and resume key roles in real life (Chien 2009; Davidson 1999). However, research has shown inconsistent findings on whether social or peer support enhances self‐care ability and medication adherence in people with mental illness (Pistrang 2008), and other chronic illnesses such as diabetic mellitus (Toljamo 2001).

While most peer‐support groups mainly target those who are in the early stages of recovery, the benefits of these group programmes are not limited only to those who receive the peer‐support service, but also extend to those who provide peer support to others (Miyamoto 2012). The peer‐support providers who are assigned the roles of co‐ordinator or facilitator of the group can successfully rebuild their self‐efficacy through having the chance to serve other people with similar conditions. They may even collaborate with professionals to deliver appropriate services to other group members in need. Through active participation in service provision, they themselves increase their knowledge of disease management and enhance various skills that are important to daily functioning (Arnstein 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

Systematic reviews and practice guidelines have recommended that, in adjunction to psychopharmacological treatment, psychosocial interventions designed to support people with schizophrenia and their families should also be used to improve the person's rehabilitation, reintegration into the community and recovery from the illness (NICE 2009; Pharoah 2010). There is now an increasing body of evidence concerning the effects of a range of psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia, including psychoeducation (Xia 2011), cognitive‐behavioural therapy (Morrison 2009; Turkington 2004), and family intervention (Pharoah 2010). While psychosocial interventions have indicated significant positive effects on reducing relapse and readmission rates, and enhancing medication compliance, most have not demonstrated consistent and conclusive results in improving psychosocial health conditions of people with schizophrenia. Moreover, research has shown inconsistent findings on whether social or peer support enhances self‐care ability and medication adherence in people with mental illness (Pistrang 2008), and other chronic illnesses such as diabetic mellitus (Toljamo 2001). Therefore, the design or testing of alternative approaches to psychosocial intervention for these people should be considered. Guided by the consumer movement and recovery model in mental health care, peer support is one such approach to psychosocial intervention that places emphasis on promoting the overall wellness and empowerment of people with schizophrenia through establishing partnerships between those with the condition throughout the whole journey of recovery (Ahmed 2012).

With its emphasis on the experiences of people with schizophrenia, their needs and perspectives in treatment planning, peer‐support programmes have led to growing interest in the role that those who are experiencing difficulties with recovery can play in enlightening the social reintegration and enhancing the rehabilitation process of others with similar mental health problems (Ahmed 2012). The number of peer‐support programmes for schizophrenia care has increased rapidly in high‐income countries such as the USA and Canada.(REF) Nevertheless, there is no systematic review on the impetus for this alternative treatment approach and its effects on mental condition; relapse; medication adherence; and a wide variety of outcomes such as psychosocial and occupational functioning, social skills, self‐efficacy, overall wellness and quality of life in people with schizophrenia (Miyamoto 2012).

This review focused on peer‐support programmes and their use varies across cultures. There are no systematic reviews on this topic in the area of schizophrenia and only a few reviews have been published on the effects of support groups for various kinds of mental health problems (e.g. LIoyd‐Evans 2014; Pistrang 2008). The findings of this review will enhance our knowledge of the effectiveness of peer‐support interventions and the various models for the delivery of peer‐support interventions across cultures. The costs and benefits of these programmes can then be systematically evaluated.

Objectives

To assess the effects of peer‐support interventions for people with schizophrenia or other serious mental disorders, compared to standard care or other supportive or psychosocial interventions not from peers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster randomised trials, that evaluated the effects of peer support for people with schizophrenia or similar serious mental illness. We excluded studies that did not include a control or comparison group. Where the participants were given additional types of treatments within peer support, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was applied equally to all study groups and it was only peer support that was randomised and allocated to the treatment or intervention group(s).

If a trial had been described as 'double blind' but only implied randomisation, we would have included such trials in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating participants by alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We required:

the majority of participants to be aged 18 to 65 years;

the majority of participants to have a serious mental illness preferably as defined by NIMH criteria (NIMH 1987), but, in the absence of that, from illness such as schizophrenia, schizophrenia‐like disorders, bipolar disorder or serious affective disorders;

if a trial included participants with a range of serious mental illnesses we included it only if at least 20% of the participants had schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like disorders.

We did not consider substance abuse to be a serious mental illness in its own right; however, studies were eligible if they dealt with people with both diagnoses (i.e. those with serious mental illnesses plus substance abuse). Dementia and mental retardation are not considered to be a serious mental disorder, hence we excluded studies focusing on these populations. Despite the fact that personality disorder was now included in the NIMH definition of serious mental illnesses, we excluded this from our review on the basis that the diagnosis of personality disorders had low inter‐rater reliability (Zimmerman 1994), the duration of treatment can be assessed much more precisely than duration of illness (Schinnar 1990), and that insufficient information was given on how to diagnose disability criterion in both the original NIMH definition (NIMH 1987), and in the further work of Schinnar 1990.

Types of interventions

1. Intervention

1.1 Peer support

We defined a 'peer' as someone selected to provide support because they had similar or relevant health experience (Dale 2008). See also Description of the intervention.

2. Comparators

2.1 Standard care

Care that a participant would normally receive in the area in which the trial took place. This normally includes biological, psychological and social approaches to care including antipsychotic medication, and utilisation of services including hospital stay, day hospital attendance and community psychiatric nursing involvement.

2.2 Other psychosocial intervention

Any psychosocial intervention or any supportive intervention (e.g. cognitive‐behavioural therapy, psychoeducation programmes, family interventions, social skills training programmes) that did not involve a 'peer' individual/group(s).

Types of outcome measures

We divided outcomes into short term (up to one month), medium term (one or more to six months) and long term (more than six months).

Primary outcomes

1. Service use

1.1 Hospital admission 1.2 Duration of hospital stay (days)

2. Global state

2.1 Relapse – as defined by each of the studies 2.2 Clinically important change in global state (e.g. improved/not improved to an important extent) – as defined by each of the studies

3. Adverse event

3.1 Death: all cause

Secondary outcomes

1. Service use

1.1 Clinically important engagement with all services 1.2 Any contact with services 1.3 Any contact with specialist community services (i.e. early intervention teams, assertive outreach teams and crisis teams) 1.4 Time to hospitalisation

2. Global state

2.1 Any change in global state (improved/not improved) – as defined by each of the studies 2.2 Mean change or endpoint score on global state scale 2.3 Time to relapse 2.4 Compliance with treatment

3. Mental state

3.1 Overall

3.1.1 Clinically important change in overall mental state (improved/not improved to an important extent) – as defined by each of the studies 3.1.2 Any change in mental state (improved/not improved) – as defined by each of the studies 3.1.3 Mean endpoint or change score on mental state scale

3.2 Specific

3.2.1 Clinically important change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive, negative, affective) – as defined by each of the studies 3.2.2 Any change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive, negative, affective) – as defined by each of the studies 3.2.3 Mean endpoint or change score on specific mental state scale

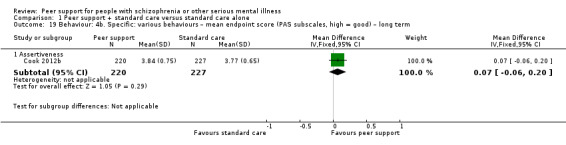

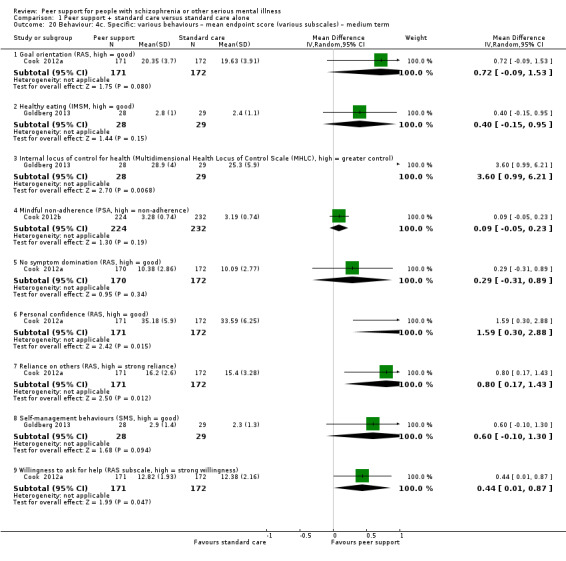

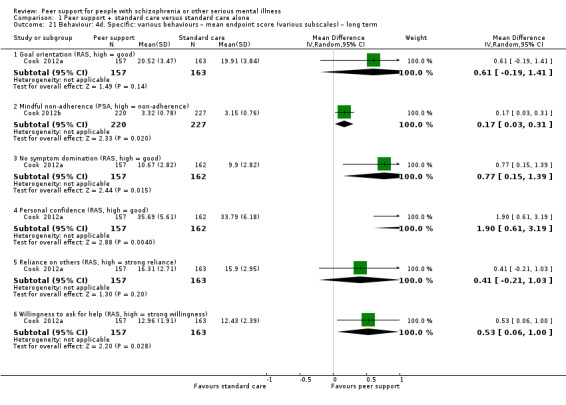

4. Behaviour

4.1 General

4.1.1 Clinically important change in general behaviour – as defined by each study 4.1.2 Any change in general behaviour – as defined by each study 4.1.3 Mean endpoint or change score on general behaviour scale

4.2 Specific

4.1.1 Clinically important change in specific behaviour (e.g. aggression) – as defined by each study 4.1.2 Any change in specific behaviour – as defined by each study 4.1.3 Mean endpoint or change score on specific behaviour scale

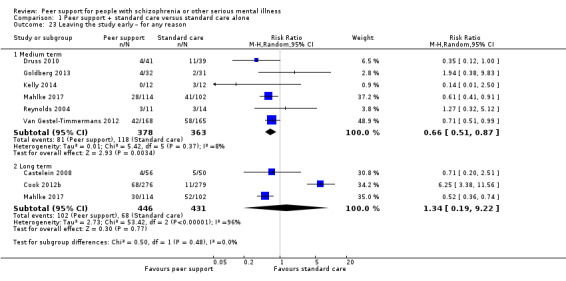

5. Leaving the study early

5.1 For any reason 5.2 For specific reason

6. Functioning

6.1 General

6.1.1 Clinically important change in general functioning – as defined by each study 6.1.2 Any change in general functioning – as defined by each study 6.1.3 Mean endpoint or change score on general functioning scale

6.2 Specific (e.g. social, cognitive, psychological, life skills)

6.2.1 Clinically important change in specific functioning – as defined by each study 6.2.2 Any change in specific functioning – as defined by each study 6.2.3 Mean endpoint or change score on specific functioning scales 6.2.4 Employment status or work‐related activities 6.2.5 Independent living 6.2.6 Imprisonment/contact with police/justice system

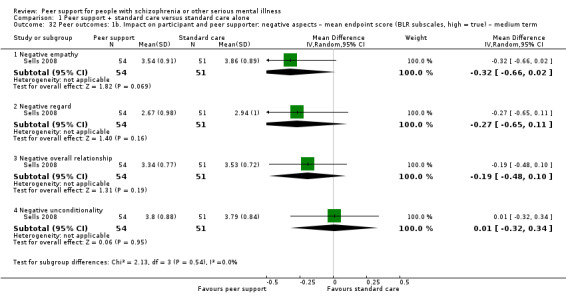

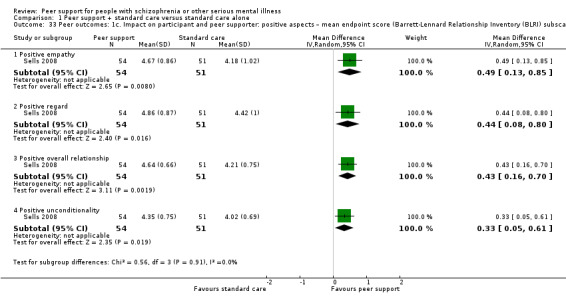

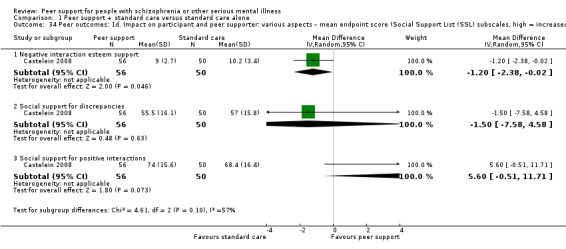

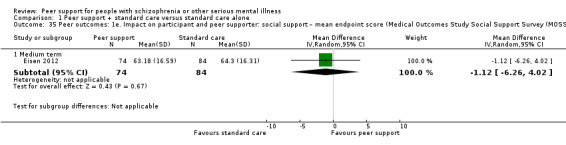

7. Peer outcomes

7.1 Impact on the service user and peer supporter (e.g. anxiety and perceived social support) 7.2 Coping ability/self‐efficacy of service user and peer supporter 7.3 Expressed emotion of family, peer supporter or both

7.4 Quality of life for service user and peer supporter

7.4.1 Clinically important change in quality of life for service user and peer supporter

7.4.2 Any change in quality of life for service user and peer supporter

7.4.3 Mean endpoint or change score on quality of life scale

7.5 Satisfaction with care for service user and peer supporter

7.5.1 Clinically important change in satisfaction of life for service user and peer supporter

7.5.2 Any change in satisfaction for service user and peer supporter

7.5.3 Mean endpoint or change score on satisfaction scale

8. Adverse effects

8.1 General adverse effects

8.1.1 At least one adverse effect 8.1.2 Any incidence of clinically important adverse effect 8.1.3 Mean endpoint or change score on adverse effect scale

8.2 Specific adverse effects

8.2.1 Incidence of various specific effects

9. Economic outcomes

9.1 Cost of care 9.2 Direct costs 9.3 Indirect costs

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and GRADEpro GDT to export data from our review to create the 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provided outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to the care of people with schizophrenia and to decision making. We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Service use: hospital admission.

Service use: duration of hospital stay (days).

Global state: relapse – as defined by each of the studies.

Global state: clinically important change in global state.

Adverse events: death – all cause.

Peer outcomes: clinically important change in quality of life for service user and peer supporter.

Economic outcomes: indirect costs (increased cost to society).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 27 July 2016 and 4 July 2017, the information specialist searched the register using the following search strategy which were developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

(*Peer* OR *Self‐Help* OR *Social Support* OR *Social Network*) in Intervention Field of STUDY

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature and conference proceedings (see Group's Module). There is no language, date, document type or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register. See Appendix 1 for previous search terms.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials. However, no unpublished trial was identified through this method.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SL, WTC) screened the results of the electronic search, a third review author (AC) checked the screening. WTC inspected all abstracts of studies identified through screening and identify potentially relevant reports. Once identified, to ensure reliability, AC inspected a random sample of these abstracts, comprising 10% of the total. Where disagreement occurred, we resolved this by discussion, and where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. We then requested the full articles of relevant reports for reassessment and carefully inspect them for a final decision on inclusion. Two review authors (WTC, SL) independently inspected all full reports and decided whether they met the inclusion criteria. We were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions or journal of publication. Where difficulties or disputes arose, we asked one review author (AC) for help; if it was impossible to decide, we added these studies to those awaiting assessment and contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Two review authors (SL, WTC) independently extracted data from included studies. We discussed any disagreement, documented our decisions and, if necessary, we contacted the authors of studies for clarification. We had planned to extract data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but would have only included such data only if two review authors independently reached the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request to obtain any missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. Where applicable, we extracted data relevant to each component centre of multi‐centre studies separately (see the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Module).

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, predesigned simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and

the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should have either been a self‐report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realised that this is not often reported clearly; we noted if this is the case or not in the Description of studies section.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data: change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis; however, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) that can be difficult to obtain in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We have decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former are not available. If necessary, we will combine endpoint and change data in the analysis, as we prefer to use mean differences (MDs) rather than standardised mean differences (SMDs) throughout (Deeks 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to relevant continuous data before inclusion.

For endpoint data from studies including fewer than 200 participants:

when a scale started from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divide this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value was lower than one, it strongly suggested that the data were skewed and we would have excluded these data. If this ratio was higher than one but less than two, there was suggestion that the data were skewed: we would have entered these data and tested whether their inclusion or exclusion would change the results substantially. If such data changed results, we would have entered them as 'other data'. Finally, if the ratio was larger than two, we would have included these data, because it was less likely that they were skewed (Altman 1996);

if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210 (Kay 1986)), we would have modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases, skewed data were present if 2 SD > (S − Smin), where S was the mean score and Smin was the minimum score.

Note: we would have entered all relevant data from studies of more than 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the above rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We would also have entered all relevant change data, as when continuous data were presented on a scale that included a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it was difficult to determine whether or not data were skewed.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables that could have been reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This was done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It was generally assumed that if there was a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for peer support. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'not improved') we reported data in such a way that the area to the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome. This was noted in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SL, AVC) independently assessed risk of bias using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011a). This set of criteria was based on evidence of associations between an overestimation of effect and high risk of bias in an article, such as due to sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies to request further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment but, if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated to, again resolution was made by discussion. We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It was shown that the RR was more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than the odds ratio, and that odds ratios tended to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The number required to treat for an additional harmful outcome statistic with its 95% CI was intuitively attractive to clinicians but was problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and its interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, we calculated illustrative comparative risks where possible.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated MD and its 95% CI between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference). However, if scales of very considerable similarity had been used, we would have presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and would have calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employed 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data posed problems. First, authors often failed to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992), whereby P values were spuriously low, CI unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This caused type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, using a symbol (*) to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error (Table 3). We would have contacted first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for their clustered data and if authors replied, adjusted for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

1. Details of peer‐support intervention in each included study.

| Study ID | Peer‐support intervention | ||

| Treatment duration | Who delivered/led the intervention | Element of peer support | |

| Castelein 2008 | 8 months | People with schizophrenia or related psychotic disorder | Guided peer support group; participants decided the topic of each session; each session had the same structure discussing daily life experiences in pairs; it is to provide peer‐to‐peer interaction. |

| Cook 2012a | 8 weeks | Peer instructors | Peer‐led, mental illness education intervention called Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES). Classes were delivered interactive, and included group discussion, illustrative anecdotes and structured exercises designed to apply information to everyday situations. Course topics included recovery principles and stages, strategies for building interpersonal and community support systems, brain biology and psychiatric medications, diagnoses and related symptom complexes, traditional and non‐traditional treatments and relapse prevention and coping skills. |

| Cook 2012b | 8 weeks | Peer instructors | Peer‐led illness self‐management intervention called Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP). Course work included lectures, group discussions, personal examples from the lives of the educators and participants, individual and group exercises, and voluntary homework assignments. Session 1: introduction of key concepts of WRAP; session 2 and 3: development of personalised wellness strategies; session 4: introduction of a daily maintenance plan to use every day to stay emotionally and physically healthy; session 5: educating of early warning signs; session 6 and 7: creation of a crisis plan specifying signs of impending crisis, names of individuals willing to help, and types of assistance preferred; session 8: post crisis support. |

| Druss 2010 | 6 sessions | Peer specialists | 6 group sessions led by peer specialists, the following topics were discussed: overview of self‐management; exercise and physical activity; pain and fatigue management; healthy eating on a limited budget; medication management; finding and working with a regular doctor. |

| Eisen 2012 | 12 weeks | Peer facilitators | Peer facilitators used written recovery material such as the Spanior Recovery Workbook available from the Boston University. Peer leaders also shared their personal experiences as veterans with mental illness. |

| Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012 | |||

| Goldberg 2013 | 13 weeks | People with mental illness | Living well group; the first 3 sessions of the living well intervention focus on the basic strategies of self‐management; the remaining weekly sessions focus on training in specific disease management techniques and skills. |

| Kelly 2014 | 6 months | People with mental illness | Manualised intervention. Navigators encouraged development of self‐management of healthcare through a series of psychoeducation and behavioural strategies. |

| Mahlke 2017 | 6 months | People with mental illness | 1‐to‐1 peer support in addition to standard care. Peer supporters contacted patients within the first week after randomisation and then established 1‐to‐1 meetings. The minimum number of meetings required to build a supporting relationship and be effective for the patient, based on the experiences in delivering support by the peers themselves. |

| Qian 2015 | 5 weeks | People with mental illness | Peer support and psychoeducation. |

| Reynolds 2004 | 5 months | People with mental illness | The transitional discharge model; this peer support provided friendship, understanding and encouragement for the discharged patient. |

| Rowe 2007 | 4 months | People with mental illness | Citizenship intervention plus valued‐roles projects. Consist of classes with topics related to social participation and community integration (citizenship classes), followed by projects designed to foster participants' acquisition of valued social roles (valued‐roles projects). |

| Sells 2008 | 12 months | Peer providers | Peer‐based group; use past experiences with recovery as a tool for understanding, role modelling and hope building for others. |

| Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012 | 12 weeks | People with mental illness | Each session had the same structure and was organised around a specific, recovery‐related theme, such as the meaning of recovery to participants, personal experiences of recovery, personal desires for the future, making choices, goal setting, participation in society, roles in daily life, personal values, how to get social support, abilities and personal resources, and empowerment and assertiveness. |

We have sought statistical advice and been advised that binary data presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This can be calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC (design effect = 1 + (m – 1) * ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC had not been reported, it would be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed, taking into account ICC and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. This occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological or physiological) of the treatment in the first phase of a trial is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase, participants differ systematically from their initial state in spite of a washout phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are also not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects were very likely in severe mental illness, we would only have used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons where relevant. If data were binary, we simply added these and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not use these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). For any particular outcome, if more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. However, if more than 50% of data in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by downgrading quality. Finally, we would have downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' tables should data loss have been 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In cases where the attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50%, and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis). Participants leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcomes of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of those who stayed in the study – in that particular arm of the trial – was used for those who did not. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data from only people who completed the study to that point were compared to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In cases where the attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If SD were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and CI available for group means, and either a P value or t value available for differences in mean, we calculated SD according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). When only the SE was reported, SD would have been calculated using the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Sections 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Intervention presented detailed formulae for estimating SD from P values, t or F values, CI, ranges or other statistics s (Higgins 2011b). If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SD according to a validated imputation method which was based on the SD of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would had been to exclude a given study's outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless would have examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data have been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we would have presented and used these data, and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions. Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers; others use the method of LOCF; while more recently, methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences between groups in their reasons for doing so is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. Therefore, we would not have excluded studies based on the statistical approach used. However, by preference we would have used the more sophisticated approaches, that is, we preferred to use MMRM or multiple‐imputation to LOCF, and we would have only presented completer analyses if some type of ITT data were not available. Moreover, we would have addressed this issue in the item 'Incomplete outcome data' of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparative data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted would arise. When such situations or participant groups arose, we discussed these in the text.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparative data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arose, we discussed these in the text.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic method alongside the Chi2 statistic P value. The I2 statistic provided an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of the I2 statistic depends on magnitude and direction of effects; and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi2 test, or a CI for the I2 statistic). I2 statistic estimates of 50% or greater, accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic (P < 0.1), were interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). When there were substantial levels of heterogeneity in the primary outcomes, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011).

1. Protocol versus full study

We tried to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size. In other cases, where funnel plots are possible, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understood that there was no closed argument regarding a preference for the use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporated an assumption that the different studies were estimating different yet related intervention effects. To us, this often seemed to be true and the random‐effects model took into account differences between studies even if there was no statistically significant heterogeneity. There was, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model as it put added weight onto small studies, which were often those most biased. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose a random‐effects model for analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Clinical state, stage or problem

We aimed to provide an overview of the effects of peer support for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, however, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in similar clinical state and stage, and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, this was reported. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, the graph was visually inspected, and outlying studies was successively removed to see whether homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that, should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, data were presented. If not, issues were discussed. We knew of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but were investigating the use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we would have included these studies; and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with a better description of randomisation, we would have used all relevant data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we implemented our assumptions, or when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. If there was a substantial difference, we would have reported and discussed the results but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs (see Dealing with missing data), we would have compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we implemented our assumptions, or when we used data only from people who completed the study to that point. A sensitivity analysis would have been undertaken to test how prone the results were to change when completer‐only data were compared with the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we would have reported and discussed the results but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we used relevant data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for the ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster randomised trials. If there were substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we would not have pooled data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but would have presented them separately.

5. Fixed and random effects

We synthesised data using a random‐effects model. However, we also synthesised data for the primary outcomes using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether the greater weights assigned to larger trials with greater event rates altered the significance of the results, compared with the more evenly distributed weights in the random‐effects model. If we had found differences, we would have reported them.

6. At least 20% of participants with schizophrenia and unclear proportion of people with schizophrenia

We intended to included studies where at least 20% of the participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like disorders in a sensitivity analyses. If a paper had not reported the proportion of various diagnoses, we would have included it, but conducted a sensitivity analysis to test whether such a trial would influence the pooled results of primary outcomes. If inclusion did influence the results, we would not have included this trial but presented it separately.

Results

Description of studies

For a substantive description of studies, see the Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

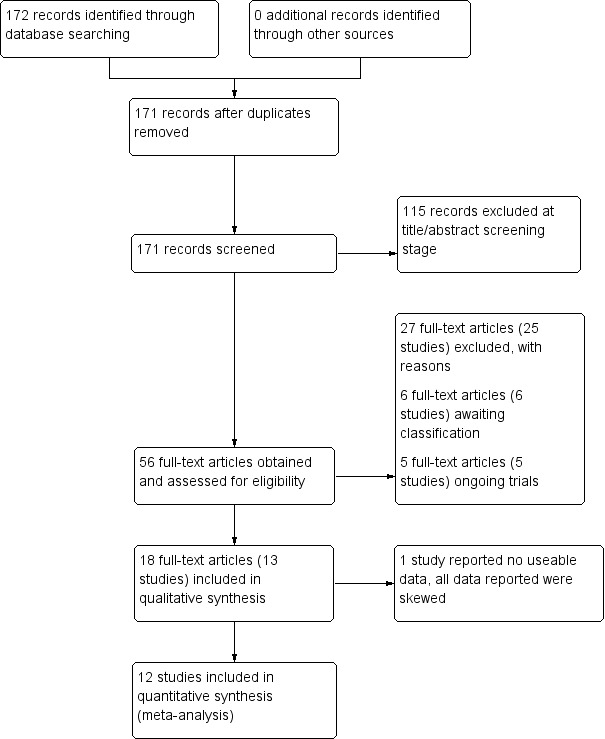

The electronic search (4 July 2017) yielded 172 records of potentially eligible studies, after removal of duplicates, we screened 171 records. After checking titles and abstracts, we excluded 115 records and obtained 56 full‐text papers for a second assessment. These publications consisted of 13 included studies with 18 references (Castelein 2008; Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Eisen 2012; Goldberg 2013; Kelly 2014; Mahlke 2017; Qian 2015; Reynolds 2004; Rowe 2007; Sells 2008; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012), 25 excluded studies with 27 references (Buchkremer 1995; Chen 2016; Chinman 2015; Corrigan 2017a; Corrigan 2017b; Craig 2004; Forchuk 2005; Gunter 1983; Hazell 2016; ISRCTN14282228; Kaplan 2011; Kaufmann 1995; Killackey 2013; Klein 1998; NCT02974400; O'Connell 2017; Rivera 2007; Rogers 2012; Salyers 2010; Segal 2010; Shahar 2006; Streicker 1984; Verhaegh 2006; Weissman 2005; Zhou 2016), six studies waiting classification (Robinson 2010; Daumit 2010; Kroon 2011; NCT00458094; NTR1166; Tondora 2010), and five ongoing studies (ACTRN1261200097; Chinman 2017; NCT01566513; NCT02958007; NCT02989805). We contacted authors of the following studies: Castelein 2008, Chinman 2015, Eisen 2012, Goldberg 2013, O'Connell 2017, Salyers 2010, Weissman 2005, and ACTRN1261200097 to clarify some obscure information. See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

This review included 13 studies with 2479 participants. Comprehensive details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1. Design

1.1 Duration

The duration of the studies ranged from five weeks (Qian 2015) to 12 months (Mahlke 2017; Rowe 2007; Sells 2008). In seven studies, the study durations were medium term (one to six months) (Druss 2010; Eisen 2012; Goldberg 2013; Kelly 2014; Qian 2015; Reynolds 2004; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012). The other studies were long term (longer than six months).

1.2 Unit of analysis

One study had three treatment groups (Eisen 2012). None of the studies were cross‐over or cluster RCTs. The remaining studies were parallel randomised trials with two arms.

2. Participants

2.1 Age

All studies recruited adults (aged over 18 years). One study reported an age range between 30 and 60 years (Eisen 2012). Eleven studies reported the mean ages of participants, which were between 25.23 and 49.5 years. One study did not report ages of participants (Reynolds 2004).

2.2 Sex

Around half of the participants in the trials were men (1160/2479; 46.8%). Reynolds 2004 did not report gender of participants.

2.3 Diagnosis

Twelve studies recruited participants with a range of serious mental illness including bipolar disorder, major depression, depressive disorder, alcohol‐use disorder, drug‐use disorder, mood disorder or other disorders, but more than 20% of participants in these studies were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like disorders. One study recruited only participants with schizophrenia (Qian 2015).

2.4 Exclusion criteria

Reported exclusion criteria of participants included: people aged less than 18 years old (Castelein 2008); people with drug or alcohol (or both) dependency or substance abuse (Castelein 2008; Mahlke 2017; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012); possible language difficulties (Castelein 2008; Mahlke 2017; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012); suicidal ideation (Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012); severe psychotic symptoms or not being psychiatrically stable (Castelein 2008; Qian 2015; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012); unable to give informed consent or be hospitalised at start of the study (Kelly 2014); and people with dementia (Reynolds 2004). Other studies did not report the exclusion criteria (Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Eisen 2012; Goldberg 2013; Rowe 2007; Sells 2008). For other details, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.5 Duration of illness

Five studies reported the duration of the illness (Castelein 2008; Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Mahlke 2017; Qian 2015), which ranged from 12 months to 13 years (Qian 2015). Other studies did not report the duration of illness.

2.6 Setting

Two studies recruited 323 participants from hospitals (Eisen 2012; Reynolds 2004), in which one study recruited participants from Veterans Hospital (Eisen 2012). The participants in Reynolds 2004 had been discharged from an inpatient facility. Four studies involved 1126 outpatients recruited from mental healthcare centres/administrations (Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Goldberg 2013). Qian 2015 recruited their participants from community settings. Participants in Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012 and Mahlke 2017 were a mix of inpatients from hospital and outpatients from psychiatric care services and mental healthcare providers. The other four studies did not report the setting for participants (Castelein 2008; Kelly 2014; Rowe 2007; Sells 2008).

2.7 Country

Participants were recruited from Netherlands (439 participants) (Castelein 2008; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012), USA (1699 participants) (Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Eisen 2012; Goldberg 2013; Kelly 2014; Rowe 2007; Sells 2008;), UK (25 participants) (Reynolds 2004), Germany (216 participants) (Mahlke 2017), and China (100 participants) (Qian 2015).

3. Interventions

Of the 13 included studies, all compared peer support in addition to standard care versus standard care alone. For some of these studies, participants in the control group were assigned to a 'waiting‐list' where they received standard care (Castelein 2008; Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a). Standard care in all included studies referred to continuation of the participants' usual medical or mental healthcare services. One study involved three arms in which they compared peer support with clinician support and with standard care separately (Eisen 2012). Details of studies are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table and the details of peer‐support interventions are listed in Table 3.

4. Outcomes

4.1 General

Data were reported for service use, global state, mental state, behaviour, leaving the study early, functioning, peer outcomes, quality of life and economics. Details of scales used by the included trials to measure outcomes are given below.

4.2 Scales providing useable data

4.2.1 Global state scales

Veterans RAND 12‐Item Health Survey (VR‐12) (Kazis 2017)

VR‐12 assesses physical and mental health status rated on a 5‐point response scale, ranging from 1, none of the time, to 5, all of the time. Total score ranges from 12 to 60 with higher score indicating better health status.

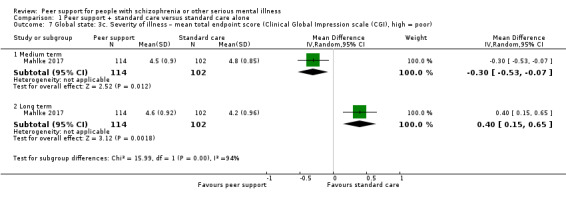

Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI) (Busner 2007)

This a three‐item scale used to measure the global severity and improvement of illness condition with two items (severity and improvement index) rated on a 7‐point scale and one item (efficacy index) rated on a 4‐pont scale. A higher score in severity and improvement indicates higher severity or more worsening of the clinical condition.

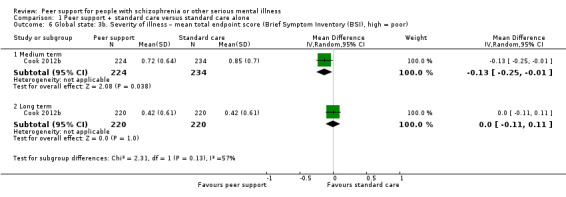

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (self‐reported) (Derogatis 1993)

The BSI's Global Severity Index is designed to quantify a patient's severity of illness and provides a single composite score for measuring the outcome of a treatment programme based on reducing symptom severity. Respondents are asked how much they were bothered in the past week by 53 symptoms with a 5‐point response scale ranging from 'not at all' to 'extremely'.

4.2.2 Mental state scales

Rogers Empowerment Scale (RES) (Rogers 1997)

The RES comprises 28 items encompassing self‐efficacy, self‐esteem, perceived power, community activism, righteous anger and optimism. The scores range from 28 to 112 with high score indicating more empowerment.

Dutch Empowerment Scale (DES) (Boevink 2009)

Th DES consists of 40 items with a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree.

State Hope Scale (SHS) (Snyder 1991)

The SHS is an instrument designed to measure hope as a cross‐situational long‐term trait in general populations. Twelve items are rated on a 4‐point response scale ranging from 'definitely false' to 'definitely true' and summed to produce a total score. Two subscales measure belief in one's capacity to initiate and sustain actions (agency) and ability to generate routes by which goals may be reached (pathways).

Herth Hope Index (HHI) (Herth 1992)

The HHI consists of 12 items rated on a 4‐point linked scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 4, strongly agree. The total score ranges from 12 to 48 with higher score indicating high level of hope.

Rosenberg Scale (RS) (Rosenberg 1965)

The RS is used to assess self‐esteem and has two subscales: positive and negative self‐esteem. The total score ranges from 10 to 40 with higher score indicating higher level of self‐esteem.

4.2.3 Behaviour scales

Patient Activation Scale (PAS) (Hibbard 2004)

The PAS reflects an person's perceived ability to manage his or her illness and to act as an effective patient. It includes two subscales: activation levels and approach to health care. Higher scores reflect greater activation. This construct is measured using the 13‐item Patient Activation Measure and is calculated on a 0 to 100 score, with 100 as the highest possible degree of activation.

Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (Giffort 1995)

The RAS comprises 41 items rated on a 5‐point scale from 'strongly agree' to 'strongly disagree', the RAS conceptualises recovery along multiple components. In addition to a total score, subscales measure personal confidence, willingness to ask for help, goal orientation, reliance on others and having tolerable levels of symptoms.

Instrument to Measure Self‐Management (IMSM) (Lorig 1996)

The IMSM includes six subscales: healthy eating, physical activity, accessing social support, behavioural and cognitive symptom management, making better use of health care and general self‐management behaviours. The subscale scores range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater frequency.

Brashers' Patient‐Self‐Advocacy Scale (PSA, self‐reported) (Brashers 1999)

The Brashers' PSA is an instrument designed to measure a person's propensity to engage in self‐activism during healthcare encounters. The study employs the 18‐item instrument in which statements are rated on a 5‐point response scale ranging from 'strongly agree' to 'strongly disagree', and meaned to produce a total score and three subscale scores.

Self‐Management/Self‐Efficacy Scale (SMSES) (self‐reported) (Lorig 1996)

The SMSES is an 18‐item scale and includes six subscales: healthy eating, physical activity, accessing social support, behavioural and cognitive symptom management, making better use of health care (including preparing questions for medical providers to discuss medication concerns) and general self‐management behaviours (use of action planning, brainstorming and problem solving). Items are scored on a Likert scale reflecting frequency; scores range from 1, never, to 5, always.

Mental Health Confidence Scale (MHCS) (Carpinello 2000)

The MHCS is used to assess self‐efficacy and is a 16‐item scale with three factors: optimism, coping and advocacy. The sum of the items provides the total score, ranging from 16 to 96 with higher scores indicating more empowerment.

General Self‐Efficacy Scale (GSE) (Schwarzer 1995)

The GSE is a 10‐item psychometric scale that is designed to assess optimistic self‐beliefs to cope with a variety of difficult demands in life. Higher score indicates better self‐efficacy.

4.2.4 Functioning

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Aas 2010)

The GAF scale is used to rate how serious the mental illness affects a person's day‐to‐day life functioning on a scale of 0 to 100. Scores range from 1, severely impaired, to 100, extremely high functioning, with higher score indicating better functioning in daily activities.

Colorado Client Assessment Record (CCAR) (Ellis 1984)

The CCAR is used for people with chronic mental illness and programme evaluation. It measures cognitive, social and role function, which is frequently impaired by chronic mental illness in diverse psychiatric diagnostic groups.

Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐12) (Ware 1996)

The 12‐item Short‐Form Health Survey is used to assess general health functioning, physical functioning and emotional well‐being. Higher scores indicated better functioning. Possible subscale scores range from 0 to 100. The SF‐36 was also used to measure health‐related quality of life (McHorney 1993).

4.2.5 Peer support scales

Personal Network Questionnaire (PNQ, self‐reported) (Castelein 2008)

The PNQ is used to measure the size and content of the social network asking for information on the frequency of contacts with named family, friends and members of the peer support group.

Barrett‐Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLRI, self‐reported) (Barrettlennard 1962)

The BLRI is a 64‐item client questionnaire designed to gauge dimensions of the client–provider relationship relevant to favourable therapeutic change. Respondents rate agreement with items on a 6‐point scale, ranging from 1, definitely false, to 6, definitely true.

The Social Support List (SSL) (Bridges 2002)

The SSL measures positive social interactions and discrepancies between the support people want and what they actually receive. The SSL consisted of six subscales: everyday emotional support, emotional support with problems, esteem support, instrumental support, social companionship and informative support. The total score for positive interactions ranged from 34 to 136 and the total score for discrepancies ranged from 34 to 201. HIgher scores on interaction indicated more support. Higher scores on discrepancy indicated a greater deficit in desired support. The 'negative interactions' on a 7‐item subscale ranged from 7 to 32 with higher scores indicating more negative interaction.

The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOSSSS) (Sherbourne 1991)

The MOSSSS includes 19 items measuring emotional and informational support, tangible support, affectionate support and positive social interaction.

4.2.6 Quality of life scales

EuroQol: Five Dimensions (EQ5D)/EQ‐VAS (Balestroni 2012)

The EQ5D is a standardised instrument developed by the EuroQol group as a measure of health‐related quality of life in different health conditions. It consists of a descriptive system of health status and EQ‐VAS (0 to 100). The descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, rating on a 3‐level response scale from 3, no problem, to 1, extreme problem. The EQ‐VAS identifies one's self‐rated health on a vertical, visual analogue scale (VAS) with the endpoints from 100, the best imaginable health state, to 0, the worst imaginable health state; and a higher score indicates better health status.

General Quality of Life Inventory (GQOLI) (this scale is in data analyses but not described here) (Li 1997)

The GQOLI measures the perceived quality of life of people with different health conditions (Li 1997). This scale consists of 74 items, assessing four dimensions of quality of life: physical health, psychological health, social functioning and living conditions. Each item is rated on a 5‐point scale, with high score indicating a better quality of life.

Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MSAQOL)

Quality of life is assessed with 12 subjective items of the MSAQOL (Priebe 1999). The items use a 7‐point Likert scale, from 1, could not be worse, to 7, could not be better. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) (WHOQOL Group 1998)

The WHOQOL is a widely used quality of life instrument, with 100 items measuring four domains of well‐being: physical, psychological, social and environment. Two additional items focus on the overall 'quality of life' and 'general health'. Scores on these four domains and the additional items can be combined to create an overall score of quality of life (ranging from 18 to 90). Higher scores indicating higher quality of life.

WHOQOL‐BREF has been modified from the WHOQOL (WHOQOL Group 1998) to provide a short‐form quality of life assessment with 26 items measuring four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environment, one item measuring overall quality of life, and another item measuring general health. The items use a 5‐point Likert scale, from 1, not at all/very poor/very dissatisfied/never, to 5, completely/very good/very satisfied/extremely. Possible score range from 0 to 100 for each domain, with higher scores indicating high quality of life.

Quality of Life Brief Version (QOLI‐BREF) (Lehman 1994)

QOLI‐BREF is derived from the QOLI‐Full Version and measures both objective quality of life (what people do and experience) and subjective quality of life (what people feel about these experiences). It consists of 45 items, measuring eight domains: living situation, daily activities and functioning, family relations, social relations, finances, work and school, legal and safety issues, and health. Higher scores indicating higher quality of life.

4.3 Other scales

Other scales were used to measure outcomes but data reported from these scales were skewed and we could not use in data analyses.

Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (Mclellan 1980)

The ASI is a structured interview to assess the degree of potential treatment barriers across domains typically affected by alcohol‐ and drug‐use disorders. Higher score indicates greater problem.

Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS‐24) (Cameron 2007)

The revised 24‐item BASIS assesses depression and functioning, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, self‐ham, emotional lability, psychotic symptoms, substance abuse and overall mental health. The score ranges from 0 to 4, with higher values indicating greater symptom severity.

Loneliness scale (Jonggierveld 1985)

The Loneliness Scale consists of 11 items with a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1, yes, for sure, to 5, no, certainly not.

Studies awaiting classification

Six studies are awaiting classification due to insufficient characteristics information. We contacted authors of these studies for clarification, however, only one study author replied our email. See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for more details.

Ongoing studies

We identified five ongoing studies. Two started in 2012 (ACTRN1261200097; NCT01566513), we contacted the authors and both replied stating that they are analysing the results and working on the publication. Chinman 2017 started in 2016, NCT02989805 started in 2017 and NCT02958007 is not yet recruiting. Participants recruited in three studies were aged over 18 years (ACTRN1261200097; NCT01566513; NCT02989805). Chinman 2017 recruited some participants aged under 18 years and NCT02958007 recruited participants aged over 50 years. Diagnoses of participants include serious mental illness (NCT01566513); mental or physical illness (Chinman 2017; NCT02958007; NCT02989805);, or a range of disorders/auditory verbal hallucination, schizophrenia, psychosis (ACTRN1261200097). The intervention groups in these studies all included a peer specialist who had personal live experience of hearing voices themselves or was trained in Intentional Peer Support.

Excluded studies

We excluded 25 studies with reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

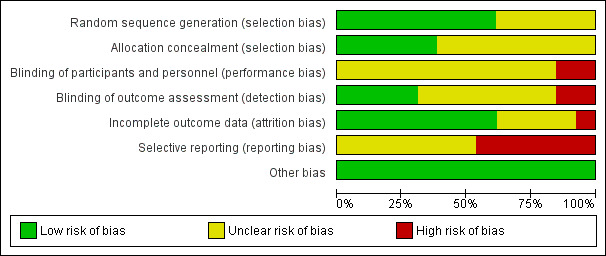

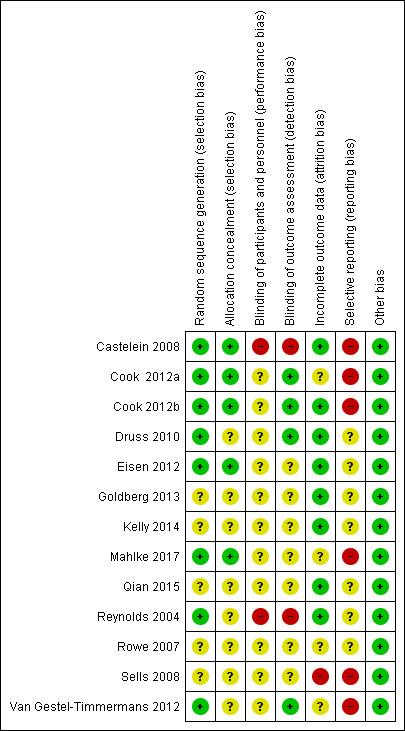

Risk of bias in included studies

The details of the assessments are available in the 'Risk of bias' table corresponding to each study in the Characteristics of included studies table, and are also presented in the 'Risk of Bias' graph in Figure 2 and 'Risk of Bias' Summary in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All 13 included studies reported some form of randomisation. Eight of 13 studies (61.5%) were at low risk of selection bias as they reported adequate sequence generation (Castelein 2008; Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Eisen 2012; Mahlke 2017; Reynolds 2004; Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012). The method used to generate the allocation sequence were such as drawing lots (Van Gestel‐Timmermans 2012), using random block number (Castelein 2008; Mahlke 2017), or computerised randomisation program (Cook 2012b; Cook 2012a; Druss 2010; Reynolds 2004). The remaining studies proving insufficient information to rate this bias ('unclear').