Abstract

The objective of this work is to use phage display libraries as a screening tool to identify peptides that facilitate transport across the mucus barrier. Mucus is a complex selective barrier to particles and molecules, limiting penetration to the epithelial surface of mucosal tissues. In mucus-associated diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF), mucus has increased viscoelasticity and a higher concentration of covalent and non-covalent physical entanglements compared to healthy tissues, which greatly hinders permeability and transport of drugs and particles across the mucosae for therapeutic delivery. Treatment of CF lung diseases and associated infections must overcome this abnormal mucosal barrier. Critical bottlenecks hindering effective drug penetration remain and while recent studies have shown hydrophilic, net-neutral charge polymers can improve the transport of nanoparticles and minimize interactions with mucus, there is a dearth of alternative carriers available. We hypothesized that the screening of a phage peptide library against a CF mucus model would lead to the identification of phage-displayed peptide sequences able to improve transport in mucus. These combinatorial libraries possess a large diversity of peptide-based formulations (108 - 109) to achieve unprecedented screening for potential mucus-penetrating peptides. Here, phage clones displaying discovered peptides were shown to have up to 2.6-fold enhanced diffusivity in the CF mucus model. In addition, we demonstrate reduced binding affinities to mucin compared to wild-type control. These findings suggest that phage display libraries can be used as a strategy to improve transmucosal delivery.

Keywords: phage display, drug delivery, cystic fibrosis, mucus, peptides

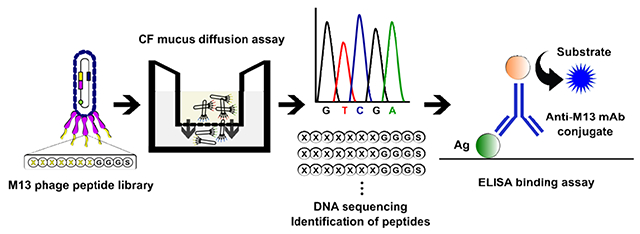

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The dense, viscoelastic mucus layer lining epithelial cells acts as a selective filter to drugs and other molecules and limits their therapeutic efficacy, necessitating the development of drug delivery systems with improved transport in mucus. The mucus layer consists of mostly water and mucin glycoprotein, along with globular proteins, salts, lipids, DNA, cells, and cellular debris (Bansil and Turner, 2006; Button and Button, 2013; Carlstedt and Sheehan, 1989; Cone, 2005; Leal et al., 2017; Thornton and Sheehan, 2004). The mucin glycoprotein is highly negatively charged due to high sialic acid and sulfate content. Within the mucus layer, there are a high number of physical entanglements, resulting in a heterogeneous mesh network with pore sizes ranging from 20 to 1800 nm across different organs and diseases (Leal et al., 2017). Collectively, these physicochemical properties of mucus decrease effective penetration and diffusion of drugs, molecules, and particles (Leal et al., 2017; Lieleg and Ribbeck, 2011; Sanders et al., 2009).

Several strategies have been exploited to improve mucosal permeability of drugs, including nanoparticle-based formulations, permeation enhancers, nanoemulsions, polymers, enzymes, and liposomes (Crater and Carrier, 2010; Cu and Saltzman, 2009; Lai et al., 2007; Lieleg et al., 2010; Schuster et al., 2013; Suk et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009b). While these studies have given insight into the importance of size and charge for improved particle transport through mucus, these formulations mostly rely on repeating simple chemistries on uniformly sized and charged formulations (Li et al., 2013), and may not necessarily possess the chemical complexity of natural mucus interacting compounds in terms of intermolecular interactions and chemical binding (Li et al., 2013). In nature, viruses and macromolecules have evolved to possess desired physicochemical and biological properties for efficient transport through mucus. Virus-like particles have demonstrated unhindered diffusive transport through mucus while displaying complex coat proteins on their surface (Olmsted et al., 2001). Additionally, recent work indicates that particle transport through hydrogels and mucus requires p articles with asymmetric charge properties, which have not been observed using current drug formulations (de Sousa et al., 2015; Li et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). These findings collectively suggest that biologically complex molecules can achieve effective, unhindered transport through mucus barriers.

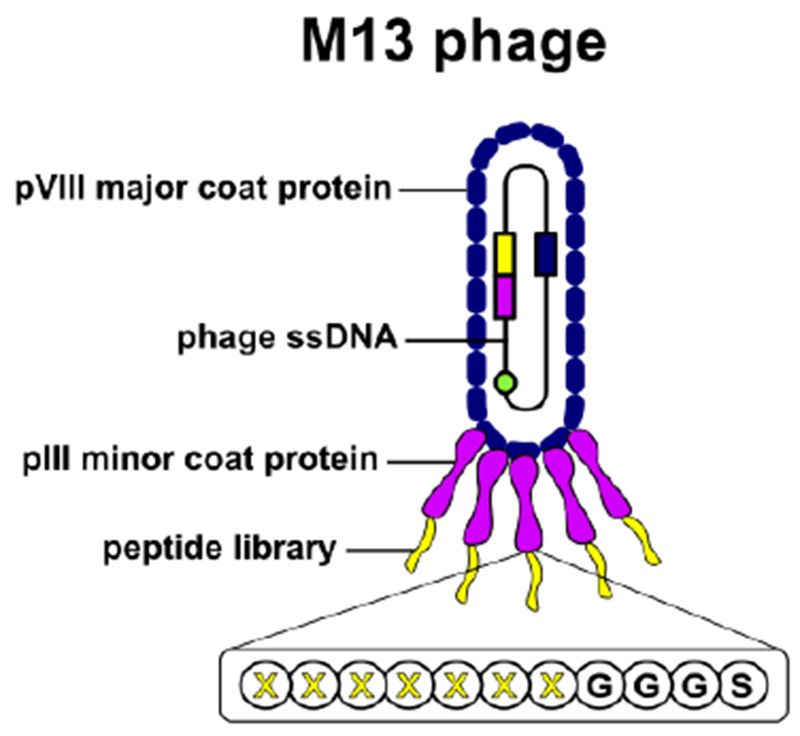

Inspired by nature to investigate and potentially improve the transport of molecules across the mucus barrier, we studied the use of bacteriophage (phage) libraries as a screening technology to identify novel mucus-penetrating peptides for diffusive transport through a mucus model (Fig. 1). Phage display is a technology whereby peptides, proteins, or antibody fragments are genetically engineered into the genome of the phage (i.e. virus that infects bacteria) to be displayed on the surface of the phage (Smith, 1985). With phage libraries, random peptides or antibody fragments are displayed on a coat protein of phage, and each phage displays a different peptide sequence with up to 1010 diversity (i.e. each phage displays copies of a different peptide). These libraries effectively function as a large collection of chemical formulations with diverse physicochemical properties and functionalities. These phage-presenting peptide libraries are subsequently screened against the desired target in vitro or in vivo; peptides that have affinity for the target are collected, amplified (i.e. make more copies) and re-screened until a subset of peptides has been identified to have the desired functionalities. Phage display libraries have been widely used to identify peptides for diverse applications including translocation across the gastrointestinal tract mucosa (Duerr et al., 2004; Hamzeh-Mivehroud et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2008; Kenngott et al., 2016; Yamaguchi et al., 2017), epitope mapping (Scott and Smith, 1990), ligand discovery against cells and tissues (Barry et al., 1996; Fievez et al., 2010; Higgins et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2015; Pasqualini and Ruoslahti, 1996), vascular targeting (Pasqualini, 1999), and binding and nucleation of materials (Ghosh et al., 2014; Ghosh et al., 2012; Whaley et al., 2000). However, they have not been exploited to achieve diffusive transport through the mucus barrier. Due to the sequence length and possible combinations of amino acids of these random peptide libraries, the libraries can serve as complex substrates to probe the microenvironment of mucus and identify mucus-penetrating peptides.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the M13 phage display library. The M13 phage is 880 nm in length and 6.6 nm in diameter, is covered by 2,700 pVIII coat proteins and has five copies each of pIII and pIX minor coat proteins at either end, along with pVI and pVII proteins (pVI, pVII, and pIX minor coat proteins are not represented in the figure). Random oligonucleotides encode a 7-mer peptide library with a GGGS flexible linker fused into the N-terminus of pIII minor coat protein. The phage library can achieve up to 109 in diversity. Not drawn to scale. Adapted from (van Rooy et al., 2012), with permission from Elsevier.

Mucus permeation may vary according to different organs and pathological conditions (Leal et al., 2017). In cystic fibrosis (CF), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by defective cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) expression primarily in epithelial cells (Bobadilla et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2009c; Tuggle et al., 2014), abnormal chloride and bicarbonate ion transport lead to aberrant mucus. Increased water absorption and dehydration of the epithelia result in thickened mucus, increased viscoelasticity and a higher concentration of physical entanglements, which results in decreased permeability of particles and drugs (Boucher, 2003, 2007a, b; Dawson et al., 2003; Ehre et al., 2014; Sanders et al., 2000). CF mucus has been found to hinder effective diffusion of drugs by up to 91% when compared to saline (Bhat et al., 1996). Ultimately, CF patients develop untreatable chronic infections due to concentrated mucus and impaired mucociliary clearance that traps and protect pathogens.

As a result, the primary purpose of this work was to demonstrate the util ity of phage libraries as a screening tool to identify phage-displayed peptides with improved transport across a CF mucus model. The CF mucus model serves as proof of concept to study transport through a biological barrier due to its barrier properties for drug transport, as described earlier. From screening, we identified phage-displayed peptides, their physicochemical properties for transport through a model of CF mucus, and probed for specific binding interactions between phage clones and mucin by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A number of reports have examined particle size and neutral charged formulations in mucosal environments (Crater and Carrier, 2010; Cu and Saltzman, 2009; Dawson et al., 2004a; Ensign et al., 2012; Lai et al., 2007; Schuster et al., 2013; Suk et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2008a); however, none have reported phage-displayed peptides that are able to diffuse in a cystic fibrosis mucus model. This initial work to identify mucus-penetrating phage-displayed peptides may be translated to facilitate transport and improve delivery of drug and gene carriers across mucus barriers present in diseases like cystic fibrosis, asthma, and chronic pulmonary obstructive disease.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Preparation of CF mucus model

A cystic fibrosis mucus model (CF mucus) was adapted from McGill and Smyth (McGill and Smyth, 2010). The model comprises of 80 mg/mL mucin from porcine stomach type III (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 60 mg/mL mucin from porcine stomach type II (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 3.2 mg/mL lecithin (Spectrum Chemical, Gardena, CA), 32 mg/mL BSA (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 4.5 mg/mL NaCl (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in a 20mM HEPES buffer (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA). The reagents were transferred to a sterile tube and mixed overnight at room temperature in a shaker at 5 rpm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

2.2. Phage library screening in CF mucus

An M13 phage library of random heptapeptides fused to the pIII minor coat protein by a flexible linker (GGGS) (Ph.D.™-7 Phage Display Peptide Library, NEB, MA) with a library diversity of 1.3 × 109 plaque forming units (pfu), was iteratively screened against the CF mucus model in a 3.0 μm polyester membrane 12-well transwell system (Corning, MA) to identify mucus-penetrating peptides. The library diversity refers to the number of phage displaying different peptide sequences. An initial concentration of 2×1010 phage pfu was mixed with CF mucus, and 250 μL of the mixture was transferred to the apical compartment (donor) in the transwell system containing 1.5 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in the basolateral compartment (receiver) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (25°C). After 1 h, the eluate was collected from the basolateral side and titered using standard double-layer plaque assay to quantify phage concentration. The eluted phage library was amplified in XL-1 Blue E. coli (Agilent, CA) to make more copies, which were quantified by plaque assay prior to the next round of screening. Equivalent amounts of input phage were added for each round. This iterative screening was performed for a total of four rounds.

2.3. Identification of individual phage clones

After the fourth round of screening, the elution sample was titered by plaque assay. Individual phage plaques (i.e. phage with individual sequences) were selected from titer plates, amplified in XL-1 Blue E. coli, and their DNA was isolated. Single-stranded phage DNA was purified from individual phage plaques using QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Germanton, MD) and sequenced by Sanger DNA sequencing. The insert region (i.e. encoding for phage-presenting peptide) was sequenced using the primer 5′-CTCATTTTCAGGGATAGCAA-3′. Physicochemical properties of peptide sequences were determined in silico using Protein Calculator v3.4 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), with the hydrophobicity GRAVY score calculated according to Kyte-Doolittle(Kyte and Doolittle, 1982). Sequence database analysis was performed using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTp, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD).

2.4. Diffusivity of phage clones in CF mucus and saline

The diffusion coefficients of selected phage-presenting peptide clones were calculated (Desai and Vadgama, 1991) from phage diffusion studies in a 3.0 μm polyester membrane 24-well transwell against CF mucus at room temperature (25°C). An initial concentration of 2×1010 pfu was mixed with CF mucus and 100 μL of the mixture was transferred to the donor compartment in the transwell system containing 0.6 mL PBS in the receiver compartment. At 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes, the entire eluate was collected from the receiver compartment and replenished with fresh PBS. Collected eluates were titered by plaque assay to determine phage concentration. The apparent diffusion coefficient (D) was calculated according to Fick’s law of diffusion, by the following equation:

| (1) |

Where D could be obtained from the slope of Q (amount of phage pfu transferred) versus time (t) plots. c2 is concentration in the diffusion chamber (receiver), c1 is concentration in the initial chamber (donor), X is the thickness of the membrane, and A is the surface area of the membrane. The data presented is the average of three independent experiments.

Diffusion coefficients of phage clones in PBS were calculated using measurements from dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA). Size measurements were performed at 25°C at a scattering angle of 173°. A concentration of 2×1010 phage pfu was added to 1mL PBS and measurements performed according to instrument instructions. The data presented is the average of three independent experiments. Diffusion coefficients were calculated from the Stokes-Einstein equation:

| (2) |

Where D is the apparent diffusion coefficient, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, η is the solvent viscosity, and rH is the apparent hydrodynamic radius.

2.5. Phage ELISA

To characterize binding affinity of M13 phage clones to mucin, 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were coated with 200 μL per well of a 100 μg/mL solution of mucin from porcine stomach type III in 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.6, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Nonspecific binding sites on the wells were blocked by adding 300 μL of Pierce protein-free blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), followed by incubation for 2 h at room temperature. Wells were washed 6 times with 300 μL of TBST (50 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCI, and 0.1% [v/v] Tween-20). Phage clones stocks were diluted to 5.0 × 1011 pfu/mL in TBST in a separate blocked plate, and 100 μL of each phage dilution was added to a mucin-coated well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature under gentle agitation. Wells were washed 6 times with 300 μL of TBST. Bound phage was probed using HRP-conjugated anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (Abeam, Cambridge, MA), diluted 1:50 in blocking buffer (100 μL/well) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. After washing wells 6 times with 300 μL of TBST, 100 μL/well of 1-step ultra TMB-ELISA substrate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added and incubated for 15-30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation until color development. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL/well of 2M sulfuric acid. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm by a plate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan, Switzerland). Data presented are the average of three independent experiments.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, all data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of differences between means of two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the statistical significance of differences among means of more than two groups.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of peptide sequences with diffusion across CF mucus

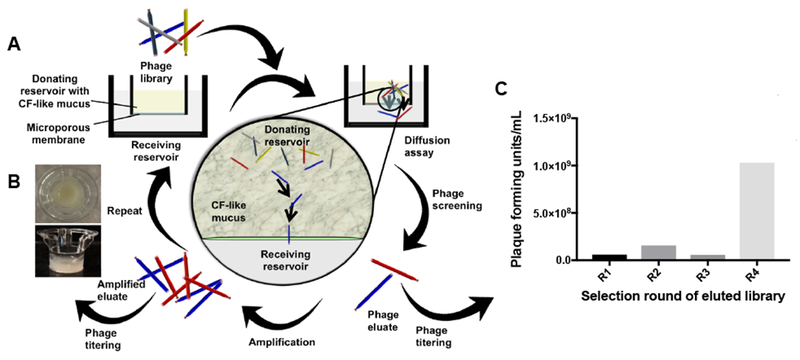

A phage library displaying heptapeptides with a flexible linker (GGGS) and a diversity of 1.3 × 109 pfu (i.e. amount of phage displaying different peptides) was iteratively screened against a CF mucus model (Fig. 2A) to identify peptides that diffuse across the barrier. In the first round, the original phage library (2.0 × 1010 pfu) was mixed with CF mucus, added on the donor side of the transwell system (Fig. 2B), and the number of phage that diffused to the receiver side was quantified by plaque formation assay after 1 h. Phage collected in the first round was amplified and underwent a second round of screening across CF mucus. The same procedure was repeated for a total of four rounds of screening, with equivalent initial amounts of phage added for each round. In the fourth round, there was a 17.5-fold enrichment in the amount of eluted phage that penetrated through CF mucus, compared to the first round (Fig. 2C). This finding indicates that after four rounds of screening, the phage pool that transports across CF mucus was enriched for clones that have favorable interactions with mucus for transport (i.e. phage whose transport was not completely hindered by mucus). There was negligible difference in concentration of phage that penetrated across the CF mucus between round 1 and round 3 screenings (Fig. 2C). Enrichment of mucus penetrating phage at the fourth round of screening suggests a selection of phage with desired properties (i.e. mucus penetration) (Dennis, 2015).

Figure 2.

Overview of the iterative phage library screening assay in CF mucus model. (A) Mucus containing 2 × 1010 phage plaque forming units is incubated in the donating reservoir. Phage that penetrate through mucus are collected, quantified by titering, and amplified by E. coli for the next round of screening. (B) Top-down view and side view of a transwell insert containing a mucus layer for screens against CF mucus. (C) Enrichment of phage plaque forming units recovered from the basolateral side after four rounds of screening (R1 to R4, n=1). Phage concentration was quantified by standard plaque assay.

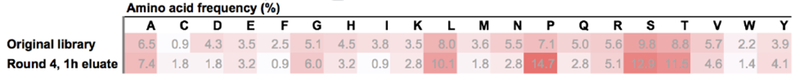

Thirty phage clones were isolated and identified by Sanger DNA sequencing to identify peptide sequences from the fourth round. Twenty-six unique peptides were identified (Table S1). The amino acid frequencies of the peptides sequenced in round 4 and the original library are illustrated in Fig. 3. Interestingly, there is an enrichment in proline (P), serine (S), and threonine (T) amino acids in round 4 sequences compared to the original library (Fig. 3). The backbone of mucin proteins consists of repeat ‘PTS’ (proline, threonine, and serine) domains (Thornton et al., 2008), and the enrichment of these amino acids in round 4 eluate suggests that peptides mimicking mucin sequences may diffuse in mucus, potentially due to unhindered intermolecular interactions with mucins. The physicochemical properties of phage clones recovered from the fourth round of selection against CF mucus were determined (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Peptide sequence frequencies obtained may vary depending on the possible different codons for each amino acid, and their frequency can affect the diversity of the original library, as well as the results from panning experiments. Nevertheless, the rationale used to select sequences of interest in this work was not only based on the most abundant sequences after rounds of selection, but rather on the physicochemical properties of the selected sequences. Of interest, SSQLSRP, ISLPSPT, and YNSPTHH presented close to neutral charges at pH 7.0 and were neutral to hydrophilic as indicated by the GRAVY index score (grand average of hydropathy) calculated according to the literature (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982) (Table 1). Since prior work with net-neutral charge, hydrophilic polymers improved transport in mucus (Calvo et al., 1997; Dawson et al., 2004b; Griffiths et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2007; Suk et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009a; Wang et al., 2008,b; Xu et al., 2013), these peptide sequences were used in subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Amino acid frequencies (%) occurrence in the original phage library and in Round 4, 1 h eluate sequenced clones. Darker red scale indicates higher values. Original library frequencies retrieved from the manufacturer certificate of analysis.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequences, net charge at 7.0, and GRAVY score of peptide hits found by phage display screening against CF mucus. Net charge was calculated by Protein Calculator v3.4 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA. Available at http://protcalc.sourceforge.net/), and GRAVY score was calculated according to the literature (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982).

| Phage clone | Sequence | Net charge at pH 7.0 | GRAVY score |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSQ | SSQLSRPGGGS | 0.9 | −0.927 |

| ISL | ISLPSPTGGGS | −0.1 | 0.073 |

| YNS | YNSPTHHGGGS | 0.4 | −1.482 |

3.2. Diffusion assay of phage clones displaying the identified peptides across CF mucus

To confirm that the identified peptides improved diffusion of phage across CF mucus, the apparent diffusion coefficients of phage clones displaying SSQLSRP, ISLPSPT, and YNSPTHH (denoted as SSQ-phage, ISL-phage, and YNS-phage, respectively) in CF mucus were measured by a bulk diffusion assay and compared to wild-type phage that did not display any peptides on the pIII capsid (M13KE). Free diffusion of phage in PBS was not measured by bulk diffusion assay because phage diffusion is rapid in aqueous solution and cannot be accurately measured in our system. Instead, to determine phage diffusion in PBS, the hydrodynamic diameters of phage clones suspended in PBS were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and used to calculate the apparent diffusion coefficients from the Stokes-Einstein equation. The experimental values obtained here for M13 phage diffusion coefficients in PBS are in agreement with what has been found in the literature for filamentous fNEL phage in water (68 ± 10 × 10−9 cm2/s) (Hu et al., 2010) and filamentous fd phage in the isotropic phase in buffers (Blanco et al., 2011; Lettinga et al., 2005). The calculated values are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diffusion coefficients of phage clones in PBS and CF mucus (CM), and ratios of the average apparent diffusion coefficients in PBS (DPBS) compared to CF mucus (DCM). DH, apparent hydrodynamic diameter, D, apparent diffusion coefficient, PBS, phosphate buffered saline, CM, CF mucus.

| Phage clone | DH, nma | D, 10−9 cm2 s−1 | DPBS/DCMc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBSb | CM | |||

| M13KE | 95.09 ± 4.72 | 51.9 ± 2.6 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 288 |

| SSQ | 98.20 ± 2.87 | 50.2 ± 1.5 | 0.20 ± 0.11 | 251 |

| ISL | 90.26 ± 2.38 | 54.6 ± 1.4 | 0.47 ± 0.16 | 116 |

| YNS | 112.03 ± 1.02 | 43.9 ± 0.4 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 258 |

Determined by dynamic light scattering.

DPBS is calculated from the Stokes-Einstein equation.

The DPBS/DCM ratio indicates by what multiple the average diffusion coefficient in CF mucus is slower than in saline.

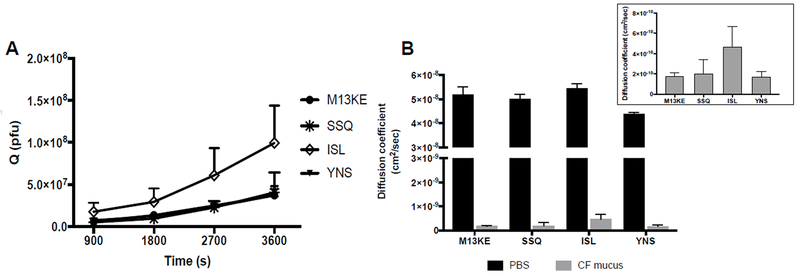

As shown in Fig. 4A, all phage clones diffused across CF mucus to the receiver compartment starting after 15 min, and the increase in diffused amounts (Q) was time-dependent. The diffused fraction of the ISL-phage in CF mucus was 2.7-fold greater compared to wild-type control phage at 1 h (Fig. 4A). The ISL-phage diffusion coefficient in CF mucus was 2.6-fold higher compared to wild-type control phage (Fig. 4B and Table 2). These findings suggest that the ISL identified peptide have the ability to facilitate phage diffusion across CF mucus. However, the difference in the diffusion coefficient of ISL-phage and M13KE in CF mucus was not statistically significant (Fig. 4B inset, p = 0.068), which can be attributed in part to the accuracy of the gold standard plaque assay (Cormier and Janes, 2014). The average diffusivity of M13KE, SSQ-, ISL-, and YNS-phage clones in CF mucus decreased 288-, 251-, 116-, and 258-fold compared to the same phage clones in PBS, respectively (Fig. 4B and Table 2).

Figure 4.

(A) Phage clones selected from round four screening time-dependent diffusion across CF mucus. Each phage clone (2.0 × 1010 pfu) was mixed with CF mucus and added on the apical side of a transwell system. Phage that diffused across the mucus layer were recovered from the basolateral side at specific time points, and phage concentration in the eluates was determined by plaque assay. (B) Apparent diffusion coefficients of phage clones in PBS and CF mucus. The insert describes a plot of the same data with CF mucus only (p=0.068 for ISL-phage and M13KE in CF mucus). Data represents mean ± SD (n = 3).

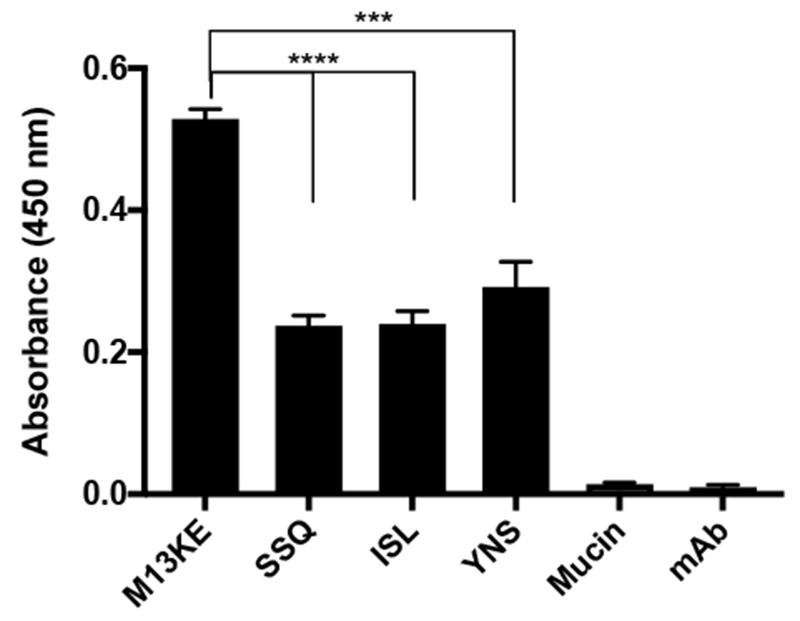

3.3. Phage binding affinity ELISA

To understand binding affinities between phage-displayed peptides and the major protein component of mucus (mucin), an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed using as the target a 100 μg/mL solution of mucin from porcine stomach type III immobilized on the wells of 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates with high protein-binding capacity. A mucin solution was used instead of CF mucus since other mucus components such as lecithin or BSA might block the binding of mucin protein to the wells, or even promote heterogeneous binding, affecting results. Phage clones SSQ-phage, ISL-phage, and YNS-phage binding to mucin was measured by ELISA and compared to wild-type phage that did not display any peptides on the pIII coat protein (M13KE). The anti-M13 antibody used for detection binds specifically to an epitope on the pVIII major coat protein, covering the N-terminal region of the g8p: AEGDDPAKAAFDSLQASAT (https://www.abcam.com/m13-antibody-b62-fe2-hrp-ab50370.html). There is no difference in sequence of the pVIII phage coat protein between the Ph.D.-7 library and the wild-type M13KE phage. Therefore, the anti-M13 antibody used is expected to have the same binding affinities between M13KE and Ph.D.-7 phage library clones; thus the binding affinities measured correlate with phage-mucin interactions.

M13KE wild-type phage demonstrated a statistically significant higher binding affinity for mucin than phage clones SSQ-phage, ISL-phage, and YNS-phage (Fig. 5). Mucin only and monoclonal antibody only controls did not show specific binding, confirming that the measured binding affinities are specific to interactions between phage and mucin.

Figure 5.

ELISA assay to characterize binding affinities between phage-displayed peptides and mucin. Each mucin coated well of a 96-well plate was incubated with 5.0×1010 pfu total phage/well. Mucin bar represents only mucin coated wells but no phage present, accounting for nonspecific interactions between anti-M13 monoclonal antibody and mucin. mAb bar represents only blocked wells but no mucin nor phage present, accounting for nonspecific interactions between anti-M13 monoclonal antibody and plastic and blocking agent. Data represents mean ± SD (n = 3). ***p=0.0004, ****p<0.0001

4. Discussion

Phage display library screening led to the identification of CF mucus penetrating peptides

Physicochemical mechanisms governing mucus permeability to particles and molecules include size exclusion, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, and other specific binding interactions (Leal et al., 2017; Lieleg and Ribbeck, 2011). Particles and molecules can adhere to mucin fibers or can be hindered by the size of the mesh spacing between the mucin fibers (Olmsted et al., 2001). In this study, we identified and then evaluated three phage-displayed peptides that facilitate diffusion across a CF mucus model. The peptides were identified by in vitro screening of phage display libraries. The screening was designed to specifically select for peptides that could facilitate phage transport across mucus. The selection resulted in a small set of peptide sequences with close to neutral charges in the mucus pH environment and were mostly hydrophilic. Interestingly, a BLAST search revealed the peptide sequence ISLPSPT has homology to mucin-16 (MUC16), a cell surface associated mucin present in the airways, salivary glands, cervix, and eyes (Leal et al., 2017), which might suggest that mucin-mimicking peptides sequences have enhanced diffusivities in mucus. However, further future work should be conducted to prove this hypothesis since there is no statistical significance in the BLAST alignments due to the shortness of the sequence. BLAST results for SSQLSRP and YNSPTHH did not show similarity to protein sequences associated with mucus. It is feasible that mucus biomimetic peptides might shield or have less hindered intermolecular interactions with mucins, facilitating their diffusion across mucus. The concept of substrate-mimicking peptides has been reported with collagen-like peptides, whereby peptide sequences with sequence homology to collagen (G-X-X, where X is proline or hydroxyproline), are able to bind and favorably interact with collagen substrates (Chan et al., 2010; Chung et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2014). Additionally, the combinations of alternately positively and negatively charged amino acids have been previously shown to minimize interactions with mucus and help achieve unhindered diffusion of viruses and macromolecules in mucus (Cone, 2009; Li et al., 2013; Olmsted et al., 2001). This is in agreement with reported literature, where virus-like particles (~38 to 55 nm in diameter) with capsid densely coated with equal positive and negative charges are able to diffuse as rapidly in human cervical mucus as saline (Olmsted et al., 2001), due to a hydrophilic and net-neutral surface that minimizes hydrophobic and electrostatic adhesive interactions (Cone, 2005; Lai et al., 2007). However, amine-, carboxyl-, and epoxy-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles with similar size to the virus-like particles strongly adhered to mucus and had negligible diffusion in human cervical mucus (Olmsted et al., 2001). Also, others have shown alternating charged peptides exhibit enhanced transport in mucus compared to block charge peptides with the same net charge and amino acid composition, which suggests the role of amino acid permutations in diffusion through the mucus barrier (Li et al., 2013).

Enrichment after four rounds of screening indicates selection for phage particles with enhanced diffusion across CF mucus

From diffusion experiments in CF mucus with phage clones displaying peptide sequences, the mucin-mimicking peptide phage (ISL-phage) exhibited higher diffusivity compared to the other peptide sequences and the control phage without peptide. However, no statistical significance was found between samples. This could be explained partially by the common increased variation between replicates found in traditional gold standard plaque assays (Cormier and Janes, 2014). Also, the possible interactions between the phage particle and CF mucus may impact the transport of phage through the barrier. The M13 phage is 880 nm in length and 6.6 nm in diameter, has five copies each of pIII and pIX proteins at either end, along with pVI and pVII proteins (Lee et al., 2012), and is covered by 2,700 pVIII coat proteins. Since M13 is like a flexible rod and can stretch and bend to have different conformations (and sizes) (Khalil et al., 2007), M13 phage can have hindered diffusion in CF mucus due to size exclusion mechanisms. Moreover, the M13 Ph.D.-7 library is a combinatorial library of random heptapeptides fused to the minor coat protein pIII of M13 phage. However, the majority of the coat proteins are pVIII, which assemble along the length of the phage and have the largest surface area. As a result, it is feasible that interactions between the native pVIII coat protein and CF mucus affect transport. The net-negative charge of pVIII may minimize electrostatic attraction with mucus and have repulsive interactions with mucus for diffusive transport. However as stated before, since M13 can conform into different shapes, the peptides displayed on pIII can facilitate and possibly improve transport through the mucus.

According to reports in the literature with naive libraries (Dennis, 2015; Marks et al., 1991; Winter et al., 1994), enrichment is usually not observed during the first two rounds of selection, but followed by an enrichment ratio greater than 10 and as high as 1000 or more in later rounds. Enrichment was not observed in the first three rounds of screening. We speculate that it was a result of the higher stringency of the mucus barrier used in the screenings, as demonstrated by the low ratios of output to input (data not shown). According to Derda and colleagues (Derda et al., 2011), the panning stringency can be tuned to minimize the selection of non-specific sequences, where increasing the strength of the selection helps avoid selection of non-specific fast-amplifying clones. In addition, we compared the phage clones isolated from the fourth round of screening (Supplementary Table 1) with databases encompassing previously isolated peptides and known as “target unrelated peptides” (TUP) motifs (Huang et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2011; Matochko et al., 2014). These databases have identified a large set of fast growers sequences. The sequences selected for further validation (SSQLSRP, ISLPSPT, and YNSPTHH) were not found in these extensive databases. However, the sequence GETRAPL, known as a suspected TUP for binding to various targets, was present. Nevertheless, this sequence only represented 10% of the total sequenced clones, and it was not subsequently tested. Moreover, it is not clear to which extent overrepresented sequences in the original library or fast growers should be considered as non-specific sequences; previously, identified fast growing sequences panned from Ph.D.-7 libraries (Matochko et al., 2014) are enriched and can also have confirmed functionality, such as target binding. Regardless, a 17.5-fold enrichment after four rounds of screening compared to the first round suggests selection for diffusive phage particles, and a 2.6-fold improvement in the diffusion coefficient with the mucus mimicking peptide phage (ISL-phage) compared to wild-type control phage indicates that peptides can facilitate diffusive transport of phage through mucus.

Probing for binding affinities indicates lower binding of phage-displaying peptides to mucin

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated that wild-type phage that did not display any peptides on the pi II capsid had a statistically significant higher binding affinity for mucin compared to phage-displayed peptide clones SSQ-phage, ISL-phage, and YNS-phage. SSQ- and ISL-phage presented the lower binding affinities to mucin, which correlated with their higher diffusion coefficients found in CF mucus.

Mucins, the primary non-aqueous component of mucus, are gel-forming polymers carrying a complex and heterogeneous structure with domains that undergo a variety of molecular interactions, such as hydrophilic/hydrophobic, hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions (Bansil and Turner, 2006; Khanvilkar et al., 2001; Leal et al., 2017; Thornton and Sheehan, 2004). These domains constitute numerous binding sites for interactions with molecules and particles. Binding interactions with mucins or other components in mucus hinder diffusion and thus inhibit transport (Lieleg and Ribbeck, 2011). Indeed, wild-type phage and YNS-phage presented higher binding interactions with mucin and lower diffusion coefficients in CF-like mucus. This finding suggests that greater affinity of a molecule bound to the mucin, it has less time to freely diffuse.

5. Conclusions

Here, we presented a high-throughput strategy to screen a large repertoire of phage-displayed peptides and identify sequences that facilitate transport of bacterial viruses across complex cystic fibrosis mucus barriers. An M13 phage peptide library was iteratively screened against a CF mucus model to identify phage-displayed peptides with the ability to penetrate through mucus. Selected identified phage clones displaying peptides were assayed against CF mucus and saline to quantify their diffusivities. Results yielded phage-presenting peptide sequences that demonstrated up to 2.6-fold enhanced diffusivities in CF-mucus compared to wild-type control. Moreover, we were able to demonstrate by probing binding affinities that phage-displaying peptides bind weakly to mucins compared to wild-type phage, and there was a slightly negative correlation between the diffusion coefficients of phage clones in CF mucus and the binding affinity between phage with mucin. While further studies are needed to translate this work with patient samples, these findings suggest that this biomolecule-based strategy can be extended to facilitate transport of drugs, particles and drug carriers through previously intractable physiological barriers, such as the mucus barrier present in various diseases including CF, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, and HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL138251, PhRMA Foundation Research Starter Grant, startup funds from the College of Pharmacy, University of Texas at Austin, and the Williams and McGinity Graduate Fellowship from the College of Pharmacy, University of Texas at Austin. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information. Table S1. Identification of phage clones recovered from the fourth round of selection against CF mucus and its physicochemical properties.

References

- Bansil R, Turner BS, 2006. Mucin structure, aggregation, physiological functions and biomedical applications. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 11,164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Barry MA, Dower WJ, Johnston SA, 1996. Toward cell-targeting gene therapy vectors: selection of cell-binding peptides from random peptide-presenting phage libraries. Nat Med 2,299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat PG, Flanagan DR, Donovan MD, 1996. Drug diffusion through cystic fibrotic mucus: Steady-state permeation, rheologic properties, and glycoprotein morphology. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 85, 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P, Kriegs H, Lettinga MP, Holmqvist P, Wiegand S, 2011. Thermal diffusion of a stiff rod-like mutant Y21M fd-virus. Biomacromolecules 12,1602–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobadilla JL, Macek M Jr., Fine JP, Farrell PM, 2002. Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations--correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum Mutat 19, 575–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC, 2003. Regulation of airway surface liquid volume by human airway epithelia. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 445, 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC, 2007a. Cystic fibrosis: a disease of vulnerability to airway surface dehydration. Trends Mol Med 13, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC, 2007b. Evidence for airway surface dehydration as the initiating event in CF airway disease. J Intern Med 261, 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button BM, Button B, 2013. Structure and function of the mucus clearance system of the lung. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo P, Remuñán-López C, Vila-Jato JL, Alonso M, 1997. Novel hydrophilic chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanoparticles as protein carriers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 63, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carlstedt I, Sheehan JK, 1989. Structure and macromolecular properties of cervical mucus glycoproteins. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 43, 289–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JM, Zhang L, Tong R, Ghosh D, Gao W, Liao G, Yuet KP, Gray D, Rhee J-W, Cheng J, 2010. Spatiotemporal controlled delivery of nanoparticles to injured vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 2213–2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung W-J, Kwon K-Y, Song J, Lee S-W, 2011. Evolutionary screening of collagen-like peptides that nucleate hydroxyapatite crystals. Langmuir 27, 7620–7628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RA, 2005. Chapter 4 - Mucus A2 - Mestecky, Jiri, in: Lamm ME, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, Mayer L, Strober W (Eds.), Mucosal Immunology (Third Edition). Academic Press, Burlington, pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cone RA, 2009. Barrier properties of mucus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61, 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier J, Janes M, 2014. A double layer plaque assay using spread plate technique for enumeration of bacteriophage MS2. J Virol Methods 196, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crater JS, Carrier RL, 2010. Barrier properties of gastrointestinal mucus to nanoparticle transport. Macromol Biosci 10, 1473–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cu Y, Saltzman WM, 2009. Controlled surface modification with poly(ethylene)glycol enhances diffusion of PLGA nanoparticles in human cervical mucus. Mol Pharm 6, 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M, Krauland E, Wirtz D, Hanes J, 2004a. Transport of polymeric nanoparticle gene carriers in gastric mucus. Biotechnol Prog 20, 851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M, Krauland E, Wirtz D, Hanes J, 2004b. Transport of polymeric nanoparticle gene carriers in gastric mucus. Biotechnology progress 20, 851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M, Wirtz D, Hanes J, 2003. Enhanced viscoelasticity of human cystic fibrotic sputum correlates with increasing microheterogeneity in particle transport. J Biol Chem 278, 50393–50401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa IP, Steiner C, Schmutzler M, Wilcox MD, Veldhuis GJ, Pearson JP, Huck CW, Salvenmoser W, Bernkop-Schnürch A, 2015. Mucus permeating carriers: formulation and characterization of highly densely charged nanoparticles. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 97, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MS, 2015. Selection and Screening Strategies, in: Sidhu SS, Geyer CR (Eds.), Phage display in biotechnology and drug discovery, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton. [Google Scholar]

- Derda R, Tang SK, Li SC, Ng S, Matochko W, Jafari MR, 2011. Diversity of phage-displayed libraries of peptides during panning and amplification. Molecules 16, 1776–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Vadgama P, 1991. Estimation of effective diffusion coefficients of model solutes through gastric mucus: assessment of a diffusion chamber technique based on spectrophotometric analysis. Analyst 116, 1113–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr DM, White SJ, Schluesener HJ, 2004. Identification of peptide sequences that induce the transport of phage across the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier. J Virol Methods 116, 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehre C, Ridley C, Thornton DJ, 2014. Cystic fibrosis: an inherited disease affecting mucin-producing organs. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 52, 136–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensign LM, Schneider C, Suk JS, Cone R, Hanes J, 2012. Mucus Penetrating Nanoparticles: Biophysical Tool and Method of Drug and Gene Delivery. Advanced Materials 24, 3887–3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fievez V, Plapied L, Plaideau C, Legendre D, des Rieux A, Pourcelle V, Freichels H, Jéróme C, Marchand J, Préat V, 2010. In vitro identification of targeting ligands of human M cells by phage display. International journal of pharmaceutics 394, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Bagley AF, Na YJ, Birrer MJ, Bhatia SN, Belcher AM, 2014. Deep, noninvasive imaging and surgical guidance of submillimeter tumors using targeted M13-stabilized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 13948–13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Lee Y, Thomas S, Kohli AG, Yun DS, Belcher AM, Kelly KA, 2012. M13-templated magnetic nanoparticles for targeted in vivo imaging of prostate cancer. Nature nanotechnology 7, 677–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths PC, Cattoz B, Ibrahim MS, Anuonye JC, 2015. Probing the interaction of nanoparticles with mucin for drug delivery applications using dynamic light scattering. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 97, 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzeh-Mivehroud M, Mahmoudpour A, Rezazadeh H, Dastmalchi S, 2008. Nonspecific translocation of peptide-displaying bacteriophage particles across the gastrointestinal barrier. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 70, 577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins LM, Lambkin I, Donnelly G, Byrne D, Wilson C, Dee J, Smith M, O’Mahony DJ, 2004. In Vivo Phage Display to Identify M Cell-Targeting Ligands. Pharmaceutical Research 21, 695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Miyanaga K, Tanji Y, 2010. Diffusion properties of bacteriophages through agarose gel membrane. Biotechnol Prog 26, 1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Ru B, Li S, Lin H, Guo F-B, 2010. SAROTUP: scanner and reporter of target-unrelated peptides. BioMed Research International 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Ru B, Zhu P, Nie F, Yang J, Wang X, Dai P, Lin H, Guo F-B, Rao N, 2011. MimoDB 2.0: a mimotope database and beyond. Nucleic Acids Research 40, D271–D277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H-E, Farr R, Lee S-W, 2014. Collagen mimetic peptide engineered M13 bacteriophage for collagen targeting and imaging in cancer. Biomaterials 35, 9236–9245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SK, Woo JH, Kim MK, Woo SS, Choi JH, Lee HG, Lee NK, Choi YJ, 2008. Identification of a peptide sequence that improves transport of macromolecules across the intestinal mucosal barrier targeting goblet cells. Journal of Biotechnology 135, 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenngott EE, Cole S, Hein WR, Hoffmann U, Lauer U, Maass D, Moore L, Pfeil J, Rosanowski S, Shoemaker CB, Umair S, Volkmer R, Hamann A, Pernthaner A, 2016. Identification of Targeting Peptides for Mucosal Delivery in Sheep and Mice. Mol Pharm 13, 202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil AS, Ferrer JM, Brau RR, Kottmann ST, Noren CJ, Lang MJ, Belcher AM, 2007. Single M13 bacteriophage tethering and stretching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 4892–4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanvilkar K, Donovan MD, Flanagan DR, 2001. Drug transfer through mucus. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 48, 173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J, Doolittle RF, 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology 157, 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SK, O’Hanlon DE, Harrold S, Man ST, Wang YY, Cone R, Hanes J, 2007. Rapid transport of large polymeric nanoparticles in fresh undiluted human mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 1482–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal J, Smyth HDC, Ghosh D, 2017. Physicochemical properties of mucus and their impact on transmucosal drug delivery. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BY, Zhang J, Zueger C, Chung W-J, Yoo SY, Wang E, Meyer J, Ramesh R, Lee SW, 2012. Virus-based piezoelectric energy generation. Nature nanotechnology 7, 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettinga MP, Barry E, Dogic Z, 2005. Self-diffusion of rod-like viruses in the nematic phase. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 71, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Li LD, Crouzier T, Sarkar A, Dunphy L, Han J, Ribbeck K, 2013. Spatial configuration and composition of charge modulates transport into a mucin hydrogel barrier. Biophys J 105, 1357–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieleg O, Ribbeck K, 2011. Biological hydrogels as selective diffusion barriers. Trends Cell Biol 21, 543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieleg O, Vladescu I, Ribbeck K, 2010. Characterization of particle translocation through mucin hydrogels. Biophys J 98, 1782–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GW, Livesay BR, Kacherovsky NA, Cieslewicz M, Lutz E, Waalkes A, Jensen MC, Salipante SJ, Pun SH, 2015. Efficient Identification of Murine M2 Macrophage Peptide Targeting Ligands by Phage Display and Next-Generation Sequencing. Bioconjug Chem 26, 1811–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks JD, Hoogenboom HR, Bonnert TP, McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G, 1991. By-passing immunization: human antibodies from V-gene libraries displayed on phage. Journal of molecular biology 222, 581–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matochko WL, Cory Li S, Tang SKY, Derda R, 2014. Prospective identification of parasitic sequences in phage display screens. Nucleic Acids Research 42, 1784–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill SL, Smyth HD, 2010. Disruption of the mucus barrier by topically applied exogenous particles. Molecular pharmaceutics 7, 2280–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted SS, Padgett JL, Yudin AI, Whaley KJ, Moench TR, Cone RA, 2001. Diffusion of macromolecules and virus-like particles in human cervical mucus. Biophys J 81, 1930–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini R, 1999. Vascular targeting with phage peptide libraries. The quarterly journal of nuclear medicine : official publication of the Italian Association of Nuclear Medicine (AIMN) [and] the International Association of Radiopharmacology (IAR) 43, 159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E, 1996. Organ targeting in vivo using phage display peptide libraries. Nature 380, 364–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders N, Rudolph C, Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Demeester J, 2009. Extracellular barriers in respiratory gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61, 115–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders NN, De Smedt SC, Van Rompaey E, Simoens P, De Baets F, Demeester J, 2000. Cystic fibrosis sputum: a barrier to the transport of nanospheres. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162, 1905–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster BS, Suk JS, Woodworth GF, Hanes J, 2013. Nanoparticle diffusion in respiratory mucus from humans without lung disease. Biomaterials 34, 3439–3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JK, Smith GP, 1990. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science 249, 386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GP, 1985. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science 228, 1315–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk JS, Lai SK, Wang YY, Ensign LM, Zeitlin PL, Boyle MP, Hanes J, 2009. The penetration of fresh undiluted sputum expectorated by cystic fibrosis patients by nonadhesive polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials 30, 2591–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BC, Dawson M, Lai SK, Wang Y-Y, Suk JS, Yang M, Zeitlin P, Boyle MP, Fu J, Hanes J, 2009a. Biodegradable polymer nanoparticles that rapidly penetrate the human mucus barrier. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 19268–19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BC, Dawson M, Lai SK, Wang YY, Suk JS, Yang M, Zeitlin P, Boyle MP, Fu J, Hanes J, 2009b. Biodegradable polymer nanoparticles that rapidly penetrate the human mucus barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 19268–19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Fatehi M, Linsdell P, 2009c. Mechanism of direct bicarbonate transport by the CFTR anion channel. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 8, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA, 2008. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol 70, 459–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton DJ, Sheehan JK, 2004. From mucins to mucus: toward a more coherent understanding of this essential barrier. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1, 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuggle KL, Birket SE, Cui X, Hong J, Warren J, Reid L, Chambers A, Ji D, Gamber K, Chu KK, Tearney G, Tang LP, Fortenberry JA, Du M, Cadillac JM, Bedwell DM, Rowe SM, Sorscher EJ, Fanucchi MV, 2014. Characterization of Defects in Ion Transport and Tissue Development in Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR)-Knockout Rats. PLOS ONE 9, e91253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooy I, Hennink WE, Storm G, Schiffelers RM, Mastrobattista E, 2012. Attaching the phage display-selected GLA peptide to liposomes: factors influencing target binding. Eur J Pharm Sci 45, 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YY, Lai SK, Suk JS, Pace A, Cone R, Hanes J, 2008a. Addressing the PEG mucoadhesivity paradox to engineer nanoparticles that “slip” through the human mucus barrier. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 47, 9726–9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YY, Lai SK, Suk JS, Pace A, Cone R, Hanes J, 2008b. Addressing the PEG mucoadhesivity paradox to engineer nanoparticles that “slip” through the human mucus barrier. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47, 9726–9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley SR, English D, Hu EL, Barbara PF, Belcher AM, 2000. Selection of peptides with semiconductor binding specificity for directed nanocrystal assembly. Nature 405, 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G, Griffiths AD, Hawkins RE, Hoogenboom HR, 1994. Making antibodies by phage display technology. Annual review of immunology 12, 433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Boylan NJ, Cai S, Miao B, Patel H, Hanes J, 2013. Scalable method to produce biodegradable nanoparticles that rapidly penetrate human mucus. J Control Release 170, 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Ito S, Kurogi-Hirayama M, Ohtsuki S, 2017. Identification of cyclic peptides for facilitation of transcellular transport of phages across intestinal epithelium in vitro and in vivo. J Control Release 262, 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Hansing J, Netz RR, DeRouchey JE, 2015. Particle transport through hydrogels is charge asymmetric. Biophys J 108, 530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.