Abstract

Objective:

To assess patient comfort speaking up about problems during hospitalization and to identify patients at increased risk of having a problem and not feeling comfortable speaking up.

Design:

Cross-sectional study

Setting:

Eight hospitals in Maryland and Washington D.C.

Participants:

Patients hospitalized at any one of 8 hospitals who completed the HCAHPS survey post-discharge.

Main outcome measures:

Response to the question “How often did you feel comfortable speaking up if you had any problems in your care?” grouped as: 1) no problems during hospitalization, 2) always felt comfortable speaking up, and 3) usually/sometimes/never felt comfortable speaking up.

Results:

Of 10,212 patients who provided valid responses, 4,958 (48.6%) indicated they had experienced a problem during hospitalization. Of these, 1,514 (30.5%) did not always feel comfortable speaking up. Predictors of having a problem during hospitalization included age, health status, and education level. Patients who were older, reported worse overall and mental health, were admitted via the Emergency Department, and did not speak English at home were less likely to always feel comfortable speaking up. Patients who were not always comfortable speaking up provided lower ratings of nurse communication (47.8 vs. 80.4;p<0.01), physician communication (57.2 vs. 82.6;p<0.01), and overall hospital ratings (7.1 vs. 8.7;p<0.01). They were significantly less likely to definitely recommend the hospital (36.7% vs. 71.7%;p<0.01) than patients who were always comfortable speaking up.

Conclusions:

Patients frequently experience problems in care during hospitalization and many do not feel comfortable speaking up. Creating conditions for patients to be comfortable speaking up may result in service recovery opportunities and improved patient experience. Such efforts should consider the impact of health literacy and mental health on patient engagement in patient-safety activities.

Introduction

It has been over a decade since ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm’ called for a redesign of the United States healthcare system to address major shortcomings in healthcare delivery.(1) This publication set forth key goals for the healthcare system, which include ensuring that healthcare is both safe and patient-centered. Greater engagement of patients and their families has been identified as a promising approach to improve the safety and patient-centeredness of healthcare. This strategy is based on the recognition that patients and their families often have important and unique insights about breakdowns in healthcare.(2–6) Patient perspectives of these breakdowns are therefore a valuable source of information that could be harnessed to address and prevent such occurrences.(7–9)

It has been well established that patients and their families have unique knowledge about instances when healthcare systems fall short in the goal of delivering safe and/or patient-centered care.(3,4,10) Defined as something that wrong in their care according to the patient, patient-perceived breakdowns include problems related to patient experience (e.g. information provision, provider relationship) and with technical aspects of healthcare (e.g., diagnosis and treatment).(10) Patients are often the only member of the care team who is aware of a breakdown in care, given that they are the only one who is present for the entirety of every care episode. As such, healthcare providers and systems are often unaware of breakdowns experienced by patients. Therefore, unless patients speak up about their experiences of breakdowns in care, opportunities to address problems as they occur and to learn from patients to improve the system of care for others may be missed.

Unfortunately, patients are often reluctant to speak up about breakdowns in care. Most patients who experience breakdowns in care do not bring their concerns to the responsible provider or file formal complaints about these events.(5,11,12) There are many reasons that patients are reluctant to speak up about breakdowns in care. These include not knowing whom to tell, expecting it will not make a difference, and feeling a need to focus their energy on their recovery.(5,13,14) In many cases, patients may not feel comfortable raising their concerns. Qualitative studies have identified some factors that influence patient comfort and willingness to speak up, such as provider demeanor, provider responsiveness, and patient confidence in their ability to identify breakdowns in care.(13–15) However, less is known about how other patient characteristics such as demographics, educational attainment and health status impact the likelihood of experiencing a breakdown in care, or comfort speaking up about such breakdowns.

Strategies are needed to overcome patients’ reluctance to speak up about breakdowns in care such that patients’ insights and knowledge about breakdowns can be used to make healthcare safer and more patient-centered. Developing such strategies requires a greater understanding of which patients are at risk for experiencing problems and not feeling comfortable speaking up, and how this impacts patient experience. We therefore undertook the present study to: 1) identify patient characteristics associated with experiencing a problem during a hospitalization and not feeling comfortable speaking up, and 2) examine whether comfort speaking up is associated with measures of patient experience of hospital care.

Methods

Study design and participants

We administered a newly developed item to assess comfort speaking up about problems in care as part of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey between May 2016 and April 2017. The HCAHPS survey is a standardized and publicly reported measure of patients’ perspectives of hospital care. Acute care hospitals in the United States are required to participate in the HCAHPS survey to receive full reimbursement under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS). The survey is administered to a random sample of eligible patients between 48 hours and 6 weeks after discharge at all participating hospitals.(16) The newly developed item was included as part of the standard CMS-mandated HCAHPS administration at 8 hospitals. At these hospitals, the HCAHPS survey is administered via telephone by a qualified third-party vendor.

The study was conducted at 8 hospitals located in Maryland and Washington D.C. The hospitals include 1 large (> 400 licensed beds), 4 medium (200–400 licensed beds), and 3 small (<200 licensed beds) hospitals located in inner-city (n = 1), urban (n = 2), suburban (n = 4), and rural (n = 1) settings. Five of the hospitals have teaching programs. Additional details about hospital characteristics are included in supplemental table 1.

This study was reviewed and approved by the MedStar Health Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

Dependent variable

We created the following question to assess patient comfort speaking up about problems in their care during hospitalization: “How often did you feel comfortable speaking up if you had any problems in your care?” The response options included: always, usually, sometimes, never, and did not have any problems. Respondents were grouped into 3 categories based on their response to this question: 1) no problems during hospitalization, 2) always felt comfortable speaking up, and 3) usually/sometimes/never felt comfortable speaking up about problems. We categorized respondents who answered usually, sometimes, or never felt comfortable speaking up together because our goal was to identify patient characteristics associated with any discomfort speaking up about problems (e.g., anything less than always comfortable speaking up).

Patient-level independent variables

Patient characteristics were collected as part of the HCAHPS survey. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, and language spoken at home. Clinical variables included self-reported overall health status and self-reported mental health status. Measures of patient experience that comprise core items of the HCAHPS survey were also collected including: nurse communication composite score, physician communication composite score, overall hospital rating (0–10 scale), and likelihood to recommend the hospital to friends or family. The nurse and physician communication composite score are calculated based on responses to questions about the frequency with which nurses (questions 1, 2, and 3) and physicians (questions 5, 6, and 7) treated the patient with courtesy and respect, listened carefully to the patient, and explained things in a way the patient could understand. (16)

Statistical analyses

We compared respondents in each of 3 response groups (no problem; always comfortable speaking up; not always comfortable speaking up) on age, education, race, ethnicity, self-rated overall and mental health, and selected patient experience items provided as part of the HCAHPS survey. Differences in the demographic characteristics and self-rated health, as well as in selected patient experience items, among patients who did or did not experience a problem during hospitalization, and among patients who were always or were less than always comfortable speaking up were examined using Chi-square tests for discrete variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. To account for multiple pairwise comparisons that can inflate type I error (i.e., comparing those who reported a problem to those who did not, and comparing those who were always comfortable speaking up to those who were not always comfortable), we selected a conservative threshold of p<0.01 to assess statistical significance.

Two binomial multivariable logistic regression models were created to assess the impact of demographic characteristics and self-reported health status on: 1) likelihood of having any problem during hospitalization, and 2) likelihood of not always feeling comfortable speaking up among patients who experienced a problem. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, language spoken at home, and self-rated overall and mental health status were considered as potential predictors. The adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the potential predictors were obtained, after controlling for site (e.g. hospital). Regression models included hospital site as a fixed effect (data not shown) and have accounted for clustered responses at the hospital level by calculating robust standard errors for the estimates of odds ratios. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics and distribution of responses to the ‘comfort speaking up’ item

A total of 11,693 responses to HCAHPS surveys were available from 8 hospitals during the study period, with a 28% overall survey response rate. Of these, 10,212 included a valid response to the comfort speaking up item. 87.3% of patients who started the HCAHPS survey and completed at least some items responded to this item. These responses constitute the sample for the present study. Overall, the mean age of the study population was 58.2 years old, 60.5% of respondents were female, and 46.1% were African-American.

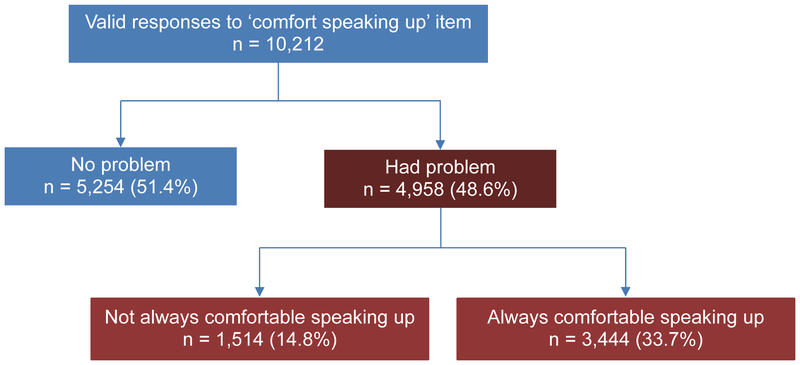

Nearly half of the respondents (n = 4,958; 48.6%) experienced a problem during hospitalization. While about two-thirds of patients who experienced a problem always felt comfortable speaking up (n = 3,444; 69.5%), almost one-third (n = 1,514; 30.5%) did not (Figure 1). Among the 1,514 patients who did not always feel comfortable speaking up, 723 (47.8%) usually felt comfortable speaking up, while 590 (39.0%) sometimes and 201 (13.3%) never felt comfortable speaking up (supplemental Table 2).

Figure 1.

Summary of responses to ‘comfort speaking up’ item.

Patient characteristics associated with experiencing a problem

Compared to patients who did not experience a problem, patients who indicated they had a problem during hospitalization were more likely to be younger (≤ 55 years), of white or Asian race, to have attained higher levels of education (some college or beyond), and to provide lower (good/fair/poor) ratings of their overall health. There were no significant differences in sex, language spoken at home, source of admission (e.g., through emergency department), or self-reported mental health between respondents who did or did not experience a problem during hospitalization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to responses to ‘comfort speaking up’ item.

| Characteristic | All respondents | p-value | Respondents who had a problem | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No problem n = 5,254 | Had problem n = 4,958 | Not always comfortable n = 1,514 | Always comfortable n = 3,444 | |||

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤ 35 | 741 (45.9) | 875 (54.1) | <0.01 | 249 (28.5) | 626 (71.5) | <0.01 |

| 36–45 | 380 (45.6) | 454 (54.4) | 119 (26.2) | 335 (73.8) | ||

| 46–55 | 744 (48.8) | 782 (51.2) | 231 (29.5) | 551 (70.5) | ||

| 56–65 | 1,213 (51.8) | 1,128 (48.2) | 338 (30.0) | 790 (70.0) | ||

| 66–75 | 1,275 (54.8) | 1,053 (45.2) | 319 (30.3) | 734 (69.7) | ||

| ≥ 76 | 901 (57.5) | 666 (42.5) | 258 (38.7) | 408 (61.3) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 3,134 (50.8) | 3,041 (49.2) | 0.08 | 932 (30.6) | 2,109 (69.4) | 0.83 |

| Male | 2,120 (52.5) | 1,917 (47.5) | 582 (30.4) | 1,335 (69.6) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1,945 (50.0) | 1,942 (50.0) | <0.01 | 604 (31.1) | 1,338 (68.9) | <0.01 |

| African-American | 2,508 (53.2) | 2,203 (46.8) | 626 (28.4) | 1,577 (71.6) | ||

| Asian | 63 (39.4) | 97 (60.6) | 40 (41.2) | 57 (58.8) | ||

| Other | 738 (50.8) | 716 (49.2) | 244 (34.1) | 472 (65.9) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 4,600 (50.8) | 4,459 (49.2) | <0.01 | 1,343 (30.1) | 3,116 (69.9) | 0.76 |

| Hispanic | 348 (57.4) | 258 (42.6) | 80 (31.0) | 178 (69.0) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| ≤ 8th grade | 256 (60.1) | 170 (39.9) | <0.01 | 58 (34.1) | 112 (65.9) | 0.15 |

| H.S. without grad | 666 (62.4) | 401 (37.6) | 135 (33.7) | 266 (66.3) | ||

| H.S. degree | 1,803 (55.9) | 1,421 (44.1) | 415 (29.2) | 1,006 (70.8) | ||

| Some college | 1,347 (49.3) | 1,385 (50.7) | 391 (28.2) | 994 (71.8) | ||

| College degree | 479 (43.3) | 628 (56.7) | 190 (30.3) | 438 (69.7) | ||

| > College degree | 476 (39.1) | 741 (60.9) | 239 (32.3) | 502 (67.7) | ||

| Language spoken at home | ||||||

| English | 4,721 (51.2) | 4,494 (48.8) | 0.20 | 1,327 (29.5) | 3,167 (70.5) | <0.01 |

| Non-English | 343 (53.8) | 294 (46.2) | 114 (38.8) | 180 (61.2) | ||

| Admission through ED* | ||||||

| Yes | 3,359 (51.5) | 3,169 (48.5) | 0.76 | 1,028 (32.4) | 2141 (67.6) | <0.01 |

| No | 1,739 (51.1) | 1,662 (48.9) | 438 (26.4) | 1,224 (73.6) | ||

| Overall health | ||||||

| Excellent | 797 (54.2) | 673 (45.8) | <0.01 | 137 (20.4) | 536 (79.6) | <0.01 |

| Very good | 1,353 (53.2) | 1,188 (46.8) | 311 (26.2) | 536 (73.8) | ||

| Good | 1,646 (50.4) | 1,617 (49.6) | 542 (33.5) | 1,075 (66.5) | ||

| Fair | 1,010 (50.8) | 978 (49.2) | 332 (34.0) | 646 (66.1) | ||

| Poor | 322 (44.4) | 404 (55.6) | 150 (37.1) | 254 (62.9) | ||

| Mental health | ||||||

| Excellent | 1,683 (52.3) | 1,533 (47.7) | 0.24 | 314 (20.5) | 1,219 (79.5) | <0.01 |

| Very good | 1,585 (51.8) | 1,474 (48.2) | 472 (32.0) | 1,002 (68.0) | ||

| Good | 1,358 (51.1) | 1,297 (48.9) | 461 (35.5) | 836 (64.5) | ||

| Fair | 447 (49.0) | 466 (51.0) | 178 (38.2) | 288 (61.8) | ||

| Poor | 89 (46.4) | 103 (53.6) | 50 (48.5) | 53 (51.5) | ||

Emergency Department (ED)

After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics and site (e.g., hospital), patient age (≤ 45 years old), race (white, Asian), ethnicity (non-Hispanic), higher educational attainment (some college or beyond), admission through the emergency department, and lower self-reported overall health (good/fair/poor vs. excellent or very good) were independently associated with having a problem during hospitalization. Patients older than 76 years old were nearly 50% less likely (OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.46–0.57) to experience a problem compared to younger (≤ 35 years old) patients. Increasing educational attainment was associated with a progressively increased likelihood of experiencing a problem. Patients who completed greater than a 4-year college degree were more than twice as likely (OR 2.19; 95% CI 1.64–2.91) to experience a problem as patients with less than 8th grade education. Lower ratings of overall health were associated with increased likelihood of having a problem, with patients in poor health at approximately 50% higher risk (OR 1.50; 95% CI 1.17–1.91) of having a problem during hospitalization than patients in excellent health (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of predictors of experiencing a problem during hospitalization, and comfort speaking up about problem(s).

| Patient characteristics | Problem during hospitalization Odds ratio (95% CI) | Not always comfortable speaking up Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤ 35 | REF | REF |

| 36–45 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) |

| 46–55 | 0.78 (0.64–0.94) | 0.96 (0.72–1.28) |

| 56–65 | 0.69 (0.57–0.85) | 0.94 (0.75–1.18) |

| 66–75 | 0.61 (0.52–0.70) | 1.01 (0.78–1.30) |

| ≥ 76 | 0.51 (0.46–0.57) | 1.33 (1.10–1.61) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | REF | REF |

| Female | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) |

| Race | ||

| White | REF | REF |

| Asian | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 1.37 (0.74–2.54) |

| African American | 0.77 (0.70–0.84) | 0.82 (0.73–0.93) |

| Other | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | REF | REF |

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.50–0.78) | 0.98 (0.74–1.30) |

| Education | ||

| ≤ 8th grade | REF | REF |

| Some high school, no degree | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | 1.26 (0.84–1.87) |

| High school degree | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 1.04 (0.75–1.44) |

| Some college, no degree | 1.38 (1.19–1.61) | 1.03 (0.69–1.53) |

| College (4 year) graduate | 1.70 (1.33–2.17) | 1.18 (0.89–1.55) |

| Greater than 4-yr college | 2.19 (1.64–2.91) | 1.40 (1.08–1.81) |

| Language spoken at home | ||

| Non-English | REF | REF |

| English | 1.09 (0.88–1.34) | 0.67 (0.50–0.90) |

| Admission through ED | ||

| No | REF | REF |

| Yes | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) |

| Overall health, self-rated | ||

| Excellent | REF | REF |

| Very good | 1.03 (0.97–1.52) | 1.22 (1.00–1.48) |

| Good | 1.22 (1.11–1.33) | 1.55 (1.28–1.87) |

| Fair | 1.19 (1.03–1.38) | 1.42 (1.03–1.98) |

| Poor | 1.50 (1.17–1.91) | 1.47 (1.18–1.82) |

| Mental health, self-rated | ||

| Excellent | REF | REF |

| Very good | 1.08 (0.97–1.19) | 1.85 (1.44–2.37) |

| Good | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 2.02 (1.80–2.27) |

| Fair | 1.21 (0.97–1.52) | 2.24 (1.93–2.60) |

| Poor | 1.18 (0.92–1.53) | 3.92 (2.82–5.45) |

Regression models included hospital site as a fixed effect (data not shown) and have accounted for clustered responses at the hospital level by calculating robust standard errors for the estimates of odds ratios.

Records with missing values for any predictor were excluded from the analysis.

ED = Emergency Department

Patient characteristics associated with comfort speaking up

Of the patients who experienced a problem, patients who were not always (usually, sometimes, or never) comfortable speaking up tended to be older, were more likely to be white or Asian, less likely to speak English at home, more likely to have been admitted through the emergency department, and more likely to provide lower (good/fair/poor) ratings of their overall and mental health (Table 1). After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics and site, older age (≥ 76 years old), not speaking English at home, admission through the emergency department, and reporting lower overall health (good/fair/poor vs. excellent), and mental health (very good/good/fair/poor vs. excellent) were all independently associated with not always feeling comfortable speaking up about problems during hospitalization (Table 2). Less than excellent mental health was very strongly associated with comfort speaking up. Patients with poor mental health were nearly four-times as likely to not always feel comfortable speaking up (OR 3.92; 95% CI 2.82–5.45) compared to patients with excellent mental health.

Comfort speaking up and core HCAHPS measures of patient experience

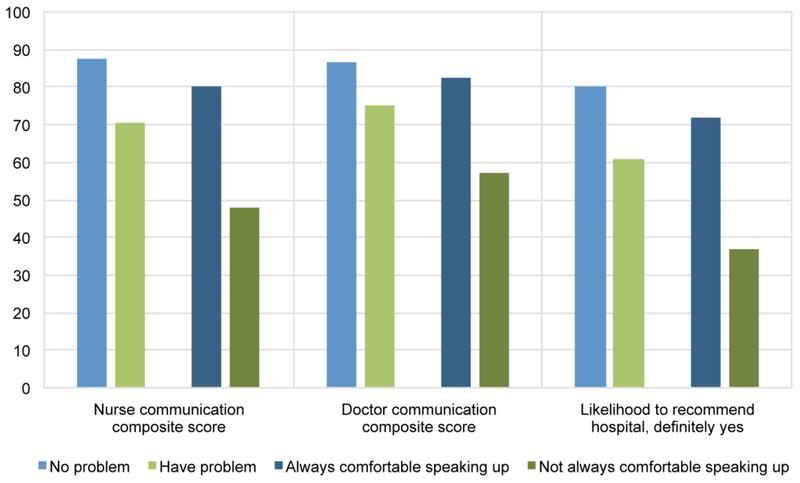

Patients who experienced a problem during their hospitalization provided lower ratings on selected patient experience (HCAHPS) measures compared to patients who reported no problems. This included nurse communication (mean composite score 70.5 vs. 87.7; p < 0.01), doctor communication (mean composite score 75.0 vs. 86.7; p < 0.01), overall hospital rating (8.2 vs. 9.2; p < 0.01), and likelihood to recommend the hospital to family or friends (61.0% vs. 80.1% responded ‘definitely yes’; p < 0.01), for patients who experienced a problem as compared to those who did not (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient experience (responses to HCAHPS items) according to problems in care and comfort speaking up.

Patients who did not always feel comfortable speaking up about problems provided significantly lower ratings on selected measures of patient experience compared to patients who experienced a problem but always felt comfortable speaking up. This pattern persisted across multiple domains of patient experience, including nurse communication (mean composite score 47.8 vs. 80.4; p < 0.01), physician communication (mean composite score 57.2 vs. 82.6; p < 0.01), overall hospital rating (7.1 vs. 8.7; p < 0.01), and likelihood to recommend the hospital (36.7 vs. 71.7% responded ‘definitely yes’; p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Discussion/Implications

In the present study of over 10,000 patients from 8 hospitals, we found that nearly half of respondents experienced a problem during hospitalization, suggesting that healthcare providers and systems who neglect to consider patients’ perceptions of care may be missing myriad opportunities for improvement. Partnering with patients to gain a deeper understanding of patient-perceived breakdowns in care could contribute to safer and more patient-centered healthcare. However, nearly one-third of those who experienced a problem did not always feel comfortable speaking up. As a result, the full potential of patients’ unique insights will not be realized without concerted efforts to overcome patient reluctance to speak up.

It is not surprising that patients who experienced a problem during their hospitalization provided lower ratings on patient experience measures across multiple domains (nurse communication, doctor communication, overall ratings, and likelihood to recommend the hospital). What is notable is that the patient experience scores of patients who had a problem but always felt comfortable speaking up approached those of patients that didn’t have a problem. This finding suggests that efforts designed to increase patient comfort speaking up may result in service recovery opportunities, with resultant improvements in patient experience measures. An alternative explanation is that behaviors that promote patient comfort speaking up (e.g.- high quality communication with providers) also lead to higher patient experience scores in other domains. In either case, further research is warranted to identify specific practices that support provision of patient-centered care, as indicated by patient experience surveys or patient comfort speaking up about problems.

Patients who had less than excellent health, were younger, and achieved higher educational attainment were more likely to have a problem during hospitalization in the present study. We cannot distinguish whether these findings are the result of specific patient populations being at higher risk of problems occurring in their care, or because some patients are more likely to detect problems. For example, the most highly educated patients (greater than 4-year college) were more than twice as likely to experience a problem during hospitalization. Although the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow definitive causal inference, it is unlikely that higher education levels result in a significantly higher frequency of problems. A more plausible interpretation is that patients with higher educational status, a close proxy for health literacy,(17) are better equipped to identify problems when they occur. It is also possible that more educated patients have a lower threshold of what they consider a problem. In other words, whether a patient experiences a problem, depends at least in part, on what they define as a problem. For populations of predominantly low health literacy, engaging patients to identify breakdowns in care may not be an effective means of learning about problems. In these instances, engaging family members or friends may help to overcome this limitation, as breakdowns in care are detected at a higher rate when friends or family members are involved. (10,18)

By comparison, being in worse overall health may be associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing a problem during hospitalization due to both increased detection of problems by patients, and increased risk of a problem occurring. Patients are known to rely on prior experiences of healthcare to inform their judgment of whether a problem has occurred. (13) Therefore, patients with lower overall health may be in a better position to identify problems than less experienced healthcare consumers. However, patients with lower overall health are also known to be at greater risk of adverse events and breakdowns in care, owing to their disease severity and complexity. (19) Patients with poor overall health status may therefore be an especially important target for initiatives to elicit and learn from patient-perceived breakdowns in care as they are both at high risk for these events to occur and may be particularly well positioned to detect them.

Efforts to learn from patient-perceived breakdowns in care must overcome patient reluctance to speak up about problems. Doing so requires an understanding of who is not always comfortable speaking up and why specific characteristics may contribute to patient reluctance to speak up. To that end, we identified patient factors (older age, non-English speaking, admission through the emergency department, less good overall and mental health) that are independently associated with not always feeling comfortable speaking up. Among these, less than excellent mental health was an especially strong predictor of not always feeling comfortable speaking up. This is in keeping with findings from studies of patient engagement in arenas beyond patient-safety, such as diabetes care, and COPD self-management in which poor mental health is a major barrier to patient engagement.(20,21) Our study highlights the need to identify effective approaches to overcome this barrier to patient engagement. It also suggests that effective mental health treatment may result in “spill-over” benefits to many domains of patient engagement, including patient safety as well as disease-specific self-management.

Our study has several strengths. First, the large sample drawn from 8 hospitals increases the generalizability of our findings. Second, we provide description of a novel item that can be administered as part of the HCAHPS survey to assess patient experience of problems and comfort speaking up. This may be useful for hospitals seeking to monitor interventions targeted at these issues. Despite these strengths, the results should be interpreted in light of a number of limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow definite conclusions regarding the directionality of the relationship between patient characteristics and experiencing a problem, or between patient experience measures and comfort speaking up. Our analyses are based on patient report of having experienced a problem; we did not elicit details of the nature of the problem(s), nor use other methods to validate that a problem had occurred. Similarly, patient-reported comfort speaking up may not equate to actual speaking up about a problem during hospitalization. We did not examine hospital- or provider-level factors that are likely to play a role in patient comfort speaking up. Finally, we do not have information available on HCAHPS survey non-respondents and therefore are unable to examine the extent or impact of response bias. However, it has been shown that higher response rates are associated with higher overall patient satisfaction. (22) We therefore expect that the impact of response bias would be to attenuate our findings; in other words, non-responders might be expected to report an even higher rate of problems during hospitalization than described in the present study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that patients commonly experience problems during hospitalization, and many patients do not always feel comfortable speaking up when problems occur. Further research is needed to identify effective approaches to increase patient comfort speaking up. Such efforts are likely to result in opportunities for service recovery, and improved patient experience in the hospital. Poor mental health is a particularly strong barrier to patient engagement in safety behaviors (e.g., speaking up about problems), as in other domains of patient engagement and self-care. Interventions targeted at improving mental and emotional health may therefore be a particularly fruitful approach to increasing patient engagement across a wide range of domains, including patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The study was supported by grant 4R18HS022757 (Drs. Mazor, Gallagher, and Smith) and by grant K08HS024596 (Dr. Fisher), from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- (1).Institute of Medicine (U S) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, Epstein AM, David-Kasdan J, Feibelmann S, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med 2008. July 15;149(2):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Iedema R, Allen S, Britton K, Gallagher TH. What do patients and relatives know about problems and failures in care? BMJ Qual Saf 2012. March 01;21(3):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Lawton R, O’Hara JK, Sheard L, Reynolds C, Cocks K, Armitage G, et al. Can staff and patient perspectives on hospital safety predict harm-free care? An analysis of staff and patient survey data and routinely collected outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf 2015. June 01;24(6):369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, Lemay CA, Firneno CL, Calvi J, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 2012. May 20;30(15):1784–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, Li JM, Aronson MD, Davis RB, et al. What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? Learning from patient-reported incidents. J GenIntern Med 2005. September 01; 20(9):830–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Garbutt J, Bose D, McCawley BA, Burroughs T, Medoff G. Soliciting patient complaints to improve performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2003. March 01;29(3):103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Flott KM, Graham C, Darzi A, Mayer E. Can we use patient-reported feedback to drive change? The challenges of using patient-reported feedback and how they might be addressed. BMJ Qual Saf 2017. June 01;26(6):502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gallagher TH, Mazor KM. Taking complaints seriously: using the patient safety lens. BMJ Qual Saf 2015. June 01;24(6):352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fisher K, Smith K, Gallagher T, Burns L, Morales C, Mazor K. We Want to Know: Eliciting Hospitalized Patients’ Perspectives on Breakdowns in Care. J Hosp Med 2017. August 01;12(8):603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wessel M, Lynoe N, Juth N, Helgesson G. The tip of an iceberg? A cross-sectional study of the general public’s experiences of reporting healthcare complaints in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ Open 2012. January 26;2(1):000489 Print 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fisher KA, Ahmad S, Jackson M, Mazor KM. Surrogate decision makers’ perspectives on preventable breakdowns in care among critically ill patients: A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2016. October 01;99(10):1685–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, Birks Y, Hall J, Peat M, et al. Speaking up about safety concerns: multi-setting qualitative study of patients’ views and experiences. Qual Saf Health Care 2010. December 01;19(6):e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lyndon A, Wisner K, Holschuh C, Fagan KM, Franck LS. Parents’ Perspectives on Navigating the Work of Speaking Up in the NICU. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2017. October 01;46(5):716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Burrows Walters C, Duthie EA. Patients’ Perspectives of Engagement as a Safety Strategy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017. November 01;44(6):712–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).HCAHPS: Patients’ perspectives of care survey. . Accessed March 7, 2018.

- (17).Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2005. February 01;20(2):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bardach NS, Lyndon A, Asteria-Penaloza R, Goldman LE, Lin GA, Dudley RA. From the closest observers of patient care: a thematic analysis of online narrative reviews of hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2015. December 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Graf J, von den Driesch A, Koch KC, Janssens U. Identification and characterization of errors and incidents in a medical intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005. August 01;49(7):930–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bos-Touwen I, Schuurmans M, Monninkhof EM, Korpershoek Y, Spruit-Bentvelzen L, Ertugrul-van der Graaf I, et al. Patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey study.PLoS One 2015. May 07;10(5):e0126400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Benzo RP, Kirsch JL, Dulohery MM, Abascal-Bolado B. Emotional Intelligence: A Novel Outcome Associated with Wellbeing and Self-Management in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016. January 01;13(1):10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Siddiqui ZK, Wu AW, Kurbanova N, Qayyum R. Comparison of Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems patient satisfaction scores for specialty hospitals and general medical hospitals: confounding effect of survey response rate. J Hosp Med 2014. September 01;9(9):590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.