Abstract

The maintenance of mitochondrial function is closely linked to the control of senescence. In our previous study, we uncovered a novel mechanism in which senescence amelioration in normal aging cells is mediated by the recovered mitochondrial function upon Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) inhibition. However, it remains elusive whether this mechanism is also applicable to senescence amelioration in accelerated aging cells. In this study, we examined the role of ATM inhibition on mitochondrial function in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) and Werner syndrome (WS) cells. We found that ATM inhibition induced mitochondrial functional recovery accompanied by metabolic reprogramming, which has been known to be a prerequisite for senescence alleviation in normal aging cells. Indeed, the induced mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming was coupled with senescence amelioration in accelerated aging cells. Furthermore, the therapeutic effect via ATM inhibition was observed in HGPS as evidenced by reduced progerin accumulation with concomitant decrease of abnormal nuclear morphology. Taken together, our data indicate that the mitochondrial functional recovery by ATM inhibition might represent a promising strategy to ameliorate the accelerated aging phenotypes and to treat age-related disease.

Keywords: ATM inhibition, HGPS, KU-60019, mitochondrial function, WS

INTRODUCTION

HGPS constitutes a genetic disorder caused by a point mutation (C1824T) in exon 11 of the LMNA gene (McClintock et al., 2006). This mutation leads to the generation of a truncated protein with a dominant negative effect on nuclear structure, resulting in irregular/enlarged nuclei (McClintock, Gordon et al., 2006). As these abnormalities comprise a pathogenic feature in HGPS, current research on HGPS is focused on developing drugs that can ameliorate the altered nuclear morphology. In particular, farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) have been identified to reverse the abnormal nuclear structure along with providing improvements in life span in HGPS mouse models (Lee et al., 2002; Passos et al., 2007; Wallace, 1994). However, the use of FTIs exhibits several detrimental side effects including centrosome separation defects and cytotoxicity (Verstraeten et al., 2011). Thus, effective drugs that can be used alone or in combination with FTIs are needed for the treatment of HGPS patients.

WS is an autosomal recessive disorder resulting from mutations in the WRN gene, which encodes a member of the RecQ subfamily of DNA helicase proteins (Gray et al., 1997). As WRN plays a crucial role in DNA repair and maintenance (McKenzie et al., 1995), WS patients with WRN-deficiency are prone to acquire mutations, consequently suffering from the elevated risk of cancer (McKenzie et al., 1995). Thus, the curative treatment of WS has been focused on the modulation of RecQ activities (Cocheme and Murphy, 2008); however, no effective therapeutic treatment has yet been identified for WS patients (Shimizu et al., 2003).

In our previous study, we performed high-throughput screening to identify compounds that allowed the alleviation of senescence in normal aging cells and identified an ATM inhibitor, KU-60019, as an effective agent (Kang et al., 2017). We revealed a novel mechanism in which senescence in normal aging cell is controlled by the recovered mitochondrial function upon the fine-tuning of ATM activity with KU-60019 (Kang et al., 2017). However, many questions remain to be addressed, such as whether ATM inhibition might exert the same effect in accelerated aging cells, or whether this restorative effect might be extended to ameliorate senescence-associated phenotypes in these cells. In this present study, we aimed to address the effects of ATM inhibition on the accelerated aging process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HGPS skin fibroblasts (AG03198 B; Coriell Cell Repositories, USA) and WS skin fibroblasts (AG03141 G; Coriell Cell Repositories) were used in this study. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 25 mM glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were also cultured in ambient air (20% O2) supplemented with 5% CO2. Confluent cells were split 1:4 and 1:2 during early and late passages, respectively. KU-60019 (S1570; Selleck Chem, USA) and DMSO (D8148; Sigma, USA) were diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 μM and 1.4 mM in the culture medium, respectively. As an alternative ATM inhibitor, CP-466722 (S2245; Selleck Chem) was diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 μM in the culture medium. The culture medium was changed every 4 days. At 14 days after drug treatment, cells were used for the functional analysis. The population doubling level (PDL) was 10 and 5.37, respectively, when HGPS skin fibroblasts and WS skin fibroblasts were initially purchased. Cells were considered to be young when the population doubling time was less than 2 days and the approximate PDL of young HGPS and WS fibroblasts was 14 and 9, respectively. Cells were considered to be senescent when the population doubling time was over 14 days, with the approximate PDL of senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts being 26 and 21, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Protein lysates were then separated on 4–12% gradient Tris-glycine mini protein gels (EC60355BOX; Invitrogen, USA) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (170-4156; Bio-Rad, USA) using a semidry apparatus (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with primary antibodies. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Proteins were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence solution (32106; Thermo Scientific, USA) using an ImageQuant LAS-4000 digital imaging system (GE Healthcare, USA). Primary antibodies used in this study included rabbit anti-ATM (phospho S1981; ab81292; 1:1,000 dilution; Abcam, UK), mouse anti-Lamin A/C antibody (MAB3211; 1:1,000 dilution; Millipore, USA), and rabbit anti-actin (A5060; 1:1000 dilution; Sigma). The secondary antibodies used in this study included HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2004; 1:4,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (sc-2302; 1:4,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The ratio of progerin to lamin A was quantitated using ImageJ (Collins, 2007).

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and autofluorescence

For quantitation of mitochondrial ROS, cells were incubated with 0.2 μM MitoSOX (M36008; Life Technologies, USA) for 30 min at 37°C, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized, collected in PBS, and analyzed on a FACSCaliber instrument (Becton Dickinson, USA). To measure MMP, cells were incubated with 0.3 μg/ml JC-1 (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37°C and prepared for flow cytometry analysis as previously described (Kang and Hwang, 2009). For quantitation of autofluorescence, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, collected in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results were analyzed using Cell Quest 3.2 software (Becton Dickinson).

Analysis of the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR)

The XFe24 flux analyzer and a Prep Station (Seahorse Bioscience XFe24 Instrument, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were distributed into each well of an XFe24 cell-culture plate from the XF24 FluxPak (100850-001; Seahorse Bioscience) and then cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at a temperature of 37°C for 16 h. Next, the medium was replaced by XF Assay medium (102365-100; Seahorse Bioscience), which lacked glucose, and the cells were then cultured for another 1 h in the same incubator. The ECAR was measured using an XF Glycolysis Stress Test kit (102194-100; Seahorse Bioscience) andreported in mpH/min.

Senescence-associated (SA)-β-gal staining

X-Gal cytochemical staining for senescence associated (SA)-β-gal was performed as previously described (Debacq-Chainiaux et al., 2009). The cells were fixed in 3% formaldehyde for 5 min and then stained with freshly prepared SA-β-gal staining solution overnight at 37°C according to the manufacturer’s protocols (9860; Cell Signaling Technology, USA). The number of SA-β-gal-positive cells in randomly selected fields was expressed as a percentage of all cells counted.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence assessment, cells were plated on Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slides (154526; Thermo Fischer Scientific), washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 15 min, and blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum in PBS for 1 h. After incubation with mouse anti-Lamin A/C antibody (MAB3211; 1:1,000 dilution; Millipore) overnight at 4°C, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS three times and incubated with Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (711-585-152; 1:400 dilution; Jackson Laboratories, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Coverslips were washed with ice-cold PBS four times and then mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade reagent (P36934; Invitrogen). Images were captured using a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany).

Neutral comet assay

Neutral comet assays were performed using a Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis Assay kit (4250-050-K; Trevigen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols, with minor modifications. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were diluted in 0.5 ml ice-cold PBS. A cell suspension (50 μl) was resuspended in 500 μl LMAgarose (4250-050-02; R&D Systems, USA) and rapidly spread on slides. DNA was stained with SYBR-gold (S-11494; Life Technologies), and olive tail moments (expressed in arbitrary units) were calculated by counting 100–200 cells per condition and then analyzed using Metafer4 software (MetaSystems, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using a standard statistical software package (SigmaPlot 12.5; Systat Software, USA). Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA test was used to determine whether differences were significant.

RESULTS

Functional recovery of mitochondria by ATM inhibition in accelerated aging cells

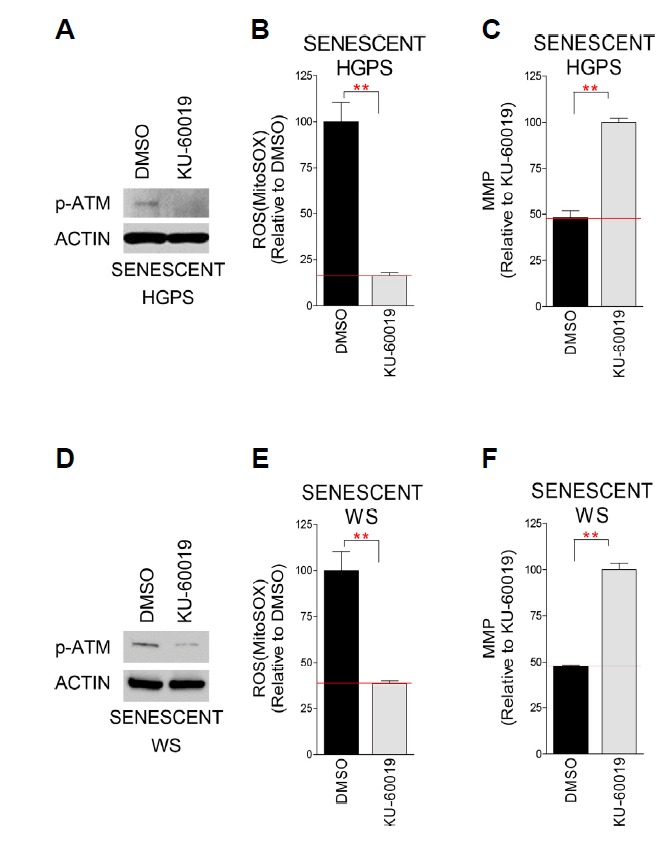

As we initially found that mitochondrial functional recovery in normal aging cells was preceded by ATM inhibition (Kang et al., 2017), we evaluated whether ATM inhibition could ameliorate mitochondrial function in senescent HGPS or WS cells. First, we tested the specificity of KU-60019 as an ATM inhibitor. ATM inhibition with KU-60019 reduced the levels of phosphorylated ATM (p-ATM), confirming its specificity as an ATM inhibitor (Figs. 1A and 1D). Next, to evaluate the functional status of mitochondria, ROS levels and MMP were monitored (Rottenberg and Wu, 1998; Yoo and Jung, 2018). Consistent with the results in normal aging cells (Kang et al., 2017), KU-60019 treatment significantly reduced ROS levels and increased MMP, suggestive of mitochondrial functional recovery in these cells (Figs. 1B, 1C, 1E and 1F).

Fig. 1. Functional recovery of mitochondria by ATM inhibition in senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts.

Specificity of KU-60019 as an ATM inhibitor in senescent HGPS (A) and WS (D) fibroblasts. Flow cytometric analysis of mitochondrial ROS levels using MitoSOX in senescent HGPS (B) and WS (E) fibroblasts (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Mean ± S.D., N = 3. Flow cytometric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 in senescent HGPS (C) and WS (F) fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3.

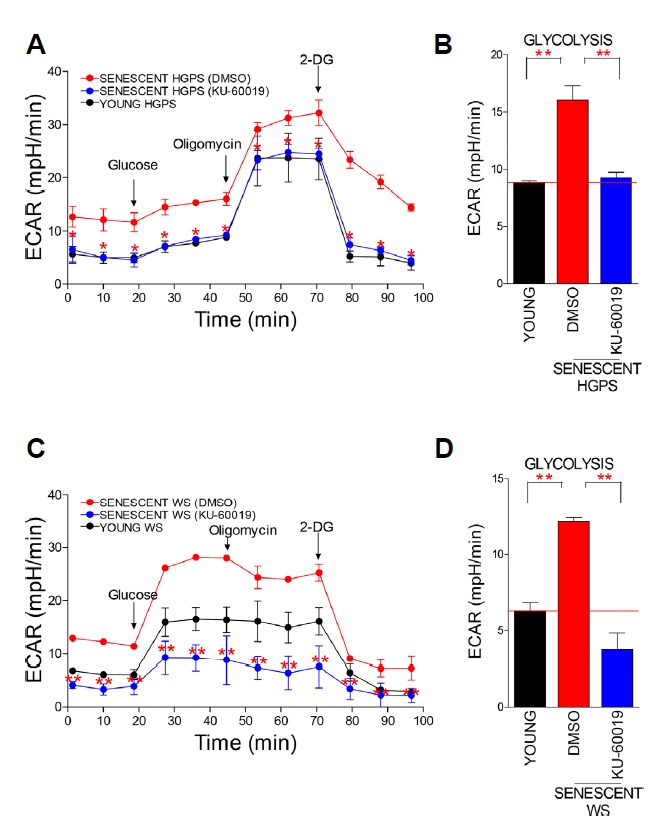

HGPS fibroblasts exhibit profound metabolic alterations including metabolic reprogramming from oxphos to glycolysis, causing HGPS cells to depend more on glycolysis as an energy source (Rivera-Torres et al., 2013). Furthermore, WS cells show altered mitochondrial function including reduced ATP production and increased electron leakage (Li et al., 2014), which reflects altered mitochondrial metabolism (Seo et al., 2010). To assess the changes in mitochondrial metabolism, we examined the glycolysis level of cells by measuring ECAR (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). The observed ECAR of senescent fibroblasts was higher than that of young fibroblasts, implying that senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts exhibited an increased dependency on glycolysis to meet energy demands (Figs. 2A and 2C; black line vs. red line). However, ECAR was restored to that of young fibroblasts upon KU-60019 treatment, implying the functional recovery of mitochondrial metabolism (Figs. 2A and 2C; black line vs. blue line). The analyzed glycolysis level also showed that ATM inhibition decreased the dependency on glycolysis (Figs. 2B and 2D).

Fig. 2. ATM inhibition induces metabolic reprogramming in senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts.

Measurement of ECAR in HGPS (A) and WS (C) fibroblasts (black line: young cells, red line: DMSO-treated senescent cells, and blue line: KU-60019-treated senescent cells) (*P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3. Measurement of the glycolysis level in HGPS (B) and WS (D) fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3.

Taken together, these data clearly illustrate that ATM inhibition is effective in recovering mitochondrial function in accelerated aging cells.

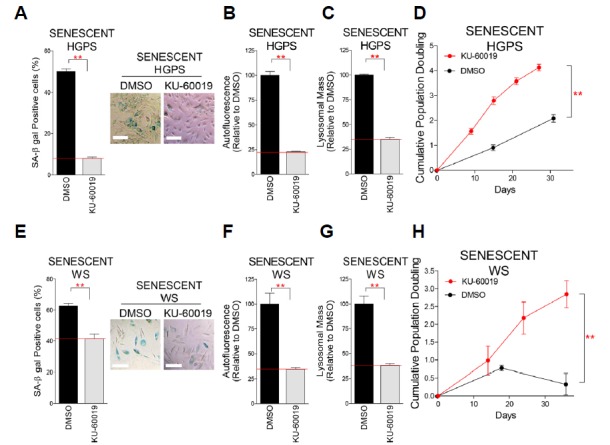

ATM as a potential target for ameliorating senescence in accelerated aging cells

Mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming, preceded by ATM inhibition, has been shown to be a prerequisite for senescence alleviation (Kang et al., 2017). As we observed mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming in HGPS and WS cells upon KU-60019 treatment, we conjectured that the induced mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming would ameliorate senescence-associated phenotypes. First, we examined SA-β-gal activity as a senescence marker (Dimri et al., 1995). The percentage of SA-β-gal positive cells was significantly reduced upon KU-60019 treatment (Figs. 3A and 3E). Next, as lipofuscin accumulation constitutes another senescence marker (Brunk and Terman, 2002), we examined the lipofuscin level through measuring intracellular levels of autofluorescence (Tohma et al., 2011). Notably, ATM inhibition with KU-60019 significantly reduced lipofuscin accumulation (Figs. 3B and 3F). As the increase in lysosome number and size constitutes one of the most characteristic changes observed with senescence (Robbins et al., 1970), we included the lysosomal mass as an additional senescence-associated marker. ATM inhibition with KU-60019 significantly reduced the lysosomal mass (Figs. 3C and 3G). Finally, to clarify the functional recovery of senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts, we examined the cumulative population doubling (CPD). KU-60019 treatment significantly increased CPD (Figs. 3D and 3H).

Fig. 3. ATM as a potential target for ameliorating senescence in senescent HGPS and WS fibroblasts.

Quantification of SA-β gal positive cells in senescent HGPS (A) and WS (E) fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test; scale bar 20: μm). Means ± S.D., N = 3. Flow cytometric analysis of autofluorescence in senescent HGPS (B) and WS (F) fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3. Flow cytometric analysis of lysosomal mass in senescent HGPS (C) and WS (G) fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3. Effects of KU-60019 treatment on CPD in senescent HGPS (D) and WS (H) fibroblasts. (**P < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Means ± S.D., N = 3.

We then examined whether ATM inhibition with KU-60019 would improve the mitochondrial function in young fibroblasts. ATM inhibition with KU-60019 reduced the levels of phosphorylated ATM (p-ATM) in young fibroblasts (Supplementary Figs. S1A and S1D), consistent with the results in senescent fibroblasts (Figs. 1A and 1D). We measured ROS levels and MMP to assess mitochondrial function (Rottenberg and Wu, 1998). KU-60019 treatment significantly reduced ROS levels and increased MMP, suggestive of mitochondrial functional enhancement in young fibroblasts (Supplementary Figs. S1B, S1C, S1E and S1F). However, ROS reduction by KU-60019 treatment was less effective in young than senescent fibroblasts (31.3% vs. 83.6% reduction in HGPS and 32.7% vs. 61.7% reduction in WS), as was MMP increase by KU-60019 treatment (17.2% vs. 51.8% increase in HGPS and 35.4% vs. 52.5% increase in WS)(Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). These data suggest that KU-60019 treatment enhances mitochondrial function in young fibroblasts, provided ATM activity was adjusted to a proper level.

Finally, we examined whether other ATM inhibitors yielded similar phenotypes as those observed after KU-60019 treatment. CP-466722 was selected an alternative ATM inhibitor (Weber and Ryan, 2015). CP-466722 treatment yielded recovered mitochondrial function as shown by the decreased ROS levels and the increased MMP (Supplementary Figs. S2A, S2B, S2D and S2E). Furthermore, CP-466722 treatment significantly decreased the lipofuscin accumulation (Supplementary Figs. S2C and S2F), suggesting that CP-466722 as another ATM inhibitor afforded similar phenotypes as KU-60019.

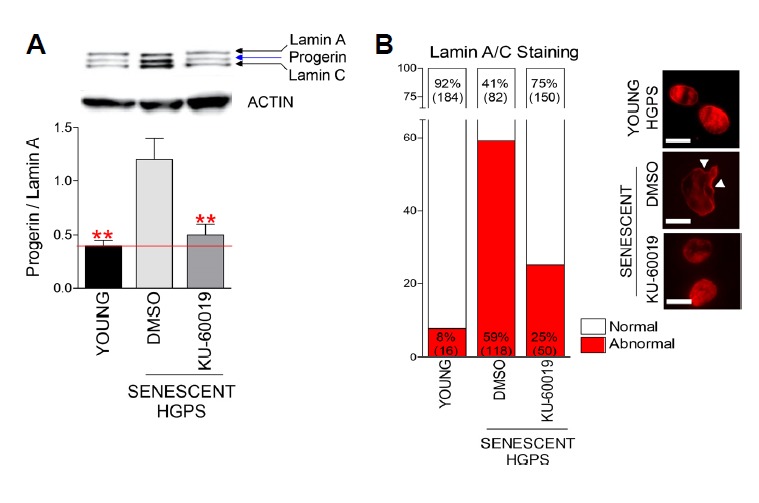

Restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition in accelerated aging cells

HGPS is caused by a mutation in LMNA that produces an aberrant lamin A protein, progerin (McClintock et al., 2006). Progerin accumulation leads to an aberrant nuclear morphology, which comprises the primary cause of HGPS disease progression (McClintock et al., 2006). Thus, therapeutic approaches against HGPS have been focused on the identification of pathways, which can interrupt progerin synthesis or activate progerin removal (Collins, 2016; Harhouri et al., 2018). Lipofuscin has been known to inhibit progerin removal process and further aggravate HGPS phenotypes (Skoczynska et al., 2015). As we observed the reduced lipofuscin accumulation by ATM inhibition, we conjectured that this restorative effect could reduce progerin accumulation. Thus, we examined the ratio of progerin to lamin A, which is a widely used criterion to determine progerin accumulation level in HGPS (Reunert et al., 2012). Senescent HGPS fibroblasts exhibited the higher ratio of progerin to lamin A than young cells, whereas KU-60019 treatment significantly decreased the ratio, suggesting the amelioration of HGPS pathologic features (Fig. 4A). We then examined the frequency of abnormal nuclear morphology to assess the effect of the decreased progerin accumulation on nuclear morphology. Lamin A/C antibody staining was performed to visualize nuclear morphology. Senescent HGPS fibroblasts exhibited the higher frequency of abnormal nuclear shapes than young cells, whereas KU-60019 treatment markedly decreased the frequency, suggestive of restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition on progerin accumulation and nuclear morphology in senescent HGPS fibroblasts.

(A) The ratio of progerin to lamin A as a criterion to determine disease severity in HGPS. (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Means ± S.D., N = 3. (B) Measurement of abnormal nuclear structures (red: lamin A/C, arrow head: abnormal nuclear structure, scale bar: 5 μm). N = 200. Cells were treated with DMSO or 0.5 μM KU-60019 for 14 days.

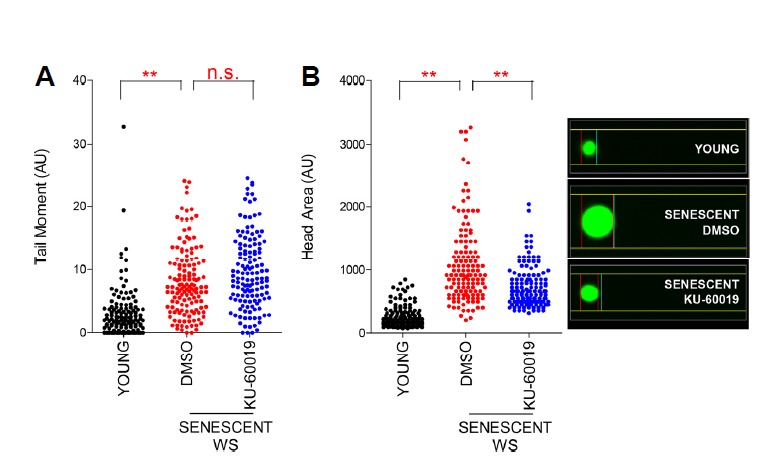

WS is caused by a mutation in a gene coding for WRN, which localizes to the sites of damaged DNA and participates in multiple DNA repair pathways (Lachapelle et al., 2011; Oshima et al., 2002). As ATM is a master regulator of DNA damage response (Shiloh, 2006), ATM inhibition could impair DNA damage repair, thereby leading to DNA damage accumulation. To exclude the possible adverse effect, a neutral comet assay was performed (Azqueta et al., 2014). Senescent WS fibroblasts exhibited longer comet tail moment, suggestive of higher DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) levels, than young WS fibroblasts (Fig. 5A). However, KU-60019 treatment did not increase the comet tail moment, excluding the possible adverse effect of ATM inhibition (Fig. 5A). Next, as nuclear size is known to increase as a function of senescence (Mitsui and Schneider, 1976), we examined the comet head area to assess nuclear size indirectly. Senescent WS fibroblasts exhibited larger head area than young cells, whereas KU-60019 treatment significantly restored the head area size to that of young cells, suggesting the restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition on DNA DSBs and nuclear size in senescent WS fibroblasts.

(A) Neutral comet assay to measure tail moment (A) and head area (B) in WS fibroblasts (**P < 0.01, n.s.: not significant, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Means ± S.D., N = 100. Cells were treated with DMSO or 0.5 μM KU-60019 for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

Progeroid syndromes including Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) or Werner syndrome (WS) are genetic diseases characterized by clinical features and phenotypes of physiological aging at an early age (Benhammou et al., 2007). Although the genetic causes of accelerated aging have been partially resolved, an essential therapeutic approach still remains elusive. Given the findings that accelerated aging is characterized by features resembling normal aging (Drechsel and Patel, 2009), the molecular mechanism underlying normal aging has been considered to provide important evidence toward understanding accelerated aging. In our previous study, we revealed a novel mechanism in which senescence is controlled by the recovered mitochondrial function (Kang et al., 2017). Support for this finding is evident from the observation that a decline in mitochondrial quality is correlated with the development of age-related diseases (Sahin and Depinho, 2010). In the present study, we found that ATM inhibition in accelerated aging cells induced mitochondrial functional recovery with mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming, a prerequisite for senescence alleviation in normal aging cells. Indeed, the induced mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming was accompanied by senescence amelioration in accelerated aging cells. To our knowledge, the present study provides the first demonstration that mitochondrial functional recovery via the regulation of ATM activity might represent a valid strategy to ameliorate senescent phenotypes in accelerated aging cells.

A common feature of HGPS is the defect in nuclear morphology, which is generated by a truncated lamin A protein, progerin (McClintock et al., 2006). Thus, the strategy to remove the accumulated progerin comprises one of the major therapeutics for HGPS patients (Harhouri et al., 2018). In our previous study, we found that ATM inhibition facilitated the assembly of the V1 and V0 domains in V-ATPase with concomitant re-acidification of the lysosome (Kang et al., 2017). In turn, the re-acidification of lysosomal pH restored the lysosome/autophagy system, which is impaired during senescence (Kang et al., 2017). Furthermore, in this study, we found that ATM inhibition reduced lipofuscin accumulation. Lipofuscin acts as a sink for newly generated hydrolytic enzymes, thereby aggravating lysosomal activity (Brunk and Terman, 2002). Thus, decreased lipofuscin accumulation suggests the sustained lysosomal activity without further deterioration. Indeed, this restorative effect was evidenced by the reduced progerin accumulation with concomitant amelioration of abnormal nuclear morphology. Although the above is our preferred explanation, it remains possible that reduced ROS levels by ATM inhibition can directly affect nuclear morphology. ROS is known to induce abnormal nuclear morphology through the oxidation of conserved cysteine residues in lamin A (Pekovic et al., 2011); thus, the reduction in ROS level, preceded by ATM inhibition, might induce the decrease in the frequency of abnormal nuclear morphology by preventing the oxidation of cysteine residues in lamin A.

ATM acts as a sensor of DNA DSBs and functions as a core component of DNA damage response (DDR) signaling pathway, which trigger cellular responses including DNA repair, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Shiloh and Lederman, 2016). Therefore, for therapeutic targeting of ATM, its activities should be adjusted using sophisticated strategies. The need for this careful approach can be inferred by evidences that WS is a genetic disorder resulting from a mutation in WRN gene, which acts as a sensor of DNA DSBs and takes part in DNA repair pathways (Lachapelle et al., 2011; Oshima et al., 2002). Accordingly, though we demonstrated that finely tuned ATM activity was beneficial in ameliorating senescence, the potential risk of ATM inhibition remains. In the present study, we found that KU-60019 treatment did not increase the comet tail moment in WS fibroblast, excluding the possible adverse effect of ATM inhibition. On the contrary, it restored the head area size to that of young cells, suggesting the restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition. Thus, we propose that the therapeutic application of ATM inhibitors would be beneficial in treating patients with WS, provided its activity could be adjusted to a critical level.

In summary, our findings confirmed that mitochondrial functional recovery via ATM inhibition might constitutes a valid therapeutic strategy to alleviate senescence in accelerated aging cells. Furthermore, restorative effect afforded by ATM inhibition was observed in HGPS cells as evidenced by reduced progerin accumulation with decreased frequency of abnormal nuclear shapes. Taken together, our results provide evidence that the proper control of ATM activity may represent a therapeutic target for alleviating senescence in accelerated aging cells and might be clinically applicable to control age-related diseases.

Supplementary data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07040293) and an Incheon National University research grant (2018-0409).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Azqueta A., Slyskova J., Langie S.A.S., O’Neill Gaivão I., Collins A. Comet assay to measure DNA repair: approach and applications. Front Genet. 2014;5:288. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhammou V., Tardieu M., Warszawski J., Rustin P., Blanche S. Clinical mitochondrial dysfunction in uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers following perinatal exposure to nucleoside analogues. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2007;48:173–178. doi: 10.1002/em.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand Martin D., Nicholls David G. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk U.T., Terman A. Lipofuscin: mechanisms of age-related accumulation and influence on cell function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:611–619. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocheme H.M., Murphy M.P. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1786–1798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F.S. Seeking a cure for one of the rarest diseases: progeria. Circulation. 2016;134:126–129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins T.J. ImageJ for microscopy. BioTechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debacq-Chainiaux F., Erusalimsky J.D., Campisi J., Toussaint O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-[beta]gal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:1798–1806. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri G.P., Lee X., Basile G., Acosta M., Scott G., Roskelley C., Medrano E.E., Linskens M., Rubelj I., Pereira-Smith O. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel D.A., Patel M. Differential contribution of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes to reactive oxygen species production by redox cycling agents implicated in parkinsonism. Toxicol Sci. 2009;112:427–434. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M.D., Shen J.C., Kamath-Loeb A.S., Blank A., Sopher B.L., Martin G.M., Oshima J., Loeb L.A. The werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nat Genet. 1997;17:100–103. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhouri K., Frankel D., Bartoli C., Roll P., De Sandre-Giovannoli A., Lévy N. An overview of treatment strategies for Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria syndrome. Nucleus. 2018;9:246–257. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2018.1460045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.T., Hwang E.S. Nicotinamide enhances mitochondria quality through autophagy activation in human cells. Aging Cell. 2009;8:426–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.T., Park J.T., Choi K., Kim Y., Choi H.J.C., Jung C.W., Lee Y.-S., Park S.C. Chemical screening identifies ATM as a target for alleviating senescence. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:616–623. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle S., Gagné J.-P., Garand C., Desbiens M., Coulombe Y., Bohr V.A., Hendzel M.J., Masson J.-Y., Poirier G.G., Lebel M. Proteome-wide identification of WRN-interacting proteins in untreated and nuclease-treated samples. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1216–1227. doi: 10.1021/pr100990s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.C., Yin P.H., Chi C.W., Wei Y.H. Increase in mitochondrial mass in human fibroblasts under oxidative stress and during replicative cell senescence. J Biomed Sci. 2002;9:517–526. doi: 10.1007/BF02254978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Iglesias-Pedraz J.M., Chen L.-Y., Yin F., Cadenas E., Reddy S., Comai L. Downregulation of the werner syndrome protein induces a metabolic shift that compromises redox homeostasis and limits proliferation of cancer cells. Aging Cell. 2014;13:367–378. doi: 10.1111/acel.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock D., Gordon L.B., Djabali K. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria mutant lamin A primarily targets human vascular cells as detected by an anti-Lamin A G608G antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2154–2159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie R., Fried M.W., Sallie R., Conjeevaram H., Di Bisceglie A.M., Park Y., Savarese B., Kleiner D., Tsokos M., Luciano C., et al. Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1099–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui Y., Schneider E.L. Increased nuclear sizes in senescent human diploid fibroblast cultures. Exp Cell Res. 1976;100:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima J., Huang S., Pae C., Campisi J., Schiestl R.H. Lack of WRN results in extensive deletion at nonhomologous joining ends. Cancer Res. 2002;62:547–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos J.F., Saretzki G., Ahmed S., Nelson G., Richter T., Peters H., Wappler I., Birket M.J., Harold G., Schaeuble K., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction accounts for the stochastic heterogeneity in telomere-dependent senescence. PLOS Biol. 2007;5:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekovic V., Gibbs-Seymour I., Markiewicz E., Alzoghaibi F., Benham A.M., Edwards R., Wenhert M., von Zglinicki T., Hutchison C.J. Conserved cysteine residues in the mammalian lamin A tail are essential for cellular responses to ROS generation. Aging Cell. 2011;10:1067–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reunert J., Wentzell R., Walter M., Jakubiczka S., Zenker M., Brune T., Rust S., Marquardt T. Neonatal progeria: increased ratio of progerin to lamin A leads to progeria of the newborn. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:933–937. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Torres J., Acín-Perez R., Cabezas-Sánchez P., Osorio F.G., Gonzalez-Gómez C., Megias D., Cámara C., López-Otín C., Enríquez J.A., Luque-García J.L., et al. Identification of mitochondrial dysfunction in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome through use of stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture. J Proteomics. 2013;91:466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins E., Levine E.M., Eagle H. Morphologic changes accompanying senescence of cultured human diploid cells. J Exp Med. 1970;131:1211–1222. doi: 10.1084/jem.131.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg H., Wu S. Quantitative assay by flow cytometry of the mitochondrial membrane potential in intact cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin E., Depinho R.A. Linking functional decline of telomeres, mitochondria and stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2010;464:520–528. doi: 10.1038/nature08982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo A.Y., Joseph A.-M., Dutta D., Hwang J.C.Y., Aris J.P., Leeuwenburgh C. New insights into the role of mitochondria in aging: mitochondrial dynamics and more. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2533–2542. doi: 10.1242/jcs.070490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y. The ATM-mediated DNA-damage response: taking shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y., Lederman H.M. Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T): An emerging dimension of premature ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;33:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K., Matsubara K., Ohtaki K., Fujimaru S., Saito O., Shiono H. Paraquat induces long-lasting dopamine overflow through the excitotoxic pathway in the striatum of freely moving rats. Brain Res. 2003;976:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoczynska A., Budzisz E., Dana A., Rotsztejn H. New look at the role of progerin in skin aging. Prz Menopauzalny. 2015;14:53–58. doi: 10.5114/pm.2015.49532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohma H., Hepworth A.R., Shavlakadze T., Grounds M.D., Arthur P.G. Quantification of ceroid and lipofuscin in skeletal muscle. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:769–779. doi: 10.1369/0022155411412185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten V.L.R.M., Peckham L.A., Olive M., Capell B.C., Collins F.S., Nabel E.G., Young S.G., Fong L.G., Lammerding J. Protein farnesylation inhibitors cause donut-shaped cell nuclei attributable to a centrosome separation defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019532108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D.C. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in human evolution and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8739–8746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A.M., Ryan A.J. ATM and ATR as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;149:124–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S.M., Jung Y.K. A molecular approach to mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics. Mol Cells. 2018;41:18–26. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.