Key Points

Bcor insufficiency promotes initiation and progression of MDS.

Bcor insufficiency cooperates with Tet2 loss in the pathogenesis of MDS.

Abstract

BCOR, encoding BCL-6 corepressor (BCOR), is X-linked and targeted by somatic mutations in various hematological malignancies including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). We previously reported that mice lacking Bcor exon 4 (BcorΔE4/y) in the hematopoietic compartment developed NOTCH-dependent acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Here, we analyzed mice lacking Bcor exons 9 and 10 (BcorΔE9-10/y), which express a carboxyl-terminal truncated BCOR that fails to interact with core effector components of polycomb repressive complex 1.1. BcorΔE9-10/y mice developed lethal T-ALL in a similar manner to BcorΔE4/y mice, whereas BcorΔE9-10/y hematopoietic cells showed a growth advantage in the myeloid compartment that was further enhanced by the concurrent deletion of Tet2. Tet2Δ/ΔBcorΔE9-10/y mice developed lethal MDS with progressive anemia and leukocytopenia, inefficient hematopoiesis, and the morphological dysplasia of blood cells. Tet2Δ/ΔBcorΔE9-10/y MDS cells reproduced MDS or evolved into lethal MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms in secondary recipients. Transcriptional profiling revealed the derepression of myeloid regulator genes of the Cebp family and Hoxa cluster genes in BcorΔE9-10/y progenitor cells and the activation of p53 target genes specifically in MDS erythroblasts where massive apoptosis occurred. Our results reveal a tumor suppressor function of BCOR in myeloid malignancies and highlight the impact of Bcor insufficiency on the initiation and progression of MDS.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

BCOR is a corepressor for BCL6, a key transcriptional factor required for the development of germinal center B cells.1,2 Recent extensive analyses of the BCOR complex revealed that BCOR also functions as a component of PRC1.1, a noncanonical PRC1, which monoubiquitinates histone H2A.3-5 BCOR and its closely related homolog, BCOR-like 1 (BCORL1) are located on chromosome X and are frequently targeted by somatic mutations in patients with various hematological malignancies. BCOR mutations have been reported in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a normal karyotype (3.8%),6 secondary AML (8%),7 myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS; 4.2%),8 chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (7.4%),8 extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (21% to 32%),9,10 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (2.2%),11 and T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (5% to 8%).12,13 Most BCOR mutations result in stop codon gains, frameshift insertions or deletions, splicing errors, and gene loss, leading to the loss of BCOR function.8 BCOR mutations also lead to reduced messenger RNA (mRNA) levels, possibly because of the activation of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway.8 BCORL1 has been implicated in AML and MDS in a similar manner to BCOR.8,14 Somatic mutations of BCOR are frequently associated with DNMT3A mutations in AML with a normal karyotype6 and mutations in DNMT3A, RUNX1, TET2, and STAG28,15,16 in MDS.

In order to understand the pathophysiological functions of BCOR mutants in hematological malignancies, several mouse models have recently been analyzed. The genomic characterization of Eμ-Myc mouse lymphoma identified Bcor as a Myc cooperative tumor-suppressor gene.17 We previously generated mice missing Bcor exon 4 (BcorΔE4/y) in the hematopoietic compartment, expressing a variant BCOR lacking a region including the BCL6-binding domain, and found that BcorΔE4/y mice had a strong propensity to develop acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) mostly in a NOTCH-dependent manner, indicating a tumor suppressor role for BCOR in the pathogenesis of T-lymphocyte malignancies.18 In thymocytes, BCOR appeared to be recruited to many of the NOTCH1 targets and antagonized their transcriptional activation.18 Correspondingly, BCOR and BCORL1 are targeted by somatic mutations in pediatric T-ALL (4.8%).19 BCOR has also been shown to restrict myeloid proliferation and differentiation in cultures using a conditional loss-of-function allele of Bcor in which exons 9 and 10 are missing (BcorΔE9-10).20 This mutant Bcor allele generates a truncated protein that lacks the region required for the interaction with PCGF1 and other core components of PRC1.1, and mimics some of the pathogenic mutations observed in patients with hematological malignancies.20 However, the role of BCOR in hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies has not been rigorously tested in BcorΔE9-10 mice.

In the present study, we investigated the function of BCOR using BcorΔE9-10 mice and tested the impact of the concurrent disruption of Bcor and Tet2 on the pathogenesis of MDS. Our results clearly demonstrate a tumor suppressor function of BCOR in myeloid malignancies.

Materials and methods

Mice and generation of hematopoietic chimeras

Conditional Bcor alleles (Bcorfl), which contain LoxP sites flanking Bcor exon 418 and Bcor exons 9 and 10,20 respectively, have been used previously. Bcorfl mice were backcrossed at least 6 times onto a C57BL/6 (CD45.2) background. Tet2 conditional knockout mice (Tet2fl/fl)21 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. In the conditional deletion of Bcor and Tet2, mice were crossed with Rosa26::Cre-ERT mice (TaconicArtemis GmbH). In order to generate hematopoietic chimeras, we transplanted wild-type (WT), Bcorfl/y;Cre-ERT, or Tet2fl/fl;Cre-ERT bone marrow (BM) cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice and deleted Bcor or Tet2 at 4 weeks posttransplantation by intraperitoneally injecting 100 μL of tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil at a concentration of 10 mg/mL for 5 consecutive days. Littermates were used as controls. C57BL/6 mice congenic for the Ly5 locus (CD45.1) were purchased from Sankyo-Laboratory Service. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with our institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Review Board for Animal Experiments of Chiba University (approval ID: 29-289).

Accession numbers

RNA sequencing, chromatin immunoprecipitation/DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq), and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing data were deposited in DNA Data Bank of Japan (accession numbers DRA006359 and DRA007251).

Results

Hematopoietic cell-specific deletion of Bcor in mice

Most BCOR mutations cause frameshifts. Although it needs to be experimentally confirmed, the majority of BCOR mutations are thought to result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and/or generation of a C-terminal truncation including the PCGF1-binding domain.6,8 Grossman et al performed western blot analysis of 5 AML samples with BCOR frameshift mutations (L245TfsX19, H674MfsX41, T733AfsX5, P1115TfsX41, and N1485LfsX5) and failed to detect the full-length BCOR protein in all AML samples. Of note, a truncated protein was detected in AML cells with N1485LfsX5 mutation, albeit at levels much lower than the full-length BCOR protein in AML cells with WT BCOR. Therefore, at least in the 5 patients investigated, BCOR mutations were associated with the absence of full-length BCOR and lack or low expression of a truncated BCOR protein.6 The BcorΔE4 allele generates an internal deletion mutant that retains in frame coding for the C-terminal PCGF1-binding domain (supplemental Figure 1A; available on the Blood Web site).18 In contrast, the BcorΔE9-10 allele generates a frameshift mutant that fails to code for the C-terminal 474 amino acids and mimics many of the pathogenic mutations observed in patients with MDS and AML (supplemental Figure 1A).6 In order to understand the pathologic impact of BCOR mutants in hematological malignancies, we crossed mice harboring a Bcorfl mutation in which exon 4 or exons 9 and 10 were floxed (BcorflE4 and BcorflE9-10 mice, respectively) with Rosa26::Cre-ERT (Cre-ERT) mice. We transplanted total BM cells from Cre-ERT control (WT), Cre-ERT;BcorflE4/y, and Cre-ERT;BcorflE9-10/y CD45.2 male mice (Bcor is located on the X chromosome) without CD45.1 competitor cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice and deleted Bcor exon 4 and exons 9 and 10, respectively, by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen 4 weeks after transplantation (supplemental Figure 1B). We hereafter refer to recipient mice reconstituted with WT, BcorΔE4/y, and BcorΔE9-10/y cells as WT, ΔE4, and ΔE9-10 mice, respectively. We confirmed the efficient deletion of Bcor exons 9 and 10 in hematopoietic cells from ΔE9-10 mice by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using DNA isolated from CD45.2+Mac+/Gr1+ peripheral blood (PB) myeloid cells (supplemental Figure 1C). An RNA sequence analysis of lineage-marker (Lin)−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) revealed the specific deletion of Bcor exons 9 and 10 (supplemental Figure 1D). In addition, mRNA levels of Bcor without exons 9 and 10 were significantly reduced (supplemental Figure 1E), as is the case with BCOR mutants in MDS patients.6,8 Western blot analysis detected truncated BCORΔE9-10 protein expressed at a lower level than WT BCOR (full-length and several degraded BCOR) in thymocytes (supplemental Figure 1F). However, BCORΔE9-10 protein failed to coimmunoprecipitate with RING1B and USP7, suggesting that BCORΔE9-10 lacking the C-terminal PCGF1-binding domain is not incorporated into the PRC1.1 complex. A western blot analysis also revealed that global levels of polycomb histone modifications (H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3) did not change in ΔE9-10 BM c-Kit+ progenitors (supplemental Figure 1G).

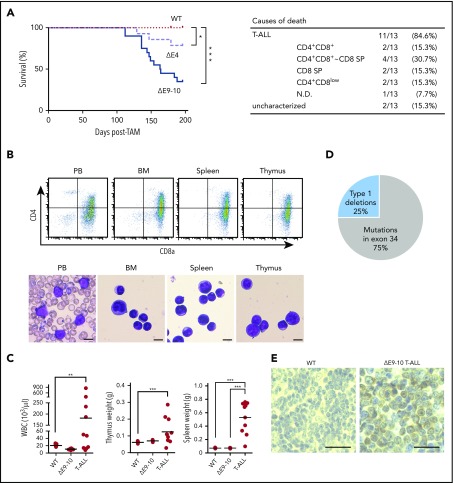

Deletion of Bcor exons 9 and 10 induces acute T-ALL

In order to examine the pathophysiological impact of the deletion of Bcor exons 9 and 10, we first analyzed hematopoiesis in WT, ΔE4, and ΔE9-10 mice. During the observation period of 7 months after the tamoxifen treatment, 65% of ΔE9-10 mice developed lethal T-ALL in a similar manner to ΔE4 mice.18 However, the onset of T-ALL was significantly earlier in ΔE9-10 mice than in ΔE4 mice (Figure 1A). Moribund mice with T-ALL showed the expansion of lymphoblasts, which were mostly CD4+CD8+ double-positive and/or CD8 single-positive, in PB, BM, the thymus, and spleen to varying degrees (Figure 1A-C). Although 40% of ΔE9-10 T-ALL mice had an enlarged thymus, 60% had almost no or the minimal involvement of the thymus, suggesting the BM origin of the disease (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Deletion of Bcor exons 9 and 10 induces acute T-ALL. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT (n = 15), ΔE4 (n = 14), and ΔE9-10 (n = 20) mice after the injection of tamoxifen; data from 2 independent experiments were combined. ***P < .001; *P < .05 by the log-rank test. The causes of death in ΔE9-10 mice are summarized in a table. (B) Flow cytometric profiles of PB, BM, the spleen, and thymus from a representative ΔE9-10 T-ALL mouse. Smear preparation of PB and cytospin preparations of BM, the spleen, and thymus after May-Giemsa staining are depicted below the profiles. Bars represent 10 μm. (C) PB white blood cell (WBC) counts and spleen and thymus weights in moribund ΔE9-10 T-ALL mice and WT and ΔE9-10 mice 12 weeks after the injection of tamoxifen (WBC: WT, n = 15; ΔE9-10, n = 20; ΔE9-10 T-ALL, n = 10; thymus: WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔE9-10 T-ALL, n = 10; spleen: WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔE9-10 T-ALL, n = 10). Bars in scatter diagrams indicate median values. ***P < .001 by the Student t test. (D) A pie graph summarizing the Notch1 status in ΔE9-10 T-ALLs. Genomic data of type 1 deletions and somatic mutations of Notch1 are depicted (n = 8). (E) Nuclear accumulation of cleaved NOTCH1 in the spleen of ΔE9-10 T-ALLs. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded spleens were stained using an anti-NOTCH1 antibody recognizing the cytosolic domain of NOTCH1. Sections were visualized and counterstained with hematoxylin. Bars represent 50 μm.

We then investigated whether the pathogenesis of T-ALL in ΔE9-10 mice is the same as that in ΔE4 mice. In >65% of human T-ALL patients, oncogenic NOTCH signaling is activated by gain-of-function mutations in the NOTCH1 gene, resulting in ligand-independent and sustained NOTCH1 signaling.22 However, in murine T-ALLs, Notch1 gene deletions, which remove exon 1 and the proximal promoter, are also common mechanisms of NOTCH1 activation.23 We found Notch1 deletions in 2 out of 8 mice, which removed exon 1 and the proximal promoter (type 1 deletions), leading to ligand-independent NOTCH1 activation.23 Four out of 8 mice had frameshift mutations in exon 34, which resulted in the truncation of the PEST domain in the C-terminal region of the protein. The remaining 2 mice had missense mutations in exon 34 with unknown consequences (Figure 1D). Immunohistochemical analyses of the spleen showed a general increase in NOTCH1 in ΔE9-10 T-ALL cells (Figure 1E). Collectively, these results suggest that most ΔE9-10 T-ALL are NOTCH-dependent, similar to ΔE4 T-ALL.18

ΔE9-10 HSPCs show a growth advantage in the myeloid compartment

After the deletion of Bcor, ΔE4 and ΔE9-10 mice both exhibited leukocytopenia, except for those that developed T-ALL (supplemental Figure 2A). Although all components of PB mononuclear cells decreased in ΔE4 and ΔE9-10 mice, leukocytopenia was mainly attributed to the reduction in B lymphocytes (supplemental Figure 2B). Only ΔE9-10 mice showed mild macrocytic anemia, an increase in platelet counts (supplemental Figure 2A), and mild morphological dysplasia of PB mononuclear cells (data not shown). A BM analysis 3 months after the deletion of Bcor revealed similar numbers of BM mononuclear cells between WT, ΔE4, and ΔE9-10 mice. Although the numbers of CD150+CD34−LSK hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and LSK HSPCs were decreased in ΔE4 and ΔE9-10 mice, those of myeloid progenitors were maintained (supplemental Figure 2C). Spleen and thymus weights did not markedly change between WT, ΔE4, and ΔE9-10 mice (supplemental Figure 2D).

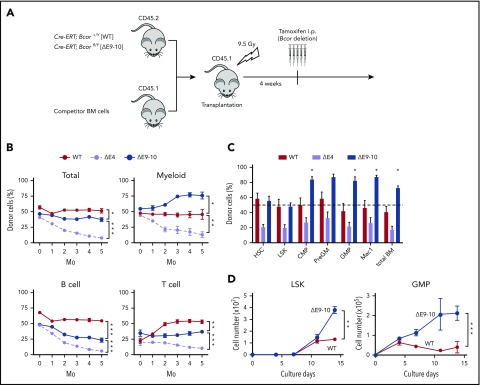

We then performed competitive repopulation assays (Figure 2A). BM cells from each genotype were transplanted with an equal number of CD45.1+ competitor cells. Although the chimerism of ΔE4 cells gradually declined because of compromised HSC function, as we reported previously,18 ΔE9-10 cells established similar chimerism to WT (Figure 2B). Of note, ΔE9-10 cells outcompeted WT competitor cells in the myeloid lineage, whereas they showed poor repopulation in the lymphoid lineage, particularly the B-cell lineage (Figure 2B). A BM analysis of the primary recipients also demonstrated the significantly higher chimerism of ΔE9-10 cells in the myeloid lineage from the common myeloid progenitor stage (Figure 2C). Based on the in vitro findings obtained from ΔE9-10 BM cells by Cao et al,20 we examined the growth of ΔE9-10 HSPCs in culture. As reported previously, ΔE9-10 LSK cells and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) showed better growth than WT cells under myeloid culture conditions (Figure 2D). These results indicate that ΔE9-10 HSPCs maintain a self-renewal capacity and have a growth advantage in the myeloid compartment.

Figure 2.

ΔE9-10 HSPCs show a growth advantage in the myeloid compartment. (A) Strategy for competitive repopulating assays using BM cells from ΔE9-10 mice. CD45.2 BM cells (2 × 106) from WT and ΔE9-10 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice along with the same number of CD45.1 WT BM cells. Bcor exon 4 and exons 9 and 10 were deleted by injecting tamoxifen at 4 weeks posttransplantation. (B) The chimerism of CD45.2 donor cells in PB after the tamoxifen injection (n = 5). (C) The chimerism of CD45.2 donor cells in BM (n = 5) 5 months after the tamoxifen injection (n = 5). (D) Growth of WT and ΔE9-10 LSK HSPCs and GMPs in culture. HSCs and HSPCs were cultured in triplicate under myeloid cell culture conditions (stem cell factor [SCF] + thrombopoietin (TPO) + interleukin-3 [IL-3] + granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]). Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 by the Student t test.

Concurrent deletion of Bcor and Tet2 induces lethal MDS

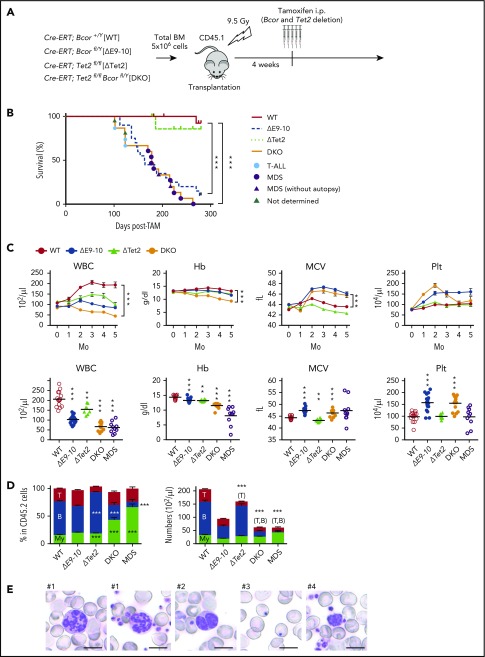

TET2 is an enzyme that functions in the demethylation pathway of methylated cytosine induced by DNA methyltransferase family methyltransferases. The recurrent loss-of-function mutations in TET2 are identified in myeloid malignancies24 and in clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential in the elderly.25 The loss of Tet2 has been reported to increase HSC self-renewal and induce chronic myelomonocytic leukemia–like hematological malignancies in mice.21 Of note, somatic mutations in BCOR are frequently associated with TET2 mutations in MDS.16 Among 41 MDS patients with a mutation in TET2, 6 patients (15%) had comutations in BCOR.16 In order to clarify the impact of ΔE9-10 on a Tet2-null background, we generated Cre-ERT;Tet2fl/flBcorflE9-10/y compound mice. We transplanted total BM cells from Cre-ERT control (WT), Cre-ERT;BcorflE9-10/y, Cre-ERT;Tet2fl/fl, and Cre-ERT;Tet2fl/flBcorflE9-10/y CD45.2 male mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice and deleted Bcor exons 9 and 10 and/or Tet2 by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen at 4 weeks posttransplantation (hereafter, WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and double knockout (DKO) mice, respectively) (Figure 3A). DKO mice exhibited more severe leukocytopenia, mainly because of the reduction in B-cell numbers, and macrocytic anemia than ΔE9-10 and ΔTet2 mice (Figure 3C-D). Although DKO mice demonstrated similar overall survival to that of ΔE9-10 mice that developed lethal T-ALL, they only developed T-ALL at the early phase postdeletion of Bcor (Figure 3B, blue circle). DKO mice developed lethal MDS after 5 months (Figure 3B, purple circle) supplemental Table 1) that was characterized by severe macrocytic anemia and leukocytopenia (Figure 3C-D), which may account for the death of MDS mice. PB smears of MDS mice revealed the morphological dysplasia of blood cells such as hypersegmented neutrophils, pseudo Pelger-Huët anomaly of neutrophils, Howell-Jolly bodies, and giant platelets (Figure 3E, #1-4, respectively), which were more prominent than in ΔE9-10 mice, but barely detected in ΔTet2 and WT mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Concurrent deletion of Bcor and Tet2 causes MDS-like BM failure. (A) Strategy for analyzing hematopoietic cells with conditional knockout alleles for Tet2 and Bcor exons 9 and 10. Total BM cells from Cre-ERT control (WT), Cre-ERT;BcorflE9-10/y, Cre-ERT;Tet2fl/fl, and Cre-ERT;Tet2fl/flBcorflE9-10/y CD45.2 male mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. After engraftment, Tet2 and Bcor exons 9 and 10 were deleted by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen at 4 weeks posttransplantation. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT (n = 15), ΔE9-10 (n = 20), ΔTet2 (n = 10), and DKO (n = 15) mice after the injection of tamoxifen; data from 2 independent experiments were combined. ***P < .001 by the log-rank test. The causes of death in DKO mice are indicated by circles or triangles with different colors. (C) PB cell counts in WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO mice. WBC, hemoglobin (Hb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and platelet (Plt) counts in PB from WT (n = 15), ΔE9-10 (n = 19), ΔTet2 (n = 8), and DKO (n = 14) mice up to 5 months after the injection of tamoxifen are shown (upper panels). Data of moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 10) are shown with those of WT (n = 15), ΔE9-10 (n = 19), ΔTet2 (n = 8), and DKO (n = 14) mice 3 months after the injection of tamoxifen in the lower panels. (D) The proportions of myeloid (My) (Mac-1+ and/or Gr-1+), B220+ B cells, and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells among CD45.2+ donor-derived hematopoietic cells and their absolute numbers in PB from WT (n = 15), ΔE9-10 (n = 19), ΔTet2 (n = 8), and DKO (n = 14) mice 3 months after the injection of tamoxifen and moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 10). (E) Smear preparation of PB from moribund DKO MDS mice 6 months after the deletion of Bcor after May-Giemsa staining. Hypersegmented neutrophils (#1), hyposegmented neutrophils consistent with a pseudo Pelger-Huët anomaly (#2), Howell-Jolly bodies (#3), and giant platelets (#4) are shown. Bars represent 10 μm. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM in panels C and D. Statistical significance is shown relative to WT. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 by the Student t test.

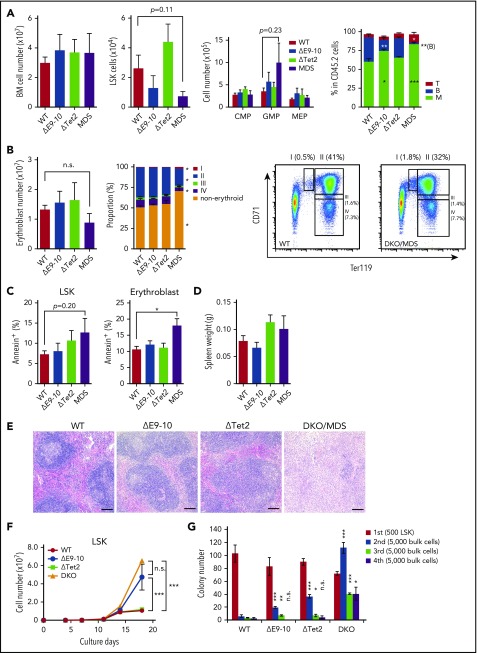

A BM analysis of moribund MDS mice and their controls (WT, ΔE9-10, and ΔTet2) in the same cohort revealed no significant changes in BM cell counts in MDS mice. Although the numbers of LSK HSPCs were decreased in ΔE9-10 and MDS mice, GMP numbers increased in MDS mice (Figure 4A). In addition, MDS mice showed a mild block in erythroid differentiation at the transition from CD71+Ter119mid proerythroblasts (Figure 4B, region I) to CD71+Ter119+ basophilic erythroblasts (Figure 4B, region II). The proportions of annexin V+ cells were significantly higher in DKO CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts than in WT mice (Figure 4C). DKO LSK cells also showed a tendency for enhanced apoptosis, albeit not statistically significant (Figure 4C). These results indicate enhanced inefficient hematopoiesis in DKO MDS BM, a feature compatible with myelodysplastic disorders. Spleen weights were not significantly changed in DKO mice (Figure 4D). However, lymphoid follicles were severely destroyed by infiltrated myeloid cells in DKO spleens (Figure 4E). Regardless of the MDS-like phenotype of DKO mice, DKO LSK cells showed better growth (Figure 4F) and replating capacity (Figure 4G) than ΔE9-10 and ΔTet2 cells in cultures under myeloid culture conditions.

Figure 4.

Concurrent deletion of Bcor and Tet2 induces inefficient hematopoiesis. (A) Absolute numbers of total BM cells, CD150+CD34−LSK HSCs, LSK HSPCs, and myeloid progenitors in a unilateral pair of the femur and tibia from moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 6) and their controls in the same cohort (WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔTet2, n = 5). Proportions of myeloid, B and T cells in BM are shown in the right panel. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 by the Student t test. (B) Absolute numbers of BM erythroblasts in a unilateral pair of the femur and tibia from moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 5) and their controls in the same cohort (WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔTet2, n = 5). Proportions of the differentiation stages of erythroblasts and a representative flow cytometric profile of WT and DKO MDS erythroblasts are shown in the middle and right panels. *P < .05 relative to WT by 1-way analysis of variance, Tukey’s post hoc test. (C) Percentage of annexin V+ cells in LSK cells and CD71+Ter119+ BM erythroblasts in moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 5) and their controls (WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔTet2, n = 5). *P < .05 by the Student t test. (D) Spleen weights of moribund DKO MDS mice (n = 6) and their controls (WT, n = 5; ΔE9-10, n = 5; ΔTet2, n = 5). (E) Histology of the spleen from WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO MDS mice observed by hematoxylin-eosin staining. Bars represent 100 μm. (F) Growth of WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO LSK HSPCs in culture. LSK cells purified from mice 1 month after the tamoxifen injection were cultured in triplicate under myeloid cell culture conditions (SCF + TPO + IL-3 + GM-CSF). ***P < .001; n.s., not significant, by the Student t test. (G) Replating assay data. Five hundred LSK cells were plated in methylcellulose medium containing 20 ng/mL of SCF, TPO, IL-3, and GM-CSF. After 12 days of culture, colonies were counted and pooled, and 5 × 103 cells were then replated in the same medium every 7 days. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is shown relative to WT. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s., not significant, by the Student t test.

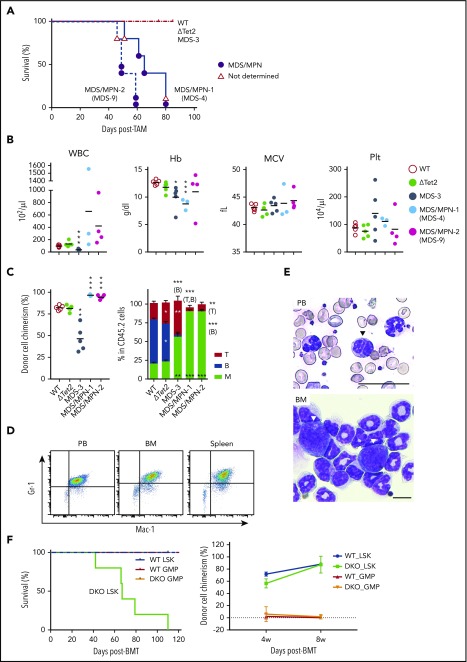

ΔTet2ΔE9-10 MDS cells evolve into MDS/MPN during serial transplantation

In order to clarify whether DKO MDS cells were transplantable, we transplanted BM cells from 3 moribund DKO MDS mice into sublethally irradiated recipient mice. During the observation period of 3 months, BM cells from MDS-3 mice (supplemental Table 1) reproduced MDS-like disease in recipient mice that was characterized by leukocytopenia and macrocytic anemia (Figure 5B-C), and the morphological dysplasia of PB cells (data not shown), although the chimerism of MDS-3-derived cells was significantly low (Figure 5C). In contrast, BM cells from MDS-4 mice (supplemental Table 1) induced lethal MDS/MPN with the massive expansion of myeloid cells, mostly Gr-1+Mac-1+ neutrophilic cells, in PB, BM, and the spleen (Figure 5A-E). PB smears of MDS/MPN mice revealed morphological dysplasia of myeloid cells such as hypersegmented neutrophils and pseudo Pelger-Huët anomaly of neutrophils (Figure 5E). Blast-like cells were observed in BM, albeit at a low frequency (Figure 5E). BM cells from MDS-9 mice (supplemental Table 1) also induced lethal MDS/MPN (Figure 5A-C). These results clearly indicate that Bcor insufficiency promotes not only the initiation of MDS, but also its progression to more aggressive myeloid malignancies.

Figure 5.

ΔTet2ΔE9-10 MDS cells evolve into MDS/MPN during serial transplantation. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of recipient mice infused with BM cells from MDS-3, MDS-4, and MDS-9 mice and their WT and ΔTet2 control mice (n = 5 each). The causes of death in DKO mice are indicated by circles or triangles with different colors. (B) PB cell counts in recipient mice 3 months after transplantation (n = 3-5 each). (C) The chimerism of CD45.2 donor cells in PB 3 months after transplantation (n = 3-5 each). The proportions of myeloid (My) (Mac-1+ and/or Gr-1+), B220+ B cells, and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells among CD45.2+ donor-derived hematopoietic cells in PB are depicted in the right panels (n = 3-5 each). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is shown relative to WT. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 by the Student t test. (D) MDS/MPN developed in recipients infused with BM from MDS-4 mice. Flow cytometric profiles of MDS/MPN cells in PB, BM, and the spleen. (E) Smear preparation of PB and cytospin preparation from moribund MDS/MPN (MDS-4) mice after May-Giemsa staining. Hyposegmented neutrophils consistent with a pseudo Pelger-Huët anomaly (arrowhead) in PB and scattered blasts (arrowheads) in BM are shown. Bars represent 50 and 10 μm, respectively. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of recipient mice infused with LSK cells (1.2 × 104/mouse, n = 5 each) or GMPs (WT, 1 × 105 to 2 × 105 GMPs per mouse, n = 4; DKO, 2 × 105 GMPs per mouse, n = 5) from WT and DKO MDS mice (CD45.2+). Purified LSK cells and GMPs were transplanted into recipient mice sublethally irradiated at a dose of 6.5 Gy. The chimerism of CD45.2 donor cells in PB after transplantation is indicated in the right panel. MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

In order to determine the fractions that contain disease-initiating cells, we purified LSK cells and GMPs from WT and DKO MDS mice and transplanted them into sublethally irradiated (6.5 Gy) recipient mice. As expected, LSK cells established high levels of engraftment and developed lethal MDS/MPN as MDS-4 and MDS-9 BM cells did, whereas GMPs hardly repopulated in recipient mice (Figure 5F). These results indicate that the MDS-initiating cells exist in the HSPC fraction.

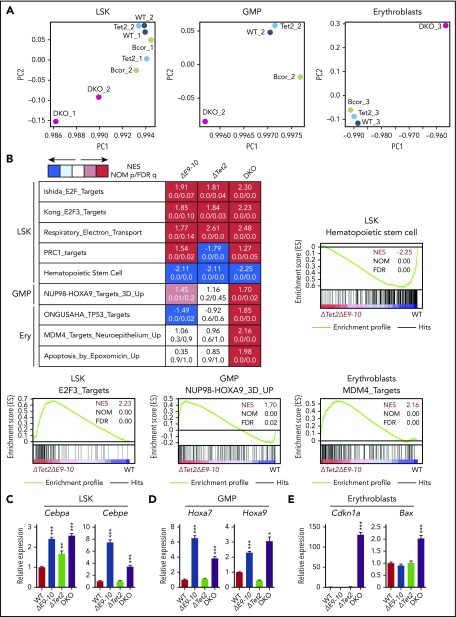

Bcor insufficiency causes the activation of myeloid-related genes

In order to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying a pathogenic role for Bcor insufficiency in the initiation and progression of MDS, we performed RNA sequence analysis using LSK HSPCs, GMPs, and CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts from DKO MDS mice and their WT, ΔE9-10, and ΔTet2 counterparts in the same cohort. Principal component analyses revealed that DKO MDS cells had distinct transcriptional profiles from those of WT, ΔE9-10, and ΔTet2 cells (Figure 6A). Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) showed the positive enrichment of gene sets of E2F targets and respiratory electron transport in ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO MDS LSK cells, with the highest enrichment in DKO MDS cells. In contrast, HSC genes were negatively enriched in LSK cells and mostly downregulated in DKO MDS cells (Figure 6B). NUP98-HOXA9 target genes were moderately enriched in ΔE9-10 GMPs and strongly enriched in DKO MDS GMPs, but not in ΔTet2 GMPs (Figure 6B). In erythroblasts, p53 and MDM4 pathway genes and apoptosis-related genes were specifically enriched in DKO MDS cells, but not in ΔE9-10 or ΔTet2 cells (Figure 6B). The enrichment of PRC1 target genes, defined by the presence of the H2AK119ub1 mark in LSK cells, was significantly greater in ΔE9-10 and DKO LSK cells than in WT cells.

Figure 6.

Bcor insufficiency causes the activation of myeloid-related genes. (A) Principal component (PC) analyses based on total gene expression in LSK HSPCs, GMPs, and CD71+Ter119+erythroblasts isolated from WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO MDS mice. (B) GSEA performed using RNA sequence data. Summary of GSEA data and GSEA plots of representative data are shown. Normalized enrichment scores (NES), nominal P values (NOM), and false discovery rates (FDR) are indicated. The gene sets used are indicated in supplemental Table 2. Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR analysis of Cebpa and Cebpe in LSK cells (C), Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 in GMPs (D), and Cdkn1a and Bax in CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts (E). Hprt1 was used to normalize the amount of input RNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance is shown relative to WT. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 by the Student t test.

Cao et al20 previously demonstrated the upregulation of Cebp family transcription factor genes and Hoxa cluster genes in ΔE9-10 BM cells cultured for 7 days under myeloid stem/progenitor conditions. They also showed that the expression of HOXA9 was significantly upregulated in MDS patients with BCOR loss-of-function mutations.20 We subsequently validated the expression of these genes using a quantitative reverse transcription–PCR analysis. We confirmed that Cebpa and Cebpe genes were specifically upregulated in LSK cells (Figure 6C), but not in GMPs (data not shown) in ΔE9-10 and DKO MDS cells. Conversely, Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 were upregulated in GMPs (Figure 6D), but not in LSK cells (data not shown) in ΔE9-10 and DKO MDS cells. We also confirmed the significant activation of representative direct targets of p53 related to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, such as Cdkn1a and Bax, in DKO MDS erythroblasts (Figure 6E). These results correlated well with the growth advantage of ΔE9-10 and DKO hematopoietic progenitors and the enhanced apoptosis of DKO MDS erythroblasts. We then evaluated the contribution of derepressed Hoxa and Cebp family genes to the growth advantage of DKO hematopoietic progenitors. We infected LSK cells from DKO mice with lentiviruses expressing short hairpin RNAs against Hoxa7, Hoxa9, or Cebpa and cultured them under the same culture conditions as in Figure 4F. Unexpectedly, single knockdown of Hoxa7, Hoxa9, or Cebpa failed to attenuate the growth advantage of DKO cells (supplemental Figure 3). Given that multiple genes of Cepb and Hoxa families are derepressed in DKO mice, it is possible that combined knockdown of multiple family genes is essential to precisely evaluate their effects on myeloid cell growth.

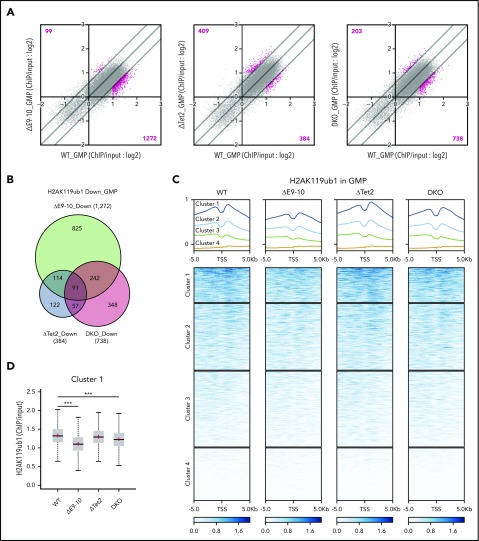

Bcor insufficiency causes reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels at myeloid-related genes

To understand how BCOR loss deregulated H2AK119ub1 modifications, we performed ChIP-seq analysis of H2AK119ub1 using GMPs from WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO mice 4 weeks after the deletion of Bcor and/or Tet2. We defined “PRC1 targets” as genes with H2AK119ub1 enrichment greater than twofold over the input signals. The loss of BCOR in ΔE9-10 and DKO GMPs induced reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels (≥1.5-fold) at a larger number of promoter regions (transcription start site [TSS] ± 2.0 kb) of PRC1 targets than the loss of TET2 in ΔTet2 GMPs (Figure 7A). There was a notable overlap of genes that lost H2AK119ub1 modifications (≥1.5-fold) at promoters in ΔE9-10 and DKO GMPs (Figure 7B). Importantly, a heat map revealed clear reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels at the promoters of genes associated with high levels of H2AK119ub1 modifications (cluster 1 genes) in ΔE9-10 and DKO GMPs (Figure 7C-D). The Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 loci, which were derepressed in ΔE9-10 and DKO GMPs, showed moderate reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels in ΔE9-10 and DKO GMPs (Figure 7E). ChIP quantitative PCR confirmed that the changes were significant at the Hoxa9 locus (Figure 7F). We also confirmed that the H2AK119ub1 levels at the Cebpa promoter were moderately reduced in ΔE9-10 LSK cells, whereas they were significantly decreased in DKO LSK cells (Figure 7F). Unexpectedly, combined loss of BCOR and TET2 did not enhance the reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels, suggesting that reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels was mainly induced by the loss of BCOR.

Figure 7.

Bcor insufficiency causes reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels. (A) Scatter plots showing the correlation of the fold enrichment values of H2AK119ub1 against the input signals (ChIP/input) (TSS ± 2.0 kb of RefSeq genes) in GMPs from ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO mice 4 weeks after the tamoxifen treatment relative to WT GMPs. The light diagonal lines represent the boundaries for 1.5-fold increase or decrease in fold enrichment of H2AK119ub1. We defined “PRC1 targets” as genes with H2AK119ub1 enrichment greater than twofold over the input signals. Among PRC1 targets, the genes that gained or lost H2AK119ub1 modifications >1.5-fold compared with those in WT are indicated in pink. (B) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of PRC1 target genes that lost H2AK119ub1 modifications >1.5-fold in ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO GMPs compared with those in WT GMPs in (A). (C) Heat map showing the levels of H2AK119ub1 at the range of TSS ± 5.0 kb. The levels of H2AK119ub1 in each cluster are plotted in upper columns. (D) Box-and-whisker plots showing H2AK119ub1 levels of genes in cluster 1 in WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO GMPs. Boxes represent 25 to 75 percentile ranges. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data point which is no more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box. Horizontal bars represent medians. Mean values are indicated by “+” in red. ***P < .001 by the Student t test. (E) Snapshots of RNA sequencing and H2AK119ub1 ChIP-seq signals at the Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 gene loci in WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO GMPs. The structure of the Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 genes are indicated at the bottom. (F) Manual ChIP quantitative PCR assays for H2AK119ub1 in GMPs and LSK cells at the Hoxa9 and Cebpa loci, respectively. The relative amounts of immunoprecipitated DNA are depicted as a percentage of input DNA. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01 by the Student t test.

In order to evaluate the impact of the combined loss of BCOR and TET2 on DNA methylation, we performed reduced representation bisulfite sequencing of GMPs isolated from WT, ΔE9-10, ΔTet2, and DKO mice 4 weeks after the deletion of Bcor and/or Tet2. We defined differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) and regions (DMRs) as those showing significant differences in methylation levels (≥10%, q value <0.05) from those in WT cells (supplemental Table 3). ΔTet2 GMPs acquired more hyper-DMCs and hyper-DMRs than ΔE9-10 GMPs did (supplemental Figure 4A-B), but the proportions of hyper-DMCs and hyper-DMRs were comparable between ΔTet2 and DKO GMPs. These results indicate that TET2 loss had a major impact on promoting DNA methylation. Nevertheless, a large portion of hyper-DMRs in DKO GMPs were distinct from those in each single mutant (supplemental Figure 4C), implying that the combined loss of BCOR and TET2 synergistically promoted DNA hypermethylation and had a unique impact on the epigenome. Indeed, the expression of genes with hyper-DMRs, the majority of which were found at the promoter region (supplemental Figure 4D), was significantly downregulated in DKO GMPs, but not in ΔE9-10 and ΔTet2 GMPs (supplemental Figure 4E). A considerable portion of genes with hyper-DMRs at promoters in DKO GMPs (12.2%) overlapped with those with hyper-DMRs at promoter CpG islands in human CD34+ cells from MDS patients26 (supplemental Figure 4F). These results suggest that DNA hypermethylation also compromised hematopoiesis by antagonizing the function of key regulatory genes.

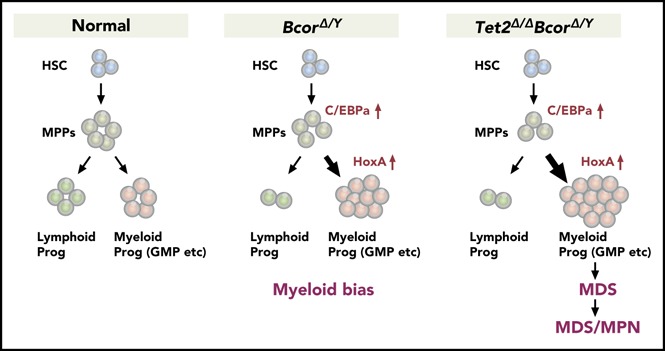

Discussion

In the present study, we confirmed that Bcor insufficiency from the BcorΔE9-10/y allele, like the BcorΔE4/y allele, induced T-ALL in mice. These results indicate that not only the region encoded by exon 4, which includes the BCL6-binding domain, but also the C-terminal region, which includes the PCGF1-binding domain, are essential for the tumor suppressor function of BCOR in T lymphocyte malignancies. Furthermore, BcorΔE9-10/y mice were more severely affected than BcorΔE4/y mice, both in terms of normal hematopoiesis and the rapidity of T-ALL onset, suggesting that BcorΔE9-10/y is null and BcorΔE4/y hypomorphic. In our previous study, we confirmed that BcorΔE4 lacked binding to BCL6 but was expressed at high levels and retained binding to PRC1.1.18 In contrast, BCORΔE9-10 could not bind to PRC1.1 and was expressed at low levels, suggesting that corepressor function of BCOR for BCL6 was also attenuated. These functional differences may have caused the phenotypic differences between ΔE4 and ΔE9-10 mice. Many of the pathogenic BCOR mutations observed in patients with hematological malignancies are analogous to the BcorΔE9-10 allele in that they encode a premature stop codon, which removes the coding potential for the critical C-terminal region. Thus, we speculated that BcorΔE9-10/y mice may also develop other types of hematological malignancies when combined with other oncogenic mutations. Indeed, when BcorΔE9-10 was combined with a Tet2 loss-of-function allele, we revealed a tumor suppressor function of BCOR in myeloid malignancies.

The concurrent deletion of Tet2, one of the partner genes frequently comutated with BCOR in MDS patients,16 induced lethal MDS in mice after a longer latency than T-ALL. Although MDS clones have a growth advantage and continue to expand in BM, MDS patients show ineffective hematopoiesis characterized by impaired differentiation and the enhanced apoptosis of BM cells, leading to cytopenia.27 The loss of TET2 itself promotes myeloid-biased hematopoiesis.21 Correspondingly, the concurrent deletion of Tet2 enhanced myeloid-biased differentiation and the growth advantage of Bcor insufficient hematopoietic cells. The expression levels of Cebp family genes in LSK HSPCs and Hoxa7 and Hoxa9 in GMPs were similar between BcorΔE9-10/y and DKO mice, suggesting that these genes are specific targets of BCOR. In contrast, p53 target genes were activated specifically in erythroblasts in MDS mice, but not in Tet2Δ/Δ or BcorΔE9-10/y mice, suggesting that the combination of the loss of TET2 and BCOR not only augments the growth advantage of MDS stem and progenitor cells, but also induces ineffective hematopoiesis to establish an MDS state. These results correlated well with the somatic mutation profiles of MDS patients.16 Mechanistically, our findings so far indicate that dysregulated H2AK119ub1 modifications were mainly induced by the loss of BCOR, while aberrant DNA methylation was mainly induced by the loss of TET2. Nevertheless, a large portion of hyper-DMRs in DKO GMPs was distinct from those in each single mutant, implying that the combined loss of BCOR and TET2 synergistically promoted aberrant DNA hypermethylation. Although the precise mechanism underlying collaboration between loss of BCOR and TET2 on epigenome needs further analysis, our data implicate dysregulation of 2 different epigenetic pathways in the pathogenesis of MDS induced by concurrent loss of BCOR and TET2. A previous study reported that patients with truncating BCOR mutations showed inferior overall survival and a higher cumulative incidence of AML transformation.8 In AML, BCOR mutations are highly specific to secondary AML, which develops following antecedent MDS, but are rare in de novo AML. Because BCOR mutations are also frequent in MDS, BCOR mutations may primarily drive dysplastic differentiation and ineffective hematopoiesis observed in MDS without efficiently promoting the development of frank leukemia. Newly acquired mutations in genes encoding myeloid transcription factors or members of the RAS/tyrosine kinase signaling pathway have instead been suggested to promote the progression of MDS to AML.7 In the present study, some DKO MDS cells progressed to lethal MDS/MPN during serial transplantation. These results indicate that DKO MDS clones progress to a preleukemic state possibly with additional gene mutations. Thus, our model may recapture a part of chronological disease progression from low-risk MDS to high-risk MDS and eventually to AML.

Based on our studies using 2 different Bcor mutant mice, BCOR truncating mutants missing the PRC1 interacting region appear to have broader impacts on the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies than the internal deletion mutant lacking the BCL6-binding domain. These results highlight the pathogenic role for the dysregulated function of PRC1.1. GSEA revealed the derepression of PRC1 target genes in ΔE9-10 LSK cells, and ChIP-seq of ΔE9-10 GMPs revealed reduction in H2AK119ub1 levels at promoters. PRC2 dysfunction is known to be induced by multiple mechanisms in MDS: somatic mutations of PRC2 component genes such as EZH2, the loss of EZH2 located at chromosome 7q36.1 by −7/7q- chromosomal abnormalities, and the missplicing of EZH2 by mutations in spliceosomal genes such as SRSF2 and U2AF1.28 We also demonstrated that the concurrent depletion of Tet2 and Ezh2 induced MDS in mice.29 Collectively, these findings suggest that not only PRC2, but also PRC1.1 has a tumor suppressor function in myeloid malignancies and that PRC2 and PRC1.1 may regulate common target genes, the dysregulation of which contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS. In addition, ASXL1 mutants, frequently identified in patients with MDS, have recently been demonstrated to enhance the deubiquitination activity of BAP1 on H2AK119.30 ASXL1 mutants also induce the transcriptional activation of Hoxa cluster genes31 as the Bcor mutant in the present study did. In this regard, the precise regulation of H2AK119 monoubiquitination by BCOR/PRC1.1 and BAP1/ASXL1 may involve functional cross talk and be the key to preventing the transformation of HSPCs.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Noriko Yamanaka and Yuko Yamagata for their technical assistance, and Ola Mohammed Kamel Rizq for critically reviewing the manuscript. The supercomputing resource was provided by the Human Genome Center, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo.

This work was supported, in part, by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#15H02544) and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Stem Cell Aging and Disease” (#26115002) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and grants from the Yasuda Memorial Medical Foundation and Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (accession numbers DRA006359 and DRA007251).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.T. and A.I. designed this study; S.T. performed experiments, analyzed data, and actively wrote the manuscript; Y.I., Y.N.-T., M.O., K.A., T.T., D.S., S.K., A.S., S.M., I.M., and H.M. performed experiments and analyzed data; H.K. and V.J.B provided mice and antibodies; and A.I. conceived of and directed the project, secured funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Atsushi Iwama, Division of Stem Cell and Molecular Medicine, Center for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan; e-mail: 03aiwama@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huynh KD, Fischle W, Verdin E, Bardwell VJ. BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14(14):1810-1823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein U, Dalla-Favera R. Germinal centres: role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):22-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gearhart MD, Corcoran CM, Wamstad JA, Bardwell VJ. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(18):6880-6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez C, Sánchez I, Demmers JA, Rodriguez P, Strouboulis J, Vidal M. Proteomics analysis of Ring1B/Rnf2 interactors identifies a novel complex with the Fbxl10/Jhdm1B histone demethylase and the Bcl6 interacting corepressor. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(5):820-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Z, Zhang J, Bonasio R, et al. . PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes. Mol Cell. 2012;45(3):344-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossmann V, Tiacci E, Holmes AB, et al. . Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of BCOR in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. 2011;118(23):6153-6163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, et al. . Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood. 2015;125(9):1367-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damm F, Chesnais V, Nagata Y, et al. . BCOR and BCORL1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and related disorders. Blood. 2013;122(18):3169-3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Park HY, Kang SY, et al. . Genetic alterations of JAK/STAT cascade and histone modification in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal type. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):17764-17776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobashi A, Tsuyama N, Asaka R, et al. . Frequent BCOR aberrations in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(5):460-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landau DA, Tausch E, Taylor-Weiner AN, et al. . Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 2015;526(7574):525-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiel MJ, Velusamy T, Rolland D, et al. . Integrated genomic sequencing reveals mutational landscape of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(9):1460-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stengel A, Kern W, Zenger M, et al. . Genetic characterization of T-PLL reveals two major biologic subgroups and JAK3 mutations as prognostic marker. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(1):82-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Collins R, Jiao Y, et al. . Somatic mutations in the transcriptional corepressor gene BCORL1 in adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(22):5914-5917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. . Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, Ambaglio I, et al. . Driver somatic mutations identify distinct disease entities within myeloid neoplasms with myelodysplasia. Blood. 2014;124(9):1513-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebure M, Tothill RW, Kruse E, et al. . Genomic characterisation of Eμ-Myc mouse lymphomas identifies Bcor as a Myc co-operative tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka T, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Aoyama K, et al. . Internal deletion of BCOR reveals a tumor suppressor function for BCOR in T lymphocyte malignancies. J Exp Med. 2017;214(10):2901-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seki M, Kimura S, Isobe T, et al. . Recurrent SPI1 (PU.1) fusions in high-risk pediatric T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2017;49(8):1274-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Q, Gearhart MD, Gery S, et al. . BCOR regulates myeloid cell proliferation and differentiation. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1155-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, et al. . Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belver L, Ferrando A. The genetics and mechanisms of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(8):494-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashworth TD, Pear WS, Chiang MY, et al. . Deletion-based mechanisms of Notch1 activation in T-ALL: key roles for RAG recombinase and a conserved internal translational start site in Notch1. Blood. 2010;116(25):5455-5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastore F, Levine RL. Epigenetic regulators and their impact on therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101(3):269-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, et al. . Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126(1):9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maegawa S, Gough SM, Watanabe-Okochi N, et al. . Age-related epigenetic drift in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. Genome Res. 2014;24(4):580-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raza A, Galili N. The genetic basis of phenotypic heterogeneity in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(12):849-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwama A. Polycomb repressive complexes in hematological malignancies. Blood. 2017;130(1):23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muto T, Sashida G, Oshima M, et al. . Concurrent loss of Ezh2 and Tet2 cooperates in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic disorders. J Exp Med. 2013;210(12):2627-2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balasubramani A, Larjo A, Bassein JA, et al. . Cancer-associated ASXL1 mutations may act as gain-of-function mutations of the ASXL1-BAP1 complex. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue D, Kitaura J, Togami K, et al. . Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation–altering ASXL1 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4627-4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.