Significance

The family of copper-dependent lysyl oxidase (LOX) enzymes contributes to tumor metastasis. In this study, we show that the ATP7A copper transporter is required to deliver copper to LOX family members. Deletion of ATP7A inhibited LOX activity in breast and lung cancer cell lines, resulting in a significant loss of tumor growth and metastatic potential of these cells in mice. Elevated expression of ATP7A was found to be associated with reduced survival of breast cancer patients. Our study suggests that blocking the function of ATP7A could be an approach to inhibiting LOX-dependent malignancies.

Keywords: breast cancer, lung cancer, copper, lysyl oxidase, metastasis

Abstract

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) and LOX-like (LOXL) proteins are copper-dependent metalloenzymes with well-documented roles in tumor metastasis and fibrotic diseases. The mechanism by which copper is delivered to these enzymes is poorly understood. In this study, we demonstrate that the copper transporter ATP7A is necessary for the activity of LOX and LOXL enzymes. Silencing of ATP7A inhibited LOX activity in the 4T1 mammary carcinoma cell line, resulting in a loss of LOX-dependent mechanisms of metastasis, including the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and myeloid cell recruitment to the lungs, in an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer. ATP7A silencing was also found to attenuate LOX activity and metastasis of Lewis lung carcinoma cells in mice. Meta-analysis of breast cancer patients found that high ATP7A expression was significantly correlated with reduced survival. Taken together, these results identify ATP7A as a therapeutic target for blocking LOX- and LOXL-dependent malignancies.

Copper is an essential micronutrient required as a catalytic cofactor for several metalloenzymes, including those involved in cancer-promoting activities (1). Copper-dependent enzymes with roles in tumor growth or metastasis include mitogen-activated kinase 1 (2, 3), superoxide dismutase 1 (4), cytochrome c oxidase (5), and members of lysyl oxidase (LOX) family (6–8). The discovery that copper concentrations in serum and tumors are elevated in cancer patients and are correlated with disease severity has prompted speculation that copper delivery to oncogenic enzymes may be rate-limiting for tumor growth and metastasis (9–11). This idea has been supported by reports that copper chelation reduces tumor growth and malignancy in animal models of cancer (12, 13). Clinical studies indicate that copper chelation prolongs the survival of patients with late-stage breast cancer (14) and kidney cancer (15). These studies raise the possibility that blocking specific steps in the delivery of copper to oncogenic metalloenzymes may provide an approach to treating cancer.

LOX is a secreted copper-dependent amine oxidase that plays critical roles in the development of connective tissue and remodeling of the extracellular matrix by catalyzing the cross-linking of collagen and elastin (16). In addition to LOX, several LOX-like enzymes (LOXL1–4) have been identified that share a conserved catalytic copper-binding domain. To date, functional roles for LOX or LOXL enzymes have been documented in breast, colorectal, prostate, gastric, hepatic, pancreatic, and head and neck cancers, as well as in cancers of the skin, including melanoma (6, 17–19). LOX has been shown to promote tumor cell migration and adhesion via the activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK1) (20–22). In addition, LOX and LOXL2 activity is required to facilitate the recruitment of myeloid cells to metastatic sites, creating a favorable environment for the subsequent invasion and growth of tumor cells (18, 19, 23).

The importance of LOX and LOXL proteins in cancer has led to intensive efforts to develop inhibitors of these enzymes as potential anticancer therapies. Since all LOX family members share a functional requirement for copper, we surmised that inhibiting copper incorporation into these enzymes may be an effective strategy to inhibit LOX-dependent metastasis. However, the mechanism of copper incorporation into LOX and LOXL proteins is poorly understood. The copper-binding catalytic domain of each LOX family member is lumenally oriented (extracytoplasmic), suggesting that copper insertion occurs via a conserved mechanism during the biosynthesis of these enzymes en route through the secretory pathway. Previous studies have shown that the Golgi-localized copper transporter ATP7A delivers copper to tyrosinase, a metalloenzyme with an extracytoplasmic copper-binding catalytic domain (24). In addition, LOX activity is reduced in Menkes disease fibroblasts, which contain mutations in the ATP7A gene (25). However, the extent to which ATP7A is required for the activity of different members of the LOX family of enzymes and, by extension, the importance of ATP7A in LOX-mediated pathologies remain unknown.

Here we demonstrate that ATP7A is required for the activity of multiple members of the LOX family, and that silencing ATP7A in two different cancer cell lines suppresses tumorigenesis and metastasis in mice. Importantly, elevated ATP7A expression was found to be significantly correlated with reduced survival in breast cancer patients, suggesting a role for ATP7A in human cancer. These studies identify ATP7A as a target for inhibiting LOX-dependent malignancies.

Results

ATP7A Is Necessary and Sufficient for Copper-Dependent Activity of LOX Family Members.

The 4T1 cells were chosen as a model of metastatic human breast cancer because when orthotopically implanted into the mammary glands of mice, these cells readily metastasize to the lung in a LOX-dependent manner (7, 23, 26). We found that all known LOX family members were expressed in 4T1 cells under standard culture conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), and that 4T1 tumors grown orthotopically in the mammary fat pads of BALB/c mice expressed significantly higher levels of Lox, Loxl2, Loxl3, and Loxl4 mRNAs relative to the adjacent stromal tissue (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

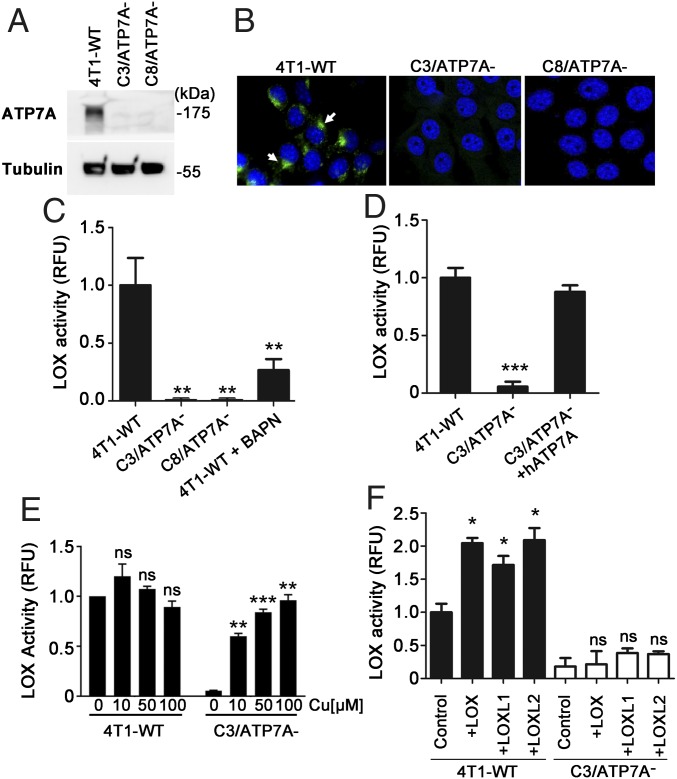

To investigate the requirement for ATP7A in LOX activity, we silenced Atp7a gene expression in murine 4T1 breast carcinoma cells using a CRISPR-Cas9 approach. Immunoblot analysis confirmed the absence of ATP7A protein in two independent CRISPR clones, C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− (Fig. 1A). We used immunofluorescence microscopy to verify that ATP7A was localized to the Golgi apparatus in wild-type 4T1 cells (4T1-WT), a site where ATP7A is thought to metallate nascent metalloenzymes within the secretory pathway (24, 27). ATP7A was localized to the perinuclear region in 4T1-WT cells (Fig. 1B), which overlapped with antibodies against the Golgi marker protein, GM130 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). As expected, ATP7A was not detected in C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the known role of ATP7A in copper export (28), copper concentrations were elevated in C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells compared with 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). However, the growth rates of C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells were not significantly different from the growth rate of 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C), suggesting that the elevated copper concentrations were not cytotoxic. LOX activity was detected in the conditioned media of 4T1-WT cells and was diminished by pretreating these cells with β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), a specific inhibitor of the LOX family of enzymes (29) (Fig. 1C). In contrast, LOX activity was virtually undetectable in the media of both C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells (Fig. 1C), suggesting that LOX activity is dependent on ATP7A expression.

Fig. 1.

ATP7A is necessary and sufficient for the copper-dependent activity of LOX family members. (A) Immunoblot analysis of ATP7A in 4T1-WT cells and 4T1 clones subjected to CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of ATP7A (C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells). Tubulin was detected as a loading control. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of ATP7A protein in 4T1-WT, C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells. ATP7A protein (arrows; green) was detected in the perinuclear region of 4T1-WT cells and was absent in C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− clones. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). (C) LOX activity in conditioned media of 4T1-WT, C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells (mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01). Activity is expressed as relative fluorescence units (RFU) normalized against 4T1-WT cells. BAPN (0.5 mM), an irreversible inhibitor of LOX, was used to confirm LOX activity in 4T1-WT media. (D) Restoration of LOX activity in the media of C3/ATP7A− cells by stable transfection of a human ATP7A expression plasmid (mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001). (E) Rescue of LOX activity in C3/ATP7A− cells by copper supplementation. LOX activity was measured in the conditioned media of 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells supplemented for 24 h with the indicated copper concentrations (mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); ns, not significant. (F) ATP7A is required for the activity of LOX, LOXL1 and LOXL2. The 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP alone (control) or in combination with plasmids encoding LOX, LOXL1 or LOXL2. After a 24 h recovery, LOX activity was assayed in the media and normalized to cellular GFP expression to control for transfection efficiency (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05); ns, not significant.

These observations were not due to off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9, because reduced LOX activity was also observed in 4T1 cells in which ATP7A was silenced using an RNAi approach (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). Furthermore, LOX activity was restored to wild-type levels in C3/ATP7A− cells transfected with a human ATP7A expression plasmid (Fig. 1D). LOX activity in C3/ATP7A− cells could be restored by the addition of supraphysiological copper concentrations to the culture medium (Fig. 1E). These observations suggest that the reduction in LOX activity in the absence of ATP7A is due to a disruption of copper delivery to LOX.

While these data support the hypothesis that ATP7A mediates copper delivery to LOX, a potential caveat to this conclusion is that commercial LOX assays, like the one used in our study, do not distinguish between the activities of different LOX family members. Thus, it was unclear from our results which of the LOX members’ activities might be dependent on ATP7A. To investigate this further, we performed LOX activity assays on the conditioned media of 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells transfected with plasmids encoding three different LOX family members—LOX, LOXL1 and LOXL2—together with a GFP expression plasmid to control for transfection efficiency. After 24 h, the media were collected, and LOX activity was measured as a function of cellular GFP expression. For 4T1-WT cells transfected with each LOX plasmid, a significant increase in LOX activity was detected in the media relative to cells transfected with the GFP vector alone (Fig. 1F). In contrast, none of the LOX plasmids produced a significant increase in LOX activity when transfected into C3/ATP7A− cells (Fig. 1F). These observations suggest that ATP7A is necessary and sufficient to metallate multiple members of the LOX family.

ATP7A Deletion in 4T1 Breast Cancer Cells Attenuates Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Mice.

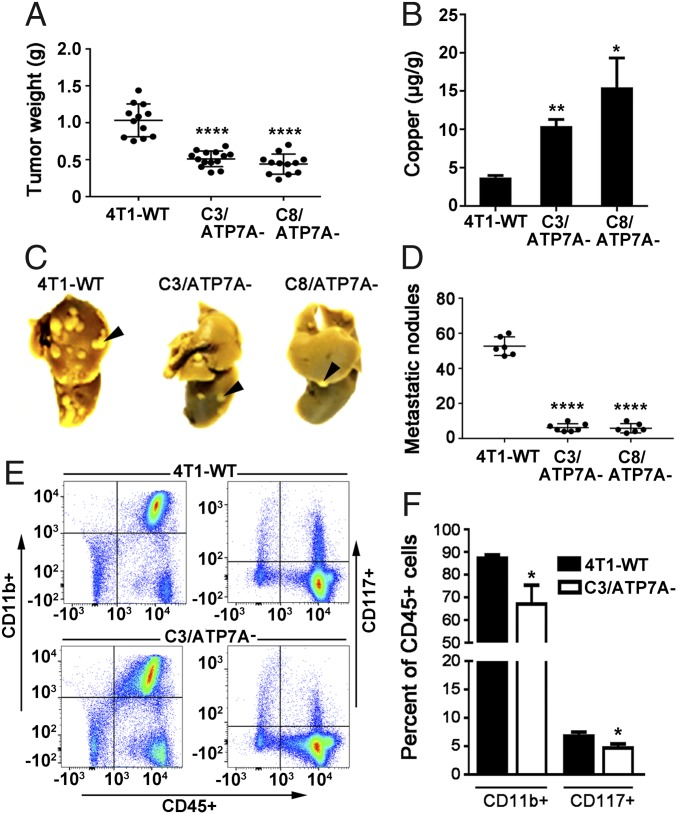

Because several members of the LOX family are known to promote tumor metastasis, we hypothesized that a loss of ATP7A might reduce metastasis of 4T1 cells. To test this hypothesis, 4T1-WT and the ATP7A-null cell lines were injected into the inguinal mammary fat pads of female BALB/c mice, and primary tumor growth and metastatic lung nodules were quantified after 4 wk. Both the C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− tumors were significantly smaller than wild-type tumors (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our findings in cultured cells, tumors derived from C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− cells accumulated significantly higher levels of copper compared with tumors derived from 4T1-WT cells (Fig. 2B). Importantly, there were markedly fewer metastatic lung nodules in mice bearing C3/ATP7A− and C8/ATP7A− tumors compared with mice bearing wild-type tumors (Fig. 2 C and D). A similar reduction in both primary tumor growth and metastasis was observed for shRNA-ATP7A cells in which ATP7A was silenced using RNAi (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C–F). We considered the possibility that the reduced metastatic potential of tumors lacking ATP7A might be attributable to a reduction in primary tumor size. However, the number of metastatic lung nodules remained markedly lower even after the ATP7A-silenced tumors were permitted to grow until they reached the same size as wild-type tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Deletion of ATP7A suppresses tumor growth and metastasis to the lungs in the orthotopic 4T1 murine breast cancer mouse model. (A) Primary tumors were isolated from mammary glands of BALB/c mice (n = 8 per group) 4 wk after injection with 4T1-WT, C3/ATP7A− or C8/ATP7A− cells (mean ± SEM; ****P < 0.0001). (B) Copper concentrations in primary tumors (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (C) Representative images of metastatic nodules in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice. Lungs were fixed in Bouin’s solution to highlight lung tumor nodules. (D) Quantification of lung nodules (mean ± SEM; ****P < 0.0001). (E) Loss of ATP7A in 4T1 tumors reduces recruitment of CD11b+ and CD117+ myeloid cells to the lungs. Representative flow cytometry scatter plot analysis of dissociated lung tissues isolated from BALB/c mice bearing 4T1-WT or C3/ATP7A tumors (n = 4). Cells were stained with antibodies against CD11b conjugated to PerCP, CD117 conjugated to APC and CD45 conjugated to VioBlue. (F) Quantification of CD11b+ and CD117+ cells as a percentage of CD45+ immune cells (mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05).

Previous studies have demonstrated that LOX and LOXL2 are necessary for the recruitment of CD11b+ and CD117+ myeloid cells to the lungs of tumor-bearing mice to promote formation of the premetastatic niche, a process that facilitates the invasion and growth of tumor cells (18, 23). Consistent with a loss of LOX activity, both CD117+ and CD11b+ myeloid cells were significantly reduced in the lungs of C3/ATP7A− tumor-bearing mice compared with 4T1-WT tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 2 E and F).

Previous studies also have shown that inhibition of LOX activity reduces the abundance of linear collagen fibrils associated with tumors (30). Using second harmonic generation imaging microscopy (30–32), we investigated whether the loss of ATP7A reduced collagen fibril assembly in primary tumors and metastatic lung nodules. As expected, tumor-associated collagen was predominantly organized in long linear arrangements (>30 µm) in 4T1-WT tumors, but in C3/ATP7A− derived tumors, the collagen fibrils were significantly shorter and exhibited an overall reduced linear organization (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). This difference was also present in the metastatic nodules in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice in which there were significantly fewer collagen fibrils in C3/ATP7A− nodules compared with those derived from 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D–F). Taken together, these data suggest that ATP7A is required for copper delivery to LOX and for LOX-dependent prometastatic processes in 4T1 cells.

ATP7A Is Necessary for LOX-Dependent FAK1 Phosphorylation.

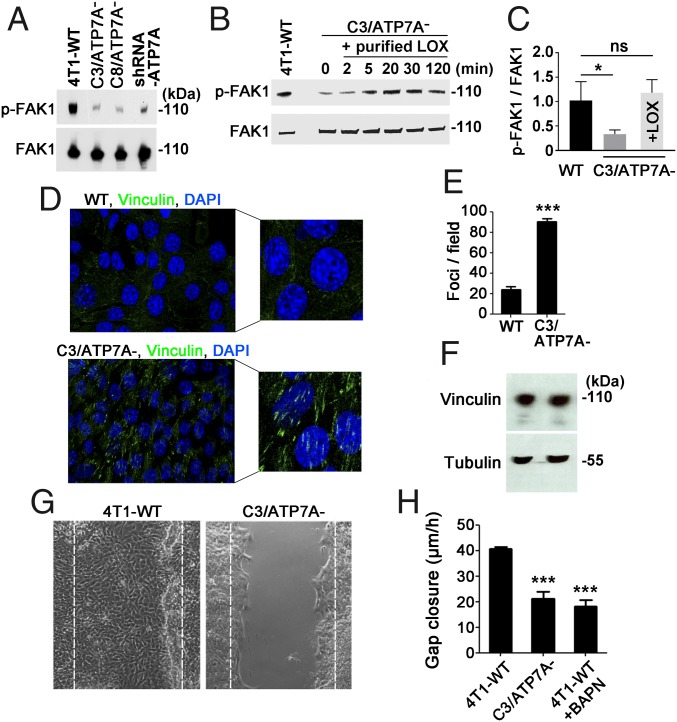

An important mechanism of LOX-mediated metastasis is the activation of FAK1, a key regulator of tumor cell adhesion and motility (21, 22, 33). Levels of phosphorylated FAK1 (p-FAK1) were found to be significantly elevated in 4T1-WT cells compared with C3/ATP7A− cells, C8/ATP7A− cells, and 4T1 cells expressing shRNA-ATP7A (Fig. 3A). Notably, FAK1 phosphorylation was restored to wild-type levels in C3/ATP7A− cells within 20 min after the addition of recombinant active LOX protein to the culture medium (Fig. 3 B and C). FAK1 is phosphorylated by the upstream tyrosine-protein kinase Src, which is activated by the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (34). Recent studies suggest that LOX activity can increase Src phosphorylation in response to EGFR signaling (35). Consistent with these findings, Src phosphorylation was reduced in untreated and EGF-stimulated C3/ATP7A− cells compared with 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). FAK1 phosphorylation is known to regulate the assembly of proteins, including vinculin, at focal adhesion sites (36, 37). In agreement with a loss of FAK1 phosphorylation, there was a significant increase in vinculin-positive focal adhesions in C3/ATP7A− cells compared with 4T1-WT cells (Fig. 3 D and E). There were no differences in total vinculin between 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

ATP7A is required for cell motility and LOX-mediated phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK1). (A) Immunoblot analysis of FAK1 phosphorylation in 4T1-WT, C3/ATP7A−, C8/ATP7A− and shRNA-ATP7A cells. Total FAK1 was detected as a loading control. (B) Immunoblot analysis of C3/ATP7A− cell lysates showing the restoration of FAK1 phosphorylation by the addition of exogenous purified LOX (1 µg/mL) to the culture medium for the indicated times. (C) Immunoblot band intensities were used to determine the ratio of p-FAK1/total FAK1 at the 20 min time point in B. Values are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. (D) Detection of vinculin (green) at focal contacts in 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were stained using DAPI (blue). (E) Enumeration of vinculin clusters at focal adhesions in 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells (mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001; n = 15 fields per sample). (F) Immunoblot analysis of total vinculin protein in 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cells. Tubulin was detected as a loading control. (G) In vitro scratch assay demonstrating diminished motility of C3/ATP7A− cells compared with 4T1-WT cells. Representative images indicating the extent of closure are shown at 24 h after scratch formation. Dashed lines indicate scratch starting points. (H) Rate of gap closure of scratched 4T1-WT and C3/ATP7A− cell monolayers (mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001). The LOX inhibitor BAPN (0.5 mM) was added to media of 4T1-WT cells as a positive control.

We next investigated the effect of ATP7A deletion on cell motility using an in vitro scratch assay. The 4T1-WT cells exhibited increased motility compared with the C3/ATP7A− cells (Fig. 3 G and H and Movies S1 and S2), which were suppressed by the LOX inhibitor BAPN (Fig. 3H). However, supplementation of exogenous recombinant LOX to the media of C3/ATP7A− cells was not sufficient to restore motility in these cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Thus, despite the requirement for ATP7A for LOX-mediated FAK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3B), LOX activity alone was not sufficient to restore motility in ATP7A-null cells.

Because ATP7A functions as a copper exporter (in addition to supplying copper to secreted cuproenzymes), we considered the possibility that the hyperaccumulation of copper in ATP7A-null cells may contribute to the tumor-suppressive effects of ATP7A silencing. At excess concentrations, copper can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), potentially resulting in cytotoxicity. Consistent with this concept, ROS concentrations were found to be elevated in ATP7A-null cells compared with 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Moreover, subtoxic concentrations of copper and H2O2 added in combination to the media were found to confer cytotoxicity in ATP7A-null cells, but not in 4T1-WT cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B) and to suppress the ability of ATP7A-null cells to form colonies in soft agar (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 C and D). These results suggest that in addition to a loss of LOX metallation, the accumulation of copper and ROS may also contribute to the inhibitory effects of ATP7A silencing on tumor growth and metastasis.

ATP7A Deletion in Lewis Lung Carcinoma Cells Inhibits LOX Activity, Tumor Growth, and Metastasis.

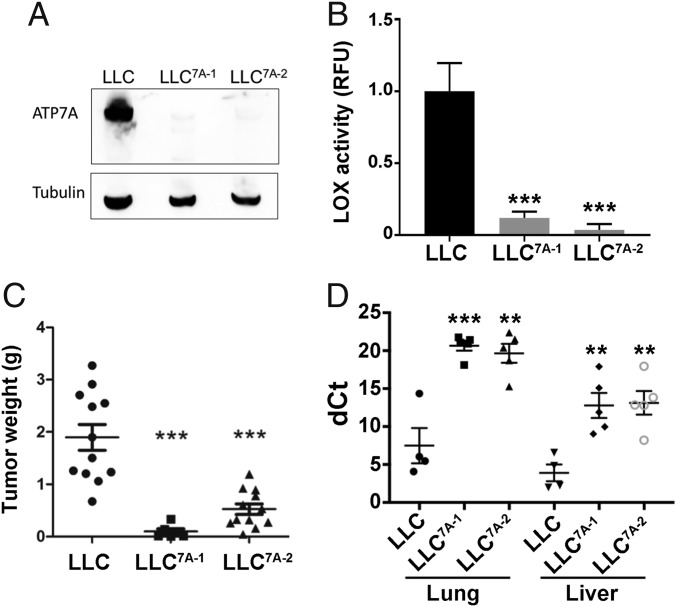

To determine whether our observations with 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells might be applicable to other cancer types, we ablated Atp7a in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells using CRISPR-Cas9. Immunoblot analysis verified the loss of ATP7A expression in two independent clones, LLC7A-1 and LLC7A-2 (Fig. 4A). Consistent with our observations in 4T1 cells, LOX activity was markedly reduced in LLC7A-1 and LLC7A-2 cells compared with wild-type LLC cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Deletion of ATP7A suppresses tumorigenesis and metastasis in the LLC mouse model. (A) Immunoblot analysis of ATP7A expression in wild-type LLC cells and LLC7A-1 and LLC7A-2 cell clones produced by CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of ATP7A. Tubulin was detected as a loading control. (B) LOX activity in culture medium of LLC, LLC7A-1 and LLC7A-2 cells (mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001). (C) Weights of primary tumor isolated from C57BL/6 mice injected s.c. with LLC, LLC7A-1, or LLC7A-2 cells (mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001). (D) LLC, LLC7A-1, and LLC7A-2 cells stably expressing mCherry were injected into the tail veins of C57BL/6 mice. After 3 wk, lungs and liver were harvested for RNA isolation and qPCR analysis of mCherry expression. Data are mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. A higher dCt value denotes a smaller metastatic burden.

To determine the effect of ATP7A deletion on tumor growth, wild-type LLC, LLC7A-1, and LLC7A-2 cells were injected s.c. into C57BL/6 mice and permitted to grow for 2 wk. Primary tumors derived from the LLC7A-1 and LLC7A-2 cells were found to be significantly smaller than those from wild-type LLC cells (Fig. 4C).

To investigate the effect of ATP7A on metastasis, LLC, LLC7A-1, and LLC7A-2 cells were injected into the tail veins of C57BL/6 mice. After 3 wk, the metastatic burden of the ATP7A-null LLC cells in both lung and liver was significantly reduced compared with that in wild-type LLC cells (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these findings suggest that ATP7A is necessary for growth and metastasis in models of both mammary and lung carcinoma.

ATP7A Expression Is Correlated with Reduced Survival in Breast Cancer Patients.

Previous studies have shown that high LOX expression is correlated with reduced survival in patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-negative breast cancer (38). We used publicly available databases to investigate the degree to which patient mortality is correlated with ATP7A mRNA expression in breast tumors. As in the case of LOX, high ATP7A expression was found to be significantly correlated with lower metastasis-free survival in patients diagnosed with ER-negative breast cancer (Fig. 5A). Together with our experimental observations, these data suggest that ATP7A promotes breast cancer malignancy in humans.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan-Meier curve of breast cancer patients stratified by ATP7A expression. (A) Kmplot.com analysis of ATP7A expression levels as a function of distant metastasis-free survival of ER-negative breast cancer patients. (B) Proposed model for ATP7A function in tumor growth and metastasis. ATP7A delivers copper to LOX family members and facilitates copper export to maintain cellular copper homeostasis (Left). Deletion of ATP7A (Right) results in hyperaccumulation of copper, increased ROS, loss of LOX activity and a reduction in LOX-mediated metastatic pathways (e.g., FAK1 phosphorylation and myeloid recruitment at metastatic sites).

Discussion

Copper chelation therapy is an experimental approach that has been shown to significantly extend the life expectancy of patients diagnosed with stage III and stage IV breast cancer (14), raising the possibility that inhibition of copper delivery to specific oncogenic metalloenzymes might offer therapeutic benefits. Prometastatic metalloenzymes that are affected by copper chelation therapy include the LOX family of enzymes, which have well-documented roles in tumor malignancy (6). Previous studies using experimental mouse models have shown that silencing LOX reduces the metastatic spread of several breast carcinoma cell lines, including 4T1 cells (23).

The rationale for our study was two-pronged: first, to test the hypothesis that the resident Golgi copper transporter ATP7A is necessary to deliver copper to members of the LOX family, and second, to test whether ATP7A silencing would attenuate LOX-dependent metastasis. Suppression of ATP7A expression in 4T1 cells using two independent approaches—CRISPR and RNAi—resulted in the loss of LOX activity in the culture medium (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). This was not the result of off-target events, because LOX activity was restored by transfection of a human ATP7A plasmid in ATP7A-null cells (Fig. 1D). The finding that excess copper added to the culture medium could restore LOX activity in ATP7A-null cells indicated that the lack of LOX activity was attributable to a failure of copper delivery to LOX (Fig. 1E). The finding that forced expression of different LOX family members increased LOX activity in 4T1-WT cells, but not in ATP7A-null cells (Fig. 1F), indicates that ATP7A is necessary and sufficient to metallate multiple LOX family members.

Consistent with a loss of ATP7A-dependent LOX activity, known pathways of LOX-dependent metastasis were attenuated in ATP7A-null 4T1 cells, including myeloid cell recruitment to the lungs, FAK1 phosphorylation, EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of Src, and tumor-associated collagen fibril assembly (Figs. 2F and 3C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6B). The finding that ATP7A deletion in LLC cells also suppressed tumorigenesis and metastasis suggests that, like members of the LOX family, ATP7A is a relevant prometastatic factor in multiple cancer types (Fig. 4). Future studies will evaluate the importance of ATP7A in other cancer models, including models of spontaneous cancer. Previous studies have demonstrated that elevated LOX expression is correlated with poor survival of ER-negative breast cancer patients (38).

Consistent with a requirement for ATP7A in LOX activity, we found that high ATP7A expression correlates with decreased survival in patients with ER-negative breast cancer (Fig. 5A). Taken together, these findings suggest a model in which ATP7A functions to metallate LOX proteins in the secretory pathway to promote LOX-mediated mechanisms of metastasis (Fig. 5B). Although FAK1 phosphorylation was restored by the addition of exogenous LOX to ATP7A-null cells (Fig. 3C), why this treatment did not restore migratory potential in these cells, as determined using the scratch assay, is unclear (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). It is possible that the correction of cell migration in ATP7A-null cells requires the activity of multiple LOX family members. It is also possible that the loss of migratory potential in ATP7A-null cells is partly attributable to LOX-independent mechanisms. Indeed, the finding that ATP7A-null cells accumulated elevated levels of copper and ROS and were sensitive to a combination of subtoxic concentrations of copper and hydrogen peroxide is consistent with this hypothesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

The importance of LOX and LOXL enzymes in different cancers has prompted intense efforts to develop small molecule inhibitors and immunotherapies against specific LOX family members (35, 39–41). The results from our study raise the possibility of a new approach to treating LOX-dependent malignancies by blocking ATP7A-mediated copper delivery to this family of enzymes. Although we did not observe a correlation between ATP7A expression and patient survival for other cancer types, such correlations may be obscured by the expression of ATP7B, another copper transporting P-type ATPase in the Golgi complex that also metallates secreted cuproenzymes. As both ATP7A and ATP7B proteins share highly conserved functional motifs, drugs could be developed that block both ATPases to provide a therapeutic benefit against cancers caused by one or more LOX family members (42–44). Furthermore, as previous studies have shown that ATP7A and ATP7B are involved in resistance to various chemotherapy drugs (45, 46), therapeutic targeting of ATP7A/B may offer additional benefits by reducing the development of chemoresistance.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Plasmids, and Reagents.

The 4T1 and LLC cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. ATP7A knockout lines were generated by transfecting wild-type 4T1 or LLC cells with a CRISPR-Cas9/GFP construct targeting exon 16 (Sigma-Aldrich), using Lipofectamine 2000. ATP7A knockdown and control 4T1 cells were generated by stable transfection of a short hairpin RNA against ATP7A or GFP (Origene), respectively. Cells were grown in complete medium consisting of DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 2 mM glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Purified LOX protein and expression plasmids for human LOX, LOXL1, and LOXL2 were purchased from Origene. BAPN was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Animals.

All animal procedures were performed with the approval of the University of Missouri’s Animal Care and Use Committee. Female BALB/c mice and male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle and fed with Picolab diet 5053 (13 ppm Cu; PMI International).

Cell Proliferation and Survival Assays.

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates (50,000 cells/well) and allowed to grow until ∼80% confluence. The Vybrant MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to measure rates of proliferation in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell survival was determined using the crystal violet assay, as described previously (47).

In Vitro Scratch Assay.

In vitro scratch assays were performed as described previously (48). Live cell imaging and video recording were performed at 37 °C and 5% CO2 using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Photometrics software was used to calculate gap closure by measuring the change in gap distance over time.

Animal Tumor Models.

Orthotopic growth of 4T1 cells in of 6- to 7-wk-old female BALB/c mice was performed as described previously (26). Primary tumors and lungs were harvested at 4 wk unless indicated otherwise. Bouin’s solution was used to identify surface metastatic nodules, which were then enumerated using dissecting microscopy. For the LLC model, 2 × 106 cells in PBS were injected s.c. into the right armpit. After 2 wk, the tumors were excised, weighed, and imaged. For investigating metastasis, LLC, LLC7A-1, and LLC7A-2 cells were stably transfected with a construct expressing mCherry and a puromycin resistance gene (Addgene plasmid 72264; Veit Hornung Lab) using Lipofectamine 2000 and selected with puromycin (1.25 µg/mL). Populations of LLC, LLC7A-1, and LLC7A-2 cells expressing equal levels of mCherry, as determined by fluorescence intensity and qRT-PCR, were isolated and injected i.v. into the tail vein. After 3 wk, the liver and right lung were excised and homogenized in TRIzol solution (Invitrogen). RNA was purified using the RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the RNA to cDNA EcoDry kit (Takara). qRT-PCR analysis was performed using 100 ng of template was used per sample. In the event of nondetectable genes, 40 PCR cycles were performed. Taqman probes for mCherry and GAPDH were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

Copper Measurements.

Tumors or cell pellets were dissolved in 70% (vol/vol) nitric acid and elemental analysis was performed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Values were acquired in triplicate for each sample and the results were normalized to weight.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as previously described (49), using the following antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse (1:1,000; ThermoFisher), anti-vinculin (1:200, clone 7F9; EMD Millipore). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (ThermoFisher). Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (46). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-ATP7A (1:1,000), anti-tubulin (1:2,000, T8328; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-phospho-FAK1 (1:1,000, 3281S; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-FAK1 (1:1,000, ab40794; Abcam) and anti-vinculin (1:1,000, 7F9; EMD Millipore). Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000, sc-2357; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific31430).

LOX Activity Assay.

LOX activity in the conditioned media was determined using the LOX activity kit (Abcam), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Where indicated, plasmids encoding LOX, LOXL1, or LOXL2 (Origene) were transiently transfected into 4T1-WT or C3/ATP7A− cells together with a plasmid encoding GFP in pQCXIP to normalize for transfection efficiency. After 24 h, GFP fluorescence was measured in transfected cells and LOX activity was assayed in the media. Mean LOX activity was normalized to GFP fluorescence. All LOX assays were performed at least three times, with similar results.

Flow Cytometry.

Lung tissue (30–70 mg) isolated from mice bearing 4T1-WT or C3/ATP7A− tumors was minced and digested for 1 h at 37 °C in RPMI media containing 4 mg/mL Collagenase D (Roche) and 2.5 mM CaCl2. Cell suspensions were passed through a 40-µm nylon filter and red blood cells were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were resuspended in PBS with 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA and 2 mM EDTA and then blocked for 10 min with Mouse BD Fc Block (553142; BD Biosciences). Cells were then incubated for 10 min at 4 °C with VioBlue-CD45 (130-110-664), Viobility 405/452 (130-110-206), PerCP-Vio700-CD11b (130-109-289) from Miltenyi Biotec and APC-CD117 (553356) from BD Bioscience. Spectral compensation was established with Ultracomp eBeads (01-222-42; Invitrogen). Fluorescence minus one samples for CD117 and CD11b were used as gating controls. Samples were run on a BD Fortessa ×20. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo v10.5.0 software.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as a minimum of three biological replicates and expressed as mean ± SEM (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 7.0. Data were analyzed using standard Student’s t test and were considered to be significant when P ≤ 0.05. Statistical significance representations: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

Clinical Association Analyses.

Distant metastasis-free survival of ER-negative breast cancer patients was stratified by ATP7A mRNA expression (Affymetrix ID: 205197_s_at) relative to the median based on publicly available databases (KMplot.com) (50).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the M.J.P. laboratory for their support and helpful comments. Confocal images were acquired at the University of Missouri Molecular Cytology Core facility. We thank Dr. Alexander Jurkevich for help with SHG microscopy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA190265 and a seed grant from the University of Missouri Life Sciences Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1817473116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nevitt T, Ohrvik H, Thiele DJ. Charting the travels of copper in eukaryotes from yeast to mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1580–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady DC, et al. Copper is required for oncogenic BRAF signalling and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2014;509:492–496. doi: 10.1038/nature13180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turski ML, et al. A novel role for copper in Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1284–1295. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05722-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papa L, Manfredi G, Germain D. SOD1, an unexpected novel target for cancer therapy. Genes Cancer. 2014;5:15–21. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishida S, Andreux P, Poitry-Yamate C, Auwerx J, Hanahan D. Bioavailable copper modulates oxidative phosphorylation and growth of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19507–19512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318431110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker HE, Cox TR, Erler JT. The rationale for targeting the LOX family in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:540–552. doi: 10.1038/nrc3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rachman-Tzemah C, et al. Blocking surgically induced lysyl oxidase activity reduces the risk of lung metastases. Cell Rep. 2017;19:774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry-Hamilton V, et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat Med. 2010;16:1009–1017. doi: 10.1038/nm.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díez M, et al. Serum and tissue trace metal levels in lung cancer. Oncology. 1989;46:230–234. doi: 10.1159/000226722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zowczak M, Iskra M, Torliński L, Cofta S. Analysis of serum copper and zinc concentrations in cancer patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2001;82:1–8. doi: 10.1385/BTER:82:1-3:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai CY, Finley JC, Ali SS, Patel HH, Howell SB. Copper influx transporter 1 is required for FGF, PDGF and EGF-induced MAPK signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady DC, Crowe MS, Greenberg DN, Counter CM. Copper chelation inhibits BRAFV600E-driven melanomagenesis and counters resistance to BRAFV600E and MEK1/2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6240–6252. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshii J, et al. The copper-chelating agent, trientine, suppresses tumor development and angiogenesis in the murine hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:768–773. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan N, et al. Influencing the tumor microenvironment: A phase II study of copper depletion using tetrathiomolybdate in patients with breast cancer at high risk for recurrence and in preclinical models of lung metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:666–676. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redman BG, et al. Phase II trial of tetrathiomolybdate in patients with advanced kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1666–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagan HM, Li W. Lysyl oxidase: Properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:660–672. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker AM, et al. The role of lysyl oxidase in SRC-dependent proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:407–424. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvador F, et al. Lysyl oxidase-like protein LOXL2 promotes lung metastasis of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5846–5859. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong CC, et al. Lysyl oxidase-like 2 is critical to tumor microenvironment and metastatic niche formation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:1645–1658. doi: 10.1002/hep.27320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker AM, Bird D, Lang G, Cox TR, Erler JT. Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK. Oncogene. 2013;32:1863–1868. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne SL, et al. Lysyl oxidase regulates breast cancer cell migration and adhesion through a hydrogen peroxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11429–11436. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erler JT, et al. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erler JT, et al. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petris MJ, Strausak D, Mercer JF. The Menkes copper transporter is required for the activation of tyrosinase. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2845–2851. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royce PM, Camakaris J, Danks DM. Reduced lysyl oxidase activity in skin fibroblasts from patients with Menkes’ syndrome. Biochem J. 1980;192:579–586. doi: 10.1042/bj1920579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 20:Unit 20.2. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im2002s39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setty SR, et al. Cell-specific ATP7A transport sustains copper-dependent tyrosinase activity in melanosomes. Nature. 2008;454:1142–1146. doi: 10.1038/nature07163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaler SG. ATP7A-related copper transport diseases-emerging concepts and future trends. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilmarth KR, Froines JR. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of lysyl oxidase by aminopropionitriles. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1992;37:411–423. doi: 10.1080/15287399209531680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levental KR, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keikhosravi A, Bredfeldt JS, Sagar AK, Eliceiri KW. Second-harmonic generation imaging of cancer. Methods Cell Biol. 2014;123:531–546. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420138-5.00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke K, Brown E. The use of second harmonic generation to image the extracellular matrix during tumor progression. Intravital. 2015;3:e984509. doi: 10.4161/21659087.2014.984509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen LC, et al. Human breast cancer cell metastasis is attenuated by lysyl oxidase inhibitors through down-regulation of focal adhesion kinase and the paxillin-signaling pathway. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:989–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luttrell DK, et al. Involvement of pp60c-src with two major signaling pathways in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:83–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang H, et al. Lysyl oxidase drives tumour progression by trapping EGF receptors at the cell surface. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14909. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphries JD, et al. Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1043–1057. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumbauld DW, Michael KE, Hanks SK, García AJ. Focal adhesion kinase-dependent regulation of adhesive forces involves vinculin recruitment to focal adhesions. Biol Cell. 2010;102:203–213. doi: 10.1042/BC20090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han Y, et al. Potential options for managing LOX+ ER− breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32893–32901. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang J, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of small molecule LOXL2 inhibitors in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:26066–26078. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X, et al. Inactivation of lysyl oxidase by β-aminopropionitrile inhibits hypoxia-induced invasion and migration of cervical cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:541–548. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox TR, Gartland A, Erler JT. Lysyl oxidase, a targetable secreted molecule involved in cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:188–192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.López B, et al. Role of lysyl oxidase in myocardial fibrosis: From basic science to clinical aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1–H9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00335.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harlow CR, et al. Targeting lysyl oxidase reduces peritoneal fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aumiller V, et al. Comparative analysis of lysyl oxidase (like) family members in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:149. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu JJ, Lu J, McKeage MJ. Membrane transporters as determinants of the pharmacology of platinum anticancer drugs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:962–986. doi: 10.2174/156800912803251199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu S, Shanbhag V, Wang Y, Lee J, Petris M. A role for the ATP7A copper transporter in tumorigenesis and cisplatin resistance. J Cancer. 2017;8:1952–1958. doi: 10.7150/jca.19029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Leverkus M. Crystal violet assay for determining viability of cultured cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016;2016:pdb.prot087379. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot087379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao X, Kim BE, Wang F, Eide DJ, Petris MJ. A histidine-rich cluster mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of the human zinc transporter, hZIP4, and protects against zinc cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6992–7000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Györffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.