Abstract

The superconducting state is formed by the condensation of Cooper pairs and protected by the superconducting gap. The pairing interaction between the two electrons of a Cooper pair determines the gap function. Thus, it is pivotal to detect the gap structure for understanding the mechanism of superconductivity. In cuprate superconductors, it has been well established that the gap may have a d-wave function. This gap function has an alternative sign change in the momentum space. It is however hard to visualize this sign change. Here we report the measurements of scanning tunneling spectroscopy in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ and conduct the analysis of phase-referenced quasiparticle interference (QPI). We see the seven basic scattering vectors that connect the octet ends of the banana-shaped contour of Fermi surface. The phase-referenced QPI clearly visualizes the sign change of the d-wave gap. Our results illustrate an effective way for determining the sign change of unconventional superconductors.

The superconducting gap structure contains important information to understand the pairing mechanism of unconventional superconductivity. Here, by using a newly established phase-referenced quasiparticle interference technique, the authors visualize the sign change of the d-wave superconducting gap directly in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ.

Introduction

In superconductors, the charge carriers are Cooper pairs which carry the elementary charge of 2e. This can be easily concluded from the measurements of the quantized flux Φ0 = h/2e = 2.07 × 10−15 Wb based on the Ginzburg–Landau theory. The core issue and also the most hard problem for understanding the mechanism of superconductivity is how the two conduction electrons are bound to each other to form a pair, the so-called Cooper pair. In the theory of Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS), it was predicted that the Cooper pairs in some superconductors, mainly in elementary metals and alloys, are formed by exchanging the virtue vibrations of the atomic lattice, namely phonons. The two electrons in the original paired state (k, −k) will be scattered to another paired state (k′, −k′). This scattering will lead to the attractive interaction Vk,k′, and the electron bound state will be formed with the help of suitable Coulomb screening. Condensation of these electron pairs will lead to superconductivity. This condensate is protected by an energy gap Δ(k) which prevents the breaking of Cooper pairs. Usually the gap is a momentum dependent function which is closely related to the pairing interaction function Vk,k′. For example, in above mentioned pair scattering picture, one can easily derive the function

| 1 |

Here, with ε the kinetic energy of the quasiparticles counting from the Fermi energy EF. If this pairing process can apply to other unconventional superconductors, the sign of the gap Δ(k) would change if the pairing interaction Vk,k′ is positive.

For cuprate superconductors, it has been well documented that the gap has a d-wave form Δ = Δ0cos2θ. This basic form of the gap was first observed by experiments of angle resolved photo-emission spectroscopy (ARPES) without sign signature1,2, and later supported by many other experiments, such as thermal conductivity3, specific heat4,5, scanning tunneling microscopy (STM)6–8, neutron scattering9,10, and Raman scattering11, etc. Although some of the techniques mentioned above may involve the sign change of the gap, such as the inelastic neutron scattering and STM measurements, they cannot tell how the gap sign changes explicitly along the Fermi surface in the momentum space.

In the model system of cuprate superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ (Bi-2212), the low energy excitations have been measured very carefully by STM yielding the seven scattering vectors or spots in the Fourier transformed (FT-) quasi-particle interference (QPI) pattern12,13. These seven scattering vectors were explained very well with the Fermi arc picture as evidenced by ARPES measurements14. Combining the magnetic effect on the QPI intensities of the different vectors, Hanaguri et al.15 showed the well consistency of a d-wave gap, if assuming that the magnetic vortices behave like magnetic scattering centers and that leads to the enhancement (suppression) of the joint QPI intensity of two momenta (k1, k2) with the gaps of the same (opposite) signs. The sign problem of a d-wave gap was also resolved by the experimental devices based on the Josephson effect16–18. Therefore d-wave superconducting gap has been well concluded in cuprate superconductors by using many experimental tools.

In this paper, we report the experiments and analysis based on the defect-induced bound state (DBS-) QPI method19,20 on Bi-2212 by concerning the referenced phases at positive and negative energies. Actually in conventional superconductor 2H-NbSe2 with magnetic impurities, and anti-phase feature of the bound states at positive and negative energies were found21. The authors successfully interpreted this effect as the phase difference of the Shiba function at positive and negative biased energies. Our results illustrate the direct visualization of the sign change of the d-wave gap in bulk Bi-2212.

Results

Topography and tunneling spectra measured on Bi-2212

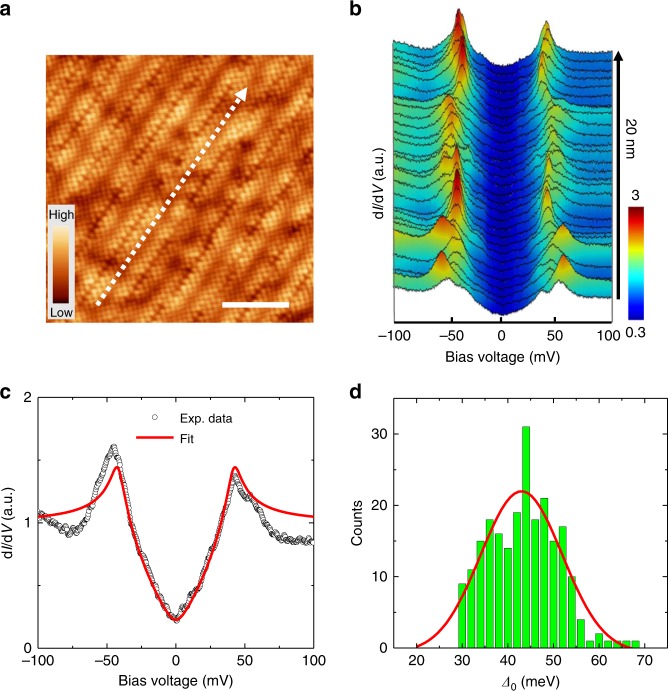

Figure 1a shows a typical topographic image of the BiO surface of Bi-2212 with an atomic resolution after cleavage. The supermodulations in the real space can be clearly witnessed on the surface with a period of about 2.54 nm. We can also recognize a square lattice structure with the lattice constant a0 about 3.8 Å, even with the appearance of the supermodulations. In Fig. 1b, we present a sequence of tunneling spectra measured along the arrowed line in Fig. 1a. The spectra show the V-shaped bottoms near zero bias, which reveals the intrinsic feature of the gap nodes in optimally doped Bi-2212. One can also clearly see the spatial variation of the coherence-peak positions, being consistent with previous reports6,7,22. We then chose one typical spectrum in Fig. 1b and plot it in Fig. 1c. The finite zero-bias differential conductance implies the effect of the impurity scattering6,7,23 in the case of a nodal gap. We then use the Dynes model24 with a d-wave gap function Δ(θ) = Δ0 cos2θ to fit the tunneling spectrum, and the fitting result is also shown in Fig. 1c by the red line. The resultant fitting yields the parameters of gap maximum Δ0 = 42 meV, and the scattering rate Γ = 4 meV. One can see that the fitting curve with the d-wave gap function captures the major characteristics except for the feature of the coherence peak on the negative-bias side. It should be noted that the gap maximum equals approximately to the coherence-peak energy in a d-wave superconductor when the scattering rate is small. Following this conclusion, we carry a statistical analysis of the gap maximum values from the coherence-peak energies of about 200 spectra measured in our experiments on optimally doped Bi-2212 samples, and the related histogram of the gap distribution is presented in Fig. 1d. One can see that the distribution of Δ0 behaves as a Gaussian shape with an averaged gap maximum obtained from the fitting.

Fig. 1.

Topographic image and tunneling spectra measured on optimally doped Bi-2212. a A typical topographic image of the BiO surface after cleavage measured at bias voltage Vbias = 50 mV and tunneling current It = 100 pA. Scale bar, 5 nm. b Tunneling spectra measured along the arrowed line in a. The set-point conditions are Vset = 100 mV and Iset = 100 pA for measuring all the spectra in b. c A typical spectrum (open circles) selected from b. The solid line shows the Dynes model fitting result with a d-wave superconducting gap. d The statistics of superconducting gap maxima Δ0 for about 200 tunneling spectra measured on the Bi-2212 samples, and the gap maximum values are determined from the positions of the coherence-peaks. The red curve is a Gaussian fitting result with the peak position near 43 meV

Identification of scattering wave-vectors in FT-QPI pattern

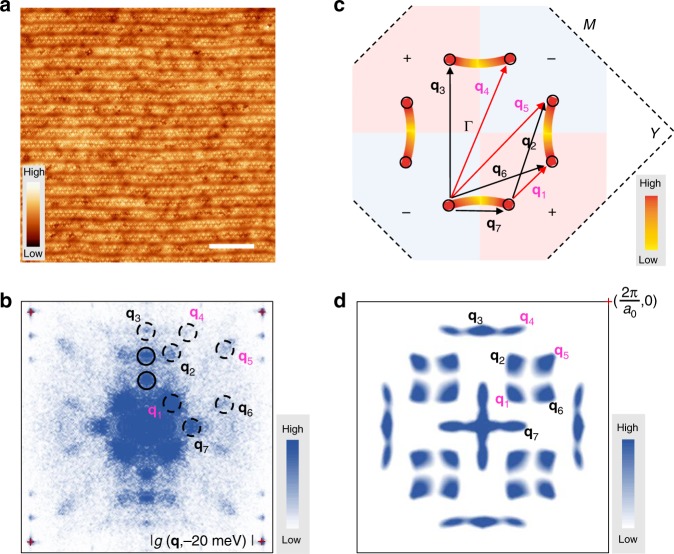

Figure 2a shows a topographic image with the dimensions of 56 × 56 nm. In this area, we measured the QPI images g(r, E) at different energies, and then obtained the FT-QPI pattern g(q, E) in q-space through the Fourier transform. Figure 2b shows a typical FT-QPI pattern at –20 meV. Since we have done the lattice correction process by using the Lawler–Fujita algorithm25, the four Bragg peaks are very sharp near the red crosses marked in Fig. 2b. Based on the octet model12, the octet ends of the banana-shaped contour of constant energy (CCE) has relatively higher density of states (DOS). Therefore, the major scattering will occur among these hot spots. As expected, we can clearly distinguish all the primary scattering wave vectors qi (i = 1 to 7) indicated by dashed circles in the FT-QPI pattern. Besides, two additional pairs of spots, which are indicated by solid-line circles, are originated from the supermodulations12. It should be noted that the q7 spots at the horizontal direction are not influenced by the supermodulations. Figure 2c shows a schematic plot of the contours at a particular energy below the superconducting gap maximum in a typical cuprate superconductor like Bi-2212, and the DOS at the octet ends are set to be maximum. By assuming a certain width for the Fermi arcs in Fig. 2c, we then apply the self-correlation and show the simulated FT-QPI result in Fig. 2d. One can see that the simulated patterns are similar to those in the experimental FT-QPI pattern, which can help identify different primary scattering wave vectors. In a d-wave superconductor, the superconducting gap changes its sign in k-space along the Fermi surfaces, and we use different background colors to show this sign-change feature in Fig. 2c. With the aid of light pink and light blue colors for different gap signs, we can divide the scattering wave vectors into two groups, i.e., gap-sign-reversed scatterings (with scattering wave vectors of q2, q3, q6, and q7) and gap-sign-preserved ones (q1, q4, and q5).

Fig. 2.

Different kinds of scattering wave-vectors in FT-QPI pattern. a Topographic image of the BiO plane (Vbias = −200 mV, It = 50 pA). Scale bar, 10 nm. b FT-QPI pattern (Vset = −100 mV, Iset = 100 pA) at E = −20 meV based on the QPI image measured in the area of a. Four Bragg peak positions are marked by the red crosses. The solid-line circles indicate the scattering spots contributed by the supermodulations, while the dashed circles indicate the primary scattering spots with different q vectors. c A schematic plot of the contours of constant energy. The DOS along the Fermi surface is set to be k-dependent, and the intensities at the octet ends of CCE are the strongest. The different colors of light pink and light blue show the regions with different gap signs for the d-wave gap function. The scatterings along black arrows (q2, q3, q6, and q7) are for sign reversal gaps, while the scatterings along magenta arrows (q1, q4, and q5) are sign-preserved ones. d The simulation of FT-QPI by applying the self-correlation to c

Energy evolution for different scattering vectors

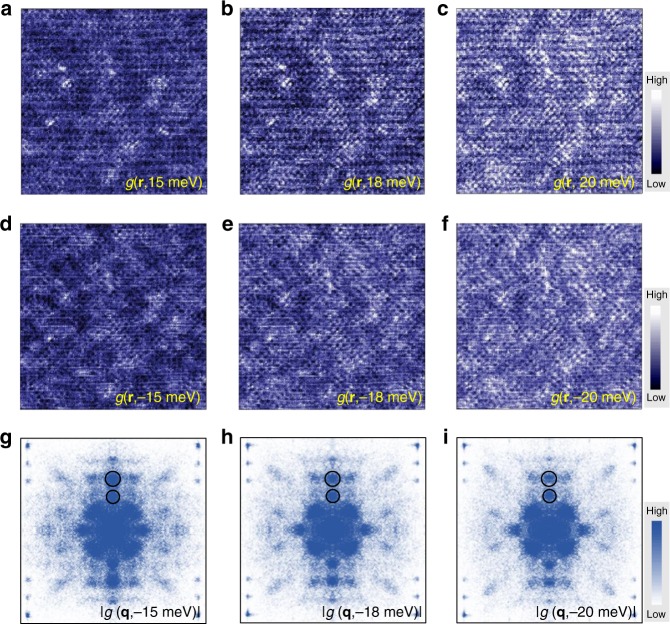

It is known that the Bogoliubov quasiparticles will be scattered by impurities and the induced standing waves will interfere with each other, giving rise to the Friedel-like oscillations of local DOS (LDOS). Figure 3a–f present the QPI images measured at different energies. We can see clear standing waves in these QPI images, which are due to the scattering by some impurities or defects in the sample such as randomly distributed oxygen deficiencies23. The longitudinal periodic modulations as shown in the topography of Fig. 2a mainly contribute the spots enclosed by the solid-line circles along qy in Fig. 2b. While the other spots in Fig.2b should be contributed by the scatterings between the octet ends of CCE. We then do the Fourier transform to QPI images and show them for three selected energies in Fig. 3g–i, and the measured QPI images together with the corresponding FT-QPI patterns at other energies are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. One can clearly recognize the scattering spots from the supermodulations and seven characteristic scattering channels in the FT-QPI patterns. It should be noted that the coordinates of supermodulation spots in FT-QPI patterns are non-dispersive in energy, which can also be taken as a justification for the origin of the supermodulation. However, the q-vectors of seven characteristic scattering spots seem to be dispersive, which can be naturally illustrated by the octet model12.

Fig. 3.

QPI and FT-QPI patterns measured on Bi-2212. a–f Differential conductance mappings at different energies. g–i Three corresponding FT-QPI patterns of d–f, respectively. The supermodulations contribute to the FT-QPI intensity surrounded by the solid-line circles, and these spots seem to have very weak energy dispersion

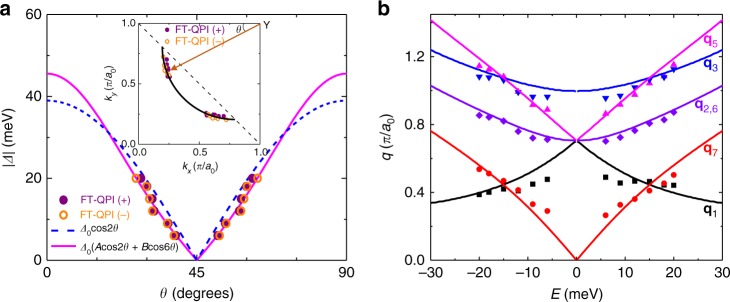

To obtain the information of superconducting gaps, we then analyze the energy dispersions of the characteristic scattering wave vectors. The intensities of the spots corresponding to q1 and q7 scattering vectors are stronger than the spots corresponding to other scattering vectors, and the central coordinates of these spots can be obtained by fitting to a two-dimensional Lorentzian function13. In principle, these two scattering wave vectors can provide enough information to fix the coordinates of the octet ends of CCE at various energies within the superconducting gap maximum. The resultant positions of the ends of CCE are shown in the inset of Fig. 4a, and the data allow us to construct part of the Fermi surface. The solid curve in the inset is a fitting result to the positions of the ends of CCE by a circular arc. The curve, which is intentionally cut off by the dashed line26, represents the contour of the Fermi surface of Bi-2212 at this doping level. From the inset of Fig. 4a, we can also define the angle of these ends of CCE to the (0, π) to (π, π) direction. With the combination of the defined angle θ and the measured energies as the absolute values of superconducting gaps at the ends of CCE, we can obtain the angular dependent superconducting gap Δ(θ) along the Fermi surface and show it in Fig. 4a. The obtained Δ(θ) data are fitted by two different d-wave gap functions, i.e., Δ1(θ) = 39cos2θ meV and Δ2(θ) = 45.6 (0.9cos2θ + 0.1cos6θ) meV, and the latter shows a better consistence with the experimental data. Therefore, the gap function in optimally doped Bi-2212 may have a higher order in addition to the d-wave component, which is consistent with previous report12. Looking back to other scattering spots, the intensity of q4 scattering spot is very weak, thus the dispersion associated with q4 scattering spot is not shown here. The positions of q2 and q6 scatterings are equivalent with only the exchange of kx and ky coordinates. Thus, we focus only on five sets of characteristic scattering spots with the center coordinates obtained by the fittings to two-dimensional Lorentzian functions. The obtained energy dispersions of these characteristic wave vectors are presented in Fig. 4b, being consistent with previous reports8,12,22. The solid curves in Fig. 4b represent the predicted energy dispersions based on the Fermi surface in the inset of Fig. 4a and the gap function Δ2(θ). One can see that the calculated curves agree well with the experimental data, which indicates the validity of the octet model and the d-wave superconducting gap.

Fig. 4.

Energy dispersions for characteristic scattering wave vectors and superconducting gap. a Superconducting gap Δ(θ) (circles) and two fitting curves by different d-wave gap functions. The inset in a shows the positions of the ends of CCE determined by q1 and q7 measured at various energies. The solid line shows the Fermi surface from the fitting to these positions by a circular arc, and it is cut off by the dashed line. The angle θ for each end of CCE is defined in the inset. The gap value Δ for each end of CCE is equivalent to the energy at which the QPI data are measured. b Energy dispersion of the scattering wave vectors taken from the FT-QPI data (excluding q4 due to very weak intensity). The solid lines represent the theoretical predictions based on the Fermi surface and the d-wave gap function with high order shown by the line with magenta color in a

Theoretical approach of using the DBS-QPI method

The PR-QPI method was first theoretically proposed by Hirschfeld, Altenfeld, Eremin, and Mazin in a two-gap superconductor27, which was successfully applied to prove the gap-sign-change in iron-based superconductors for a non-magnetic impurity28,29. The recently proposed DBS-QPI method19,20 is designed for judging the gap-sign issue in iron-based superconductor LiFeAs around a non-magnetic impurity, and is also successfully used to confirm the gap sign-change in (Li1−xFex)OHFe1−yZnySe from our recent work30. In this method, the QPI image g(r, E) is measured in an area with a non-magnetic impurity sitting at the center of the field of view (FOV). The FT-QPI data, which comes from the Fourier transform of g(r, E), are complex parameters containing the phase information, namely . Then the phase-referenced (PR-) QPI signal can be extracted from the phase difference between positive and negative bound state energies, that is defined by

| 2 |

| 3 |

Here, gr(q, +E) should be always positive by the definition, and gr(q, −E) should be negative near the bound state energy for the scattering involving the sign-reversal gaps at k1 and k2 (q = k1 − k2). That conclusion was drawn by the simulation for a nodeless superconductor when the gap changes its sign for different Fermi pockets in LiFeAs (refs. 19,20). Our studies in (Li1−xFex)OHFe1−yZnySe reveal that this method can also work for concentric two-circle like Fermi surfaces when the gaps on them have opposite signs30.

In cuprates, the gap value varies continuously and gap nodes appear in the nodal direction (Γ − Υ) on the Fermi surface. The FT-QPI patterns have already been calculated in several previous works on cuprate systems31–37. However, it is very curious to check whether this phase-referenced DBS-QPI method is still applicable in a d-wave superconductor. Before checking, it seems that there are no bound state peaks on the tunneling spectrum in our present sample, but nevertheless the DBS-QPI technique can still be applicable. In cuprates, the intrinsic nanoscale electronic disorders such as oxygen vacancies or crystal defects can act as the scattering centers, which will influence the tunneling spectra23. According to the previous calculation38, if the scattering potential is small, the bound state peaks are absent in a d-wave superconductor. To further elaborate this issue, we do the theoretical calculations by a standard T-matrix method31 with the details described in Method part. We use a d-wave gap in the calculation, and the calculated angle-dependent superconducting gap and Fermi surface in Supplementary Fig. 2a are consistent with the experimental data. Supplementary Fig. 2b shows the tunneling spectra at an impurity-free area and on site of the non-magnetic impurity with scattering potential Vs = 20 meV. One can see that there are no obvious in-gap bound state peaks near zero-bias; the non-magnetic impurities only induce resonance state and produce a continuous change of DOS within the superconducting gap when the scattering potential is small. The further calculated spectra are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 with different scattering potentials. One can see that the clear resonance peaks can be observed only when |Vs| is much larger than 100 meV. Otherwise, there are only asymmetric intensity change or some small humps within the gap. The simulation results following the DBS-QPI method for a single impurity are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–4. One can see that the PR-QPI signal for the gap-sign-preserved scatterings (q1, q4, and q5) are all positive, while the signal for the gap-sign-reversed ones (q2, q3, q6, and q7) are all negative, which gives a sharp contrast. Concerning the gap sign change issue, the simulated results in a d-wave superconductor are consistent with the situation in the s± superconductor LiFeAs (refs. 19,20), and this validates our calculation method.

Multi-DBS-QPI method applied on experimental data in Bi-2212

As shown in the line-scan spectra in Fig. 1b, it seems there are no sharp bound state peaks at energies below 30 meV, however, we do have observed the QPI images reflecting the seven characteristic spots. This tells that the standing waves on the QPI images are obviously induced by the widely distributed non-magnetic impurities which lead to resonance states instead of sharp bound state peaks in Bi-2212. For better illustrating this point, we have conducted several other line-scan measurements in the sample and presented the results in Supplementary Fig. 5. One can see that, in all three line-scan spectroscopies, although the tunneling spectra are relatively homogenous at low energies, small kinks or humps are however observed on many of the spectra at the energies from 10 to 30 meV. In addition, all the spectra show sizable magnitude of DOS near Fermi energy. This is certainly induced by pair breaking effect from impurity scattering. Combining the theoretical calculations and our experimental results, we believe that the resonance states do exist on the spectra and are induced by widely distributed non-magnetic impurities with relatively weak scattering potentials. Thus, it is difficult to find the exact impurity locations. Given the absence of the bound state peaks, we still try to analyze the measured QPI data to obtain the information of gap sign by using the DBS-QPI method.

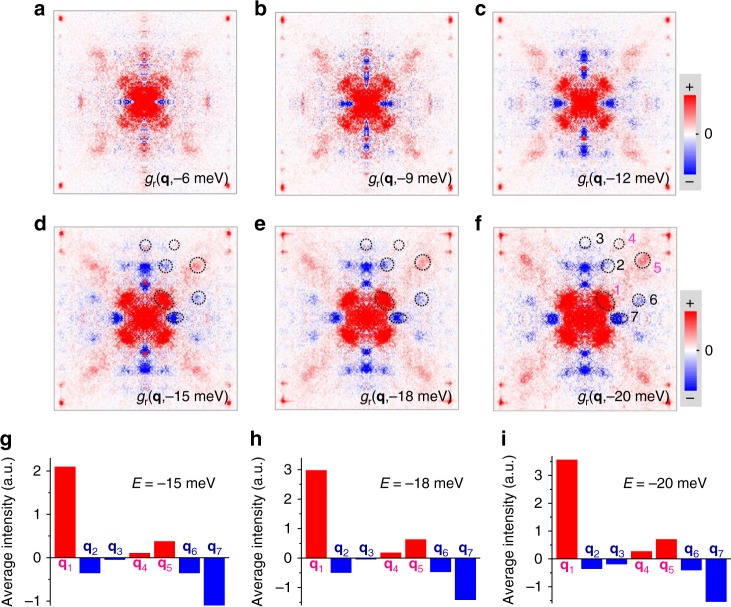

Figure 5a–f show the PR-QPI patterns at different negative energies. The PR-QPI patterns at positive energies are not shown here, because all the signals should be positive without any extra phase information according to Eq. (2). At energies from −6 to −12 meV, the gr(q,−E) signals of q1 and q7 are clear and easily recognized. When the energy is lowered down to below −15 meV, all the seven characteristic scattering spots become even more clear and can also be easily recognized. We then calculate the average value to the signals in the areas within the dashed-circles or ellipses in Fig. 5d–f, and the histograms of the average intensities per pixel corresponding to different scattering channels are shown in Fig. 5g–i. The signals corresponding to q1, q4 and q5 spots are positive, while those corresponding to q2, q3, q6 and q7 spots are negative. According to the logic possessed by the DBS-QPI method, we naturally argue that those k points in the momentum space connected by q1, q4 or q5 have sign-preserved superconducting gaps, and those connected by q2, q3, q6 or q7 have sign-reversed ones. This conclusion is consistent very well with our theoretical calculation above by using a d-wave gap function. Since the theoretical model used for the Fermi surface is rather rough, it is thus reasonable to see different intensities of the corresponding spots of the PR-QPI signal between the experimental data (Fig. 5g–i) and the calculated results (Supplementary Figs. 2–4), which will be further addressed below. In order to show the validity of this conclusion, we have done some control experiments on other two samples in three different areas, and the results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7. One can see that the new results are well consistent with those presented in Fig. 5, and they show exactly the expected results for a d-wave superconducting gap. It should be noted that the sign difference for corresponding scattering spots can be easily recognized at energies below 25 meV; however, the sign cannot be resolved when the energy is above 25 meV (Supplementary Fig. 6). The reason for this is that the characteristic scattering spots themselves become blurred at the energies above 25 meV, and only a central spot is left when the energy is near the superconducting gap (~40 meV). This seems to be a common feature in Bi-2212 samples, which was also reported in previous studies8,13,22. The reason is unclear yet, and it could be induced by the involvement of the anti-nodal region which is more associated with the pseudogap13,39. This can also explain the spatial variation of the intensity and shape of the coherence peaks in Bi-2212. An alternative picture for this spatial variation of coherence peaks would be the combination of disorder and electron–electron interactions as inferred in two-dimensional electron gas system Pb/Si(111) monolayer film40. This requires of course further verification.

Fig. 5.

PR-QPI signal by multi-DBS-QPI method. a–f PR-QPI images obtained directly from the FT-QPI patterns measured at different energies. Each digit in f denotes the position of each characteristic scattering wave-vectors. g–i Averaged intensity per pixel of PR-QPI signal for each q at −15, −18, and −20 meV, respectively. The areas for the integral and average are marked by dashed circles or ellipses in d–f

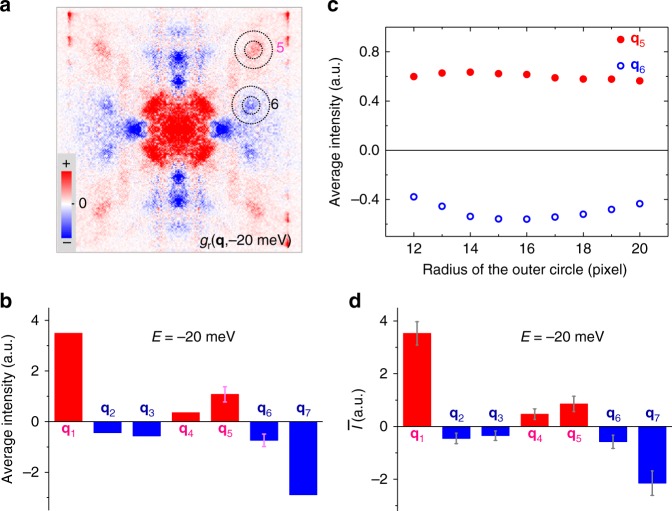

Concerning the error bars on the PR-QPI intensities, in Fig. 6 we illustrate the statistical results measured on three samples in four different areas at ±20 meV and add the error bars to the related figures. For the measurement in one field of view (FOV) as shown in Fig. 5g–i, it has no doubt for the signs of the PR-QPI signal for q1 and q7 spots. Since the octet model is widely accepted in cuprates, our data for q1 and q7 undoubtedly show the sign change of a d-wave model. For other spots with weaker intensities, such as q5 and q6, we calculate the averaged intensity of the PR-QPI signal within the two circles by gradually increasing the radius of the outer circle. One can see that the averaged value outside the inner circle (shown in Fig. 6c) is rather stable versus the calculated circle size, and we thus take the average value of those data as the error bar for this particular spot. In this way we did calculations for q5 and q6 spots. One can see that the sign keeps unchanged even considering the error bars. For four different FOVs measured at ±20 meV as shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, we take average of the intensities for each spot. The corresponding error bar is calculated through the standard deviation defined as , with the averaged intensity of one particular spot in four FOVs. The results are presented in Fig. 6d. It is clear that the error bars are all smaller than the intensities of the corresponding spots.

Fig. 6.

Control experiments and error analysis of the PR-QPI signal. a Experimental PR-QPI pattern measured on another sample and analyzed by multi-DBS-QPI method. b Averaged intensity per pixel of PR-QPI signal for each scattering spot. c The averaged intensity of the PR-QPI signal within the two circles shown in a. This calculation for determining possible error bars is specially done for q5 and q6 spots with the increasing size of the outer circle. The averaged values of these data are taken as the error bars for q5 and q6 spots and shown in b. d The average of the intensities for each scattering spots measured in four areas of three samples at ±20 meV. The error bars in d are calculated through the standard deviations from the statistics. Note the error bars in b and d have different meanings. Those in b give the uncertainty of the PR-QPI intensity calculated for a particular scattering spot in one FOV. Those in d reflect the uncertainty among different FOVs and samples

From above analyses we are confident that the obtained sign of the phase-referenced signal will not change for the related spots even considering the error bars. For some spots, such as q3 and q4, the phase-referenced intensity are really very weak. The major reason for this is that the scattering intensities themselves are very weak as shown in Fig. 3. Such weak intensity at large q-vector may arise from following three reasons. First, the STM tip is not infinitely sharp, then the high-q signals with faster oscillations in real space cannot be completely resolved. Second, the spatial variation of the wave function (Wannier function) may further suppress the high-q signals41. Third, our measurements are done in areas with finite size, which leads to the weaker intensity for large-q scattering.

We should point out that there are some differences of the PR-QPI intensity for different scattering spots between theoretical calculations and experimental data, although the signs are consistent each other. We realize that the theoretical calculation here can only serve as a qualitative interpretation. The shapes of the simulated FT-QPI patterns in Supplementary Figs. 2–4 are clearly different from the measured results, for example, the sizes of the scattering spots cannot be well determined from the theoretical calculations since the FT-QPI intensity shows some kind of continuing evolution in the momentum space. Actually, the Fermi surface in cuprates is very complex, and the theoretical model based on a single tight-binding band structure can only capture some features of the QPI results. Furthermore, the cuprate systems have strong correlation effect, and the Fermi arcs/pockets observed by experiment cannot be well understood by the band theory. Thus, it is reasonable to have discrepancy between experiment and theory concerning the intensity and the size of the FT-QPI spots.

Discussion

Although consistency has been found between the experimental data and theoretical calculations by using the DBS-QPI technique, however, one may argue that the original phase-referenced QPI method19,20 was specially designed for the case of a single impurity. In the case of Bi-2212, there may be many randomly distributed weak impurities which prevent us from finding an area with a well-isolated impurity. As a result, we can only measure in a large area with multiple impurities with a complex pattern of standing waves in the conductance mappings as shown in Fig. 3a–f. Our primary concern is whether the phase message of the order parameter can be effectively extracted in the case of multiple impurities.

The initial theoretical work of the DBS-QPI technique19 has actually provided a treatment for the multi-impurity system by applying the phase correction42 to the measured FT-QPI pattern for multiple impurities gm(q, E). The FT-QPI for a single impurity can be derived as

| 4 |

Here is the correction term with Rj the location of the jth impurity. The subscripts s, m, and C represent the cases for single impurity, multi-impurity, and correction term, respectively. The φm(q, E) and φc(q) are the phases of gm(q, E) and C(q), respectively. The prerequisites for using this formula are assuming identical scattering potentials for all impurities and no interaction among them. The PR-QPI signal for a single impurity can be obtained by applying Eqs. (2) and (3) to the corrected FT-QPI gm(q, E), see Eq. (4). From the QPI images shown in Fig. 3, one can clearly see that there should be many weak impurities on the surface and it is very difficult to determine the exact coordinates of these impurities. Considering the fact that the correction factor is energy independent and yields a common phase shift for both positive and negative energy, the phase for single impurity after correction can be written as φs(q, ±E) = φm(q, ±E) − φC(q), and the phase difference φs(q, −E) − φs(q, +E) = φm(q, −E)−φm(q, +E) remains unchanged before and after correction. It means that the sign of PR-QPI signal at the negative energy for multiple impurities will be exactly the same as the one for a single impurity.

For this issue we can also get support from the theoretical calculations. To illustrate that, we calculated the results for 60 impurities randomly distributed on the surface with the same scattering potential Vs = 20 meV, and also for 60, 100, and 500 randomly distributed impurities with the random scattering potential values from 0 to 100 meV. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. We want to emphasize that we have already taken the interference between impurities into account in the calculation, in other words the result of the multi-impurity is not the linear summation of the effect arising from individual impurities. Our simulation results show that the PR-QPI signal for each particular scattering spot (Supplementary Fig. 8) under different multi-impurity situations mentioned above has the same sign but different value compared with the situation of the single impurity (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). We have repeated each kind of simulation for 100 times with different distributions of the impurities, and can obtain the same conclusion. Hence, this phase-sensitive method for multi-impurities can provide us the same message as for a single impurity.

As presented above, we use the multi-DBS-QPI method to prove the superconducting gap reversal in optimally doped Bi-2212, which is consistent very well with the d-wave gap structure. However, with these results, one may argue that perhaps the sign-preserved gap also gives rise to such changes of the phase difference between the positive and negative energies. It has been calculated and argued that, the scattering from a non-magnetic impurity can barely induce an impurity bound state in an isotropic-s-wave superconductor43. If the gap is highly anisotropic, or say its value varies in a wide range, there may be some impurity induced bound states even if the superconducting gap is nodeless. We thus carry out further simulations for the superconductors with different gap functions, for examples, a nodal but sign-preserved gap and a nodeless gap . The same scattering scalar potential Vs = 20 meV is used for the non-magnetic impurity. The resultant tunneling spectra for above two gaps are shown in Supplementary Figs. 9a and 10a, respectively. One can see that the non-magnetic impurities only slightly shift the position of the coherence-peaks, and have negligible influence on the LDOS near zero bias. We also calculate the PR-QPI images for the single and multi-impurity situation with different forms of the sign-preserved superconducting gaps mentioned above, and the related simulations are shown in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10. One can see that the results for the multi-impurity situation are always similar to the case for a single impurity. Furthermore, all the PR-QPI signals for seven characteristic scattering spots are positive in this case. Therefore, we exclude the possibility of the sign-preserved gap in Bi-2212.

Another argument concerning our conclusion may be that the impurities could be magnetic ones instead of non-magnetic ones. The calculation for the magnetic scattering should be carried out and compared with experiment. This is actually not relevant for the optimally doped Bi-2212 since, as far as we know, no magnetic impurities with even moderate scattering potentials have been reported in literatures44. We further corroborate this point with two more basic arguments. (1) If the magnetic impurities with certain scattering potential are present, we would have seen some strong resonant state peaks within the gap. This has not been observed in such samples. (2) We have also done the calculations for superconductors with a d-wave gap with magnetic impurities, and find that the PR-QPI signals for seven characteristic scattering spots are of the same signs when the magnetic scattering potential (Vm) is smaller than 200 meV, see Supplementary Fig. 11. By using the DBS-QPI method, we clearly prove the sign-changing d-wave pairing symmetry in optimally doped Bi-2212. Our experiments and analyzing technique suggest that this method may also be applicable to other unconventional superconductors if the gap has a sign change. This will provide a more easily accessible way to determine the gap structure of unconventional superconductors.

Methods

Sample synthesis and characterization

Optimally doped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ single crystals were grown by the floating-zone technique45. The quality of the sample has been checked by the DC magnetization measurement before the STM measurements. The critical temperature Tc is about 90 K as determined from the DC magnetization measurement.

STM/STS measurements

The STM/STS measurements were done in a scanning tunneling microscope (USM-1300, Unisoku Co., Ltd.) with ultra-high vacuum, low temperature, and high magnetic field. The Bi-2212 samples were cleaved at room temperature in an ultra-high vacuum with a base pressure of about 1 × 10−10 torr. The electrochemically etched tungsten tips or the Pt/Ir alloy tips were used for all the STM/STS measurements. A lock-in technique was used for measuring tunneling spectrum with an ac modulation of 1.5 mV and 987.5 Hz. All the data were taken at 1.5 K. The QPI images were measured with the resolution of 256 pixels × 256 pixels. The set-point condition was Vset = −100 mV, Iset = 100 pA. QPI images were measured individually for each pair of positive and negative energies ±E, and each scanning took about 2000 min. The FT-QPI patterns were corrected by using the Lawler–Fujita algorithm25 to reduce the distortions from the non-orthogonality in the x/y axes. This correction can raise the signal-to-noise ratio of FT-QPI patterns and it should not give influence on the final determination of the sign of the PR-QPI signal corresponding to each primary scattering spot. The presented FT-QPI and PR-QPI patterns were mirror-symmetrized to reduce the noise. When treating the QPI data of sample 2, we have removed an unphysical background signal showing as two vertical lines appearing symmetrically around qx = 0. This will not give influence on the final results of PR-QPI.

Theoretical calculations

We have employed a single tight-binding band structure similar to the one proposed in the previous report46, with the energy dispersion given by

| 5 |

The parameters (t1, t2, t3, t4, μ) = (100, 36, 10, 1.5, −155) are used in the calculations with the units of meV. Using a standard T-matrix method31, we simulate the LDOS around a single impurity and for the case of multiple impurities. In Nambu space, the BCS Hamiltonian is given by

| 6 |

Suppose that we have N impurities located at r1, r2, r3, …, and rN (Set N = 1 reduced to the case of a single impurity). The Green’s function in real space47 can be formulated by

| 7 |

where with M the numbers of unit cells, G0(k, E) the unperturbed Green’s function in reciprocal space and the many-impurity 2N × 2N T-matrix is determined by

| 8 |

where

| 9 |

| 10 |

Here, Vi = Vsτ3 + Vmτ0, with Vs the scalar potential, Vm the magnetic scattering potential. Vm = 0 for non-magnetic impurities. Then we can obtain the spin-summed LDOS given by

| 11 |

where τi is the Pauli matrix spanning Nambu space. Referring to Eqs. (2) and (3), we can get the simulated PR-QPI images as shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–4 and 8–11. For the case of multiple impurities, we randomly assign the impurities to the lattice sites in our simulated FOV either with the identical scattering potential or with the randomly distributed scattering potentials within 100 meV.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge useful discussions with Tetsuo Hanaguri and Dunghai Lee. We thank Zhen Ke for the programming of lattice correlation by using the Lawler–Fujita algorithm. The work in China was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (grant number: 2016YFA0300401), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) with the project numbers 11534005, 11574134. Work at Brookhaven was supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Division of Materials Science and Engineering, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), through Contract No. de-sc0012704. R.D.Z. and J.S.W. were supported by the Center for Emergent Superconductivity, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by BES.

Author contributions

The low-temperature STM/STS measurements and analysis were performed by Q.G., S.Y.W., Z.Y.D., H.Y. and H.H.W. The samples were grown by G.G., R.D.Z. and J.S.W. Q.G., H.Y. and H.H.W. contributed to the writing of the paper. The theoretical calculation was done by Q.T., Q.G. and Q.H.W., H.Y. and H.H.W. are responsible for the final text. H.H.W. coordinated the whole work. All authors have discussed the results and the interpretations.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qiangqiang Gu, Siyuan Wan, Qingkun Tang.

Contributor Information

Huan Yang, Email: huanyang@nju.edu.cn.

Qiang-Hua Wang, Email: qhwang@nju.edu.cn.

Hai-Hu Wen, Email: hhwen@nju.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-09340-5.

References

- 1.Shen ZX, et al. Anomalously large gap anisotropy in the a-b plane of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993;70:1553–1556. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding H, et al. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy study of the superconducting gap anisotropy in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;54:9678–9681. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.r9678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutherland M, et al. Thermal conductivity across the phase diagram of cuprates: low-energy quasiparticles and doping dependence of the superconducting gap. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;67:174520. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.174520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moler KA, Sisson DL, Urbach JS, Beasley MR, Kapitulnik A. Specific heat of YBa2Cu3O7−δ. Phys. Rev. B. 1997;55:3954–3965. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.55.3954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen HH, et al. Electronic specific heat and low-energy quasiparticle excitations in the superconducting state of La2−xSrxCuO4 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B. 2004;70:214505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.70.214505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renner C, Fischer O. Vacuum tunneling spectroscopy and asymmetric density of states of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. B. 1995;51:9208–9218. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.51.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan SH, et al. Microscopic electronic inhomogeneity in the high-Tc superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nature. 2001;413:282–285. doi: 10.1038/35095012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman JE, et al. Imaging quasiparticle interference in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Science. 2002;297:1148–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.1072640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong HF, et al. Neutron scattering from magnetic excitations in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nature. 1999;398:588–591. doi: 10.1038/19255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai PC, Mook HA, Dogan F. Incommensurate magnetic fluctuations in YBa2Cu3O6.6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;80:1738–1741. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacuto A, et al. Nodes of the superconducting gap probed by electronic Raman scattering in HgBa2CaCu2O6+δ single crystals. Europhys. Lett. 1997;39:207–212. doi: 10.1209/epl/i1997-00336-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McElroy K, et al. Relating atomic-scale electronic phenomena to wave-like quasiparticle states in superconducting Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nature. 2003;422:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature01496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohsaka Y, et al. How Cooper pairs vanish approaching the Mott insulator in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nature. 2008;454:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature07243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ideta SI, et al. Energy scale directly related to superconductivity in high-Tc cuprates: Universality from the temperature-dependent angle-resolved photoemission of Bi2Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+δ. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:104515. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.104515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanaguri T, et al. Coherence factors in a high-Tc cuprate probed by quasi-particle scattering off vortices. Science. 2009;323:923–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1166138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirtley JR, et al. Symmetry of the order parameter in the high-Tc superconductor YBa2Cu3O7−δ. Nature. 1995;373:225–228. doi: 10.1038/373225a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuei CC, et al. Pairing symmetry in single-layer tetragonal Tl2Ba2CuOβ+δ superconductors. Science. 1996;271:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuei CC, Kirtley JR. Pairing symmetry in cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000;72:969–1016. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.72.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chi, S. et al. Extracting phase information about the superconducting order parameter from defect bound states. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1710.09088 (2017).

- 20.Chi, S. et al. Determination of the superconducting order parameter from defect bound state quasiparticle interference. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1710.09089 (2017).

- 21.Ménard GC, et al. Coherent long-range magnetic bound states in a superconductor. Nat. Phys. 2015;11:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nphys3508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McElroy K, et al. Coincidence of checkerboard charge order and antinodal state decoherence in strongly underdoped superconducting Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:197005. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.197005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McElroy K, et al. Atomic-scale sources and mechanism of nanoscale electronic disorder in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Science. 2005;309:1048–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.1113095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dynes RC, Narayanamurti V, Garno JP. Direct measurement of quasiparticle-lifetime broadening in a strong-coupled superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978;41:1509–1512. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.41.1509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawler MJ, et al. Intra-unit-cell electronic nematicity of the high-Tc copper-oxide pseudogap states. Nature. 2010;466:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature09169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang KY, Rice TM, Zhang FC. Phenomenological theory of the pseudogap state. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:174501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.174501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschfeld PJ, Altenfeld D, Eremin I, Mazin II. Robust determination of the superconducting gap sign structure via quasiparticle interference. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:184513. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.184513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprau PO, et al. Discovery of orbital-selective Cooper pairing in FeSe. Science. 2017;357:75–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du ZY, et al. Sign reversal of the order parameter in (Li1-xFex)OHFe1-yZnySe. Nat. Phys. 2018;14:134–139. doi: 10.1038/nphys4299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu QQ, et al. Sign reversal superconducting gaps revealed by phase referenced quasi-particle interference of impurity induced bound states in (Li1−xFex)OHFe1−yZnySe. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;98:134503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.134503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang QH, Lee DH. Quasiparticle scattering interference in high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;67:020511(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.020511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang D, Ting CS. Energy-dependent modulations in the local density of states of the cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;67:100506(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.100506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capriotti L, Scalapino DJ, Sedgewick RD. Wave-vector power spectrum of the local tunneling density of states: Ripples in a d-wave sea. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;68:014508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.68.014508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereg-Barnea T, Franz M. Theory of quasiparticle interference patterns in the pseudogap phase of the cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;68:180506(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.68.180506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu L, Atkinson WA, Hirschfeld PJ. Power spectrum of many impurities in a d-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B. 2004;69:060503(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.69.060503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunner TS, Chen W, Andersen BM, Melikyan A, Hirschfeld PJ. Fourier transform spectroscopy of d-wave quasiparticles in the presence of atomic scale pairing disorder. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:104511. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.104511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maltseva M, Coleman P. Model for nodal quasiparticle scattering in a disordered vortex lattice. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:144514. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.144514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan Y, Lü HD, Lu HY, Wang QH. Impurity resonance states in electron-doped high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2008;77:064515. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.064515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pushp A, et al. Extending universal nodal excitations optimizes superconductivity in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Science. 2009;324:1689–1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1174338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brun C, et al. Remarkable effects of disorder on superconductivity of single atomic layers of lead on silicon. Nat. Phys. 2014;10:444–450. doi: 10.1038/nphys2937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreisel A, et al. Interpretation of scanning tunneling quasiparticle interference and impurity states in cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;114:217002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.217002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martiny JHJ, Kreisel A, Hirschfeld PJ, Andersen BM. Robustness of a quasiparticle interference test for sign-changing gaps in multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:184507. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.184507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balatsky AV, Vekhter I, Zhu JX. Impurity-induced states in conventional and unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2006;78:373–433. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.78.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allgeier C, Schilling JS. Magnetic susceptibility in the normal state: a tool to optimize Tc within a given superconducting oxide system. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;48:9747–9753. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gu GD, Takamuka K, Koshizuka N, Tanaka S. Large single crystal Bi-2212 along the c-axis prepared by floating zone method. J. Cryst. Growth. 1993;130:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0022-0248(93)90872-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guarise M, et al. Anisotropic softening of magnetic excitations along the nodal direction in superconducting cuprates. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5760. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiete GA. Colloquium: theory of quantum corrals and quantum mirages. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000;75:933–948. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.75.933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.