Abstract

Background.

Contrast ultrasound-mediated gene delivery (CUMGD) is a promising approach for enhancing gene therapy that relies on microbubble cavitation to augment cDNA transfection. Our aims were to determine optimal conditions for charge-coupling cDNA to microbubbles, and to evaluate the advantages of surface loading for gene transfection in muscle and liver.

Methods.

Charge coupling of fluorescently-labeled cDNA to either neutral (MBN) or cationic (MB+) microbubbles in low to high ionic conditions (0.3 to 1.8% NaCl) was assessed by flow cytometry. MB aggregation from cDNA coupling at was determined by electrozone sensing. Tissue transfection of luciferase in murine hindlimb skeletal muscle and liver were made by CUMGD with MBN or MB+ combined with sub-saturated, saturated, or super-saturated cDNA concentrations (2.5, 50, and 200 μg/108 MB).

Results:

Charge-coupling of cDNA was detected for MB+ but not MBN. Coupling occurred over almost the entire range of ionic conditions with a peak at 1.2% NaCl, although electrostatic interference occurred at >1.5% NaCl. DNA-mediated aggregation of MB+ was observed at ≤0.6% NaCl and reduction the ability to produce inertial cavitation. Transfection with CUMGD in muscle and liver was low for both MBs at sub-saturation concentrations. In muscle higher cDNA concentrations produced a 10-fold higher degree of transfection with MB+ which was approximately 5-fold higher (p<0.05) than that for MBN. There was no effect of DNA supersaturation. The same pattern was seen for liver except that supersaturation further increased transfection with MBN equal to that of MB+

Conclusions:

Efficient charge coupling of cDNA to cationic but not neutral MBs occurs over a relatively wide range of ionic conditions without aggregation. Transfection with CUMGD is much more efficient with charge coupling of cDNA to MBs and is not affected by supersaturation except in the liver which is specialized for macromolecular and cDNA uptake.

Keywords: Contrast ultrasound, Gene therapy, Microbubbles, Transfection

Gene-based therapies offer promise for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and lipid disorders. Enthusiasm for this approach has been tempered by the numerous obstacles to its success. One of the major barriers to gene therapy is the ability to effectively and safely transfer genetic material into the target tissue.1 Ultrasound-mediated cavitation of encapsulated microbubbles (MB) and other acoustically active particles has increasingly been used in preclinical research to augment cardiovascular delivery of plasmid complementary DNA (cDNA) and therapeutic non-coding small RNAs.2,3 This method has been shown to be most effective when the therapeutic genetic material is loaded onto the acoustically-active particles.4,5 Charge-conjugation of cDNA which is a polyanion to the surface of cationic lipid MB represents a simple and effective approach for contrast ultrasound-mediated gene delivery (CUMGD).5–7

The purpose of this study was to address important knowledge gaps with regards to the optimization of CUMGD. First, we characterized optimal ionic aqueous environment for charge coupling of plasmid cDNA to cationic MBs. We then compared tissue transfection of a reporter gene with CUMGD using either neutral MBs with ambient (non-coupled) cDNA, or charge-coupled cDNA on cationic MBs, with and without excess ambient cDNA. This aim was designed to determine whether the presence of excess ambient cDNA either negates the advantage of surface conjugation or is wasteful and contributes little to transfection efficiency. We also compared the relative benefit of charge-coupling cDNA to the MB for the peripheral vasculature and the liver. These studies were performed because liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, which include Kupffer cells, represent a specialized endothelial cell type characterized by fenestrae, enhanced clathrin-dependent colloid uptake, and enhanced cDNA and polyanionic uptake capability, all of which have the potential to partially negate the influence of charge conjugation and CUMGD.8,9

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbubbles

Near-neutral charge microbubbles (MBN) were prepared by sonication of decafluorobutane saturated aqueous suspension of distearoylphosphatidylcholine (2 mg/ml) and polyoxyethylene-40-stearate (1 mg/ml). Cationic bubbles (MB+) were prepared by the addition of distearoyl-trimmethylammonium propane (0.4 mg/ml) to the suspension. The mean diameter and concentration of microbubbles were determined by using Coulter counter (Multisizer III, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California). Electric surface potential (zeta potential) for cationic and neutral microbubbles was determined by measurement of their electrophoretic mobility (ZetaPALS, Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, New York) in 1 mmol/l KCl at pH 7.4.

Plasmid-Microbubble Coupling

Coupling efficiency of cDNA to the microbubble surface under variable ionic solution environments was performed by flow cytometry. Plasmid cDNA (pGL4.13, Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) was combined with either MBN or MB+ at a previously-described super-saturation ratio of 20 μg of cDNA per 108 microbubbles in a NaCL solution at concentrations of 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, 1.5 and 1.8%.5 Microbubbles were washed by flotation centrifugation and cDNA was labeled with SYBR-Gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Fluorescent histograms of control and cDNA-incubated microbubbles were assessed in duplicate by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences) at 488 nm excitation and data were expressed as intensity geometric mean. To ensure that cDNA was at saturating concentrations, FACS was also performed after combining MB+ in 1.2% Na Cl with cDNA at concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 4, 10, 20, and 40 μg per 108 MB.

Microbubble Aggregation

Microbubble aggregation which can occur by surface coupling of cDNA was quantified by particle size on electrozone counting of MB+ alone or after conjugation with plasmid cDNA (20 μg per 108 microbubbles) in the various concentration NaCL solutions described above. Data were quantified in duplicate by the percentage of particle events greater than 5 μm in diameter.

Effects of cDNA Conjugation on Microbubble Acoustic Response

Frequency-amplitude histograms were obtained from cationic microbubbles (1×107 mL−1) pre-incubated with plasmid cDNA at 0.3, 0.9, 1.2 or 1.8 % NaCl. Ultrasound (1 MHz) exposure was performed in a flow phantom with a 50 cycle pulse was produced by a single-element transducer (Olympus NDT, Sonic Concepts Inc.) at a peak negative acoustic pressure of 1 MPa. Cavitation signals were received by a broad-band (10 KHz to 20 MHz) hydrophone interfaced with a receiver (RAM-5000, Ritec) and an oscilloscope (44MXi-A, LeCroy), and were digitized at 100 MHz sampling frequency. Data analysis was performed with Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and cavitation was characterized by the broadband signals between the harmonic peaks.

Animals

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health & Science University. Transfection of a firefly luciferase reporter gene was studied in studied 42 wild-type C57Bl/6 mice age 8–12 weeks. Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (1.0–1.5%) and a catheter was placed in a jugular vein for administration of microbubbles. Animals were recovered for in vivo optical imaging of transfection 3 days later.

In Vivo Transfection Protocols

For CUMGD, animals received a single intravenous injection 2.5, 50 or 200 μg of pGL4.13 luciferase plasmid pre-mixed for 5 min with 2×108 of either MB+ or MBN suspended in approximately 100 μL of 0.9% NaCl (n=7 for each of the six conditions). These concentrations were selected to produce subsaturation, saturation, and supersaturation conditions for charge coupling. Microbubbles were infused intravenously over 1 minute. Two separate phased-array ultrasound probes coupled to two separate ultrasound systems (Sonos 7500, Philips Ultrasound, Andover, MA) were fixed in place and used to simultaneously expose both the liver and proximal hindlimb adductor muscles using aqueous ultrasound coupling gel as a standoff. Ultrasound exposure was performed during microbubble injection and for an additional 9 minutes using harmonic power Doppler mode at 1.6 MHz, a pulsing interval of 5 s, a pulse repetition frequency of 9.3 kHz, and a system setting MI of 1.3. The acoustic focus was placed at the level of the tissue of interest. According to needle hydrophone measurements, these settings produce a beam elevational profile of ≈6 mm when defined by half-maximal (0.8 MPa) full-width.10

Detection of Gene Transfection

In vivo assessment of transfection was determined by optical imaging of luciferase activity 3 days after CUMGD. D-luciferin (0.15 mg/g) was administered by intraperitoneal injection. Animals were anesthetized with inhaled isofluorane and placed in an optical imaging system (IVIS Spectrum, Caliper Life Sciences). Bioluminescent activity was measured 10 min after luciferin injection with an open emission filter and medium binning. Light activity from regions of interest placed over each proximal hindlimb was quantified by total photon flux (p/s).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between conditions for gene-loading and aggregation, or for differences in transfection efficiency on optical imaging according to pGL4.13 concentration were made using a Kruskall-Wallis test. A Mann-Whitney test was performed for any post-hoc differences between two categories and for comparing MB type for transfection efficiency by optical imaging. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Microbubble Characteristics and Gene Loading

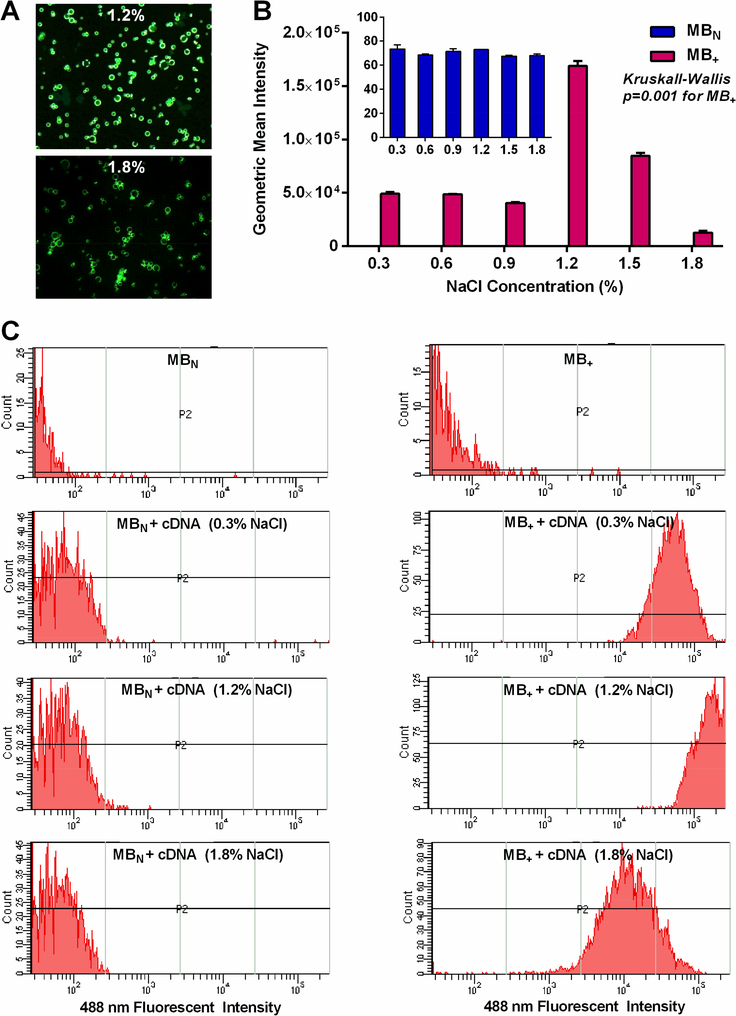

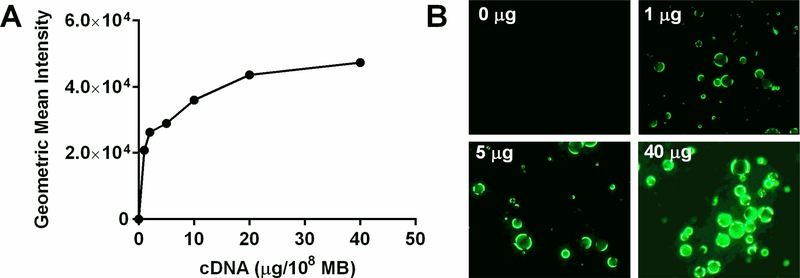

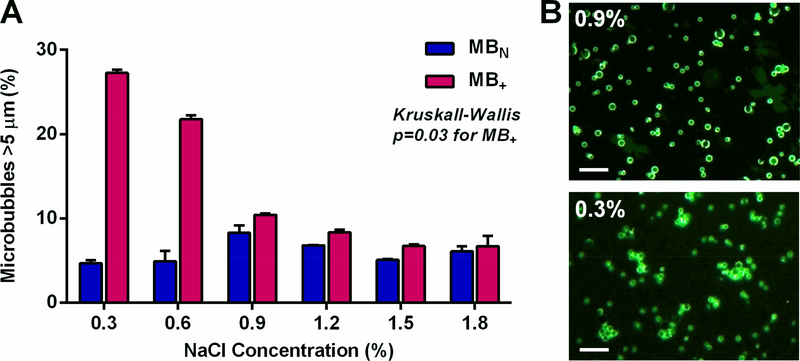

The mean diameter was similar for MB+ and MBN (2.95±0.13 vs 2.68±0.04 μm, p=0.07). Zeta potential measured in 1 mM KCl was significantly positive and substantial greater for MB+ than for MBN (+38.6±5.1 vs −2.5±1.3 mV, p<0.0001). Under conditions where there was known saturating concentrations of plasmid cDNA,5 flow cytometry detected little fluorescent cDNA coupled to the surface of MBN regardless of the ionic conditions (Figure 1). Charge coupling of plasmid cDNA to MB+ was two to three orders of magnitude greater than to MBN under all ionic conditions. The greatest degree of charge coupling of cDNA to MB+ tended to be at 1.2 % NaCl and substantial interference with gene conjugation was seen at the highest NaCl concentration (1.8%). Dose response cDNA coupling to MB+ in 1.2 % NaCl demonstrated that these experiments were performed at the saturating concentration point (Figure 2). Because of the potential for DNA-mediated MB aggregation under low ionic conditions, electrozone counting was used to assess the proportion of particles that were >5 μm in diameter. Prior to cDNA incubation, the percent were >5 μm was similar for MB+ and MBN (7.0±0.8 vs 6.9±0.8 %, p=0.82). Only MB+ demonstrated a significant (Kruskall-Wallis p=0.03) increase in events with low ionic conditions indicating aggregation at NaCl of 0.6% and lower (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

(A) Fluorescent microscopy illustrating differences in the degree of SYBR Gold-labeled cDNA charge coupled to MB+ in a 1.2 or 1.8% NaCl solution. (B) Mean (±SEM) values for MB fluorescent intensity on flow cytometry which was used to quantify coupling of labeled plasmid cDNA to the MB surface (20 μg per 108 MB). Data for MBN are re-displayed on the graph insert to illustrate these values which were 3 orders of magnitude lower than for MB+. (C) Histograms of illustrating flow cytometry data of MBN and MB+ fluorescent intensity for microbubbles alone or after combining with labeled cDNA in various NaCL concentration solutions.

Figure 2.

(A) Mean fluorescent intensity on flow cytometry during dose-titration for coupling of SYBR Gold-labeled cDNA to MB+ in 1.2% NaCl. (B) Fluorescent microscopy illustrating differences in the degree of SYBR Gold-labeled cDNA charge coupled to MB+.

Figure 3.

Ionic environment and DNA-mediated microbubble aggregation assessed by: (A) mean (±SEM) percent of electrozone counting events that were >5 μm in diameter after combining MBN and MB+ with cDNA (20 mg per 108 MB) in various concentrations of NaCl; and (B) Fluorescent microscopy illustrating differences in aggregation of MB+ in 0.9% and 0.3% NaCl after combining with cDNA.

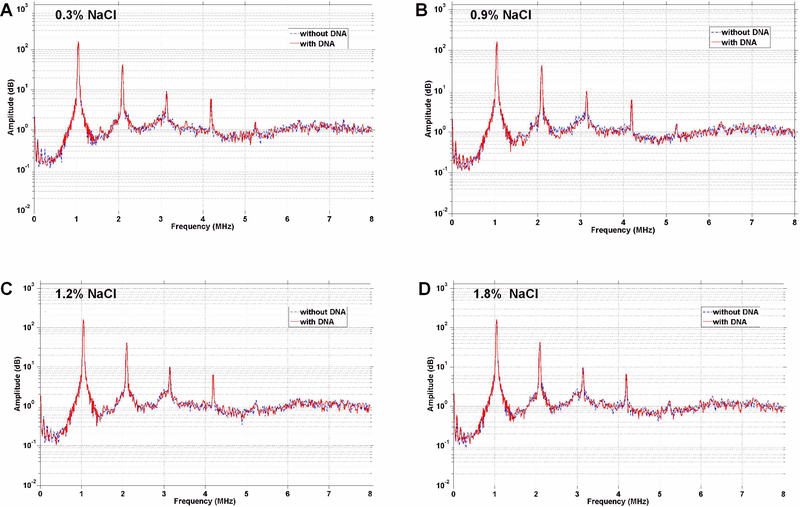

Microbubble Acoustic Response

Frequency-amplitude histograms during ultrasound exposure (1 MHz, 1 MPa) were used to examine how cDNA loading or aggregation influences MB acoustic response (Figure 4). Experimental conditions were tested only with MB+ since there was very little cDNA loading on MBN. Incubation at the various concentrations of NaCl which produces different degrees of cDNA coupling to MB+ resulted in no significant change in acoustic response compared to microbubbles without gene. The amplitude and frequency of the harmonic peaks and the “between peak” broadband signal were identical, indicating similar non-linear response to both stable and inertial cavitation irrespective of gene-loading. Light microscopy illustrated minimal resistance of MB+ to acoustic destruction when they were in aggregate form at low ionic strength (Supplemental Videos).

Figure 4.

Acoustic signal response from microbubbles by passive cavitation detection displayed as amplitude-frequency plots for experiments performed with cationic microbubbles with (dashed blue lines) or without (solid red lines) cDNA in NaCl at concentrations of (A) 0.3%, (B) 0.9%, (C) 1.2%, or (D) 1.8%.

In vivo Transfection

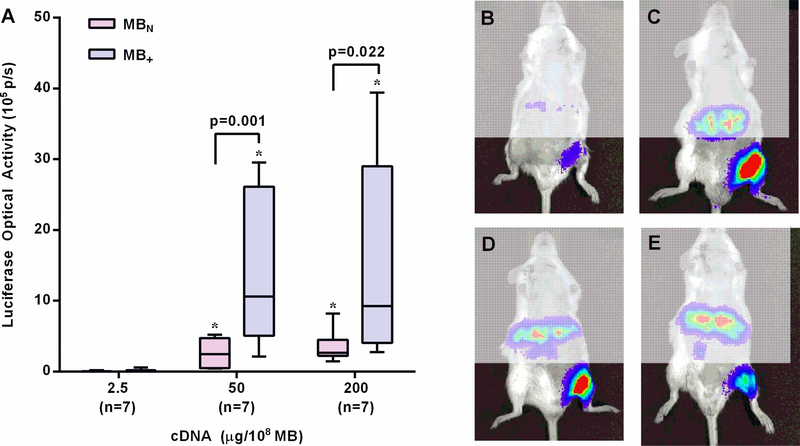

Tissue transfection of plasmid luciferase reporter by was assessed by in vivo optical imaging three days after CUMGD. Control conditions of (i) plasmid administration with ultrasound but without microbubbles, or (ii) plasmid administration with MB+ but without ultrasound were not performed because we have previously reported that these approaches do not produce any detectable luciferase transfection.5 In skeletal muscle, luciferase activity after CUMGD with both MB+ and MBN was low when microbubbles were combined with 2.5 μg per 108 MB (Figure 5). There was significantly greater transfection with both MB agents when combined with the higher concentrations of plasmid (50 and 200 μg/108). At these higher concentrations, transfection was significantly higher with the MB+. There was no further increase in transfection when increasing from 50 to 200 μg/108.

Figure 5.

(A) Bar-whisker plots (median and 10–90 percentile) of luciferase activity from the proximal hindlimb by optical imaging 3 days after CUMGD transfection of pGL4.13. *p<0.05 versus 2.5 μg/108 MB). In vivo optical imaging illustrating transfection efficiency of the ultrasound-exposed leg using MB+ with pGL4.13 concentrations of (B) 2.5, (C) 50, or (D) 200 μg/108 MB; or using (E) MBN with 200 μg/108.

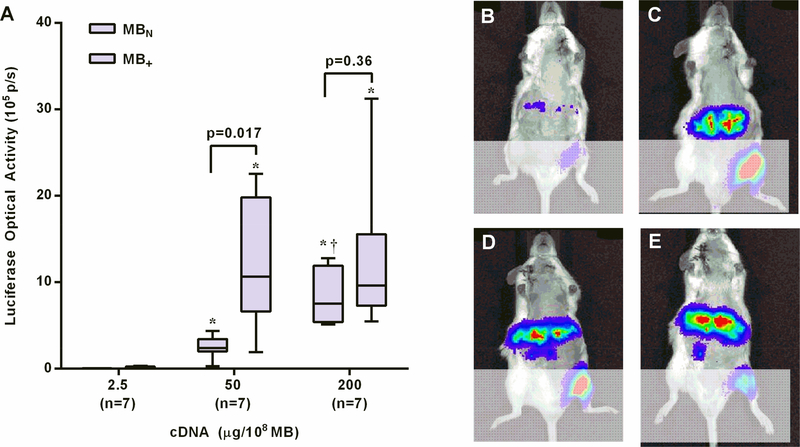

Similar to skeletal muscle, liver luciferase activity after CUMGD with both MB+ and MBN was low when combined with 2.5 μg per 108 MB (Figure 6). For MB+ luciferase activity was much greater when combined with the higher concentrations of plasmid (50 and 200 μg/108) with no difference between the two highest doses. For MBN the pattern of transfection at higher plasmid doses was slightly different than in muscle in that a sequential increase in luciferase activity was seen between 50 and 200 μg/108, and activity was not different between MB+ and MBN at 200 μg/108.

Figure 6.

(A) Bar-whisker plots (median and 10–90 percentile) of luciferase activity from the liver by optical imaging 3 days after CUMGD transfection with pGL4.13 *p<0.05 versus 2.5 μg/108 MB). In vivo optical imaging illustrating transfection efficiency of the liver using MB+ with pGL4.13 concentrations of (B) 2.5, (C) 50, or (D) 200 μg/108 MB; or using (E) MBN with 200 μg/108.

DISCUSSION

The use of CUMGD to enhance non-viral gene vector gene therapy has been gaining popularity steadily. Since our initial description that efficient CUMGD transfection can be achieved using cationic microbubbles to which cDNA is charge-coupled,5 a wide variety of research studies have used this approach for delivery of a wide variety of therapeutic genes for cardiovascular applications including those that modulate angiogenesis, cell survival, inflammation, protease activity, and scavenger receptors.11–16 It has been demonstrated that using cationic MBs for charge-coupling cDNA increases transfection efficiency with CUMGD in muscle and tumors,7,17 however there have been unanswered questions with regards to optimization of the technique.

One unknown addressed by the current study involves the ideal conditions for plasmid loading of cDNA. It has consistently been shown that cDNA payload is very small for neutral compared to cationic MBs.6,7 By comparing dose-titration results of the current study to those in other where cationic lipid MB zeta potential was measured,7 it can be argued that plasmid cDNA coupling increases with the more positive MB surface charge. This notion is supported by the increase in cDNA coupling to cationic MBs that is achieved by increasing positive charge through surface conjugation of the cationic polymer polyethylenimine.18 Charge-coupling is also influenced by electrostatic environment which may have also influenced differences that have been found in gene-loading capacity. Accordingly, we investigated the influence of the ionic environment. Our data suggest that plasmid coupling to MB+ is relatively efficient over a broad range of ionic concentrations. However, there was a notable peak of coupling efficiency at 1.2% NaCl, beyond which there was probable electrostatic interference with charge coupling which became severe at 1.8%.19 The reason for less coupling of cDNA to MB+ at NaCl concentrations <1.2% is less clear but likely relates to the cDNA condensation or geometric changes that occurs when electrostatic dispersion forces are low.20

Self-assembly cationic liposomes are commonly used for accelerating transfer of DNA into eukaryotic cells, a process known as “lipofection”. Aggregation of these liposomes is known to occur particularly when there is a low DNA to lipid ratio, but is also predicted to increase in low ionic strength medium due to lack of electrostatic inhibition.21,22 Aggregation of MBs, which are an order of magnitude larger than liposomes, would result in complexes that are sufficiently large that they: (i) do not transit to the systemic circulation after intravenous injection, and (ii) pose a safety risk. Our data indicate the presence of aggregates large enough to lodge in the pulmonary (or systemic) microcirculation when DNA was coupled to MB+ at 0.6 % NaCl and below.23 Because cDNA did not associate with MBN, ionic strength did not influence the size of these microbubbles.

There have been many postulated mechanisms by which CUMGD augments delivery of cDNA such as plasmids or other types of genetic material such as RNA into cells. Postulated mechanisms have ranged passive uptake through microporation, active uptake through clathrin- or caveolin-dependent mechanisms, or increased trafficking to the nucleus.5,24–27 The tissue-specific differences in luciferase transfection efficiency for MB+ and MBN, and effects of excess ambient plasmid would suggest that there is more than one mechanism. For liver and muscle, transfection efficiency using plasmid:MB ratio just over MB+ saturation was much greater for MB+ than MBN. This finding suggests that high local concentration of cDNA at the site of cavitation through charge-coupling to MBs is important for CUMGD, and explains why further increases in ambient cDNA throughout the blood volume did not further enhance transfection efficiency. These findings suggest microporation or ballistic amplification of delivery as an important mechanistic component, although local effects on active endocytosis are also possible.

The ability to achieve high hepatic but not muscle transfection with excess non-coupled cDNA during CUMGD with MBN was an intriguing finding. Others have also found that liver CUMGD with near neutral MBs and a large excess of plasmid cDNA (≈115 μg per 108 MBs) can approximate that achieved with cationic MBs.28 This phenomenon indicates that (i) protection of plasmid from endonucleases by MB surface coupling is not a major factor, and (ii) ultrasound cavitation probably increases activity of the specialized liver sinusoidal endothelial cells that have heightened ability to clear native and foreign macromolecules, including DNA, from the blood using active uptake mechanisms. The ability of MB cavitation to increase intracellular calcium and uptake of dextrans is probably a good indication that CUMGD can enhance this natural process.25,29 The implications of our data in aggregate are that CUMGD in muscle is much more effective when cDNA is directly conjugated to cationic microbubbles; whereas in organs that have enhanced uptake capability, such as the liver, excess ambient cDNA can be an effective alternative to charge-coupling onto microbubbles.

There are several limitations of the current study. Transfection efficiency at the high plasmid doses varied widely. We believe this variation is because: (i) CUMGD is highly influenced by the blood flow at the time of delivery which can vary widely between animals, and (ii) d-luciferin availability 3 days later is also influenced by blood flow. Transfection efficiency with the luciferase reporter plasmid was assessed using 0.9% NaCl rather than slightly higher ionic concentrations that produced slightly greater coupling density. This concentration was chosen due to the simplicity of using normal saline or PBS as a medium. We also did not investigate whether transfection was greater with extreme excess of free pGL4.13. As mentioned in the Results, certain control conditions were not tested because they have previously been shown not to produce any detectable transfection. We also tested transfection efficiency only at the peak transfection time point (3 days).

In summary, we have demonstrated that there is a relatively wide range of ionic concentrations from 0.6% to 1.5% NaCl that plasmid cDNA can be efficiently coupled to cationic MBs without aggregation. Transfection efficiency is markedly amplified by charge coupling cDNA to the surface of MBs, although this advantage can be negated by excess ambient cDNA for specific organs that are tasked with macromolecular uptake such as the liver.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lindner is supported by grants R01-HL078610 and R01-HL111969 from the NIH, grant 14NSBRI1–0025 from the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NASA), and a research award from GE Healthcare. Dr. Wu is supported by grant T32-HL-94294–5 from the NIH. Dr. Moccetti is funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

There are no disclosures for this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kay MA. State-of-the-art gene-based therapies: The road ahead. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2011;12:316–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unger E, Porter T, Lindner J, Grayburn P. Cardiovascular drug delivery with ultrasound and microbubbles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;72:110–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton JT, Haworth KJ, Pyne-Geithman G, Holland CK. Ultrasound-mediated drug delivery for cardiovascular disease. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2013;10:573–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frenkel PA, Chen S, Thai T, Shohet RV, Grayburn PA. DNA-loaded albumin microbubbles enhance ultrasound-mediated transfection in vitro. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:817–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen JP, French BA, Klibanov AL, Kaul S, Lindner JR. Targeted tissue transfection with ultrasound destruction of plasmid-bearing cationic microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1759–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie A, Belcik T, Qi Y, Morgan TK, Champaneri SA, Taylor S, et al. Ultrasound-mediated vascular gene transfection by cavitation of endothelial-targeted cationic microbubbles. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:1253–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang DS, Panje C, Pysz MA, Paulmurugan R, Rosenberg J, Gambhir SS, et al. Cationic versus neutral microbubbles for ultrasound-mediated gene delivery in cancer. Radiology. 2012;264:721–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elvevold K, Smedsrod B, Martinez I. The liver sinusoidal endothelial cell: A cell type of controversial and confusing identity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hisazumi J, Kobayashi N, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. Significant role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in hepatic uptake and degradation of naked plasmid DNA after intravenous injection. Pharmaceutical research. 2004;21:1223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belcik JT, Mott BH, Xie A, Zhao Y, Kim S, Lindner NJ, et al. Augmentation of limb perfusion and reversal of tissue ischemia produced by ultrasound-mediated microbubble cavitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobulnik J, Kuliszewski MA, Stewart DJ, Lindner JR, Leong-Poi H. Comparison of gene delivery techniques for therapeutic angiogenesis ultrasound-mediated destruction of carrier microbubbles versus direct intramuscular injection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1735–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuliszewski MA, Kobulnik J, Lindner JR, Stewart DJ, Leong-Poi H. Vascular gene transfer of sdf-1 promotes endothelial progenitor cell engraftment and enhances angiogenesis in ischemic muscle. Mol Ther. 2011;19:895–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korpanty G, Chen S, Shohet RV, Ding J, Yang B, Frenkel PA, et al. Targeting of vegf-mediated angiogenesis to rat myocardium using ultrasonic destruction of microbubbles. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan P, Chen KJ, Wu J, Sun L, Sung HW, Weisel RD, et al. The use of mmp2 antibody-conjugated cationic microbubble to target the ischemic myocardium, enhance timp3 gene transfection and improve cardiac function. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1063–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, Zhu J, Huang Y, Guo W, Rui M, Xu Y, et al. Hypolipidemic effect of srbi gene delivery by combining cationic liposomal microbubbles and ultrasound in hypercholesterolemic rats. Molecular medicine reports. 2013;7:1965–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L, Huang CW, Wu J, Chen KJ, Li SH, Weisel RD, et al. The use of cationic microbubbles to improve ultrasound-targeted gene delivery to the ischemic myocardium. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2107–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panje CM, Wang DS, Pysz MA, Paulmurugan R, Ren Y, Tranquart F, et al. Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery with cationic versus neutral microbubbles: Effect of DNA and microbubble dose on in vivo transfection efficiency. Theranostics. 2012;2:1078–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin Q, Wang Z, Yan F, Deng Z, Ni F, Wu J, et al. A novel cationic microbubble coated with stearic acid-modified polyethylenimine to enhance DNA loading and gene delivery by ultrasound. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perales JC, Grossmann GA, Molas M, Liu G, Ferkol T, Harpst J, et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of DNA complexes capable of targeting genes to hepatocytes via the asialoglycoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7398–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS. Visualization of supercoiled DNA with atomic force microscopy in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:496–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eastman SJ, Siegel C, Tousignant J, Smith AE, Cheng SH, Scheule RK. Biophysical characterization of cationic lipid: DNA complexes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1997;1325:41–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiethoff CM, Gill ML, Koe GS, Koe JG, Middaugh CR. The structural organization of cationic lipid-DNA complexes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44980–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindner JR, Song J, Jayaweera AR, Sklenar J, Kaul S. Microvascular rheology of definity microbubbles after intra-arterial and intravenous administration. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvshani-Eshet M, Baruch L, Kesselman E, Shimoni E, Machluf M. Therapeutic ultrasound-mediated DNA to cell and nucleus: Bioeffects revealed by confocal and atomic force microscopy. Gene Ther. 2006;13:163–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meijering BD, Juffermans LJ, van Wamel A, Henning RH, Zuhorn IS, Emmer M, et al. Ultrasound and microbubble-targeted delivery of macromolecules is regulated by induction of endocytosis and pore formation. Circ Res. 2009;104:679–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehier-Humbert S, Yan F, Frinking P, Schneider M, Guy RH, Bettinger T. Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery: Influence of contrast agent on transfection. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:652–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taniyama Y, Tachibana K, Hiraoka K, Namba T, Yamasaki K, Hashiya N, et al. Local delivery of plasmid DNA into rat carotid artery using ultrasound. Circulation. 2002;105:1233–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun RR, Noble ML, Sun SS, Song S, Miao CH. Development of therapeutic microbubbles for enhancing ultrasound-mediated gene delivery. J Control Release. 2014;182:111–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juffermans LJ, van Dijk A, Jongenelen CA, Drukarch B, Reijerkerk A, de Vries HE, et al. Ultrasound and microbubble-induced intra- and intercellular bioeffects in primary endothelial cells. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:1917–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.