Abstract

Purpose:

Diet and healthy weight are established means of reducing cancer incidence and mortality. However, the impact of diet modifications on the tumor microenvironment (TME) and antitumor immunity are not well-defined. Immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are associated with poor clinical outcomes and are potentially modifiable through dietary interventions. We tested the hypothesis that dietary protein restriction modifies macrophage function toward antitumor phenotypes.

Experimental design:

Macrophage functional status under different tissue culture conditions and in vivo was assessed by Western blot, immunofluorescence, qRT-PCR, and cytokine array analyses. Tumor growth in the context of protein or amino acid (AA)-restriction and immunotherapy, namely a survivin peptide-based vaccine or a PD-1 inhibitor, was examined in animal models of prostate (RP-B6Myc) and renal (RENCA) cell carcinoma. All tests were two-sided.

Results:

Protein or AA-restricted macrophages exhibited enhanced tumoricidal, pro-inflammatory phenotypes, and in two syngeneic tumor models, protein or AA-restricted diets elicited reduced TAM infiltration, tumor growth, and increased response to immunotherapies. Further, we identified a distinct molecular mechanism by which AA-restriction reprograms macrophage function via a ROS/mTOR centric cascade.

Conclusions:

Dietary protein restriction alters TAM activity and enhances the tumoricidal capacity of this critical innate immune cell type, providing the rationale for clinical testing of this supportive tool in patients receiving cancer immunotherapies.

Keywords: Macrophage polarization, protein and methionine restriction, immunomodulation

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have linked diet to cancer incidence and mortality (1–3). While no single dietary factor is the sole contributor to cancer, high consumption of animal fat (4), dairy products (5), and red meat have been linked to increased incidence and cancer-related mortality (3). These foods also contribute to higher levels of circulating insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, a potent mutagen and mTOR pathway driver linked to tumor progression (2). Conversely, high consumption of vegetables, legumes (6), and fish (7) are linked to reduced cancer incidence, progression and mortality (3). Many of the modifiable risk factors tie into the Akt/mTOR and insulin/IGF-1 axes, and impact immune infiltrates into the TME (8).

Macrophage infiltration is pivotal for tumor immune evasion, angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis. Macrophages assume different functional states, reflecting a continuum of immune activating (i.e. M1-like) to immune suppressive (i.e. M2-like) phenotypes, largely impacted by stromal- or tumor-derived factors released systemically or locally within the TME. The transition from one functional state to another has been termed “polarization” due to the unique plasticity of the same macrophage population to adopt and respond to the inflammatory milieu. Macrophage polarization and function in turn are impacted by various signaling pathways and transcription factors. Activation of the nutrient sensing mTOR pathway drives macrophage polarization towards a pro-tumor M2 subtype, which has been linked to tumor progression and immune suppressive activity (9–11). Conversely, inhibition of the mTOR pathway results in a shift towards an antitumor M1 subtype (10).

In response to nutrients and growth factors, the mTOR pathway controls pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokine expression in monocyte-derived macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells (11) (12). Direct inhibition of mTOR has an impact on macrophage cytokine production at both the transcriptional and translational levels (13), and in selective induction of death of the M2 subtype, a shift towards a M1 phenotype, and impairment of myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) development (10, 12).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that dietary protein/amino acid (AA) restriction redirects macrophage polarization and function toward an antitumor phenotype. Dietary reduction of specific AAs, such as methionine or cystine shifted the presence of TAMs from a tumor-promoting towards a more tumor-suppressive, phenotype and modulated immune cell function. Overall, this study suggests that dietary modifications may enhance and promote more durable responses to immunotherapies in cancer patients.

Methods

Cell lines and culture of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs).

RP-B6-Myc cells generated from the B6-Myc transgenic mouse model (14), were serially cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Bone marrow was harvested from C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice, plated at 1×105 cells / ml, cultured in RPMI media containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1.5% L-Hepes (1M stock), 1% L-Glutamine (200mM stock), 1% NEAA (non-essential amino acids) (100x stock), 1% Sodium Pyruvate (100mM stock), and 2μL β-Mercaptoethanol, and treated with 30ng/ml M-CSF (Peprotech or BioLegend). Cells were allowed to adhere and differentiate for 5 days. On day 5, media was changed to either control [10%FBS, L-Cystine (270mM), L-Glutamine (300mg/L), L-Methionine (0.1mM; 15mg/L)], 1/2 methionine [10%FBS, L-Cystine (270mM), L-Glutamine (300mg/L), L-Methionine (0.05mM; 7.5mg/L)], or 1/2 methionine 1/3 cystine [10%FBS, L-Cystine (90mM), L-Glutamine (300mg/L), L-Methionine (0.05mM; 7.5mg/L)] media. After 24 hours, cells were treated with IFN-gamma (20ng/ml) (Peprotech) and LPS (100ng/ml) (Sigma Aldrich) to prime for M1 macrophage differentiation or IL-4 (5ng/ml) (Peprotech) for M2 macrophage differentiation.

Immunofluorescence.

Tissue specimens were fixed for 24 hours in neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedded and sectioned (5μm) as previously described (15). Tissue sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated through serial graded xylene and alcohol washes. H&E staining was performed using the standard methods. For F4/80 pan-macrophage immunohistochemical staining, antigen unmasking was achieved by incubating the slides in proteinase K solution for 20 minutes at 37ºC. For immunohistochemistry staining (IHC) sections were further incubated in hydrogen peroxide to reduce endogenous activity. We then blocked the tissues with 1% BSA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated the slides overnight with F4/80 primary antibody (1:1000, clone BM8, eBioscience 14–4801) at 4ºC. After primary antibody incubation, tissue sections were washed, incubated in horseradish-conjugated anti-rat secondary antibody per the manufacturer’s protocol (Vector Laboratories), enzymatically developed in diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Tissue sections were then dehydrated and mounted with coverslips sealed with cytoseal 60 (Thermo Scientific). Isotype negative controls were used for evaluation of specific staining. For immunofluorescence staining (IF) of tissue sections antigen unmasking was achieved by boiling the sections in 10mM sodium citrate (pH6) followed by serial washes and blocking in 5% rat serum, 5% FBS in PBS-T (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20), co-stained with either CD206 (Alexa Fluor 488, Clone C068C2, Biolegend 141709) and F4/80 (Alexa Fluor 594, Clone BM8 Biolegend 123140) or MHC II (FITC, I-A/I-E Clone M5/114.15.2, Biolegend 107605) and F4/80 and incubated overnight at 4ºC. Post primary incubation, slides were washed and counter stained with either DAPI (4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride) or Hoechst and mounted with vectorshield mounting medium (Vector laboratories). BMDMs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and co-stained for CD206 and F4/80 overnight at 4ºC followed by DAPI staining and mounting using vectashield mounting medium. Stained sections were analyzed either under bright field (IHC) or under the appropriate fluorescence wavelength (IF) using a Zeiss Axio microscope or an EVOS FL cell imaging microscope (Life Technology). Positive cell percentages were determined in a blinded fashion by analyzing four-five random 20x fields per tissue and quantified using Image J software.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Macrophages, cultured as described above, were washed with ice cold PBS and exposed to Accutase® (Biolegend 423201) for 15–20 minutes on ice. Cells were blocked with Fc Block (anti-mouse CD16/32 mAb; BD Bioscience) at 4ºC for 15 minutes, and stained with fluorescence conjugated antibodies against surface markers CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD11b (clone M1/70), F4/80 (clone BM8), MHC II (I-A/I-E; clone M5/114.15.2), CD206 (MMR; clone C068C2). Cells were then fixed in Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) and stained with antibodies against intracellular proteins including, iNOS (clone CXNFT) and Argiase1 (R&D IC5868A). Antibodies used for staining were purchased from BD Biosciences, Biolegend, eBioscience, and R&D Systems. Stained cells and isotype-control stained cells were assayed using an LSRII or Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For in vivo data, splenocytes, tumor cell suspensions, and peripheral blood cells were washed, blocked with Fc Block (anti-mouse CD16/32 mAb; BD Biosciences) at 4oC for 15 minutes, and stained with fluorescence conjugated antibodies against surface markers. TAM Panel [CD45(clone 30-F11), CD11b (clone M1/70), F480 (clone BM8), MHC II, CD206], MDSC Panel [CD45(clone 30-F11), CD11b (clone M1/70), Ly6C (clone AL-21), Ly6G (clone 1A8), PD-L1], T Regulatory / T-Cell Panel [CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD25, CD8a (clone 53–6.7), & CD3], and PD-1/PD-L1 Panel [PD-1, PD-L1, CD45, F480, Ly6C, Ly6G, CD11b, CD8, & CD4] antibodies purchased from BioLegend, eBioscience or BD Biosciences. Cells were then fixed in Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) and stained with antibodies against intracellular proteins, including TAM Panel [iNOS and Arginase1] & T Regulatory / T Cell Panel [FoxP3 (NRRF-30) and Granzyme B (clone GB11)]. The antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences, BioLegend, and R&D Systems and used in staining. Lineage antibody cocktail was purchased from eBioscience. Anti-mouse CCR2 antibody was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. Stained cells and isotype-control-stained cells, were assayed using a LSRII, LSR4 or Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo (FlowJo LLC, Tree Star), ModFit LT 4.1 software and GraphPad Prism7.

Western blot analysis.

Tumors or BMDMs from each treatment group were lysed using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Pierce). Protein concentrations were assessed using a standard BSA assay (Bio-Rad). 50ug of protein from each sample was subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Proteins of interest were detected with the following primary antibodies CD206 (1:500; Abcam ab64693), pS6 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 2211S), p-eIF2α (1:1000; Cell Signaling 9721S), β-actin (1:1000; Santa Cruz sc47778), STAT3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 4904S), pSTAT3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 9134S), STAT1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 9172S), pSTAT1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 9167S), EZH2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling 5246S) overnight at 4ºC. Following incubation with primary antibody the membranes were probed with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) and exposed to chemiluminescence per the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and exposed to film. Quantitative measurements of Western blot analysis were performed with ImageJ and GraphPad Prism7 software.

qRT-PCR and microarray analysis.

RNA concentration and purity were determined through measurement of A260/280 ratios with a Synergy Hi Multi-Mode reader. cDNA was prepared using the iScript kit (Bio-Rad) and qPCR was performed in triplicate for each sample using SYBR Master Mixture (Bio-Rad) or the SYBR Select Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were run on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real time PCR system. Sequence Detection Systems software v2.3 was used to identify the cycle threshold (Ct) values and to generate gene expression curves. Data were normalized to Gapdh expression and fold change was calculated. The primers used for target genes were: Gapdh 5’-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3’ & 5’-ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA-3’; iNOS, 5’-AACGGAGAACGTTGGATTTG-3’ and 5’-CAGCACAAGGGGTTTTCTTC-3’; Arg1, 5’-GCTGTCTTCCCAAGAGTTGGG-3’ and 5’-ATGGAAGAGACCTTCAGCTAC-3’; xCT, 5’- −3’ and 5’- −3’; Nrf2 5’-CTCGCTGGAAAAAGAAGTGG-3’ and 5’-CCGTCCAGGAGTTCAGAGAG-3’; Keap1 5’- ATGGCCACACTTTTCTGGAC-3’ and 5’- TCCTGTTGTCAGTGCTCAGG-3’; Atf4 5’- TCGATGCTCTGTTTCGAATG-3’ and 5’- GGCAACCTGGTCGACTTTTA-3’; Ccl2 5’- AGGTCCCTGTCATTCTG −3’ and 5’- TCTGGACCCATTCCTTCTTG −3’; Nfat5 5’- AAGGCAACTCAAAAGCTGGA −3’ and 5’- TGCAACACCACTGGTTCATT −3’. Expressions of the different genes were normalized to Gapdh. Relative expression was calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method.

Proteome Profiler.

Tumor tissue was homogenized in PBS containing protease inhibitors. Following homogenization, Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1%, frozen at −80C, thawed, centrifuged as 10,000g for 5 minutes, quantified and assayed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were processed and run on R&D Systems mouse XL cytokine array kit (Ary028). Analyses were performed using HLImage++ QuickSpots Tool (Western Vision Software) and GraphPad Prism7.

In vivo studies.

RP-B6-Myc cells were injected subcutaneously into male C57BL/6 mice as previously described (16). The experimental diets were prepared and sterilized by irradiation by the Envigo (Harlan Laboratories) facility. A summary of the composition and ingredients of each diet are shown in Fig. S1. Tumors grown subcutaneously in C57BL/6 mice were harvested for flow cytometry analysis as described below. All procedures were performed and approved in strict accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine, and with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animal guidelines. Six to eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were ordered from Charles River and housed in a sterile, pathogen-free facility. Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled room under a 12-hour light/dark schedule with water and food ad libitum. For diet and immunotherapy treatment studies, untreated RP-B6-Myc tumors were collected from passaging C57BL/6 mice, dissected into ~1mm2 tumor pieces and implanted subcutaneously into mice. All mice were operated on under sedation with oxygen, isoflurane and buprenorphine. Upon tumor establishment, ~50mm2, mice were randomly grouped and placed in either control or treatment groups. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Male C57BL/6 mice were randomized, via tumor size using a stratified randomization procedure, into control AIN93G and 80%. Female five- to six- week old Balb/c (Charles River Labs) were maintained as described above. One week prior to RENCA cell injection mice were placed into four groups: control diet, control diet + anti-PD-1 (Bio X Cell RPM1–14, rat IgG2a), 7% protein diet, or 7% protein diet + anti-PD-1. 70–80% confluent RENCA-Luc cells were harvested using 0.25% Trypsin (Corning) and suspended in a 1:1 ratio of matrigel (Corning) and HBSS (Gibco), 10ul containing 1×104 cells was injected under the renal capsule. Mice were imaged via bioluminescent IVIS imaging, and twice weekly measured via body weight measurement. All mice were under clinical observation for weight loss, lethargy, and hunched / ruffled appearance. Mice were randomly placed into treatment groups (5–10 mice / group) of diet alone (control vs 80% methionine restricted or 21% vs 7% dietary protein) or diet with immunotherapy treatment. Mice in the treatment groups received 20mg/kg of anti-PD-1 (RP-B6-Myc & RENCA) twice a week and survivin peptide vaccine (RP-B6-Myc) 1mg/ml for 4 weeks. Clodronate liposome treatments were administered every 3 days intraperitoneally (100ul of 100mg/ml solution). Tumor size and body weight were assessed and recorded twice per week. For tumors implanted subcutaneously, tumor size for the RP-B6-Myc model was measured in a blinded manner twice a week by caliper measurement of two diameters of the tumor (length and width), measurements were reported as tumor volume ((Length x Width2)/2 = mm3). Body weights were assessed using a weight scale and recorded in grams. Tissue and blood were collected under aseptic conditions. 400–600μL of blood was collected by eye bleeds (terminal) at the end of the experiment. Serum aliquots were stored at −80º for further analysis. Tumor tissues were excised, weighed, and processed for flow cytometry analysis, snap-frozen and stored in −80ºC, stored in trizol (Life Technologies) for RNA analysis, or fixed in 10% buffered formalin or OCT (optimal cutting temperature) medium for histopathology. Endpoint tumor weights were assessed using a weigh scale and recorded in grams. Fecal matter was collected from each mouse, snap frozen and stored at −80ºC for future analysis.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. For in vivo experiments, no animals were excluded from the analyses. Results of gene analysis and flow cytometric results were calculated using both Welch’s t test and one-way ANOVA analyses. Analysis of the proteomic profilers was accomplished by using multiple t tests and two-way ANOVA analysis for each protein. All tests were two-sided and p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All in vitro experiments were repeated at least 3 times independently to obtain biological triplicates.

Results

Dietary protein and AA-restriction inhibits macrophage polarization towards an M2 phenotype.

We first assessed macrophage infiltration into the TME of SCID mice bearing the LuCap23.1 patient-derived xenograft prostate cancer model, which had been fed 20% or 7% protein-based diets diet (15). We observed no significant difference in the overall number of TAMs (Fig. S2A) but an increase in M1-like TAMs along with a decrease in the M2-like phenotype in those mice fed a 7% diet (Fig. 1A, B). Next, we developed an in vitro model to assess the effect of specific AA alterations on macrophage polarization and function by focusing on methionine restriction since it mirrors the effects of calorie restriction (2) or dietary protein restriction (17). BMDMs following polarization with prototypic M1- (IFN-γ + LPS) or M2- (IL-4) stimuli were collected and analyzed for changes in viability and hallmark features of M1- (iNOS) or M2- (Arg1) type macrophages (Fig. 1C). While no reduction in the viability of BMDMs was observed after exposure to AA-restricted conditions (Fig. S2B–C), a significant increase in iNOS and decrease in Arg1 levels occurred (Fig. 1D, E).

Figure 1: Protein / AA-restriction inhibits M2 like macrophage tumor infiltration and blunts the expression of M2 signatures.

(A) (Top) Representative M1 macrophage staining for F4/80 (red) and MHCII (green) for 21% and 7% protein diet cohorts in the LuCaP23.1 model. (Bottom) Representative M2 macrophage staining for F4/80 (red) and CD206 (MMR) (green) for 21% and 7% protein diet cohorts in the LuCaP23.1 model. (B) (Left) Blinded quantification of M1 macrophage presence in the TME based on random selection of five fields per tissue. (Right) Blinded quantification of M2 macrophage presence in the TME. (Bottom right) Western blot analysis showing M2 marker CD206 presence in 21% versus 7% protein diet conditions. (C) Schematic of in vitro macrophage stimulation. (D) Flow cytometry analysis for M1 (CD45+ CD11b+ F4/80+ iNOS+) and M2 (CD45+ CD11b+ F4/80+ Arg1+) in AA-restricted BMDMs 48 hours post-stimulation. The experiment was repeated at least 3 times independently. Legend: 1. Control media, 2. 1/2 methionine media, 3. 1/2 methionine 1/3 cystine media (E) mRNA fold change expression levels of M1 and M2 macrophage markers, iNOS and Arg1, respectively. The experiment was repeated at least 3 times independently. n = 9. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined by student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Dietary protein and AA-restriction reverses the immunosuppressive function of M2-type macrophages.

Next, we examined whether the observed alteration in the polarization of BMDMs was indicative of increased tumoricidal activity. Polarized BMDMs were co-cultured with the prostate cancer (CaP) cell line RP-B6-Myc (16). AA restriction alone had a moderate effect on altering the viability of RP-B6-Myc cells following 72 hours of exposure (Fig. S3A). Both M1- and M2-type macrophages became increasingly tumoricidal after co-culture under AA-restricted conditions (Fig. S3B). Further, M2-type macrophages, which impair CD8+ T cell activity in part by reducing Granzyme B expression, lose their suppressive capability when cultured in AA-restricted conditions (Fig. S3C). In contrast, T cells, activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies do not show loss of cell viability or reduction of Granzyme B expression (Fig. S3D).

STAT1 and STAT3 transcriptionally regulate the differentiation of monocytes/ macrophages into antitumor M1 or M2 pro-tumor subtypes, respectively (18). We re-exposed ‘polarized’ AA-restricted M1- or M2-type BMDMs to either STAT1 (IFN-ɣ+LPS) or STAT3 (IL-6) activators, and STAT1/3 phosphorylation was analyzed. The M2-type macrophages cultured under restricted conditions were the most altered (data not shown). These cells were unable to recover their capacity to phosphorylate STAT3, but rather showed more inhibition of p-STAT3 than the M1 counterpart. M2-type macrophages also showed an increase in their capacity to phosphorylate STAT1, which supports a more tumoricidal M1-type response.

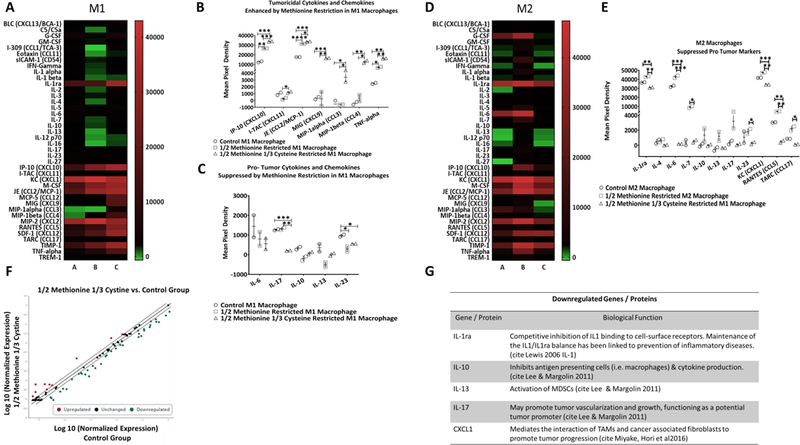

AA-restriction alters cytokine production by BMDMs.

Then, we analyzed the media from our co-culture assay and observed that M1-polarized macrophages displayed a cytokine/chemokine profile consistent with an anti-tumor/pro-inflammatory phenotype, including CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL2/MCP-1, CXCL9, CCL3, CCL4, and TNF-α (Fig. 2A, B), and a reduction in pro-tumor cytokines and chemokines including IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-33 (Fig. 2C). M2-polarized macrophages, when cultured in AA-restrictive conditions, showed a decrease in pro-tumor cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1ra, IL-6, IL-23, CXCL1, CCL5, and CCL17 (Fig. 2D, E). Because these cytokine/chemokine profiles have been shown to play a crucial role in antitumor immunity (19), we expanded our analysis to a panel of 84 inflammatory proteins (Fig. 2F). This more comprehensive analysis revealed five key downregulated M2-type macrophage-associated targets, IL-1ra, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, and CXCL1, which overlapped with our proteome profiler (Fig. 2G). We recognize that amino acid restriction elicits a pleiotropic cytokine response that spans a continuum of alterations due to the complex biologic heterogeneity of such an extrinsic intervention. Thus, given the complexity of the impact of amino acid restriction on the host, it is likely that the resultant cytokine profile is not all-or-none, but rather a blend of pro- or anti-inflammatory markers.

Figure 2: Macrophage tumoricidal function, cytokine release, and gene expression are enhanced in M1 and M2 primed BMDMs following AA-restriction.

(A) Heatmap displaying the differential expression pattern of 40 mouse cytokines, chemokines, and acute phase proteins from M1 differentiated (IFN-γ + LPS treated) macrophages in 1/2 methionine or M [B] (n = 2) and 1/2M 1/3 cystine or C media [C] (n = 2) compared to M1 macrophages in control media [A] (n = 2). (B) Tumoricidal cytokines and chemokines which were enhanced with MR in M1 polarized macrophages. (C) Tumor supportive chemokines and cytokines which were downregulated following AA-restriction in M1 macrophages. (D) Heatmap displaying the differential expression pattern of 40 mouse cytokines, chemokines, and acute phase proteins from M2 differentiated (IL-4 treated) macrophages in 1/2 M [B] (n = 2) and 1/2M 1/3 C media [C] (n = 2) compared to M2 macrophages in control media [A] (n = 2). (E) Pro-tumor, M2 associated proteins which were downregulated following AA-restriction. (F) Using an RT2 Profiler mouse inflammatory cytokine and receptor PCR array from Qiagen, a scatterplot showing the expression of up- and down-regulated genes was generated (n = 2 per group). Red dots represent upregulated genes, black dots represent unchanged genes, and green dots represent downregulated genes. (G) List of the top downregulated proteins / genes which were represented in both the ARY006 and the mouse inflammatory cytokine and receptor PCR RT2 Profiler (PAM-011A). Results are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using student’s t test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Dietary protein and AA-restriction inhibits tumor growth in syngeneic mouse models of prostate and kidney cancer.

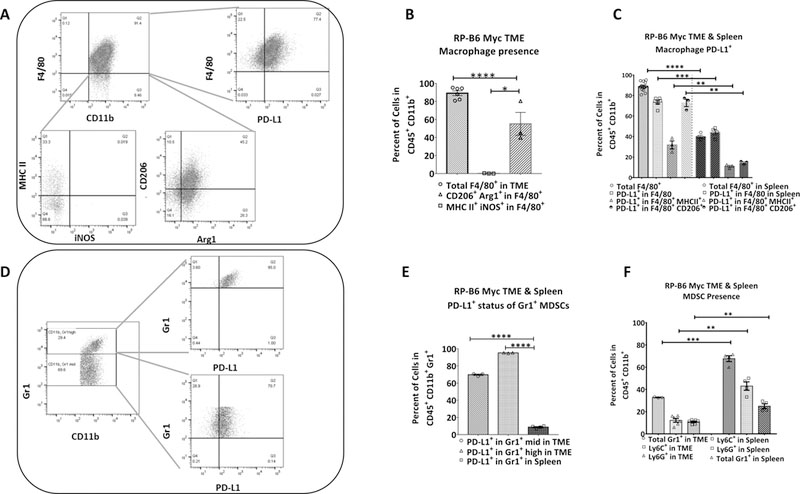

Next, we tested whether in vivo dietary AA or protein restriction would inhibit tumor growth and enhance the effect of immunotherapy. To test this hypothesis, we used two syngeneic mouse models, RP-B6-Myc and RENCA (16), which present a high infiltration of M2-like TAMs (Fig. S4A, 3A–F) (20). In support of the role of macrophages in our experimental models, we observed that dietary protein restriction failed to reduce tumor growth under macrophage-depleted conditions (Fig. S5). To examine the impact of dietary methionine / cystine restriction (M/CR), we developed an 80% methionine restricted diet (80MR) (Fig. S1). Our experimental diet did not contain cysteine, as the trans-sulfuration pathway can overcome MR via cystine, thus negating the effect of methionine restriction (21). To assess the immunomodulatory activity of 80MR, we combined dietary modification with two different forms of immunotherapy. The presence of phenotypically PD-L1+ and immunosuppressive myeloid populations in these tumor models (Fig. 3A–F,) suggest the use of anti-PD-1 strategy. Survivin expression, a tumorigenic protein which promotes tumor vascularization and inhibits apoptosis and is associated with poor prognosis in CaP patients (22), has been previously confirmed in Myc-CaP tumors (16), providing a rationale for combination with a survivin peptide-based vaccine in the RP-B6-Myc tumors (23). Anti-PD-1 treatment allows cytotoxic T cell proliferation and activation in the TME by release of the inhibitory checkpoint (24). RP-B6-Myc and RENCA tumors respond only modestly to single agent anti-PD-1 or survivin peptide vaccine (REF). While the restriction of total protein did not significantly impact tumor growth, restricting methionine and cystine via the 80MR diet significantly reduced tumor growth and end-point tumor weights relative to the control diet group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4A–C). Tumor growth in the 80MR cohort treated with the survivin peptide vaccine and anti-PD-1 was significantly inhibited (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A, B). Recognizing that restriction of only methionine and cystine is not readily translatable into the clinic, we returned to our isocaloric 21% and 7% protein diets (15). Protein restriction alone did not significantly inhibit the growth of these syngeneic tumor models (Fig. 4C, D). However, when we combined the low protein (7%) diet with either vaccine or anti-PD-1 treatment, significant inhibition was observed (Fig. 4C, D), and PR combined with PD-1 blockade significantly prolonged the survival in the orthotopic RENCA model (Fig. 4E).

Figure 3: Characterization of tumor infiltrating macrophages and MDSC.

(A) Baseline flow cytometric analysis of the RP-B6-Myc tumor shows infiltration of M1 (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+MHCII+iNOS+) and M2 (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206+Arg1+) macrophages. (B) Quantitative representation of FACS analysis for total M1 and M2 macrophage infiltration into the TME (n = 4–6). (C) Quantitative representation of the PD-L1 expression on M1 and M2 macrophages in both tumor and spleen (n = 3–4). (D) Baseline flow cytometric analysis of the RP-B6-Myc tumor examining the infiltration of PMN- (CD45+CD11b+Gr1high) and M- (CD45+CD11b+Gr1mid) MDSCs. (E) Quantitative analysis of MDSC infiltration into the TME relative to MDSC presence in the spleen (n = 4–6). (F) Quantitative analysis of MDSC PD-L1 expression re (n = 3–4). Results are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using student’s t test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 4: Translation of in vitro M/CR into the in vivo RP-B6-Myc and RENCA models results in significant inhibition of tumor growth and enhances IT responses.

CaP model, RP-B6 Myc: (A) (Top) Treatment schema. Two weeks following RP-B6 Myc tumor implantation mice were begun on a treatment regimen of twice weekly anti-PD-1 (20mg/kg) and weekly survivin peptide vaccine (1mg/ml). (Graph) Tumor volume measured as mm3 (n=10 mice / group). Comparison of the control+IT and 80MR+IT tumor growth curves. (B) The total tumor burden (grams) at day 32 compared to the control AIN93G. (C) (Top) Treatment schema. (Graph) Tumor volume measured as mm3 (n=10 mice / group). Renal cell carcinoma model, RENCA: (D) (Top) Treatment schema. (Graph) The total RENCA tumor burden at day 32 compared to the control AIN93G cohort. (E) Kaplan Meier survival curve of the RENCA 21% and 7 % diet cohorts ± anti-PD-1. Results are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using student’s t test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

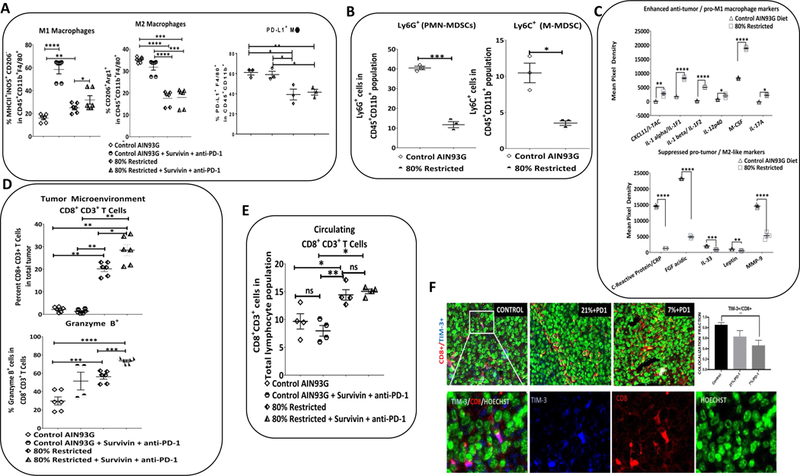

Diet modification alters the landscape of immune infiltrates.

We observed a significant increase in the presence of anti-tumor/pro-inflammatory F4/80+ MHC class II+ iNOS+ M1-type macrophages under restrictive diets, 80MR and 7% dietary protein, with a significant increase in M1-type macrophages in immunotherapy (IT) treatment groups (Fig. 5A, S4B). We observed also significant decreases of PD-L1+F4/80+ and F4/80+ CD206+ Arg1+ macrophages in the 80MR cohort compared to the control diet cohort; alterations in M2-type macrophages were not compounded by IT treatment for the RP-B6-Myc model but were further reduced in the RENCA model (Fig. 5A, S4B). The striking difference observed in the 80MR study, relative to the 7% diet, further supports that cystine/methionine restriction is critical to altering the macrophage subtypes within the TME. We also examined the TME for changes in the infiltration of MDSCs (Fig. 5B), and observed significant decreases in both polymorph nuclear (PMN)- and monocytic (M)-MDSC subsets, which typically support tumor growth and possess the potential to differentiate into TAMs (25, 26). By using a proteome profiler array (Ary028) to assess the production of chemokines and cytokines involved in immune cell infiltration (Table S1), we found increased M1-type pro-inflammatory proteins, including CXCL11/I-TAC, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-12p40, M-CSF, and IL-17A. In the case of IL-17, it has been implicated as pro-inflammatory cytokine when associated with a M1-type macrophage profile, while pro-tumorigenic when associated with M2-type macrophage- profile (27, 28). In addition to an increased M1-type macrophage signature, we observed a concomitant reduction in M2-type and tumor growth/progression-associated proteins, including C-reactive protein, FGF acidic, IL-33, leptin, and MMP9 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5: Methionine restriction in vivo changes tumor infiltrating immune cells and alters the pattern of released cytokines.

CaP model, RP-B6 Myc: (A) Quantitative FACS analysis of the macrophage populations in the TME in control and 80MR conditions. (B) Quantitative FACS analysis of the myeloid compartment in the TME including PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs in the 80MR cohort relative to the control. (C) Significantly enhanced anti-tumor, pro-inflammatory, M1 macrophage linked proteins in the 80MR diet group. Significantly inhibited proteins which have been linked to tumor growth and progression and M2 pro-tumor macrophage infiltration / function. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using student’s t test with Welch’s correction. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. n = 3–5 tumors used per analysis. (D)Quantitative FACS analysis of the lymphoid compartment in the TME, including CD8+ CD3+ T cell and CD8+ CD3+ Granzyme B+ T cell presence across control, control+IT, 80MR & 80MR+IT cohorts. (E) Circulating CD8+ CD3+ T cell across control, control+IT, 80MR & 80MR+IMT cohorts. (F) Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue specimen sections derived from RENCA tumor treated with different dietary restrictions; control (left), 21% (middle); 7% (right) were stained by immunofluorescence with antibodies directed against mouse CD8 (red), Tim-3 (blue) and counterstained with Hoechst (green). Colocalization of these three markers can be detected by merging the mono-staining image. White box (top, left), cells expressing both CD8 and TIM-3 (pink) was enlarged in (C) (left) and split into each monostaining counterpart; TIM-3 (blue), CD8 (red) and Hoechst (green). An automated count based on a user-defined algorithm in ImageJ with coloc plugin was then performed (graph), which quantified the colocalization fraction of TIM-3 with CD8+ cells in the tumor, based on random selection of five fields per tissue. The experiment was repeated at least 3 times independently. n = 6 (technical). Results are expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey. **p<0.01

The TME infiltration of CD8+ CD3+ T cells, a key component of antitumor immunity, has been linked to improved patient prognosis (29). Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in tumor infiltrating CD8+ CD3+ T cells and cytotoxic Granzyme B+ CD8+ CD3+ T cells in the 80MR and even further in the 80MR+IT cohorts (Fig. 5D). We also observed a significant increase in circulating CD8+ CD3+ T cells in the 80MR cohorts compared to the controls (Fig. 5E) along with an increase in the ratio of CD8+ CD3+ T cells to M1- or M2-type macrophage, as well as PMN- or M-MDSCs in response to dietary M/CR. Further analysis of the T cell infiltrates within the TME revealed reduced co-expression of CD8 and TIM-3 (Fig. 5F), providing additional evidence that the TME is transitioning away from a pro-tumor environment (30, 31). We also observed significant increases in the IT groups for the CD8+ CD3+ to MDSC ratio (Fig. S6A–D) (24).

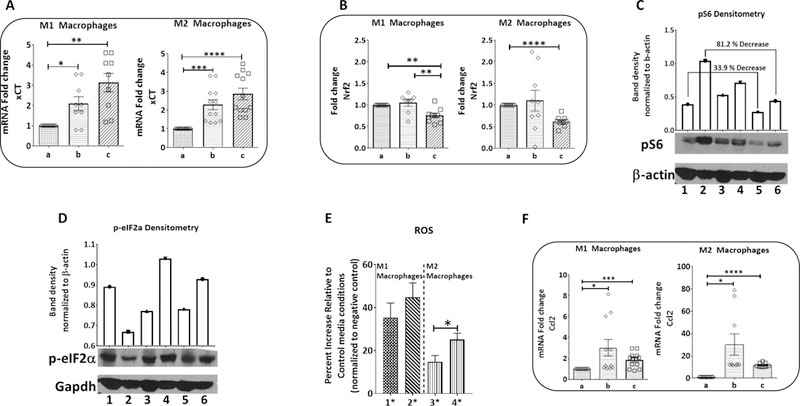

AA-restriction modulates the molecular programming of macrophage polarization.

AA-restriction and oxidative stress have been shown to upregulate the cystine glutamate transporter, which regulates intracellular ROS that distinguish M1/M2 macrophage polarization phenotypes, xCT expression (32, 33). We observed that xCT (34) is highly expressed in M1-type macrophages (Fig. S7A) and increased in AA-restricted BMDMs, and the mTOR pathway and redox sensitive transcription factor, Nrf2, is down-regulated along with phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (pS6) (Fig. 7A-C). Similarly, the negative regulator of Nrf2, Keap1, which leads to ROS/mTOR-dependent Nrf2 ubiquitination (35), is significantly upregulated under AA-limited conditions (Fig. S7B). Atf4 is a transcription factor for xCT linked to LPS-induced TLR4 signaling and cytokine production (36), and when phosphorylated, eIF2α is unable to bind to and inhibit Atf4 (37). eIF2α phosphorylation under AA-restricted conditions (Fig. 6D), in conjunction with an increase in Atf4 gene expression for M1- and for M2-type macrophages were observed (Fig. S7C). Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) in macrophages is indicative of M1-type polarization and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine release (33). There was a significant increase in ROS production in both M1- and M2-type macrophages under the AA-restricted conditions (Fig. 6E), along with Nfat5, which promotes the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Ccl2, TNF-α, and IL-12, and is required for iNOS induction (38) (Fig. S7D). Additionally, we observed a significant increase in the production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including Ccl2, validated by quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 6F) (39).

Figure 6: AA-restriction modulates the molecular programming of macrophage polarization:

(A) Relative expression of cystine & glutamine transporter xCT in M1 and M2 phenotypes in response to amino acid restriction. (B) Normalized Nrf2 gene expression. (C) Protein level expression of mTOR pathway downstream target, pS6. (Top) Densitometry analysis of the phosphorylated S6 seen in the Western blot. (Bottom) Western blot analysis of mTOR activation marker pS6. (D) Protein level analysis of negative regulator of Atf4, eIF2a, (top) densitometry analysis of the Western blot (bottom). (E) Quantitative analysis from Enzo ROS-ID® Total ROS Detection Kit in M1 and M2 conditions (n = 9). (F) Normalized gene expression analysis of pro-inflammatory cytokine Ccl2. All qRT-PCR results are normalized to Gapdh and run in triplicate for n=3 independent experiments. Results are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using student’s t test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Legend: a. control media, b. 1/2M, c. 1/2M 1/3C; 1. control M1, 2. control M2, 3. 1/2M M1, 4. 1/2M M2, 5. 1/2M 1/3C M1, 6. 1/2M 1/3C M2; 1*. 1/2M M1 2*. 1/2M 1/3C M1 3*. 1/2M M1 4*. 1/2M 1/3C M2.

Dietary M/CR alters the polyamine synthesis pathway in the TME.

Inhibition of the polyamine biosynthesis pathway has been shown to alleviate tumor escape, enhance T cell responsiveness, and inhibit the differentiation and accumulation of immunosuppressive myeloid cells, including M2-type TAMs and MDSCs, while promoting M1-type TAMs (40). We did not observe an overall reduction in polyamines either in vitro (Fig. S8A) or in vivo with M/CR, but there was a significant reduction of spermine (SPM) in the TME of our RP-B6-Myc model (Fig. S8B). This finding, combined with the increased spermidine (SPD) to SPM, and putrescine (PUT) to SPM ratios (Fig. S8C) in the TME, indicates that our intervention may be inhibiting the polyamine biosynthesis pathway (41). To examine whether this may impact macrophage polarization, we next inhibited the synthesis of polyamines, using difluoromethylornithine (DFMO). In our system, the inhibition of polyamine synthesis resulted in an increased M1-type macrophage polarization in control conditions, and a significant reduction of M2-type macrophages in both control and AA-restricted media, suggesting that DMFO is sufficient to phenocopy the effects of AA-restriction (Fig. S8D), and inhibition of the polyamine biosynthesis pathway may contribute to macrophage polarization in our model. Upstream of polyamine biosynthesis, the SAM (S-adenosylmethionine):SAH (S-adenosylhomocysteine) ratio is directly impacted by circulating methionine. While we saw no significant alteration in the overall levels of SAM and SAH in our B6-Myc tumor model (data not shown), we did find a significant negative correlation (Pearson correlation: R-value = 0.652, p < 0.05) in SAH and SAM levels in the 80MR cohort, with no clear correlation between the SAM and SAH levels in the control diet cohort (Pearson correlation: R-value = 0.184, p > 0.5)

Dietary M/CR alters the gut microbiota which may contribute to immune system alterations.

Gut microbiota is influenced by dietary protein (42), and has been linked to immune activation in response to cancer treatments (43). Bacterial genera which have been linked to cancer progression include Prevotella and Ruminococcus, while Lactobacillus is negatively correlated (44). Prevotella and Ruminococcus are increased in colorectal cancer and to have detrimental effects on the immune system by altering T cell and myeloid cell function. Conversely, Lactobacillus is known to play an immune-stimulatory role which may involve the TRAIL and IFN-γ pathways (45) (46). The microbiomes of mouse fecal samples from the control and 80MR groups, determined by small bacterial ribosomal subunit (16S) sequencing were clearly distinguished by Venn Diagram and Principal coordinate analyses of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU) (Fig. S9A–C). Next, we investigated OTUs, which revealed dramatic shifts in the microbial community of the 80MR relative to the control diet cohort. Consistent with our community wide beta diversity and OTU profiling, we observed changes in numerous bacterial populations and focused on Ruminococcaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Lactobacillaceae, which have been directly linked to cancer progression and immune alterations (47). We observed a significant decrease in the relative abundance of multiple Ruminococcaceae and Prevotellaceae family OTU in the 80MR cohort. Additionally, we observed a significant increase in the presence of members of the Lactobacillaceae family (Fig. S9D–F).

Taken together, these results provide new insights on the impact of AA-restriction and underlying pathways involved in macrophage polarization and function (Fig. S10).

Discussion

In this study, we report that a reduction in dietary protein or methionine/cystine intake significantly reduces the polarization of M2-type macrophages. Importantly, these dietary interventions also impact M2-type macrophage functions and TME infiltration in vivo. M/CR was sufficient to recapitulate the antitumor effect observed in our previous study with dietary protein restriction (2, 15). Based on our cystine/methionine restricted diet studies, we observed an inhibition of tumor growth which was significantly enhanced with immunotherapy in the protein restriction setting. We also found a resulting shift away from an immunosuppressive TME, one characterized by transition of an M2- to M1-type macrophage response, accompanied by modulation of the mTOR/trans-sulfuration/xCT/cytokine production pathway. Models with high infiltration of M2-type macrophages were chosen to reflect clinical characteristics of advanced stage prostate cancer. Recent studies suggest the role of macrophages in promoting prostate-to-bone metastases and underscore a strong correlation between TAM density and prediction of clinical outcome in advanced stage prostate cancer patients (48) (49).

To examine the effect of AA alterations on key functional macrophage pathways, we hypothesized that, since macrophages are driven by circulating stimuli, including available nutrients, they may also be impacted by decreased levels of total protein. AA composition of the diet appears to play an essential role in the effects described here, as the presence of varying AAs are known to feed into central nutrient sensing pathways, including the mTOR and trans-sulfuration pathways (17, 44, 45). Moreover, these pathways are critical to the response of the innate immune system to diseases, including infections and cancer (12, 17). Our study suggests that AA-restriction, mimicking reduced dietary protein levels in the host, leads to significant alterations in nutrient sensing and macrophage-polarizing pathways. We observed inhibition of the M2-driving, nutrient sensing mTOR, Nrf2, and PI3K/AKT pathways which have been linked to increased production of pro-tumor or decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (50) (38, 46). Further, we observed an increase in Nfat5 expression, which is intricately linked to increased production of pro-inflammatory, M1-type cytokines (38), and an increase within the Atf4/Xct axis followed by a moderate increase in ROS.

An evolving concept that contributes to the understanding of macrophage polarization is that the ROS spectrum impacts macrophage status, where those macrophages with low ROS are of an M2 status, moderate ROS are of M1 status, and high ROS leads to apoptosis (33). Given the importance of macrophage polarization and function in cancer progression (8), we propose that dietary protein/AA-restriction contributes to a pivotal shift in the function of tumor-infiltrating macrophages or TAMs. Our data define, for the first time to our knowledge, a comprehensive outline of the association of multiple nutrient sensing pathways, their response to AA restriction, and the subsequent impact on macrophage polarization. Macrophages have been implicated in the progression and aggressiveness of prostate and renal carcinomas (9). Through the use of a highly immunogenic, syngeneic mouse model of prostate cancer, we determined that dietary M/CR led to significant pro-inflammatory changes in the tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Thus, we propose that these dietary modifications, in particular protein restriction, may enhance the response of the host system to immunotherapies.

Accumulation of myeloid cells within the TME, tumor escape, and the magnitude of T cell responsiveness have recently been connected to the polyamine biosynthesis pathway (40). Here we show preliminary evidence linking polyamine biosynthesis to macrophage polarization in the TME. Importantly, direct blockade of polyamine biosynthesis via inhibition of ODC1 with DFMO resulted in the same increase in M1-type macrophage polarization and reduction of M2-type macrophages that was seen with dietary restriction of methionine. Our data indicate a potential causal link between dietary MR and the polyamine synthesis pathway which is known to promote pro-inflammatory M1-type macrophage responses in the TME (40). Taken together, these results open potential future directions for combining dietary modifications with polyamine blockade in the presence of IT regimens.

Recent research has shown a critical link between systemic immune responses to chemotherapeutic treatments and the gut microbiota (43, 47). In particular, Prevotella and Ruminococcus are linked to inhibitory effects on the function of myeloid cells and T cells in cancer patients (45), while Lactobacillus has shown to promote immune stimulation potentially via IFN-γ and TRAIL pathways (46) (48, 49). In the present study, we show a correlation between shifts toward anti-tumor TMEs, an increase in Lactobacillaceae, and a reduction in members of the Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcaceae. This correlation may indicate that dietary protein restriction alters the gut microbiome in tumor-bearing animals, which may in turn support antitumor immune responses. Future studies will elucidate this link between the gut microbiota and the polarization and function of macrophages within the TME.

In our study, we examined two immunological approaches, a survivin-based peptide vaccine in combination with PD-1 inhibition in a prostate cancer model, and PD-1 inhibition alone in a renal cell carcinoma model, and found that dietary protein restriction may play an understudied, supportive role for cancer immunotherapy. We recognize that our experimental approach has a limitation regarding the timing of the dietary intervention. MR initiated after tumor implantation did not enhance the effect of the survivin peptide vaccine (data not shown). One potential explanation is that the RP-B6-Myc model has a much faster growth rate than our original models LuCaP 23.1 and LuCaP 35, where the dietary intervention had an antitumor effect also after tumor implantation (15). Thus, the impact of MR/PR on the tumor microenvironment and immunomodulation may require time. Future experiments will need to elucidate the minimum period necessary for the dietary intervention to elicit its immunomodulatory activity. Nevertheless, we believe that our observations have a significant clinical relevance. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are changing the therapeutic paradigm for several solid tumor types, including renal cell carcinoma (51) (50). However, to date, only a minority of patients fully benefit from this therapeutic approach. Our data suggest that, even temporary, dietary protein restriction may affect the immunosuppressive TME and enhance the response to immunotherapies, which awaits comprehensive analyses in appropriately designed future clinical trials. The chemokine and cytokine profile altered by PR/MR in mice will provide a platform for pharmacodynamic assessment in patients. For example, the dramatic reduction of C-reactive protein observed in our model is a potential clinical biomarker. To translate these preclinical results to a clinic setting, dietary protein restriction may be implemented for a short “sensitization” period to subsequently “prime” the immune system to IT. Based on these preclinical data, we opened a pilot clinical study where patients with castration resistant CaP eligible for sipuleucel-T, a prostate cancer vaccine, are randomized to either 20% or 10% dietary protein during IT. Patients receive prepared meals twice a week during the 7-week period while they undergo apheresis and infusion of sipuleucel-T. Dietary protein uptake is being monitored by measuring blood urea nitrogen levels, while the impact on the immune system is evaluated by flow cytometric analyses of T cell subsets.

In summary, through dietary MR, macrophages are directed towards a more tumoricidal phenotype. We have developed a model via proteomic and gene analyses that identified interconnected mechanisms by which dietary modifications promote the differentiation of antitumor, M1-type macrophages. Further studies are necessary to dissect the contribution of modulating nutrient sensing pathways on innate vs. adaptive immune cells vs. tumor cells. Taken together, we believe that our findings have translational relevance as we envision that temporary diet modifications may prime the immune system during the initial treatment with immunotherapy. Therapeutic targeting of macrophages achieved by a dietary modification, rather than a pharmacological approach, represents an exciting opportunity for the clinical testing of this supportive tool to impact “inflamed” tumors and enhance the efficacy of current immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Translational relevance.

Nutrition and cancer represents an exciting field for laboratory and clinical research. However, to date, the role of specific dietary modifications in altering the immune system and contributing to tumor response to immunotherapies remains unclear. In this study, we report that dietary protein/methionine restriction has a significant effect on reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages toward a more tumoricidal phenotype. More importantly, our data suggest that dietary protein restriction enhances the antitumor effects of immunotherapies in two animal models of prostate and renal cell carcinoma. This finding has translational significance as it supports the rationale for dietary protein restriction in cancer patients receiving immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

This study was in part supported by institutional funding from Roswell Park Cancer Institute and Indiana University, Simon Cancer Center (RP). RP was in part supported by NIH R01CA224342–01. SIA was supported by NIH R01CA172105.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aronson WJ, Barnard RJ, Freedland SJ, Henning S, Elashoff D, Jardack PM, et al. Growth inhibitory effect of low fat diet on prostate cancer cells: results of a prospective, randomized dietary intervention trial in men with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2010;183(1):345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana L, Weiss EP, Villareal DT, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term effects of calorie or protein restriction on serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentration in humans. Aging Cell. 2008;7(5):681–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang M, Kenfield SA, Van Blarigan EL, Batista JL, Sesso HD, Ma J, et al. Dietary patterns after prostate cancer diagnosis in relation to disease-specific and total mortality. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2015;8(6):545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Chute CG, et al. A prospective study of dietary fat and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(19):1571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson KM, Giovannucci EL, Mucci LA. Lifestyle and dietary factors in the prevention of lethal prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(3):365–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori S Editorial Comment to Cruciferous vegetables intake and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Urol. 2012;19(2):141–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augustsson K, Michaud DS, Rimm EB, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. A prospective study of intake of fish and marine fatty acids and prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):64–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen W, Ma T, Shen X-n, Xia X-f, Xu G-d, Bai X-l, et al. Macrophage-Induced Tumor Angiogenesis Is Regulated by the TSC2–mTOR Pathway. Cancer Research. 2012;72(6):1363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanciotti M, Masieri L, Raspollini MR, Minervini A, Mari A, Comito G, et al. The role of M1 and M2 macrophages in prostate cancer in relation to extracapsular tumor extension and biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:486798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercalli A, Calavita I, Dugnani E, Citro A, Cantarelli E, Nano R, et al. Rapamycin unbalances the polarization of human macrophages to M1. Immunology. 2013;140(2):179–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weichhart T, Costantino G, Poglitsch M, Rosner M, Zeyda M, Stuhlmeier KM, et al. The TSC-mTOR signaling pathway regulates the innate inflammatory response. Immunity. 2008;29(4):565–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weichhart T, Hengstschlager M, Linke M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(10):599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hongfeng Ai DJ; Westerterp Marit; Murphy Andrew J.; Wang Mi; Ganda Anjali; Abramowicz Sandra; Welch Carrie; Almazan Felicidad; Zhu Yi; Miller Yury I.; Tall Alan R. Disruption of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 in Macrophages Decreases Chemokine Gene Expression and Atherosclerosis. Circulation Research. 2014;114(10):1576–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis WJ, Vessella RL, Buhler KR, Bladou F, True LD, Bigler SA, et al. Characterization of a novel androgen-sensitive, prostate-specific antigen-producing prostatic carcinoma xenograft: LuCaP 23. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(6):1039–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontana L, Adelaiye RM, Rastelli AL, Miles KM, Ciamporcero E, Longo VD, et al. Dietary protein restriction inhibits tumor growth in human xenograft models. Oncotarget. 2013;4(12):2451–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis L, Ku S, Li Q, Azabdaftari G, Seliski J, Olson B, et al. Generation of a C57BL/6 MYC-Driven Mouse Model and Cell Line of Prostate Cancer. Prostate. 2016;76(13):1192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha R, Cooper TK, Rogers CJ, Sinha I, Turbitt WJ, Calcagnotto A, et al. Dietary methionine restriction inhibits prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in TRAMP mice. Prostate. 2014;74(16):1663–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Cao X. The origin and function of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James BR, Anderson KG, Brincks EL, Kucaba TA, Norian LA, Masopust D, et al. CpG-mediated modulation of MDSC contributes to the efficacy of Ad5-TRAIL therapy against renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(11):1213–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshorbagy AK, Valdivia-Garcia M, Mattocks DA, Plummer JD, Smith AD, Drevon CA, et al. Cysteine supplementation reverses methionine restriction effects on rat adiposity: significance of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(1):104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu S, Adisetiyo H, Tamura S, Grande F, Garofalo A, Roy-Burman P, et al. Dual inhibition of survivin and MAOA synergistically impairs growth of PTEN-negative prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(2):242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danilewicz M, Stasikowska-Kanicka O, Wągrowska-Danilewicz M. Augmented immunoexpression of survivin correlates with parameters of aggressiveness in prostate cancer. Polish Journal of Pathology. 2015;1:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curran MA, Montalvo W, Yagita H, Allison JP. PD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(9):4275–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: expect the unexpected. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3356–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orillion A, Hashimoto A, Damayanti NP, Shen L, Adelaiye-Ogala R, Arisa S, et al. Entinostat neutralizes myeloid derived suppressor cells and enhances the antitumor effect of PD-1 inhibition in murine models of lung and renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakai K, He Y-Y, Nishiyama F, Naruse F, Haba R, Kushida Y, et al. IL-17A induces heterogeneous macrophages, and it does not alter the effects of lipopolysaccharides on macrophage activation in the skin of mice. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Atsuta I, Liu S, Chen C, Shi S, Shi S, et al. IL-17-mediated M1/M2 Macrophage Alteration Contributes to Pathogenesis of Bisphosphonate-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(12):3176–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apetoh L, Smyth MJ, Drake CG, Abastado JP, Apte RN, Ayyoub M, et al. Consensus nomenclature for CD8+ T cell phenotypes in cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(4):e998538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(10):2187–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Veenstra RG, Weigel BJ, Hirashima M, Munn DH, et al. Coexpression of Tim-3 and PD-1 identifies a CD8+ T-cell exhaustion phenotype in mice with disseminated acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(17):4501–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridges RJ, Natale NR, Patel SA. System x(c)(−) cystine/glutamate antiporter: an update on molecular pharmacology and roles within the CNS. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;165(1):20–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan HY, Wang N, Li S, Hong M, Wang X, Feng Y. The Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophage Polarization: Reflecting Its Dual Role in Progression and Treatment of Human Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:2795090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Habib E, Linher-Melville K, Lin HX, Singh G. Expression of xCT and activity of system xc(−) are regulated by NRF2 in human breast cancer cells in response to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2015;5:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichimura Y, Waguri S, Sou YS, Kageyama S, Hasegawa J, Ishimura R, et al. Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2013;51(5):618–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, Ruiz-Rosado Jde D, Popovich PG, Partida-Sanchez S, et al. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rauscher R, Ignatova Z. Tuning innate immunity by translation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(6):1247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi S, You S, Kim D, Choi SY, Kwon HM, Kim HS, et al. Transcription factor NFAT5 promotes macrophage survival in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(3):954–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Knight DA, L AS, Smyth MJ, Stewart TJ. A role for CCL2 in both tumor progression and immunosurveillance. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(7):e25474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes CS, Shicora AC, Keough MP, Snook AE, Burns MR, Gilmour SK. Polyamine-blocking therapy reverses immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(3):274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sauter M, Moffatt B, Saechao MC, Hell R, Wirtz M. Methionine salvage and S-adenosylmethionine: essential links between sulfur, ethylene and polyamine biosynthesis. Biochem J. 2013;451(2):145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Y, Niu Q, Shi C, Wang J, Zhu W. The role of microbiota in compensatory growth of protein-restricted rats. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10(2):480–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams JB, Aquino-Michaels K, Earley ZM, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zackular JP, Baxter NT, Iverson KD, Sadler WD, Petrosino JF, Chen GY, et al. The gut microbiome modulates colon tumorigenesis. MBio. 2013;4(6):e00692–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivanov II, Honda K Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(4):496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horinaka M, Yoshida T, Kishi A, Akatani K, Yasuda T, Kouhara J, et al. Lactobacillus strains induce TRAIL production and facilitate natural killer activity against cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(3):577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao J, Liu J, Xu R, Zhu X, Zhao X, Qian BZ. Prognostic role of tumour-associated macrophages and macrophage scavenger receptor 1 in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(47):83261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lo CH, Lynch CC. Multifaceted Roles for Macrophages in Prostate Cancer Skeletal Metastasis. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2018;9:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.