1. Introduction

With recent advances in technology and increased adoption of electronic health records (EHRs,) health care has the potential to be more integrated. Information can be shared across institutions and care can be coordinated between providers of various healthcare organizations. The introduction of EHRs has enabled the health delivery system to collect, store and share data on a scale much larger than possible with paper records. Privacy, therefore, has become an issue of paramount importance.1 In the absence of specific privacy-enhancing measures designed into electronic health record systems, individuals may note erosion of their privacy.

In its report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services, “Privacy and Confidentiality in the Nationwide Health Information Network,” the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) defined “health information privacy” as “an individual’s right to control the acquisition, uses, or disclosures of his or her identifiable health data.”2 Relatedly, the report differentiated “confidentiality” as referring to “the obligations of those who receive information to respect the privacy interests of those to whom the data relate.” Although one normally thinks of consent — the authorization by individuals for use of their medical information for any primary or secondary purpose — as an important aspect of privacy, obtaining explicit patient consent is not required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (“HIPAA”), according to 45 C.F.R. § 164.506(b). Moreover, HIPAA’s “Privacy Rule” does not define privacy other than by specifying the circumstances under which a “covered entity” (consisting of healthcare providers, insurers, and health records clearinghouses) may gather individually identifiable health information (termed “protected health information” or PHI) and the entities’ obligations to protect the privacy of that information.3 Presumably, a patient’s consent is implied by entering into the patient-caregiver relationship and being an insured. Obtaining explicit consent is optional for any covered entity, and they may use any form or format they choose, as far as HIPAA is concerned (45 C.F.R. § 164.506(b)). Many health care organizations follow some version of an opt-in or opt-out consent approach. For opt-in, patients need to sign a consent agreement that provides permission to share their PHI. If they do not provide consent, their PHI may not be shared. In an opt-out arrangement, if a patient doesn’t want PHI shared, they must sign an agreement that prohibits PHI sharing. If they don’t sign, their PHI may be shared.4

Our project, of which the study reported in this article is a part, seeks to better understand the extent and nature of patients’ desires not only to grant or withhold consent, but to exercise explicit and fine-grained control over disclosure of their personal healthcare information. Patient advocates, ethicists, policy makers, and informatics leaders have opined that patients should have greater ability to control the information in their EHRs. Granular consent models may offer a practical solution to support patients’ desire to have higher control over their data. For variety of reasons patients could decide to exert granular control over the information shared through consent. Patients may prefer to restrict access to their information, based on: (1) type and level of information, (2) set of individuals or entities that could have access to the information, (3) time frame and/or duration for which their information could be accessed, (4) purposes for which the information could be used.5 The Nationwide Privacy and Security Framework for Electronic Exchange (PSF) elaborates on principles that are expected to guide the actions of all health care-related persons and entities that participate in a network for the purpose of electronic exchange of individually identifiable health information.6 “The Individual Choice” principle of the PSF emphasizes that the opportunity and ability of an individual to make choices with respect to the electronic exchange of their individually identifiable health information is an important aspect of building trust. The PSF also recognizes that the options for expressing choice and the level of detail for which choice may be made will vary with the type of information being exchanged, the purpose of the exchange, and the recipient of the information. Fair Information Practices (FIPs) are the widely accepted framework of defining principles to be used in the evaluation and consideration of systems, processes, or programs that affect individual privacy. Based on FIPs, individuals should have access to their health information, knowledge of what is in their record, the ability to correct errors, control over whether information is collected and, if collected, for how long the information is stored, and know with whom the information is shared.7 Applying FIP principles to the sharing of EHRs will require balancing patient preferences, provider needs, and health care quality.

Privacy and Consent assume an even more significant role in behavioral health care. Behavioral health information is considered sensitive. According to the NCVHS categories of health information considered sensitive include: domestic violence, genetic information, mental health information, reproductive health, and substance abuse.8 There is also a stigma attached to behavioral care: many patients are hesitant to seek mental health treatment for fear of discrimination or social and financial harm.9 The opinions of patients about privacy, granular data control for care, and data sharing for research have recently been studied. Some studies differentiate sharing sensitive and non-sensitive medical information, but very little is known about data sharing choices of behavioral health patients.

One important objective of this study is to assess behavioral health patients’ opinions on selective control over their behavioral and physical health information. We explored behavioral health patient preferences regarding what health information should be shared for care and whether these preferences vary based on the sensitivity of health information and/ or the type of provider involved. We also examined behavioral health patients’ willingness to share PHI for research purposes.

An additional objective of this study was to solicit opinions of behavioral health providers on how they feel about patient-driven granular control of PHI, the implications for quality and continuity of care, and what barriers might be expected if an electronic patient-driven granular consent model is implemented.

2. Background

Mental illness and care in America is an important issue:10

45.6 million American adults (nearly one in five) suffer from a mental illness, 11.5 millions of whom have a serious mental illness. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines serious mental illness as having at least one mental disorder, other than a developmental or substance-use disorder, in the past 12 months that resulted in serious impairment.11 Serious mental illnesses include major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, and other mental disorders that cause serious impairment. SAMHSA also established a definition for any mental illness as having at least one mental disorder, other than a developmental or substance-use disorder, in the past 12 months, regardless of the level of impairment.

29% of all people with a physical health condition also have a behavioral health condition (define herein to include mental health and substance abuse disorder information).

68% of adults with a mental illness have at least one medical condition.

People living with a serious mental illness are nearly three times more likely to have diabetes and three times more likely to have chronic respiratory disease, compared to the general population.

People living with a serious mental illnesses have 3.5 times higher rates of emergency room visits, four times the rate of primary care visits, and five times the rate of specialist visits.

Behavioral health medications tend to have more drug-to-drug interactions and can have physical health-related side effects.

These statistics show how physical health and behavioral health are interrelated and how different providers could contribute to coordinated information sharing. Clinical trials that integrate behavioral and primary care models have shown improvements in physical health12 as well as mental health.13 As the 2012 Milliman report states cost effectiveness of integrated care models has been primarily studied by comparing the cost of behavioral integration efforts with cost reductions that were due to improved behavioral health of the patients.14 There has been little research contrasting overall healthcare cost of integrated versus non-integrated care. The report notes, however, that when total healthcare costs were compared, up to a 50% decrease in healthcare costs were reported. As it was also indicated in the report, an important limitation of existing studies is their duration. Most studies were six to 12 months long. Given the chronic nature of certain medical conditions and behavioral disorders, longer-term results of integration need to be studied.

Presently, Arizona’s statewide physical Health Information Exchange (HIE), known as “The Network,” is managed by the Arizona Health-e Connection (AzHeC). AzHeC is a non-profit, public-private partnership that “drives the adoption of health information technology and advances the secure and private sharing of electronic health information exchange.”15 AzHeC is an opt-out HIE, which means patients must consent for not sharing their information; otherwise they will be opted in. In Arizona, behavioral health information exchange is managed by a separate organization, the Behavioral Health Information Network of Arizona (BHINAZ). BHINAZ allows behavioral health providers in the network to access only behavioral health information (mental health and substance abuse disorder information) available from other members in the network.16 BHINAZ is an opt-in HIE, which means patients must consent for sharing their information; otherwise they will be opted out.17 Although no data sharing between BHINAZ and AzHeC is currently occurring, data use agreements are in process.

The goal of our research was to survey 50 behavioral patients from one of the outpatient behavioral health facilities at BHINAZ to understand their perceptions on the current opt-in consent model and their privacy preferences for data sharing for care and research. We also sought the opinion of 8 behavioral health providers from the same facility to capture their perceptions on the matter.

We implemented the patients’ surveys based on our review of relevant literature, which we summarize below:

Patients’ Perceptions on Data Sharing for Care and Research

Dimitropoulos et al. conducted a random-digit-dial telephone survey of 1847 U.S English-speaking adults in 2010 to determine public attitudes toward HIE. The authors concluded that greater participation by consumers in determining how health information sharing takes place could engender a higher degree of trust among all demographic groups, regardless of their level of privacy concerns. The authors noted that addressing the specific privacy and security concerns of minorities, individuals 40 to 64 years old, and employed individuals will be critical to ensuring widespread consumer participation in HIE.18

Dhopeshwarkar et al. conducted a study in 2012 to better understand consumer preferences regarding the privacy and security of HIE. The study was a random digit dial telephone survey of residents (N=170) in the Hudson Valley of New York State, a state where patients must consent to having their data accessed through HIE. Most consumers wanted any method of sharing their health information to have safeguards in place to protect against unauthorized viewing (86%). They also wanted to be able to see who has viewed their information (86%), to stop electronic storage of their data (84%), to stop all viewing (83%), and to select which parts of their health information are shared (78%). 78% wished to approve all information explicitly, and most preferred restricting information by clinician (83%), visit (81%), or information type (88%). (15). According to an American Medical News article “Ensuring that HIE standards and policies incorporate consumer preferences and expanding the scope of consumer engagement and education campaigns around an HIE will be key in gaining the public’s trust.”19

Caine et al. conducted a study in 2012 to ask patients if they wanted granular control over their medical records for care. Thirty adults receiving healthcare in central Indiana were recruited for the study. Patients fulfilled the following criteria: they were current or recent patients with health records in the Indiana Health Information Exchange, particularly those with highly-sensitive health information (Participants who had items in their own medical history that fell under one of the sensitive information categories of sexual activity, sexual orientation, sexually transmitted disease, adoptions, abortions, and infertility, were represented). The results of the study showed that patients want granular privacy control of their EHR data. The study also demonstrated that none of the participants wanted to share all of the information in their EHR with all potential recipients under all circumstances.20

The 2012 study “Who Do I Want to Share My Health Data With? A Survey of Data Sharing Preferences of Healthy Individuals” by Grando et al. examined research data sharing preferences of 70 healthy individuals from the University of California, San Diego campus. The results showed that respondents felt comfortable participating in research if they were given choices about which portions of their medical data would be shared, and with whom those data would be shared.21

The 2014 study “Patient preferences in controlling access to their electronic health records: a prospective cohort study in primary care” by Schwartz et al. examined patient preferences in controlling access to their EHR. Patients in a primary care clinic in Indianapolis were given the ability to control access to personal information stored in an EHR, based on the type of provider. Patients could restrict access to all personal data or to specific types of sensitive information, and could restrict access for a specific time period. Preferences were collected from 105 participants. 60 patients (57%) did not restrict access for any providers. Of the 45 patients (43%) who chose to limit the access of at least one provider, 36 restricted access only to all personal information in the EHR, while 9 restricted access of some providers to a subset of their personal information. Thirty-four patients (32.3%) blocked access to all their personal health information by all doctors, nurses, and other staff, and five (4.8%) denied access to all doctors, nurses, and staff.22

Patients’ Perceptions on Sharing Sensitive Data, Including Behavioral Health Data

In 2010 a study of 93 persons diagnosed with HIV/ AIDS was conducted to assess their attitudes towards having personal health information shared electronically. 84% of the individuals were willing to share their information with clinicians involved in their care. Willingness to share was positively associated with trust and respect of clinicians.23

Health Providers’ Attitudes and Feelings on Data Sharing

A statewide cross-sectional mail surveyed 1296 licensed physicians (77% response rate) in Massachusetts in 2007. It was to assess physician’s attitudes towards HIE. Overall, 70% indicated that HIE would reduce costs, while 86% said it would improve quality and 76% believed that it would save time. On the other hand, 16% reported being very concerned about HIE’s effect on privacy, while 55% were somewhat concerned and 29% not at all concerned.24

A 2011 survey by Patel et al. was conducted on 144 physicians to characterize their attitudes and preferences towards HIE and also to identify factors that influence physician’s interest in using HIE for their clinical work. Physicians expected HIE to improve provider communication (89%), coordination, and continuity of care (87%) and efficiency (87%). Physicians reported that technical assistance (70%) and financial incentives to use (65%) or purchase (54%) health IT systems would positively influence their adoption.25

In 2011 several focus groups were conducted to evaluate 29 physicians’ perceptions regarding the Arizona Medical Information Exchange (AMIE) impact on health outcomes and health care costs. The benefits most frequently mentioned during the focus groups included: identification of “doctor shopping”, averting duplicative testing and increased efficiency of clinical information gathering. The most frequent disadvantage mentioned was the limited availability of data in the AMIE system from patients participating in the exchange.26

A statewide survey of 2010 behavioral health providers (response rate 33%) was conducted in a Midwestern state in 2012 to learn about their beliefs regarding HIE. Providers were clustered into two groups based on their beliefs: a majority (67%) was positive about the impact of HIE, and the remainder (33%) were negative. Most behavioral health providers were supportive of HIE; however, their adoption and use of it may continue to lag behind that of medical providers due to perceived cost and time burdens and concerns about access to and vulnerability of information.27

A 2014 study was published focusing on provider response to patient controlled access to health records. An electronic tool was designed to capture patients’ preferences for provider access of their health information. Patients could allow or restrict providers’ access to all data (diagnoses, medications, test results, reports, etc.) or only highly sensitive data (sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS, drugs/alcohol, mental or reproductive health). Providers (8 clinic physicians and 23 clinic staff) could “break the glass” to display redacted information. Among the participants, 54% of providers agreed that patients should have control over who sees their EHR information, 58% believed restricting EHR access could harm provider-patient relationships and 71% felt quality of care would suffer. Patients frequently preferred restricting provider access to their EHRs. Providers infrequently overrode patients’ preferences to view hidden data. Providers believed that restricting EHR access would adversely impact patient care.28

Our literature findings indicate that patients wish to control the type of medical information shared and also with type of providers. The literature review also included providers’ perspectives on HIE. Physicians on one hand expected HIE to improve provider communication, coordination, and continuity of care and efficiency, but on the other had doubts about HIE’s effect on privacy. Physicians also felt that restricting provider access to the EHRs could harm the quality of care.

According to our literature review, very few studies were done searching the opinions and preferences of behavioral health patients and providers on sharing health information for care or research. This study is an effort to understand the preferences and concerns of these populations and determine patient preferences for sharing their behavioral health records for care and research with a variety of data recipients. This research also includes providers’ perspectives on how do they feel about the current broad consent process and their opinions on granular electronic consent.

3. Methods

3.1. Setting

Behavioral health patients receiving care at an outpatient behavioral healthcare facility in Arizona and behavioral health providers working at the same facility were included as participants in the study. The facility is part of BHINAZ and provides services to outpatients with behavioral health conditions and non-serious mental illnesses. Because the facility did not have an Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Arizona State University IRB reviewed and approved this study.

3.2. Participants

Fifty patients receiving behavioral healthcare were recruited for the Patient Survey. Study participants fulfilled the following criteria: 21 years or older, with a mental health diagnosis, and speak English. Participants who had serious mental illnesses were excluded from the study.

For the Provider Survey, we recruited 8 providers who worked with the patients at this behavioral healthcare facility. These include clinicians, case managers, therapists, and other providers currently involved in the patient consent process.

Of those patients and providers who responded to our recruiting flyers, 100% agreed to participate after learning more about the study.

3.3. Recruitment

Flyers soliciting patient participation were displayed in the waiting area at the healthcare facility. Interested participants contacted the reception desk staff, who informed the participants about the study using a script designed by researchers. These staff referred potential participants to the recruiters. The recruiters explained to the participants the purpose of the survey and its duration. The survey was implemented electronically using a tablet. After obtaining the consent from the patients, the tablets containing the Patient Survey were given to the participants. The recruiters were available to answer questions from the participants. Completing the surveys took an average of 15 minutes and participants were compensated for their time with a $20 gift card.

For the Provider Survey, the management at the institution informed the providers about the study. The interested providers were contacted by e-mail and sent a consent form that was signed and returned electronically. Those who signed the consent were sent a link to an electronic survey. The participants received a $30 electronic gift card when the survey was completed.

3.4. Questionnaire

The Patient Survey (Appendix) included questions regarding their demographics and about their concerns and preferences for data sharing for care and research. Participants could answer questions by selecting between one or multiple answers. For some questions, the option “Other” allowed participants to write a justification for their choices.

The Provider Survey (Appendix) included questions about their view on the current consent process and perceptions on barriers to implement patient-controlled granular consent models. Providers were asked to write their answers. For some questions we chose to ask about similar topics for both the Provider and Patient Surveys to compare their opinions. The common topics asked to both patients and providers included:

Opinions on the current broad consent process. (Q7 for patients, and Q3 and Q4 for providers)

Reasons for patients to share or not share their medical records. (Q11 for patients, and Q7 for providers)

Do patients engage in discussions with providers about positive and negative consequences of sharing and not sharing? (Q8 for patients, and Q5 for providers)

3.5. Data Analysis

A quantitative data analysis was performed on the Patient Survey, using the SAS 9.4 software,29 to obtain frequencies and percentages for each response and to test for relationships among responses.

The Coding Analysis Toolkit (CAT)30 for qualitative data analysis was used to interpret the results of the Provider Survey and to identify the main themes in the survey.

4. Results

4.1. Patient Survey:

DEMOGRAPHICS

A total of 50 patients participated in the study and the demographic characteristics of the survey participants are summarized in Table 1 (Q1-Q5). Our sample was 84% female and 16% male. Nationally the prevalence of mental illness is 22.3% among females and 14.4% among males. In our survey females are over represented, in the age group of 21–30 years. More than half (30) of the participants were White non-Hispanic race (60%) and the rest were Hispanic (26%) or multiracial (8%). Nationally the prevalence of mental health illness is 19.3% among White, 16.9% among Hispanic, 16.9% among African-American and 12.3% in Asian. Most of the study population attended some college or high school and reported an annual income of less than $10,000. According to the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) mental illness is more prevalent in females, in the age group 18–50 and in White, Hispanic, and Black populations.31 Our study demonstrates a preponderance of female and white patients when compared to national data.

Table 1.

Demographics of Survey Participants

| Category | Responses (n=50) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 8 (16%) |

| Female | 42 (84%) |

| Age | |

| 21–30 | 14 (28%) |

| 31–40 | 12 (24%) |

| 41–50 | 7 (14%) |

| 51–60 | 11 (22%) |

| 61–70 | 5 (10%) |

| > than 70 | 1 (2%) |

| Education | |

| Attended to high school but did not graduate | 4 (8%) |

| High school graduate | 13 (26%) |

| Some college | 23 (46%) |

| College graduate | 6 (12%) |

| Attended or completed graduate or professional school | 4 (8%) |

| Race | |

| White non-Hispanic | 30 (60%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 13 (26%) |

| African American | 3 (6%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) |

| Multi-racial | 4 (8%) |

| Household income | |

| $0–10000 | 19 (38%) |

| $10001–20000 | 9 (18%) |

| $20001–30000 | 10 (20%) |

| $30001–40000 | 4 (8%) |

| $40001–50000 | 4 (8%) |

| $>50000 | 4 (8%) |

Table 2 shows the diagnoses of the patients in the study population (self-reported by patients in Q6). The most common diagnoses of our study population are Anxiety and Panic disorder and Mood disorder.

Table 2.

Distribution of Behavioral Health Diagnoses of the Survey Participants

| Disorder | Responses |

|---|---|

| Anxiety and Panic Disorder | 76% |

| Mood disorder | 68% |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 26% |

| OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) | 22% |

| ADHD (Attention Deficient Hyperactivity Disorder) |

10% |

| Drug or Substance Abuse | 10% |

| Eating Disorder | 6% |

| Personality Disorder | 6% |

| Psychotic Disorder | 4% |

DATA SHARING PREFERENCES OF PARTICIPANTS FOR CARE

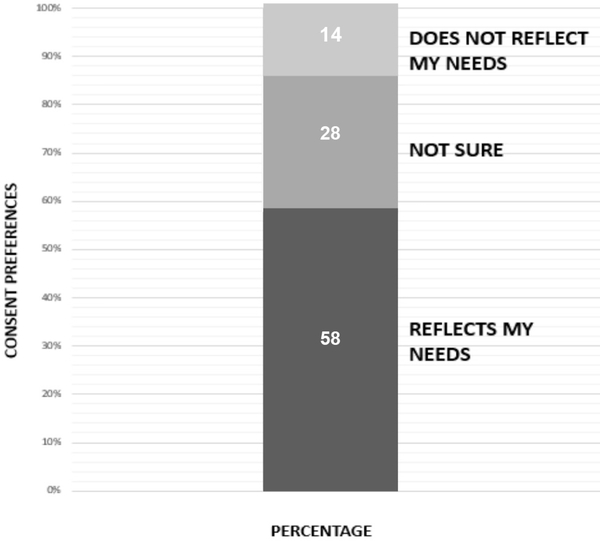

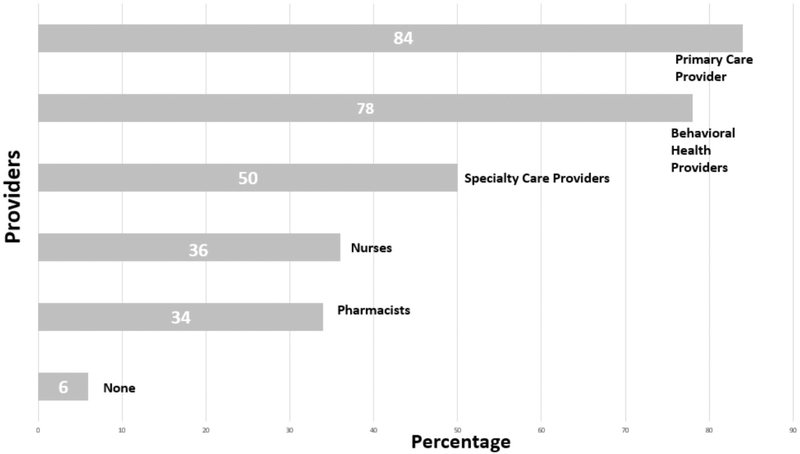

Figure 1 (Q7) demonstrates that a majority of participants (58%) feel the current broad consent choices (share all or none of the information) reflect their needs, while 28% were “Not sure.” This lack of knowledge or indecision may indicate need for further education on consent options. While participants expressed that the current broad consent process reflects their needs, if given a choice they would like to control which providers they share their data with. Figure 2 (Q9) shows that participants do not have the same sharing desires for all providers and there is not one recipient (e.g., primary care physician) with whom all patients wanted to share all of the information in their EMR. While more than half of participants would share all their health information with primary physicians and behavioral health providers, less than half would share that information with specialty care providers, pharmacists and nurses. This suggests that participants desire granular control over who can access their data for care.

Figure 1.

Chart Showing the Survey Participants Opinions on the Current Broad Consent Process

Figure 2.

Types of Providers with Whom Participants Wish to Share Their Medical Information

REASONS FOR DECIDING TO SHARE OR NOT SHARE FOR CARE

Table 3 (Q10) and Table 4 (Q11) show the reasons participants expressed about why they want or do not want to share their medical information for care. Participants wanted to share their medical information because they wanted to improve the quality and coordination of their care. Trust of the providers was also an important consideration for participants who decided to share. In fact, we found from our informal interactions with study participants that “trust” was an important motivation for data sharing. One of the main reasons for not sharing their records was fear of stigma or discrimination.

Table 3.

Reasons Why Participants Want to Share Medical Information

| Reasons to Share Information with Providers for Care | Responses |

|---|---|

| Improve quality of care | 75% |

| Coordinate care | 52.1% |

| Trust providers | 45.8% |

| Feel pressure to share records when a provider asks me for consent | 6.3% |

Table 4.

Reasons Participants Do Not Want to Share Medical Information

| Reasons To Don’t Share Information With Providers For Care | Responses |

|---|---|

| I want to share, I am not worried | 42% |

| Worried that non-behavioral health providers might treat differently/ discriminate against if they knew my behavioral health conditions | 40% |

| Worried about losing privacy | 28% |

| Worried that other people, like employers, may have access to information | 20% |

DATA SHARING PREFERENCES OF PARTICIPANTS FOR CARE

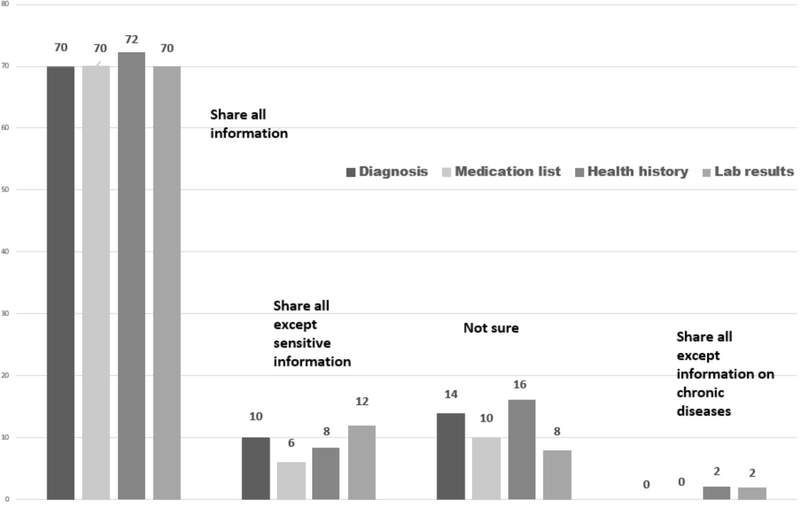

For the questions involving the type of medical information that a patient might share, we identified four main categories: Medication list, Laboratory results, Medical Diagnoses, and Medical history. We subdivided these into sensitive or non-sensitive information. We used the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics definition for sensitive information.32 For example, we asked participants whether they would like to share their entire medication list or would like to restrict based on medications for their chronic conditions or medications for their behavioral or sexual conditions. The results in Figure 3 (Q12, 13, 14 and 15) show 70% of the patients want to share all their information (Medication list, Laboratory results, Medical Diagnoses, and Medical history). The results also demonstrate that participants are least concerned about sharing information about their chronic conditions.

Figure 3.

Sharing Preferences of Participants Based on the Type of Medical Information

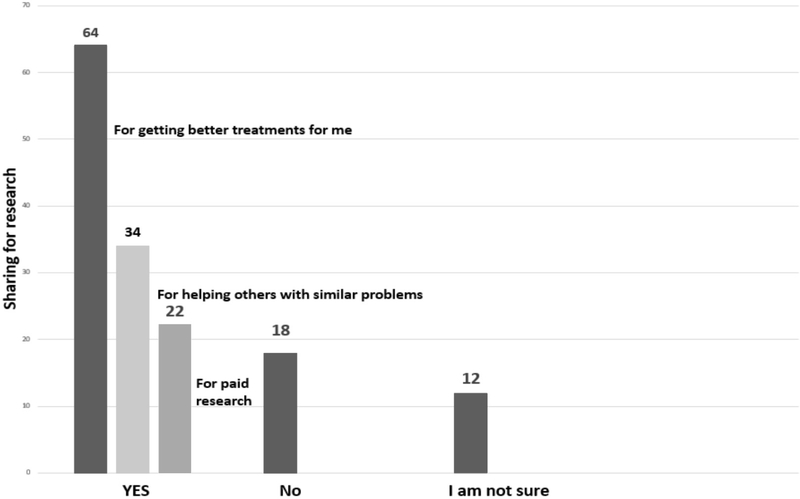

DATA SHARING PREFERENCES OF PARTICIPANTS FOR RESEARCH

According to Figure 4 (Q16) participants want to share their medical information for research mainly if the research is for the conditions they are diagnosed with, or it might help them or others diagnosed with similar conditions. They would also share data for research if they are compensated for the research participation.

Figure 4.

Reasons for Participants Sharing Medical Information for Research

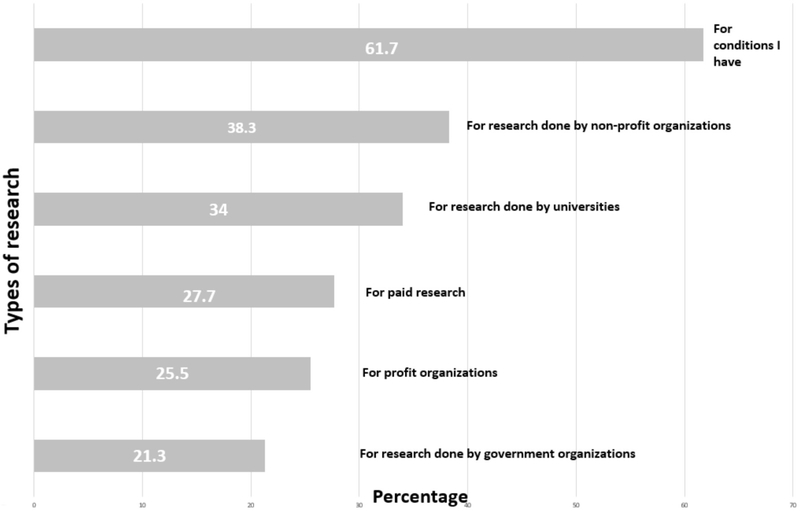

From Figure 5 (Q17) we can infer that the type of research that participants would like to contribute to is highest for the conditions they have and for research done by non-profit organizations, and least if the research is done by government agencies. As Table 5 (Q18) depicts, the main concern for participants for not sharing their medical records for research is the fear of losing their privacy.

Figure 5.

Participant Preferences for Types of Research to Which They Would Like to Contribute

Table 5.

Concerns of Participants Related to Sharing Their Data for Research

| Reasons To Don’t Share Information For Research | Responses |

|---|---|

| Worried about losing privacy | 40% |

| Worried about government agencies having access to records | 28% |

| Worried about insurance companies having access to records | 26% |

| Worried that information may be used by for-profit companies | 24% |

STATISTICAL DATA ANALYSIS

In addition to the descriptive statistics provided in Tables 1–5 and Figures 1–5, the influence of diagnosis on the consent choices and effect of race, age, gender, and income on the consent choices were analyzed. There were no statistically significant results.

4.2. Provider Survey

Eight providers are involved in the study and the job titles of them include Clinician (3), Therapist (3), Treatment Coordinator (1) and Doctor of Nursing Practice (1). This distribution reflected a representative sample of provider types involved in the facility consent process.

The responses of the providers were coded to identify the main themes they expressed. The main themes identified were:

The current consent process is broad and does not reflect patient choices.

The most common reasons given by patients for not sharing medical records are stigma attached to behavioral health diagnoses and treatment and fear of misuse of their data

The time required to implement consent and educate patients who are not computer savvy is a potential barrier to implementing a granular consent process.

It is important to educate clinicians about possible benefits and harms of data sharing to better educate patients.

The summary of providers’ responses is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of Providers’ Responses to the Survey Questions

| Question/ Responses | Comments |

|---|---|

|

Do you feel that the current broad consent model of either “sharing all clinical information with all providers” or “sharing no clinical data with any provider” for care or for research matches patients’ desires? (Q3) Most (7/8) providers feel that the consent process is broad and does not reflect patient’s needs. |

“…about a third [of patients]do not want their information in a data base for coordination of care. Almost all are ok with sharing minimal information with their PCP.” |

|

Do you have past experiences of patients complaining that the current consent process is too broad and that they would like more control over what they share and with whom? (Q4) Half of the providers (4/8) responded that patients usually do not complain and accept the current broad consent forms. |

“They [patients] rely on clinicians to help look out for their best interest.” |

|

Do patients ask during the consent process to be informed about or wish to discuss possible positive and negative effects or consequences of sharing medical information for care or for research? (Q5) Most (7/8) replied that patients rarely ask for effects or consequences. |

“Very rarely. They [patients] generally want their medical providers to be on the same page with each other. Especially if there are medications involved in treatment.” |

|

Besides the information contained in the consent form used for asking patients permission to share their data for care and research, do you provide any additional resource to educate patients on their choices (video, pamphlets, web site, etc.)? (Q6) Most (6/8) replied no. |

“…printouts attached to the electronic consent form, which have a bit more information that they can read up on or research. But in general it’s just the consent/release form that they sign and receive a copy of.” |

|

What are some of the most common reasons given by patients who decide to restrict sharing of their clinical data for care or for research? (Q7) Stigma (4/8), fear of misuse of information (2/8) and loss of privacy (2/8) are common reasons given by patients. |

“Clients [patients] do not want the information made available to others because of the stigma of having a mental health diagnosis.” “…if medications were restricted by one provider they [patients] don’t want that influencing another provider’s decision to prescribe.” |

|

What are some of the most common reasons given by patients who decide to share their clinical data for care or for research? (Q8) Coordination of care (2/8), improve quality of care (2/8) |

“..they [patients] often want everyone to be on the same page, especially with medications. They don’t want to “start over” as often there are years of treatment provided elsewhere, and they want their new provider to be informed.” |

|

Do you think that (some of) your patients could be subject to bias when treated by other providers if the provider knew about the patient’s behavioral health conditions or other sensitive information in their history? (Q9) Yes (8/8) |

“There could be a bias if a provider was aware of a client using substances which may explain the behaviors.” |

|

Do you think that a patient’s care would be negatively affected if not all the clinical information is provided to other health care providers outside BHINAZ? (Q10) Majority (6/8) felt that care could be negatively affected. |

“Possibly. For example not to include their [patients] substance use history simply because they are in recovery may be a problem for a medical provider prescribing, or another therapist missing signs of relapse.” |

|

Do you have suggestions on how to best educate patients on the positive/negative effects and consequences of restricting or permitting sharing of their clinical information? (Q11) Verbal explanation (3/8), print-outs (2/8), educating clinicians (1/8), multi-media options (1/8) |

“the more important factor is educating clinicians. For the most part, clients will sign whatever is put in front of them. It is a clinician’s job to be the gatekeeper and help clients to understand both positive and negative implications of their decisions.” “Possibly Multi-media options — websites to read, or to show a short video-taking into consideration all learning types.” |

|

Do you think that your institution could benefit from knowing more about patients’ choices on data sharing? (Q12) Yes (6/8) Uncertain (2/8) How can your institution benefit? (Q12) Understanding patients preferences (4/8) Educating clinicians (2/8) |

“Understanding our client’s preferences would foster understanding, trust, and respect, perhaps lead to agency changes to better match client preferences, and in turn would increase the level of integrity of the agency.” |

|

Do you anticipate barriers to implementing an electronic consent process that would give patients more options on the types of information they wish to share and with which other care providers? (Q13) Time (3/8), educating clinicians (2/8), educating patients who have minimum knowledge of computers(2/8) |

“The barriers envisioned would be time. Intake form consists of approximately 11 pages of intake questions in addition to another 8 forms that need to be explained and/or signed. Clients are generally overwhelmed and anxious by the process to some degree. Having another form for the client to complete seems like a lot.” “If they [patients] are given more choices it could complicate coordination of care and can be more time consuming. Patients may want to withhold consent of care yet not realize those implications in providing thorough care and could limit amount of assistance.” |

5. Discussion

Our study examined behavioral health patient preferences regarding sharing their electronic health record data for care and research. More than half of the participants (58%) expressed that the current broad consent process generally reflects their needs (Figure 1). Although most participants wanted to share with primary care providers (84%) and with behavioral health providers (78%), they desired greater levels of granularity to restrict access to some information by specialty care providers (50%), nurses (36%), pharmacists (34%), or all types of providers (6%) (Figure 2). When they expressed concerns on sharing data, the main reason given was fear of stigma or discrimination (40%) (Table 4). The majority (70%) of our behavioral health participants expressed the desire to share all information, including sensitive information, for Diagnoses, Medical history, Lab results, and Medication list (Figure 3). For research, 64% of the participants would share their medical information if it might help them get better treatments for their personal conditions (Figure 4).

There are very few preexisting studies specifically addressing data sharing preferences of behavioral health patients. The lack of those studies makes it difficult to fully compare our results. Furthermore, as described in the Demographics section, our sample did not fully represent the prevalence of behavioral conditions nationwide. However, when we contrast our results to studies from patients without behavioral conditions, some of those studies have reported that patients want more control over their data based on the type of information (e.g., lab test results) and recipient (e.g., primary care provider).33 Those studies have shown that patients with and without sensitive information prefer to restrict the sharing of sensitive versus less-sensitive EHR information. Their results may differ from our findings in the behavioral health population. In our study, the majority of participants (70%) wanted to share all information, sensitive and non-sensitive, though they would prefer to have control over the type of providers accessing the data. These results may be due to the behavioral health environment or our sample. Our perception is that study participants had a high level of trust in their behavioral health providers and they were therefore willing to share all the data with the facility providers. It could also be the case that some questions (Q12, Q13, Q14 and Q15) could benefit from further explanations. Many participants during the survey asked researchers “What do you mean by share data with the care team? Do you mean the providers here or somewhere else?” An introduction to BHINAZ and opt-in data sharing models may have helped patients to better understand the survey context.

Based on preliminary research on patients’ privacy preference,34 we expected behavioral health patients to have more reservations about sharing their data and expressing the desire for more data sharing choices than the ones provided by the current broad consent models. Our results did not bear out this expectation initial: 58% of the participants expressed that the current broad consent process reflects their needs, 70% of the participants wanted to share all their information, both sensitive and non-sensitive.

For several questions we received a rather high number of unsure responses (Q7– 28%, Q12–14%, Q13–10%, Q14–16%, Q15– 8%, Q16– 22%, Figures 1, 3, 4.) These results may reflect patient lack of understanding, indecision, or the need for further education on consent options for data sharing. Future studies may seek understand the nature and causes of the uncertainty, perhaps to find ways to help patients resolve those uncertainties. In particular, the discrepancy between 58% of participants staying that the current broad consent process reflects their need and a high percentage of patients wanting to have more control over the type of provider who has access to the data (Figure 2) could reflect lack of clear understanding of the data sharing implications of the current broad consent model.

We complemented the patient perspectives with provider perspectives about patient-driven granular control, implications for quality and continuity of care, and what barriers might exist if an electronic patient-driven granular consent model is implemented. As reported in Table 6, there is a tension between the providers opinions; on one hand most provider (87.5%) felt that patients should have more choices for controlling the access to their medical data, on the other hand the majority (75%) felt that care could be negatively affected when patients restrict access to relevant clinical information. While they thought that patient choice should expand, they also felt that educating patients (25%) and more importantly, educating the providers (25%) about the positive and negative aspects of granular control is essential to better help patients make informed decisions. Over a third (37.5%) of the behavioral health providers in our study identified “time” as the most significant barrier in implementing a system that permits more granular control of PHI by patients.

Our patient and provider surveys contained a series of similar questions regarding the current broad consent process, reasons for sharing and not sharing medical information and, patients’ and physicians’ perspectives on the positive and negative consequences of data sharing. Comparing the responses, as summarized in Table 7, yielded additional insights. Providers and patients agree that the main reason that behavioral health patients wish to restrict some provider and data types is stigma, followed by loss of privacy and fear of misused of information. Both study participants and providers felt that coordination of care, followed by improvement in quality of care and trust in providers are the main reasons for behavioral health patients to share medical data for care. Interestingly, while providers felt that current consent choices (share all or none of the information) are too broad, most patients (58%) expressed that the current choices adequately reflected their needs.

Table 7.

Comparison of Patients and Providers Views

| Question | Responses |

Provider Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Does the current consent process reflect patient needs? (Q7 for patients and Q3 and Q4 for providers) | “I like that clients [patients] can opt in or opt out of the Health Exchange Information form. I feel clients [patients] should have the option, some prefer sharing all information; some prefer individual release of information as needed. “ |

|

|

Do patients discuss the positive and negative consequences of sharing information? (Q8 for patients and Q5 for providers) |

“My experience is that clients [patients] rarely ask for effects or consequences. In my presentation and explanation I offer an example of positive and negative possibilities.” | |

| Reasons for not sharing the medical information for care (Q11 for patients and Q7 for providers) |  |

“Patients do not want others to think they are “crazy” or know other things about them they view as being negative.” “That they [patients] want to keep their information private, personal. Certain diagnosis can affect life insurance eligibility.” |

| Reasons for sharing the medical information for care (Q10 for patients and Q8 for providers) |  |

“Patients sometimes say ‘Don’t care, why not’ ‘If you [providers] think it is a good idea.” “For care: their reasons would be to increase efficiency for their care by making the sharing of records more simple, and less repetition of evaluations.” |

From the study, we can infer that patients desire greater control over the type of providers accessing the data. Stigma and discrimination from providers unrelated to the treatment of behavioral health conditions was mentioned as an important reason to restrict access to data. Improving quality and continuity of care was the main motivation for patients to share clinical information with providers. But asking patients to select what they want to share for all potential recipients may prove to be overwhelming and even detrimental. For example, a patient might wish to restrict his/her cardiologist from seeing information regarding previous psychiatric treatment, but this could lead to potential drug interactions. Or an individual who abuses painkillers might wish to block access to his/her abuse history. Patients may believe they have sound justification for exercising control, citing, for example, potential discrimination, but there may be significant consequences, particularly in the area of drug interactions. This highlights a finding noted in the Provider Survey that patients need a better understanding of the information that exists in their medical record, who may view it, and how this information is used and disclosed. Only then will they be empowered to make an informed choice about granular control. The surveyed providers recommended that as patients are educated about granular consent, so should the care team be. Without such shared knowledge and understanding, the opportunity for patients to exercise granular control risks leading to more harm than good.

6. Conclusion

This study captured the opinions of both behavioral health providers and patients about consent preferences and granular data sharing for care and research. This study shows that patients may wish granularity over who can access their personal health data. While the behavioral health providers feel comfortable with patient driven granular control, they also express caution and see a need for educating patients along with the providers to help patients make informed decisions. While previous studies have focused on general data sharing preferences and the differences between sharing sensitive vs. non-sensitive information, this study is one of few that focuses on the preferences of patients with behavioral health conditions. While the sample size of this study is modest to yield statistically significant results and excludes individuals with serious mental illnesses, it provides valuable preliminary data that can help guide further studies. Understanding the consent preferences and needs of those with behavioral health conditions, is an important focus area for new research.

One important objective of this study is to assess behavioral health patients’ opinions on selective control over their behavioral and physical health information. We explored behavioral health patient preferences regarding what health information should be shared for care and whether these preferences vary based on the sensitivity of health information and/ or the type of provider involved. We also examined behavioral health patients’ willingness to share PHI for research purposes.

From the study, we can infer that patients desire greater control over the type of providers accessing the data. Stigma and discrimination from providers unrelated to the treatment of behavioral health conditions was mentioned as an important reason to restrict access to data. Improving quality and continuity of care was the main motivation for patients to share clinical information with providers.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by “My Data Choices, evaluation of effective consent strategies for patients with behavioral health conditions” (1 R01 MH108992–01), funded by the National Institute for Mental Health.

APPENDIX

Patient Survey

Questions regarding yourself

-

How old are you?

21–30

31–40

41–50

51–60

61–70

Older than 70

-

What is your gender?

Male

Female

Other

-

What is your highest education level?

Attended to high school but did not graduate

High school graduate

Some college

College graduate

Attended or completed graduate or professional school

-

What is your race or ethnicity?

White non-Hispanic

Hispanic or Latino

African American

Asian

Multi-racial

What is the approximate income of your household? ______________________

- What behavioral health conditions have you been diagnosed with? Select all that apply.

Anxiety or Panic Disorder Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Eating Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Drug Abuse or Substance Abuse Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Personality Disorder Psychotic Disorder (like Schizophrenia) Mood Disorder (like Depression or Bipolar Disease) Impulse Control or Addiction Disorder (like problems with gambling or sex) Others:

Questions about sharing your medical records for care

-

7.

Right now you can consent to share “all” or “none” of your medical information. What are your feelings about the current process for giving your consent to share your medical information? Choose one best answer.

The consent process reflects my needs

The consent process does not reflect all my needs. I’d like more choices

I am not sure

-

8.

Do you recall having a discussion with your providers about the positive and negative aspects of sharing your medical information? Choose one best answer.

Yes, more than once

Yes, once

No, never

I do not remember

-

9.

I want to share my medical information with … Select all that apply.

Primary Care Providers (PCP) (like your physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant)

Behavioral Health Providers (like your psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, counselor or therapist)

Specialty Care Providers (like your cardiologist, dermatologist)

Pharmacists

Nurses

None of the above (Then skip to Question 11)

-

10.

I want to share my medical information with my providers because… Select all that apply.

I trust my providers

I think that for regular care, providers should know as much about me as possible to make decisions

I think that during an emergency, providers should know as much about me as possible to make decisions

I feel pressure to share my records when a provider asks me for consent

Other: _________________________________________________

-

11.

I don’t want to share my medical information with my providers because…Select all that apply.

I am worried about losing my privacy

I am worried that other people, like my employer, may have access to my information

I am worried that non-behavioral health providers might treat me differently if they knew my behavioral health conditions

I am worried that non-behavioral health providers might discriminate against me if they knew my behavioral health conditions

Other: _________________________________________________

Questions about sharing specific types of your medical information for care

-

12.

Would you like to share your health diagnoses and medical problems with your care team? Select all that apply.

Yes, I want to share all of my diagnoses and medical problems

Yes, except diagnoses of my chronic conditions (like Diabetes, Hypertension and Asthma)

Yes, except diagnoses of my sexual related conditions (like HIV, Syphilis and Impotence)

Yes, except diagnoses of my behavioral health conditions

No, I do not want to share any diagnosis or problem

I am not sure

-

13.

Would you like to share your medication list? Select all that apply.

Yes, I want to share all of my medications

Yes, except medications for my chronic conditions

Yes, except medications for my sexual related conditions

Yes, except medications for my behavioral health conditions

No, I do not want to share my medication information

I am not sure

-

14.

Would you like to share your health history? Select all that apply.

Yes, I want to share all of my health history

Yes, except history of my chronic conditions

Yes, except history of my sexual related conditions

Yes, except history of my behavioral health conditions

No, I do not want to share my history of health conditions

I am not sure

-

15.

Would you like to share your laboratory results? Select all that apply.

Yes, I want to share all of my labs

Yes, except labs about my chronic conditions

Yes, except labs about my sexual related conditions

Yes, except labs about my behavioral health conditions

No, I do not want to share my labs results

I am not sure

Questions about sharing medical information for research

-

16.

Would you like to share your medical information for research? Select all that apply.

Yes, research might help me get better treatments

Yes, research might help others with similar health problems

Yes, if I get paid for participating in the research

No, I do not want to share my medical information for research (If No, Skip to Question 18)

I am not sure

-

17.

If you wish to share your information for research, it applies to… Select all that apply.

Research for health conditions I have

Research done by for-profit organizations (like pharmaceutics companies)

Research done by non-profit organizations

Research done by government organizations

Research done by universities

Any research, if I am paid

I am not sure

-

18.

If you do not want to share your medical information with some researchers, why? Select all that apply.

I am worried about losing my privacy

I am worried that insurance companies may have access to my medical information

I am worried that for-profit companies may use my medical information

I am worried that the government may have access to my medical information

Other reasons: ___________________________________________

Provider Survey

What is your job title at the Jewish Family and Children’s Services Mesa care facility?

-

Are you currently involved in the consent process of the patient or have been involved in consent processes in the last year?

Yes

No

Do you feel that the current broad consent model of either “sharing all clinical information with all providers” or “sharing no clinical data with any provider” for care or for research matches patients’ desires?

Do you have past experiences of patients complaining that the current consent process is too broad and that they would like more control over what they share and with whom?

Do patients ask during the consent process to be informed about or wish to discuss possible positive and negative effects or consequences of sharing medical information for care or for research?

Besides the information contained in the consent form used for asking patients permission to share their data for care and research, do you provide any additional resource to educate patients on their choices (video, pamphlets, web site, etc.)?

What are some of the most common reasons given by patients who decide to restrict sharing of their clinical data for care or for research?

What are some of the most common reasons given by patients who decide to share their clinical data for care or for research?

Do you think that (some of) your patients could be subject to bias when treated by other providers if the provider knew about the patient’s behavioral health conditions or other sensitive information in their history?

Do you think that a patient’s care would be negatively affected if not all the clinical information is provided to other health care providers outside BHINAZ? Please give concrete examples, if possible.

Do you have suggestions on how to best educate patients on the positive/negative effects and consequences of restricting or permitting sharing of their clinical information?

Do you think that your institution could benefit from knowing more about patients’ choices on data sharing? How can your institution benefit?

Do you anticipate barriers to implementing an electronic consent process that would give patients more options on the types of information they wish to share and with which other care providers? What sort of barriers?

Footnotes

In memoriam

We wish to honor the memory of Michael Zent who recently passed away. Dr. Zent was an enthusiastic advocate for behavioral health patients and a visionary leader in behavioral health information technologies in Arizona.

Contributor Information

Maria Adela Grando, Arizona State University Department of Biomedical Informatics and Adjunct Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine..

Anita Murcko, Arizona State University Department of Biomedical Informatics..

Srividya Mahankali, Biomedical Informatics Master student, Arizona State University.

Michael Saks, Law and PsychologyArizona State University Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law..

Michael Zent, Topaz Information Solutions, LLC, Jewish Family and Children’s Services Phoenix, and Behavioral Health Information Network of Arizona (BHINAZ)..

Darwyn Chern, Clinical Services and Recovery, LLC..

Christy Dye, Recovery, LLC..

Richard Sharp, Mayo Clinic Biomedical Ethics Program, the Center for Individualized Medicine Bioethics Program and the Clinical and Translational Research Ethics Program..

Laura Young, BHINAZ..

Patricia Davis, Biomedical Informatics Arizona State University..

Megan Hiestand, Biomedical Informatics undergraduate student at the Arizona State University.

Neda Hassanzadeh, Biomedical Informatics Arizona State University..

References

- 1.Hirsch MD, “Patients Want ‘Granular’ Privacy Control of Electronic Health Info,” FierceEMR, available athttp://www.fierceemr.com/story/patients-want-granular-privacycontrol-electronic-health-info/2012-11-28 (last visited May 24, 2017); Barrows RC and Clayton PD, “Privacy, Confidentiality, and Electronic Medical Records,” JAMIA 3, no. 2 (1996): 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCVHS for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Privacy and Confidentiality in the Nationwide Health Information Network,” available at http://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/recommendations-reports-presentations/june-22-2006-letter-to-the-secretary-recommendations-regarding-privacy-and-confidentiality-in-the-nationwide-healthinformation-network/ (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services, “Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule,” available at http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/ (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 4.“Consumer Consent Options for Electronic Health Information Exchange: Policy Considerations and Analysis,” available at https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/choicemodelfinal032610.pdf (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 5.Dhopeshwarkar RV, Kern LM, O’Donnell HC, Edwards AM, and Kaushal R, “Health Care Consumers’ Preferencesaround Health Information Exchange,” Annals of FamilyMedicine 10, no. 5 (2012): 428–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; “Patients Seek StrongSay in How Their Data Are Used,” available at http://www.amednews.com/article/20121003/business/310039997/8/(last visited May 24, 2017).Id.;

- 6.“Nationwide Privacy and Security Framework for Electronic Exchange of Individually Identifiable Health Information,” available at https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nationwide-ps-framework-5.pdf/ (last visited May 24, 2017);

- 7.“Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs),” available at http://www.nist.gov/nstic/NSTIC-FIPPs.pdf/ (last visited March 4, 2016); “Fair Information Practice,” available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FTC_Fair_Information_Practice,” (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 8.NCVHS for the US Department of Health and Human Services, “Recommendations on Privacy and Confidentiality 2006–2008,” available athttp://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/privacyreport0608.pdf (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 9.Association for Psychological Science, “Stigma as a Barrier to Mental Health Care,” available athttp://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/releases/stigma-as-a-barrierto-mental-health-care.html (last visited May 24, 2017); Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, Weich S, and King M, “Stigma: the Feelings and Experiences of 46 People with Mental Illness,” British Journal of Psychiatry 184, no. 2 (2004): 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.OPEN MINDS, “The Current State of Sharing Behavioral Health Information in Health Information Exchanges,” available at https://www.openminds.com/market-intelligence/resources/current-state-sharing-behavioral-health-information-health-information-exchanges.htm/ (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” available at <http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf (last visited May 24, 2017). [PubMed]

- 12.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, and Rosenheck RA, “Integrated Medical Care for Patients with Serious Psychiatric Illness: A Randomized Trial,” Archives of General Psychiatry 58, no. 9 (2001): 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, Bruce ML, Katz IR, Raue PJ, Mulsant BH, Oslin DW, Ten Have T, and PROSPECT Group, “Reducing Suicidal Ideation and Depression in Older Primary Care Patients: 24-Month Outcomes of the PROSPECT Study,” American Journal of Psychiatry 166, no. 8 (2009): 882–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Noël PH, Lin EHB, Areán PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C, and IMPACT Investigators, “Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment, “Collaborative Care Management of LateLife Depression in the Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” JAMA 288, no. 22 (2002): 2836–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melek SP, “Bending the Medicaid Healthcare Cost Curve through Financially Sustainable Medical-Behavioral Integration,” Milliman (July 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.“Arizona Health e-Connection. The Right Information to the Right Person, at the Right Time, for the Right Purpose,” available at http://www.azhec.org/ (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 16.“Behavioral Health Information Network of Arizona,” available at http://www.bhinaz.com/index.php (password protected; last visited March 4, 2016).

- 17.“Behavioral Health Information Network of Arizona, Consent Model Opt-In Versus Opt-Out,” available at http://www.bhinaz.com/index.php/consent-model (password protected;last visited March 4, 2016).

- 18.Dimitropoulos L, Patel V, Scheffler SA, and Posnack S, “Public Attitudes toward Health Information Exchange: Perceived Benefits and Concerns,” American Journal of Managed Care 17, Spec. No. 12 (2011): SP111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.See Dhopeshwarkar, supra note 5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caine K and Hanania R, “Patients Want Granular Privacy Control over Health Information in Electronic Medical Records,” JAMIA 20, no. 1 (2013): 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell EA, Ohno-Macahdo L, and Grando MA, “Sharing My Health Data: A Survey of Data Sharing Preferences of Healthy Individuals,” presentation at the American Medical Informatics Association Conference, Washington, D.C., November 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz PH, Caine K, Alpert SA, Meslin EM, Carroll AE, and Tierney WM, “Patient Preferences in Controlling Access to Their Electronic Health Records: A Prospective Cohort Study in Primary Care,” Journal of Internal Medicine 30, Suppl. 1 (2015): S25–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira PA, Gordon P, Camhi E, and Bakken S, “HIV Patients’ Willingness to Share Personal Health Iinformation Electronically,” Patient Education and Counseling 84, no. 2 (2011): e9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright A, Soran C, Jenter CA, Volk LA, Bates DW, and Simon SR, “Physician Attitudes toward Health Information Exchange: Results of a Statewide Survey,” JAMIA 17, no. 1 (2010): 66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V, Abramson EL, Edwards A, Malhotra S, and Kaushal R, “PHysician’s potential use and preferences related to health information exchange”. Int J Med Inform (2011): 80(3):171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hincapie AL, Warholak TL, Murcko AC, Slack M, and Malone DC, “Physicians’ Opinions of a Health Information Exchange,” JAMIA 18, no. 1 (2011): 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shank N, “Behavioral Health Providers’ Beliefs about Health Information Exchange: A Statewide Survey,” JAMIA 19, no. 4 (2012): 562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tierney WM, Alpert SA, Byrket A, Caine K, Leventhal JC, Meslin EM, and Schwartz PH, “Provider Responses to Patients Controlling Access to their Electronic Health Records: A Prospective Cohort Study in Primary Care,” Journal of general Internatl Medicine vol. 30, no. 1 (2014): 31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.“SAS,” Statistical Analysis Toolkit, available athttp://www.sas.com/en_us/software/sas9.html (last visited May 24, 2017); see Schwartz et al. , supra note 24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.“CAT,” Coding Analysis Toolkit, available athttp://cat.texifter.com/ (last visited May 24, 2017).

- 31.“National Institute of Mental Health,” available http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-mentalillness-ami-among-adults.shtml (last visited May 24, 2017); see Wright, supra note 26.

- 32.See NCVHS for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, supra note 2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.See Dhopeshwarkar, supra note 5.

- 34.See Schwartz, supra note 22.