Abstract

Background

Infantile colic is a common disorder in the first months of life, affecting somewhere between 4% and 28% of infants worldwide, depending on geography and definitions used. Although it is self limiting and resolves by four months of age, colic is perceived by parents as a problem that requires action. Pain‐relieving agents, such as drugs, sugars and herbal remedies, have been suggested as interventions to reduce crying episodes and severity of symptoms.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of pain‐relieving agents for reducing colic in infants younger than four months of age.

Search methods

We searched the following databases in March 2015 and again in May 2016: CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO, along with 11 other databases. We also searched two trial registers, four thesis repositories and the reference lists of relevant studies to identify unpublished and ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs evaluating the effects of pain‐relieving agents given to infants with colic.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures of The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

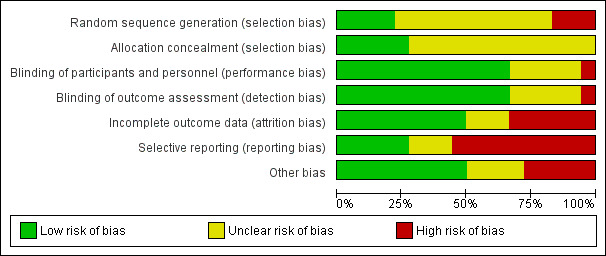

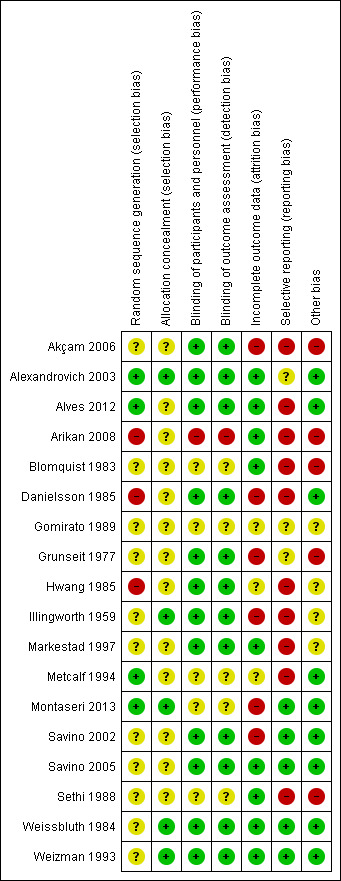

We included 18 RCTs involving 1014 infants. All studies were small and at high risk of bias, often presenting major shortcomings across multiple design factors (e.g. selection, performance, attrition, lack of washout period).

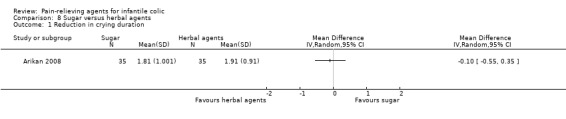

Three studies compared simethicone with placebo, and one with Mentha piperita; four studies compared herbal agents with placebo; two compared sucrose or glucose with placebo; five compared dicyclomine with placebo; and two compared cimetropium ‐ one against placebo and the other at two different dosages. One multiple‐arm study compared sucrose and herbal tea versus no treatment.

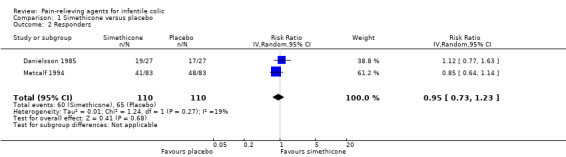

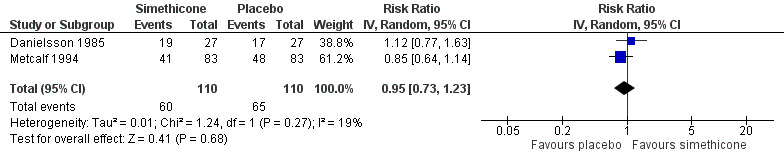

Simethicone. Comparison with placebo revealed no difference in daily hours of crying reported for simethicone at the end of treatment in one small, low‐quality study involving 27 infants. A meta‐analysis of data from two cross‐over studies comparing simethicone with placebo showed no difference in the number of of infants who responded positively to treatment (risk ratio (RR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.73 to 1.23; 110 infants, low‐quality evidence).

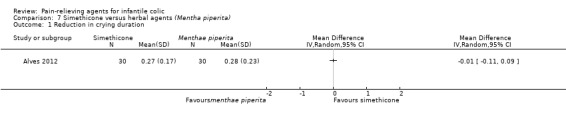

One small study (30 participants) compared simethicone with Mentha piperita and found no difference in crying duration, number of crying episodes or number of responders.

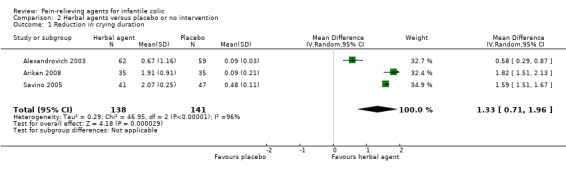

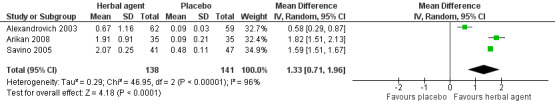

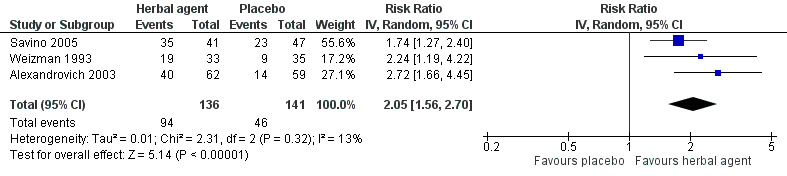

Herbal agents. We found low‐quality evidence suggesting that herbal agents reduce the duration of crying compared with placebo (mean difference (MD) 1.33, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.96; three studies, 279 infants), with different magnitude of benefit noted across studies (I² = 96%). We found moderate‐quality evidence indicating that herbal agents increase response over placebo (RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.56 to 2.70; three studies, 277 infants).

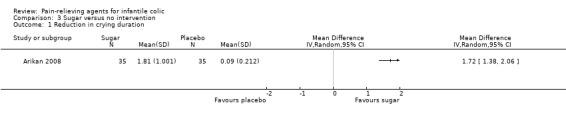

Sucrose. One very low‐quality study involving 35 infants reported that sucrose reduced hours spent crying compared with placebo (MD 1.72, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.06).

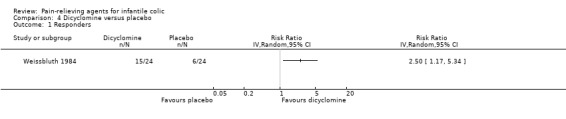

Dicyclomine. We could consider only one of the five studies of dicyclomine (48 infants) for the primary comparison. In this study, more of the infants given dicyclomine responded than than those given placebo (RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.17 to 5.34).

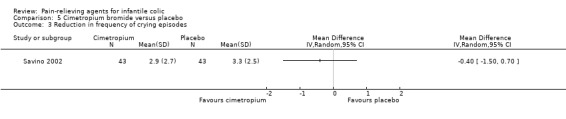

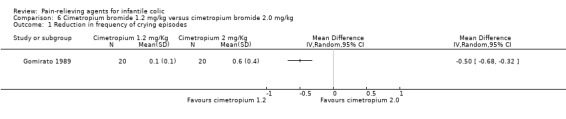

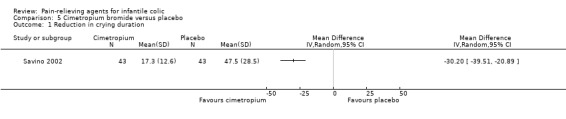

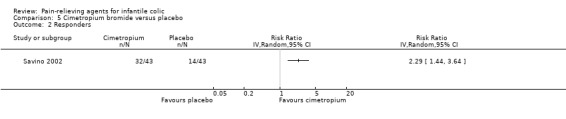

Cimetropium bromide. Data from one very low‐quality study comparing cimetropium bromide with placebo showed reduced crying duration among infants treated with cimetropium bromide (MD ‐30.20 minutes per crisis, 95% CI ‐39.51 to ‐20.89; 86 infants). The same study reported that cimetropium increased the number of responders (RR 2.29, 95% CI 1.44 to 3.64).

No serious adverse events were reported for all of the agents considered, with the exception of dicyclomine, for which two of five studies reported relevant adverse effects (longer sleep 4%, wide‐eyed state 4%, drowsiness 13%).

Authors' conclusions

At the present time, evidence of the effectiveness of pain‐relieving agents for the treatment of infantile colic is sparse and prone to bias. The few available studies included small sample sizes, and most had serious limitations. Benefits, when reported, were inconsistent.

We found no evidence to support the use of simethicone as a pain‐relieving agent for infantile colic.

Available evidence shows that herbal agents, sugar, dicyclomine and cimetropium bromide cannot be recommended for infants with colic.

Investigators must conduct RCTs using standardised measures that allow comparisons among pain‐relieving agents and pooling of results across studies. Parents, who most often provide the intervention and assess the outcome, should always be blinded.

Plain language summary

Pain‐relieving agents for infantile colic

Review question

Do infants who have colic during the first four months of life benefit from pain‐relieving agents (substances to alleviate/prevent pain) when compared with infants who are given no substance or a placebo (a substance that is identical to the drug but has no active ingredient)?

Background

Infantile colic, which is a common problem in infancy, occurs in the first four months of life in otherwise healthy infants. It is characterised by episodes of excessive crying and often leads to anxiety in parents and in doctors who work with infants.

Pain‐relieving agents, such as drugs (e.g. simethicone, dicyclomine, cimetropium), herbal remedies (e.g. Matricaria recutita, Foeniculum vulgare, Melissa officinalis) and sugar, have been proposed to reduce the symptoms associated with infantile colic, particularly the amount of time spent crying.

Study characteristics

We found 18 randomised controlled trials (studies in which participants were randomly assigned to one of two or more treatment groups) involving 1014 infants with infantile colic. The evidence is current to May 2016.

Infants were eight to 16 weeks old, and males and females were equally represented. All infants had colic, defined in one of two ways. Some studies defined it as inconsolable crying in otherwise healthy infants, lasting longer than three hours per day for more than three days a week for longer than three weeks. Other studies defined colic as attacks of screaming and crying (usually in the afternoon, or in the early evening) during which the infant failed to respond to any amount of comforting by adults.

Four studies explored the effects of simethicone (a drug used to reduce excess gas in the intestinal tract); four studies looked at herbal agents (plant‐derived remedies that might have relaxing properties that reduce cramps and pains in the bowel); two studies looked at sugar; and five studies explored the effects of dicyclomine and two the effects of cimetropium bromide (drugs that relieve bowel muscle spasms). One study compared sucrose and herbal tea in a group of infants who received no treatment for colic.

Sixteen of 18 studies compared the intervention with a placebo. Among the other two studies, one compared simethicone with Mentha piperita, and the other compared two different dosages of cimetropium.

Included studies received funding from different sources: a public institution (two studies), academic funds (one study) and private companies (three studies). Three studies received no funding. Nine studies did not report whether the study received funding. In four studies that reported no funds and no details about funds, private companies supplied the products (pain‐relieving agents).

Key results

Available data provide no evidence that sugar, dicyclomine and cimetropium are effective interventions in the treatment of colic. Some evidence suggests that, compared with placebo or no treatment, herbal agents may reduce crying time. However, because the quality of these studies was very poor and the extent of the benefit observed was variable, these results should be interpreted with caution. The same is true for sugar, dicyclomine and cimetropium, for which we judged the quality of evidence as low or very low.

Studies that tested simethicone reported no benefit from administration of this drug over placebo.

Two studies reported side effects for dicyclomine, for example, difficulty awakening, wide‐eyed state and drowsiness. Studies of other pain‐relieving agents reported no side effects as a result of treatment.

Quality of the evidence

Low‐quality evidence indicates that infants with colic may benefit from treatment with sugar and cimetropium, and that herbal agents may reduce crying time. Moderate‐quality evidence suggests that these agents increase the number of children experiencing improvement in symptoms. Overall, evidence is insufficient to allow firm conclusions about the benefits and side effects of the pain‐relieving agents examined for treatment of crying due to infantile colic.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Simethicone versus placebo for infantile colic.

| Simethicone versus placebo for infantile colic | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants with infantile colic Settings: university primary care centre (Sweden) and general paediatric practices (USA) Intervention: simethicone versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Simethicone vs placebo | |||||

| Reduction in crying duration Difference between final values (hours per day of crying) Follow‐up: mean 7 days | Mean crying duration in control groups was 4.37 hours/d | Mean crying duration in intervention groups was 0.13 lower (1.4 lower to 1.14 higher) | MD ‐0.13 (‐1.40 to 1.14) | 27 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ‐ |

| Responders Number of infants who improved after treatment Follow‐up: mean 7 days | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.73 to 1.23) | 110 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | ‐ | |

| 591 per 1000 | 561 per 1000 (431 to 727) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 604 per 1000 | 574 per 1000 (441 to 743) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aHigh risk of selection, attrition and reporting bias. bOnly one study with 27 infants. cOnly two studies with 110 infants.

Summary of findings 2. Herbal agents versus placebo for infantile colic.

| Herbal agents versus placebo for infantile colic | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with infantile colic Settings: multi‐speciality clinics (Russia); university hospitals (Turkey, Italy); primary community‐based clinics (Israel) Intervention: herbal agents versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Herbal agents vs placebo | |||||

| Reduction in crying duration Difference before and after treatment (hours per day of crying) Follow‐up: mean 7 days | Mean reduction in crying duration in control groups was 0.22 hours/d. | Mean reduction in crying duration in intervention groups was 1.33 higher (0.71 to 1.96 higher). | MD 1.33 (0.71 to 1.96) | 279 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ‐ |

| Responders Number of infants who improved after treatment Follow‐up: mean 7 days | Study population | RR 2.05 (1.56 to 2.7) | 277 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | ‐ | |

| 326 per 1000 | 669 per 1000 (509 to 881) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 257 per 1000 | 527 per 1000 (401 to 694) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aOne study with high risk of selection, performance, detection, reporting and other bias. bVery high heterogeneity (96%). cTwo studies with unclear risk of selection bias.

Summary of findings 3. Sugar versus placebo for infantile colic.

| Sugar versus placebo for infantile colic | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants with infantile colic Settings: university hospital (Turkey) Intervention: sugar versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Sugar vs placebo | |||||

| Reduction in crying duration Difference before and after treatment (hours per day of crying) Follow‐up: mean 7 days | Mean reduction in crying duration in control groups was 0.09 hours/d of crying. | Mean reduction in crying duration in intervention groups was 1.72 higher (1.38 to 2.06 higher). | MD 1.72 (1.38 to 2.06) | 70 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; MD: mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aHigh risk of selection, performance, detection, reporting and other bias. bOnly one study with 70 infants.

Summary of findings 4. Cimetropium bromide versus placebo for infantile colic.

| Cimetropium bromide versus placebo for infantile colic | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants with infantile colic Settings: university hospital (Italy) Intervention: cimetropium bromide versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Cimetropium bromide vsplacebo | |||||

| Reduction in crying duration Difference between final values (minutes per crisis of crying) Follow‐up: mean 3 days | Mean reduction in crying duration in control groups was 47.5 minutes per crisis of crying | Mean reduction in crying duration in intervention groups was 30.2 lower (39.51 to 20.89 lower) | MD ‐30.20 (‐39.51 to ‐20.89) | 86 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ‐ |

| Responders Number of infants who improved after treatment Follow‐up: mean 3 days | Study population | RR 2.29 (1.44 to 3.64) | 86 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ‐ | |

| 326 per 1000 | 746 per 1000 (469 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 326 per 1000 | 747 per 1000 (469 to 1000) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aOnly one study with 86 infants. bHigh risk of attrition bias.

Background

Infants cry for various reasons to express discomfort caused by conditions ranging from benign disorders to life‐threatening illness. Heine 2006 suggested that less than 5% of distressed infants have identifiable medical explanations for their crying. Infantile colic, which is defined as excessive crying in the first few months of life, is a common but poorly understood and often frustrating problem for parents and carers, and is frequently a reason for consultation with paediatricians and community nurses (Freedman 2009).

Description of the condition

Infantile colic represents a clinical condition with a reported incidence from 4% to 28%; this wide range of occurrence seems not to be associated with factors such as nationality and clinical criteria (i.e. gender, socioeconomic class, type of feeding, family history of atopy, and parental smoking) (Lucassen 2001; Lucassen 2015; Vandenplas 2015). Infantile colic is characterised by inconsolable crying, fussing and irritability in an otherwise healthy newborn during the first three months of life. Infant crying tends to occur in the evening and usually increases at six weeks of age, with drawing up of the legs, tension of the body, flushing of the face, painful bowel movements and meteorism (abdominal bloating). The diagnosis is clinical, and the most often cited definition is based on the rule of three, that is, unexplained episodes of paroxysmal crying for longer than three hours per day for three days per week for at least three weeks (Wessel 1954). Many other definitions are available, reflecting different conditions with other risk factors (Reijneveld 2002). Infantile colic shows a wide range of clinical manifestations and can be graded as mild, moderate or severe, but no consensus is known for this classification. The natural history of infantile colic is favourable, and symptoms gradually disappear by around three months of age.

It has been suggested that both biological components (food hypersensitivity/allergy and gut dysmotility) and behavioural factors (psychological and social) may play a role in the development of colic (Gupta 2007). It seems that some infants are predisposed to visceral hypersensitivity and hyperalgesia in the first weeks of life.

Available evidence suggests that infantile colic might have several independent causes, including those listed below (Savino 2007).

Carbohydrate malabsorption, in particular, lactose intolerance due to a relative lactase deficiency (Kanabar 2001).

Food hypersensitivity (cow's milk allergy; Hill 2000; Iacono 2005). Colic might represent an early manifestation of food allergy, although results of studies investigating a link between infant colic and atopy have been conflicting (Gupta 2007; Heine 2006; Iacono 1991). Some infants with moderate or severe symptoms have cow’s milk‐dependent colic that improves after a few days of a hypoallergenic diet. Therefore, in bottle fed babies, a two‐to‐four‐week trial of extensively hydrolysed formulae has been recommended (Fiocchi 2010; Nocerino 2015).

Feeding disorder, that is, disorganised feeding behaviour and lower responsiveness during feeding interaction with mother (Miller‐Loncar 2004).

Dysmotility. Some researchers have suggested that transient dysregulation of the nervous system during development may cause intestinal hypermotility in infants with colic; the predominance of the parasympathetic and the sympathetic nervous system has also been investigated (Garrison 2000; Lucassen 1998; Savino 2002; Weissbluth 1984).

Gut microflora. Lehtonen 1994 first hypothesised that infantile colic may arise from an aberrant gut microbial composition in the first months of life that affects the intestinal fatty acid profile. The role of peculiar intestinal lactobacilli and a particular coliform colonisation pattern has been proposed in the etiopathogenesis of the condition (Savino 2004; Savino 2005b; Savino 2009). More recently, Rhoads demonstrated that gut inflammation and an altered, less diverse fecal flora are seen in infants with colic (Rhoads 2009).

Psychological factors, such as personality disturbance in the child or less than optimal parent–infant interactions (Akman 2006; Canivet 2000; Räihä 2002; Van den Berg 2009; Vik 2009).

Possibly higher rate of night wakening and less nocturnal sleep (Lehtonen 1994b). Data suggest that colic may be associated with disruption and delay in maturation of the circadian rhythm and sleep‐wake organisation, both of which resolve when colic disappears; however, the topic of effects of colic on sleep remains controversial (Sadeh 2009).

Recent hypotheses. Effects of hormone alterations (Savino 2006) and maternal smoking (Canivet 2008) remain to be confirmed.

Infantile colic is a clinical entity with a wide range of presentations and outcomes. Paediatricians should first exclude other underlying diseases through medical examination and should prevent feeding disorders. Then, in light of the favourable clinical course of the condition, healthcare providers should assist parents in adopting safe and well‐tolerated strategies (Savino 2010).

Description of the intervention

Treatment approaches can be grouped into the following categories: pharmacological treatments (e.g. dicyclomine hydrochloride, cimetropium bromide, simethicone), probiotics, complementary therapies (including herbal agents and sucrose), manipulative therapies (including acupuncture), dietary interventions and parental behavioural interventions (Savino 2014). A Cochrane review has examined the effectiveness of manipulative therapies (Dobson 2012); two other Cochrane reviews are ongoing ‐ one on the effectiveness of probiotics (Praveen 2014) and another on dietary modification (Savino 2014b).

This review examines the effectiveness and safety of the following pain‐relieving agents: pharmacological interventions (dicyclomine hydrochloride, cimetropium bromide and simethicone) and complementary therapies (herbal formulations, sucrose or glucose). The development of visceral pain in infancy is a highly complex process with important implications for analgesic policy and clinical management. These agents are aimed at reducing gastrointestinal discomfort, which has been theoretically linked with infantile colic.

Dicyclomine hydrochloride is an anticholinergic drug with antispasmodic activity that is used to relax muscles in the wall of the gut and prevent spasms. Despite some findings of effectiveness in infantile colic, adverse effects have been reported in about 5% of treated infants. Drowsiness, diarrhoea and constipation are most commonly reported, but severe adverse effects, such as apnoea, breathing difficulties, seizures and coma, have also occurred (Edwards 1984; Garriott 1984; Randall 1986; Williams 1984). For this reason, use of anticholinergic drugs is now contraindicated in infants before six months of age (Garrison 2000). Nevertheless, we decided to include dicyclomine in our review for completeness, that is, to perform a comprehensive systematic review that includes all of the agents that have been used or are actually used to treat infant colic, even if one or some of them are not yet recommended because of their ineffectiveness or adverse events.

Cimetropium bromide is an antimuscarinic compound derivative of belladonna with considerable penetration in the blood‐brain barrier. It shows competitive, surmountable antagonism of muscarine receptors of visceral smooth muscle and direct myolytic activity (Bassotti 1987; Imbimbo 1986; Sagrada 1989; Scarpignato 1985; Schiavone 1985). Cimetropium bromide has been well tolerated in infants when administered at the tested dosage. The only registered side effect is increased sleepiness that might be related to pain resolution rather than to central nervous system effects (Savino 2002).

In addition to conventional therapies, the anticholinergic and antiadrenergic activities of some herbal formulations, such as fennel, lemon balm and chamomile, have been proposed to relieve pain (Savino 2005; Weizman 1993).

Simethicone silicone latex, a defoaming agent, is a pharmacological agent that could act as a detergent to reduce the surface tension of bubbles in the intestinal tract, in theory enabling abdominal gas to be expelled more easily. It is safe and may reduce meteorism (abdominal bloating; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

How the intervention might work

Potential remedies for the management of infantile colic have shown different mechanisms of action; however, the ultimate goal is to relieve pain.

Many years ago, researchers stated that most cases of infantile colic could be explained by colonic hyperperistalsis and increased rectal pressure. In particular, the early literature refers to colic as "hypertonia of infancy". Predominance of the parasympathetic as well as the sympathetic nervous system has been investigated. Indeed, the gastrointestinal tract contains a wide variety of hormones involved in the regulation of intestinal motility (i.e. vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), gastrin, motilin (Lothe 1987), and ghrelin). Lothe 1990 hypothesised that motilin, whose serum levels were increased in infants who developed colic, might play a central role in the etiopathogenesis of the condition through its activity in enhancing gastric emptying through increased small‐bowel peristalsis and decreased transit time. In another study, colicky infants presented higher serum levels of motilin and ghrelin compared with their healthy counterparts, suggesting that ghrelin may be implicated in promoting abnormal hyperperistalsis (Savino 2006). These concepts supported the hypothesis of beneficial effects derived from drugs with antispasmodic effects, such as dicyclomine hydrochloride, cimetropium bromide and some herbal formulations. Dicyclomine, which relaxes muscles in the wall of the gut and prevents spasms, has been used in the treatment of infantile colic on the assumption that spasms of intestinal smooth muscle cause colic symptoms (Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Weissbluth 1984). Cimetropium bromide may reduce intestinal sensitivity and hypermotility through its competitive antagonism of muscarine receptors of the visceral smooth muscles and by its spasmolytic activity (Bassotti 1987; Imbimbo 1986; Sagrada 1989; Scarpignato 1985; Schiavone 1985). Fennel, lemon balm and chamomile may be effective in the treatment of infantile colic because of their anticholinergic and antiadrenergic activities. In particular, in animal models, upper gastrointestinal transit has been influenced by the oral administration of an herbal formulation containing extracts from Matricaria recutita flowers (chamomile), Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) and the aerial parts of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) (Capasso 2007).

Excessive intraintestinal air load, aerophagia and pain, which are characteristic symptoms of colic crying, may be related to increased production of gas in the lower bowel (Sferra 1996). Treem 1994 suggested that colicky infants produce large amounts of gas, probably as the result of colonic bacterial fermentation of malabsorbed dietary carbohydrate, and that they are relieved of symptoms by the passage of gas. Simethicone decreases abdominal distension and discomfort due to excessive gas production through dispersion of gas bubbles from the gastrointestinal tract. For this reason, it has been studied as treatment for colicky infants, with researchers postulating that physical signs during colic episodes, such as bearing down and passage of flatulence, suggest excessive gas (Danielsson 1985; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

Finally, oral sugar solution has proved to have analgesic and calming effects on newborns (Carbajal 1999; Skogsdal 1997).

Why it is important to do this review

Infantile colic is a frequent but poorly understood and often distressing problem for parents and carers. The favourable clinical course, the range of ways in which it manifests and the day‐to‐day variability in crying time suggest that a well‐tolerated, multi‐factorial and graded strategy should be adopted.

Two systematic reviews have focused on therapeutic interventions for colic (Garrison 2000; Lucassen 2001), but these are now well out‐of‐date. A more recent review, published in 2011, did not include herbal formulations (Hall 2012). A recent Cochrane review examined the effectiveness of manipulative therapies (Dobson 2012); two other Cochrane reviews are ongoing ‐ one on the effectiveness of probiotics (Praveen 2014), and another on dietary modifications (Savino 2014; Savino 2014b). Ultimately, up‐to‐date systematic reviews should seek to inform clinical guidelines for the treatment of infants with colic.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of pain‐relieving agents for reducing colic in infants younger than four months of age.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs.

Types of participants

Infants younger than four months of age at enrolment who had infantile colic, as confirmed by a physician. Infantile colic is defined as a prolonged period of crying for no apparent reason in an otherwise healthy infant. For inclusion in this review, we accepted all definitions of excessive crying, and both breast fed and bottle fed infants were eligible.

We excluded studies of infants with crying of normal duration.

Types of interventions

We included any pain‐relieving agent used for the treatment of infant colic, that is, pharmacological interventions (dicyclomine, cimetropium bromide, simethicone) and complementary interventions (herbal formulations, sucrose or glucose). These agents could be compared with placebo or with no treatment. We also included studies that compared two different agents against each other and we performed separate analyses.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Reduction in crying duration (post‐treatment vs baseline)* (available data may be continuous, for example, hours per day, or dichotomous, for example, reduction under a threshold defined by trialists)

Responders* (dichotomous outcome), defined as proportions of participants who showed improvement by the end of treatment, according to the measures used by study authors

Secondary outcomes

Reduction in frequency of crying episodes (post‐treatment vs baseline)* (available data may be continuous, for example, hours per day, or dichotomous, for example, reduction under a threshold defined by trialists)

Parental or family quality of life, including measures of parental stress, anxiety or depression (continuous outcome)

Sleeping time, that is, change in duration of peaceful sleeping (post‐treatment vs baseline)* (continuous outcome)

Parental satisfaction, measured by Likert scales or on a numerical rating scale (NRS) (continuous outcome)

Adverse effects: constipation, vomiting, apnoea, apparent life‐threatening events (ALTEs) and lethargy* (dichotomous outcome)

Timing of outcome assessment: We included outcomes evaluated after completion of any treatment protocol (i.e. any period, any number of treatments) and at later follow‐up, if reported.

*We included those outcomes marked with an asterisk (*) in Table 1, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2008).

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the initial searches in April 2012 with no limitations by date, language or publication type. We updated the searches in April 2014, and added an age filter to the strategies for CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE and Embase to reduce the number of irrelevant records. We updated the searches most recently on 27 March 2015, and on 16 May 2016. We reported details about each set of searches in Appendix 1, and reported search strategies for each source in Appendix 2.

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases listed below.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library (searched 16 May 2016), which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group Specialised Register.

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to May week 1 2016).

MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations Ovid (13 May 2016).

Embase Ovid (1980 to 2016 week 20).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to May week 2 2016).

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to current).

Science Citation Index Web of Science (SCI; 1970 to 16 May 2016).

Social Science Citation Index Web of Science (SSCI; 1970 to 16 May 2016).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science Web of Science (CPCI‐S; 1970 to 16 May 2016).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Sciences & Humanities Web of Science (CPCI‐SS&H; 1970 to 16 May 2016).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2016, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (searched 16 May 2016).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2016, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library (searched 16 May 2016).

WorldCat (limited to theses and dissertations; www.worldcat.org; searched 17 May 2016).

HOMEOINDEX (Virtual Health Library; bvsalud.org/en; searched 17 May 2016).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database; Virtual Health Library; lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 16 May 2016).

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (SCIRUS) (NDLTD; all available years up to 2012. Not available via SCIRUS after 2012. Searched again via search.ndltd.org/index.php on 17 May 2016).

IBECS (Virtual Health Library; bvsalud.org/en; searched 17 May 2016).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 17 May 2016).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; who.int/ictrp/en; searched 17 May 2016).

TROVE (limited to Australian theses; trove.nla.gov.au; searched to 27 March 2015).

DART‐Europe E‐theses Portal (www.dart‐europe.eu/basic‐search.php; searched to 27 March 2015).

Searching other resources

We evaluated bibliographies of articles identified through the electronic searches to look for additional published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (FS, VT) independently screened titles and abstracts yielded by the searches, discarding irrelevant records. Review authors then retrieved the full text of all potentially eligible articles to assess them independently against the inclusion criteria. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and, when necessary, by consultation with a third review author (EB). If information was not forthcoming, or if we were unable to resolve the dispute, we approached the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group (CDPLPG) editorial base for advice.

Data extraction and management

We developed data extraction forms a priori, as per recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We extracted the information listed below.

Methods: study design, setting, duration, recruitment procedures, risk of bias (such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, evaluation of success of blinding).

Participants: source of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, total number at baseline, total number at completion, definition of 'colic' applied, diagnostic criteria applied, age at onset of colic, age at commencement of intervention, evaluation of potential effects of confounding characteristics (e.g. age, gender, breast fed or bottle fed).

Interventions and controls: number of groups, intervention(s) applied, frequency and duration of treatment, total number of treatments, permitted co‐interventions, evaluation of potential therapeutic value of sham/placebo.

Outcomes: list of outcomes assessed, definitions used, values for mean and standard deviation (SD) at baseline and at time points defined by the study protocol (or change from baseline measures, if given).

Results: measures at end of protocol, follow‐up data (including means, SDs, standard errors and confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous data and frequencies for dichotomous data), withdrawals, loss to follow‐up.

Other: references to other relevant studies, points to follow up on with study authors, comments from review authors, key conclusions of the study (of study authors), other comments from review authors.

Two review authors (FS, VT) extracted data independently using the data extraction form. The third review author (EB) resolved disagreements.

We used the latest version of Review Manager (RevMan) software (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FS, VT) independently evaluated each study for risk of bias using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b) for the domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential threats to validity. For each included study, review authors rated each domain as having low, high or unclear risk of bias, and then compared their grading. In the case of differently scored items, the two review authors tried to reach agreement by discussion. If this was not possible, we discussed disagreements with the rest of the team until consensus was reached. Review authors were not blinded to the titles of journals nor to the identities of study authors, as they are familiar with the field. We provide in Appendix 3 a detailed description of the criteria used to judge risk of bias for each domain.

In this context, parents often administered the intervention. Thus, we primarily assessed the risk of bias associated with blinding of participants and personnel on the likelihood that such blinding was sufficient to ensure that parents had no knowledge of which intervention the infant received. We considered blinding of participants to be unnecessary in this population of young infants.

We considered as outcome assessors both parents and those who interpreted the crying diaries (paediatrician, nurse).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we calculated effect sizes as risk ratios (RRs) with their associated 95% CIs and probability values (P values), when possible. When the RR did not straddle the position of null effect, we pooled dichotomous data and calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the associated 95% CI.

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we presented mean differences (MDs) in change scores or final values, according to available data, and 95% CIs. If studies used different scales to measure the same outcome, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to standardise the MD to a uniform scale.

Unit of analysis issues

For each included study, we determined whether the unit of analysis was appropriate for the unit of randomisation and the design of each study (in other words, whether the number of observations matched the number of randomised 'units') (Deeks 2008).

Studies with multiple treatment arms

When we found multi‐arm studies, we combined results across all eligible intervention (pain‐relieving agents) arms, making single, pair‐wise comparisons, but we divided the sample size for common comparator arms proportionately across each comparison (Higgins 2008c). This simple approach allowed the use of standard software (including RevMan 2014) and prevented inappropriate double‐counting of individuals. When such a strategy prevented investigation of potential sources of heterogeneity, we analysed each pain‐relieving agent separately.

Cross‐over studies

In randomised cross‐over studies, individuals receive each intervention sequentially in random order. One problem with this design involves the risk of carry‐over effect, which occurs when the first treatment affects the second. To reduce the carry‐over effect, cross‐over studies usually include a washout period, that is, a stage after the first treatment but before the second treatment during which time is given for the active effects of the first treatment to wear off before the new treatment is begun. Inadequate washouts are seen when the carry‐over effect exceeds the washout period. For this review, we considered a minimum of one day to be an adequate washout period for cross‐over studies.

We used the inverse variance method, as recommended by Elbourne 2002, to include data from cross‐over studies with an adequate washout period. To take account of the correlation between the two study periods, we calculated the correlation co‐efficient between periods for each study (Savino 2012). When the correlation co‐efficient could not be obtained, we used data from the first period only. For continuous data, no studies reported the SD of a paired t‐test, and for binary data, only one of the included studies with a planned washout period reported the number of participants who responded to both treatments (Metcalf 1994). Consequently, we decided to analyse cross‐over trials as if they were parallel‐group trials. This approach, even if it is not the most correct, is conservative, as it overestimates the variability between study periods. Furthermore, we conducted separate meta‐analyses for both cross‐over and parallel‐group trials, thus avoiding the unit of analysis error.

For cross‐over studies with an inadequate washout period, we used data from the first period only. If data from the first period were not available, we did not incorporate these studies into the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

For missing continuous data, we estimated SDs from other available data, such as standard errors, or we imputed them using the methods described in Higgins 2011c. We made no assumptions about loss to follow‐up, and we based our analyses on participants who completed the trial.

For missing dichotomous outcomes, we investigated the effects of dropout and exclusion by conducting analyses of worst‐case versus best‐case scenarios.

If we noted a discrepancy between the number randomised and the number analysed in each treatment group, we calculated and reported the percentage lost to follow‐up for each group.

For all included studies, we analysed available data. When we observed that data were missing, we recorded this on the data collection form and reported it in the 'Risk of bias' table (beneath the Characteristics of included studies tables), and in the Discussion section of the review, we considered the extent to which the missing data could alter our results and conclusions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing the distribution of important participant factors (e.g. age) across trials, interventions and outcomes. We assessed methodological heterogeneity by comparing the distribution of important trial factors (e.g. study design, risk of bias (such as randomisation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment), losses to follow‐up).

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by examining the I² statistic (Deeks 2008), a quantity that describes the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to variability across studies rather than to sampling error. We interpreted the I² statistic as recommended in the latest version of Higgins 2011c, as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: may represent considerable heterogeneity.

We also evaluated the CI for the I² statistic.

In addition, we employed a Chi² test of homogeneity to determine the strength of the evidence that heterogeneity was genuine, and used Tau² to assess between‐study variability.

Assessment of reporting biases

To minimise publication bias, we attempted to obtain the results of unpublished studies to compare results extracted from published journal reports with results from other sources (including correspondence).

Data synthesis

When interventions were similar in terms of type of pain‐relieving agent, type of outcome assessed and type of colic, we grouped these studies and synthesised their results in a meta‐analysis. We presented results for each combination of pain‐relieving agent and assessed outcome and colic type, except in studies for which no data were provided.

Because we assumed that clinical heterogeneity was very likely to impact the results of our review, given the wide breadth and types of interventions included, we combined studies by using a random‐effects model, regardless of statistical evidence of heterogeneity for effect sizes. We calculated all overall effects by using the inverse variance method. We converted continuous data to MD, and if different scales were used, we first computed SMD, then overall MD and overall SMD (Schünemann 2008). If both a continuous outcome and a dichotomous outcome were available for a particular outcome, we included only the continuous outcome in the primary analysis. If some studies reported an outcome as a dichotomous measure and others used a continuous measure for the same construct, we converted results of the former from an odds ratio (OR) to an SMD (Deeks 2011), provided that we could assume the underlying continuous measure had approximated a normal or logistical distribution (otherwise, we carried out two separate analyses).

We carried out statistical analyses by using RevMan 2014.

Summary of findings table

We summarised the evidence in 'Summary of findings' tables and provided summary estimates of absolute and relative effects (see Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; and Table 4). We included a rating (ranging from very low to high) of our confidence in the estimate of effect for the overall quality of evidence for each outcome, as assessed via the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2013). We used an iterative, electronic correspondence discussion process to reach consensus on factors that affect confidence in the estimate of effects (including risk of bias, i.e. design and study limitations; imprecision; indirectness (directness in the GRADE approach includes generalisability and applicability); inconsistency of results, i.e. heterogeneity; magnitude of effect; and issues of residual plausible confounding); and in evidence rating.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed no subgroup analyses because we included too few studies in each comparison, making subgroup analyses impossible or non‐informative.

Subgroup analyses archived for future updates of this review can be found in Appendix 4 and in our protocol (Savino 2012).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether findings were sensitive to restriction of analyses to studies judged to be at low risk of bias for blinded assessment of the primary outcome. When sensitivity analyses confirmed results of the main analysis, we regarded results of the review with a higher degree of certainty.

We did not conduct planned sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of missing data on results because the percentage of missing data was low in all included studies (ranging from 0% to 16.7%; see Table 5). These sensitivity analyses, which have been archived for future updates of this review, can be found in Appendix 4 and in our protocol (Savino 2012).

1. Summary of study characteristics.

| Study | N°infants enrolled | N° infants analysed | Mean age (SD) in weeks at study entry | Male (%) | Intervention/control | Loss to follow‐up (%) (intervention/control) | Study treatment duration (in days) | Study design | Outcomes |

| Akçam 2006 | 30 | 25 | 9.1 (5.9) | 40 | Glucose (30%)/placebo | 16.7 | 4 | Randomised, cross‐over | Responders Adverse effects |

| Alexandrovich 2003 | 125 | 121 | 4.3 (1.1) | 45.5 | Fennel seed oil emulsion/placebo | 4.6/1.7 | 7 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders (as relief of colic symptoms) Cumulative crying time (hours/week) Number of doses/d Consumed mL/d Adverse effects |

| Alves 2012 | 30 | 30 | 4.7 (1.6) | 45.5 | Simethicone/herbal agents (Mentha piperita) | 0 | 7 | Randomised, cross‐over | Responders (as improvement in symptoms) Frequency of colic episodes (daily) Daily colic duration (minutes) Duration of colic Adverse effects |

| Arikan 2008 | 175 | 105* | 8.24 (2.88) | 55.5 | Herbal tea or sucrose/no treatment | 0 | 7 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Crying time (hours/d) |

| Blomquist 1983 | 18 | 18 | Range 2 to 14 | 44.4 | Dicyclomine plus sugar/placebo | 0 | 7 | Randomised, cross‐over | Responders (as improvement in colic severity) Frequency of crying episodes |

| Danielsson 1985 | 27 | 27 | 4.8 (range 2 to 8) | 44.4 | Simethicone/placebo | 0 | 7 | Quasi‐randomised, cross‐over | Responders Crying time (hours/d) Time sleeping (hours/d) Number of feedings Number of stools |

| Gomirato 1989 | 40 | 40 | 4.4 | 40 | Cimetropium bromide (1.2 mg/kg)/cimetropium bromide (2.0 mg/kg) | 0 | 14 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders (as improvement in symptoms) Number of crying episodes/d Duration of longest episodes (minutes) Adverse effects |

| Grunseit 1977 | 25 | 22 | 5.4 (range 3 to 12) | 40.9 | Dicyclomine/placebo | 12.0 | 7 | Randomised, cross‐over | Score of symptoms (as continuous measure) |

| Hwang 1985 | 30 | 30 | 4 to 5 | Not reported | Dicyclomine/placebo | 0 | 7 | Quasi‐randomised, cross‐over | Responders (as improvement in symptoms) Crying time (hours/d) Sleeping time (hours/d) Adverse effects |

| Illingworth 1959 | 16 | 16 | < 8 | Not reported | Dicyclomine/placebo | 0 | 7 | Randomised, cross‐over | Score of symptoms Responders (as improvement in symptoms) |

| Markestad 1997 | 19 | 19 | 7.3 (3.4) | 68.4 | Sucrose (12%)/placebo | 0 | 8 to 12 | Randomised, cross‐over | Responders (as improvement in symptoms) Parental satisfaction |

| Metcalf 1994 | 83 | 83 | Not reported | 49.4 | Simethicone/placebo | 0 | 7 (3 to 10) | Randomised, cross‐over | Responders (as improvement in symptoms) |

| Montaseri 2013 | 60 | 50 | 8 (4 to 16) | 50 | Fumaria extract/placebo | 17.0 | 7 | Quasi‐randomised | Frequency of crying attack Crying duration Frequency of waking up (all as categorical variables) |

| Savino 2002 | 97 | 86 | Range 2 to 8 | Not reported | Cimetropium bromide/placebo | 9.8/13.0 | 3 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders Adverse effects |

| Savino 2005 | 93 | 88 | 4.3 (1.5) | 46.6 | Herbal tea/placebo | 4.7/6.0 | 7 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders Crying time (minutes/d) Adverse effects |

| Sethi 1988 | 26 | 26 | Range 1 to 12 | 40 | Simethicone/placebo | 0 | 7 | Randomised, cross‐over | Frequency of crying (daily) Amplitude of crying attack |

| Weissbluth 1984 | 48 | 48 | 5 | 58 | Dicyclomine/placebo | 0 | 14 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders Adverse effects |

| Weizman 1993 | 72 | 68 | 3.3 (1.2) | 38.6 | Herbal tea/placebo | 8.3/2.8 | 7 | Randomised, parallel‐arm | Responders (as colic eliminated) Frequency of nocturnal awakenings Colic improvement score |

*105 infants analysed for the three groups included in this review.

SD: standard deviation.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The electronic search identified 1306 records up to 16 March 2016.

After removing duplicates, we identified 1060 potentially relevant records. Two review authors (FS, VT) screened titles and abstracts for relevance and excluded 1032 records. We retrieved full‐text reports of the remaining 28 records and assessed these against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). We excluded nine studies (see Excluded studies) and identified one ongoing study (see Characteristics of ongoing studies), leaving 18 eligible studies that contributed to 19 comparisons (see Characteristics of included studies). A third independent review author (EB) screened reports of studies in which FS collaborated as a study author.

See Figure 1 for the study flow diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Eighteen studies involving 1014 infants met the inclusion criteria for this review (see Characteristics of included studies). The selected studies were conducted between 1959 (Illingworth 1959) and 2013 (Montaseri 2013).

Study design

All studies were RCTs. We found no quasi‐RCTs. Ten of 18 studies (56%) were cross‐over trials (Akçam 2006; Alves 2012; Blomquist 1983; Danielsson 1985; Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

Setting

Eleven studies were conducted in Europe (Akçam 2006; Arikan 2008; Blomquist 1983;Danielsson 1985; Gomirato 1989; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Savino 2002; Savino 2005; Sethi 1988), three in America (Alves 2012; Metcalf 1994; Weissbluth 1984), two in Asia (Montaseri 2013; Weizman 1993), one in Russia (Alexandrovich 2003) and one in Australia (Grunseit 1977).

Most of the studies were performed in children's hospitals (Alexandrovich 2003; Alves 2012; Arikan 2008; Gomirato 1989; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Savino 2002; Savino 2005, Weissbluth 1984), four in primary care clinics (Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Montaseri 2013; Weizman 1993) and the remaining five in general practitioner and paediatric outpatient clinics (Akçam 2006; Blomquist 1983; Danielsson 1985; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

Participants

The number of participants randomised to intervention and control groups ranged from 18 (Blomquist 1983) to 175 (Akçam 2006).

Participant age ranged from about one week (Sethi 1988) to 16 weeks (Montaseri 2013). Two studies did not provide the ages of enrolled infants (Metcalf 1994; Savino 2002).

Definition of colic

The definition of infant colic most commonly used within the broader literature is that given by Wessel 1954: "inconsolable crying for more than three hours per day for more than three days a week for more than three weeks". A total of 13 of the 18 included studies used this definition (Akçam 2006; Alexandrovich 2003; Alves 2012; Arikan 2008; Gomirato 1989; Hwang 1985; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Montaseri 2013; Savino 2002; Savino 2005; Weissbluth 1984; Weizman 1993), and some used minor modifications or more specific definitions (Akçam 2006; Alexandrovich 2003; Hwang 1985; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Montaseri 2013). Grunseit 1977 defined infant colic as "post‐prandial attacks of screaming and crying, unabated by maternal comforting, vomiting and sleep disturbance", and Illingworth 1959 reported that "the diagnosis was based on rhythmical attacks of screaming in the evenings in well, thriving babies who were gaining not less than seven oz per week during the period of observation, screaming unabated when the baby was picked up". The three remaining studies provided no definition of infant colic (Blomquist 1983; Danielsson 1985; Sethi 1988).

Pain‐relieving agents

Pain‐relieving agents varied across studies.

Simethicone was used in four studies (Alves 2012; Danielsson 1985; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

Herbal formulations were used in four studies (Alexandrovich 2003; Montaseri 2013; Savino 2005; Weizman 1993).

Sucrose or glucose was used in three studies (Akçam 2006; Arikan 2008; Markestad 1997).

Dicyclomine was used in five studies (Blomquist 1983; Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Weissbluth 1984).

Cimetropium bromide (a drug that is distributed only in Italy and in Corea) was used in two studies (Gomirato 1989; Savino 2002).

Herbal tea was used in one study (Arikan 2008).

Control conditions

In all but three studies, the control arm was given placebo. Gomirato 1989 evaluated two different dosages of cimetropium bromide (1.2 mg/kg vs 2.0 mg/kg); Arikan 2008 compared sucrose or herbal tea versus no treatment; and Alves 2012 compared simethicone medication against Mentha piperita.

Duration and frequency of treatments

Treatment schedules varied among studies.

Ten studies lasted for 14 days. Infants received the first treatment for seven days, then crossed to the other treatment group for the next seven days (Danielsson 1985; Gomirato 1989; Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988; Weissbluth 1984; Weizman 1993).

Two studies administered treatment for one week (Arikan 2008; Montaseri 2013).

One study lasted for eight days (Akçam 2006). Infants were administered treatment or placebo for four days, then were transferred over to the other study treatment arm for the next four days.

One study delivered treatment over a three‐week period: one week before enrolment to measure crying time followed by two weeks of treatment (Alexandrovich 2003).

Infants enrolled in one study received Mentha piperita for one week, then after three days of washout received simethicone for the next seven days (Alves 2012).

One study had a 15‐day duration consisting of one week of treatment and one day of washout, then cross‐over, followed by seven days of placebo (Blomquist 1983).

One study provided three days of treatment (Savino 2002).

One study lasted for 10 days: After three days of observation, infants were treated with an herbal agent or with placebo for a period of one week (Savino 2005).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

All studies provided data on at least one primary outcome (e.g. reduction in crying duration, responders).

Table 6 shows details on different definitions of responders as given by different study authors.

2. Responders' definitions.

| Author | Responders' definitions (as reported in the article) | Notes on definitions (as considered in the review) |

| Akçam 2006 | At each visit, parents described the effect of the last treatment on a scale of 6: 0 = 'getting worse', 1 = 'no improvement', 2 = 'mild improvement', 3 = 'moderate improvement' and 4 = 'completely well after each dose'. Responders were infants with improvement classified as 2, 3 or 4. | ‐ |

| Alexandrovich 2003 | Relief of colic symptoms, which were defined as decrease in cumulative crying to < 9 hours/week | ‐ |

| Alves 2012 | Responses were classified as slightly improved, greatly improved and completely improved. | From the results, all included patients seemed to show improvement. We considered as responders infants who had "completely improved" ‐ these infants had colic cessation. |

| Arikan 2008 | N/A | |

| Blomquist 1983 | Parents' ratings of the effects of infantile colic: excellent, good, moderate, worsening | Data from diagram 2: We considered as responders infants with excellent or good effects |

| Danielsson 1985 | Number of infants with improvement in symptoms (defined as better or much better) | ‐ |

| Gomirato 1989 | In the Methods section, improvement or worsening of symptoms was classified as follows: ‐ 2 crisis longer than baseline (> 60 minutes); ‐ 1 crisis longer than baseline (within 30 to 60 minutes); 0 = no improvement; + 1 crisis shorter than baseline (within 30 to 60 minutes); + 2 crisis shorter than baseline (> 60 minutes). In the Results section, only percentages of infants with excellent, good, moderate or poor improvement were reported. | We considered as responders infants with excellent or good improvement. |

| Grunseit 1977 | Pooled scoring symptoms (including postprandial crying, postprandial vomiting, sleeping disturbance); for each symptom, 0 = no symptom, 1 = mild, 2 = moderately severe, 3 = severe | ‐ |

| Hwang 1985 | Number of infants who improved receiving treatment or placebo | ‐ |

| Illingworth 1959 | Results were graded from ‐ 3 to + 3: + 1 the child was slightly better, + 2 definitively better but still had some discomfort, + 3 the infant was very greatly improved and free from symptoms. ‐ 1 the infant was slightly worse. | In the Results section, infants with + 3 seemed to be considered as responders. |

| Markestad 1997 | Methods section: Parents described effects of the last treatment on a scale from 5 ‘getting worse’ through ‘no improvement’, ‘some improvement’, ‘marked improvement’ and ‘complete stop of crying after each dose’. Results section: No details on obtained effect were provided ‐ only the number of infants who responded to sucrose or to placebo. | ‐ |

| Metcalf 1994 | A 5‐point scale was used to identify the child’s symptoms as definitely better or symptom‐free (+ 2), possibly better (+ 1), the same (0), possibly worse (‐ 1) or definitely worse (‐ 2). Responders to simethicone or to placebo were infants judged by the carer to have had a positive response (+ 1, + 2) only to simethicone or only to placebo. | ‐ |

| Montaseri 2013 | N/A | ‐ |

| Savino 2002 | Therapy was considered efficacious if crying ended within 15 minutes after administration of compounds. Responders were children who stopped crying within this time. The cutoff of 15 minutes was derived from the minimal crying time of each crisis before treatment. | ‐ |

| Savino 2005 | Therapy was considered efficacious if crying time was reduced by ≥ 50% per day; responders were infants who had such a reduction in crying time. | ‐ |

| Sethi 1988 | N/A | ‐ |

| Weissbluth 1984 | Number of participants without colic. Colic was defined on the basis of the Wessel definition (crying < 3 hours/d or crying > 3 hours/d for < 3 days/week). | ‐ |

| Weizman 1993 | Number of participants without colic. Colic was defined on the basis of the Wessel definition (crying < 3 hours/d or crying > 3 hours/d for < 3 days/week). | ‐ |

N/A: not applicable, because this outcome was not assessed in the study.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight full‐text articles: three because they were not experimental studies (Barr 1999; Benjamins 2013; Koonce 2011); two because the comparison was not eligible (Oggero 1994; Savino 2007); two because they were not comparative clinical studies (Becker 1988; NCT00655083); and one because the participants were not eligible (NCT01532518).

Ongoing studies

One trial was ongoing and compared two different dosages of nepadutant versus placebo (NCT01258153).

Risk of bias in included studies

We have provided details of 'Risk of bias' assessments in Characteristics of included studies tables, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We deemed the method of random sequence generation to be adequate in four studies (Alexandrovich 2003; Alves 2012; Metcalf 1994; Montaseri 2013); we rated these studies as having low risk of bias for this domain.

Eleven studies did not report information on sequence generation; we rated these as having unclear risk of bias (Akçam 2006; Blomquist 1983; Gomirato 1989; Grunseit 1977; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Savino 2002; Savino 2005; Sethi 1988; Weissbluth 1984; Weizman 1993).

We judged three studies as having high risk of selection bias because random sequence generation was not adequate (Arikan 2008; Danielsson 1985; Hwang 1985).

Regarding allocation concealment, five studies used an independent person to allocate participants to groups; we judged these as having low risk of bias for this domain (Alexandrovich 2003; Illingworth 1959; Montaseri 2013; Weissbluth 1984; Weizman 1993). All other studies provided no information on the method used to conceal allocation to study arms; we rated these as having unclear risk of bias (Akçam 2006; Alves 2012; Arikan 2008; Blomquist 1983; Danielsson 1985; Gomirato 1989; Grunseit 1977; Hwang 1985; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Savino 2002; Savino 2005; Sethi 1988).

Blinding

We considered blinding of parents as blinding of personnel because parents administered the treatment to their infants, completed the crying diaries and described the condition of the infant. We considered parents who completed the crying diaries, as well as those responsible for interpreting the crying diaries (in these situations, usually nurse or paediatrician), as outcome assessors.

Five studies provided no information on blinding of parents; we rated these studies as having unclear risk of performance and detection bias (Blomquist 1983; Gomirato 1989; Metcalf 1994; Montaseri 2013; Sethi 1988).

One study did not blind parents owing to the nature of the treatments compared (one of four treatment groups received massage) (Arikan 2008). We considered this study to be at high risk of performance and detection bias.

All other studies blinded parents to the treatment administered to their infant; we considered these studies to have low risk for performance and detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged six studies as having high risk of attrition bias (Akçam 2006; Danielsson 1985; Grunseit 1977; Illingworth 1959; Montaseri 2013; Savino 2002).

The articles for three studies provided insufficient details on the numbers of participants randomised and analysed; we judged these studies to have unclear risk of attrition bias (Gomirato 1989; Hwang 1985; Metcalf 1994).

We judged all other studies as having low risk of attrition bias because study authors reported no withdrawals, or because dropouts were few, dropouts were balanced between groups and reasons for dropout were reported.

Selective reporting

Three studies did not clearly specify the outcomes in the Methods section (Alexandrovich 2003; Gomirato 1989; Grunseit 1977); we judged these studies as having unclear risk of reporting bias. We judged 10 studies to have high risk of bias because study authors did not report the results for all outcomes mentioned in the Methods (Arikan 2008), or, for cross‐over studies, they did not report results separately for the first study period and the end of the study (Akçam 2006; Alves 2012; Blomquist 1983; Danielsson 1985; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

We considered all other studies to have low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged four cross‐over studies as having high risk of other bias because investigators planned no washout period (Akçam 2006; Blomquist 1983; Grunseit 1977; Sethi 1988); and one study with a parallel‐group design as having high risk of bias because of imbalance in relevant characteristics at baseline (Arikan 2008).

We judged three cross‐over studies as having unclear risk of other bias because study authors provided no information about the washout period (Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997); one parallel‐group study as having unclear risk of other bias because baseline differences between participants could not be excluded, as no such details were reported (Gomirato 1989); and all other studies as having low risk of bias in this domain.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Below, we present results grouped by pain‐relieving agent and outcome. We excluded from the meta‐analyses six cross‐over studies that provided no information about the washout period and did not report first period data (Akçam 2006; Blomquist 1983; Hwang 1985; Illingworth 1959; Markestad 1997; Sethi 1988). We provide a narrative description of these studies.

Comparison 1. Simethicone versus placebo

Three cross‐over studies with 136 infants were available for this comparison (Danielsson 1985; Metcalf 1994; Sethi 1988).

Primary outcomes

Reduction in crying duration

One study with 27 infants assessed the efficacy of simethicone for crying duration (Danielsson 1985) and reported final crying values only (i.e. without change scores).

Simethicone did not differ significantly from placebo as regards daily crying duration (daily hours of difference: MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐1.40 to 1.14; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Simethicone versus placebo, Outcome 1 Reduction in crying duration.

Responders

Two cross‐over studies involving 110 infants analysed the number of infants who responded positively to treatment (Danielsson 1985; Metcalf 1994). Infants treated with simethicone did not have a significantly higher probability of responding to this agent than those treated with placebo (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.23; tau² = 0.01, I² = 19%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 4).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Simethicone versus placebo, Outcome 2 Responders.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Simethicone versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Responders.

Secondary outcomes

Reduction in frequency of crying episodes

Sethi 1988 performed a cross‐over study without a washout period. Study authors reported a significant difference between active treatment and placebo in favour of simethicone after four days of treatment (P < 0.05). As stated above, study authors did not report results by treatment period and arm, but stated that the order of administration did not affect the results of treatment or placebo.

Parental or family quality of life, Sleeping time, parental satisfaction,

No studies assessed these outcomes.

Adverse effects

One study (Sethi 1988) involving 26 infants reported no adverse effects. The other two studies provided no data on adverse effects.

Comparison 2. Herbal agents versus placebo or no intervention

We included in this comparison five parallel‐group studies with 397 infants (Alexandrovich 2003; Arikan 2008; Montaseri 2013; Savino 2005; Weizman 1993).

Primary outcomes

Reduction in crying duration

Alexandrovich 2003, Arikan 2008 and Savino 2005 assessed crying duration. Montaseri 2013 also reported data for crying duration but reported the frequency of infants crying for less than one hour, between one and three hours and longer than three hours. Consequently, we were not able to include these data in the meta‐analysis.

For Analysis 2.1, we derived the correlation co‐efficient from Arikan 2008 and used it to calculate the SD of the mean reduction for Alexandrovich 2003 and Savino 2005, as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c). From this analysis (Analysis 2.1; Figure 5), we obtained an overall estimate, which favoured herbal formulations over placebo (MD 1.33, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.96; tau² = 0.29, I² = 96%; 279 infants; low‐quality evidence), indicating a significant difference in crying of more than one hour each day (P < 0.0001).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Herbal agents versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 1 Reduction in crying duration.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Herbal agents versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Reduction in crying duration.

Although the studies included in this analysis reported a statistically significant result in favour of herbal agents, the magnitude of the benefit differed across studies (tau² = 0.29, I² = 96%), probably because of the heterogeneity of the included population. In fact, these trials included children with high variability in the duration of crying at baseline (e.g. Alexandrovich 2003: 1.89 ± 0.25; Savino 2005: 3.33 ± 0.29 hours/d; Arikan 2008: 4.86 ± 1.43 hours/d). We could not exclude the risk of selection bias from two studies (Arikan 2008; Savino 2005), and we found that the risk of performance, detection and reporting bias was high in Arikan 2008.

Sensitivity analysis

When we restricted the analysis to studies in which parents were blinded (Alexandrovich 2003; Savino 2005), results remained statistically significant and favoured herbal agents (MD 1.09, 95% CI 0.11 to 2.08; tau² = 0.50, I = 98%²; 209 infants; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Herbal agents versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 2 Sensitivity: reduction in crying duration.

Responders

Results of a meta‐analysis of the three studies reporting on responders to treatment (Alexandrovich 2003; Savino 2005; Weizman 1993) suggest benefit for herbal agents over placebo (RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.56 to 2.70; 277 infants; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.3; Figure 6). Heterogeneity among studies was low (tau² = 0.01, I² = 13%), but we cannot rule out selection bias due to insufficient information from Savino 2005 and Weizman 1993.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Herbal agents versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 3 Responders.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Herbal agents versus placebo, outcome: 2.2 Responders.

Secondary outcomes

Reduction in frequency of crying episodes

Only Montaseri 2013 reported the frequency of crying episodes, but reported frequency of attacks of a particular duration: less than one hour, between one and three hours and longer than three hours. Study authors reported a statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms in favour ofFumaria extract (P < 0.05); the frequency of episodes longer than one hour seemed to be reduced in the treatment arm.

Parental or family quality of life, sleeping time, parental satisfaction

No studies assessed these outcomes.

Adverse effects

Two studies reported data on adverse effects: Alexandrovich 2003 found no adverse effects. Savino 2005 reported the following adverse effects among participants who received herbal agents: vomiting (n = 8), sleepiness (n = 2), constipation (n = 4), inappetence (n = 1) and cutaneous reactions (n = 1) (see Table 7), and the following adverse effects among those given placebo: vomiting (n = 2), sleepiness (n = 1), restlessness (n = 1), inappetence (n = 3) and constipation (n = 5).

3. Results for adverse events.

| Study | Experimental treatment | Control | Number of participants analysed (treatment/control) | Number of adverse events in treatment arm | Types of adverse events in treatment arm (number) | Number of adverse events in control arm | Types of adverse events in control arm (number) | Notes |

| Akçam 2006 | Glucose (30%) | Placebo | 25/25 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | No adverse effect |

| Alexandrovich 2003 | Fennel (oil emulsion) | Placebo | 62/59 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | No adverse effect |

| Alves 2012 | Simethicone | Mentha | 30/30 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | No adverse effect |

| Arikan 2008 | Sucrose (12%) or herbal tea (fennel) | No treatment | 35/35/35 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Blomquist 1983 | Dicyclomine plus sugar | Placebo | 18/18 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Danielsson 1985 | Simethicone | Placebo | 27/27 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gomirato 1989 | Cimetropium bromide 2.0 mg/kg | Cimetropium bromide 1.2 mg/kg | 20/20 | 4 | Constipation (4) | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Grunseit 1977 | Dicyclomine | Placebo | 22/22 | 3 | 1 | Constipation (2), loose motions (1) | Constipation (1) | ‐ |

| Hwang 1985 | Dicyclomine | Placebo | 30/30 | 4 | Drowsy (4) | 1 | Drowsy (1) | ‐ |

| Illingworth 1959 | Dicyclomine | Placebo | 16/16 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Markestad 1997 | Sucrose (12%) | Placebo | 19/19 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Metcalf 1994 | Simethicone | Placebo | 83/83 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Montaseri 2013 | Fumaria extract | Placebo | 26/24 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

| Savino 2002 | Cimetropium bromide | Placebo | 43/43 | 23 | Meteorism (8); vomiting (1); sleepiness (7); inappetence (1); cutaneous reactions (3); constipation (3) | 19 | Meteorism (12); sleepiness (1); restlessness (1); constipation (5) | ‐ |

| Savino 2005 | Herbal tea (chamomile/fennel/balm‐mint) | Placebo | 41/47 | 16 | Vomiting (8); sleepiness (2); inappetence (1); cutaneous reactions (1); constipation (4) | 12 | Vomiting (2); sleepiness (1); restlessness (1); inappetence (3); constipation (5) | ‐ |

| Sethi 1988 | Simethicone | Placebo | 26/26 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | No adverse effect |

| Weissbluth 1984 | Dicyclomine | Placebo | 24/24 | 2 | Longer sleep (1); wide‐eyed (1) | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weizman 1993 | Herbal tea (chamomile/vervain/licorices/fennel/balm‐mint) | Placebo | 33/35 | UK | ‐ | UK | ‐ | ‐ |

UK: unknown.

Comparison 3. Sugar versus placebo or no intervention