Abstract

Background

Acne vulgaris is a very common skin problem that presents with blackheads, whiteheads, and inflamed spots. It frequently results in physical scarring and may cause psychological distress. The use of oral and topical treatments can be limited in some people due to ineffectiveness, inconvenience, poor tolerability or side‐effects. Some studies have suggested promising results for light therapies.

Objectives

To explore the effects of light treatment of different wavelengths for acne.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to September 2015: the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and LILACS. We searched ISI Web of Science and Dissertation Abstracts International (from inception). We also searched five trials registers, and grey literature sources. We checked the reference lists of studies and reviews and consulted study authors and other experts in the field to identify further references to relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We updated these searches in July 2016 but these results have not yet been incorporated into the review.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs of light for treatment of acne vulgaris, regardless of language or publication status.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 71 studies, randomising a total of 4211 participants.

Most studies were small (median 31 participants) and included participants with mild to moderate acne of both sexes and with a mean age of 20 to 30 years. Light interventions differed greatly in wavelength, dose, active substances used in photodynamic therapy (PDT), and comparator interventions (most commonly no treatment, placebo, another light intervention, or various topical treatments). Numbers of light sessions varied from one to 112 (most commonly two to four). Frequency of application varied from twice daily to once monthly.

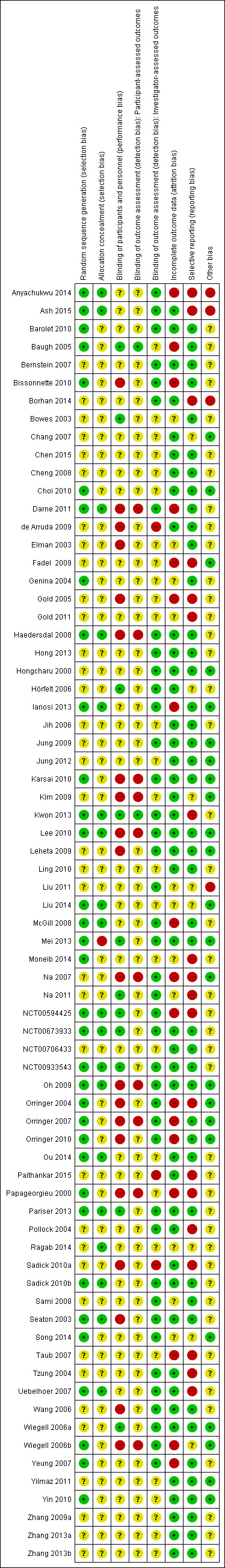

Selection and performance bias were unclear in the majority of studies. Detection bias was unclear for participant‐assessed outcomes and low for investigator‐assessed outcomes in the majority of studies. Attrition and reporting bias were low in over half of the studies and unclear or high in the rest. Two thirds of studies were industry‐sponsored; study authors either reported conflict of interest, or such information was not declared, so we judged the risk of bias as unclear.

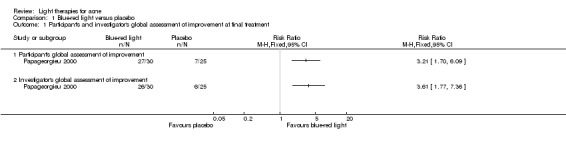

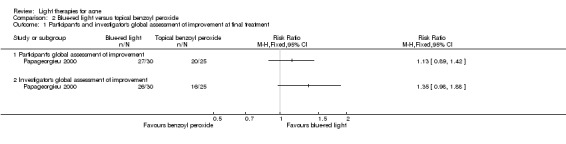

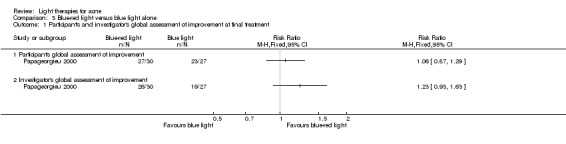

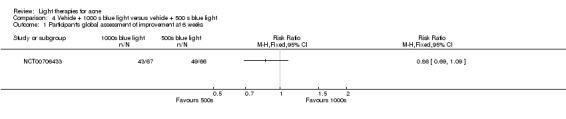

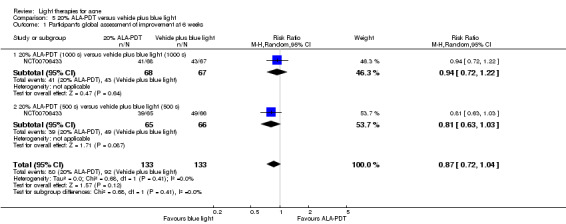

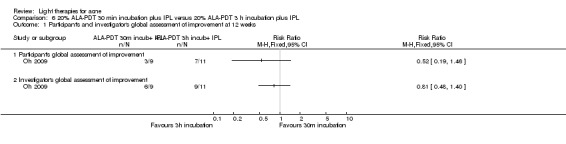

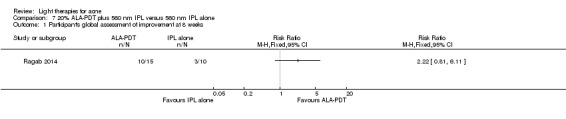

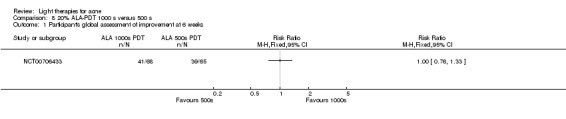

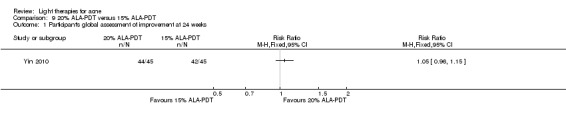

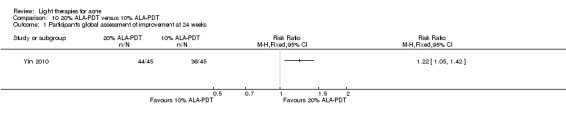

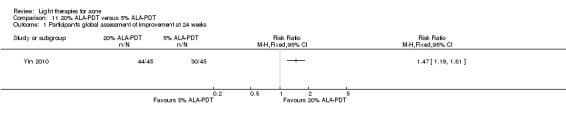

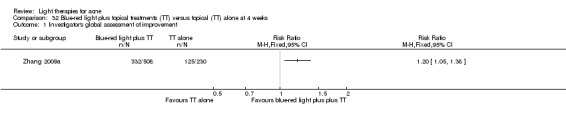

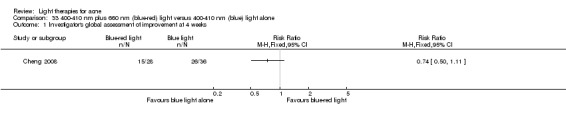

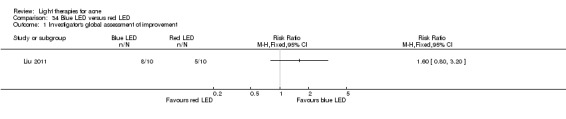

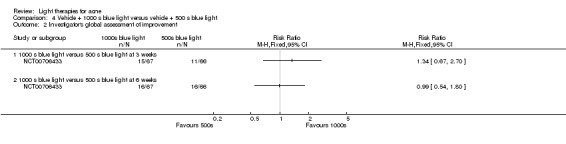

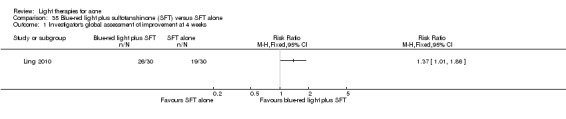

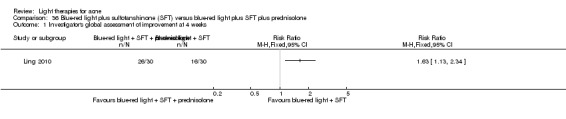

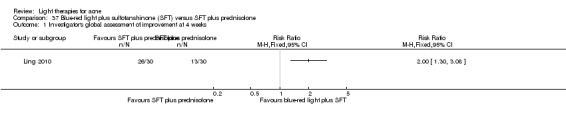

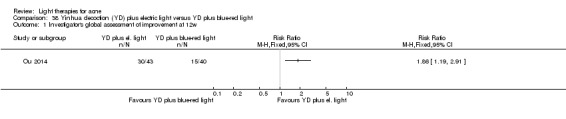

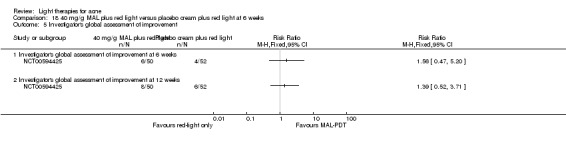

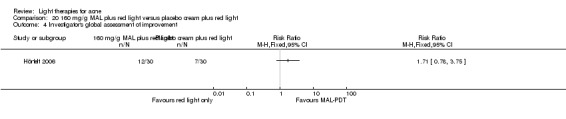

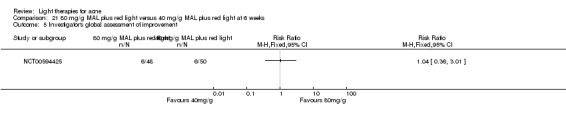

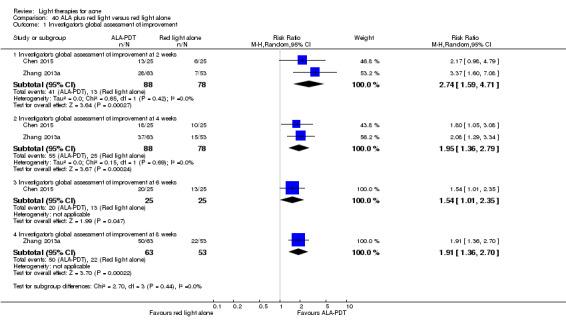

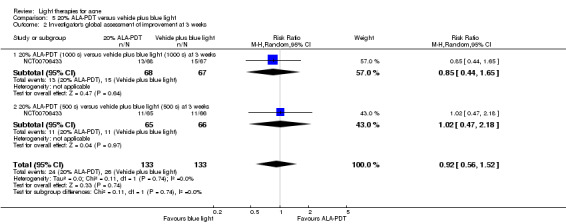

Comparisons of most interventions for our first primary outcome 'Participant's global assessment of improvement' were not possible due to the variation in the interventions and the way the studies' outcomes were measured. We did not combine the effect estimates but rated the quality of the evidence as very low for the comparison of light therapies, including PDT to placebo, no treatment, topical treatment or other comparators for this outcome. One study which included 266 participants with moderate to severe acne showed little or no difference in effectiveness for this outcome between 20% aminolevulinic acid (ALA)‐PDT (activated by blue light) versus vehicle plus blue light (risk ratio (RR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 1.04, low‐quality evidence). A study (n = 180) of a comparison of ALA‐PDT (activated by red light) concentrations showed 20% ALA was no more effective than 15% (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.15) but better than 10% ALA (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.42) and 5% ALA (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.81). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) was 6 (95% CI 3 to 19) and 4 (95% CI 2 to 6) for the comparison of 20% ALA with 10% and 5% ALA, respectively.

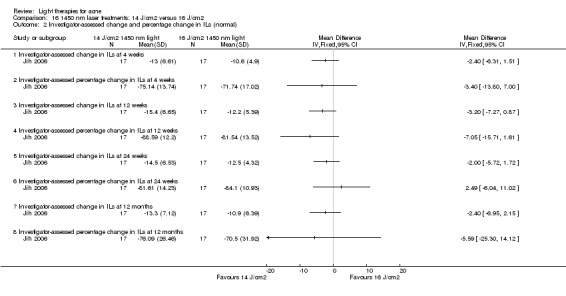

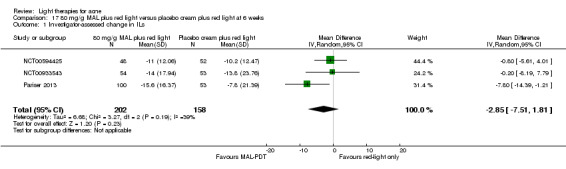

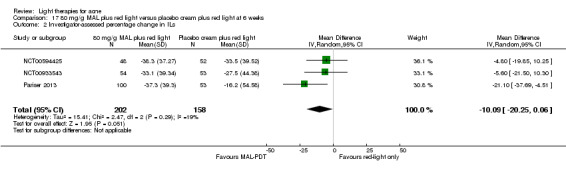

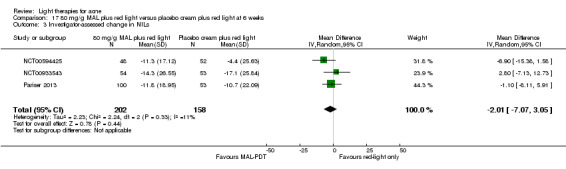

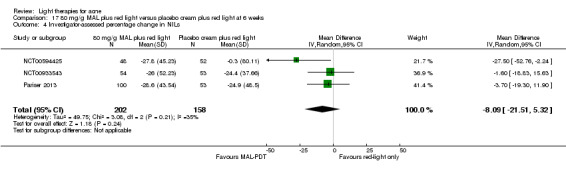

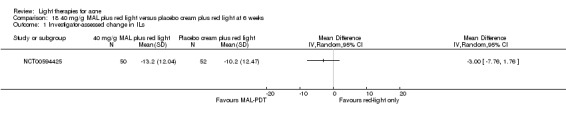

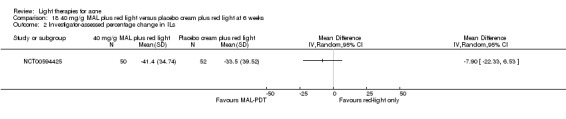

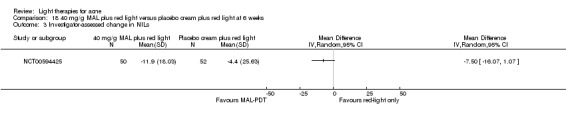

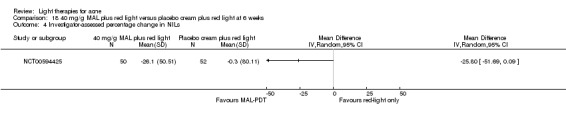

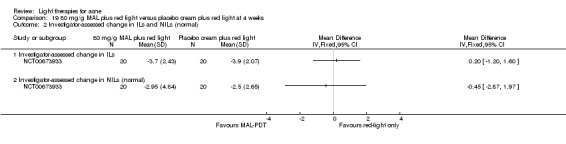

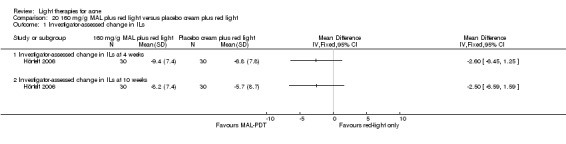

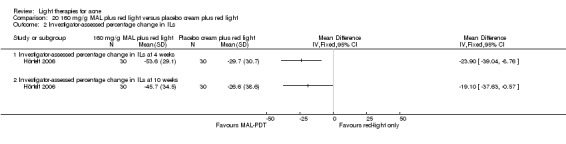

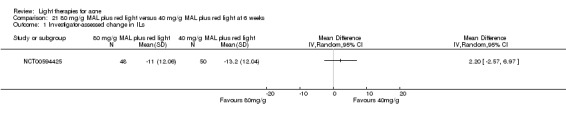

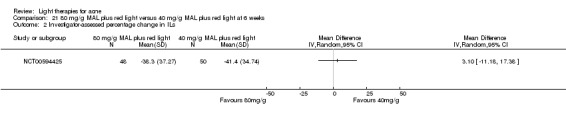

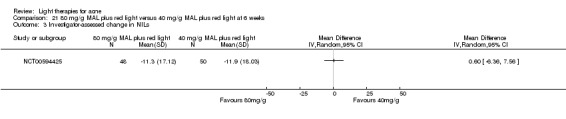

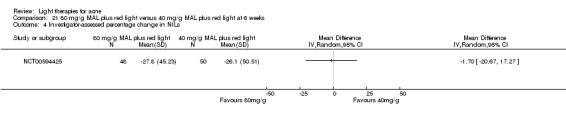

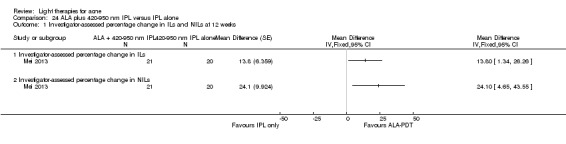

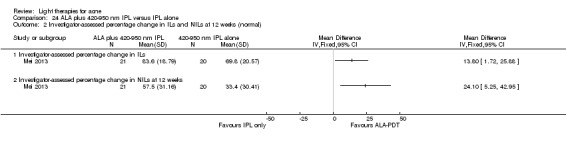

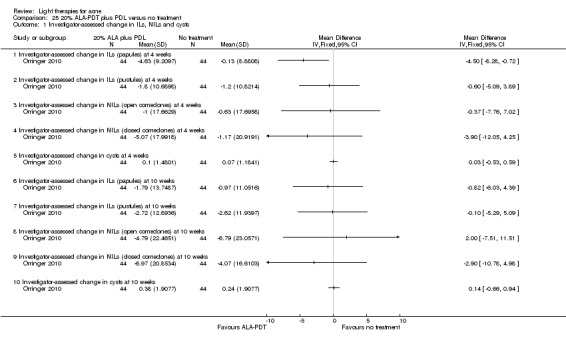

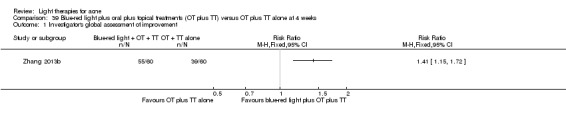

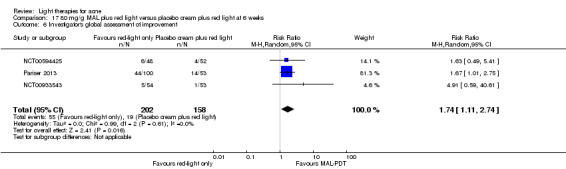

For our second primary outcome 'Investigator‐assessed changes in lesion counts', we combined three RCTs, with 360 participants with moderate to severe acne and found methyl aminolevulinate (MAL) PDT (activated by red light) was no different to placebo cream plus red light with regard to change in inflamed lesions (ILs) (mean difference (MD) ‐2.85, 95% CI ‐7.51 to 1.81), percentage change in ILs (MD ‐10.09, 95% CI ‐20.25 to 0.06), change in non‐inflamed lesions (NILs) (MD ‐2.01, 95% CI ‐7.07 to 3.05), or in percentage change in NILs (MD ‐8.09, 95% CI ‐21.51 to 5.32). We assessed the evidence as moderate quality for these outcomes meaning that there is little or no clinical difference between these two interventions for lesion counts.

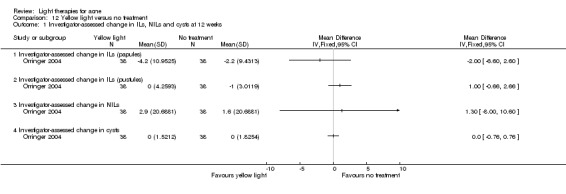

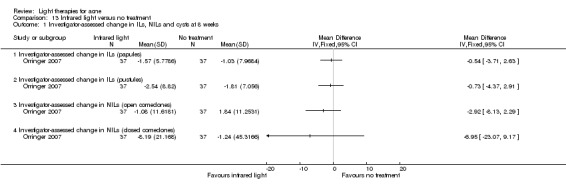

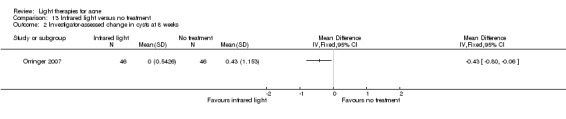

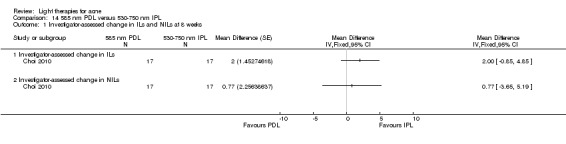

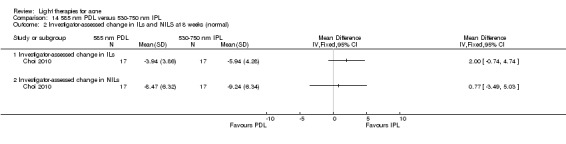

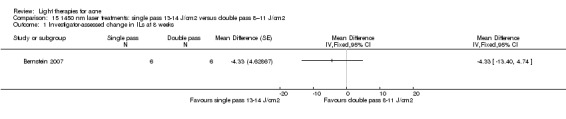

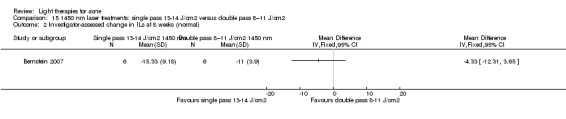

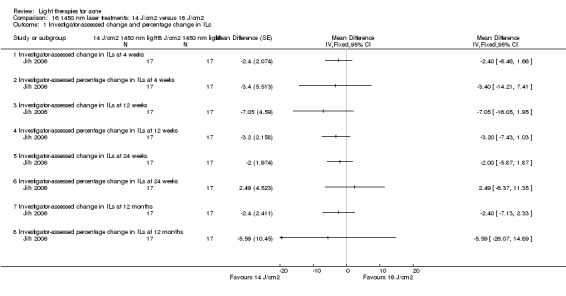

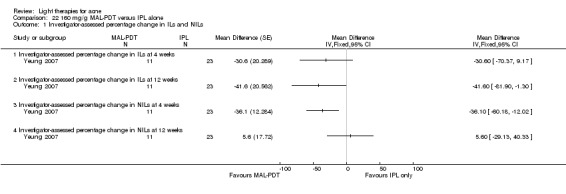

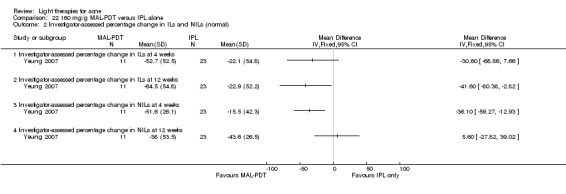

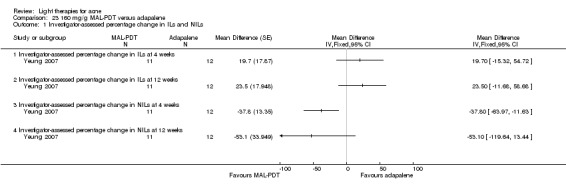

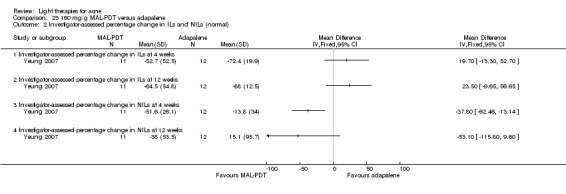

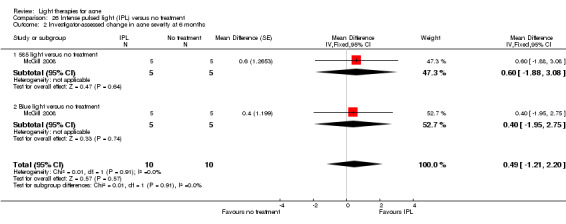

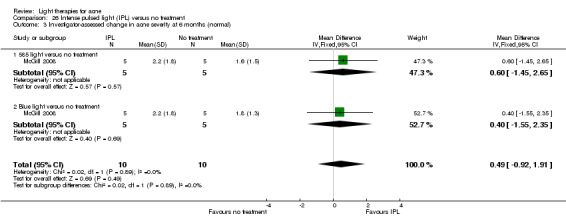

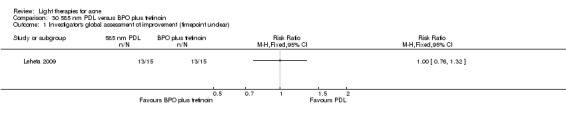

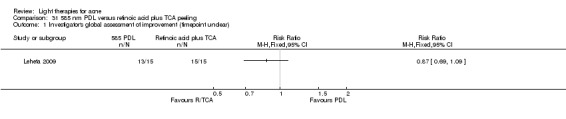

Studies comparing the effects of other interventions were inconsistent or had small samples and high risk of bias. We performed only narrative synthesis for the results of the remaining trials, due to great variation in many aspects of the studies, poor reporting, and failure to obtain necessary data. Several studies compared yellow light to placebo or no treatment, infrared light to no treatment, gold microparticle suspension to vehicle, and clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide combined with pulsed dye laser to clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide alone. There were also several other studies comparing MAL‐PDT to light‐only treatment, to adapalene and in combination with long‐pulsed dye laser to long‐pulsed dye laser alone. None of these showed any clinically significant effects.

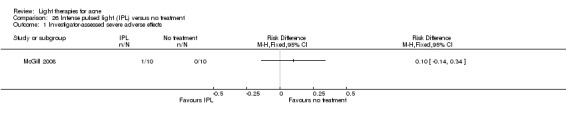

Our third primary outcome was 'Investigator‐assessed severe adverse effects'. Most studies reported adverse effects, but not adequately with scarring reported as absent, and blistering reported only in studies on intense pulsed light, infrared light and photodynamic therapies. We rated the quality of the evidence as very low, meaning we were uncertain of the adverse effects of the light therapies.

Although our primary endpoint was long‐term outcomes, less than half of the studies performed assessments later than eight weeks after final treatment. Only a few studies assessed outcomes at more than three months after final treatment, and longer‐term assessments are mostly not covered in this review.

Authors' conclusions

High‐quality evidence on the use of light therapies for people with acne is lacking. There is low certainty of the usefulness of MAL‐PDT (red light) or ALA‐PDT (blue light) as standard therapies for people with moderate to severe acne.

Carefully planned studies, using standardised outcome measures, comparing the effectiveness of common acne treatments with light therapies would be welcomed, together with adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.

Plain language summary

The use of light as a therapy for acne

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out whether treatment using lasers and other light sources improves the whiteheads and blackheads, and inflamed spots that people with acne have. We also wanted to know how people with acne assessed their own improvement, and whether they found that these therapies caused unpleasant effects like blistering or scarring. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer these questions and found 71 studies, with a total of 4211 participants.

What was studied in this review?

Acne is a common skin problem. It causes blackheads, whiteheads and inflamed spots, and may lead to scarring. Current treatment options are limited in their effectiveness and convenience, and may cause side‐effects. We investigated lasers and other light sources, which are used as an alternative therapy, either on their own or in combination with a chemical that makes the skin more sensitive to the light source (photodynamic therapy (PDT)). We compared different light therapies with other treatment options, no treatment, or placebo.

Most studies included people with mild to moderate acne in their twenties. Light treatments in these studies varied greatly in many important aspects, such as wavelength of light used, duration of treatment, chemicals used in photodynamic therapy, and others.

Over half of the studies were industry sponsored; study authors reported either conflict of interest, or such information was not declared.

Key messages

We are unable to draw firm conclusions from the results of our review, as it was not clear whether the light therapies (including PDT) assessed in these studies were more effective than the other comparators tested such as placebo, no treatment, or treatments rubbed on the skin, nor how long the possible benefits lasted.

What are the main results of this review?

We investigated how people with acne assessed their own improvement, but it was not clear whether the light therapies in the studies had a beneficial effect. Evidence on how investigators assessed changes in numbers of blackheads, whiteheads and inflamed spots in people with acne was also limited for most types of light therapies, due to variation in the way the studies were conducted and measured.

Most studies reported side‐effects, but not adequately. Scarring was reported as absent, and blistering was reported in studies on intense pulsed light, infrared light and on PDT.

Three studies, with a total of 360 participants with moderate to severe acne, showed that photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolevulinate (MAL), activated by red light, had a similar effect on changes in numbers of blackheads, whiteheads and inflamed spots when compared with placebo cream with red light. We judged the quality of this evidence moderate.

Future well planned studies comparing the effectiveness of common acne treatments with light therapies are needed to assess the true clinical effects and side‐effects of light therapies for acne.

How up to date is this review?

This review included studies up to September 2015.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Light therapies (including photodynamic therapy) compared to placebo, no treatment, topical treatment and other comparators for acne vulgaris.

| Light therapies (including photodynamic therapy) for acne vulgaris | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Mild, moderate and severe acne vulgaris

Settings: Single and multicentre, worldwide

Intervention: Light therapies including photodynamic therapy Comparison: Placebo, no treatment, topical treatment and other comparators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Light therapies | |||||

| Participant's global assessment of improvement Non‐standardised scales Follow‐up: up to 24 weeks after final treatment | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 1033 (23 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | We decided not to combine the effect estimates from the different interventions. We instead rated the quality of the evidence based on the GRADE considerations. The direction and size of effect across the individual study results across the 38 different comparisons were inconsistent. 13 studies used Likert or Likert‐like scales, 5 visual analogue scales, 3 other methods and in 2 studies it was unclear which method was used. In many studies last evaluation at final treatment, timing of assessment unclearly reported or not reported. 13 studies had split‐face design, 8 parallel‐group design, 2 split faces within parallel‐group design.4,5 |

| Investigator‐assessed change in lesion counts Lesion counts Follow‐up: up to 12 months after final treatment | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 2242 (51 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | We decided not to combine the effect estimates from the different interventions. We instead rated the quality of the evidence based on the GRADE considerations. The direction and size of effect across the individual study results across the 76 different comparisons were inconsistent. Different methods for lesion counting reported including change or percentage change from baseline in the number of individual or various aggregates of counts of inflamed lesions, non‐inflamed lesions, nodules and cysts. 22 studies had split‐face design, 1 split‐face or back design, 2 split‐back design, 19 parallel‐group design, 7 split‐face within parallel‐group design.4,5 |

| Investigator‐assessed severe adverse effects Blistering or scarring Follow‐up: up to 12 months after final treatment | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 3945 (66 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | We decided not to combine the effect estimates from the different interventions. We rated the quality of the evidence based on the GRADE considerations. In most studies it was reported that adverse effects were recorded, without stating explicit intent to record blistering and scarring. No reports of scarring in any of the studies. No reports of blistering in 56 studies with a total of 3378 participants. Blistering was reported in two studies on infrared light and one study on intense pulsed light6, as well as in seven studies on photodynamic therapies (PDT)7. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

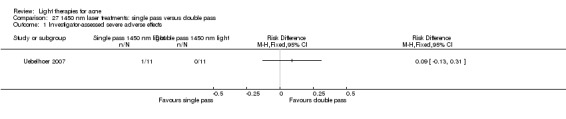

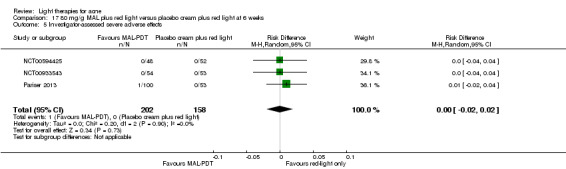

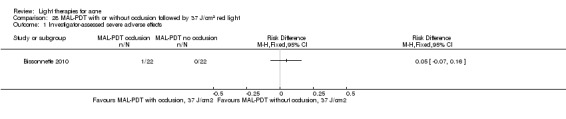

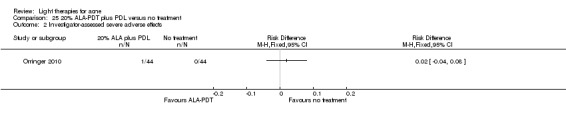

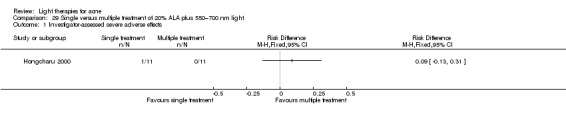

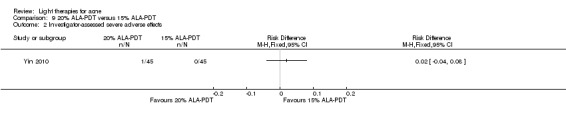

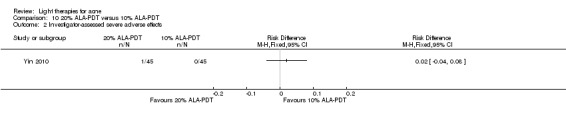

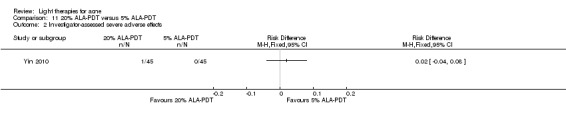

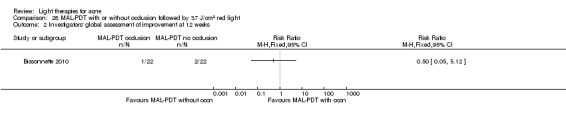

1 We downgraded by one level because of risk of bias: unclear to high overall risk of bias in the majority of studies. 2 We downgraded by one level because of indirectness: lack of comparisons with conventional treatments. Limited generalisation due to variation of participants (such as Fitzpatrick skin types, severity of acne etc.). 3 We downgraded by one level because of imprecision: small sample sizes (median of 24 for 'Participant's global assessment of improvement', and median of 30 for studies on each of the other two outcomes), power calculations not reported, often unclear assignment to groups or face sides. 4 We have not downgraded further because of inconsistency, but there was heterogeneity across studies due to diversity of populations, interventions, comparators and methods of outcome assessment. 5 We have not downgraded further because of publication bias, however our searches identified considerable number of unpublished studies, but with no available data. 6 Three split‐face trials; one included two reports on the infrared treated sides 2/46 (4.3%) and no reports on the untreated sides (0%); one included one report on the single pass 1450 nm laser‐treated side 1/11 (9%) and no reports on the double pass 1450 nm laser‐treated sides (0%); one study included one report on the intense pulsed light (IPL)‐treated sides 1/10 (10%) and no reports on the untreated sides (0%). 7 Three studies on methyl aminolevulinate (MAL)‐PDT, (one of which is presented in Summary of findings table 2), the second was a split‐face within parallel‐group trial included one report on the 37 J/cm² 80 mg/g MAL‐PDT with occlusion 1/22 (4.5%) sides and no reports on the 37 J/cm² 80 mg/g MAL‐PDT without occlusion sides (0%), nor on the 25 J/cm² 80 mg/g MAL‐PDT with or without occlusion sides (0%). Further split‐face study included one report on 160 mg/g MAL‐PDT sides 1/30 (3%), and no reports on red‐light‐only control sides. Four 20% aminolevulinic acid (ALA )‐PDT studies: one split‐face trial included one report 1/44 (2.3%) on the sides with pulsed dye laser (PDL) used for activation and no reports on the untreated sides. One split‐back within parallel‐group included one report 1/11 (9%) in the single‐treatment group on back sites with 550–700 nm light used for activation, and no reports in the multiple treatment groups on the ALA‐PDT, nor ALA alone, light alone or untreated back sites in any of the groups. One parallel‐group trial included one report in the arm which used a combination of IPL of 580–980 nm and bipolar radiofrequency energies for activation, and no reports in the arms which used 517 nm light or IPL‐alone (600–850 nm) for activation; the number of participants per group unclear. One parallel‐group trial included one report in the arm which used 20% ALA 1/45 (2%) and no reports (0%) in arms with 5%, 10% nor 15% ALA activated by 633 nm light.

Summary of findings 2. MAL‐PDT compared to red light only for acne vulgaris.

| MAL‐PDT compared to red light only for acne vulgaris | ||||||

| Patient or population: Moderate and severe acne vulgaris Settings: Multicentre, USA and Canada Intervention: 80 mg/g methyl aminolevulinate (MAL) PDT activated by red light Comparison: Placebo cream with red light | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Red light only | MAL‐PDT | |||||

| Paticipant's global assessment of improvement ‐ Not measured | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Investigator‐assessed change in inflamed lesions (ILs) Lesion counts Follow‐up: 6 weeks after final treatment | Baseline mean ILs count in the red‐light‐only groups was 39.9; the mean investigator‐assessed change in ILs in the red‐light‐only groups was ‐10.6 | Baseline mean ILs count in the MAL‐PDT group was 39.2; the mean investigator‐assessed change in ILs in the MAL‐PDT groups was 2.85 lower (7.51 lower to 1.81 higher) | ‐ | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Two additional trials not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Assumed risk is based on weighted average of the mean ILs counts in the control groups and the corresponding risk on weighted average of the mean ILs counts in the intervention groups of the three studies2,3,4 |

| Investigator‐assessed change in non‐inflamed lesions (NILs) Lesion counts Follow‐up: 6 weeks after final treatment | Baseline mean NILs count in the red‐light‐only groups was 47.6; the mean investigator‐assessed change in NILs in the red‐light‐only groups was ‐10.8 | Baseline mean NILs count in the MAL‐PDT group was 45.6; the mean investigator‐assessed change in NILs in the MAL‐PDT groups was 2.01 lower (7.07 lower to 3.05 higher) | ‐ | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Two additional trials not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Assumed risk is based on weighted average of the mean NILs counts in the control groups and the corresponding risk on the weighted average of the mean NILs counts in the intervention groups of the three studies2,3,4 |

| Investigator‐assessed percentage change in ILs Lesion counts Follow‐up: 6 weeks after final treatment | Baseline mean ILs count in the red‐light‐only groups was 39.9; the mean investigator‐assessed percentage change in ILs in the red‐light‐only groups was ‐25.7% | Baseline mean ILs count in the MAL‐PDT group was 39.2; the mean investigator‐assessed percentage change in ILs in the MAL‐PDT groups was 10.09 lower (20.25 lower to 0.06 higher) | ‐ | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Two additional trials not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Assumed risk is based on weighted average of the mean ILs counts in the control groups and the corresponding risk on the weighted average of the mean ILs counts in the intervention groups of the three studies2,3,4 |

| Investigator‐assessed percentage change in NILs Lesion counts Follow‐up: 6 weeks after final treatment | Baseline mean NILs count in the red‐light‐only groups was 47.6; the mean investigator‐assessed percentage change in NILs in the red‐light‐only groups was ‐16.6% | Baseline mean ILs count in the MAL‐PDT group was 45.6; the mean investigator‐assessed percentage change in NILs in the MAL‐PDT groups was 8.09 lower (21.51 lower to 5.32 higher) | ‐ | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Two additional trials not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Assumed risk is based on weighted average of the mean NILs counts in the control groups and the corresponding risk on the weighted average of the mean NILs counts in the intervention groups of the three studies2,3,4 |

|

Investigator‐assessed severe adverse effects Application site blister Follow‐up: during whole study period |

Study population | Not estimable | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Scarring was not reported. Two additional trials not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Due to the lack of events occurring in both groups, the relative risk is unreliable2,3,4 | |

| Application site blister rates in the red‐light‐only groups were 0/158 (0%) | Application site blister rates in the MAL‐PDT groups were 1/202 (0.5 %) | |||||

| Investigator's global assessment (IGA) of improvement Treatment 'success' as defined by IGA score decrease5 Follow‐up: 6 weeks after final treatment | Study population | RR 1.74 (1.11 to 2.74) | 360 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | The absolute effect was 89 more per 1000 (95% CI 13 more to 209 more). The number needed to treat for an additional treatment 'success' was 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).2,3,4 An additional trial not included due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. |

|

| 120 per 1000 | 209 per 1000 (133 to 329) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded by one level because of indirectness: comparisons with no treatment, placebo or conventional treatments not included. 2 We have not downgraded because of risk of bias. Please note that these were industry‐sponsored studies, so we judged 'other bias' as unclear. NCT00594425 had high attrition and selective reporting bias. Low risk in all other bias domain for all three studies. 3 We have not downgraded because of inconsistency. There was some clinical heterogeneity across studies to take into account, in one study only participants with severe acne were included, in the other two studies participants with both moderate and severe acne were included (less than 20% of the included participants had severe acne in those trials). 4 The three studies included 53, 53,and 52 participants in the control group and 100, 54 and 48 participants in the intervention group respectively. 5 1 = almost clear; 2 = mild severity; 3 = moderate severity; 4 = severe. Success defined as improvement of at least two grades from baseline.

Summary of findings 3. ALA‐PDT compared to blue light only for acne vulgaris.

| ALA‐PDT compared to blue light only for acne vulgaris | ||||||

| Patient or population: Moderate and severe acne vulgaris Setting: Multicentre, USA Intervention: 20% aminolevulinic acid (ALA) activated by 500 s and 1000 s blue light Comparison: Vehicle plus 500 s and 1000 s blue light | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with blue light only | Risk with ALA‐PDT | |||||

|

Participant's global assessment of improvement Non‐standardised scale5 Follow up: 6 weeks |

Study population | RR 0.87 (0.72 to 1.04) | 266 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

Results for 500 s ALA and 1000 s ALA groups combined under 'Intervention', as our analyses found no statistically significant difference between them. 1000 s vehicle plus blue light and 500 s vehicle plus blue light groups combined in 'Comparison' , as our analyses found no statistically significant difference between them. | |

| 602 per 1000 | 523 per 1000 (433 to 626) | |||||

| Investigator‐assessed change in inflamed lesions (ILs) Lesion counts Follow up: 6 weeks | Not estimable. See comment. | Not estimable. See comment. | Not estimable | 266 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 |

Means not reported nor provided upon request. The median investigator‐assessed change (standard deviation, SD) in ILs was ‐21.0 (23.63) in the vehicle 1000 s, ‐17.0 (26.71) in the vehicle 500 s group, ‐18.5 (30.15) in the ALA 1000 s and ‐13.0 (28.74) in the ALA 500 s group. |

|

Investigator‐assessed percentage change in ILs Lesion counts Follow up: 6 weeks |

Not estimable. See comment. | Not estimable. See comment. | Not estimable | 266 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 |

Means not reported nor provided upon request. The median investigator‐assessed percentage change (SD) in ILs was ‐48.4 (32.81) in the vehicle 1000 s, ‐45.2 (50.15) in the vehicle 500 s group, ‐34.4 (37.8) in the ALA 1000 s group and ‐29.0 (42.57) in the ALA 500 s group. |

|

Investigator‐assessed severe adverse effects Application site blister Follow‐up: during whole study period |

Study population | Not estimable | 266 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,4 |

"Oozing/Vesiculation/Crusting" were evaluated at baseline, and were then assessed pre‐ and post‐treatment & 48 h after treatment at each treatment session, as well as 3 and 6 weeks after final treatment. | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

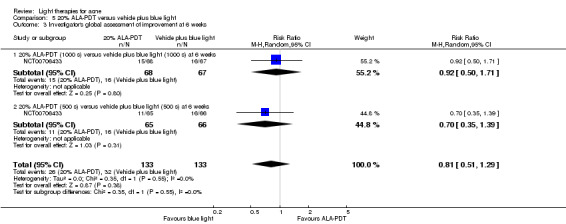

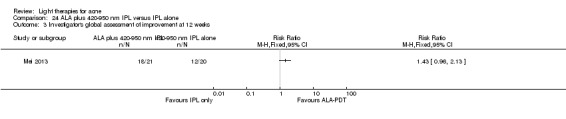

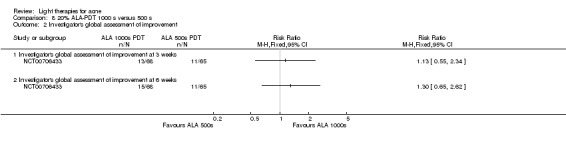

| Investigator's global assessment (IGA) of improvement Treatment 'success' as defined by IGA score decrease6 Follow up: 6 weeks | Study population | RR 0.81 (0.51 to 1.29) | 266 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

Results for 1000 s ALA and 500 s ALA groups combined under 'Intervention', as our analyses found no statistically significant difference between them. 1000 s vehicle plus blue light and 500 s vehicle plus blue light groups combined in 'Comparison', as our analyses found no statistically significant difference between them. | |

| 195 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (100 to 252) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded by one level because of indirectness: comparisons with no treatment, placebo or conventional treatments not included. 2 We have downgraded by one level because of risk of bias. 3 We have downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias. Means and 95% CIs were not reported. 4 We have downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias. There were no reports of application site blisters among adverse effects, however it is possible that some occurred, but it is impossible to separate those as they were reported together with oozing and crusting under "Oozing/ Vesiculation/Crusting". 5 Excellent = very satisfied; good = moderately satisfied; fair = slightly satisfied; poor = not satisfied at all. Success defined as improvement of at least two grades from baseline. 6 0 = clear skin with no ILs or NILs; almost clear; rare NILs with no more than a few small ILs; Mild; > Grade 1 = some NILs with some ILs (papules/pustules only; no nodules); Moderate; > Grade 2 = up to many NILs and a moderate number of ILs but no more than one small nodule; Severe; > Grade 3 = up to many NILs and ILs, but no more than a few nodules. Success was defined as a two‐point or more improvement on the IGA scale since baseline'

Background

Description of the condition

Acne is a very common inflammatory skin condition that affects the face of over 90% of people some point in their lives, the chest in 60% of people, and the back in 15% (Cunliffe 1989). The condition usually starts in adolescence and frequently resolves by the mid‐twenties (Bhate 2013; Burton 1971).

Acne is characterised by an increase in sebum production; the formation of lesions called open and closed comedones (which appear as blackheads and whiteheads); raised red spots, known as papules and pustules and in more severe cases nodules; deep pustules; and cysts (Degitz 2007; Nast 2012). Acne can range from a mild form, with a few of these lesions, to more severe forms embracing multiple lesions over the face and trunk (O'Brien 1998).

Mild acne is more prevalent than the severe form (Kilkenny 1998). In some cases, acne persists, or initially starts, in adulthood, and in this situation, it is seen more commonly in adult women than men (Choi 2011; Dreno 2013; Preneau 2012; Williams 2006).

Impact

Acne results in a significant burden. One study from the USA indicated that the prevalence by the mid‐teens was virtually 100% (Stern 1992). A more recent European study estimated a rate to be 82.4% in 10 to 12 year olds and identified that over 40% of people sought treatment (Amado 2006).

The duration of acne can be anything from 5 to 10 years (Cunliffe 1979). In most people, acne has resolved by the age of 25 years (Cunliffe 1979). Between 7% and 17% of those affected have clinical acne beyond this time (Goulden 1997).

Acne can produce significant psychological and social problems, and those having acne may be affected by lower self‐esteem, anxiety, depression, and low mood (Baldwin 2002; Tan 2004; Thomas 2004). Scarring is a very common problem, and treatment is extremely difficult (Jordan 2000; Layton 1994; Tan 2010); scarring can also result in significant psychological and social problems (Hayashi 2015).

The treatments available for acne may result in adverse effects, which may limit their use (Nast 2012; Williams 2012). The complex pathophysiology of acne often results in the need for multiple treatments within any given regimen, and this can have impact on adherence (Dreno 2010; Krejci‐Manwaring 2006). There is increasing concern about the use of antibiotics in the management of acne due to emerging bacterial resistance (Coates 2002).

Causes

Acne usually presents around puberty and arises as a result of an increase in hormone levels, particularly androgen hormones (Thiboutot 2004; Zouboulis 2004). This leads to enlargement of the sebaceous (grease) glands and an increased cell turnover resulting in blockage and plugging of the duct that carries the sebum to the skin, which leads to the formation of a comedone (whiteheads and blackheads, Cunliffe 2004). Skin bacteria, in particular Propionibacterium acnes (P acnes), become trapped within the duct, and an intense inflammatory reaction ensues, which results in the inflamed skin lesions characteristic to acne, that is, the pustules, papules, and in the worst cases, nodules and cysts (Degitz 2007; Nast 2012). Insulin resistance is one factor implicated in the development of severe acne and is a common complaint of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (Archer 2004; Pfeifer 2005).

Conventional treatments

First‐line treatments in Europe include fixed combinations of benzoyl peroxide (BPO) with adapalene or clindamycin for mild‐to‐moderate papulopustular acne, whereas isotretinoin is recommended for more severe forms of acne (Nast 2012). Recent guidelines published by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) also recommend BPO or topical retinoid, or topical combination therapy including BPO with or without antibiotic for mild acne, however separate components, as well as fixed combination products may be prescribed (Zaenglein 2016). Topical combination therapy for moderate acne may also be prescribed together with an oral antibiotic for moderate and severe acne as a first line treatment (Zaenglein 2016). As in Europe, isotretinoin is only recommended for more severe forms of acne as a first line treatment (Zaenglein 2016). Systemic antibiotics in combination with adapalene, azelaic acid, or a fixed combination of adapalene and BPO are recommended for more severe forms of acne (Nast 2012).

For mild‐to‐moderate acne, second‐line treatments in Europe include topical treatments such as azelaic acid, BPO, or topical retinoids; however, systemic antibiotics in combination with adapalene can also be considered (Nast 2012). Alternative treatment suggested by the AAD guidelines for mild forms of acne include adding topical retinoid or BPO if they have not been part of the combination already, and considering alternate retinoid or topical dapsone (Zaenglein 2016). Alternative treatment for moderate forms of acne include alternating combination therapies, whereas, for both moderate and severe acne, changes in oral antibiotics, adding combined oral contraceptive or oral spironolactone for women, as well as oral isotretinoin may be considered (Zaenglein 2016).

Topical treatments target the plugged follicle and the bacteria implicated in acne as well as inflammation (Nast 2012). It is now recommended that topical antibiotics should not be used alone as they can lead to antibiotic resistance (Nast 2012). All antibiotics employed for acne should be used alongside anti‐resistant agents in the treatment of moderate acne, that is, agents that reduce antibiotic‐resistant strains of P acnes and avoid emergence of novel resistant strains (Nast 2012).

Women with acne may be prescribed hormone therapies, which are also used as combined oral contraceptives (Arowojolu 2012; Zaenglein 2016). Oral isotretinoin, which is a synthetic form of vitamin A, is very effective for moderate nodular and severe papulopustular acne (Nast 2012). For the majority of people following a course of isotretinoin, their skin clears fully by the end of a course of therapy; however, in some cases, the acne will recur (White 1998). Side‐effects from oral isotretinoin include dry lips, eyes, skin, and mucous membranes (Charakida 2004). Isotretinoin is also teratogenic, meaning that if a woman becomes pregnant whilst taking isotretinoin, it is likely to cause birth defects (Lammer 1985). This limits its use in women of childbearing age (Abroms 2006; Stern 1989).

Description of the intervention

Light therapies utilise light with different properties (wavelength, intensity, coherent or incoherent light) with the aim of achieving a beneficial result for those with acne (Haedersdal 2008a; Mariwalla 2005). Lasers (Light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) (Leinwoll 1965) are the most common light sources that have been used for acne therapy. Lasers produce a high‐energy beam of light of a precise wavelength range, which can be focused accurately (Haedersdal 2008a; Mariwalla 2005). Several different delivery systems are used, incorporating timing controls for safety, and cooling systems to reduce discomfort during treatment (Haedersdal 2008a; Hamilton 2009; Mariwalla 2005).

How the intervention might work

The exact mechanisms of action for light therapies are still not fully understood, but three components of the intervention are considered crucial: light, photosensitisers (i.e. molecules that absorb and are then activated by light), and oxidative stress resulting from their activation (Fritsch 1998; Mariwalla 2005; Sakamoto 2010). Photosensitisers can be produced endogenously or applied exogenously (Fritsch 1998). Probable biological consequences of oxidative stress include damaging bacteria and sebaceous glands, together with reduction of follicular obstruction and hyperkeratosis (Mariwalla 2005; Sakamoto 2010). Possible interference with the immunological response, not necessarily mediated by photosensitisers, are also believed to be important (Sakamoto 2010).

Different wavelengths have different effects on P acnes bacterial colonies in vitro (Cho 2006). However, the evidence on in vivo reduction of P acnes is limited, although different light therapies have had different effects on outcomes in clinical trials (Haedersdal 2008a; Hamilton 2009).

P acnes produces endogenous porphyrins, which absorb light to form a highly reactive singlet oxygen, which destroys the bacteria (Mariwalla 2005). The peak absorption occurs at blue light wavelengths, providing a rationale for selecting blue light as a logical wavelength when using physical therapy for acne (Mariwalla 2005). However, red light is also absorbed by porphyrins and can penetrate deeper into the skin where it may directly affect inflammatory mediators (Mariwalla 2005; Ross 2005). Other light therapies, including infra‐red lasers, low energy pulsed‐dye lasers (PDL), and radiofrequency devices (Mariwalla 2005), are directed towards damaging sebaceous glands, reducing their size and thus sebum output (Lloyd 2002). Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses specific light‐activating topical products, consisting of various porphyrin precursors, most commonly 5‐aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and its methyl‐ester methyl‐aminolevulinate (MAL) (Sakamoto 2010a). These are absorbed into the skin and amplify the response to light therapy, but in so doing, tend to produce more side‐effects (Sakamoto 2010a).

Since the 1970s the mechanism of action of PDT has been better known for the treatment of malignancies than for other uses in dermatology (Fritsch 1998; Sharma 2012). Photosensitisers used in PDT probably accumulate inside gram‐positive bacteria (such as P acnes), and when activated, a type I reaction is induced, producing hydroxyl radicals, a leak‐out of cellular contents, and death of the microbial cells (Sharma 2012). Differences in pharmacokinetic characteristics of drugs used in PDT, their incubation time, whether they were administered under occlusion or not, their ability to penetrate the intrafollicular duct, alongside wavelengths and doses of light used for activation, as well as care applied before and after the treatment, are all confounding factors likely to affect clinical results (Sakamoto 2010a). Sakamoto et al suggested two dose‐related PDT mechanisms of action: 'low dose' PDT ('low drug concentration, low light fluence, short incubation time between drug application and light exposure, use of blue light with minimal penetration depth, and/or various pulsed source exposures') is probably mainly based on transient antimicrobial or immunomodulatory effects, whereas 'high dose' PDT ('prolonged application of high ALA concentration followed by high fluence red light') is based mainly on damaging sebaceous glands (Sakamoto 2010). Optimal regimens have not yet been established (Sakamoto 2010a). There is an ongoing debate on whether lack of selectivity of the photosensitisers could lead to substantial damage to the surrounding tissue and subsequent necrosis (Sharma 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Current treatment options may be limited in effectiveness or acceptability due to adverse effects, poor tolerability and the inconvenience of using them on a regular and prolonged basis (Nast 2012; Williams 2012; Zaenglein 2016). Conventional treatments have limitations. Most oral and topical treatments are less effective than oral isotretinoin, but the latter has significant adverse effects (Nast 2012; Williams 2012). Combination regimens, which are required for the treatment of acne, are often complex for a person to use, are time‐consuming, and can result in poor adherence (Dreno 2010). Increasing concern about the use of antibiotics for acne has emerged due to the rise in antibiotic‐resistant bacteria (Nast 2012). If we were able to identify alternative therapies that addressed some of these issues, it would clearly be advantageous to patients, the wider community, and prescribers. This is highlighted by the fact that the Acne Priority Setting Partnership, which received responses from over 8000 clinicians, patients, and carers placed the question of safety and effectiveness of physical therapies, including lasers and other light‐based treatments, in treating acne among the top 10 research priorities (Layton 2015). Light therapies seem to be increasingly popular, and many light sources are now offered for people to purchase directly using the Internet. Therefore, there is a lot of public interest in this treatment, as well as interest from health service commissioners.

To date, the evidence regarding the efficacy of light and laser interventions is not robust (Nast 2012; Zaenglein 2016 ). There have been few studies comparing lasers and light therapies with conventional acne treatments, or studies using physical therapies in severe acne, or any evaluation of the long‐term benefit of these treatments (Hamilton 2009), and so there is still uncertainty and controversy (Sanclemente 2014; Williams 2012). European guidelines (Nast 2012) gave negative recommendations for artificial ultraviolet (UV) radiation in mild, moderate, and severe papulopustular acne and for visible light as monotherapy in severe papulopustular acne. Blue light monotherapy is recommended with a low strength of recommendation for treatment of mild to moderate papulopustular acne (Nast 2012). Because of a lack of evidence, Nast 2012 left recommendations open for visible light of other wavelengths as monotherapy, lasers with infrared wavelengths, intense pulsed light (IPL), and PDT for mild to moderate and severe papulopustular acne. This is somewhat contradictory to the European guidelines for topical PDT, where inflammatory and infectious dermatoses are seen as an "emerging indication", and acne has the highest strength of recommendation, with the evidence rated as of highest possible quality (Morton 2013). Recently updated American guidelines included lasers and PDT as a new clinical question, but are not explicit in stating the strength of their recommendation, nor levels of underlying evidence (Zaenglein 2016). The study authors concluded that there was "limited evidence to recommend the use and benefit of physical modalities for the routine treatment, including pulsed dye laser..." and that "Some laser and light devices may be beneficial for acne, but additional studies are needed" (Zaenglein 2016). Zaenglein 2016 have also included clinical trials of lasers and light‐based therapies as one of the most important current research and knowledge gaps to address in acne treatment.

The worldwide market potential for anti‐acne skin preparations alone was estimated to be USD 3300 million in 2013 (GMR Data 2013). The growing market and the willingness of people to take up treatments that have not been clinically proven to be effective means that research into the use and marketing of novel treatments, such as light therapies, is important. If light therapies prove effective, they could offset the cost of acne‐related treatments. If, however, light therapies are ineffective, their use should be stopped.

Hence, establishing the evidence to support treatment of acne with light of different wavelengths is critical. The plans for this review were published as a protocol 'Light therapies for acne' (Car 2009).

Objectives

To explore the effects of light treatment of different wavelengths for acne.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which were of two types: those which compared two groups of participants where one group was randomised to receive treatment and the other served as the control group; and those which applied treatment randomly to one part of a participant's body compared with another part which served as the control (such as split‐face studies).

We did not include cross‐over trials because an intervention for acne may have had a lasting effect that could have carried over to subsequent periods of the trial.

Types of participants

Anyone with a diagnosis of mild, moderate, or severe acne vulgaris defined by any classification system.

Types of interventions

We searched for any therapy based on the healing properties of light for the treatment of acne vulgaris. We also accepted therapies that combined light with other treatments to boost the effect of the light. We focused on a comparison between the effectiveness of treatment with light of different properties ‐ coherence, wavelength, and intensity.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Participant's global assessment of improvement. This was recorded using a Likert or Likert‐like scale (for instance, selecting from the following categories the extent of change of their acne after treatment: acne has worsened a lot; worsened a little; stayed the same; improved a little; or improved a lot) or other scales.

-

Investigator‐assessed change in lesion count.

-

The change or percentage change from baseline in the number of:

inflamed lesions (ILs) (papules or pustules or both);

non‐inflamed lesions (NILs) (blackheads or whiteheads or both); or

nodules and cysts (for nodulocystic acne only

-

If individual lesion counts were not available, then the change or percentage change from baseline in the number of:

ILs and NILs; or

combined count of all lesion types.

-

Investigator‐assessed severe adverse effects. If blistering or scarring of the skin followed treatment with light therapy then, if possible, we reported on the severity of the adverse effect and whether it resolved in the short‐term or was permanent.

Secondary outcomes

Investigator‐assessed change in acne severity. The change in acne severity from baseline, using a published grading scale (like the Leeds grading system, which involves counting lesions and weighting them according to severity to give a combined grade) or a severity index determined by the lesion count.

Investigator's global assessment of improvement recorded using a Likert or Likert‐like scale or other scales.

Changes in quality of life assessed using a recognised tool.

Other adverse outcomes

We recorded the incidence and, when possible, severity of all other adverse events reported in the included studies. We used the system organ classes (SOCs) defined in MedDRA (MedDRA 2010), version 15.1. MedDRA® ('the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, terminology is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). MedDRA® trademark is owned by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) on behalf of ICH').

Timing of outcome assessment

We considered short‐term (two to four weeks after final treatment), medium‐term (five to eight weeks after final treatment), and long‐term (longer than eight weeks after final treatment) follow‐up periods. The long‐term data were the primary endpoint, but we were also interested in short‐term data, indicating early improvement, which may have encouraged participants to continue with treatment.

Exclusion criteria

Studies which were not RCTs.

Studies not focused on the healing properties of light in the management of acne.

Studies on light therapies for acne scars.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 29 September 2015:

the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register using the following terms: acne and (laser* or sunlight or phototherap* or photolysis or photochemotherapy or “ ultraviolet therap*” or “photosensitizing agent*” or “light therap*” or “photodynamic therap*” or “photosensitising agent*”);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; the Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 8) using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 2;

Embase via Ovid (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 3; and

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 4.

We searched the following databases up to 28 September 2015:

ISI Web of Science using the strategy in Appendix 5; and

Dissertation Abstracts International (1861) using the strategy in Appendix 6.

Trials registers

We searched the following trials registers up to 28 September 2015:

The metaRegister of Controlled trials (isrctn.com/) using the strategy in Appendix 7.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (clinicaltrials.gov) using the strategy in Appendix 8.

The Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (anzctr.org.au) using the strategy in Appendix 9.

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (who.int/ictrp/en/) using the strategy in Appendix 10.

The EU Clinical Trials Register (clinicaltrialsregister.eu/) using the strategy in Appendix 11.

This review fully incorporates the results of searches conducted up to September 2015. A search update conducted in July 2016 identified a further 15 reports of trials, which we have added to ‘Studies awaiting classification’ and will incorporate into the review at the next update. See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We attempted to find unpublished studies by searching the following grey literature:

Google Scholar using the strategy in Appendix 12 up to 7 October 2015; and

OpenGrey using the strategy in Appendix 13 up to 29 September 2015.

We also used Internet search engines such as Google.

We consulted trial authors of included and excluded trials published in the last 15 years and other experts in the field of optical therapies for acne, in order to identify further unpublished RCTs.

Reference lists

We checked the bibliographies of published studies and reviews for further references to relevant trials.

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of the target intervention. We recorded adverse effects reported in the included trials and discussed the implications of those adverse outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the protocol for this review (Car 2009). When this was not possible, we clearly stated and further clarified it in the Differences between protocol and review section.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JB and RA, PP or MC) screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the searches. If studies did not address the study of a light therapy for acne, we excluded them. If any of the review authors felt that a paper could have been relevant, we retrieved the full text, and each author independently checked that it met the pre‐defined selection criteria. We resolved differences of opinion by discussion with the review team.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JB and RA or MC) independently recorded data using a specially designed data extraction form. When data were available only in graph or figure format, two review authors (JB and RA or MC) extracted them independently. A third team member (JC or LG) resolved any differences of opinion. One author (JB) inserted the data into Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014). Two review authors (MC and LG, RA or PP) cross‐checked the data for accuracy.

We defined treatment success as anything above the first category of improvement on a Likert scale or more than 50% improvement from baseline on a continuous scale for participant's global assessment of improvement (primary outcome 1) and secondary outcomes 1, 2, and 3. When individual patient data were not available, we extracted summary data as they were reported. Effects of interventions on investigator‐assessed change in lesion count (primary outcome 2) were recorded as the actual or percentage change from baseline.

In addition we reported on the following:

the baseline and comparisons of the participants for age, sex, duration, location, and severity of acne;

light source identity, dose, duration of treatment, and adequacy of instructions if self‐administered;

whether outcome measures were described and their assessment was standardised;

whether previous acne treatment was discontinued in a timely manner prior to the trial;

whether concomitant acne treatment was permitted and if so, whether standardised; and

the use and appropriateness of statistical analyses, where data were not reported appropriately in the original publication.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JB and RA or MC) used Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias, described in section 8.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), to independently assess the methodological quality of each included study. We assessed the following as 'low risk of bias', 'high risk of bias', or 'unclear risk of bias':

how the randomisation sequence was generated;

whether allocation was adequately concealed;

whether participants, clinicians, or outcome assessors were blinded as appropriate, who was blinded and not blinded (participants, clinicians, outcome assessors) if this was appropriate;

incomplete outcome data and how it was addressed;

possible selective outcome reporting; and

possible other bias.

We compared the assessments and discussed and resolved any disagreements in the gradings between the review authors. We also contacted the corresponding researchers for clarification or additional data when necessary.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed the results as risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes. When the relative risk was unreliable due to the lack of events occurring in control groups or body sites, we provided event rates instead of RR and calculated risk differences (RD) with 95% CI. We clarified this in the Effects of interventions section, under 'Primary outcome 3'. Although there were no cases where standardised mean differences were needed, we would have computed them if cases existed where comparable measures on different scales had been used across trials. We used only mean differences where appropriate (Deeks 2011). We expressed the results as 'number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome' (NNTB) and 'number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome' (NNTH) for dichotomous outcomes where appropriate, following guidance in section 12.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011a).

Unit of analysis issues

Where there were multiple intervention groups within a trial, we made pair‐wise comparisons of light therapies with different wavelengths versus no treatment, placebo, and conventional treatment. When the level of clinical and methodological heterogeneity was acceptable, we considered pooling studies that had a split‐face or split‐back design with studies that had a parallel‐group design in a meta‐analysis using the inverse variance method, described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions section 9.4.3 (Deeks 2011). However, we did not pool studies with different designs due to the nature of the results, as there was considerable methodological and clinical heterogeneity, which is outlined in the Effects of interventions section.

Dealing with missing data

If participant drop‐out led to missing data, we conducted an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We contacted trial authors or sponsors of studies that were less than 15 years old to provide missing statistics, such as standard deviations. For dichotomous outcomes, we regarded participants with missing outcome data as treatment failures (to be conservative) and included these in the analysis as an imputed value. For continuous outcomes, we imputed missing outcomes by carrying forward the last recorded value for participants with missing outcome data (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We followed updated guidance in sections 9.4.1 and 9.5.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011) on the appropriateness of meta‐analysis. To determine whether it would be clinically meaningful to quantitatively combine results of different studies, we considered differences in interventions (wavelengths, doses, active substances used in PDT, number of light sessions, and frequency of application) together with differences in comparator interventions (no treatment, placebo, other light interventions, and various topical treatments and their various combinations). For comparisons where no substantial clinical diversity existed with regard to the above, we assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003) and synthesised data using meta‐analysis techniques when appropriate (i.e. when I² statistic was lower than 50%) following guidance in section 9.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to test publication bias by the use of a funnel plot when adequate data were available for similar light therapies, following guidance in section 10.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). However, we were unable to implement this method in the current review and test publication bias by the use of a funnel plot due to the nature of our results.

Data synthesis

For studies with acceptable levels of clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we performed a meta‐analysis to calculate a weighted treatment effect across trials, using a random‐effects model. Where it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis due to substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we narratively synthesised the results, following guidance in section 11.7.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011b).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If substantial statistical heterogeneity (I² statistic greater than 50%) existed between studies for the primary outcome, we looked for the reasons for this, such as differences in disease severity, exposure, and duration of treatment. We planned to undertake further subgroup analysis if sufficient information was given. The groups were to include those with different severity or onset of acne and the age of participants (child or adult). However, subgroup analyses were not performed in the current review due to the nature of the results of the meta‐analyses (the I² statistic was lower than 50% for primary outcomes).

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to undertake sensitivity analyses to determine the effects of excluding the poorer quality trials and those with an unclear or high risk of bias as defined in theCochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

Adverse outcomes

We described:

whether the methods used to record adverse events were appropriate; and

whether reporting of adverse outcomes was adequate.

Other

Where necessary, we contacted the trial authors for clarification.

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro Guideline Developement Tool (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Results

Description of studies

Please see the Characteristics of included studies tables, Characteristics of excluded studies tables, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables in this review.

Results of the search

The 'Study flow diagram' summarises the results of our incorporated searches up to September 2015 (see Figure 1). We identified 862 records through searching the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and LILACS. We identified a further 907 records through searching ISI Web of Science and Dissertation Abstracts International. We identified 51 records through other searches. (Please see 'Clinical trials registers and 'Grey literature searches' section below for details.)

1.

Study flow diagram.

Our searches retrieved a total of 1820 records. We removed 1018 duplicates leaving 802 records. We excluded 648 records based on the titles and abstracts. We obtained full text copies of the remaining 154 records when appropriate. After assessing full texts, we excluded 25 records (corresponding to 24 studies) for reasons outlined in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

We included a total of 98 records in a narrative synthesis (corresponding to 71 studies). We were unable to obtain enough information to include or exclude 28 records (corresponding to 23 studies), which we listed in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables. A further three studies are ongoing (EU 2014‐005235‐13; NCT02217228; NCT02431494).

We included three studies in a quantitative meta‐analysis (NCT00594425; NCT00933543; Pariser 2013).

We only included final results of the clinical trials registers and grey literature searches in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) chart for reasons of clarity (Figure 1; Moher 2009).

Our final searches in July 2016 identified 13 additional studies (14 references): Demina 2015; Du 2015; Elgendy 2015; Ganceviciene 2015; Kwon 2016; Lekakh 2015; Moftah 2016; NCT02647528; Nestor 2016; Park 2015; Sadick 2016; Voravutinon 2016; Wang 2016. We have added a further report as a secondary reference to a previously identified study (Pariser 2013). We will incorporate the additional studies into the next update of this review.

Clinical trials registers and grey literature searches

Clinical trials registers and Open Grey returned a total of 377 records. Of these, 33 identifiers were relevant for the review. We matched 12 identifiers to 11 included studies identified through searches of other databases (Bissonnette 2010; Darne 2011; Haedersdal 2008; Hörfelt 2006; Karsai 2010; McGill 2008; Orringer 2007; Orringer 2010; Pariser 2013 (two identifiers); Uebelhoer 2007; Wiegell 2006b), while one identifier was matched to two separate studies, one included (Paithankar 2015) and one excluded (Owczarek 2014). We matched two identifiers to one study awaiting classification (Shaheen 2011). We were unable to match 18 identifiers with any of the studies identified through searches of other databases. They corresponded to 17 studies, as one study (NCT00237978) was registered in two different registers. We excluded one of these studies after contacting the study authors for clarification (NCT00613444). We obtained full results for three studies (NCT00594425; NCT00673933; NCT00933543) and results of one study were available in the register (NCT00706433), so we included them in our analysis. Nine are among studies awaiting classification (NCT00237978 (two identifiers); NCT00814918;NCT01245946; NCT01472900; NCT01584674; NCT01689935; ISRCTN73616060; ISRCTN78675673; ISRCTN95939628). Three studies are ongoing (EU 2014‐005235‐13; NCT02217228; NCT02431494).

A search of Google Scholar retrieved 963 records, and after screening, we found nine records of potentially relevant studies not identified through searches of the other databases.

We identified nine additional records through other sources (including authors' suggestions, reference lists of papers, and a Google search).

We have described our attempts to contact the authors of individual studies in the 'Notes' sections of the Characteristics of included studies tables, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables, Characteristics of ongoing studies tables, or Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Included studies

We included 71 studies, with a total of 4211 included participants, of which 40 were studies of light therapies, excluding comparisons with photodynamic therapy (PDT) and randomised a total of 2485 participants, and 31 were studies of PDT (including comparisons with light therapies) which included a total of 1726 participants. Please see the Characteristics of included studies tables for details.

Design

All included studies were RCTs. Most had a parallel‐group design (40 studies), or a split‐face design (28 studies), two had a split‐back design (NCT00673933; Pollock 2004), and one had a split‐face and split‐back design (Barolet 2010).

Eleven of the 40 studies above had a parallel‐group design, but within each group, a different intervention was administered to each side of the face or other body part; six studies with such a design randomised both groups and face sides (Bissonnette 2010; Oh 2009; Orringer 2004; Seaton 2003; Yeung 2007; Yilmaz 2011); two studies randomised groups, but not face sides (Liu 2014; Yin 2010); three other studies randomised participants to groups, but it was unclear whether within those groups, treatments were also randomly applied to one part of a participant's body compared with another part that served as control (Genina 2004; Hongcharu 2000; Sami 2008).

Most studies reported, or study authors later provided information that ethical approval was obtained, but this was unclear in 22 studies (Baugh 2005; Bernstein 2007; Bowes 2003; Cheng 2008; Elman 2003; Fadel 2009; Genina 2004; Gold 2011; Hongcharu 2000; Jih 2006; Kim 2009; Ling 2010; Liu 2014; NCT00706433; Ou 2014; Papageorgieu 2000; Sadick 2010a; Taub 2007; Tzung 2004; Zhang 2009a; Zhang 2013a; Zhang 2013b).

The majority of studies reported, or later provided information regarding sponsorship and conflict of interest, but this remained unclear for 20 studies (Bernstein 2007; Borhan 2014; Bowes 2003; Chen 2015; Cheng 2008; de Arruda 2009; Elman 2003; Hong 2013; Ling 2010; Liu 2011; McGill 2008; Na 2011; Ou 2014; Papageorgieu 2000; Pollock 2004; Sami 2008; Tzung 2004; Zhang 2009a; Zhang 2013a; Zhang 2013b). The authors of 20 studies declared no conflict of interest and no commercial sponsors (Anyachukwu 2014; Chang 2007; Choi 2010; Fadel 2009; Ianosi 2013; Jung 2009; Jung 2012; Karsai 2010; Kim 2009; Lee 2010; Leheta 2009; Liu 2014; Mei 2013; Na 2007; Oh 2009; Song 2014; Wiegell 2006a; Wiegell 2006b; Yilmaz 2011; Yin 2010). In 25 studies, the authors declared some sort of conflict of interest or were industry sponsored (Ash 2015; Barolet 2010; Baugh 2005; Bissonnette 2010; Darne 2011; Genina 2004; Gold 2005; Gold 2011; Haedersdal 2008; Hongcharu 2000; Hörfelt 2006; Jih 2006; NCT00594425; NCT00673933; NCT00706433; NCT00933543; Orringer 2004; Orringer 2007; Paithankar 2015; Pariser 2013; Seaton 2003; Taub 2007; Uebelhoer 2007; Wang 2006; Yeung 2007). In five studies, the authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest, but it was unclear who provided the device or the sham device (Kwon 2013) or whether there was commercial sponsorship (Moneib 2014; Ragab 2014; Sadick 2010a; Sadick 2010b). One study had non‐commercial sponsors but it was unclear whether the authors had some sort of conflict of interest (Orringer 2010).

Only 18 studies clearly performed power calculations (Ash 2015; Barolet 2010; Bissonnette 2010; Darne 2011; Gold 2005; Hörfelt 2006; Karsai 2010; Ling 2010; NCT00594425; NCT00933543; Orringer 2004; Orringer 2007; Orringer 2010; Pariser 2013; Sadick 2010b; Seaton 2003; Wiegell 2006b; Yeung 2007).

Sample sizes

Individual sample sizes varied from 7 to 738, with an average sample size of 59 participants and median size of 31 participants. Studies of light‐only therapies, excluding comparisons with PDT, had an average sample size of 62 and median size of 36.5 participants. Studies of PDT (including comparisons with light therapies) had an average sample size of 56 and median size of 25 participants.

Twelve studies randomised more than 100 participants (Ianosi 2013; Ling 2010; Liu 2014; NCT00594425; NCT00706433; NCT00933543; Papageorgieu 2000; Pariser 2013; Yin 2010; Zhang 2009a; Zhang 2013a, Zhang 2013b); five studies randomised 60 to 90 participants (Cheng 2008; de Arruda 2009; Karsai 2010; Ou 2014; Sadick 2010b).

Setting

Most studies were performed in a single centre or it was unclear whether they were single or multicenter. Only 13 studies were clearly multicenter (Gold 2005; Hörfelt 2006; Kwon 2013; Ling 2010; NCT00594425; NCT00673933; NCT00706433; NCT00933543; Paithankar 2015; Pariser 2013; Sadick 2010b; Tzung 2004; Uebelhoer 2007).

Twenty‐seven studies were performed in Asia, 21 in North America, 14 in Europe, seven in Africa, and one in South America (de Arruda 2009). No studies were conducted in Australia. One multicenter study, Sadick 2010b, was conducted in North America and Asia.

Study authors reported several means of recruitment. The most common way was through outpatient clinics and dermatology departments ‐ reported in 33 studies. Around one third of studies (23) did not describe recruitment methods.

Participants

The lowest age as an inclusion criterion was nine years. The age of included participants ranged from 11 to 59 years. In 46 studies, the mean age of included participants was between 20 and 30 years, and 38 of these studies also reported age ranges of included participants (means of age ranges were 17 to 37 years, medians of age ranges 18 to 37.5 years). Seven studies had a mean age lower than 20 (de Arruda 2009; Elman 2003; Hörfelt 2006; Karsai 2010; NCT00933543; Pariser 2013; Ragab 2014) and three, higher than 30 (Gold 2005; McGill 2008; Wang 2006).

Two studies reported no data on age (Bowes 2003; Na 2011), three reported only the inclusion criterion (Ash 2015; Fadel 2009; Wiegell 2006a), one study reported on median age and inclusion criterion only (Ianosi 2013), six reported only the age range (Genina 2004; Hong 2013; Kwon 2013; Pollock 2004; Seaton 2003; Zhang 2013a), and two reported the age range and inclusion criterion (Haedersdal 2008; Leheta 2009).

Most studies enrolled both male and female participants. One study was female only (Chang 2007), and one was male only (Anyachukwu 2014). Sex of participants was unclear in 10 studies (Bowes 2003; Fadel 2009; Jung 2009; Jung 2012; Leheta 2009; Na 2011; Taub 2007; Tzung 2004; Wiegell 2006a; Wiegell 2006b).

All studies included participants with clinically evident acne. Most studies included participants with mild to moderate acne (27 studies) or moderate to severe acne (18 studies). Four studies did not report severity of acne assessment when including the participants (Bernstein 2007; Jung 2012; Na 2011; Orringer 2010).

Most studies defined severity by various grading scores (34 studies). Twelve studies defined severity using lesion counts (Gold 2005; Haedersdal 2008; Ianosi 2013; Jih 2006; NCT00673933; Papageorgieu 2000; Sadick 2010b; Uebelhoer 2007; Wiegell 2006a; Wiegell 2006b; Yeung 2007; Yilmaz 2011), and eleven studies used both grading scores and lesion counts (Barolet 2010; Bissonnette 2010; Darne 2011; Hörfelt 2006; NCT00594425; NCT00706433; NCT00933543; Paithankar 2015; Pariser 2013; Seaton 2003; Taub 2007). It was unclear how ten studies performed severity assessment when including participants (Baugh 2005; Bowes 2003; Elman 2003; Fadel 2009; Genina 2004; Kim 2009; Leheta 2009; Na 2007; Tzung 2004; Wang 2006).

Studies included participants with different skin responses to sun exposure, that is, different phototypes. According to the commonly used Fitzpatrick's classification, phototypes range from type I (pale white skin which always burns and never tans) to type VI (deeply pigmented dark brown to black skin which never burns and tans very easily) (Fitzpatrick 1988). Ten studies included participants with Fitzpatrick Skin Types (FPTs) I to III (Barolet 2010; Baugh 2005; Bernstein 2007; Haedersdal 2008; Hörfelt 2006; Karsai 2010; McGill 2008; Paithankar 2015; Sadick 2010a; Yilmaz 2011), and five studies, FPT I to IV (Bissonnette 2010; Gold 2011; Hongcharu 2000; Ianosi 2013; NCT00594425). Eight studies included FPT III to IV (Borhan 2014; Chang 2007; Liu 2011; Oh 2009; Sami 2008; Song 2014; Tzung 2004; Yin 2010), and four studies included participants with FPTs III to V ( Choi 2010; Jung 2012; Kwon 2013; Ragab 2014). Three studies included FPT II‐IV (Mei 2013; Taub 2007; Wang 2006), two included FPT V to VI (Anyachukwu 2014; NCT00673933), two included FPT IV to V (Hong 2013; Yeung 2007), one included only FPT III (Lee 2010) and 12 studies included participants with 4 or more different FPTs from I to VI (Ash 2015; Darne 2011; Jih 2006; NCT00706433; NCT00933543; Orringer 2007; Orringer 2010; Pariser 2013; Pollock 2004; Sadick 2010b; Wiegell 2006b). Twenty‐four studies did not report FPTs.

Interventions

We observed a substantial heterogeneity in interventions. To present them in a clearer way, we first separated studies of light‐only therapies (excluding comparisons with PDT and studies of PDT (including comparisons with light‐only therapies)). We then made subgroups according to comparison interventions (such as placebo or no treatment, topical treatments, and other comparisons) and wavelengths used in light interventions. To describe light of different wavelengths, we used corresponding colours ('green light' for wavelengths 495 to 570 nm, 'yellow light' for wavelengths 570 to 590 nm etc.). We additionally grouped PDT studies according to active substances used: methyl aminolevulinate (MAL), aminolevulinic acid (ALA), MAL versus ALA, and other active substances.

Below we have listed light‐only studies from 1 to 3 and PDT studies from 4 to 7, as well as their subgroups. If a study had more than one comparison, we listed it for every comparison it included.

1. Light versus placebo or no treatment

a) Green light versus placebo: three studies (Baugh 2005; Bowes 2003; Yilmaz 2011) b) Yellow light versus placebo or no treatment: two studies (Orringer 2004; Seaton 2003) c) Infrared light versus no treatment: three studies (Darne 2011; Moneib 2014; Orringer 2007) d) Blue light versus placebo or no treatment: three studies (Elman 2003; Gold 2011; Tzung 2004) e) Red light versus no treatment: one study (Na 2007) f) Blue‐red light versus placebo: two studies (Kwon 2013; Papageorgieu 2000) g) Broad spectrum light versus placebo: one study (Sadick 2010b) h) Intense pulsed light (IPL) versus no treatment: one study (McGill 2008)

2. Light versus topical treatment

a) Light versus benzoyl peroxide (BPO): three studies; one blue light (de Arruda 2009) and two blue‐red light (Chang 2007; Papageorgieu 2000) b) Light versus clindamycin: two studies (Gold 2005; Lee 2010) c) Light and other topical treatments: seven studies (Anyachukwu 2014; Ash 2015; Borhan 2014; Ianosi 2013; Karsai 2010; Leheta 2009; Zhang 2009a)

3. Light versus other comparators

a) Comparison of light therapies of different wavelengths: seven studies (Cheng 2008; Choi 2010; Jung 2009; Liu 2011; Liu 2014; Papageorgieu 2000; Sami 2008) b) Comparison of light therapies of different doses: four studies (Bernstein 2007; Jih 2006; NCT00706433; Uebelhoer 2007) c) Comparison of light therapies of different treatment application intervals: one study (Yilmaz 2011) d) Light alone versus combined with microdermoabrasion: one study (Wang 2006) e) Light in combination with carbon lotion (topical carbon suspension) versus no treatment: one study (Jung 2012) f) Light in combination with oral therapy versus other comparators: four studies (Ling 2010; Ou 2014; Zhang 2009a; Zhang 2013b) g) Intense pulsed light (IPL) alone versus IPL in combination with vacuum: one study (Ianosi 2013)

4. MAL‐PDT versus other comparators

a) MAL‐PDT versus red light alone: five studies (Hörfelt 2006; NCT00594425; NCT00673933; NCT00933543; Pariser 2013) b) MAL‐PDT versus yellow light alone: one study (Haedersdal 2008) c) MAL‐PDT versus placebo or no treatment: one study (Wiegell 2006b) d) MAL‐PDT other: four studies (Bissonnette 2010; Hong 2013; NCT00594425; Yeung 2007)

5. ALA‐PDT versus other comparators

a) ALA‐PDT versus red light alone: three studies (Chen 2015; Pollock 2004; Zhang 2013a) b) ALA‐PDT versus blue light alone: one study (NCT00706433) c) ALA‐PDT versus blue‐red light alone: one study (Liu 2014) d) ALA‐PDT versus IPL alone: four studies (Liu 2014; Mei 2013; Oh 2009; Ragab 2014). (Please note that different filters were used.) e) ALA‐PDT versus green light alone: one study (Sadick 2010a) f) ALA‐PDT versus placebo or no treatment: two studies (Orringer 2010; Pollock 2004) g) ALA‐PDT other: six studies (Barolet 2010; Hongcharu 2000; NCT00706433; Pollock 2004; Taub 2007; Yin 2010)

6. MAL‐PDT versus ALA‐PDT

a) One study compared these interventions (Wiegell 2006a)

7. Other (non‐MAL, non‐ALA) PDT versus other comparators

a) Indocyanine green (ICG) PDT: two studies (Genina 2004; Kim 2009) b) Indole‐3‐acetic acid (IAA) PDT: one study (Na 2011) c) Topical liposomal methylene blue (TLMB) PDT: one study (Fadel 2009) d) Chlorophyll‐a (CHA) PDT: one study (Song 2014) e) Gold microparticles PDT: one study (Paithankar 2015)

Seven studies had a single light treatment session in one of the interventions (Barolet 2010; Genina 2004; Hongcharu 2000; Kim 2009; Orringer 2004; Seaton 2003; Wiegell 2006a).

Most interventions had two to four sessions, two studies had five sessions (Ianosi 2013; McGill 2008), two studies had six sessions (Leheta 2009; Ou 2014), 12 studies had eight sessions (Anyachukwu 2014; de Arruda 2009; Elman 2003; Genina 2004; Gold 2005; Lee 2010; Ling 2010; Liu 2011; Song 2014; Tzung 2004, Zhang 2009a; Zhang 2013b), one study had up to 24 sessions (Cheng 2008), one study had 28 sessions (Ash 2015) and one study had 84 sessions (Papageorgieu 2000). Two self‐administered interventions had a total of 56 (Kwon 2013) and 112 sessions (Na 2007).