Abstract

Background

Admission avoidance hospital at home provides active treatment by healthcare professionals in the patient's home for a condition that otherwise would require acute hospital inpatient care, and always for a limited time period. This is the third update of the original review.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and cost of managing patients with admission avoidance hospital at home compared with inpatient hospital care.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, two other databases, and two trials registers on 2 March 2016. We checked the reference lists of eligible articles. We sought unpublished studies by contacting providers and researchers who were known to be involved in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials recruiting participants aged 18 years and over. Studies comparing admission avoidance hospital at home with acute hospital inpatient care.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane and the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group. We performed meta‐analysis for trials that compared similar interventions and reported comparable outcomes with sufficient data, requested individual patient data from trialists, and relied on published data when this was not available. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for the most important outcomes.

Main results

We included 16 randomised controlled trials with a total of 1814 participants; three trials recruited participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, two trials recruited participants recovering from a stroke, six trials recruited participants with an acute medical condition who were mainly elderly, and the remaining trials recruited participants with a mix of conditions. We assessed the majority of the included studies as at low risk of selection, detection, and attrition bias, and unclear for selective reporting and performance bias. Admission avoidance hospital at home probably makes little or no difference on mortality at six months' follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60 to 0.99; P = 0.04; I2 = 0%; 912 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), little or no difference on the likelihood of being transferred (or readmitted) to hospital (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23; P = 0.84; I2 = 28%; 834 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and may reduce the likelihood of living in residential care at six months' follow‐up (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.57; P < 0.0001; I2 = 78%; 727 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Satisfaction with healthcare received may be improved with admission avoidance hospital at home (646 participants, low‐certainty evidence); few studies reported the effect on caregivers. When the costs of informal care were excluded, admission avoidance hospital at home may be less expensive than admission to an acute hospital ward (287 participants, low‐certainty evidence); there was variation in the reduction of hospital length of stay, estimates ranged from a mean difference of ‐8.09 days (95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐1.85) in a trial recruiting older people with varied health problems, to a mean increase of 15.90 days (95% CI 8.10 to 23.70) in a study that recruited patients recovering from a stroke.

Authors' conclusions

Admission avoidance hospital at home, with the option of transfer to hospital, may provide an effective alternative to inpatient care for a select group of elderly patients requiring hospital admission. However, the evidence is limited by the small randomised controlled trials included in the review, which adds a degree of imprecision to the results for the main outcomes.

Plain language summary

'Hospital at home' services to avoid admission to hospital

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane review was to find out if providing healthcare in an admission avoidance hospital at home setting improves patient health outcomes and reduces cost to the health service.

Key messages

Admission avoidance hospital at home probably makes little or no difference to patient health outcomes, may increase the chances of living at home at six months' follow‐up, and may be slightly less expensive. However, the findings are not precise due to the small size of the studies included in the review.

What was studied in this review?

There continues to be more demand for acute hospital beds than there are beds. One way to reduce reliance on hospital beds is to provide people with acute health care at home, sometimes called 'hospital at home'. We systematically reviewed the literature on the effect of providing hospital at home services to avoid hospital admission for adults.

What are the main results of this review?

Admission avoidance hospital at home, with the option of transfer to hospital, may provide an effective alternative to inpatient care for a select group of elderly patients requiring hospital admission. We found 16 studies, of which six were identified for this update. Three studies recruited participants with chronic obstructive (lung) disease, two recruited participants recovering from a stroke, six recruited participants with a (sudden or short‐term) medical condition who were mainly elderly, and the remaining studies recruited participants with a mix of conditions. The studies showed that when compared to in‐hospital care, admission avoidance hospital at home services probably make little or no difference to patient health outcomes or to the likelihood of being taken to hospital, and may increase the chances of living at home at six months' follow‐up. Patients who receive care at home may be more satisfied than those who are in hospital, but it is not known how this type of health care affects the caregivers who support them. With respect to costs, it is uncertain if hospital at home services reduce or increase length of stay or cost to the health service; when the costs for caregivers are taken into account any difference in cost may disappear.

How up to date is the review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to March 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Admission avoidance hospital at home compared with inpatient admission for older people requiring admission to hospital.

| Admission avoidance hospital at home compared with inpatient admission for older people requiring admission to hospital | |||||

|

Patient or population: Older people requiring hospital admission Settings: Home Intervention: Admission avoidance hospital at home Comparison: Inpatient care | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Inpatient admission | Admission avoidance hospital at home | ||||

|

Transfer (or readmission) to hospital for patients with a medical condition using individual patient data and published data (3 to 12 months' follow‐up) |

Study population |

RR 0.98 (0.77 to 1.23) |

834 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕o1 Moderate | |

| 254 per 1000 | 249 per 1000 (195 to 312) | ||||

| Medium‐risk population | |||||

| 340 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (262 to 418) | ||||

|

Mortality at 6 months' follow‐up (using data from trialists and published data) |

Study population |

RR 0.77 (0.60 to 0.99) |

912 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕o1 Moderate | |

| 240 per 1000 | 185 per 1000 (144 to 237) | ||||

| Medium‐risk population | |||||

| 196 per 1000 | 151 per 1000 (118 to 194) | ||||

|

Living in an institutional setting at 6 months' follow‐up |

Study population |

RR 0.35 (0.22 to 0.57) |

727 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕oo2 Low |

|

| 161 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (35 to 92) | ||||

| Medium‐risk population | |||||

| 151 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (33 to 86) | ||||

| Patient satisfaction | Patients allocated to hospital at home care reported higher levels of satisfaction, range 8% to 40% | ‐ | 646 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊕oo3 Low | |

| Hospital and hospital at home length of stay | Length of stay ranged from a mean reduction of ‐8.09 days (95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐1.85) to a mean increase of 15.90 days (95% CI 8.10 to 23.70) | ‐ | 714 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊕oo2 Low |

|

| Cost | Estimates (boot strapped mean difference) of health service cost varied, from a lower cost at 3 months' follow‐up for hospital at home of GBP 210.90 (95% CI GBP ‐1025 to GBP 635.47), to a mean difference (lower cost for hospital at home) per episode of immediate care of GBP ‐304.72, 95% CI GBP ‐1112.35 to GBP 447.89 | ‐ | 287 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕oo4 Low | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1We downgraded the certainty of the evidence due to lack of precision. 2We downgraded the certainty of the evidence due to lack of precision and inconsistency. 3We downgraded the certainty of the evidence, as only 31% of studies reported this outcome, and there is risk of detection bias due to subjective reporting of this outcome. 4We downgraded the certainty of the evidence, as only two studies reported a full cost analysis.

Background

For several decades there has been an emphasis by health systems around the world on avoiding admission to hospital, and in the last 10 years this has gained some momentum, reflecting the changing demographic and also the relatively limited gain from discharging patients early after a stay in hospital, given the universal trend for shorter hospital lengths of stay. Cutting costs by avoiding admission to hospital in the first instance is the central goal of such schemes. Other perceived benefits include reducing the risk of adverse events associated with time in hospital and the potential benefit of receiving rehabilitation within the home environment (Brennan 2004). The type of patient treated in hospital at home services varies between schemes, as does the use of technology. Some schemes are designed to care for specific conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or provide specific skills, such as parenteral nutrition (Mughal 1986). These schemes usually have close ties with acute hospitals and may be encouraged by the different structure of incentives in insurance‐based systems of health care. However, many other hospital at home schemes lack such a clear function and have an 'open‐door' policy covering a large range of conditions.

Description of the condition

The demographic shift of a rising number of older people, combined with the relative reduction in the number of working‐age adults contributing to the economy, make the provision of sustainable safe health care for older adults a major health concern for the 21st century. For example, in the UK nearly two‐thirds (65%) of people admitted to hospital are over 65 years old, and over the last 10 years there has been a 65% increase in the number of people aged over 75 who have required secondary care (Cornwall 2012). Healthcare decision‐makers in a number of countries are attempting to reconfigure services to deal with the year‐on‐year increase in hospital admissions, often with an inadequate evidence base (Nolte 2008). These changes have raised concerns that the pressure of delivering health care to greater numbers may be at odds with the provision of person‐centred, high‐quality care (Royal College of Physicians 2012).

Description of the intervention

Admission avoidance hospital at home provides co‐ordinated, multidisciplinary care in the home for people who would otherwise be admitted to hospital. People are admitted to admission avoidance hospital at home after assessment in the community by their primary care physician, in the emergency department or a medical admissions unit. Hospital at home may also provide hospital‐level care following early discharge from hospital (we have conducted a parallel systematic review of early discharge hospital at home, Shepperd 2009).

How the intervention might work

One aim of admission avoidance hospital at home is to reduce the demand for acute hospitals beds; a second aim is to lower the risk of functional decline from limited mobility that can occur during an admission to hospital, particularly in frail older people, by providing co‐ordinated health care in a less restrictive environment and thereby giving patients the opportunity for continued involvement in activities of daily living (Covinsky 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite a policy emphasis on care closer to home (Monitor 2015), it is not known if people admitted to admission avoidance hospital at home have better or equivalent health outcomes compared with those receiving inpatient hospital care. It is also unknown whether the provision of hospital at home results in a reduction or increase in health service costs.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and cost of managing patients with admission avoidance hospital at home compared with inpatient hospital care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

This review included evaluations of admission avoidance hospital at home schemes involving people aged 18 years and over. We did not include people with long‐term care needs unless they required admission to hospital for an acute episode of care. We excluded evaluations of obstetric, paediatric, and mental health hospital at home schemes from the review since our preliminary literature searches suggested that separate reviews would be justified for each of these groups. For the purpose of this review, we defined older patients as those aged 65 years and older.

Types of interventions

Studies comparing admission avoidance hospital at home with acute hospital inpatient care. The admission avoidance hospital at home studies may admit patients directly from the community thereby avoiding physical contact with the hospital, or may admit from the emergency room. We used the following definition to determine if studies should be included in the review: hospital at home is a service that can avoid the need for hospital admission by providing active treatment by healthcare professionals in the patient's home for a condition that otherwise would require acute hospital inpatient care, and always for a limited time period. In particular, hospital at home has to offer a specific service to patients in their home requiring healthcare professionals to take an active part in the patients' care. If hospital at home were not available, then the patient would be admitted to an acute hospital ward. We have therefore excluded the following services from this review:

services providing long‐term care;

services provided in outpatient settings or postdischarge from hospital; and

self care by the patient in their home such as self administration of an intravenous infusion.

Types of outcome measures

Main outcomes

Mortality

Transfer (or readmission) to hospital

Other outcomes

Functional status

Quality of life or self reported health status

Cognitive function

Depression

Clinical outcomes

Place of residence at follow‐up (living in a residential setting)

Patient satisfaction

Caregiver outcomes

Health professionals' views

Length of stay in hospital and hospital at home

Cost

Use of other health services and informal care

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 2 March 2016 for references published since the last version of this review.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 2 of 12, 2016), including the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register, Wiley (search date 2 March 2016).

MEDLINE (1946 to 2 March 2016), MEDLINE and MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, OvidSP.

EMBASE (1974 to 1 March 2016), OvidSP.

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (1980 to 2 March 2016), EBSCOhost.

EconLit (1886 to 2 March 2016), ProQuest.

There were no restrictions to publication status or language of publication. See Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 for details of the search strategies used.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of articles identified electronically for evaluations of hospital at home and obtained potentially relevant articles. We conducted a citation search of all included studies in the previous version of this review using the Science Citation Index (search date 22 April 2015). We searched clinical trial registries using the terms 'hospital at home' and 'admission' for open, interventional trials that recruited adults and older adults (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the term 'hospital at home' (who.int/ictrp).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SS, DGB) read all the abstracts in the records retrieved by the electronic searches to identify potentially eligible publications. We retrieved full‐text papers for these publications, and two review authors (SS and SI, or SS and DGB) independently assessed their eligibility. We selected studies for the review according to the prespecified inclusion criteria and resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SS and SI, or SS and DGB) independently completed data extraction using a good‐practice extraction form developed by Cochrane that was modified and amended for the purposes of this review (EPOC 2015a).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SS and SI, or SS and DGB) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the suggested 'Risk of bias' criteria for EPOC reviews (EPOC 2015b):

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

baseline outcome measurement;

baseline characteristics;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting of outcomes.

Certainty of the evidence

We graded our confidence in the evidence by creating a 'Summary of findings' table using the approach recommended by the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group, in Guyatt 2008, and the specific guidance developed by EPOC (EPOC 2015c). We included the main outcomes of mortality and hospital readmission, as well as place of residence at follow‐up, patient satisfaction, and costs. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and risk of bias) to assess the certainty of the evidence as it relates to the main outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

We conducted an individual patient data (IPD) meta‐analysis in a subgroup of trials evaluating specific outcomes in the more homogeneous populations. We contacted the investigators of 10 of the included trials by email or telephone, inviting them to contribute data to the hospital at home admission avoidance collaborative review. We sent up to four reminders. We excluded five trials from the IPD meta‐analysis (n = 518 participants), though included these trials in the review, as they recruited participants who differed substantially from the populations in the other trials, in terms of having an acute short‐term condition (community‐acquired pneumonia, Richards 2005), having significant cognitive impairment (Tibaldi 2004), cellulitis (Corwin 2005), experiencing febrile neutropenia as a result of chemotherapy (Talcott 2011), and having neuromuscular disease and a respiratory infection (Vianello 2013). One small trial was published as a meeting abstract only; we tried to contact the authors for further information but did not receive a reply (Andrei 2011, n = 45).

For the IPD meta‐analysis, where at least one event was reported in both study groups in a trial, we used Cox regression models to calculate the log hazard ratio and its standard error for mortality for each data set. We included randomisation group (admission avoidance hospital at home versus control), age (above or below the median), and gender in the models. We combined the calculated log hazard ratios using fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis (Deeks 2001). The pooled effect is expressed as the hazard ratio for hospital at home compared with usual hospital care. If there were no events in one group, we used the Peto odds ratio method to calculate a log odds ratio from the sum of the log‐rank test 'O‐E' statistics from a Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis. This method does not require corrections for zero cell counts, and thus it performs well when events are rare (Deeks 1998). Throughout the analyses, we took statistical significance at the two‐sided 5% level (P < 0.05), presenting data as the estimated effect with 95% confidence intervals. For the original review, we used SPSS version 14.0 and Stata for all the analyses (SPSS 2006; Stata 2005), undertaking the meta‐analysis in Review Manager version 4.2. For this update, we conducted analysis using Review Manager version 5.3 (RevMan 2014).

Our statistical analyses sought to include all randomised participants, using intention‐to‐treat. We relied on published data when the IPD did not include the relevant outcomes. When combining outcome data was not possible because of differences in the reporting of outcomes, we presented the data from individual studies in summary tables. For each comparison using published data for dichotomous outcomes we calculated risk ratios using a fixed‐effect model to combine data. Comparison between health outcomes was restricted by the different measurement tools used in the included trials. Although planned, we did not attempt a direct comparison of costs because the trials collected data on different resources and used different methods to calculate costs.

Dealing with missing data

In two data sets contributing to the IPD meta‐analysis (Davies 2000; Kalra 2000), some dates were missing for known events, and so we gave the missing event a time at the midpoint between randomisation and last follow‐up, or as the midpoint between follow‐up times if these were known. For one trial where follow‐up was 90 days, we set the time to event as 45 days for three cases in the admission avoidance hospital at home arm and for one case in the control group where we knew death had occurred but we did not have a date (Davies 2000). For the other trial, we gave a time to event of 14 days if the participant was known to have died some time between randomisation and one‐month follow‐up, and at 59 days if they were known to have died between one and three months' follow‐up (Kalra 2000).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity by Cochran's Q and the I2 statistic (Cochran 1954), the latter quantifying the percentage of the total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003); smaller percentages suggest less observed heterogeneity.

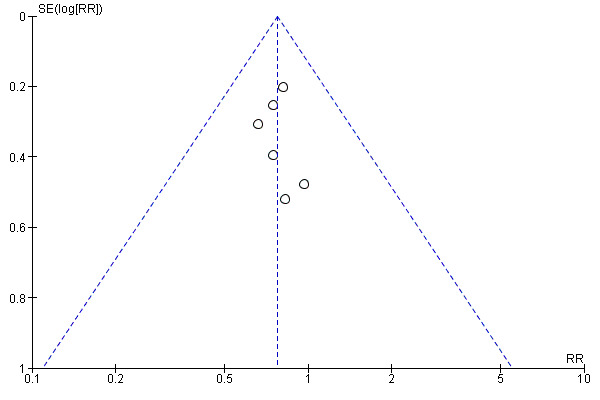

Assessment of reporting biases

We created one funnel plot, for mortality at six months' follow‐up, recognising that when the number of trials is small these plots are not necessarily indicative of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 16 trials that randomised individual participants (N = 1814), of which six were identified in this update. We invited 10 trialists to contribute data to the IPD meta‐analysis (Caplan 1999; Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Mendoza 2009; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2009; Wilson 1999), of which six contributed data (n = 921/1206; 76%) (Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Mendoza 2009; Ricauda 2004; Wilson 1999). We contacted the authors of a study published as a meeting abstract for further information, but did not receive a reply (Andrei 2011, n = 45). We did not contact five trialists as their studies included participants who were significantly different from the remaining populations, for example populations with short‐term acute conditions or advanced dementia (Corwin 2005; Richards 2005; Talcott 2011; Tibaldi 2004; Vianello 2013). We used published data when we did not have access to IPD. Follow‐up times varied across the different trials, ranging from 1 week to 12 months.

Results of the search

For this update the search retrieved 1364 records, of which 1350 were ineligible. We obtained full texts for the remaining 14 records, seven of which fulfilled the inclusion criteria (six trials, seven records), bringing the total number of trials included in the review to 16 (Figure 1). We also identified two ongoing trials (ISRCTN29082260; ISRCTN60477865).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study populations

Three trials recruited participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Davies 2000; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2008), two trials recruited participants recovering from a moderately severe stroke who were clinically stable (Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004), and six trials recruited participants with an acute medical condition who were mainly elderly (Andrei 2011; Caplan 1999; Harris 2005; Mendoza 2009; Tibaldi 2009; Wilson 1999). There was one trial each for participants with cellulitis (Corwin 2005), community‐acquired pneumonia (Richards 2005), fever and neutropenia (Talcott 2011), frail elderly participants with dementia (Tibaldi 2004), and neuromuscular disease (Vianello 2013). The 16 trials were conducted in seven countries: Australia (two trials), Italy (five trials), New Zealand (three trials), Romania (one trial), Spain (one trial), the UK (three trials), and the US (one trial).

Interventions

In 12 of the trials included in this review participants were admitted to hospital at home from the emergency room (Andrei 2011; Caplan 1999; Corwin 2005; Davies 2000; Mendoza 2009; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Richards 2005; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009; Vianello 2013), in three directly from the community following referral by their primary care physician (Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Wilson 1999), and in one from an outpatient department (Talcott 2011). For participants allocated to hospital at home, health care was provided by a hospital outreach team (Caplan 1999; Harris 2005; Mendoza 2009; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Talcott 2011; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009), a mix of outreach and community staff (Davies 2000; Kalra 2000; Nicholson 2001; Vianello 2013), or by the general practitioner (GP) and community nursing staff (Corwin 2005; Richards 2005; Wilson 1999). For one of the trials it was not clear who provided care (Andrei 2011). In two trials, the intervention was provided by Pegasus Health, an independent association of GPs (Corwin 2005; Richards 2005). One trial was a three‐group comparison of stroke unit care, inpatient stroke team, and hospital at home (Kalra 2000); we selected the inpatient stroke team as the comparison group, as this was most similar to the comparator in the other trials.

Physiotherapy care was described in seven of the interventions (Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2004; Wilson 1999), and occupational therapist care in four of the interventions (Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Nicholson 2001; Wilson 1999). A social worker was part of the hospital at home team in seven of the interventions (Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004; Talcott 2011; Tibaldi 2004; Wilson 1999), and a counsellor in one (Talcott 2011). Access to a speech therapist was described in three of the interventions (Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004; Wilson 1999). One trial described access to a cultural link worker (Wilson 1999). The intervention in one trial included the use of a portable ventilator; a respiratory therapist made daily visits for the first three days of home care, and district nurses and caregivers were trained in the application of the device and on assisting with coughing (Vianello 2013). District nurses visited daily until recovery from the respiratory tract infection; participants also had telephone access to pulmonary specialists (Vianello 2013).

Excluded studies

See the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We excluded three studies: one was a cross‐over randomised controlled trial (King 2000), one a non‐randomised comparison (Wade 1985), and in the third study the intervention did not substitute for inpatient care (Wolfe 2000).

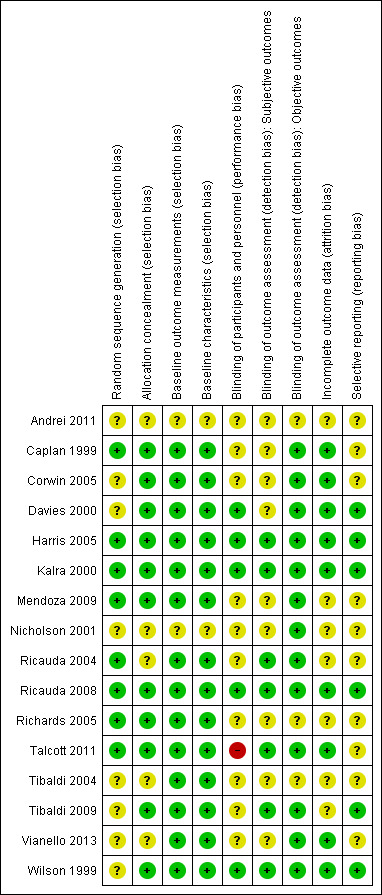

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

In 11 studies concealment of allocation was adequate (Caplan 1999; Corwin 2005; Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Mendoza 2009; Ricauda 2008; Richards 2005; Talcott 2011; Tibaldi 2009; Wilson 1999) (Figure 2; Figure 3), and in eight studies sequence generation was adequately described. (Caplan 1999; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Mendoza 2009; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Richards 2005; Talcott 2011)

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Blinding

All but one study used reliable measures of outcome (Vianello 2013), and four studies reported blinded assessment of outcome (Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2009). We assessed 13 studies as at low risk of bias for the measurement of objective outcomes, and seven at low risk of bias for the measurement of subjective outcomes (Figure 3).

Incomplete outcome data

Most of the studies had a low risk of attrition bias, with seven studies having an unclear risk (Andrei 2011; Mendoza 2009; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2004; Richards 2005; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009).

Selective reporting

Six studies were at low risk of bias for selective reporting (Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2009; Wilson 1999).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 for the main comparison admission avoidance hospital at home compared with inpatient admission for older people requiring admission to hospital.

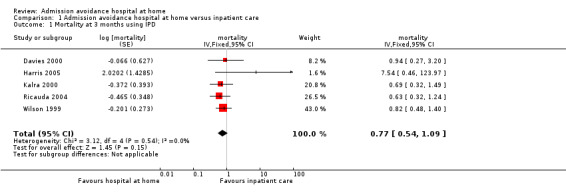

Mortality

We combined IPD, adjusted for age and sex, for mortality at three months' follow‐up for five studies (risk ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 1.09; P = 0.15; 833 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Davies 2000; Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004; Wilson 1999) (Analysis 1.1); and combined published data from three studies, Caplan 1999, Ricauda 2008, and Tibaldi 2009, with data received from trialists for three studies, Kalra 2000, Ricauda 2004, and Wilson 1999, for mortality at six months (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.99; P = 0.04; 912 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 1 Mortality at 3 months using IPD.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 2 Mortality at 6 months' follow‐up (using data from trialists, apart from Caplan).

4.

Funnel plot of admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, for mortality at 6 months' follow‐up (using data from trialists and published data from one study).

Transfer (or readmission) to hospital

We analysed the effect of admission avoidance hospital at home on hospital readmission or transfer at three months' follow‐up using data received from four trialists, Davies 2000, Harris 2005, Mendoza 2009, and Wilson 1999, and published data from three studies (Caplan 1999; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2009). Results indicated that admission avoidance hospital at home may make little to no difference for hospital readmission or transfer (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23; P = 0.84; 834 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 4 Readmission to hospital for patients with a medical condition at an average of 5 months' follow‐up.

Functional status

Nine trials reported measures of functional ability, for which higher scores indicate greater independence (see Analysis 1.5 for specific details on the scales used). Caplan 1999 reported scores for instrumental activities of daily living between admission and discharge (mean difference (MD) ‐0.23, P = 0.04), and the Barthel Index (hospital at home (T): 0.37 (0.27), hospital (C): ‐0.04 (0.27)). A trial that recruited participants with dementia reported that fewer participants in the hospital at home group had problems with sleep (difference 34%, P < 0.001), agitation and aggression (difference 32.5%, P < 0.001), and feeding (difference 31%, P < 0.001) (Tibaldi 2004). One trial recruiting participants who had a stroke reported the number of participants with a favourable outcome measured by the Barthel (score of 15 to 20) at three months (T: 106/145 (73%), C: 106/151 (70%), RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.11), P = 0.58) (Kalra 2000); and Ricauda 2004, which also recruited participants with a stroke, reported activities of daily living (scale 0 to 6) at six months (median (interquartile range (IQR)), T: 4 (2 to 5), C: 4 (2 to 6); P = 0.57). Two trials recruiting participants with COPD reported follow‐up data: Ricauda 2008 reported activities of daily living at six months: T: 0.12 (standard deviation (SD) 0.64), C: 0.08 (SD 0.73), P = 0.81, and Davies 2000 reported forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) at three months' follow‐up (T: 41.5%, 95% CI 8.2% to 74.8%; C: 41.9%, 95% CI 6.2% to 77.6%). Two studies recruiting participants with heart failure reported change in activities of daily living measured by the Barthel Index at six months' follow‐up (mean T: ‐1.95 (SD 9.61), C: ‐0.30 (SD 10.12) (Tibaldi 2009); and at one year (T: 4.0, 95% CI ‐0.9 to 8.9; C: 4.7, 95% CI ‐2.2 to 11.5; P = 0.21), adjusted for baseline differences (Mendoza 2009). Wilson 1999, which recruited older people with a mix of conditions, assessed functional ability at three months using the Barthel Index (median (IQR) T: 16 (13 to 19), C: 16 (12 to 20)) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 5 Functional status.

| Functional status | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Functional ability | Results |

| Admission avoidance patients with a medical condition ‐ functional ability | ||

| Caplan 1999 | Change in Barthel score from admission to discharge (high score=greater independence) Instrumental activities of daily living score from admission to discharge (higher score=greater independence) | Mean (SEM) T= 0.37 (0.27), C= ‐0.04 (0.27), NS Mean (SEM) T= 0.65 (0.23), C= ‐0.88 (0.26), P = 0.037 |

| Davies 2000 | St Georges' respiratory questionnaire (to a random sub‐group of 90 participants). High score indicates poorer health related quality of life. A minimum change in score of 4 units is clinically relevant. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) |

Baseline scores

T= 71.5 (43.4 to 99.6), C= 71.0 (43.4 to 98.6)

Mean (SD) change at 3 months

T= 0.48 (16.92) C= 3.13 (14.02) Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) At 3 months: T= 41.5% (95% CI 8.2% to 74.8%) C= 41.9% (95% CI 6.2% to 77.6%) |

| Kalra 2000 | Modified Rankin scale 0‐3 (measure of dependence: 0=independent and 3=dependent). Number independent and require minor assistance for day to day activities. Barthel 0‐20 (higher score=greater independence) |

Modified Rankin At 3 months T= 107/145 (74%) C= 111/151 (74%) RR 1.00 (0.86, 1.15), P = 0.96 At 12 months T= 102/144 (71%) C= 99/149 (66%) RR 0.94 (0.81, 1.09), P = 0.42 Barthel 15‐20 (number with favourable outcome) At 3 months T= 106/145 (73%) C= 106/151 (70%) RR 0.96 (0.83, 1.11), P = 0.58 At 12 months T= 102/144 (71%) C= 102/149 (69%) RR 0.97 (0.85, 1.11), P = 0.65 |

| Mendoza 2009 | Activities of daily living |

Mean score Barthel Index at 1 year (adjusted for baseline differences) T= 4.0 (‐0.9 to 8.9) C= 4.7 (‐2.2 to 11.5) P = 0.21 |

| Ricauda 2004 | Activities of daily living (number of functions lost, score 0 to 6).

Functional impairment measure (level of independence, range 28 to 126. High score =greater independence Canadian Neurological Scale Score (higher score=improvement, range 0‐10) National Institute of Health Stroke Scale Score (low score =improvement; range 0‐36) |

Activities of daily living At 6 months (Median (IQR)) T= 4 (2‐5), C= 4 (2‐6), P = 0.57 (Mann Whitney) Functional impairment measure At 6 months (Median (IQR)) T= 106 (67.5‐121.5), C= 96.5 (56.5‐116.5), P = 0.26 (Mann Whitney) Canadian Neurological Scale Score At 6 months (Median (IQR)) T= 10 (8.5‐10.0), C= 9.5 (7.0‐10.0), P = 0.39 (Mann Whitney National Institute of Health Stroke Scale Score At 6 months (Median (IQR)) T= 8 (4‐26), C= 8 (6‐24), P = 0.37 (Mann Whitney) |

| Ricauda 2008 | Change in ADL (score 0 to 6) | At 6 months, mean (SD) T= 0.12 (0.64), C= 0.08 (0.73), P = 0.81 |

| Tibaldi 2004 | Behavioural disturbances | Sleeping disorders T= 5/56 (9%), C= 23/53 (43%), MD: ‐34%, 95% CI ‐50% to ‐19%, P < 0.001 Agitation/aggressiveness T= 5 /56 (9%), C= 22/53 (41.5%), MD ‐33% 95% CI ‐48% to ‐17%, P<0.001 Feeding disorders T= 5 /56 (9%), C= 21/53 (40%), MD ‐31% 95% CI ‐46% to ‐16%, P < 0.001 |

| Tibaldi 2009 | Activities of daily living Barthel Index |

ADL at 6 months mean change T= ‐1.95 (9.61) N=48, C= ‐0.30 (10.12) N=53, |

| Wilson 1999 | Barthel Index |

Barthel Index At 3 months (Median (IQR)) T= 16 (13‐19), C= 16 (12‐20) Barthel Index ‐ number (%) not assessed: T= 21 (28%), C= 18 (28%) Sickness Impact Profile: At 3 months (Median (IQR)) T= 24 (20‐31), C= 26 (20‐31) Sickness Impact Profile ‐ no (%) not assessed T= 31 (41%), C= 30 (46%) |

Quality of life or self reported health status

Seven trials assessed health status or quality of life using different measures (Analysis 1.6). One trial that recruited people with cellulitis reported 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) scores at six days' follow‐up (physical component scale MD ‐5.2, 95% CI ‐13.7 to 3.2; role physical scale MD 2.2, 95% CI ‐10.7 to 15.1; pain scale MD ‐3.8, 95% CI ‐10.6 to 3.0) (Corwin 2005). A second trial measuring health status with the SF‐36 reported follow‐up data at one year for the physical component scale (T: 3.6 (‐0.5 to 7.7), C: 2.2 (‐1.9 to 6.4); P = 0.47) and the mental component scale (T: 4.0 (‐0.9 to 8.9), C: 2.8 (‐2.4 to 8.0); P = 0.38) (Mendoza 2009). One trial measured quality of life with the SF‐12 at six weeks' follow‐up and reported similar scores for each group on the physical component (T: 42.2, C: 45.8; P = 0.18) and mental component scale (T: 50.4, C: 51.0; P = 0.81) (Richards 2005). Two trials assessed quality of life using the Nottingham Health Profile at six months' follow‐up (T: +1.09 (2.57) n = 48, C: +0.18 (SD 1.94); P = 0.046) (Tibaldi 2009), and (T: 3.6 (SD 7.9), C: 0.8 (SD 4.5); P = 0.04) (Ricauda 2008). One trial assessed a change from baseline in quality of life when a participant had a health event using the EORTC QLQ‐C30 (T: 0.58, C: 0.78, P = 0.05; emotional function hospital at home 3.27, hospital ‐6.94, P = 0.04) (Talcott 2011). One trial reported median values at three months' follow‐up for the Sickness Impact Profile (T: 24 (IQR 20 to 31), C: 26 (IQR 20 to 31); MD ‐2, 95% CI ‐4 to 4; P = 0.73) and the EuroQol (T: 0.64, n = 73, C: 0.63, n = 96; MD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.09; P = 0.94) (Wilson 1999).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 6 Quality of life/health status.

| Quality of life/health status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Admission avoidance quality of life | |||

| Corwin 2005 | SF 36 Physical functioning Role physical Pain | SF 36 Physical functioning Day 3 T= 37 (29.1), C= 41 (28.3) Mean difference ‐1.9, 95% CI ‐10.7 to 6.9 Day 6 T=50.7 (33.7), C=50.9 (31.6) Mean difference ‐5.2, 95% CI ‐13.7 to 3.2 Role physical Day 3 T= 5.4 (18.8), C=5.5 (19.7) Mean difference ‐1.8 95% CI ‐13.1 to 9.4 Day 6 T=21.1 (36.9), C=18.4 (36.5) Mean difference 2.2, 95% CI ‐10.7 to 15.1 Pain Day 3 T=57 (28.8), C=55.9 (25.4) Mean difference ‐2.5 95% CI ‐10.1 to 5.1 Day 6 T=69.8 (26.4), C=64.8 (25.6) Mean difference ‐3.8 95% CI ‐10.6 to 3.0 | Differences calculated on absolute differences between day 0 & day 3, or day 0 & day 6.

Numbers vary due to missing data (high score=better health) |

| Mendoza 2009 | SF 36 Physical component Mental component |

Physical component T= 3.6 (‐0.5 to 7.7), C= 2.2 (‐1.9 to 6.4), P = 0.47 Mental component T= 4.0 (‐0.9 to 8.9), C= 2.8 (‐2.4 to 8.0), P = 0.38 |

Score at 1 year (adjusted for baseline differences) |

| Ricauda 2008 | Nottingham Health Profile | 6 months, mean (SD) T= 3.6 (7.9), C= 0.8 (4.5), P = 0.04 |

Changes at 6 months |

| Richards 2005 | SF‐12 Mean physical and mental component score |

Physical component At 2 weeks T= 38.1, C= 40.2, P = 0.45 At 6 weeks T= 42.2, C=45.8, P = 0.18 Mental component At 2 weeks T=48.3, C=48.6, P = 0.91 At 6 weeks T = 50.4, C=51.0, P = 0.81 |

higher score=better health |

| Talcott 2011 | Quality of life EORTC QLQ C‐30 |

Role Function T= 0.58, C= 0.78, P = 0.05 Emotional Function T= 3.27, C= ‐6.94, P = 0.04 |

Quality of life data were collected at the time of consent to join the study, as soon as possible after the resolution of the episode. Data were collected for the first study episode. Change score |

| Tibaldi 2009 | Nottingham Health Profile | 6 months, mean (SD) T= +1.09 (2.57), C= +0.18 (1.94), P = 0.046 |

|

| Wilson 1999 | Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) Euroqol | SIP, median (IQR) T= 24 (20‐31), C= 26 (20‐31) Difference ‐2 (95% CI ‐4 to 4), P = 0.73 Euroqol, median T= 0.64, C= 0.63 Difference 0.01 (95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.09), P = 0.94 | At 3 months follow‐up |

Cognitive function and depression

Five trials measured cognitive function and depression (Analysis 1.7). One trial that recruited participants recovering from a stroke reported that hospital at home may lead to lower scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (lower scores = fewer symptoms) (MD 7 points, on a scale of 0 to 30, P < 0.001) (Ricauda 2004). A second trial, which recruited participants with COPD, reported a greater improvement for those allocated to hospital at home from baseline on the GDS at six months (T: ‐3.1 (SD 4.7), C: 0.7 (SD 3.2), P < 0.0001) (Ricauda 2008). One trial that recruited participants with acute chronic heart failure reported fewer depressive symptoms at six months follow‐up (measured by the GDS) for those allocated to admission avoidance hospital at home (mean change T: 1.48 (SD 1.86), C: 0.12 (SD 3.36); P = 0.02) (Tibaldi 2009). Wilson 1999 reported median (IQR) scores for the Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale at three months, with little to no difference between groups (T: 37 (30 to 42), C: 37 (31 to 43); MD 0, 95% CI ‐4.1 to 4.1).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 7 Cognitive function and depression.

| Cognitive function and depression | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results |

| admission avoidance ‐ cognitive function/well being | ||

| Caplan 1999 | Mental status questionnaire score from admission to discharge (maximum score 10); Number with confusion | Mean (SEM) T= 0.43 (0.12), C= 0.27 (0.12), NS Number with confusion T=0/51, C=10/49 |

| Ricauda 2004 | Geriatric Depression Scale score (range 0‐30)

higher scores indicate depression Change in Mini Mental State Exam (score 0 to 30) |

At 6 months, median (IQR)

T= 10 (5‐15), C=17 (13‐20), P<0.001 (Mann Whitney) At 6 months, mean (SD) T= ‐0.4 (4.0), C=‐0.5 (1.8), P = 0.88 |

| Ricauda 2008 | Change in geriatric Depression Scale score (range 0‐30) higher scores indicate depression | At 6 months, mean (SD) T= ‐3.1 (4.7), C=0.7 (3.2), P < 0.0001 |

| Tibaldi 2009 | Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) Geriatric Depression Scale |

At 6 months, mean change (SD) T= +0.07 (1.38), C= +0.08 (1.36), P = 0.97 At 6 months, mean change (SD) T= +1.48 (1.86), C= +0.12 (3.36), P = 0.02 |

| Wilson 1999 | Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale | At 3 months, median (IQR) T= 37 (30‐42), C= 37 (31‐43), Difference 0, 95% CI ‐4.1 to 4.1 |

Two trials used the mini‐mental state examination to assess cognitive functioning at six months' follow‐up and reported little to no difference between groups (T: ‐0.4 (SD 4.0), C: ‐0.5 (SD 1.8); P = 0.88) (Ricauda 2004); and (T: 0.07 (SD 1.38), C: 0.08 (SD 1.36); P = 0.97) (Tibaldi 2009). One trial that recruited participants with a mix of conditions reported cognitive function scores: mean T: 0.43 (standard error of the mean (SEM) 0.12), C: 0.27 (SEM 0.12), and that fewer people receiving hospital at home care experienced short‐term confusion during an episode of care (MD ‐20.4%, 95% CI ‐32% to ‐9%) (Caplan 1999).

Clinical outcomes

One trial measured clinical complications, with fewer participants allocated to hospital at home reporting bowel complications (difference ‐22.5%, 95% CI ‐34% to ‐10.8%) or urinary complications (difference ‐14.4%, 95% CI ‐25.4% to ‐3.3%) (Caplan 1999). In a trial recruiting participants with dementia, fewer participants in the hospital at home group were prescribed antipsychotic drugs at discharge (difference ‐14%, 95% CI ‐28% to 0.3%) (Tibaldi 2004). One trial that recruited people with cellulitis reported risk of advancement of cellulitis (hazard ratio (HR) 0.98, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.32) (Corwin 2005), and one trial recruiting participants with COPD reported that more participants were prescribed an antibiotic if they were allocated to hospital at home (difference 18%, 95% CI 1.4% to 34.6%) (Davies 2000). Talcott 2011 reported the difference in major complications during the episode of care (difference 1%, 95% CI ‐10 to 13%) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 8 Clinical outcomes.

| Clinical outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results |

| Clinical outcomes | ||

| Corwin 2005 | No advancement of cellulitis (indelible line drawn around peripheral margin of the cellulitis and dated) |

Mean (SD) days T= 1.5 (0.11), C= 1.49 (0.10), Mean difference 0.01 days, 95% CI ‐0.3 to 0.28 Days of no advancement of cellulites HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.32, P = 0.90 Days on intravenous antibiotics HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.12, P = 0.23 Days to discharge HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.23, P = 0.60 Days on oral antibiotics HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.45, P = 0.56 |

| Davies 2000 | Proportion of patients prescribed an antibiotic at 3 months | T= 56/100 (56%), C= 19/50 (38%), Difference 18%, 95% CI 1.4 to 34.6% |

| Talcott 2011 | Major medical complications during care in hospital at home or hospital | T= 4/47 (9%), C= 5/66 (8%), Difference 1%, 95% CI ‐10 to13% |

| Tibaldi 2004 | Use of antipsychotic drugs | On admission T= 26/56 (46.4%), C= 18/56 (32%), Difference 14.3%, 95% CI ‐3.7% to 31.1% On discharge T= 6/56 (11%), C = 13/53 (25%), Difference 14%, 95% CI ‐28% to 0.3% |

Place of residence at follow‐up (living in a residential setting)

Admission avoidance may reduce the likelihood of living in residential care, measured at discharge to six months' follow‐up (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.57; P < 0.0001; I2 = 78%; 5 trials; low‐certainty evidence) (Kalra 2000; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009). We downgraded the certainty of evidence due to the high level of statistical heterogeneity and imprecision (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 9 Place of residence at follow‐up (living in residential care).

Patient satisfaction

Admission avoidance may increase patient satisfaction with the health care received. Participants allocated to hospital at home care reported higher levels of patient satisfaction across a range of different conditions (5 studies; 646 participants; low‐certainty evidence). For participants with cellulitis, 27% (P < 0.0001) more participants in the hospital at home group reported increased satisfaction with their location of care compared with those admitted to hospital (Corwin 2005), and 40% (P < 0.001) more participants with community‐acquired pneumonia allocated to hospital at home reported that they were happy with their care (Richards 2005). Two trials (recruiting mainly elderly participants with a mix of medical conditions) also reported increased levels of satisfaction for those allocated to hospital at home care (median difference of 3 on a 0‐to‐18‐point scale, P < 0.0001) (Wilson 1999), and a MD of 0.9 on a 4‐point scale (P < 0.0001) (Caplan 1999). However, there was a low response rate for the control group in the latter trial: 40% compared with 78% in the hospital at home group (Caplan 1999). Some participants (6/101; 6%) refused hospital at home care and were admitted to hospital, and a greater number of participants allocated to hospital care (23/97; 24%) were not admitted because of refusal by the participant, caregiver, or general practitioner (Wilson 1999). One trial recruiting participants with COPD reported the number assessing satisfaction with care as very good or excellent (hospital at home 49/52 (94%), hospital 46/52 (88%); P = 0.83) (Ricauda 2008) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 10 Patient satisfaction.

| Patient satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Caplan 1999 | Satisfaction rated on a 4 point scale: 1=excellent, 2=good, 3=fair, 4=poor. | Mean score T= 1.1, C= 2.0, P < 0.0001 | Response rates were 78% for the treatment group, and 40% for the control. |

| Corwin 2005 | Patient satisfaction questionnaire (not described) |

Overall

T= 87/91 (96%), C=87/96 (96%), P = 0.12

Satisfaction with location of care

T= 85/91 (93%), C= 59/88 (66%), P < 0.0001

Location preference

In the hospital

T= 5/91 (5%), C= 27/88 (31%)

In the community

T= 78/91 (86%), C= 31/88 (35%)

No preference

T= 8/91 (9%), C= 30/88 (34%) P < 0.0001 |

Numbers for control group vary between 88 and 91 due to missing data Proportion of participants satisfied or very satisfied |

| Ricauda 2008 | Patient satisfaction questionnaire (not described) | T= 49/52 (94%), C= 46/52 (88%), P = 0.83 | Proportion of participants rating satisfaction as very good/excellent at discharge |

| Richards 2005 | Outcome not described | T= 24/24 (100%), C= 14/24 (60%), P = 0.001 | Proportion of patients very happy with care |

| Wilson 1999 | Patient satisfaction, scale 0 to 18 | Median (IQR) T= 15 (13 to 16.5), C= 12 (11 to 14), P < 0.0001 | At 2 weeks, or discharge |

Caregiver outcomes

One trial reported that caregivers in the hospital at home group had significantly higher levels of satisfaction compared with those in the hospital group (difference ‐0.8 on a 4‐point scale, P < 0.0001) (Caplan 1999), although the response rate was 27% in the hospital group and 55% in the hospital at home group. A second trial assessed caregiver satisfaction through semi‐structured interviews; caregivers reported that although hospital would potentially relieve them from caring, the upheaval of visiting hospital and the accompanying anxiety was a less satisfactory option (Wilson 1999). One trial recruiting participants with COPD reported change in relatives' stress at six months (mean scores (SD) T: 4.6 (5.6), C: 2.6 (6.1); P = 0.16) (Ricauda 2008) (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 11 Care giver outcomes.

| Care giver outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Care giver satisfaction | |||

| Caplan 1999 | Carer satisfaction | Mean score T= 1.1, C= 1.9, P < 0.0001 | Satisfaction rated on a 4 point scale: 1=excellent, 2=good, 3=fair, 4=poor |

| Ricauda 2008 | Change in Relative’s Stress Scale Score |

At 6 months, mean (SD) T= 4.6 (5.6), C= 2.6 (6.1), P = 0.16 |

|

Health professionals' views

One trial evaluated general practitioners' satisfaction with the service (T: 1.17, C: 1.8, score of 1 to 4, with high score being excellent, low score poor); the response rate was poor: 63% in the hospital at home group and 37% in the control group (Caplan 1999) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 12 Views of health professionals.

| Views of health professionals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Caplan 1999 | GP satisfaction | Mean score (95% CI) T= 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0), C= 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2), Difference: NS | Higher scores indicate higher satisfaction Response rate: T: 63%, C: 37% |

Length of stay in hospital and hospital at home

Seven trials reported the effect of admission avoidance hospital at home on length of hospital stay and hospital at home, with differing results (Analysis 1.13). Length of stay varied from a mean reduction of ‐8.09 days (95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐1.85) in a trial recruiting older people with varied health problems (Wilson 1999), to a mean increase of 15.90 days (95% CI 8.10 to 23.70) in a study that recruited patients recovering from a stroke (Ricauda 2004). One trial recruiting participants that were recovering from a stroke reported that 51 out of 153 (33%) of participants allocated to hospital at home received inpatient care within two weeks of randomisation, with a mean length of stay of 49 days; this exceeded the mean length of stay for those allocated to an inpatient hospital stroke team by 17 days (95% CI 7.9 to 25.3) (Kalra 2000).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 13 Length of stay.

| Length of stay | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Results | Outcomes | Notes |

| Hospital and hospital at home length of stay | |||

| Davies 2000 | Hospital length of stay | Median (IQR) 5 days (4 to 7) N=100 Mean (SD) 6.72 days (4.3) N=100 |

Data for the control group only |

| Harris 2005 | Average length of stay for the index episode until discharge from hospital or hospital at home (days) |

T= 11.33 days (SD 11.14) N=39, C= 7.83 days (7.35) N=37 Mean difference 3.5 95% CI ‐0.80 to 7.80 | IPD |

| Kalra 2000 | Average length of stay for readmission within two weeks of discharge (T) or index episode (C) (days) |

T= 48.6 (SD 26.7) N=51/146, C= 29.5 (SD 40.1) N=151 Difference 16.6, 95% CI 7.9 to 25.3 |

Data for inpatients treated by a stroke team |

| Mendoza 2009 | Average length of stay for the index episode (days) | T= 10.9 (SD 5.9) N=37, C= 7.9 (SD 3.0), P = 0.01 N=34 | |

| Ricauda 2004 | Average length of treatment (days) | T= 38.1 (SD 28.6) N=60, C= 22.2 (11.5) N=60 Difference 15.90, 95% CI 8.10 to 23.70 |

|

| Ricauda 2008 | Hospital at home and hospital length of stay (days) Total length of stay to include hospital transfers for the hospital at home group |

Total days of care (hospital plus hospital at home), mean (SD) T= 15.5 (SD 9.5) N=52, C= 52 (SD 7.9) Difference 4.50, 95% CI 1.14, 7.86 |

|

| Richards 2005 | Median number of days to discharge | T=4 (range 1‐14) N=24, C= 2 (range 0‐10) N=25 | |

| Tibaldi 2009 | Time in the emergency department (hours) Length of stay (days) |

Time in ED, mean (SD) T= 14.6 (3.4), C= 16.3 (3.0) Length of treatment, mean (SD) T= 20.7 (6.9) N=48, C= 11.6 (10.7) N=53, P = 0.001 |

|

| Wilson 1999 | Length of stay | Treatment N=102 Control N=97 Length of hospital stay in days, median T= 5.1 (13.53), C= 18.5 (18.51) days, P = 0.026 Total days of care (hospital plus hospital at home), median T= 9, C= 16 days; P = 0.031 Total days of care (hospital plus hospital at home and readmission days), mean (SD) T= 13.33 (17.26), C= 21.42 (25.46) Difference ‐8.09 95% CI ‐14.34 to ‐1.85 |

|

Cost

Two trials reported a full evaluation of healthcare resources and costs (Patel 2004 for Kalra 2000; Wilson 1999); one of these trials included informal‐care costs (Patel 2004 for Kalra 2000). Admission avoidance hospital at home may slightly decrease treatment costs, although this benefit is offset when the costs of informal care are considered (287 participants, low‐certainty evidence).

Elderly participants with a medical condition

One trial reported a cost minimisation analysis (Wilson 1999), finding an initial increase in the mean cost per day for hospital at home (difference GBP 99.71, P < 0.001) and little or no difference in cost at three months' follow‐up (GBP ‐210.9, 95% CI GBP ‐1025 to GBP 635.47). When participants refusing their allocated place of care (T: n = 6/101, C: n = 23/97) were removed from the analysis, there was a reduction in costs for those receiving hospital at home for the initial episode of care (difference GBP ‐1070.53, 95% CI GBP ‐1843.2 to GBP ‐245.73) and at three months' follow‐up (difference GBP ‐1063.45, 95% CI GBP ‐2043 to GBP ‐162.7). The difference in mean cost per day between hospital at home and hospital care was reduced, although hospital at home care remained more costly per day (GBP 206.68 versus GBP 133.7, MD GBP 72.98, P < 0.001).

Another trial, recruiting mainly elderly participants with a mix of conditions, examined health service costs (Board 2000 secondary publication to Caplan 1999), using average costs and reported reduced health service costs for the intervention group (T: AUD 1764 (SD AUD 1253), C: AUD 3775 (SD AUD 2496) for an episode of care, MD per episode AUD ‐2011) and cost per day (T: AUD 191 (SD AUD 58), C: AUD 484 (SD AUD 67.23); MD AUD 293). The costs of the nurse co‐ordinator and hospital doctor involved were excluded from this analysis (see Analysis 1.14.1). Mendoza 2009 reported the mean (SD) cost at one‐year follow‐up (T: EUR 2541 (1334), C: EUR 4502 (2153); difference EUR 1961, P < 0.001).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Admission avoidance hospital at home versus inpatient care, Outcome 14 Resources and costs.

| Resources and costs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Health service resources and costs | |||

| Caplan 1999 | Cost | Average cost per episode, mean (SD)

T= $1,764 ($1,253), C= $3,775 ($2,496)

Mean difference per episode $‐2011

Cost per day, mean (SD)

T= $191 ($58), C= $484 ($67.23) Mean difference per day ‐$293 |

Cost data financial year 1995/1996 |

| Corwin 2005 | Days on oral antibiotics | HR 1.09 (0.82 to 1.45), P = 0.56 | |

| Mendoza 2009 | Cost | Mean (SD) T= €2,541 (1,334), C= €4,502 (2,153) Difference €1,961 P < 0.0001 |

Difference attributed to fewer investigations. Costs include health service costs used during follow‐up period of 1 year, excludes informal care. |

| Nicholson 2001 | Costs | Cost per episode, mean (95% C) T= $745 ($595 to $895),C= $2543 ($1766 to $3321) Difference $1798, P < 0.01 Hospital at home costs 29% of the average hospital managed patient episode. Reported cost effectiveness ratio of 3:1 T + C costs GP 10% of costs, Domiciliary allied health 21% of costs, community nursing 28% of costs = 59% of costs and hospital care 41% of costs. If C=$895 then T= $1287 (59% of costs) Total costs=$2182 per patient episode of care |

Costs based on financial year 99/00; Used average DRG costs (Australian $), patient data for ED costs, and modelled costs for OPD clinic visits. HAH care individual costs, included direct and non direct costs. GP costs at $91.00 per hour. |

| Ricauda 2004 | Mean total cost (EUR converted to US$ 1 Euro=$1.3) | T= $6 413.5 per patient, C= $6 504.8 per patient Cost per patient per day (SD) T= $163 (20.5), C= $275.6 (27.7) P < 0.001 | |

| Ricauda 2008 | Hospital at home resources Total costs |

Nursing visits (range) T= 14.1 (3 to 38) Physician visits T= 9.9 (2 to 28) Visits to hospital for diagnosis T= 11 Total mean cost per patient T=$1,175.9, C= $1,390.9, P = 0.38 Total mean cost per day (SD) T= $101.4 (61.3), C= 151.7 (96.4) |

|

| Richards 2005 | Cost based on DRGs for control and actual cost for intervention | Mean cost per patient NZ$ T= $1157.9, C= $1556.28 | |

| Wilson 1999 | Cost | Cost of initial episode (95% CI) T= £2,568.9 (2,089.3 to 2,972.1) C= £2,880.6 (2,316.1 to 3,547.8) Difference ‐311.7, P > 0.43 Bootstrap difference using 1000 subsamples: ‐304.72 (‐1,112.4 to 447.9). Mean cost per day (95% CI) T= £204.6 (91.5 to 118.4) C= £104.9 £ (181.1 to 228.22) Mean difference £99.71 P < 0.001 Cost at 3 months (95% CI) T= £3,671.3 (3,140.5 to 4,231.3) C= £3,876.9 (3,224.51 to 4,559.6) Difference ‐205.7, P > 0.65 Bootstrap difference using 1000 subsamples: ‐210.9 (‐1,025 to 635.5) COSTS EXCLUDING REFUSERS Cost of initial episode, mean (95% CI) T= £2,594.4 (£2,170.36 to £3,143.5) C= £3,659.20 (£3,140.46 to £4,231.28) Mean difference ‐£1,064.79, P < 0.01. Bootstrap mean difference £1070.53, (95% CI‐£1843.2 to ‐£245.73) 95% CI derived using bootstrap method with 1000 subsamples Cost per day, mean (95% CI) T= £206.68 (£183.21 to £230.14) C= £133.7 (£124.6 to £142.8) Mean difference £72.98, P < 0.001 Cost at 3 months, mean (95% CI) T= £3,697.5 (£3136.13 to £4330.66) C= £4,761.3 (£4105.6 to £5476.6) Mean difference ‐£1,063.8, p = 0.025 Bootstrap mean difference: £1,063.45 (95% CI ‐£2043.8 to ‐£162.7) | Cost data financial year 1995/1996 BNF for medicines 1995 |

| Use of other social services | |||

| Davies 2000 | While receiving hospital at home care, or on discharge from hospital | Referred for increased social support T= 24/100 (24%), C= 3/50 (6%) Difference 18%, 95% CI 7.3% to 28.6% |

|

| Informal care inputs | |||

| Kalra 2000 | Informal care inputs | Received informal care: T= 100/140 (71%), C= 98/147 (67%), Difference 4.8%, 95% CI ‐5.9% to 15.3% Total from co residents over 12 months, hours (SD) T= 899.18 (1760), C= 718 (6778), P = 0.75 Total hours per average week from co residents (SD) T=46.38 (48.15), C= 33.71 (44.35), P = 0.02 Total hours from nonresidents over 12 months (SD) T= 79.7 (283), C= 127.44 (348), P = 0.27 Total average hours per week from non residents T= 4.79 (16.51), C= 5.03 (11.54), P = 0.88 Total hours over 12 months (SD) T= 979 (1749), C= 846 (1549), P = 0.49 | |

Participants recovering from a stroke

A trial recruiting participants recovering from a stroke compared stroke unit care, inpatient stroke team care, and hospital at home. In terms of immediate care, hospital at home care was less costly than inpatient stroke team care (MD GBP ‐2096, 95% CI GBP ‐3272 to GBP ‐920). The inclusion of costs of informal care, based on the minimum wage, resulted in a MD of GBP ‐2216 (95% CI GBP ‐4771 to GBP 339) (Patel 2004 for Kalra 2000) (Analysis 1.14). In another trial recruiting participants with a stroke, a small reduction in mean cost per patient was reported for those allocated to hospital at home (USD 6413.5 versus USD 6504.8) (Ricauda 2004), which translated to a lower cost per day for hospital at home of USD 112.00 (USD 163.0, SD 20.5 versus USD 275.6, SD 27.7; P < 0.001).

COPD and community‐acquired pneumonia

One trial recruiting participants with COPD reported a lower mean health service cost for participants allocated to hospital at home; hospital costs were based on an average DRG (a diagnostic‐related group categorised by resource use) cost per bed day (cost per episode MD GBP ‐1798, P < 0.01) (Nicholson 2001). Another trial recruiting participants with community‐acquired pneumonia, again using DRG costs for the control and actual resource use for costing the intervention, reported a reduced cost for those allocated to hospital at home (mean cost per patient T: NZD 1157.9, C: NZD 1556.28) (Richards 2005). Ricauda 2008 reported the total mean cost per patient (T: USD 1175.9, C: USD 1390.9, P = 0.38) and the total mean cost per day (T: USD 101.4 (SD 61.3), C: USD 151.7 (SD 96.4)).

Use of other health services and informal care

Davies 2000 reported an increase in referrals for social support for participants with COPD who were allocated to hospital at home. This occurred during the time they were receiving hospital at home or when the control group had been discharged from hospital (24% versus 6%, difference 18%, 95% CI 7.3% to 28.6%) (Analysis 1.14.2). One trial recruiting participants recovering from a stroke reported that 71% (100/140) of those allocated to hospital at home received informal care, compared with 67% (98/147) receiving care from the inpatient stroke team (Patel 2004). This translated into 979 hours (SD 1749) versus 846 hours (SD 1549) of care over a 12‐month period (Analysis 1.14.3).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Admission avoidance hospital at home, with the option of transfer to hospital, may provide an effective alternative to inpatient care for a select group of elderly patients requiring hospital admission. Admission avoidance hospital at home probably makes little or no difference to the risk of death at six months' follow‐up or transfer to hospital (moderate‐certainty evidence); it may increase the likelihood of living at home (low‐certainty evidence). The increased satisfaction reported by patients allocated to hospital at home (low‐certainty evidence) must be balanced against the lack of evidence on the views of caregivers. Interviews with patients reveal that the most‐valued aspects of hospital at home care are the quality of communication and personal care received (Wilson 1999).

The total costs for the initial episode of care were estimated at 3 and 12 months after randomisation. We were not able to combine cost data due to the different ways costs had been calculated, and only two trials conducted a full economic evaluation (Jones 1999 for Wilson 1999; Patel 2004 for Kalra 2000). Hospital at home may decrease treatment costs slightly when compared with admission to an acute hospital ward (low‐certainty evidence). However, caregiver costs may offset this difference.

There was some variation in the way the admission avoidance hospital at home schemes operated. Admission avoidance hospital at home schemes admitted patients directly from the community (Harris 2005; Kalra 2000; Vianello 2013; Wilson 1999), outpatients (Talcott 2011), and from an accident and emergency department (Andrei 2011; Caplan 1999; Corwin 2005; Davies 2000; Mendoza 2009; Nicholson 2001; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Richards 2005; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009). Three trials evaluated interventions where the patient could be living alone, and five trials required a caregiver to be either living with the patient or nearby. Nonetheless, there were some important common features, which included care being co‐ordinated in each of the schemes by a multidisciplinary team; the provision of 24‐hour cover if required, with access to a doctor; and a safe home environment.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence indicates that admission avoidance hospital at home can provide an effective alternative to inpatient care for a select group of patients requiring hospital admission. However, determining the type of patients who are most likely to benefit is not simple. The majority of the included trials recruited participants who were elderly with a medical event, including stroke, COPD, and heart failure, that required admission to hospital. Their average age ranged from 70 to over 80 years. The patients opting to participate in the trials may prefer treatment at home, this may be why high levels of satisfaction are reported for those receiving healthcare at home. All trials but one, Andrei 2011, were conducted in high‐income countries.

Half of the trials excluded patients who did not have continuous family support (Caplan 1999; Mendoza 2009; Ricauda 2004; Ricauda 2008; Richards 2005; Tibaldi 2004; Tibaldi 2009; Vianello 2013). Although none of the included trials specifically looked into the socioeconomic characteristics of the excluded patients, it has been suggested that more disadvantaged areas have a higher percentage of informal caregivers (Young 2005). Three trials included participants from ethnic minorities, ranging from 14% to 20% of all recruited participants (Corwin 2005; Richards 2005; Talcott 2011); the authors did not report subgroup analysis for these participants.

Quality of the evidence

While we assessed the overall risk of bias as low, the studies included in this review were small, with the largest study recruiting 197 participants who contributed to the analysis. The meta‐analysis for the main outcome included a subgroup of six trials recruiting participants with similar conditions (older patients with a mix of medical conditions) to limit heterogeneity. A further concern is the role of chance and the fact that risk of publication bias cannot be ruled out.

Potential biases in the review process

We limited publication bias by conducting an extensive search that included different databases of published articles and sources of unpublished literature. Over the last 20 years we have established an international network of people working in this field who alert us to new randomised controlled trials. Two people screened all search results in order to reduce the risk of missing a study for inclusion, and the review authors discussed studies for possible inclusion to check that the inclusion criteria had been consistently applied.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Other reviews have analysed the effect of hospital at home schemes for patients with specific conditions, such as COPD and heart failure (Jeppesen 2012; Qaddoura 2015). For patients with COPD, it was reported that hospital at home reduced the number of readmissions when compared with hospital care, with inconclusive evidence for mortality, health‐related quality of life, cost, and clinical outcomes (Jeppesen 2012). The findings of a review of a small number of studies that specifically recruited patients with heart failure indicated a slight increase of time to readmission, improved health‐related quality of life, and reduced index costs, with limited evidence for mortality for those allocated to hospital at home. The authors judged these studies to be of modest quality (Qaddoura 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Problems can arise when comparisons are made between countries. The 16 trials included in this review came from Australia, Italy, New Zealand, Romania, Spain, the UK, and the US. Although the health systems in these countries vary with respect to the way healthcare financing is structured, the policy objectives are the same, with admission avoidance hospital at home being provided to control costs and reduce demand for inpatient hospital beds (Naik 2006). The level of existing primary care in a country, and the enthusiasm of local clinicians and healthcare managers, may determine the degree to which admission avoidance hospital at home operates as an outreach model or is run by supplementing existing primary care services. The way health care for the control group is organised will have an impact on outcome. The entry criteria required patients to be clinically stable and not requiring specialist diagnostic investigation or emergency interventions. Patients eligible for the trials included in this review did not include those whose condition was so severe that death was an expected outcome. Furthermore, patients whose condition unexpectedly deteriorated, or who could no longer be managed at home, had access to hospital admission. Interestingly, fewer behavioural problems were reported for those allocated to admission avoidance hospital at home in the trial recruiting patients with dementia, despite them experiencing serious cognitive and functional decline (Tibaldi 2004).

Although admission avoidance hospital at home provides an alternative to inpatient admission for some patients, the volume of such patients recruited to the included trials was low, and some of these patients will require access to hospital services, thus making the closure of a ward or hospital in favour of hospital at home an unrealistic option. Furthermore, the effectiveness of admission avoidance hospital at home may be reduced if hospital admission incorporates aspects of care known to be effective for these groups of patients, such as stroke unit care or comprehensive geriatric assessment (Stroke Unit Trialist; Stuck 1993).

It should be noted that admission avoidance hospital at home does not totally substitute for hospital, in that admission to hospital remains an option if required. One trial recruiting participants recovering from a stroke reported that 51 out of 153 (33%) of the patients allocated to hospital at home received inpatient care within two weeks of randomisation (Kalra 2000). In another trial, a small proportion (6 out of 101; 6%) refused hospital at home care and were admitted to hospital (Wilson 1999).

Implications for research.

Over the last 15 years the randomised evidence has grown from 1 to 16 trials, despite the practical difficulties of conducting randomised controlled trials of service innovations, which is encouraging. However, the continuing lack of functional outcome measures, failure to record place of residence at follow‐up, and absence of economic evaluations are disappointing. Future research of admission avoidance hospital at home should continue to measure mortality, readmission (with particular attention to the transfer of patients between admission avoidance hospital at home and inpatient care), and place of residence at follow‐up. In addition, clinical and dependency data of recruited patients should be collected using standardised measures to facilitate the application of evidence. Trials should also include a formal, planned economic analysis using costs that are sensitive to the different resources used during an episode of care. Comparisons with other ways of organising inpatient care, for example incorporating aspects of case management and comprehensive assessment, would also improve the evidence supporting decisions about how services should be organised to maximise health outcomes. The effect of the intervention for patient groups considered to be at higher risk of hospital admission should also be considered. Some of the factors to take into account are age, social circumstances, and comorbidities. Finally, the role of advanced portable medical devices and communication technologies in admission avoidance hospital at home could be explored in pilot studies.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 March 2016 | New search has been performed | New searches performed. Six new trials identified. |

| 2 March 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Daniela C Gonçalves‐Bradley is a new author; the review includes 16 trials (6 trials included in this update). Methods have been updated to align with current Cochrane guidance. |

History

Review first published: Issue 4, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 July 2011 | Amended | Reference revised to published review. |

| 8 June 2011 | Amended | Title changed for consistency and changes to published notes. |

| 17 February 2010 | Amended | Change to published notes. |

| 1 August 2008 | New search has been performed | This review is an updated search and partial update from the original review (Shepperd 1998). Shepperd 1998 has been split into three reviews, of which this is one. |

| 10 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This review is the third update; the original review was first published in Issue 1, 1998 of the Cochrane Library (Shepperd 1998).The original review has been separated into three distinct reviews: Hospital at home admission avoidance, Hospital at home early discharge, and Hospital at home: home‐based end‐of‐life care. The titles have been changed for consistency. Hospital at home early discharge, Shepperd 2009, and Hospital at home: home‐based end‐of‐life care, Shepperd 2011, are published in the Cochrane Library.

Acknowledgements

Dr Roger Harris and Joanne Broad for contributing data from the New Zealand trial to the individual patient data meta‐analysis. Robert M Angus for collaborating on previous versions of the review. Nia Roberts and Paul Miller for updating and conducting the searches, and Julia Worswick for editorial support. We would also like to thank the peer reviewers for their helpful comments: Craig Ramsay, Paul Miller, Orlaith Burke, Christopher Cates, Julia Worswick, and Tomas Pantoja (internal Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) editor). This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure funding and a Cochrane programme grant to the EPOC Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies