Abstract

Background

Alcohol use and misuse in young people is a major risk behaviour for mortality and morbidity. Motivational interviewing (MI) is a popular technique for addressing excessive drinking in young adults.

Objectives

To assess the effects of motivational interviewing (MI) interventions for preventing alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems in young adults.

Search methods

We identified relevant evidence from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 12), MEDLINE (January 1966 to July 2015), EMBASE (January 1988 to July 2015), and PsycINFO (1985 to July 2015). We also searched clinical trial registers and handsearched references of topic‐related systematic reviews and the included studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials in young adults up to the age of 25 years comparing MIs for prevention of alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems with no intervention, assessment only or alternative interventions for preventing alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included a total of 84 trials (22,872 participants), with 70/84 studies reporting interventions in higher risk individuals or settings. Studies with follow‐up periods of at least four months were of more interest in assessing the sustainability of intervention effects and were also less susceptible to short‐term reporting or publication bias. Overall, the risk of bias assessment showed that these studies provided moderate or low quality evidence.

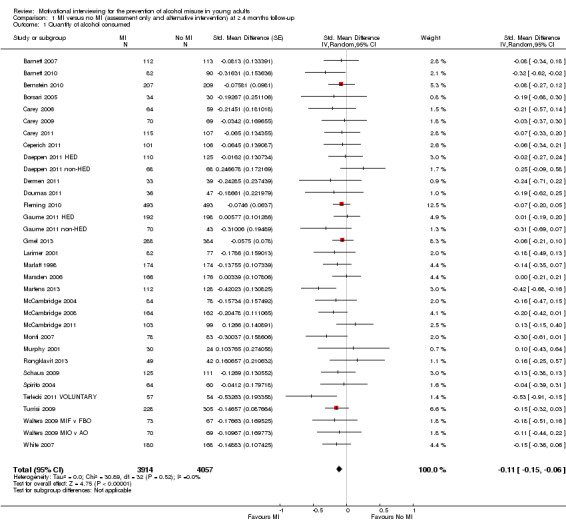

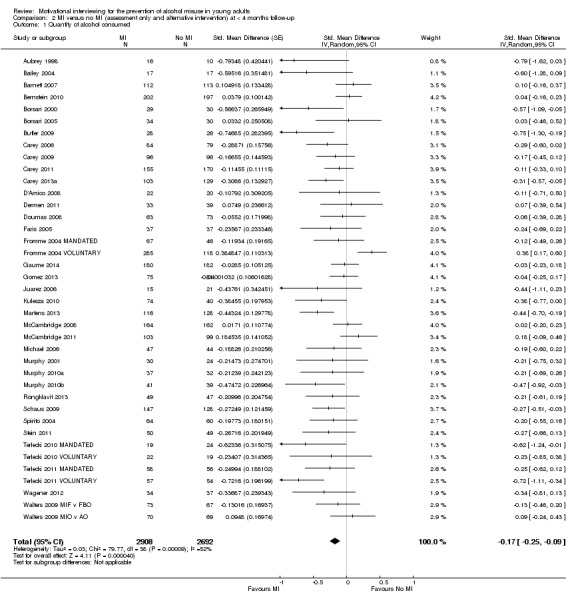

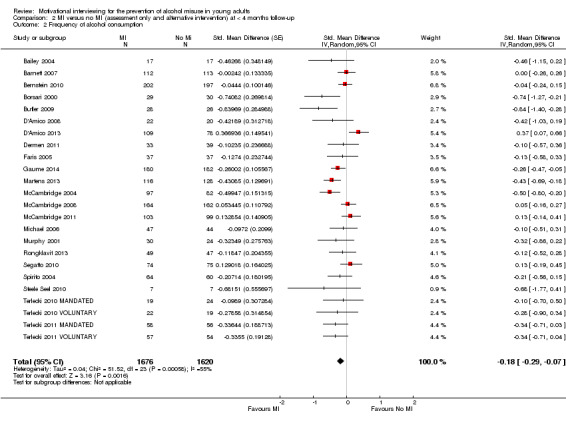

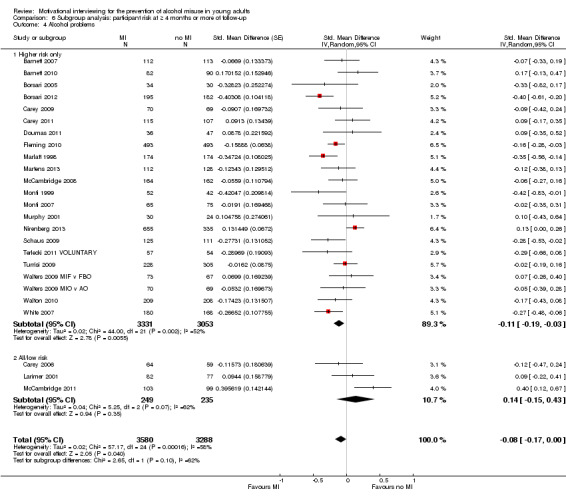

At four or more months follow‐up, we found effects in favour of MI for the quantity of alcohol consumed (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.15 to −0.06 or a reduction from 13.7 drinks/week to 12.5 drinks/week; moderate quality evidence); frequency of alcohol consumption (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.21 to −0.07 or a reduction in the number of days/week alcohol was consumed from 2.74 days to 2.52 days; moderate quality evidence); and peak blood alcohol concentration, or BAC (SMD −0.12, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.05, or a reduction from 0.144% to 0.131%; moderate quality evidence).

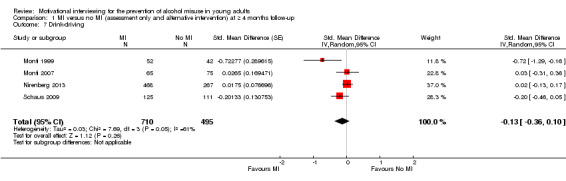

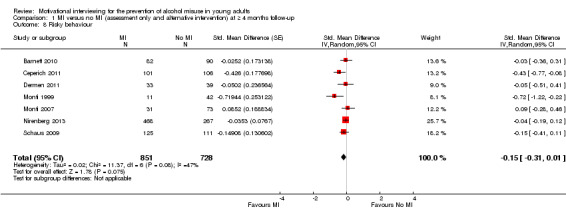

We found a marginal effect in favour of MI for alcohol problems (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.00 or a reduction in an alcohol problems scale score from 8.91 to 8.18; low quality evidence) and no effects for binge drinking (SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.02, moderate quality evidence) or for average BAC (SMD −0.05, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.08; moderate quality evidence). We also considered other alcohol‐related behavioural outcomes, and at four or more months follow‐up, we found no effects on drink‐driving (SMD −0.13, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.10; moderate quality of evidence) or other alcohol‐related risky behaviour (SMD −0.15, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.01; moderate quality evidence).

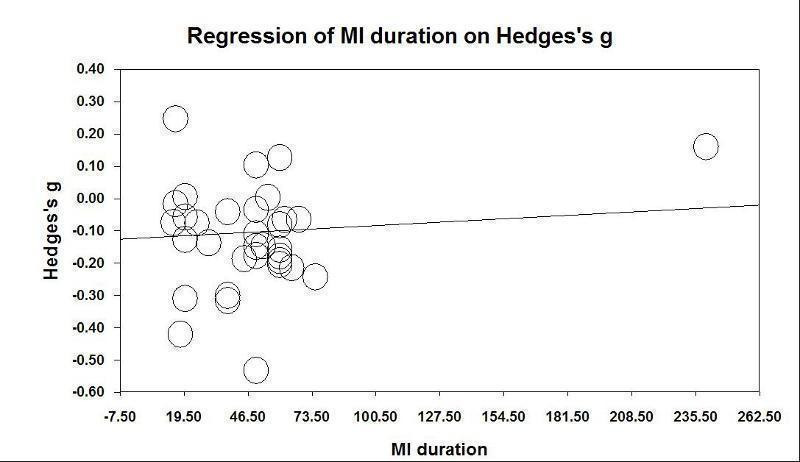

Further analyses showed that there was no clear relationship between the duration of the MI intervention (in minutes) and effect size. Subgroup analyses revealed no clear subgroup effects for longer‐term outcomes (four or more months) for assessment only versus alternative intervention controls; for university/college vs other settings; or for higher risk vs all/low risk participants.

None of the studies reported harms related to MI.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review indicate that there are no substantive, meaningful benefits of MI interventions for preventing alcohol use, misuse or alcohol‐related problems. Although we found some statistically significant effects, the effect sizes were too small, given the measurement scales used in the included studies, to be of relevance to policy or practice. Moreover, the statistically significant effects are not consistent for all misuse measures, and the quality of evidence is not strong, implying that any effects could be inflated by risk of bias.

Plain language summary

Motivational interviewing (MI) for preventing alcohol misuse in young adults is not effective enough

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of motivational interviewing (MI), a way of counselling to bring out and strengthen reasons for changing behaviour, for preventingalcohol misuse in young people.

Background

Alcohol misuse results in about 3.3 million deaths each year worldwide. Around 9% of deaths that occur in people aged 15 to 29 years are attributable to alcohol, mainly resulting from car accidents, homicides (murders), suicides and drownings.

We wanted to find out if MI had an effect on the prevention of alcohol misuse and problems in young adults aged up to 25 years. If those involved with tackling alcohol misuse in young people are to apply MI in practice, clear evidence needs to support it.

Search date: the evidence was current to December 2015.

Study characteristics

We found a total of 84 randomised controlled trials (studies where participants were randomly divided into one of two or more treatment or control groups) that compared MI with either no intervention or with a different approach. Seventy of these trials focused on higher risk individuals or settings. We were mainly interested in trials with a follow‐up period of 4 or more months, and the typical follow‐up period was 12 months. We also evaluated the quality of the studies' designs and their applicability to our research, finding that these studies provided moderate to low quality evidence.

In 66 trials, the MI consisted of a single, individual session. In 12 studies, young people attended multiple individual sessions or mixtures of both individual sessions and group sessions. Six trials used group MI sessions only. The length of MI sessions varied, but in 57 studies it was one hour or less. The shortest MI intervention was 10 to 15 minutes, and the longest had five dedicated MI sessions over a 19‐hour period.

Settings for the trials varied: 58 of the 84 studies took place in college (mainly university but also four vocational) settings. The remaining trials took place in healthcare locations, a youth centre, local companies, a job‐related training centre, an army recruitment setting, UK drug agencies and youth prisons.

The total number of young adults was 22,872, aged on average from 15 to 24 years old. The proportion of males in the trials with both males and females ranged from 22% to 90%. The ethnicity of the young adults was typically mixed, but 52 of the 67 studies that reported ethnicity involved mostly white people.

Key results

At four or more months follow‐up, we found only small or borderline effects showing that MI reduced the quantity of alcohol consumed, frequency of alcohol consumption, alcohol problems and peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC). We didn't find any effects for binge drinking, average BAC, drink‐driving or other alcohol‐related risky behaviour. We found no relationship between the length of MI and its effectiveness. Also, there were no clear subgroup differences in effects when we examined the type of comparison group (assessment only control or alternative intervention, the setting (college/university vs other settings), or risk status (higher risk students vs all/low‐risk students).

None of the studies reported harms related to MI.

Although we found some significant effects for MI, our reading of these results is that the strength of the effects was slight and therefore unlikely to confer any advantage in practice.

Quality of evidence

Overall, there is only low or moderate quality evidence for the effects found in this review. Many of the studies did not adequately describe how young people were allocated to the study groups or how they concealed the group allocation to participants and personnel. Study drop‐outs were also an issue in many studies. These problems with study quality could result in inflated estimates of MI effects, so we cannot rule out the possibility that any slight effects observed in this review are overstated.

The US National Institutes of Health provided funding for half (42/84) of the studies included in this review. Twenty‐nine studies provided no information about funding, and only eight papers had a clear conflict of interest statement.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings ‐ 4 months or more of follow‐up.

| Motivational interviewing versus no motivational interviewing (assessment only or alternative intervention) for prevention of alcohol misuse | ||||||

|

Patient or population:young adults aged up to 25 years Settings: education, health, criminal justice or community settings Intervention: motivational interviewing Comparison: no intervention/placebo/treatment as usual Follow‐up: ≥ 4 months Measurement: self reported alcohol consumption (questionnaire scale) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Quantity of alcohol consumed | The mean number of drinks per week was 13.74 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 10.77, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.11) corresponds to a decrease of 1.2 drinks consumed each week (95% CI 0.7 to 1.6), from an average of 13.7 drinks per week to 12.5 drinks per week, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.11 (−0.15 to −0.06) | 7971 (33) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | The mean drinking days per week was 2.74 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 1.54, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.14) corresponds to a decrease of 0.22 drinking days per week (95% CI 0.11 to 0.32), from an average of 2.74 drinking days per week to 2.52 drinking days per week, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.14 (−0.21 to −0.07) | 4377 (17) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Binge drinking | Binge drinking frequency in the previous month was 5.05 at baseline for the whole sample, with a standard deviation of 4.53, in the study by Carey 2011 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.04) corresponds to a decrease in binge drinking frequency in the previous month of −0.2 binge drinking occasions (95% CI −0.4 to 0.1), from an average of 5.1 occasions to 4.9 occasions per week, based on Carey 2011. | SMD −0.04 (−0.09 to 0.02) | 5479 (21) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Alcohol problems | The mean alcohol problems scale score was 8.91 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 9.17 (the 69‐point RAPI scale used by Martens 2013) | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.08) corresponds to a decrease of 0.73 on the alcohol problems scale score (95% CI 0.00 to 1.56), from an average of 8.91 to 8.18, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.00) | 6868 (25) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low | Downgraded 2 levels due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 58%) and risk of bias |

| Average BAC | The average BAC was 0.082% at baseline for the whole sample, with a standard deviation of 0.057, in the study by Carey 2011 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.05) corresponds to a decrease of −0.003 for average BAC (95% CI −0.010 to 0.005), from an average of 0.082% to 0.079%, based on Carey 2011 | SMD −0.05 (−0.18 to 0.08) | 901 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Peak BAC | The mean peak BAC was 0.144% in the control group, with a standard deviation of 0.111, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.12) corresponds to a decrease of 0.013 for peak BAC (95% CI 0.006 to 0.025), from an average of 0.144% to 0.131%, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.12 (−0.20 to −0.05) | 2790 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Drink‐driving | The number of drink‐driving occasions in the previous 12 months was 7.8 at baseline in the control group, with a standard deviation of 16.9, from the DrInC‐2L measure, in Schaus 2009 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.13) corresponds to a decrease of −2.2 drink‐driving occasions (95% CI −6.1 to 1.7), from an average of 7.8 to 5.6, based on Schaus 2009 | SMD −0.13 (−0.36 to 0.10) | 1205 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 61%) |

| Risky behaviour | The number of times foolish risks were taken in the previous 12 months was 6.6 at baseline in the control group, with a standard deviation of 11.9, from the DrInC‐2L measure, in Schaus 2009 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.15) corresponds to a decrease of −1.8 risk taking occasions (95% CI −3.7 to 0.1), from an average of 6.6 to 4.8, based on Schaus 2009 | SMD −0.15 (−0.31 to 0.01) | 1579 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BAC: blood alcohol concentration; CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; DDQ: Daily Drinking Questionnaire; RAPI: Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

In the columns illustrating comparative risks: for outcomes where the pooled analysis point estimate and confidence interval showed some effect, we have used results (mean scores and standard deviations) from Martens 2013 to illustrate the effect sizes in terms of the measures used in that study. We chose Martens 2013 because the outcome measures they use are well known, generally well regarded, and are typical of the measures used in this field of research: they used the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) and the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI). For similar reasons, we used Carey 2011 as a basis for illustrating effect sizes for binge drinking, as they also based their measures on the DDQ, and Schaus 2009 as they used the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC‐2L; Miller 1995b). Furthermore, the sample sizes were typically larger than similar studies with potentially more reliable indication of variance (SD) for relevant outcomes.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings ‐ less than four months follow‐up.

| Motivational interviewing versus no motivational interviewing (assessment only or alternative intervention) for prevention of alcohol misuse | ||||||

|

Patient or population: young people aged up to 25 years Settings: education, health, criminal justice or community settings Intervention: motivational interviewing Comparison: no intervention/placebo/treatment as usual Follow‐up: < 4 months Measurement: self reported alcohol consumption (questionnaire scale) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Quantity of alcohol consumed | The mean number of drinks per week was 13.74 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 10.77, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.18) corresponds to a decrease of 1.8 drinks consumed each week (95% CI 1.0 to 2.7), from an average of 13.7 drinks per week to 11.9 drinks per week, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.17 (−0.25 to −0.09) | 5600 (39) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low | Downgraded 2 levels due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 52%) and risk of bias. |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | The mean drinking days per week was 2.74 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 1.54, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.18) corresponds to a decrease of 0.28 drinking days per week (95% CI 0.11 to 0.45), from an average of 2.74 drinking days per week to 2.46 drinking days per week, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.18 (−0.29 to −0.07) | 3296 (24) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low | Downgraded 2 levels due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 55%) and risk of bias. |

| Binge drinking | Binge drinking frequency in the previous month was 5.05 at baseline for the whole sample, with a standard deviation of 4.53, in the study by Carey 2011 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.13) corresponds to a decrease in binge drinking frequency in the previous month of 0.6 binge drinking occasions (95% CI 0.1 to 1.0), from an average of 5.1 occasions to 4.5 occasions per week, based on Carey 2011. | SMD −0.13; (−0.23 to 0.03) | 4090 (25) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low | Downgraded 2 levels due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 54%) and risk of bias. |

| Alcohol problems | The mean alcohol problems scale score was 8.91 in the control group, with a standard deviation of 9.17 (the 69‐point RAPI scale was used by Martens 2013) | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.10) corresponds to a decrease of 0.92 on the alcohol problems scale score (95% CI 0.09 to 1.65), from an average of 8.91 to 7.99, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.10; (−0.18 to −0.01) | 5109 (34) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Average BAC | The average BAC was 0.082% at baseline for the whole sample, with a standard deviation of 0.057, in the study by Carey 2011 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.14) corresponds to a decrease of −0.008 for average BAC (95% CI −0.017 to 0.001), from an average of 0.082% to 0.074%, based on Carey 2011 | SMD −0.14; (−0.30 to 0.01) | 1096 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Peak BAC | The mean peak BAC was 0.144% in the control group, with a standard deviation of 0.111, from the DDQ measure in Martens 2013 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.23) corresponds to a decrease of 0.026 for peak BAC (95% CI 0.014 to 0.036), from an average of 0.144% to 0.118%, based on Martens 2013 | SMD −0.23 (−0.32 to −0.13) | 2408 (14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Drink‐driving | The number of drink‐driving occasions in the previous 12 months was 7.8 at baseline in the control group, with a standard deviation of 16.9, from the DrInC‐2L measure, in Schaus 2009 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.22) corresponds to a decrease of −3.7 drink driving occasions (95% CI −6.4 to 1.0), from an average of 7.8 to 4.1, based on Schaus 2009 | SMD −0.22 (−0.38 to −0.06) | 895 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to risk of bias |

| Risky behaviour | The number of times foolish risks were taken in the previous 12 months was 6.6 at baseline in the control group, with a standard deviation of 11.9, from the DrInC‐2L measure, in Schaus 2009 | The SMD from the meta‐analysis (−0.05) corresponds to a decrease of −0.6 risk taking occasions (95% CI −3.9 to 2.6), from an average of 6.6 to 6.0, based on Schaus 2009 | SMD −0.05 (−0.33 to 0.22) | 745 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Downgraded 1 level due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 67%) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BAC: blood alcohol concentration; CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; DDQ: Daily Drinking Questionnaire; RAPI: Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

In the columns illustrating comparative risks: for outcomes where the pooled analysis point estimate and confidence interval showed some effect, we have used results (mean scores and standard deviations) from Martens 2013 to illustrate the effect sizes in terms of the measures used in that study. We chose Martens 2013 because the outcome measures they use are well‐known, generally well regarded, and are typical of the measures used in this field of research: they used the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) and the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI). For similar reasons, we used Carey 2011 as a basis for illustrating effect sizes for binge drinking, as they also based their measures on the DDQ, and Schaus 2009 as they used the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrinC‐2L; Miller 1995b) Furthermore, the sample sizes were typically larger than similar studies with potentially more reliable indication of variance (s.d.) for relevant outcomes.

Background

Description of the condition

Globally, harmful use of alcohol results in approximately 3.3 million deaths each year (WHO 2014). Around 9% of deaths between the ages of 15 and 29 years are attributable to alcohol, mainly resulting from car accidents, homicides, suicides and drownings (WHO 2011). Europe has the highest levels of mortality attributable to alcohol consumption amongst all age groups (WHO 2014).

Hazardous drinking levels for men (consuming over 40 g/day) doubles the risk of liver disease, raised blood pressure, some cancers and violent death (because some people who have this average alcohol consumption drink heavily on some days). For women, over 24 g/day average alcohol consumption increases the risk for developing liver disease and breast cancer (Corrao 1999; Edwards 1994; Greenfield 2001; Thakker 1998).

Description of the intervention

Motivational interviewing (MI) was developed as a way to help people work through ambivalence and commit to change (Miller 1983). Miller 1995a defined MI as "a directive, client‐centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence". As Miller 1996 and Miller 2002 have said, the term 'motivational interviewing' pertains both to a style of relating to others and a set of techniques to facilitate that process. Its five tenets include:

adopting an empathic, non‐judgemental stance;

listening reflectively;

developing discrepancy;

rolling with resistance and avoiding argument;

supporting efficacy to change.

Practitioners commonly combine MI with other intervention components, which have been called adaptations of MI (Burke 2003). The most widely used adaptation of MI is motivational enhancement therapy (MET), which combines MI components with personal feedback of assessment results (Miller 1993).

How the intervention might work

The theoretical basis of MI and motivational enhancement is grounded in client‐centred therapy and social cognitive theory. Firstly, studies have demonstrated that therapist behaviours such as genuineness, warmth and empathy promoted change in the client, while other behaviours such as non‐acceptance and negative confrontation were associated with failure to change or with other unhelpful outcomes (Miller 1993; Paterson 1985). Secondly, the emergence of social cognitive theories helped to promote the recognition that the external, social environment and the individual's interactions with it were important factors in motivation for changing drinking behaviours (Bandura 1977; Maisto 1999). Thirdly, the popularity of the transtheoretical model of behaviour change has increased awareness of change as occurring through a number of stages or steps (Prochaska 1992).

Why it is important to do this review

There have been several reviews of MI in the addiction field in recent years. Noonan 1997 reviewed 11 clinical trials of MIs that were available at the time and concluded that nine of the studies supported the efficacy of MIs for addictive behaviours. Following this study, Dunn 2001 performed a systematic review of 29 randomised trials of brief interventions that claimed to use the principles and techniques of MI and suggested that the strongest evidence for efficacy was found in the alcohol and drug abuse areas. A qualitative review of 26 studies of MIs by Burke 2002b concluded that the research supported the efficacy of MIs for alcohol problems, drug addiction, compliance in patients with hypertension and bulimia, as well as the efficacy of MIs for encouraging compliance in patients with diabetes. Burke 2003 and Burke 2002a performed a meta‐analysis of 30 controlled clinical trials investigating MIs. They concluded that MIs were equivalent to other active treatments and yielded moderate effects compared to no treatment or placebo for problems involving alcohol, drugs, diet and exercise. However, the effectiveness of MI across providers, populations, target problems, and settings was highly variable. Another qualitative review of the use of METs for substance use in adolescents reported that clinical trials of METs indicate that they decrease substance‐related negative consequences and problems, substance use and increase treatment engagement, with results particularly strong for those with heavier substance use patterns, less motivation to change, or both (O' Leary 2004). Hettema 2005 conducted a meta‐analysis of 72 clinical trials spanning a range of target problems including alcohol misuse. The average short‐term between‐group effect size of MI was 0.77, decreasing to 0.30 at one‐year follow‐up. Observed effect sizes of MI were larger with ethnic minority populations and when the practice of MI was not manual‐guided. Vasilaki 2006 conducted a meta‐analysis of 22 studies of the efficacy of MI in reducing alcohol consumption and concluded that brief MI is effective. Similarly, Rubak 2006 conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 72 randomised controlled trials of MI to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention in different areas of disease and showed a significant effect of MI for combined effect estimates for body mass index, total blood cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, blood alcohol concentration and standard ethanol content. Lundahl 2010 carried out a meta‐analysis of 119 studies targeting outcomes including substance use (tobacco, alcohol, drugs, marijuana), health‐related behaviours (diet, exercise, safe sex), gambling and engagement in treatment variables. Judged against weak comparison groups, MI produced statistically significant, durable results in the small effect range. Smedslund 2011 conducted a Cochrane systematic review of 59 randomised controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of MI for substance abuse on drug use, retention in treatment, readiness to change, and number of repeat convictions. They concluded that MI can reduce the extent of substance abuse compared to no intervention.

Tait 2003 evaluated the effectiveness of brief interventions (BI) with adolescents (mean age < 20 years) in reducing alcohol, tobacco or other drug use by means of a systematic review. They concluded that across a diverse range of settings, BI conferred benefits to adolescent substance users with a small effect on alcohol consumption and related measures. Grenard 2006 reviewed 17 clinical studies of MI interventions applied to adolescents and young adults using alcohol or other psychoactive substances. This review revealed mixed findings for the efficacy of brief MI among these populations. However, in 29% of the studies there was a clear advantage for the brief MI compared to standard care or other programming. Carey 2007 conducted a meta‐analysis of 62 studies and 98 intervention conditions with college drinkers. Over follow‐up intervals lasting up to six months, moderator analyses suggested that individual, face‐to‐face interventions using MI and personalised normative feedback predict greater reductions in alcohol‐related problems. Larimer 2007 conducted a review of the literature on individual‐focused prevention and treatment approaches for college drinking. Evidence was found in support of skills‐based interventions and motivational interventions that incorporated personalised feedback, with or without an in‐person intervention.

However, to our knowledge, the current review is the first examination of the MI literature as a Cochrane systematic review in relation to prevention of alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems in young people. If those involved with the prevention of alcohol misuse in young people are to implement MI in practice, clear evidence on its effectiveness is required.

Objectives

To assess the effects of motivational interviewing (MI) interventions for preventing alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems in young adults.

The specific objectives were:

to summarise current evidence about the effects of MI versus no intervention or a different intervention, for alcohol consumption and alcohol related problems in young adults;

to investigate whether the effects of MI are modified by the length of the intervention;

to investigate whether the effects of MI vary by type of control group, setting, and risk status.

We made the following comparison: MI versus no MI (assessment only or alternative intervention).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs in young adults receiving MIs for prevention of alcohol misuse and alcohol‐related problems compared with no intervention, assessment only or alternative interventions without MI components.

Types of participants

Young adults aged up to 25 years old. We were interested in the effectiveness of MI delivered as a universal strategy (i.e. with individuals regardless of level of risk) and as a targeted strategy (i.e. with individuals identified as being at higher risk).

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

MIs are defined as a one or more session approach including MI principles (adopting an empathic non‐judgemental stance, listening reflectively, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance and avoiding argument, supporting efficacy to change) as the core of the intervention as well as a feedback element or other non‐MI techniques.

Comparator intervention(s)

No intervention, assessment only.

Alternative interventions without MI components. Alternative interventions are, for example, self control training, skills‐based training, normative feedback, confrontational feedback, skills‐based counselling, 12‐step facilitation, brief feedback, risk reduction, relapse prevention and cognitive behaviour therapy.

In the main analyses, we group all comparator interventions together, but we ran subgroup comparisons to explore the effects of MI versus alternative interventions, on the one hand, and assessment only controls, on the other.

Types of outcome measures

We reported outcome measures separately according to an a priori categorisation of study follow‐up periods (short‐ versus longer‐term). We defined a short‐term follow‐up period for data collected less than four months after the intervention and longer‐term follow‐up for data collected from four months or more following the intervention. This distinction is consistent with previous work by White 2007, who pointed out that short‐term results (up to four months) should be regarded with caution. We agree and consider shorter‐term results to be less interesting and less reliable, as they provide little information about sustained effects of an intervention, and they are also more susceptible to reporting or publication bias than long‐term outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Alcohol use, misuse and problems: self reported or objective.

Typical self reported measurement scales are, for example, the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ), Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI), Alcohol Addiction Severity Index (AASI), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (S‐MAST) and the Short Alcohol Dependence Data Questionnaire (SADD). Self reported measures include:

quantity of alcohol consumed;

frequency of alcohol consumption;

binge drinking;

alcohol problems (alcohol abuse or dependence).

Objective measures of alcohol misuse are assessed by breath or blood alcohol test and include:

average blood alcohol content (BAC);

peak BAC.

Secondary outcomes

Drink‐driving; driving under the influence (DUI)

Alcohol‐related risky behaviour, e.g. violence, criminal activity, unintended or unprotected sexual behaviour, other drug use, alcohol‐related injuries

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 12); see Appendix 1.

MEDLINE (January 1966 to July 2015); see Appendix 2.

EMBASE (January 1988 to July 2015); see Appendix 3.

PsycINFO (1985 to July 2015); see Appendix 4.

To identify the studies included in this review, we developed a detailed search strategy for MEDLINE and then adapted it to each of the other databases to take into account differences in controlled vocabulary and syntax rules. There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the references of topic‐related systematic reviews and included studies in order to identify potentially relevant citations. Unpublished reports, abstracts, dissertations, brief and preliminary reports were eligible for inclusion. These were identified via handsearching of references of topic‐related systematic reviews and included studies. Some study authors were contacted to collect additional information for meta‐analysis, or to clarify whether papers reported separate studies.

In April 2016, we also undertook a search of the ClinicalTrials.gov registry and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors read all titles and abstracts resulting from the search and eliminated any obviously irrelevant studies (screening level 1). We obtained full copies of those remaining, which two authors then independently classified according to the inclusion criteria. We resolved differences of opinion through discussion and where required through involvement of a third reviewer. We used all available information for each study by consulting all companion publications.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted key information by using a standardised data extraction form, discussing and resolving any discrepancies and drawing in a third reviewer if required. We then entered information from data extraction into Review Manager (RevMan 2014). The data extraction form elicited information on study design, target population, reported outcomes, age, type of intervention and comparison, setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number eligible and recruited, risk of bias and relevant results.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed included studies.

We performed the 'Risk of bias' assessment for randomised controlled trials in this review using the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in a Cochrane Review is a two‐part tool addressing seven specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment (both related to selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other risk of bias. For 'other risk of bias' we considered unit of analysis issues. The first part of the tool allows for a description of what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgements, we adapted the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the addiction field. Where information was missing from studies we categorised risk of bias as unclear. We did not contact study authors for further information about risk of bias. See Appendix 5 for details.

Measures of treatment effect

A standardised mean difference (SMD) was appropriate for this review, as trials typically reported outcomes as scale scores. Where they reported standard deviations or odds ratios, we converted these into SMDs, also including the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used Hedges'g as the SMD effect size measure in the meta‐analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We assessed specific bias related to unit of analysis in a number of aspects: recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and comparability with individually randomised trials. When trials did not account for clustering in their results, or when appropriately analysed cluster trials reported statistics that were not amenable to meta‐analysis and individual level descriptive results were available, we planned to adjust their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in Higgins 2011a, using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial. Where the ICC information was not available, we excluded cluster trials as part of a sensitivity analysis.

Dealing with missing data

Where data (study descriptive results and statistics) were missing or incomplete we contacted study authors for additional information. If authors did not respond we were not able to include the study or an outcome from the study in the meta‐analysis. We made no attempt to impute missing data from studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed studies for clinical and methodological variability. We formally tested for statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test for statistical heterogeneity with a 10% level of significance as the cut‐off. We quantified the impact of any statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias is a significant threat to the validity of any systematic review. Such bias appears either when negative studies have lower likelihood of being published or if outcome data are selectively omitted from published reports because of their negative outcome. We constructed funnel plots for several of the primary outcomes where there was a reasonable number of trials.

Data synthesis

Where sufficient data were available across studies, we conducted meta‐analyses for overall effects using RevMan 5. As we expected intervention components, delivery, study samples and outcome measures to vary to a greater or lesser extent across studies, we used a random‐effects model, as is usual in studies of behavioural and preventive interventions. Where effect sizes or relevant results to allow calculation of effect sizes were not available for individual studies, we reported outcomes (for example significance levels) in a narrative way.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For both the outcomes reported at less than four months and those reported at four months or later, we analysed studies with assessment‐only controls separately from studies that had a control group that received an alternative intervention via subgroup analyses. We also undertook two further subgroup analyses for studies with longer‐term follow‐up, based on suggestions received from Mun 2015 on an earlier version of this review (). These were university or college settings versus other settings, and higher risk participants versus all or low‐risk participants. For all subgroup analyses, we report only the four self reported primary outcomes (quantity of alcohol consumed, frequency of alcohol consumption, binge drinking and alcohol problems).

We performed meta‐regression to examine the effect of intervention duration to assess the relationship between duration and effect size.

Sensitivity analysis

For studies where there was a high risk of selection bias, we carried out primary sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of inclusion or exclusion on the review findings. In secondary sensitivity analyses, we also removed studies that were at high risk for attrition and reporting bias from the meta‐analyses.

Summary of findings tables

We used the GRADE method to produce a 'Summary of findings' table for studies with longer‐term follow‐up (four months or more), as these are of more interest when considering the sustainability of intervention effects.

The Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) developed a system for grading the quality of evidence (GRADE 2004Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011) that takes into account issues not only related to internal validity but also to external validity, such as directness, consistency, imprecision of results and publication bias. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence.

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We lowered the grade for the following reasons.

Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study quality.

Important inconsistency (−1).

Some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness.

Imprecise or sparse data (−1).

High probability of reporting bias (−1)

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

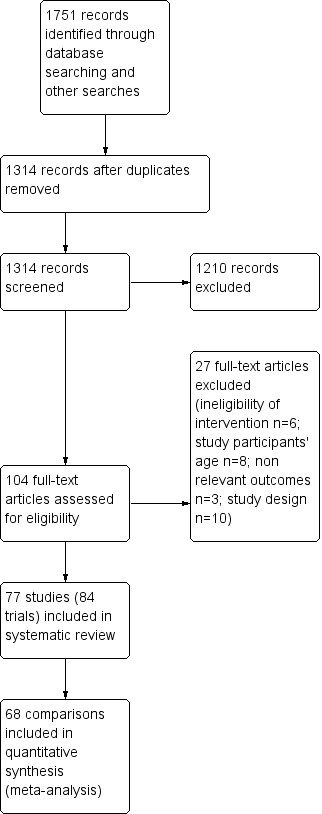

The electronic search yielded 1751 bibliographic records (1430 through MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO; 311 through the CENTRAL). We identified a further 10 studies through handsearching systematic reviews and contacting authors. The process of de‐duplication resulted in 1314 unique bibliographic records. After screening titles and abstracts,we excluded 1210 records that were obviously irrelevant. We examined 104 full‐text reports, excluding 27. This left 77 published and unpublished study reports that met our criteria for inclusion.

Seven study reports described two comparisons, so we included 84 comparisons in this systematic review. Four study reports described two randomised subgroups (Fromme 2004 MANDATED; Fromme 2004 VOLUNTARY; Murphy 2010a; Murphy 2010b; Terlecki 2011 MANDATED; Terlecki 2011 VOLUNTARY; Terlecki 2010 MANDATED; Terlecki 2010 VOLUNTARY; Terlecki 2011 MANDATED; Terlecki 2011 VOLUNTARY), and three study reports only described analyses for two predefined subgroups (Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Walters 2009 MIF v FBO; Walters 2009 MIO v AO). Throughout this review we refer to each comparison as a 'trial', even if only one report reported two or more comparisons.

We present the study flow diagram of records identified from the search in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We identified a further 12 trials for future classification and 1 ongoing study from the trial registry searches.

Included studies

See the Characteristics of included studies table. Total participants numbered 22,872. The unit of randomisation in 80 trials was the individual; four were cluster‐randomised (Larimer 2001; McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2011; Wilke 2014). The total number of participants in cluster‐randomised trials was 1766, ranging from 159 in Larimer 2001 to 991 in Wilke 2014. McCambridge 2008 randomised by individual but adjusted for cluster effects associated with recruitment.

Country: Sixty‐six trials took place in the United States, four in the UK (Marsden 2006; McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2008; McCambridge 2011), one in Australia (Bailey 2004), six in Switzerland (Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2014; Gmel 2013), one in Spain (Goti 2010), one in France (Gomez 2013), two in Brazil (Christoff 2015; Segatto 2010), one in Thailand (Rongklavit 2013), one in Holland (Thush 2009), and one in Canada and the United States (Fleming 2010).

Participant characteristics: Study participants’ average age ranged from 15 in Bailey 2004 to 24 in Christoff 2015. Five studies did not report the age of participants (Cimini 2009; Marlatt 1998; Palmer 2004; White 2007; Wilke 2014). The proportion of males ranged from 22% in Feldstein 2007 to 90% in Stein 2006. Four trials enrolled only female students (Ceperich 2011; Clinton‐Sherrod 2011; LaBrie 2008; LaBrie 2009), and seven only recruited males (Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2014; Gmel 2013; Larimer 2001).

Ethnicity of participants was mixed, with the majority (n = 52) of studies in largely (> 60%) white participants. In two studies participants were mainly (> 50%) Latino (D'Amico 2008; Aubrey 1998). In 13 other studies, fewer than 60% of participants were white (Bernstein 2010; Clair 2013; Juarez 2006; McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2008; McCambridge 2011; Murphy 2012a; Naar‐King 2006; Schmiege 2009; Steele Seel 2010; Stein 2006; Stein 2011; Walton 2010), and in one of these, participants were 88% African American (Naar‐King 2006). Sixteen studies did not report ethnicity (Bailey 2004; Barnett 2010; Christoff 2015; D'Amico 2013; Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2014; Gmel 2013; Gomez 2013; Goti 2010; Marlatt 1998; Rongklavit 2013; Thush 2009; Wilke 2014).

Most trials (70/84) reported that participants were assessed as being at higher risk for alcohol use or misuse because they were over a screening test threshold score, presented with evidence of alcohol misuse or had an associated risk factor (e.g. delinquency or other social or health conditions). We present details of risk characteristics, participants and setting for each study in the Characteristics of included studies. Fourteen studies did not restrict participants to those at higher risk (Carey 2006; D'Amico 2008; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Dermen 2011; Ewing 2009; Fromme 2004 VOLUNTARY; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gmel 2013; Larimer 2001; McCambridge 2011; Michael 2006; Naar‐King 2006; Wagener 2012; Wood 2010). A subgroup analysis assesses findings according to baseline risk status.

Setting: Settings for the trials varied; 51 of the 84 studies took place in higher education settings (university or colleges), mostly in the United States but also in one Brazilian and one Canadian study. Three UK trials and one Dutch trial took place at other post‐secondary educational institutions catering to pre‐university or vocational students (McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2008; McCambridge 2011; Thush 2009). Fourteen trials took place in healthcare settings: hospital emergency departments (Barnett 2010; Bernstein 2010; Monti 1999; Monti 2007; Segatto 2010; Spirito 2004; Walton 2010), an outpatient substance abuse or psychiatry department (Goti 2010; Aubrey 1998), a community‐based healthcare clinic (D'Amico 2008; Nirenberg 2013), and an HIV centre (Murphy 2012a; Naar‐King 2006; Rongklavit 2013). Other settings were as follows: a youth centre in Australia (Bailey 2004); local companies (Doumas 2008), a vocational training centre (Steele Seel 2010), army recruitment setting (Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2014; Gmel 2013), UK drug agencies (Marsden 2006), a youth court (D'Amico 2013), and juvenile detention centres (Clair 2013; Schmiege 2009; Stein 2006; Stein 2011). In the non‐college studies, the ethnicity balance was slightly different, with a lower proportion of whites.

Intervention: in 65 of the trials the intervention consisted only of an individual MI session. In one study participants attended both an individual session and a group session (Larimer 2001); in another study there were four group sessions and one individual session (Nirenberg 2013); in six studies there were two individual sessions (Clair 2013; Dermen 2011; Fleming 2010; Schaus 2009; White 2007; Wood 2010); and in four there were four sessions (Aubrey 1998; Murphy 2012a; Naar‐King 2006; Steele Seel 2010). Three studies used a single group session (LaBrie 2008; Michael 2006; Walters 2000), one used four group sessions (Bailey 2004), and another used six group sessions (D'Amico 2013). The duration of sessions varied: in 57 trials sessions took one hour or less; the shortest was a single 10 to 15 minute intervention (Wilke 2014), and the longest had five MI sessions over a 19‐hour period (Nirenberg 2013). One study reported a 'brief' intervention without specifying a duration (Barnett 2007), and six studies did not specify any information at all about session duration (Amaro 2009; Clinton‐Sherrod 2011; Marlatt 1998; Monti 1999; Steele Seel 2010; White 2007).

Comparisons: Forty‐nine trials compared MI versus an assessment‐only control group. Twenty‐five trials compared MI to alcohol counselling, education or information only (Amaro 2009; Barnett 2007; Bernstein 2010; Borsari 2005; Carey 2009; Carey 2013a; Ceperich 2011; Cimini 2009; D'Amico 2008; Ewing 2009; Faris 2005; Gomez 2013; LaBrie 2008; Marsden 2006; Martens 2013; McCambridge 2008; McCambridge 2011; Murphy 2010a; Rongklavit 2013; Schaus 2009; Schmiege 2009; Segatto 2010; Thush 2009; Walton 2010; Wilke 2014). Seven trials compared MI with feedback only (Barnett 2010; Christoff 2015; Doumas 2011; Monti 2007; Murphy 2004; Walters 2009 MIF v FBO; White 2007). Clair 2013, Stein 2006 and Stein 2011 compared MI with relaxation, while D'Amico 2013 compared MI with a six‐session Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) abstinence programme.

Outcomes: The alcohol‐related outcomes differed across the trials, as detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table. Many different outcome measures were used. The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) was mostly used to measure alcohol‐related problems (White 1989); investigators measured quantity, frequency, BAC and binge drinking using various instruments, the most common of which were the Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT) (Saunders 1993), versions of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) (Collins1985), and the Timeline Followback (TLFB) technique (Sobell 1992).

The longest time points at which investigators measured the outcomes ranged from one month in Doumas 2008, Ewing 2009, Faris 2005, Goti 2010, Kulesza 2010, Martens 2013, Murphy 2010a, Murphy 2010b to four years postrandomisation in Marlatt 1998.

Excluded studies

We excluded many studies at screening because they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 27 studies required close scrutiny before we excluded them on the basis that they did not meet the inclusion criteria: ineligibility of intervention (N = 6, not MI), study participants’ age (N = 8, age > 25 years), outcomes (N = 3, no relevant outcomes), study design (N = 5, no control group; N = 6, reviews not trials; N = 6, non‐randomised study). We describe these excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

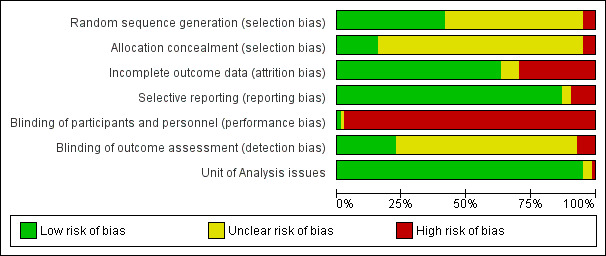

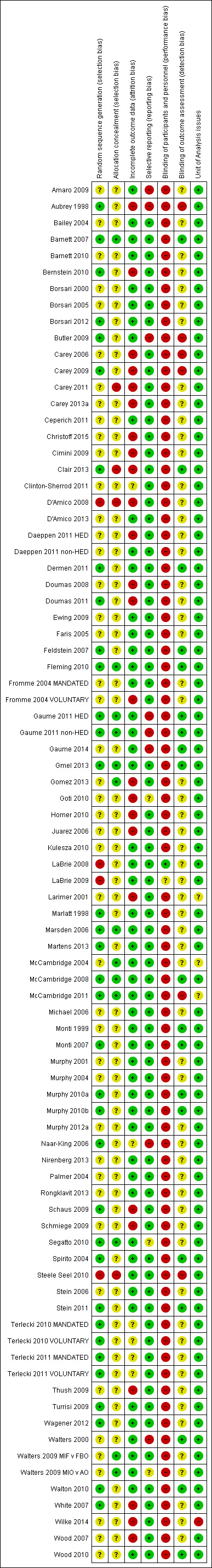

We present the risk of bias assessment results for the included trials in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about risk of bias domains for each included study.

Allocation

Thirty‐five trials reported an adequate method of randomisation, and 13 described proper allocation concealment. In one study, we deemed that cluster randomisation had failed (McCambridge 2004).

Blinding

No study adequately blinded study participants and therapists. Fleming 2010 attempted to blind participants and therapists but only in the control condition, so this was a limited attempt with doubtful impact on performance bias. Investigators attempted blinding of outcome assessment in 21 studies (Barnett 2007; Clair 2013; Dermen 2011; Feldstein 2007; Fleming 2010; Daeppen 2011 HED; Daeppen 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2011 HED; Gaume 2011 non‐HED; Gaume 2014; Gmel 2013; McCambridge 2008; Monti 1999; Monti 2007; Murphy 2010a; Murphy 2010b; Spirito 2004; Stein 2011; Walters 2000; Walton 2010; Wood 2010); in the other trials this was either not the case or not explicitly reported.

Incomplete outcome data

The attrition rate (at final follow‐up) in 54 trials was acceptable (20% or less), and for 25 trials it was not acceptable (> 20%). Five trials did not provide sufficiently clear information to adequately assess attrition (Naar‐King 2006; Terlecki 2010 MANDATED; Terlecki 2010 VOLUNTARY; Terlecki 2011 MANDATED; Terlecki 2011 VOLUNTARY). Five trials reported no losses to follow‐up (Bailey 2004; Clinton‐Sherrod 2011; Juarez 2006; Michael 2006; Steele Seel 2010).

Selective reporting

Most trials (73/84) were free of selective outcome reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

Three cluster‐randomised trials reported at least some efforts to adjust for the cluster level effect, but they provided insufficient details for inclusion of cluster‐adjusted estimates in the meta‐analysis (Larimer 2001; McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2011). One cluster trial did not adjust for clustering and also did not report information about ICC (Wilke 2014). Therefore, we removed all four studies in the sensitivity analysis.

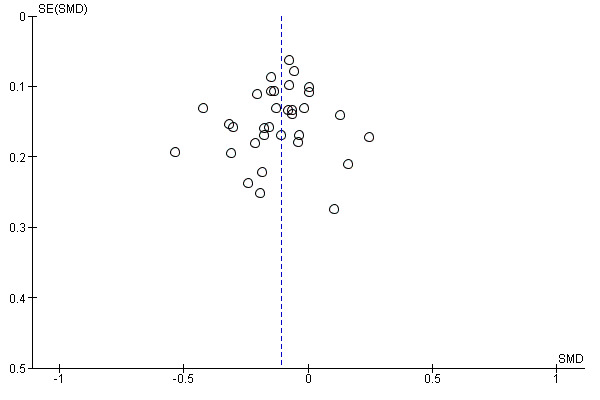

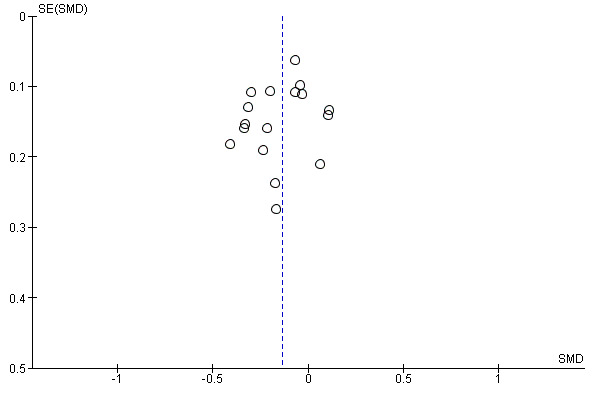

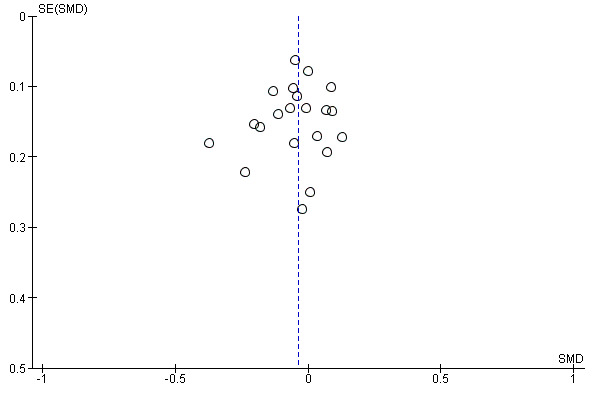

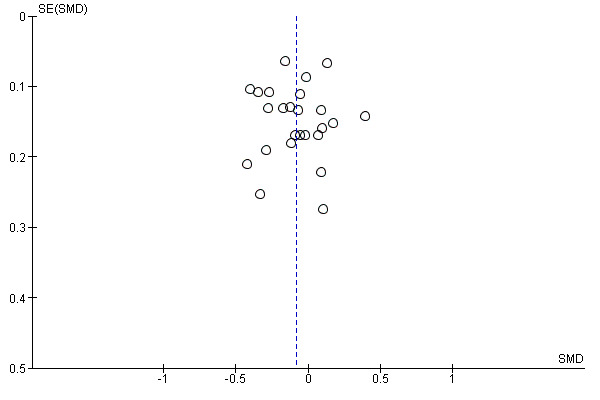

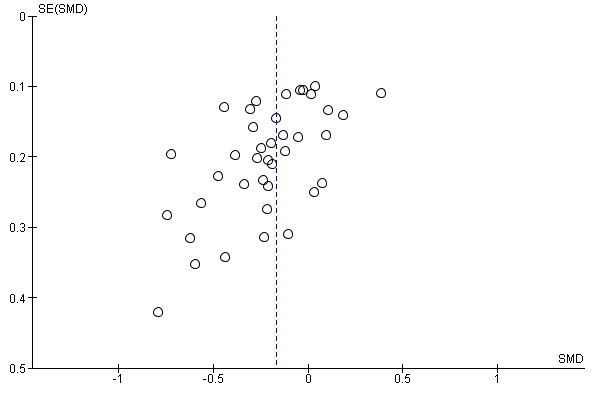

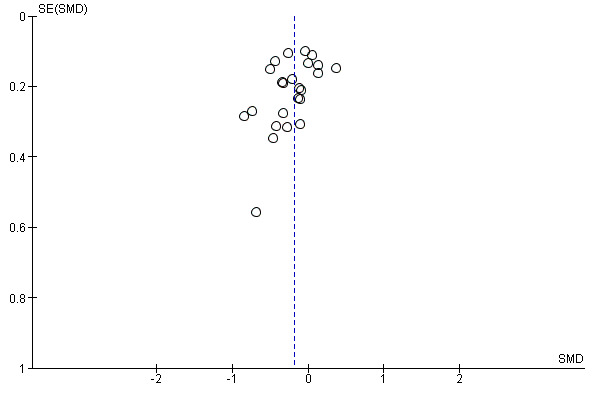

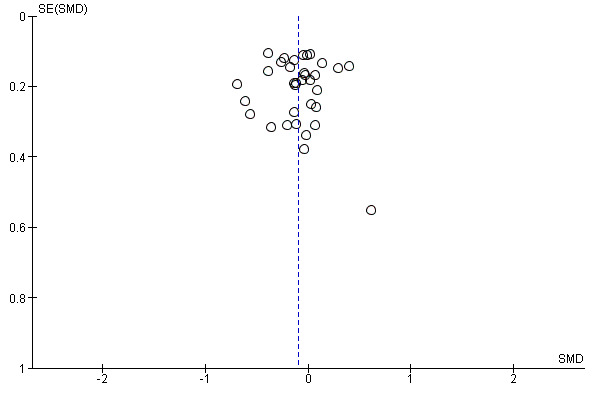

To assess possible publication bias, we constructed funnel plots for several of the primary outcomes where there were a reasonable number of trials, for both longer‐term and shorter‐term outcomes, and we visually inspected the plots. In all plots, a negative SMD indicates an effect in favour of the MI intervention. With longer‐term outcomes, there appeared to be reasonable symmetry and no notable outliers (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 1.1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 1.2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 1.3 Binge drinking.

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 1.4 Alcohol problems.

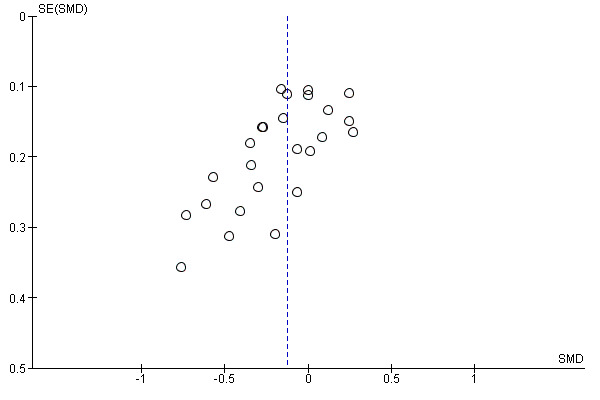

With shorter‐term outcomes (Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10; Figure 11), one plot had a notable outlier: Steele Seel 2010, a very small study (N = 14) with no significant effect (Figure 11). Two plots showed marked asymmetry (Figure 8; Figure 10). Several studies contributed notably to the asymmetry in Figure 8: Aubrey 1998, Bailey 2004, Butler 2009, D'Amico 2008, Juarez 2006, and Terlecki 2010 MANDATED, ; and Figure 10: Bailey 2004, Borsari 2000, Butler 2009, D'Amico 2008, Feldstein 2007, Murphy 2001, Murphy 2010a, and Murphy 2010b.

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 2.1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

9.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 2.2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

10.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 2.3 Binge drinking.

11.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, outcome: 2.4 Alcohol problems.

This suggests that there may be a risk of publication bias in the shorter‐term outcome results, but it is also possible that other factors contributed, for example the poorer study quality in smaller studies, or the inclusion of studies with different sizes having participants with different risk profiles. It is interesting to note that asymmetry and the risk of publication bias was more of an issue for the shorter‐term follow‐up analyses.

Effects of interventions

We included 68 of the 84 included trials (81%) in the meta‐analysis. We contacted some authors who then provided additional information to enable their trials to be included in the meta‐analysis. The remaining 16 did not report results in a format that allowed inclusion in the meta‐analysis, and authors did not respond to requests for further information in time for inclusion in this review (Amaro 2009; Cimini 2009; Clair 2013; Clinton‐Sherrod 2011; Ewing 2009; Goti 2010; Horner 2010; LaBrie 2008; LaBrie 2009; Murphy 2004; Murphy 2012a; Naar‐King 2006; Palmer 2004; Thush 2009; Wood 2007; Wood 2010).

We summarise eight alcohol use and misuse outcomes below, categorised according to two follow‐up periods: four or more months (see Table 1), and less than four months (see Table 2). We summarise the quality of the evidence in both these tables according to GRADE criteria. Where trials reported several follow‐up points, we took the closest ones to 12‐month follow‐up (for longer‐term outcomes) or 3‐month follow‐up (for shorter‐term outcomes). For example, in a study with one‐year and two‐year outcomes, we used the one‐year results in the analysis on longer‐term outcomes.

The eight outcomes were as follows.

Quantity of alcohol consumed.

Frequency of alcohol consumed.

Binge drinking.

Alcohol problems.

Average blood alcohol concentration (BAC), calculated using a formula based on consumption, sex and weight.

Peak BAC, calculated using a formula based on consumption, sex and weight.

Drink‐driving.

Risky behaviour.

For the first four key outcome measures (drinking quantity, drinking frequency, binge drinking, and alcohol related problems) there were sufficient studies to conduct subgroup analyses.

During primary sensitivity analyses, we selectively removed all studies that were at high risk for selection bias (Carey 2011; D'Amico 2008; Steele Seel 2010). Carey 2013a presented results as change scores, and the author did not send means and standard deviations at follow‐up time points in time for inclusion in this review. Technically, direct comparison and pooling of final value and change scores is not straightforward when using standardised mean differences, since the difference in standard deviation reflects not differences in measurement scale, but differences in the reliability of the measurements. Therefore we also selectively removed Carey 2013a from the analysis as part of the sensitivity analysis. We also removed four cluster trialsduring the sensitivity analysis as there is a risk of inflated effects if clustering is not adequately accounted for in the analysis (Larimer 2001; McCambridge 2004; McCambridge 2011; Wilke 2014).

In secondary sensitivity analyses, we also removed studies that were high risk for attrition and reporting bias from the meta‐analyses (see Figure 3).

1. MI versus no MI (assessment only or alternative intervention) at four months or more of follow‐up

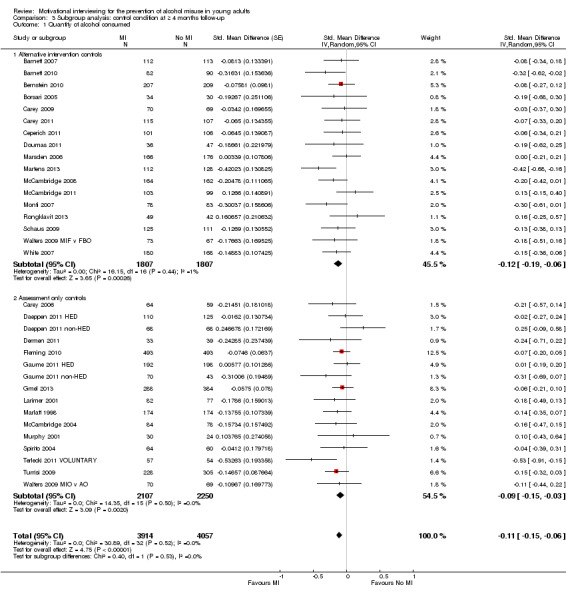

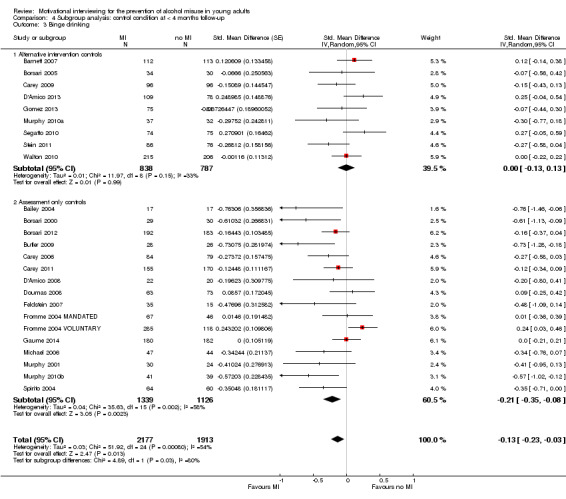

1.1 Quantity of alcohol consumed

See: Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

Thirty‐three studies with 7971 participants reported measures of alcohol consumption at follow‐up periods of four months or more and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was an effect in favour of MI (SMD −0.11, 95% CI −0.15 to −0.06) representing a decrease of 1.2 drinks consumed each week (95% CI 0.7 to 1.6), from an average of 13.7 drinks per week to 12.5 drinks per week, based on a standard deviation (SD) of 10.8 (Martens 2013). Heterogeneity was not a problem (I2 = 0%, P = 0.52).

In the primary sensitivity analysis, the pooled effect estimate was unchanged. Similarly, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimate in the more rigorous secondary sensitivity analysis.

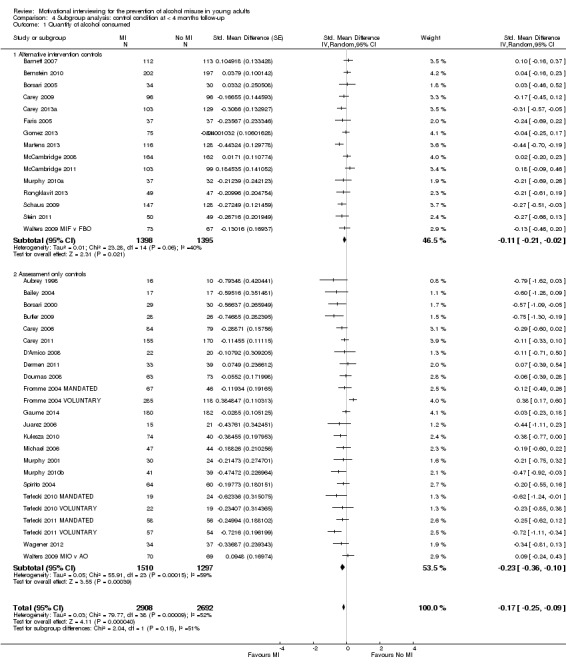

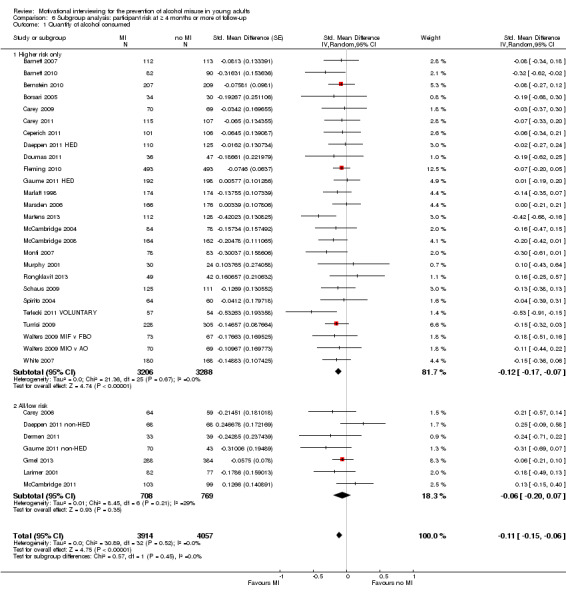

1.2 Frequency of alcohol consumption

See: Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

Seventeen studies with 4377 participants reported on frequency of alcohol consumption at follow‐up periods of four or more months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a difference in favour of MI (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.21 to −0.07) representing a decrease of 0.22 drinking days per week (95% CI 0.11 to 0.32), from an average of 2.74 drinking days per week to 2.52 drinking days per week, based on Martens 2013. Heterogeneity was not a problem (I2 = 24%, P = 0.18).

In the primary sensitivity analysis, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect. There were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimate in the more rigorous secondary sensitivity analysis, with one study removed.

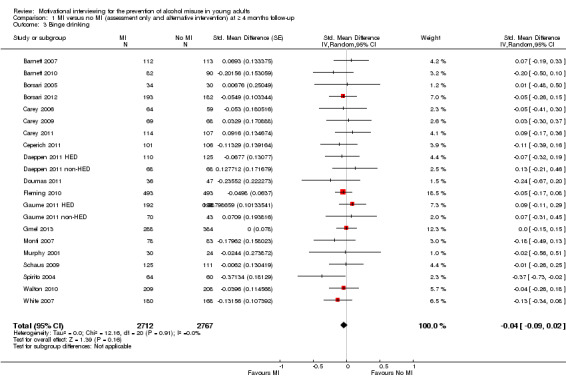

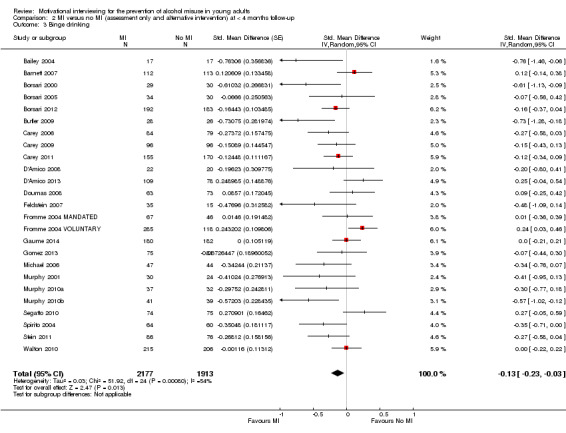

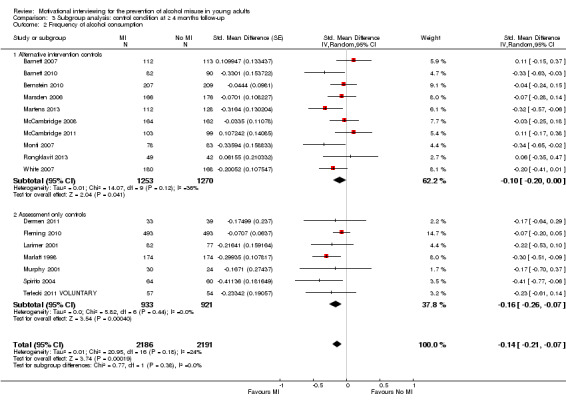

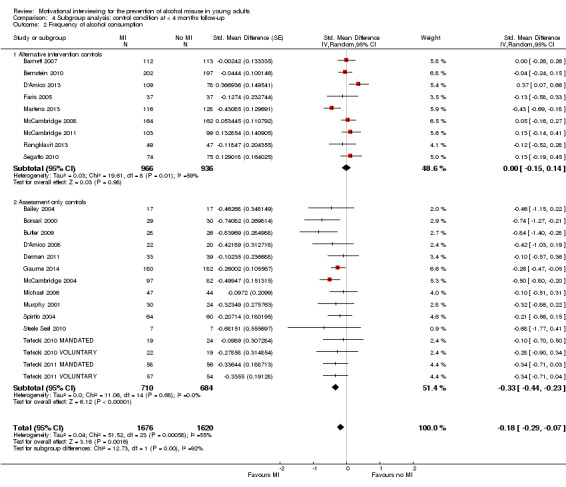

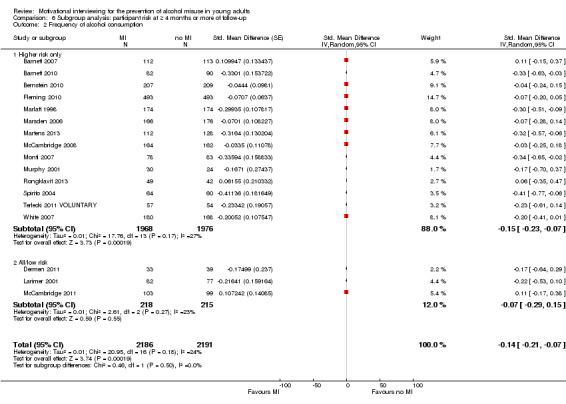

1.3 Binge drinking

See: Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

Twenty‐one studies with 5479 participants reported on the frequency of alcohol consumption at follow‐up periods of four months and more and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was no clear effect of the MI intervention on binge drinking (SMD −0.04, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.02). A test for heterogeneity showed no significant variability between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.91).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

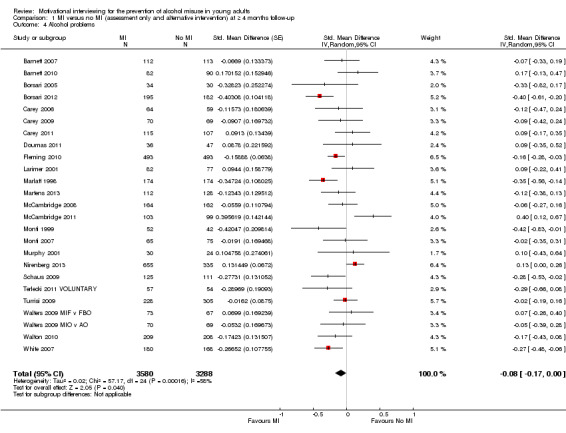

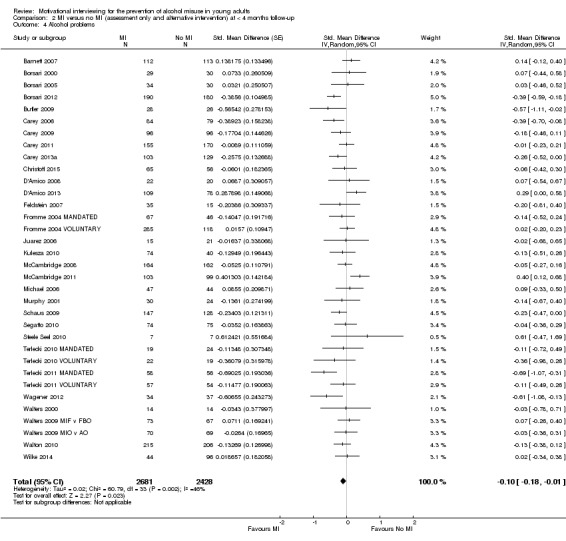

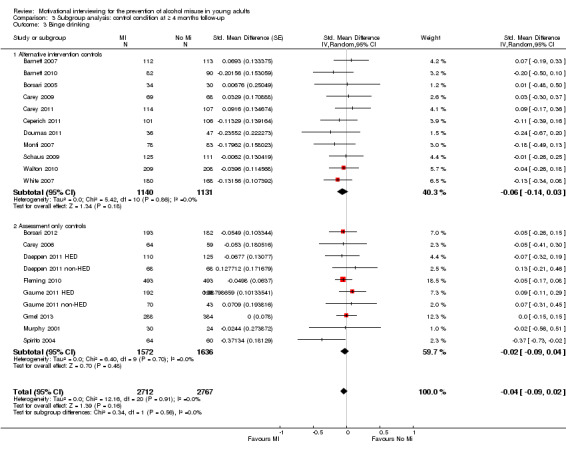

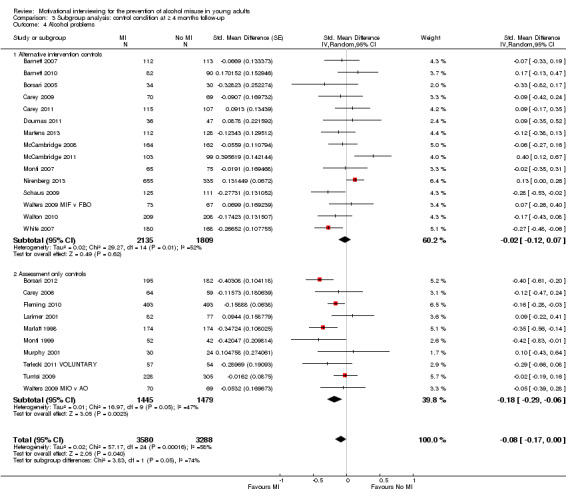

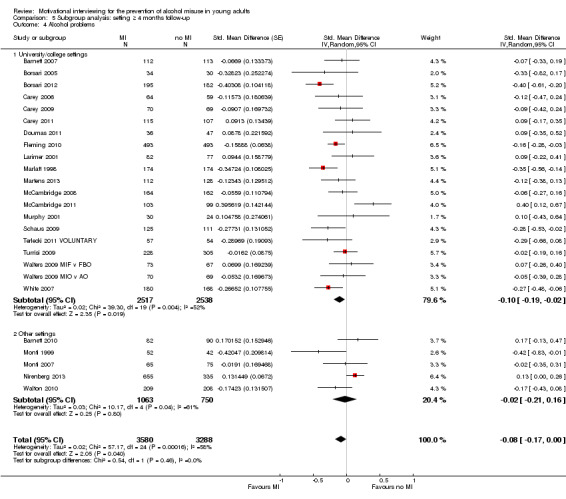

1.4 Alcohol problems

See: Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

Twenty‐five studies with 6868 participants reported on alcohol problems at follow‐up periods of four or more months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a borderline effect (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.00), representing a decrease of 0.73 on the alcohol problems scale score (95% CI 0.00 to 1.56), from an average of 8.91 to 8.18, based on Martens 2013. A test for heterogeneity showed significant variability across studies (I2 = 58%, P = 0.0002).

In the primary sensitivity analysis, the strength of the effect increased (SMD −0.12, 95% CI −0.20 to −0.04), but we did not find any other change in the secondary sensitivity analysis.

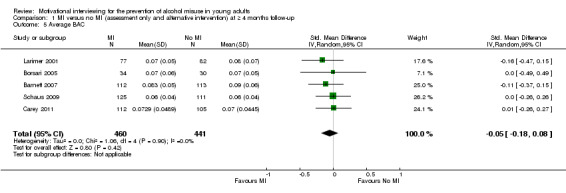

1.5 Average BAC

See: Analysis 1.5.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 5 Average BAC.

Five studies with 901 participants reported average BAC at four or more months follow‐up and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was no difference between groups (SMD −0.05, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.08). A test for heterogeneity showed no variability between studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.90).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

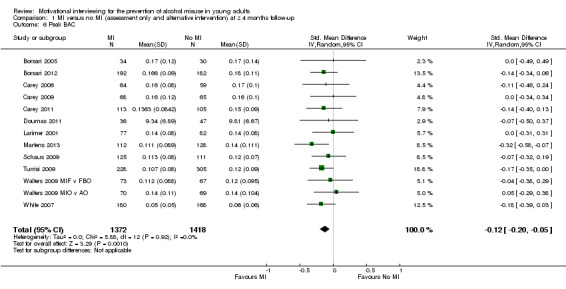

1.6 Peak BAC

See: Analysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 6 Peak BAC.

Thirteen studies with 2790 participants reported peak BAC at four or more months follow‐up and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a difference between groups (SMD −0.12, 95% CI −0.20 to −0.05), representing a decrease of 0.013% for peak BAC (95% CI 0.006 to 0.025), from an average of 0.144% to 0.131%, based on Martens 2013. A test for heterogeneity showed no significant variability across studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.92).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

1.7 Drink‐driving

See: Analysis 1.7

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 7 Drink‐driving.

Four studies with 1205 participants reported on drink‐driving at four or more months follow‐up and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was no effect for MI (SMD −0.13, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.10). A test for heterogeneity showed significant variability across studies (I2 = 61%, P = 0.05).

No primary or secondary sensitivity analyses were undertaken, as no studies were eligible for removal.

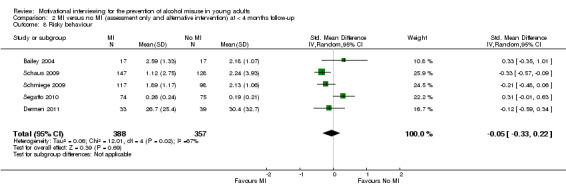

1.8 Risky behaviour

This outcome combined various activities, from unspecified risky behaviour to alcohol‐related injury and unprotected sex. See: Analysis 1.8.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 8 Risky behaviour.

Seven studies with 1579 participants reported on risky behaviour at four or more months follow‐up. All studies were included in the meta‐analysis, which showed no effect for MI (SMD −0.15, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.01). A test for heterogeneity showed a significant effect (I2 = 47%, P = 0.08).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

2. MI versus no MI (assessment only or alternative intervention) at less than four months of follow‐up

2.1 Quantity of alcohol consumed

See: Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

Thirty‐nine studies (5600 participants) reported on quantity of drinking at less than four month follow‐up and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was an effect in favour of MI (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.25 to −0.09). Heterogeneity (I2 = 52%) was statistically significant at P<0.0001.

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

2.2 Frequency of alcohol consumption

See: Analysis 2.2.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

Twenty‐four studies with 3296 participants reported on frequency of alcohol consumption at follow‐up periods of less than four months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a difference in favour of MI (SMD −0.18, 95% CI −0.29 to −0.07). Heterogeneity was problematic (I2 = 55%, P = 0.0006).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

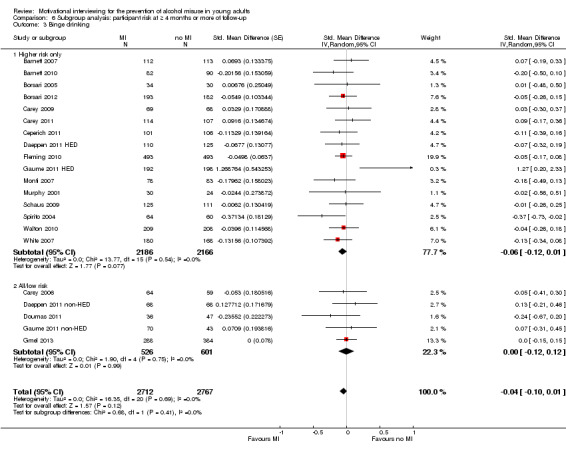

2.3 Binge drinking

See: Analysis 2.3.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

Twenty‐five studies with 4090 participants reported a binge drinking measure at follow‐up periods of less than four months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a difference in favour of MI (SMD −0.13, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.03). A test for heterogeneity showed a significant variability between studies (I2 = 54%, P = 0.0008).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

2.4 Alcohol problems

See: Analysis 2.4.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

Thirty‐four studies with 5109 participants reported a measure of alcohol problems at follow‐up periods of less than four months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was a marginal effect of MI over comparison or controls (SMD −0.10, 95% CI −0.18 to −0.01). A test for heterogeneity showed significant variability across studies (I2 = 46%, P = 0.002).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

2.5 Average BAC

See: Analysis 2.5.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 5 Average BAC.

Six studies with 1096 participants were suitable for inclusion in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was no effect of the intervention (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.01). Heterogeneity was not a problem (I2 = 34%, P = 0.18).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

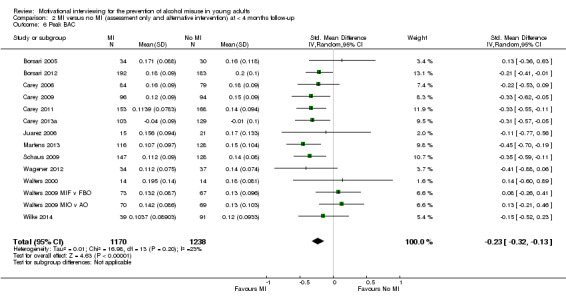

2.6 Peak BAC

See: Analysis 2.6.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 6 Peak BAC.

Fourteen studies with 2408 participants reported on peak BAC at follow‐up periods of up to three months and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was an effect in favour of the intervention (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.13). A test for heterogeneity found no variability across pooled studies (I2 = 23%, P = 0.20).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

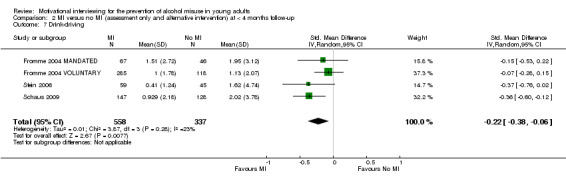

2.7 Drink‐driving

See: Analysis 2.7.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 7 Drink‐driving.

Four studies with 895 participants were suitable for inclusion in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was an effect of the intervention (SMD −0.22, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.06). Heterogeneity was not a problem (I2 = 23%, P = 0.28).

No primary sensitivity analysis was undertaken as there were no eligible studies. Removal of two studies in the secondary sensitivity analysis shifted the effect estimate (SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.02).

2.8 Risky behaviour

See: Analysis 2.8.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MI versus no MI (assessment only and alternative intervention) at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 8 Risky behaviour.

Five studies with 745 participants reported on risky behaviour at less than four months follow‐up and were included in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis. There was no effect of MI (SMD −0.05, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.22). A test for heterogeneity showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 67%, P = 0.02).

In both the primary and secondary sensitivity analyses, there were no substantive changes to the pooled effect estimates.

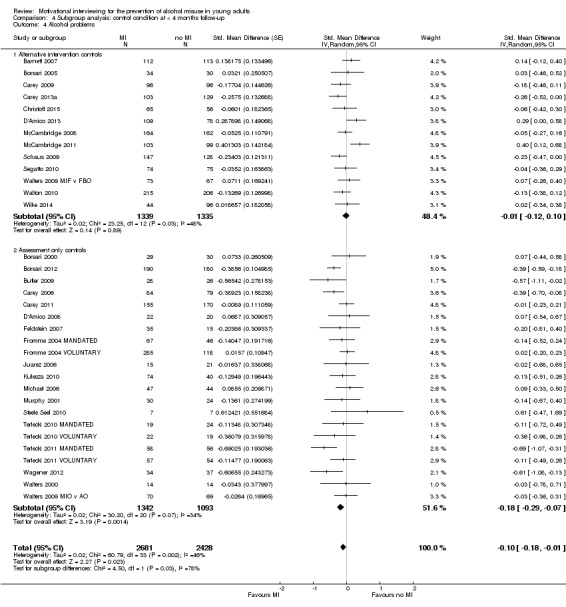

3. Subgroup analysis: control condition at four months or more of follow‐up

See Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: control condition at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: control condition at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: control condition at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: control condition at ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

We analysed studies with assessment‐only controls separately from studies that had a control group that received an alternative intervention. There was no clearly discernible subgroup effect (using a P value of 0.05 to establish significance) for any of the outcomes considered (Table 3). Alcohol problems showed a borderline effect (P = 0.05), but given the number of tests and increased risk of chance findings, we have been cautious in interpretation.

1. Subgroup analysis, MI versus active control versus assessment only.

| Follow‐up | Outcome | SMD (95% CI), Active controls | SMD (95% CI), assessment only | Test for group differences |

| ≥ 4 months | Quantity of drinking | −0.12 (−0.19 to −0.06) | −0.11 (−0.15 to −0.03) | Chi2 = 0.40, df = 1 (P = 0.53) |

| Frequency of drinking | −0.10 (−0.20 to 0.00) | −0.14 (−0.21 to −0.07) | Chi2 = 0.77, df = 1 (P = 0.38) | |

| Binge drinking | −0.06 (−0.14 to 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.09 to 0.02) | Chi2 = 0.34, df = 1 (P = 0.56) | |

| Alcohol problems | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.07) | −0.18 (−0.29 to −0.06) | Chi2 = 3.83, df = 1 (P = 0.05) | |

| < 4 months | Quantity of drinking | −0.11 (−0.21 to −0.02) | −0.23 (−0.36 to −0.10) | Chi2 = 1.62, df = 1 (P = 0.20) |

| Frequency of drinking | 0.00 (−0.15 to 0.14) | −0.33 (−0.44 to −0.23) | Chi2 = 12.73, df = 1 (P = 0.0004) | |

| Binge drinking | 0.00 (−0.13 to 0.13) | −0.21 (−0.35 to −0.08) | Chi2 = 4.62, df = 1 (P = 0.03) | |

| Alcohol problems | −0.01 (−0.12 to 0.10) | −0.18 (−0.29 to −0.07) | Chi2 = 4.50, df = 1 (P = 0.03) |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; SMD: standardised mean difference.

4. Subgroup analysis: control condition at less than four months of follow‐up

See Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: control condition at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: control condition at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: control condition at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup analysis: control condition at < 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

In this subgroup analysis, there was a clear effect for three of the four outcomes. Pooled effects were clearly larger in the assessment only subgroup compared with the alternative intervention subgroup except for quantity of drinking (analysis 4.1 in Table 3).

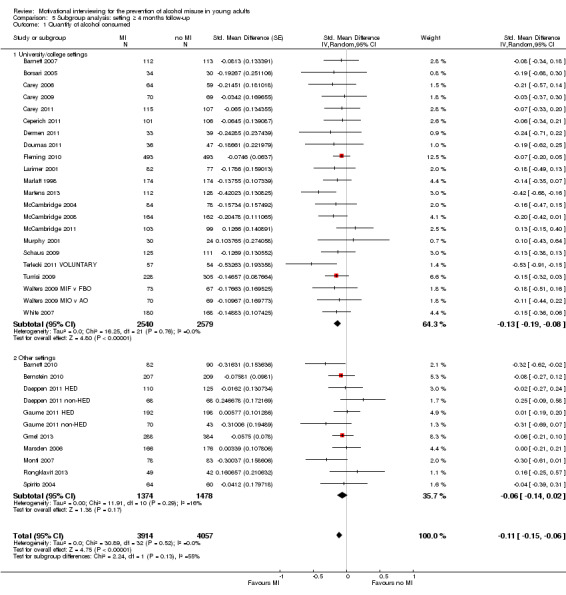

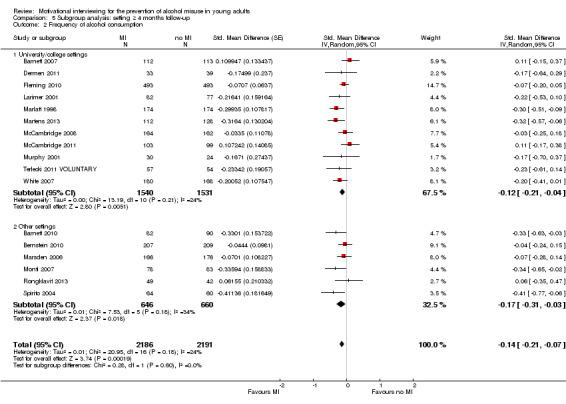

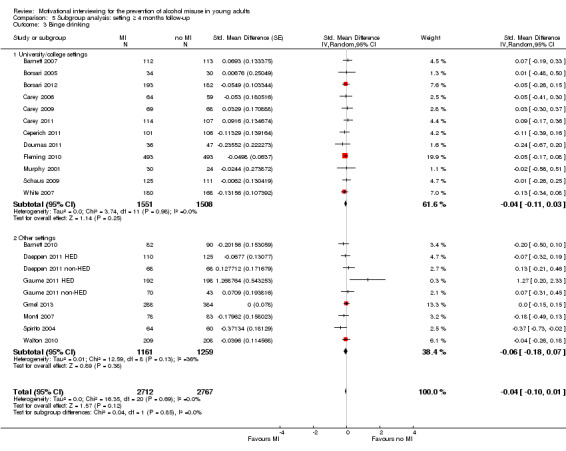

5. Subgroup analysis: setting at four months or more of follow‐up

See Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: setting ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: setting ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: setting ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup analysis: setting ≥ 4 months follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

We ran a separate subgroup analysis on studies with participants from university or college settings and studies that had participants from other settings. There was no discernible subgroup effect for any of the outcomes considered (Table 4).

2. Subgroup analysis, university/college settings versus other settings.

| Follow‐up | Outcome | SMD (95% CI), university/college | SMD (95% CI), other settings | Test for group differences |

| ≥ 4 months | Quantity of drinking | −0.13 (−0.19 to −0.08) | −0.06 (−0.14 to 0.02) | Chi2 = 2.24, df = 1 (P = 0.13) |

| Frequency of drinking | −0.12 (−0.21 to −0.04) | −0.17 (−0.31 to −0.03) | Chi2 = 0.28, df = 1 (P = 0.60) | |

| Binge drinking | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.03) | −0.06 (−0.18 to 0.07) | Chi2 = 0.04, df = 1 (P = 0.85) | |

| Alcohol problems | −0.10 (−0.19 to −0.02) | −0.02 (−0.21 to 0.16) | Chi2 = 0.54, df = 1 (P = 0.46) |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; SMD: standardised mean difference.

6. Subgroup analysis: participant risk at four months or more of follow‐up

See Analysis 6.1; Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3; Analysis 6.4.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis: participant risk at ≥ 4 months or more of follow‐up, Outcome 1 Quantity of alcohol consumed.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis: participant risk at ≥ 4 months or more of follow‐up, Outcome 2 Frequency of alcohol consumption.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis: participant risk at ≥ 4 months or more of follow‐up, Outcome 3 Binge drinking.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup analysis: participant risk at ≥ 4 months or more of follow‐up, Outcome 4 Alcohol problems.

We ran a subgroup analysis on studies with participants at higher baseline risk of alcohol use or misuse versus studies that had participants who were not screened for risk or were assessed to be at lower risk. There was no discernible subgroup effect for any of the outcomes considered (Table 5).

3. Subgroup analysis, higher risk participants versus all or low risk participants.

| Follow‐up | Outcome | SMD (95% CI), high risk | SMD (95% CI), all/low risk | Test for group differences |

| ≥ 4 months | Quantity of drinking | −0.12 (−0.17 to −0.07) | −0.06 (−0.20 to 0.07) | Chi2 = 0.01, df = 1 (P = 0.94) |

| Frequency of drinking | −0.15 (−0.23 to −0.07) | −0.07 (−0.29 to 0.15) | Chi2 = 0.23, df = 1 (P = 0.63) | |

| Binge drinking | −0.06 (−0.12 to 0.01) | 0.00 (−0.12 to 0.12) | Chi2 = 0.68, df = 1 (P = 0.41) | |

| Alcohol problems | −0.11 (−0.19 to −0.03) | 0.14 (−0.15 to 0.43) | Chi2 = 0.86, df = 1 (P = 0.35) |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; SMD: standardised mean difference.

Meta‐regression