Abstract

Context:

It is not known whether the magnitude of metabolic adaptation, a greater than expected drop in energy expenditure, depends on the type of bariatric surgery and is associated with cardiometabolic improvements.

Objective:

To compare changes in energy expenditure (metabolic chamber) and circulating cardiometabolic markers 8 weeks and 1 year after Roux-en-y bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB), or a low-calorie diet (LCD).

Design, Setting, Participants, and Intervention:

This was a parallel-arm, prospective observational study of 30 individuals (27 females; mean age, 46 ± 2 years; body mass index, 47.2 ± 1.5 kg/m2) either self-selecting bariatric surgery (five RYGB, nine SG, seven LAGB) or on a LCD (n = 9) intervention (800 kcal/d for 8 weeks, followed by weight maintenance).

Results:

After 1 year, the RYGB and SG groups had similar degrees of body weight loss (33–36%), whereas the LAGB and LCD groups had 16 and 4% weight loss, respectively. After adjusting for changes in body composition, 24-hour energy expenditure was significantly decreased in all treatment groups at 8 weeks (−254 to −82 kcal/d), a drop that only persisted in RYGB (−124 ± 42 kcal/d; P = .002) and SG (−155 ± 118 kcal/d; P = .02) groups at 1 year. The degree of metabolic adaptation (24-hour and sleeping energy expenditure) was not significantly different between the treatment groups at either time-point. Plasma high-density lipoprotein and total and high molecular weight adiponectin were increased, and triglycerides and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were reduced 1 year after RYGB or SG.

Conclusions:

Metabolic adaptation of approximately 150 kcal/d occurs after RYGB and SG surgery. Future studies are required to examine whether these effects remain beyond 1 year.

Obesity remains a global epidemic with few successful treatment options and even fewer treatments able to effectively target obesity and its comorbidities. With more than 450 000 bariatric operations performed worldwide each year (1), bariatric surgery is an increasingly popular treatment for morbid obesity, resulting in substantial and mostly durable weight loss and improvement in cardiometabolic health (2). However, despite the well-described metabolic benefits of bariatric surgical procedures, the underlying mechanisms leading to such improvements remain unclear and are an area of intense investigation.

Examining energy metabolism in patients after bariatric surgery will elucidate whether a relative hypermetabolism is a mechanism contributing to sustained weight loss or alternatively whether the large weight losses induce a hypometabolic situation that may contribute to weight regain. On this latter point, there is evidence to suggest that metabolic adaptation, a drop in energy expenditure greater than predicted based on changes in body composition, occurs after nonsurgical weight loss (3–6). For instance, an approximately 10% diet-induced weight loss results in a 120–300 kcal/d deficit in total energy expenditure (TEE) (3–5), a reduction that may predispose to weight regain (7). In contrast, studies examining energy expenditure in mouse models after bariatric surgeries (mostly Roux-en-y bypass [RYGB]) demonstrate increased energy expenditure with surgery-induced weight loss (8–10). It is controversial whether metabolic adaptation occurs after bariatric surgery in humans. A 200-kcal/d reduction in TEE in a metabolic chamber has been observed 6 months after RYGB, which was not evident after 1 year (11). Similarly, a metabolic adaptation in TEE and energy expenditure during sleep was reported in adolescents 6 months after RYGB (12). In contrast, such an adaptation has not been observed when measuring changes in energy expenditure at rest 3 and 12 months after RYGB (13–15). It is therefore not clear whether weight loss after bariatric surgery induces adaptations in energy metabolism and whether the magnitude of the change in energy metabolism is related to the type of surgery.

The aims of this study were to characterize the effect of weight loss after RYGB, sleeve gastrectomy (SG), laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB), or a low-calorie diet (LCD) on changes in energy expenditure and circulating cardiometabolic markers and to examine whether there were associations between changes in metabolic adaptation and circulating cardiometabolic markers. The LAGB is hypothesized to induce weight loss by restricting dietary intake and should therefore be comparable to the LCD group. Both RYGB and LAGB produce weight loss by altering gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology. As such, we hypothesized that the degree of metabolic adaptation would be attenuated after RYGB and SG compared to LAGB and LCD groups.

Subjects and Methods

Selection and description of participants

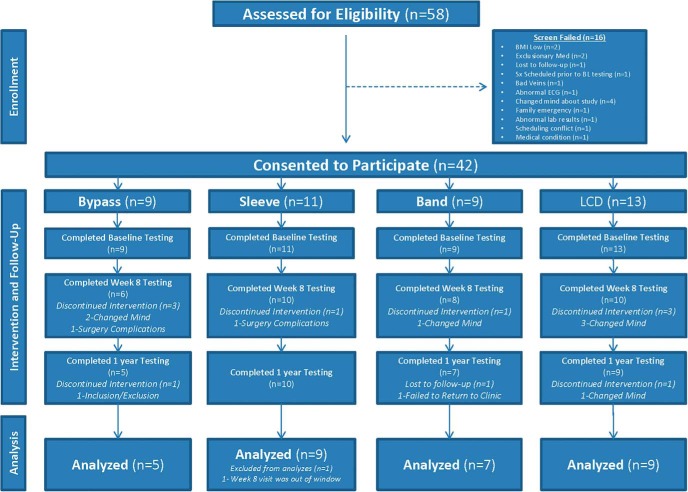

This was a parallel-arm, prospective observational study of individuals self-selecting bariatric surgery (RYGB, SG, or LAGB). Individuals with the same inclusion/exclusion criteria but who could not afford bariatric surgery or who did not want surgery were enrolled for a LCD intervention. Surgery subjects were recruited through offices of bariatric surgeons in the Baton Rouge and New Orleans areas, and LCD subjects were recruited from the same offices and by local advertisement. Potential participants who had diabetes diagnosed more than 5 years ago or had previous malabsorptive or restrictive surgery, a history of inflammatory intestinal disease, psychiatric conditions, or the use of medications that affect weight or metabolic rate were excluded. The study was conducted at Pennington Biomedical Research Center under oversight by Pennington Biomedical and Western Institutional Review Boards, and all subjects provided informed consent before taking part in the research (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00936130). Between 2009 and 2013, a total of 58 potential subjects were screened for this study, and 42 of these were considered eligible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing recruitment, study flow, and follow-up of participants.

Study design and experimental procedures

Participants underwent comprehensive clinical testing at baseline (before having surgery or initiation of LCD) and at 8 weeks and 1 year after the treatment intervention. This consisted of energy expenditure measured over 24 hours in a metabolic chamber and resting metabolic rate measured by indirect calorimetry (metabolic cart). Body composition measurements, including assessment of fat mass and fat-free mass by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans (Lunar iDXA; GE Healthcare), were performed monthly. Surgery subjects attended monthly clinic visits, and the LCD group had weekly visits with a dietician for the first 8 weeks and monthly visits thereafter.

Surgical procedures and dietary intervention

Bariatric surgeons in Baton Rouge and the surrounding communities referred patients interested in participating in the study during the preoperative evaluation conducted by the surgeon. The subjects who passed the surgeon’s preoperative evaluation, fulfilled the study criteria, and signed an informed consent were enrolled in the study and completed the baseline study procedures before their operations. Participants selected their surgical procedure, after discussions with their surgeons, and all surgical procedures were done laparoscopically. The three surgical procedures were done in the standard manner according to each surgeon’s routine practice, and the options included RYGB, SG, and LAGB. The LCD group consumed 800 kcal/d (6% fat, 56% carbohydrate, 38% protein) for 8 weeks (Health One, Health and Nutrition Technology), followed by prescription of a balanced diet containing 500 kcal/d less than required for maintenance of body weight (measured energy expenditure at week 8 −500 kcal/d).

Assessment of energy expenditure

24-hour sedentary and sleeping energy expenditure

The sedentary 24hrEE was measured over 23 hours in a whole-room indirect calorimeter as previously described (16). Three meals and one snack were provided at scheduled intervals, and participants were instructed to eat all their food within 30 minutes. Energy expenditure was calculated from VO2, VCO2, and 24-hour urinary nitrogen excretion according to the Weir equation (17) and extrapolated to 24 hours. SleepEE was calculated between 2 and 5 am, when motion detectors were reading zero activity. Resting metabolic rate (RMR) in the chamber was calculated using the intercept (zero activity) of the linear regression between energy expenditure and activity (18). Energy intake was provided to match energy expenditure in all groups at baseline and at 1 year using institutional equations based on fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and sex (16). Given the limitations on food intake for participants who underwent bariatric surgery, the food intake in the chamber during the week 8 assessment was provided at 890 kcal/d for all subjects. Two individuals were unable to consume all the food provided at 1 year; however, their negative energy balance did not adversely impact the metabolic adaptation for their respective groups (data not shown).

Resting metabolic rate

RMR was also determined by indirect calorimetry (Max II Metabolic Cart; AEI Technologies) over 30 minutes.

Percentage activity and spontaneous physical activity

Two measurements of physical activity were quantified from the metabolic chamber as previously described (19, 20). These include percentage activity, defined as the percentage of time that the participant was active throughout the 24-hour period, and spontaneous physical activity (SPA), defined as the energy expended in spontaneous activities (kilocalories/day). Briefly, two radar motion detectors (model D9/50; Microwave Sensors) mounted in the chamber detected SPA. Both units, placed at opposite ends of the respiratory chamber, were set to detect any movement greater than chest movement in breathing and provided information irrespective of work intensity. The output of both radars was analyzed by the data acquisition system and averaged over 15-minute periods.

Biochemical analyses

Insulin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), T3, T4, and TSH were measured by immunoassay with chemiluminescent detection (Siemens). Leptin and total and high molecular weight adiponectin were measured using RIAs or ELISAs (Millipore). Glucose was analyzed using an oxidase electrode method (DXC600; Beckman Coulter).

Calculations and statistics

Metabolic adaptation was calculated as the difference between measured energy expenditure (24hrEE, SleepEE, RMR measured in the chamber and during the clamp) and energy expenditure predicted from a linear regression including sex (female = 0, male = 1) and body composition (fat-free mass and fat mass) measured at baseline (n = 34). Residual values (observed − predicted) were calculated at baseline, week 8, and 1-year periods. The difference in residual values (follow-up − baseline) was then used as a marker of the extent at which energy expenditure adapted to weight loss; ie, a negative value indicates metabolic adaptation (21).

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.1.2 and SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp). Data are presented as observed means ± SEM. Group differences at baseline were assessed using one-way ANOVA. Mixed models were used to examine the effect of group, time, and group*time interactions on dependent variables. The change from baseline to each time-point was used as the dependent variable, and the respective baseline value and sex were used as covariates in the model.

Results

The CONSORT flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. Out of 42 eligible subjects, 11 discontinued the study due to time constraints (n = 7), postsurgical complications (n = 2), and loss to follow-up (n = 2). Three subjects were excluded from final analyses because they did not complete all three study visits at baseline, week 8, and 1 year, and one subject was excluded because surgery was performed 6 months after baseline clinical testing. Final data analyses were performed on 30 subjects (27 females; mean age, 46 ± 2 years; mean body mass index, 47.2 ± 1.5 kg/m2), of whom 21 subjects underwent scheduled bariatric surgery (five RYGB, nine SG, and seven LAGB) and nine subjects underwent a LCD intervention (Figure 1). Four of the 30 participants (two RYGB, one SG, and one LCD) had diabetes diagnosed less than 5 years earlier.

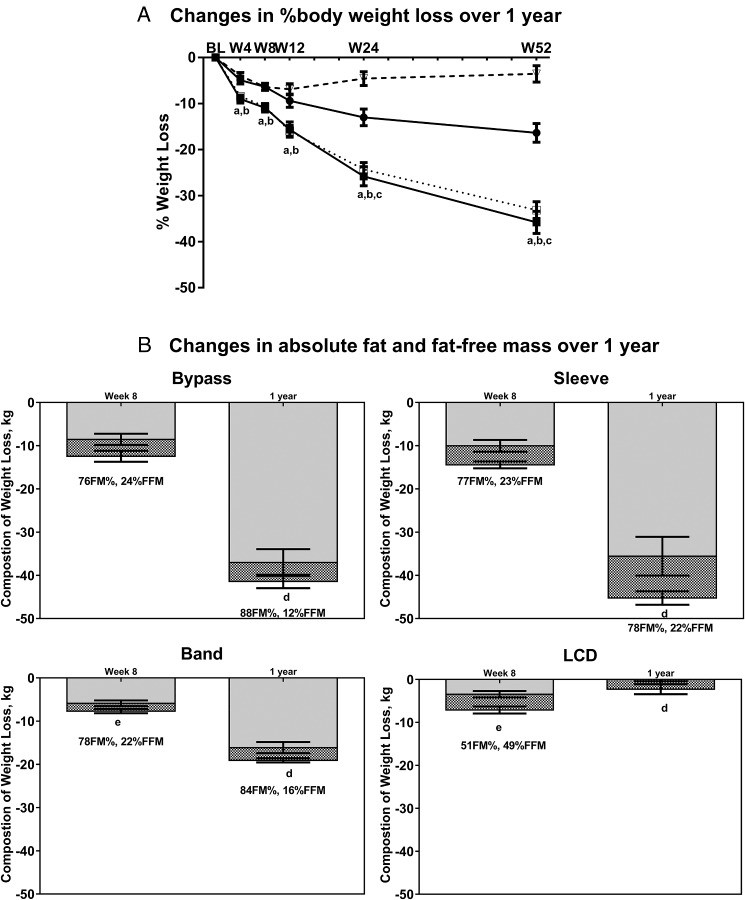

Weight and body composition

Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical characteristics for the groups at baseline are presented in Supplemental Table 1. After 1 year, RYGB and SG had similar degrees of body weight loss (33–36%), with 16 and 4% weight loss in the LAGB and LCD groups, respectively (Figure 2A). LAGB and LCD demonstrated similar body weight loss trajectories up to 12 weeks, after which weight loss continued in the LAGB group but returned to baseline levels in the LCD group. As expected, weight loss caused significant reductions in absolute fat mass and fat-free mass over time in all groups (all P < .001; Figure 2B). Most weight loss was attributed to losses in fat mass, with the proportion of fat mass lost not different between surgery groups after 1 year (RYGB = 88%; SG = 78%; LAGB = 84%).

Figure 2.

Percentage body weight loss and changes in body composition after bariatric surgery and LCD. A, Changes in percentage body weight loss over 1 year. RYGB, filled square and solid line; SG, open square and dotted line; LAGB, filled circle and solid line; LCD, open triangle and dashed line. a, P < .05 for RYGB vs LAGB and RYGB vs LCD; b, P < .05 for SG vs LAGB and SG vs LCD; c, P < .001 for LAGB vs LCD. B, Changes in absolute fat mass and fat-free mass over 1 year. d, P > .05 for LCD vs RYGB, SG, and LAGB for percentage fat mass and percentage fat-free mass; e, P < .05 LAGB vs LCD for percentage fat mass and percentage fat-free mass. Data are presented as observed means ± SEM. Gray bars, fat mass (FM); hashed bars, fat-free mass (FFM).

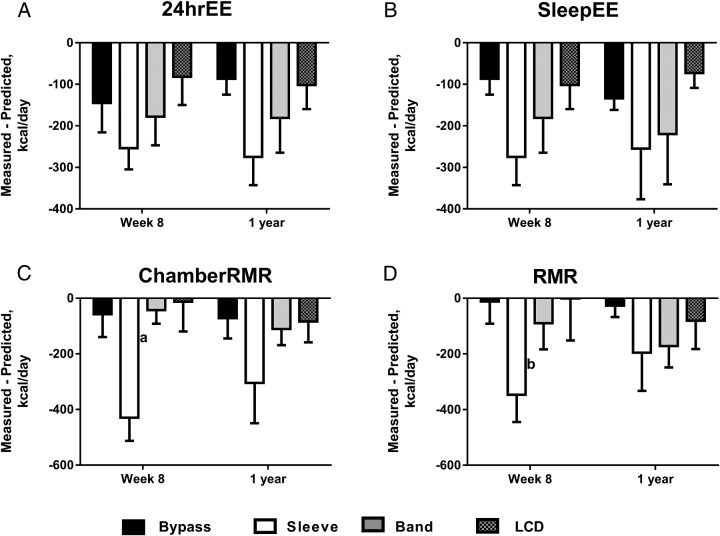

Changes in 24hrEE, SleepEE, and resting energy expenditure

The 24hrEE and SleepEE were significantly reduced (all P < .05) from baseline in all study groups at 8 weeks and 1 year post-treatment, with the exception of the LCD group between baseline and 1 year for 24hrEE. After adjustment for decreases in fat-free mass and fat mass, 24hrEE (Table 1) was significantly decreased from baseline at 8 weeks post-treatment in all groups (RYGB, −145 ± 71; SG, −254 ± 51; LAGB, −178 ± 69; LCD, −82 ± 68 kcal/d), but persisted at 1 year only after RYGB and SG (RYGB, −124 ± 42; SG, −155 ± 118 kcal/d). Similar trends were observed for SleepEE residual (Table 1), with significant reductions in all surgery groups 8 weeks after surgery (RYGB, −87 ± 38; SG, −275 ± 68; LAGB, −181 ± 84 kcal/d), which were maintained 1 year after surgery (RYGB, −134 ± 28; SG, −255 ± 122; LAGB, −220 ± 121 kcal/d). SleepEE residuals at 1 year were significantly higher in all surgery groups compared to the LCD group (all P < .05). For 24hrEE and SleepEE, the degree of metabolic adaptation was not significantly different between the four treatments at either time-point (Figure 3). Similar findings were seen for chamber RMR with decreases in adjusted RMR (residuals) of −58 to −430 kcal/d in RYGB and SG groups at 8 weeks and 1 year and in RMR measured using the ventilated hood (Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 3). 24hrEE and SleepEE residuals were also analyzed, comparing: 1) combined surgery groups (RYGB/SG/LAGB; n = 21) vs LCD; and 2) combined RYGB/SG (n = 14) vs LCD groups. Similar to the results above, we found significant metabolic adaptations in surgery compared to LCD groups, with deficits of approximately 200 kcal/d for 24hrEE and SleepEE (data not shown). We also found that the degree of metabolic adaptation was not significantly different between the combined surgery groups and LCD groups at either time-point (data not shown).

Table 1.

Absolute Energy Expenditure (24-Hour Sedentary and Sleeping) Measured in a Metabolic Chamber Before Surgery (Baseline) and at 8 Weeks and 1 Year After Surgery

| 24hrEE, kcal/d | SleepEE, kcal/d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Predictedb | Residual | Measured | Predictedc | Residual | |

| RYGB | ||||||

| Baseline | 2204 (89) | 1714 (63) | ||||

| Wk 8 | 1909 (53) | 2154 (64) | −145 (71)a | 1513 (84) | 1744 (55) | −87 (38)a |

| 1 y | 1709 (85) | 1933 (68) | −124 (42)a | 1352 (63) | 1631 (53) | −134 (28)b |

| SG | ||||||

| Baseline | 2680 (128) | 2250 (117) | ||||

| Wk 8 | 2218 (73) | 2432 (97) | −254 (51)a | 1793 (63) | 1950 (70) | −275 (68)a |

| 1 y | 2058 (87) | 2237 (88) | −155 (118)a | 1605 (77) | 1840 (77) | −255 (122)a |

| LAGB | ||||||

| Baseline | 2278 (113) | 1863 (89) | ||||

| Wk 8 | 2005 (94) | 2229 (97) | −178 (69)a | 1599 (59) | 1807 (68) | −181 (84)a |

| 1 y | 1931 (126) | 2128 (91) | −123 (113) | 1503 (91) | 1746 (73) | −220 (121)a |

| LCD | ||||||

| Baseline | 2441 (137) | 2070 (167) | ||||

| Wk 8 | 2244 (138) | 2271 (122) | −82 (68)a | 1870 (163) | 1838 (93) | −102 (58) |

| 1 y | 2330 (177) | 2426 (142) | −132 (27) | 1939 (184) | 1931 (96) | −73 (36) |

Data are presented as mean (SEM) kcal/d. P values (aP < .05; bP < .001) indicate differences between actual vs predicted values (paired sample t test).

Predicted energy expenditures were calculated as follows. b 24hrEE = 655 + 22.2 × fat-free mass + 7.4 × fat mass + 40.6 × sex (female = 0 and male = 1) (r2 = 0.63; P < 0.001). c SleepEE = 519 + 21.0 × fat-free mass + 3.6 × fat mass − 160.5 × sex (female = 0 and male = 1) (r2 = 0.40; P < .001).

Figure 3.

Changes in sedentary 24-hrEE (A), SleepEE (B), and RMR measured in a metabolic chamber (C) or by ventilated hood (D) not attributed to changes in fat-free mass and fat mass at 8 weeks and 1 year after treatment. Black bars, RYGB; white bars, SG; gray bars, LAGB; hashed bars, LCD. “Measured-Predicted” refers to the difference between measured values and the values predicted by our regression model based on baseline relationships of fat-free mass and fat mass to energy expenditure measures (often called residuals; see Subjects and Methods). Data are presented as observed means ± SEM, and P values refer to differences in change over time between treatment groups. a, P < .05 between SG vs RYGB, LAGB, and LCD groups; b, P < .05 between SG vs RYGB and LCD groups.

Physical activity levels

The drop in SPA levels was significantly greater in the LCD group at 1 year compared to RYGB (Supplemental Table 3). No other significant differences in SPA or percentage activity/day were observed.

Changes in circulating markers of metabolic adaptation

At 1 year, the drop in leptin was greatest in the surgery groups, compared to LCD. Similarly, the drop in T3 and T4 was greatest 1 year post-SG compared to LCD.

In the whole cohort, a greater percentage weight loss was associated with greater reductions in leptin (P < .001; r = 0.66), T3 (P = .04; r = 0.47), and T4 concentrations (P = .003; r = 0.62) at 1 year. TSH levels were unchanged in all treatment groups at both time-points (Table 2). Furthermore, the degree of metabolic adaptation (residuals) and changes in leptin, T3, T4, or TSH at either time-point (with and without adjusting for weight loss), however, were not associated.

Table 2.

Changes in Circulating Biochemical Markers After Surgery and Diet-Induced Weight Loss

| RYGB | SG | LAGB | LCD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic markers | ||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 107 ± 8 | 108 ± 3 | 102 ± 3 | 111 ± 9 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −12 ± 4 | −18 ± 5 | −13 ± 1 | −14 ± 4 |

| Δ 1 yr | −12 ± 5a | −19 ± 4a | −11 ± 3a | 1 ± 5b,c,d |

| Insulin, mU/mL | ||||

| Baseline | 17.6 ± 6.9 | 21.5 ± 4.5 | 15.5 ± 2.3 | 25.6 ± 7.3 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −12.0 ± 7.6 | −11.8 ± 2.9 | −5.8 ± 1.4 | −12.3 ± 2.8 |

| Δ 1 yr | −12.3 ± 7.2a | −20.2 ± 5.5a,d | −5.0 ± 1.7c | −5.3 ± 2.9b,c |

| HOMA-IR score* | ||||

| Baseline | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 8.1 ± 3.3 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −3.2 ± 2.1 | −3.9 ± 1.0 | −1.7 ± 0.3 | −4.5 ± 1.3 |

| Δ 1 yr | −3.2 ± 1.8a | −6.1 ± 1.6a | −1.3 ± 0.4 | −1.5 ± 0.9b,c |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 128.2 ± 42.8 | 144.1 ± 30.6 | 135.0 ± 13.4 | 113.1 ± 21.2 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −29.0 ± 35.8 | −49.0 ± 18.2 | −36.7 ± 18.9 | −18.7 ± 15.8 |

| Δ 1 yr | −60.4 ± 40.2a | −65.8 ± 20.7a | −36.7 ± 16.4 | 6.1 ± 5.7b,c |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 173.2 ± 20.0 | 167.1 ± 17.7 | 193.4 ± 8.2 | 176.1 ± 8.4 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −11.8 ± 9.4 | −21.8 ± 12.4 | −23.0 ± 14.8 | −12.8 ± 8.0 |

| Δ 1 yr | −0.2 ± 9.2 | 2.1 ± 10.9 | −7.1 ± 5.6 | 9.3 ± 12.8 |

| HDL, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 51.3 ± 3.7 | 50.2 ± 4.2 | 46.1 ± 3.8 | 49.4 ± 2.6 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −9.6 ± 5.8 | −6.1 ± 2.6 | −1.4 ± 1.3 | −5.1 ± 2.2 |

| Δ 1 yr | 12.2 ± 6.7a | 9.2 ± 3.7a | 7.8 ± 2.0 | −0.7 ± 2.1b,c |

| LDL, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 96.3 ± 21.8 | 88.1 ± 12.1 | 120.3 ± 6.3 | 104.1 ± 7.8 |

| Δ Wk 8 | 3.6 ± 12.1 | −5.9 ± 8.5 | −14.2 ± 10.8 | −3.9 ± 6.9 |

| Δ 1 yr | −0.3 ± 9.4 | 6.1 ± 8.4 | −7.6 ± 4.2 | 8.8 ± 10.0 |

| HDL-to-LDL ratio | ||||

| Baseline | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −0.2 ± 0.1d | −0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1b | 0 ± 0 |

| Δ 1 yr | 0 ± 0.1a | 0 ± 0.1a | 0.1 ± 0a | 0 ± 0b,c,d |

| Inflammation | ||||

| Total adiponectin, units | ||||

| Baseline | 16.3 ± 6.4 | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 7.6 ± 2.4 | 8.6 ± 1.5 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −1.6 ± 5.6 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 0.7 |

| Δ 1 yr | 10.2 ± 8.0a,c,d | 3.8 ± 1.1b | 3.4 ± 1.1b | 1.8 ± 0.9b |

| HMW adiponectin, μg/mL | ||||

| Baseline | 10 189 ± 5194 | 2596 ± 364 | 4783 ± 1457 | 3672 ± 707 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −2103 ± 4508 | 1192 ± 201 | −96 ± 331 | 441 ± 416 |

| Δ 1 yr | 4180 ± 5618a,c,d | 3359 ± 405b | 1765 ± 538b | 469 ± 362b |

| hsCRP, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 9.7 ± 5.3 | 13.4 ± 3.0 | 10.1 ± 2.3 | 8.3 ± 1.5 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −1.6 ± 3.1 | −5.5 ± 2.3 | −0.7 ± 1.2 | −1.6 ± 1.1 |

| Δ 1 yr | −8.6 ± 4.3a | −10.0 ± 2.8a | −4.3 ± 1.3 | −2.1 ± 1.3b,c |

| Markers of metabolic adaptation | ||||

| Leptin, ng/mL | ||||

| Baseline | 46.7 ± 7.7 | 54.1 ± 5.4 | 55.1 ± 5.4 | 80.8 ± 16.1 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −20.1 ± 6.9 | −14.8 ± 4.0 | −13.8 ± 5.4 | −17.9 ± 6.8 |

| Δ 1 yr | −32.6 ± 6.6a,d | −30.0 ± 4.2a | −14.0 ± 7.8a,b | −1.8 ± 8.1a,b,c,d |

| T3, ng/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 95.9 ± 5.4 | 128.4 ± 8.7 | 100.0 ± 6.5 | 134.6 ± 11.5 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −5.2 ± 7.4 | −21.7 ± 7.1 | −8.4 ± 5.5 | −15.5 ± 9.1 |

| Δ 1 yr | −15.5 ± 6.5 | −39.6 ± 7.6a,d | −2.7 ± 4.0c | −19.7 ± 7.2c |

| T4, μg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 8.7 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.7 |

| Δ Wk 8 | −1.0 ± 0.2a | −0.4 ± 0.4a | −0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.4b,c |

| Δ 1 yr | −1.5 ± 0.4 | −1.6 ± 0.4a,d | −0.1 ± 0.2c | −0.2 ± 0.4c |

| TSH, μIU/mL | ||||

| Baseline | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| Δ Wk 8 | 1.3 ± 1.3a,c,d | −0.1 ± 0.3b | −0.6 ± 0.1b | −0.4 ± 0.3b |

| Δ 1 y | −0.8 ± 0.6 | −0.3 ± 0.3 | −0.3 ± 0.2 | −0.2 ± 0.4 |

Abbreviations: HMW, high molecular weight; LDL, low-density lipoprotein. Baseline and change from baseline values are the observed means ± SEM. P values were derived using mixed models to examine the effect of group, time, and group * time interactions on the dependent variable (change from baseline to each time-point). Models were adjusted for respective baseline values and sex.

Significantly different (P < .05) from LCD.

Significantly different (P < .05) from RYGB.

Significantly different (P < .05) from SG.

Significantly different (P < .05) from LAGB.

HOMA-IR score is expressed as [fasting glucose (millimoles per liter) × fasting insulin (microunits per milliliter)]/22.5.

Changes in circulating cardiometabolic markers

Fasting plasma glucose was significantly lower 1 year after surgery (RYGB, SG, and LAGB) compared to the LCD group. Similarly, the drop in insulin levels was greatest 1 year after RYGB or SG compared to the LCD and LAGB groups. As such, the greatest improvement in homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was 1 year after RYGB or SG, compared to the LCD group (Table 2).

Plasma triglycerides were significantly reduced, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels were significantly increased 1 year after RYGB or SG, compared to the LCD group (Table 2). Regarding systemic inflammation, total and high molecular weight adiponectin were increased, and hsCRP was reduced 1 year after RYGB and SG, compared to the LCD group; no significant changes were seen at week 8 in any of the treatment groups (Table 2).

At 1 year, the change in circulating hsCRP concentration was positively associated with RMR in the chamber residual (P = .03; r = 0.54), an association that remained after adjustment for percentage weight loss (P = .05; r = 0.49); no other associations were observed at either time-point.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that weight loss in obese individuals after RYGB, SG, and LAGB bariatric surgery leads to metabolic adaptations (decrease in energy expenditure independent of the loss of fat-free mass and fat mass) in energy expenditure (24hrEE and SleepEE) of −190 to −230 kcal/d as early as 8 weeks after surgery and persistent up to 1 year later. These metabolic adaptations complement earlier findings in obese individuals undergoing diet-induced weight loss which report similar degrees of metabolic adaptation (−120 to −300 kcal/d). We hypothesized that metabolic adaptations may occur as a homeostatic response to weight loss in order to foster weight regain as the body attempts to restore its energetic set-point (7). Interestingly, in the current study, a metabolic adaptation of 80 kcal/d in sedentary 24hrEE (but not SleepEE) occurred in the LCD group at 8 weeks (∼5% weight loss) but did not remain 1 year later.

The literature is controversial regarding the persistence of energy adaptations after surgery-induced weight loss and may be confounded by the fact that few studies have appropriately accounted for losses in fat-free mass that are known to exert a strong effect on energy metabolism (11, 12, 22, 23). Carrasco et al (22) reported a 29% decrease in total body weight 6 months after RYGB, accompanied by a 93 kcal/d deficit in resting energy expenditure. Our finding supports a previous study in adolescents where 6 months after RYGB, total and sleep energy expenditure were decreased after adjustment for fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and sex (12). In contrast, other studies examining resting energy expenditure at 3 and 12 months after RYGB found no differences after adjusting for the effects of fat-free mass and fat mass (13–15). Furthermore, Knuth et al (11) found an approximately 200-kcal/d deficit in obese patients 6 months after RYGB, which disappeared by 12 months. A recent study reported that energy adaptations of −280 to −350 kcal/d persisted up to 2 years after RYGB and SG surgery, even after weight loss had plateaued (24). However, “gold-standard” measures of energy expenditure and body composition were not performed, nor was an LCD group examined in that study.

Our study provides the first detailed comparison of the effects of different bariatric surgery types on energy expenditure and, together with previous findings, underscores the need for longer term follow-up studies to investigate whether metabolic adaptations persist after 1 year and the relevance of these adaptations to weight loss stability. Interestingly, studies of diet-induced weight loss have demonstrated that significant metabolic adaptations (−100 to −900 kcal/d) persist after weight-loss plateaus or regains, and that these energetic adaptations occur regardless of whether weight loss is maintained for weeks or years (6, 7). Nevertheless, our finding that metabolic adaptation was not blunted after RYGB and SG suggests that other mechanisms apart from reduced energy expenditure contribute to the weight loss and metabolic benefits of surgery. Decreases in circulating leptin and thyroid hormones and blunted activity of the sympathetic nervous system are proposed mechanisms underlying metabolic adaptation. Previous studies using diet-induced weight loss demonstrate that the degree of metabolic adaptation is directly correlated with the reduction in circulating leptin (11, 25), suggesting that after accounting for fat mass changes, leptin may be a significant determinant of metabolic adaptation in overweight individuals (20). Supporting this, replacement of circulating leptin to pre-weight-loss levels reverses metabolic adaptation (26). Such associations were not observed in our study of individuals undergoing bariatric surgery, offering further support that alternative mechanisms apart from reduced energy expenditure are contributing to surgery-induced weight loss.

Impaired glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle is one of the most common metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity and is an important risk factor for the development of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (27). In keeping with previously published literature (28), we found significant drops in glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR 1 year after bariatric surgery (16–36% weight loss). In parallel, improvements in systemic inflammation including increased total and high molecular weight adiponectin and decreased hsCRP were also seen 1 year after RYGB or SG.

The strengths of our study are that it is the first study that has comprehensively investigated energy expenditure after different bariatric surgery types using gold-standard techniques. Energy expenditure measures obtained from the metabolic chamber allow accurate real-time simultaneous measurement of all components of energy expenditure in an experimental setting that is close to free-living conditions. Potential limitations of our study may include the lack of randomization for treatments. Performing a randomized control trial in this study was not possible due to the cost of surgeries. Previous randomized control trials comparing bariatric surgery with medical therapy were performed with the primary purpose of testing the short-term safety of bariatric surgery, and not to examine mechanisms of its effects. Importantly, the baseline characteristics of our treatment groups were not significantly different, allowing comparisons across groups after intervention. Another limitation may be the low sample size in study groups. With four treatment groups, a significance level of 0.05, and a difference of 150 kcal/d between groups and 130–170 kcal/d within groups, we would require five to six subjects per group to achieve >80% power to determine a difference between treatment groups. Overall, studies involving metabolic adaptation measured through 24hrEE or SleepEE in a room calorimeter are appropriately powered (β ≥ 0.8) with small numbers of subjects because the reliability of these measures is approximately 3%.

In conclusion, we found that metabolic adaptation of approximately 150 kcal/d occurs up to 1 year after RYGB, SG, and LAGB surgery. Our findings in obese individuals after bariatric surgery extend those already available after diet-induced weight loss, suggesting that a deficit in energy adaptation may be a homeostatic mechanism encouraging weight regain. Future studies are required to examine whether these effects remain beyond 1 year and contribute to the metabolic benefits of bariatric surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants in this study and the dedicated staff of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center inpatient and outpatient units.

This work was supported by Ethicon-Endo Surgery Inc. and partially supported by the infrastructure of Nutrition Obesity Research Center Grant P30DK072476 (to E.R.). C.S.T. is supported by National Health and Medical Research Centre Early Career Fellowship (no. 1037275) from Australia.

Clinicaltrials.gov registration no.: NCT00936130.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- 24hrEE

24-hour energy expenditure

- hsCRP

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LAGB

laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

- LCD

low-calorie diet

- RMR

resting metabolic rate

- RYGB

Roux-en-y bypass

- SG

sleeve gastrectomy

- SleepEE

sleeping energy expenditure

- SPA

spontaneous physical activity

- TEE

total energy expenditure.

References

- 1. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heilbronn LK, de Jonge L, Frisard MI, et al. Effect of 6-month calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity, metabolic adaptation, and oxidative stress in overweight individuals: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1539–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10):621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ravussin E, Redman LM, Rochon J, et al. A 2-year randomized controlled trial of human caloric restriction: feasibility and effects on predictors of health span and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(9):1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(8):1612–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J, Gallagher DA, Leibel RL. Long-term persistence of adaptive thermogenesis in subjects who have maintained a reduced body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nestoridi E, Kvas S, Kucharczyk J, Stylopoulos N. Resting energy expenditure and energetic cost of feeding are augmented after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153(5):2234–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stylopoulos N, Hoppin AG, Kaplan LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass enhances energy expenditure and extends lifespan in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(10):1839–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hao Z, Mumphrey MB, Townsend RL, et al. Body composition, food intake, and energy expenditure in a murine model of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26(9):2173–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knuth ND, Johannsen DL, Tamboli RA, et al. Metabolic adaptation following massive weight loss is related to the degree of energy imbalance and changes in circulating leptin. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(12):2563–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butte NF, Brandt ML, Wong WW, et al. Energetic adaptations persist after bariatric surgery in severely obese adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(3):591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Das SK, Roberts SB, McCrory MA, et al. Long-term changes in energy expenditure and body composition after massive weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dirksen C, Jørgensen NB, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Gut hormones, early dumping and resting energy expenditure in patients with good and poor weight loss response after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(11):1452–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Castro Cesar M, de Lima Montebelo MI, Rasera I Jr, de Oliveira AV Jr, Gomes Gonelli PR, Aparecida Cardoso G. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on resting energy expenditure in women. Obes Surg. 2008;18(11):1376–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lam YY, Redman LM, Smith SR, et al. Determinants of sedentary 24-h energy expenditure: equations for energy prescription and adjustment in a respiratory chamber. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):834–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weir JB. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol. 1949;109:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tataranni PA, Larson DE, Snitker S, Ravussin E. Thermic effect of food in humans: methods and results from use of a respiratory chamber. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(5):1013–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nguyen T, de Jonge L, Smith SR, Bray GA. Chamber for indirect calorimetry with accurate measurement and time discrimination of metabolic plateaus of over 20 min. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2003;41(5):572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ravussin E, Lillioja S, Anderson TE, Christin L, Bogardus C. Determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure in man. Methods and results using a respiratory chamber. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(6):1568–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galgani JE, Santos JL. Insights about weight loss-induced metabolic adaptation. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(2):277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carrasco F, Papapietro K, Csendes A, et al. Changes in resting energy expenditure and body composition after weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17(5):608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faria SL, Faria OP, Cardeal Mde A, Ito MK, Buffington C. Diet-induced thermogenesis and respiratory quotient after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a prospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(1):138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tam CS, Rigas G, Heilbronn LK, Matisan T, Probst Y, Talbot M. Energy adaptations persist 2 years after sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26(2):459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lecoultre V, Ravussin E, Redman LM. The fall in leptin concentration is a major determinant of the metabolic adaptation induced by caloric restriction independently of the changes in leptin circadian rhythms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):E1512–E1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenbaum M, Goldsmith R, Bloomfield D, et al. Low-dose leptin reverses skeletal muscle, autonomic, and neuroendocrine adaptations to maintenance of reduced weight. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3579–3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32Suppl 2:S157–S163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu Y, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Marcelin G, et al. Accumulation and changes in composition of collagens in subcutaneous adipose tissue after bariatric surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(1):293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.