The RalGAPα1/β complex links insulin signaling to glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle through RalA activation.

Abstract

How insulin stimulates postprandial uptake of glucose and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) into skeletal muscle and the mechanisms by which these events are dampened in diet-induced obesity are incompletely understood. Here, we show that RalGAPα1 is a critical regulator of muscle insulin action and governs both glucose and lipid homeostasis. A high-fat diet increased RalGAPα1 protein but decreased its insulin-responsive Thr735-phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. A RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation impaired insulin-stimulated muscle assimilation of glucose and LCFAs and caused metabolic syndrome in mice. In contrast, skeletal muscle–specific deletion of RalGAPα1 improved postprandial glucose and lipid control. Mechanistically, these mutations of RalGAPα1 affected translocation of insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4 and fatty acid translocase CD36 via RalA to affect glucose and lipid homeostasis. These data indicated RalGAPα1 as a dual-purpose target, for which we developed a peptide-blockade for improving muscle insulin sensitivity. Our findings have implications for drug discovery to combat metabolic disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become prevalent worldwide in recent decades because of changes in diet and lifestyle. Insulin resistance lessens the responses of target tissues to insulin stimulation and underlies the pathogenesis of T2D (1). Therefore, better understanding of insulin action and molecular basis for insulin resistance are key for drug development to combat T2D.

The skeletal muscle is the largest insulin-sensitive organ in the body and plays a key role in regulating postprandial glucose and lipid homeostasis (2, 3). When insulin binds to its receptor, it activates the receptor tyrosine kinase, resulting in tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRSs), which in turn initiate signaling via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–protein kinase B (PKB) (also known as Akt) signaling pathway that controls muscle glucose and lipid homeostasis (4). The insulin-PKB pathway also regulates protein synthesis via the tuberous sclerosis complex protein 1 and 2 (TSC1/2)–mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling axis (5). mTORC1 and its downstream target, ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K), can phosphorylate IRS on multiple serine residues, which inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS, providing feedback mechanisms that may prevent overactivation of the insulin signaling pathway (6). In diet-induced obesity, fatty acids can activate a number of kinases, including mTORC1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and PKC, which also phosphorylate serine residues in IRS and dampen insulin signaling (6). These changes in obesity provide a molecular basis for diet-induced muscle insulin resistance. However, it is currently unclear whether further IRS-independent mechanisms might contribute to development of muscle insulin resistance.

TSC1 and TSC2 form a guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activating protein (GAP) complex in which TSC2 is a catalytic subunit having GAP activity toward the small heterotrimeric guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP)–binding protein (G protein) Rheb and TSC1 is a regulatory subunit (7). Inactivation of the GAP of TSC1/2, for example, in response to insulin, promotes GTP loading and activation of Rheb and hence activates mTORC1. The TSC1/2 complex shares sequence and structural similarity with a RalGAP complex that consists of a catalytic RalGAPα subunit and a regulatory RalGAPβ subunit (8, 9). The RalGAP complex can stimulate GTP hydrolysis by two related small G proteins, namely, RalA and RalB (8). Active GTP-loaded RalA promotes docking of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) storage vesicles onto the plasma membrane through interaction with the exocyst and thereby regulates GLUT4 translocation in cultured adipocytes and muscle cells (10, 11). GTP-loaded RalB engages with the exocyst to activate mTORC1 (12), which suggests that the RalGAP complex might be involved in feedback regulation of IRS serine phosphorylation. In contrast to the single TSC1/2 complex, two RalGAP complexes exist in mammalian cells, in which catalytic subunits RalGAPα1 and RalGAPα2, respectively, bind to the common regulatory RalGAPβ subunit (8). The RalGAPα1/β complex is dominant in skeletal muscle, while RalGAPα2/β is the major complex in adipose tissues (13). RalGAPα1 is phosphorylated on its Thr735 by PKB in response to insulin, which results in its inactivation in rat L6 muscle cells. Inactivation of RalGAPα1 by Thr735 phosphorylation increases GTP-loaded active RalA that promotes translocation of GLUT4 from intracellular storage sites onto the plasma membrane in response to insulin (13). These findings in rat L6 muscle cells suggest a possible role for RalGAPα1 in mediating muscle insulin action. However, its exact roles in insulin action and resistance in skeletal muscle remain to be defined.

Here, we used mouse models to investigate the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of RalGAPα1 in muscle insulin action and resistance. Furthermore, we developed a strategy to target RalGAPα1 in muscle cells for improving insulin sensitivity.

RESULTS

Fatty acids induce expression of nonphosphorylated RalGAPα1 and inactivate RalA and RalB in skeletal muscle of obese mice

We used a site-specific antibody that recognizes phospho–Thr735-RalGAPα1 to monitor changes in RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation. This antibody was originally raised using a pThr715 peptide derived from RalGAPα2 (9). Because of the similarity of sequences surrounding Thr735-RalGAPα1 and Thr715-RalGAPα2 (fig. S1A), this antibody could also react with phospho–Thr735-RalGAPα1, and its specificity was confirmed by its failure to recognize RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutant protein (fig. S1B). The two endogenous RalGAPα proteins have distinct molecular sizes, and recognition of Thr735-RalGAPα1 and Thr715-RalGAPα2 on the endogenous proteins by this antibody was further confirmed in L6 myotubes and primary hepatocytes through down-regulation of these two proteins (fig. S1, C to E). Using this antibody, we found that Thr735 phosphorylation of RalGAPα1 was markedly diminished in skeletal muscle that was insulin resistant because of PKBβ deficiency (fig. S2A). High-fat diets (HFDs) are well-known to induce muscle insulin resistance, and we investigated their effects on RalGAPα1/β in skeletal muscle of diet-induced obese (DIO) mice. As expected, insulin-stimulated PKB phosphorylation was impaired in skeletal muscle of DIO mice (Fig. 1A and fig. S2B). The protein levels of RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ subunits were both substantially increased, while their mRNA levels were unaltered in skeletal muscle of DIO mice (Fig. 1A and fig. S2F). RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation was increased in skeletal muscle of mice fed with a normal chow diet upon insulin stimulation, while this phosphorylation was significantly lower in skeletal muscle of DIO mice under both basal and insulin conditions (Fig. 1A and fig. S2C). As a consequence, the GTP-bound active forms of RalA and RalB were notably decreased in skeletal muscle of DIO mice despite their normal mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A and fig. S2, D to F). In agreement with these findings, we found that, in differentiated L6 myotubes, oleic acid (OA) decreased insulin-stimulated PKB phosphorylation in concomitance with an elevation of IRS1-Ser307 phosphorylation (Fig. 1B and fig. S2, G and H). OA treatment increased RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ protein levels without affecting their mRNA levels and impaired RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation (Fig. 1B and fig. S2, I and K). OA treatment lowered the levels of active RalA and RalB in L6 myotubes (Fig. 1B and fig. S2, J and L) and concurrently impaired insulin-stimulated uptake of glucose and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) (fig. S2, M and N). Down-regulation of RalGAPα1 via small interfering RNA (siRNA) prevented OA-induced inactivation of RalA and RalB (fig. S2L). These data suggest that the RalGAPα1/β complex might play a role in diet-induced muscle insulin resistance.

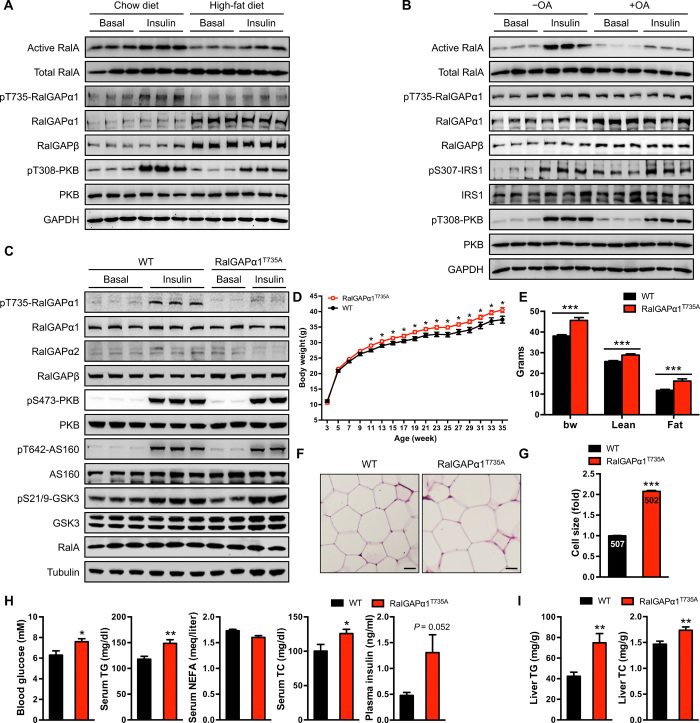

Fig. 1. Generation and characterization of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice.

(A) Expression and phosphorylation of the RalGAPα1/β complex, RalA activation, and PKB phosphorylation in the soleus muscle of male DIO mice (5 months old) in response to insulin. Mice were fasted overnight, and the soleus muscle was isolated for stimulation with or without insulin. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) Expression and phosphorylation of the RalGAPα1/β complex, RalA activation, IRS1, and PKB phosphorylation in L6 myotubes treated with or without OA (100 μM for 3 days) in response to insulin. (C) Phosphorylation and expression of RalGAPα1 and other key components of insulin-PKB pathway in the gastrocnemius muscle of wild-type (WT) and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (2 months old) in response to insulin. AS160, Akt substrate of 160 kDa; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3. (D) Growth curves of WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice from weaning until 35 weeks of age. n = 12 to 16. (E) Body composition of WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice measured at the age of 48 weeks. n = 13 to 14. bw, body weight. (F and G) Histology (F) and cell size (G) of the adipose of WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice (6 months old). Scale bars, 30 μm. The digits shown in the bar graphs refer to the number of adipocytes measured in the experiments. (H) Blood glucose, plasma insulin, total cholesterol (TC), nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA), and triglyceride (TG) in overnight-fasted WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice at 12 months of age. n = 7 to 9. (I) Liver TG and TC contents in the ad libitum WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice at 11 to 12 months of age. n = 13 to 14. Data are given as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

A RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation causes metabolic disorders in mice

To address the in vivo role of Thr735 phosphorylation of RalGAPα1, we generated a RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mouse model using a gene-targeting strategy (fig. S3, A and B) in which the Thr735 on RalGAPa1 was mutated to a nonphosphorylatable alanine residue. In skeletal muscle, the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutant protein was expressed at a level similar to the counterpart in wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 1C). Insulin stimulated Thr735 phosphorylation on RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle of WT mice (Fig. 1C). In contrast and as expected, Thr735 phosphorylation of the mutant RalGAPα1Thr735Ala protein was undetectable in skeletal muscle of knock-in mice (Fig. 1C). This knock-in mutation neither altered expression of RalGAPβ nor elicited any compensatory response in RalGAPα2 in various tissues (Fig. 1C and fig. S3, C to E). Furthermore, the knock-in mutation did not impair insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of PKB and its substrates AS160 (Akt substrate of 160 kDa, also known as TBC1D4) and GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase 3) in skeletal muscle, white adipose tissue (WAT), and liver (Fig. 1C and fig. S3, C and D). These data demonstrate the suitability of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice and their derived tissues for studying the specific in vivo and in vitro role of RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation.

We monitored the growth of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice and found that they weighed more than their WT littermates from the age of 10 weeks onward with normal food intake (Fig. 1D and fig. S3F). Body composition analysis revealed that knock-in mice had a greater fat mass than WT mice from around 5.5 months (Fig. 1E). Their adipocytes were also larger in size than WT cells (Fig. 1, F and G). At a young age (7 to 8 weeks old), knock-in mice had normal fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels, but their blood triglyceride (TG), free fatty acid (FFA), and total cholesterol (TC) were significantly elevated (fig. S3G). As the animals aged, fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice were both significantly elevated from around 6 months of age (Fig. 1H). Older knock-in mice still had higher blood TG and TC than their WT littermates (Fig. 1H), and their hepatic TG and TC were also higher than those of WT littermates (Fig. 1I), showing that knock-in mice developed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Together, these data demonstrate that the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation causes metabolic disorders in mice, suggesting that RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation is critical for metabolic health.

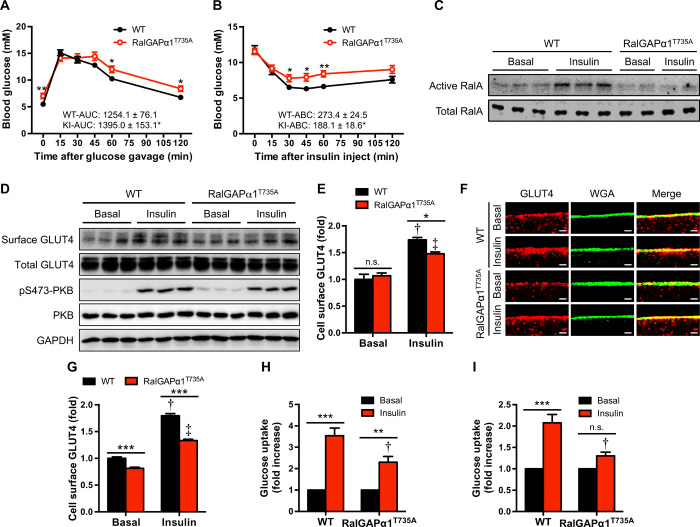

Insulin-stimulated RalA activation, GLUT4 translocation, and glucose uptake are impaired in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in skeletal muscle

We then sought to find out how the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation affected postprandial glycemic control. When orally gavaged with a bolus of glucose, knock-in mice were slower to clear blood glucose than their WT littermates at a young age (6 weeks old; fig. S3, H and I) and at an older age (12 months old; Fig. 2A). In agreement, they exhibited insulin resistance when intraperitoneally injected with insulin (Fig. 2B). Our previous work showed that overexpression of a RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutant protein inhibited insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation in cultured L6 myoblasts through suppressing RalA activation (13). In agreement with these findings, insulin activated RalA in skeletal muscle of WT mice but not in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (Fig. 2C). GLUT4 protein was expressed at comparable levels in skeletal muscle from the two genotypes (Fig. 2D). However, the insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface was markedly decreased in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala skeletal muscle ex vivo, compared with WT muscle, as assessed by immunoprecipitation of GLUT4 after cell surface proteins were biotinylated (Fig. 2, D and E). The impaired GLUT4 translocation in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala skeletal muscle was further confirmed using a fluorescence assay, staining for GLUT4 on the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, F and G). As a consequence of impaired GLUT4 translocation, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake was inhibited in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala skeletal muscle ex vivo (Fig. 2, H and I). In agreement with RalGAPα1 being a minor form and RalGAPα2 as a major form in the liver, WAT, and brown adipose tissue (BAT) (fig. S3E) (13), the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation did not affect RalA activation in response to insulin in these three tissues (fig. S3, K to M). Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation were normal in primary brown adipocytes and BAT from RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice, respectively (fig. S4, A and C). Together, these data show that the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation inhibited insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and thereby impaired postprandial glycemic control.

Fig. 2. Glucose homeostasis in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice.

(A) Oral glucose tolerance test in WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in (KI) male mice at the age of 12 months. The values show the glucose area under the curve (AUC) during glucose tolerance test. n = 7 to 8. (B) Insulin tolerance test in WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice at the age of 26 weeks. The values show the glucose area above the curve (ABC) during insulin tolerance test. n = 7 to 8. (C) GTP-bound active RalA in the gastrocnemius muscle of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (2 months old) treated with saline (basal) or insulin. (D) Cell surface and total GLUT4 levels in the soleus muscle of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. (E) Quantitation of cell surface GLUT4 contents in the soleus muscle of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. n = 6. Representative blots were shown in (D). †P < 0.001 (WT insulin versus WT basal) and ‡P < 0.001 (RalGAPα1Thr735Ala insulin versus RalGAPα1Thr735Ala basal). n.s., not significant. (F and G) GLUT4 staining in soleus muscle fibers of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. (F) Representative images. WGA, wheat germ agglutinin. (G) Quantitative data of cell surface GLUT4. At least 100 muscle fibers were quantified per condition/genotype. Scale bars, 2 μm. †P < 0.001 (WT insulin versus WT basal) and ‡P < 0.001 (RalGAPα1Thr735Ala insulin versus RalGAPα1Thr735Ala basal). (H and I) Glucose uptake in the soleus (H) or extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (I) muscle ex vivo of female WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. n = 6 to 8. Insulin-stimulated fold increases of glucose uptake were calculated rates in each genotype. †P < 0.01 (soleus) or P < 0.001 (EDL) (RalGAPα1Thr735Ala insulin versus WT insulin). Data are given as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

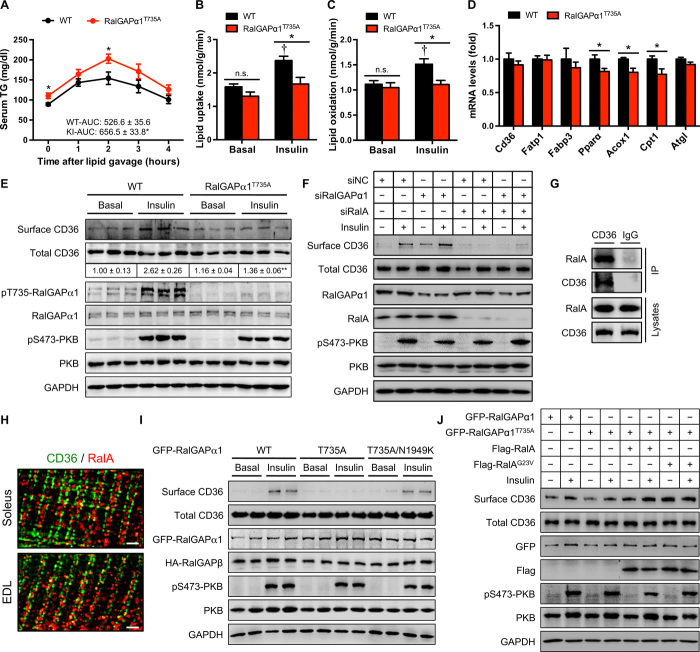

The RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation inhibits muscle lipid uptake and oxidation but does not affect hepatic output of TG

We next investigated how the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation caused hyperlipidemia in mice. We challenged mice with olive oil through oral gavage and monitored blood TG. RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice had higher levels of TG in their blood, with significant increases of area under the curve (Fig. 3A), suggesting that these animals were unable to efficiently clear blood lipids. Since skeletal muscle plays a critical role in postprandial lipid control, we suspected that muscle lipid uptake and/or oxidation might be impaired in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice. Insulin-stimulated lipid uptake was significantly (~30%) lower in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in muscle than in WT muscle (Fig. 3B). Moreover, insulin could no longer stimulate lipid oxidation in the knock-in muscle in contrast to causing a robust increase in the WT muscle (Fig. 3C). Again, insulin-stimulated LCFA uptake remained normal in primary brown adipocytes from RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (fig. S4B). Secretion of TG-rich very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) from the liver into the blood provides an important source of TG to other tissues such as skeletal muscle. TG in the VLDL has to be hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL) to release FFAs for uptake by skeletal muscle. To examine whether hepatic output of TG might contribute to hyperlipidemia in the knock-in mice, we treated mice with an LPL inhibitor, tyloxapol, and monitored TG levels in the blood. Tyloxapol treatment elevated blood TG to similar levels in the two genotypes despite a higher level of blood TG in the knock-in mice before treatment (fig. S3J), suggesting that hepatic output of TG most likely did not account for hyperlipidemia in knock-in mice. Together, these data show that muscle lipid uptake and oxidation were impaired in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice, which might be the underlying cause for hyperlipidemia in these animals.

Fig. 3. Lipid homeostasis in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice.

(A) Serum TG levels after lipid administration via oral gavage in WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice at the age of 6 months. The values show the TG area under the curve during lipid tolerance test. n = 7 to 8. (B and C) Lipid uptake (B) and oxidation (C) in isolated soleus muscles of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (5 months old) in response to insulin. n = 5. †P < 0.01 (lipid uptake) or P < 0.05 (lipid oxidation) (WT insulin versus WT basal). (D) mRNA levels of key regulators for muscle lipid uptake and oxidation in the gastrocnemius muscle of WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in male mice at the age of 2 months. (E) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in the soleus muscle of male WT and RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (5 months old) in response to insulin. The numbers show the quantitative data of cell surface CD36 that were normalized to total CD36. n = 3. **P < 0.01 (RalGAPα1Thr735Ala insulin versus WT insulin). (F) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in L6 myotubes upon knockdown of RalA and/or RalGAPα1 in response to insulin. Four replicates of this experiment were performed, and representative blots were shown. siNC, small interfering RNA negative control. (G) Coimmunoprecipitation of RalA with CD36 from lysates of L6 myotubes. CD36-containing vesicles were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-CD36 antibody, and RalA was detected in the immunoprecipitates via immunoblotting. IP, immunoprecipitates. (H) Immunostaining of CD36 and RalA in mouse soleus and EDL muscles. Mouse anti-CD36 and rabbit anti-RalA antibodies were used in the immunostaining. Scale bars: 2 μm. (I) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in L6 myotubes overexpressing WT or mutant green fluorescent protein (GFP)–RalGAPα1 proteins in response to insulin. HA-RalGAPβ, hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged RalGAPβ. (J) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in L6 myotubes overexpressing WT or mutant GFP-RalGAPα1 proteins in the presence or absence of overexpression of WT or mutant Flag-RalA proteins. Cells were stimulated with or without insulin. Four replicates of this experiment were performed, and representative blots were shown. Quantitative data of cell surface CD36 that were normalized to total CD36 were shown in fig. S5G. Data are given as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation regulates CD36 translocation via RalA in skeletal muscle in response to insulin

We next studied the molecular mechanism by which the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation inhibited muscle lipid uptake and oxidation. Uptake of lipids into skeletal muscle is the first rate-limiting step for lipid oxidation, and the mRNA levels of key regulators for muscle lipid uptake such as Cd36, Fatp1, and Fabp3 were normal in the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in skeletal muscle (Fig. 3D). The protein level of the fatty acid translocase CD36, the major transporter mediating muscle lipid uptake, was also normal in the knock-in muscle (Fig. 3E). Similar to GLUT4, CD36 is translocated from intracellular vesicular compartments onto the plasma membrane of muscle cells upon insulin stimulation and thus mediates uptake of lipids into skeletal muscle (14). As expected, the cell surface content of CD36 was significantly increased in WT muscle in response to insulin (Fig. 3E). Insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation was greatly inhibited in RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in muscle compared with the corresponding control muscles (Fig. 3E). In contrast, the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation did not affect CD36 levels on the cell surface in BAT (fig. S4C). Lipid uptake is coupled with its oxidation in skeletal muscle through multiple mechanisms including up-regulation of key genes for lipid oxidation (15). In agreement with inhibition of muscle LCFA uptake, we found that mRNA levels of key regulators of lipid oxidation, including Acox1, Cpt1, and Pparα, were significantly decreased in the skeletal muscle of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (Fig. 3D). Together, these data suggest that RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation regulates insulin-stimulated lipid uptake and oxidation in skeletal muscle via control of CD36 translocation.

To gain further insights into how RalGAPα1 and its Thr735 phosphorylation regulate CD36 translocation, we used L6 myotubes that were differentiated from myoblasts. Similar to skeletal muscle, insulin stimulated the translocation of CD36 onto the cell surface in L6 myotubes (Fig. 3F and fig. S5A). Down-regulation of RalGAPα1 via siRNA markedly increased the CD36 content of the cell surface in response to insulin stimulation without altering total CD36 protein levels (Fig. 3F and fig. S5A). When RalA was down-regulated via siRNA, insulin no longer promoted CD36 translocation onto the cell surface in both WT and RalGAPα1-knockdown L6 myotubes (Fig. 3F and fig. S5B). In contrast, knockdown of RalB had no effect on insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation in L6 myotubes (fig. S5C). Furthermore, RalA could be detected on CD36-containing vesicles when they were immunoprecipitated from L6 myotubes (Fig. 3G). Immunostaining of RalA and CD36 showed that these two proteins were partially colocalized in muscle fibers (Fig. 3H). Insulin did not appear to affect the association of RalA with CD36-containing vesicles (fig. S5, D and E). These data show that the RalGAPα1-RalA axis, but not the RalGAPα1-RalB axis, regulates CD36 translocation in skeletal muscle cells.

Overexpression of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutant protein prevented insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation in L6 myotubes (Fig. 3I and fig. S5F), which resembled the inhibitory effect of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation on CD36 translocation in skeletal muscle. Asn1949 is a critical residue for the GAP activity of RalGAPα1, and a lysine substitution of Asn1949 can inactivate this GAP activity (8) and counteract the inhibitory effect of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation on RalA activation in response to insulin (13). This Asn1949Lys substitution also relieved the inhibitory effect of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation on insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation (Fig. 3I). Moreover, overexpression of a constitutively active RalAGly23Val mutant and WT RalA relieved the inhibitory effect of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala mutation on insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation (Fig. 3J and fig. S5G). Together, these data demonstrate that insulin-stimulated RalGAPα1-Thr735 phosphorylation inactivates its GAP activity and promotes CD36 translocation in muscle cells through activation of RalA.

Expression of lipogenic genes is up-regulated in the WAT of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice probably because of systemic signals

The obesity of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice prompted us to investigate whether lipid metabolism is altered in the WAT. To avoid potential complications from obesity, we studied tissues from animals at 2 months of age when RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice were not yet obese (Fig. 1D). Adipogenic genes such as Cebpα and Pparγ and lipolysis gene Atgl were expressed normally, while lipogenic genes such as Fasn and Acc1 were significantly up-regulated in the WAT of knock-in mice (fig. S4D). However, these lipogenic genes were not up-regulated in primary adipocytes isolated from RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice (fig. S4E), suggesting that systemic signals induced expression of these lipogenic genes. In agreement with previous reports (16), we found that OA could induce lipogenic gene expression in primary adipocytes (fig. S4F). Given that RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice had hyperlipidemia before they developed obesity (Fig. 1D and fig. S3G), these data suggest that hyperlipidemia might account for the up-regulation of lipogenic genes in the WAT.

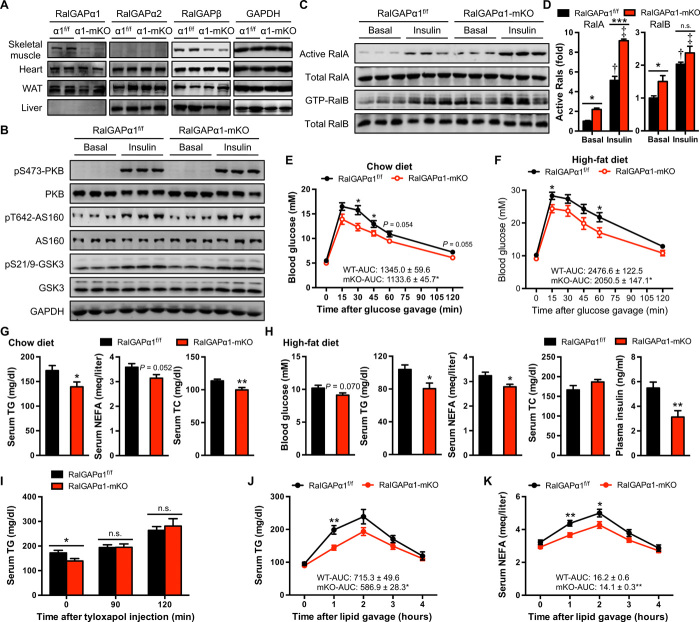

Muscle-specific deletion of RalGAPα1 activates RalA and RalB in skeletal muscle

To further unravel roles of the RalGAPα1-Ral axis in insulin action and resistance in skeletal muscle, we generated a skeletal muscle–specific RalGAPα1 knockout (RalGAPα1-mKO) mouse model through mating RalGAPα1f/f with Mlc1f-Cre mice that express the Cre recombinase in a knock-in manner under the control of the myosin light chain 1f genomic locus (17). As anticipated, RalGAPα1 protein was greatly decreased in skeletal muscle of RalGAPα1-mKO mice but not in other tissues examined, including the BAT, where RalGAPα1 is a minor form (Fig. 4A and fig. S6, A and C). This Mlc1f-Cre was expressed in all types of skeletal muscle examined, including the soleus, extensor digitorum longus (EDL), tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius muscles (fig. S6B), which decreased RalGAPα1 expression in these muscles (Fig. 4A and fig. S6C). RalGAPα1 deficiency caused destabilization of the regulatory subunit RalGAPβ in skeletal muscle (Fig. 4A and fig. S4C). RalGAPα2 protein was expressed at a low level in WT skeletal muscle, and no apparent compensatory change in its expression was observed in RalGAPα1-mKO mice (Fig. 4A). The increased phosphorylation of PKB, and its substrates AS160 and GSK3, in response to insulin in the RalGAPα1-mKO mice was similar to that in the RalGAPα1f/f (WT) littermate controls (Fig. 4B). Active RalA and RalB levels were markedly increased in the RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle under both basal and insulin-stimulated conditions, while total RalA and RalB protein levels remained normal (Fig. 4, C and D, and fig. S6, D and E). In agreement with the proposed role of RalB in the regulation of mTORC1 (12), deletion of RalGAPα1 both activated the mTORC1-S6K axis and increased IRS1-Ser307 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle (fig. S6, F and G). Although RalB was inactivated by an HFD in skeletal muscle, the mTORC1-S6K axis was activated in skeletal muscle of HFD-fed mice (fig. S6, F and G), probably because of activation of mTORC1 by FFAs (18). Moreover, HFD and deletion of RalGAPα1 displayed no additive effects on the activation of the mTORC1-S6K axis and phosphorylation of IRS1-Ser307 (fig. S6, F and G).

Fig. 4. Metabolic phenotype of RalGAPα1-mKO mice.

(A) Expression of RalGAPα1, RalGAPα2, and RalGAPβ in tissues of male RalGAPα1-mKO mice (3 months old). The gastrocnemius muscle was analyzed. (B) Expression and phosphorylation of PKB and its substrates AS160 and GSK3 in the gastrocnemius muscle of male RalGAPα1-mKO mice (3 months old) in response to insulin. (C) GTP-bound active RalA and RalB in the gastrocnemius muscle of male RalGAPα1-mKO mice (3 months old) in response to insulin. (D) Quantitation of active RalA and RalB in the blots shown in (C). n = 3. †P < 0.001 (RalA) or P < 0.001 (RalB) (RalGAPα1f/f insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f basal). ‡P < 0.001 (RalA) or P < 0.01 (RalB) (RalGAPα1-mKO insulin versus RalGAPα1-mKO basal). (E) Oral glucose tolerance test in RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice fed on a chow diet at the age of 5 months. The values show the glucose area under the curve during glucose tolerance test. n = 7 to 8. (F) Oral glucose tolerance test in RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice fed on HFD at the age of 14 weeks. The values show the glucose area under the curve during glucose tolerance test. n = 7. (G) Serum TG, NEFA, and TC in overnight-fasted RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice fed on a chow diet at the age of 4 months. n = 7. (H) Serum TG, NEFA, TC, and insulin in overnight-fasted RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice fed on HFD at the age of 4 months. n = 7 to 8. (I) Serum TG levels in overnight-fasted RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice upon administration of tyloxapol via intraperitoneal injection. n = 7. (J and K) Serum TG (J) and NEFA (K) levels after lipid administration via oral gavage in RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice at the age of 3 to 4 months. The values show the area under the curve during lipid tolerance test. n = 7 to 8. Data are given as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Muscle-specific deletion of RalGAPα1 improves postprandial glycemic and lipid control

We next sought to find out how deletion of RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle affected postprandial glycemic and lipid control. Blood glucose and plasma insulin were normal in RalGAPα1-mKO mice fed with a chow diet (fig. S6H). However, when administered with a bolus of glucose via oral gavage, RalGAPα1-mKO mice cleared blood glucose more quickly than their corresponding WT littermate controls (Fig. 4E). When mice were fed on an HFD, RalGAPα1-mKO mice developed obesity at rates similar to that of WT littermates (fig. S6I). When fed an HFD, RalGAPα1-mKO mice still cleared blood glucose faster than their WT littermates after being challenged with a bolus of glucose (Fig. 4F). Under the HFD condition, RalGAPα1-mKO mice had a moderate decrease in their blood glucose and a significant decrease in their plasma insulin (Fig. 4H).

In contrast to RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice, RalGAPα1-mKO mice had lower fasting blood TG levels than their WT littermates under conditions of both normal chow diet and HFD (Fig. 4, G and H), although they still developed obesity on an HFD. Deletion of RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle also lowered fasting blood FFA in mice on a chow diet and an HFD (Fig. 4, G and H). Again, hepatic output of TG was unlikely to be the underlying cause for low blood lipids in RalGAPα1-mKO mice, since tyloxapol elevated blood TG to similar levels in RalGAPα1-mKO and control mice (Fig. 4I). When administered with an oral load of olive oil, RalGAPα1-mKO mice exhibited an improved ability to control blood lipids, as evidenced by smaller areas under the curve for both blood TG and FFA (Fig. 4, J and K).

Together, these data suggest that the RalGAPα1-RalA axis may have a dominant effect on muscle insulin sensitivity over the RalGAPα1-RalB axis and also demonstrate that deletion of RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle improves postprandial glycemic and lipid control.

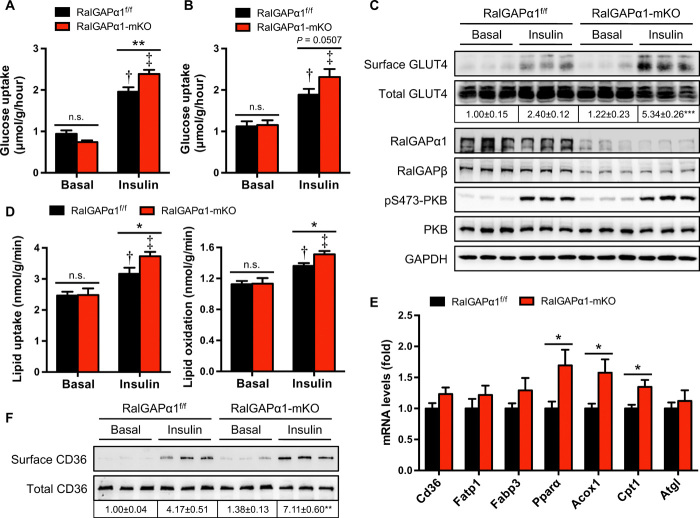

Insulin-stimulated uptake of glucose and LCFAs were enhanced in the RalGAPα1-deficient skeletal muscle

We next examined the impacts of RalGAPα1 deficiency on muscle glucose and lipid metabolism. Under basal conditions, glucose uptake in isolated soleus and EDL muscles displayed no difference between WTs and RalGAPα1 knockouts (Fig. 5, A and B). In both isolated soleus and EDL muscles, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake was ~20% higher in the RalGAPα1 knockouts than in WTs, resulting in a greater insulin response in RalGAPα1-deficient muscle (Fig. 5, A and B). GLUT4 protein was expressed at similar levels in the RalGAPα1-mKO and WT muscle (Fig. 5C). The insulin-stimulated activation of PKB was again comparable between the two genotypes in isolated muscle ex vivo (Fig. 5C). In the basal state, GLUT4 levels on cell surface were comparable in skeletal muscle between WTs and RalGAPα1 knockouts (Fig. 5C), suggesting that RalA activation alone due to RalGAPα1 deficiency was insufficient to promote GLUT4 translocation under basal conditions. Other factors such as AS160 might contribute to intracellular retention of GLUT4 in RalGAPα1-deficient skeletal muscle under basal conditions (19). After insulin stimulation, cell surface GLUT4 contents were higher in the RalGAPα1-deficient muscle than in the WT muscle (Fig. 5C). In agreement with intact RalGAPα1 expression in the BAT of RalGAPα1-mKO mice (fig. S6C), insulin-stimulated RalA activation in the BAT and glucose uptake in primary brown adipocytes were both normal in the RalGAPα1-mKO mice (fig. S6, J to L).

Fig. 5. Muscle glucose and lipid metabolism in RalGAPα1-mKO mice.

(A and B) Glucose uptake in soleus (A) or EDL (B) muscles ex vivo in response to insulin. Muscles were isolated from male RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO mice (4 months old). n = 5 to 8. †P < 0.001 (RalGAPα1-mKO insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f insulin). (C) Cell surface and total GLUT4 levels in the soleus muscle of female RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. The numbers show the quantitative data of cell surface GLUT4 that were normalized to total GLUT4. n = 3. ***P < 0.001 (RalGAPα1-mKO insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f insulin). (D) Lipid uptake and oxidation in the soleus muscle isolated from female RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO mice (3 months old) in response to insulin. n = 5. †P < 0.05 (lipid uptake, RalGAPα1f/f insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f basal) or P < 0.01 (lipid oxidation, RalGAPα1f/f insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f basal). ‡P < 0.001 (lipid uptake and oxidation, RalGAPα1-mKO insulin versus RalGAPα1-mKO basal) *P < 0.05. (E) mRNA levels of key regulators for muscle lipid uptake and oxidation in the gastrocnemius muscle of RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO male mice at the age of 2 months. n = 6. *P < 0.05. (F) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in the soleus muscle of female RalGAPα1f/f and RalGAPα1-mKO mice (4 months old) in response to insulin. The numbers show the quantitative data of cell surface CD36 that were normalized to total CD36. n = 3. **P < 0.01 (RalGAPα1-mKO insulin versus RalGAPα1f/f insulin).

Similar to muscle glucose uptake, insulin-stimulated LCFA uptake was significantly higher in RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle than in the corresponding WT control (Fig. 5D). In parallel, insulin-stimulated lipid oxidation was also augmented in the RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle (Fig. 5D). Again, insulin-stimulated LCFA uptake remained normal in primary brown adipocytes from RalGAPα1-mKO mice (fig. S6M). The mRNA levels of key regulators for muscle lipid uptake, namely, Cd36, Fatp1, and Fabp3, were unchanged in the RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle as compared to their corresponding control tissues (Fig. 5E). Moreover, CD36 protein levels were also normal in RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle (Fig. 5F). As expected, cell surface CD36 contents were significantly increased in the WT muscle in response to insulin (Fig. 5F). Insulin-stimulated CD36 translocation was markedly increased in the RalGAPα1-deficient skeletal muscle as compared with the corresponding control muscles (Fig. 5F). The mRNA levels of key regulators for muscle lipid oxidation, namely, Acox1, Cpt1, and Pparα, were up-regulated in the RalGAPα1-mKO skeletal muscle, as compared to their corresponding control tissues (Fig. 5E), which was probably due to the increase of muscle lipid uptake.

Together, these data show that increases in insulin-stimulated muscle uptake of glucose and LCFAs may account for the improvements of postprandial glycemic and lipid control in RalGAPα1 muscle-specific knockout mice.

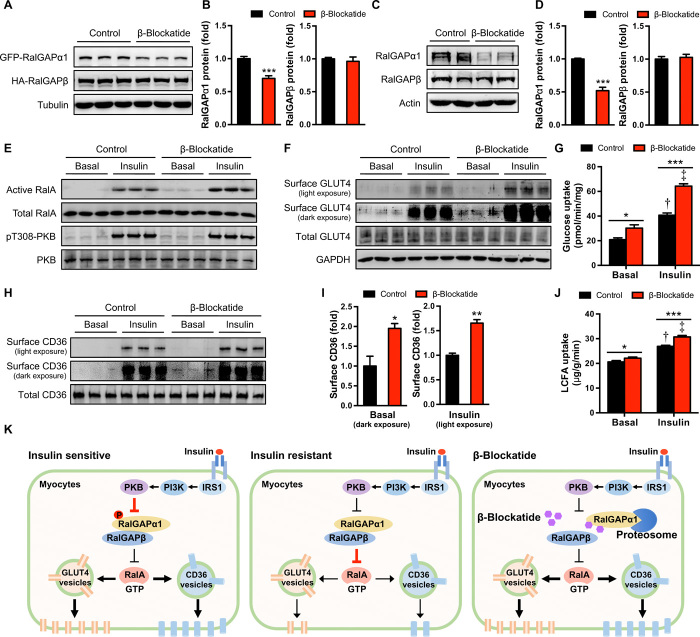

A RalGAPβ-derived peptide could eliminate RalGAPα1 and improve insulin sensitivity in muscle cells

We next sought to develop a peptide blockade to interfere with RalGAPα1 for improving insulin sensitivity in muscle cells. The RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ subunits form a protein complex to exert its GAP function. We therefore postulated that certain RalGAPβ-derived peptide(s) might block formation of the RalGAPα1/β complex. To this end, we first mapped the region(s) on RalGAPα1 that interacts with RalGAPβ and identified two regions on RalGAPα1, namely, M1-T589 and Q1755-End (fig. S7, A to D). RalGAPα1M1-T589 and RalGAPα1Q1755-End fragments interacted with RalGAPβA953-T1158 when they were coexpressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (fig. S7, E and F). In contrast, RalGAPβV1159-End did not interact with RalGAPα1M1-T589 and RalGAPα1Q1755-End fragments, whereas RalGAPβE1121-End could bind to these two fragments (fig. S7, E to H). These data suggest that RalGAPβE1121-T1158 mediates the interaction of this protein with RalGAPα1. When RalGAPβE1121-T1158 was coexpressed with full-length green fluorescent protein (GFP)–RalGAPα1 and HA-RalGAPβ in HEK293 cells, it decreased protein levels of GFP-RalGAPα1 but not of HA-RalGAPβ (Fig. 6, A and B). We therefore named this RalGAPβE1121-T1158 β-blockade peptide (shorted to β-blockatide). Moreover, expression of β-blockatide also diminished endogenous RalGAPα1 but not RalGAPβ in L6 myotubes without affecting their mRNA levels (Fig. 6, C and D, and fig. S8A). The β-blockatide–induced decrease of RalGAPα1 was dependent on the proteasomal degradation pathway and was prevented by the proteasome inhibitor N-carbobenzyloxy-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucinal (fig. S8, B and C). Furthermore, β-blockatide could disrupt the interaction between RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ (fig. S8, B and D). Expression of β-blockatide enhanced insulin-stimulated RalA activation and translocation of GLUT4 and CD36 in L6 myotubes (Fig. 6, E, F, H, and I). Moreover, expression of β-blockatide significantly increased uptake of glucose and LCFAs in L6 myotubes in response to insulin stimulation (Fig. 6, G and J).

Fig. 6. Uptake of glucose and LCFAs in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide.

(A and B) Protein levels of GFP-RalGAPα1 and HA-RalGAPβ in HEK293 cells expressing the β-blockatide. Representative blots are shown in (A), and quantitative data are shown in (B). Cells transfected with an empty vector were used as control. n = 6. (C and D) Protein levels of endogenous RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide. Representative blots are shown in (C), and quantitative data are shown in (D). Cells transfected with an empty vector were used as control. n = 7. (E) GTP-bound active RalA in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide in response to insulin. (F) Cell surface and total GLUT4 levels in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide in response to insulin. (G) Glucose uptake in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide in response to insulin. n = 6. †P < 0.001 (vector control insulin versus vector control basal) and ‡P < 0.001 (β-blockatide insulin versus β-blockatide basal). (H and I) Cell surface and total CD36 levels in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide in response to insulin. Quantitative data of cell surface CD36 that were normalized to total CD36 were shown in (I), in which basal surface CD36 levels were quantified using dark exposure and insulin-stimulated surface CD36 levels were quantified using light exposure. n = 3. (J) Uptake of LCFAs (BODIPY 558/568 C12) in L6 myotubes expressing the β-blockatide in response to insulin. n = 6. †P < 0.001 (vector control insulin versus vector control basal) and ‡P < 0.001 (β-blockatide insulin versus β-blockatide basal). (K) A working model for the RalGAPα1/β complex as a key node in muscle insulin signaling. In insulin-sensitive muscles, insulin can inactivate the RalGAPα1/β complex via phosphorylation of RalGAPα1, thereby resulting in activation of RalA. The latter can then increase muscle uptake of glucose and LCFAs via promoting translocation of GLUT4 and CD36. In insulin-resistant muscles, the nonphosphorylated RalGAPα1/β complex is elevated and inactivates RalA, which consequently inhibits muscle uptake of glucose and LCFAs. The β-blockatide can disrupt the RalGAPα1/β complex and cause proteasomal degradation of RalGAPα1, which consequently increases muscle insulin sensitivity. PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Data are given as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our findings shed light on how RalGAPα1 functions as a critical node in insulin signaling to participate in insulin action and resistance in skeletal muscle. Our results demonstrate that RalGAPα1 is critical for insulin action in skeletal muscle and are consistent with a model in which phosphorylation of RalGAPα1-Thr735 by PKB controls whole-body glucose and lipid homeostasis at least in part through regulating insulin-governed muscle uptake of glucose and LCFAs via RalA (Fig. 6K). Elevation of nonphosphorylated RalGAPα1 contributes to the development of muscle insulin resistance induced by HFDs, and targeting RalGAPα1 may be a promising strategy to improve muscle insulin sensitivity.

In the current view, serine phosphorylation of IRS is central for the development of insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity (6). The up-regulation of nonphosphorylated RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle of HFD-induced obese mice may represent a previously unidentified mechanism for muscle insulin resistance, which is complementary to the IRS-centric mechanism. In this scenario, the HFD-induced up-regulation of nonphosphorylated RalGAPα1 results in inactivation of RalA, which consequently renders skeletal muscle unable to absorb glucose and LCFAs in response to insulin. The inhibitory effect on insulin action exerted by the obesity-driven RalGAPα1-RalA axis may overwhelm the opposing effect of the RalGAPα1-RalB axis to alleviate feedback regulation of IRS, tipping the balance toward dampening glucose and LCFA uptake into skeletal muscle in diet-induced obesity. Furthermore, fatty acids can activate a number of kinases, including mTOR, S6K, JNK, and PKC, to phosphorylate IRS serine residues (6), which also counteract the alleviating effect of RalB inactivation by induction of RalGAPα1 in obesity. Thus, the RalGAPα1-RalA axis may play a critical role in the development of diet-induced insulin resistance, while the RalGAPα1-RalB axis may only have a marginal effect on HFD-induced IRS serine phosphorylation. This notion is supported by our observation of improved postprandial glucose and lipid control in the RalGAPα1-mKO mice under HFD conditions. Skeletal muscle has been emerging as an important player in regulating whole-body metabolic homeostasis in recent years, although its potential for treatment of metabolic diseases has not been fully appreciated (3, 20, 21). Lack of suitable molecular targets impedes the development of drugs targeting skeletal muscle to treat metabolic diseases. Our findings therefore provide a conceptual demonstration that RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle might be a possible target for antidiabetic drugs. Overload of LCFAs in skeletal muscle can lead to serine phosphorylation of IRS and cause insulin resistance (22, 23). The position of RalGAPα1 in insulin signaling endows its inactivation as a potential therapeutic strategy with a unique dual-action feature. Inactivation of RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle can decouple LCFA uptake and serine phosphorylation of IRS from lipid inhibition of insulin action on muscle glucose uptake and thus simultaneously improve postprandial glucose and lipid control. Our β-blockatide may be used as a prototype for the development of small molecules to target RalGAPα1 for improving muscle insulin sensitivity. It is currently unclear why overload of LCFAs in muscle cells increases protein levels of the RalGAPα1/β complex, which deserves further investigations of translational/posttranslational effects and protein stability in the future.

In contrast to the RalGAPα1/β complex being dominant in skeletal muscle, RalGAPα2/β is the major complex in the WAT (13) and in the BAT (this study). A recent study shows that adipose tissue–specific deletion of RalGAPβ results in activation of RalA in both WAT and BAT (24). Deletion of RalGAPβ in the adipose tissues protects mice from development of metabolic disease due to increased glucose uptake into the BAT (24). These studies highlight the importance of both RalGAPα1/β and RalGAPα2/β complexes in metabolic health, although they function in distinct tissues. The evolution of these two protein complexes may diversify regulatory mechanisms for metabolic control in different tissues through RalA.

AS160 is another known regulator of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 trafficking (25). It is a functional GAP for Rab small GTPase and mediates intracellular retention of GLUT4. AS160 can be phosphorylated by PKB on its Thr642 site, which inhibits its GAP activity and consequently promotes GLUT4 translocation in response to insulin. Similar to the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mutation, an AS160Thr642Ala knock-in mutation also impairs insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation and causes muscle insulin resistance in mice (26). Despite these similarities, these two knock-in mice display some distinct metabolic phenotypes. RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice developed hyperlipidemia, obesity, and NAFLD even on a normal chow diet. In contrast, AS160Thr642Ala knock-in mice have normal blood lipid levels and body weight (26). Moreover, unlike the RalGAPα1 deletion that improved glycemic control in mice, AS160 deletion in mice or null mutation in human patients causes insulin resistance due to an effect in decreasing GLUT4 protein levels in skeletal muscle (20, 21, 27, 28). More needs to be done in the future to get a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the different metabolic changes caused by mutations of RalGAPα1 and AS160.

GAPs and guanine nucleotide exchangers (GEFs) are critical upstream regulators of their target small G proteins and can also be downstream effectors of small G proteins, thus forming small G protein cascades (29). For instance, the active GTP-bound Rab10 can bind to the RalA GEF RalGDS-like factor (Rlf) and increase its activity in adipocytes. Consequently, Rlf promotes RalA to become a GTP-loaded active form that mediates glucose uptake into the adipocytes in response to insulin (30). There are seven RalA GEFs in humans (31), and it is currently unknown which one of them mediates insulin-stimulated RalA activation in skeletal muscle. Knockout of RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle does not result in a full activation of RalA in the basal state, suggesting that such a RalA GEF might also be regulated by insulin in skeletal muscle. Rab8a has recently been identified as a critical regulator for the translocation of GLUT4 and CD36 in skeletal muscle cells (3, 32). Therefore, an intriguing question is whether a small G protein cascade involving Rab8a and RalA exists to regulate translocation of GLUT4 and CD36 in skeletal muscle.

Exercise has been widely used as an antidiabetic therapeutic, whose beneficial effect is in part mediated by up-regulation of glucose utilization in skeletal muscle (33). Exercise-induced energy stress can activate the energy sensor adenosine 5′-monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) that consequently regulates GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (34, 35). Chemical AMPK activators such as the antidiabetic drug metformin and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR) can also stimulate muscle glucose uptake via promoting GLUT4 translocation (36, 37). TBC1D1 is a RabGAP that can be phosphorylated on its Ser231 by AMPK (38). TBC1D1-Ser231 phosphorylation mediates AICAR-induced GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle but is dispensable for exercise-induced muscle glucose utilization (39). How AMPK regulates exercise-induced muscle glucose uptake is still not clear. RalGAPα1 can also be phosphorylated in response to exercise/muscle contraction (13). Given the critical role of RalGAPα1 in insulin-stimulated muscle glucose utilization, it would be intriguing to find out whether it might mediate the beneficial effects of exercise and metformin through controlling GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Exercise can also enhance fatty acid utilization in skeletal muscle via promoting CD36 translocation (40), which raises a further interesting question of whether RalGAPα1 is involved in exercise-induced CD36 translocation in skeletal muscle. Although AMPK mediates the beneficial effects of exercise on metabolic control, chronic activation of AMPK with an AMPK activator MK-8722 causes cardiac hypertrophy in rodents and monkeys (41). Therefore, it would be interesting to find out whether RalGAPα1 might regulate cardiac function and whether the β-blockatide might interfere with cardiac performance.

In summary, we demonstrate that RalGAPα1 is a critical node in muscle insulin signaling and plays an important role in the development of muscle insulin resistance. RalGAPα1 in skeletal muscle may be a possible therapeutic target for simultaneous improvement of postprandial glucose and lipid control in T2D.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant human insulin was bought from Novo Nordisk (Denmark). HFD (60 kcal% fat; catalog no. 12492) was bought from Research Diets (USA). Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin, NeutrAvidin Agarose, and protein molecular markers were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). Protein G Sepharose was from GE Healthcare (UK). 2-deoxy-d-[1,2-3H(N)]glucose, d-[1-14C]-mannitol, and [14C(U)]-palmitic acid were from PerkinElmer (USA). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich or Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The antibodies are listed in table S1. Rabbit anti-CD36 was used for immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation, while mouse anti-CD36 was used for immunostaining. The pThr735-RalGAPα1 antibody was originally produced using a pThr715 peptide derived from RalGAPα2 as described previously (9) and provided by X. Chen (Peking University, China).

Molecular biology

Cloning, fragmentation, and point mutation of the mouse RalGAPα1, RalGAPβ, and RalA were carried out using standard procedures. All DNA constructs were sequenced by Life Technologies (Shanghai, China).

Generation of RalGAPα1Thr735Ala, RalGAPα1f/f, and muscle-specific RalGAPα1 knockout mice

RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice on a C57BL/6J background were generated using the strategy outlined in fig. S3A by the transgenic facility at Nanjing University, in which the Thr735 (the surrounding sequence is PMRQRSAtTTGSPGT; Thr735 is shown in lower case bold) on RalGAPα1 was changed to alanine via knock-in mutagenesis. The RalGAPα1 knockout-first embryonic stem cells (cell line: JM8A3.N1; clone: EPD0573_2_A12) were purchased from the Knockout Mouse Project Repository (University of California Davis, USA) and used for blastocyst injection to generate RalGAPα1f/f mice. The sixth exon of RalGAPα1 was flanked by two loxP sites in RalGAPα1f/f mice that were backcrossed to C57BL/6J background for at least five generations before the experiments. RalGAPα1f/f mice were mated with Mlc1f-Cre mice on a C57BL/6J background to obtain skeletal muscle–specific RalGAPα1 knockout (RalGAPα1-mKO) mice.

Mouse breeding and husbandry

The animal facility at Nanjing University is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The Ethics Committee at Nanjing University approved all animal studies and protocols. Mice were raised under a light/dark cycle of 12 hours and had free access to food and water unless stated. Mating of RalGAPα1f/f with RalGAPα1f/f–Mlc1f-Cre generated RalGAPα1f/f (control mice) and RalGAPα1f/f–Mlc1f-Cre (RalGAPα1-mKO) mice. As for RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice, Het × Het mating was set up to generate homozygous knock-ins and WT littermates. RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice were genotyped via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primers: 5′-CCTCTGCCCTAAGTGTAACTG-3′ and 5′-TGAGGCTTTGTGGGCTGCTA-3′. Genotyping of RalGAPα1f/f mice was performed using the following primers: 5′-GAGATGGCGCAACGCAATTAATG-3′ and 5′-GGCTGCAAAGAGTAGGTAAAGTGCC-3′. The Cre mice were genotyped using the following primers: 5′-GCCTGCATTACCGGTCGATGC-3′ and 5′-CAGGGTGTTATAAGCAATCCC-3′.

Blood chemistry

Blood glucose was measured using a Breeze2 glucometer (Bayer). Serum FFA, TG, and TC were measured using the Wako LabAssay NEFA kit (catalog no. 294-63601), LabAssay Triglyceride kit (catalog no. 290-63701), and LabAssay Cholesterol kit (catalog no. 294-65801) (Wako Chemicals, USA), respectively.

Oral glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test

Oral glucose tolerance test was carried out in mice deprived of food overnight (16 hours). A bolus of glucose (1.5 mg/g) was administered via oral gavage, and mice were tail-bled for measurement of blood glucose using a Breeze2 glucometer. As for insulin tolerance test, mice were intraperitoneally injected with insulin (0.75 mU/g) after being restricted from food access for 4 hours, and blood glucose was subsequently determined through tail bleeding.

Measurement of liver TG and TC

Liver TG was measured through determination of its glycerol contents, as previously described (42). Briefly, saponification of frozen liver chunks was carried out in ethanolic KOH to release free glycerol that was measured using the Free Glycerol Reagent (catalog no. F6428, Sigma-Aldrich). For liver TC measurement, lipids were first extracted using an organic solvent consisting of chloroform:isopropanol:NP-40 (7:11:0.1). After removal of the organic solvent, TC in the extracts was then determined using the LabAssay Cholesterol kit (catalog no. 294-65801, Wako Chemicals, USA).

Muscle incubation and glucose uptake ex vivo

Muscle glucose uptake was carried out in isolated soleus or EDL muscles, as previously described (26). Briefly, isolated soleus or EDL muscles were stimulated with or without insulin for 50 min and then incubated in Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate (KRB) buffer containing 2-deoxy-d-[1,2-3H(N)]glucose and d-1-[14C]mannitol for another 10 min with or without insulin. After incubation, the uptake assay was terminated in ice-cold KRB buffer containing cytochalasin B, and muscles were blotted dry, weighed, and lysed. 3H and 14C radioisotopes in muscle lysates were subsequently measured using a Tri-Carb 2800TR scintillation counter (PerkinElmer) for calculation of muscle glucose uptake.

Glucose uptake in primary adipocytes and L6 myotubes

Glucose uptake was carried out in primary adipocytes and L6 myotubes, as previously described (20). Briefly, cells were deprived of serum and then treated with or without insulin for 30 min. Glucose uptake was carried out in Hepes-buffered saline buffer containing 2-deoxy-d-[1,2–3 H(N)]glucose in the presence or absence of insulin for 10 min. Radioisotopes in cell lysates were measured using the Tri-Carb 2800TR scintillation counter for calculation of glucose uptake rates.

Lipid uptake and oxidation

Lipid uptake and oxidation in isolated soleus was measured, as previously described (3). Briefly, the soleus muscle was isolated and stimulated with or without insulin for 30 min. After insulin stimulation, the soleus muscle was incubated in KRB buffer (±insulin) containing 14C-palmitic acid for 50 min. At the completion of incubation, 14C radioisotopes within muscles were determined using the Tri-Carb 2800TR scintillation counter. After removal of muscle, perchloric acid (0.6 M) was added into incubation media to evolve gaseous 14CO2 that was subsequently trapped in benzethonium hydroxide–soaked filters and determined by scintillation counting. Muscle lipid oxidation was calculated using the radioactivity in gaseous 14CO2. Muscle lipid uptake was calculated using the sum of radioactivity in muscle and gaseous 14CO2.

Lipid uptake in primary adipocytes and L6 myotubes was measured as previously described with modifications (43). Briefly, cells were stimulated with or without insulin for 30 min. After insulin stimulation, cells were incubated in KRB buffer (±insulin) containing BODIPY 558/568 C12 (D-3835, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. At the completion of incubation, BODIPY 558/568 C12 in cell lysates was determined using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek Instruments Inc.).

Measurements of cell surface GLUT4 and CD36

GLUT4 and CD36 on the cell surface were determined via a modified biotinylation method described previously (3). Briefly, isolated soleus muscle or L6 myotubes were stimulated with or without insulin for 50 min and then incubated in KRB buffer (±insulin) containing Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (1 mg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min. After biotinylation of cell surface proteins, the soleus muscle or L6 myotubes were rinsed with 50 mM tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) twice to remove free Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin. After lysis, tissue/cell lysates were incubated with NeutrAvidin Agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C overnight. After incubation, the beads were washed three times with the ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline buffer containing 1% NP-40 to remove nonspecific binding proteins. Afterward, biotinylated cell surface proteins were eluted in SDS sample buffer at room temperature for 30 min and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. Biotinylated GLUT4 and CD36 were detected using corresponding specific antibodies.

Cell culture, transfection, and lysis

HEK293 cells were purchased from the Cell Resource Center, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (China). Rat L6 myoblasts were provided by A. Klip (University of Toronto, Canada). HEK293 cells and L6 myoblasts were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination. L6 myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes, as previously described (38). Transfection of HEK293 cells or L6 myotubes with plasmid DNA or siRNA was performed using a Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two days after transfection, cells were lysed, as previously described (42).

Primary white preadipocytes were isolated, cultured, and differentiated into white adipocytes, as previously described (20). Primary brown preadipocytes were isolated, cultured, and differentiated into brown adipocytes, as previously described (44).

Measurements of GTP-bound form of RalA and RalB

Levels of GTP-bound form of RalA or RalB were measured via a pull-down assay, as previously described (13). Briefly, mouse tissues or L6 muscle cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, leupeptin (1 μg/ml), pepstatin (1 μg/ml), and aprotinin (1 μg/ml)]. Purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase–Sec5N (1 to 120 amino acids) protein was immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads and incubated with tissue/cell lysates at 4°C for 1 hour. After removal of nonspecific binding proteins via intensive washing of resins, the active RalA or RalB that was bound to Sec5N was eluted off from the resins in SDS sample buffer and detected via immunoblotting.

Tissue lysis and protein measurement

Mouse tissues were harvested, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized, as previously described (26). Protein contents of tissue lysates were determined using Bradford reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitation of target proteins was performed, as previously described (42). Briefly, tissue or cell lysates were incubated with the antibody-coupled protein G Sepharose or GFP-binder (ChromoTek GmbH, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany) at 4°C overnight. After intensive washing to remove nonspecific binding proteins, immunoprecipitates were eluted in SDS sample buffer (42).

As for immunoprecipitation of CD36-containing vesicles, L6 myotubes were lysed in a detergent-free lysis buffer via passing through a 22-gauge needle (12 times) and a 27-gauge needle (6 times). Unbroken cells were removed via centrifugation at 500g for 10 min. Plasma membrane, mitochondria, nuclei, and high-density microsomes were removed via centrifugation at 15,750g for 17 min. Lysates containing low-density microsomes were incubated with rabbit anti-CD36 or preimmune immunoglobulin G overnight at 4°C. Afterward, protein G Sepharose was added and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with detergent-free lysis buffer to remove nonspecific binding proteins/low-density microsomes. Immunoprecipitates were then eluted in SDS sample buffer.

Tissue/cell lysates or immunoprecipitates were separated via SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and subjected to immunoblotting assay, as previously described (42). Quantification of immunoblotting signals was carried out using ImageJ and expressed as fold changes. Phosphorylation signals were normalized with corresponding total proteins.

Immunofluorescence staining and imaging

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out, as previously described (3). Briefly, paraformaldehyde-fixed muscle fibers were sequentially probed with primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor–conjugated or Cy3/Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were taken with a Leica confocal microscope. Colocalization of CD36 and RalA was assessed via Manders’ overlap coefficient (R) using Image-Pro Plus software.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out to measure expression levels of target genes using an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus system. The primers for real-time quantitative PCR are listed in table 2.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as means ± SEM. Comparisons were performed via t test for two groups or via two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple groups using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. MacKintosh (University of Dundee, UK) for proofreading the manuscript and members of the resource unit at Nanjing University for technical assistance. Funding: Thanks to the Ministry of Science and Technology of China [grant nos. 2014CB964704 (the National Basic Research Program of China) and 2014BAI02B01 (the National Science and Technology Support Project)], the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31671456 and 31571211), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China [grant no. BK20161393 (Basic Research Program)] for financial support. Author contributions: Q.L.C., P.R., S.S.Z., X.Y.Y., Q.O.Y., and S.C. performed experiments, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript. H.Y.W. reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.C. designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. S.C. is the guarantor of this study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/4/eaav4116/DC1

Table S1. The list of antibodies used in this study.

Table S2. Primer information for quantitative real-time fluorescence PCR analysis of expression of target genes.

Fig. S1. Specificity of the pT735-RalGAPα1 antibody.

Fig. S2. Effects of HFD/fatty acids on the RalGAPα1/β complex and RalA/B activities in skeletal muscle and L6 myotubes.

Fig. S3. Generation and characterization of the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice.

Fig. S4. Uptake of glucose and LCFAs and expression of genes for lipid metabolism in adipose tissues and primary adipocytes.

Fig. S5. Cell surface and total CD36 in L6 myotubes.

Fig. S6. Characterization of RalGAPα1-mKO mice.

Fig. S7. Mapping of interaction domains on RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ.

Fig. S8. Expression, degradation, and interaction of RalGAPα1 and RalGAPβ in L6 myotubes expressing β-blockatide.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.DeFronzo R. A., Ferrannini E., Groop L., Henry R. R., Herman W. H., Holst J. J., Hu F. B., Kahn C. R., Raz I., Shulman G. I., Simonson D. C., Testa M. A., Weiss R., Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15019 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz L. D., Glickman M. G., Rapoport S., Ferrannini E., DeFronzo R. A., Splanchnic and peripheral disposal of oral glucose in man. Diabetes 32, 675–679 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q., Rong P., Xu D., Zhu S., Chen L., Xie B., Du Q., Quan C., Sheng Y., Zhao T.-J., Li P., Wang H. Y., Chen S., Rab8a deficiency in skeletal muscle causes hyperlipidemia and hepatosteatosis by impairing muscle lipid uptake and storage. Diabetes 66, 2387–2399 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S., Synowsky S., Tinti M., MacKintosh C., The capture of phosphoproteins by 14-3-3 proteins mediates actions of insulin. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 429–436 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blenis J., TOR, the gateway to cellular metabolism, cell growth, and disease. Cell 171, 10–13 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czech M. P., Insulin action and resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med. 23, 804–814 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoki K., Li Y., Xu T., Guan K.-L., Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 17, 1829–1834 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shirakawa R., Fukai S., Kawato M., Higashi T., Kondo H., Ikeda T., Nakayama E., Okawa K., Nureki O., Kimura T., Kita T., Horiuchi H., Tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex-like complexes act as GTPase-activating proteins for Ral GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21580–21588 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X.-W., Leto D., Xiong T., Yu G., Cheng A., Decker S., Saltiel A. R., A Ral GAP complex links PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling to RalA activation in insulin action. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 141–152 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X. W., Leto D., Chiang S. H., Wang Q., Saltiel A. R., Activation of RalA is required for insulin-stimulated Glut4 trafficking to the plasma membrane via the exocyst and the motor protein Myo1c. Dev. Cell 13, 391–404 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nozaki S., Ueda S., Takenaka N., Kataoka T., Satoh T., Role of RalA downstream of Rac1 in insulin-dependent glucose uptake in muscle cells. Cell. Signal. 24, 2111–2117 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin T. D., Chen X. W., Kaplan R. E., Saltiel A. R., Walker C. L., Reiner D. J., Der C. J., Ral and Rheb GTPase activating proteins integrate mTOR and GTPase signaling in aging, autophagy, and tumor cell invasion. Mol. Cell 53, 209–220 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q., Quan C., Xie B., Chen L., Zhou S., Toth R., Campbell D. G., Lu S., Shirakawa R., Horiuchi H., Li C., Yang Z., MacKintosh C., Wang H. Y., Chen S., GARNL1, a major RalGAP α subunit in skeletal muscle, regulates insulin-stimulated RalA activation and GLUT4 trafficking via interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. Cell. Signal. 26, 1636–1648 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koonen D. P. Y., Glatz J. F. C., Bonen A., Luiken J. J. F. P., Long-chain fatty acid uptake and FAT/CD36 translocation in heart and skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1736, 163–180 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maples J. M., Brault J. J., Witczak C. A., Park S., Hubal M. J., Weber T. M., Houmard J. A., Shewchuk B. M., Differential epigenetic and transcriptional response of the skeletal muscle carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B (CPT1B) gene to lipid exposure with obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 309, E345–E356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanting C., Yang Q. Y., Ma G. L., Du M., Harrison J. H., Block E., Dose- and type-dependent effects of long-chain fatty acids on adipogenesis and lipogenesis of bovine adipocytes. J. Dairy Sci. 101, 1601–1615 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bothe G. W. M., Haspel J. A., Smith C. L., Wiener H. H., Burden S. J., Selective expression of Cre recombinase in skeletal muscle fibers. Genesis 26, 165–166 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang Y., Vilella-Bach M., Bachmann R., Flanigan A., Chen J., Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science 294, 1942–1945 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eguez L., Lee A., Chavez J. A., Miinea C. P., Kane S., Lienhard G. E., McGraw T. E., Full intracellular retention of GLUT4 requires AS160 Rab GTPase activating protein. Cell Metab. 2, 263–272 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie B., Chen Q., Chen L., Sheng Y., Wang H. Y., Chen S., The inactivation of RabGAP function of AS160 promotes lysosomal degradation of GLUT4 and causes postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Diabetes 65, 3327–3340 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moltke I., Grarup N., Jørgensen M. E., Bjerregaard P., Treebak J. T., Fumagalli M., Korneliussen T. S., Andersen M. A., Nielsen T. S., Krarup N. T., Gjesing A. P., Zierath J. R., Linneberg A., Wu X., Sun G., Jin X., Al-Aama J., Wang J., Borch-Johnsen K., Pedersen O., Nielsen R., Albrechtsen A., Hansen T., A common Greenlandic TBC1D4 variant confers muscle insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 512, 190–193 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szendroedi J., Yoshimura T., Phielix E., Koliaki C., Marcucci M., Zhang D., Jelenik T., Müller J., Herder C., Nowotny P., Shulman G. I., Roden M., Role of diacylglycerol activation of PKCθ in lipid-induced muscle insulin resistance in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9597–9602 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Copps K. D., Hancer N. J., Opare-Ado L., Qiu W., Walsh C., White M. F., Irs1 serine 307 promotes insulin sensitivity in mice. Cell Metab. 11, 84–92 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skorobogatko Y., Dragan M., Cordon C., Reilly S. M., Hung C.-W., Xia W., Zhao P., Wallace M., Lackey D. E., Chen X.-W., Osborn O., Bogner-Strauss J. G., Theodorescu D., Metallo C. M., Olefsky J. M., Saltiel A. R., RalA controls glucose homeostasis by regulating glucose uptake in brown fat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 7819–7824 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano H., Kane S., Sano E., Miinea C. P., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Garner C. W., Lienhard G. E., Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of a Rab GTPase-activating protein regulates GLUT4 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14599–14602 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S., Wasserman D. H., MacKintosh C., Sakamoto K., Mice with AS160/TBC1D4-Thr649Ala knockin mutation are glucose intolerant with reduced insulin sensitivity and altered GLUT4 trafficking. Cell Metab. 13, 68–79 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H. Y., Ducommun S., Quan C., Xie B., Li M., Wasserman D. H., Sakamoto K., Mackintosh C., Chen S., AS160 deficiency causes whole-body insulin resistance via composite effects in multiple tissues. Biochem. J. 449, 479–489 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lansey M. N., Walker N. N., Hargett S. R., Stevens J. R., Keller S. R., Deletion of Rab GAP AS160 modifies glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in primary skeletal muscles and adipocytes and impairs glucose homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 303, E1273–E1286 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novick P., Regulation of membrane traffic by Rab GEF and GAP cascades. Small GTPases 7, 252–256 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karunanithi S., Xiong T., Uhm M., Leto D., Sun J., Chen X. W., Saltiel A. R., A Rab10:RalA G protein cascade regulates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3059–3069 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentry L. R., Martin T. D., Reiner D. J., Der C. J., Ral small GTPase signaling and oncogenesis: More than just 15 minutes of fame. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 2976–2988 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Y., Bilan P. J., Liu Z., Klip A., Rab8A and Rab13 are activated by insulin and regulate GLUT4 translocation in muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19909–19914 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodyear L. J., The exercise pill—Too good to be true? N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1842–1844 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mu J., Brozinick J. T. Jr., Valladares O., Bucan M., Birnbaum M. J., A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in contraction- and hypoxia-regulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell 7, 1085–1094 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neill H. M., Maarbjerg S. J., Crane J. D., Jeppesen J., Jørgensen S. B., Schertzer J. D., Shyroka O., Kiens B., van Denderen B. J., Tarnopolsky M. A., Kemp B. E., Richter E. A., Steinberg G. R., AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16092–16097 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musi N., Hirshman M. F., Nygren J., Svanfeldt M., Bavenholm P., Rooyackers O., Zhou G., Williamson J. M., Ljunqvist O., Efendic S., Moller D. E., Thorell A., Goodyear L. J., Metformin increases AMP-activated protein kinase activity in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 51, 2074–2081 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorgensen S. B., Viollet B., Andreelli F., Frosig C., Birk J. B., Schjerling P., Vaulont S., Richter E. A., Wojtaszewski J. F., Knockout of the α2 but not α1 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase isoform abolishes 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-4-ribofuranosidebut not contraction-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1070–1079 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S., Murphy J., Toth R., Campbell D. G., Morrice N. A., Mackintosh C., Complementary regulation of TBC1D1 and AS160 by growth factors, insulin and AMPK activators. Biochem. J. 409, 449–459 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q., Xie B., Zhu S., Rong P., Sheng Y., Ducommun S., Chen L., Quan C., Li M., Sakamoto K., MacKintosh C., Chen S., Wang H. Y., A Tbc1d1 Ser231Ala-knockin mutation partially impairs AICAR- but not exercise-induced muscle glucose uptake in mice. Diabetologia 60, 336–345 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McFarlan J. T., Yoshida Y., Jain S. S., Han X.-X., Snook L. A., Lally J., Smith B. K., Glatz J. F. C., Luiken J. J., Sayer R. A., Tupling A. R., Chabowski A., Holloway G. P., Bonen A., In vivo, fatty acid translocase (CD36) critically regulates skeletal muscle fuel selection, exercise performance, and training-induced adaptation of fatty acid oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23502–23516 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers R. W., Guan H.-P., Ehrhart J., Petrov A., Prahalada S., Tozzo E., Yang X., Kurtz M. M., Trujillo M., Gonzalez Trotter D., Feng D., Xu S., Eiermann G., Holahan M. A., Rubins D., Conarello S., Niu X., Souza S. C., Miller C., Liu J., Lu K., Feng W., Li Y., Painter R. E., Milligan J. A., He H., Liu F., Ogawa A., Wisniewski D., Rohm R. J., Wang L., Bunzel M., Qian Y., Zhu W., Wang H., Bennet B., Scheuch L. L. F., Fernandez G. E., Li C., Klimas M., Zhou G., van Heek M., Biftu T., Weber A., Kelley D. E., Thornberry N., Erion M. D., Kemp D. M., Sebhat I. K., Systemic pan-AMPK activator MK-8722 improves glucose homeostasis but induces cardiac hypertrophy. Science 357, 507–511 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L., Chen Q., Xie B., Quan C., Sheng Y., Zhu S., Rong P., Zhou S., Sakamoto K., MacKintosh C., Wang H. Y., Chen S., Disruption of the AMPK-TBC1D1 nexus increases lipogenic gene expression and causes obesity in mice via promoting IGF1 secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 7219–7224 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubikoversuskaya E., Chudnoversuskiy R., Karateev G., Park H. M., Stahl A., Measurement of long-chain fatty acid uptake into adipocytes. Methods Enzymol. 538, 107–134 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun L., Xie H., Mori M. A., Alexander R., Yuan B., Hattangadi S. M., Liu Q., Kahn C. R., Lodish H. F., Mir193b–365 is essential for brown fat differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 958–965 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/4/eaav4116/DC1

Table S1. The list of antibodies used in this study.

Table S2. Primer information for quantitative real-time fluorescence PCR analysis of expression of target genes.

Fig. S1. Specificity of the pT735-RalGAPα1 antibody.

Fig. S2. Effects of HFD/fatty acids on the RalGAPα1/β complex and RalA/B activities in skeletal muscle and L6 myotubes.

Fig. S3. Generation and characterization of the RalGAPα1Thr735Ala knock-in mice.

Fig. S4. Uptake of glucose and LCFAs and expression of genes for lipid metabolism in adipose tissues and primary adipocytes.