Abstract

Background

Lipid‐lowering drugs are widely underused, despite strong evidence indicating they improve cardiovascular end points. Poor patient adherence to a medication regimen can affect the success of lipid‐lowering treatment.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions aimed at improving adherence to lipid‐lowering drugs, focusing on measures of adherence and clinical outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL up to 3 February 2016, and clinical trials registers (ANZCTR and ClinicalTrials.gov) up to 27 July 2016. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We evaluated randomised controlled trials of adherence‐enhancing interventions for lipid‐lowering medication in adults in an ambulatory setting with a variety of measurable outcomes, such as adherence to treatment and changes to serum lipid levels. Two teams of review authors independently selected the studies.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors extracted and assessed data, following criteria outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADEPro.

Main results

For this updated review, we added 24 new studies meeting the eligibility criteria to the 11 studies from prior updates. We have therefore included 35 studies, randomising 925,171 participants. Seven studies including 11,204 individuals compared adherence rates of those in an intensification of a patient care intervention (e.g. electronic reminders, pharmacist‐led interventions, healthcare professional education of patients) versus usual care over the short term (six months or less), and were pooled in a meta‐analysis. Participants in the intervention group had better adherence than those receiving usual care (odds ratio (OR) 1.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.29 to 2.88; 7 studies; 11,204 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). A separate analysis also showed improvements in long‐term adherence rates (more than six months) using intensification of care (OR 2.87, 95% CI 1.91 to 4.29; 3 studies; 663 participants; high‐quality evidence). Analyses of the effect on total cholesterol and LDL‐cholesterol levels also showed a positive effect of intensified interventions over both short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. Over the short term, total cholesterol decreased by a mean of 17.15 mg/dL (95% CI 1.17 to 33.14; 4 studies; 430 participants; low‐quality evidence) and LDL‐cholesterol decreased by a mean of 19.51 mg/dL (95% CI 8.51 to 30.51; 3 studies; 333 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Over the long term (more than six months) total cholesterol decreased by a mean of 17.57 mg/dL (95% CI 14.95 to 20.19; 2 studies; 127 participants; high‐quality evidence). Included studies did not report usable data for health outcome indications, adverse effects or costs/resource use, so we could not pool these outcomes. We assessed each included study for bias using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In general, the risk of bias assessment revealed a low risk of selection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias. There was unclear risk of bias relating to blinding for most studies.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence in our review demonstrates that intensification of patient care interventions improves short‐ and long‐term medication adherence, as well as total cholesterol and LDL‐cholesterol levels. Healthcare systems which can implement team‐based intensification of patient care interventions may be successful in improving patient adherence rates to lipid‐lowering medicines.

Plain language summary

Interventions to improve people's drug‐taking behaviour with lipid‐lowering drugs

Review question

Which interventions help improve people's ability to take lipid‐lowering medications more regularly?

Background

Lipid‐lowering therapy has been shown to decrease the risk of both heart attacks and strokes. However, taking these medications as prescribed has not been as high as one would wish. In the past, several methods have been tried to improve the rate at which people take these lipid‐lowering treatments. Previous Cochrane Reviews have not shown a clear benefit of any particular method. We have updated our review to see if any new methods in this digital age have been tested as ways of improving these rates.

Search

Our search included the 11 studies identified from previous versions in 2004 and 2010. We conducted an updated search of the same electronic databases on 3 February 2016, and we searched clinical trials registers up to 27 July 2016.

Study characteristics

The people included in the studies were adults over 18 years of age in outpatient settings, for whom lipid‐lowering therapy was recommended. We now include 35 studies covering 925,171 participants in this review.

Key results

Of the 35 included studies, 16 compared interventions categorised as 'intensified patient care' versus usual care. These interventions included electronic reminders, pharmacist‐led interventions, and healthcare professional education to help people better remember to take their medications. These types of interventions when compared to standard care demonstrated significantly better adherence rates both over the short term (up to and including six months) as well as the long term (longer than six months). Additionally, cholesterol levels were better over both long‐ and short‐term periods in those offered the intervention, compared to those receiving usual care.

Quality of the evidence

We considered only randomised controlled trials for this review. Given the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to keep participants unaware of which group they were in. However, analysis of other forms of bias indicated that generally the studies were at low risk of bias. We assessed the evidence for the outcomes using the GRADE system, and rated it as high quality for long‐term adherence (more than six months) and for reduction in total cholesterol, and moderate quality for short‐term medication adherence (up to six months) and for LDL‐cholesterol levels. For the outcome total cholesterol levels at less than six months follow‐up, we downgraded the evidence to low quality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table for the comparison of 'intensified patient care' vs 'usual care'.

| Intensified patient care vs usual care | |||||

| Patient or population: People receiving lipid‐lowering medications Setting: Ambulatory Intervention: Intensified patient care Comparison: Usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with Intensified patient care | ||||

| Medication adherence at ≤ 6 months | Study population | OR 1.93 (1.29 to 2.88) | 11,204 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 456 per 1,000 | 618 per 1,000 (519 to 707) | ||||

| Medication adherence at > 6 months | Study population | OR 2.87 (1.91 to 4.29) | 663 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| 705 per 1,000 | 873 per 1,000 (820 to 911) | ||||

| Reduction in LDL‐C at ≤ 6 months (mg/dL) | The mean reduction in LDL‐C at ≤ 6 months (mg/dL) was 0 | The mean reduction in LDL‐C at ≤ 6 months (mg/dL) in the intervention group was 19.51 greater (8.51 greater to 30.51 greater) | ‐ | 333 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 |

| Reduction in total serum cholesterol at ≤ 6 months (mg/dL) | The mean reduction in total serum cholesterol at ≤ 6 mos (mg/dL) was 0 | The mean reduction in total serum cholesterol at ≤ 6 months (mg/dL) in the intervention group was 17.15 greater (1.17 greater to 33.14 greater) | ‐ | 430 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 |

| Reduction in total serum cholesterol at > 6 mos (mg/dL) | The mean reduction in total serum cholesterol at > 6 months (mg/dL) was 0 | The mean reduction in total serum cholesterol at > 6 months (mg/dL) in the intervention group was 17.57 greater (14.95 greater to 20.19 greater) | ‐ | 127 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1Downgraded due to heterogeneity 2Downgraded due to wide confidence interval

Background

Despite compelling evidence about the effectiveness of lipid‐lowering drugs and the introduction of clear guidelines, lipid‐lowering therapy is still underused (Rosenson 2015). Recent recommendations by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association are expected to significantly increase the number of individuals for whom statin therapy is indicated (ACC/AHA Guidelines 2013). Lack of adherence and high rates of discontinuation have been shown to be important factors in failing treatment when looking both at high cholesterol levels and at morbidity in terms of recurrent myocardial infarction (Blackburn 2005; Cheng 2004; Wei 2002).

Description of the condition

High cholesterol is one of the top 10 risk factors that account for more than one‐third of all deaths worldwide (WHO Report 2002). It is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), estimated to cause 18% of CVD and 56% of ischaemic heart disease (WHO Report 2002). There is compelling evidence for the effectiveness of lipid‐lowering drugs in reducing both lipid levels and the risk of heart attacks and strokes (Baigent 2005). Elevated serum concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) and total triglycerides (TRG) are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), whereas high‐density lipoproteins (HDL) or a low TC to HDL ratio appear to be protective. Lipid‐lowering medications (hypolipidaemics) for the treatment of hyperlipidaemia include statins, fibrates and anion‐exchange resins. Statins, in particular, have been shown in large randomised controlled trials to be effective in preventing CHD events and in reducing overall mortality (4S 1994; Athyros 2002a; Downs 1998; LIPID 1998; MRC/BHF 2002; Sacks 1996; Shepherd 1995). Fibrates and anion‐exchange resins achieved reductions in CHD events, but showed a non‐significant increase in non‐coronary mortality (Downs 1998). Statins are therefore recommended as first‐line therapy, whereas fibrates and anion‐exchange resins can be considered as second‐line therapy and also in combination with statins (SIGN 2007).

Recommendations about drug treatments vary from country to country. In the UK, treatment with statins for secondary prevention is indicated in people with clinical evidence of CVD to reduce further ischaemic events. For primary prevention of CVD, lipid‐lowering medication is recommended in asymptomatic adults who have a 20% or greater risk of developing CVD in the next 10 years (NICE 2014; SIGN 2007). A combination of statins, blood pressure‐lowering drugs and low‐dose aspirin is recommended by the World Health Report (WHO Report 2002) for secondary prevention of CVD, as this could cut death and disability rates from CVD by more than 50%. A meta‐analysis confirmed an approximately linear relationship between the absolute reduction in LDL‐cholesterol and the proportional reductions in the incidence of coronary and major vascular events (Baigent 2005). Statin therapy resulted in a 19% proportional reduction in CHD deaths per mmol/L LDL‐cholesterol reduction. It can safely reduce the five‐year incidence of cardiovascular events largely irrespective of the initial lipid profile, relating the absolute benefit mainly to an individual's absolute risk of such events and the absolute reduction in LDL‐cholesterol achieved (Baigent 2005). In England, 7000 myocardial infarctions and 2500 strokes could be avoided each year if individuals at high risk, who are not taking medication, received lipid‐lowering treatment (Primatesta 2000). These figures show the impact of lipid‐lowering drugs on public health and thus the importance of the acceptance of and adherence to medication by the public.

Description of the intervention

Adherence is defined as the extent to which people take medication as prescribed. Since the landmark publication by Sackett 1976, it has been the focus of research over the last three decades (Vermeire 2001). Adherence can either be intentional or non‐intentional, and is determined by a variety of factors such as lack of knowledge, denial, adverse effects, poor memory and adverse attitudes to treatment. Reliable indicators of adherent behaviour have not been found to date and demographic factors such as age, sex or social class have been shown to be poor predictors of adherence (Vermeire 2001). The importance of the person's agreement (Lewis 2003) and the significance of their role within the doctor‐patient relationship have been emphasised, which has led to replacing the term 'compliance' with more patient‐centred synonyms such as 'adherence' and 'concordance' (Lewis 2003; Marinker 1997; Mullen 1997). The treatment of a symptomless condition such as hyperlipidaemia signifies a particular challenge to both doctor and patient. It has been difficult to identify the scope of the problem, as adherence rates from hyperlipidaemia trials show considerable variation, ranging from 37% to 80%, depending on factors such as study population, background morbidity, classes of drugs, duration of follow‐up and adherence‐measuring methods (Tsuyuki 2001). Epidemiological data show that target cholesterol concentrations are achieved in fewer than 50% of people receiving cholesterol‐lowering drugs and that only one in four people continue taking medication in the long term (Benner 2002; Primatesta 2000). Not surprisingly, primary prevention trials appear to have higher discontinuation rates than secondary prevention trials, which indicates a relationship between adherence and awareness of illness (Tsuyuki 2001). This was confirmed in a population‐based study involving elderly people, where 60% of people prescribed a statin for acute coronary syndrome gave up treatment within two years, compared to 75% of those without coronary disease (Jackevicius 2002).

A wide range of interventions to improve adherence to medication have been studied (Brown 2011; Costa 2015). They can focus on the person, the drug regimen, the physician or the health system (delivery of medication). Patient education and empowerment is important, as people adhere less to drugs or treatments if they do not understand why they need to take them (Brown 2011). Simplification of the drug regimen may assist, as adherence is inversely related to the number of drugs the person is taking (Pasina 2014), and especially complex dosing schedules are at risk. Interventions focused on physicians advocate good communication and a patient‐centred approach (Brown 2011), which could include appropriate follow‐up and support. System‐based approaches could include pharmacist involvement and (automated) patient reminder systems.

How the intervention might work

A number of systematic reviews looking at adherence‐enhancing interventions have been published in the Cochrane Library.Nieuwlaat 2014 identified effective ways to improve medication adherence for a variety of medical conditions in widely differing populations. Adherence to short‐term drug treatment was improved by written information, personal phone calls and counselling. For long‐term treatments, no simple intervention and only some complex ones led to some improvement in health outcomes (Nieuwlaat 2014). Schroeder 2004 focused on medications for controlling blood pressure and reported enhanced adherence by reducing the number of daily doses. Patient support and education interventions improved adherence to antiretroviral therapy when targeting practical medication management skills aimed at individuals rather than groups (Rueda 2006). In the treatment of type 2 diabetes, it was concluded that nurse‐led interventions, home aids, diabetes education and pharmacy‐led interventions do not show significant effects (Vermeire 2005). Another review concluded that reminder packaging increased the proportion of people taking their medications, but the effect was not large (Mahtani 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

The indication for prescribing lipid‐lowering drugs has changed substantially over the last 20 years (ACC/AHA Guidelines 2013; Baigent 2005). With evidence to suggest that effectiveness of statins occurs irrespective of initial lipid level, greater numbers of people are being actively prescribed lipid‐lowering agents. Observational studies have shown that adherence to lipid‐lowering drugs is poor, with people taking their medication only 60% of the time in a one‐year period (Avorn 1998). There is strong evidence that adherence diminishes over time in people who are being treated as part of a primary or secondary prevention strategy (Benner 2002; Jackevicius 2002). The consequence of inadequate adherence to lipid‐lowering therapy is substantial. In secondary prevention, inadequate adherence is associated with an increase in recurrent myocardial infarction and all‐cause mortality (Wei 2002). For these reasons, it is important that clinically effective and cost‐effective strategies to improve adherence are found for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in the community. The findings of our review can be integrated into clinical practice guidelines and assist clinicians in making a difference to patient outcomes. This update of previous reviews, published in 2004 and updated in 2010 (Schedlbauer 2004; Schedlbauer 2010), assessed interventions designed to help people take their lipid‐lowering medication in an ambulatory care setting, taking into account new and emerging evidence.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions aimed at improving adherence to lipid‐lowering drugs, focusing on measures of adherence and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), of parallel‐group or cross‐over design, that used individual or cluster randomisation.

Types of participants

All adults (over 18 years of age) who were prescribed lipid‐lowering medication for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in ambulatory care settings.

Types of interventions

Interventions of any type intended to increase adherence to self‐administered lipid‐lowering medication versus usual care or no intervention.

This included, but was not exclusive to, interventions such as:

simplification of drug regimen;

patient education and information;

intensified patient care (increased follow‐up, sending out reminders, etc.);

complex behavioural approaches (increasing motivation by arranging group sessions, giving out rewards, etc.);

decision support systems (computer‐based information systems aimed at support of decision‐making);

administrative improvements (audit, documentation, computers, co‐payments);

large‐scale pharmacy‐led automated telephone intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Methods of measuring adherence continue to be widely variable and remain controversial. We identify three categories of adherence assessment, and have included them in this review:

Indirect measures of adherence (e.g. pill count, prescription refill rate, electronic monitoring);

Subjective measures of adherence (e.g. person's self‐report in diaries, interviews);

Direct measures of adherence (tracer substances in blood or urine).

Secondary outcomes

We have also included the following outcome measures, in addition to adherence measures:

Physiological indicators (e.g. total cholesterol);

Health outcome indications (e.g. quality of life, morbidity, mortality);

Adverse effects;

Implications for costs (impact of intervention on economic outcomes, economic evaluation).

In the literature, physiological indicators, health outcomes and adverse effects have been used as proxy measures for adherence. We included these studies only if those indicators were reported in association with adherence outcomes (see Characteristics of included studies).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Previous searches

The 2010 version of this review included searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 1), MEDLINE (January 2000 to March 2008), Embase (January 1998 to March 2008), PsycINFO (1972 to March 2008) and CINAHL (January 1982 to March 2008). CENTRAL incorporates all controlled trials from Embase and MEDLINE, except in the most recent years. We used an appropriate RCT filter for MEDLINE (Dickersin 1994) and Embase (Lefebvre 1996). Details of the previous search strategies are in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

Latest Searches

For this updated review we included the studies from the previously published review (Schedlbauer 2010; search date 31 March 2008). We updated the search terms to increase the sensitivity of the searches. We applied these changes and reran the searches from database inception. We subsequently applied limits to entry dates or equivalent to all databases except CENTRAL, to identify only those records which had been added to the databases since the last search in 2008.

We ran the most recent database search on 3 February 2016 and included the following databases:

CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2016)

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to January Week 3 2016)

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to Week 5 2016)

PsycINFO (Ovid, 1806 to January Week 4 2016)

CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCO, 1937 to 3 February 2016).

We also searched clinical trials registers (www.anzctr.org.au/ and ClinicalTrials.gov) up to 27 July 2016, using the following search terms: "statin", "adherence", "compliance", "intervention".

We updated the RCT filters for MEDLINE and Embase according to the latest recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook (Lefebvre 2011), and applied adaptations of it to the other databases, except for CENTRAL. Details of the latest search strategies are in Appendix 3. We applied no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We sought additional studies through scrutinising the reference lists of identified eligible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (JS, MM, and RU) selected studies independently by assessing titles and abstracts. We obtained full‐text articles of potentially relevant studies. Following this initial screening, the three review authors (JS, MM, RU) selected trials independently by applying predetermined inclusion criteria. We included a trial if it met all of our inclusion criteria. The review authors discussed disagreements and resolved them, with recourse to MVD and RD when necessary. We used a spreadsheet to identify and extract studies in duplicate.

Data extraction and management

We extracted study outcome data using a predefined data collection tool that had been developed by one of the review authors (MVD). The form had been developed and piloted on a random sample of three studies and refined appropriately. For this updated version of the review, we conducted the 'Risk of bias' assessment for all included studies with Review Manager 5. Three review authors (JS, MM, and RU) extracted data from the newly‐selected studies, with a second author checking the extracted data for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We performed 'Risk of bias' assessment using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed the following 'Risk of bias' categories:

selection bias (by assessing the method of random number generation and the process of allocation concealment);

performance and detection bias (blinding of participants, providers and outcomes assessors);

attrition bias (by assessing how incomplete data were managed); and

reporting bias (by assessing whether all intended outcomes were reported).

See Risk of bias in included studies. We rated each of the studies as 'high risk', 'low risk' or 'unclear risk' for each of these risk of bias domains. We also took into consideration the method used to measure adherence, as some methods are more likely to be biased than others (see Characteristics of included studies). For instance, medication refill data are likely to measure adherence more objectively than manual pill counts, even if outcome assessors are not blinded to group allocation. We applied a judgement of ‘unclear risk’ to blinding where participant and physician were not blinded. We applied a judgement of ‘unclear risk’ to blinding where outcome assessors were not blinded. We also applied a judgement of ‘unclear risk’ to any risk assessment when information was not provided or if there was insufficient information to permit a judgement.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we reported the results as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous data, we reported the mean difference (MD) with standard deviation (SD) of pre‐ and post‐measurements. For serum cholesterol, we report values in mg/dL. We converted cholesterol values reported as mmol/L to mg/dL, using the formula: 1 mmol/l = 38.66976 mg/dL.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis in our meta‐analysis was the participant; however, if this was not the case, such as in cluster‐randomised trials, we planned to make adjustment for clustering in the pooled analysis following the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

If data for analysis were missing, we attempted to obtain information from authors. If no additional data were provided by the authors we used available‐case analysis, which includes analysis of the available data only (thus ignoring the missing data), assuming that the data were missing at random.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the data analysis tools in Review Manager 5 for the assessment of heterogeneity, which is indicated in the forest plots measuring the treatment effect. We assessed heterogeneity by first assessing the comparability of the included studies in terms of population, setting and outcomes (face value or "clinical" heterogeneity). We considered pooling only studies that were sufficiently similar from a clinical perspective. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by calculating the Chi2 statistic (with P value < 0.10 as level of significance) and the I2 statistic.

We used I2 thresholds as described in the Cochrane Handbook as a rough guide to interpretation as follows (Higgins 2011), and used 40% as a cut‐off value for important heterogeneity, which means that we considered an I2 under 40% heterogeneity as low:

• 0% to 40%: might not be important; • 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; • 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; • 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we suspected reporting bias, we contacted the authors to request missing data. As the number of studies available for meta‐analysis was fewer than 10 we did not investigate publication bias by means of a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We grouped the studies according to the type of intervention. In the absence of an existing standard classification for such interventions, the review authors agreed upon a classification based on the pragmatic focus of the intervention. For instance, we considered interventions related to the medication regimen separate from the behavioural approaches involving doctors or other healthcare professionals. We identified seven types of interventions and reported them separately:

Simplification of drug regimen;

Patient education and information;

Intensified patient care;

Complex behavioural approaches;

Decision support systems;

Administrative improvements; and

Pharmacy‐led interventions.

'Usual care' was not defined as a separate intervention. We compared outcomes for each comparison independently, and performed pooling of data and meta‐analysis where possible. We chose a per‐protocol analysis, as intention‐to‐treat analysis would yield misleading results by not showing an effect in many of these studies due to the pragmatic nature of the study designs. We pooled data by using the random‐effects model. We also performed a fixed‐effect model analysis if we assessed statistical heterogeneity as low (I2 < 40%). We used dichotomous outcomes for analysis of medication adherence, and continuous outcomes for analysis of clinical markers.

We included the cross‐over trial (Brown 1997) from the previous version of this review. However, we classified this study as a simplification of drug regimen intervention and could not perform pooling of data and meta‐analysis. Thus, we did not include it in our meta‐analysis for intensified patient care versus usual care.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan any subgroup analyses for this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis for the pooled results by removing the studies that contributed to heterogeneity and comparing the overall outcome estimate. We also compared the results of pooling with a random‐effects model to those using a fixed‐effect model when statistical heterogeneity was low (I2 < 40%, see Assessment of heterogeneity), in order to assess the robustness of the effect estimate. We performed sensitivity analysis for the impact of high attrition on the overall study outcome by removing the studies with high attrition (> 20%).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a Summary of findings table using the following outcomes ‐ medication adherence, reduction in LDL‐C and reduction in total serum cholesterol. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) using GRADEpro software (https://gradepro.org/). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies using footnotes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

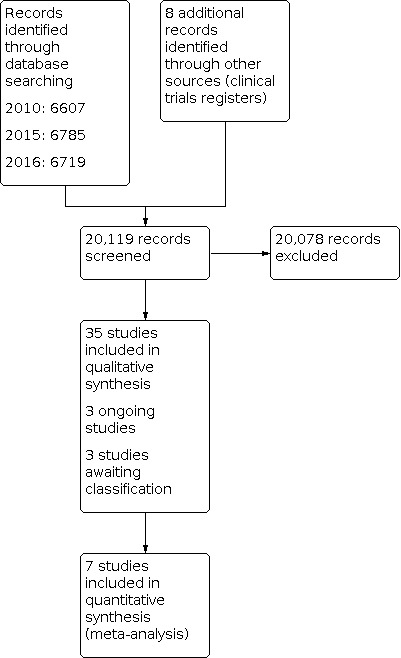

The search for the original 2004 review of this topic retrieved 2380 articles from all sources (Schedlbauer 2004). Eight studies met all inclusion criteria and were analysed. The search for the first update in 2010 (Schedlbauer 2010) identified three additional studies from the 4227 screened records.

The updated search in January 2015 retrieved 6785 articles from all sources. After de‐duplication, we reviewed 5768 titles. Of these references, we excluded 5734 studies by identifying titles and abstracts which did not meet the study criteria for inclusion. We added 16 new studies to the 2010 review. The updated search in February 2016 retrieved 6719 articles from all sources. We reviewed these articles and excluded those which, on the basis of title and abstracts, did not meet the study criteria for inclusion. We added five new studies. One study that was previously excluded was reconsidered and included (Choudhry 2011). We reviewed three other studies also identified in previous searches and originally excluded, and these are awaiting classification (Johnson 2006; Harrison 2015; Lee 2006).

The search in the clinical trials registers retrieved eight references. We identified and included two additional studies (Gujral 2014; PILL 2011) and included two others as ongoing studies (ACTRN12616000422426; ACTRN12616000233426). We identified the protocol of another ongoing study in the 2016 search (Thom 2014).

We summarise the search results in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

This review includes 35 references to 35 studies. The study sizes varied from 30 (Faulkner 2000) to 861,894 (Fischer 2014) with a total of 919,316 participants included in the review. Most trials included both men and women. Two trials included only men (Brown 1997; Schectman 1994). Mean age ranged from 49 to 76.5 years and was not reported in three studies (Fang 2015; Poston 1998; Powell 1995). There was great variation in the types of participants, setting, medication, interventions used and outcomes measured. This is described in more detail in the Characteristics of included studies table. Among the included studies, one study (Brown 1997) was identified as a cross‐over trial and five studies (Aslani 2010; Choudhry 2011; Poston 1998; Tamblyn 2009; Vrijens 2006) as cluster‐RCTs.

See Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions

We stratified interventions into groups on pragmatic grounds, as generally accepted categories do not exist. We identified seven main groups:

Drug regimen simplification (Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013);

Patient education and information (Gujral 2014; Park 2013; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Willich 2009);

Intensified patient care with reminders via mail, telephone and hand‐held pill devices (Aslani 2010; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001; Ho 2014; Kardas 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Schectman 1994; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014);

Complex behavioural approaches, group sessions (Márquez 1998; Pladevall 2014);

Decision support systems (Kooy 2013);

Administrative improvements (Choudhry 2011; Tamblyn 2009);

Large‐scale pharmacy‐led automated telephone intervention (Fischer 2014); Vollmer 2014).

Drug regimen simplification was described as using a formulation (e.g. slow release) that could be given twice rather than four times a day (Brown 1997; Sweeney 1991), or a fixed dose formulation such as a 'polypill' or other (Castellano 2014; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Thom 2013).

Patient education and information was in the form of educative text messages delivered to participants (Park 2013), a 'Program Kit', including a videotape, information booklet, and newsletter (Poston 1998), videotapes mailed to participants (Powell 1995), or a pack containing a videotape, an educational leaflet, details of the free phone patient helpline and website, and labels with a reminder to take study medication, in addition to regular personalised letters and phone calls (Willich 2009). In Gujral 2014 the community pharmacist reviewed the participant monthly when they collected their prescriptions, and at three and six months the pharmacist had a longer discussion with the participant, tailored to their assessed medication beliefs.

Intensified patient care was delivered by different healthcare providers. Interventions involving pharmacists included counselling visits at the pharmacy (Eussen 2010), phone calls by a pharmacist (Faulkner 2000), pharmacist‐led voice messaging (educational and medication refill reminder calls) (Ho 2014), a computer‐based tracking system and a series of co‐ordinated patient‐centred pharmacist‐delivered telephone counselling contacts (Ma 2010), and review by the participants’ pharmacist and a ‘beep‐card’ to remind the participant of the dosing time (Vrijens 2006). Nurses were involved in two studies: counselling from a nurse and an adherence tip sheet (Goswami 2013), and multifactorial risk‐factor counselling by a nurse practitioner (Nieuwkerk 2012). Doctor‐led counselling was delivered in two studies as counselling and advice about the disease, medicine, medicine use, adherence and lifestyle measures (Aslani 2010), counselling every eight weeks (Kardas 2013). Other interventions included automated telephone calls followed by letters (Derose 2012), telephone reminders and reminder postcards (Guthrie 2001), telephone call reminders (Márquez 2004), a calendar reminder (Márquez 2007), telephone calls (Schectman 1994), and text messages using an automated computer programme (Wald 2014) or sent live (Fang 2015).

Complex behavioural approaches were used by Márquez 1998 and consisted of a group session of 90 minutes for a maximum of 15 participants at a time, educating them about hypercholesterolaemia, followed by monthly letters written by the same clinician who delivered the group sessions with reinforcing messages. Pladevall 2014 used medication adherence information given by physicians and motivational interviewing by trained staff (nurses, pharmacists).

Decision support systems consisted of an electronic reminder device (ERD) that started beeping every day at the same time until the participant switched it off (Kooy 2013).

Administrative improvements: in Tamblyn 2009 the physician was provided with the participant's drug profile which included the total costs of medications dispensed each month, the amount of out‐of‐pocket expenditure paid by the participant, a graphic representation of unfilled prescriptions, and days of drug supply for each medication. Then at each visit the participant's adherence was calculated and if treatment adherence was less than 80%, the physician received an alert to check with the participant. In Choudhry 2011 medication co‐payments for participants in the intervention group were waived at the point of care (i.e. pharmacy), whereas participants in the control group continued to pay their usual copayments when refilling their prescriptions.

Large‐scale pharmacy‐led automated telephone intervention was delivered entirely by the pharmacy in Fischer 2014. In the first intervention, the 'automated intervention' participants received automated phone calls on days three and seven to remind them that their prescription was ready for them to pick up if the prescription had been processed by the pharmacy but the participant had not collected it. In the subsequent 'live intervention' a pharmacist or technician called participants who had not collected their prescription despite the reminders. The calls aimed to better understand why participants were not taking their medication and to counsel them regarding appropriate medication use. Vollmer 2014 used automated Interactive Voice Recognition (IVR) Calls to participants when they were due or overdue for a refill. Speech‐recognition technology was used in these calls to educate participants about their medications.

Medication

The lipid‐lowering medications used to treat hyperlipidaemia in most trials were statins (3‐hydroxy‐3‐methyl‐glutaryl‐coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase inhibitors) (Castellano 2014; Choudhry 2011; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Fischer 2014; Goswami 2013; Gujral 2014Guthrie 2001; Ho 2014; Kardas 2013; Kooy 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Park 2013; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Pladevall 2014; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Selak 2014; Tamblyn 2009; Thom 2013; Vollmer 2014; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014; Willich 2009). Anion‐exchange resins or bile acid sequestrants were used in five trials (Faulkner 2000; Pladevall 2014; Schectman 1994; Sweeney 1991; Wald 2014). Niacin or nicotinic acid were used in three trials (Brown 1997; Pladevall 2014; Schectman 1994). Two trials used a combined medication regimen (Faulkner 2000; Schectman 1994), and two trials did not specify a lipid‐lowering medication (Aslani 2010; Tamblyn 2009). Drug therapy was most commonly started after study allocation; only eight studies included participants who were already taking lipid‐lowering medication (Castellano 2014; Fischer 2014; Pladevall 2014; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Selak 2014; Vollmer 2014; Wald 2014).

Cardiovascular risk

Most studies included in this review enrolled participants at high risk of suffering a cardiovascular event, where lipid‐lowering medication was used for primary prevention, whether or not serum cholesterol levels were high (Aslani 2010; Brown 1997; Choudhry 2011; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001; Kardas 2013; Kooy 2013; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Tamblyn 2009; Wald 2014). Nine trials included participants with pre‐existing cardiovascular pathology, thus taking medication for secondary prevention (Castellano 2014; Choudhry 2011; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Gujral 2014; Ho 2014; Ma 2010; Park 2013; Vollmer 2014). The remaining studies looked at people on medication for both primary and secondary prevention (Nieuwkerk 2012; Patel 2015; Pladevall 2014; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994; Thom 2013; Vrijens 2006; Willich 2009). One study (Fischer 2014) identified people at a community pharmacy and did not indicate whether the medication was for primary or secondary prevention.

Settings

Twelve of the included trials took place in primary care (Castellano 2014; Guthrie 2001; Kardas 2013; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Tamblyn 2009; Wald 2014; Willich 2009). In six studies participants were followed up in secondary care (Brown 1997; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Goswami 2013; Nieuwkerk 2012; Park 2013), and three studies took place in both settings (Ma 2010; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013). Other settings were community pharmacies (Aslani 2010; Eussen 2010; Fischer 2014; Gujral 2014; Kooy 2013; Poston 1998; Vrijens 2006), healthcare system (Derose 2012; Pladevall 2014), health maintenance organisation (Choudhry 2011; Powell 1995; Vollmer 2014), and Veterans Affairs medical centres (Ho 2014; Schectman 1994). Trials were set geographically in the USA (15 trials), Netherlands (four trials), Australia (three trials), Spain (three trials), Canada (two trials), England (two trials), Poland (one trial), New Zealand (one trial), India (one trial), China (one trial), Ireland (one trial), and Belgium (one trial). The FOCUS, ORBITAL and PILL trials were conducted across several countries. FOCUS: Argentina, Paraguay, Italy, Spain (Castellano 2014); ORBITAL: Germany, Denmark, Switzerland, and Greece (Willich 2009); PILL: Australia, Brazil, India, Netherlands, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States (PILL 2011).

Follow‐up

Follow‐up times ranged from no follow‐up to 24 months of follow‐up. Most studies achieved their end point outcomes at nine months beginning at three‐month intervals. The frequency of the intervention varied, ranging from one single contact up to 12 (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Outcome measures

The methods used to measure adherence included self‐report, Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS), time to discontinuation, medication possession ratio (MPR), proportion of days covered (PDC), continuous multiple interval (CMI), Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS), drug profile review, prescription refill rate, prescription abandonment, and pill count. Self‐report was assessed by asking participants if they had taken their medication as prescribed and how many doses they missed over a given time period (Choudhry 2011; Guthrie 2001, Nieuwkerk 2012; Patel 2015; Poston 1998; Selak 2014; Wald 2014). The MARS questionnaire was used in two studies (Aslani 2010; Gujral 2014). Time to discontinuation of lipid‐lowering medication was used by three studies (Eussen 2010; Kooy 2013; Schectman 1994). MPR is defined as the number of days on medication after study enrolment divided by the number of days between the first fill and the last refill plus the day's supply of last refill. MPR was used in six studies (Eussen 2010; Goswami 2013; Gujral 2014; Kardas 2013; Poston 1998; Powell 1995). PDC was used in three studies (Goswami 2013; Ho 2014; Vollmer 2014). CMI, the ratio of days supply obtained to total days between refill records, was based on pharmacy records from one study (Ma 2010). MEMS is an electronic system of standard pill bottles with microprocessors in the cap that record the timing and frequency of bottle openings, providing detailed and reliable outcome measures at low risk of bias. MEMS was used in three trials (Márquez 2007; Park 2013; Vrijens 2006). Drug profile review by a physician on each visit with study participants was used in one study (Tamblyn 2009). Prescription refill rates were used by seven studies, where refill information was obtained from pharmacies (Derose 2012; Faulkner 2000; Kooy 2013; Pladevall 2014; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994). Prescription abandonment was used in one study (Fischer 2014). Manual pill counting was performed in seven trials (Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Faulkner 2000; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; PILL 2011; Sweeney 1991). Counting pills is a measure vulnerable to participant manipulation, and one author attempted to increase the reliability of this method by performing unexpected visits to participants' homes for pill counts (Márquez 1998). In another study, pills were not counted in the participant's view in order to avoid influencing their subsequent adherent behaviour (Faulkner 2000). The different methods of measuring adherence was one of the main obstacles in comparing results from the studies, which was further complicated by the fact that some authors used more than one method to measure adherence during their trials.

The report of percentage of mean compliance was considered as the most valid description of compliant behaviour and is reported in the tables of included studies as a main outcome measure, providing the opportunity of comparison between the studies. Other outcome measures reported were: thresholds to define compliant behaviour, i.e. the proportion of participants taking more than 80% of the prescribed medication; discontinuation rates; absolute risk reduction; relative risk reduction; and number needed to intervene in order to save one non‐adherent behaviour (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Serum lipids consisting of total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides are physiological indicators of participant compliance that were the most frequently reported outcome in the following trials: Aslani 2010; Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Eussen 2010; Faulkner 2000; Ho 2014; Ma 2010; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Pladevall 2014; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013; Vollmer 2014; Wald 2014; Willich 2009. Some trials began with a 'start‐up' phase where participants were either taking medication (Brown 1997) or following a diet (Sweeney 1991) before baseline blood samples were taken; the majority of the trials took baseline blood samples immediately after recruitment. Other reported outcome measures included side effects experienced (Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Márquez 1998; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Schectman 1994; Thom 2013; Willich 2009), participant satisfaction (Park 2013), and self‐reported lifestyle measures (Aslani 2010; Guthrie 2001; Nieuwkerk 2012; Sweeney 1991). None of the studies provided data on morbidity or mortality as additional outcome measures.

Commercial sponsorship

Authors declared some form of funding by drug companies in Brown 1997; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Goswami 2013; Gujral 2014; Guthrie 2001; Nieuwkerk 2012; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994; Sweeney 1991; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014; Willich 2009.

Excluded studies

We excluded 62 studies after review (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The most common reason for exclusion was that the study was not aimed at improving adherence. One article was a study description without any outcomes and appeared to be the same as Thom 2013, which we included for analysis; however, the two studies had different trial registration numbers.

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the 'Risk of bias' analysis are shown in Figure 2; Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We rated 11 studies at 'unclear risk' for random sequence generation, as they did not provide sufficient information to make a judgement (Aslani 2010; Brown 1997; Gujral 2014; Guthrie 2001; Kardas 2013; Márquez 1998; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994; Sweeney 1991; Vrijens 2006). We assessed 24 studies at 'low risk' for random sequence generation, as they reported using a computer‐generated allocation process, telephone allocation, or allocation by a statistician who was not involved in conducting the study (Castellano 2014; Choudhry 2011; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Fischer 2014; Goswami 2013; Ho 2014; Kooy 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Park 2013; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Pladevall 2014; Selak 2014; Tamblyn 2009; Thom 2013; Vollmer 2014; Wald 2014; Willich 2009). We rated none of the studies at 'high risk' for random sequence generation.

We assessed 14 studies at 'unclear risk' for allocation concealment, as they did not report sufficient information to allow judgement. (Aslani 2010; Brown 1997; Choudhry 2011; Faulkner 2000; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001; Kardas 2013; PILL 2011; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994; Sweeney 1991; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014) We rated 20 studies at 'low risk' for allocation concealment as this was adequately described and deemed appropriate (Castellano 2014; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Fischer 2014; Ho 2014; Kooy 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 1998; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Park 2013; Patel 2015; Pladevall 2014; Selak 2014; Tamblyn 2009; Thom 2013; Vollmer 2014; Willich 2009). In Gujral 2014 allocation was not concealed as reported in the protocol of the study (ACTRN12611000322932), so we judged this to be at 'high risk' for allocation concealment.

Blinding

One study (Tamblyn 2009) had a single‐blinded study design and was rated as 'high risk'. Physicians and participants were blind to the outcome assessed, but not to the intervention in this study. We assessed 28 studies as being at 'unclear risk', as they had an unblinded, open‐label study design or did not report open‐label design (Aslani 2010; Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Choudhry 2011; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Fischer 2014; Goswami 2013; Gujral 2014; Guthrie 2001; Ho 2014; Kardas 2013; Kooy 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Park 2013; Patel 2015; Pladevall 2014; Poston 1998; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013; Vollmer 2014; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014). Five studies at low risk stated a method where investigators and participants were blind to the outcome and intervention (Derose 2012; Márquez 1998; PILL 2011; Powell 1995; Schectman 1994). Blinding participants to the intervention they were receiving and blinding key study personnel including physicians was often not possible, given the nature of the intervention. Most trials did not report blinding of those assessing the outcome 'adherence'.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged two studies (Gujral 2014; Guthrie 2001) as being at 'high risk' for attrition bias, due to a high rate of attrition in return of a survey tool (Guthrie 2001) or high attrition (31.5%) at the primary end point after 12 months follow‐up (Gujral 2014). We rated six studies as being at 'unclear risk' due to variable rates of study attrition (Brown 1997; Goswami 2013; Márquez 1998; Pladevall 2014; Tamblyn 2009) or not reporting on attrition (Derose 2012). We judged the other studies as being at 'low risk', as they reported minimal to no loss to follow‐up.

Selective reporting

All included studies reported on all intended outcomes, as assessed by comparing the Methods section with the Results section or with the available protocol.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Types of interventions

The trials in this review aimed to increase adherence to lipid‐lowering medication by applying one of the following seven intervention categories. In order to determine study similarities, we created a grid into which we placed studies with similar interventions and comparators. We then further grouped those studies which we found to have both similar interventions and comparators, according to similar outcome measures. In grouping the studies in this manner, we found that there were sufficient studies to conduct a meta‐analysis among those studies comparing such interventions with usual care (see Table 2).

1. Matrix of comparisons in included studies.

| Intervention | ||||||||

| Comparator intervention | 1) simplification of drug regimen | 2) patient education and information | 3) intensified patient care1 | 4) complex behavioural approaches2 | 5) decision support systems3 | 6) administrative improvements4 | 7) pharmacy‐led intervention | |

| 1) simplification of drug regimen | N/A | |||||||

| 2) patient education and information | N/A | |||||||

| 3) intensified patient care1 | N/A | |||||||

| 4) complex behavioural approaches2 | N/A |

Kooy 2013; Pladevall 2014 |

||||||

| 5) decision support systems3 | N/A | |||||||

| 6) administrative improvements4 | N/A | |||||||

| 7) pharmacy‐led intervention | N/A | |||||||

| 8) usual care/placebo |

Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013 |

Gujral 2014; Park 2013; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Willich 2009 |

Aslani 2010; Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Fang 2015; Faulkner 2000; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001Ho 2014; Kardas 2013; Ma 2010; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007; Nieuwkerk 2012; Schectman 1994; Vrijens 2006; Wald 2014 |

Márquez 1998 | Choudhry 2011; Tamblyn 2009 | Fischer 2014; Vollmer 2014 | ||

1 Intensified patient care includes increased follow‐up, sending out reminders, etc. 2 Complex behavioural approaches include increasing motivation by arranging group sessions, giving out rewards, etc. 3 Decision support systems include computer‐based information systems aimed at support of decision‐making. 4 Administrative improvements include audit, documentation, computers.

N/A: not applicable

1. Drug regimen simplification vs usual care

Seven studies attempted to simplify the drug regimen (Brown 1997; Castellano 2014; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Sweeney 1991; Thom 2013). Two studies (Brown 1997; Sweeney 1991) used a regimen with reduction of daily dosing, whereas the other five studies used a fixed‐dose combination or 'polypill' regimen (Castellano 2014; Patel 2015; PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Thom 2013).

We were unable to pool data, as the study publications provided insufficient data, so we describe the results for each of the individual studies below.

Medication adherence ‐ Reducing medication intake from four times to twice daily improved mean medication intake by 11% (96% in the intervention group vs 85% in the control group; P = 0.01; n = 29) (Brown 1997). Drug modification, by administering colestyramine bars instead of powder to make intake easier, did not decrease the adherence rate (91.8% in the intervention group vs 94.8% in the control group; P > 0.05; n = 83) (Sweeney 1991).

In the five studies that used a fixed‐dose combination (FDC) or polypill, four out of five studies showed better adherence with the polypill compared with the separate dosing regimens.

In Castellano 2014, the polypill group showed improved adherence compared with the group receiving separate medications after nine months of follow‐up: 50.8% vs 41%; P = 0.019 (for the intention‐to‐treat population) and 65.7% vs 55.7%; P = 0.012 (for the per‐protocol population); n = 458 (per‐protocol population).

In Patel 2015 participants in the polypill‐based strategy showed greater use of treatment compared to those receiving separate medications after a median of 18 months (70% vs 47%; risk ratio (RR) 1.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.30 to 1.72; P < 0.0001; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 4 (95% CI 3 to 7); n = 623).

In the PILL 2011 study, discontinuation rates were 23% in the polypill group vs 18% in the placebo group (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.00; P = 0.2; n = 373).

In Selak 2014 (n = 513) adherence was greater with the FDC than with usual care at 12 months (81% vs 46%; RR 1.75, 95% CI 1.52 to 2.03; P < 0.001; NNTB 3, 95% CI 2 to 4). Adherence specifically for the statins was not different in the FDC group (94% vs 89%; P = 0.06).

In Thom 2013 using FDC improved adherence vs usual care (86% vs 65%; RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.41; P < 0.001; n = 1921).

Total serum cholesterol ‐Brown 1997 demonstrated low‐/high‐density lipoprotein (LDL/HDL) change from means of 215/46 mg/dl at baseline, to 94/59 mg/dl after run‐in, to 85/52 mg/dl after eight months of controlled‐release niacin, and to 98/56 mg/dl after eight months of regular niacin (regular niacin vs controlled‐release niacin, P < 0.005/ < 0.05). The target of LDL < 100 mg/dl was achieved at eight months by 83% of these participants with controlled‐release niacin and by 52% with regular niacin (P < 0.01).

In Sweeney 1991, total cholesterol decreased by 16% in the bar group and 17% in the powder group (P < 0.01). LDL‐cholesterol decreased by 28% and 29% in the bar and powder groups respectively (P < 0.01). There was no change in HDL cholesterol. Triglycerides increased in both groups, by 29% in the bar group and by 25% in the powder group. There was no difference between bar and powder in the effect on blood lipids.

In the five studies that used a FDC or polypill, two out of five studies found a reduction in LDL‐cholesterol levels with the polypill as compared with the separate dosing regimens (PILL 2011; Thom 2013).

Castellano 2014 did not find a difference in mean low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (89.9 mg/dl vs 91.7 mg/dl) between the groups receiving the polypill or the three drugs administered separately.

In Patel 2015 there was no difference in total cholesterol levels in the polypill‐based strategy compared to those receiving separate medications after a median of 18 months (0.08 mmol/l, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.22; P = 0.26).

The PILL 2011 study found a reduction in LDL‐cholesterol of 0.8 mmol/L, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.9 in favour of the group that was given the polypill.

Selak 2014 did not find any difference in LDL‐cholesterol levels between the FDC group and the control group (difference −0.05 mmol/L (−0.20 vs −0.15, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.08; P = 0.46)).

Thom 2013 found a difference in LDL‐cholesterol in favour of the FDC group (difference −4.2 mg/dL, 95% CI −6.6 to −1.9 mg/dL; P < 0.001) at the end of the study.

Blood pressure ‐ In the studies that used a FDC or polypill, three out of five studies found a reduction in systolic blood pressure (SBP) with the intervention groups as compared with the separate dosing regimens (PILL 2011; Selak 2014; Thom 2013). Brown 1997 and Sweeney 1991 do not report effects on blood pressure.

Castellano 2014 did not find a difference in mean SBP (129.6 mmHg vs 128.6 mm Hg) between the groups receiving the polypill or the three drugs administered separately.

In Patel 2015 there was no difference in SBP in the polypill‐based strategy compared to those receiving separate medications after a median of 18 months (1.5 mmHg, 95% CI 4.0 to 1.0; P = 0.24).

The PILL 2011 study found a reduction in SBP of 9.9 mmHg, 95% CI 7.7 to 12.1 in favour of the group that was given the polypill.

Selak 2014 showed reductions in SBP (−2.6 mmHg, 95% CI −4.0 to −1.1 mmHg; P < 0.001) in the FDC group vs the usual care group.

Thom 2013 showed reduction of SBP (−2.6 mmHg, 95% CI −4.0 to −1.1 mmHg) in the FDC group compared with the usual care group at the end of the study.

Adverse events ‐

Castellano 2014 did not find a difference in number of adverse events between the groups receiving the polypill or the three drugs administered separately (35.4% vs 32.5%, respectively).There were 21 reported serious adverse events (6.0%) in the polypill group vs 23 (6.6% in the control group). There was 1 death in each group (0.3% vs 0.3%).

In Patel 2015 there was at least one serious adverse event reported in 46.3% of participants in the polypill group vs 40.7% in the usual care group (P = 0.16).

The PILL 2011 study 58% in the polypill group reported adverse events compared with 42% in the control group (P = 0.001) The authors report that the side effects were known side effects of the medication contained in the polypill. Four serious adverse events were reported in each group (polypill group: chest pain, newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes, removal of wisdom teeth, syncope; placebo group: syncope, depression, transient ischaemic attack, hip fracture). No deaths, major vascular events, major bleeds or episodes of gastrointestinal ulceration were reported.

In Selak 2014 the number of participants with serious adverse events was not different between groups (fixed dose combination 99 vs usual care 93, P = 0.56). Four deaths occurred in the group with fixed dose combination and 6 in the usual care group (P = 0.75).

Thom 2013 showed no significant differences in serious adverse events (5% in the foxed dose combination group and 3.5% in the usual care group (P = 0.09) between the groups. Seventeen deaths occurred in the fixed dose combination group vs 15 in the usual care group (P = 0.72).

2. Patient education and information vs usual care

Five studies including 8116 participants intended to improve medication adherence by improving patient information and eduction. No consistent improvement was found (Gujral 2014; Park 2013; Poston 1998; Powell 1995; Willich 2009).

Medication adherence ‐ Pharmacist‐mediated information and postal backups, where videotapes, booklets and newspapers were handed out by the local pharmacist followed by educational newsletters sent by post, successfully improved adherence in people who had started taking statins within 60 days before recruitment into the study, but did not improve adherence in those who had been taking statins for more than 60 days before recruitment into the study (Poston 1998). In participants who had started taking statins within 60 days before recruitment into the study, the increase in adherence was 13% (92% in intervention group vs 79% in control group; P ≤ 0.005). In participants who had been taking statins for more than 60 days before recruitment into the study, adherence to long‐term therapy was not improved (92% vs 91%; P value reported as non‐significant but not based on a correct interaction test).

Another study applied a less personal approach, by sending out videotapes to members of a health maintenance organisation who were known to have a pharmacy claim for statins (Powell 1995), not increasing adherence rates (73% in intervention group vs 70% in control group; P > 0.05; n = 568).

Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS) revealed that those who received text messages for antiplatelets had a higher percentage of correct doses taken (t(36) = 2.5; P = 0.02), percentage number of doses taken (t(31) = 2.8; P = 0.01), and percentage of prescribed doses taken on schedule (t(37) = 2.6; P = 0.01; n = 84). Text message response rates were higher for antiplatelets (M = 90.2%; SD = 9) than statins (M = 83.4%; SD = 15.8) (t(26) = 3.1; P = 0.005). Self‐reported adherence revealed no differences among groups (Park 2013).

In another study, participants received a starter pack containing a videotape, an educational leaflet, details of the free‐phone patient helpline and website, and labels with a reminder to take study medication. Participants also received regular personalised letters and phone calls throughout the study. The compliance‐enhancing programme was only effective in statin‐naïve participants at three and six months, but had no overall effect over 12 months (80% vs 76% and 78% vs 73%; P < 0.01; n = 6872) (Willich 2009).

In Gujral 2014 participants in the intervention group received education from the pharmacists tailored to identified misconceptions and beliefs about their medication. However, at the end of the study (after 12 months) there was no difference in adherence: 29% of the participants in the intervention group were non‐adherent compared with 25% in the control group (P = 0.605; n = 137).

Total serum cholesterol ‐Willich 2009 reports that at month 12, 2231 (68.2%) of participants on rosuvastatin plus compliance initiatives and rosuvastatin alone ‐ 2152 (68.4%) were reported as achieving LDL‐cholesterol < 115 mg/dl (P = 0.97), and 1894 (57.6%) of participants on rosuvastatin plus compliance initiatives and 1837 (57.9%) on rosuvastatin alone reported achieving total cholesterol < 190 mg/dl; P = 0.8732; n = 6872.

3. Intensified patient care vs usual care

Sixteen studies randomising 22,785 participants and reporting outcomes on 13,602 participants, investigated the effect of intensified patient care. Reinforcing people to take their medication in the form of written postal material, telephone or other reminders was associated with improved adherence in 10 studies, with results from eight trials reaching statistical significance. There was a positive trend towards improvement in lipid levels in two studies (Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007).

Pooling of data for medication adherence at up to six months included Derose 2012; Eussen 2010; Faulkner 2000; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007. Pooling of data for medication adherence at more than six months included Faulkner 2000; Ho 2014;Vrijens 2006.

Of the 16 RCTs with an intensified patient care intervention, five studies used continuous instead of dichotomous outcomes or cumulative results, and could not be included in the pooled data for medication adherence (Aslani 2010; Fang 2015; Kardas 2013; Ma 2010; Nieuwkerk 2012). For Aslani 2010, low recruitment and high drop‐out rate had a significant impact on the study power (reducing it to 44%) to detect changes in adherence levels but study had sufficient power to detect a statistically and clinically significant difference in total cholesterol levels.

We could not include Schectman 1994 in the pooled data for medication adherence, as this study was very different from the other studies; the medications used, niacin and bile acid salts, had very low adherence due to side effects. In Faulkner 2000, for medication adherence at more than six months, outcome adherence with colestipol was much lower than with lovastatin, due to side effects, so we used lovastatin adherence for pooling of data. Wald 2014 could not be included in the pooled data as outcome measures included combined data from blood pressure and lipid‐lowering medications.

Medication adherence

Sixteen studies report medication adherence for intensified vs usual care interventions (see Table 3); seven provided data for pooling of short‐term adherence and three studies for long‐term adherence. We describe the pooled results below, and report results for the studies that could not be pooled here.

2. Intensified vs usual care: Medication adherence outcomes for pooled studies.

| Study | Intervention | Effective Y/N | Results |

| Faulkner 2000 | Regular phone calls | Y | 24% absolute difference (63% in intervention group vs 39% in control group; P < 0.05 reported; n = 30) |

| Márquez 2004 | Regular phone calls | Y | 29% absolute difference (93% in intervention group vs 64% in control group; P < 0.001 reported; n = 115) |

| Vrijens 2006 | Regular review by the community pharmacist | Y | 6.5% difference (95.9% in the intervention group vs 89.4% in the control group; P < 0.001 reported; n = 392) |

| Derose 2012 | Automated telephone calls followed 1 week later by letters for continued nonadherence | Y | Statins were dispensed to 42.3% of intervention participants and 26.0% of control participants (absolute difference 16.3%; P = 0001; n = 5216) |

| Márquez 2007 | Simple calendar reminder of medication taking given to patient at time of their first prescription | Y | 32% difference (90% in intervention group vs 58% in control group; P < 0.005 reported; n = 186) |

| Guthrie 2001 | Telephone and postal reminders | N | 79.7% in intervention group vs 77.4% in control group; P value non‐significant; n = 4548 |

| Schectman 1994 | Telephone and postal reminders | N | 88% in intervention group vs 82% in control group; P = 0.32; n = 162 |

| Aslani 2010 | Individualised adherence support service delivered at baseline and 3, 6, 9 months to address issues identified from a questionnaire. Interventions included counselling and advice about the disease, medicine, medicine use, adherence and lifestyle measures. | Y | Main effect F2,178 = 4.3; P < 0.05; contrast F1,89 = 5.7; P < 0.05; the intervention group reported that, compared with the control group, they were more liable to alter the dose of their medicine at the third reading compared to the second reading (F1,89 = 4.97; P < 0.05) (n = 142) |

| Eussen 2010 | Community pharmacy–based pharmaceutical care programme | Y | Lower rate of discontinuation within 6 months after initiating therapy versus usual care (HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.96; n = 899); no difference between groups at 12 months (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.10) |

| Goswami 2013 | Integrated intervention programme (nurse counselling, adherence tip sheet, copay relief card, opportunity to enrol in 12‐week cholesterol management programme) | N | HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.96; No significant difference between groups in discontinuation at 12 months (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.10) (n = 208) |

| Kardas 2013 | Educational counselling at each visit (every 8 weeks) and asked to adopt a routine evening activity of choice for a reminder | Y | Mean ± SD MPR was 95.4 ± 53.7% and 81.7 ± 31.0%, for intervention and control group, respectively (P < 0.05; n = 196) |

| Ma 2010 | Pharmacist‐delivered telephone counselling calls post‐hospital discharge | N | The continuous multiple interval (CMA) for statin medication use was 0.88 (SD = 0.3) in the PI condition (referring to the participant being 88% adherent to their statins medication), and 0.90 (SD = 0.3) in the usual care condition (P = 0.51) (n = 559) |

| Nieuwkerk 2012 | Nurse‐led cardiovascular risk‐factor counselling | Y | Statin adherence was significantly higher (P < 0.01) and anxiety was significantly lower (P < 0.01) in the intervention group (n = 181) |

| Ho 2014 | Pharmacist‐led counselling, patient education, teamwork with participant's primary physician, and voice messaging | Y | 89.3% in the intervention group were adherent vs 73.9% in the usual care group (P = 0.003) (n = 241) |

| Fang 2015 | Short message service (SMS) and SMS plus Micro Letter (ML) | Y | SMS and SMS + ML groups had better cumulative adherence after 6 months than the phone group. The SMS + ML group had better cumulative adherence than the SMS group (n = 271) |

| Wald 2014 | Texts sent daily for 2 weeks, alternate days for 2 weeks and weekly thereafter for 22 weeks using an automated computer programme | Y | improvement in adherence affecting 16 per 100 participants (95% CI 7 to 24), P = 0.001 (n = 301) |

In Aslani 2010 (n = 97), Medication Adherence Report Scales showed no changes in medicine adherence scores, although intervention participants were less likely to take less than the prescribed dose after the first‐time interval (main effect F2,178 = 4.3; P < 0.05; contrast F1,89 = 5.7; P < 0.05), and the intervention group reported that compared with the control group they were more liable to alter the dose of their medicine at the third reading compared to the second reading (F1,89 = 4.97; P < 0.05).

In Kardas 2013, the intervention group received educational counselling at each visit (i.e. every eight weeks) and were also asked to adopt a routine evening activity of their choice for a reminder. Study arms differed in their level of adherence: mean ± SD MPR was 95.4% ± 53.7% and 81.7% ± 31.0%, for intervention and control groups respectively (P < 0.05; n = 196).

Participants in the intervention group of Ma 2010 (n = 559) received five pharmacist‐delivered telephone counselling calls post‐hospital discharge. The continuous multiple interval (CMI) for statin medication use was 0.88 (SD 0.3) in the pharmacy‐delivered intervention (PI) (referring to the participant being 88% adherent to their statins medication), and 0.90 (SD 0.3) in the usual care condition (P = 0.51), leading to the conclusion that a pharmacist‐delivered intervention aimed only at improving participant adherence is unlikely to positively affect outcomes.

Nieuwkerk 2012 (n = 181) demonstrated that statin adherence was higher (P < 0.01) and anxiety was lower (P < 0.01) in the intervention group, which received nurse‐led cardiovascular risk‐factor counselling than in the routine‐care group.

In Fang 2015 (n = 271) participants who were randomised to the short message service (SMS) and those in the SMS + Micro Letter group had better cumulative adherence (lower Morisky Medication Adherence Scale scores) after six months than the phone group. The SMS + Micro Letter group had better cumulative adherence (lower Morisky Medication Adherence Scale scores) than the SMS‐alone group.

Pooling of the results

We grouped the results into long‐term adherence and short‐term outcomes. We defined short‐term results as those outcomes measured at up to six months, and long‐term outcomes as measured at more than six months. We then pooled results according to long‐term or short‐term outcomes. When it was not provided, we estimated the SD for the difference between means using the formula σd = sqrt ( σ12 / n1 + σ22 / n2 ). We estimated the SDs for Aslani 2010 and Faulkner 2000.

The forest plots in Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 1.2 both show pooled treatment effects of the intensification of patient care category of interventions when compared with usual care and using adherence measures as an outcome in both short‐term and long‐term measures. Forest plots in Analysis 1.4 show the pooled effect estimate for total cholesterol level over both short‐ and long‐term follow‐up.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intensified patient care vs usual care, Outcome 1: Medication adherence at ≤ 6 months

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intensified patient care vs usual care, Outcome 2: Medication adherence at > 6 months

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intensified patient care vs usual care, Outcome 4: Reduction in total serum cholesterol at > 6 mos (mg/dL)

We did not adjust the Aslani 2010 data for clustering as the expected clustering effect of patients within pharmacies in Australia is very low (Armour 2007).

Medication adherence at ≤ 6 months

Pooling of data for medication adherence at up to six months using per‐protocol analysis of dichotomous outcomes included seven studies involving 11,204 participants. There was considerable heterogeneity (I² = 88%). Meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model estimated an odds ratio of 1.93 (95% CI 1.29 to 2.88; 7 studies; 11,204 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), favouring the intervention (Analysis 1.1). Removing the three studies with less intensive interventions that contributed to the heterogeneity (as is also apparent from the forest plot) from the pooled analysis (Derose 2012; Márquez 2004; Márquez 2007) resulted in an of OR 1.19 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.39; I² = 0%), favouring the intervention. All but one study (Guthrie 2001) had low attrition rates. A sensitivity analysis excluding Guthrie 2001, which had very high attrition (only 35% of surveys were returned to the investigators), resulted in an OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.41 to 3.49 (Analysis 1.7). The conclusions remained unaltered (Table 1).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Intensified patient care vs usual care, Outcome 7: Attrition rate sensitivity analysis (medication adherence at ≤ 6 months)

Medication adherence at > 6 months

Pooling of data for medication adherence at more than six months using per‐protocol analysis of dichotomous outcomes included three studies involving 663 participants. The studies were homogeneous (I² = 0%). Meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model estimated an odds ratio of 2.87 (95% CI 1.91 to 4.29; 3 studies; 663 participants; high‐quality evidence), favouring the intervention (Analysis 1.2). Using a fixed‐effect model did not alter the estimate (OR = 2.87, 95% CI 1.92 to 4.30) nor the conclusions.

Although Vrijens 2006 contributes 59% of the weighting, the estimate remains robust if this study is removed: the result is OR 3.82, 95% CI 2.03 to 7.18; I² = 0%, favouring the intervention, and hence the overall conclusion remained unchanged (Table 1).

Total serum cholesterol and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol ‐ From the 16 RCTs that used intensified patient care, five studies (Derose 2012; Goswami 2013; Guthrie 2001; Schectman 1994; Vrijens 2006) did not use lipid levels as an outcome measure.