Abstract

Background

Ischaemia reperfusion injury can lead to kidney dysfunction or failure. Ischaemic preconditioning is a short period of deprivation of blood supply to particular organs or tissue, followed by a period of reperfusion. It has the potential to protect kidneys from ischaemia reperfusion injury.

Objectives

This review aimed to look at the benefits and harms of local and remote ischaemic preconditioning to reduce ischaemia and reperfusion injury among people with renal ischaemia reperfusion injury.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register to 5 August 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials measuring kidney function and the role of ischaemic preconditioning in patients undergoing a surgical intervention that induces kidney injury. Kidney transplantation studies were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed for eligibility and quality; data were extracted by two independent authors. We collected basic study characteristics: type of surgery, remote ischaemic preconditioning protocol, type of anaesthesia. We collected primary outcome measurements: serum creatinine and adverse effects to remote ischaemic preconditioning and secondary outcome measurements: acute kidney injury, need for dialysis, neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin, hospital stay and mortality. Summary estimates of effect were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes.

Main results

We included 28 studies which randomised a total of 6851 patients. Risk of bias assessment indicated unclear to low risk of bias for most studies. For consistency regarding the direction of effects, continuous outcomes with negative values, and dichotomous outcomes with values less than one favour remote ischaemic preconditioning. Based on high quality evidence, remote ischaemic preconditioning made little or no difference to the reduction of serum creatinine levels at postoperative days one (14 studies, 1022 participants: MD ‐0.02 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.02; I2 = 21%), two (9 studies, 770 participants: MD ‐0.04 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.02; I2 = 31%), and three (6 studies, 417 participants: MD ‐0.05 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 68%) compared to control.

Serious adverse events occurred in four patients receiving remote ischaemic preconditioning by iliac clamping. It is uncertain whether remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff inflation leads to increased adverse effects compared to control because the certainty of the evidence is low (15 studies, 3993 participants: RR 3.47, 95% CI 0.55 to 21.76; I2 = 0%); only two of 15 studies reported any adverse effects (6/1999 in the remote ischaemic preconditioning group and 1/1994 in the control group), the remaining 13 studies stated no adverse effects were observed in either group.

Compared to control, remote ischaemic preconditioning made little or no difference to the need for dialysis (13 studies, 2417 participants: RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.94; I2 = 60%; moderate quality evidence), length of hospital stay (8 studies, 920 participants: MD 0.17 days, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.80; I2 = 49%, high quality evidence), or all‐cause mortality (24 studies, 4931 participants: RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.37; I2 = 0%, high quality evidence).

Remote ischaemic preconditioning may have slightly improved the incidence of acute kidney injury using either the AKIN (8 studies, 2364 participants: RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.00; I2 = 61%, high quality evidence) or RIFLE criteria (3 studies, 1586 participants: RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.12; I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff inflation appears to be a safe method, and probably leads to little or no difference in serum creatinine, adverse effects, need for dialysis, length of hospital stay, death and in the incidence of acute kidney injury. Overall we had moderate‐high certainty evidence however the available data does not confirm the efficacy of remote ischaemic preconditioning in reducing renal ischaemia reperfusion injury in patients undergoing major cardiac and vascular surgery in which renal ischaemia reperfusion injury may occur.

Plain language summary

Short periods of limb blood flow obstruction to reduce kidney injury

What is the issue?

The kidney is highly sensitive to shortage in blood flow and thus oxygen supply. This may cause irreversible kidney injury leading to haemodialysis or death. Kidney injury does not only relate to the temporary lack of oxygen supply, but is also due to the re‐saturation of blood flow. At this stage, toxic products are released and initiate a reaction of the body causing further cellular damage within the kidney, the so called ‘ischaemia‐reperfusion injury’. A lack of oxygen supply to the kidney injury may have many different causes, for example blood pressure changes that may occur during major surgery.

What did we do?

Our hypothesis is that short harmless periods (5 minutes) of blood flow obstruction to an organ can reduce injury in this particular organ (local ischaemic preconditioning), but can also reduce injury in other organs at a distance (remote ischaemic preconditioning). A blood flow obstruction can easily and safely be achieved in a limb by inflating blood pressure cuff around the upper arm or leg. The mechanism of this remote ischaemic preconditioning is not precisely known, it is assumed that a protective signal from the remote organ to the kidney is transferred through the blood stream or nervous system.

In this analysis our primary goal is to investigate whether remote ischaemic preconditioning is safe and effective in reducing kidney injury in patients undergoing a (surgical) procedure in which kidney injury may occur. Kidney injury after kidney transplantation may have a different underlying pathophysiology and therefore these studies are not taken into account. The impact of remote ischaemic preconditioning on the need for dialysis, hospital stay and mortality will be assessed.

What did we find?

We performed a search off all available literature on 8 August 2016 to find all randomised controlled studies. 28 studies including 6851 patients were included in this analysis. Five studies included children undergoing cardiac surgery. Adult studies included patients undergoing major vascular surgery (three studies), cardiac surgery (nine studies), coronary bypass surgery (10 studies) and partial kidney resection (one study). The overall quality of the studies was acceptable.

Twenty studies were funded without economical interest. One study was funded from a source with commercial interest. The other seven studies did not report funding.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning performed with a blood pressure cuff appears to be safe as only two of 15 studies reported adverse effects (6/1999 in the remote ischaemic preconditioning group and 1/1994 in the control group). However remote ischaemic preconditioning by vascular clamping may cause vascular complications. Kidney injury in patients undergoing (surgical) procedures in which kidney injury may occur, was not reduced by remote Ischaemic preconditioning measured at day one, two or three after surgery. The need for dialysis, hospital stay and death were not reduced by remote ischaemic preconditioning.

Conclusion

Although remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff inflation is safe, available data do not confirm the efficacy of remote ischaemic preconditioning in reducing kidney injury.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings table.

| Ischaemic preconditioning for the reduction of renal ischaemia reperfusion injury | ||||||

| Patients or population: patients undergoing a surgical intervention that induces kidney injury Setting: perioperative hospital setting Intervention: ischaemic preconditioning Control: no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of patients (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no treatment | Risk with RIPC | |||||

| Serum creatinine: day 1 | The mean serum creatinine on day 1 was 0 mg/dL | MD was 0.02 mg/dL lower (0.05 mg/dL lower to 0.02 mg/dL higher) | ‐ | 1022 (14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Funnel plot assessment suggests publication bias. Analysis without small studies showed no significant differences. |

| Serum creatinine: day 2 | The mean serum creatinine on day 2 was 0 mg/dL | MD was 0.04 mg/dL lower (0.09 mg/dL lower to 0.02 mg/dL higher) | ‐ | 770 (9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Funnel plot assessment suggests publication bias, however due to a limited amount of studies these results should be interpreted with care. Analysis without small studies showed no significant difference |

| Serum creatinine: day 3 | The mean serum creatinine day 3 was 0 mg/dL | MD was 0.05 mg/dL lower (0.19 mg/dL lower to 0.1 mg/dL higher) | ‐ | 417 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Insufficient data to assess publication bias. |

| Adverse events related to RIPC | Study population | RR 3.47 (0.55 to 21.76) | 3993 (15) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Adverse effects due to remote ischaemic preconditioning only occurred in traumatic clamping of arteries. There were no reports of adverse events when applying remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff | |

| 1 per 1,000 | 2 per 1,000 (0 to 11) | |||||

| Need for dialysis | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.37 to 1.94) | 2417 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate | The low incidence of dialysis results in a moderate Grade of evidence | |

| 38 per 1,000 | 32 per 1,000 (14 to 74) | |||||

| Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.57 to 1.00) | 2364 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | This outcome regards the overall AKIN score, when subdivided in grade 1, 2 and 3 there is no evidence of effect | |

| 369 per 1,000 | 281 per 1,000 (211 to 369) | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.54 to 1.37) | 4931 (24) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ||

| 17 per 1,000 | 15 per 1,000 (9 to 23) | |||||

| The risk in the intervention group (and the 95% confidence interval) is based on the risk in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

RIPC ‐ remote ischaemic preconditioning

Background

Description of the condition

Ischaemia reperfusion injury is defined as damage to an organ that occurs after a critical period of ischaemia, followed by restoration of blood supply. This can happen spontaneously, such as in stroke or myocardial infarction, or during transplantation and other types of surgery. Cells become deprived of oxygen in the ischaemic phase, and as a result, metabolism switches from aerobic to anaerobic glycolysis, leading to cell swelling, acidosis, ATP depletion, intracellular sodium (Na+) and calcium ion (Ca2+) overload and inhibition of the mitochondrial respiration chain. This leads to cell death in minutes to hours, depending on the cell type. Restoration of blood flow after ischaemia is therefore essential for cell survival. However, reperfusion of ischaemic tissue invokes paradoxical effects that are detrimental, rather than beneficial, to cells. This particularly holds true for sudden restoration of oxygen (which leads to oxidative stress), pH (which can induce cell death), and evoked inflammatory response. Inflammatory response induces adhesion of cytokine‐releasing leukocytes, which attracts neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and dendritic cells to the site. This may cause further release of reactive oxygen species and microvascular dysfunction (Bonventre 1988; Piper 1998; Yellon 2007).

Ischaemia reperfusion injury can lead to organ dysfunction or failure and is a significant clinical problem in transplantation, shock and major surgery. The high metabolism and vascular anatomy of the kidney is particularly sensitive to ischaemia reperfusion injury. The critical ischaemic period is organ‐dependent: 15 to 20 minutes of ischaemia has been shown to cause irreversible damage to the kidney (Jaeschke 2002; Safian 2001; Schrier 2004).

Description of the intervention

Ischaemic preconditioning is a short and harmless period of deprivation of blood supply to particular organs or tissue, followed by a period of reperfusion (Chen 2009; Hausenloy 2009; Yin 1998). Preconditioning stimulus is applied before onset of ischaemia reperfusion injury to a target organ. In 1986 it was shown that ischaemic preconditioning on the heart can reduce ischaemia reperfusion injury, (local ischaemic preconditioning) (Murry 1986), and has since been reproduced in many other target organs. Later on, studies have shown that ischaemic preconditioning of remote organs and tissues at a distance can protect the target organ from ischaemia reperfusion injury as well (remote ischaemic preconditioning, Przyklenk 1993). Use of the limbs as remote tissue offers many advantages, since skeletal muscle is less susceptible to ischaemia reperfusion injury compared to visceral tissues.

A typical schedule of five minute periods of ischaemic preconditioning, separated by five minutes of reperfusion, applied directly before the ischaemia reperfusion injury period of the target organ, is used in most clinical studies. Numerous variations to this schedule have been studied in animals and the efficacy of the ischaemic preconditioning has been shown to vary, depending on the animal sex, animal species, preconditioned tissue volume, length of ischaemic preconditioning, reperfusion and time between ischaemic preconditioning and ischaemia reperfusion injury. The optimal schedule is still unclear and is probably different for different target organs and species (Alreja 2012; Cochrane 1999; Wever 2012).

How the intervention might work

Several endogenous molecules have been implicated in local and remote ischaemic preconditioning signalling, most of which are known to have cytoprotective effects. Downstream, the ultimate protective step in ischaemic preconditioning signalling appears to be inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, which prevents cell death. Remote and local ischaemic preconditioning appear to be similar in terms of invoking mitochondrial permeability transition pore inhibition, and many signalling molecules seem to be similar to those implicated in local ischaemic preconditioning signalling. The theoretical difference is that remote ischaemic preconditioning requires transduction of the protective signal from the remote organ or tissue to the target organ.

The protective effects of ischaemic preconditioning are found both directly after application of the stimulus (early window of protection), and in the days or weeks following (second window of protection). In animal models, both windows of protection have been shown to reduce renal ischaemia reperfusion injury (Wever 2012). Although there are similarities in the mechanisms underlying early and second windows of protection, the second window of protection has been found to require de novo protein synthesis of distal mediators such as iNOS and COX‐2. However, remote ischaemic preconditioning signalling has been most extensively studied in the early window of protection, where three major pathways have been indicated in this process (Figure 1): the humoral route, the neurogenic pathway and alteration of immune cells. Signalling via the humoral route (upper route, Figure 1) requires release of signalling molecules such as adenosine or endorphins from the remote organ into the bloodstream, which are then carried to the target organ to exert their protective effects via their respective receptors.

1.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning signalling pathways

The nervous system also appears to play a role in some models of remote ischaemic preconditioning: denervation or ganglion blockade inhibit the protective effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning (middle route, Figure 1). Activation of the neurogenic pathway by peptides released from the remote organ may cause systemic factor release (combined humoral‐neurogenic route), lead to local factor release or activation of central reflexes. Both the humoral and the neurogenic pathways are thought to induce various kinase cascades and eventually prevent opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in the target organ cells, thereby reducing cell death. Thirdly, remote ischaemic preconditioning has been shown to modulate gene and receptor expression on immune cells, which therefore pose a third signalling pathway that presumably reduces damage by altering the inflammatory response (lower route, Figure 1) (Tapuria 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite that the efficacy of ischaemic preconditioning has been acknowledged since described by Murry 1986, the technique was introduced into clinical studies only relatively recently; however, results to date have not been consistently positive (Ali 2007; Choi 2011; Walsh 2008; Walsh 2010; Zimmerman 2011). Although experimental data show promise, the mechanism underlying ischaemic preconditioning signalling remains unclear and the optimal preconditioning protocol remains unknown (Wever 2012).

The kidney is very sensitive to ischaemia reperfusion injury, and therefore, is an organ system that can benefit from ischaemic preconditioning. Furthermore, kidney function and damage are very well documented and can be tested using robust endpoints. The kidney is therefore an ideal target organ to investigate the protective effects of ischaemic preconditioning on renal ischaemia reperfusion injury.

Objectives

This review aimed to look at the benefits and harms of local and remote ischaemic preconditioning to reduce ischaemia and reperfusion injury among people with renal ischaemia reperfusion injury.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) looking at the role of ischaemic preconditioning versus no ischaemic preconditioning among patients undergoing interventions that result in ischaemic kidney damage were eligible for inclusion. There was no restriction on publication status, language, or sample size. Quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) were excluded.

Types of participants

We included all patients who underwent any intervention for any indication that resulted in ischaemic kidney damage (e.g. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, open aneurysm repair, coronary artery bypass grafting, aortic surgery and any other type kidney surgery). Liver, lung and peripheral bypass surgeries in which kidney injury was highly unlikely were excluded. Studies investigating ischaemic preconditioning in kidney transplantation or patients at risk for contrast‐induced nephropathy, including endovascular aneurysm repair, were excluded.

Types of interventions

The ischaemic preconditioning protocol could include remote and/or local ischaemic preconditioning stimulus applied before the intervention and the remote stimulus could be applied to any organ. Preconditioning stimuli could be continuous (one continuous ischaemic pulse followed by reperfusion) or fractioned (two or more cycles of brief ischaemia and reperfusion). The ischaemic preconditioning stimulus could be applied directly before index ischaemia or some time, even days, before. The control condition of no ischaemic preconditioning could be no intervention or mock ischaemic preconditioning, that is, application of a tourniquet, blood pressure cuff or other means of occlusion without actually interrupting blood flow.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Serum creatinine on days one, two or three postoperative

Complications and adverse effects related to ischaemic preconditioning

Secondary outcomes

Need for dialysis following kidney‐related ischaemia

Acute kidney injury (AKI) as defined by KDIGO, AKIN and RIFLE criteria (KDIGO 2012; Mehta 2007; Ricci 2008)

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

Serum/urine neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL)

Serum/urine kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1)

Mortality

Quality of life

Length of hospital stay

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 8 August 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however studies and reviews thought to include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and if required assessed the full text of these studies to determine which satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were to be translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was to be highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. need for dialysis and death) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement had been used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. serum creatinine), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales were used.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. e‐mailing or writing to corresponding authors) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If possible, funnel plots were to be used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also to be used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. preconditioning site, number of ischaemic preconditioning stimuli, early versus late windows of protection). Heterogeneity among participants related to age and gender. Heterogeneity in treatments related to the type of intervention such as major aorta surgery or coronary artery bypass surgery. Adverse effects were to be tabulated and assessed using descriptive techniques. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was to be calculated for each adverse effect, either compared with no treatment or another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

Summary of findings tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Serum creatinine on days one, two and three

Adverse events of remote ischaemic preconditioning

Need for dialysis

AKI defined by the AKIN score

Mortality

Results

Description of studies

A detailed description of all studies can be found in Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search identified 1381 unique records (Appendix 1). Two independent review authors screened each reference for inclusion on the basis of title and abstract, and subsequently assessed full‐text copies of all publications eligible for inclusion. For five studies presented only as abstract, full text publications were obtained by contacting authors by e‐mail. We identified 55 studies (70 records). Of these, 28 studies (38 records) were included and 27 excluded (32 records) (Figure 2).

2.

The flow diagram of references

Included studies

We included 28 studies (Ali 2007; Candilio 2015; Choi 2011; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; ERICCA Study 2012; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Huang 2013; Kim 2012a; Lee 2012; Li 2013; Lomivorotov 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pepe 2013; Pinaud 2016; Rahman 2010; RIPHeart Study 2012; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2010; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Walsh 2010; Young 2012; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011) reporting data from a total of 6851 patients undergoing a surgical procedure associated with renal ischaemia and reperfusion (I/R). Czibik‐stable 2008 and Czibik‐unstable 2008 are the same study, however we have analysed this as two separate studies because the outcomes for two different patient populations (stable and unstable angina) were reported separately.

Patients were randomised to undergo remote ischaemic preconditioning (remote ischaemic preconditioning; n = 3441) or a control intervention consisting of sham remote ischaemic preconditioning or no treatment (n = 3441). All 28 studies reported at least one kidney outcome measure. See Characteristics of included studies for details on sample size, procedure, patient characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention and reported outcomes.

Participants

Five studies included only children, all aged < 17 years old, scheduled for heart surgery (Lee 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pepe 2013). Other studies included adult cardiovascular patients scheduled for a coronary artery bypass graft (11 studies), cardiac surgery (nine studies) or aortic aneurysm repair (three studies). One study included kidney cancer patients undergoing partial nephrectomy (Huang 2013).

Methods of remote ischaemic preconditioning induction: site, timing and protocols

The intervention of interest in all studies was remote ischaemic preconditioning, which was compared to a control intervention. All studies applied preconditioning only, except for Hong 2012, Hong 2014 and Kim 2012a, in which the conditioning protocol was applied both before and after surgery, thereby inducing a combination of remote ischaemic preconditioning and remote ischaemic postconditioning.

Cuff inflation was the preferred method of remote ischaemic preconditioning induction: 25 studies used a blood pressure cuff to induce ischaemia in an upper arm (15 studies), lower limb (nine studies) or both (Candilio 2015). Walsh 2010 applied their remote ischaemic preconditioning protocol to each lower limb, one after the other. Ali 2007 and Walsh 2010 induced remote ischaemic preconditioning by clamping of the common iliac artery. In one study, (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008) the (suprarenal) ascending aorta was clamped, thereby inducing both remote ischaemic preconditioning and local ischaemic preconditioning.

The remote ischaemic preconditioning stimulus was applied directly after anaesthetic induction in all studies, except for Pavione 2012, in which remote ischaemic preconditioning was induced 24 hours before surgery, making this the only study investigating the so‐called second window of protection by ischaemic preconditioning.

Seven different remote ischaemic preconditioning protocols were used among the 28 studies. The most frequently used protocol consisted of three cycles of five minutes of occlusion of the remote organ, interspersed with five minutes of reperfusion (3 x 5'/5' I/R), (Huang 2013; Li 2013; Lomivorotov 2012; Pinaud 2016; Rahman 2010; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2010; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011). Other protocols were 4 x 5'/5' I/R (ERICCA Study 2012; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Lee 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pepe 2013; RIPHeart Study 2012; Young 2012), 3 x 10'/10' I/R (Choi 2011; Kim 2012a), 2 x 10'/10' I/R (Ali 2007), 2x 5 min (Candilio 2015), 2 x 2'/3' I/R (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008) and cross‐clamping the right common iliac artery 10 min, thereafter clamping the left common iliac artery (Walsh 2010).

Outcome measures

The included studies reported a variety of outcome measures. Kidney impairment (e.g. postoperative creatinine, NGAL, AKIN score and RIFLE score) was the primary outcome in seven studies (25%) (Choi 2011; Huang 2013; Pedersen 2012; Walsh 2010; Young 2012; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011). RIPHeart Study 2012 reported a composite primary end point of death, myocardial infarction, stroke and AKI. Cardiac outcome measures were the primary endpoint in 10 studies (Ali 2007; Candilio 2015; ERICCA Study 2012; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Lee 2012; Pinaud 2016; Rahman 2010; Thielmann 2010; Thielmann 2013), and pulmonary outcome measures were the primary endpoint in three studies (Kim 2012a; Li 2013; Luchinetti 2012). McCrindle 2014 reported hospital stay, Pavione 2012 reported IL4, and Slagsvold 2014 reported myocardial microRNA expression as primary outcome measures. In the remaining four studies there were no specified primary or secondary outcome measures (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; Venugopal 2009; Lomivorotov 2012; Pepe 2013). Mortality was reported in 24 studies, duration of hospital stay in 8 studies, and incidence of adverse effects of remote ischaemic preconditioning in 13 studies. Other reported outcome measures were myocardial injury, pulmonary injury, stroke, ICU stay, inotropic support, and a wide variety of non‐kidney molecular markers (e.g. IL‐8, CK‐MB and NF‐kB).

Kidney outcome measures differed substantially among studies. Serum creatinine was published in 15 studies at 13 different time points postoperatively. Serum NGAL was reported in two studies (Choi 2011; Pedersen 2012) at day one, two and three after surgery. Incidence of AKI was reported in 10 studies, of which Pedersen 2012, RIPHeart Study 2012 and Young 2012 assessed AKI incidence according to the RIFLE criteria, and Candilio 2015, Choi 2011, ERICCA Study 2012, Pinaud 2016, Venugopal 2009, Zarbock 2015, and Zimmerman 2011 used the AKIN criteria.

Excluded studies

Studies on surgical procedures unlikely to cause kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury (Fudickar 2014; Hougaard 2014; Li 2014f; McDonald 2014; Memtsoudis 2014; Park 2014a; Rodriguez 2015; Stazi 2014), studies without remote ischaemic preconditioning applied (Julier 2003; Rabl 1993; Vesnina 2011; Wang 2014d; Ziegeler 2004), studies relating to transplantation (Chen 2013), and studies investigating iodine contrast (Crimi 2013; CRISP Stent Study 2009; Lavi 2014; Manchurov 2014; RenPro Trial 2012; Sloth 2014; Walsh 2009a; Xu 2014; Zografos 2014) were excluded. Studies in patients undergoing kidney transplantation or intravenous contrast administration were excluded because of the differences in pathophysiology of the inflicted kidney injury.

Studies with a different primary outcome measure than kidney injury and with an intervention causing kidney injury were included if they published kidney outcome measures. However, not all studies reported kidney outcome measures, we emailed the authors of those studies for kidney data and if no reply was received, we attempted to contact them again after three weeks. Studies without published kidney outcome measures were excluded after this second email attempt (Bautin 2014; Hausenloy 2007; Holmberg 2014; Li 1999a).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessment was performed by two independent review authors and summarised in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Most included studies reported adequate methods of random sequence generation for patient allocation, which was assessed at low risk of selection bias. A computer generated random number sequence was used in 22 studies; Zimmerman 2011 used manually shuffled blocks which we also reported as low risk of bias. In one study (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008) randomisation was not reported, leading to a high risk of selection bias. Lee 2012, Lomivorotov 2012, Pepe 2013 and Thielmann 2010 reported randomisation, but did not report the method used, and were therefore assessed to be at unclear risk of selection bias.

There were 16 studies reporting blinding of allocation using numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes, which was assessed to introduce a low risk of selection bias. The remaining 12 studies did not mention whether the patient allocation was blinded. For these studies (Choi 2011; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; ERICCA Study 2012; Huang 2013; Lee 2012; Lomivorotov 2012; Pavione 2012; Pepe 2013; Pinaud 2016; Thielmann 2010; Venugopal 2009), the risk of selection bias was assessed as unclear.

Blinding

Many studies did not adequately report measures to reduce performance and detection bias. Only 16 studies reported adequate blinding of investigators and involved personnel, such as by hiding the blood pressure cuff and using an independent investigator to perform the remote ischaemic preconditioning protocol. The risk of performance bias in these studies was therefore assessed to be low. Pinaud 2016 reported their study as single blinded and therefore was assessed as high risk of bias. The remaining 11 studies had unclear risk of bias as blinding was not described. Patients were anaesthetised during remote ischaemic preconditioning in all studies except for Pavione 2012; however, anaesthesia does not ensure that patients are fully blinded for the allocated intervention. All studies therefore were assessed at unclear risk of bias.

Ten studies (Candilio 2015; ERICCA Study 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pinaud 2016; Pavione 2012; Rahman 2010; RIPHeart Study 2012; Slagsvold 2014; Young 2012) reported adequate blinding of outcome assessors and were therefore rated as being at low risk of detection bias. Fifteen studies did not adequately report blinding of outcome assessors and were assessed at unclear risk of detection bias. Three studies did not mention blinding of outcome assessors and were assessed at high risk of bias (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; Li 2013; Zimmerman 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

Risk of attrition bias was unclear in 15 studies (Ali 2007; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Lee 2012; Lomivorotov 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pepe 2013; Pinaud 2016; RIPHeart Study 2012; Thielmann 2010; Walsh 2010; Young 2012) and high in two studies (Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013). Eleven studies (Candilio 2015; Choi 2011; ERICCA Study 2012; Huang 2013; Kim 2012a; Li 2013; Pedersen 2012; Rahman 2010; Venugopal 2009; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011) reported missing data and prespecified outcome measures, indicating a low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

The risk of reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting was assessed to be low in most studies. This was based on the fact that, in most studies, the outcome measures specified in the introduction matched those presented in the results of the article (19 studies). In six studies (Pinaud 2016; RIPHeart Study 2012; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Zarbock 2015) the risk of reporting bias was assessed to be high, due to the incoherency between reported outcome measures in the method section of the articles and the results.

Performing funnel plots for the primary outcome measures, there is a high suspicion of underreporting negative small studies as can be seen in the funnel plots of serum creatinine on days one and two (Figure 5; Figure 6).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Serum creatinine, outcome: 1.6 Creatinine day 1 [mg/dL].

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Serum creatinine, outcome: 1.8 Creatinine day 2 [mg/dL].

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies were classified as high risk of bias for the following reasons.

Pavione 2012 failed to adequately report the patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Thielmann 2013 and Venugopal 2009 studies reported changes in the anaesthesia protocol during the study

RIPHeart Study 2012 recalculated the sample size during the inclusion period and reduced the total number of patients to include

The authors of McCrindle 2014 were shareholders in a company producing a remote ischaemic preconditioning device.

Czibik‐stable 2008, Czibik‐unstable 2008, Li 2013, Luchinetti 2012, Thielmann 2010, Walsh 2010, and Zimmerman 2011 did not report their funding source and were classified as unclear risk of bias. All remaining 21 studies adequately reported their funding sources and there were no other concerns.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

For consistency regarding the direction of effects, continuous outcomes with negative values, and dichotomous outcomes with values less than one favour remote ischaemic preconditioning.

Primary outcome measures

Serum creatinine

Serum creatinine levels were reported in 15 studies (Ali 2007; Choi 2011; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; Huang 2013; Kim 2012a; Lee 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pepe 2013; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2010; Venugopal 2009; Walsh 2010), measured at 13 different time points postoperatively. In total, serum creatinine was measured in 707 patients undergoing remote ischaemic preconditioning and in 704 patients undergoing a control intervention. Based on high quality evidence remote ischaemic preconditioning had little of no effect on reducing serum creatinine on postoperative days one (Analysis 1.6 (14 studies, 1022 participants): MD ‐0.02 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.02; I2 = 21%), two (Analysis 1.8 (9 studies, 770 participants): MD ‐0.04 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.02; I2 = 31%), and three (Analysis 1.10 (6 studies, 770 participants): MD ‐0.05 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 68%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Serum creatinine, Outcome 6 Creatinine day 1.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Serum creatinine, Outcome 8 Creatinine day 2.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Serum creatinine, Outcome 10 Creatinine day 3.

We found a reduction in peak postoperative creatinine during the first three days in patients undergoing remote ischaemic preconditioning (Analysis 1.16 (3 studies, 365 participants): MD ‐0.10 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.01; I2 = 0%).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Serum creatinine, Outcome 16 Peak creatinine.

Complications and adverse effects related to ischaemic preconditioning

Data on adverse effects of the preconditioning stimulus were reported in 15 studies (Ali 2007; Candilio 2015; Choi 2011; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; ERICCA Study 2012; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Huang 2013; Kim 2012a; Lomivorotov 2012; Pavione 2012; Pepe 2013; Thielmann 2013; Walsh 2010), including a total of 1999 patients receiving remote ischaemic preconditioning and 1994 patients undergoing a control intervention. It is uncertain whether remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff inflation leads to increased adverse effects compared to control because the certainty of the evidence is low (Analysis 2.1 (15 studies, 3993 participants): RR 3.47; 95% CI 0.55 to 21.76; I2 = 0%). It should be noted that only two studies (ERICCA Study 2012; Walsh 2010) reported adverse events in the remote ischaemic preconditioning and control groups (6/1999 in the remote ischaemic preconditioning group and 1/1994 in the control group); 13 studies stated no adverse effects were observed in either group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adverse events related to remote ischaemic preconditioning, Outcome 1 Adverse events related to RIPC.

No serious adverse effects were reported in studies using a blood pressure cuff for remote ischaemic preconditioning induction. ERICCA Study 2012 reported skin petechiae at the time of the intervention (35/801 participants; 4.4%), which is considered to be a minor side effect and is therefore not included in this review. Severe adverse effects occurred only in patients in the experimental arm of the study by Walsh 2010, in which four patients receiving remote ischaemic preconditioning developed lower limb ischaemia due to the traumatic effects of vascular clamping of the iliac artery.

Secondary outcome measures

Need for dialysis

The need for dialysis was reported in 13 studies (Ali 2007; Choi 2011; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Li 2013; Lomivorotov 2012; Luchinetti 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pinaud 2016; Rahman 2010; Venugopal 2009; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011), including 1211 remote ischaemic preconditioning‐treated patients and 1206 patients undergoing a control intervention. Forty‐four patients in the remote ischaemic preconditioning group required dialysis versus 46 patients in the control group. Compared to control, remote ischaemic preconditioning made little or no difference to the need for dialysis (Analysis 3.1 (13 studies, 2417 participants): RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.37 to 1.94; I2 = 60%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Need for dialysis, Outcome 1 Need for dialysis.

Acute kidney injury (KDIGO, AKIN, RIFLE criteria)

There were no studies reporting AKI according to the KDIGO criteria.

Eight studies (Candilio 2015; Choi 2011; ERICCA Study 2012; Kim 2012a; Pinaud 2016; Venugopal 2009; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011) used the AKIN criteria to assess the incidence of AKI, including 1170 remote ischaemic preconditioning‐treated patients and 1194 patients undergoing a control intervention. Remote ischaemic preconditioning may have slightly improved the overall incidence of AKI (Analysis 4.1 (8 studies, 2364 participants): RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.00; I2 = 61%, high quality evidence), or when stratified for AKIN grade 1 (Analysis 4.2 (5 studies, 2135 participants): RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.11; I2 = 67%; high quality evidence), grade 2 (Analysis 4.3 (5 studies, 2135 participants): RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.24; I2 = 26%, high quality evidence), and grade 3 (Analysis 4.4 (5 studies, 2135 participants): RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.07; I2 = 11%, high quality evidence).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN, Outcome 1 Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN, Outcome 2 AKIN: grade 1.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN, Outcome 3 AKIN: grade 2.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN, Outcome 4 AKIN: grade 3.

Three studies (Pedersen 2012; RIPHeart Study 2012; Young 2012) reported data on the incidence of AKI according to the RIFLE criteria for 794 remote ischaemic preconditioning‐treated patients and 792 patients undergoing a control intervention. Remote ischaemic preconditioning made little of no difference to the overall incidence of AKI (Analysis 5.1 (3 studies, 1586 participants): RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.12; I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence) and when stratified for Risk (Analysis 5.2 (3 studies, 1586 participants): RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.03; I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence), Injury (Analysis 5.3 (3 studies, 1586 participants): RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.02, moderate quality evidence), or Failure (Analysis 5.4 (3 studies, 1586 participants): RR 1.09; 95% Cl 0.59 to 2.02; I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence). There were no events in either group for the RIFLE criteria of Loss and End‐stage kidney failure.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acute kidney injury defined by RIFLE, Outcome 1 RIFLE.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acute kidney injury defined by RIFLE, Outcome 2 RIFLE: R.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acute kidney injury defined by RIFLE, Outcome 3 RIFLE: I.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acute kidney injury defined by RIFLE, Outcome 4 RIFLE: F.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

Blood urea nitrogen was not reported as an outcome measure by any of the included studies.

Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL)

Two studies (Choi 2011; Pedersen 2012) reported serum NGAL levels measured post‐operatively on day one for 92 preconditioned and 89 control patients. Our meta‐analysis showed remote ischaemic preconditioning probably made little of no difference in reducing serum NGAL compared to control (Analysis 6.1 (2 studies, 181 participants): MD 0.57 ng/mL, 95% CI ‐2.65 to 3.79; I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Serum NGAL, Outcome 1 NGAL day 1.

Pedersen 2012 also measured serum NGAL post‐operatively at six and 12 hours, and on days two and three, and reported no difference between the groups for any of these time points.

Zarbock 2015, reported urine NGAL was reduced in patients undergoing remote ischaemic preconditioning, when measured four, 12 and 24 hours after surgery (Analysis 7.1; Analysis 7.2; Analysis 7.3).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Urine NGAL, Outcome 1 Urine NGAL 4 hours.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Urine NGAL, Outcome 2 Urine NGAL 12 hours.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Urine NGAL, Outcome 3 Urine NGAL day 1.

Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1)

KIM‐1 was not reported as an outcome measure by any of the included studies.

Mortality

Twenty four studies (Ali 2007; Candilio 2015; Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008; ERICCA Study 2012; Hong 2012; Hong 2014; Kim 2012a; Li 2013; Lomivorotov 2012; Luchinetti 2012; McCrindle 2014; Pavione 2012; Pedersen 2012; Pepe 2013; Rahman 2010; Slagsvold 2014; Thielmann 2010; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009; Walsh 2010; Young 2012; Zarbock 2015; Zimmerman 2011) reporting mortality in 2467 patients receiving remote ischaemic preconditioning and 2464 control patients. We included data on all‐cause mortality to 30 days and all‐cause in‐hospital mortality in our analysis. When both in‐hospital mortality and 30‐day mortality were reported (Zarbock 2015), in‐hospital mortality was used in the analysis. Mortality after a longer postoperative period and mortality due to a specific condition or disease were excluded. Remote ischaemic preconditioning made little of no difference to decreasing all‐cause mortality (Analysis 8.1 (24 studies, 4931 participants): RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.37; I2 = 0%, high quality evidence).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Mortality, Outcome 1 Mortality.

Quality of life

Quality of life was not reported as an outcome measure by any of the included studies.

Length of hospital stay

Eight studies (Ali 2007; Candilio 2015; Choi 2011; Hong 2012; Kim 2012a; Thielmann 2010; Thielmann 2013; Venugopal 2009) report data on the length of hospital stay, including a total of 457 remote ischaemic preconditioning‐treated patients and 463 patients undergoing a control intervention. Remote ischaemic preconditioning made little or no difference to the length of hospital stay (Analysis 9.1 (8 studies, 920 participants): MD 0.17 days, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.80; I2 = 49%, high quality evidence).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Length of hospital stay, Outcome 1 Length of hospital stay.

Subgroup analyses

We aimed to perform subgroup analyses for our primary outcome measures, for all subgroups containing two or more studies. Adverse effects occurred only in six patients in two studies (ERICCA Study 2012; Walsh 2010), and as a consequence, RR could only be calculated for these two studies. Therefore, no subgroup analysis was performed for this outcome measure. The following subgroup analyses therefore only concern serum creatinine on postoperative day one, two and three. All subgroup analysis results are shown in Table 2.

1. Subgroup analyses.

| Subgroups | Creatinine day 1 post‐op (mg/dL) | Creatinine day 2 post‐op (mg/dL) | Creatinine day 3 post‐op (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Number of studies | MD [95% CI] | I2 | Number of studies | MD [95% CI] | I2 | Number of studies | MD [95% CI] | I2 | |

| Total | 14 | ‐0.02 [‐0.05 to 0.02] | 21% | 9 | ‐0.04 [‐0.09 to 0.02] | 31% | 6 | ‐0.05 [‐0.19 to 0.10] | 68% |

| Age | |||||||||

| Adults | 10 | ‐0.02 [‐0.09 to 0.05] | 28% | 6 | ‐0.01 [‐0.08 to 0.06] | 0% | 5 | ‐0.07 [‐0.24 to 0.09] | 73% |

| Children | 4 | ‐0.02 [‐0.06 to 0.02] | 22% | 3 | ‐0.05 [‐0.16 to 0.06] | 55% | 1 | ‐‐ | NA |

| Total duration of ischaemia | |||||||||

| 15 minutes | 3 | ‐0.02 [‐0.10 to 0.06] | 0% | 3 | ‐0.04 [‐0.14 to 0.06] | 0% | 2 | ‐0.09 [‐0.28 to 0.09] | 41% |

| 20 minutes | 7 | ‐0.02 [‐0.07 to 0.03] | 42% | 5 | ‐0.03 [‐0.13 to 0.08] | 60% | 3 | ‐0.09 [‐0.44 to 0.27] | 82% |

| 30 minutes | 2 | 0.04 [‐0.16 to 0.25] | 49% | 1 | ‐‐ | NA | 1 | ‐‐ | NA |

| Number of RIPC cycles | |||||||||

| 2 cycles | 4 | ‐0.14 [‐0.27 to ‐0.02] | 0% | 1 | ‐‐ | NA | 1 | ‐‐ | NA |

| 3 cycles | 5 | 0.01 [‐0.06 to 0.08] | 0% | 4 | ‐0.03 [‐0.11 to 0.05] | 0% | 3 | ‐0.05 [‐0.15 to 0.06] | 12% |

| 4 cycles | 5 | ‐0.01 [‐0.05 to 0.03] | 24% | 4 | ‐0.02 [‐0.12 to 0.08] | 63% | 2 | 0.12 [‐0.00 to 0.24] | 0% |

| Method of RIPC induction | |||||||||

| Blood pressure cuff upper arm | 4 | ‐0.03 [‐0.08 to 0.01] | 0% | 4 | ‐0.08 [‐0.13 to ‐0.02] | 0% | 2 | ‐0.09 [‐0.28 to 0.09] | 41% |

| Blood pressure cuff lower limb | 6 | 0.01 [‐0.04 to 0.06] | 25% | 4 | 0.01 [‐0.08 to 0.10] | 35% | 3 | 0.06 [‐0.03 to 0.15] | 0% |

| Aortic or iliac artery clamping | 4 | ‐0.14 [‐0.27 to ‐0.02] | 0% | 1 | ‐‐ | NA | 1 | ‐‐ | NA |

| Type of surgery | |||||||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 2 | ‐0.27 [‐0.60 to 0.06] | 25% | 1 | ‐‐ | NA | 1 | ‐‐ | NA |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 6 | ‐0.02 [‐0.08 to 0.05] | 0% | 4 | ‐0.00 [‐0.08 to 0.08] | 0% | 3 | ‐0.01 [‐0.19 to 0.16] | 66% |

| Other types of cardiac surgery | 6 | ‐0.01 [‐0.05 to 0.04] | 34% | 4 | ‐0.05 [‐0.13 to 0.03] | 42% | 2 | 0.01 [‐0.10 to 0.13] | 0% |

RIPC ‐ remote ischaemic preconditioning

Age

We stratified the included studies according to participants' age (child or adult). There was no effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on serum creatinine on day one, two or three postoperatively in any of the subgroups, and no difference in treatment effect between subgroups. Compared to the overall analysis of serum creatinine on postoperative day two, heterogeneity was reduced in the subgroup of studies performed in adults, while heterogeneity in the subgroup of children increased to high. No change in heterogeneity was observed on for serum creatinine on day one and three.

Sex

Subgroup analysis could not be performed, since none of the studies reported separate outcomes for men and women and no individual patient data were retrieved.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning protocol

There were seven different remote ischaemic preconditioning protocols used in the studies, but only three different remote ischaemic preconditioning protocols were used in more than one study. We stratified the protocols according to the total duration of ischaemia and the number of remote ischaemic preconditioning cycles (Table 2).

For total duration of ischaemia, the subgroups of 15, 20 and 30 minutes contained two or more studies and were included in the analysis. The subgroup of four minutes total ischaemia was not analysed since it contained two comparisons from the same study (Czibik‐stable 2008; Czibik‐unstable 2008). There was no effect of treatment on serum creatinine on day one, two or three postoperatively in any of the subgroups, and no difference in treatment effect between subgroups.

Compared to the overall analysis, heterogeneity was reduced in the 15 minutes subgroup, but increased in the other subgroups, on all three postoperative days.

For the number of preconditioning cycles, the subgroups of two, three, and four cycles contained two or more studies and were included in the analysis. In the subgroup of two preconditioning cycles, serum creatinine was reduced on postoperative day one, while there was no effect of treatment on this day in the subgroups of three and four cycles. However, the confidence intervals overlapped between all subgroups. No effect of treatment and no differences between subgroups were observed for serum creatinine on postoperative days two and three.

Heterogeneity in the subgroups was similar to the overall analysis on day one, was increased in the four cycles subgroup on day two, and was reduced in all subgroups on day three.

Method of remote ischaemic preconditioning induction

The type and amount of tissue used to induce the remote ischaemic preconditioning stimulus may influence its efficacy in reducing kidney damage. Often, the preconditioning stimulus is applied to an extremity, by inflating a blood pressure cuff around an upper or lower limb. Alternatively, atraumatic vascular clamping of the aorta or iliac artery may be used. We therefore stratified the studies according to the method of remote ischaemic preconditioning induction, creating three subgroups: blood pressure cuff on the upper arm, blood pressure cuff on the lower limb or clamping of the aorta or iliac artery (Table 2).

On postoperative day one, there was no effect of treatment in the subgroups using blood pressure cuff occlusion, but serum creatinine was reduced in the subgroup of studies using vascular clamping. On postoperative day two, serum creatinine was reduced in the subgroup using blood pressure cuff occlusion of the upper arm, but not in the lower limb subgroup. On postoperative day three, there was no effect of treatment in any of the groups. Importantly, the confidence intervals of all subgroups overlapped on each postoperative day.

Heterogeneity in the subgroups was similar to the overall analysis for postoperative day one and two, and reduced in both subgroups on day three.

Type of surgical procedure

The type of surgery is a major determinant of the risk and severity of perioperative kidney injury, which may influence remote ischaemic preconditioning efficacy. The type of surgery may also correlate to a type of patient with a specific susceptibility to kidney injury. Studies were stratified according to the type of surgery performed, including abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, coronary artery bypass grafting, and other types of cardiac surgery (Table 2). Only Huang 2013 reported partial nephrectomy and was excluded from this subgroup analysis.

There was no effect of treatment on serum creatinine on day one, two or three postoperatively in any of the subgroups, and no difference in treatment effect between subgroups.

Compared to the overall analysis, heterogeneity in the subgroup of cardiac surgery was increased on day one and day two, but decreased on day three. Heterogeneity in the other subgroups and days was similar or decreased compared to the overall analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Excluding studies of lower quality with regard to the primary outcome measures had no significant effect on the results of this meta‐analysis. Excluding studies of less than 30 patients in each group showed no significant difference in primary outcome measures.

Publication bias

We aimed to construct funnel plots to assess publication bias for the primary outcome measures. For adverse events and creatinine on postoperative day three, there were ≤ 6 data points, which were considered insufficient to reliably assess funnel plot asymmetry. Our assessment of the funnel plot of serum creatinine data on postoperative day one and two (Figure 5; Figure 6) showed signs of publication bias, with small studies predominantly showing positive results.

Summary of findings table

The summary of findings table can be found at: Table 1.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our search identified 28 studies investigating the effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on kidney outcomes in patients undergoing surgery associated with kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury. Our primary endpoints showed no protective effect for remote ischaemic preconditioning application. Adverse effects were found in one study after vascular clamping to induce remote ischaemic preconditioning. The general method using cuff inflation on the upper arm or thigh showed no difference in serious adverse effects. Furthermore, the secondary outcomes ‐ need for dialysis, AKI indicated by RIFLE or AKIN criteria, serum NGAL, mortality and length of hospital stay ‐ were unchanged in patients undergoing remote ischaemic preconditioning when compared with controls. One study reported urinary NGAL was significantly reduced in the remote ischaemic preconditioning group (Zarbock 2015).

We found that a significant effect was seen regarding the method of remote ischaemic preconditioning induction. The subgroup of Invasive clamping of arteries to induce remote ischaemic preconditioning is more effective compared to non‐invasive cuff inflation. However, this observation should be interpreted with care, since invasive remote ischaemic preconditioning induction included only three studies, one of which (Ali 2007) introduced high heterogeneity in the data‐set. Subgroup analysis indicated that age, type of surgery, site of preconditioning, number of cycles and duration of the remote ischaemic preconditioning protocol did not influence remote ischaemic preconditioning efficacy.

Overall we conclude that after major surgery associated with kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury, remote ischaemic preconditioning does not significantly reduce kidney injury. Based on these data, routine use of remote ischaemic preconditioning in major surgery cannot be justified.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The heterogeneity of the outcome measurements and surgical procedures makes them difficult to compare. Of note, local ischaemic preconditioning, which has been shown to be highly effective in animal models (Wever 2012), has not been studied in patients and its feasibility therefore remains unclear.

Because of expected differences in the underlying mechanism of kidney injury, studies including patients undergoing kidney transplantation or interventions using nephrotoxic contrast media were excluded from this review. Despite inclusion of 28 studies, the primary outcome measures were heterogeneous and this severely hampered our meta‐analysis. Therefore, we advocate a more standardised primary outcome measure in future studies.

Many studies, as well as our meta‐analysis, focused on serum creatinine as the primary outcome. However, the use of this outcome measure as a gold standard for kidney injury is under debate (Waikar 2012) and its relationship with the long‐term quality of life is not straightforward. Only a few studies assessed the effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on long‐term outcome measures such as quality of life and long term mortality.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence provided by the included studies was moderate to high. Including data from studies of lower quality may lead to an overestimation of treatment effects, since low‐quality studies generally overstate efficacy. Excluding studies of lower quality did not affect the primary outcomes. Therefore, after performing the risk of bias assessment we included all available data in our analysis.

One important aspect in the quality of the evidence and potential bias is the funding of the studies which might influence the outcome. Influential funding was reported by one study and seven studies did not report their funding sources, which is a source of potential bias.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to identify all relevant studies through comprehensive, systematic searching of the literature in multiple databases, as well as contacting authors to obtain additional publications and data. Still we could not exclude the presence of publication bias in our data‐set.

Data extraction was completed independently by two authors without conflicts of interest regarding the outcome, thereby avoiding potential bias. We performed several subgroup analyses. However, since our approach is observational rather than experimental, their results should be regarded as hypothesis generating. This meta‐analysis was slightly hampered by missing data, resulting from studies reporting outcome data as medians and interquartile ranges. We were unable to obtain raw data for a number of these studies, and this may have biased our analysis.

In summary, we consider this review to be influenced by missing data and an unclear risk of publication bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are comparable with other meta‐analyses in the literature (D'Ascenzo 2012; Desai 2011; Yang 2014) despite differences in inclusion criteria (i.e. others included contrast studies and did not include studies in children). The negative result from this review contradicts the overall beneficial effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning in animal models of kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury. A meta‐analysis of animal studies by Wever 2012 showed that remote ischaemic preconditioning was successful in reducing kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury. Possible explanations for the discrepancy between human and animal studies are:

The lower amount of kidney injury in human studies compared with experimental models of kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury. This review (Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.10) showed that postoperative serum creatinine levels among control groups were comparable with normal serum creatinine values. When there is limited kidney damage, very large numbers of patients are required to show a significant reduction by remote ischaemic preconditioning. The ischaemia reperfusion injury applied to the kidney in the animal models is much more severe compared to the amount of kidney injury in human studies. Most animal studies have a single kidney model where the pedicle is clamped for 45 minutes (Wever 2012). For such an amount of kidney damage there is no comparable human patient group. Although kidney transplant recipients were not addressed in this review, kidneys from deceased donors are exposed to prolonged periods of (cold) ischaemia. Therefore, it may be interesting to pursue remote ischaemic preconditioning efficacy in those patients.

Animal studies generally use healthy young animals (Wever 2012); studies included in this review mostly recruited aged patients with significant comorbidity. Aging and comorbidity significantly reduce the effectiveness of remote ischaemic preconditioning in human models of ischaemia reperfusion injury (Engbersen 2012; Seeger 2014; van den Munckhof 2013). Experimental studies using animals with diabetes and hypertension confirm a decreased effectiveness of remote ischaemic preconditioning compared with healthy animals (Przyklenk 2011). Furthermore, studies in the present review may have included patients suffering from pathologies which induce temporary (mild) ischaemia of remote tissues, e.g. unstable angina or claudication. Such episodes could induce a protective remote preconditioning effect on kidney's ischaemia reperfusion injury, which may have abolished the protective effect of the experimental preconditioning stimulus.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning by cuff inflation appears to be a safe method, and probably leads to little or no difference in serum creatinine, adverse effects, need for dialysis, length of hospital stay, death and in the incidence of acute kidney injury. Overall we have moderate‐high certainty evidence however the available data did not confirm the efficacy of remote ischaemic preconditioning in reducing renal ischaemia reperfusion injury in patients undergoing major cardiac and vascular surgery in which renal ischaemia reperfusion injury may occur.

Implications for research.

Future RCTs should focus on patients undergoing a procedure that is associated with significant kidney ischaemia reperfusion injury, such as open abdominal aortic or kidney transplant surgery. Furthermore, fundamental research is required to be able to predict the protective effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning and to increase the efficacy of the preconditioning protocol in humans.

Future studies should be adequately powered and designed with undisputed endpoints such as need for dialysis, mortality and/or quality of life, rather than short‐term kidney function. Markers of (subtle) ischaemic kidney injury are useful for research purposes, but should be secondary to long‐term clinically pertinent outcome measures.

Studies need to report methods of allocation, blinding and outcome data in detail and should publish a predefined study protocol. Doing so will increase study quality and make the conclusions more applicable to clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Hausenloy, Yellon, Nicholas, Kim, McCrindle, Pavione and Slagvold for supplying valuable additional information and data of their primary studies. We would like to acknowledge the referees for their assessments and suggestions.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE (OVID SP) |

|

| EMBASE (OVID SP) |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Serum creatinine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Creatinine: 1 hour | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 CABG | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Creatinine: 3 hours | 2 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.05] |

| 2.1 Cardiac surgery | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.06] |

| 2.2 AAA | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.40, 0.16] |

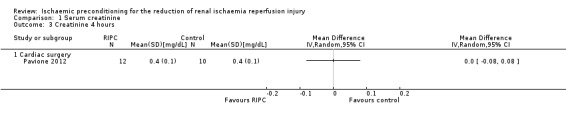

| 3 Creatinine 4 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Cardiac surgery | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Creatinine 6 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 CABG | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Creatinine 12 hours | 3 | 115 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.07, 0.02] |

| 5.1 Cardiac surgery | 2 | 62 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.07, 0.02] |