Abstract

Background

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia (a drop in core temperature to below 36°C) occurs because normal temperature regulation is disrupted during surgery, mainly because of the effects of anaesthetic drugs and exposure of the skin for prolonged periods. Many different ways of maintaining body temperature have been proposed, one of which involves administration of intravenous nutrients during the perioperative period that may reduce heat loss by increasing metabolism, thereby increasing heat production.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of preoperative or intraoperative intravenous nutrients in preventing perioperative hypothermia and its complications during surgery in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; November 2015) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE, Ovid SP (1956 to November 2015); Embase, Ovid SP (1982 to November 2015); the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science (1950 to November 2015); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, EBSCO host; 1980 to November 2015), as well as the reference lists of identified articles. We also searched the Current Controlled Trials website and ClincalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of intravenous nutrients compared with control or other interventions given to maintain normothermia in adults undergoing surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each included trial, and a third review author checked details if necessary. We contacted some study authors to request additional information.

Main results

We included 14 trials (n = 565), 13 (n = 525) of which compared intravenous administration of amino acids to a control (usually saline solution or Ringer's lactate). The remaining trial (n = 40) compared intravenous administration of fructose versus a control. We noted much variation in these trials, which used different types of surgery, variable durations of surgery, and different types of participants. Most trials were at high or unclear risk of bias owing to inappropriate or unclear randomization methods, and to unclear participant and assessor blinding. This may have influenced results, but it is unclear how results might have been influenced.

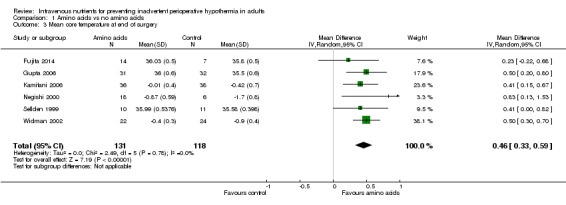

No trials reported any of our prespecified primary outcomes, which were risk of hypothermia and major cardiovascular events. Therefore, we decided to analyse data related to core body temperature instead as a primary outcome. It was not possible to conduct meta‐analysis of data related to amino acid infusion for the 60‐minute and 120‐minute time points, as we observed significant statistical heterogeneity in the results. Some trials showed that higher temperatures were associated with amino acids, but not all trials reported statistically significant results, and some trials reported the opposite result, where the amino acid group had a lower core temperature than the control group. It was possible to conduct meta‐analysis for six studies (n = 249) that provided data relating to the end of surgery. Amino acids led to a statistically significant increase in core temperature in comparison to those receiving control (MD = 0.46°C 95% CI 0.33 to 0.59; I2 0.0%; random‐effects; moderate quality evidence).

Three trials (n = 155) reported shivering as an outcome. Meta‐analysis did not show a clear effect, and so it is uncertain whether amino acids reduce the risk of shivering (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.00; I2 = 93%; random‐effects model; very low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Intravenous amino acids may keep participants up to a half‐degree C warmer than the control. This difference was statistically significant at the end of surgery, but not at other time points. However, the clinical importance of this finding remains unclear. It is also unclear whether amino acids have any effect on the risk of shivering and if intravenous nutrients confer any other benefits or harms, as high‐quality data about these outcomes are lacking.

Plain language summary

Giving intravenous nutrients to adults during surgery to prevent hypothermia

Review question

We wanted to find out about the effects that intravenous nutrients (amino acids or sugars given into the bloodstream through a tube or a catheter in a vein) have on adults having surgery. Giving intravenous nutrients increases a person's metabolism, and this may increase the body heat produced. We wanted to know if giving intravenous nutrients during a surgical procedure could keep people warm, and if intravenous nutrients can keep them from having problems caused by being cold.

Background

People can get cold during surgery, particularly because of the drugs that are used to stop them from feeling pain and that keep them unconscious (anaesthetics). These drugs change how blood flows around the body, which can lead to heart problems and can cause wounds to heal more slowly. It may also cause blood to clot more slowly, and can make some drugs have uncertain effects. People can shiver when they wake from anaesthesia and often comment that this is a very uncomfortable experience. Keeping people warm may stop them from shivering. There are many ways of trying to keep people warm during surgery, including giving them intravenous nutrients.

Study characteristics

We looked for evidence up to November 2015. We included 14 randomized studies (involving 565 participants). Thirteen studies compared people who received normal care with additional intravenous amino acids against people who received normal care but no amino acids (the control group). One study compared people who received fructose with those in a control group. Studies involved adults undergoing planned or emergency surgery. We did not include studies in which participants were deliberately kept cold during surgery, were receiving skin grafts or were under local anaesthetic.

Key results

We can be certain that at the end of surgery, people receiving intravenous nutrients are up to a half‐degree warmer than people receiving control (based on evidence from six studies involving 249 participants). However, there was more uncertainty about the effects of intravenous nutrients at other time points, with some studies suggesting that intravenous nutrients keep participants warmer and other studies reporting that participants were colder than those receiving the control. We are uncertain if keeping people up to half a degree warmer is important to those involved in caring for people who are having surgery. We are also uncertain if giving intravenous nutrients reduces the risk of people shivering (based on evidence from three studies involving 155 participants).

Quality of the evidence

Most of the evidence was moderate to low in quality. The methods used to assign participants to treatment groups was often inadequate or unclear, and we were uncertain if the people assessing outcomes were aware of which treatment group participants were in. This may have biased the results, but we are unsure what effect it may have had on results overall.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings table.

| Patient or population: adults undergoing surgery. Setting: hospital surgical settings in which general and/or regional anaesthesia is used (Japan, Sweden, India, Turkey, China, Egypt) Intervention: amino acids Comparison: no amino acids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no amino acids | Risk with amino acids | |||||

| Risk of hypothermia ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | (no studies) | ‐ | No trials reported this outcome. |

| Mean core temperature, 60 minutes | Not estimable | Not estimable | ‐ | 363 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | We did not calculate a pooled effect owing to high heterogeneity. |

| Mean core temperature, 120 minutes | Not estimable | Not estimable | ‐ | 347 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | We did not calculate a pooled effect owing to high heterogeneity. |

| Mean core temperature at the end of surgery | Mean core temperature at the end of surgery was 35.6°C based on data presented in 3 studies. The other studies presented change from baseline data only. | Mean core temperature at the end of surgery in the intervention group was 0.46°C higher (0.33 higher to 0.59 higher). | 0.46°C higher (0.33 to 0.59) | 249 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Shivering | Study population | RR 0.36 (0.13 to 1.00) | 155 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | I2 was high, but effects were in the same direction, so we judged inconsistency to be not serious. However, this estimate was very imprecise. | |

| 986 per 1000 | 355 per 1000 (128 to 986) | |||||

| Major cardiovascular event ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | (no studies) | ‐ | No trials reported this outcome. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect but may be substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aAllocation concealment was generally unclear, as was blinding of outcome assessors ‐ downgraded one level.

bVery serious inconsistency (high I2 and variable direction of effect) ‐ downgraded two levels.

cVery serious imprecision (high I2 and wide confidence intervals) ‐ downgraded two levels.

Background

Description of the condition

Regulation of temperature

Body temperature is usually maintained at between 36.5ºC and 37.5ºC by balancing the body’s heat losses and gains. Heat is gained as a product of metabolism, including that associated with muscular activity, and is lost through convection, conduction and radiation from the skin, as well as by evaporation through sweating.

To maintain this balance, information from temperature sensors in deep tissues, and in the skin, is processed by the brain. Heat loss is increased through sweating and as a result of increased blood flow through the skin. Heat loss is reduced when blood flow through the skin is reduced, and heat production is increased mainly when muscular activity (shivering) is induced.

A useful concept in thinking about heat regulation is that the body has a central compartment comprising the major organs, where temperature is tightly regulated, and a peripheral compartment, in which temperature varies widely. Typically, temperature at the periphery may be 2ºC to 4ºC cooler than in the core compartment.

Effects of perioperative care and anaesthesia on thermal regulation

Exposure of the skin and internal organs during the perioperative period can increase heat loss and use of cool intravenous and irrigation fluids; inspired or insufflated (blown into body cavities) gases may directly cool people.

Sedatives and anaesthetic agents inhibit the normal response to cold, whereby surface blood vessels are constricted, effectively resulting in increased blood flow to the periphery and increased heat loss. During early stages of anaesthesia, these effects mean that the core temperature is decreased rapidly as a result of redistribution of heat from the central compartment to the peripheral compartment. Early heat loss is followed by a more gradual decline that reflects ongoing heat loss.

With epidural or spinal analgesia, peripheral blockade of vasoconstriction below the level of the nerve block may result in ongoing heat loss. Paralysis below the level of the block prevents shivering.

The risk of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is widely variable, for example, reports from audits describe risks of 1.5% (Al‐Qahtani 2011) to 20% (Harper 2008). People most susceptible to heat loss include the elderly, people with higher anaesthetic risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class III to IV), people with cachexia (increased metabolism associated with cancer), burn victims, people with hypothyroidism and those affected by corticoadrenal insufficiency.

Complications associated with perioperative hypothermia

Hypothermia, by altering various systems and functions, may result in increased morbidity. People often comment on subsequent shivering upon awakening from anaesthesia as one of the most uncomfortable immediate postoperative experiences. Shivering originates as a response to cold and is the result of involuntary muscular activity that occurs with the objective of increasing metabolic heat (Sessler 2001).

Cardiac complications are principal causes of morbidity during the postoperative phase. Prolonged ischaemia (as a result of reduced blood flow) is usually associated with cellular damage. For this reason, it seems that treatment of factors that can lead to such complications, such as body temperature, is likely to be important. Hypothermia stimulates the release of noradrenaline, resulting in peripheral vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) and hypertension (Sessler 1991; Sessler 2001) ‐ factors that may favour or increase the chances of myocardial ischaemia. It appears that increased risk of cardiac complications can be reversed by maintenance of normothermia (Frank 1997).

Some studies have shown that intraoperative hypothermia accompanied by vasoconstriction constitutes an independent factor that slows wound healing and increases the risk of surgical wound infection (Kurz 1996; Melling 2001).

Even moderate hypothermia (35ºC) can alter physiologic coagulation mechanisms by affecting platelet function and modifying enzymatic reactions. Decreased platelet activity produces an increase in bleeding and a greater need for transfusion (Rajagopalan 2008). Moderate hypothermia can also reduce the metabolic rate, manifesting as a prolonged effect of certain drugs that are used during anaesthesia with some uncertainty about their effects. This is particularly significant in elderly people (Heier 1991; Heier 2006; Leslie 1995).

For the above reasons, inadvertent non‐therapeutic hypothermia is considered an adverse effect of general and regional anaesthesia (Bush 1995; Putzu 2007; Sessler 1991). Therefore, body temperature is frequently monitored to help maintain normothermia during surgery and to detect the appearance of unintended hypothermia in a timely way.

Description of the intervention

Intravenous nutrients used to attempt to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia.

How the intervention might work

Intravenous nutrients could prevent perioperative hypothermia by increasing the amount of heat an individual produces (thermogenesis), as infusion of nutrients may stimulate the body to metabolize infused nutrients and so produce heat.

Why it is important to do this review

Clinical effectiveness of the different types of devices that can be used for keeping people warm before, during, and after surgery has been assessed in a very extensive guideline commissioned by the National Insitute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK (NICE 2008). This report concluded that evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness is sufficient for recommendations to be made on the use of forced air warming to prevent, and treat, perioperative hypothermia. Nevertheless, most of the data in this report pertain to intermediate outcomes such as temperature. The search strategy for this report yielded evidence only until the year 2007, and so an updated search is needed.

This current review is one of a number of reviews in this area. Published Cochrane reviews have explored warming of gases used in minimally invasive abdominal surgery (Birch 2011), use of warmed and humidified inspired gases in ventilated adults (Kelly 2010), use of thermal insulation for preventing intraoperative hypothermia (Alderson 2014), use of warmed intravenous or irrigation fluids for preventing intraoperative hypothermia (Campbell 2015) and postoperative treatment of people with inadvertent hypothermia (Warttig 2014); reviews in preparation are looking into active warming (Urrútia 2011) and use of alpha‐2 adrenergic agonists for prevention of shivering after general anaesthesia (Nicholson 2014).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of preoperative or intraoperative intravenous nutrients in preventing perioperative hypothermia and its complications during surgery in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized controlled trials (such as allocation by alternation) of interventions used during the preoperative period (one hour before induction of anaesthesia), during the intraoperative period (total anaesthesia time) or at both times.

Types of participants

We included adults (over 18 years of age) undergoing elective and emergency surgery (including surgery for trauma) under general or regional (central neuraxial block) anaesthesia, or both.

We planned to analyse the following subgroups, if data allow: older people (> 80 years), pregnant women, ASA class I and II versus higher, duration of anaesthesia less than and longer than three hours, type (including opening thorax or abdomen versus not) and urgency (emergency or elective) of surgery.

The following groups were not covered:

Participants who have been treated with therapeutic hypothermia (e.g. use of cardiopulmonary bypass).

Participants undergoing operative procedures under local anaesthesia.

Participants with isolated severe head injury resulting in impaired temperature control.

Participants undergoing surgery for burns (e.g. for skin grafting).

Types of interventions

For this review, we focused on the following intravenous nutrients given with the intention of increasing heat production to prevent hypothermia, rather than for fluid replacement.

Amino acids.

Sugars.

Mixes of different nutrients.

Total nutrition.

We excluded comparisons of general versus regional anaesthesia.

The comparisons of interest were intravenous nutrients versus:

no intravenous nutrients; or

another type of intravenous nutrient.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Risk of hypothermia (mild, core temperature 35.0ºC to 35.9ºC; moderate, 34.0ºC to 34.9ºC; severe, < 34.0ºC) measured at the direct tympanic membrane, bladder, oesophagus, pulmonary artery, nasopharynx or rectum. We anticipated that this would be measured and reported in a variety of ways. We sought to collect temperatures for groups at one and two hours after induction of anaesthesia and at the end of the operation, or on arrival to postanaesthesia care. We also tried to collect data on risk of hypothermia at any time after induction of anaesthesia

Mean core temperature. We made a post hoc decision to include this outcome after we reviewed the evidence, as none of the included studies reported risk of hypothermia (see Differences between protocol and review)

Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

Secondary outcomes

Infection and complications of surgical wound (wound healing and dehiscence) as defined by trial authors

Pressure ulcers, as defined by trial authors

Bleeding complications (blood loss, transfusions, coagulopathy)

Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

Patient‐reported outcomes (i.e. shivering, anxiety, comfort in postsurgical wake‐up, etc.)

Shivering (observer reported). We made a post hoc decision to include this outcome upon reviewing the evidence, as none of the included studies described patient‐reported shivering or any other patient‐reported outcome (see Differences between protocol and review)

All‐cause mortality at the end of the trial

Length of stay (in postanaesthesia care unit, hospital)

Unplanned high dependency or intensive care admission

Adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To identify eligible randomized controlled clinical trials, we searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 30 November 2015) in the Cochrane Library (see Appendix 1); MEDLINE, Ovid SP (1956 to 30 November 2015;see Appendix 2); Embase, Ovid SP (1982 to 30 November 2015; see Appendix 3), the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science (1950 to 30 November 2015; see Appendix 4); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, EBSCO host; 1980 to 30 November 2015; see Appendix 5). In searching the databases, we used both subject headings and free‐text terms with no language or date restrictions. We adapted our MEDLINE search strategy for searching all other databases.

Searching other resources

We also searched the following databases of ongoing trials on 30 November 2015.

Current Controlled Trials.

Clinicaltrials.gov.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

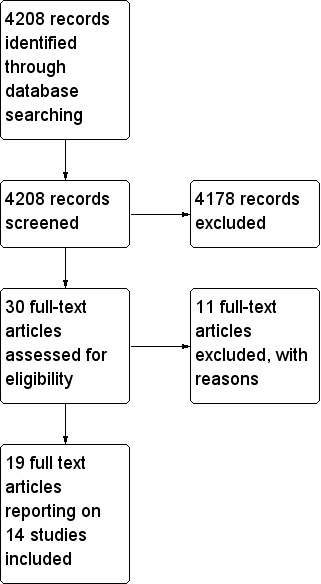

We (SW and PA) independently sifted the results of literature searches to identify relevant studies, so that two people reviewed each record. We did this once for all interventions and recorded the intervention on a data extraction form (see Appendix 6). We screened 4208 articles, 4178 of which we could exclude upon reading titles and abstracts. We retrieved a full copy of the articles that could not be excluded by review of title and abstract, and we excluded another 11 articles. This left 19 studies for inclusion (see study flow diagram in Figure 1). We listed all excluded studies and reasons for exclusion in a Characteristics of excluded studies table. We resolved disagreements about inclusion or exclusion by discussion, involving another review author (AS) as necessary.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We (PA and SW) extracted relevant data independently onto a data extraction form and resolved disagreements by discussion or by consultation with a clinical expert (AS).

One review author (SW) entered the data into RevMan, and a second review author (PA) checked for transcription errors.

We extracted the following data.

General information, such as title, authors, contact address, publication source, publication year and country.

Methodological characteristics and trial design.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of trial participants.

Description of the intervention and the control. We collected information about type of surgery, duration, surgical team experience and prophylactic antibiotic administration, when available.

Outcome measures as noted above.

Results for each trial group.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We (SW and PA) independently assessed risk of bias for each trial, including those identified by the NICE guideline (NICE 2008), and for newly identified studies, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by consultation with a third assessor (AS).

We considered a trial as having low risk of bias if all of the following criteria were assessed as adequate. We considered a trial as having high risk of bias if one or more of the following criteria were not assessed as adequate.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias): We described for each included trial the methods used to generate the allocation sequence if they were provided in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether comparable groups were produced. We assessed methods as adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table, computer random number generator); inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or unclear.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias): We described for each included trial the method used to conceal the allocation sequence, if it was provided in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed methods as adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); inadequate (open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation, date of birth); or unclear.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (checking for possible performance and detection bias): We described for each included trial the methods used, if any, to blind participants, personnel and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. If blinding was not possible, we will assess whether lack of blinding was likely to have introduced bias. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We assessed methods as adequate; inadequate; or unclear.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, drop‐outs, protocol deviations): We described for each included trial and for each outcome the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total number of randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion when reported and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. When sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses that we undertook. We considered intention‐to‐treat analysis as adequate if all drop‐outs or withdrawals were accounted for, and as inadequate if the number of drop‐outs or withdrawals was not stated, or if reasons for drop‐outs or withdrawals were not stated.

Selective reporting: We reported for each included trial which outcomes of interest were and were not reported. We did not plan to search for trial protocols.

Other bias: We described for each included trial any important concerns that we had about other possible sources of bias. We assessed whether each trial was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias: yes; no; or unclear.

With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of bias and whether we considered it likely to have an effect on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data by using risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and continuous data by using mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We expected that most trials would be randomized by individuals, but if cluster‐randomization was performed, we planned to follow advice provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We anticipated that other unit of analysis issues were unlikely because of the types of interventions provided and the choice of outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

When data were missing, we analysed available data on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before obtaining pooled estimates of relative effects, we carried out a statistical heterogeneity analysis by assessing the value of the I2 statistic, thereby estimating the percentage of total variance across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2002). We considered a value greater than 30% as a sign of important heterogeneity, and we proceeded to a meta‐analysis only if the direction of effect was the same for all point estimates. We explored sources of clinical heterogeneity through subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We recorded the numbers of included studies that reported each outcome. We used no statistical techniques to try to identify the presence of publication bias. We had planned to prepare a funnel plot and to analyse it by visual inspection if we found more than 10 trials for inclusion in a comparison. However, each comparison contained fewer than 10 trials, and so we did not do this.

Data synthesis

We used random‐effects model meta‐analyses (DerSimonian and Laird) of risk ratios in RevMan 5.3 with 95% confidence intervals. We analysed continuous data using mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals. .

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to consider subgroups based on demographic information (older people (> 80 years), pregnant women, ASA score class I and II vs higher), duration of anaesthesia and type and urgency of surgery. However, too few studies reported relevant data, and so we were not able to do this.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis according to methodologic trial quality (including only trials with low risk of bias), but lack of data prevented us from doing this.

Summary of findings tables and GRADE

We used the principles of the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the specific outcomes included in our review. This approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence on the basis of the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item assessed. Assessment of the quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodologic quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias. We used GRADE software to construct Table 1. We constructed a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach for the outcomes risk of hypothermia, major cardiovascular events, mean core temperature and observer‐reported shivering.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Figure 1 summarizes results of the search conducted in November 2015. Searches yielded a total of 4208 hits. For this review, we retrieved 30 papers for consideration and included 19 of them. Five of the trials were considered subgroups of a larger trial (Sellden 1999), and so we considered these together as a single trial. Therefore, we included evidence from 14 studies. We tried to contact the authors of two studies (Demir 2002; Gupta 2009) to clarify details, but we were not able to contact them.

Included studies

We included 14 studies (n = 565) overall. Thirteen studies (n = 525) compared amino acids versus a control (Demir 2002; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006; Gupta 2009; Kamitani 2006; Kanazawa 2008; Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Negishi 2000; Sahin 2002; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002; Zhong 2012), and one study (n = 40) compared fructose versus a control (Mizobe 2006) (see Characteristics of included studies).

Four of the included studies reported a factorial design where more than one amino acid group was compared with one or more control groups. Fujita 2014 compared amino acids alone or amino acids plus glucose versus control. Kamitani 2006, compared amino acids versus a control but reported results separately for surgery lasting 180 minutes or less, and for surgery lasting longer than 180 minutes. Negishi 2000 compared different doses of amino acids versus a single control, and Sellden 1999 compared amino acids administered at different times during the perioperative period versus a single control. In these cases, we pooled the amino acids groups (and the control groups, when more than one control group existed).

Participants in the included trials received general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or a combination of both. One trial investigated the effects of different anaesthetic agents on the effectiveness of intravenous nutrients (Gupta 2009). For this study, we pooled anaesthetic groups in the analyses.

Excluded studies

We excluded 11 studies (Aoki 2015; Baker 1984; Carlson 1994; Chandrasekaran 2004; Donmez 1997; Fujita 2012; Hyltander 1993; Ignaki 2003; Inoue 2011; Kamitani 2005; Ohe 2014) because trials were not randomized, intravenous nutrients were used in treating hypothermia, intravenous nutrients were not used during the perioperative period, interventions were not tested during surgical therapy or a control group was not used (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Ongoing studies

We identified no ongoing studies.

Studies awaiting classification

We found no studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

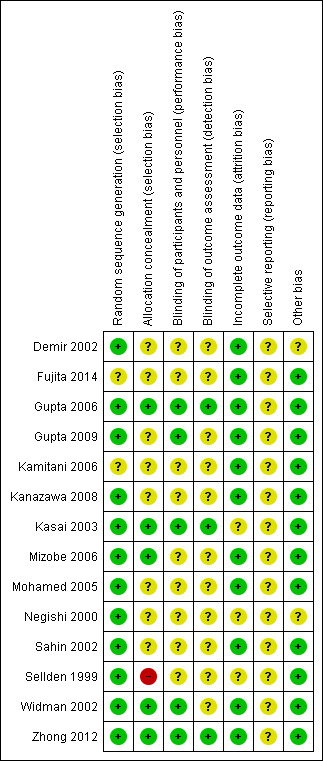

We provided summaries of risk of bias judgements in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Some trials (Demir 2002; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2009; Kamitani 2006; Kanazawa 2008; Mohamed 2005; Negishi 2000; Sahin 2002; Sellden 1999), used inappropriate randomization methods or did not report sufficient information to allow a judgement to be made, so it is unclear whether selection bias is present, and what effect this may have had on study results.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention and the fact that most participants were under general anaesthesia, participant blinding (or lack of) was considered unlikely to influence results. Most trials did not report whether outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation (Demir 2002; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2009; Kamitani 2006; Kanazawa 2008; Mizobe 2006; Mohamed 2005; Negishi 2000; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002). Although this could potentially bias the results, the direction of the effect that this would cause is unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Trials included in this review were relatively short in duration, and we identified no serious issues with attrition.

Selective reporting

We did not obtain and review trial protocols, so we identified no definitive reporting biases. Included studies often did not report the outcomes chosen for this review, but it is unclear whether these data were actually collected.

Other potential sources of bias

We identified no other definitive sources of potential bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Risk of hypothermia

None of the included trials reported this outcome.

Mean core temperature

Our review protocol did not prespecify this outcome (Alderson 2012). We made a post hoc decision to include data related to mean core temperature, as none of the included studies reported risk of hypothermia (see Differences between protocol and review). We decided to summarize data by presenting mean differences at 60 minutes, at 120 minutes and at the end of surgery.

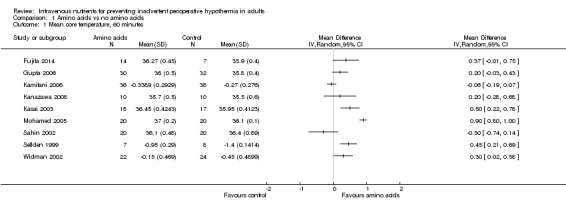

Amino acids versus control, 60 minutes

Nine trials (n = 363; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006; Kamitani 2006; Kanazawa 2008; Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Sahin 2002; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002) compared amino acid infusion versus a control and reported mean core temperature at 60 minutes. Pooled estimates of relative effects were obtained via a random‐effects model, resulting in I2 = 95%. This was above our prespecified threshold of 30%. In addition, the direction of effect was not the same for all point estimates. We noted no obvious reason for this heterogeneity and lacked power to investigate this further. Therefore we decided to refrain from pooling the results (Analysis 1.1). In Table 1, we downgraded the evidence for this outcome by one level for risk of bias and by two levels for inconsistency.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amino acids vs no amino acids, Outcome 1 Mean core temperature, 60 minutes.

For the four trials (n = 146) with statistically significant results (Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002) and the three trials (n = 103) with non‐statistically significant results (Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006; Kanazawa 2008), the direction of effect indicated that temperatures in the amino acids group were higher than those in the control group. However, two trials (n = 114; Kamitani 2006; Sahin 2002) reported results in the opposite direction by which the amino acids group had lower temperatures than the control group, although neither of these trials provided statistically significant results for this time point.

Demir 2002 (n = 18) also reported temperature outcomes at 60 minutes. The amino acids group (n = 9) had a mean core temperature of 35°C, and the control group (n = 9) had a mean core temperature of 34.7°C, but measures of dispersion were not reported. We chose not to estimate standard deviations for this trial.

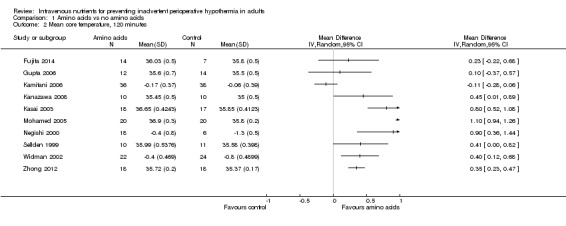

Amino acids versus control, 120 minutes

Ten trials (n = 347; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006; Kamitani 2006; Kanazawa 2008; Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Negishi 2000; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002; Zhong 2012) compared amino acid infusion versus a control and reported mean core temperature at 120 minutes. Pooled estimates of relative effects were obtained via a random‐effects model, resulting in I2 = 93%. This was above our prespecified threshold of 30%. In addition, the direction of effect was not the same for all point estimates. We noted no obvious reason for this heterogeneity and lacked power to investigate this further. Therefore, we decided to refrain from pooling the results (Analysis 1.2). In Table 1, we downgraded the evidence for this outcome by one level for risk of bias and by two levels for inconsistency.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amino acids vs no amino acids, Outcome 2 Mean core temperature, 120 minutes.

In general, groups receiving amino acids had higher core temperatures than control groups. This finding was statistically significant for seven trials (n = 226; Kanazawa 2008; Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Negishi 2000; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002; Zhong 2012) but was not statistically significant for two trials (n = 47; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006). One trial (n = 74; Kamitani 2006) reported results in the opposite direction by which the amino acids group had lower temperatures than the control group, although this result was not statistically significant.

Demir 2002 (n = 18) also reported temperature outcomes at 120 minutes. The amino acids group (n = 9) had a mean core temperature of 34.6°C, and the control group (n = 9) had a mean core temperature of 34.6°C, but measures of dispersion were not reported. Again, we chose not to estimate standard deviations for this trial.

Amino acids versus control, end of surgery

Six trials (n = 249; Fujita 2014; Gupta 2006; Kamitani 2006; Negishi 2000; Sellden 1999; Widman 2002) compared amino acid infusion versus a control and reported mean core temperature at the end of surgery; data were combined in a meta‐analysis via a random‐effects model (Analysis 1.3). All point estimates showed the same direction of effect, and no significant statistical heterogeneity was observed (I² = 0.0%;Chi2 P = 0 .78). Overall, at the end of surgery, amino acids were found to keep treated participants almost a half‐degree warmer than controls (MD 0.46°C, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.59). We downgraded evidence for this outcome by one level because of risk of bias judgements.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amino acids vs no amino acids, Outcome 3 Mean core temperature at end of surgery.

Fructose versus control

One trial (n = 40; Mizobe 2006) compared effects of administration of fructose (n = 10) versus saline (n = 10) on core body temperature. Results showed a statistically significant difference between groups, favouring the fructose group, at 60 minutes (MD 0.55°C, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.83) but not at 120 minutes (MD 0.80°C, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.1.15). At the end of surgery, temperature differences between the two groups were statistically significant, with the fructose group more than a half‐degree warmer than the group that did not receive fructose (MD 0.60°C, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.63).

Major cardiovascular complications

None of the included trials reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Infection and complications of the wound (wound healing and dehiscence)

No data were available for this outcome.

Pressure ulcers, as defined by trial authors

No data were available for this outcome.

Bleeding complications (blood loss, transfusions, coagulopathy)

Amino acids versus control

Four trials (n = 141; Kanazawa 2008; Kasai 2003; Mohamed 2005; Widman 2002) comparing amino acid infusion versus no amino acid infusion reported mean blood loss. We did not pool these results because of the wide range of estimated mean differences and the high level of heterogeneity.

Kasai 2003 reported blood loss in the amino acids group (n = 18, mean = 22 mL, standard error (SE) = 5) and in the saline group (n = 17, mean = 17 mL, SE = 5). Results showed no statistically significant differences between groups (MD 5.00 mL, 95% CI ‐8.86 to 18.86).

Mohamed 2005 reported blood loss in the amino acids group (n = 20, mean = 1200 mL, standard deviation (SD) = 400) and in the Ringer's solution group (n = 20, mean = 1600 mL, SD = 344). Participants in the amino acids group lost significantly less blood than those in the Ringer's solution group (MD ‐400 mL, 95% CI ‐619.13 to ‐180.87).

Widman 2002 reported blood loss in the amino acids group (n = 22, mean = 516 mL, SD = 272) and in the Ringer's solution group (n = 24, mean = 702 mL, SD = 344). Participants in the amino acids group lost significantly less blood than those in the Ringer's solution group (MD ‐186 mL, 95% CI ‐364.49 to ‐7.51).

Kanazawa 2008 reported blood loss in the amino acids with warmed fluids group (n = 10, mean = 408 g, SD = 454) and in the warmed fluids only group (n = 10, mean = 278 g, SD = 271). Results showed no significant differences in blood loss between the two groups (MD 130 g, 95% CI ‐197.71 to 457.71).

Fructose versus control

One trial (Mizobe 2006) reported blood loss in the fructose group (n = 10, mean = 275 g, SD = 93) and in the saline group (n = 10, mean = 238 g, SD = 79). Results showed no significant differences in blood loss between the two groups (MD 37 g, 95% CI ‐38.63 to 112.63).

Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

No data were available for this outcome.

Patient‐reported outcomes (i.e. shivering, anxiety, comfort in postsurgical wake‐up, etc.)

No data were available for any patient‐reported outcomes.

Shivering (observer rated)

Our review protocol (Alderson 2012) did not prespecify observer‐rated shivering as an outcome. We made a post hoc decision to include this outcome, as it was available in the evidence and we believed that it was important.

Amino acids versus control

Three studies (n = 155; Mohamed 2005; Sahin 2002; Sellden 1999) reported shivering in comparisons of amino acids versus control, and results were meta‐analysed via a random‐effects model (Analysis 1.4). Although I2 was 93%, estimates were in the same direction, and so we pooled the results. We found no statistically significant differences between groups (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.00), and we downgraded the evidence to very low quality for this outcome because of risk of bias, high heterogeneity and high imprecision of the results.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Amino acids vs no amino acids, Outcome 4 Shivering.

Fructose versus no fructose

Investigators did not report shivering.

All‐cause mortality at the end of the trial

No data were available for this outcome.

Length of stay (in postanaesthesia care unit, hospital)

Amino acids versus control

One trial (n = 75; Sellden 1999) reported length of hospital stay in the amino acids group (n = 45, mean = 6.4 days, SD = 0.3) compared with the control group (n = 30, mean = 8.2 days, SD = 0.7). This result was statistically significant, with participants in the amino acids group having a shorter length of stay than those in the control group (MD ‐1.80 days, 95% CI ‐2.07 to ‐1.53).

Fructose versus no fructose

Investigators did not report length of hospital stay.

Unplanned high dependency or intensive care admission

No data were available for this outcome.

Adverse effects

No data were available for this outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Most of the evidence included in this review was related to comparisons between amino acids and controls such as IV saline or Ringer's solution. One trial (Mizobe 2006) compared fructose versus saline. Overall the results of included evidence were mixed and could not be meta‐analysed owing to significant heterogeneity. We found no clear explanations for the heterogeneity and insufficient evidence to explore it statistically. It was possible to conduct a meta‐analysis for data related to the end of surgery time point. This analysis (Analysis 1.3) indicated that amino acids may keep people about a half‐degree warmer than the control and may reduce the risk of shivering, but it is unclear whether this result is clinically meaningful. We found similar results in the trial comparing fructose versus control (Mizobe 2006). Amino acids appear to reduce the incidence of shivering: Although results of this study were heterogeneous, and we must be cautious about interpreting the size of the effect, the direction of effect was consistent (Analysis 1.4).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Limited evidence was available overall, as most evidence was related to temperature outcomes only. Evidence related to key outcomes that we included in the review protocol was lacking, especially for adverse events, and so it is unclear whether the interventions were associated with any other benefits or harms.

The evidence included here was derived from trials involving a range of surgical situations and participant groups, and so study results are likely to be widely applicable. Subgroup analysis was not possible, and so it is unclear whether the effects of intravenous nutrients were different for different participant subgroups.

Quality of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence. For results that we decided to pool, the evidence was of moderate quality, mainly because of unclear randomization and assessor blinding methods. It is unclear what effect this had on study results. For results that we decided not to pool because of high heterogeneity, we judged the quality of the evidence to be very low, for the same reasons as above, with the addition of very serious inconsistency. In addition, trials often involved very few participants, and so it is likely that they were underpowered to detect meaningful differences in outcomes, especially for rare events such as mortality.

Potential biases in the review process

Some decisions related to the analysis, particularly those regarding including outcomes such as 'core temperature' and 'shivering', and investigations of heterogeneity were undertaken after the data were reviewed. Inclusion of core temperature as a primary outcome was a post hoc decision, and the choice of time points was based on the availability of data. These decisions may have introduced bias. Outcomes in Table 1 were chosen after results of the trials were noted, although this review included all primary outcomes even when no results were reported.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The National Insitute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline (NICE 2008) recommends forced air warming for people with a core temperature below 36°C, those considered at high risk of hypothermia and those undergoing surgery lasting longer than 30 minutes.

We found no evidence on the comparison of intravenous nutrients versus forced air warming, and so no evidence that would corroborate or refute the NICE guideline (NICE 2008). In addition, the NICE guideline recommendations were based on modelling of the effects of temperature differences on important patient outcomes and economic analyses; we have not attempted to replicate this analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Results of this review reveal moderate‐quality evidence suggesting that intravenous nutrients may make people about a half‐degree warmer than controls at the end of surgery. The clinical implications of these findings are unclear. It is also unclear whether intravenous nutrients offer a temperature advantage in relation to other warming methods. High‐quality evidence on important clinical outcomes is lacking.

Implications for research.

High‐quality randomized controlled trials are needed that should use high‐quality randomization methods and blinding of clinicians and outcome assessors. Trials should examine longer‐term and clinically important outcomes such as risk of clinically meaningful hypothermia and cardiovascular complications. Trials should also compare intravenous nutrients versus other warming methods.

Acknowledgements

This review builds on the work undertaken as part of the NICE clinical guideline on inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. We would like to acknowledge the work of this group.

We would like to thank Anna Lee (content editor), Jing Xie (statistical editor), Oliver Kimberger, Jonas Nygren, Tallie Casucci and Melissa Rethlefsen (peer reviewers), Janet Wale (consumer editor) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review

We would like to thank Anna Lee (Content Editor); Cathal Walsh (Statistical Editor); Oliver Kimberger, Janneke Horn and Rainer Lenhardt (Peer Reviewers); and Anne Lyddiatt (Consumer) for help and editorial advice provided during preparation of the protocol (Alderson 2012), for this systematic review .

We would also like to acknowledge Gillian Campbell's contribution to the original protocol (Alderson 2012).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL, the Cochrane Library

#1MeSH descriptor: [Hypothermia] explode all trees #2MeSH descriptor: [Body Temperature Regulation] explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor: [Piloerection] explode all trees #4MeSH descriptor: [Shivering] explode all trees #5hypo?therm*or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver* or ((thermal or temperature) near/2 (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)) or (low* near/2 temperature*) or thermo?genesis or ((reduc* or prevent*) and (temperature near/3 (decrease or decline))) or (heat near/2 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)) or (core near/2 (thermal or temperature*)) #6intravenous* or infusion* or IV or parenteral #7(#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5) and #6 #8MeSH descriptor: [Amino Acids] explode all trees #9nutrient* or amino acid* or fat* or glucose* or fructose* or electrolyte* or trace element* or vitamin* or Aminoplasmal* or Aminoven* or Clinimix* or ClinOleic* or Glamin* or Hyperamine* or Intralipid* or Kabiven* or Lipidem* or Lipfundin* or Nutriflex* or Nu TRIflex* or OliClinomel* or Omegaven* or Plasma‐Lyte* or Primene* or SMOFlipid* or StructoKabiven* or Structolipid* or Synthamin* or Vamin* or Vaminolact* #10#8 or #9 #11#7 and #10

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid SP)

#1 ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

#2 exp Hypothermia/ or exp body temperature regulation/ or exp piloerection/ or exp shivering/ or hypo?therm*.af. or normo?therm*.mp. or thermo?regulat*.mp. or shiver*.mp. or ((thermal or temperature) adj2 (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)).mp. or (low* adj2 temperature*).mp. or thermo?genesis.mp. or ((reduc* or prevent*).af. and (temperature adj3 (decrease or decline)).mp.) or (heat adj2 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)).mp. or (core adj2 (thermal or temperature*)).mp.

#3 (intravenous* or infusion* or IV or parenteral).mp.

#4 exp Amino Acids/ or (nutrient* or amino acid* or fat* or glucose* or fructose* or electrolyte* or trace element* or vitamin* or (Aminoplasmal* or Aminoven* or Clinimix* or ClinOleic* or Glamin* or Hyperamine* or Intralipid* or Kabiven* or Lipidem* or Lipfundin* or Nutriflex* or Nu TRIflex* or OliClinomel* or Omegaven* or Plasma‐Lyte* or Primene* or SMOFlipid* or StructoKabiven* or Structolipid* or Synthamin* or Vamin* or Vaminolact*)).mp.

#5 #3 and #4

#6 #1 and #2 and #5

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Embase (Ovid SP)

#1 (randomized‐controlled‐trial/ or randomization/ or controlled‐study/ or multicenter‐study/ or phase‐3‐clinical‐trial/ or phase‐4‐clinical‐trial/ or double‐blind‐procedure/ or single‐blind‐procedure/ or (random* or cross?over* or factorial* or placebo* or volunteer* or ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask*))).ti,ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

#2 exp Hypothermia/ or exp body temperature regulation/ or exp piloerection/ or exp shivering/ or hypo?therm*.af. or normo?therm*.mp. or thermo?regulat*.mp. or shiver*.mp. or ((thermal or temperature) adj2 (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)).mp. or (low* adj2 temperature*).mp. or thermo?genesis.mp. or ((reduc* or prevent*).af. and (temperature adj3 (decrease or decline)).mp.) or (heat adj2 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)).mp. or (core adj2 (thermal or temperature*)).mp.

#3 (intravenous* or infusion* or IV or parenteral).mp.

#4 exp Amino Acids/ or (nutrient* or amino acid* or fat* or glucose* or fructose* or electrolyte* or trace element* or vitamin* or (Aminoplasmal* or Aminoven* or Clinimix* or ClinOleic* or Glamin* or Hyperamine* or Intralipid* or Kabiven* or Lipidem* or Lipfundin* or Nutriflex* or Nu TRIflex* or OliClinomel* or Omegaven* or Plasma‐Lyte* or Primene* or SMOFlipid* or StructoKabiven* or Structolipid* or Synthamin* or Vamin* or Vaminolact*)).mp.

#5 #3 and #4

#6 #1 and #2 and #5

Appendix 4. Search strategy for ISI Web of Science

TOPIC: ((intravenous* or infusion* or IV or parenteral) and (nutrient* or amino acid* or fat* or glucose* or fructose* or electrolyte* or trace element* or vitamin* or (Aminoplasmal* or Aminoven* or Clinimix* or ClinOleic* or Glamin* or Hyperamine* or Intralipid* or Kabiven* or Lipidem* or Lipfundin* or Nutriflex* or Nu TRIflex* or OliClinomel* or Omegaven* or Plasma‐Lyte* or Primene* or SMOFlipid* or StructoKabiven* or Structolipid* or Synthamin* or Vamin* or Vaminolact*))) ANDTOPIC: ((hypo?therm* or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver*) or ((thermal or temperature) SAME (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)) or (low* SAME temperature*) or thermo?genesis or ((reduc* or prevent*) and temperature and (decrease or decline)) or (heat SAME (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)) or (core SAME (thermal or temperature*))) ANDTOPIC: (random* or (trial* SAME (control* or clinical*)) or placebo* or multicenter* or prospective* or ((blind* or mask*) SAME (single or double or triple or treble)))

Appendix 5. Search strategy for CINAHL (EBSCO host)

S27 S12 AND S21 AND S26

S26 S24 AND S25

S25 intravenous* or infusion* or IV or parenteral

S24 S22 OR S23

S23 nutrient* or amino acid* or fat* or glucose* or fructose* or electrolyte* or trace element* or vitamin* or (Aminoplasmal* or Aminoven* or Clinimix* or ClinOleic* or Glamin* or Hyperamine* or Intralipid* or Kabiven* or Lipidem* or Lipfundin* or Nutriflex* or Nu TRIflex* or OliClinomel* or Omegaven* or Plasma‐Lyte* or Primene* or SMOFlipid* or StructoKabiven* or Structolipid* or Synthamin* or Vamin* or Vaminolact*)

S22 (MH "Amino Acids")

S21 S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20

S20 core N3 (thermal or temperature*)

S19 heat N3 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)

S18 thermogenesis

S17 ( reduc* or prevent* ) and temperature and ( decrease or decline )

S16 low* N3 temperature*

S15 AB ((thermal or temperature) and (regulat* or manage* or maintain*))

S14 hypo?therm* or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver*

S13 (MM “Hypothermia”) OR (MM “Body Temperature Regulation”) OR (MM “Shivering”)

S12 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11

S11 (MH "Quantitative Studies")

S10 (MH "Quantitative Studies")

S9 (MH "Placebos")

S8 TX placebo*

S7 TX random* allocat*

S6 (MH "Random Assignment")

S5 TX ((singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*))

S4 TX ((singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*)) or TX ((trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*))

S3 TX clinic* n1 trial*

S2 PT Clinical trial

S1 (MH "Clinical Trials+")

Appendix 6. Data extraction form

| Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care Group Study selection, quality assessment & data extraction form Pharmacological agents for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia |

Code of paper: |

|

| Reviewer initials: | Date: | |

| First study author | Journal/Conference proceedings, etc, | Year |

| |

Study eligibility

| RCT/Quasi/CCT (delete as appropriate) | Relevant participants | Relevant interventions | Relevant outcomes |

| Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No* / Unclear |

* Issue related to selective reporting – when study authors may have taken measurements for particular outcomes but did not report these within the paper(s). Review authors should contact trialists for information on possible non‐reported outcomes and reasons for exclusion from publication. Study should be listed in ‘Studies awaiting assessment’ until clarified. If no clarification is received after three attempts, study should then be excluded.

| Do not proceed if any of the above answers is ‘No’. If study is to be included in ‘Excluded studies’ section of the review, record below the information to be inserted into the ‘Table of excluded studies’. |

| |

| Free‐hand space for comments on study design and treatment: |

Methodological quality

| Allocation of intervention | ||

| State here the method used to generate allocation and reasons for grading. (quote) | Grade (circle) | |

| Page no. | Adequate (random) | |

| Inadequate (e.g. alternate) | ||

| Unclear | ||

|

Concealment of allocation Process used to prevent foreknowledge of group assignment in an RCT, which should be seen as distinct from blinding | ||

| State here method used to conceal allocation and reasons for grading (quote) | Grade (circle) | |

| Page no. | Adequate | |

| Inadequate | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Blinding | Page no. | |

| Person responsible for participant care | Yes / No | |

| Participant | Yes / No | |

| Outcome assessor | Yes / No | |

| Other (please specify) | Yes / No | |

|

Intention‐to‐treat An intention‐to‐treat analysis is one in which all participants in a trial are analysed according to the intervention to which they were allocated, whether they received it or not. | ||

| Number of participants entering the trial | ||

| Number excluded | ||

| % excluded (greater than or less than 15%) | ||

| Not analysed as ‘intention‐to‐treat’ | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Were withdrawals described? | Yes / No / Not clear | |

| Free text: | ||

Participant and trial characteristics

| Participant characteristics | ||

| Additional details | Page no. | |

| Age (mean, median, range, etc.) | ||

| Sex of participants (numbers / %, etc.) | ||

| Trial characteristics | ||

| Additional details | Page no. | |

| Single centre / multi‐centre | ||

| Country / Countries | ||

| How was participant eligibility defined? | ||

| How many people were randomized? | ||

| How many people were analysed? | ||

| Control group (size and details, e.g. 2 cotton blankets + fluid warmer + HME) | ||

| Intervention group 1 (size and details) | ||

| Intervention group 2 (size and details) | ||

| Intervention group 3 (size and details) | ||

| Time treatment applied (e.g. 30 minutes preop) | ||

| Duration of treatment (mean + SD) | ||

| Total anaesthetic time | ||

| Duration of follow‐up | ||

| Time points when measurements were taken during the study | ||

| Time points reported in the study | ||

| Time points you are using in RevMan | ||

| Trial design (e.g. parallel / cross‐over*) | ||

| Other | ||

* If cross‐over design, please refer to the Cochrane Editorial Office for advice on how to analyse these data.

| Relevant outcomes | ||

| Reported in paper (circle) | Page no. | |

| Infection and complications of surgical wound | Yes / No | |

| Major CVS complications (CVS death, MI, CVA) | Yes / No | |

| Risk of hypothermia (core temp) | Yes / No | |

| Pressure ulcers | Yes / No | |

| Bleeding complications | Yes / No | |

| Other CVS complications (arrhythmias, hypotension) | Yes / No | |

| Patient‐reported outcomes (shivering, discomfort) | Yes / No | |

| All‐cause mortality | Yes / No | |

| Adverse effects | Yes / No | |

| Relevant subgroups | Page no. | |

| Age > 80 | Yes / No | |

| Pregnancy | Yes / No | |

| ASA scores | Yes / No | |

| Urgency | Yes / No | |

Subgroups

Number of participants

| Age > 80 | Pregnant | Elective | Urgent | ASA I or II | ASA III or IV | |

| Control | ||||||

| Intervention 1 | ||||||

| Intervention 2 | ||||||

| Intervention 3 | ||||||

| | ||||||

| Free text: | ||||||

| For continuous data | ||||||||||||||||

| Code of paper |

Outcomes |

Unit of measurement |

Control group | Intervention 1 (thermal insulation) | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | ||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Temperature at end of surgery | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Temperature at ................. | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Temperature at ................. | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Number of units red cells transfused | Units | |||||||||||||||

| For dichotomous data (n = no. of participants) | ||||||||||||||||

| Code of paper |

Outcomes |

Control group | Intervention 1 (thermal insulation) | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Free text | ||||||||||

| n | n | n | n | |||||||||||||

| Wound complications | ||||||||||||||||

| Major CVS complications (CVS death, non‐fatal MI, non‐fatal CVA and non‐fatal arrest) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bleeding complications (coagulopathy) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pressure ulcers | ||||||||||||||||

| Other CVS complications (hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension) | ||||||||||||||||

|

Other information that you feel is relevant to the results Indicate if any data were obtained from the primary author; if results were estimated from graphs, etc. or were calculated by you via a formula (this should be stated and the formula given). In general, if results not reported in paper(s) are obtained, this should be made clear here to be cited in the review. |

| |

| Free‐hand space for writing actions such as contact with study authors and changes |

References to trial

Check other references identified in searches. If you find additional references to this trial, link the papers now and list below. All references to a trial should be linked under one Study ID in RevMan.

| Code each paper | Study author(s) | Journal/Conference proceedings, etc. | Year |

References to other trials

| Did this report include any references to published reports of potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? | ||

| First study author | Journal / Conference | Year of publication |

| Did this report include any references to unpublished data from potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? If yes, list contact names and details. | ||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Amino acids vs no amino acids.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean core temperature, 60 minutes | 9 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Mean core temperature, 120 minutes | 10 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Mean core temperature at end of surgery | 6 | 249 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.33, 0.59] |

| 4 Shivering | 3 | 155 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 1.00] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Demir 2002.

| Methods | Single‐centre trial conducted in Turkey | |

| Participants | 27 patients scheduled for major abdominal surgery. Patients with metastatic malignant disease or secondary disease were not included. Premedication: 0.07 mg/kg midazolam, 0.5 mg morphine i.m. Induction of anaesthesia: 5 mg/kg pentothal, 0.1 mg/kg fentanyl, 0.1 mg/kg rocuronium Maintenance of anaesthesia: 1%‐2% isoflurane, 40% oxygen, 60% nitrous oxide Mean age: not stated Male/female: not stated |

|

| Interventions | No extra warming (n = 9): routine anaesthesia with conventional techniques. Intravenous fluids at room temperature. No extra warming or amino acids used Amino acids (n = 9): Freamin 17 amino acids solution via jugular vein infused at 143 mL/h throughout anaesthesia Warmed fluids (n = 9): intravenous fluids warmed to 37°C with Animec AM‐4 heater. This was stopped at the end of anaesthesia. |

|

| Outcomes | Rectal temperature and nasopharyngeal temperature (°C) every 30 minutes, pain scores, shivering | |

| Notes | This study was supported by hospital funds. Conflicts of interest are not reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Patients were randomly assigned to constitute 3 groups' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not assessed |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Study authors did not provide analysis of baseline characteristics; therefore, it is unclear if groups were equally matched. |

Fujita 2014.

| Methods | Single‐centre trial conducted in Japan | |

| Participants | 21 patients undergoing elective colectomy under general anaesthesia with ASA status I or II. Patients were excluded if they had history of diabetes and/or BMI > 30; preoperative receipt of sedatives, analgesics or antidepressants; preoperative C‐reactive protein level > 1.0 mg/dL; blood glucose level > 126 mg/dL and/or body temperature > 37.5ºC after anaesthetic induction; or surgical time > 500 minutes Premedication: none Induction of anaesthesia: 1.2‐2 mg/kg propofol, 2‐4 μg/kg fentanyl and 0.9 mg/kg rocuronium Maintenance of anaesthesia: 1%‐1.5% sevoflurane and continuous infusion of remifentanil (0.05‐0.25 μg/kg/min) For intraoperative pain control, a 5‐7 mL bolus of 0.375% ropivacaine was followed by a continuous infusion of 2 mL/h beginning 10 minutes before skin incision, and lasting until the end of surgery Mean age: control: mean = 68 years, SD = 9; amino acids only: mean = 68 years, SD = 10; amino acids + glucose: mean = 67 years, SD = 7 Male/female: control: 5 male, 2 female; amino acids only: 5 male, 1 female; amino acids + glucose: 3 male, 5 female |

|

| Interventions | Control (n = 7): Ringer's acetate solution at 5 mL/kg/h Amino acids only (n = 6): Ringer's acetate solution at 5 mL/kg/h plus 200 mL/h amino acids at 200 mL/h for 1.5 hours after surgery initiation Amino acids + glucose (n = 8): Ringer's acetate solution at 5 mL/kg/h plus amino acids at 200 mL/h for 1.5 hours after surgery initiation plus glucose infusion at 2 mg/kg/min administered at anaesthesia induction and for the duration of surgery All participants received forced air warming during surgery, which was set at 38ºC and was positioned over the precordium and upper limbs. All participants received up to 200 mg sugammadex to antagonize neuromuscular blockade and facilitate emergence from general anaesthesia. The operating room was maintained at 26ºC until anaesthesia induction; the room was then cooled to about 23ºC during surgery, then was warmed to 26ºC near the end of surgery. |

|

| Outcomes | Tympanic membrane temperature | |

| Notes | This research was funded by departmental sources. Conflict of interest was described, and none were declared. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not assessed |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns |

Gupta 2006.

| Methods | Single‐centre trial conducted in India | |

| Participants | 63 adults ASA grade I/II (aged 20‐60 years) admitted for elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Patients undergoing emergency surgery with known hepatic thyroid or renal disease, known allergy to study drug and BMI > 30 or < 20 kg/m² were excluded from the study. Premedication: 2 mcg/kg fentanyl Induction of anaesthesia: 5 mg/kg thiopental, 0.1 mg/kg vecuronium, 1.5% isoflurane, 66% nitrous oxide in oxygen Maintenance of anaesthesia: 0.8% isoflurane, 66% nitrous oxide in oxygen Mean age: 35.55 years, SD = 9.15 (amino acids); 38 years, SD = 13 (normal saline) Male/Female: 4/27 (amino acids); 6/26 (normal saline) |

|

| Interventions | Amino acid infusion (n = 31): continuous infusion administered in a micro drip set at a rate of 100 mL/h through a separate dedicated IV line. Ringer's lactate was given at operating room temperature intraoperatively for fluid replacement. Normal saline (N = 32): continuous infusion administered in a micro drip set at a rate of 100 mL/h through a separate dedicated IV line. Ringer's lactate was given at operating room temperature intraoperatively for fluid replacement. |

|

| Outcomes | Nasopharynx temperature and surface temperature every 10 minutes (°C) | |

| Notes | Source of funding was not reported. Conflicts of interest were not reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | States that this is a prospective randomized study |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | States that study was double‐blind |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quotation: 'amino acid and saline solutions were prepared by a person not further involved in the study' |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | States that study was double‐blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not assessed |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns |

Gupta 2009.

| Methods | Single‐centre trial conducted in India | |

| Participants | 60 adults ASA grade I/II (aged 20 to 60 years) scheduled for elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Patients with known hepatic, neuromuscular, thyroid or renal disease; known allergy to study drug; receiving any drug known to affect neuromuscular transmission; and with BMI > 30kg/m² were excluded from the study. Premedication: 2 mcg/kg fentanyl Induction of anaesthesia: 5 mg/kg thiopentone and, depending on allocation, either 0.1 mg/kg vecuronium or 0.5 mg/kg atracurium besylate Maintenance of anaesthesia: 0.8% isoflurane, 66% nitrous oxide in oxygen Mean age: 41.18 years, SD = 3.32 (control + vecuronium); 36.75 years, SD = 9.66 (amino acids + vecuronium); 33.53 years, SD = 12.61 (control + atracurium); 34.27 years, SD = 9.50 (amino acids + atracurium) Male/Female: 3/11 (control + vecuronium); 3/12 (amino acids + vecuronium); 3/12 (control + atracurium); 1/14 (amino acids + atracurium) |

|

| Interventions | Control + vecuronium (n = 15) Amino acids + vecuronium (n = 15) Control + atracurium (n = 15) Amino acids + atracurium (n = 15) All groups received a continuous infusion of amino acid solution or saline solution at the rate of 100 mL/h through a separate dedicated IV line before surgical incision, continued until reversal of the participant from anaesthesia. Ringer's lactate at operating room temperature was given intraoperatively for fluid replacement. |

|

| Outcomes | Nasopharynx temperature | |

| Notes | No useable outcomes, as time points at which data were recorded are unclear Source of funding was not reported. Conflicts of interest were not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quotation: 'prospective, randomised, double blind study' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear if outcome assessors were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not assessed |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns |

Kamitani 2006.

| Methods | Single‐centre prospective randomized trial conducted in Japan | |

| Participants | 74 patients ASA I‐III scheduled for open gastrectomy with combined general and epidural anaesthesia (42 patients with duration of surgery 180 minutes or longer; 32 patients with duration of surgery less than 180 minutes) Premedication: All participants received oral midazolam (3‐5 mg) 30 minutes before entering the operation room (OR) and underwent epidural anaesthesia after entering the OR. Induction of anaesthesia: Anaesthesia was induced with propofol (1‐2 mg/kg) and fentanyl (1‐2 mcg/kg), and all participants were intubated after receiving vecuronium (0.1‐0.15 mg/kg). Maintenance of anaesthesia: Anaesthesia was maintained with oxygen (0.7 L/min), air (2 L/min) and sevoflurane at about 1.5%. Mean age: 63.02 years, SD = 9.7 (amino acids); 65.35 years, SD = 4.68 (electrolytes) Male/Female: 26/10 (amino acids); 30/8 (electrolytes) |

|

| Interventions | Amino acids (n = 36): 200 mL administered for 1 hour from induction of anaesthesia Electrolyte solution (n = 38): 200 mL for 1 hour from induction of anaesthesia All participants received an additional heated mat. |

|

| Outcomes | Tympanic temperature, incidence of hypothermia (core temperature < 35.5°C | |

| Notes | Translated from Japanese | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not assessed |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns |

Kanazawa 2008.

| Methods | Single‐centre trial conducted in Japan | |

| Participants | 20 patients ASA I/II scheduled to undergo surgery for posterior lumbar decompression and fusion under general anaesthesia. Patients with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, diabetes mellitus and hepatic or renal dysfunction were excluded. Premedication: none Induction of anaesthesia: propofol, fentanyl, vecuronium bromide Maintenance of anaesthesia: oxygen, nitrous oxide and sevoflurane with a small dose of fentanyl Mean age: 57.3 years, SD = 10.6 (amino acids + warm fluids); 50.1 years, SD = 17.3 (warm fluids only) Male/Female: 9/1 (amino acids + warm fluids); 7/3 (warm fluids only) |

|