Abstract

Background

Epidural analgesia offers greater pain relief compared to systemic opioid‐based medications, but its effect on morbidity and mortality is unclear. This review was originally published in 2006 and was updated in 2012 and again in 2016.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of postoperative epidural analgesia in comparison with postoperative systemic opioid‐based analgesia for adults undergoing elective abdominal aortic surgery.

Search methods

In the updated review, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and five trial registers in November 2014, together with reference checking to identify additional studies. We reran the search in March 2017. One potential new trial of interest was added to a list of ‘Studies awaiting Classification' and will be incorporated into the formal review findings during the review update.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials comparing postoperative epidural analgesia and postoperative systemic opioid‐based analgesia for adults who underwent elective open abdominal aortic surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information and data when required. We assessed the level of evidence according to the scale provided by the GRADE working group.

Main results

We included 15 trials published from 1987 to 2009 with 1498 participants in this updated review. Participants had a mean age between 60.5 and 71.3 years. The percentage of women in the included studies varied from 0% to 28.1%. Adding an epidural to general anaesthesia for people undergoing abdominal aortic repair reduced myocardial infarction (risk ratio (RR) 0.54 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.30 to 0.97); I2 statistic = 0%; number needed to treat for one additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 28 (95% CI 19 to 1423), visual or verbal analogical scale (VAS) scores up to three days after the surgery (mean difference (MD) ‐1.78 (95% CI ‐2.32 to ‐1.25); I2 statistic = 0% for VAS scores on movement at postoperative day one), time to tracheal extubation (standardized mean difference (SMD) ‐0.42 (95% CI ‐0.70 to ‐0.15); I2 statistic = 83%; equivalent to a mean reduction of 36 hours), postoperative respiratory failure (RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.85); I2 statistic = 0%; NNTB 8 (95% CI 6 to 16)), gastrointestinal bleeding (OR 0.20 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.65); I2 statistic = 0%; NNTB 32 (95% CI 27 to 74)) and time spent in the intensive care unit (SMD ‐0.23 (95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.06); I2 statistic = 0%; equivalent to a mean reduction of six hours). We did not demonstrate a reduction in the mortality rate up to 30 days (RR 1.06 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.86); I2 statistic = 0%). The level of evidence was low for mortality and time before tracheal extubation; moderate for myocardial infarction, respiratory failure and intensive care unit length of stay; and high for gastrointestinal bleeding and VAS scores.

Authors' conclusions

Epidural analgesia provided better pain management, reduced myocardial infarction, time to tracheal extubation, postoperative respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and intensive care unit length of stay compared with systemic opioid‐based drugs. For mortality, we did not find a difference at 30 days.

Keywords: Adult; Aged; Humans; Middle Aged; Analgesia, Epidural; Analgesia, Epidural/adverse effects; Analgesia, Epidural/methods; Analgesics, Opioid; Analgesics, Opioid/adverse effects; Analgesics, Opioid/therapeutic use; Aorta, Abdominal; Aorta, Abdominal/surgery; Cause of Death; Intubation, Intratracheal; Intubation, Intratracheal/statistics & numerical data; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control; Pain Management; Pain Management/methods; Pain Measurement; Pain, Postoperative; Pain, Postoperative/prevention & control; Postoperative Complications; Postoperative Complications/mortality; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Respiration, Artificial; Respiration, Artificial/statistics & numerical data; Time Factors

Plain language summary

Epidural analgesia compared with systemic opioid‐based medicines for people undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery

Background

Open surgery on the abdominal aorta (the main artery to the legs) requires aggressive postoperative pain management. The most commonly used pain management is epidural analgesia. This involves injecting pain‐relieving medicines through a catheter (narrow tube) that is placed in the epidural space (the outermost part of the spinal space). The alternative is systemic opioids (morphine‐like medicines injected into the bloodstream).

Objectives

This review evaluated the effect of these two methods of pain relief and the risks of postoperative complications and deaths after open abdominal aortic surgery. The review was originally published in 2006, updated in 2012, and again in 2015.

Methods

We searched scientific databases for clinical trials comparing epidural analgesia with systemic opioids in adults. Two authors independently assessed the quality of the trials and collected the data. We reran the search in March 2017. We will deal with the new study of interest when we update the review.

Main results

We included 15 trials published from 1987 to 2009 with 1498 participants in this updated review. The evidence is current to November 2014. The trials received financial support from a charitable organization (one study), a governmental organization (four studies) or the pharmaceutical industry (one study). The source of funding was unspecified for nine studies. We found that epidural analgesia reduced heart attacks, postoperative duration of tracheal intubation (a flexible breathing tube that is placed directly into the windpipe), risk of postoperative respiratory failure (requirement of a machine to assist the respiration after the surgery), gastrointestinal bleeding, decreased postoperative pain, and length of stay in the intensive care unit (equivalent to six hours). For death after the surgery, we did not found a difference in the death rate (in hospital or up to 30 days). The quality of evidence was low for mortality and time before tracheal extubation; meaning that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. The quality of evidence was moderate for heart attacks, respiratory failure, and intensive care unit length of stay; meaning that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. The quality of evidence was high for gastrointestinal bleeding and pain scores; meaning that further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Authors' conclusions

Epidural analgesia provides better pain management than systemic opioids. It significantly reduces the number of people who will suffer heart damage, time to return of unassisted respiration, gastrointestinal bleeding, and intensive care unit length of stay. We did not find a difference in death rates at 30 days.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Epidural pain relief compared to systemic opioid‐based pain relief for abdominal aortic surgery.

| Epidural pain relief compared to systemic opioid‐based pain relief for abdominal aortic surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: people undergoing abdominal aortic surgery Settings: Intervention: epidural pain relief Comparison: systemic opioid‐based pain relief | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic opioid‐based pain relief | Epidural pain relief | |||||

| Mortality in hospital or up to 30 days Follow‐up: 30 days1 | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.6 to 1.86) | 1383 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 | ‐ | |

| 39 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (23 to 73) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (12 to 37) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 60 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (36 to 112) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 0.54 (0.30 to 0.97) | 851 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4,6,8,9,10,11 | ‐ | |

| 76 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (23 to 74) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (6 to 19) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 (30 to 97) | |||||

| Tracheal intubation duration Follow‐up: 0‐7 days | ‐ | The mean tracheal intubation duration in the intervention groups was 0.42 lower (0.7 to 0.15 lower) | ‐ | 975 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4,6,8,9,12,13,14 | Data had to be extracted as P values for 2 studies (Norris 2001; Park 2001). Therefore, results are provided as standardized mean difference |

| Respiratory failure | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.56 to 0.85) | 861 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3,4,7,8,9,13,15,16 | ‐ | |

| 315 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 (176 to 267) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (84 to 128) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 350 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (196 to 298) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | OR 0.20 (0.06 to 0.65) | 487 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2,3,4,5,6,8,9,15,17 | ‐ | |

| 40 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (3 to 27) | |||||

| Low | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (1 to 13) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 60 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (4 to 40) | |||||

|

Pain (VAS scores) on movement at postoperative day 1 Scale from: 0 to 10. Follow‐up: mean 1 day |

The mean VAS scores on movement at postoperative day 1 in the intervention groups was 1.78 lower (2.32 to 1.25 lower) | ‐ | 162 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3,4,6,8,9,13,18,19 | ‐ | |

| Intensive care unit length of stay Follow‐up: 0‐7 days | ‐ | The mean intensive care unit length of stay in the intervention groups was 0.23 standard deviations lower (0.41 to 0.06 lower) | ‐ | 523 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4,8,9,13,14,15,16 | Data had to be extracted as P values for 2 studies (Muehling 2009; Park 2001). Therefore, results are provided as standardized mean difference |

| * The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio; VAS: visual/verbal analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 In hospital or up to 30 days. 2 There was uncertainty around allocation concealment for half or more of the studies included in the analysis. 3 I2 statistic < 25%. 4 Direct comparison performed on the population of interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. 5 Wide confidence interval. 6 Correcting the publication bias did not change the conclusion. 7 RR > 0.5. 8 No confounding factor justifying upgrading the evidence identified. 9 No dose‐response gradient. 10 Number of participants included lower than the optimal information size, fewer than 2000 and number of events < 400. 11 RR 0.53. 12 I2 statistic = 85%. Egger's regression intercept indicates that there may be a small‐study effect (P value = 0.003 (2‐tailed)). Excluding two studies with 14 participants each (Barre 1989; Broekema 1998), SMD would be ‐0.42 (95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.22); I2 statistic = 35%. 13 Optimal information size achieved. 14 Standardized mean difference < 0.8. 15 Uncertainty around blinding of the outcome assessor for half or more of the included studies. 16 No evidence of a publication bias. 17 OR 0.20. 18 We identified no serious risk of bias. 19 Standardized mean difference > 0.8.

Background

Description of the condition

Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be defined as a focal dilation of the abdominal aorta of at least 1.5 times the normal diameter or an absolute value of 3.0 cm or greater (Sampson 2014). Known risk factors include age, male sex, atherosclerosis, smoking, hypertension, and history in a first‐degree relative. In 2010, the incidence varied from 7.9 (95% confidence interval (CI) 6.5 to 9.6) in the 40 to 44 years age group to 2274.8 (95% CI 2149.8 to 2410.2) per 100,000 in the 75 to 79 years age group. These numbers represent a small decrease compared to 1990 figures (8.4 (95% CI 7.0 to 10.1) in the 40 to 44 years age group and 2422.5 (95% CI 2298.6 to 2562.3) per 100,000 in the 75 to 79 years age group (Sampson 2014). Prevalence was higher in high‐income versus low‐income nations. The highest prevalence in 1990 was in the high‐income regions of Australasia and North America. Australasia still had the highest prevalence in 2010 with high‐income North American regions coming third with a prevalence of 256.1 (95% CI 238.6 to 275.0) (Sampson 2014). Contemporary one‐time screening of men for abdominal aortic aneurism appears highly cost‐effective, and seems to remain an effective preventive health‐measure (Svensjo 2014). There actually is insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of cardiovascular prophylaxis in reducing mortality and cardiovascular events in people with abdominal aortic aneurisms (Robertson 2014). Traditionally, abdominal aortic aneurisms were treated by open abdominal surgical repair consisting in excision or not of the lesion and interposition of a synthetic graft. Since the early‐1990s, endovascular aneurysm repair has become available. In people considered fit for conventional surgery, endovascular aortic replacement was associated with lower short‐term mortality than open abdominal aortic repair. However, this benefit from endovascular aortic repair did not persist at the intermediate‐ and long‐term follow‐ups. People undergoing endovascular aortic repair had a higher re‐intervention rate than people undergoing open aortic repair (Paravastu 2014).

Description of the intervention

Epidural anaesthesia or analgesia consists of an injection of either local anaesthetic or opioids, or a mixture of both, into the epidural space as a modality to complement general anaesthesia for open abdominal aortic repair (epidural anaesthesia) or to treat postoperative pain (epidural analgesia). Epidural anaesthesia or analgesia is usually achieved through the insertion of an epidural catheter either at the thoracic or lumbar level.

How the intervention might work

Epidural analgesia provides better analgesia than parenteral opioids regardless of the analgesic agent, location of catheter placement, and type and time of pain assessment (Block 2003; Guay 2006). The superior analgesia offers improved postoperative coughing and breathing, and improved pulmonary mechanics thus potentially reducing pulmonary complications (Guay 2014a). The sympathetic blockade provided by epidural anaesthesia and analgesia and the sparing of the total opioid doses required improve bowel motility (Jorgensen 2000). These favourable effects of epidural analgesia may considerably reduce non‐life‐threatening morbidity and may have an important role in a multimodal approach to achieve prompt and expeditious recovery after surgery.

Why it is important to do this review

The original review was conducted because of a lack of consensus regarding the value of epidural anaesthesia and analgesia for this patient population (Nishimori 2006). People undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery typically have vasculopathy, often with a history of diabetes or smoking. They may well be either benefited or harmed by epidural analgesia (Hebl 2006). The most recent version of this review concluded that epidural analgesia provided better pain relief (especially during movement) in the period up to three postoperative days, and reduced the duration of postoperative tracheal intubation, the occurrence of prolonged postoperative mechanical ventilation, myocardial infarction, gastric complications and renal complications (Nishimori 2012).

In the present version of the review, we looked for new studies and updated the methodology.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of postoperative epidural analgesia in comparison with postoperative systemic opioid‐based analgesia for adults undergoing elective abdominal aortic surgery.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing postoperative epidural analgesia and postoperative systemic opioid‐based analgesia for abdominal aortic surgery and assessing at least one of the outcomes of interest (see Types of outcome measures). We excluded from the analysis studies that did not include any outcome of interest.

We excluded all quasi‐randomized trials including one quasi‐randomized trial that was included in the previous version of this review (Lombardo 2009).

We applied no language or publication status restrictions.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years and older) who had elective, open abdominal aortic surgery, either suprarenal or infrarenal. We excluded people who had emergency surgery.

Types of interventions

We included intraoperative or postoperative (or both) epidural anaesthesia or analgesia added to general anaesthesia (either lumbar or thoracic) compared to general anaesthesia alone. We included all combinations of drugs and all start times (pre‐ or postoperatively). We imposed no restriction regarding the mode of analgesia used in the control group and included systemic opioid‐based pain relief with opioid drugs given by the following routes: intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous. For both groups, bolus dosing, infusion, or patient‐controlled analgesia (PCA) devices were eligible for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death from all causes within 30 days of surgery, or death from all causes during hospitalization.

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative cardiovascular complications: myocardial ischaemia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure (CHF), ventricular arrhythmias.

Postoperative respiratory complications: tracheal intubation duration, respiratory failure including prolonged mechanical ventilation or need to reinstate mechanical ventilation, pneumonia.

Postoperative cerebrovascular complications.

Postoperative acute kidney injury.

Postoperative gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Postoperative pain scores (at rest or with movement).

Any indicator for postoperative bowel motility: incidence of ileus, time to first bowel sounds, flatus, bowel movement, or time to first drinking or eating.

Any indicator for postoperative mobilization: any type of functionality score or time to first ambulation.

Length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

Length of hospital stay.

We did not pre‐define these outcomes but noted the definitions used by contributing investigators.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 11) via Ovid; Ovid MEDLINE (from inception to week 1, November 2014); and EMBASE (from inception to week 1, November 2014). We limited the search to human studies with no language or date restrictions. For this update, the search was restricted from 2012 to November 2014 (up to 2012 was covered by the previous versions of this review (Nishimori 2006; Nishimori 2012) (Appendix 1). We retrieved full articles of any potential new study. We also checked the references lists of all retained studies. We reran the search in March 2017. We will deal with the one potential new study of interest when we update the review.

Searching other resources

We looked at www.clinicaltrials.gov; isrctn.org; www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm; www.trialregister.nl/ and eudract.ema.europa.eu/ for trials in progress (December 2014). We also screened conference proceedings of anaesthesiology societies, published in three major anaesthesiology journals, for 2012, 2013, and 2014: British Journal of Anaesthesiology, European Journal of Anaesthesiology and Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. We also checked the website of the American Society of Anesthesiologists for 2012, 2013, and 2014 in December 2014 (www.asaabstracts.com/). We did not contact individuals or organizations.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We were not blinded to study authors, institutions, journal of publication, or study results. For this update, the two authors independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of trials identified in the literature search for their eligibility. We resolved disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We recorded information on participants, methods, interventions, and outcomes. We noted the level of epidural catheter placement and the names and doses of the drugs administered, and whether participants had received epidural medication during the surgery. We analysed the data with Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) and Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2.2.044 (www.Meta‐Analysis.com; effect size for data extracted as P value, Egger's regression intercept, Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis, meta‐regressions, heterogeneity between subgrouping for some analysis not included in this file).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated trial quality using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed risk of bias for the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. We did not use blinding of participants and personnel as a risk of bias domain since it may be considered unethical to use sham epidurals. Instead, we evaluated if care programmes were identical for the intervention and control groups.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported results as risk ratio (RR) and their 95% CI for dichotomous data and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous data as much as was feasible. If some of the continuous data were given on different scales or if results were not available as mean and standard deviation (SD) or events and total number of participants (P value extraction), we produced the results as standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. For SMD, we considered 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Pace 2011). For clinical correspondence, we multiplied the SD of the control group of a study at low risk of bias by the SMD. When there was an effect, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) from the odds ratio (OR). We gave results for dichotomous data as RR because OR is not easily understood by clinicians (Deeks 2002; McColl 1998), but used OR for calculation of NNTB and NNTH (www.nntonline.net/visualrx/) (Cates 2002; Deeks 2002). When there was no effect, we calculated the optimal information size in order to make sure that there were enough participants included in the retained studies to justify a conclusion on the absence of effect (Pogue 1998) (www.stat.ubc.ca/˜rollin/stats/ssize/b2.html). We considered a difference of 1% for the mortality rate and 25% (increase or decrease) for the other outcomes as the minimal clinically relevant difference.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was a participant who was individually randomized to the treatment group (intervention or control) of the RCTs selected for this review.

Three trials had more than two treatment groups (Broekema 1998; Norris 2001; Reinhart 1989). Broekema 1998 allocated participants to three groups: epidural‐sufentanil group, epidural‐morphine group, and intramuscular morphine (IM) group. Both the epidural‐sufentanil and epidural‐morphine groups received postoperative epidural analgesia; and the IM group received IM for postoperative analgesia. The only difference between the epidural‐sufentanil group and the epidural‐morphine group was the type of opioid they received epidurally (sufentanil or morphine). Otherwise they were similar. We were able to combine these two groups because the author provided raw data.

In Reinhart 1989, participants were allocated into three groups: thoracic epidural anaesthesia group; neurolept anaesthesia group; and halothane group. The thoracic epidural anaesthesia group received postoperative epidural analgesia. The neurolept anaesthesia and halothane groups received postoperative systemic opioid (piritramide analgesia). However, during surgery these two groups received different types of general anaesthesia. The neurolept anaesthesia group received neurolept anaesthesia with fentanyl and droperidol, and the halothane group received halothane with nitrous oxide and oxygen. Data were entered as subgroups, dividing the intervention group (thoracic epidural anaesthesia) by two, allowing us to analyse the data as subgroups or combining them.

In Norris 2001, participants were allocated into four possible combinations of anaesthesia: general anaesthesia (GA) followed by IV morphine patient‐controlled analgesia (IVPCA) (GA‐IVPCA), general anaesthesia followed by epidural patient‐controlled analgesia (EPCA) (GA‐EPCA), general anaesthesia combined with epidural anaesthesia (RSGA) followed by IVPCA (RSGA‐IVPCA) and RSGA followed by EPCA (RSGA‐EPCA). We divided the data from GA‐IVPCA by three to allow us to analyse the data as subgroups compared to the three regimens that included an epidural (GA‐EPCA, RSGA‐IVPCA, and RSGA‐EPCA) or combining them.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the trial investigators for the data that were missing or unclear. In studies where the surgical population included participants who were not undergoing abdominal aortic surgery, we only included data on the people undergoing abdominal aortic surgery. If separated data were not published, we contacted trial investigators and requested the separated data. If separated data were not available, or were indistinguishable from the group data, we excluded that study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity through careful evaluation of populations, interventions, and outcomes within each study. We used the I2 statistic to estimate the extent of the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias with the Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses if sufficient data existed from two or more studies. We used random‐effects models for outcomes with I2 statistic greater than 25% and fixed‐effect models for other outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Any amount of heterogeneity was explored but we focused more specifically on comparisons with a moderate or high amount of heterogeneity (I2 statistic greater than 25%) (Higgins 2003), and explored the heterogeneity using Egger's regression intercept (to assess the possibility of a small‐study effect (Rucker 2011), visual inspection of the forest plots with studies placed in order according to a specific moderator, subgroupings (categorical moderators), or meta‐regressions (continuous moderators)). Factors that were considered in the heterogeneity exploration were: year when the study was published, mean age of participants, site of epidural (thoracic versus lumbar), local anaesthetic in the epidural solution or opioids only, duration of epidural use, percentage of women included, and percentage of participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or with CHF.

Sensitivity analysis

We also performed sensitivity analysis in our heterogeneity exploration based on the number of participants included or on the risk of bias assessments (allocation concealment and blinding of the outcome assessor).

Summary of findings

The quality of the body of evidence was judged according to the system developed by the GRADE working group (Guyatt 2011a) and presented in a 'Summary of findings' table (ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro) for the following outcomes: mortality in hospital or up to 30 days, myocardial infarction, tracheal intubation duration, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, visual or verbal analogue scale (VAS) score on movement at postoperative day one and ICU length of stay. For risk of bias, we judged the quality of evidence as low risk of bias when most information came from studies at low risk of bias, and downgraded it by one level when most information came from studies at low or unclear risk of bias or by two levels when the proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias was sufficient to affect the interpretation of results. For inconsistency, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when the I2 statistic was 50% or higher without satisfactory explanation and by two levels when the I2 statistic was 75% or higher without an explanation. We did not downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness as all outcomes were based on direct comparisons, were performed on the population at interest, and were not surrogate markers (Guyatt 2011b). For imprecision (Guyatt 2011c), we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when the CI around the effect size was large or overlapped an absence of effect and failed to exclude an important benefit or harm; the number of participants was lower than the optimal information size (unless the sample size was at least of 2000 participants or the number of events included was at least 400); and we downgraded the quality by two levels when the CI was very wide and included both appreciable benefit and harm. For publication bias, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one when correcting for the possibility of publication as assessed by the Duval and Tweedie's fill and trim analysis changed the conclusion. We upgraded the quality of evidence by one when the effect size was large (less than 0.5 or greater than 2.0) and by two when the effect size was very large (RR less than 0.2 or greater than 5) (Guyatt 2011d). We applied the same rules for OR when the basal risk was lower than 20%. For SMD, we used 0.8 as the cutoff point for a large effect (Pace 2011). We also upgraded the quality by one when there was evidence of a dose‐related response. The quality was upgraded by one when possible effect of confounding factors would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect. When the quality of the body of evidence is high, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. When the quality is moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. When the quality is low, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. When the quality is very low, any estimate of effect is very uncertain (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

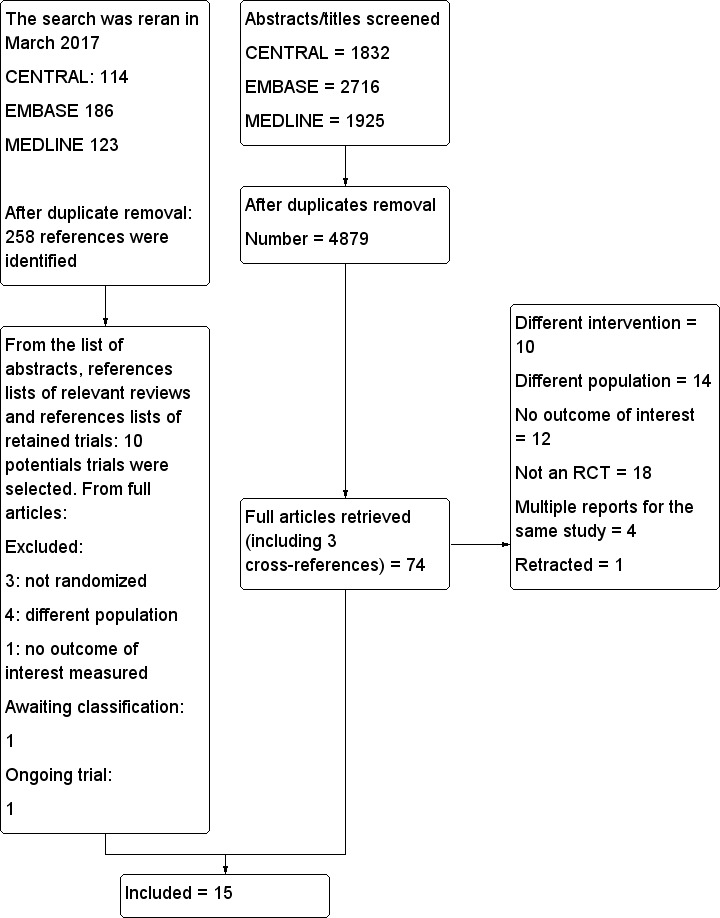

Figure 1 shows the results of the search for the current update. We reran the search in March 2017. Two‐hundreds and 58 citations were found. From these new citation, and the reference lists of relevant reviews and of the potential new trials, 10 full articles were retrieved. Of these, eight were excluded, one trial is ongoing and one trial was added to the of ‘Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' and will be incorporated into the formal review findings during the review update.

1.

Flow diagram of study selection. We excluded one trial (Lombardo 2009; quasi‐randomized trial; information obtained from the authors by the previous review authors), which was previously included in this review (Nishimori 2012). We added one new trial (Muehling 2009). Therefore, the number of studies included in this review remains unchanged.

The search was reran in March 2017. Seven trials were excluded, one trial (Owczuk 2016) awaits classification and one trial (Li 2015) is ongoing.

RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Included studies

We included 15 trials published from 1987 to 2009 with 1498 participants. Participants had a mean age between 60.5 and 71.3 years. The percentage of women in the included studies varied from 0% to 28.1%. In three included trials, people undergoing aortic surgery were mixed with people undergoing other surgical procedures (Broekema 1998; Park 2001; Yeager 1987). We contacted the authors of all these trials. The authors of Park 2001 published subgroup data on abdominal aortic surgery and also provided the additional data requested for our review. The authors of Broekema 1998 and Yeager 1987 provided additional unpublished data on the aortic abdominal surgery subgroups.

Surgery included both aortic aneurysm repair and surgery for aortic occlusive disease in 10 studies (Barre 1989; Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Garnett 1996; Kataja 1991; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989; Yeager 1987). Norman 1997 and Muehling 2009 included only repairs of infrarenal aortic aneurysm. de Lis 1990 included only aortic occlusive disease. Two studies did not specify whether the surgical procedure was for aortic aneurysm or occlusive disease (Broekema 1998; Davies 1993). For aortic aneurysm location, only four studies specified supra‐ or infrarenal (Barre 1989; Boylan 1998; Muehling 2009; Norman 1997). Therefore, it was not possible to perform subgroup analysis on either suprarenal versus infrarenal aortic surgery or surgery for aneurysm versus occlusive disease. Appendix 2 provides information about preoperative risks, history of myocardial revascularization, and preoperative medication of participants of the included trials.

Appendix 3 provides the methods of surgical anaesthesia and postoperative analgesia of the included trials. Three trials had more than two treatment groups (Broekema 1998; Norris 2001; Reinhart 1989). The details and how we handled the groups are explained in the Unit of analysis issues section. All other trials had two treatment groups, one group received postoperative epidural analgesia (intervention group) and the other group received postoperative systemic opioid analgesia (control group). People who received postoperative epidural analgesia also received epidural anaesthesia during surgery except for: group II of de Lis 1990, the thoracic epidural anaesthesia (TEA) group of Bois 1997, the GA‐EPCA group of Norris 2001, where epidural infusion was started at the end of surgery. Participants who received postoperative systemic opioid analgesia did not receive epidural anaesthesia during surgery except for the RSGA‐IVPCA group of Norris 2001, where an epidural was used only during the surgery and participants received systemic opioid analgesia postoperatively. All participants received general anaesthesia during surgery. Anaesthetic agents were similar between the control and intervention groups in each study. Inhalational anaesthetics were the main anaesthetics for most of the trials, except for Reinhart 1989 (fentanyl and droperidol for half of the control group) and Yeager 1987 (fentanyl/nitrous oxide in the intervention group versus fentanyl with or without nitrous oxide and with or without inhalational agent in the control group). de Lis 1990 and Muehling 2009 did not specify the anaesthetic agents used.

Eight trials used thoracic epidural analgesia (Barre 1989; Bois 1997; Broekema 1998; Davies 1993; Muehling 2009; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Reinhart 1989), and two trials used lumbar epidural analgesia (Boylan 1998; Kataja 1991). Four trials used either thoracic or lumbar epidurals (Garnett 1996; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). One study did not mention the level of epidural catheter placement (de Lis 1990). Appendix 3 shows the exact solution used in the epidural catheters. For the surgery, nine trials used a local anaesthetic alone: lidocaine (Davies 1993), bupivacaine (Kataja 1991; Norman 1997; Park 2001; Reinhart 1989), ropivacaine (Muehling 2009), lidocaine plus bupivacaine (Barre 1989), lidocaine or bupivacaine (Yeager 1987), and bupivacaine or ropivacaine (Peyton 2003). Four trials used a mixture of local anaesthetics and opioids: bupivacaine plus fentanyl (Norris 2001), lidocaine plus pethidine (Garnett 1996), bupivacaine plus sufentanil or morphine (Broekema 1998), and lidocaine plus bupivacaine plus morphine (Boylan 1998). For postoperative analgesia, eight trials used a mixture of local anaesthetics and opioids: bupivacaine plus fentanyl (Bois 1997; Kataja 1991; Norris 2001), bupivacaine plus morphine (Boylan 1998), bupivacaine plus morphine or sufentanil (Broekema 1998), bupivacaine plus pethidine (Garnett 1996), ropivacaine plus sufentanil (Muehling 2009), and bupivacaine or ropivacaine plus fentanyl or pethidine (Peyton 2003). Two trials used local anaesthetics alone: bupivacaine (Davies 1993; Reinhart 1989). Three trials used opioids alone: morphine (de Lis 1990; Norman 1997; Park 2001). In two trials, the information was unclear (Barre 1989; Yeager 1987).

Appendix 4 summarizes the definitions of postoperative complications. Basically, the outcomes were well defined and were similar among trials.

Excluded studies

From the search for this update and from the study awaiting classification, we excluded seven trials. Two trials were not randomized (Lombardo 2009; Tatsuishi 2012). Two trials compared epidural analgesia to local infiltration (Renghi 2013; Tilleul 2012). One trial did not contain any outcome of interest to this review (Panaretou 2012). One trial studied a different population (no open abdominal aortic surgery included) (Pan 2006). For the last trial, the population studied was participants undergoing lower abdominal surgery. We contacted the authors and did not receive a reply. The reasons for exclusion of the trials can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and in Figure 1. We also changed the reason of exclusion of one article (Piper 2000): this article has now been retracted.

Studies awaiting classification

We reran the search in March 2017. One trial (Owczuk 2016) is awaiting classification. For further details see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We reran the search in March 2017. One trial (Li 2015) is ongoing. For further details see Characteristics of ongoing studies

Risk of bias in included studies

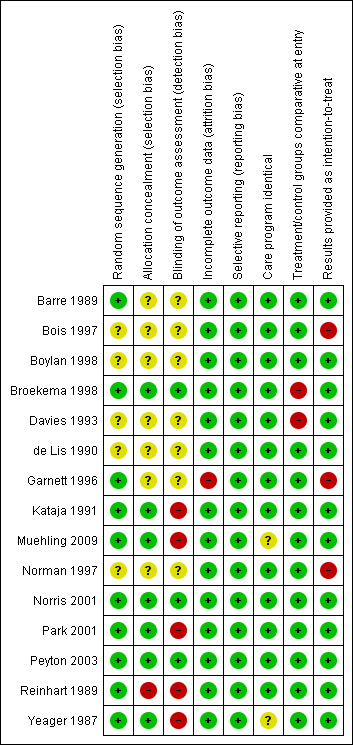

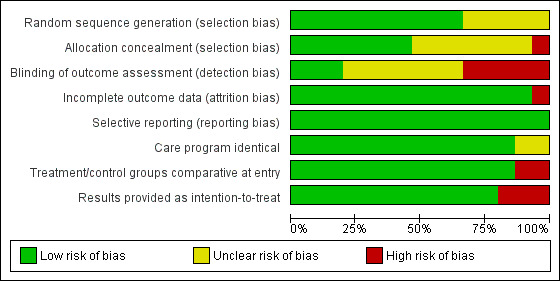

Figure 2 shows a 'Risk of bias' graph and Figure 3 shows a 'Risk of bias' summary.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Seven trials used adequate concealment of allocation (Broekema 1998; Kataja 1991; Muehling 2009; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). Reinhart 1989 did not use allocation concealment. The information was unclear for the remaining seven trials.

Blinding

Three trials blinded outcome assessors. In Norris 2001, all participants had an epidural catheter inserted before surgery and received both masked epidural and intravenous medications in order to blind study participants, anaesthesiologists and outcome assessors. Although the data collectors were not blinded in Peyton 2003, they were not informed about the morbidity endpoints or their definitions. Blinded trial assistants entered the collected data, and a computer algorithm defined whether particular endpoints had occurred at the time of the data entry. Broekema 1998 placed a sham epidural catheter on the skin of the back of participants allocated to control group. The participants were asked not to disclose the route of administration to the observer. If disclosure accidentally occurred, then the observer was replaced. Five trials did not blind outcome assessors (Kataja 1991; Muehling 2009; Park 2001; Reinhart 1989; Yeager 1987), and for seven other studies, the information was unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged only one trial at high risk for attrition bias (Garnett 1996).

Selective reporting

We judged all trials at low risk for reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In Davies 1993, there were significantly more participants with chronic airway disease in the intervention (epidural) group. In Park 2001, there were significantly more smokers in the intervention group. In Broekema 1998, subgroup data for people undergoing aortic surgery that were provided by the author showed that the mean age of the intervention group (72.9 years) was higher than the mean age of the control group (58.0 years). Other baseline data for these three trials and all baseline data for other trials were comparable.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcome

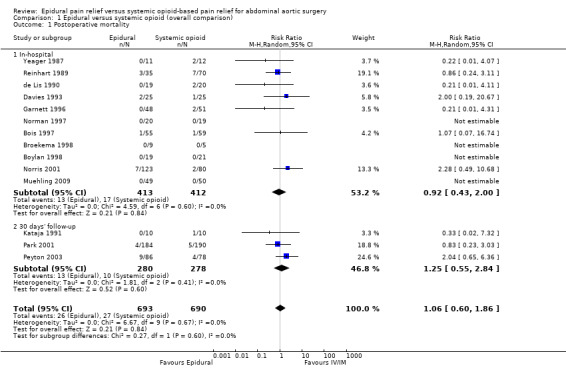

Death from all causes within 30 days of surgery, or death from all causes during hospitalization

Based on 14 trials that included 1383 participants, we did not find a difference in in‐hospital mortality rate (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Davies 1993; de Lis 1990; Garnett 1996; Muehling 2009; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Reinhart 1989; Yeager 1987), or 30‐day mortality rate (Kataja 1991; Park 2001; Peyton 2003) (RR 1.06 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.86); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.1). Egger's regression intercept showed a small‐study effect (P value 0.03; two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that three studies might be missing to the right, but the adjusted point of estimate would nevertheless remain not statistically significant if this possible publication bias was corrected. Based on a basal rate of 4.0%, 8352 participants (4176 per group) would have been required to eliminate a difference of 25%, that is, decrease the mortality rate to 3% (alpha 0.05, beta 0.2; one‐sided test; www.stat.ubc.ca/˜rollin/stats/ssize/b2.html). The level of evidence for this outcome was low (Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 1 Postoperative mortality.

One trial gave results for mortality at one year (RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.90)) (Norris 2001).

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative cardiovascular complications

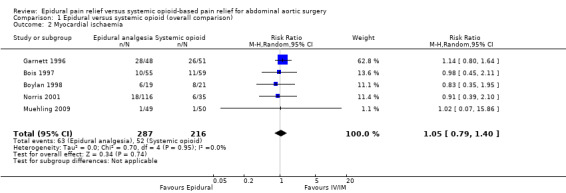

Myocardial ischaemia

Based on five trials that included 503 participants, we did not find a difference in the incidence of myocardial ischaemia (RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.40); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.2). Four trials used continuous monitoring (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001), one trial performed laboratory investigations on clinical indication only (Muehling 2009). Including or excluding this study did not change the results (Muehling 2009). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that three studies might be missing to the right for an adjusted point of estimate of 1.14 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.46).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 2 Myocardial ischaemia.

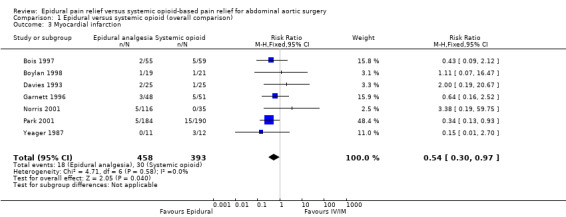

Myocardial infarction

Based on seven trials that included 851 participants, the effect of the intervention was at the limit for statistical significance (RR 0.54 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.97); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.3) (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Yeager 1987). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two studies might be missing to left of mean for an adjusted point of estimate RR 0.43 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.84 (random‐effects model)). Based on a basal rate of 7.6%, the NNTB was 28 (95% CI 19 to 1423). The optimal information size for a 25% reduction from a basal rate of 7.6% would be 4252 (2126 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test). The level of evidence for this outcome was moderate (Table 1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 3 Myocardial infarction.

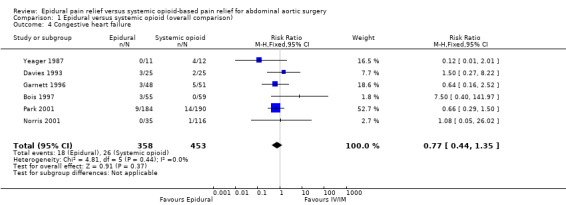

Congestive heart failure

Based on six trials that included 811 participants, we did not find a difference in CHF (RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.35): I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.4) (Bois 1997; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Yeager 1987). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to left of mean, but the adjusted point of estimate would nevertheless remain not statistically significant.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 4 Congestive heart failure.

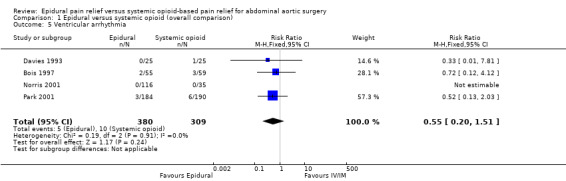

Ventricular arrhythmias

Based on four trials that included 689 participants, we did not find a difference in the risk of ventricular arrhythmia (RR 0.55 (95% CI 0.20 to 1.51); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.5) (Bois 1997; Davies 1993; Norris 2001; Park 2001). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to right of mean, but the adjusted point of estimate would nevertheless remain not statistically significant. Based on a basal rate of 3.2%, 8164 participants (4082 per group) would have been required to eliminate a 25% decrease in the incidence of ventricular arrhythmia.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 5 Ventricular arrhythmia.

Postoperative respiratory complications

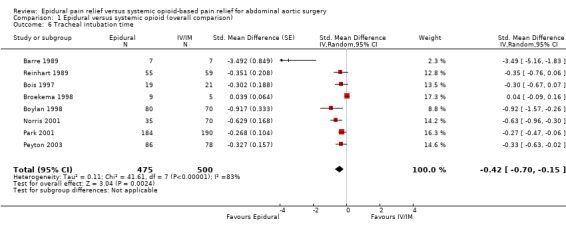

Tracheal intubation duration

Based on eight trials that included 975 participants (Appendix 5), adding an epidural to general anaesthesia reduced time to tracheal extubation (SMD ‐0.42 (95% CI ‐0.70 to ‐0.15); I2 statistic = 83%) (Barre 1989; Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989). Egger's regression intercept indicated that there may be a small‐study effect (P value = 0.001 (two‐tailed)). Excluding two studies with 14 participants (Barre 1989; Broekema 1998), the SMD would be ‐0.39 (95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.24; I2 statistic 20%; Analysis 1.6). Still excluding the two small studies, Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to the right for an adjusted point of estimate (SMD ‐0.41 (95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.20); random‐effects model). Based on the SD measured in the control group of the trial with the lowest risk of bias (Barre 1989; SD 85) and where the SD was available for this outcome (Barre 1989; Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989), the mean reduction would be equivalent to 36 hours. Based on a study with a mean value and SD (Bois 1997), the optimal information size for a 25% reduction from a mean time of 12.9 and an SD of 7.7 hours would be 142 participants (71 per group). The level of evidence for this outcome was low (Table 1).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 6 Tracheal intubation time.

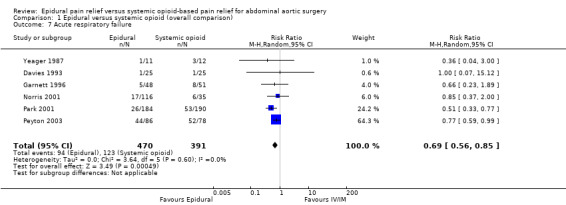

Respiratory failure including prolonged mechanical ventilation or need to reinstate mechanical ventilation

Six trials that included 861 participants reported acute respiratory failure (Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). They all defined the outcome as prolonged ventilation after surgery (Appendix 4). The event rate was significantly smaller in the intervention group compared to the control group (RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.85); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.7). Based on a basal rate of 31.5%, the NNTB was 8 (95% CI 6 to 16). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of a publication bias. The level of evidence for this outcome was high (Table 1). Based on basal rate of 31.5%, the optimal information size for a reduction of 25% was 790 participants (395 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test). The level of evidence for this outcome was moderate.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 7 Acute respiratory failure.

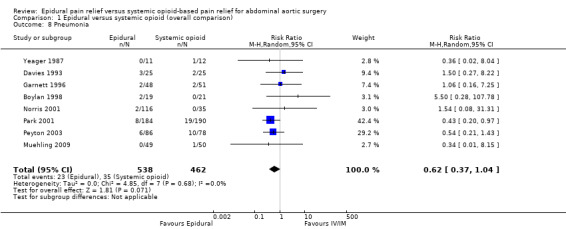

Pneumonia

Based on eight trials that included 1000 participants, we did not find a reduction in the incidence of postoperative pneumonia (RR 0.62 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.04); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.8) (Boylan 1998; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Muehling 2009; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two studies might be missing to left of mean for an adjusted point of estimate RR 0.51 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.83). Assuming that a publication bias was present and a basal rate of 7.5%, the NNTB would be 27 (95% CI 19 to 79).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 8 Pneumonia.

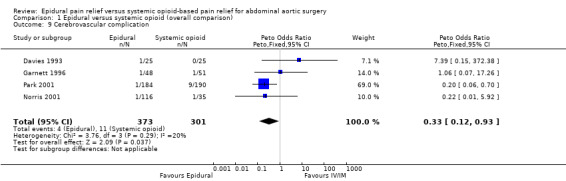

Postoperative cerebrovascular complications

Four trials reported postoperative cerebrovascular complications (Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001; Park 2001). In total, the trials reported 15 cases of cerebrovascular complications (four in intervention group and 11 in control group) in 674 participants. Using Peto OR (rare events), epidural analgesia reduced the risk of stroke (OR 0.33 (95% CI 0.12, 0.93); I2 statistic = 20%; Analysis 1.9). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two studies might be missing to left of mean for an adjusted point of estimate OR 0.21 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.54; fixed‐effect model). Assuming a basal rate of 3.7%, the NNTB would be 41 (95% CI 31 to 400).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 9 Cerebrovascular complication.

Postoperative acute kidney injury

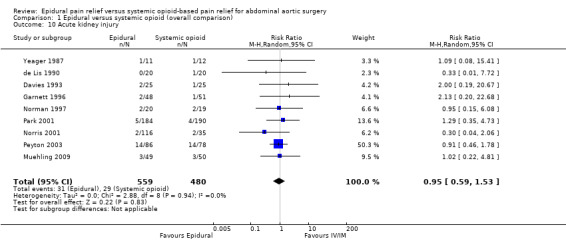

Based on nine trials that included 1039 participants we did not find a difference in the incidence of acute kidney injury (RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.53); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.10) (Davies 1993; de Lis 1990; Garnett 1996; Muehling 2009; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that one study might be missing to left of mean, but the adjusted point of estimate would nevertheless remain not statistically significant.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 10 Acute kidney injury.

Postoperative gastrointestinal haemorrhage

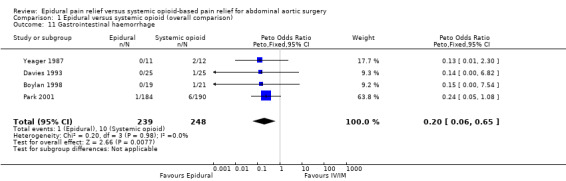

Based on four trials that included 487 participants, and using Peto OR (rare events) adding an epidural to general anaesthesia decreased the risk of postoperative gastrointestinal bleeding (OR 0.20 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.65); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.11) (Boylan 1998; Davies 1993; Park 2001; Yeager 1987). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two studies might be missing to right of mean for an adjusted point of estimate OR 0.23 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.66). Based on a basal rate of 4%, the NNTB was 32 (95% CI 27 to 74). The level of evidence for this outcome was high (Table 1).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 11 Gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Postoperative pain scores (at rest or with movement)

See Appendix 6.

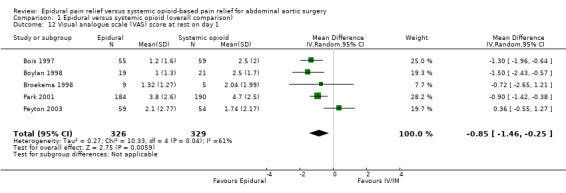

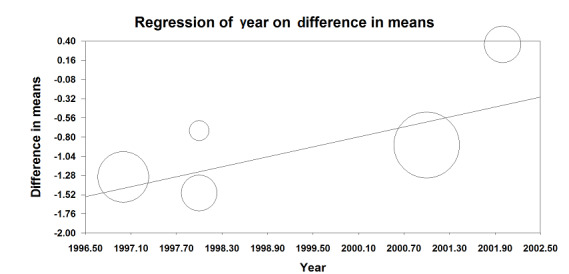

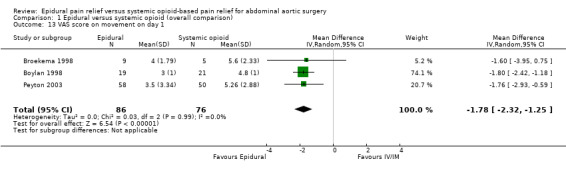

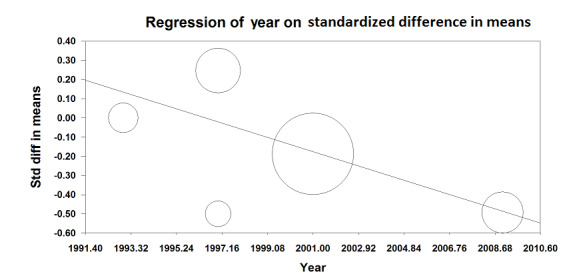

VAS scores were available at rest on postoperative day one for five trials that included 655 participants (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Park 2001; Peyton 2003). Using an epidural for postoperative analgesia produced a slight decrease in VAS scores at rest on postoperative day one (MD ‐0.85 (95% CI ‐1.46 to ‐0.25); I2 statistic = 61%; Analysis 1.12). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of a publication bias. The effect of the intervention may have decreased with time as shown by a meta‐regression of the MD versus the year when the study was published (Figure 4) (P value = 0.02). However, the effect of the intervention was more consistent on movement as reported in three trials that included 162 participants (MD ‐1.78 (95% CI ‐2.32 to ‐1.25); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.13) (Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Peyton 2003). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed that two studies might be missing to left of mean for an adjusted point of estimate MD ‐1.78 (95% CI ‐2.26 to ‐1.31). Based on Peyton's value (Peyton 2003), the optimal information size for a decrease of 1.5 from a mean of 5.26 and an SD of 2.88 was 92 participants (46 per group) (alpha 0.05; beta 0.2; one‐sided test). The level of evidence for a reduction of pain on movement at postoperative day one was high (Table 1).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 12 Visual analogue scale (VAS) score at rest on day 1.

4.

Visual/verbal analogical scores at rest on postoperative day 1. The difference between the intervention is higher in older studies (P value = 0.02).

(This meta regression plot was not produced in RevMan. The figure was generated automatically by the software, and cannot be amended. The software has expressed the years as decimals.)

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 13 VAS score on movement on day 1.

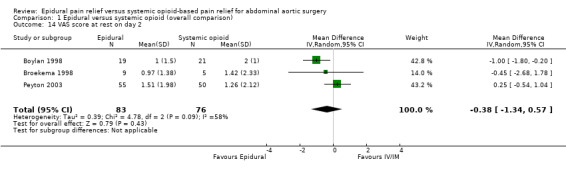

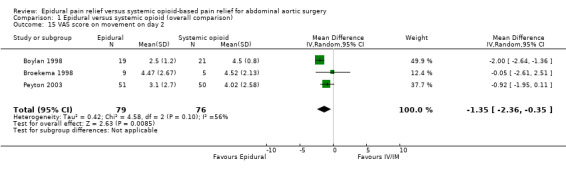

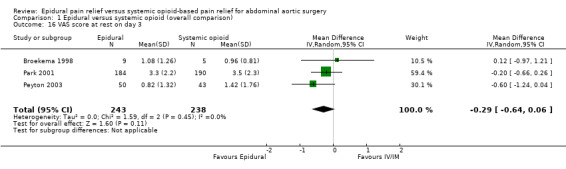

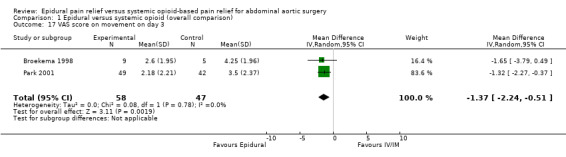

VAS scores at rest on postoperative day two were available for three studies with 159 participants (Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Peyton 2003). There was a considerable difference in the effect size between the three studies (MD ‐0.38 (95% CI ‐1.34 to 0.57); I2 statistic 58% (Analysis 1.14). Based on the same studies with 155 participants, VAS scores on movement on postoperative day two were lower for people treated with epidural analgesia (MD ‐1.35 (95% CI ‐2.36 to ‐0.35); I2 statistic = 56%; Analysis 1.15) (Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Peyton 2003). However, the amplitude of the effect was lower in the more recent and larger study (Peyton 2003). Based on three trials that included 481 participants, we found no difference in VAS scores at rest on postoperative day three (MD ‐0.29 (95% CI ‐0.64 to 0.06); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.16). The authors of two studies provided data for VAS scores on movement on 105 participants on postoperative day three (MD ‐1.37 (95% CI ‐2.24 to ‐0.51); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.17) (Broekema 1998; Peyton 2003).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 14 VAS score at rest on day 2.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 15 VAS score on movement on day 2.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 16 VAS score at rest on day 3.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 17 VAS score on movement on day 3.

Any indicator for postoperative bowel motility: incidence of ileus, time to first bowel sounds, flatus, bowel movement, or time to first drinking or eating

Norris 2001 reported time to postoperative landmarks for feeding and ambulation. They were: first bowel sounds, first flatus, first bowel movements, tolerating clear liquids, tolerating regular diet, and independent ambulation. One author reported on the risk of an ileus after the surgery (Muehling 2009). No significant differences were found among treatment groups.

Any indicator for postoperative mobilization: any type of functionality score or time to first ambulation

Park 2001 reported function scale (0 = unable to perform any tasks to 6 = walk without assistance) on postoperative days one, three, and seven. No significant differences were found among treatment groups.

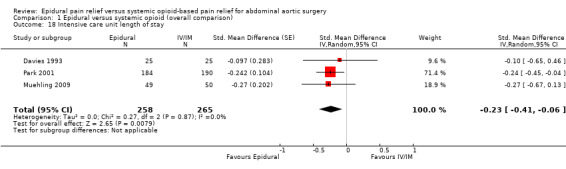

Length of intensive care unit stay

Based on three trials that included 523 participants, epidural analgesia reduced the ICU length of stay (SMD ‐0.23 (95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.06); I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 1.18) (Davies 1993; Muehling 2009; Park 2001). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of a publication bias. Based on the sole study where mean and SD were available (Davies 1993), the optimal size information for a 25% reduction in the time spent in the ICU would be 522 participants (261 per group) (alpha 0.05, beta 0.2; one‐sided test). The level of evidence for this outcome was moderate (Table 1).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 18 Intensive care unit length of stay.

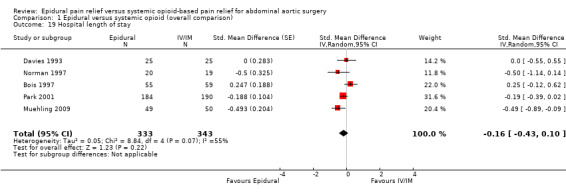

Length of hospital stay

Based on five trials that included 676 participants, we did not find a difference in hospital length of stay (SMD ‐0.16 (95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.10); I2 statistic = 55%; Analysis 1.19) (Bois 1997; Davies 1993; Muehling 2009; Norman 1997; Park 2001). Egger's regression intercept showed no evidence of a small‐study effect (two‐tailed). Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis showed no evidence of a publication bias. However, it is possible that effect would be seen only in the more recent trials (Figure 5).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 19 Hospital length of stay.

5.

Meta‐regression on the hospital length of stay versus the year where the study was published. The effect seems to be better in the more recent study (P value = 0.04).

Std diff in means: standardized mean difference.

(This meta regression plot was not produced in RevMan. The figure was generated automatically by the software, and cannot be amended. The software has expressed the years as decimals.)

Discussion

Adding an epidural to general anaesthesia does not change the mortality rate at 30 days for people undergoing open abdominal aortic repair (level of evidence low). This is consistent with the results of our overview (Guay 2014a), and with the previous version of this review (Nishimori 2012). However, adding an epidural reduced the rate of myocardial infarction (NNTB 28 (95% CI 19 to 1423); level of evidence moderate). For other interventions (e.g. systematic perioperative administration of beta‐blocking agents or statins), where the intervention reduced myocardial infarction at 30 days, the mortality rate reduction was seen only after a longer period (up to one year) (Guay 2013; Guay 2014b). Here data at one year were very limited. Only one trial gave results for mortality at one year (RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.90)) and the number of participants included in this trial was clearly insufficient to allow us to draw any valid conclusion (Norris 2001). Therefore, studies with a longer follow‐up and a sufficient number of participants are required before a firm conclusion on the effects of adding an epidural to general anaesthesia of people undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery can be drawn.

Adding an epidural to general anaesthesia reduced the time to tracheal extubation (level of evidence low) and postoperative respiratory failure (level of evidence moderate). Therefore it follows that adding an epidural reduced the time spent in the ICU (level of evidence moderate).

We also found a reduction in postoperative gastrointestinal bleeding (level of evidence high). This is consistent with one study showing that people receiving epidural anaesthesia during abdominal aortic reconstruction appeared to have less severe disturbances of sigmoid perfusion compared with people not receiving epidural anaesthesia (Panaretou 2012).

As already clearly demonstrated, epidural analgesia decreased postoperative pain scores and this was particularly evident on pain score on movement. The level of evidence for pain reduction on movement at postoperative day one was high quality.

Summary of main results

Adding an epidural to general anaesthesia for people undergoing abdominal aortic repair reduces VAS scores, time to tracheal extubation, myocardial infarction, postoperative respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and time spent in the ICU. We did not find a reduction of mortality (in‐hospital or up to 30 days). The level of evidence was low for mortality and time before tracheal extubation; moderate for myocardial infarction, respiratory failure, and ICU length of stay; and high for gastrointestinal bleeding and VAS scores.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We could not demonstrate a reduction in mortality rate, but the number of participants with an adequate period of follow‐up was clearly insufficient for this outcome. For all other outcomes, we consider that the quality of the studies included in the present review was sufficient to allow us to make conclusions on the effect of adding an epidural to general anaesthesia for people undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery. This is supported by the level of evidence that was rated as moderate quality for a reduction in myocardial infarction, respiratory failure and length of stay in the ICU and high for pain scores and gastrointestinal bleeding . For length of tracheal intubation, there was some inconsistency between the studies and the level of evidence was low. This might be due, in part to a change in practice over the years. Studies included in the present review were published between 1987 and 2009. A change in the clinical practice towards earlier tracheal extubation has clearly taken place during these years.

Quality of the evidence

Table 1 shows the level of evidence.

For mortality, we downgraded the evidence on the basis of risk of bias because seven out of the 14 trials included in the analysis had uncertainty around allocation concealment. There was no inconsistency as measure by a I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population at interest and the outcome is not a surrogate marker. We downgraded the level of evidence for imprecision due to a wide CI. Although the possibility of a publication bias was present for this outcome, we did not downgrade the level of evidence on this item because we calculated that applying a correction for the possibility of a publication bias did not change the results. We did not upgrade the evidence based on a large effect size (RR 0.6), We also did not identify confounding factors justifying upgrading the quality of evidence and did not find a dose‐response relationship. We rated the quality of evidence as low.

For myocardial infarction, we downgraded the evidence on the basis of risk of bias because four out of the seven trials included in the analysis had uncertainty around allocation concealment. There was no inconsistency as measure by a I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population of interest and the outcome is not a surrogate marker. We downgraded the level of evidence for imprecision because the number of participants included was lower than the optimal information size, fewer than 2000 and the number of events was lower than 400. Although the possibility of a publication bias was present for this outcome, we did not downgrade the level of evidence because we calculated that applying a correction for the possibility of a publication bias did not change the results. We upgraded the level of evidence for this outcome on the basis of a large effect size (RR 0.53). We did not identify confounding factor justifying upgrading the quality of evidence and did not find a dose‐response relationship. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate.

For tracheal intubation, we downgraded the evidence on the basis of risk of bias because four out of the seven trials included in the analysis had uncertainty around allocation concealment. We also downgraded the evidence on the basis of a serious inconsistency (unexplained I2 statistic = 35%). Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population at interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. We did not downgrade the level on the basis of imprecision because the optimal information size was achieved. Although the possibility of a publication bias was present for this outcome, we did not downgrade the level of evidence on this item because we calculated that applying a correction for the possibility of a publication bias did not change the results. We did not modify the level of evidence on the basis of the amplitude of the effect size, confounding factors, or dose‐response gradient. We rated the quality of evidence as low.

For respiratory failure, we downgraded the quality of evidence for risk of bias on the basis that there was uncertainty around blinding of the outcome assessor in half or more of the studies. There was no inconsistency as measured by an I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population of interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. We did not downgrade the level on the basis of imprecision because the optimal information size was achieved. There was no evidence of publication bias. We did not modify the level of evidence on the basis of the amplitude of the effect size, confounding factors, or dose response gradient. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate.

For gastrointestinal bleeding, we downgraded the quality of evidence for risk of bias on the basis that there was uncertainty around allocation concealment and blinding of the outcome assessor in half or more of the studies. There was no inconsistency as measured by an I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population of interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. We downgraded the level of evidence on the basis of imprecision on the basis of wide CI (95% CI 0.06 to 0.65). Although the possibility of a publication bias was present for this outcome, we did not downgrade the level of evidence on this item because we calculated that applying a correction for the possibility of a publication bias did not change the results. We upgraded the level of the quality of evidence on the basis of a very large effect size (OR 0.20). We did not modify the level of evidence on the basis of confounding factors, or dose‐response gradient. We rated the quality of evidence as high.

For VAS scores on movement at postoperative day one, we found no serious risk of bias. There was no inconsistency as measured by an I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population of interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. We found no evidence of imprecision. Although the possibility of a publication bias was present for this outcome, we did not downgrade the level of evidence on this item because we calculated that applying a correction for the possibility of a publication bias did not change the conclusion. We upgraded the level of evidence for this outcome on the basis of a large effect size (SMD ‐1.78). We did not modify the level of evidence on the basis of confounding factors or dose‐response gradient. We rated the quality of evidence as high.

For length of stay in the ICU, we downgraded the quality of evidence for risk of bias on the basis of uncertainty for allocation concealment and blinding of the outcome assessor. There was no inconsistency as measured by an I2 statistic of 0%. Indirectness was not a factor: direct comparison performed on the population at interest and the outcome was not a surrogate marker. We found no evidence of imprecision. We found no evidence of a publication bias. We did not modify the level of evidence on the basis of the amplitude of the effect size, confounding factors, or dose‐response gradient. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate.

Potential biases in the review process

We are confident that our search was extensive enough to allow us to include all relevant studies. Additional information provided by some authors also allowed us to include high‐quality unpublished data. Although some of the studies had some item at risk of bias, we think that the quality of included studies is sufficient enough to allow us to draw valid conclusion on our outcomes of interest except for mortality, where studies with a longer period of follow‐up are required, and time to tracheal extubation.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our results on the absence of effect on the mortality rate at 30 days are consistent with the results of our overview (Guay 2014a), and with the latest previous version of this review (Nishimori 2012). However, as mentioned earlier, for other interventions, such as routine perioperative use of beta‐blocking agents (Guay 2013) or statins (Guay 2014b), a reduction in the rate of myocardial infarction such as seen here may translate into a reduction in the mortality rate only after several months. Therefore, without an appropriate time of follow‐up (up to 30 days only), we cannot conclude on the effect of adding epidural analgesia to general anaesthesia for people undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery for mortality.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Compared with systemic opioids, epidural analgesia provided better pain management up to postoperative day three, and reduced time to tracheal extubation, myocardial infarction, postoperative respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding and intensive care unit length of stay. We cannot draw any firm on the effect of adding epidural analgesia to general anaesthesia on the mortality rate of people undergoing open abdominal aortic surgery. These benefits should be balanced with potential risk specific to this population (Hebl 2006; Horlocker 2010).

Implications for research.

For mortality, studies with a longer period of follow‐up (up to one year) could be useful.

Feedback

Feedback to Nishimori 2012

Summary

Summary Analysis 1.12. Comparison 1 Epidural versus systemic opioid (overall comparison), Outcome 12 Renal insufficiency) the numbers of the publication Park 2001 are incorrectly stated as "epidural 26/184 ‐ systemic opioid 53/190". Correct would be "epidural 5/184 ‐ systemic opioid 4/190". Following the correction, subtotal and total risk ratio will change. It might also change one of the conclusions, i.e. epidural analgesia would reduce renal complications. Alexander Koch

Reply

I agree with the feedback. The numbers in question is [are] indeed a mistake. The correct number of Park 2001 is 5/184 for epidural group and 4/190 for systemic opioid group. This makes the outcome to be insignificant. The Anaesthesia Group plan to update this review Mina Nishimori

Contributors

Summary author: Dr Alexander Koch. Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Therapy, University Hospital Frankfurt, Germany. I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback. Reply: Mina Nishimori (lead author)

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 March 2017 | Amended | Search reran; one potential new study added to awaiting classification (Owczuk 2016) and one to ongoing (Li 2015) |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2004 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 January 2016 | New search has been performed | One trial (Lombardo 2009) included in the last version (Nishimori 2012) was excluded (quasi‐randomized trial) One new study included (Muehling 2009). |

| 5 January 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New authors updated this review (Joanne Guay and Sandra Kopp). Conclusions not changed. |

| 13 March 2014 | Amended | Feedback posted |

| 13 April 2012 | Amended | Erratum corrected. In the plain language summary and abstract, we stated that the duration of intubation after surgery was reduced by roughly 20% in the epidural group. Since this does not correspond with the statement in the result section (48% reduction), we corrected the statement to "approximately half reduction". |

| 13 April 2012 | New search has been performed | In response to the peer reviewers' comments, we amended the following. 1. We reformatted the text according to the recent changes in RevMan.

2. We reworded the text.

3. We revised the statistical aspects of our review.

|

| 13 April 2012 | New search has been performed | We updated our search from 2004 to 2010. We did a full paper review of nine studies from our updated search, and excluded eight (Ali 2010; Beilin 2008; Donatelli 2006; Goldmann 2008; Kawasaki 2007; Murakami 2009; Yarendi 2007; Zhang 2007) and included one (Lombardo 2009a). We also included one study found from our original search (2004), which was waiting for evaluation (de Lis 1990). Two additional papers are awaiting evaluation as they need to be translated (Hu 2006a; Pan 2006a). These new studies did not change our conclusions. |

| 13 April 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We included Dr Hui Zheng as our co‐author. |

| 13 April 2012 | New search has been performed | We revised the plain language summary. We also reworded the text. We completed the 'risk of bias tables' and two 'risk of bias figures'. |

| 17 January 2011 | Amended | During the process of updating this review, we found the following errors and corrected them. Erratum corrected: In the text we reported that we found 39 ineligible studies, but in fact, it was 40. There were two duplicate publications and that is why we calculated incorrectly. Erattum corrected: In the previous additional table 3 (now Appendix 4) (definitions of postoperative complications), section of "overall cardiac event" we reported "Yeager 1987" as "Peyton 1987." We corrected it and made a link to the reference. Erattum corrected: Asuero 1990a study characteristics section was completed. We moved the additional tables to the appendices |

| 29 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 21 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 May 2006 | Amended | The following changes have been made to the previously published protocol: (1) We edited the wording of the background and methods section. (2) We searched the OVID version of CENTRAL instead of the Cochrane Library CD version of CENTRAL. (3) Because there was a possibility that the search strategy we published in our protocol might miss trials that included aortic abdominal surgery patients as a sub‐group of participants, we removed the search terms indicating aortic abdominal surgery, then did the search again (the amended search strategy is shown in 'Additional Table 02'). |

Notes

Update 2015

We updated the background.

We excluded quasi‐randomized studies.

We amended the interventions (see below).

We rephrased the criteria for inclusion of studies.

We included postoperative epidural analgesia, either lumbar or thoracic. Systemic opioid‐based pain relief included opioid drugs given by the following routes: intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous. Bolus dosing, infusion, or patient‐controlled analgesia devices were eligible for inclusion. For epidural analgesia, we included all combinations of drugs and all start times (pre‐ or postoperatively).

Updated review ‐ Guay 2015

We included intraoperative or postoperative (or both) epidural anaesthesia/analgesia added to general anaesthesia (either lumbar or thoracic) compared to general anaesthesia alone. We included all combinations of drugs and all start times (pre‐ or postoperatively). We imposed no restriction regarding the mode of analgesia used in the control group and included systemic opioid‐based pain relief with opioid drugs given by the following routes: intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous. For both groups, bolus dosing, infusion, or patient‐controlled analgesia devices were eligible for inclusion.

5. We changed the outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Death from all causes within 30 days of surgery, or death from all causes during hospitalization.

Postoperative cardiovascular complication: cardiac death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, angina, myocardial ischaemia, arrhythmias (supraventricular and ventricular), congestive heart failure, severe hypotensive episode that required treatment.

Postoperative respiratory complications: atelectasis, pneumonia, respiratory failure including prolonged mechanical ventilation or need to reinstate mechanical ventilation.

Postoperative gastrointestinal complication.

Postoperative cerebrovascular complication.

Postoperative renal complication.

Postoperative deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Secondary outcomes

Time to extubation.

Postoperative pain scores (at rest or with movement).

Any indicator for postoperative bowel motility: time to first bowel sounds, flatus, bowel movement, or time to first drinking or eating.

Any indicator for postoperative mobilization: any type of functionality score or time to first ambulation.

Length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

Length of hospital stay.