Abstract

Background

The benefits of erythropoiesis‐stimulating agents (ESA) for chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients have been previously demonstrated. However, the efficacy and safety of short‐acting epoetins administered at larger doses and reduced frequency as well as of new epoetins and biosimilars remains uncertain.

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of different routes, frequencies and doses of epoetins (epoetin alpha, epoetin beta and other short‐acting epoetins) for anaemia in adults and children with CKD not receiving dialysis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 12 September 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies specifically designed for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE; handsearching conference proceedings; and searching the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised control trials (RCTs) comparing different frequencies, routes, doses and types of short‐acting ESAs in CKD patients.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study eligibility and four authors assessed risk of bias and extracted data. Results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) or risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used. Statistical analyses were performed using the random‐effects model.

Main results

We identified 14 RCTs (2616 participants); nine studies were multi‐centre and two studies involved children. The risk of bias was high in most studies; only three studies demonstrated adequate random sequence generation and only two studies were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. Blinding of participants and personnel was at low risk of bias in one study. Blinding of outcome assessment was judged at low risk in 13 studies as the outcome measures were reported as laboratory results and therefore unlikely to be influenced by blinding. Attrition bias was at low risk of bias in eight studies while selective reporting was at low risk in six included studies.

Four interventions were compared: epoetin alpha or beta at different frequencies using the same total dose (six studies); epoetin alpha at the same frequency and different total doses (two studies); epoetin alpha administered intravenously versus subcutaneous administration (one study); epoetin alpha or beta versus other epoetins or biosimilars (five studies). One study compared both different frequencies of epoetin alpha at the same total dose and at the same frequency using different total doses.

Data from only 7/14 studies could be included in our meta‐analyses. There were no significant differences in final haemoglobin (Hb) levels when dosing every two weeks was compared with weekly dosing (4 studies, 785 participants: MD ‐0.20 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.07), when four weekly dosing was compared with two weekly dosing (three studies, 671 participants: MD ‐0.16 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.10) or when different total doses were administered at the same frequency (four weekly administration: one study, 144 participants: MD 0.17 g/dL 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.53).

Five studies evaluated different interventions. One study compared epoetin theta with epoetin alpha and found no significant differences in Hb levels (288 participants: MD ‐0.02 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.21). One study found significantly higher pain scores with subcutaneous epoetin alpha compared with epoetin beta. Two studies (165 participants) compared epoetin delta with epoetin alpha, with no results available since the pharmaceutical company withdrew epoetin delta for commercial reasons. The fifth study comparing the biosimilar HX575 with epoetin alpha was stopped after patients receiving HX575 subcutaneously developed anti‐epoetin antibodies and no results were available.

Adverse events were poorly reported in all studies and did not differ significantly within comparisons. Mortality was only detailed adequately in four studies and only one study included quality of life data.

Authors' conclusions

Epoetin alpha given at higher doses for extended intervals (two or four weekly) is non‐inferior to more frequent dosing intervals in maintaining final Hb levels with no significant differences in adverse effects in non‐dialysed CKD patients. However the data are of low methodological quality so that differences in efficacy and safety cannot be excluded. Further large, well designed, RCTs with patient‐centred outcomes are required to assess the safety and efficacy of large doses of the shorter acting ESAs, including biosimilars of epoetin alpha, administered less frequently compared with more frequent administration of smaller doses in children and adults with CKD not on dialysis.

Plain language summary

Short‐acting erythropoiesis agents in chronic kidney disease patients not requiring dialysis

What is the issue?

Anaemia due to reduced production by the kidneys of erythropoietin (a hormone which increases red cell production) is a major cause of tiredness and other problems experienced by people with chronic kidney disease requiring or not requiring dialysis.

Manufactured erythropoietins (epoetins) improve anaemia and are often prescribed for people with chronic kidney disease. Several different manufactured epoetins are now available.

What did we do?

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 12 September 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. We included randomised control trials (RCTs) comparing different frequencies, routes, doses and types of short‐acting ESAs in patients with chronic kidney disease.

What did we find?

We examined the evidence from 14 studies with 2616 participants with CKD not receiving dialysis published before 12 September 2016 to determine whether differences in improvement in anaemia and in side effects existed between different short‐acting epoetins or between the same epoetins given at different frequencies. We did not find any studies using different frequencies of epoetins in children.

We found that the traditionally shorter acting epoetins given less often (two weekly to every four weeks) resulted in similar correction of anaemia compared with administration every week or every two weeks; there were no differences in side effects between the different comparisons. One study comparing subcutaneous administration of a newly manufactured HX575 epoetin alpha compared with epoetin alpha was discontinued after two patients developed anti‐erythropoietin antibodies. However more studies are required as most studies were small and poorly designed, which limits their application to the care of patients.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus to weekly for anaemia in CKD patients not receiving dialysis.

| Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus to weekly for anaemia in CKD patients not receiving dialysis | ||||||

| Patient or population: anaemia in predialysis patients Intervention: epoetin alpha every 2 weeks Comparison: weekly | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with weekly | Risk with Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks | |||||

| Change in Hb level | The mean change in Hb level was 0 g/dL | The mean change in Hb level in the intervention group was 0.19 g/dL lower (0.32 g/dL lower to 0.06 g/dL lower) | ‐ | 798 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | downgraded for study limitations and indirectness |

| Number reaching target Hb | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 798 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | downgraded for study limitations and indirectness | |

| 960 per 1000 | 922 per 1000 (893 to 951) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 947 per 1000 | 910 per 1000 (881 to 938) | |||||

| Number of deaths | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.38 to 2.07) | 838 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | downgraded for study limitations and imprecision | |

| 28 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (10 to 57) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 22 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (9 to 46) | |||||

| Adverse events: RBC transfusions | Study population | RR 1.56 (0.71 to 3.45) | 580 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | downgraded for imprecision and study limitations | |

| 33 per 1000 | 52 per 1000 (23 to 114) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 37 per 1000 | 58 per 1000 (26 to 128) | |||||

| Adverse events: hypertension | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.55 to 1.32) | 838 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | downgraded for study limitations | |

| 100 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (55 to 132) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 95 per 1000 | 81 per 1000 (52 to 126) | |||||

| Adverse events: thrombovascular events | Study population | RR 1.41 (0.67 to 3.00) | 838 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | downgraded for study limitations and imprecision | |

| 28 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (18 to 83) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 27 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (18 to 80) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; Hb: haemoglobin; RBC: red blood cells | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 allocation concealment unclear in 3 of 4 studies

2 surrogate outcome

3 few studies with low numbers and wide confidence

4 allocation concealment unclear in 2 of 3 studies

Summary of findings 2. Epoetin alfa every four weeks versus with every two weeks in CKD patients not receiving dialysis.

| Epoetin alfa every four weeks versus with every two weeks in CKD patients not receiving dialysis | ||||||

| Patient or population: anaemia in predialysis patients Intervention: epoetin alpha every 4 weeks Comparison: every 2 weeks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with every 2 weeks | Risk with Epoetin alpha every 4 weeks | |||||

| Change in Hb level | The mean change in Hb level was 0 | The mean change in Hb level in the intervention group was 0.15g/dL lower (0.41 g/dL lower to 0.1g/dL more) | ‐ | 671 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | downgraded for study limitations, heterogeneity and indirectness |

| Number reaching target Hb | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.84 to 1.07) | 687 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | downgraded for study limitations, heterogeneity and indirectness | |

| 916 per 1000 | 870 per 1000 (769 to 980) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 895 per 1000 | 850 per 1000 (752 to 957) | |||||

| Number of deaths | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.33 to 2.75) | 724 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | downgraded for study limitations, imprecision | |

| 22 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (7 to 62) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 26 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (9 to 72) | |||||

| Adverse events: RBC transfusions | Study population | RR 1.26 (0.53 to 2.98) | 470 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | downgraded for study limitations, imprecision | |

| 38 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (20 to 114) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 35 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (18 to 103) | |||||

| Adverse events: hypertension | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.62 to 1.69) | 724 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | downgraded for study limitations | |

| 70 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (44 to 119) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 62 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (38 to 104) | |||||

| Adverse events: arteriovenous complications | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.39 to 2.68) | 724 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | downgraded for study limitations, imprecision | |

| 26 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (10 to 68) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 23 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (9 to 62) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; Hb: haemoglobin; RBC: red blood cells | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 two of the three studies had unclear allocation concealment

2 surrogate outcome

3 unexplained heterogeneity

4 small numbers with wide confidence intervals

Summary of findings 3. Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta in CKD patients not receiving dialysis.

| Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta in CKD patients not receiving dialysis | ||||||

| Patient or population: anaemia in predialysis patients Intervention: epoetin theta Comparison: epoetin beta | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with epoetin beta | Risk with Epoetin theta | |||||

| Final Hb | The mean final Hb was 0 g/dL | The mean final Hb in the intervention group was 0.02 g/dL lower (0.25 g/dL lower to 0.21 g/dL higher) | ‐ | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | downgraded for indirectness ‐ surrogate outcomes |

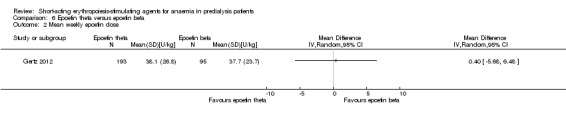

| Mean weekly epoetin dose | The mean weekly epoetin dose was 0 units/week | The mean weekly epoetin dose in the intervention group was 0.4 units per week higher (5.68 units per week lower 6.48 units/week higher) | ‐ | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | downgraded for indirectness ‐ surrogate outcomes and imprecision |

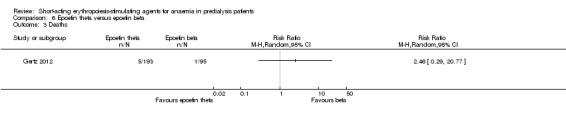

| Deaths | Study population | RR 2.46 (0.29 to 20.77) | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | downgraded for imprecision | |

| 11 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (3 to 219) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 11 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (3 to 218) | |||||

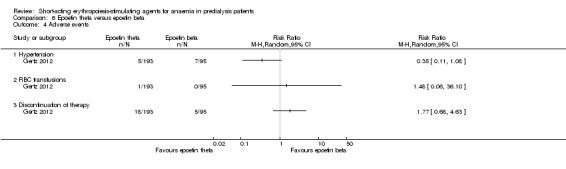

| Adverse events: hypertension | Study population | RR 0.35 (0.11 to 1.08) | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | downgraded for imprecision | |

| 74 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (8 to 80) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 74 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (8 to 80) | |||||

| Adverse events: RBC transfusions | Study population | RR 1.48 (0.06 to 36.10) | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | downgraded for imprecision | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse events: discontinuation of therapy | Study population | RR 1.77 (0.68 to 4.63) | 288 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | downgraded for imprecision | |

| 53 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (36 to 244) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 53 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (36 to 244) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; RBC: red blood cells | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Surrogate outcome, not a patient‐centred outcome

2 Small numbers, wide confidence intervals

Background

Description of the condition

Anaemia is defined as haemoglobin (Hb) levels < 12.0 g/dL and 13.0 g/dL in adult females and males respectively based on the World Health Organization's definition of anaemia (KDIGO 2012; WHO 2011). Anaemia is diagnosed in children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) if Hb concentration is < 11.0 g/dL in children aged from six months to five years, < 11.5 g/dL in children aged five to 12 years, and < 12.0 g/dL in children from 12 to 15 years of age according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines (KDIGO 2012). Anaemia is a known complication of CKD (Dmtrieva 2013) which develops as kidney function declines; prevalence increases as glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls. CKD stage 3 to 5 is a predictor variable of decline in Hb (Dmtrieva 2013).

Anaemia prevalence ranges from 25% to 70% (Hsu 2002; Koch 1991), and most people with CKD stage 5 (GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) are anaemic (Astor 2002). Anaemia related to CKD results in significant morbidity, mortality and increased cardiovascular events, with symptoms including lack of energy, breathlessness, dizziness, angina, poor appetite and decreased exercise tolerance (Canadian EPO 1990; Lundin 1989).

The primary cause of anaemia in CKD is decreased production of the naturally‐occurring hormone, erythropoietin (EPO) in the kidney. Anaemia may be exacerbated by concurrent iron deficiency anaemia (KDIGO 2012).

Prior to the availability of recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO), anaemia was managed with blood transfusions together with iron and folate supplements. Cloning of the human gene for EPO was achieved in 1983 (Lin 1985) and production of rHuEPO followed. The efficacy of erythropoiesis‐stimulating agents (ESA) treatment in dialysis patients was demonstrated in 1986 (Winearls 1986) and several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have documented a beneficial effect of ESA treatment in correcting the anaemia of CKD in non‐dialysis patients (Cody 2005; Stone 1988).

The increase in Hb levels following treatment with ESA leads to improved energy levels (Wolcott 1989), improved cardiac performance and increased ejection fraction (Pappas 2008) with normalisation of cardiac output and reduced left ventricular mass (Cannella 1990). The benefits of early treatment of anaemia with ESA in predialysis patients include increased exercise capacity, improved quality of life, improved cognitive function and a slower decline in kidney function (Ritz 2000; Roth 1994).

Description of the intervention

Administration of an ESA aims to replace endogenous EPO production, raise Hb levels and alleviate signs and symptoms of anaemia. Epoetin alpha has proven efficacy in treating anaemia in people with CKD (Eschbach 1987). Epoetin alpha has a relatively short half‐life and typically is administered twice or thrice weekly (Locatelli 2011). More recently new longer acting ESAs, which can be administered less frequently than short‐acting ESAs, have been developed allowing administration of ESA every one to four weeks depending on the preparation used and the individual patient response. Darbepoetin was the first ESA with a prolonged half‐life to enter the market enabling administration once a week to four weekly (Macdougall 1999). More recently, the use of the continuous EPO receptor activator (CERA), a pegylated epoetin, has extended dosing intervals to one dose every two to four weeks (Macdougall 2005). ESAs have to be administered intravenously or subcutaneously so the benefits of using ESAs in non‐dialysis CKD patients, who will generally receive subcutaneous injections in an outpatient setting, must be balanced against the inconvenience and/or discomfort of injections as well as potential harms of ESAs, which include hypertension, vascular access thrombosis and cardiovascular events. A significant concern in ESA therapy is the Hb target to be achieved. The CHOIR study reported a target Hb level of 13.5 g/dL compared with 11.3 g/dL was associated with increased mortality and cardiovascular risk and no considerable improvement in the quality of life. The study could not provide an explanation for poorer outcomes in patients with a higher target Hb (Singh 2006). Recommendations on when to commence ESA therapy are outlined in the KDIGO guidelines (KDIGO 2012). As the patents for epoetin alpha have expired, cheaper biosimilars of epoetin alpha have been developed. These biological products are highly similar though not identical to reference products and undergo a more limited appraisal before receiving marketing approval. As they are not generic versions of the reference products and could have differences particularly in adverse effects, these products should be submitted to rigorous assessment before marketing and to long term monitoring to ensure that adverse effects are recognised and attributed to the responsible biological preparation (Mikhail 2013; Schellekens 2009).

How the intervention might work

The primary cause of anaemia in CKD is the relative insufficiency of EPO which is mainly produced by peritubular fibroblasts in the kidney. EPO is part of a widespread system of hypoxia‐inducible gene expression mediated by hypoxia‐inducible transcription factors (HIFs).The factors associated with inadequate EPO production in progressive CKD remain unclear, though recent data indicate a deranged oxygen sensing, in addition to loss of EPO production, is involved (Bernhardt 2010). ESAs accelerate erythropoiesis, increase iron utilisation and raise Hb levels with clinical improvement in signs and symptoms of anaemia and avoidance of blood transfusions. ESA therapy aims to increase Hb levels slowly at a rate of 1 to 2 g/dL per month to correct anaemia. After correction of anaemia, dose adjustment may be necessary to maintain a stable Hb level. Anaemia is corrected slowly with ESA to avoid major side effects including hypertension and thrombotic events. ESA requirements are difficult to predict in individual patients, and may be increased in people with associated co‐morbidities including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic inflammation and severe secondary hyperparathyroidism. ESA requirements are generally lower in patients not receiving dialysis. A major issue in ESA use relates to the Hb target to be achieved with increased cardiovascular risk noted with higher Hb targets (Drueke 2006; Singh 2006). Recent systematic reviews have suggested that aiming for Hb levels similar to those seen in healthy adults is associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality due to cardiovascular events, such as stroke and hypertension (Palmer 2010). The mechanisms for these treatment‐related harms are poorly understood though observational studies suggest treatment related toxicity secondary to impaired Hb responses and incremental erythropoietin dosing (Szczech 2008). KDIGO guidelines (KDIGO 2012) recommend that in general ESAs should not be used to raise Hb levels > 11.5 g/dL.

Why it is important to do this review

In a previous Cochrane systematic review, which included 15 RCTs, rHuEPO (epoetin alpha) significantly increased Hb (two studies) or haematocrit (HCT) levels (five studies) compared with placebo or no treatment and significantly reduced blood transfusion requirements (Cody 2005). Determining the ESA agent to be used should include assessment of the drug's pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, route and frequency of administration, adverse effects, availability and any economic issues (KDIGO 2012). In most high income countries, the use of short‐acting ESAs (epoetin alpha, epoetin beta) in patients with CKD has been superseded by longer acting ESAs (darbepoetin, CERA) because of the reduced frequency of administration. In low income countries where newer longer acting ESAs are less likely to be accessible, clinicians may be limited to use short‐acting ESAs. The cost of using newer ESAs agents would have to be balanced against the costs and inconvenience of more frequent administration. Since the efficacy and safety of rHuEPO compared with placebo or no treatment has already been demonstrated (Cody 2005), this review aims to evaluate short‐acting ESAs (epoetin alpha, epoetin beta, other epoetins or epoetin biosimilars) in patients, both adults and children with CKD not on dialysis (CKD stages 2 to 5) with reference to route of administration (intravenous versus subcutaneous), frequency of administration, different doses and direct comparisons of different epoetins to provide additional information about the value of these agents for institutions where shorter acting ESAs are used.

This review will not evaluate studies comparing short‐acting with longer acting ESAs in CKD, different longer acting ESAs in CKD, different routes of administration in dialysis patients or kidney transplant recipients and different Hb targets as these are subject of other Cochrane published or planned systematic reviews (Hahn 2014; Palmer 2012; Palmer 2014a; Palmer 2014b; Strippoli 2006).

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of different routes, frequencies and doses of epoetins (epoetin alpha, epoetin beta and other short‐acting epoetins) for anaemia in adults and children with CKD not receiving dialysis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at epoetins (short‐acting ESAs) for treatment of anaemia in patients with CKD not on dialysis.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients of any age (adults and children) with anaemia due to CKD (stages 2 to 5) of any severity, who were not receiving dialysis, were included. The definitions of CKD and anaemia used in individual studies were used in this review.

Exclusion criteria

Patients of any age receiving dialysis treatment. Patients receiving long‐acting ESAs or included in studies comparing shorter with longer acting ESAs were excluded. Kidney transplant recipients were also excluded.

Types of interventions

Short‐acting ESAs including epoetins alpha (Eprex®, Procrit®, Epogen®), beta (Recormin®), delta (Dynepo®), epoetin theta (Biopoin®) and biosimilars of epoetin alpha (HX575, EPO‐ hexal®, Abseamed®), epoetin zeta (Silapo®, Retacrit®, Epoetin Hospira®)

Short‐acting ESAs including epoetins with different routes of administration

Short‐acting ESAs including epoetins used at different frequencies of administration

Short‐acting ESAs including epoetins used at different doses

Head‐to‐head comparisons of different short‐acting ESAs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Death

All‐cause mortality

Mortality due to cardiac disease or cerebrovascular events

-

Measures of correction of anaemia

Values of Hb/HCT or change in Hb/HCT at the end of the study

Quality of life.

Secondary outcomes

-

Hypertension and blood pressure outcomes

Hypertension (number of patients presenting one or more episodes of hypertension)

Systolic blood pressure at end of treatment (mm Hg)

Diastolic blood pressure at end of treatment (mm Hg).

Cardiovascular morbidity

Cerebrovascular morbidity

-

Adverse effects

Number needing blood transfusion

Thrombotic events

Number ceasing ESA for adverse effects

Number of patients requiring hospitalisations for any cause

Number of patients developing antibody‐mediated pure red cell aplasia

Number of patients developing a malignancy.

Kidney function measures (GFR, serum creatinine (SCr), doubling of SCr) as reported by the authors of primary studies

Need for iron supplementation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 12 September 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from several sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register were identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed the retrieved abstracts and, if necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by at least two authors using standard data extraction forms. Where there was more than one publication of a study, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. all‐cause mortality, adverse events, number needing transfusions) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. final Hb/HCT or change in Hb/HCT, blood pressure, SCr), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only data from the first period of treatment in cross‐over studies (Higgins 2011). Data expressed in different metrics were analysed using SMD.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing corresponding authors) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. We aimed to analyse available data in meta‐analyses using intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data. However, where only ITT data were available graphically or were not provided and additional information could not be obtained from the study authors, per‐protocol (PP) data was used in analyses.

We imputed a change‐from‐baseline standard deviation using an imputed correlation coefficient when sufficient data were available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

The search strategy applied aimed to reduce publication bias caused by lack of publication of studies with negative results. We investigated for publication bias using funnel plots if there were sufficient studies of each comparison (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data were summarised using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen. We qualitatively summarised data where insufficient data were available for meta‐analysis. Where there were multiple publications of the same study, all reports were reviewed to ensure that all details of methods and results were included. Qualitative review was conducted for adverse events and quality of life outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (participants, interventions and study quality). Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age (adult versus children) or stage of CKD. Heterogeneity in interventions could be related to dose, duration or frequency of rHuEPO treatment or to the route of administration. . Where possible, the risk ratio with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or to another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses tested decisions where inclusion of a study may have altered the results of the meta‐analysis. In particular, sensitivity analysis may be used to test decisions where ITT and PP data were included in the same analyses.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

-

Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks compared to weekly for anaemia in CKD patients not receiving dialysis (Table 1)

Final or change in Hb level (g/dL)

Number reaching target Hb

Number of deaths

Number with adverse events: red blood cell transfusions, hypertension, thrombovascular events

-

Epoetin alfa every four weeks compared with every two weeks in CKD patients not receiving dialysis (Table 2)

Final or change in Hb level (g/dL)

Number reaching target Hb

Number of deaths

Number with adverse events: red blood cell transfusions, hypertension, thrombovascular events

-

Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta (Table 3)

Final Hb (g/dL)

Mean weekly epoetin dose (U/kg)

Number of deaths

Number with adverse events: hypertension, red blood cell transfusions, discontinuation of therapy.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

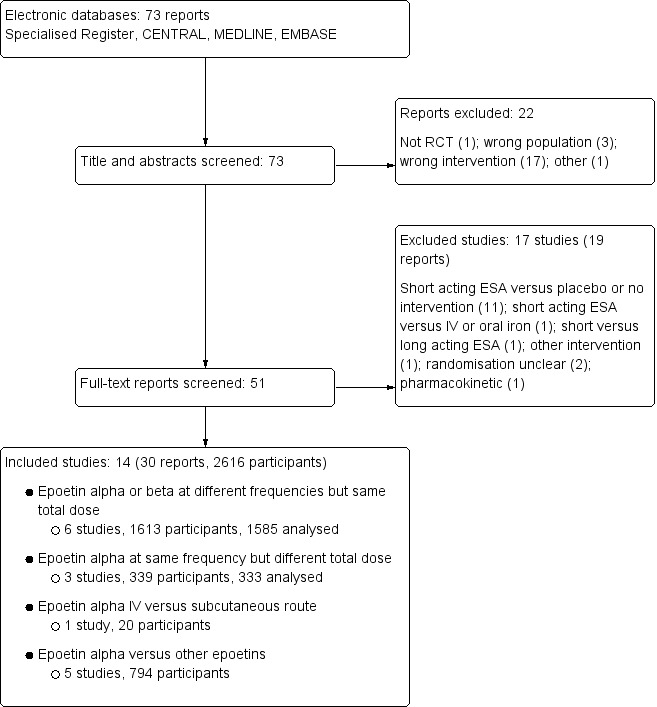

Seventy‐three reports were identified from the search to 12 September 2016. After title and abstract screening 22 reports were excluded. Full‐text review was carried out the remaining 51 reports. Fourteen studies (30 reports) (Aggarwal 2002; Akiba 1992; Amon 1992; Frenken 1989; Gertz 2012; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998; Spinowitz 2008) were included and 17 studies (19 reports) (Brown 1988; Clyne 1992; Duliege 2005; Furukawa 1992; Li 2004; Meloni 2003; NCT00240734; NCT00492427; NCT00563355; Patel 2012; Schwartz 1989; Shaheen 1983; Singh 1999; Teehan 1990; Teplan 1995; Yamazaki 1993; Zheng 1992) were excluded. Two recently completed studies (NCT01576341; NCT01693029) will be assessed in a future update of this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The 14 studies were divided into four treatment comparisons groups (Figure 1).

Epoetin alpha or beta administered at different frequencies using the same total dose

Six studies (Amon 1992; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998; Spinowitz 2008) (1613 enrolled/1585 evaluated participants) compared epoetin alpha or beta at different frequencies using the same total dose in each group.

Four studies (Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008) with 840 enrolled (838 analysed) participants compared epoetin alpha administered at 10,000IU per week with 20,000IU given every two weeks.

Three studies (Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008) with 724 analysed participants also compared epoetin alpha administered at 20,000 IU every two weeks with 40,000 IU every four weeks.

Amon 1992 (22 enrolled, 18 evaluated) compared subcutaneous epoetin alpha 50 IU/kg three times a week with 150 IU/kg given once weekly in children.

Sohmiya 1998 (5 enrolled, 5 evaluated) compared continuous infusion of epoetin beta with weekly subcutaneous injections for four weeks using the same total dose in each group in a cross over study.

Epoetin alpha administered at the same frequency using different total doses

Three studies (Akiba 1992; Frenken 1989; Spinowitz 2008) (339 enrolled/333 analysed participants) compared epoetin alpha at different doses but at the same frequencies.

Spinowitz 2008 (150 enrolled/144 evaluated) compared 20,000 IU given four weekly with 40 000IU given four weekly

Akiba 1992 (165 enrolled and evaluated) compared 3000 IU, 6000 IU and 12 000 IU given weekly to three groups

Frenken 1989 (24 enrolled and evaluated) compared 50 IU/Kg, 100 IU/kg and 150 IU/Kg given three times weekly.

Epoetin alpha intravenous versus subcutaneous administration

Aggarwal 2002 (20 participants enrolled and evaluated) compared subcutaneous with intravenous administration of epoetin alpha.

Epoetin alpha or beta versus other epoetins or biosimilars of epoetin alpha

Five studies Gertz 2012; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008;Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000) (794 participants) were included in this comparison.

Gertz 2012 (288 enrolled and evaluated) compared weekly subcutaneous epoetin theta with epoetin beta

Haag‐Weber 2012 (337 enrolled) compared a bio‐similar HX575 epoetin alpha with epoetin alpha (Eprex). This study was terminated due to the development of neutralising antibodies in two patients receiving subcutaneous HX575. Efficacy could not be assessed because the authors did not provide the number of patients, who contributed data to efficacy endpoints. Limited safety data were available.

Two studies (Mignon 2000, Knebel 2008) (140 enrolled) compared subcutaneous administration of epoetin delta with epoetin alpha. Both studies were terminated before completion when the pharmaceutical company ceased production of epoetin delta for commercial reasons and no data were available.

Kronborg 1994 (29 enrolled and evaluated) compared pain scores in participants treated with epoetin alpha or epoetin beta given subcutaneously using a visual analogue scale (VAS) and a verbal descriptive scale (VDS). As the results included a median with inter‐quartile ranges the data could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Excluded studies

Seventeen studies were excluded. Eleven studies were ineligible as they compared a short‐acting ESA with placebo or no treatment (Brown 1988; Clyne 1992; Meloni 2003; NCT00240734; NCT00563355; Patel 2012; Schwartz 1989; Shaheen 1983; Singh 1999; Teehan 1990; Teplan 1995). NCT00492427 compared short‐acting ESA with the long acting ESA, darbepoetin and this study is included in another review (Palmer 2014b). Three studies assessed other interventions, or were pharmacokinetic studies (Duliege 2005; Furukawa 1992; Li 2004). Randomisation was unclear in two studies (Yamazaki 1993; Zheng 1992).

Risk of bias in included studies

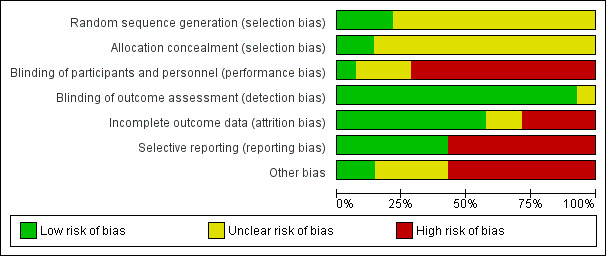

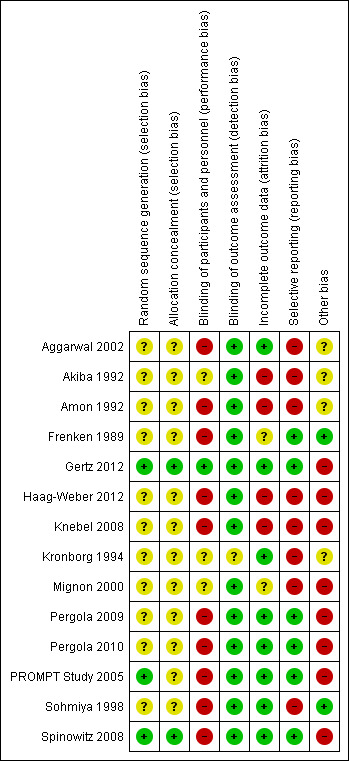

The results of the risk of bias assessment are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation was deemed at low risk of bias in three studies (Gertz 2012; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008) and unclear in the remaining eleven studies (Aggarwal 2002; Akiba 1992; Amon 1992; Frenken 1989; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; Sohmiya 1998).

Allocation concealment was at low risk of bias in two studies (Gertz 2012; Spinowitz 2008) and unclear in the remaining twelve studies (Aggarwal 2002; Akiba 1992; Amon 1992; Frenken 1989; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998).

Blinding

Only one study (Gertz 2012) was blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias for performance bias. Ten studies were not blinded and determined as high risk of performance bias (Aggarwal 2002; Amon 1992; Frenken 1989; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998; Spinowitz 2008). Blinding was unclear in the remaining three studies (Akiba 1992; Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000).

As the primary outcomes (final Hb level or change in Hb level) in all studies were based on laboratory assessment, and therefore unlikely to be influenced by blinding, 13 studies were deemed to be at low risk of detection bias. The study by Kronborg 1994 was considered at unclear risk of detection bias; it assessed pain scores and was said to be double‐blinded though no information was provided as to how this was performed.

Incomplete outcome data

Eight studies were determined to be at low risk of attrition bias (Aggarwal 2002; Gertz 2012; Kronborg 1994; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998; Spinowitz 2008). Four studies were at high risk of bias because meta‐analyses could not be performed as total patient numbers were not provided (Akiba 1992; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008) or because more than 10% patients were excluded from analysis (Amon 1992). Attrition bias was deemed unclear in the remaining two studies (Frenken 1989; Mignon 2000).

Selective reporting

Studies that did not provide data on final or change in Hb and on patient‐centred outcomes including adverse events such as blood transfusions, vascular access complications or all‐cause mortality were considered to be at high risk for selective reporting. Eight studies were considered at high risk of reporting bias (Aggarwal 2002; Akiba 1992; Amon 1992; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Kronborg 1994; Mignon 2000; Sohmiya 1998). Six studies (Amon 1992; Gertz 2012; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008) were assessed at low risk for selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

Only two studies were assessed at free of other potential bias sources (Frenken 1989; Sohmiya 1998). Eight studies were industry funded and determined as at high risk of bias (Gertz 2012; Haag‐Weber 2012; Knebel 2008; Mignon 2000; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008). In the remaining four studies it was unclear whether the study was free of other potential sources of bias (Aggarwal 2002; Akiba 1992; Amon 1992; Kronborg 1994).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Epoetin alpha administered at different frequencies using the same total dose

Six studies investigated this comparison (Amon 1992; Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Sohmiya 1998; Spinowitz 2008).

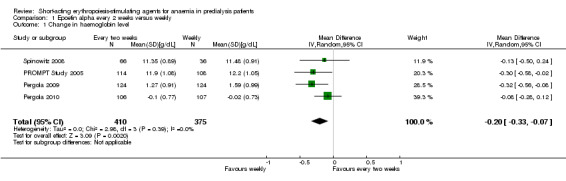

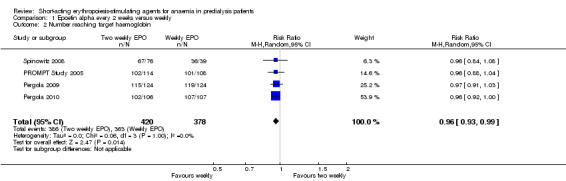

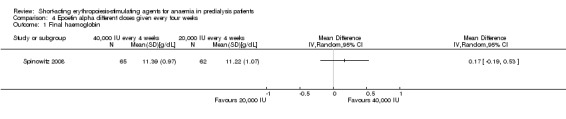

Epoetin alpha weekly versus every two weeks using same total dose of epoetin

In meta‐analyses of four non‐inferiority studies (Pergola 2009; Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008), final Hb levels (Analysis 1.1 (4 studies, 785 participants): MD ‐0.20 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.07) and the number achieving target Hb were statistically significantly higher in patients receiving weekly doses compared with two weekly doses (Analysis 1.2 (4 studies, 798 participants): RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99). The differences were not considered to be clinically significant. No significant heterogeneity was noted.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus weekly, Outcome 1 Change in haemoglobin level.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus weekly, Outcome 2 Number reaching target haemoglobin.

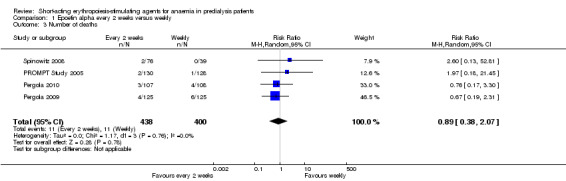

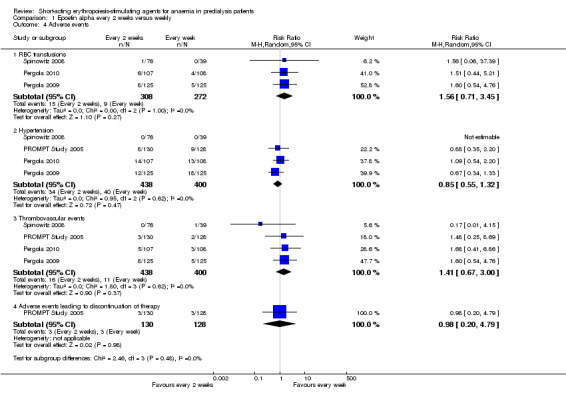

There were no significant difference in all‐cause mortality (Analysis 1.3 (4 studies, 838 participants): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.07), the number requiring transfusion (Analysis 1.4.1 (3 studies, 580 participants): RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.71 to 3.45), the number with hypertension (Analysis 1.4.2 (4 studies, 838 participants): RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.32), the number with thrombovascular complications Analysis 1.4.3 (4 studies, 838 participants): RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.00) or the number discontinuing therapy due to adverse effects (Analysis 1.4.4 (1 study, 258 participants): RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.79).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus weekly, Outcome 3 Number of deaths.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus weekly, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

No neutralising antibodies were detected in study participants in Pergola 2009 and Pergola 2010. Most of the deaths were due to cardiovascular complications reflecting the underlying cardiovascular morbidity of the population studied. Only one study (PROMPT Study 2005) performed quality of life (QOL) assessments and reported no statistical differences in the final QOL scores between groups receiving epoetin once weekly or two weekly.

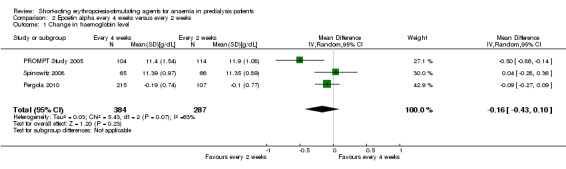

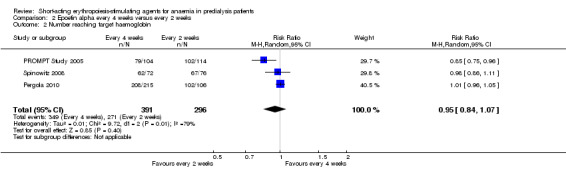

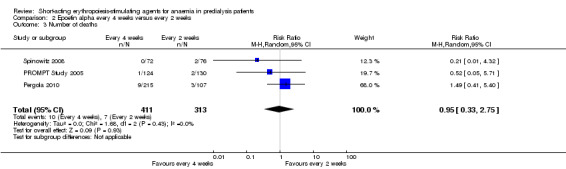

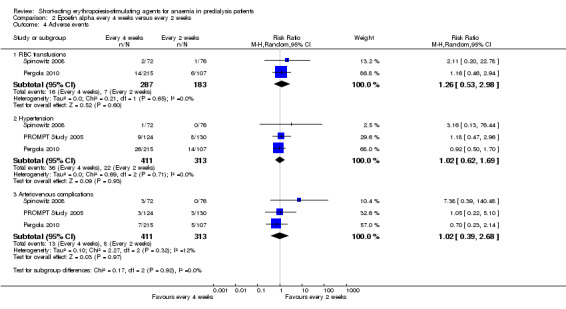

Epoetin alpha every two weeks versus every four weeks using same total dose of epoetin

In meta‐analyses of three non‐inferiority studies (Pergola 2010; PROMPT Study 2005; Spinowitz 2008), there were no significant differences in final Hb levels (Analysis 2.1 (3 studies, 671 participants): MD ‐0.16 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.10; I2 = 63%) or in the number reaching target Hb levels (Analysis 2.2 (3 studies, 687 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.07) with dosing every two weeks compared with every four weeks. There was unexplained marked heterogeneity between these studies.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epoetin alpha every 4 weeks versus every 2 weeks, Outcome 1 Change in haemoglobin level.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epoetin alpha every 4 weeks versus every 2 weeks, Outcome 2 Number reaching target haemoglobin.

There were no significant differences in all‐cause mortality (Analysis 2.3 (3 studies, 724 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.75), the number requiring transfusions (Analysis 2.4.I (2 studies, 470 participants): RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.98); the number with hypertension (Analysis 2.4.2 (3 studies, 724 participants): RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.69); and the number with thrombovascular complications (Analysis 2.4.3 (3 studies, 724 participants): RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.39 to 2.68). PROMPT Study 2005 noted no difference in final QOL scores between participants who received epoetins at two weekly or four weekly intervals.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epoetin alpha every 4 weeks versus every 2 weeks, Outcome 3 Number of deaths.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epoetin alpha every 4 weeks versus every 2 weeks, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

Other studies

Amon 1992 found that the time to reach a Hb level greater than 11.5 g/dL were significantly longer with weekly administration (15.6 weeks) compared with thrice weekly administration (9.3 weeks). Adverse effects were uncommon and did not differ between groups and there was no deterioration in glomerular filtration rate across the two groups. However there was no significant difference in mean dose/week to sustain Hb levels between different frequencies of administration.

Sohmiya 1998 in a cross‐over study found that continuous subcutaneous infusion of epoetin beta resulted in a significantly greater increase in Hb levels compared with weekly subcutaneous injections (2.56 ± 0.77 g/dL versus 0.28 ± 0.62 g/dL, P < 0.05)

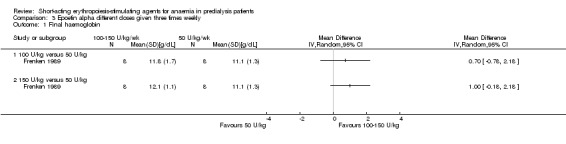

Epoetin alpha administered at same frequency using different total doses

Three studies reported on this comparison (Akiba 1992; Frenken 1989; Spinowitz 2008)

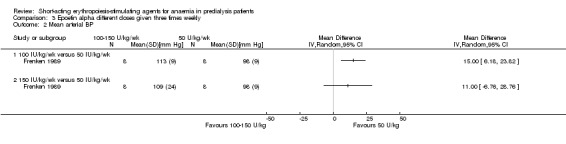

Epoetin alpha different doses given three times weekly

Frenken 1989 reported no statistical significance in the final Hb in groups which received 100 IU/kg/dose (Analysis 3.1.1 (1 study, 16 participants): MD 0.70 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.78 to 2.18) or 150 IU/kg/dose (Analysis 3.1.2 (1 study, 16 participants): MD 1.00 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 2.18) compared with 50 IU/kg/dose. Final mean arterial blood pressures and serum creatinine levels did not differ between subgroups (Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3). No anti‐erythropoietin antibodies were detected in the study participants. The study reported overall improvement in well‐being in all participants receiving epoetin.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epoetin alpha different doses given three times weekly, Outcome 1 Final haemoglobin.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epoetin alpha different doses given three times weekly, Outcome 2 Mean arterial BP.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epoetin alpha different doses given three times weekly, Outcome 3 Final creatinine levels.

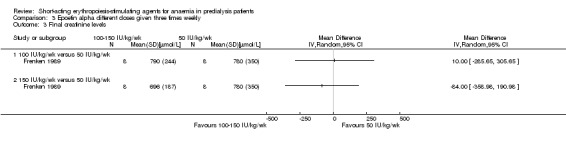

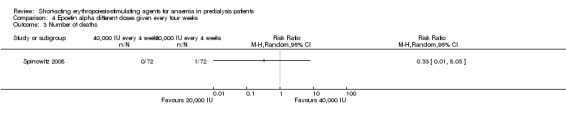

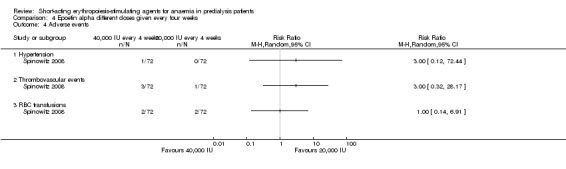

Epoetin alpha different doses given every four weeks

Spinowitz 2008 reported no significant difference in the final Hb level (Analysis 4.1 (1 study, 144 participants): MD 0.17 g/dL 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.53) and the number reaching target Hb (Analysis 4.2 (1 study, 144 participants): RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.24) when epoetin alpha was administered at 20,000 U compared with 40,000 U every four weeks. There was no significant difference in all‐cause mortality (Analysis 4.3.1), the number with hypertension (Analysis 4.4.1), thrombovascular complications (Analysis 4.4.2) or number of patients requiring transfusions (Analysis 4.4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epoetin alpha different doses given every four weeks, Outcome 1 Final haemoglobin.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epoetin alpha different doses given every four weeks, Outcome 2 Number reaching target haemoglobin.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epoetin alpha different doses given every four weeks, Outcome 3 Number of deaths.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epoetin alpha different doses given every four weeks, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

Epoetin alpha different doses given every week

Akiba 1992 reported that 6000 IU and 12,000 IU given weekly increased HCT levels more than 3000 IU/week. No standard deviations were provided.

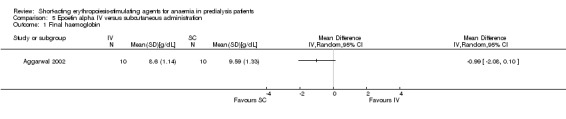

Epoetin alpha intravenous versus subcutaneous administration

Aggarwal 2002 reported no significant difference in final Hb at 12 weeks (Analysis 5.1 (20 participants): MD ‐0.99 g/dL, 95% CI ‐2.08 to 0.10) between intravenous and subcutaneous administration of epoetin alpha.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Epoetin alpha IV versus subcutaneous administration, Outcome 1 Final haemoglobin.

Epoetin alpha versus other epoetins or biosimilars

Five studies compared epoetin alpha with other epoetins or biosimilars.

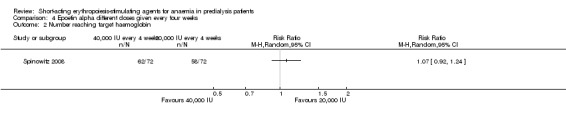

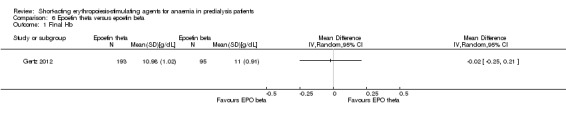

Gertz 2012 found no significant differences in final Hb (Analysis 6.1 (288 participants): MD ‐0.02 g/dL, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.21) and weekly epoetin doses (Analysis 6.2 (288 participants) MD 0.40 U/kg, 95% CI ‐5.68 to 6.48) between epoetin theta and epoetin beta. No significant differences were noted in all‐cause mortality (Analysis 6.3 (288 participants): RR 2.46, 95% CI 0.29 to 20.77), hypertension (Analysis 6.4.1 (288 participants): RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.08); transfusions (Analysis 6.4.2 (288 participants): RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.06 to 36.10) and discontinuation of therapy (Analysis 6.4.3 (288 participants): RR 1.77, 95% CI 0.68 to 4.63). No neutralising antibodies were noted in either intervention group. Most of the deaths were due to cardiovascular complications reflecting the population studied.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta, Outcome 1 Final Hb.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta, Outcome 2 Mean weekly epoetin dose.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta, Outcome 3 Deaths.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Epoetin theta versus epoetin beta, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

The quality of this single study was assessed as moderate for the surrogate outcome of final Hb but as low for mean weekly epoetin dose because of imprecision (Table 3). The quality of evidence for patient‐centred outcomes was assessed as low for all‐cause mortality, need for blood transfusion and discontinuation of medications and moderate for hypertension because of imprecision due to small numbers of events

Haag‐Weber 2012 (337 participants) compared the biosimilar HX575 epoetin alpha with epoetin alpha; both medications were administered subcutaneously. The study was ceased when two patients receiving HX575 developed antibodies to epoetin and pure red cell aplasia and HX575 epoetin alpha was withdrawn for subcutaneous administration. The change in Hb from baseline at 13 weeks did not differ between groups (HX575 2.2 ± 0.9 g/dL; epoetin alpha 2.2 ± 1.0 g/dL) but the data could not be included in meta‐analyses since no denominators were provided and information could not be obtained from the authors.

Mignon 2000 (65 participants) found no significant differences in response between epoetin delta and epoetin alpha when both were given at the same dose (50 IU/kg/wk). Adverse events were similar between epoetin delta and epoetin alpha. No data were available from Knebel 2008 (60 participants). Since epoetin delta production was ceased for commercial reasons and no information could be obtained from the pharmaceutical company, no meta‐analyses were performed.

Kronborg 1994 (29 participants) found that pain scores were higher in participants treated with subcutaneous epoetin alpha compared with epoetin beta. The results were provided as median with inter‐quartile ranges so could not be included in a meta‐analysis.

Other outcomes

From the available studies, we were not able to analyse the outcomes of causes of death, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity, kidney function, number of hospitalisations, additional requirement for IV iron, serious infections, or de novo malignancies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Fourteen studies (30 reports) with 2616 participants were included in this review, which evaluated the efficacy and safety of short‐acting ESAs in CKD patients, not requiring dialysis.

Six studies (1613 enrolled participants) compared epoetin alpha or epoetin beta at different frequencies using the same total dose in each group, with two studies having insufficient data for inclusion in meta‐analyses. Among four studies, no significant differences in end of study Hb, in the number of participants achieving target Hb, in all‐cause mortality or in adverse effects were identified when dosing every two weeks was compared with weekly dosing or when four weekly dosing was compared with two weekly dosing. These data suggest that larger doses of short‐acting epoetins given less frequently can be administered to CKD patients not requiring dialysis without a loss of efficacy or an increase in adverse effects. However this conclusion is based on low quality evidence (Table 1; Table 2). Three studies (including Spinowitz 2008, in which different frequencies were also evaluated) compared different total doses of epoetin alpha given at the same frequency though data from only two studies could be included in meta‐analyses. Both studies found no significant difference in final Hb or adverse effects with different total doses.

The remaining five studies evaluated different interventions. One study (288 participants) compared epoetin theta with epoetin alpha and found no significant differences in efficacy or adverse effects. Two studies (125 participants) compared epoetin delta with epoetin alpha. However no results were available since the pharmaceutical company withdrew epoetin delta for commercial reasons. The fourth study was terminated before completion after two patients receiving the biosimilar epoetin, HX575 epoetin alpha, developed anti‐epoetin antibodies and pure red cell aplasia. The fifth study found significantly higher pain scores with subcutaneous epoetin alpha compared with epoetin beta.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

For this review we were only able to identify 14 studies (2616 participants), which evaluated different frequencies, doses or routes of administration of the same epoetins or compared different epoetins in pre‐dialysis patients. Only seven studies contributed data to meta‐analyses with two of these studies enrolling only 20 and 24 patients respectively. Two studies evaluated children and neither had sufficient data for inclusion in meta‐analyses. Two studies were terminated before completion without available data when the pharmaceutical company ceased production of epoetin delta for commercial reasons. One study was terminated when two patients developed antibody mediated pure red cell aplasia with HX575 epoetin alpha, a biosimilar epoetin. No studies in pre‐dialysis patients were identified, which evaluated HX575 epoetin alpha, given intravenously, or of SB309 (epoetin zeta) given intravenously or subcutaneously. These biosimilar epoetins are approved for use by the European Medicines Agency. Preliminary information indicates that SB309 (epoetin zeta, Epoetin Hospira®) has not been approved for use in the USA (Big Molecule Watch Blog 2015).

Patient‐centred outcomes were generally poorly reported. Only one study reported on a quality of life assessment with no differences identified in end of study quality of life scores between different frequencies of epoetin alpha administration (PROMPT Study 2005). Six studies reported on all‐cause mortality. Data on hypertension and thrombovascular events, adverse effects known to be associated with epoetin administration, could be included in meta‐analyses from only five studies. Data from four studies on the number of participants, requiring blood transfusions, could be included in meta‐analyses. Anti‐erythropoietin antibodies, which can cause pure red cell aplasia, were assessed In only five studies.

Quality of the evidence

Of the fourteen studies included in this review, four studies were available in abstract format only.

Only three of 14 studies demonstrated adequate random sequence generation, with only two studies assessed as showing low risk of bias for allocation concealment. Blinding of participants and personnel was at low risk of bias in one study only. Blinding of outcome assessment was judged at low risk in 13 studies as the outcome measures were laboratory based. Attrition and reporting bias were at low risk of bias in eight and seven studies respectively (Figure 3).

Only five of 14 studies could be included in the Summary of Findings tables as other comparisons included single small studies only or data which could not be included in the meta‐analyses. Overall the quality of the studies (GRADE 2011a; GRADE 2011b) included in meta‐analyses was assessed as low indicating that our confidence in the results is significantly reduced because of poor study quality and the use of surrogate outcomes as the primary outcomes of the included studies.

The quality of the studies included in meta‐analyses comparing epoetin alpha every two weeks with weekly administration (Table 1) and in meta‐analyses comparing epoetin alpha every four weeks with two weekly administration (Table 2) for the efficacy outcomes of change in Hb level and number reaching target Hb were assessed as low or very low. These were down‐graded for indirectness on the GRADE profile, since these were surrogate outcomes and not patient‐centred outcomes. In the comparison of epoetin alpha given every four weeks compared with every two weeks, the results were further downgraded because of marked unexplained heterogeneity. In addition the quality of the evidence for efficacy was downgraded because of poor study design and/or reporting particularly of sequence generation and allocation concealment and for imprecision, where small numbers of events resulted in wide confidence intervals. Outcomes for adverse effects were downgraded because of poor study design and imprecision.

The quality of the single study included in meta‐analyses comparing epoetin theta with epoetin beta was assessed as moderate for the surrogate outcome of final Hb but as low for mean weekly epoetin dose because of imprecision (Table 3). The quality of evidence for patient‐centred outcomes was assessed as low for all‐cause mortality, need for blood transfusion and discontinuation of medications and moderate for hypertension because of imprecision due to small numbers of events.

Potential biases in the review process

For this review a comprehensive search of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register was performed, which reduced the likelihood that eligible published studies were omitted from the review. Eligible studies published after the last search date of 12 September 2016 or published in congress proceedings not routinely searched could have been missed. Four studies were only available in abstract form which provided limited information on study methods and results. Inclusion of these studies could be a source of bias.

The review was completed independently by at least three authors, who participated in all steps of the review. This limited the risk of errors in determining study eligibility, data extraction, risk of bias assessment and data synthesis.

Many of the earlier epoetin alpha studies were small with incomplete information on study methods and results. Further information could not be obtained about these studies from investigators or the literature.

Although six of the included studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, these were multi‐centre studies and so were able to attract larger patient numbers. In two of these studies per‐protocol data were included in meta‐analyses for the primary outcomes of final Hb or change in Hb, since ITT data were only presented graphically. In both studies the authors reported that sensitivity analyses using ITT populations were consistent with those from the per‐protocol populations, thus increasing confidence in the findings.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No evidence was identified by the KDIGO working group to suggest that any given type of ESA was superior to another in terms of efficacy and safety (KDIGO 2012). The Working Group suggested ESA choice was dependent on patient and country specific issues including availability, cost and treatment setting. The NICE guidelines 2015 (NICE 2015) suggest the choice of ESA should be discussed with the patient with anaemia and CKD when initiating the patient on treatment, taking into consideration the route of administration and the local availability of ESA. There is no evidence to distinguish between ESAs in term of efficacy. The findings of this systematic review confirm these recommendations.

The findings of this review complement other Cochrane Kidney and Transplant reviews of ESA including an updated review comparing epoetin in pre‐dialysis patients with placebo or no specific treatment (Cody 2016), a review evaluating the benefits and harms of different Hb or HCT targets in CKD patients receiving ESA treatment for anaemia (Strippoli 2006), a review evaluating darbepoetin (Palmer 2014b) and a network meta‐analysis of studies of any ESA formulation (Palmer 2014a). While ESAs clearly reduce the need for blood transfusion, no systematic review to date has found clear evidence for the superiority of any ESA formulation over any other formulation based on available efficacy and safety data.

For consumers, clinicians and funders, considerations such as drug cost, availability and preferences for dosing frequency should be considered as the basis for individualising anaemia care due to lack of data for comparative differences in the clinical benefits and harms of different ESA preparations.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

A previous review identified that epoetin alpha was effective compared with placebo or no treatment in raising Hb levels without a significant reduction in GFR in patients with CKD not on dialysis (Cody 2016). Our review extends these observations to show that epoetin alpha given at higher doses for extended intervals is non‐inferior to more frequent dosing intervals. The benefits offered by the extended dosing intervals include convenience for the patients and healthcare providers and may also result in cost efficiency. This may be of benefit in countries with more limited resources and access to longer acting more costly ESAs. However the data are of low quality so that differences in efficacy and adverse effects cannot be completely excluded. We did not identify any studies which evaluated different frequencies of epoetin beta. In a single study, epoetin theta did not differ significantly from epoetin beta in haematological outcomes or adverse effects.

We only identified one study in predialysis patients comparing a biosimilar preparation of epoetin alpha (HX575 epoetin alpha, Binocrit®) in non‐dialysis patients and this study was terminated because of the development of pure red cell aplasia with neutralising antibodies (Haag‐Weber 2012). HX575 epoetin alpha and a second biosimilar of epoetin alpha (epoetin zeta, Retacrit®) received marketing authorization throughout the European Union in 2007; HX575 epoetin alpha is limited to intravenous use. Because the safety record of these compounds is limited compared with epoetin alpha and epoetin beta, the ERBP Work Group recommends stringent pharmacovigilance for biosimilars of epoetin alpha (ERBP 2009). Two clinical studies evaluating the biosimilar HX575 epoetin alpha in the USA have been completed (NCT01693029a, NCT01576341a) but the results are not yet available. Of these one (NCT01576341a) evaluated subcutaneous administration of HX575 epoetin alpha in predialysis patients in a single arm study aiming to determine efficacy, adverse effects and the incidence of anti‐epoetin antibodies. The uptake in the nephrology community of the biosimilar ESAs will ultimately depend on the balance between cost savings and residual concerns regarding safety (Mikhail 2013; Schellekens 2009).

Implications for research.

As noted in earlier ESA reviews (Hahn 2014; Strippoli 2006) the reporting of treatment effects of ESAs on potentially important patient outcomes is heterogeneous and poor, thereby limiting a good understanding of how ESA therapy affects the way patients feel and function. Currently decisions regarding different agents in clinical practice are dictated by physician and patient preference, drug cost and availability since we have inconclusive evidence of the effects of different short‐acting ESAs or of different frequencies of ESA administration on survival and quality of life. Data regarding effectiveness and safety when treating children with ESAs remains limited.

Therefore additional large, well designed, randomised studies are required in the following areas to compare larger doses of the shorter acting ESAs including new biosimilars of epoetin alpha administered less frequently with more frequent dosing in both children and adults with CKD not on dialysis. These studies should include patient‐centred outcomes including all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, and quality of life assessment. Estimates of patient and carer satisfaction related to different frequencies of administration should be included. Studies of cost‐effectiveness of different frequencies of administration should also be undertaken.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant editorial office for their assistance with this review. We would also like to thank the referees for their feedback and advice during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Epoetin alpha every 2 weeks versus weekly.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in haemoglobin level | 4 | 785 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.33, ‐0.07] |

| 2 Number reaching target haemoglobin | 4 | 798 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.93, 0.99] |

| 3 Number of deaths | 4 | 838 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.38, 2.07] |

| 4 Adverse events | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 RBC transfusions | 3 | 580 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.71, 3.45] |

| 4.2 Hypertension | 4 | 838 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.55, 1.32] |

| 4.3 Thrombovascular events | 4 | 838 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.67, 3.00] |

| 4.4 Adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy | 1 | 258 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.20, 4.79] |