Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Falls are a major healthcare concern in individuals with Alzheimer Disease (AD) and their caregivers. Vestibular impairment is a known risk factor for falls, and individuals with AD have been shown to have an increased prevalence of vestibular loss compared to age-matched controls. Vestibular physical therapy (VPT) is effective in improving balance and reducing fall risk in cognitively-intact persons with vestibular impairment. However, the effectiveness of VPT in improving balance and reducing falls in individuals with AD who have vestibular loss has never been explored.

Summary of Key Points:

In this article, we apply prevailing ideas about rehabilitation and motor learning in individuals with cognitive impairment (IwCI) to VPT.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice:

We propose a modification of current evidence-based VPT protocols for IwCI using the Strength-Based theoretical framework that emphasizes the motor learning abilities of IwCI. Additionally, we highlight the importance of establishing an excellent rapport with IwCI, and present key strategies for optimizing the therapeutic relationship. In ongoing work, we are assessing the efficacy of this modified VPT protocol in IwCI to improve balance and reduce falls.

Background:

By the year 2050, it is projected that approximately 14 million Americans will be living with Alzheimer Disease (AD).1 Individuals with AD have increased falls compared to cognitively intact older adults.2,3 Falls for patients with AD are devastating with increased rates of hip fracture, caregiver burden, and mortality compared to persons without AD.4 Fall prevention is recommended for patients with AD and exercise programs have shown capability of improving balance and reducing fall risk for patients with AD.5–8

Vestibular loss is known to occur with healthy aging.9,10 Recent evidence indicates that patients with AD have an increased prevalence of vestibular loss compared to age-matched controls.11 The mechanism explaining increased vestibular loss in AD is unknown, but given that the vestibular system has inputs to the hippocampus, the temporo-parietal junction, insular cortex, and the anterior dorsal thalamus, which are degraded in AD, a causal relationship is speculated.12 Vestibular information conveyed to cortical centers is involved in spatial cognitive skills such as spatial memory and spatial navigation, which are often impaired in AD.13,14 Vestibular physical therapy (VPT) is effective in improving balance and reducing fall risk in individuals with vestibular loss including older adults.15–17 Although half of individuals with mild-moderate AD have vestibular loss11, VPT is typically not offered to patients with AD. Underdiagnosis of vestibular loss and assumptions that cognitive impairment (CI) will prevent motor learning and limit compliance to therapy may deter rehabilitation efforts.

In this article, we propose that VPT can be successfully delivered to patients with AD and the broader population of individuals with cognitive impairment (IwCI), by using rehabilitation and motor learning strategies that are optimally effective in this population. Of note, IwCI includes individuals with mild cognitive impairment, as well as individuals with both AD and non-AD related dementia (e.g. vascular dementia). We adapt the Strength-Based theoretical model, which leverages an IwCI’s abilities, and present a comprehensive framework within which to deliver VPT to this population. Additionally, we highlight the importance of establishing an excellent therapeutic relationship with the patient. We present nine key strategies to optimize communication and engagement. The goal of this article is to provide a theoretical and practical guide to modify VPT to enhance active participation and effectiveness for IwCI.

A clinical practice guideline (CPG) for VPT for peripheral vestibular hypofunction has been published by the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section15. Gaze stabilization, habituation, balance, and walking for endurance are presented in the CPG as the four core exercise components of VPT. The CPG does not address CI and we determined that different strategies might be needed for each of the four core interventions proposed within the CPG.

We used principles of the Strength-Based theoretical model to modify interventions recommended in the VPT CPG. The Strength-Based Approach was initially developed by social workers for use in individuals with mental illness with the intent to emphasize each individual’s strengths instead of focusing on addressing the pathology.18 The Strength-Based Approach focuses on an individual’s unique skills, preferences, and available support resources to promote resilience during the training process.19,20 The Strength-Based Approach has been successfully applied in a motor learning context. A recent study demonstrated that a functional exercise program using this framework improved strength, balance, and gait speed outcomes in individuals with dementia.5 We apply the Strength-Based model to guide therapists in recognizing, understanding, and exploiting the motor learning and relationship capabilities of IwCI in the context of VPT.

Implications for Practice:

Strategies to enhance motor learning in vestibular physical therapy for cognitive impairment are provided in Table 1 with clinical examples of how the typical exercise components of VPT (gaze stabilization, balance, habituation, and walking for endurance) might be modified and considered prior to, during, and following VPT.

Table 1.

Modifications to enhance motor learning during vestibular physical therapy in individuals with cognitive impairment

| Timing of motor learning strategy | Strategy / Modification | Examples of integration into components of vestibular physical therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-practice | Specificity of training that mimics real-life environment25,26,41 |

Gaze stabilization: • Exercises can be started in environments with few or no distractions (e.g., plain background, no visual contrast, no noise), with a goal of progressing to more real-life environments such as virtual simulations (e.g., YouTube videos) and training in meaningful environments (e.g., grocery store, church). All components of training: • Utilize in-home training when possible. • Wear shoes that are typically worn. |

| Consider use of perceptual and sensory priming to add meaning and familiarity39,42,43 |

All components of training: • Consider integration of meaningful / comforting environmental sensory cues in the training environment (e.g., auditory [calm music], olfactory [pleasant smells]). • Incorporate music to enhance mood / arousal (may promote attention / memory). • Use personally relevant songs. • Deliberately select musical beat to reflect desired cadence of activity (e.g., head movements during gaze stabilization, gait cadence). |

|

| Within-practice | Use procedural / implicit learning that promotes “learning by doing” and incorporates exercises into salient functional tasks21,25,26,39 |

Gaze stabilization: • Use a meaningful gaze fixation target (e.g., photograph of family or pet); image that brings joy (e.g., sports team logo, beach or mountain scene, favorite food); or the beginning letter of their name (“B” for Bob). • Instruction to nod head “yes” to elicit vertical head turns or “no” to elicit horizontal head turns; associate “yes” with a target that has a positive association (e.g., favorite sports team logo) and “no” with negative association (e.g., rival sports team logo). Balance: • Complete activities that the patient typically performs in which balance is challenged (e.g., walk on uneven terrain to get mail from mailbox, drop a letter and have patient pick it up from the ground, donning/doffing shoes and jackets, light cleaning within home, and meal preparation tasks). Habituation: • Put exercises in context of salient functional tasks (e.g., repeatedly: getting into/out of bed; picking up shoe from the floor; reaching overhead to put dishes away; turning and reaching to retrieve an apple). Walking for endurance: • Walk in familiar and safe environments (e.g., grocery store or shopping mall with family member). |

| Utilize errorless learning that minimizes mistakes made by patient27–29 |

Gaze stabilization: • If the patient is unable to keep their gaze fixed on the target, use consistent phrasing that is brief and rhythmic (e.g., “eyes here”; “nod yes”); or mnemonics (e.g., “eyes on the prize”). The therapist can also shake the target briefly (2–3 second small amplitude) to draw attention to where gaze should be. • If the patient has difficulty maintaining head movement with cues, provide physical guidance of head movements. Balance, Habituation, & Walking for endurance: • Provide demonstration and / or tactile guidance of the desired task. • Use spaced retrieval feedback (e.g., increased time between cues for correct performance and decreased time between cues for incorrect performance). |

|

| Utilize whole task practice when possible26,40 |

Balance, Habituation, & Walking for endurance: • Train in context of entire task (e.g., avoid breaking gait cycle down into parts). • If breaking down task is required (e.g. transfer training), put components back into context of full task with multiple repetitions before ending session. |

|

| Practice with appropriate level of challenge and intensity5–8,44 |

All components of training: • Be mindful that therapists routinely under-challenge older adults; consider using visual scale to identify patient’s perception of exercise difficulty if mental status allows. • Monitor patient for observable signs of challenge (e.g., eye squinting or closure; facial tension; neck/body guarding) as a prompt to offer rest. • Observe patient for the need of “mental breaks”, especially with gaze stabilization and habituation training tasks. |

|

| Post-practice | Encourage psychosocial support35,36 | • Caregivers should be educated on the motor learning strategies to reinforce with patient during completion of home exercise program. • Patients may lack safety awareness37,38; caregiver should be educated on environmental set-up and guarding techniques to keep patient safe. |

Pre-practice motor learning strategies

Using specificity of training that mimics real-life environments is important for IwCI as it can foster patient comfort within their own home and add salience to the training. Simulated environments could be considered if this is not feasible. Perceptual and sensory priming may add meaning and familiarity to VPT.

Within-practice motor learning strategies

The use of procedural / implicit learning rather than declarative / explicit learning, supports the concept of “learning by doing.” Clinicians should strategically design tasks and environments that elicit the desired motor response in IwCI, whose procedural memory systems tend to be better preserved than their declarative memory systems.21–23 Salient functional tasks are known to promote learning in general,24 and the use of meaningful tasks for IwCI is particularly effective25,26. Errorless learning has been shown to be effective in training IwCI to complete meaningful daily tasks.27–29 Anticipating and minimizing errors with the effective use of cues and gestures is important to avoid errant motor strategies that may be unsafe, ineffective, or inefficient. Extrapolating from the cognitive rehabilitation literature,27,30 we pose that avoiding errors is important, because when an (IwCI) practices an activity in a flawed manner, the faulty strategy may become their default motor plan for the task

Completing whole task training may minimize patient confusion and optimize engagement with meaningful tasks. For balance and endurance tasks, the level of challenge and intensity should not be under-dosed, while during the gaze stabilization and habituation tasks we believe it might be important not to over tax the patient. Increased rest breaks may be necessary for IwCI during gaze stabilization and habituation exercise because of mental fatigue that often accompanies vestibular disorders.31 Visual scales of balance challenge and intensity are being investigated in cognitively intact persons and whether this would be appropriate for persons with AD remains to be investigated. During VPT the clinician should observe for signs and symptoms of mental fatigue (e.g., eye squinting or closure; facial tension; neck/body guarding). Previous neurorehabilitation investigations have yielded successful results using the challenge point framework (CPF), which manipulates practice conditions to modify task difficulty by considering the skill of the learner and the difficulty of the task.32,33 Improvements in walking balance for people with stroke and in goal-directed upper extremity movements in people with Parkinson Disease resulted following interventions that incorporated CPF.33,34

Post-practice motor learning strategy

Psychosocial support is associated with increased engagement and participation for the IwCI.35,36 Encouraging caregivers to reinforce motor learning strategies during functional mobility may be useful. Caregivers should also be educated on strategies to prevent falls given safety awareness deficits in IwCI.37,38 Additionally, the caregiver should be educated on the possibility that the gaze stabilization and habituation exercises may provoke adverse symptoms (dizziness, nausea, headache). Caregivers should be mindful of verbal reports and non-verbal signs of discomfort and/or agitation so that appropriate modifications can be made.39–44

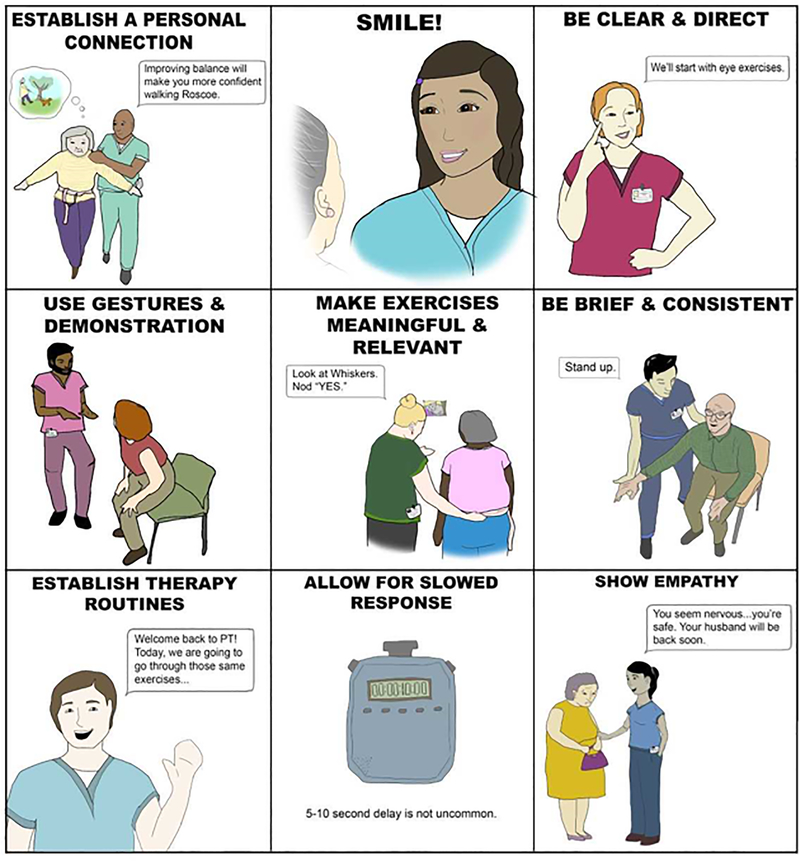

Optimizing the therapeutic relationship is known to be critical when working with IwCI in order to improve outcomes.45 Strategies to optimize the relationship have been previously proposed; we have distilled this literature into nine core communication and relationship strategies that should be incorporated into VPT (Figure 1). These include: establishing a personal connection, showing empathy, smiling, being clear and direct, using gestures, cueing with brevity and consistency, allowing for slowed response, making exercises meaningful and relevant, and establishing therapy routines.46

Figure 1.

Core communication and relationship strategies to incorporate into vestibular physical therapy: A quick reference guide for clinicians.

To establish a personal connection, the clinician should invest time in learning the patient’s personal and social history.47 During the therapy session, the clinician can refer to the patient’s family members or pets by name and use conversation that draws upon the uniqueness of the patient (e.g., “I know how much you love the symphony. I watched a documentary on Mozart this weekend!”). Showing empathy will further build rapport and develop trust with the patient (e.g., verbally acknowledge fearful or distressed situations, provide reassurance, and / or make necessary modifications).48,49 When speaking to the patient, the clinician should position themselves at eye level, smile during conversation, and use clear and direct commands (e.g., speak slowly, maintain eye contact; and keep it simple).50,51 Elevation of intonation at the end of a sentence transforms a statement or command into a question in the mind of the IwCI. This can be confusing. A confident and direct tone eliminates this confusion. Use of gestures and demonstrations (e.g., slow hand movement downward to illustrate controlled eccentric lowering for stand to sit) may help in eliciting a desired activity52,53.

Verbal cues should be brief (e.g., use as few words as needed) and consistent (e.g., “nod yes” used throughout 30 second gaze stabilization exercise).54 The IwCI may require increased response time to complete the motor task following the command.55 The feedback provided to the patient should be encouraging and motivating (e.g., “great work!”, “you can do it!”).

To make exercises meaningful and relevant the clinician should incorporate salient and joyful topics into the VPT session (e.g., pictures of pets, family members, or sports logos for gaze stabilization targets). The use of external motivation for rewards for the patient, such as a visual representation reflecting their progress or participation during VPT (e.g., chart recognizing achievements, stickers to represent success) may be motivating.56 PT’s should utilize positive social reinforcement, as this has been shown to encourage IwCI,57 while being conscious of not infantilizing the patient.58

It is important to establish consistent therapy routines whereby the patient works with the same therapist, at the same location, and at the same time of day.59 Learning in IwCI is facilitated by the use of constant (versus variable) and blocked (versus random) practice schedules.26,41 The VPT session should occur at a time when the patient is rested to enhance participation.

Summary:

In this article, we propose a theoretical and practical guide for VPT in IwCI which integrates a Strength-Based Approach to facilitate motor learning and establishing a strong therapeutic relationship. Studies suggest that IwCI have the capability to make functional improvement with rehabilitation efforts60–62, and have the ability to develop motor memory of tasks26, even in the absence of cognitive memory of training and/or practice. Additionally, a recent study reported that among patients with unilateral vestibular hypofunction, even those with mild CI benefitted from VPT.63

The modifications presented are based on training principles that have effectively induced motor learning in IwCI; however, further studies are need to evaluate the efficacy of this theoretically-based modification of VPT on balance and fall outcomes, as well as self-perceived outcomes related to balance confidence, dizziness handicap, and motion sensitivity in IwCI.64

Vestibular loss occurs with normal aging and VPT is known to effectively improve balance and decrease fall risk in older adults with vestibular deficits. Vestibular loss appears to be more prevalent in older adults with AD, though VPT is typically not recommended for this population. VPT might be an important way to improve balance, decrease falls, decrease health care costs, and decrease caregiver burden for IwCI. We provide a theoretical and practical guide for VPT in IwCI, and in ongoing work are evaluating the efficacy of this modified VPT protocol in IwCI.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding:

Dr. Yuri Agrawal is receiving grant funding from NIA (#RO1 AG057667), NIH/NIDCD (#R03 DC015583), and NIH/NIDCD (#K23 DC013056). For the remaining authors none were declared.

This work is not under review elsewhere and has not been previously published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’sAssociation. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2018; https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 2.Allan LM, Ballard CG, Rowan EN, Kenny RA. Incidence and prediction of falls in dementia: a prospective study in older people. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti M, Speechley M, Ginter S. Risk Factors for Falls among Elderly Persons Living in the Community. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988(319):1701–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker NL, Cook MN, Arrighi HM, Bullock R. Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer’s disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988–2007. Age Ageing. 2011;40(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson N, Judge KS, Gerhart H. Improved Functional Performance in Individuals With Dementia After a Moderate-Intensity Home-Based Exercise Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ries JD, Hutson J, Maralit LA, Brown MB. Group Balance Training Specifically Designed for Individuals With Alzheimer Disease: Impact on Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up and Go, Gait Speed, and Mini-Mental Status Examination. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38(4):183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telenius EW, Engedal K, Bergland A. Long-term effects of a 12 weeks high-intensity functional exercise program on physical function and mental health in nursing home residents with dementia: a single blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toots A, Littbrand H, Lindelof N, et al. Effects of a High-Intensity Functional Exercise Program on Dependence in Activities of Daily Living and Balance in Older Adults with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2004. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169(10):938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal Y, Zuniga MG, Davalos-Bichara M, et al. Decline in semicircular canal and otolith function with age. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(5):832–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harun A, Oh ES, Bigelow RT, Studenski S, Agrawal Y. Vestibular Impairment in Dementia. Otology & Neurotology. 2016;37(8):1137–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hitier M, Besnard S, Smith PF. Vestibular pathways involved in cognition. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoder RM, Taube JS. The vestibular contribution to the head direction signal and navigation. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2014;8:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigelow RT, Agrawal Y. Vestibular involvement in cognition: Visuospatial ability, attention, executive function, and memory. J Vestib Res. 2015;25(2):73–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall CD, Herdman SJ, Whitney SL, et al. Vestibular Rehabilitation for Peripheral Vestibular Hypofunction: An Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline: FROM THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION NEUROLOGY SECTION. Journal of neurologic physical therapy : JNPT. 2016;40(2):124–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C. Exercise for improving balance in older people. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011(11):Cd004963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanenburg J, Wild K, Straumann D, de Bruin ED. Exergaming in a Moving Virtual World to Train Vestibular Functions and Gait; a Proof-of-Concept-Study With Older Adults. Frontiers in physiology. 2018;9:988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rapp C The Strengths Model: Case Management with People Suffering from Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Judge KS, Yarry SJ, Orsulic-Jeras S. Acceptability and feasibility results of a strength-based skills training program for dementia caregiving dyads. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(3):408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krabbenborg MA, Boersma SN, Wolf JR. A strengths based method for homeless youth: effectiveness and fidelity of Houvast. BMC public health. 2013;13:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidoni ED, Boyd LA. Achieving enlightenment: what do we know about the implicit learning system and its interaction with explicit knowledge? Journal of neurologic physical therapy : JNPT. 2007;31(3):145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jelicic M, Bonebakker AE, Bonke B. Implicit memory performance of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a brief review. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7(3):385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Squire LR, Wixted JT. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annual review of neuroscience. 2011;34:259–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rumbaugh DM, King JE, Beran MJ, Washburn DA, Gould KL. A Salience Theory of Learning and Behavior: With Perspectives on Neurobiology and Cognition. International Journal of Primatology. 2007;28(5):973–996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson J, Wessel J. Strategies for retraining functional movement in persons with Alzheimer disease: a review. Physiotherapy Canada 2002;54(4):274–280. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Halteren-van Tilborg IA, Scherder EJ, Hulstijn W. Motor-skill learning in Alzheimer’s disease: a review with an eye to the clinical practice. Neuropsychology review. 2007;17(3):203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Werd MM, Boelen D, Rikkert MG, Kessels RP. Errorless learning of everyday tasks in people with dementia. Clinical interventions in aging. 2013;8:1177–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessels RP, de Haan EH. Implicit learning in memory rehabilitation: a meta-analysis on errorless learning and vanishing cues methods. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2003;25(6):805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Liu KP. The use of errorless learning strategies for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review. International journal of rehabilitation research Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation. 2012;35(4):292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middleton EL, Schwartz MF. Errorless learning in cognitive rehabilitation: a critical review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2012;22(2):138–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanes D, McCollum G. Cognitive-vestibular interactions: A review of patient difficulties and possible mechanisms. Journal of vestibular research. 2006;16:75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guadagnoli MA, Lee TD. Challenge point: a framework for conceptualizing the effects of various practice conditions in motor learning. Journal of motor behavior. 2004;36(2):212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollock CL, Boyd LA, Hunt MA, Garland SJ. Use of the challenge point framework to guide motor learning of stepping reactions for improved balance control in people with stroke: a case series. Phys Ther. 2014;94(4):562–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onla-or S, Winstein CJ. Determining the optimal challenge point for motor skill learning in adults with moderately severe Parkinson’s disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(4):385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robison J, Curry L, Gruman C, Porter M, Henderson CR Jr., Pillemer K Partners in caregiving in a special care environment: cooperative communication between staff and families on dementia units. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobbs D, Munn J, Zimmerman S, et al. Characteristics associated with lower activity involvement in long-term care residents with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2005;45 Spec No 1(1):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotter VT. The burden of dementia. The American journal of managed care. 2007;13 Suppl 8:S193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tilly J, Reed P. Falls, Wandering, and Physical Restraints: A Review of Interventions for Individuals with Dementia in Assisted Living and Nursing Homes. Alzheimer’s care today. 2008;9(1):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison BE, Son GR, Kim J, Whall AL. Preserved implicit memory in dementia: a potential model for care. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2007;22(4):286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner C, Wiloth S, Lemke NC, et al. People with Dementia Can Learn Compensatory Movement Maneuvers for the Sit-to-Stand Task: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2017;60(1):107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dick MB, Hsieh S, Dick-Muehlke C, Davis DS, Cotman CW. The variability of practice hypothesis in motor learning: does it apply to Alzheimer’s disease? Brain and cognition. 2000;44(3):470–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moussard A, Bigand E, Belleville S, Peretz I. Music as a mnemonic to learn gesture sequences in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarkamo T Music for the ageing brain: Cognitive, emotional, social, and neural benefits of musical leisure activities in stroke and dementia. Dementia (London, England) 2018;17(6):670–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Littbrand H, Rosendahl E, Lindelof N, Lundin-Olsson L, Gustafson Y, Nyberg L. A high-intensity functional weight-bearing exercise program for older people dependent in activities of daily living and living in residential care facilities: evaluation of the applicability with focus on cognitive function. Phys Ther. 2006;86(4):489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams CL, Tappen RM. Can we create a therapeutic relationship with nursing home residents in the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services. 1999;37(3):28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ries J Rehabilitation for Individuals with Dementia: Facilitating Success. Current Geriatrics Reports. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clarke A, Jane Hanson E, Ross H. Seeing the person behind the patient: enhancing the care of older people using a biographical approach. Journal of clinical nursing. 2003;12(5):697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haak NJ. Maintaining connections: understanding communication from the perspective of persons with dementia. (Communication). Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2002;3(2):116. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heliker D Story sharing: restoring the reciprocity of caring in long-term care. Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services. 2007;45(7):20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berg JS, Dischler J, Wagner DJ, Raia JJ, Palmer-Shevlin N. Medication compliance: a healthcare problem. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 1993;27(9 Suppl):S1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1993;73(11):771–782; discussion 783–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pashek GV, DiVenere E. Auditory Comprehension in Alzheimer Disease: Influences of Gesture and Speech Rate. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2006;14(3):143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Josephsson S, Bäckman L, Borell L, et al. Supporting everyday activities in Dementia: an intervention study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1993;8(5):395. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Small JA, Gutman G. Recommended and reported use of communication strategies in Alzheimer caregiving. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2002;16(4):270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clare L, Woods RT. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2004;14(4):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robison JI, Rogers MA. Adherence to exercise programmes. Recommendations. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 1994;17(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perry DC, Sturm VE, Wood KA, Miller BL, Kramer JH. Divergent processing of monetary and social reward in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2015;29(2):161–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jongsma K, Schweda M. Return to childhood? Against the infantilization of people with dementia. Bioethics. 2018;32(7):414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith ER, Broughton M, Baker R, et al. Memory and communication support in dementia: research-based strategies for caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(2):256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toulotte C, Fabre C, Dangremont B, Lensel G, Thevenon A. Effects of physical training on the physical capacity of frail, demented patients with a history of falling: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2003;32(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A, et al. Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burton E, Cavalheri V, Adams R, et al. Effectiveness of exercise programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical interventions in aging. 2015;10:421–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Micarelli A, Viziano A, Bruno E, Micarelli E, Augimeri I, Alessandrini M. Gradient impact of cognitive decline in unilateral vestibular hypofunction after rehabilitation: preliminary findings. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2018;275(10):2457–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skidmore ER. Training to Optimize Learning after Traumatic Brain Injury. Current physical medicine and rehabilitation reports. 2015;3(2):99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]