Abstract

The survival of human beings is inseparable from microbes. More and more studies have proved that microbes can affect human physiological processes in various aspects and are closely related to some human diseases. In this paper, based on known microbe-disease associations, a bidirectional weighted network was constructed by integrating the schemes of normalized Gaussian interactions and bidirectional recommendations firstly. And then, based on the newly constructed bidirectional network, a computational model called BWNMHMDA was developed to predict potential relationships between microbes and diseases. Finally, in order to evaluate the superiority of the new prediction model BWNMHMDA, the framework of LOOCV and 5-fold cross validation were implemented, and simulation results indicated that BWNMHMDA could achieve reliable AUCs of 0.9127 and 0.8967 ± 0.0027 in these two different frameworks respectively, which is outperformed some state-of-the-art methods. Moreover, case studies of asthma, colorectal carcinoma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were implemented to further estimate the performance of BWNMHMDA. Experimental results showed that there are 10, 9, and 8 out of the top 10 predicted microbes having been confirmed by related literature in these three kinds of case studies separately, which also demonstrated that our new model BWNMHMDA could achieve satisfying prediction performance.

Keywords: microbe, disease, association prediction, bidirectional weighted network, bidirectional recommendations

1. Introduction

Microorganisms are small in shape, simple in structure, and closely related to human beings. The development of modern bioinformatics and sequencing technologies has led to the study of microorganisms living in the ocean, soil, human body, and other places by the scientific community (Gilbert and Dupont, 2011). Among them, eukaryotes, archea, bacteria, and viruses are human-related microorganisms, collectively known as human microbiota (Turnbaugh et al., 2007; Methé et al., 2012). Microorganisms exist in large quantities in humans, nearly 10 times that of human cells (Sender et al., 2016). According to recent researches, there are nearly 1,014 bacterial cells in the human body with more than 10,000 kinds of microorganisms, which provide different degrees of metabolic activity (Bhavsar et al., 2007; Turnbaugh et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2016). Parasitic in the human body, these microbes do not harm the host, but are interdependent with human beings and are called “forgotten organs” (Quigley, 2013). With the continuous advancement of high-throughput sequencing technology and analytical systems, people have gradually realized the importance of microorganisms in the investigation. According to the survey, microbes participate in a series of human life activities, such as harvesting and storing energy, regulating the immune system, protecting the human body from foreign microorganisms and pathogens, participating in the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates and promoting metabolism (Guarner and Malagelada, 2003; Gill et al., 2006). Therefore, once the microbes become “unhealthy” in the human body, the human body will receive their effects leading to physiological disorders and even illness.

Humans and commensal microbiota have formed a close symbiotic relationship in the process of continuous evolution. The microbiota will be affected by the host and living environment. It has been reported that diet affects the structure and activity of human intestinal microbes (Duncan et al., 2006; Ley et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2010; David et al., 2013) For example, a short-term high-fat, low-fiber diet can cause changes in microbial structure, while long-term diets are associated with alternative intestinal status (Wu et al., 2011). Besides, smoking (Mason et al., 2014), age, and genes are also factors influencing the composition of the microbiota (Gill et al., 2006). Therefore, once the human body and the microbiota cannot coexist harmoniously, it may cause various problems in the human body. Based on the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequence and classification spectrum (Thompson et al., 2014; Jesmok et al., 2016), researchers have found that a large number of human diseases are closely related to human microorganisms, including cancer (Moore and Moore, 1995), diabetes (Wen et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2012), Obesity (Ley et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009), kidney stones (Hoppe et al., 2011), and other thorny diseases. For example, Huang (2013) pointed out that microbes can affect allergic sensitization and asthma development in susceptible individuals, and early intervention in promoting “healthy” human microbiome constitution may have the potential and benefits of preventing asthma. Hence, some researchers are proposing to promote the induction of sensitized immune response through the research and development of probiotic-based therapies (Rauch and Lynch, 2012).

Disease-related microbes are obtaining more and more attention from humans, and researchers have carried out some large-scale sequencing projects, including the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) (Turnbaugh et al., 2007) and the Earth Microbiome Project (EMP) (Gilbert et al., 2010). Moreover, some databases (Matsumoto et al., 2005; Faith et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Mikaelyan et al., 2015) for categorizing and managing disease-related microbial information have also been developed. For instance, Ma et al. collected and compiled 483 pairs of human microbe-disease associations by collecting published literature and established the Human Microbe-Disease Association Database (HMDAD) (Ma et al., 2016). These accurate data provide the possibility to predict human microbes and diseases. Nowadays, most microbial community identification methods are independent culture methods and quantitative methods. Their shortcomings are obvious and often take a lot of time and efforts. Previously, many researchers have studied the potential correlation predictions of diseases and other biological categories (such as miRNA Chen and Yan, 2014; You et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018b,c and lncRNA Chen and Yan, 2013; Chen et al., 2016b, 2018a; Yu et al., 2018; Xuan et al., 2019), and simultaneously, Drug-target interaction prediction (Chen et al., 2012) and the study of synergistic drug combinations prediction (Chen et al., 2016a) has also achieved satisfying successes. And among existing state-of-the-art methods, the computational model of KATZ measure for human microbe-disease association prediction (KATZHMDA) (Chen et al., 2017) proposed by Chen et al. is one of their prominent representatives, which not only achieved excellent prediction performance but also initialized the research field of the microbe-disease prediction. Later, Huang Z.A. et al. (2017) proposed a Path-Based computational model of Human Microbe-Disease Association prediction (PBHMDA), which adopts a special depth-first search algorithm to traverse all possible paths between microbes and diseases in heterogeneous networks to obtain the prediction score of each microbe-disease pair. Wang et al. (2017) proposed a semi-supervised learning-based computational model of Laplacian Regularized Least Squares for Human Microbe-Disease Association prediction (LRLSHMDA), which utilizes Laplace's regular least squares classification combined with topological information of the known microbe-disease association network to train an optimal classifier. Huang Y.A. et al. (2017) developed a method based on Neighbor and Graph-based combined recommendation model for Human Microbe-Disease Association prediction (NGRHMDA) by combining two recommendation models as a neighbor-based collaborative filtering model and a topology-based model. Peng et al. (2018) developed a model of Adaptive Boosting for Human Microbe-Disease Association prediction (ABHMDA), which reveals the associations between disease and microbe by using a strong classifier to calculate the probability of disease-microbe pair association. In addition, Shen et al. (2018) proposed Bi-Random Walk based on Multiple Path (BiRWMP) to predict microbe-disease associations. Shi et al. (2018) propose BMCMDA based on Binary Matrix Completion to predict potential microbe-disease associations.

In this paper, inspired by the performance of KATZHMDA, we proposed a new microbe-disease association prediction model called BWNMHMDA. A novel two-way network was constructed firstly based on the known microbe-disease associations downloaded from the HMDAD database, and then, the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity were adopted to assign weights to every node and edge in a newly constructed two-way network. Hence, a bidirectional weighted network was further obtained by implementing two newly developed bidirectional recommendation measures. Finally, based on the newly constructed bidirectional weighted network, a computational model was constructed to infer potential microbe-disease associations. In order to estimate the prediction performances of BWNMHMDA, the framework of leave-one-out cross validation (LOOCV) and 5-fold cross validation(5-Fold CV) were implemented, and simulation results indicated that BWNMHMDA could achieve reliable AUCs of 0.9127 in LOOCV and 0.8967 ± 0.0027 in 5-Fold CV, respectively, which is much better than that of state-of-the-art methods. And moreover, in case studies of asthma, colorectal carcinoma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the simulation results also demonstrated the effective predictability of BWNMHMDA.

2. Material

Since known microbe-disease associations were considered in our prediction model BWNMHMDA, we firstly downloaded known microbe-disease associations from the Human Microbe-Disease Association database (HMDAD) (Ma et al., 2016), and as a result, after getting rid of the redundant associations, a total of 450 different microbe-disease associations including 39 human diseases and 292 microbes were collected from 61 public publications. Hence, a 39 × 292 dimensional adjacency matrix A is obtained finally, which will be utilized as the data source of our prediction model BWNMHMDA. And additionally, in the adjacency matrix A, the value of A[i][j] is set to 1 if there is a known association between the ith disease and the jth microbe, otherwise, A[i][j] is set to 0.

3. Methods

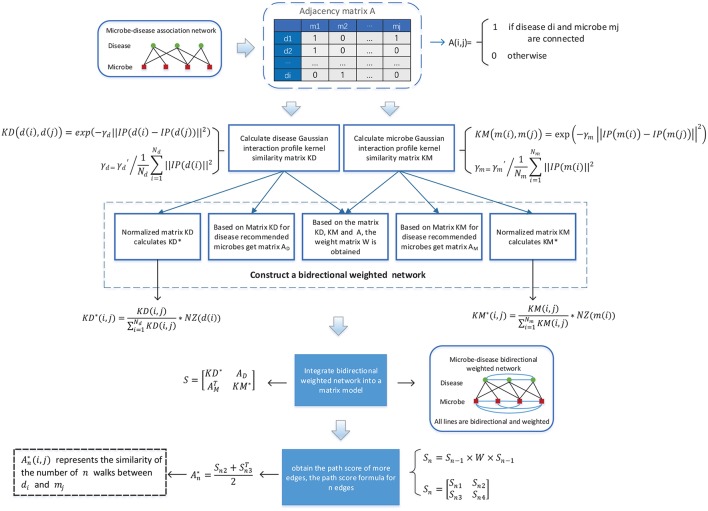

As illustrated in the following Figure 1, in BWNMHMDA, three kinds of association networks such as the known microbe-disease association network, the microbe similarity network and the diseases similarity network will be constructed firstly. And then, through integrating these three kinds of association networks, an integrated microbe-disease heterogeneous association network will be obtained. Moreover, through adopting the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity to assign weights to every node and edge in the integrated microbe-disease heterogeneous association network, a bidirectional weighted microbe-disease association network can be further obtained. Hence, based on the newly constructed bidirectional weighted association network, a novel computation model can be developed to infer potential microbe-disease associations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of BWNMHMDA.

3.1. Microbes Similarity Based on Gaussian Interaction Profile Kernel Similarity

It is obviously reasonable that for any two microbes if there are more common human diseases proved to be related to them, may tend to share more functional similarities potentially. Hence, in the known microbe-disease association network, we will first adopt the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity to construct a microbe similarity network according to the following formula (1):

| (1) |

Where m(i) and m(j) represent the ith and jth microbes respectively in the adjacency matrix A, IP[m(i)] and IP[m(j)] denote ith and jth column, respectively, in the adjacency matrix A, and ||X|| represents the norm of the vector X. Moreover, the parameter γm can be obtained as follows:

| (2) |

Here, is a parameter utilized to control the Gaussian kernel bandwidth, and according to the related studies (van Laarhoven et al., 2011), will be set to 1 in BWNMHMDA. In addition, the parameter Nm indicates the total number of microbes collected from the HMDAD database, and it is obvious that there is Nm=292.

Thereafter, according to the above formula (1), it is easy to see that a microbe similarity matrix KM can be calculated, specifically, and for simplicity, we will replace KM[m(i), m(j)] with KM(i, j) in the following sections.

3.2. Diseases Similarity Based on Gaussian Interaction Profile Kernel Similarity

In a similar way, through adopting the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity, we can further construct a disease similarity network according to the following formula (3):

| (3) |

Here, the parameter γd can be obtained as follows:

| (4) |

Here, is a parameter utilized to control the Gaussian kernel bandwidth, and according to the related studies (van Laarhoven et al., 2011), will be also set to 1. In addition, the parameter Nd indicates the total number of diseases collected from the HMDAD database, and it is obvious that there is Nd=39.

Thereafter, according to the above formula (3), it is easy to see that a disease similarity matrix KD can be calculated, specifically, and for simplicity, we will replace KD[d(i), d(j)] with KD(i, j) in the following sections.

3.3. Data Pre-processing

Based on the newly constructed microbe similarity network and disease similarity network, after integrating the known microbe-disease associations with these two similarity networks, it is obvious that we can construct an integrated heterogeneous microbe-disease association network consisting of two kinds of nodes such as microbe and disease, and three kinds of edges such as the edges between microbes, the edges between microbes and diseases, and the edges between diseases. And furthermore, based on the integrated heterogeneous microbe-disease association network, we can obtain a (39+292) × (39+292) dimensional matrix P as follows:

| (5) |

Moreover, in the integrated heterogeneous microbe-disease association network, if a microbe (or disease) node has more edges connecting with disease (or microbe) nodes, then it is obvious that the microbe (or disease) node will have less significance to those disease (or microbe) nodes connecting with it, which means that the microbe (or disease) node shall be assigned smaller weights than those microbe (or disease) nodes with fewer edges. Hence, based on above formula (5), we can further obtain a (39+292) × (39+292) dimensional diagonal matrix W to represent the weight value of each node in the heterogeneous network as follows:

| (6) |

In addition, while calculating the similarity between two nodes in the heterogeneous network, there may be cases where the scores of the path consisting of three edges are larger than the scores of the path consisting of two edges. Hence, in order to avoid such kind of situation, we will normalize the weights of edges in the heterogeneous network by adopting the following formula (7) and formula (8) separately.

| (7) |

Where NZ[m(i)] denotes the number of elements with non-zero values in the ith row of the matrix KM. And based on above formula (7), it is noteworthy that the symmetric matrix KM will be changed to an asymmetric matrix KM* after the normalization. Moreover, in the heterogeneous network, KM*(i, j) represents the weight of the directed edge from the microbe node mi to the microbe node mj, while KM*(j, i) denotes the weight of the directed edge from the microbe node mj to the microbe node mi.

| (8) |

Where NZ[d(i)] denotes the number of elements with non-zero values in the ith row of the matrix KD. And based on the above formula (8), it is noteworthy that the symmetric matrix KD will as well be changed to an asymmetric matrix KD* after the normalization. Moreover, in the heterogeneous network, KD*(i, j) represents the weight of the directed edge from the disease node di to the disease node dj, while KD*(j, i) denotes the weight of the directed edge from the disease node dj to the disease node di.

Therefore, according to the above descriptions, it is obvious that we can obtain a bidirectional heterogeneous network based on the above formula (7) and formula (8).

3.4. Bidirectional Recommendation of Potential Associations

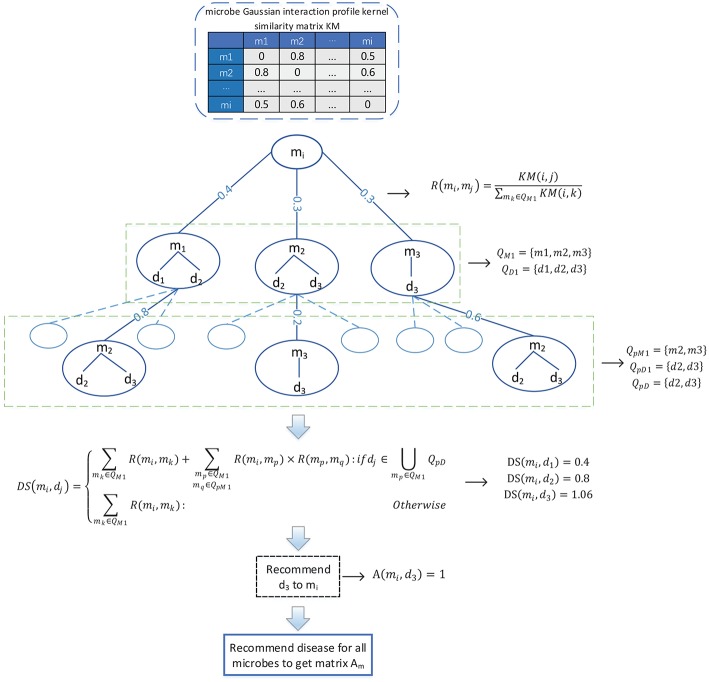

Considering that there are only 450 known associations in the adjacency matrix A, which is very sparse, therefore, in order to solve the problem of the adjacency matrix A caused by the scarcity of known associations, as illustrated in the following Figure 2, we designed a novel bidirectional recommendation model in this section based on the bidirectional heterogeneous network constructed above. And in this bidirectional recommendation model, we first designed a recommendation algorithm to recommend diseases for microbes based on the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarities between microbes as follows:

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the method utilized to recommend diseases to microbes.

(1) Firstly, for any given microbe node mi in the bidirectional heterogeneous network, let QM1 denote the set consisting of the first K microbes that are other than mi in the bidirectional heterogeneous network and most similar to mi at the same time, and considering about the time complexity, in this paper, K will be set to 3. And then, let QD1 represent the set of diseases having known associations with at least one of the microbe nodes in QM1, thereafter for any microbe node mj in QM1, we can obtain the recommendation score of mj to mi according to the following formula (9):

| (9) |

Moreover, for any given disease node dj in QD1, we can further obtain the recommendation score of dj to mi according to the following formula (10):

| (10) |

Hence, in a similar way, for any given microbe node mp in QM1, we can obtain a set QpM1 consisting of the first K microbes that are other than mp in the bidirectional heterogeneous network and most similar to mp at the same time, and then, based on the set QpM1, we can further obtain a set QpD1 consisting of diseases that have known associations with at least one of the microbe nodes in QpM1. In addition, let QpD = QD1∩QpD1, it is obvious that for any node dk in ∪mp∈QM1QpD, it shall be assigned higher recommendation score than those nodes that are in QD1 and not in ∪mp∈QM1QpD. Hence, for any given disease node dj in QD1, based on the above formula (10), we can obtain a modified recommendation score of dj to mi as follows:

| (11) |

Obviously, according to the above formula (11), for all these disease nodes in QD1, we can obtain their corresponding recommendation scores, after sorting these disease nodes according to their recommendation scores in descending order, we will finally recommend the disease node ranking first to the microbe node mi. And additionally, for the microbe node mi, supposing that the disease node that we recommended to it is dj, then we will further set the value of A(i, j) in the adjacency matrix A to 1. Consequently, through updating the adjacency matrix A as stated above, it is obvious that we can obtain a new adjacency matrix Am.

(2) Secondly, in a similar way, for any given disease node di in the bidirectional heterogeneous network, let QD2 denote the set consisting of the first K (=3) diseases that are other than di in the bidirectional heterogeneous network and most similar to di at the same time, and then, let QM2 represent the set of microbes having known associations with at least one of the disease nodes in QD2, thereafter, for any given disease node dp in QD2, we can obtain a set QpD2 consisting of the first K diseases that are other than dp in the bidirectional heterogeneous network and most similar to dp at the same time. Moreover, based on the set QpD2, we can further obtain a set QpM2 consisting of microbes that have known associations with at least one of the disease nodes in QpD2. Finally, let QpM = QM2∩QpM2, then for any given microbe node mj in QM2, we can obtain a recommendation score of mj to di as follows:

| (12) |

Here,

| (13) |

Obviously, according to the above formula (12), for all these microbe nodes in QM2, we can obtain their corresponding recommendation scores, after sorting these microbe nodes according to their recommendation scores in descending order, we will finally recommend the microbe node ranking first to the disease node di. And additionally, for the disease node di, supposing that the microbe node that we recommended to it is mj, then we will further set the value of A(j, i) in the adjacency matrix A to 1. Consequently, through updating the adjacency matrix A as stated above, it is obvious that we can obtain a new adjacency matrix Ad.

3.5. Prediction Model of BWNMHMDA

KATZ is a network-based method that can solve link prediction problems. In recent years, KATZ has been implemented successfully in many different prediction applications such as prediction of social networks (Katz, 1953), prediction of associations between gene (Yang et al., 2014) and prediction of associations between lncRNAs (Chen, 2015), etc. In 2017, Chen et al. further applied KATZ in the field of microbe-disease association prediction for the first time (Chen et al., 2017). Considering that KATZ can be utilized to calculate the similarities between nodes in heterogeneous networks, and according to the above description in section 3.3, we have built a bidirectional heterogeneous microbe-disease association network, hence, in this section, we will design a model called BWNMHMDA based on KATZ to predict potential microbe-disease associations. For constructing the prediction model, we will convert the bidirectional heterogeneous microbe-disease association network to a (39+292)*(39+292) dimensional matrix S as follows:

| (14) |

Hence, based on above formula (14), for any given disease node di and microbe node mj in the bidirectional heterogeneous microbe-disease association network, we can predict the potential similarity between them as follows:

| (15) |

Here, n is a parameter representing the number of steps between disease nodes and microbe nodes in the bidirectional heterogeneous microbe-disease association network. For n = 1, 2, 3, …, there are:

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

Specifically, in formula (16), the matrix Sn2(i, j) represents the total score of all paths with length of n from the disease di to microbe mj, and correspondingly, the matrix Sn3(j, i) represents the total score of all paths with length of n from the microbe mj to disease di. It is worth noting that since the weights of the edges in the heterogeneous network are bidirectional, we integrate Sn2 and Sn3 as formula (16). The two matrices are assigned the same weight as the final predictive score matrix .

4. Result

4.1. Effects of the Parameter n to BWNMHMDA

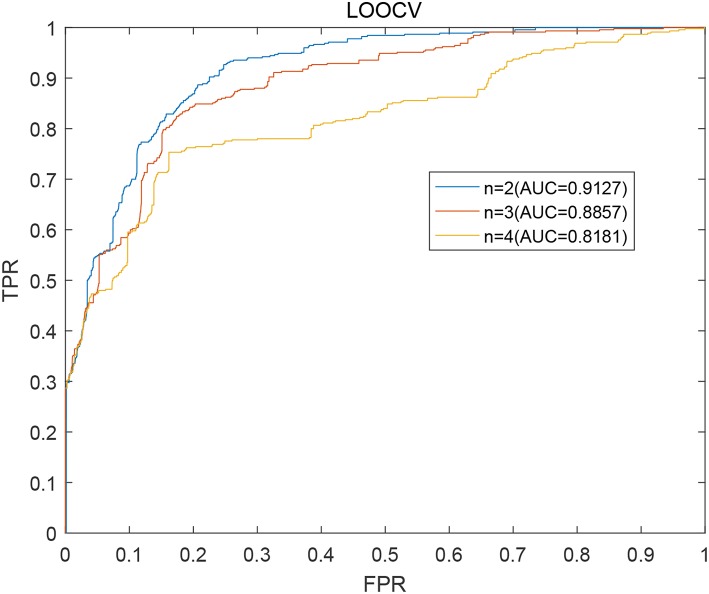

The framework of Leave-one-out cross validation (LOOCV) and 5-fold cross validation (5-Fold CV) are two kinds of common methods to evaluate model performance. While implementing LOOCV on our prediction model BWNMHMDA, each known microbe-disease association will be used as a test sample and further predicted by training the other known microbe-disease associations. Moreover, all microbe-disease pairs without known relevant evidence will be considered as candidate samples. The predicted score which obtained a higher rank than the given threshold will be considered as a successful prediction. Obviously, while setting different thresholds, the true positive rate (TPRs, sensitivity) and false positive rate (FPRs, 1-specificity) can be obtained. Here, sensitivity refers to the percentage between the number of test samples with ranks higher than the given threshold and the number of positive samples (known microbe-disease associations). Meanwhile, 1-specificity denotes the percentage of negative microbe-disease associations which obtained ranks lower than the threshold. Finally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve can be further drawn. The area under the ROC curve(AUC) can be calculated to evaluate its predictive performance, where the AUC value of 1 indicates perfect prediction perfection and the AUC value of 0.5 implies pure random prediction performance (Chen et al., 2017).

As described above, in our prediction model BWNMHMDA, the variable n in the formulas (15) is a critical parameter. Hence, we will first estimate its effect to the prediction performance of BWNMHMDA in this section. And as illustrated in Figure 3. BWNMHMDA achieved the best prediction performance while n = 2, and as the value of n sequentially increased from 2 to 4, the AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA decreased continuously, and through analysis, we found that the reason may be that the number of known microbe-disease associations is minimal in the HMDAD database, which leads that long paths in the bidirectional heterogeneous microbe-disease association network will be meaningless to the prediction performance of BWNMHMDA.

Figure 3.

AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA in LOOCV while n = 2, 3, 4 separately.

In order to further evaluate the effects of the parameter n to our prediction model, we further implemented 5-fold cross validation on BWNMHMDA, and during simulation, all known microbe-disease associations were randomly divided into five segments with almost the same size, among which, four segments were utilized for model learning, and the remaining segment were used as test samples for model evaluation. Similar to LOOCV, all microbe-disease pairs without relevant evidence would be considered as potential candidates. In order to reduce the experimental bias, we repeated our simulation based on the 5-fold cross validation 100 times, and during each time of simulation, the samples were divided randomly. Finally, as illustrated in the following Table 1, it is easy to see that BWNMHMDA could as well achieve the best prediction performance while n=2, and moreover, as the value of n sequentially increased from 2 to 4, the AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA also decreased continuously. Hence, we will set n to 2 in the subsequent experiments.

Table 1.

AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA in the framework of 5-Fold CV while n = 2, 3, 4 separately.

| n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 4 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8967 ± 0.0027 | 0.8804 ± 0.0026 | 0.8109 ± 0.0052 |

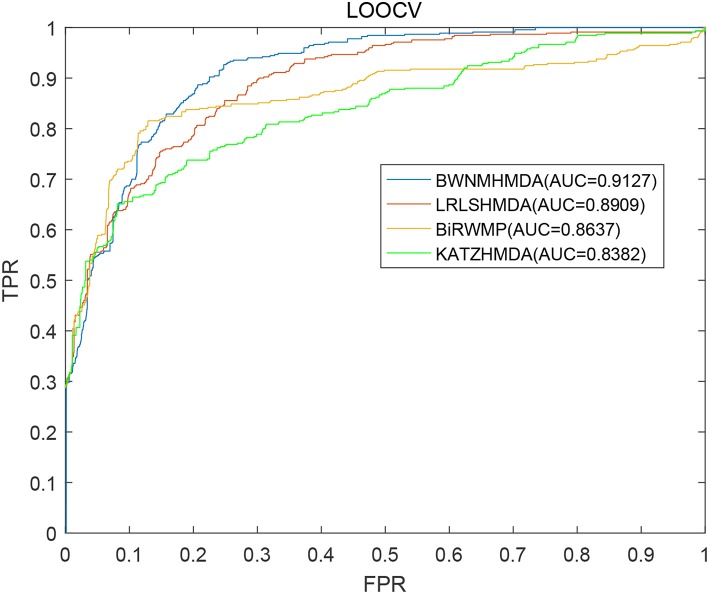

4.2. Comparison With Other State-of-the-Art Methods

In order to verify the prediction performance of BWNMHMDA, in this section, we compared it with KATZHMDA (Chen et al., 2017), BiRWMP (Shen et al., 2018), and LRLSHMDA (Wang et al., 2017) based on the dataset of known microbe-disease associations downloaded from the HMDAD database. And as illustrated in the following Figure 4 and Table 2, it is easy to see that in LOOCV, BWNMHMDA can achieve a reliable AUC of 0.9127 that is much better than the AUC achieved by KATZHMDA (0.8382), BiRWMP (0.8637), and LRLSHMDA (0.8909), and in the framework of 5-fold cross validation, BWNMHMDA can achieve a reliable AUC of 0.8967 ± 0.0027 that is much better than the AUC achieved by KATZHMDA (0.8301 ± 0.0033), BiRWMP (0.8522 ± 0.0054), and LRLSHMDA (0.8794 ± 0.0029) as well.

Figure 4.

AUCs achieved by KATZHMDA, BiRWMP, LRLSHMDA, and BWNMHMDA in LOOCV.

Table 2.

AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA, KATZHMDA, BiRWMP, and LRLSHMDA in LOOCV and 5-Fold CV separately.

| Method | LOOCV | 5-Fold CV |

|---|---|---|

| BWNMHMDA | 0.9127 | 0.8967 ± 0.0027 |

| LRLSHMDA | 0.8909 | 0.8794 ± 0.0029 |

| BiRWMP | 0.8637 | 0.8522 ± 0.0054 |

| KATZHMDA | 0.8382 | 0.8301 ± 0.0033 |

We further compare BWNMHMDA with NGRHMDA (Huang Y.A. et al., 2017), ABHMDA (Peng et al., 2018), and BMCMDA (Shi et al., 2018) in LOOCV based on the same dataset. As shown in Table 3, our method achieves the best performance.

Table 3.

AUCs achieved by BWNMHMDA, NGRHMDA, ABHMDA, and BMCMDA in LOOCV separately.

| Method | BWNMHMDA | NGRHMDA | ABHMDA | BMCMDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.9127 | 0.8938 | 0.8869 | 0.906 |

5. Case Studies

In order to further measure the prediction performance of BWNMHMDA, in this section, we selected three kinds of important human diseases such as asthma, colorectal carcinoma, and COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) to explore the associations between the human microbes and the human respiratory and digestive system diseases. Among them, asthma is a heterogeneous disease process accompanied by recurrent episodes of wheezing, chest tightness, difficulty breathing, and indirect cough (Busse, 2007). In recent years, the prevalence of asthma is rising rapidly. It is reported that about 8% of people have been affected by asthma by 2010, especially in the children's population (Guilbert et al., 2014). Hence, considering that asthma has been demonstrated to be closely associated with microbes as well (Çalşkan et al., 2013; Gilstrap and Kraft, 2013), for example, Hemophilia, Moraxella, and Neisseria spp. in the lungs of asthma patients are proved to be closely related to the increased risk of asthma in the neonatal oropharynx. Staphylococcus was found in the respiratory tract of children with asthma (Sullivan et al., 2016), in this section, we selected asthma as one of our case studies to evaluate the performance of BWNMHMDA. And as illustrated in the following Table 4, all of these top 10 microorganisms predicted by BWNMHMDA have been verified to be associated with the onset of asthma. For example, Tropheryma whipplei (Ranking first in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been confirmed to be abundant in airway of patients with eosinophilic asthma (Simpson et al., 2015). Clostridium difficile (Ranking second in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been confirmed to be associated with asthma after 6–7 years of colonization (van Nimwegen et al., 2011). Firmicutes (Ranking third in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been confirmed to be increased in severe asthmatics (Zhang et al., 2016). Furthermore, the increased sensitivity to Staphylococcus aureus (Ranking fifth in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been proved to be a marker of eosinophilic inflammation and severe asthma in asthmatic patients as well (Nagasaki et al., 2017). We published evidence for the top 10 potential asthma-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Top 10 potential asthma-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA and all of these 10 microbes have been confirmed by evidences.

| Rank | Microbe | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tropheryma whipplei | PMID: 26647445 |

| 2 | Clostridium difficile | PMID: 21872915 |

| 3 | Firmicutes | PMID: 27078029 |

| 4 | Lachnospiraceae | PMID: 26512904 |

| 5 | Staphylococcus aureus | PMID: 17950502 |

| 6 | Clostridia | PMID: 22047069 |

| 7 | Bacteroides | PMID: 18822123 |

| 8 | Fusobacterium | PMID: 24024497 |

| 9 | Clostridium coccoides | PMID: 21477358 |

| 10 | Actinobacteria | PMID: 23265859 |

In recent years, colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is becoming a major cause of cancer mortality in both China and the United States. In 2016, an estimated 134,000 people had been diagnosed with CRC, and approximately 49,000 had died of CRC (Bibbins-Domingo et al., 2008). By gender, CRC is the second most common cancer in women (about 9.2%) and the third in men (about 10%) (Astin et al., 2011). Since it has been proved that CRC is related to gut microbiota such as the Fusobacterium, the Bacteroides fragilis and the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and the dysbiosis of these gut microbiotas will induce colon cancer through a chronic inflammatory mechanism (Mármol et al., 2017). Hence in this section, we selected CRC as one of our case studies to evaluate the performance of BWNMHMDA. And as illustrated in the following Table 5, there are 9 out of these top 10 microorganisms predicted by BWNMHMDA have been verified to be associated with the onset of colorectal carcinoma. For instance, related studies have shown that the abundance of Firmicutes (Ranking 6th in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) in the lumen of CRC rats will increase, while the abundance of Bacteroidetes (Ranking 4th in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) will reduce. And moreover, the abundance of Proteobacteria (Ranking second in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been confirmed to be higher in CRC rats than in healthy rats. Meanwhile, Bacteroides (Ranking 9th in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been proved to of a relatively high abundance in CRC rats at the genus level. Prevotella (Ranking third in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has been found to be significantly more abundant in healthy rats than CRC rats (Zhu et al., 2014). Additionally, compared with the healthy control group, Fukugaiti MH et al. detected more C. difficile (Ranking 5th in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) in the cancer group, which suggests that these bacteria may play an important role in the colorectal carcinoma (Fukugaiti et al., 2015). We published evidence for the top 10 potential CRC-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA in the Table 5.

Table 5.

Top 10 potential CRC-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA and 9 out of these 10 microbes have been confirmed by evidences.

| Rank | Microbe | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tropheryma whipplei | Unconfirmed |

| 2 | Proteobacteria | PMID:24603888 |

| 3 | Prevotella | PMID:29432368 |

| 4 | Bacteroidetes | PMID:26992426 |

| 5 | Clostridium difficile | PMID:19807912 |

| 6 | Firmicutes | PMID:29985435 |

| 7 | Helicobacter pylori | PMID:11774957 |

| 8 | Clostridia | PMID:26691472 |

| 9 | Bacteroides | PMID:30090033 |

| 10 | Staphylococcus aureus | PMID:7074582 |

Finally, COPD is an obstructive pulmonary disease that worsens over time, and the main symptoms of COPD are shortness of breath and coughing. And as of 2015, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease accounted for approximately 174.5 million (about 2.4%) of the global population (Vos et al., 2016). For the past few years, due to high smoking rates and an aging population in developing countries, the death toll of COPD is rising fast (Mathers and Loncar, 2006). Although treatments can slow the progression of COPD, there is no cure yet. Considering that many evidences have demonstrated that there exist associations between microbiomes and COPD, for instance, Galiana et al. found that the microbiota diversity of patients with severe COPD was lower than that of mild/moderate diseases, and actinomyces accounted for a high proportion of patients with severe COPD (Galiana et al., 2013), hence in this section, we selected COPD as one of our case studies to evaluate the performance of BWNMHMDA. And as illustrated in the following Table 6, there are 8 out of these top 10 microorganisms predicted by BWNMHMDA have been verified to be associated with the onset of COPD. For instance, COPD has been confirmed to be a kind of essential comorbidity in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients, and more T. whipplei (Ranking first in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) has found in lower airway of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects (Segal et al., 2014; Sze et al., 2016). And also, it has been demonstrated that Proteobacteria (Ranking second in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) and Firmicutes (Ranking 3rd in the list of top 10 predicted microbes) will increase significantly with the development of COPD (Pragman et al., 2012). We published evidence for the top 10 potential COPD-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA in the Table 6.

Table 6.

Top 10 potential COPD-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA and 8 out of these 10 microbes have been confirmed by evidences.

| Rank | Microbe | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tropheryma whipplei | PMID:24460444 |

| 2 | Proteobacteria | PMID:23071781 |

| 3 | Bacteroidetes | PMID:29709671 |

| 4 | Prevotella | PMID:30053882 |

| 5 | Clostridium difficile | PMID:15655746 |

| 6 | Firmicutes | PMID:24591822 |

| 7 | Helicobacter pylori | PMID:15733502 |

| 8 | Lachnospiraceae | Unconfirmed |

| 9 | Staphylococcus aureus | Unconfirmed |

| 10 | Clostridia | PMID:26852737 |

Furthermore, in order to reconfirm the prediction performance of BWNMHMDA, we compared it with KATZHMDA in the case studies of these three kinds of same diseases, and as shown in the following Table 7, it is obvious that there are 10, 9, and 8 out of these top 10 microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA having been verified to be associated with the onset of asthma, colorectal carcinoma and COPD respectively, while there are only 4, 5, and 5 out of these top 10 microbes predicted by KATZHMDA having been verified to be associated with the onset of asthma, colorectal carcinoma, and COPD separately, which demonstrated that our prediction model BWNMHMDA could achieve better predictive hit rate in case above studies than the prediction model of KATZHMDA. And in addition, we published all these rankings of microbe-disease associations and top 10 disease-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, respectively, and hope that these data may provide some help to the future works of relevant researchers.

Table 7.

The number of of microbes having been confirmed by evidences in the top 10 potential disease-related microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA and KATZHMDA respectively in case studies of the three kinds of diseases such as Asthma, CRC, and COPD.

| Model | Asthma | colorectal carcinoma | COPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| BWNMHMDA | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| KATZHMDA | 4 | 5 | 5 |

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Human microbiome is normal flora for humans, which has been proved to be of symbiotic relationship with humans and harmless to humans. If the microbes that breed in the human body become “unhealthy,” it will definitely affect the host's physical condition. People are continuing to explore the pathologic relationship between microorganisms and the human body through high-throughput sequencing technologies and analysis systems. However, it is a pity that their pathogenesis cannot be fully understood as yet. Considering that relying only on conventional experimental methods is time-consuming and laborious, in this article, we proposed a novel prediction model called BWNMHMDA to accelerate the process of inferring potential microbe-disease associations, in which, the core idea is to construct a weighted bidirectional microbe-disease association network and then convert it into a matrix for correlation probability calculation. While constructing the prediction model BWNMHMDA, we first downloaded known microbe-disease associations from the HDMDA database, and then, based on these downloaded associations, we constructed a heterogeneous network through adopting the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity to calculate the weights of nodes in the heterogeneous network. Moreover, based on the heterogeneous network, we further constructed a weighted bidirectional network by standardizing the weights of edges in the heterogeneous network and introducing a novel bidirectional recommendation method. Finally, we transformed the weighted bidirectional network into an integration matrix that can be utilized for prediction of potential microbe-disease associations. And simulation results show that BWNMHMDA can achieve reliable AUCs of 0.9127 and 0.8967 ± 0.0027 in the frameworks of LOOCV and 5-Fold CV respectively. And moreover, in the case studies of asthma, colorectal cancer, and COPD, there are 10, 9, and 8 out of the top 10 potential associated microbes predicted by BWNMHMDA having been verified by published literature evidence, which demonstrated that BWNMHMDA could provide valuable potential microbe-disease associations for future biological experiments. Certainly, there are some deficiencies in BWNMHMDA. For instance, there is a lack of negative samples in BWNMHMDA, and it may be possible to improve the predictive reliability of BWNMHMDA by identifying unrelated microbe-disease pairs. And moreover, in BWNMHMDA, we adopt the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity to calculate the similarities between microbes, which may bias the similarity between some individual microbes. Hence, in subsequent work, we will introduce some effective methods such as Symptom-Based Disease Similarity (Zhou et al., 2014) to further improve the accuracy and efficiency of BWNMHMDA.

Author Contributions

HL and LW conceptualized the study. HL and YW created the methodology, conducted the validation, and the data curation. HL, YW, HZ, and LW conducted the formal analysis. JJ, XF, HZ, and BZ oversaw the investigations. HL provided resources and prepared and wrote the original draft. LW wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript, supervised the project, oversaw project administration, and acquired funding.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The project is partly sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.61873221, No. 61672447), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No.2018JJ4058, No.2017JJ5036), and the CERNET Next Generation Internet Technology Innovation Project (No.NGII20160305, No.NGII20170109).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00676/full#supplementary-material

Ranks of microbe-disease associations predicted by BWNMHMDA.

Top 10 related microbes of all diseases.

References

- Astin M., Griffin T., Neal R. D., Rose P., Hamilton W. (2011). The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 61, e231–e243. 10.3399/bjgp11X572427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar A. P., Guttman J. A., Finlay B. B. (2007). Manipulation of host-cell pathways by bacterial pathogens. Nature 449, 827–834. 10.1038/nature06247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbins-Domingo K., Grossman D. C., Curry S. J., Davidson K. W., Epling J. W. E. A. (2008). Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 149:627 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. T., Davis-Richardson A. G., Giongo A., Gano K. A., Crabb D. B., Mukherjee N., et al. (2011). Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE 6:e25792. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse W. W. (2007). Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–summary report 2007. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, S94–S138. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çalşkan M., Bochkov Y. A., Kreiner-Møller E., Bønnelykke K., Stein M. M., Du G., et al. (2013). Rhinovirus wheezing illness and genetic risk of childhood-onset asthma. New Engl. J. Med. 368, 1398–1407. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Yu W.-H., Izard J., Baranova O. V., Lakshmanan A., Dewhirst F. E. (2010). The human oral microbiome database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database 2010, baq013–baq013. 10.1093/database/baq013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. (2015). KATZLDA: KATZ measure for the lncRNA-disease association prediction. Sci. Rep. 5:16840. 10.1038/srep16840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Huang Y.-A., You Z.-H., Yan G.-Y., Wang X.-S. (2017). A novel approach based on KATZ measure to predict associations of human microbiota with non-infectious diseases. Bioinformatics 34, 1440–1440. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu M.-X., Yan G.-Y. (2012). Drug–target interaction prediction by random walk on the heterogeneous network. Mol. BioSyst. 8:1970. 10.1039/c2mb00002d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ren B., Chen M., Wang Q., Zhang L., Yan G. (2016a). NLLSS: Predicting synergistic drug combinations based on semi-supervised learning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12:e1004975. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Sun Y.-Z., Guan N.-N., Qu J., Huang Z.-A., Zhu Z.-X., et al. (2018a). Computational models for lncRNA function prediction and functional similarity calculation. Brief. Funct. Genomics 18, 58–82. 10.1093/bfgp/ely031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang L., Qu J., Guan N.-N., Li J.-Q. (2018b). Predicting miRNA–disease association based on inductive matrix completion. Bioinformatics 34, 4256–4265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Xie D., Wang L., Zhao Q., You Z.-H., Liu H. (2018c). BNPMDA: Bipartite network projection for MiRNA–disease association prediction. Bioinformatics 34, 3178–3186. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yan C. C., Zhang X., You Z.-H. (2016b). Long non-coding RNAs and complex diseases: from experimental results to computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 18, 558–576. 10.1093/bib/bbw060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yan G.-Y. (2013). Novel human lncRNA–disease association inference based on lncRNA expression profiles. Bioinformatics 29, 2617–2624. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yan G.-Y. (2014). Semi-supervised learning for potential human microRNA-disease associations inference. Sci. Rep. 4:5501. 10.1038/srep05501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L. A., Maurice C. F., Carmody R. N., Gootenberg D. B., Button J. E., Wolfe B. E., et al. (2013). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563. 10.1038/nature12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S. H., Belenguer A., Holtrop G., Johnstone A. M., Flint H. J., Lobley G. E. (2006). Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1073–1078. 10.1128/AEM.02340-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith J. J., Driscoll M. E., Fusaro V. A., Cosgrove E. J., Hayete B., Juhn F. S., et al. (2007). Many microbe microarrays database: uniformly normalized affymetrix compendia with structured experimental metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D866–D870. 10.1093/nar/gkm815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukugaiti M. H., Ignacio A., Fernandes M. R., Júnior U. R., Nakano V., Avila-Campos M. J. (2015). High occurrence of fusobacterium nucleatum and Clostridium difficile in the intestinal microbiota of colorectal carcinoma patients. Braz. J. Microbiol. 46, 1135–1140. 10.1590/S1517-838246420140665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiana A., Aguirre E., Rodriguez J. C., Mira A., Santibanez M., Candela I., et al. (2013). Sputum microbiota in moderate versus severe patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 43, 1787–1790. 10.1183/09031936.00191513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J. A., Dupont C. L. (2011). Microbial metagenomics: beyond the genome. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 347–371. 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J. A., Meyer F., Antonopoulos D., Balaji P., Brown C. T., Brown C. T., et al. (2010). Meeting report: the terabase metagenomics workshop and the vision of an earth microbiome project. Stand. Genomic Sci. 3, 243–248. 10.4056/sigs.1433550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. R., Pop M., DeBoy R. T., Eckburg P. B., Turnbaugh P. J., Samuel B. S., et al. (2006). Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312, 1355–1359. 10.1126/science.1124234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap D. L., Kraft M. (2013). Asthma and the host-microbe interaction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 1449–1450.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarner F., Malagelada J.-R. (2003). Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 361, 512–519. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbert T. W., Mauger D. T., Lemanske R. F. (2014). Childhood asthma-predictive phenotype. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2, 664–670. 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe B., Groothoff J. W., Hulton S.-A., Cochat P., Niaudet P., Kemper M. J., et al. (2011). Efficacy and safety of oxalobacter formigenes to reduce urinary oxalate in primary hyperoxaluria. Nephrol. Dialys. Transpl. 26, 3609–3615. 10.1093/ndt/gfr107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-A., You Z.-H., Chen X., Huang Z.-A., Zhang S., Yan G.-Y. (2017). Prediction of microbe–disease association from the integration of neighbor and graph with collaborative recommendation model. J. Transl. Med. 15:209. 10.1186/s12967-017-1304-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. J. (2013). Asthma microbiome studies and the potential for new therapeutic strategies. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 13, 453–461. 10.1007/s11882-013-0355-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.-A., Chen X., Zhu Z., Liu H., Yan G.-Y., You Z.-H., et al. (2017). PBHMDA: Path-based human microbe-disease association prediction. Front. Microbiol. 8:233. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesmok E. M., Hopkins J. M., Foran D. R. (2016). Next-generation sequencing of the bacterial 16s rRNA gene for forensic soil comparison: a feasibility study. J. Forens. Sci. 61, 607–617. 10.1111/1556-4029.13049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. (1953). A new status index derived from sociometric analysis. Psychometrika 18, 39–43. 10.1007/BF02289026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Backhed F., Turnbaugh P., Lozupone C. A., Knight R. D., Gordon J. I. (2005). Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11070–11075. 10.1073/pnas.0504978102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Turnbaugh P. J., Klein S., Gordon J. I. (2006). Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444, 1022–1023. 10.1038/4441022a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Zhang L., Zeng P., Huang C., Li J., Geng B., et al. (2016). An analysis of human microbe–disease associations. Brief. Bioinform. 18, 85–97. 10.1093/bib/bbw005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mármol I., de Diego C. S., Dieste A. P., Cerrada E., Yoldi M. R. (2017). Colorectal carcinoma: a general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:E197. 10.3390/ijms18010197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. R., Preshaw P. M., Nagaraja H. N., Dabdoub S. M., Rahman A., Kumar P. S. (2014). The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. ISME J. 9, 268–272. 10.1038/ismej.2014.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C. D., Loncar D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3:e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Sakamoto M., Hayashi H., Benno Y. (2005). Novel phylogenetic assignment database for terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of human colonic microbiota. J. Microbiol. Methods 61, 305–319. 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methé B. A., Nelson K. E., Pop M., Creasy H. H., Giglio M. G., Huttenhower C., et al. (2012). A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 486, 215–221. 10.1038/nature11209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaelyan A., Köhler T., Lampert N., Rohland J., Boga H., Meuser K., et al. (2015). Classifying the bacterial gut microbiota of termites and cockroaches: a curated phylogenetic reference database (DictDb). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 38, 472–482. 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W., Moore L. H. (1995). Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3202–3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki T., Matsumoto H., Oguma T., Ito I., Inoue H., Iwata T., et al. (2017). Sensitization to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins in smokers with asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 119, 408–414.e2. 10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L.-H., Yin J., Zhou L., Liu M.-X., Zhao Y. (2018). Human microbe-disease association prediction based on adaptive boosting. Front. Microbiol. 9:2440. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragman A. A., Kim H. B., Reilly C. S., Wendt C., Isaacson R. E. (2012). The lung microbiome in moderate and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE 7:e47305. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Li Y., Cai Z., Li S., Zhu J., Zhang F., et al. (2012). A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60. 10.1038/nature11450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley E. M. (2013). Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 560–569. Available online at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Gut%20bacteria%20in%20health%20and%20disease&publication_year=2013&author=E.M.M.%20Quigley [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch M., Lynch S. (2012). The potential for probiotic manipulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 192–201. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal L. N., Rom W. N., Weiden M. D. (2014). Lung microbiome for clinicians. New discoveries about bugs in healthy and diseased lungs. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11, 108–116. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-339FR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sender R., Fuchs S., Milo R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 14:e1002533. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P., Fritz J. V., Glaab E., Desai M. S., Greenhalgh K., Frachet A., et al. (2016). A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human–microbe interface. Nat. Commun. 7:11535. 10.1038/ncomms11535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Zhu H., Jiang X., Hu X., Yang J. (2018). “A novel approach based on bi-random walk to predict microbe-disease associations,” in Intelligent Computing Methodologies, eds Huang D.-S., Gromiha M. M., Han K., Hussain A. (Springer International Publishing; ), 746–752. [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.-Y., Huang H., Zhang Y.-N., Cao J.-B., Yiu S.-M. (2018). BMCMDA: a novel model for predicting human microbe-disease associations via binary matrix completion. BMC Bioinformatics 19:281. 10.1186/s12859-018-2274-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. L., Daly J., Baines K. J., Yang I. A., Upham J. W., Reynolds P. N., et al. (2015). Airway dysbiosis:haemophilus influenzaeandTropherymain poorly controlled asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 792–800. 10.1183/13993003.00405-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan A., Hunt E., MacSharry J., Murphy D. M. (2016). The microbiome and the pathophysiology of asthma. Respir. Res. 17:163. 10.1186/s12931-016-0479-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze M. A., Xu S., Leung J. M., Vucic E. A., Shaipanich T., Moghadam A., et al. (2016). The bronchial epithelial cell bacterial microbiome and host response in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. BMC Pulmon. Med. 16:142. 10.1186/s12890-016-0303-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. C., Amaral G. R., Campeão M., Edwards R. A., Polz M. F., Dutilh B. E., et al. (2014). Microbial taxonomy in the post-genomic era: rebuilding from scratch? Arch. Microbiol. 197, 359–370. 10.1007/s00203-014-1071-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2007). The human microbiome project. Nature 449:804. 10.1038/nature06244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Laarhoven T., Nabuurs S. B., Marchiori E. (2011). Gaussian interaction profile kernels for predicting drug–target interaction. Bioinformatics 27, 3036–3043. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nimwegen F. A., Penders J., Stobberingh E. E., Postma D. S., Koppelman G. H., Kerkhof M., et al. (2011). Mode and place of delivery, gastrointestinal microbiota, and their influence on asthma and atopy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 128, 948–955.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T., Allen C., Arora M., Barber R. M., Bhutta Z. A., Brown A., et al. (2016). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 388, 1545–1602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. W., Ince J., Duncan S. H., Webster L. M., Holtrop G., Ze X., et al. (2010). Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 5, 220–230. 10.1038/ismej.2010.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Huang Z.-A., Chen X., Zhu Z., Wen Z., Zhao J., et al. (2017). LRLSHMDA: Laplacian regularized least squares for human microbe–disease association prediction. Sci. Rep. 7:7601. 10.1038/s41598-017-08127-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L., Ley R. E., Volchkov P. Y., Stranges P. B., Avanesyan L., Stonebraker A. C., et al. (2008). Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of type 1 diabetes. Nature 455, 1109–1113. 10.1038/nature07336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y.-Y., Keilbaugh S. A., et al. (2011). Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108. 10.1126/science.1208344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan Z., Li J., Yu J., Feng X., Zhao B., Wang L. (2019). A probabilistic matrix factorization method for identifying lncRNA-disease associations. Genes 10:126. 10.3390/genes10020126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Gao L., Guo X., Shi X., Wu H., Song F., et al. (2014). A network based method for analysis of lncRNA-disease associations and prediction of lncRNAs implicated in diseases. PLoS ONE 9:e87797. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Z.-H., Huang Z.-A., Zhu Z., Yan G.-Y., Li Z.-W., Wen Z., et al. (2017). PBMDA: A novel and effective path-based computational model for miRNA-disease association prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005455. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Ping P., Wang L., Kuang L., Li X., Wu Z. (2018). A novel probability model for LncRNA–disease association prediction based on the naïve bayesian classifier. Genes 9:345 10.3390/genes9070345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., DiBaise J. K., Zuccolo A., Kudrna D., Braidotti M., Yu Y., et al. (2009). Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2365–2370. 10.1073/pnas.0812600106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Cox M., Liang Z., Brinkmann F., Cardenas P. A., Duff R., et al. (2016). Airway microbiota in severe asthma and relationship to asthma severity and phenotypes. PLoS ONE 11:e0152724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Menche J., Barabási A.-L., Sharma A. (2014). Human symptoms–disease network. Nat. Commun. 5:5212. 10.1038/ncomms5212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Jin Z., Wu W., Gao R., Guo B., Gao Z., et al. (2014). Analysis of the intestinal lumen microbiota in an animal model of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 9:e90849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ranks of microbe-disease associations predicted by BWNMHMDA.

Top 10 related microbes of all diseases.