ABSTRACT

Doctors have a central role in managing patients across a multitude of clinical environments, which places them in the ideal position to identify systemic issues. Traditional medical training focuses on the knowledge and technical skills required; rarely are doctors trained in leadership, management or how to analyse and understand systems so as to design safer, better care. Quality improvement methodology is an approach that is known to enable improvement of the systems in which healthcare professionals work in order to provide safe, timely, evidence-based, equitable, efficient and patient-centred care. To address the current disparity, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) has launched a Quality Improvement Hub, which will aim to support physicians to face the challenges of improving medical care, enabling them to navigate the tools with more confidence and share and implement the learning more swiftly.

KEYWORDS: Education, leadership, management, quality, quality improvement

Introduction

Continuous improvement of healthcare is not a new concept; this was recognised in the 1840s by Ignaz Semmelweis who discovered the role of anti-septic hand hygiene in reducing maternal death rates.1 Florence Nightingale, during the Crimean War, sought to improve sanitation in her quest for better clinical outcomes in wounded servicemen.2 Fast forward to the 21st century where healthcare systems, because of the need to transform healthcare provision, face huge challenges to provide safe, evidence-based and reliable care.3 Despite a drive to improve quality and patient safety in the last 15 years, 5–10% of admissions to hospital still result in harm,4,5 with avoidable mortality rates currently at around 3–5%.6–9 Most safety events are not the result of an individual acting carelessly, but rather due to systems failure. Doctors need to be equipped with the skills and awareness required to improve these figures.10 Healthcare has been late in its recognition of the contribution that the theory and practice of quality improvement is able to make to delivering better value care and is not universally understood or accepted as practical.11

Aviation has sought to improve passenger safety by preventing and identifying threats before they occur through continually learning from near-miss situations.12 The aviation industry realised that 70% of accidents were due to breakdowns in communication and in response to this developed standardised approaches, tools and behaviours to improve safety.13 Aviation achieves its exemplary safety record by viewing failure as an opportunity to learn; this is in stark contrast to healthcare, where failure is viewed as incompetence and associated with a blame culture.14 Medicine is different to aviation in its variety and risk but there is much to learn from their approaches to high reliability and continuous improvement in complex systems where humans and technology seek to deliver optimal outcomes.

In healthcare, the traditional training of physicians focuses on specialist knowledge acquisition, clinical skills and often does not consider how to improve the systems and environment in which clinicians work.11,15 Failure to test a new approach rigorously in the clinic or the ward before implementing can result in resistance or unintended consequences undermining the purpose of the change. The General Medical Council reflects the consensus that ‘doctors must take part in systems of quality assurance and quality improvement to promote patient safety’.16 This can be achieved through the correct application of quality improvement methodology as described in the Berwick report, which stated ‘the capability to measure and continually improve the quality of patient care needs to be taught and learned or it will not exist’.17

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) has already invested heavily in supporting physicians and their teams to improve the quality of care given to patients through national clinical audit and its successful Learning to make a difference quality improvement programme for core medical trainees.18 The RCP Quality Improvement Hub will aim to bring together these and other resources, tools and methodologies, and combine them with coaching and networking. By acting as a repository for quality improvement work, the hub aims to make quality improvement easily accessible to all doctors and support physicians in developing and providing safe, timely, evidence-based, equitable, efficient and patient-centred care (Box 1).15,19,20 Box 2 summarises the scope of ‘quality’ with respect to patient care and the mix of approaches that will support physicians and their teams to improve whatever aspect of quality is in need of improvement.21–25

Box 1.

The RCP Quality Improvement Hub's broad aims

The aims of the RCP Quality Improvement Hub align with those of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, improvement experts and the Health Foundation:15,19,20

|

Box 2.

How to define quality and enable improvement?

| There is no single definition of quality improvement and the words quality and improvement may mean different things to different individuals. |

Quality improvement is about unceasingly seeking excellence through the patient journey.21 Lord Darzi's 2008 report entitled High quality healthcare for all22 confirmed the government's shift in healthcare towards quality and placed an emphasis on staff to drive improvement within the following domains of quality:

|

The Institute of Medicine has identified six domains of quality; these are:21,23

|

There are many approaches to quality improvement including:24

|

| Building the foundations for improvement in any system or organisation seems to benefit from a mixture of these approaches.25 |

The challenge

To improve patient care, a range of strategies, such as clinical guidelines, audit,18 systems understanding and, where necessary, their redesign, are required. Quality improvement is premised on improving complex systems of work and there is nothing more complex than healthcare delivery. Quality improvement science and approaches have a significant contribution to make; however, such service improvement takes time and requires leadership.26

There is a growing need for clinical leadership in response to the increasing complexity of managing patients with multiple needs and interconnected morbidities. In some cases, increasing operational and organisational complexity has resulted in doctors becoming less engaged in change.26 With executive leader ‘buy in’, improved use of data (eg mortality data) and spotlight reporting may help direct resources and the focus of the organisation, creating a common purpose for clinicians and management.27

There are many areas in clinical medicine/practice where no exact consensus or guidelines exist, which can lead to variation in standard of care.28 Quality improvement can be used to tackle this, reduce waste and allow organisations to become more person centred.29 Evidence suggests that safer, high-quality care is more efficient, less costly and leads to better patient outcomes.25,30 Understanding the ‘microsystem’ in which physicians and their teams work can ensure care is designed to be better matched to the needs of both the patient and the team.13,15,28

When considering service improvement, clinicians and managers may be more familiar with audit, peer review and traditional academia rather than quality improvement methodologies.10 Local clinical audit is used to ensure adherence to best practice guidelines and is usually carried out by the most junior members of the team who are rarely empowered to make the changes they identify as needed. Such experience is neither motivating nor likely to result in improved quality of patient care. Only 5% of local clinical audit undertaken by junior doctors leads to a change in practice.31 In contrast, of those who have undertaken a quality improvement project, 85% said they felt they had made a difference to patient care via a beneficial sustainable change and 94% stated they had developed new skills.18

The challenge remains to make quality improvement methods the way all clinicians approach poor quality care as part of everyday practice.32 Junior doctors should be engaged to undertake team-based, continuous improvement rather than solitary audit projects over a short time period for their training portfolio.15

Exposure to quality improvement educational approaches is inconsistent and awareness of quality improvement is variable.24 The Health Foundation has identified barriers to success for clinical teams undertaking quality improvement. Issues, such as unrealistic goals, insufficient leadership and lack of dissemination because of ownership of a project, can inhibit sustainability and the effects of initiatives.33 There are also logistical issues, such as limited finances, hierarchy or resources.34 Quality improvement may not always be deemed a priority because there are powerful groups within the NHS that may not wish to change working practices.33 Directing professionals to engage in quality improvement may be perceived by some as ‘a target’ and the motivation to become involved lost.35

Many of the challenges facing clinicians are driven by external factors, eg revalidation and regulation. This leaves little time for personal investment into an organisation, particularly at a junior level where doctors have short placements. Regulation and inspection has come to the fore as the main way of maintaining patient safety; however, there are those, including Don Berwick, who propose that this has developed a culture of blame where poorly performing trusts are penalised.11

The purpose of the Quality Improvement Hub

The RCP Quality Improvement Hub will engage clinicians at an early stage of their training to make changes to their day-to-day work and encourage the use of appropriate data as a driver for improvement.36 The hub will aim to achieve this by supporting and mentoring teams undertaking quality improvement work in addition to focusing on the psychology of change, such as challenging the beliefs, values and assumptions of those working in the system.24,36

The RCP is committed to ensuring ‘the best possible health and healthcare for everyone’ and emphasises the need to improve care for patients via ‘quality and service improvement’.37 The hub will aim to build on this by supporting clinicians to develop and establish sustainable quality improvement competencies and capability, and enabling capacity for improvement to be developed across the clinical team.

The hub will increasingly align the emphasis of bodies such as the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and ensure physicians have national and local resources where required. As the home of many commissioned national clinical audits, such as the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme and the Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme, the RCP and the hub are well placed to provide baseline data and then support and coach teams to use systems thinking and improvement methods to close the gaps in care within their organisation.

The hub will aim to pool what is known in other systems and organisations and to share it in a useful way to accelerate learning, prevent ‘reinventing of the wheel’ and to encourage adaptation through quality improvement methods.

The hub's intention is to improve leadership skills via an important partnership with the Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management. The RCP is also one of the largest host organisations of the National Medical Director's fellowship scheme. The hub and the RCP will invest in and enable junior doctors to identify and rectify systemic issues.38,39

Patients have been proactively involved in improving the safety of services and systems via their unique perspective and challenging of healthcare professionals on patient safety.40 The RCP is home to an expanding patient and carer network.

Lessons already learned

There is limited literature on training and outcomes of quality improvement in medical specialties; most of the literature focuses on junior doctors.40,41 However, the literature does indicate that education based on quality improvement is generally well received by trainees, improves knowledge in up to 87% of doctors and results in better patient outcomes and improved patient safety.42–44 Although studies in early 2000s have shown limited clinical benefit of quality improvement teaching among trainee doctors,45 more recent systematic reviews have found that quality improvement curricula have successfully implemented local changes in care delivery with many significantly improving care for patients. Factors contributing to the successful implementation of curricula included committed faculties with learner buy in and enthusiasm.44

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges has published a report stating the need for integrated quality improvement curricula.15 The report states that quality improvement should be understood by all healthcare workers so that they can contribute, when required, to improving outcomes for patients. In order to address this, supportive educational programmes are required and should include experiential learning on safety and quality, alongside the teaching of quality improvement and systems theory.32

The benefits of integrating quality improvement training into the undergraduate curriculum in the UK have been demonstrated;46 however, not all medical schools currently teach quality improvement and the postgraduate curricula do not fully integrate training in quality improvement or human factors.15 Foundation and core medical trainees are encouraged to undertake quality improvement projects in place of local clinical audit. Examples of where this has worked well include the London Deanery ‘beyond audit’ workshops, which use quality improvement initiatives to introduce junior doctors to management and leadership;47 the Severn Deanery, which has delivered over 30 quality improvement projects among foundation year 1 doctors, improving weekend handover and standardising ward equipment;48 and Great Ormond Street, which has developed a programme entitled EQuIP – enabling doctors in quality improvement and patient safety. The EQuIP programme was deemed valuable by 100% of participants, all of which were committed to sustained quality improvement, with 92% of participants developing new skills. The programme recognises the investment of training doctors in these skills to lead quality improvement in a variety of healthcare settings,32 replicating findings from the USA.41

Utilising quality improvement approaches in planning and steering the hub

The Driver Diagram

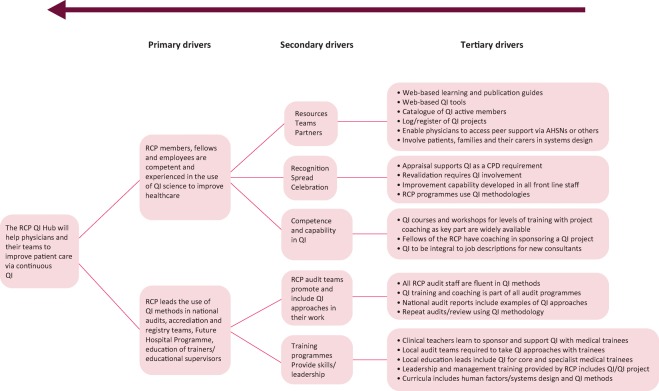

Fig 1 displays the plans and purpose for the RCP Quality Improvement Hub in a single action effect or driver diagram. The main aim is to equip all physicians to continuously improve their care, recognising the increasing complexity of that care and of the system in which it is delivered. The primary drivers are the skills and abilities of RCP fellows and members, and the embedding of quality improvement approaches into the work the RCP undertakes in patient care. The secondary drivers provide clear headings and the tertiary drivers detail some of the change intentions and ideas that evidence tells us will drive our aim forward.

Fig 1.

The RCP Quality Improvement (QI) Hub driver diagram.

The driver diagram is an iterative tool that seeks to provide as much clarity as practical along with a menu of projects and activities that are supporting success. This ensures that each project/innovation is aligned and those working on one area see the value of their work to the overarching aim on the left.

Measurement for improvement

A key component of successful quality improvement is the measurement of the impact of changes as they are tested and developed – so-called ‘time ordered data’. This is an alternative to delayed and aggregated data collected many months down the line. Knowing what is working now and continuously adapting change to maximise its effect is a critical improvement strategy. ‘How will we know a change is an improvement’ is the mantra of the successful improver. Fig 1 seeks to describe what we will be measuring as the hub develops. This will include hits on web pages, downloads of tools, titles and content of completed projects and posters submitted to conferences as well as softer items such as self-reporting of confidence in quality improvement methods, involvement in projects, knowledge of human factors and their use in safe design. One key measure will be the use of improvement methods within the national audit programmes to accelerate the rate of improvement for services under review or implementing new standards of care (Box 3). As with all improvement projects, the likelihood is that with success we become more ambitious and the scope of what we measure and the expectations increase over time.

Box 3.

Measuring success

Success of the RCP Quality Improvement Hub will be measured as follows:

|

Conclusion

Don Berwick said ‘the NHS should continually and forever reduce patient harm by embracing wholeheartedly an ethic of learning’.17 In the changing climate of the NHS, the emphasis is now on improving the quality and experience of care offered to patients and their relatives. Physicians and their teams working on the front line are the best placed to identify where change is required and it is vital that they are empowered to undertake this work. Quality improvement methodology is an approach that has been successfully used to improve care for patients in a multitude of settings. In order for quality improvement to be feasible and sustainable, it has to be supported; the RCP Quality Improvement Hub will support physicians and their teams in developing new and existing skills in order to address and tackle established problems. The hub will support physicians in building quality improvement capability and, in doing so, develop the leadership skills of physicians to ensure that all, from board level to the ward, are involved with improving quality and that healthcare professionals will see quality improvement as integral to their job. The RCP is best placed to do this among physicians as it holds an influential and credible position amongst its 33,000 members and fellows and has already invested heavily in improving the care given to patients in the NHS. The RCP Quality Improvement Hub will stimulate the debate on quality improvement and provide organisations with a way of integrating improvement capability in a supportive and professional manner.

In the words of Catherine Boot, co-founder of the Salvation Army, ‘if we are to better the future, we must disturb the present’. We hope the Quality Improvement Hub will better the future, respectful of the fact that research, audit and quality improvement methods are each critical to continuously improving our health service.

Conflicts of interest

KS and PW were funded for 1 year as quality improvement fellows by the Health Foundation in 2009 and 2010, respectively.

References

- 1.Semmelweis IP. Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers [The etiology, concept and prophylaxis of childbed fever]. Pest, Wien und Leipzig, CA: Hartleben's Verlag–Expedition, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fee E, Garofalo M. Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Physicians Hospitals on the edge? The time for action. London: RCP, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.House of Commons Health Committee Patient safety. Sixth report of session 2008–09, volume I London: The Stationary Office, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perla R, Hohmann SF, Annis K. Whole-patient measure of safety: using administrative data to assess the probability of highly undesirable events during hospitalisation. J Healthc Qual 2013;35:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan H, Healey F, Neale G, et al. Preventable deaths due to problems in care in English acute hospitals: a retrospective case record review study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:737–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayward R, Hofer T. Estimating hospital deaths due to medical error – preventability is in the eye of the reviewer. JAMA 2001;286:415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Adverse events and potentially preventable deaths in Dutch hospitals: results of a retrospective patient record review study. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan H, Zipfel R, Neuburger J, et al. Avoidability of hospital deaths and association with hospital-wide mortality ratios: retrospective case record review and regression analysis. BMJ 2015;351:h3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones B, Woodhead T. Building the foundations for the improver. London: The Health Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ham C, Berwick D, Dixon J. Improving quality in the English NHS: a strategy for action. London: The King's Fund, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, Stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2000;320:745–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:i85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syed M. Black box thinking: The surprising truth about success. London: John Murray Publishers, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Quality improvement – training for better outcomes. London: AoMRC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Medical Council Good medical practice. London: GMC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berwick D. A promise to learn – a commitment to act: improving the safety of patients in England. London: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaux E, Went S, Norris M, et al. Learning to make a difference: introducing quality improvement methods to core medical trainees. Clin Med 2012;12:520–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allcock C, Dorman F, Taunt R, et al. Constructive comfort accelerating change in the NHS. London: The Health Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodhead T, Lachman P, Mountford P, et al. From harm to hope and purposeful action: what could we do after Francis? BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:619–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemer C, Cheung CRLH, Klaber RE. An introduction to quality improvement in paediatrics and child health. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2013;98:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darzi A. High quality care for all. NHS next stage review final report. London: The Stationary Office, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee on quality of healthcare in America Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: Institute of medicine, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Runnacles J, Roueche A. Supporting colleagues to improve care: educations for quality improvement. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2015;100:187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tricco AC, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;379:2252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohmer R. The instrumental value of medical leadership. Engaging doctors in improving services. London: The King's Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mountford J, Wakefield D. From spotlight reports to time series: equipping boards and leadership teams to driver better decisions. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005303 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohmer R. Clinical leadership for service improvement. London: The King's Fund, 2012. www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/richard-bohmer-clinical-leadership-service-improvement [Accessed 12 September 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon-Woods McNichol S, Martin G. Overcoming challenges to improving quality. London: The Health Foundation, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alderwick H, Robertson R, Appleby J, et al. Better value in the NHS: the role of changes in clinical practice. London: The Kings Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.John CM, Mathew DE, Gnanalingham MG. An audit of paediatric audits. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:1128–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runnacles J, Moult B, Lachmann P. Developing future clinical leaders for quality improvement: experience from a London children's hospital. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:956–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Silva D. What's getting in the way? Barriers to improvement in the NHS. London: The Health Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pronovost PJ, Holzmueller CG, Molello NE, et al. The Armstrong institute: an academic institute for patient safety and quality improvement, research, training and practice. Acad Med 2015;90:1331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bethune R, Soo E, Woodhead P, et al. Engaging all doctors in continuous quality improvement: a structured, supported programme for first-year doctors across a training deanery in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lachman P, Runnacles J, Dudley J. Equipped: overcoming barriers to improve quality of care (theories of change). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2015;100:13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Royal College of Physicians RCP strategy 2015–2020. London: RCP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown B, Ahmed-Little Y, Stanton E. Why we cannot afford not to engage junior doctors in NHS leadership. J R Soc Med 2012;105:105–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardacre J, Cragg R, Sharpio J, et al. What's leadership got to do with it? London: The Health Foundation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Hara J, Isden R. Identifying and monitoring safety: the role of patient and citizens. London: The Health Foundation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fok MC, Wong Ry. Impact of a competency based curriculum on quality improvement among internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim CS, Lukela MP, Parekh VI, et al. Teaching internal medicine residents quality improvement and patient safety: a lean thinking approach. Am J Med Qual 2010;25:211–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodrigue C, Seoane L, Gala RB, Piazza J, Amedee RG. Implantation of a faculty development curriculum emphasising quality improvement and patient safety: results of a qualitative study. Ochsner J 2013;13:319–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, et al. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systemic review. Acada Med 2010;85:1425–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boonyassi RT, Windish DM, Chakaraborti C, et al. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians. JAMA 2007;298:1023–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair P, Barai I, Prasad S, Gadhvi K. Quality improvement teaching at medical school: a student perspective. Adv Med Educ Pract 2016;7:171–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roueche A, Hewitt J. ‘Wading through treacle’: quality improvement lessons from the frontline BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bethune R, Soo E, Woodhead P, et al. Engaging all doctors in continuous quality improvement: a structured, supported programme for first-year doctors across a training deanery in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]