Abstract

The growing importance of a college degree for economic stability, coupled with increasing educational inequality in the United States, suggest potential criminogenic implications for downward educational mobility. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), this article examines the associations between intergenerational educational mobility, neighborhood disadvantage in adulthood, and crime. Drawing on the few extant studies of educational mobility and crime, as well as social comparison theory, it tests whether the consequences of downward educational mobility are moderated by neighborhood contexts. Results suggest that downward mobility is associated with increases in crime, and most strongly in more advantaged neighborhoods. The implications of these findings for future research on social mobility, education, and crime are discussed.

Keywords: education, social mobility, life course criminology, relative deprivation

Introduction

The significance of postsecondary education in the United States has never been greater, as enrollment continues to rise (Center on Education and the Workforce [CEW], 2013), and jobs increasingly require educational training beyond a high school diploma (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2015). At the same time as enrollment grows, increasing inequality suggests that downward educational mobility is also on the rise (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD], 2016), with potentially serious consequences for well-being and crime.

Research within criminology shows that educational attainment is negatively associated with crime (e.g., Farrington, 1989; Payne & Welch, 2013) and positively related to other pro-social transitions—that is, marriage and employment (Jacob, 2011; Sampson & Laub, 1993; Siennick & Osgood, 2008)—said to represent turning points in the life course. Whether education signifies a turning point, however, is contingent upon how it relates to one’s life course trajectory. This raises the issue of intergenerational social mobility—or a comparison of one’s educational attainments with those of one’s parents. For instance, obtaining a bachelor’s degree for those from families with few educational resources may symbolize a significant instance of upward mobility, whereas the same attainment may simply be expected for those with more educated parents. Conversely, when educational accomplishments end up being lower than one’s parents, it represents a loss in status—or downward mobility.

Few studies have examined the association between educational mobility and crime. An exception is Savolainen, Aaltonen, Merikukk, Paananen, and Kissler (2014), who found little effect of educational mobility on crime within a Finnish sample. Another example is by Swisher and Dennison (2016), who found upward mobility to be associated with decreases in crime, and downward mobility to increase crime in the United States. Additional research is needed, as many questions remain about the relationship between educational mobility and crime. For example, what role does contextual or geographical variation in socioeconomic attainments play? This may be important given recent work by Chetty and Hendren (2017b, 2017c), which notes considerable variation in the prospects of social mobility across the country. The concept of relative deprivation (Runciman, 1966; Stouffer et al., 1949) suggests that social comparisons are made to a reference group in closer geographic proximity—often one’s neighbors—as opposed to one’s past (Messner & Tardiff, 1986). From this perspective, feelings of deprivation are strongest when one’s status is perceived to be lower than those in close proximity (e.g., Nieuwenhuis et al., 2017), which can result in negative outcomes such as crime and poor mental health (e.g., Hur & Nasar, 2014; Ross & Mirowsky, 1999, 2001). In contrast, when residents perceive their status to be similar to their neighbors, feelings of relative deprivation are weaker (e.g., Schieman & Pearlin, 2006).

Taken together, these perspectives suggest that a simultaneous consideration of intergenerational social mobility and contemporary neighborhood conditions may provide a more comprehensive set of comparisons upon which people assess their educational attainments and relative social standing. The present study examines the association between educational mobility and crime, and the degree to which this relationship is moderated by contemporary neighborhood characteristics in young adulthood. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), we hypothesize that contextual disadvantage will moderate the association between educational mobility and crime. Specifically, increases in crime associated with downward mobility are hypothesized to be strongest within affluent neighborhoods, and weakest within contexts where others in close proximity are disadvantaged.

Education, Educational Mobility, and Crime

Research suggests a strong, negative association between education and crime (see Machin, Marie, & Vujic, 2011; Payne & Welch, 2013). Years of education and pursuing postsecondary education have been found to reduce the risk of incarceration (Arum & Beattie, 1999; Arum & LaFree, 2008). Highly educated individuals are also more likely to experience other adult attainments shown to promote desistance (Crutchfield & Pitchford, 1997; Grogger, 1998; Jacob, 2011; Siennick & Osgood, 2008; Uggen, 1999; Van Der Geest, Bijleveld, & Blokland, 2011), including higher wages, job satisfaction, and opportunities for advancement (BLS, 2012; Cox, 2010; Uggen, 1999, 2000; Wadsworth, 2006; Webster, Stantion-Tindall, Duvall, Garrity, & Leukefeld, 2007). In addition, education is positively related to the prospects of marriage (Cherlin, 2010; Kaplan & Herbst, 2015).

Comparisons of educational attainments between parents and children in the United States reveal distinct patterns of continuity and mobility across the life course. First, the prospects of college are skewed in favor of those from affluent backgrounds (Crosnoe & Muller, 2014; Davis-Kean, 2005; DiPrete & Eirich, 2006; Hagan & Parker, 1999; Reeves & Howard, 2013). This suggests a high degree of cumulative advantage passed from one generation to the next (Elder, 1994, 1998; Merton, 1968; see also Smeeding, Erikson, & Jantti, 2011). In fact, the advantages of social class are so strong, and prospects of upward mobility are so poor, that a recent study of Baltimore children by Alexander, Entwisle, and Olson (2014) observed that only 4% of those from poor families went on to complete a postsecondary degree, compared with 45% from advantaged backgrounds.

Despite the fact that college enrollment continues to grow, increasing educational inequality means that the prospects of downward educational mobility are also rising. A report by the OECD (2016) showed that just over half of adults in the United States completed levels of education equivalent to those of their parents. Furthermore, as recently as 2012, the proportion of young adults experiencing downward educational mobility (24%) was nearly identical to those experiencing upward mobility (23%; OECD, 2016). The figure pertaining to downwardly mobile individuals is particularly concerning as this number falls within the bottom third of the industrialized world. These developments are explained in part by the rising costs of college in the United States and public disinvestment in higher education (Hout & Janus, 2011), as average investments in postsecondary education have soared to over US$60,000 per student (OECD, 2016).

That upward and downward educational trajectories may produce crime is motivated by classic mobility theorists, such as Sorokin (1927, 1959), who argued that mobility encourages psychological distress due to a change in norms. Although Sorokin originally suggested that any mobility would be stressful, scholars have emphasized that downward mobility is particularly daunting (Houle, 2011; Newman, 1988). Indeed, downward mobility has been shown to increase depression (Nicklett & Burgard, 2009) and reduce selfrated health (Tiffin, Pearce, & Parker, 2005). With this in mind, not completing college for those from families with educational resources would represent a loss of status with potential emotional and behavioral consequences.

Relative Deprivation and Neighborhood Disadvantage

In addition to assessing one’s attainments in comparison with the past (i.e., to parents), people are also likely to make contemporaneous social comparisons. For example, geographic variations in socioeconomic attainments and mobility may shape the way people assess their educational attainments (Blau & Blau, 1982; Burraston, McCutcheon, & Watts, 2017; Crosby, 1976; Leventhal, Dupéré, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Runciman, 1966; Stouffer et al., 1949; Tougas & Beaton, 2008). Indeed, neighbors are often the point of reference for studies based on the concept of relative deprivation, given the proximity and accessibility of these individuals (Allen & Wilder, 1977). From this perspective, evaluations of social standing largely depend on how one feels they are doing compared with the majority of their neighbors.

As applied to the present study, and to those with lower levels of educational attainments, two distinct scenarios may arise. First, educationally disadvantaged individuals may not feel deprived if others in close proximity are of similar social standing. In the commonly referenced words of Karl Marx (1847), “A house may be large or small; as long as the neighboring houses are likewise small, it satisfies all social requirement for a residence” (p. 42). Indeed, research has shown feelings of deprivation to be weaker when one believes their own social standing is relatively similar to the bulk of neighbors (Schieman & Pearlin, 2006).

However, increases in relative deprivation occur when one feels as though their achievements do not measure up to the majority of their neighbors. As Marx (1847) continued in his discussion of social comparisons,

“ … let there arise next to the little house a palace, and the little house shrinks to a hut … the occupant of the relatively little house will always find himself more uncomfortable, more dissatisfied, more cramped within his four walls” (p. 42)

In accordance with this, Nieuwenhuis and colleagues (2017) found that being poorer than most neighbors accentuated levels of depression and aggression. Other work shows worse health outcomes among residents of low socioeconomic status (SES) who live in high SES neighborhoods (Winkleby, Cubbin, & Ahn, 2006). Winkleby and colleagues (2006) attributed their findings to the stress associated with continuous reminders that one is poorer than most others in the neighborhood. Furthermore, research shows greater involvement in delinquency among low-income boys in affluent neighborhoods compared with their peers in concentrated disadvantage (Odgers, Donley, Caspi, Bates, & Moffitt, 2015). All told, when feelings of relative deprivation are strongest, they are associated with crime and other negative outcomes (Bernburg, Thorlindsson, & Sigfusdottir, 2009; Chamberlain & Hipp, 2015; Crosnoe, 2009; Geis & Ross, 1998; Hur & Nasar, 2014; Ross & Mirowsky, 1999, 2001; Ross, Mirowsky, & Pribesh, 2001; Stack, 1984; Stiles, Liu, & Kaplan, 2000).

The Present Study

This study seeks to integrate two streams of research—that is, intergenerational social mobility and relative deprivation—by examining how contemporary socioeconomic contexts (i.e., neighborhood disadvantage) moderate the association between educational mobility and crime. As a first study of its kind, the hypotheses are somewhat speculative in nature. On one hand, one might expect that neighborhood disadvantage would accentuate the negative consequences associated with downward mobility. From the perspective of social mobility, downward intergenerational mobility may lead to feelings of distress due to the loss of status, as well as the accumulation of financial stressors, which would likely be heightened by the lack of resources in the neighborhood. On the other hand, downwardly mobile individuals residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods may perceive that they are doing no worse than those around them, thus minimizing the consequences. This sort of protective evaluation is suggested by Wills’s (1981) concept of “downward comparisons,” through which individuals compare themselves with others experiencing hardship as a means of protecting well-being. As Newman (1988) observed in her ethnographic study of downward mobility, the economic recession of the 1980s shaped a common experience among the many facing economic adversity. Thus, the potential consequences often associated with downward mobility were minimized as fired workers attributed their lack of employment to the state of the economy as opposed to individual failures.

However, in the absence of a shared and disadvantaged community, those experiencing a loss in status may feel accountable for their educational failures, therefore resulting in strain, distress, and potentially crime. As education is strongly associated with neighborhood advantage (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001), the majority of individuals in affluent contexts possess educational resources, leaving those with lower education noticeably more disadvantaged. With this in mind, we speculate that downward mobility may be especially daunting when others in close geographical proximity are more advantaged. Downward mobility in the midst of neighborhood advantage may represent a subjective catastrophe, as such a situation would reflect a loss in status compared with one’s parents, as well as feelings of resentment resulting from upward comparisons with those in close proximity to oneself (see Festinger, 1954).

Data

We use data from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), which began as a study of adolescents in Grades 7 to 12 (in 1994–1995) in the United States, followed through the last data collection (Wave 4) in 2007–2008, when respondents were largely between 25 and 32 years of age. Of the 20,745 respondents from Wave 1, 14,738 (71%) were re-interviewed 1 year later (Wave 2). Follow-up interviews for Wave 3 and Wave 4 consisted of 15,197 (73%) and 15,701 (76%) of the participants from Wave 1, respectively. Add Health also provides contextual information at the census tract, county, and state level, with a wide variety of measures. These analyses draw on data from Waves 1 and 4.

Of the 15,701 respondents participating at both Waves 1 and 4, we first restrict our sample to respondents who are not missing on our dependent variable, measures of educational mobility, and who have a valid sample weight. This yields an analytic sample of 14,539 respondents. The majority of covariates have minimal missing data (i.e., less than 1%); exceptions are in the measures of parents’ occupation status and Add Health Picture Vocabulary Test Scores, where roughly 4% and 5% are missing, respectively. To address this, we use multiple imputation across five imputations via the “PROC MI” procedure in SAS 9.3.

Dependent Variable

Following others using Add Health (e.g., Demuth & Brown, 2004; Haynie, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2005; McGloin, 2009), involvement in crime is based on a sum of nine self-reported indicators at Wave 4. Questions ask how often respondents did each of the following in the last 12 months: deliberately damage property that did not belong to you; steal something worth more than US$50; go into a house or building to steal something; use or threaten to use a weapon to get something from someone; sell marijuana or other drugs; steal something worth less than US$50; take part in a physical fight where a group of your friends was against another group; get into a serious fight; and hurt someone badly enough in a physical fight that he or she needed care from a doctor or nurse. Each item is coded as 0 if the event never happened, 1 if the event happened 1 or 2 times, 2 if the event happened 3 or 4 times, and 3 if the event happened 5 or more times.

Educational Pathways

Respondents’ education at Wave 4 is based on self-reports of the highest degree completed. Education is coded as 1 for those who attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, while any education less than a bachelor’s degree is coded as 0. This same coding scheme is then used for measuring the educational attainments of the respondent’s parents at Wave 1.1 With these measures, mobility is operationalized via four dichotomous indicators reflecting intergenerational educational pathways. For instance, respondents with less than a bachelor’s degree whose parents also achieved less than a bachelor’s degree reflect stability at low levels of education (i.e., low-low) while respondents who achieve at least a bachelor’s degree from parents with less than a bachelor’s degree reflect upward mobility (i.e., low-high). Educational pathways denoting stability at high levels of education (i.e., high-high), as well as downward mobility (i.e., high-low), complete the operationalization of educational mobility. Educational stability at low levels (i.e., low-low) is used as the omitted category in the multivariate analyses.

Neighborhood disadvantage at Wave 4 is constructed from the Add Health contextual data and based on the American Community Survey (ACS). Due to the sampling design and size, one concern with measures from the ACS is that they tend to have large margins of errors (Folch David, Arribas-Bel, Koschinsky, & Spielman, 2016; Spielman, Folch, & Nagle, 2014). However, the random error distribution within each measure is independent of one another; therefore, composite measures result in an average error close to zero (Spielman & Singleton, 2015). With this in mind, we use a composite indicator based on the average of five census tract measures tapping socioeconomic disadvantage, including proportions of adults unemployed, families below poverty, households receiving public assistance, female-headed households, and respondents below 25 years without a bachelor’s degree (Cronbach’s α = .81; see Ross & Mirowsky, 2001). We also include neighborhood disadvantage at Wave 1, which is constructed in a comparable manner as disadvantage at Wave 4 (α = .91). Each original item ranges from 0.00 to 1.00; thus, we multiply our final measures by 100 so that a unit-increase is associated with a 1 percentage point increase in neighborhood disadvantage.

Demographic controls consist of a dichotomous indicator of sex (with male coded as 1 and female coded as 0), five mutually exclusive measures of race and ethnicity, including non-Hispanic White (reference), non-Hispanic Black, of Hispanic origin, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic other race, as well as a measure of age. A control for whether respondents reported living with both of their biological parents at Wave 1 is also incorporated.

We control for potential selection into educational pathways with several measures from Wave 1. Delinquency is constructed in the same manner as the dependent variable, and is used to control for stable differences in crime between respondents. Grade point average (GPA) is based on the average of their self-reported grades in history, math, and science courses. A three-item measure of education-related low self-control is based on the average of questions asking adolescents how often since school started this year (ranging from never to everyday) they had trouble: getting along with your teachers, paying attention in school, and getting your homework done (Cronbach’s α = .68). A continuous measure of parents’ occupational status is included (see Ford, Bearman, & Moody, 1999). Respondents’ scores on the Add Health Picture Vocabulary test (AHPVT) is based on a 78-item abridged version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised, which is standardized and centered around 100 (Halpern, Joyner, Udry, & Suchindran, 2000).

We include several adult status characteristics measured at Wave 4. First, we control for county-level crime rates (per 100,000), which is based on the information from the Uniform Crime Report (UCR). Familial transitions are evaluated with a series of dichotomous measures, including being married with and without children, cohabiting with and without children, and being single with and without children (being married with children is the reference category). Respondents’ labor force participation is assessed with measures indicating a respondent is unemployed, disabled or sick, currently a student, retired or homemaker, and active in the military (being employed is the reference category). We include a control for economic problems, which is measured by counting how many of the following six events happened during the last 12 months: you went without phone service due to a lack of money, you did not pay full rent or mortgage due to a lack of money, you were evicted from your apartment or house due to a lack of payments, you did not pay the full amount of utility bills due to a lack of money, you had services from the gas or electric company turned off, and you worried food would run out due to a lack of money. Finally, an indicator for respondents who received any public assistance, welfare payments, or food stamps (since Wave 3) is incorporated.

Analytic Strategy

With respondents clustered in neighborhoods at Wave 1 and a dependent measure of skewed variability (skewness = 5.99), we use multilevel negative binomial regression models in SAS 9.3., via the “PROC GLIMMIX” procedure. Negative binomial regression is best suited for a dependent measure with a large number of zeros (i.e., respondents who did not engage in any crime), which is the case here. Our analytic sample consists of 14,539 respondents nested within 1,965 neighborhoods, roughly 7.4 respondents per tract. We include Wave 1 disadvantage as a neighborhood-level variable, and all other controls as individual-level covariates.

Bivariate Relationships

Table 1 displays the means for each educational pathway group. As expected, those who achieve a bachelor’s degree whose parents have similar educational levels (i.e., the high-high group) come from advantaged neighborhoods, have highest GPAs and AHPVT scores, and have parents with the highest occupational prestige. Moreover, respondents who achieve less than a bachelor’s degree whose parents are highly educated (i.e., the high-low group) report significantly more delinquency compared with respondents with a bachelor’s degree from families with educational resources, and have one of the highest averages of low self-control.2

Table 1.

Means and Proportions by Educational Mobility.

| High-high | High-low | Low-high | Low-low | Total sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crime | 0.214 | 0.497 | 0.170 | 0.432 | 0.373 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage (Wave 4) | 17.746 | 21.338 | 20.031 | 23.684 | 21.696 |

| Male | 0.475 | 0.580 | 0.410 | 0.514 | 0.507 |

| White (Reference) | 0.782 | 0.693 | 0.688 | 0.626 | 0.676 |

| Black | 0.101 | 0.164 | 0.133 | 0.181 | 0.157 |

| Hispanic | 0.048 | 0.090 | 0.120 | 0.156 | 0.119 |

| Asian | 0.057 | 0.035 | 0.046 | 0.018 | 0.032 |

| Other | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.018 | 0.016 |

| Age | 28.824 | 28.820 | 29.114 | 28.990 | 28.941 |

| Lived with biological parents | 0.763 | 0.565 | 0.626 | 0.468 | 0.561 |

| Delinquency | 1.221 | 2.088 | 1.145 | 2.149 | 1.847 |

| GPA | 3.339 | 2.601 | 3.215 | 2.444 | 2.731 |

| Low self-control | 0.980 | 1.211 | 0.914 | 1.190 | 1.123 |

| Parent(s) occupation | 4.393 | 3.888 | 2.911 | 2.363 | 3.100 |

| AHPVT | 110.029 | 102.513 | 106.023 | 96.958 | 101.525 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage (Wave 1) | 18.391 | 21.480 | 22.178 | 24.606 | 22.557 |

| Crime rate (per 100,000) | 543.314 | 550.158 | 530.348 | 541.641 | 542.293 |

| Married with kids (Reference) | 0.202 | 0.290 | 0.269 | 0.312 | 0.282 |

| Married no kids | 0.217 | 0.091 | 0.201 | 0.069 | 0.116 |

| Cohabiting with kids | 0.013 | 0.078 | 0.041 | 0.119 | 0.082 |

| Cohabiting no kids | 0.136 | 0.116 | 0.132 | 0.090 | 0.108 |

| Single with kids | 0.021 | 0.084 | 0.038 | 0.125 | 0.088 |

| Single no kids | 0.411 | 0.341 | 0.320 | 0.285 | 0.323 |

| Employed | 0.875 | 0.809 | 0.882 | 0.792 | 0.821 |

| Unemployed | 0.030 | 0.055 | 0.033 | 0.085 | 0.063 |

| Disabled/sick | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.014 |

| Student | 0.040 | 0.033 | 0.031 | 0.024 | 0.030 |

| Retired/homemaker | 0.028 | 0.048 | 0.029 | 0.064 | 0.050 |

| Military | 0.018 | 0.036 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.022 |

| Economic problems | 0.135 | 0.556 | 0.237 | 0.708 | 0.517 |

| Welfare | 0.063 | 0.239 | 0.114 | 0.342 | 0.244 |

| Sample size | 3,025 | 3,082 | 1,666 | 6,766 | 14,539 |

Note. GPA = grade point average; AHPVT = Add Health Picture Vocabulary test.

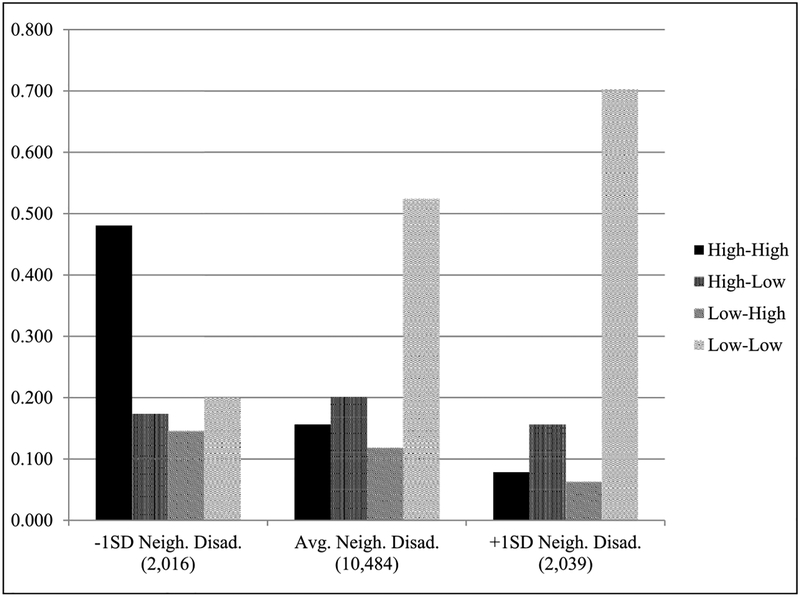

To ensure that each mobility group is sufficiently observed across the spectrum of neighborhoods, we next examine the proportion of educational pathways by different levels of disadvantage at Wave 4 (Figure 1). Not surprisingly, the majority of respondents in disadvantaged neighborhoods (i.e., one standard deviation above the mean) are intergenerationally stable at low levels of education. Similarly, nearly 50% of respondents who end up in affluent neighborhoods (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean) are those in the high-high group. Nevertheless, there are also relatively large representations of respondents off the main diagonal, such as the low-low group, which composes about 20% of the more advantaged neighborhoods. Perhaps most notable is the downwardly mobile, which are fairly evenly distributed across neighborhoods.

Figure 1.

Proportion of educational pathways by neighborhood disadvantage at Wave 4.

Multivariate Models

Table 2 presents the coefficients from the multilevel negative binomial regression models.3 Coefficients from Table 2 can be interpreted as a percentage change in the expected crime count for a one-unit change in the independent variable by computing 100 × (exp[bkxk]j − 1). For instance, in Model 1, relative to stability at low levels of education, upward mobility (i.e., low-high) is associated with decreases in crime of 100 × (exp[−.715] − 1) roughly 51%. Conversely, downward mobility from high to low levels of education increases the expected crime count by 100 × (exp[.159] − 1) approximately 17%. Neighborhood disadvantage at Wave 4 is also positively associated with crime, as a unit increase in disadvantage increases crime by roughly 2%.

Table 2.

Multilevel Negative Binomial Regression Analyses Predicting Crime.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-High | −0.663 (.082)*** | −0.702 (.087)*** | −0.554 (.096)*** | −0.438 (.096)*** |

| High-low | 0.IS9 (.066)* | 0.185 (.066)** | 0.179 (.069)** | 0.128 (.068)† |

| Low-High | −0.715 (.099)*** | −0.676 (.101)*** | −0.502 (.102)*** | −0.342 (.102)** |

| Neighborhood disadvantage (Wave 4)a | 0.023 (.004)*** | 0.034 (.006)*** | 0.031 (.006)*** | 0.018 (.006)** |

| High-High × Wave 4 Disadvantage | −0.032 (.012)** | −0.025 (.012)* | −0.011 (.011) | |

| High-Low × Wave 4 Disadvantage | −0.029 (.010)** | −0.024 (.010)* | −0.020 (.009)* | |

| Low-High × Wave 4 Disadvantage | <0.001 (.016) | <0.001 (.016) | 0.015 (.016) | |

| Delinquency | 0.101 (.009)*** | 0.095 (.008)*** | ||

| GPAa | −0.031 (.036) | −0.013 (.037) | ||

| Low self-control | 0.225 (.036)*** | 0.199 (.036)*** | ||

| Parent(s) occupation | 0.005 (.019) | 0.010 (.018) | ||

| Lived with biological parents | −0.229 (.054)*** | −0.114 (.053)* | ||

| AHPVTa | 0.009 (.002)*** | 0.008 (.002)*** | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage (Wave l)a | −0.008 (.005) | −0.005 (.005) | ||

| Crime rate (per 100,000) | <0.001 (<.001) | |||

| Married no kids | 0.299 (.107)** | |||

| Cohabiting with kids | 0.611 (.101)*** | |||

| Cohabiting no Kids | 1.030 (.092)*** | |||

| Single with kids | 0.823 (.106)*** | |||

| Single no kids | 1.064 (.074)*** | |||

| Unemployed | 0.165 (.090)† | |||

| Student | 0.051 (.144) | |||

| Military | −0.364 (.176)* | |||

| Disabled/sick | 0.458 (.205)* | |||

| Retired/homemaker | −0.344 (.156)* | |||

| Economic problems | 0.245 (.021)*** | |||

| Welfare | 0.346 (.063)*** | |||

| Male | 1.134 (.053)*** | 1.133 (.053)*** | 0.935 (.053)*** | 1.019 (.059)*** |

| Black | 0.247 (.080)** | 0.242 (.079)** | 0.329 (.084)*** | 0.125 (.083) |

| Hispanic | −0.035 (.085) | −0.035 (.085) | −0.030 (.086) | −0.079 (.085) |

| Asian | −0.397 (.159)* | −0.408 (.159)* | −0.233 (.154) | −0.349 (.152)* |

| Other | −0.069 (.201) | −0.078 (.201) | −0.054 (.198) | −0.196 (.194) |

| Agea | −0.135 (.015)*** | −0.136 (.015)*** | −0.140 (.015)*** | −0.105 (.014)*** |

| Constant | −1.818 (.063)*** | −1.846 (.064)*** | −2.241 (.092)*** | −3.376 (.126)*** |

| AIC | 19,087.660 | 19,080.700 | 18,711.470 | 18,232.430 |

| Model χ2 | 1,511.500*** | 1,537.420*** | 2,303.880*** | 3,313.960*** |

Note. Standard errors in parentheses. N = 14,539 respondents; 1,965 tracts. GPA = grade point average; AHPVT = Add Health Picture Vocabulary test; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

Centered.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

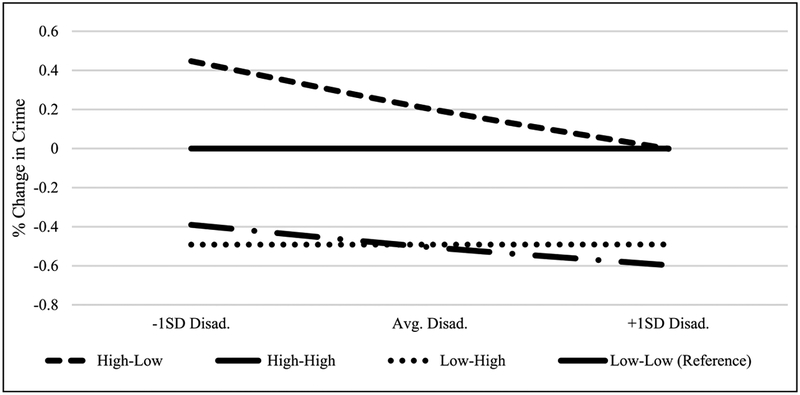

Central to our analysis is Model 2, which includes interactions between educational mobility and current neighborhood disadvantage. Two of three interaction terms are statistically significant, and in the direction hypothesized. Although all interactions are negative, they have distinct interpretations with respect to educational mobility. To aid in the interpretation, Figure 2 displays the changes in crime associated with each educational pathway at targeted levels of neighborhood disadvantage (i.e., average disadvantage, as well as one standard deviation above and below average disadvantage, respectively). As expected based on the positive coefficient attributed to the direct effect, downward mobility (i.e., the high-low group) is associated with increases in crime compared with stability at low levels of education, but the negative interaction term suggests that the association is weaker as neighborhood disadvantage increases. That is, the consequences associated with downward mobility are strongest when residing in an advantaged context, and weakest in a neighborhood of greater disadvantage. In fact, estimates are no longer statistically significant at 1 standard deviation above average disadvantage. By the same token, the negative interaction with intergenerational stability at high levels of education (i.e., the high-high group) and neighborhood disadvantage shows the benefits associated with this intergenerational trajectory are stronger as disadvantage increases.

Figure 2.

Effect of educational mobility on crime by neighborhood disadvantage.

Turning back to Table 2, the interactions are slightly attenuated once controls suspected to be correlated with both education and crime are included in the analyses (Model 3). Finally, Model 4 includes adult characteristics gathered from Wave 4, and the interaction associated with the high-low group and contextual disadvantage is reduced in magnitude by roughly 23%, although it retains statistical significance. Furthermore, the interaction between the high-high group and contextual disadvantage is no longer statistically significant in Model 4.

A fundamental concern in studies of social mobility is that observed effects may be driven by the attainments (i.e., whether one completes a postsecondary degree) and not mobility itself. As a further test, we thus stratified our sample by those with and without a college degree to see whether the pathway one takes to each attainment makes a difference (Table 3). Among those with a bachelor’s degree, the results suggest that the attainment itself is primarily what matters, as the crime-reducing benefits of education do not differ between the upwardly mobile and those intergenerationally stable at high levels of education. However, among those without a bachelor’s degree, our key results are reinforced, as downward mobility remains significantly associated with increases in crime compared with intergenerational stability at low levels of education. Furthermore, the consequences of downward mobility are again shown to be minimized as neighborhood disadvantage increases in young adulthood.

Table 3.

Crime Regressed on Educational Pathways Partitioned by Achieved Education.

| Variable | Bachelor’s degree | No degree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Low-Higha | −.070 (.142) | −.030 (.146) | ||

| High-Lowb | .144 (.069)* | .159 (.069)* | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage (Wave 4)c | .017 (.010)† | .01 1 (.01 1) | .022 (.005)*** | .029 (.006)*** |

| Low-High × Wave 4 Disadvantage | .020 (.019) | |||

| High-Low × Wave 4 Disadvantage | −.025 (.010)* | |||

| Constant | −2.954 (.281)*** | −2.988 (.283)*** | −2.179 (.099)*** | −2.191 (.098)*** |

| Model χ2 | 513.780*** | 516.120*** | 1,404.040*** | 1,434.600*** |

Note. Standard errors in parentheses. Models include controls from Model 3 in Table 2; 4,691 completed a bachelor’s degree by Wave 4, while the remaining 9,848 respondents did not have a degree.

Reference: High-High.

Reference: Low-Low.

Centered.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

This study considered the interactive relationship between intergenerational educational mobility, neighborhood disadvantage, and crime over the life course. Overall, results showed how contextual disadvantage—a prominent point of reference in studies of relative deprivation—moderates the relationship between educational mobility and crime. Downward educational mobility was associated with increases in crime, but the effect was weaker as neighborhood disadvantage increased. Moreover, intergenerational stability at high levels of education was associated with decreases in crime, with effects strongest in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Coupled with the concept of relative deprivation, we attribute the weaker effects of downward mobility in disadvantaged contexts to the role of social comparisons (Wills, 1981). For the purpose of enhancing well-being, making comparisons with individuals who are in similar socioeconomic standing has been shown to alleviate feelings of deprivation (Schieman & Pearlin, 2006). Indeed, with the majority of respondents in disadvantaged neighborhoods not possessing a college degree, the consequences associated with downward mobility may be minimized, as the absence of such resources is a shared experience (Newman, 1988). However, these findings are not intended to make light of the consequences associated with such a life course trajectory. Instead, we believe the null effects of downward educational mobility in disadvantaged contexts are another glaring reminder of how commonplace these prospects are becoming (Chetty et al., 2017a). With this and the growing concerns over downward educational mobility in the United States in mind (OECD, 2016), policy should continue to focus on improving college retention and completion. For example, some have proposed preparing students for the demands of postsecondary education earlier in their academic careers (Balemian, 2013; Tate et al., 2015), as well as addressing the issue of rising tuition (OECD, 2016).

One somewhat unexpected finding was that those on the most advantaged life course trajectory (i.e., the high-high group) fared best in neighborhoods of greater disadvantage. We speculate that this may be attributable to the competitive advantage those with educational resources have over the majority of other residents. Education is highly correlated with both marriage (Cherlin, 2010; Kaplan & Herbst, 2015) and employment (Siennick & Osgood, 2008), and the potential for achieving such turning points may be greater in neighborhoods where most residents do not possess educational resources. Consistent with this speculation, the interaction between intergenerational stability at high levels of education and neighborhood disadvantage was fully attenuated with the inclusion of family formation and employment statuses. Future research to further unpack these relationships, however, is needed.

Our results reinforce the growing importance of a college degree, as higher education was largely associated with decreases in crime regardless of intergenerational pathways or neighborhood context. In fact, first-generation college students (i.e., the low-high group) exhibited comparable levels of crime with the intergenerationally stable college-educated group. Indeed, first-generation students are of growing importance, as their college enrollment continues to rise (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2016). At the same time, given that these students are often from families of low socioeconomic standing (Cho, Hudley, Lee, Barry, & Kelly, 2008), they are most likely to accumulate debt from their college endeavors (Houle, 2014). With the potential burden associated with debt across the life course (Houle & Warner, 2017), future research should consider the association between first-generation students and crime. Moreover, given that the prospects of finishing college for this group are quite modest (Fitzgerald & Delaney, 2002), future research should also consider differences in crime between first-generation students who complete their education and those who do not.

With so few studies in existence, our research is important for advancing the study of social mobility and crime. Just recently, Savolainen and colleagues (2014) noted, “We are not aware of a single prior study that examines individual differences in criminal behavior from the perspective of intergenerational social mobility” (p. 165). Although the authors found little support for their hypotheses pertaining to educational mobility and crime, one other study has observed differences in crime in relation to mobility (Swisher & Dennison, 2016). Thus, we contend that researchers should continue to examine social mobility and test the robustness of the few studies on this topic in criminological research.

Studies of relative social standing should continue to investigate multiple points of reference to confirm these findings and progress toward a more comprehensive understanding of how one interprets their socioeconomic rank across the life course. Furthermore, research should examine other levels of geographic context aside from the neighborhood (or tract) level employed in the present study, as prior studies have suggested that points of reference can extend beyond one’s tract to adjacent neighborhoods and citywide comparisons (e.g., Chamberlain & Hipp, 2015; Firebaugh & Schroeder, 2009; Mears & Bhati, 2006).

Limitations

A few limitations in these analyses should be noted. First, data from Add Health are school-based; therefore, some of the individuals who were most prone to downward educational mobility and/or crime are likely underrepresented, either due to dropping out of school or not being present on the day of interviews. Moreover, given that achieved education and neighborhood disadvantage are measured concurrently with the dependent variable, we are cautious in interpreting the findings as causal. Measures of achieved education are available at Wave 3 in Add Health, though such an approach results in biased measures of downward educational mobility, as respondents are only 18 to 26 years old during this wave. This attenuates the timeframe for respondents to complete postsecondary education and achieve upward mobility. Furthermore, measuring the interaction between social mobility and contextual disadvantage simultaneously with the dependent measure has theoretical relevance given that a comparison of one’s current surroundings is said to promote distress and crime (e.g., Ross & Mirowsky, 1999).

Conclusion

The growing demand for postsecondary education, as well as the rapid increase in economic inequality, suggest the potential for downward intergenerational mobility has never been greater. Yet, to the extent that such a pathway is associated with crime has been shown here to also depend on one’s socioeconomic context during adulthood. It is hoped that these findings contribute to future research examining the association between education, relative social standing, and crime across the life course.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by Grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website. No direct support was received from Grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author Biographies

Christopher R. Dennison is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. His research examines correlates of crime across the life course, with a particular focus on the criminogenic implications of social mobility. Recent research examines antisocial behavior among first- and continue-generation college students, and how this affects graduation.

Raymond R. Swisher is professor of Sociology at Bowling Green State University. His research focuses on risk factors in the lives of low income families, such as neighborhood poverty, exposure to violence, and parental incarceration, and their relationships to crime, delinquency, and well being. Recent research has investigated the relationship between educational mobility, neighborhood mobility, and crime.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

The only difference between the educational measures for respondents and parents is that parents’ education is based on the highest attainment of either parent.

Bivariate significance tests are based on an ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons of means.

A consideration of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the model chi-square is used for deciding on model fit.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, & Olson LS (2014). The long shadow: Family background, disadvantaged urban youth, and the transition to adulthood. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Allen VL, & Wilder DA (1977). Social comparison, self-evaluation, and conformity to the group In Suls JM & Miller RL (Eds.), Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives (pp. 187–200). Washington, DC: Hemisphere. [Google Scholar]

- Arum R, & Beattie IR (1999). High school experience and the risk of adult incarceration. Criminology, 37, 515–539. [Google Scholar]

- Arum R, & LaFree G (2008). Educational attainment, teacher-student ratios, and the risk of adult incarceration among U.S. birth cohorts since 1910. Sociology of Education, 81, 397–421. [Google Scholar]

- Balemian K (2013). First generation students: College aspirations, preparedness and challenges. Retrieved from https://research.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/2013/8/presentation-apac-2013-first-generation-college-aspirations-preparedness-challenges.pdf

- Bernburg JG, Thorlindsson T, & Sigfusdottir ID (2009). Relative deprivation and adolescent outcomes in Iceland: A multilevel test. Social Forces, 87, 1223–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Blau PM, & Blau JR (1982). The cost of inequality: Metropolitan structure and violent crime. American Sociological Review, 47, 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012). The recession of 2007–2009. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015). Employment projections. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf

- Burraston B, McCutcheon JC, Watts SJ (2017). Relative and absolute deprivation’s relationship with violent crime in the United States: Testing an interaction effect between income inequality and disadvantage. Crime & Delinquency, 64, 542–560. doi: 10.1177/0011128717709246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Education and the Workforce. (2013). Recovery: Job growth and educational requirements through 2020. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Recovery2020.FR_.Web_.pdf

- Chamberlain AW, & Hipp JR (2015). It’s all relative: Concentrated disadvantage within and across neighborhoods and communities, and the consequences for neighborhood crime. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 403–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Grusky D, Hell M, Hendren N, Manduca R, & Narang J (2017a). The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science, 356, 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, & Hendren N (2017b, May). The effects of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects (Working Paper No. 23001). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, & Hendren N (2017c, May). The effects of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility II: County-level estimates (Working Paper No. 23002). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Hudley C, Lee S, Barry L, & Kelly M (2008). Roles of gender, race, and SES in the college choice process among first-generation and nonfirst-generation students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cox R (2010). Crime, incarceration, anti-employment in light of the great recession. The Review of Black Political Economy, 37, 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F (1976). A model of egotistic relative deprivation. Psychological Review, 83, 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2009). Low-income students and the socioeconomic composition of public high schools. American Sociological Review, 74, 709–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, & Muller C (2014). Family socioeconomic status, peers, and the path to college. Social Problems, 61, 602–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield RD, & Pitchford SR (1997). Work and crime: The effects of labor stratification. Social Forces, 76, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kean PE (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth S, & Brown SL (2004). Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: The significance of parental absence versus parental gender. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 41, 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- DiPrete TA, & Eirich GM (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP (1989). Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence and Victims, 4, 79–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh G, & Schroeder MB (2009). Does your neighbor’s income affect your happiness? American Journal of Sociology, 115, 805–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald BK, & Delaney JA (2002). Educational opportunity in America In Heller DE (Ed.), Conditions of access: Higher education for lower-income students (pp. 3–24). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Folch David C, Arribas-Bel D, Koschinsky J, & Spielman SE (2016). Spatial variation in the quality of American community survey estimates. Demography, 53, 1535–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Bearman PS, & Moody J (1999). Foregone health care among adolescents. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 2227–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis KJ, & Ross CE (1998). A new look at urban alienation: The effect of neighborhood disorder on perceived powerlessness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 232–246. [Google Scholar]

- Grogger J (1998). Market wages and youth crime. Journal of Labor Economics, 16, 756–791. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, & Parker P (1999). Rebellion beyond the classroom: A life-course capitalization theory of the intergenerational causes of delinquency. Theoretical Criminology, 3, 59–285. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Joyner K, Udry RJ, & Suchindran C (2000). Smart teens don’t have sex (or kiss much either). Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, & Longmore MA (2005). Adolescent romantic relationship and delinquency involvement. Criminology, 43, 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Houle JN (2011). The psychological impact of intragenerational social class mobility. Social Science Research, 40, 757–772. [Google Scholar]

- Houle JN (2014). Disparities in debt: Parents’ socioeconomic status and young adult student loan debt. Sociology of Education, 87, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Houle JN, & Warner C (2017). Into the red and back to the nest? Student debt, college completion, and returning to parental home among young adults. Sociologyof Education, 90, 89–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout M, & Janus A (2011). Educational mobility in the United States since the 1930s In Duncan GJ & Mornane RJ (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality schools and children’s life chances (pp. 167–187). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hur M, & Nasar JL (2014). Physical upkeep, perceived upkeep, fear of crime and neighborhood satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob A (2011). Economic theories of crime and delinquency. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 21, 270–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, & Herbst A (2015). Stratified patterns of divorce: Earnings, education, and gender. Demographic Research, 32, 949–982. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupéré V, & Brooks-Gunn J (2009). Neighborhood influences on adolescent development In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 411–443). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Machin S, Marie O, & Vujić S (2011). The crime reducing effect of education. The Economic Journal, 121, 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Marx K (1847). Wage labour and capital. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Wage_Labour_and_Capital.pdf

- McGloin JM (2009). Delinquency balance: Revisiting peer influence. Criminology, 47, 439–477. [Google Scholar]

- Mears DP, & Bhati AS (2006). No community is an island: The effects of resource deprivation on urban violence in spatially and socially proximate communities. Criminology, 44, 509–548. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, & Tardiff K (1986). Economic inequality and levels of homicide: An analysis of urban neighborhoods. Criminology, 24, 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Digest of education statistics, 2014. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98

- Newman KS (1988). Falling from grace: The experience of downward mobility in the American middle class. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklett EJ, & Burgard SA (2009). Downward social mobility and major depressive episodes among Latino and Asian-American immigrants to the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis J, Van Ham M, Yu R, Branje S, Meeus W, & Hooimeijer P (2017). Being poorer than the rest of the neighborhood: Relative deprivation and problem behavior of youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1891–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Donley S, Caspi A, Bates CJ, & Moffitt TE (2015). Living alongside more affluent neighbors predicts greater involvement in antisocial behavior among low-income boys. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2016). Education at a glance 2016. Retrieved from http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/education-at-a-glance-2016_eag-2016-en#.WRzZ3twpBpg

- Payne AA, & Welch K (2013). Restorative justice in schools: The influence of race on restorative discipline. Youth and Society, 47, 539–564. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RV, & Howard K (2013). The glass floor: Education, downward mobility, and opportunity hoarding. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/glass-floor-downward-mobility-equality-opportunity-hoarding-reeves-howard.pdf

- Ross CE, & Mirowsky J (1999). Disorder and decay: The concept and measurement of perceived neighborhood disorder. Urban Affairs Review, 34, 412–432. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, & Mirowsky J (2001). Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 258–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, & Pribesh S (2001). Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review, 66, 568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Runciman WG (1966). Relative deprivation and social justice: A study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth century England. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, & Laub JH (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen J, Aaltonen M, Merikukk M, Paananen R, & Kissler M (2014). Social mobility and crime: Evidence from a total birth cohort. British Journal of Criminology, 55, 164–183. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, & Pearlin LI (2006). Neighborhood disadvantage, social comparisons, and the subjective assessment of ambient problems among older adults. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69, 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Siennick SE, & Osgood WD (2008). A review of research on the impact on crime of transitions to adult roles In Liberman A (Ed.), The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 161–187). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Smeeding T, Erikson R, & Jantti M (2011). Persistence, privilege, and parenting: The comparative study of intergenerational mobility. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin PA (1927). Social mobility. New York, NY: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin PA (1959). Social and cultural mobility. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spielman SE, Folch D, & Nagle N (2014). Patterns and causes of uncertainty in the American community survey. Applied Geography, 46, 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman SE, & Singleton A (2015). Studying neighborhoods using uncertain data from the American community survey: A contextual approach. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105, 1003–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S (1984). Income inequality and property crime. Criminology, 22, 229–257. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles BL, Liu X, & Kaplan HB (2000). Relative deprivation and deviant adaptations: The mediating effects of negative self-feelings. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 37, 64–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer SA, Lumsdaine AA, Lumsdaine MH, Williams RM Jr., Smith MB, & Janis IR Jr. (1949). The American soldier: Combat and its aftermath (Vol. II). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher RR, & Dennison CR (2016). Educational pathways and change in crime between adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53, 840–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate KA, Fouad NA, Marks LR, Young G, Guzman E, & Williams EG (2015). Underrepresented first-generation, low-income college students’ pursuit of a graduate education: Investigating the influence of self-efficacy, coping efficacy, and family influence. Journal of Career Assessment, 23, 427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin PA, Pearce MS, & Parker L (2005). Social mobility over the life course and self-reported mental health at age 50: Prospective cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59, 870–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougas F, & Beaton AM (2008). Personal relative deprivation: A look at the grievous consequences of grievance. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen C (1999). Ex-offenders and the conformist alternative: A job quality model of work and crime. Social Problems, 46, 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen C (2000). Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: A duration model of age, employment, and recidivism. American Sociological Review, 65, 529–546. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Geest VR, Bijleveld CCJH, & Blokland AAJ (2011). The effects of employment on longitudinal trajectories of offending: A follow-up of high-risk youth from 18 to 32 years of age. Criminology, 49, 1195–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth T (2006). The meaning of work: Conceptualizing the deterrent effect of employment on crime among young adults. Sociological Perspectives, 49, 343–368. [Google Scholar]

- Webster MJ, Stantion-Tindall M, Duvall JL, Garrity TF, & Leukefeld CG (2007). Measuring employment among substance-using offenders. Substance Use & Misuse, 42, 1187–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 245–271. [Google Scholar]

- Winkleby M, Cubbin C, & Ahn D (2006). Effect of cross-level interaction between individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on adult mortality rates. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 2145–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]