Abstract

Extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) represent a significant public health concern globally and are recognized by the World Health Organization as pathogens of critical priority. However, the prevalence of ESBL-PE in food animals and humans across the farm-to-plate continuum is yet to be elucidated in Sub-Saharan countries including Cameroon and South Africa. This work sought to determine the risk factors, carriage, antimicrobial resistance profiles and genetic relatedness of extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) amid pigs and abattoir workers in Cameroon and South Africa. ESBL-PE from pooled samples of 432 pigs and nasal and hand swabs of 82 humans were confirmed with VITEK 2 system. Genomic fingerprinting was performed by ERIC-PCR. Logistic regression (univariate and multivariate) analyses were carried out to identify risk factors for human ESBL-PE carriage using a questionnaire survey amongst abattoir workers. ESBL-PE prevalence in animal samples from Cameroon were higher than for South Africa and ESBL-PE carriage was observed in Cameroonian workers only. Nasal ESBL-PE colonization was statistically significantly associated with hand ESBL-PE (21.95% vs. 91.67%; p = 0.000; OR = 39.11; 95% CI 2.02–755.72; p = 0.015). Low level of education, lesser monthly income, previous hospitalization, recent antibiotic use, inadequate handwashing, lack of training and contact with poultry were the risk factors identified. The study highlights the threat posed by ESBL-PE in the food chain and recommends the implementation of effective strategies for antibiotic resistance containment in both countries.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, Enterobacteriaceae, ESBL, food chain, one health

1. Introduction

Enterobacteriaceae are rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacteria, fermenting glucose, usually motile and facultative anaerobes, with the majority of genera being natural residents of gastrointestinal tract of animals, humans and some of them can be found in the environment [1,2]. The extensive use of third and fourth generation cephalosporins in human and animal health, has led to the emergence of extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE). ESBL-PE represent a significant public health concern globally and have recently been classified by the World Health Organization as pathogens of critical priority in research [3].

Several studies have detected ESBL-PE in food animals, especially pigs, poultry and cattle and food products throughout the world and their transmission from livestock to humans in the farm-to-plate continuum has been evidenced [4,5]. However, the prevalence of ESBL-PE in food animals and humans across the farm-to-plate continuum is yet to be elucidated in Sub-Saharan countries including Cameroon and South Africa. It is therefore imperative to understand the epidemiology and determine the burden of ESBL-PE in food animals in order to highlight the threat posed by these resistant bacteria and provide evidence for decision-makers to implement effective prevention and containment measures of antibiotic resistance (ABR) in Cameroon and South Africa. The objectives of this study were thus to assess and compare the colonization, antibiotic resistance profiles and genetic relatedness of ESBL-PE among pigs and exposed workers and delineate risk factors of ESBL-PE carriage in humans in these countries.

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Characteristics

Altogether, 114 people were contacted in the five selected slaughterhouses and 83 (73%) workers agreed to participate in the study, with the response rate being higher in Cameroon (71%) than in South Africa (59%). Table 1 describes nasal and hand ESBL-PE carriage of workers in relation to individual, medical/clinical history and slaughterhouse-related characteristics.

Table 1.

Nasal and hand ESBL-PE carriage of workers in relation to personal, medical/clinical and slaughterhouse-related characteristics. Of 84 workers enrolled, one withdrew prior to the sample collection and six refused the nasal sampling, yielding a total of 83 hand and 77 nasal samples. A few workers could not recall precise information whilst other refused to answer some questions leading to missing information that was not considered in the analysis.

| Variables | Nasal Sample | Hand Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency n (%) | Prevalence ESBL-PE (%) | Overall p-Value | Frequency n (%) | Prevalence ESBL-PE (%) | Overall p-Value | |

| Personal characteristics | ||||||

| Country | ||||||

| Cameroon | 53 (69) | 67.92 | 0.000 | 53 (64) | 79 | 0.000 |

| South Africa | 24 (31) | 0 | 30 (36) | 0 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 9 (12) | 44.44 | 0.883 | 12 (12) | 41.67 | 0.503 |

| Male | 68 (88) | 47.06 | 71 (88) | 52.11 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| 21–30 | 31 (40) | 41.94 | 0.084 | 32 (39) | 46.88 | 0.063 |

| 31–40 | 26 (34) | 50 | 28 (34) | 42.86 | ||

| 41–50 | 13 (17) | 38.46 | 14 (17) | 71.43 | ||

| 51–60 | 5 (6) | 100 | 6 (7) | 83.33 | ||

| Above 60 | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (3) | 0 | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 4 (5) | 50 | 0.048 | 5 (6) | 40 | 0.032 |

| Primary school not achieved | 6 (8) | 50 | 7 (8) | 42.86 | ||

| Primary school | 34 (44) | 64.71 | 35 (42) | 71.43 | ||

| Secondary school | 27 (35) | 25.93 | 27 (33) | 37.04 | ||

| High school/university | 6 (8) | 33.33 | 8 (10) | 25 | ||

| Average monthly income (US $) | ||||||

| Below 55 | 8 (10) | 62.50 | 0.007 | 8 (14) | 62.5 | 0.004 |

| 55–110 | 14 (19) | 78.57 | 14 (29) | 85.71 | ||

| 110–165 | 12 (16) | 66.67 | 12 (17) | 58.33 | ||

| 165–220 | 10 (13) | 40 | 10 (17) | 70 | ||

| 220–275 | 20 (27) | 20 | 24 (10) | 25 | ||

| Above 275 | 11 (15) | 27.27 | 13 (12) | 30.77 | ||

| Relative working at hospital or with animals | ||||||

| Yes | 42 (55) | 64.29 | 0.001 | 44 (53) | 68.18 | 0.001 |

| No | 35 (45) | 25.71 | 39 (47) | 30.77 | ||

| Clinical factors | ||||||

| Recent hospitalization (within one year of sampling) | ||||||

| Yes | 21 (27) | 39.29 | 0.032 | 21 (25) | 71.43 | 0.027 |

| No | 56 (73) | 66.67 | 62 (75) | 43.55 | ||

| Nasal problem | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (14) | 36.36 | 0.456 | 11 (13) | 45.45 | 0.714 |

| No | 66 (86) | 48.48 | 72 (87) | 51.39 | ||

| Skin problem | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (18) | 28.57 | 0.132 | 14 (17) | 35.71 | 0.222 |

| No | 63 (82) | 50.76 | 69 (83) | 53.62 | ||

| Recent antibiotic use (month prior the sampling) | ||||||

| Yes | 38 (49) | 55.26 | 0.140 | 38 (64) | 71.05 | 0.001 |

| No | 39 (51) | 38.46 | 45 (36) | 33.33 | ||

| Slaughterhouse-related factors | ||||||

| Closeness of abattoir with house | ||||||

| Yes | 32 (42) | 40.63 | 0.363 | 14 (33) | 17 | 0.184 |

| No | 45 (58) | 51.11 | 28 (67) | 34 | ||

| Abattoir | ||||||

| SH001 | 21 (27) | 76.19 | 0.000 | 21 (25) | 85.71 | 0.000 |

| SH002 | 19 (25) | 36.84 | 19 (23) | 63.16 | ||

| SH003 | 13 (17) | 100 | 13 (16) | 92.31 | ||

| SH004 | 4 (5) | 0 | 10 (12) | 0 | ||

| SH005 | 20 (26) | 0 | 20 (24) | 0 | ||

| Principal activity or working area | ||||||

| Slaughterer | 34 (44) | 58.82 | 0.012 | 34 (41) | 58.82 | 0.000 |

| Transport of pig/pork | 5 (7) | 80 | 5 (6) | 80 | ||

| Wholesaler | 7 (9) | 28.57 | 7 (8) | 85.71 | ||

| Butcher | 5 (7) | 80 | 5 (6) | 80 | ||

| Retailer of viscera * | 7 (9) | 71.43 | 7 (8) | 85.71 | ||

| Retailer of grilled pork # | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 100 | ||

| Scalding of pigs | 3 (4) | 0 | 3 (4) | 0 | ||

| Evisceration | 8 (10) | 0 | 14 (17) | 0 | ||

| Transport of viscera/blood | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Veterinarian | 5 (7) | 20 | 5 (6) | 20 | ||

| Meat inspector | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Training to practice profession | ||||||

| Yes | 28 (36) | 3.57 | 0.000 | 34 (41) | 2.94 | 0.000 |

| No | 49 (64) | 71.43 | 49 (59) | 83.67 | ||

| Year in profession | ||||||

| [0–4] | 31 (43) | 35.48 | 0.356 | 31 (39) | 38.71 | 0.357 |

| [5–9] | 6 (8) | 66.67 | 8 (10) | 50 | ||

| [10–14] | 22 (30) | 50 | 24 (30) | 58.33 | ||

| Above 15 | 14 (19) | 57.14 | 16 (20) | 62.50 | ||

| Intensity of pig’s contact (rare, low, frequent, very frequent) | ||||||

| Always | 35 (45) | 51.43 | 0.348 | 35 (42) | 57.14 | 0.136 |

| Almost always | 32 (42) | 37.50 | 38 (46) | 39.47 | ||

| Sometimes | 10 (13) | 60 | 10 (12) | 70 | ||

| Contact with other animals during handling or various procedures of processing of animals at the abattoir | ||||||

| Yes | 38 (50) | 60.53 | 0.046 | 39 (48) | 69.23 | 0.004 |

| No | 38 (50) | 34.21 | 42 (52) | 35.71 | ||

| Intensity of contact with other animals | ||||||

| Always | 8 (21) | 87.50 | 0.025 | 8 (20) | 100 | 0.006 |

| Almost always | 9 (24) | 22.22 | 10 (26) | 30 | ||

| Sometimes | 17 (45) | 58.82 | 17 (44) | 70.59 | ||

| Rarely | 4 (10) | 100 | 4 (10) | 100 | ||

* retailer of viscera: street-vendor buying pig’s viscera from abattoir workers, performing manual cleaning in order to sells ready-to-eat meal; # retailer of grilled pork: street-vendor acquiring pork at the slaughterhouse in order to sells ready-to-eat grilled pork.

2.2. ESBL-PE Status in Humans

Out of the 53 workers sampled in Cameroon, 42 (79%) and 36 (68%) were colonized by hand and nasal ESBL-PE, respectively. The main species identified were E. coli, Enterobacter spp. and K. pneumoniae (Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, in South Africa, Enterobacteriaceae was not isolated from slaughterhouse workers.

Cameroonian isolates exhibited elevated resistance to ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefuroxime, cefuroxime-axetil, cefotaxime, ceftazidime and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Table 2) with no resistance observed against imipenem, ertapenem, meropenem and tigecycline (Table 2). The profiles AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX (34%) and AMP.AMC.TZP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.TMP/SXT (7%) were predominant in hand and nasal ESBL-E. coli, respectively, in humans in Cameroon (Table 3).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility results of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) isolated from pigs and humans.

| Antibiotics | Cameroon | South Africa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | Human | Pig | ||||

| MIC (µg/mL) Range | No. (%) Resistant Isolates | MIC (µg/mL) Range | No. (%) Resistant Isolates | MIC (µg/mL) Range | No. (%) Resistant Isolates | |

| Ampicillin | ≥32 | 126 (95) | ≤2–≥32 | 32(73) | ≥32 | 38 (100) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 4–≥32 | 54(40) | ≤2–≥32 | 8(18) | 8–16 | 2(5) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤4–≥128 | 24(18) | ≤4–64 | 2(5) | ≤4 | 0 |

| Cefuroxime | 4–≥64 | 124(93) | ≤1–≥64 | 19(43) | ≥64 | 38 (100) |

| Cefuroxime-axetil | 4–≥64 | 125(93) | ≤1–≥64 | 19(43) | ≥64 | 38 (100) |

| Cefoxitin | ≤4–≥64 | 10(7) | ≤4–≥64 | 3(7) | ≤4 | 0 |

| Cefotaxime | ≤1–≥64 | 118(88) | ≤1–≥64 | 14(32) | 4–≥64 | 38 (100) |

| Ceftazidime | ≤1–≥64 | 93(69) | ≤1–≥64 | 8(18) | ≤1–4 | 1 (3) |

| Cefepime | ≤0.5–≥64 | 6(4) | ≤1–≥64 | 2(5) | ≤1–4 | 1 (3) |

| Meropenem | ≤0.25 | 0 | ≤0.25 | 0 | ≤0.25 | 0 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.25 | 0 | ≤0.25 | 0 | ≤0.25 | 0 |

| Ertapenem | ≤0.5 | 0 | ≤0.5 | 0 | ≤0.5 | 0 |

| Amikacin | ≤2–16 | 11(8) | ≤2–16 | 1(2) | ≤2–16 | 1 (3) |

| Gentamicin | ≤1–≥16 | 43(32) | ≤1–≥16 | 3(7) | ≤1–≥16 | 7(18) |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–≥4 | 33(25) | ≤0.25–≥4 | 2(5) | ≤0.25 | 0 |

| Tigecycline | ≤0.5–2 | 0 | ≤0.5–1 | 0 | ≤0.5–1 | 0 |

| Nitrofurantoin | ≤16–64 | 0 | ≤16–128 | 1(2) | ≤16–64 | 0 |

| Colistin | ≤0.5 | 0 | ≤0.5–4 | 1(2) | ≤0.5–8 | 1(3) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤20–≥320 | 119 (89) | ≤20–≥320 | 22(50) | ≤20–≥320 | 36(95) |

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) strains isolated from humans.

| Bacteria | Resistance Profiles | Cameroon | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal, n (%) | Hand, n (%) | ||

| E. coli | AMP.AMC.TZP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.TMP/SXT | 1 (50) | 0 |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CAZ.CS | 0 | 1(8) | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX | 0 | 4(31) | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.GM.CIP.FEP | 0 | 1(8) | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.TZP | 0 | 1(8) | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX | 0 | 1(8) | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.FEP.TMP/SXT | 0 | 1(8) | |

| E. dissolvens | AMP.AMC.CXM.CXM-A.FOX.CTX.TMP/SXT | 1 (50) | 0 |

| S. sonnei | AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 0 | 1(8) |

| K. pneumoniae | AMP.AMC.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.TMP/SXT.GM.FT | 0 | 1(8) |

| AMP.AMC.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AN.GM.CIP | 0 | 1(8) | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 0 | 1(8) | |

| Grand Total | 2 (100) | 13 (100) | |

AMP: Ampicillin; AMC: Amoxicillin-clavulanate; TZP: Piperacillin-tazobactam; CXM: Cefuroxime; CXM-A: Cefuroxime-Acetyl; CTX: Cefotaxime; CAZ: Ceftazidime; TMP/SXT: Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole; FOX: Cefoxitin; GN: Gentamicin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; FEP: Cefepime; CS: Colistin.

2.3. Epidemiological Background of ESBL-PE in Pigs

Overall, the prevalence of ESBL-PE in the pooled nasal and rectal samples was 75% (108/144) and 71% (102/144), respectively (Table 4). At country-level, 42% (30/72) and 50% (36/72) ESBL-PE were detected in rectal and nasal pooled samples in South Africa respectively, whereas a 100% ESBL-PE prevalence was isolated in both specimen types in Cameroon (Table 1). In Cameroon, the main species identified were E. coli (61%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (25%) whereas in South Africa, E. coli was the sole Enterobacteriaceae species isolated in both types of samples (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 4.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) in pooled nasal and rectal samples.

| Characteristics | Nasal Samples | Rectal Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Pooled Samples, n (%) | Nasal ESBL, n (%) | Overall p-Value | Frequency Pooled Samples, n (%) | Rectal ESBL, n (%) | Overall p-Value | |

| Country | ||||||

| Cameroon | 72 (50) | 72 (100) | 0.000 | 72 (50) | 72 (100) | 0.000 |

| South Africa | 72 (50) | 36 (50) | 72 (50) | 30 (41.67) | ||

| Abattoir | ||||||

| SH001 | 43 (30) | 43 (100) | 0.000 | 43 (30) | 43 (100) | 0.000 |

| SH002 | 19 (13) | 19 (100) | 19 (13) | 19 (100) | ||

| SH003 | 10 (7) | 10 (100) | 10 (7) | 10 (100) | ||

| SH004 | 40 (28) | 19 (47.50) | 40 (28) | 9 (22.50) | ||

| SH005 | 32 (22) | 17 (53.13) | 32 (22) | 21 (65.63) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Sow | 79 (55) | 64 (81.01) | 0.066 | 79 (55) | 59 (74.68) | 0.262 |

| Boar | 65 (45) | 44 (67.69) | 65 (45) | 43 (66.15) | ||

| Time point | ||||||

| First | 42 (29) | 31 (73.81) | 0.149 | 42 (29) | 34 (80.95) | 0.050 |

| Second | 54 (38) | 45 (83.33) | 54 (38) | 40 (74.07) | ||

| Third | 48 (33) | 32 (66.67) | 48 (33) | 28 (58.33) | ||

ESBL-PE isolated from pigs exhibited high resistance to ampicillin, cefuroxime, cefuroxime-acetyl, cefotaxime, ceftazidime and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in both countries (Table 2). One South African isolate expressed high resistance to colistin (8 mg/L) and no resistance to ertapenem, meropenem, imipenem and tigecycline was observed. The majority of ESBL-producing E. coli isolated from pigs in both countries showed the resistance profile AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX in both type of samples (Table 5).

Table 5.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) detected from pigs.

| Bacteria | Resistance Profiles | No. Antibiotics | No. Classes | Cameroon | South Africa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal, n (%) | Rectal, n (%) | Nasal, n (%) | Rectal, n (%) | ||||

| E. coli | AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX | 5 | 2 | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | 0 | 29(94) |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 6 | 2 | 7 (12) | 11 (20) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.FEP | 7 | 2 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.GM.CIP | 8 | 4 | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.CIP | 7 | 3 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC | 8 | 3 | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.GM.CIP | 9 | 4 | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.TZP | 8 | 2 | 5 (8) | 5 (9) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.TZP.FOX.FEP.GM.CIP | 12 | 4 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.FEP.GM. | 8 | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CIP | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.CIP.AMC | 8 | 3 | 0 | 5 (9) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.GM | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.CIP.AMC.TZP | 9 | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.CIP.GM.TZP.FEP | 10 | 4 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.TMP/SXT.CAZ.FEP.AK.GM.CS | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.TMP/SXT.GM | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | |

| AMP.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.TMP/SXT.GM.AMC | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71) | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.CIP.GM.AMC.TZP | 10 | 4 | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| K. pneumoniae | AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.GM | 6 | 3 | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AK.GM.CIP.AMC | 10 | 4 | 0 | 6 (11) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CAZ.AMC.TZP | 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.GM.AMC.TZP | 9 | 3 | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AMC.TZP.AK.GM.CIP | 11 | 4 | 0 | 3(5) | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX | 5 | 2 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 6 | 2 | 4 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.GM | 7 | 3 | 8 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.GM.AMC.TZP | 9 | 3 | 4 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| K. ozaenae | AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ.AK.GM.CIP.AMC | 10 | 4 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | AMP.AMC.CXM.CXM-A.FOX.CTX.TMP/SXT | 7 | 2 | 4 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C. freundii | AMP.AMC.CXM.CXM-A.FOX.CTX.TMP/SXT | 7 | 2 | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. sonnei | AMP.CTX.CAZ.TMP/SXT | 4 | 2 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMP.TMP/SXT.CXM.CXM-A.CTX.CAZ | 6 | 2 | 4 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

AMP: Ampicillin; AMC: Amoxicillin-clavulanate; AK: Amikacin; CXM: Cefuroxime; CXM-A: Cefuroxime-acetyl; CTX: Cefotaxime; CAZ: Ceftazidime; CS: Colistin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; FEP: Cefepime; FOX: Cefoxitin; GM: Gentamicin; TMP/SXT: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TZP: Piperacillin-tazobactam.

2.4. Genotypic Relatedness

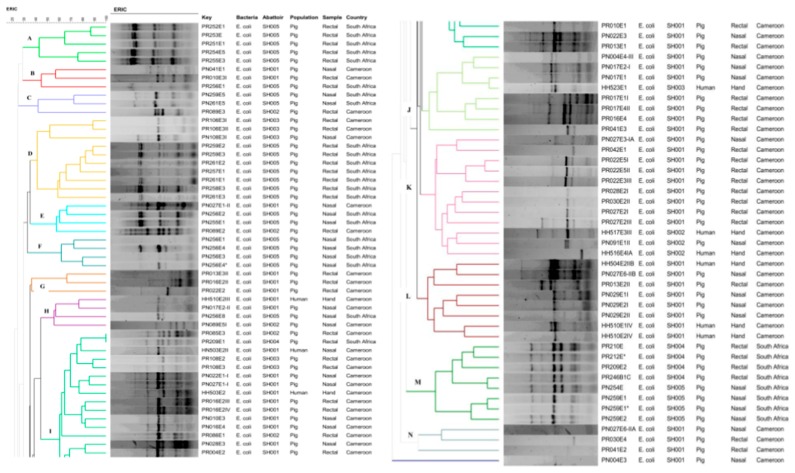

ERIC-PCR allowed the differentiation of the 93 E. coli into 14 clusters named alphabetically from A-N (Figure 1). A batch of isolates in cluster M (PR210, PR212E *, PR209E2, PR246B1C and PN254E), collected from pigs of abattoir SH004 and SH005 in South Africa was considered to be closely related. Moreover, great interest was observed in cluster I, where one pair of animal strains, PR085E3 and PR209E1 isolated in abattoirs SH002 and SH004 in Cameroon and South Africa, respectively, showed 100% similarity and were closely related with a human strain (HN503E2II) detected in abattoir SH001 in Cameroon (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genotypic relationship of ESBL-E. coli strains (n = 93) detected from exposed workers and pigs in Cameroon and South Africa. Dendogram generated by Bionumerics using UPGMA method and the Dice similarity coefficient.

2.5. Risk Factors of Human ESBL-PE Carriage

Table 6 shows the relationship between ESBL-PE carriage in workers and the foremost putative risk factors. Nasal and hand ESBL-PE colonization were univariately associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 39.11 (95% CI 2.02–755.72; p = 0.015). Other determinants, univariately associated with nasal and hand ESBL-PE carriage were previous hospitalization, recent antibiotic use, inadequate handwashing, occupation of relatives and year in the employment. The multivariate analysis reveals that nasal and hand ESBL-PE carriage in humans were associated with contact with other animals, particularly poultry with high statistical significance for both sample types (OR = 5.83, 95% CI 1.58–21.48, p = 0.008; vs. OR = 8.41, 95% CI 2.27–31.11, p = 0.001).

Table 6.

Predictors of nasal and hand ESBL-PE carriage among humans. Univariate and multivariate analysis (logistic regression).

| Variables | Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis | Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal ESBL-PE Carriage | Hand ESBL-PE Carriage | Nasal ESBL-PE Carriage | Hand ESBL-PE Carriage | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Abattoir | 0.43 (0.22–0.85) | 0.014 | 0.28 (0.15–0.55) | 0.000 | 2.54 (0.47–17.75) | 0.254 | 1.75 (0.19–15.54) | 0.615 |

| Gender | 1.11 (0.10–12.39) | 0.932 | 1.52 (0.20–11.38) | 0.682 | 8.74 (1.03–74.16) | 0.047 | 27.94 (1.68–463.05) | 0.020 |

| Educational level | 0.61 (0.39–0.94) | 0.024 | 0.72 (0.56–0.91) | 0.006 | ||||

| Monthly Income | 0.57 (0.36–0.89) | 0.014 | 0.60 (0.36–0.99) | 0.045 | 0.58 (0.35–0.97) | 0.039 | 0.76 (0.44–1.31) | 0.324 |

| Training | 0.01 (0.0003–0.79) | 0.038 | 0.006 (0.0005–0.0658) | 0.000 | 0.004 (0.00009–0.22) | 0.006 | 0.0008 (0.000008–0.09) | 0.003 |

| Principal Activities | 0.63 (0.50–0.78) | 0.000 | 0.63 (0.46–0.87) | 0.004 | ||||

| Occupation of relative a | 5.2 (1.46–18.56) | 0.011 | 4.82 (0.64–36.56) | 0.128 | 5.62 (1.02–30.82) | 0.047 | 3.58 (0.57–22.43) | 0.172 |

| Year in Profession | 1.40 (0.66–2.97) | 0.387 | 1.35 (0.68–2.69) | 0.398 | ||||

| Age | 1.09 (0.80–1.48) | 0.595 | 1.07 (0.61–1.89) | 0.817 | ||||

| Recent hospitalization b | 3.09 (1.26–7.59) | 0.014 | 3.24 (1.18–8.86) | 0.022 | 1.28 (0.24–6.87) | 0.769 | 0.57 (0.08–4.12) | 0.576 |

| Recent antibiotic use c | 1.97 (0.40–9.73) | 0.402 | 4.91 (1.20–20.03) | 0.027 | ||||

| Skin problem | 0.39 (0.17–0.89) | 0.025 | 0.48 (0.21–1.08) | 0.076 | ||||

| Nasal problem | 0.61 (0.29–1.28) | 0.192 | 0.79 (0.34–1.82) | 0.578 | ||||

| Protective working clothes | 0.04 (0.002–0.812) | 0.036 | 0.022 (0.002–0.258) | 0.002 | ||||

| Inadequate Handwashing | 4.71 (2.28–9.70) | 0.000 | 3.9 (1.01–15.01) | 0.048 | ||||

| Convenient handwashing | 0.08 (0.017–0.41) | 0.002 | 0.04 (0.013–0.145) | 0.000 | ||||

| Intensity of contact with pigs | 0.97 (0.50–1.87) | 0.920 | 0.96 (0.40–2.31) | 0.934 | ||||

| Contact with other animals | 2.95 (0.87–10.04) | 0.084 | 4.05 (1.42–11.53) | 0.009 | ||||

| Contact with poultry | 5.83 (1.58–21.48) | 0.008 | 8.41 (2.27–31.11) | 0.001 | 9.93 (1.37–71.63) | 0.023 | 24.22 (1.28–457.35) | 0.034 |

| Pig colonization Nasal ESBL (yes or No) | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.509 | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) | 0.313 | ||||

| Pig colonization Rectal ESBL (yes or No) | 1.03 (0.93–1.15) | 0.585 | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) | 0.273 | ||||

a: Relative working with food animals, food products or at hospital, b: Within one year prior the sampling date; c: Within one month prior the sampling date.

3. Discussion

Enterobacteriaceae and especially ESBL-PE, were acknowledged as critical priority antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) by the WHO and their emergence at the animal-human-environment interface presents a to serious and multifaceted public health concern globally [3]. This study investigated the carriage, risk factors, antibiotic resistance profiles and genetic relatedness of ESBL-PE isolated from apparently healthy pigs and occupationally exposed workers in Cameroon and South Africa.

The overall prevalence of human ESBL-PE carriage was 50% in hand and 45.75% in nasal samples. Comparable data was reported by Magoue et al. (2013) in Cameroon, where the prevalence of ESBL-PE faecal carriage was 45% in outpatients in the region of Adamaoua [6]. Our findings are nevertheless higher than that described by Dohmen et al. (2015) where a 27% prevalence of ESBL-PE carriage in faecal samples of people with daily exposure to pigs in Netherlands was described [7].

Our results are in contrast to a study of Fisher et al., (2016), where none of the 66.7% Enterobacteriaceae detected in the nares of participants were ESBL producers and where the authors concluded that nares were a negligible reservoir for colonization of ESBL-PE in pig’s exposed workers [8]. Our finding shows that the prevalence of ESBL-PE carriage in nasal samples substantially increased (8.33 vs. 91.67%; p < 0.001) and was statistically significantly correlated with their carriage on hand (OR 39.11; 95% CI 2.02–755.72; p = 0.015). In addition, nasal ESBL-PE carriage was associated with inappropriate handwashing with high statistical significance (OR 4.71; 95% CI 2.28–9.70; p < 0.001). This suggests, that nares might likely become reservoir of ESBL-PE when limited hygienic conditions prevail and biosecurity measures are not adequately implemented. It further reveals that, as with the transmission of nosocomial infections in hospital settings, hands constitute important vectors of ABR transmission in the food production industry and may not only drive the transfer from person-to-person but also the contamination of food products intended for the end consumer. Nasal ESBL-PE carriage reported herein might also be ascribed to airborne contamination as recently reported by Dohmen et al., (2017) who revealed that human CTX-M-gr1 carriage was statistically associated with presence of CTX-M-gr1 in dust (OR = 3.5, 95% CI = 0.6–20.9) and that inhalation of air might constitute another transmission route of ESBL-PE in the food chain [9].

The difference in the prevalence of ESBL-PE carriage in humans in both countries could be explained by the fact that South Africa has existing abattoir regulations in place and South African abattoirs were compliant with international food safety standard ISO 22000 and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans. In Cameroon, slaughterhouse/markets were principally low-grade, lacking in basic amenities, with sub-optimal sanitary conditions and limited or non-existent biosecurity measures. The Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations (FAO) report on abattoir facilities in Central African countries including Cameroon, already underlined the gaps in term of biosecurity measures in these settings [10]. Our findings, therefore, reinforce the importance of and the need to implement strict biosecurity procedures as when effective prevention and containment measures are implemented, the risk of ABR dissemination is reduced.

The overall prevalence of ESBL-PE in pigs was 71% and 75% in rectal and nasal pooled samples, respectively. The results are consistent with that reported by Le et al., (2015) in food animals and products in Vietnam where a 68.4% prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli was described [11]. They are however lower than that reported in pig farms in Germany, where 88.2% of ESBL-producing E. coli was detected [12] and higher than that reported in two other studies with prevalence ranging from 8.6 to 63.4% in food animals and food products in Netherlands, [13] and 8.4% in cattle in Switzerland [2].

The high rate of ESBL-PE carriage detected in both nasal and rectal samples in Cameroon may suggest that ESBL-PE are consistently widespread in food animals in Cameroon, disseminate in the farm-to-plate continuum and represent a grave public health threat in the country. Similarly, the ESBL-PE prevalence detected in pigs in South Africa is not surprising, especially because the use of antibiotics as growth promoter agents is legally allowed in the country [14]. These findings reveal gaps in the current state of knowledge about antibiotic use and ABR in food animals and suggests that the debate about ABR-related consequences in the farm-to-plate continuum is neglected in Cameroon and South Africa and should be more seriously considered in these countries. Additionally, our study revealed a high frequency (95%) of ESBL-producing E. coli, emphasizing the relevance of this indicator bacteria as a serious public health issue.

ERIC analysis demonstrated relative associations amongst human and animal isolates within and across countries. Some strains isolated in humans were highly related to those detected from pigs at similar or dissimilar abattoirs suggesting that the occurrence of ESBL-PE in humans may have an animal origin or vice-versa and that these bacteria may spread to humans via the food chain, allowing their dissemination to the global population. Although not providing evidence on the transmission dynamics of ESBL-PE, our results nevertheless show an epidemiological link amongst isolates from humans and animals.

Hospitalization, antibiotic use and contact with (food) animals are known risk factors for human ESBL-PE carriage [15]. Twenty-one abattoir workers or their family members had been admitted to a hospital within the year of the sampling. Of these, 39.29% evidenced nasal ESBL-PE carriage and 71.43% hand ESBL-PE colonization (Table 1). Likewise, the majority of workers who had used antibiotics within the month of the sampling were colonized by ESBL-PE in nares (55.26%) and hands (71.05%) (Table 1).

There are certain limitations to consider in this cross-sectional study. First, the duration of ESBL-PE carriage was not investigated and there was no apparent relationship between human ESBL-PE carriage and contact with ESBL-PE colonized pigs (Table 6). Secondly, in contrast, a clear association was established between contact with other (food) animals, mainly poultry and human ESBL-PE colonization, with high statistical significance (Table 6), suggesting that further work should be undertaken in high risk populations and other food animals such as poultry in order to expand our understanding on the public health impact of the likely zoonotic transmission of ESBL-PE through the farm-to-plate continuum. Thirdly, the small human sample size precluded any direct conclusions on the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among abattoir workers. Finally, the molecular analyses were only carried out on a representative sub-sample and not all isolates due to financial constraints. Comprehensive molecular analysis would have certainly allowed better understanding of the genetic exchanges and evolution that are likely to occur within and between bacteria in this continuum.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of ESBL-PE in animals and humans in both Cameroon and South Africa taking food safety perspective. The high prevalence of ESBL-PE found in pigs in both countries as well as in humans in Cameroon highlights the food safety issue associated with their presence in the farm-to-plate continuum. It demonstrates the urgent need to implement multi-sectorial, multi-faceted and sustainable collaboration and activities among all stakeholders involved in this continuum in order to reduce the prevalence and contain the dissemination of ESBL-PE and ABR in these countries.

4. Methods

4.1. Study Design and Study Sites

From March to October 2016, a multicentre study was conducted in five abattoirs in Cameroon (n = 3) and South Africa (n = 2). All abattoirs were coded for ethical reasons as SH001, SH002, SH003, SH004 and SH005. They were visited thrice at different time points to allow a representative sample.

4.2. Ethical Considerations

Prior to the implementation of the study, ethical approvals were obtained from the National Ethics Committee for Research in Human Health of Cameroon (Ref. 2016/01/684/CE/CNERSH/SP), Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (Ref. BE365/15) and Animal Research Ethics Committee (Ref. AREC/091/015D) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In addition, ministerial approvals from the Cameroonian Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation (Ref. 015/MINRESI/B00/C00/C10/C14) and Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries (Ref. 061/L/MINEPIA/SG/DREPIA/CE) were also granted. This study was further placed on record with the South African National Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries [Reference: 12/11/1/5 (878)].

4.3. Sampling Procedures and Survey

4.3.1. Animal Sampling Procedure

Apparently healthy and freshly slaughtered/stunned pigs were randomly sampled in both Cameroon and South Africa. The interior cavity of both anterior nares were swabbed and rectal swabs of pigs were obtained using sterile Amies swabs (Copan Italia Spa, Brescia, Italia). Altogether, 432 nasal and rectal pigs were collected in both countries, with the number of samples from each slaughterhouse (SH001, n = 129; SH002, n = 57; SH003, n = 30; SH004, n = 120; SH005, n = 96) proportional to the annual pig production per site.

4.3.2. Human Sampling Procedure

Total sampling was employed where all exposed workers (≥21 years old) willing to participate were recruited in the study upon oral and written informed consent. Participants were requested to answer a questionnaire describing socio-demographic and medical/clinical history, as well as probable risk factors associated with ESBL-PE emergence/colonization and spread. Amies swab was used to collect both anterior nares and hand (between fingers for each right and left hand) samples which were processed within 4 h of collection.

4.4. Bacteriological Analysis

For the bacteriological analysis, three individual pig samples were pooled per abattoir, gender, specimen and area of breeding leading to 288 pools (144 nasal and 144 rectal) representing 432 original specimens collected from 432 pigs. Pooled pig samples and human swabs were cultured onto an in-house selective MacConkey agar supplemented with 2 mg/L cefotaxime (MCA+CTX) and incubated for 18–24 h at 37 °C for ESBL-PE screening. Presumptive ESBL-PE were phenotypically confirmed with Vitek® 2 System (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

4.5. ESBL Detection, Species Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Each colony with a unique morphotype growing on MCA+CTX was screened for ESBL production through the standard double disk synergy test (DDST) as recommended by the Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI) [16].

A panel of 19 antibiotics including amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, ampicillin, cefuroxime, cefuroxime axetil, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, ertapenem, meropenem, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, tigecycline, piperacillin/tazobactam, nitrofurantoin, colistin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, were tested using Vitek® 2 System and Vitek® 2 Gram Negative Susceptibility card (AST-N255) (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The CLSI was used for interpretation of the results excepted for colistin, piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid and amikacin that were interpreted using EUCAST breakpoints [17]. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as the control.

4.6. Genotypic Relatedness Determination of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli

The Thermo Scientific® GeneJet Genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Johannesburg, South Africa) was used for the genomic DNA extraction following the manufacturer’s instructions. ERIC-PCR was carried out using the primers ERIC 1 5′-ATG TAA GCT CCT GGG GAT TCA C-3′ and ERIC 2 5′-AAG TAA GTG ACT GGG GTG AGC G-3′ [18]. Reactions were performed in a 10 µL final solution containing 5 µL DreamTaq Green Polymerase Master Mix 2× (Thermo Fisher Scientific, South Africa), 2.8 µL nuclease free water, 0.1 µL of each primer (100 μM) and 2 µL DNA template and run in an Applied Biosystems 2720 programmable thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Johannesburg, South Africa). The ERIC-PCR protocol implemented included 3 min of initial denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 30 cycles consisting of a denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C for 1 min, extension at 65 °C for 8 min, a final extension at 65 °C for 16 min and final storage at 4 °C. ERIC profiles were digitized and analysed using Bionumerics (version 7.6, Applied Maths, Austin, TX, USA). The similarity between each strain was assessed using Dice coefficient and dendrograms were constructed using the Unweighted Pair-Group Method Algorithm (UPGMA).

4.7. Data Analysis

Data was encoded and entered into Epi Info (version 7.2, CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA) and Excel (Microsoft Office 2016) and analysed using STATA (version 14.0, STATACorp LLC, College Statioon, TX, USA). A data set was designed for specific human results and, combined animal and abattoir data. Abattoirs were classified as ESBL-positive if an ESBL-PE was identified from at least one pool (nasal or rectal samples). Likewise, each human was categorized as carrier or non-carrier, with carrier being defined as having ESBL-PE in at least one site (nares or hand).

The ESBL-PE prevalence was compared between categories with the chi square test (p < 0.05). The relationship between ESBL-PE carriage in pigs and humans was ascertained using logistic regression analyses adjusted for clustering at abattoir level. Likewise, risk factors for ESBL-PE carriage were determined univariately and selected for multivariate analysis when the p-value was <0.2. The McFadden’s pseudo R2 statistic (maximum likelihood method) was used to check the model fit and the final model included all determinants for which the pseudo R2 was the most elevated with p < 0.05 for each dependent variable.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Cameroonian Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Animal Industries as well as to the Cameroonian Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation of Cameroon for the study approval and strong support during the field implementation in the country. Metabiota Cameroon Limited, the Military Health Research Centre (CRESAR) and the Laboratory for Public Health Biotechnology/The Biotechnology Center of the University of Yaoundé I through Professor Wilfred Mbacham, are also acknowledged for their administrative, logistical and cold chain support during the sampling and baseline analysis stages. The National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS), especially Mlisana Koleka, Sarojini Govender and Thobile Khanyile are acknowledged for the assistance with the phenotypic identification and MIC determination. Keith Perret, KwaZulu-Natal Veterinary Services is truly appreciated for facilitating the administrative procedure pertaining to the sample collection in South Africa. The Drug Delivery Research Unit of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, through Thirumala Govender and Chunderika Mocktar is thanked for the cold chain support. The authors show their gratitude to Serge Assiene, Arthur Tchapet and Zamabhele Kubone, for their assistance with the sample collection and preliminary screening of samples in Cameroon and South Africa, respectively. We are very thankful to the abattoir owners/coordinators in South Africa, abattoirs’ leaders, supervisors, food safety inspectors, veterinarians, workers and study participants, for their support and assistance during the sample collection in both Cameroon and South Africa.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/8/1/10/s1. Table S1: Overall prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing bacteria isolated from humans per country and specimen type. Table S2: Overall prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing bacteria isolated from animals per country and specimen type. Table S3: Prevalence and distribution of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing-E. coli clusters per abattoir.

Author Contributions

L.L.F. co-developed the study, performed sample collection, microbiological, genomic and statistical analyses, prepared tables and figures and drafted the manuscript. R.C.F. undertook sample collection, laboratory analyses, contributed to data analysis, vetted the results and reviewed the manuscript. N.N. participated in the genomic extraction and fingerprinting analysis. U.G. and L.A.B contributed materials and reagents for sample collection and primary laboratory analyses and took part in the design of the study. H.Y.C. contributed materials and reagents for and vetting of genomic fingerprinting results. C.F.D. contributed equipment, materials and reagents for the sample collection and primary laboratory analyses, coordinated the field implementation in Cameroon, took part in the design of the study and reviewed the manuscript. S.Y.E. co-developed the study, vetted the results and undertook critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

L.L. Founou and R.C. Founou are funded by the Antimicrobial Research Unit (ARU) and College of Health Sciences (CHS) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. The National Research Foundation funded this study through the DST/NRF South African Research Chair in Antibiotic Resistance and One Health (Grant No. 98342), the NRF Competitive Grant for Rated Researchers (Grant No.: 106063) and the NRF Incentive Funding for Rated Researchers (Grant No. 85595), awarded to S.Y. Essack. Any opinions, results and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this review are those of the authors and therefore do not represent the official position of the funders. The funders had no role in the study design, preparation of the manuscript nor the decision to submit the work for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Professor Sabiha Essack is chairperson of the Global Respiratory Infection Partnership, sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from Reckitt and Benckiser (Pty.) Ltd. UK.

References

- 1.Aidara-Kane A., Andremont A., Collignon P. Antimicrobial resistance in the food chain and the AGISAR initiative. J. Infect. Public Health. 2013;6:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reist M., Geser N., Hächler H., Schärrer S., Stephan R. ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Occurrence, risk factors for fecal carriage and strain traits in the swiss slaughter cattle population younger than 2 years sampled at abattoir level. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Priority List of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discoveries and Development of New Antibiotics. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Founou L.L., Founou R.C., Essack S.Y. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1881. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewers C., Bethe A., Semmler T., Guenther S., Wieler L.H. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: A global perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:646–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magoué C.L., Melin P., Gangoué-Piéboji J., Okomo Assoumou M.C., Boreux R., De Mol P. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ngaoundere, Cameroon. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013;19:416–420. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohmen W., Bonten M.J., Bos M.E., van Marm S., Scharringa J., Wagenaar J.A., Heederik D.J. Carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in pig farmers is associated with occurence in pigs. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer J., Hille K., Mellmann A., Schaumburg F., Kreienbrock L., Köck R. Low-level antimicrobial resistance of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the nares of pig-exposed persons. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016;144:686–690. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815001776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohmen W., Schmitt H., Bonten M., Heederik D. Air exposure as a possible route for ESBL in pig farmers. Environ. Res. 2017;155:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations (FAO) Étude sur les Abattoirs D’animaux de Boucherie en Afrique Centrale (Cameroun–Congo–Gabon–Tchad) FAO; Rome, Italy: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le H.V., Kawahara R., Khong D.T., Tran H.T., Nguyen T.N., Pham K.N., Jinnai M., Kumeda Y., Nakayama T., Ueda S., et al. Widespread dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing, multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in livestock and fishery products in vietnam. Int. J. Food Contam. 2015;2:17. doi: 10.1186/s40550-015-0023-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahms C., Hübner N.O., Kossow A., Mellmann A., Dittmann K., Kramer A. Occurrence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in livestock and farm workers in mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geser N., Stephan R., Hachler H. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae in food producing animals, minced meat and raw milk. BMC Vet. Res. 2012;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, South Africa (DAFF) Fertilizer, Farm Feeds, Agricultural Remedies and Stock Remedies Act, 1947. Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, South Africa (DAFF); Pretoria, South Africa: 1996. [(accessed on 21 August 2017)]. Available online: http://www.daff.gov.za/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Ami R., Rodríguez-Baño J., Arslan H., Pitout J.D., Quentin C., Calbo E.S., Azap Ö.K., Arpin C., Pascual A., Livermore D.M., et al. A multinational survey of risk factors for infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in non-hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:682–690. doi: 10.1086/604713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Informational Supplement. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2016. [(accessed on 13 March 2017)]. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI document M100-S26. Available online: https://clsi.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and zone Diameters Version 6.1. [(accessed on 25 March 2017)];2016 Available online: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_6.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- 18.Versalovic J., Koeuth T., Lupski J.R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.